Abstract

A highly convergent total synthesis of (−)-bastimolide A (1), a polyhydroxy antimalarial macrolide, has been achieved via a longest linear sequence of twenty steps from commercially available glycidyl ethers. Type I Anion Relay Chemistry (ARC) coupling tactics enable rapid construction of the molecule’s 1,5-polylol backbone. A late-stage B-alkyl Suzuki-Miyaura union and an Evans-modified Mukaiyama macrolactonization generate the forty-membered Z-α,β-unsaturated macrocyclic lactone.

Keywords: natural products, total synthesis, multicomponent coupling, macrolides, antimalarial agents

Graphical Absract

The introduction of remote stereochemistry via successive Type I Anion Relay Chemistry (ARC) coupling of commercially available enantioenriched epoxides has enabled a 20-step total synthesis of (−)-bastimolide A. The streamlined assembly and manipulation of ARC products demonstrates a versatile approach that could be leveraged toward other polyhydroxylated macrolides

In 2015, Gerwick and coworkers isolated (−)-bastimolide A (1, Figure 1) from a sample of the marine cyanobacterium Okeania hirsuta that was collected from Isla Bastimentos (Bocas del Toro, Panama).1 While the highly degenerate 1H NMR spectrum of 1 impeded immediate assignment of the natural product’s structure, X-ray crystallographic analysis of a nona-p-nitrobenzoylated derivative of (−)-1 unambiguously determined the absolute and relative stereochemistry. Of interest, biological investigations by Gerwick and coworkers revealed that 1 possesses potent antiparasitic properties against four drug resistant strains of P. falciparum malaria (80–270 nM IC50).1

Figure 1.

(−)-Bastimolide A (1) and the related 1,5 polylol-based macrolides (−)-Amantelide A (2), (−)-Nuiapolide (3) (+)-Palstimolide A (4), (−)-Bastimolide B (5) and (−)-Caylobolide B (6).

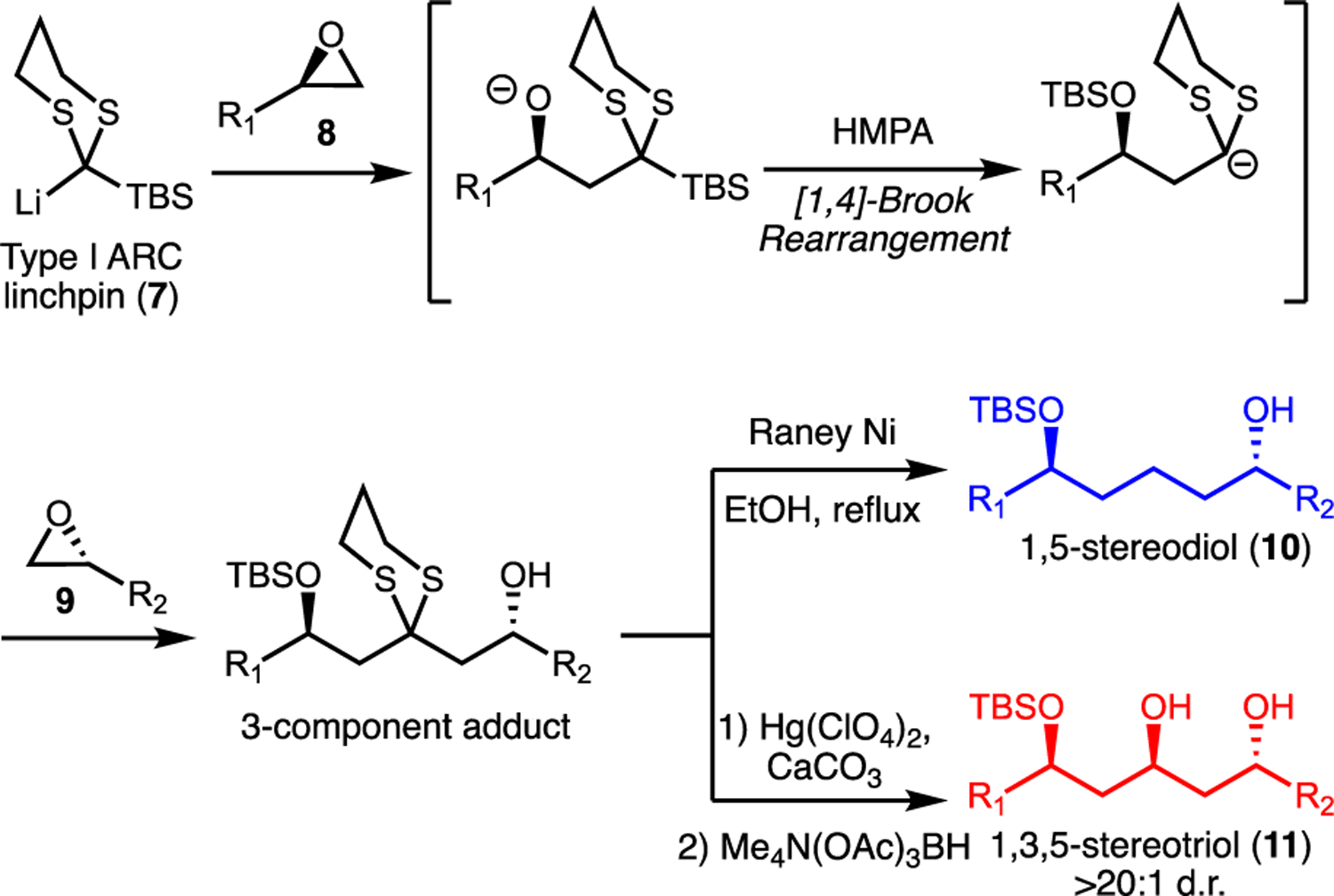

Beyond the promising antimalarial activity of 1, synthetic interest in 1 arose from the intriguing synthetic challenges3 of introducing the 1,5-stereo diols and 1,3,5-stereo triol present in 1, as well as related macrolides 2–6.1–2 To this end, Anion Relay Chemistry (ARC)4, held the potential for rapid and efficient assembly of the 1,5-stereodiol and 1,3,5-stereotriol moieties from readily available epoxides (Scheme 1). For example, lithiated 2-silyl-1,3-dithiane linchpins such as 7, added sequentially to two enantioenriched epoxides 8 and 9 via a solvent-initiated Brook rearrangement, would generate the 3-component adduct. After this three-component union, hydrogenolysis of the 1,3-dithiane to the corresponding methylene with Raney-Ni produces the 1,5-stereodiol 10. Alternatively, hydrolysis of the dithiane to the corresponding ketone, followed by a directed reduction (e.g. Evans-Saksena)6 would lead to the secondary alcohol in the 1,3,5-stereotriol unit 11.

Scheme 1.

Utility of Anion Relay Chemistry (ARC) for constructing 1,5-stereodiols and 1,3,5-stereotriols. HMPA = hexamethylphosphoramide

We thus envisioned that (−)-bastimolide A (1), containing six 1,5-diols, and a single 1,3,5-triol moiety, would comprise an excellent showcase for Type I ARC reactions, given the availability of enantioenriched epoxides and general applicability of type I ARC. To this end, we describe here a successful ARC-based approach to (−)-bastimolide A (1), that, in conjunction with other methods,5 holds the promise for access to similar polyhydroxy macrolide natural products (i.e., 2-6, Figure 1).

Retrosynthetically, we first envisioned late-stage installation of the Z-unsaturated lactone of 1 through B-alkyl Suzuki-Miyaura coupling7 with methyl (Z)-3-iodo-2-butenoate followed by macrocyclization (Scheme 2). The neopentyl alcohol, which would serve as part of the macrolactone, would be protected as a TES ether, while the other hydroxyl groups would be protected as TBS ethers. The planned B-alkyl Suzuki-Miyaura coupling required a monosubstituted alkene. We note that alkenes are typically incompatible with 1,3-dithiane hydrogenolysis (e.g. 9 to 10, Scheme 1). Thus, the alkene-containing Northwestern portion of the molecule was disconnected using a phenylsulfone-iodide coupling between sulfone 13 and iodide 14 (Scheme 2). Northwestern fragment 12 in turn would be generated via union of the Northern Fragment phenylsulfone 15 to Western Fragment iodide 14. Importantly, the 1,3,5-stereotriol and 1,5-stereodiol of 14, as well as the three 1,5-stereodiols of 13, would be well-suited for assembly via Type 1 ARC. Further disconnection of the central 1,5-stereodiol of Southern Fragment 13, reveals the Southwestern and Southeastern Fragments 16 and 17, each again envisioned to arise via our 3-component ARC protocol. Northern Fragment 15 could be synthesized via adaption of similarly reported synthon.8 Adaptation of this chemistry for 15 is where we began the synthesis of (−)-bastimolide A (1).

Scheme 2.

Retrosynthetic analysis of 1.

Construction of 15 (Scheme 3) began with a Bartlett-Smith epoxidation8 on known alcohol (−)-189 to install an epoxide on the homoallylic alkene with high diastereoselectivity (>20:1). To this end, deprotonation of (−)-18 with n-butyl lithium, followed by treatment with di-tert-butyl-dicarbonate appended a Boc group on the secondary alcohol. The Boc-substituted intermediate was then subjected to cyclization to an unstable carbonate (19) upon treatment with iodine monobromide, which was taken up immediately in methanol and treated with K2CO3 to achieve cyclization to the epoxide. Direct treatment of the crude epoxide with TBSCl and imidazole then gave (−)-20 in 62% yield for the four steps. Next, the lithiated anion of methyl phenylsulfone was added to epoxide (−)-20.10 Separation of the excess methyl phenylsulfone from the addition product proved difficult on silica, so the crude addition product was treated directly with TBSCl and imidazole to furnish pure (−)-15 in excellent yield (95%) over the two steps from (−)-20.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Northern Fragment (−)-15.

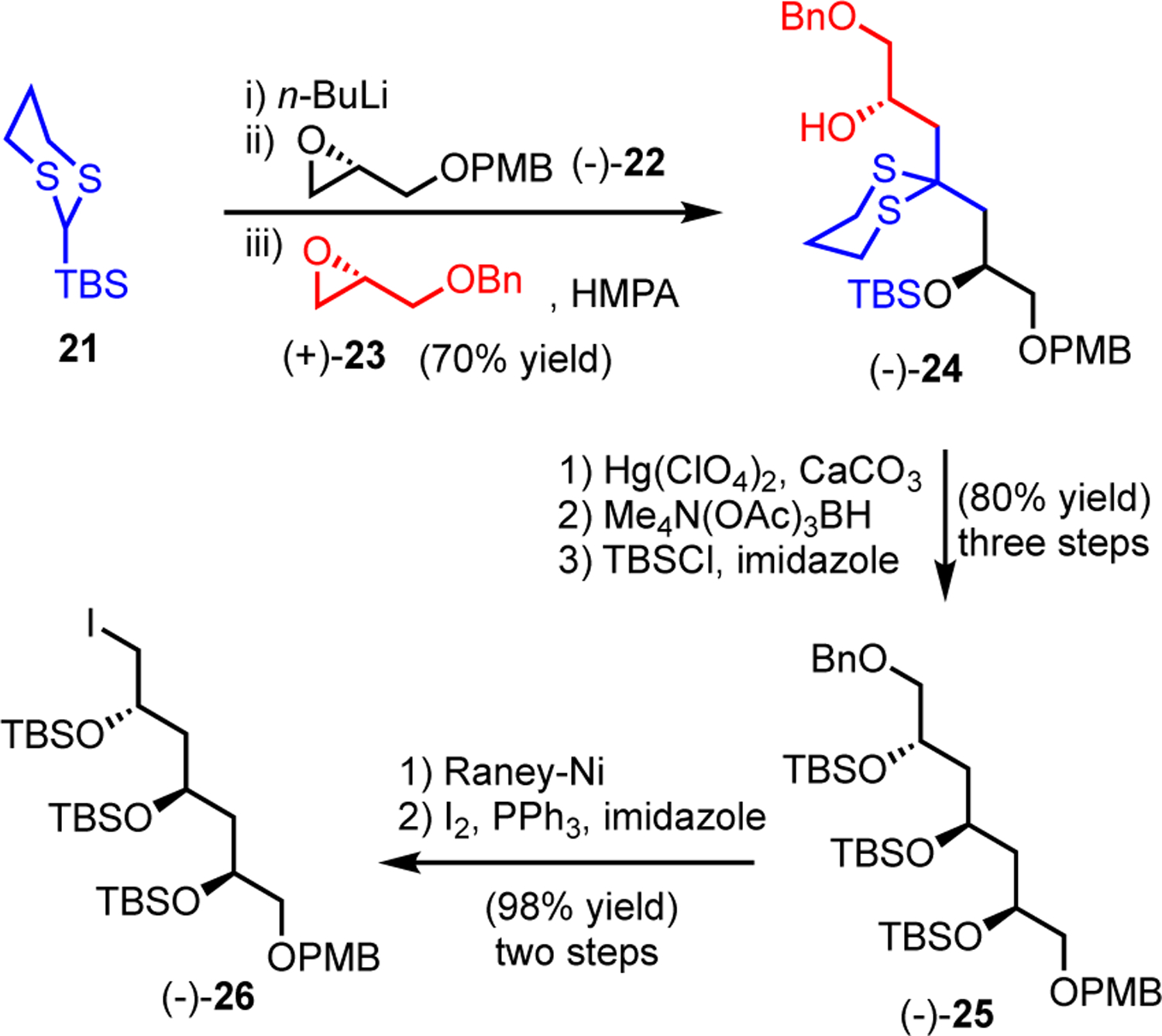

With the Northern Fragment (−)-15 in hand, we turned to the synthesis of the Western Fragment 14 (Scheme 4). The two orthogonally protected glycidyl ethers (−)-22 and (+)-23 were first coupled via the Type I ARC tactic to yield (−)-24. Hydrolysis of dithiane (−)-24 then gave the β-hydroxy ketone in excellent yield (93%). Next, Evans-Saksena stereoselective reduction6 followed by TBS protection of the resulting diol efficiently established the Western 1,3,5-stereotriol of (−)-bastimolide A (1) as the TBS-protected triol (−)-25. The benzyl ether of (−)-25 was then selectively removed with Raney-Ni in the presence of a para-methoxy benzyl (PMB) ether,11 followed by conversion of the resulting primary alcohol to an iodide to achieve the construction of (−)-26 in 99% yield using the Appel conditions.12 At this juncture we recalled that coupling of lithiated dithianes in the past has proven difficult with α-TBS silyloxy substituted iodides using stepwise procedures, due to competing lithium-halogen exchange.13

Scheme 4.

Preparation of iodide (−)-26

Pleasingly however, under our standard Type 1 ARC protocol, no lithium-halogen exchange was observed upon coupling of (−)-26 to (R)-(−)-benzyl glycidyl ether (27) to give adduct (+)-28 in 79% yield (Scheme 5). The dithiane and benzyl ether groups of (+)-28 were then removed simultaneously with Raney-Ni and the primary alcohol converted to an iodide, again employing the Appel conditions12 to give Western Fragment (+)-14, that set the stage for union with Northern Fragment (−)-15.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of Western Fragment (+)-14.

Union of the Western and Northern Fragments (+)-14 and (−)-15 (Scheme 6) was initiated by deprotonation of Northern Fragment phenylsulfone (−)-15 with n-butyl lithium, followed by addition of a solution of the Western Fragment (+)-14 to the prepared anion. The coupling proceeded in excellent yield (82%) to give the North-West coupled product (−)-29 as a mixture of diastereomers at the sulfone-substituted carbon.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the Northwestern Fragment (+)-12. DDQ = 2,3-dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone.

Attempts to remove reductively the phenylsulfone in (−)-29 with Et2NH/Li14 or Li napthalenide15 unfortunately resulted in the simultaneous removal of the PMB ether, followed by transfer of a TBS group from the 1,3,5-stereotriol to the newly formed primary alkoxide (see supporting information Scheme 1). To avoid this undesired reactivity, we utilized the milder conditions of sodium mercury amalgam reduction14 to remove the phenylsulfone from (−)-29. The PMB ether could then be removed with DDQ in the presence of phosphate buffer (pH = 7) to give the primary alcohol, without any observable migration of the TBS groups. Appel conditions12 then afforded the Northwestern Fragment (+)-12 in 45% yield from (−)-15, providing an electrophile that would be united with the Southern Fragment 13 (Scheme 2).

The Southwestern Fragment (16, Scheme 7) was next prepared in four steps beginning with a Type I ARC protocol employing (−)-benzyl glycidyl ether (27) with (+)-benzyl glycidyl ether (23) to furnish the 3-component adduct (+)-30. Treatment of (+)-30 with Raney-Ni then led to reductive removal of the 1,3-dithiane, as well as both benzyl ether protecting groups to give (+)-31. The 1,2-diol of (+)-31 was then selectively protected as a benzylidene acetal and the remaining primary alcohol converted to the iodide (−)-16 under Appel conditions.12 The overall sequence to arrive at the Southwestern Fragment (−)-16 was 54 % over four steps (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of Southwestern Fragment (−)-16.

Next, synthesis of the Southeastern Fragment 17 (Scheme 8) began with a Type I ARC union of commercially available epoxide (−)-33 with (+)-benzyl glycidyl ether (22) using the lithiated TES-dithiane lynchpin 32. Here, we were able to transfer a triethylsilyl (TES) protecting group to the neopentyl alcohol of (−)-34. In this context, a TES ether could be considered orthogonal to TBS ethers because of the vastly different rates of hydrolysis of TBS and TES protecting groups. The greater lability of TES ethers however was immediately observed when (−)-34 was treated with Raney-Ni under the previous conditions. Here a loss of the TES group was observed, attributed to residual sodium hydroxide that could not be removed from the Raney-Ni employing the standard reagent washing process. Pleasingly, addition of pH = 7 phosphate buffer to the reaction mixture prevented the loss of the TES group, now to provide diol (−)-35 in good yield. The 1,2-diol of (−)-35 was then converted to an epoxide over two steps. Selective tosylation of the primary alcohol, followed by treatment with n-butyl lithium gave (−)-17 in 40% yield over four steps from (−)-33.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of Southeastern Fragment (−)-17.

The Southeastern Fragment (−)-17 and the Southwestern Fragment (−)-16 (Scheme 9) were next united employing the Type 1 ARC protocol to give (−)-36 in 64% yield. Exposure of (−)-36 to Raney-Ni desulfurization conditions in the presence of pH = 7 phosphate buffer then pleasingly led both to benzylidene acetal hydrogenolysis and dithiane removal without any loss of the TES ether to produce (+)-37. Employing the previous method [(−)-35 to (−)-17] to (+)-37 led to (−)-38 in 80% yield. Addition of methyl phenylsulfone to epoxide (−)-38 then proceeded in excellent yield (86%), which upon subsequent hydroxyl protection as the TBS ether completed the Southern Fragment (−)-13. The overall yield for the five-step sequence from (−)-17 to (−)-13 was 41%.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of Southern Fragment (−)-13.

Southern Fragment (+)-12 was next united with Northwestern Fragment (−)-13 via alkylation of the sulfonyl carbanion of (+)-12 to complete the bastimolide carbon backbone (−)-39 (Scheme 10). The low solubility of (−)-39 in methanol required the use of a THF/methanol solvent mixture to produce reduction product (+)-40 with Na/Hg amalgam. Treatment of (+)-40 with 9-BBN then yielded an organoborane intermediate that underwent Suzuki-Miyaura coupling7 with known iodide 4117 in the presence of Pd(PPh3)4 and tripotassium phosphate employing dioxane at reflux18 to give (−)-42 in 70% yield.

Scheme 10.

End game synthesis of (−)-Bastimolide A (1).

With the full carbon skeleton of bastimolide A constructed, our focus turned to macrocyclization to the 40-membered lactone. To this end, (−)-42 required conversion of the TES ether to the alcohol and the methyl ester to an acid. Attempts to arrive directly at macrocyclization precursor (−)-43 from (−)-42 via treatment of (−)-42 with sodium or lithium hydroxide produced a complex mixture of products. Thus, we opted for a stepwise approach, where in the TES group of (−)-42 was first removed under acidic conditions. A screen of different concentrations of pyridinium p-toluenesulfonate (PPTS) and camphorsulfonic acid (CSA) in various solvent mixtures and temperatures revealed that the highest level of selectivity could be achieved using PPTS in chloroform/methanol. Up to an 87% yield, based on recovered starting material, could be achieved by quenching the hydrolysis at 50% conversion. Saponification of the methyl ester was then achieved with trimethyltin hydroxide, under a modification of the procedure reported by Nicolaou and coworkers19 to give the seco acid (−)-43, in preparation for the key macrolactonization.

The initial attempts to achieve macrocyclization of (−)-43 under standard Yamaguchi20 and Boden-Keck21 conditions only gave complex mixtures of products. In contrast, macrocyclization of (−)-43 under the Yonemitsu modification22 of the Yamaguchi conditions, where all reagents are introduced at room temperature at the reaction’s outset, gave the desired macrocycle in high yield (77%), albeit with isomerization of the α,β-unsaturated lactone from Z to E (1:1). Careful screening of additional macrocyclization conditions (see supporting information Table 2 and 3) revealed that the minimum amount of isomerization occurred under the Evans-modified Mukaiyama protocol23 where 2-bromo-1-ethylpyridinium tetrafluoroborate 44 was employed in the presence of sodium bicarbonate and dichloromethane. Under these conditions, up to a 10:1 ratio of Z/E isomers could be obtained. Importantly, the isomers could be separated on silica to give a 56% yield of the desired Z isomer.

Subsequent removal of all nine TBS ethers was not immediately successful. In particular, treatment of the macrocycle with hydrochloric acid in methanol gave rapid ring opening of the lactone to the corresponding methyl ester. Intractable mixtures of byproducts also formed upon treatment with tetrabutylammonium fluoride, but importantly a clean conversion to bastimolide (−)-1 was observed upon treatment with concentrated aqueous hydrofluoric acid. Synthetic bastimolide (−)-1, produced from this deprotection protocol displayed identical HRMS, 1H, 13C, and FTIR to the natural material reported by Gerwick and coworkers. The chiroptic properties of the synthetic material were also in agreement with the natural material {[α]23D −10.5 (c 0.083, methanol); lit.1 [α]23D −11.7 (c 1.75, methanol)}.

In summary, the first total synthesis of the 40-membered macrolide (−)-bastimolide A (1) has been achieved over a longest linear sequence of 20 steps from commercially available glycidyl ethers. The use of five Type 1 ARC protocols to establish the 1,5-stereodiol and 1,3,5-stereotriol units enabled this relatively short sequence of steps. Studies to access related polyhydroxylated macrolide natural products with ARC-based strategies, as well as the development of bastimolide A (1) analogues for biological evaluations, continue in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

(Financial support was provided by the NIH through CA-19033 Grant. We thank Dr. Jun Gu at the University of Pennsylvania for help in obtaining the NMR spectral data. We also thank Dr. Charles W. Ross III, Director: Automated Synthesis and laboratory research associates, Sung-Eun Suh and Joo Myung Jun for providing chromatographic and mass spectral method development, analyses, and data interpretation. We thank Dr. William Gerwick and Dr. Changlun Shao for helpful discussions and for providing additional NMR data that assisted in the characterization of synthetic (−)-bastimolide A (1).

References

- [1].a) Shao C, Linington RG, Balunas MJ, Centeno A, Boudreau P, Zhang C, Engene N, Spadafora C, Mutka TS, Kyle DE, Gerwick L, Wang C, Gerwick WH, J. Org. Chem 2015, 80, 7849–7855; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Salvador LA, Sneed J, Paul VJ, Luesch H, J. Nat. Prod 2015, 78, 1957–1962; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Salvador LA, Paul VJ, Luesch H, J. Nat. Prod 2010, 73, 1606–1609; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Mori S, Williams H, Cagle D, Karanovich K, Horgen D, Smith R III, Watanabe CMH, Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 6274–6290; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Keller L, Siqueira JL, Souza JM, Eribez K, LaMonte GM, Smith JE, Gerwick WH, Molecules 2020, 25, 1604–1613; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Shao C, Mou X, Cao F, Spadafora C, Glukhov E, Gerwick L, Wang C, Gerwick WH, J. Nat. Prod 2018, 81, 211–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].The original structure of caylobolide B reported in ref.1c was incorrect. The geometry of the C2−C3 double bond was revised later by the same group:; Salvador LA, Paul VJ, Luesch H, J. Nat. Prod 2016, 79, 452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Friedrich RM, Friestad GK, Nat. Prod. Rep 2020, 37, 1229–1261.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Quintard A, Sperandio C, Rodriguez J, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 5274–5277; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kumara NS, Ramulua BJ, Ghosh S, Syn Open 2021, 5, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Deng Y, Smith AB III, Acc. Chem. Res 2020, 53, 988–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Yeung K, Mykura RC, Aggarwal VK, Nat. Synth 2022, 1, 117–126; [Google Scholar]; b) for a synthesis of bastimolide b see: Fiorito D, Keskin S, Bateman JM, George M, Noble A, Aggarwal VK J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 10.1021/jacs.2c03192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Evans DA, Chapman KT, Carreira EM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 3560–3578; [Google Scholar]; b) Saksena AK, Mangiaracina P, Tetrahedron Lett. 1983, 24, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Miyaura N, Ishiyama T, Ishikawa M, Suzuki A, Tetrahedron Lett. 1986, 27, 6369–6372; [Google Scholar]; b) Chemler SR, Trauner D, Danishefsky SJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2001, 40, 4544–4568; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2001, 113, 4676–4568. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bartlett PA, Meadows JD, Brown EG, Morimoto A, Jernstedt KK, J. Org. Chem 1982, 47, 4013–4018; [Google Scholar]; b) Duan JJ-W, Sprengeler PA, Smith AB III, Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 6439–6442. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kavala M, Mathia F, Kožíšek J, Szolcsányi P, J. Nat. Prod 2011, 74, 803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Smith AB III, Lin Q, Doughty VA, Zhuang L, McBriar MD, Kerns JK, Boldi AM, Murase N, Moser WH, Brook CS, Bennett CS, Nakayama K, Sobukawa M, Lee Trout RE, Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 6470–6488; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Paterson I, Savi CD, Tudge M, Org. Lett 2001, 3, 3149–3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ai Y, Kozytska MV, Zou Y, Khartulyari AS, Maio WA, Smith AB III, J. Org. Chem 2018, 83, 6110–6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Appel R, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1975, 14, 801–811; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 1975, 87, 863–874. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Smith AB III, Lee D, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 10957–10962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kuwahara S, Liang T, Leal WS, Ishikawa J, Kodama O, Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem 2000, 64, 2723–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Oishi T, Ando K, Inomiya K, Sato H, Lida M, Chida N, Org. Lett 2002, 4, 151–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Smith AB III, Barbosa J, Wong W, Wood JL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 10777–10778; [Google Scholar]; b) Norazah B, Krishnan D, Liu H, Morris G, Sirat HM, Thomas EJ, Curran DP, J. Org. Chem 2014, 79, 7477–7490; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Maharvi GM, Edwards AO, Fauq AH, Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 6426–6428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Akpinar EG, Kus M, Ucuncu M, Karakus E, Artok L, Org. Lett 2011, 13, 748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Miyaura N, Ishiyama T, Sasaki H, Ishikawa M, Satoh M, Suzuki A, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 314–321; [Google Scholar]; b) Taillier C, Gille B, Bellosta V, Cossy J, J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 2097–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nicolaou KC, Estrada AA, Zak M, Lee SH, Safina BS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 44, 1378–1382; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem 2005, 117, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Inanaga J, Hirata K, Saeki H, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1979, 52, 1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Boden EP, Keck GE, J. Org. Chem 1985, 50, 2394–2395. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Hikota M, Sakurai Y, Horita K, Yonemitsu O, Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 6367–6370; [Google Scholar]; b) Okuno Y, Isomura S, Nishibayashi A, Hosoi A, Fukuyama K, Masashi O, Kazuyoshi T, Synth. Commun 2014. 44, 2854–2860. [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Mukaiyama T, Usui M, Saigo K, Chem. Lett 1976, 5, 49–50; [Google Scholar]; b) Evans DA, Starr JT, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 13531–13540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.