Abstract

In order to determine the mechanisms involved in the persistence of extracellular DNA in soils and to monitor whether bacterial transformation could occur in such an environment, we developed artificial models composed of plasmid DNA adsorbed on clay particles. We determined that clay-bound DNA submitted to an increasing range of nuclease concentrations was physically protected. The protection mechanism was mainly related to the adsorption of the nuclease on the clay mineral. The biological potential of the resulting DNA was monitored by transforming the naturally competent proteobacterium Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413, allowing us to demonstrate that adsorbed DNA was only partially available for transformation. This part of the clay-bound DNA which was available for bacteria, was also accessible to nucleases, while the remaining fraction escaped both transformation and degradation. Finally, transformation efficiency was related to the perpetuation mechanism, with homologous recombination being less sensitive to nucleases than autonomous replication, which requires intact molecules.

In the environment, three mechanisms are thought to be involved in gene uptake by bacteria (31), namely, conjugation, transformation, and transduction. Natural bacterial genetic transformation is the mechanism by which a bacterium acquires naked DNA. Such a mechanism is thought to have been involved in gene transfers during evolution and particularly in transfers among unrelated organisms such as plants and bacteria (1, 8, 21). However, numerous reports indicate that gene transfer events may be very rare in the environment (14, 18, 33). This could be due to the numerous steps that are required to achieve transformation. DNA released by organisms must persist under adverse conditions such as those encountered in soils. Naked DNA must then encounter competent recipient bacteria. Moreover, the incorporated DNA will only be perpetuated if its nucleotide sequences exhibit sufficient similarity to the recipient genome to allow recombination, unless the sequences possess a replicon which is operational in the new host (14, 16, 33).

Nevertheless, there is a general agreement that natural transformation may occur in complex media such as soils. Indeed, large amounts of naked DNA, which is the preliminary key factor for transformation, can be detected in soils (7, 35, 40). Moreover, there is much evidence that extracellular DNA can persist for periods of time up to several months or years (8, 18, 25, 27, 28, 38). Adsorption of DNA on soil components, particularly on clay minerals such as montmorillonite, illite, and kaolinite, is thought to be involved in protection of nucleic acids against nucleases, and could explain the high content of DNA in soils (2, 10, 32). However, soil or microcosm-based experiments have indicated that the adsorption-related protection process has only limited impact (3, 17, 25, 27). In fact, very little is known about the protection mechanism itself, and the influence of parameters such as clay type, the size of DNA or its conformation. For instance, does adsorption physically prevent DNA from being attacked by nucleases? Or is protection related to adsorption of enzymes on clay, which induces conformation alterations leading to a decrease in activity (11, 17, 24, 33, 34)? Moreover, how is the remaining clay-adsorbed DNA available for bacterial transformation, and what are the consequences of a partial protection on the transformation efficiency? Finally, will partial degradation have the same effect on transformation frequencies when the processing of the transforming DNA in the bacterial cell occurs via homologous recombination or autonomous replication?

In this study, we developed simple models to investigate the protection mechanism related to DNA adsorption onto clay particles and the balance existing between degradation and persistence of DNA. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to determine the role that adsorption of DNA and nuclease could play in preventing DNA degradation. Proteins such as DNase I and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were used in combination with plasmid DNA in the presence of clay minerals. Particular emphasis was focused on illite, which is a common clay mineral in soils of temperate regions (6). The biological consequences of adsorption and protection were monitored by transforming the highly efficient naturally competent proteobacterium Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 with the DNA resulting from the various tested conditions (4, 20). Insight into the different fates which could characterize a similar gene originating from different hosts or even replicons can be deduced from the fact that of the two plasmids we used, one was able to replicate autonomously in the bacterium while the genes of the second plasmid could only be integrated into the host genome via homologous recombination.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, media, and DNA.

Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 was grown in Luria Bertani (LB) medium (containing [per liter] 10 g of Bacto Tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract, and 5 g of NaCl). Natural transformation was processed in parallel in LB medium and in LBm medium (LB medium plus [per liter] 5 g of Bacto Tryptone and 2.5 g of yeast extract) according to the protocol described below. Plasmid pGV1 (3.95 kb) (37), containing an nptII gene conferring resistance to kanamycin, replicates autonomously in Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 after transformation. Plasmid pAVA213-8 (10.5 kb) (19), a pUC18-based plasmid containing an nptII gene is unable to replicate in Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413. Presence of a 6.4-kb chromosomal DNA fragment from Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 permitted integration of the marker gene into the genome by homologous recombination. Both plasmids were extracted from Escherichia coli strains and purified with a kit from Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif., according to manufacturer's recommendations and stored in sterile purified water (milliQ) at −20°C.

DNA sorption on clay minerals.

Properties of the clay minerals used in this study are presented in Table 1. Adsorption was effected by mixing DNA with clay in 1.5 ml of polyallomer centrifuge tubes, providing a final concentration of DNA at 12.5 μg ml−1 and of clay at 15 mg ml−1 (22). The adsorption process was run by shaking the tubes at 23°C in a thermomixer (Roucaire, Courtabouef, France) at 1,200 rpm for 2 h, followed by a centrifugation at 15,000 × g and 4°C for 20 min to settle all clay particles. The pellet was washed twice by 2 volumes of sterile water. Final concentrations were 30 mg of clay ml−1 and 25 μg of DNA ml−1, corresponding to a complete adsorption of DNA, which was verified on an agarose gel.

TABLE 1.

Main characteristics of the Ca-clays used in this study

| Clay mineral | Origin | Cation exchange capacity (cmol kg−1) | Specific surface area (m2 g−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolinite | St. Austell, United Kingdom | 4 | 12 |

| Illite | Le Puy, France | 24.5 | 122 |

| Montmorillonite | Wyoming, United States | 90 | 800 |

Desorption of bound DNA was carried out on pellets resulting from centrifugation of 10 μl of adsorbed DNA (15,000 × g, 4°C, 20 min), by adding 10 μl of a saline solution containing 17 mM lactic acid, 3 mM KH2PO4, 27 mM Na2HPO4, 0.23 mM MgSO4, 11 mM NH4Cl, 19 μM CaCl2, 0.5 μM FeSO4, 86 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and 57 mM EDTA. The desorption was run out for 1 h at 23°C with vigorous shaking (thermomixer at 1,200 rpm), and the resulting mixture was electrophoresed on an agarose gel (0.8%).

The effect of the composition of culture medium on DNA sorption was investigated as follows. Ten microliters of adsorbed DNA, in the presence of illite, with and without BSA, and 10 μl of sterile water were mixed to achieve the same concentrations as in the transformation assays. Sterile water or culture media (LB and LBm) were added to provide a final volume of 200 μl, and these mixtures were incubated for 90 min at 29°C. Tubes were then centrifuged 20 min at 15,000 × g and 4°C, and molecules in the supernatant were precipitated by ethanol. Precipitated pellets were resuspended in 10 μl of sterile water and loaded on 0.8% agarose gel to detect desorbed DNA.

BSA adsorption.

BSA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was diluted in water and dialyzed against sterile purified water. A solution containing BSA (20 mg ml−1) was added volume to volume to clay-DNA complexes. Adsorption was carried out extemporaneously by shaking the tubes at 23°C in a thermomixer (Roucaire) at 1,200 rpm for 1 h, followed by centrifugation for 20 min at 4 °C and 15,000 × g. The nonadsorbed proteins were removed by rinsing the pellet twice with 2 volumes of pure sterile water. The final concentration of adsorbed DNA was maintained at 25 μg ml−1.

DNase-mediated degradation tests.

Bovine pancreas DNase I grade II (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) was diluted in water to avoid bias resulting from interaction of the enzyme with divalent cations. Sterile DNase I solutions were prepared by filtration through cellulose acetate filters (pore size, 0.2 μm). Ten microliters of DNA at 25 μg ml−1, free or adsorbed on clay particles, with or without BSA, and 10 μl of DNase I at concentrations ranging from 0 to 20 μg ml−1 were mixed together. Resulting mixtures were kept on ice before incubation for 15 min at 37°C on a horizontal shaker with a 110-rpm agitation.

Transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413.

An overnight culture of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 was diluted 25-fold into fresh medium and cultured for an additional 2 h at 29°C. A bacterial suspension volume of 180 μl was added to 20 μl of DNA, free or adsorbed and with or without BSA, previously submitted to the DNase I. Resulting mixtures were thoroughly mixed and incubated for 90 min at 29°C. After incubation, reaction tubes were chilled on ice. In a parallel control experiment, DNA was replaced by water.

Antibiotic resistant transformants were selected on LB medium containing kanamycin (50 μg ml−1). Colonies were counted after 2 or 3 days of incubation at 29°C. Results were expressed in number of transformants per ml of culture because the total number of cells was 3.4 × 108 ± 4.9 × 107 cells ml−1 in all experiments. Three to five repetitions were carried out for each sample.

In parallel, clay particles, including kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite, on which plasmid DNA had been adsorbed were incubated in culture media according to the previous conditions (200 μl as final volume, 90 min at 29°C). After centrifugation, precipitated molecules present in the supernatant of samples were electrophoresed on an agarose gel.

RESULTS

Physical protection of DNA by clay minerals.

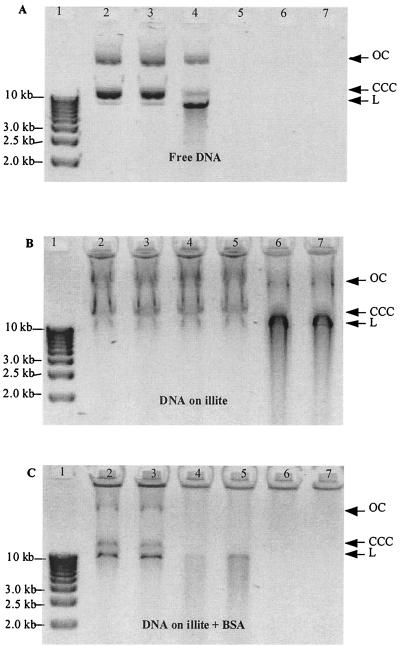

Electrophoresis of isolated plasmids indicated that molecules were mainly under a covalently closed circular (CCC) form, also called supercoiled, with open circular and linear forms also being detected (Fig. 1A, lane 2). The first step of the experiment was to incubate this free DNA with different concentrations of DNase I (Fig. 1A). The smallest concentration used (0.1 μg ml−1) did not produce any change in the plasmid pattern (lane 3). An increase of the concentration of the DNase I to 0.5 μg ml−1 led to a shift among the relative amounts of the various plasmid conformations (lane 4). A drop of the CCC form corresponded to a strong increase of the linear form. When the enzyme reached a concentration of 1 μg ml−1, DNA was totally degraded (lane 5).

FIG. 1.

Detection of action of DNase I on plasmid pAVA213-8. (A) Free DNA; (B) DNA adsorbed on illite; (C) DNA adsorbed on illite saturated with BSA. Lane 1: smart ladder (Eurogentec); lanes 2 to 7, 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 μg of DNase I ml−1, respectively. Abbreviations: CCC, covalently closed circular form; OC, open circular form; L, linear form.

In parallel, plasmid DNA at the same concentration as previously used was adsorbed on illite before being submitted to the various nuclease treatments. Electrophoresis of clay-bound DNA did not permit its direct detection on the gel (data not shown); thus, a desorption step before electrophoresis was processed on all samples. Plasmid profiles (Fig. 1B) appeared fuzzy due to a migration of persisting clay particles still bound to DNA. However the three conformations of the plasmid were still distinguishable. The pattern corresponding to DNase I untreated DNA (lane 2) was still detected when illite-adsorbed plasmid molecules were submitted to DNase I concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1 μg ml−1 (lanes 3 to 5). Finally, even for the 5 and 10 μg ml−1 DNase I concentrations, DNA was still detected, although plasmid conformation was shifted from CCC to linear forms (lanes 6 and 7).

The same experimental procedures were used with illite-bound DNA submitted to a BSA adsorption process before any DNase treatment. We found that the plasmid patterns were less fuzzy than previously (Fig. 1C) and exhibited a greater similarity to the profiles obtained with naked DNA (Fig. 1A) than those exhibited in Fig. 1B (illite-bound DNA without BSA). Patterns corresponding to untreated (Fig. 1C, lane 2) and 0.1 μg ml−1 DNase I-treated (Fig. 1C, lane 3) DNA were similar, while the two following DNase concentrations produced the shift to the linear form (lanes 4 and 5). Increasing nuclease concentration to 5 μg ml−1 led to a complete degradation of DNA (lane 6).

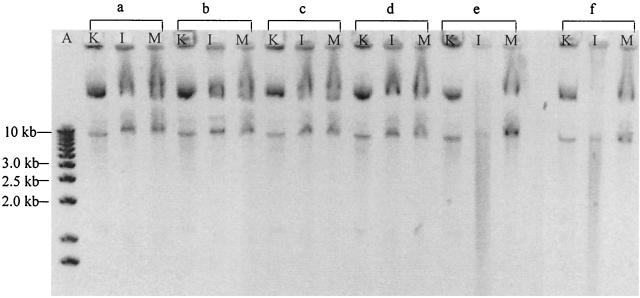

In a second step, plasmid DNA was adsorbed onto kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite to be submitted to the same nuclease concentrations as previously (Fig. 2). DNA was detected for all DNase concentrations (lanes a to f) and patterns were quite similar. The only exceptions were detected for the 5 and 10 μg ml−1 DNase concentrations which provided the shift to linear forms when plasmid DNA was adsorbed on illite (lanes e and f) as previously demonstrated on Fig. 1B.

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the protective role of three clay minerals—kaolinite (K), illite (I), and montmorillonite (M)—against nuclease degradation by 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, and 10 μg of DNase I ml−1 (lanes a to f, respectively).

Transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413.

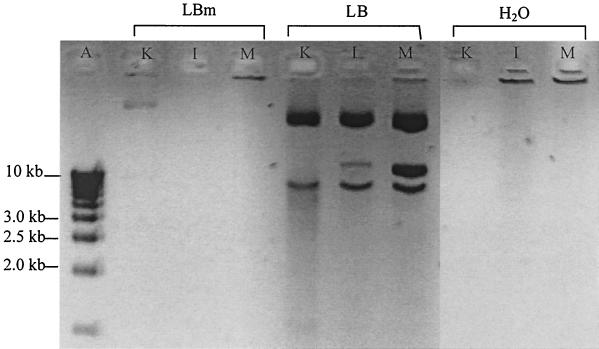

Clay particles, including kaolinite, illite, and montmorillonite, on which plasmid DNA had been adsorbed were incubated in culture media according to the conditions used to transform Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413. Figure 3 clearly demonstrates that large amounts of DNA were desorbed by LB medium regardless of the clay tested. On the other hand, such an effect was not noticed with the LBm medium, which exhibited a lower salt content than the LB medium. The same result was obtained when incubation occurred in sterile purified water (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Effect of the type of culture medium on sorption of DNA to the three clay minerals kaolinite (K), illite (I), and montmorillonite (M). Clay-bound DNA (20 μl) was incubated 1 h 30 min at 29°C with 180 μl of each of the three media tested before centrifugation and electrophoresis of the precipitated molecules present in the supernatant of samples. Lane A contains smart ladder. LBm is a low-salt concentrated medium, and LB is a high-salt concentrated medium. H2O, ultra pure sterile water.

Transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 was found to decrease from 1 to 2 orders of magnitude in the LBm medium compared to the LB medium, as evidenced by the use of free DNA with frequencies dropping from 9.1 × 107 to 5.8 × 106 T ml−1 for pAVA213-8 and from 1.7 × 106 to 8.5 × 103 T ml−1 for pGV1 (Table 2) (where T stands, for transformants).

TABLE 2.

Transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 in the absence of DNase Ia

| Medium | DNA state | pAVA213-8 (T ml−1) | pGV1 (T ml−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LB | Free | 9.1 × 107 ± 1.0 × 107 | 1.7 × 106 ± 1.0 × 105 |

| Adsorbed on illite | 9.0 × 107 ± 9.0 × 106 | 7.8 × 105 ± 1.1 × 105 | |

| LBm | Free | 5.8 × 106 ± 5.1 × 105 | 8.5 × 103 ± 8.9 × 102 |

| Adsorbed on illite | 1.5 × 106 ± 1.7 × 105 | 1.2 × 103 ± 4.5 × 102 |

Results were given as the mean of transformants ± standard error, as the total number of cells was 3.4 × 108± 4.9 × 107 ml−1 in all experiments.

When transforming DNA was previously adsorbed on illite, the number of transformants was nearly identical to that obtained with free DNA for the plasmid pAVA213-8, as only a 1% reduction was observed (Table 2), while a decrease of 54% was detected for transformations conducted in LB medium with plasmid pGV1. In the LBm medium, a marked decrease was observed between free and adsorbed conditions, reaching a reduction of 74% for pAVA213-8 and 86% for pGV1.

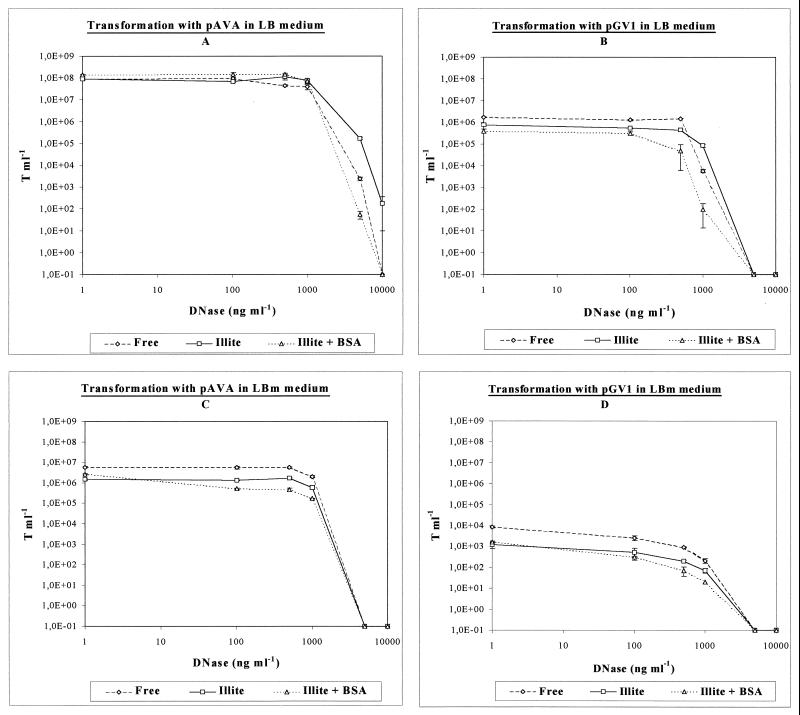

When submitted to an increasing range of DNase I concentrations, the transformant numbers were found to change in similar ways whatever the conditions tested (Fig. 4). This included a first range of concentrations for which the number of transformants remained identical to untreated DNase conditions. The various curves indicated that in a second step an increase of the nuclease concentration led to a more or less marked decrease of transformation efficiencies until the detection limit was reached. Evolution of the number of transformants when experiments were conducted in LBm were found to be very similar between free DNA and illite adsorbed DNA with or without BSA (Fig. 4C and D). On the other hand, the three curves resulting from experiments conducted in LB medium differed for the highest nuclease concentrations (Fig. 4A and B). For instance, when Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 was transformed with illite-bound DNA, plasmid pAVA213-8 submitted to 10 μg of DNase I ml−1 provided 1.8 × 102 recombinant clones, while this number dropped below the detection limit under the two other conditions (Fig. 4A). For plasmid pGV1, a DNase I (1 μg ml−1) treatment produced a decrease from 8.4 × 104 T ml−1 with an illite-adsorbed DNA inoculum to 5.8 × 103 T ml−1 with free DNA and 100 T ml−1 under conditions including BSA (Fig. 4B). Transformations processed in LB medium clearly indicated that plasmid pGV1 exhibited a greater sensitivity to the highest nuclease concentrations than plasmid pAVA213-8, as evidenced by the DNase I concentration of 5 μg ml−1 which did not allow any transformant to develop. Moreover, in the LBm medium, a gradual decrease of the number of transformants was noticed for pGV1, while the slope of the curves characterizing pAVA213-8 was initially gentle and became steeper for the highest nuclease concentrations.

FIG. 4.

Transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 by two types of plasmid DNA in two different media. (A) Transformation with pAVA213-8 in LB medium; (B) transformation with pGV1 in LB medium; (C) transformation with pAVA213-8 in LBm medium; (D) transformation with pGV1 in LBm medium. Results were given as the mean of transformants ± standard error (error bars), as the total number of cells was 3.4 × 108 ± 4.9 × 107 ml−1 in all experiments; the axes represented data on a logarithmic scale.

DISCUSSION

Physical protection of DNA adsorbed on clay minerals.

The first objective of our experiments was to confirm that soil components provide some physical protection to extracellular DNA, which is naturally released in soils. We focused our study on the effect of clay minerals because of their essential implication in soils (5, 14, 32, 36). Comparison of Fig. 1A and B clearly demonstrates the protective effect of illite for DNA against nucleases; the effect was confirmed for the two other clays (Fig. 2). However, illite exhibited less efficiency for the highest nuclease concentrations (Fig. 2, lanes e and f). Intact CCC molecules or linearized forms resulting from nuclease nicks were still detected when DNA was bound on the clays in presence of DNase concentrations which would have totally degraded free DNA. These results confirm that adsorption provides a physical protection to DNA which relies on the type of the adsorbent (3, 10, 11, 26, 36).

Protection mechanism.

Two hypotheses can be proposed to explain this protection mechanism. First, the clay mineral could be considered as a niche providing DNA physical protection from nuclease. An alternative hypothesis would involve simultaneous adsorption of the enzyme on the clay, physically separating the enzyme from its substrate. To examine this, we decided to prevent DNase I from adsorbing onto illite by saturating potential sites with another nonenzymatic protein (BSA) at a concentration guaranteeing complete saturation (9, 23, 34). We also verified by agarose gel electrophoresis that the BSA treatment did not desorb any DNA (data not shown).

The results (Fig. 1C) indicate that BSA treatment of illite improved DNase activity by saturating the protein sites. Under these conditions, BSA blocked sorption of DNase I on the clay surface so it remained available to degrade DNA to nearly the same extent as in the absence of illite (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that it is the adsorption of the nuclease on the clay itself that produces the protective effect. Adsorption would physically separate DNA and the nuclease on the clay surface. This statement is in agreement with the fact that bound enzymes usually exhibit reduced activity (5, 11, 13, 24, 29, 32). Furthermore, the lower level of protection found with illite compared to kaolinite and montmorillonite could be due to the higher affinity of DNase I for the two other clay minerals as we have observed recently (unpublished results).

The hypothesis of a protective niche effect cannot be excluded since persisting DNA could still be detected (Fig. 1C, lane 5) after treatment with DNase I at 1 μg ml−1, a concentration which totally degraded free DNA (Fig. 1A, lane 5). This discrepancy could also be due to the persistence of some sites permitting nuclease adsorption in spite of the saturating concentration of BSA we used. However, the conformation and strength of adsorption of both DNA and nuclease depend on the mechanism of adsorption and may affect enzyme-substrate interaction and degree of availability of DNA to uptake for transformation and attack by nucleases in soils.

Biological availability of clay-bound DNA.

When considering extracellular DNA in soils, a fundamental question is related to the ability of these molecules to transform bacteria and thus to be involved in evolution and adaptation mechanisms. The experiments reported by Romanowski et al. (28) indicated a difference between the transformation potential of plasmids inoculated and reextracted from soils and their physical persistence detected by PCR or Southern hybridization. This illustrates the importance of considering both the physical integrity and the biological potential of DNA. We used the natural transformation capacity of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 as a tool to monitor the availability of plasmid DNA adsorbed on illite and the consequences of a DNase treatment.

The first parameter we considered was the chemical effect of the environment on sorption of transforming plasmids to mimic what could occur in soils. We conducted these experiments in two media in which bacterial transformation occurred, although with various efficiencies, but which differed in their desorption potential. Agarose gel electrophoresis clearly demonstrated that most of the bound DNA was desorbed in LB medium, while this effect was not noticed in LBm medium, which exhibited a reduced salt concentration (Fig. 3). When considering transformation in the presence of clay minerals, a question remained about the availability of adsorbed DNA. Are bacteria able to pick up this clay-bound DNA or is a desorption process necessary to release the transforming DNA? Transformation in the nondesorbing medium (LBm) demonstrated that a fraction of adsorbed DNA remained accessible to bacteria, indicating that it could still play a biological role in soil. However, a comparison of the transformation rates in the two media with free and previously adsorbed DNA demonstrated that another part of adsorbed DNA was not available for transformation. Finally, we demonstrated that the LB medium increased DNA availability by desorbing it, as indicated by the number of transformants, similar to that obtained with free DNA (Table 2).

Chamier et al. (3) suggested that DNA adsorbed on mineral surfaces in a sedimentary or soil habitat may be available for transformation of Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413. Their protocol involved bacteria, which were applied to DNA-loaded microcosms in a culture medium containing salts. It is probable that DNA was desorbed from the adsorbent surface by salts when cells were added. Thus, media containing salts should be avoided in experiments monitoring DNA availability. Recently, Sikorski et al. (30) showed that competent cells were able to take up DNA bound on soil particles, even in presence of microorganisms and DNases indigenous to the soil. Introduced cells were washed before introduction in soil extract, and no bias occurred due to culture medium. In agreement with our results, the study by Sikorski et al. (30) showed that bacteria could indeed take up adsorbed DNA. Moreover, our work demonstrates that only a fraction of adsorbed DNA was accessible to bacteria, while for another fraction, adsorption prevented its availability for natural genetic transformation.

Biological protection resulting from DNA adsorption.

When exposed to DNase I, regardless of the conditions (free or adsorbed DNA, with or without BSA), the transformant counts were found to change in similar ways (Fig. 4). In contrast to previous data on the efficiency of illite to physically protect DNA (Fig. 1), a lower protective effect was detected when assessing the bacterial transforming availability of the DNA treated with various nuclease concentrations.

Transformations conducted in the nondesorbing medium (LBm) could lead to the conclusion that illite had no effect on transformation efficiency, as demonstrated by the similarity of data obtained for free and adsorbed DNA (Fig. 4C and D). However, a comparison with the experiments in which DNA was desorbed (Fig. 4A and B) did not confirm this assessment. For the highest nuclease concentrations, the number of transformants was significantly higher in the presence of illite compared to free DNA. This suggests that a part of the adsorbed DNA, which was protected by illite, was not available to transform bacteria. Prevention of the specific nuclease adsorption (presence of BSA) suppressed the protection effect of illite on DNA, confirming that DNA was prevented from being degraded by the adsorption of the nuclease itself on illite, as previously demonstrated on an agarose gel. When environmental conditions led to desorption, this DNA became accessible to both bacteria and nucleases.

Influence of the processing of internalized DNA.

In nonsterile soils, a successful transformation could be processed by integration of the transforming DNA in the host genome by homologous or more or less illegitimate recombination, or by autonomous replication of plasmids. In order to monitor the involvement of such endogenous processes in the perpetuation of genetic information in soils, we used two plasmids differing by their processing in the host cell after DNA uptake. Current knowledge on plasmid transformation in Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 indicates that this mechanism is not dependent on the presence of multimers, as in Bacillus subtilis; that plasmid recircularization is a RecA-independent mechanism; and that chromosomal DNA and plasmid DNA compete for the same uptake system (12, 20). Our study completes these data, as our results indicate that the perpetuation mechanisms affected the biological potential of DNA submitted to nuclease degradation (Fig. 4). A higher sensitivity to nucleases of the replicative plasmid was demonstrated compared to the integrative one. This could be due to the integrity of the molecule which was required to maintain a transforming activity, while partial degradation did not prevent integration of DNA as long as homologous sequences were preserved. This interpretation is supported by the current state of knowledge on integration of chromosomal donor DNA into the recipient chromosome and reconstitution of plasmid DNA molecules after internalization of restricted single-stranded DNA (14, 31, 39).

Our results confirm previous data on the protection effect that the presence of clay minerals in soils provides to extracellular DNA, protection which is mainly related to an efficient adsorption of the nucleases. While the occurrence of natural bacterial transformation in situ cannot be excluded, confirming that gene transfer could occur naturally, numerous factors contribute to maintaining a low frequency of such processes. Adsorption does not provide DNA with a complete protection against nucleases but does significantly decrease its availability for bacteria (15, 27). These macromolecules also have to cope with the changing environmental conditions which certainly lead to rapid switches in the ratio between adsorbed and desorbed DNA. The combination of these various factors could prevent bacteria from acquiring a great amount of genetic information, in particular when the sequences have to be replicated autonomously.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to K. J. Hellingwerf, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, who provided Acinetobacter sp. strain BD413 and plasmids pAVA213-8 and pGV1. Clay minerals were kindly provided by C. Chenu, INRA Versailles, Versailles, France. We are grateful to Stephane Peyrard for technical assistance.

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministère de la Recherche et de l'Education and as part of the Biotechnology program of the Ministère Français de l'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertolla F, Simonet P. Horizontal gene transfers in the environment: natural transformation as a putative process for gene transfers between transgenic plants and microorganisms. Res Microbiol. 1999;150:375–384. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum S A E, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Mechanism of retarded degradation and prokaryotic origin of DNases in non sterile soils. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1997;20:513–521. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamier B, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Natural transformation of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus by plasmid DNA adsorbed on sand and groundwater aquifer material. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1662–1667. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1662-1667.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cruze J A, Singer J T, Finnerty W R. Conditions for quantitative transformation of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Curr Microbiol. 1979;3:129–132. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davet P. Vie microbienne du sol et production végétale. Paris, France: INRA; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchaufour P. L'évolution des sols: essai sur la dynamique des profils. Paris, France: Masson and Cie; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frotegard A, Courtois S, Ramisse V, Clere S, Bernillon D, Le Gall F, Jeannin P, Nesme X, Simonet P. Quantification of bias related to the extraction of DNA directly from soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5409–5420. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5409-5420.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gebhard F, Smalla K. Monitoring field releases of genetically modified sugar beets for persistence of transgenic plant DNA and horizontal gene transfer. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28:261–272. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harter R D, Stotzky G. Formation of clay-protein complexes. Soil Sci Soc Am Proc. 1971;35:383–389. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivarson K C, Schnitzer M, Cortez J. The biodegradability of nucleic acid bases adsorbed on inorganic and organic soil components. Plant Soil. 1982;64:343–353. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khanna M, Stotzky G. Transformation of Bacillus subtilis by DNA bound on montmorillonite and effect of DNase on the transforming ability of bound DNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1930–1939. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1930-1939.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenz M G, Reipschläger K, Wackernagel W. Plasmid transformation of naturally competent Acinetobacter calcoaceticus in non-sterile soil extract and groundwater. Arch Microbiol. 1992;157:355–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00248681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. DNA binding to various minerals and retarded enzymatic degradation of DNA in a sand/clay microcosm. In: Gauthier Michel J., editor. Gene transfers and environment. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 103–113. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Bacterial gene transfer by natural genetic transformation in the environment. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:563–602. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.563-602.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nielsen K M, Van Weerelt M D M, Berg T N, Bones A M, Hagler A N, van Elsas J D. Natural transformation and availability of transforming DNA to Acinetobacter calcoaceticus in soil microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1945–1952. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1945-1952.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen K M. Barriers to horizontal gene transfer by natural transformation in soil bacteria. APMIS. 1998;106:77–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.1998.tb05653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paget E, Jocteur-Monrozier L, Simonet P. Adsorption of DNA on clay minerals: protection against DNase I and influence on gene transfer. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;97:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paget E, Lebrun M, Freyssinet G, Simonet P. The fate of recombinant plant DNA in soil. Eur J Soil Biol. 1998;34:81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmen R, Vosman B, Kok R, van der Zee J R, Hellingwerf K J. Characterization of transformation-deficient mutants of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1747–1754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmen R, Vosman B, Buijsman P, Breek C K D, Hellingwerf K J. Physiological characterization of natural transformation in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:295–305. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-2-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paul J H. Microbial gene transfer: an ecological perspective. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poly F, Chenu C, Simonet P, Rouiller J, Jocteur-Monrozier L. Differences between linear chromosomal and supercoiled plasmid DNA in their mechanisms and extent of adsorption on clay minerals. Langmuir. 2000;16:1233–1238. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quiquampoix H, Ratcliffe R G. A 31P NMR study of the adsorption of bovine serum albumin on montmorillonite using phosphate and the paramagnetic cation Mn2+: modification of conformation with pH. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1992;148:343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quiquampoix H, Abadie J, Baron M H, Leprince F, Matumoto-Pintro P T, Ratcliffe R G, Staunton S. Mechanisms and consequences of protein adsorption on soil mineral surfaces. In: Horbett T A, Brash J L, editors. Proteins at interfaces. Protein Adsorption on Soil Mineral Surfaces. ACS symposium series 602. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1995. pp. 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Recorbet G, Picard C, Normand P, Simonet P. Kinetics of the persistence of chromosomal DNA from genetically engineered Escherichia coli introduced into soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4289–4294. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4289-4294.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romanowski G, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Adsorption of plasmid DNA to mineral surfaces and protection against DNase I. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1057–1061. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1057-1061.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romanowski G, Lorenz M G, Sayler G, Wackernagel W. Persistence of free plasmid DNA in soil monitored by various methods, including a transformation assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3012–3019. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.9.3012-3019.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romanowski G, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Use of polymerase chain reaction and electroporation of Escherichia coli to monitor the persistence of extracellular plasmid DNA introduced into natural soils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3438–3446. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3438-3446.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar J M, Leonowicz A, Bollag J-M. Immobilization of enzymes on clays and soils. Soil Biol Biochem. 1989;21:223–230. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sikorski J, Graupner S, Lorenz M G, Wackernagel W. Natural genetic transformation of Pseudomonas stutzeri in a non-sterile soil. Microbiology. 1998;144:569–576. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snyder L, Champness W. Molecular genetics of bacteria. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1997. Transformation; pp. 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stotzky G. Influence of soil minerals colloids on metabolic processes, growth, adhesion, and ecology of microbes and viruses. In: Huang P M, Schnitzer M, editors. Interactions of soil minerals with natural organics and microbes. Madison, Wis: Soil Science Society of America; 1986. pp. 305–428. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stotzky G. Gene transfer among bacteria in soil. In: Levy S B, Miller R V, editors. Gene transfer in the environment. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1989. pp. 165–222. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Theng B K G. Developments in soil science. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishing Co.; 1979. Formation and properties of clay-polymer complexes; pp. 157–235. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tien C C, Chao C C, Chao W L. Methods for DNA extraction from various soils: a comparison. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:937–943. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trevors J T. DNA in soil: adsorption, genetic transformation, molecular evolution and genetic microchip. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00393564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vosman B, Kooistra J, Olijve J, Venema G. Cloning in Escherichia coli of the gene specifying the DNA-entry nuclease of Bacillus subtilis. Gene. 1987;52:175–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Widmer F, Seidler R J, Watrud L S. Sensitive detection of transgenic plant marker gene persistence in soil microcosms. Mol Ecol. 1996;5:603–613. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yin X, Stotzky G. Gene transfer among bacteria in natural environments. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1997;45:153–212. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2164(08)70263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou J, Bruns M A, Tiedje J M. DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:316–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.316-322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]