Abstract

Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 can use a wide variety of terminal electron acceptors for anaerobic respiration, including certain insoluble manganese and iron oxides. To examine whether the outer membrane (OM) cytochromes of MR-1 play a role in Mn(IV) and Fe(III) reduction, mutants lacking the OM cytochrome OmcA or OmcB were isolated by gene replacement. Southern blotting and PCR confirmed replacement of the omcA and omcB genes, respectively, and reverse transcription-PCR analysis demonstrated loss of the respective mRNAs, whereas mRNAs for upstream and downstream genes were retained. The omcA mutant (OMCA1) resembled MR-1 in its growth on trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), dimethyl sulfoxide, nitrate, fumarate, thiosulfate, and tetrathionate and its reduction of nitrate, nitrite, ferric citrate, FeOOH, and anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonic acid. Similarly, the omcB mutant (OMCB1) grew on fumarate, nitrate, TMAO, and thiosulfate and reduced ferric citrate and FeOOH. However, OMCA1 and OMCB1 were 45 and 75% slower than MR-1, respectively, at reducing MnO2. OMCA1 lacked only OmcA. While OMCB1 lacked OmcB, other OM cytochromes were also missing or markedly depressed. The total cytochrome content of the OM of OMCB1 was less than 15% of that of MR-1. Western blots demonstrated that OMCB1 still synthesized OmcA, but most of it was localized in the cytoplasmic membrane and soluble fractions rather than in the OM. OMCB1 had therefore lost the ability to properly localize multiple OM cytochromes to the OM. Together, the results suggest that the OM cytochromes of MR-1 participate in the reduction of Mn(IV) but are not required for the reduction of Fe(III) or other electron acceptors.

Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 is a gram-negative facultative anaerobe with remarkable respiratory versatility; this versatility is the result of its complex multicomponent branched electron transport system that includes cytochromes, quinones, dehydrogenases, and iron-sulfur proteins (18–20, 22–26, 29, 30). MR-1 can couple its anaerobic growth, and link respiratory proton translocation, to the reduction of a variety of compounds, including insoluble manganese(IV) and iron(III) oxides (18, 19, 23, 25, 26, 29).

Previous studies which describe mutants of MR-1 that are deficient in particular electron transport components have demonstrated that menaquinone (25) and a 21-kDa tetraheme c-type cytochrome (CymA) localized to the cytoplasmic membrane (CM) (18, 31) are both required for the reduction of Mn(IV) and Fe(III). However, because both of these components are also required for the use of nitrate and fumarate as electron acceptors, they likely serve as common intermediates in electron transport chains which subsequently branch to different terminal reductases. For example, the fumarate reductase in Shewanella is a periplasmic flavocytochrome (15), and a mutant of MR-1 deficient in this cytochrome is only deficient in fumarate reduction (22). The putative role of CymA orthologs in other bacteria is to accept electrons from membrane-bound quinones and transfer them to downstream electron transport components (3). Furthermore, the localization of CymA to the CM precludes its ability to make direct contact with extracellular insoluble metal oxides. Therefore, as-yet-unidentified electron transport components downstream from menaquinone and CymA likely serve as the terminal reductases ultimately responsible for Mn(IV) and Fe(III) reduction.

When grown under anaerobic conditions, MR-1 cells localize a majority of their membrane-bound cytochromes to the outer membrane (OM) (23). At least four heme-positive bands are seen in heme-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels of its OM, and all OM cytochromes contain c-type hemes (24). OmcA was the first of these OM cytochromes to be purified, and the partial protein sequence of this 83-kDa protein was used to facilitate cloning and sequencing of the omcA gene (24, 30). The omcA sequence predicts that OmcA contains 10 heme c consensus-binding domains (CXXCH [where X is any residue]) and has a lipoprotein modification at the amino terminus of the mature protein (30). The size of the omcA transcript is consistent with monocistronic expression, and omcA homologs are expressed in other strains of S. putrefaciens (30) and Shewanella frigidimarina (8). OmcA and the other OM cytochromes in MR-1 are localized where they could potentially make direct contact with extracellular metal oxides at the cell surface, and spectral studies indicate that these OM cytochromes can transfer electrons to Fe(III) and Mn(III) oxides in vitro (24). Furthermore, conventional inhibitors of electron transport inhibit Mn(IV) and Fe(III) reduction by MR-1 (19, 20, 26), implying a role for cytochromes in respiratory metal reduction. The OM cytochromes could therefore represent a way to link their electron transport systems to the reduction of extracellular insoluble Mn(IV) or Fe(III) oxides.

A successful site-directed gene replacement strategy for MR-1 has only recently become available (31). This approach was used to isolate knockout strains of MR-1 which are deficient in either of two of the OM cytochrome genes, omcA or omcB. Both mutations significantly decrease the cells' ability to reduce Mn(IV). In contrast, the ability to reduce Fe(III) is not affected in these mutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Anthraquinone-2, 6-disulfonic acid, disodium salt (AQDS), was purchased from Aldrich Chemical (Milwaukee, Wis.). All other materials were from sources previously described (18, 31).

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

A list of the bacteria and plasmids used in this study is presented in Table 1. For molecular biology purposes, S. putrefaciens and Escherichia coli were grown aerobically on Luria-Bertani medium (36) supplemented, when required, with antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin (Ap) 50 μg ml−1; kanamycin (Km), 50 μg ml−1; and chloramphenicol (Cm) 34 μg ml−1. E. coli was grown at 37°C unless otherwise indicated. E. coli was routinely grown at 37°C, whereas S. putrefaciens was grown at either 30°C or room temperature (23 to 25°C).

TABLE 1.

Bacteria and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Description | Reference | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. putrefaciens | |||

| MR-1 | Manganese-reducing strain from Lake Oneida, N.Y. sediments | 26 | Previous study |

| OMCA1 | omcA mutant derived from MR-1; omcA::Kmr | This work | |

| OMCB1 | omcB mutant derived from MR-1; omcB::Kmr | This work | |

| OMCB2 | Second omcB mutant derived from MR-1, independent from OMCB1; omcB::Kmr | This work | |

| E. coli | |||

| S17-1(λpir) | λ(pir) hsdR pro thi; chromosomal integrated RP4-2 Tc::Mu Km::Tn7; donor strain to mate pEP185.2-derived plasmids into MR-1 | 37 | V. L. Miller |

| TOP10 | F−mcrAΔ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu) 7697 galU galK rpsL (Smr) endA1 nupG; used as host for plasmids derived from pCR2.1-TOPO | Invitrogen | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pVK100 | 23-kb broad-host-range cosmid; Tcr Kmr Tra+ | 11 | ATCC 37156 |

| pCR2.1-TOPO | 3.9-kb vector for cloning PCR products; Apr | Invitrogen | |

| pUT/mini-Tn5Km | Apr; Tn5-based delivery plasmid; used as source of Kmr gene | 7 | D. Frank |

| pTOPO/omcA | pCR2.1-TOPO with most of omcA plus associated 5′ DNA from MR-1; 6.2 kb | This work | |

| pTOPO/omcA:Km | pTOPO/omcA with the Kmr gene replacing 319 bp of omcA; 8.0 kb | This work | |

| pTOPO/omcB | pCR2.1-TOPO with omcB plus associated 5′ and 3′ DNA from MR-1; 6.3 kb | This work | |

| pTOPO/omcB:Km | pTOPO/omcB with the Kmr gene replacing 371 bp of omcB; 8.0 kb | This work | |

| pEP185.2 | 4.28-kb mobilizable suicide vector derived from pEP184; oriR6K mobRP4 Cmr | 10 | V. L. Miller |

| pJQ200KS | Mobilizable vector; P15A origin; Gmr; used as source of sacB gene | 34 | G. Reid |

| pTOPO/sacB | pCR2.1-TOPO containing the sacB gene from pJQ200KS; Apr | This work | |

| pEPsacB | Mobilizable suicide vector derived from pEP185.2; Cmr; sacB gene from pTOPO/sacB cloned into the NsiI site of pEP1852 | This work | |

| pDSEPsac83 | Kmr gene-interrupted omcA gene from pTOPO/omcA:Km cloned into the EcoRV site of pEP185.2, and the sacB gene from pTOPO/sacB cloned into the NsiI site of pEP185.2; Cmr Kmr; 8.3 kb; used for gene replacement to generate OMCA mutant | This work | |

| pDSEPsac53 | Kmr gene-interrupted omcB gene from pTOPO/omcB:Km cloned into the XhoI site of pEPsacB; Cmr Kmr; 8.3 kb; used for gene replacement to generate OMCB1 and OMCB2 mutants | This work |

For the preparation of subcellular fractions, S. putrefaciens was grown under anaerobic conditions as previously described (23) in defined medium (29) supplemented with 15 mM lactate, 24 mM fumarate, and vitamin-free Casamino Acids (0.2 g liter−1). For testing the growth on or reduction of electron acceptors under anaerobic conditions, the defined medium was supplemented with vitamin-free Casamino Acids (0.2 g liter−1), 15 mM lactate plus 15 mM formate, and one of the following electron acceptors as indicated: 20 mM trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), 20 mM disodium fumarate, 2 mM sodium nitrate, 5 mM dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 10 mM sodium thiosulfate, 2 mM sodium tetrathionate, 10 mM ferric citrate, 2mM amorphous FeOOH, 0.2 mM AQDS, or 5 mM δMnO2. For growth on TMAO, the medium was also supplemented with 30 mM HEPES to buffer against alkalinization by the product trimethylamine. Appropriate antibiotics were included at the concentrations listed above. To allow for the growth of all strains under equivalent conditions (i.e., in the presence of kanamycin), the broad-host-range cosmid pVK100 was introduced into the strains; their electron acceptor phenotypes were not altered by the presence versus the absence of pVK100. For testing electron acceptor use, inocula were prepared using cells grown aerobically for ≤48 h on Leuria-Bertani medium supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics; the cells were suspended in sterile distilled water, and the inoculum densities were adjusted to equalize turbidity (optical density at 500 nm).

DNA manipulations.

A list of the synthetic oligonucleotides used is presented in Table 2. Restriction digests and mapping, cloning, subcloning, and DNA electrophoresis were done according to standard techniques (36) following manufacturers' recommendations as appropriate. DNA ligations were done using Fast-Link DNA ligase (Epicentre Technologies, Madison, Wis.) or T4 DNA ligase (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.). Isolation of plasmid and cosmid DNAs was accomplished using the QIAprep spin plasmid kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.). The sizes of DNA fragments, RNA, and proteins were estimated based on their electrophoretic mobilities relative to known standards using a computer program kindly provided by G. Raghava (35). Colony PCR (38) using primers specific to omcA or omcB was utilized to screen transconjugants for gene replacement events.

TABLE 2.

Synthetic oligonucleotides designed from MR-1 genome data

| Name | Oligonucleotide sequencea |

|---|---|

| Oligonucleotides for omcA experiments | |

| A1 | 5′-TGCTCGAGTTACCCGCTTAAAGTGACTGA-3′ |

| A2 | 5′-TGCTCGAGAAGATACCGCCGTTAGTTTC-3′ |

| A3 | 5′-TTGGCGCGCCGATCCAGAATCAGGCAATAGC-3′ |

| A4 | 5′-TTGGCGCGCCAGTGTCGCATTTATTGGCAGA-3′ |

| A5 | 5′ TTGATATCGGTGGCAGTGATGGRAAAGAT-3′ |

| A6 | 5′ TCAGTCGACTTAGTTACCGTGTGCTTCCAT-3′ |

| Oligonucleotides for omcB experiments | |

| B1 | 5′-TGCTCGAGCATGTTGGGTTAGCCTTTCCTTG-3′ |

| B2 | 5′-TGCTCGAGTTCGACTTGCTCTGGCGTCATTT-3′ |

| B3 | 5′ TTGGCGCGCCCGGGTAAAGGCCACTCTCAACAA-3′ |

| B4 | 5′ TTGGCGCGCCGGCCGTCGAAATCTTCAACCATT-3′ |

| B5 | 5′-GCAGTGGTAATAACGGCAATGAT-3′ |

| B6 | 5′-TCAACAACTGCACCGAAAGACTC-3′ |

| Oligonucleotides for mtrA-mtrB experiments | |

| M1 | 5′-TACTGCCGGCACTTACCATCACA-3′ |

| M2 | 5′-GTGCGGTGTAGTCATGGCTGTTA-3′ |

Underlined regions indicate the following retriction endonuclease sites engineered into the oligonucleotides: XhoI sites in A1, A2, B1, and B2; AscI sites in A3, A4, B3, and B4; an EcoRV site in A5; and an SalI site in A6.

Aerobically grown mid-logarithmic-phase E. coli cells were prepared for electroporation as suggested by Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, Calif.); the cells were stored in 10% glycerol at −80°C until they were needed. Plasmids and cosmids were introduced into E. coli by electroporation as previously described (18).

Thermal-cycle DNA sequencing was done as previously described (18), except that the SequiTherm EXCEL II DNA sequencing system (Epicentre Technologies) was used. Computer-assisted sequence analysis and comparisons were done using MacVector software (IBI, New Haven, Conn.).

Construction of omcA and omcB insertion mutations.

The use of the mobilizable vector pEP185.2 as a suicide vector for the replacement of cymA in MR-1 was previously reported (31). An analogous strategy was used to construct gene replacement mutants of omcA and omcB.

To construct a plasmid suitable for replacement of omcA, a 2,273-bp DNA fragment containing nearly all of the omcA gene plus some 5′ upstream DNA was generated by PCR of MR-1 genomic DNA using primers A1 and A2 (Table 2). This PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, generating pTOPO/omcA. Inverse PCR (33) was done using pTOPO/omcA as the template and primers A3 and A4 (Table 2), which hybridize within omcA and have AscI restriction sites added at their 5′ ends; this generated TOPO/omcA(Δ319), a linear 5.9-kb fragment that contains all of pCR2.1-TOPO and the 5′ and 3′ ends of omcA but is missing 319 bp of internal omcA sequence. The 2.1-kb Kmr gene from pUT/mini-Tn5Km was generated by PCR with primers that included AscI restriction sites at the 5′ ends. Following digestion with AscI, the Kmr gene was ligated to the TOPO/omcA(Δ319) fragment, generating pTOPO/omcA:Km. A 4.1-kb DNA fragment containing the Kmr-interrupted omcA gene was generated by PCR using primers A1 and A2 (Table 1) and pTOPO/omcA:Km as the template; the resulting fragment was blunt ended and ligated into the EcoRV site of the suicide vector pEP185.2, generating pEP83; finally, the sacB gene was excised from pTOPO/sacB using NsiI and ligated into the NsiI site of pEP83, generating pDSEPsac83, which was electroporated into the donor strain E. coli S17-1(λpir). At each step during the construction process, appropriate analyses (restriction mapping, PCR, and DNA sequence analysis) were done to ensure that the expected construct was obtained.

To construct a plasmid suitable for replacement of omcB, an analogous strategy was used, substituting appropriate primers. Primers B1 and B2 (Table 2) were used to amplify omcB plus flanking DNA from MR-1 genomic DNA; ligation into pCR2.1-TOPO generated pTOPO/omcB. Inverse PCR (33) was done using pTOPO/omcB and primers B3 and B4 (Table 2), generating TOPO/omcB(Δ371), a linear 5.9-kb fragment that is missing 371 bp of internal omcB sequence. The 2.1-kb Kmr gene with AscI restriction sites at the ends was ligated to TOPO/omcB(Δ371), generating pTOPO/omcB:Km; from this, the Kmr-interrupted omcB gene was excised and ligated into the XhoI site of pEPsacB, generating pDSEPsac53, which was electroporated into the donor strain E. coli S17-1(λpir).

The expression of the sacB gene, which encodes levansucrase and is inducible by sucrose, is lethal in many gram-negative bacteria (34). In the gene replacement strategies described above, the sacB gene was amplified by PCR from pJQ200KS using primers that flanked sacB and that included NsiI restriction sites at their 5′ ends. The resulting sacB PCR product was cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, generating pTOPO/sacB, which served as the source of sacB for insertion into the suicide vectors.

For gene replacement, E. coli S17-1(λpir)/pDSEPsac83 or S17-1(λ pir)/ pDSEPsac53 was mated with MR-1, and MR-1 exconjugants were selected using kanamycin under aerobic conditions on defined medium with 15 mM lactate as the electron donor (31).

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was purified from anaerobically grown cells using a hot-phenol method followed by treatment with RNase-free DNase as previously described (18). All standard precautions to prevent RNase contamination were followed (36). Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was done using the Titan One Tube RT-PCR system (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (2 μg) from each strain served as the template, and sense and antisense primers (Table 2) were based on the sequences of omcA, omcB, and mtrA-mtrB from MR-1.

Purification of OmcB.

The 53-kDa OM cytochrome was purified from the OM of MR-1 cells grown under anaerobic conditions with fumarate as the electron acceptor. Loosely associated noncytochrome OM proteins were removed with cholate as previously described (24). The OM cytochromes were subsequently solubilized in buffer A (20 mM K2HPO4 [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% azide, 5% glycerol) containing 0.19 mM NaCl, 9.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 49.6 mM Z3-12 (final concentrations which accounted for the volume of OM); the Z3-12/protein ratio was 16.5/1 (wt/wt), with a final protein concentration of 1 mg ml−1. After being stirred for 10 min at 23°C, the solubilized OM was sonicated twice (30 each time) with interspersed 1-min periods of cooling at 23°C and then centrifuged for 101 min at 52,000 rpm (303,800 × g) at 4°C in a Beckman 55.2Ti rotor. The supernatant fractions which contained the cytochromes were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration. The concentrate was applied to a Sephadex G150 gel filtration column at 4°C and eluted with buffer A containing 0.5 M NaCl, 0.1 mM DTT, and 14.9 mM Z3-12. The fractions were screened on heme- and silver-stained SDS-PAGE gels. The fractions containing the 53-kDa OM cytochrome were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration and then dialyzed against buffer E (5 mM K2HPO4 [pH 7.4], 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% azide, 5% glycerol, 14.9 mM Z3-12, 0.1 mM DTT). The sample was then applied to a DEAE-Sephacel ion-exchange column at 4°C, and buffer E was pumped through the column to remove nonadherent proteins. The column was then developed using a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 0.5 M) in buffer E. The fractions containing the 53-kDa OM cytochrome were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration. At this point, the cytochrome was sufficiently purified for N-terminal sequencing. The N-terminal sequence was determined by L. Mende-Mueller of the Protein/Nucleic Acid Shared Facility of the Medical College of Wisconsin, using an Applied Biosystems model 477A pulsed liquid phase protein sequencer. Throughout the purification procedure, the goal in selecting fractions at the various steps was to optimize purity at the expense of recovery.

Miscellaneous procedures.

Growth was assessed by measuring culture turbidity at 500 nm in a Beckman DU-64 spectrophotometer. Nitrate (6) and nitrite (39) were determined colorimetrically in cell-free filtrates. Fe(II) was determined by a ferrozine extraction procedure (14, 28). Mn(II) was determined in filtrates by a formaldoxime method (1, 5), and δMnO2 (vernadite) was prepared as described previously (26). Amorphous ferric oxyhydroxide (FeOOH) was prepared as described previously (14) and was sterilized by steam autoclaving before use. An aqueous stock solution of AQDS (0.2 M) was adjusted to pH 7.4 and sterilized by steam autoclaving before use. The reduction of AQDS to 2,6-anthrahydroquinone disulfonate (AHDS) was measured as increase in absorbance (13) at 395 nm. Spectral analysis (340 to 700 nm) showed that 395 nm represented a point near maximal absorbance for AHDS and a region where absorbance did not differ significantly with minor changes in wavelength.

CM, intermediate membrane (IM), OM, and soluble fractions (periplasm plus cytoplasm) were purified from cells by an EDTA-lysozyme-Brij protocol as previously described (23). IM fractions have also been observed during subcellular fractionation of other gram-negative bacteria; except for a buoyant density intermediate between those of the CM and the OM, the IM closely resembles the OM (24). The separation and purity of these subcellular fractions were assessed by spectral cytochrome content (23), membrane buoyant density (23), and SDS-PAGE gels (12, 17) stained for protein with Pro-Blue (Owl Separation Systems, Woburn, Mass.) or for heme as previously described (23). Protein was determined by a modified Lowry method, with bovine serum albumin as the standard (18). Western blotting using an antibody specific for OmcA was done as previously described (24).

RESULTS

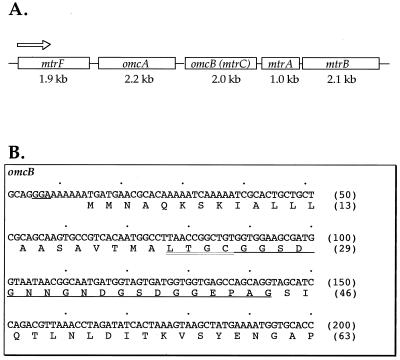

The linear arrangement of the genes surrounding omcA and omcB in the MR-1 genome is shown in Fig. 1A. omcA (30) and omcB encode decaheme c-type cytochromes, which are putative OM lipoproteins.

FIG. 1.

(A) Linear orientation of the gene cluster of MR-1 surrounding omcA and omcB as derived from GenBank accession no. AF083240 (2). The diagram is not drawn to scale. The transcription direction in all cases is from left to right (5′ → 3′). (B) N-terminal sequencing of purified OmcB yielded the underlined amino acid sequence, which corresponded exactly to the predicted coding region of omcB (only 200 bp of DNA sequence are shown, beginning just upstream of the omcB start codon). The cysteine at residue 25 is likely the first residue of mature OmcB but was unidentified during N-terminal sequencing, consistent with the putative lipoprotein modification of this residue. The lipoprotein consensus sequence (LTGC) is indicated by the double underline. The numbers at right indicate arbitrary positions within the nucleotide sequence (top) and absolute numbers of amino acid residues (bottom), with 1 corresponding to the N terminus of the immature protein.

Amino-terminal sequence of the 53-kDa OM cytochrome.

Previously, four heme-positive bands were seen in the OM of MR-1 (24). In large-scale SDS-PAGE gels, the smallest of these migrated with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 53 kDa (24). This 53-kDa cytochrome was purified from the OM, and the amino acid sequence of its N terminus was determined (XGGSDGNNGNDGSDGGEPAG [X, unidentified residue]). This sequence aligned exactly with the predicted amino acid sequence of omcB (Fig. 1B) encoded by the corresponding region from the MR-1 genome (preliminary genomic sequence data was obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research [TIGR] through the website at http://www.tigr.org). This amino acid sequence did not align with any other predicted open reading frames (ORFs) within the MR-1 genome. The nucleotide sequence for omcB was first described in GenBank accession no. AF083240 (2); in this GenBank submission, omcB was designated as mtrC ORF (Fig. 1A) because it was one of several uncharacterized ORFs in the vicinity of mtrB, which encodes a noncytochrome protein somehow involved in metal reduction (2); the nonspecific designation mtr (metal reduction) was assigned to mtrC and the other ORFs in this region even though their identities and functions were not known. In this study, it is clearly established that mtrC encodes an OM cytochrome (omc); since it is adjacent to the previously characterized gene omcA, which encodes the 83-kDa OM cytochrome (30), mtrC is hereafter referred to as omcB, a designation more appropriate to its identity.

The alignment of the N-terminal sequence begins at the glycine representing residue 26 of OmcB (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the hydrophobic leader sequence is removed during protein translocation and maturation. A lipoprotein consensus sequence (LXXC) (9) was found immediately preceding glycine-26, suggesting that OmcB may be a lipoprotein; this could explain why the N-terminal residue of mature OmcB, which should be a cysteine (Fig. 1), was not identifiable. Lipoproteins, many of which are localized to the OM, contain glycerylcysteine with two ester-linked fatty acids plus one amide-linked fatty acid at their amino termini (9), which serve as hydrophobic anchors for membrane attachment.

Isolation and characterization of omcA and omcB knockout strains.

E. coli S17-1 (λpir)/pDSEPsac83 or S17-1(λpir)/ pDSEPsac53 was mated with MR-1, and MR-1 exconjugants were selected using kanamycin under aerobic conditions on defined medium with 15 mM lactate as the electron donor. Colonies were screened by colony PCR (38) using either primers A1 and A2 or B1 and B2 for omcA or omcB gene replacements, respectively. Those lacking the expected wild-type PCR products of 2.3 or 2.4 kb for omcA or omcB, respectively, in two independent PCR analyses were pursued as putative insertional mutants. A single omcA knockout strain (OMCA1), and two omcB knockout strains (OMCB1 and OMCB2), which were isolated from independent gene replacement experiments, were pursued for further characterization. These strains had the expected characteristics of gene replacement mutants: (i) they lacked the expected wild-type PCR products for the omcA and omcB genes, respectively, in independent PCR analyses; (ii) they were negative for the expected PCR product using primers specific to the cat gene of pEP185.2; (iii) they did not grow in the presence of chloramphenicol but did grow in the presence of kanamycin; and (iv) they were positive for the expected PCR product using primers specific to the Kmr gene used to interrupt the omcA and omcB genes. The lack of the cat gene and the sensitivity to chloramphenicol are consistent with a double-crossover gene replacement, as a single-crossover insertion into the genome should retain the cat gene of the suicide vector.

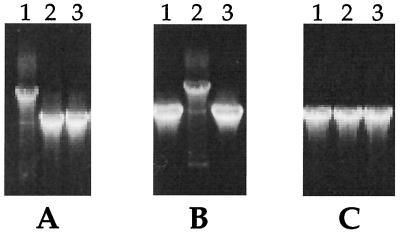

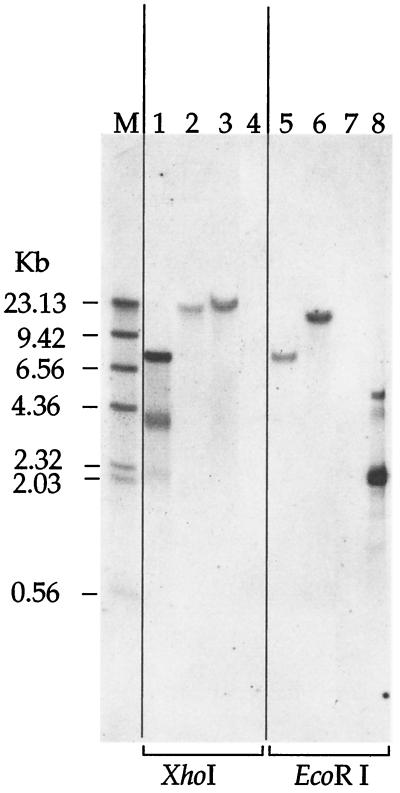

PCR analysis using genomic DNA as a template demonstrated that, in the OMCA1 and OMCB1 mutant strains, only the omcA and omcB genes, respectively, had been interrupted by gene replacement (Fig. 2). These mutants lacked the bands corresponding to the wild-type genes but had bands that were ∼1.8 kb larger, consistent with the size of the Kmr gene replacement. The mutants retain the wild-type mtrA-mtrB locus, which is immediately downstream of omcB (Fig. 2). Southern blots show the presence of single insertions of the Kmr gene in the genomic DNAs of OMCA1 and OMCB1, as well as its absence in MR-1 (Fig. 3). The sizes of the bands in XhoI-digested genomic DNA are consistent with the expected bands of approximately 19.0 kb. The sizes of the bands in EcoRI-digested genomic DNA are consistent with the expected bands of approximately 12.7 and 7.7 kb for OMCA1 and OMCB1, respectively.

FIG. 2.

PCR products with genomic DNA templates from the following strains: lanes 1, OMCB1; lanes 2, OMCA1; lanes 3, MR-1. The following primer pairs (Table 2) were used: B1 and B2 for omcB (A), A1 and A2 for omcA (B), and M1 and M2 for mtrA-mtrB (C).

FIG. 3.

Southern blot of genomic DNA from Shewanella strains or of pUT/Tn5Km plasmid DNA probed with the Kmr gene from pUT/Tn5Km. The lanes were loaded with DNA that was digested with either XhoI (lanes 1 to 4) or EcoRI (lanes 5 to 8). Lanes 1 and 8, pUT/Tn5Km; lanes 2 and 6, OMCA1; lanes 3 and 5, OMCB1; lanes 4 and 7, MR-1. The sizes of the DNA markers (lane M) are indicated on the left.

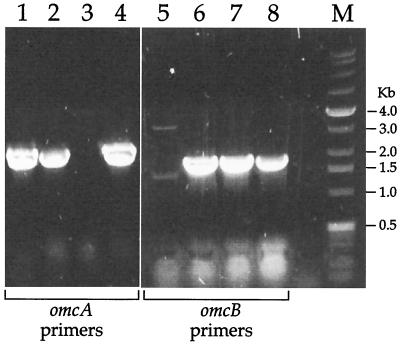

To examine expression of the relevant genes, RT-PCR analysis of total RNA from these strains was done, using primer sets specific to the omcA and omcB genes (Fig. 4). The omcA and omcB transcripts were readily detected in MR-1, but only the omcA transcript was missing in OMCA1 and only the omcB transcript was missing in OMCB1. It should be noted that OMCA1 retains the omcB transcript (Fig. 4); even though omcB lies just downstream of omcA, the interruption of omcA does not have a polar effect, i.e., it does not prevent expression of omcB.

FIG. 4.

RT-PCR products using total RNA from the following strains (grown anaerobically with fumarate) as templates: lanes 1 and 5, OMCB1; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, MR-1; lanes 3 and 7, OMCA1. Primers A5 and A6 (Table 2), specific for omcA, were used for the RT-PCRs in lanes 1 to 4, and primers B5 and B6, specific for omcB, were used for the reactions in lanes 5 to 8. The sizes of the DNA markers (lane M) are indicated on the right. Controls without reverse transcriptase yielded no bands (not shown), indicating that the products shown arise from mRNA.

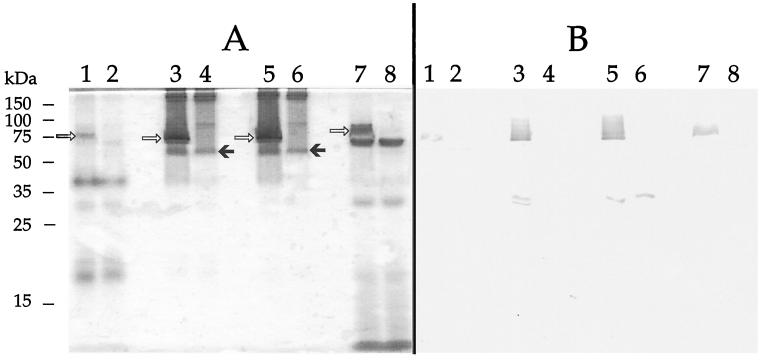

It was previously shown that omcA encodes a decaheme c-type cytochrome with a predicted molecular mass of 82.7 kDa which is most prominent in the OM and IM with lesser amounts in the soluble fraction (24, 30). The characterization by various means, including SDS-PAGE (not shown), of subcellular fractions prepared from anaerobically grown MR-1 and OMCA1 cells confirmed a prominent separation of the various fractions, which were comparable to analogous fractions from previous experiments (18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 30). SDS-PAGE analysis with heme staining showed that, compared to MR-1, mutant OMCA1 is missing the heme-positive band corresponding to OmcA in the membrane fractions (Fig. 5A). OMCA1 retains the heme-positive band corresponding to OmcB (Fig. 5A), consistent with the retention of the omcB transcript in this strain (Fig. 4). In the soluble fractions, a slightly larger but less intense heme-positive band was seen in MR-1 but was absent in OMCA1 (Fig. 5A). Using a previously described immunoglobulin G (IgG) specific for OmcA (24), Western blotting of the same fractions confirmed the presence of OmcA in MR-1 and its absence in OMCA1 (Fig. 5B). A Western blot of whole cells confirmed the absence of OmcA in OMCA1 (not shown). While OmcA was detected in all subcellular fractions of MR-1, it is most prominent in the IM and OM fractions (Fig. 5B); this is consistent with previous studies that had demonstrated that the vast majority of OmcA is localized in the OM and IM, with lesser amounts in the other fractions (24). Since OM proteins are translocated across the CM and periplasm en route to the OM, their presence in the CM and soluble fractions is not unexpected, especially given the sensitivity of Western blotting and heme staining. The broadening of the OmcA band in Western blots of the IM and OM (Fig. 5B) is typical when 5 μg of OM is loaded (30) and is due to the much higher content of OmcA; OmcA in MR-1 is readily detected by Western blotting with 0.5 μg of OM, a loading which results in a sharper, well-defined band (24). Higher loadings (5 μg) were used in the blot shown in Fig. 5B to provide conclusive proof of the absence of OmcA in the knockout OMCA1. In both the heme stain and Western blot, the leading edge of the band corresponding to OmcA in the soluble fraction is of slightly larger molecular mass than that seen in the membrane fractions (Fig. 5); OmcA in the soluble fraction likely represents partially processed forms in the periplasm or cytoplasm, which would be expected to be of slightly larger mass than mature OmcA in the OM (30).

FIG. 5.

SDS-PAGE of subcellular fractions prepared from MR-1 (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or OMCA1 (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) cells grown anaerobically with fumarate as the electron acceptor. (A) Gel stained for heme. (B) Western blot of a duplicate of the gel in panel A run under identical conditions and probed with an IgG specific for OmcA (24). The lanes were loaded with 10 (A) or 5 (B) μg of protein from each of the following subcellular fractions: CM (lanes 1 and 2), IM (lanes 3 and 4), OM (lanes 5 and 6), and soluble fraction (lanes 7 and 8). OMCA1 lacks the band corresponding to OmcA (open arrows), but it retains the OmcB protein (solid arrows). The Western blot demonstrates the presence of OmcA in MR-1 and its absence in OMCA1. The bars and numbers at the left indicate the migration and masses of the protein standards obtained from a parallel gel containing the same samples but stained for protein.

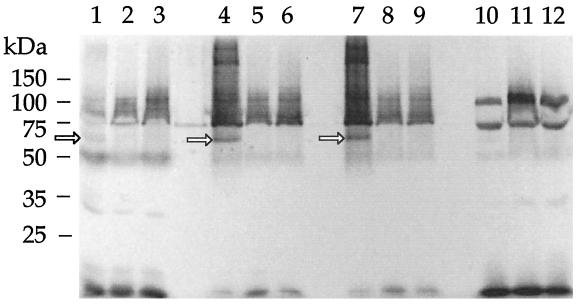

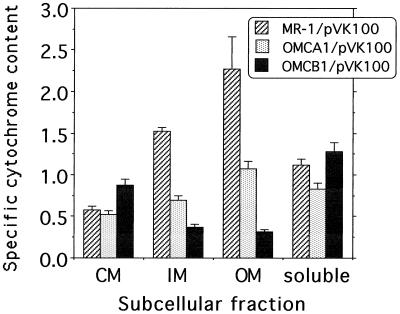

Subcellular fractions were also prepared from OMCB1 and compared to those of MR-1. SDS-PAGE analysis with heme staining showed that, compared to MR-1, mutants OMCB1 and OMCB2 were missing the heme-positive band corresponding to OmcB in the OM and IM fractions (Fig. 6). Unexpectedly, all other OM cytochromes were either missing or present at markedly reduced levels in strains OMCB1 and OMCB2 (Fig. 6). When examined quantitatively by reduced-minus-oxidized cytochrome spectra, the cytochrome content in the IM and OM of OMCB1 was markedly depressed (<15% that of MR-1), consistent with the loss of most OM cytochromes (Fig. 7). These cytochrome levels were much lower than those in OMCA1, which is only missing OmcA and for which the OM had approximately 50% of the specific cytochrome content of MR-1 (Fig. 7). The cytochrome levels in the CM and soluble fractions of OMCA1 and the soluble fraction of OMCB1 were generally similar to those of MR-1 (Fig. 7). There was a modest increase in cytochrome content in the CM of OMCB1 relative to that of MR-1 (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

Heme-stained SDS-PAGE profiles of subcellular fractions prepared from MR-1/pVK100 (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10), OMCB2 (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11), or OMCB1/pVK100 (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12) cells grown anaerobically with fumarate as the electron acceptor. The lanes were loaded with 25 μg of protein from each of the following subcellular fractions: CM (lanes 1 to 3), IM (lanes 4 to 6), OM (lanes 7 to 9), and soluble fraction (lanes 10 to 12). Strains OMCB1 and OMCB2 lack the band corresponding to OmcB (arrows) in the IM and OM. The bars and numbers at the left indicate the migration and masses of the protein standards obtained from a parallel gel containing the same samples but stained for protein.

FIG. 7.

Specific cytochrome content of subcellular fractions prepared from the indicated strains, which were grown anaerobically with fumarate as the electron acceptor. The specific cytochrome content is the difference between the absorbances at the peak and trough of the Soret region from reduced-minus-oxidized difference spectra per milligram of protein. The values represent means plus the high values for two parallel but independent experiments.

While the loss of OmcB was expected in the omcB knockout strains, the loss or marked depression of the other OM cytochromes was unexpected. The two other known OM cytochrome genes (omcA and mtrF) lie upstream of omcB and are not expressed as a multicistronic operon with omcB (30). Interruption of omcA does not affect the expression of omcB (Fig. 4 and 5), and the mRNA for omcA is still present in OMCB1 (Fig. 4). RT-PCR also clearly detected the mRNA for mtrF in OMCB1 (not shown). Together, these data suggested that the other OM cytochrome genes were being transcribed in OMCB1 and OMCB2, but it was unclear if the lack of the cytochromes in the OM was due to problems with translation or with protein localization. This issue was examined by Western blot analysis of subcellular fractions using the antibody specific for OmcA. Consistent with previous results (24), the vast majority of OmcA was present in the OM and IM of MR-1, with lesser amounts in the CM and soluble fractions (Fig. 8). As expected, OmcA was not detectable in any of the fractions of OMCA1 (Fig. 8). Strain OMCB1 clearly synthesized OmcA, but relative to MR-1, much less OmcA was detected in the OM and IM fractions whereas the CM and soluble fractions had increased levels of OmcA (Fig. 8). Therefore, the marked depletion of multiple OM cytochromes in OMCB1 (Fig. 6 and 7) is not likely to be due to decreased protein synthesis but rather to defects in localization of these cytochromes to the OM.

FIG. 8.

Western blot using polyclonal IgG specific for OmcA. The lanes were loaded with 5 μg of protein from each of the following subcellular fractions: CM (lanes 1 to 3), IM (lanes 4 to 6), OM (lanes 7 to 9), and soluble fraction (lanes 10 to 12). The subcellular fractions were prepared from fumarate-grown cells of the following strains: MR-1/pVK100 (lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10), OMCB1/pVK100 (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11), and OMCA1/pVK100 (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12).

Electron acceptor use by wild-type versus mutant strains.

Since cytochromes are key components of many electron transport chains involved in respiratory processes, we examined the electron acceptor phenotypes of the omcA and omcB knockout strains. OMCA1 was very similar to MR-1 in its anaerobic growth on several electron acceptors, including fumarate, TMAO, DMSO, thiosulfate, and tetrathionate (Table 3). The growth of OMCA1 was also very similar to that of MR-1 under aerobic conditions (not shown). OMCA1 also reduced many electron acceptors (nitrate, ferric citrate, FeOOH, and AQDS) under anaerobic conditions at rates that were very similar to those observed with MR-1 (Table 4). The rates of reduction of amorphous FeOOH by all strains were much lower than those with ferric citrate; this was expected, because not only is FeOOH insoluble, but autoclaving FeOOH generates a more crystalline large particulate form which is reduced much more slowly by MR-1 than is ferric citrate. However, the ability of OMCA1 to reduce δMnO2 was partially but significantly compromised (approximately 55% of the activity of MR-1) (Table 4), suggesting that OmcA contributes to, but is not absolutely essential for, the reduction of MnO2.

TABLE 3.

Anaerobic growth on various electron acceptors by strains of S. putrefaciens

| Strain (plasmid) | Growtha

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fumarate | TMAO | DMSO | Thiosulfate | Tetrathionate | None | |

| MR-1(pVK100) | 0.128 ± 0.001 | 0.107 ± 0.002 | 0.062 ± 0.002 | 0.096 ± 0.017 | 0.025 ± 0.013 | 0.004 ± 0.003 |

| OMCA1(pVK100) | 0.130 ± 0.004 | 0.119 ± 0.006 | 0.060 ± 0.003 | 0.088 ± 0.013 | 0.030 ± 0.007 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

Growth is reported as maximum increase in culture turbidity (optical density at 500 nm) observed over a period of 4 days. Allvalues represent means ± high-low-range for two parallel but independent experiments.

TABLE 4.

Anaerobic reduction of various electron acceptors by strains of S. putrefaciens

| Strain (plasmid) | Reductiona

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe(III) citrateb | FeOOHb | Nitratec | AQDSd | δMnO2b | |

| MR-1(pVK100) | 79.1 ± 1.8 | 0.04 ± 0.00 | 29.7 ± 0.1 | 0.915 ± 0.007 | 0.44 ± 0.02 |

| OMCA1(pVK100) | 76.1 ± 0.7 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 29.7 ± 0.1 | 1.041 ± 0.068 | 0.24 ± 0.01 |

All values represent means ± high-low range for two parallel but independent experiments.

Rate of formation of Mn(II) or Fe(II) (in micromoles per day in a 16-ml or 13-ml culture, respectively) to the point of maximum reduction observed over a period of 4 days.

Rate of nitrate loss (in micromoles per day in a 13-ml culture) to the point of maximum loss observed over a period of 4 days

Maximum increase in product formation (absorbance at 395 nm) observed over a period of 4 days.

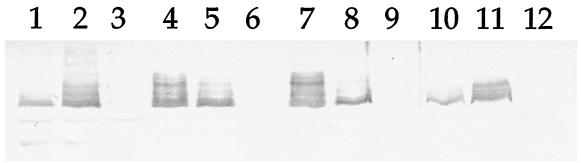

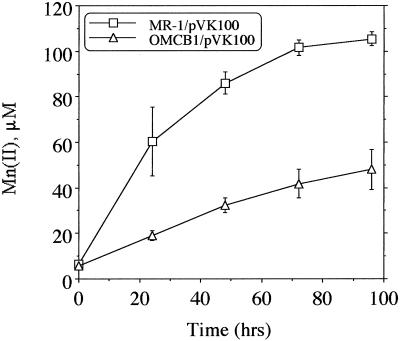

Similarly, OMCB1 retained the ability to grow on or reduce most electron acceptors, including Fe(III), at rates that were comparable to those of MR-1 (not shown). However, OMCB1 was markedly deficient in its ability to reduce MnO2, with rates that were only about 25% of those observed with MR-1 (Fig. 9). OMCB2 was similar to OMCB1 in that it was markedly compromised in its ability to reduce MnO2(not shown).

FIG. 9.

Reduction of δMnO2 by MR-1 and OMCB1 under anaerobic conditions as determined by the formation of Mn(II) over time. The points represent the means for an n of 2, and the bars represent the range of high and low values; for points lacking apparent range bars, the bars were smaller than the points as shown.

DISCUSSION

Depending on the gel length, percent acrylamide, and protein markers used, purified OmcB or OmcB in OM fractions migrated with an apparent molecular mass of 53 to 62 kDa. This is consistent with values of 53 to 60 kDa reported previously (23, 24). Based on the DNA sequence, mature OmcB would have a predicted molecular mass of 75.7 kDa, which accounts for the cleavage of the hydrophobic leader sequence, the addition of the 10 covalently attached c-type hemes, and the estimated mass of the lipoprotein modification to the N-terminal cysteine. Given the exact match at the N terminus (Fig. 1B), this suggests that 15 to 20 kDa of the C terminus may have been proteolytically cleaved, either in vivo or during the lengthy cellular subfractionation process. Alternatively, some OM proteins migrate anomalously in SDS-PAGE, and it is possible that OmcB is another such example.

The ability of gram-negative metal-reducing bacteria to obtain energy for growth via the reduction of insoluble Fe(III) and Mn(IV) oxides under anaerobic conditions implies the existence of a mechanism to link their electron transport systems to the reduction of extracellular metal oxides. The localization of cytochromes to the OM of anaerobically grown MR-1 (23, 24) suggests a possible mechanism by which electrons could be transferred to metal oxides at the cell surface. The data reported here are consistent with a role for OM cytochromes in the reduction of Mn(IV)—the omcA and omcB knockout strains could still reduce MnO2, but at rates that were only 55 and 25%, respectively, of those observed for MR-1. This is consistent with the previous observation that the cytochromes in isolated OMs could be oxidized by Mn(III) (24). However, it is not known if one or more of the OM cytochromes are the terminal Mn(IV) reductase(s) or if they serve as intermediate electron transport components with some other noncytochrome OM-localized component(s) serving as the terminal Mn(IV) reductase(s). Since four OM cytochromes are distinguishable by heme-stained SDS-PAGE gels (24), it is possible that some serve as intermediate carriers and others serve as terminal reductases. Given the highly insoluble nature of MnO2 and other naturally occurring Mn oxides, the terminal Mn(IV) reductase(s) would presumably have to be exposed on the outer surface of the OM. Crossed immunoelectrophoresis experiments are consistent with the exposure of OmcA and at least one other cytochrome on the outer faces of the OMs of MR-1 cells (C. R. Myers, unpublished data). The OmcA homolog in S. frigidimarina NCIMB400 is also likely exposed at the exterior face of the OM, and the midpoint reduction potentials of its hemes are consistent with an ability to transfer electrons to MnO2 (8). One or more of the OM cytochromes of MR-1, therefore, remain possible candidates for the terminal Mn(IV) reductase(s).

The data for strain OMCA1, which lacks OmcA, suggest the presence of more than one Mn(IV) reductase. This strain is still able to reduce MnO2 but does so at a rate only 55% of that of MR-1 (Table 4). This is consistent with a significant role for OmcA in Mn(IV) reduction but implies the existence of at least one alternative Mn(IV) reduction component. The OM cytochromes likely participate in the OmcA-independent mechanism(s); OMCB1 is devoid of OmcB but is also markedly deficient in other OM cytochromes—it reduces MnO2 but at only about 25% of the rate of MR-1 (Fig. 9). The pleiotropic effects on the proper localization of other OM cytochromes, however, complicate interpretation of the exact role of OmcB in Mn(IV) reduction. The low rate of Mn(IV) reduction by the omcB mutants could be mediated by the limited remaining cytochrome content in the OM (Fig. 6 and 7). Alternatively, since these strains still reduce Fe(III) and since Fe(II) is a potent reductant of Mn(IV) (28), the redox cycling of the 5.4 μM Fe in the medium might support or contribute to their low rate of Mn(IV) reduction.

Mutants OMCA1 and OMCB1 were not hampered in their ability to reduce other electron acceptors, including ferric citrate and FeOOH. Since MnO2 is insoluble, it was important to confirm the ability to reduce insoluble FeOOH, demonstrating that the OM cytochromes do not merely distinguish between soluble and insoluble metal oxides.

The majority of formate-dependent Fe(III) reductase activity is localized to the OM of MR-1 (20), and the cytochromes in the OM fraction purified from MR-1 can be oxidized by ferric citrate (24). The OmcA analog from S. frigidimarina NCIMB400 is able to rapidly transfer electrons to Fe(III) EDTA, and redox midpoint potentials of its heme groups are consistent with this ability (8). However, since OMCA1 and OMCB1 reduce Fe(III) at rates indistinguishable from those of MR-1, it seems unlikely that the OM cytochromes of MR-1 play a significant role in Fe(III) reduction in intact cells. This seems especially true since all OM cytochromes were greatly diminished in the omcB mutants (Fig. 6 and 7). The data suggest that there are one or more components which are different in the Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reductase systems of MR-1; this is consistent with early studies, in which nitrosoguanidine-generated mutants of MR-1 were isolated, some of which were specifically deficient in either Mn(IV) or Fe(III) reduction (27). While it is possible that OmcA and OmcB contribute to Fe(III) reduction in MR-1, neither is essential for Fe(III) reduction, and their potential contribution to Fe(III) reduction is likely limited, at best, since the mutants still reduce Fe(III) at wild-type rates. The ability of Fe(III) to oxidize OM cytochromes in vitro (24) may not accurately reflect an in vivo role; Cr(VI) can also readily oxidize the OM cytochromes of MR-1 (Myers, unpublished), even though the Cr(VI) reductase activity in MR-1 is localized in the CM (16).

Other strains of S. putrefaciens and S. frigidimarina contain OmcA homologs (8, 30), and it is possible that OmcA in these other strains might play a more significant or essential role in Fe(III) reduction. The mechanism of Fe(III) reduction in MR-1 could also be independent of the OM cytochromes. A recent report suggests that a small unidentified quinone excreted by MR-1 might serve as an electron shuttle to extracellular insoluble electron acceptors (32); it is also possible that this small quinone may only enable menaquinone-minus mutants to synthesize menaquinone, which is known to be essential for the reduction of Mn(IV) and Fe(III) by MR-1 (25, 31). The OM of anaerobically grown MR-1 also has a significant content of noncytochrome redox-active proteins (Myers, unpublished), so it is possible that these other OM proteins could mediate Fe(III) reduction.

OmcA and other OM cytochromes likely receive their electrons from electron transport components in the CM. It has previously been shown that mutants which lack menaquinone or CymA, a 21-kDa tetraheme cytochrome presumably anchored to the outer face of the CM, are markedly deficient in Mn(IV) reduction (18, 25, 31). CymA is a member of the NapC/NirT family of CM-associated c-type cytochromes, which are postulated to accept electrons from quinols (e.g., menaquinol) and to transfer them to downstream components outside the CM. In support of this, the putative CymA homolog in S. frigidimarina NCIMB4000 serves as a quinol oxidase (8). Since menaquinone, CymA, OmcA, and at least one other OM cytochrome are involved in Mn(IV) reduction, an electron transport link from menaquinone to CymA to OM cytochromes is likely. The natures of the components which facilitate this link are not known, but possibilities include periplasmic electron transport components, or “direct” contact between CM and OM components at adhesion sites. Specific links between the CM and OM have been described, e.g., energy-coupled transport mediated via the TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex (4). The menaquinone-CymA system does not supply electrons for Mn(IV) reduction alone, however, as these components are also required for the reduction of fumarate, nitrate, and Fe(III) (18, 25, 31).

The pleiotropic effect of the omcB gene replacement on the levels of other OM cytochromes does not represent a lack of heme c synthesis or a defect in cytochrome c maturation because the levels and species of cytochromes in the CMs and soluble fractions of these mutants are very similar to those in MR-1 (Fig. 6 and 7). The two other OM cytochrome genes (mtrF and omcA) identified to date from analysis of the preliminary MR-1 genome data (obtained from TIGR) lie just upstream of omcB. An insertion in omcB should therefore not have a polar effect on these upstream genes, both of which are transcribed independently from omcB. In fact, RT-PCR demonstrated that the genes immediately upstream and downstream from omcB (omcA and mtrA-mtrB, respectively) continue to be expressed in OMCB1 (Fig. 4). Furthermore, Western blot analysis demonstrated that OMCB1 contains OmcA, but it is mislocalized to the CM and soluble fractions rather than to the OM (Fig. 8). While antibodies to MtrA and MtrB, which are translated from a polycistronic mRNA (Fig. 4), are not available, it is likely that OMCB1 contains sufficient levels of MtrB, because the absence of MtrB should render them unable to reduce Fe(III) (2). The mechanism by which interruption of omcB results in decreased levels of multiple OM cytochromes is not known; one possibility is that OmcB is somehow necessary for the proper localization of these other cytochromes to the OM. Exactly how OmcB might do this is not known at this time and is the subject of ongoing investigation.

In summary, using a site-directed gene replacement approach, omcA and omcB knockout strains were generated directly from MR-1. The omcA mutant specifically lacked OmcA and was partially (55% of wild-type) deficient in Mn(IV) reduction. The omcB mutants lacked OmcB and were significantly (25% of wild-type) deficient in Mn(IV) reduction. However, the omcB mutants were also markedly to totally deficient in other OM cytochromes; this pleiotropic effect was unexpected and is not likely to represent lack of synthesis of the relevant proteins, e.g., the mutants still synthesize OmcA but it is not properly localized to the OM. The mutants were not affected in their use of other anaerobic electron acceptors, including Fe(III). Together, the data suggest that OmcA and at least one other OM cytochrome contribute significantly to Mn(IV) reduction but that the OM cytochromes are not essential for normal rates of Fe(III) reduction. The original hypothesis that these OM cytochromes provide an electron transport link to extracellular metal oxides appears to be true for Mn(IV) but not for Fe(III).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01GM50786 to C.R.M.

We are grateful to V. L. Miller and D. Frank for graciously providing pEP185.2 and pUT/mini-Tn5Km, respectively. The preliminary genomic sequence data was obtained from TIGR through the website at http://www.tigr.org. Sequencing of S. putrefaciens MR-1 genomic DNA by TIGR was accomplished with support from the Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong P B, Lyons W B, Gaudette H E. Application of formaldoxime colorimetric method for the determination of manganese in the pore water of anoxic estuarine sediments. Estuaries. 1979;2:198–201. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beliaev A S, Saffarini D A. Shewanella putrefaciens mtrB encodes an outer membrane protein required for Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6292–6297. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6292-6297.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berks B C, Richardson D J, Reilly A, Willis A C, Ferguson S J. The napEDABC gene cluster encoding the periplasmic nitrate reductase system of Thiosphaera pantotropha. Biochem J. 1995;309:983–992. doi: 10.1042/bj3090983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun V. Energy-coupled transport and signal transduction through the Gram-negative outer membrane via TonB-ExbB-ExbD-dependent receptor proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;16:295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewer P G, Spencer D W. Colorimetric determination of manganese in anoxic waters. Limnol Oceanogr. 1971;16:107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cataldo D A, Haroon M, Schrader L E, Youngs V L. Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 1975;6:71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K N. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertional mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field S J, Dobbin P S, Cheesman M R, Watmough N J, Thomson A J, Richardson D J. Purification and magneto-optical spectroscopic characterization of cytoplasmic membrane and outer membrane multiheme c-type cytochromes from Shewanella frigidimarina NCIMB400. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8515–8522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayashi S, Wu H C. Lipoproteins in bacteria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1990;22:451–471. doi: 10.1007/BF00763177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinder S A, Badger J L, Bryant G O, Pepe J C, Miller V L. Cloning of the YenI restriction endonuclease and methyltransferase from Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O8 and construction of a transformable R−M+ mutant. Gene. 1993;136:271–275. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90478-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knauf V C, Nester E W. Wide host range cloning vectors: cosmid clone bank of Agrobacterium Ti plasmids. Plasmid. 1982;8:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(82)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovley D R, Coates J D, Blunt-Harris E L, Phillips E J P, Woodward J C. Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature. 1996;382:445–448. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovley D R, Phillips E J P. Organic matter mineralization with reduction of ferric iron in anaerobic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:683–689. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.4.683-689.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris C J, Black A C, Pealing S L, Manson F D C, Chapman S K, Reid G A, Gibson D M, Ward B F. Purification and properties of a novel cytochrome: flavocytochrome c from Shewanella putrefaciens. Biochem J. 1994;302:587–593. doi: 10.1042/bj3020587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers C R, Carstens B P, Antholine W E, Myers J M. Chromium(VI) reductase activity is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane of anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;88:98–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myers C R, Collins M L P. Cell-cycle-specific oscillation in the composition of chromatophore membrane in Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:818–823. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.818-823.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myers C R, Myers J M. Cloning and sequence of cymA, a gene encoding a tetraheme cytochrome c required for reduction of iron(III), fumarate, and nitrate by Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1143–1152. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.4.1143-1152.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers C R, Myers J M. Ferric iron reduction-linked growth yields of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;76:253–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1994.tb01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myers C R, Myers J M. Ferric reductase is associated with the membranes of anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;108:15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myers C R, Myers J M. Fumarate reductase is a soluble enzyme in anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;98:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers C R, Myers J M. Isolation and characterization of a transposon mutant of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 deficient in fumarate reductase. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;25:162–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers C R, Myers J M. Localization of cytochromes to the outer membrane of anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3429–3438. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3429-3438.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myers C R, Myers J M. Outer membrane cytochromes of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1: spectral analysis, and purification of the 83-kDa c-type cytochrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1326:307–318. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myers C R, Myers J M. Role of menaquinone in the reduction of fumarate, nitrate, iron(III) and manganese(IV) by Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers C R, Nealson K H. Bacterial manganese reduction and growth with manganese oxide as the sole electron acceptor. Science. 1988;240:1319–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.240.4857.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers C R, Nealson K H. Iron mineralization by bacteria: metabolic coupling of iron reduction to cell metabolism in Alteromonas putrefaciens strain MR-1. In: Frankel R B, Blakemore R P, editors. Iron biominerals. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1990. pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Myers C R, Nealson K H. Microbial reduction of manganese oxides: interactions with iron and sulfur. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1988;52:2727–2732. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myers C R, Nealson K H. Respiration-linked proton translocation coupled to anaerobic reduction of manganese(IV) and iron(III) in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6232–6238. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6232-6238.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Myers J M, Myers C R. Isolation and sequence of omcA, a gene encoding a decaheme outer membrane cytochrome c of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1, and detection of omcA homologs in other strains of S. putrefaciens. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1373:237–251. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers J M, Myers C R. Role of the tetraheme cytochrome CymA in anaerobic electron transport in cells of Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1 with normal levels of menaquinone. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:67–75. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.67-75.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newman D K, Kolter R. A role for excreted quinones in extracellular electron transfer. Nature. 2000;405:94–97. doi: 10.1038/35011098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ochman H, Gerber A S, Hartl D L. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction. Genetics. 1988;120:621–623. doi: 10.1093/genetics/120.3.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quandt J, Hynes M F. Versatile suicide vectors which allow direct selection for gene replacement in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1993;127:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghava G P S. Improved estimation of DNA fragment length from gel electrophoresis data using a graphical method. BioTechniques. 1994;17:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host-range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townsend K M, Frost A J, Lee C W, Papadimitriou J M, Dawkins H J S. Development of PCR assays for species- and type-specific identification of Pasteurella multocida isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1096–1100. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1096-1100.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van'T Riet J, Stouthamer A H, Planta R J. Regulation of nitrate assimilation and nitrate respiration in Aerobacter aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:1455–1464. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.5.1455-1464.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]