Abstract

The presence and severity of childhood and adult victimization increase the likelihood of substance use disorder (SUD), crimes, antisocial behaviors, arrests, convictions, and medical and psychiatric disorders among women more than men. These problems are compounded by the impact of social determinants of health (SDH) challenges, which include predisposition to the understudied, dramatic increase in opioid dependence among women. This study examined victimization, related SDH challenges, gender-based criminogenic risk factors for female participants, and public health opportunities to address these problems. We recruited women from the first national Opioid Intervention Court, a fast-track SUD treatment response to rapidly increasing overdose deaths. We present a consensual qualitative research analysis of 24 women Opioid Intervention Court participants (among 31 interviewed) who reported childhood, adolescent, and/or adult victimization experiences in the context of substance use and recovery, mental health symptoms, heath behaviors, and justice-involved trajectories. We iteratively established codes and overarching themes. Six primary themes emerged: child or adolescent abuse as triggers for drug use; impact of combined child or adolescent abuse with loss or witnessing abuse; adult abduction or assault; trajectory from lifetime abuse, substance use, and criminal and antisocial behaviors to sobriety; role of friends and family support in recovery; and role of treatment and opioid court in recovery, which we related to SDH, gender-based criminogenic factors, and public health. These experiences put participants at risk of further physical and mental health disorders, yet indicate potential strategies. Findings support future studies examining strategies where courts and health systems could collaboratively address SDH with women Opioid Intervention Court participants.

Keywords: Criminology, intergenerational transmission of trauma, women offenders, alcohol and drugs with history of abuse

Introduction

In the United States (U.S.), between 2002 and 2015, there was an increase in the total number of opioid and heroin-related deaths by 2.8- and 6.2-fold, respectively (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2020). Despite women comprising only 20% of those with opioid use disorders (OUDs) in the 1960s, recent trends indicate nearly equal numbers among women and men (Cicero et al., 2014). More concerning, death rates from opioids heroin and synthetic opioids among women have increased nearly 915% and 1643% since 1999, respectively (VanHouten et al., 2019). The problems that women face concerning opioid use, related mortality rates, and access to evidence-based treatments are unclear and require further study.

To combat the exponentially increasing overdose deaths in the U.S., communities began to create Opioid Intervention Courts (OC) to help decrease mortality rates. Our multidisciplinary research team recruited women from the nation’s very first OC to better understand their experiences, and to identify potential strengths and intervention opportunities regarding this rapidly evolving fast-track approach. Our team began this exploration from the clients’ lived experiences, which is uniquely suited to qualitative interview and analytic strategies among women with substance use and criminal justice histories (Morse et al., 2014; Sormanti et al., 2001).

Trauma, Substance Use, Women, and Criminal Justice Involvement

There is a known association between childhood physical or sexual abuse among women and men with substance use disorders (SUDs), with a greater impact on women (Hughes et al., 2010). Women report a higher prevalence of childhood abuse and intimate partner violence (IPV) in turn, associated with more SUD consequences (Rivera et al., 2015). There are also known mental and physical health consequences of childhood abuse among women, including greater risk for later victimization (Arias, 2004). Research suggests a cumulative effect of increased SUD risk after multiple early victimization experiences, particularly among sexual minorities (Hughes et al., 2010). However, SUD among those with early abuse, neglect, and criminal justice involvement was mediated by stressful life events, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and adult attachment, suggesting early prevention and response could be beneficial (Dishon-Brown et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2018; White & Widom, 2008; Winham et al., 2015).

Relatedly, there is evidence that both the presence and severity of childhood victimization increased the likelihood of crimes, antisocial behaviors, arrests, convictions, and psychiatric disorders, more so among women than men (Altintas & Bilici, 2018; Friestad et al., 2014). The combination of childhood victimization with parent and sibling mental health, SUD, and crime problems leaves women especially vulnerable to develop later severe mental illness, depression, SUD, adult victimization, externalized anger, and criminal behaviors (Bowen et al., 2018; Hayes, 2015; Jones et al., 2018). Adult victimization also predicted worse legal outcomes, including rearrest, for women recently released from incarceration (Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2009).

Conversely, post-traumatic protective factors can include the empowering experiences of helping and caring for others, yet must be balanced with the need for women to engage in self-care (Hoskins & Morash, 2020). While the intersection between trauma, SUD, and justice involvement have been described in longitudinal research studies among women, a social determinants of health (SDH) framework may assist with designing and implementing preventive interventions that could lessen criminogenic and health risks among women with trauma histories (Herrenkohl et al., 2017; Marmot et al. 1978, 1991).

SDH

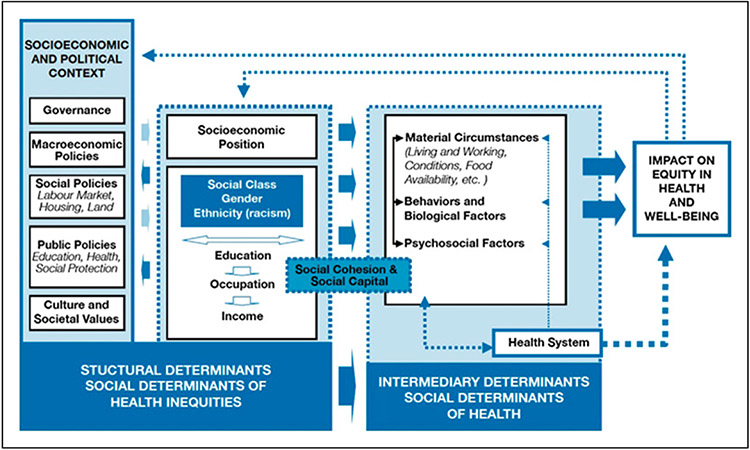

SDH are social, physical, and economic environments or ecosystems which create social hierarchies and impact health equity and well-being outcomes, including mortality rates (Figure 1; Marmot et al., 1978, 1991). Structural determinants include laws, economic and social policies, cultural and societal values, and socioeconomic positions, while intermediary determinants include material circumstances, behaviors, biological elements, and psychosocial factors. Because women with OUD and justice involvement often face profound and intersecting SDH challenges, our team identified SDH as the overarching theoretical model for our analysis. Among those with SUD, substance use and overdose predictors have included: overlapping racial and/or female gender discrimination, trauma, HIV and/or drug-related stigma, economic hardship, low social support, lack of education, social networks, difficulties accessing care, food insecurity, lack of harm reduction approaches, poor social services access, drug criminalization policies, and incarceration (Friedman et al., 2016; Fuller et al., 2005; Galea & Vlahov, 2002; Park et al., 2020; Shokoohi et al., 2019). We sought to contextualize these known factors among women actively engaged in a problem-solving court approach to inform areas where this approach could be improved. For justice-involved women, it is key to better understand upstream and downstream impacts of trauma as an SDH, which may critically impact their criminogenic risks, ability to function in the community, and health outcomes.

Figure 1.

Social determinants of health.

Gender- and Trauma-Responsive Approaches to Criminogenic Risks

The terms “gendered pathway” and “gender-responsive” needs have been used to describe justice-involved women with trauma histories (Wright et al., 2007). The Missouri Women’s Risk Assessment and the “Trailer” correlated with and were more predictive of criminogenic behaviors than gender-neutral scales alone (Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2009; Wright et al., 2007). These measures incorporated women’s experiences with trauma, SUD, dysfunctional relationships, and mental illness, as well as needs regarding parenting, childcare, and self-concept. We used an SDH framework to examine the interplay between early life and adult physical and sexual abuse, intergenerational substance use, family dynamics, and gendered criminogenic needs in an attempt to strengthen trauma-informed programs for justice-involved women. Although decades of research have documented high rates of trauma among women and girls involved in the justice system and the association of those problems with substance use, incarceration, and myriad health and social sequelae, no clear consensus on an effective strategy has emerged (Herrenkohl et al., 2017). While some trauma-responsive approaches have demonstrated benefit, attempts to synergistically combine them with treatment court have not demonstrated distinctly positive outcomes. Innovations and rapid changes in justice system approaches to the opioid epidemic may present a path to introduce and implement needed modifications.

Problem-Solving Courts

Problem-solving courts use legal leverage to offer treatment as an alternative to incarceration, with participants required to demonstrate sobriety and increased housing and employment stability for graduation. Recent evaluations of these courts reveal few randomized controlled trials, a lack of standardization, and varying success rates, with gender- and trauma-focused programs for women unable to demonstrate improved outcomes (National Institute of Justice, 2020). Some problem-solving court programs with proven success utilized family-based, motivational interviewing, technology, and trauma-focused therapy approaches (National Institute of Justice, 2020). The opioid crisis has prompted innovative strategies to prevent overdoses. Building upon successes and lessons learned from the use of drug treatment courts (DTC) and the urgent need to address rapidly rising opioid overdose deaths, various sites across the U.S. have recently implemented OCs (Watson, 2018). Given the differences in needs and outcomes between female and male DTC participants, and what little is known of OC outcomes, it is important to develop sound gender-responsive, trauma-informed, and trauma-specific strategies to inform legal practices and public health approaches (Goldberg et al., 2019; Tripodi & Pettus-Davis, 2013).

This study examined early and adult victimization, substance use, mental and physical health, and criminogenic factors among a rapidly increasing but little understood population of opioid-dependent women who participated in OC. In the present study, we use the SDH framework to inform justice and public health approaches to explore the connected problems.

Methods

Study Design

The study venue OC is the first of its kind in the nation, opening in May 2017. A research assistant used purposive sampling to recruit study participants in the lobby of the courthouse, outside the OC from January to July 2019. Because the research assistant attended OC and had a copy of the docket, she only approached those particular women. There were approximately 110 people in the OC at any given time; 40% of whom were women, 20% of whom were Black, and 10% of whom were Hispanic or Latina (Opioid Intervention Court staff, personal communication, July 17, 2018). Due to the heightened risk of coercion for court-involved individuals, we informed women that both their participation and content of their research participation were confidential (including to OC staff) and had no bearing on their legal status.

Individuals were eligible if they were aged 18 years or older, able to speak English, and identified as female. If a participant was unable to read, materials could be read to her. Eligible, consenting women self-administered two questionnaires and engaged in a subsequent in-person, semi-structured qualitative interview. One university Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and the second university approved the protocol as a multi-site study. The team approached 42 eligible women of whom none declined and all agreed to participate. Between January–August 2019, we conducted 31 interviews until we reached content saturation with no new emergent themes. 11 of the women who agreed to participate failed to complete an interview, most commonly due to incarceration (n = 3), entrance into a long-term rehabilitation program (n = 2), or relocation to another area (n = 2).

Interview Design

The multidisciplinary team met to finalize semi-structured interview questions with exploratory follow-up probes (Hill et al., 2005). Interview topics included trauma, substance use and recovery, mental health symptoms, health behaviors, and justice involvement trajectories, according to parent study aims and investigators’ knowledge of existing research. Planned exploratory strategies included inviting participants to “tell their story” of experiences in salient topics. Team member disciplines included medicine, sociology, law, criminal justice, and public health. Senior team members have extensive research expertise, including childhood and adult trauma, mental and physical health, substance use, and working with criminal justice professionals, participants, and systems. The interviewer was a public health graduate student experienced in motivational interviewing and in addressing SUD.

Interview Processes

The first three interviews took place with real-time observation via Zoom. The team provided feedback until interviews were conducted according to team standards. The interviewer conducted the remaining sessions alone, with senior team members periodically listening to random portions of the interviews for fidelity and to assess saturation. Given the sensitive nature of the information gathered, the script included the interviewer using responses such as, “I’m sorry that happened to you;” “that must have been difficult for you;” and “congratulations” for reported sobriety. These responses were not meant to be “deeply relational” or to “co-construct meaning;” rather, they were meant to build trust to help the participants accurately describe their experiences and thoughts (Hill et al., 2005). Per our design, after the first three interviews, we refined the interview processes and adapted interview questions to ensure that our research aims were being met, using consistent interview protocols (Hill et al., 2005).

The semi-structured interviews lasted on average 45 minutes and were performed at a university research office or a family justice center within walking distance to the courthouse. Participants were reimbursed a total of $60 in cash ($20 for the questionnaires and $40 for the interview) and four roundtrip public transit passes. We digitally audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim into Microsoft Word documents, and then de-identified all interviews.

Data Analysis

The multidisciplinary team (including trained research assistants) analyzed the data, conducting a Consensual Qualitative Research analysis (Hill et al., 2005), an integrative approach incorporating elements from phenomenological, grounded theory, and comprehensive process analyses. Research team members understood meaning through the words of the text, staying close to the data and avoiding over-interpretation. Our multidisciplinary team was involved throughout the process to foster multiple perspectives. However, the researchers used a consensus process to arrive at a common understanding regarding the meaning of the data.

The team jointly reviewed the first three transcriptions to create a preliminary list of primary and secondary codes to group the data. The team met repeatedly to share insights, reflected when there were disagreements, and reached consensus. We continued to meet in smaller teams after the next 11 interviews were transcribed to review the codebook and iteratively revise the preliminary list of codes to develop core ideas. A final codebook was co-created; the first eight transcripts were then recoded with the final codebook by at least two team members per transcript. For this paper, the team performed a final cross-analysis to construct common themes across the participants who had experienced child, adolescent, and/or adult trauma. We focused specifically on codes and overarching themes relating to childhood, adolescent, and adult abuse, substance use, mental health, physical health, treatment, and criminal justice involvement, using an SDH framework (Solar & Irwin, 2010). We used the World Health Organization’s definition for adolescents as between the ages of 10–19. We included transcripts (n = 24, 77% of the sample) in which participants responded to questions regarding abuse by describing child and/or adolescent victimization and/or abuse, which included witnessing abuse (Wathen & MacMillan, 2013) and adult abuse. Specific quotes from participants’ transcripts could be assigned one or more codes based on content relating to their experiences and to our overarching research questions. The team asked two formerly incarcerated women to review the data to have respondent verification of its trustworthiness (Barbour, 2001).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics are provided in Table 1, and it compares the 31 consenting participants who completed interviews to the 11 who consented but did not complete. Of those who completed interviews, the average age was 30.9 years (range = 21–53), all identified as White, 9.7% identified as Hispanic/Latina, and 77.4% identified as heterosexual. Contextualizing our sample, 2019 county data where the OC is located show 94.2% Non-Hispanic White, 14% Black, 5.8% Hispanic or Latina, and 51.6% female individuals (United States Census Bureau, n.d.). In contrast, misdemeanor arrests were 57% White, 30% Black, 10% Hispanic or Latino, and 28.5% female individuals. Lastly, OC data indicate 52% White individuals overall, 40% women, 20% Black women, 7% Hispanic or Latina women (New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, 2020).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Consenting Participants (N = 42).

| Completed Interview (n = 31) |

Did Not Complete Interview (n = 11) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) |

| Age (Mean [SD]) | 30.9 (6.82) | 28.5 (3.33) |

| Race | ||

| White | 31 (96.77) | 9 (81.81) |

| Black/African American | — | 1 (9.09) |

| Other | 1 (3.23) | 1 (9.09) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latina | 3 (9.68) | 1 (9.09) |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Straight/Heterosexual | 24 (77.42) | 9 (81.81) |

| Bisexual | 6 (19.35) | 2 (18.18) |

| Gay | 1 (3.23) | — |

| Educational Attainment | ||

| Less than high school | 8 (25.81) | 4 (36.36) |

| GED/High school | 13 (41.94) | 6 (54.55) |

| Some college or college degree | 10 (32.26) | 1 (9.09) |

| Partner Statusa | ||

| Single | 21 (67.74) | 8 (72.73) |

| Live with partner(s) | 5 (16.13) | — |

| Don’t live with partner(s) | 2 (6.45) | — |

| Separated | 2 (6.45) | 1 (9.09) |

| Non–co-habiting | — | 1 (9.09) |

| Don’t know | 1 (3.23) | — |

| Employment Statusa | ||

| Unemployed | 22 (70.97) | 2 (18.18) |

| Disabled | 4 (12.90) | 1 (9.09) |

| Employed | 4 (12.90) | 4 (36.36) |

| Not applicable | 1 (3.23) | 3 (27.27) |

| Childrena | ||

| Yes | 21 (67.74) | 8 (72.73) |

| No | 10 (32.26) | 2 (18.18) |

| Average number of children (M[SD]) | 2.29 (1.22) | 1.88 (0.83) |

| Housing Situationa | ||

| Own or rent a home | 7 (22.58) | 2 (18.18) |

| Live with others | 23 (74.19) | 6 (54.55) |

| Live in a shelter | 2 (6.45) | 1 (9.09) |

| Homeless | 1 (3.23) | 2 (18.18) |

Totals do not sum to 100% due to participants refusing to answer or reporting multiple living situations.

We tabulated frequencies of types of victimization among the 24 of the 31 women who shared violence experiences (Table 2). Among the overall sample of 31 Court participants, 24 women (77%) described child, adolescent, or adult trauma, 22 (71%) described childhood and/or adolescent victimization, and 20 (65%) described adult victimization histories. Seven of the 22 described experiences of neglect. Seven of the 22 described sexual abuse and six described emotional abuse. In addition, three of the 22 described experiences of physical abuse and six described witnessing physical abuse. Nine of the 22 women reported intergenerational alcohol and drug use with direct adult involvement. Seven of the 22 experienced the deaths of close family members due to drug overdoses during their early developmental years. Among the 20 women describing adult victimization, five reported an abduction component and 15 reported IPV experiences.

Table 2.

Count of Victimization Events.

| Primary Code | Secondary Code | Number of Excerpts |

Participants (n = 24)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child/adolescent victimization/abuse | Sexual | 11 | 7 |

| Physical | 7 | 3 | |

| Emotional | 10 | 6 | |

| Neglect | 15 | 7 | |

| Adult family member providing drugs/co-using drugs with child | 10 | 9 | |

| Child/adolescent witness abuse of others | Physical | 7 | 6 |

| Emotional/neglect | 5 | 5 | |

| Adult victimization/abuse | Abduction | 5 | 5 |

| Intimate partner violence | 23 | 15 |

Participants may report more than one instance of each secondary code; therefore, totals do not sum to 24.

Six primary themes emerged: child or adolescent abuse as triggers for drug use; impact of combined child or adolescent abuse with loss or witnessing abuse; adult abduction and assault; trajectory from lifetime abuse, substance use, criminal and antisocial behaviors to sobriety; role of friends and family support in recovery; and role of treatment and opioid court in recovery, which are described in relation to SDH, gender-based criminogenic factors, and the public health problem of SUD.

Childhood or Adolescent Abuse as Triggers for Drug Use

Most women described having been sexually, physically, and/or emotionally abused as children or adolescents and the role it played as an SDH in their mental health and subsequent substance use, with this being the most frequent theme.

In many cases, substance use served as a coping mechanism for enduring sexual abuse as a child. As one described:

I was molested when I was a kid…from six to seven-ish…and that trauma played…a role…in my mental health and in my addiction because…my whole life…I felt like I was different, like something was wrong with me. For a long time, I suppressed the memories of that happening to me. And then as I got older, I started having more and more flashbacks and remembering more and more and…anything to just numb the pain or anything to make me feel like somebody else or…the physical buzz that I would focus on because it felt good or…getting so annihilated that I couldn’t possibly be feeling any pain from it because there was no pain when you’re that high. (Participant 5).

While emotional abuse often co-occurred with physical or sexual abuse, women commonly attributed their subsequent substance use specifically to the SDH of various types of emotional abuse they experienced early in life and described their sequelae. In the instance below, the woman described the neglect from her mother’s mental illness and father’s time in prison as contributing factors to her substance use and criminal behaviors:

When she tried to kill herself, and it was a horrific scene. It was really bad…and I felt guilty…finding her overdosed on the floor from pills…She tried to kill herself five times and finally she just stopped trying to kill herself…My mom was my best friend and then with the mental health stuff, she just forgot she had kids, gave us all up…My father being in prison basically my whole life…could have been a big trigger of my drug use, too, and he was also an addict and used…I feel like that’s why I don’t like cops so much is because they were always at our house, and that’s why I have the charges that I have, I feel like when I see cops, I just go back into a different state of mind. (Participant 31).

The participant below describes the lasting effects of the SDH of childhood neglect, compounded by the later abuse by her father of using drugs together, and her determination to prevent the pattern repeating itself on her own child, possibly a source of post-trauma healing:

Me and my father don’t speak right now. He was never around when I was growing up and then I sought him out when I got older and then it was just using drugs together…. But I love my dad. I’ll never give up on him completely, but I’m just taking some time from [him]….He hurts me a lot and I refuse to let him hurt my daughter, emotionally speaking. My father never beat me, but he was never around. (Participant 5).

For the participant below, the SDH of a parent with SUD combined with the emotional abuse of neglect contributed to her disengagement from helpful SDHs such as school:

When I was younger, I raised myself. I had no structure. I had no one telling me what to do. My mom said “oh, if you’re going to drink and do drugs, do it at the house so I can at least monitor you.” Come to find out, it was pretty much just because she wanted to do it with me or have drugs too but I had no one telling me what to do. I didn’t have to go to school if I didn’t want to. My mom was like “do what you want.” She wasn’t really a parent so I had no structure. None. (Participant 6).

It was common that women experienced combined abuse and several women described those specific impacts from an early age. Several participants experienced the emotional abuse of growing up in a home with parental substance use, neglect, and criminal behavior, which was compounded by their own sexual victimization, thereby influencing their trajectory to crime. As one participant explains:

My parents split up, and my dad was an alcoholic. After I got raped, I moved to my dad’s house…and it was always constant party there…there was always alcohol…I was only 13 years old when I started…drinking every day. And if I wasn’t drinking I was doing something else…there was never a sober me…When I was around my dad I would drink, but when I was around my mom, she didn’t drink, she did pills….Whoever I was around I would do [whatever they did]. (Participant 6).

For the woman below, intergenerational substance use and crime began with the emotional abuse of being given drugs by her mother, observing her mother and her mother’s friends use and sell drugs, and eventually, engaging in criminal behavior as a drug dealer for her mother. This became an SDH for her as she was coerced into drug use and experienced parental neglect during her adolescent years:

I did not consider pills drugs because my mom’s doctor gave them to her and because my mom at that age, 12, 13, 14 would give them to me herself …I’d have a headache, so she’d give me a Percocet and I have an anxiety disorder so I’d be really anxious and she would give me a Valium….Besides my mom giving them to me and watching my mom selling them to her friends, I watched them crushing them up and sniffing them, and eventually I got curious….Around the beginning of sophomore year, one of my friends found out about my mom having pills and so they would ask me for them….I went from being someone who was completely against drugs and then trying weed and within two months…I was taking Ecstasy, taking mushrooms…and giving them to my friends…My mom found out that my friends were taking the pills and…she took advantage of the situation in order to have me sell them to my friends….I was 16 the first time I sniffed cocaine….I don’t know if [my mom] didn’t care or she didn’t want to be bothered….No one told me to be in the house at 11 on school nights….so I was just allowed to run wild and do whatever it was that I wanted. (Participant 35).

Finally, this woman experienced physical abuse by her father, who helped her inject heroin at a very early age, combined with the emotional abuse of neglect, which exposed her to significant harm, limited her sense of safety, and was an SDH for her substance use and crime trajectory into adulthood:

I was 10 when I started doing heroin. I was with my dad the first time…Parents are supposed to be there to protect and to nurture and to love and neither one of my parents did that for me, so it’s hard…that was the first time I ever touched heroin and I injected it. I never sniffed it. I just went right to shooting it with my dad. At one point…I was [using] every day. That’s all I did (Participant 24).

Impact of Combined Childhood or Adolescent Abuse With Loss or Witnessing Abuse

Several women’s complex trajectories to the health risks of substance use and criminal behavior included the SDH of trauma from the death or mental illness of a loved one, such as a parent or sibling. This type of trauma was preceded by the SDH of years of neglect, shared or witnessed substance use, and/or violence from family and family friends:

I was 13 when my dad died from cirrhosis of the liver and right after my dad died [my mom] just got suicidal….I would walk in the house and her head would be in the stove trying to kill herself… We [also] got high together…13 years old and her leaving me three or four days at a time with no food, no money or nothing to survive, and from watching her…steal, I learned how to do it. I would steal school supplies and I would go to school and sell school supplies so I would have money to eat and it was just crazy…But I was afraid of leaving her and then she would kill herself. I became her enabler and I was paying for her bag every morning. I would babysit upstairs for our neighbor that lived above us. I would…make $20 a night and I would give that $20 to my mother every morning just so she could get [heroin]….[Later] my mom…was on methadone maintenance for eight years at 180 milligrams and they detoxed her in two weeks and…. she had a seizure and she died… (Participant 22).

Some experienced the SDH of trauma from multiple overdose deaths in the family, with years of substance use, arrests of self and others, intermittent sobriety, and the subsequent health risks of using drugs. This commonly reported experience was paradoxical, as these deaths could have motivated her to stop using, rather than to use drugs to numb the depression and PTSD from the losses. As one woman describes:

I was 13 [when I started]…taking the Xanax and the methadone pills…It took my pain away because my dad overdosed [and died]…when I was eight…I ended up going to jail, and my stepdad was using, too, and I was using [with my sister]. I got [my stepfather] hooked so he’d have to get…drugs every day. He’d cover my habit, too. My mom was in jail at some point and then I ended up getting arrested….I got out, was supposed to go to a rehab, never went, came back on a warrant, did my time, and out. I turned 18 in the holding center, but my sister ended up showing up… My sister, as soon as she got out of prison, within an hour, she overdosed and then she overdosed six more times that week. They say cats have nine lives. She just didn’t want to get better and then the last time she overdosed…she didn’t make it. (Participant 8).

Another form of the SDH of child abuse is witnessing abuse, particularly of a parent or sibling, as the participant below describes. For all the participants who had this experience, it was part of a constellation of domestic violence, neglect, and criminal behavior at home that contributed to health outcomes of PTSD and substance use:

My dad used to hit my mom in front of me. My dad used to hit my brother. My brother was two years younger than me and there’s no reason for the amount of force and the way that my father treated my brother…there is no reason that you should beat a baby… He was two years old and he was smacking…him until he got bruises. (Participant 35).

One woman attributed her later PTSD, substance use, and criminal behavior that resulted in losing custody of her child to the SDH of witnessed abuse she experienced as a child.

I have nothing to show for my life…I don’t even have custody of my own child and I think a lot of my drug use came from my past [which] was very, very rough. I mean, from the time I was little, I watched my dad beat up my mom and almost kill her when I was four. My stepdad used to beat me. Since I was 10, I raised my brother and sister…When my brother passed…I just didn’t care anymore. (Participant 10).

The participant below describes how the SDH of her childhood trauma, the recurring cycle of physical abuse in her family, and her IPV victimization contributed to her subsequent violent behaviors:

I’ve got a heart of gold but if you make me snap, it’s bad…I think it has a lot to do with my upbringing of my dad beating my mother. And then my mom finally stabbed him and almost killed him and he stopped hitting her. So my fear was always if you put my hands on me, I’m just going to stab you…And I did some damage to [my ex], but he was a woman beater… (Participant 22).

Adult Abduction and Assault

Five participants experienced the SDH of abduction and sexual assault, a particularly severe form of adult trauma. For the woman below, it related to human trafficking which could result in severe physical and emotional health risks and being arrested:

I got kidnapped [for a year and a half]…I have been brought to [City] before, and they would just feed me drugs. They’d take all my money that I made…And if we didn’t have the money to pay him, if we didn’t make the money, he would have his friends sleep in front of the door so we couldn’t get out of the room. (Participant 9).

For this next woman, her drug use contributed to her inability to protect herself from the physical and mental health consequences of abduction and rape, and it is possible that the SDH risk of stigma may have kept the police she called from helping her:

We started using back in 2009; slowly but surely, we lost the house, lost the cars, lost the TVs…and then my ex-fiancée actually got arrested…then I was kind of on my own and shortly after he left, I was kidnapped by a random…man. He took me to his house, and held me captive at knifepoint in his house for a year, and I was repeatedly raped….I finally escaped from the house and was able to contact the police. They came to the house, and I was out on the front lawn half-clothed and told them what had happened; that I had been held prisoner for the past year….They told me I had to leave or they were going to arrest me because it looked like I was harassing him because I was on the front lawn. (Participant 3).

In some ongoing relationships impacted by drugs, women were prevented from leaving and experienced violence, having to figure out how to stay safe:

It started with him being violent towards me and hitting me and punching me and taking his anger out at me, because when you’re on heroin you’re really violent. You turn violent and you’re more sensitive to things. So he would a lot of times hit me, a lot of times the police were called….I was coping with these feelings and I didn’t have anyone there, and it would just be me defending myself… and I had to learn how– brought into this new world of drugs and dealing with that. (Participant 8).

Trajectory from Lifetime Abuse, Substance Use, and Criminal and Antisocial Behaviors to Sobriety

As noted, childhood and/or adolescent abuse preceded later adult victimization and criminal behaviors. Some women described experiencing adolescent or adult IPV and taking prescribed opioids to treat ensuing chronic pain as one pathway to developing an OUD. This participant summarizes a similar trajectory many women experienced which began with childhood abuse and culminated into antisocial and criminal behaviors that resulted in losing custody of their children. As one participant explained, she was able to seek sobriety and change:

I first started using when I was 13. I started drinking at my dad’s house and I would drink with my dad, with my siblings…to the point where I would be throwing up, passed out. Then…I was sexually abused and I’d seen somebody killed in my dad’s house. It just progressively got worse. Then at 17, I started taking pills with my mom… Then I got hit by a drunk driver and I got prescribed Lortab and Soma. I started taking them and then it progressed on from there. Then I was 23 and I started sniffing heroin…Then I got really bad into drinking again and…I had my first son when I was 23…I was using my whole pregnancy and then I finally got in the methadone clinic…then I started smoking crack… I was smoking for about three years…It was downhill from there. I lost everything. I lost custody of my kid…You do anything; you sell yourself, you steal, you lie…I got pregnant again, and the guy that I got pregnant by was beating me and tried to force me to have an abortion…I can’t do this anymore, so I went and I got [sober]. (Participant 14).

Role of Friends and Family Support in Recovery

With many friends and family with whom the women had experienced the SDHs of abuse, alienation, and/or substance use, some found support from them and some only from counselors or court staff. Several participants described family members or friends who either had given up on them, withheld their children, or would no longer remain in contact for various reasons. However, many developed the ability to utilize the SDH of support from some people, while staying away from those who would sabotage them as the two women below describe:

When I was in active addiction, I didn’t talk to them for 13 years. They just started coming back around again. They go to Al-Anon meetings to educate themselves about what I’m going through, but it’s going to be a really slow process…for them to understand…They want to get it, but they just don’t…We don’t know each other…I’ve been on my own for so long and I haven’t talked to them in so long that we’re just starting to know each other again, which is weird but it’s nice. (Participant 41).

I’ve got friends that are very supportive of me. My best friend…he’s tried to detox me cold turkey three times in his house and literally held me while I sat there and cried and shook…My dad is supportive of me but he’s on his tough love thing, but he’s coming around a lot…All he wants to do is see me clean. My mom, I’m not sure at this point…I do not put it past her if given the opportunity and situation that she would not intentionally sabotage me…in order for her to obtain drugs she would have no problem asking me to get them for her and therefore that’s why…I’m glad that we’re not around each other at this moment because right now it’s crucial in me getting and staying clean and…in order to serve her needs and wants…I think that she would disregard the entire fact of what I’m trying to do. (Participant 35).

These participants’ experiences highlight some of the distinctions between positive and negative outcomes, and the role of support therein.

Role of Treatment and Opioid Court in Recovery

Most women noted a trajectory of getting help, sobriety, and relapse. There were a number of approaches that they described as being beneficial but also several relapses after treatment and repeated attempts to enact changes. They described rigid treatment programs or those without trauma-informed care as less effective. The participant below was motivated from desperation and fear to utilize the SDH of transportation and her treatment program after multiple tries.

I have to because I don’t have a choice. I don’t want to die. I don’t want to go back to that and the dope that’s out there now…I’m scared shitless of it so I make sure I have a ride every single day to come out here because I don’t have a vehicle. I can’t drive. They took my license so I take a Medicaid cab every single day….I go to groups at that clinic and I see my counselor once or twice a week. I think that’s helped tremendously….I didn’t even think about that before but it has helped me a lot. Just to even hear how other people are struggling too; it’s not just my struggle. This is an epidemic….This is not a joke…how many? My friend died. My brother died. I know like six or seven people just within the past two years that have passed away from dope…And most of them are under the age of thirty….I have been in jail and I’ve missed doses but I get real sick and I have to go every day. I go religiously. (Participant 6).

Women described mixed feelings about OC. On the one hand, they did not like sitting for hours in court, but on the other hand, they appreciated the support of the court staff and judge, the legal benefits, and rapid access to treatment:

When I was in rehab, my counselor was able to work with…opiate court [case manager] and get my warrants gone…that was the last time I was arrested, which ultimately led me to go to treatment, and then all my cases are now linked in opiate court instead of having it be several different judges. (Participant 21).

The women described repeated relapses, which are consistent with the disease of addiction. It seemed that having programs, including the form of medication for OUD that they found effective after repeated attempts, available to them when they were ready to participate was the key to their recovery.

Discussion

We qualitatively explored women OC participants’ experiences with trauma as children, adolescents, and adults with an SDH framework, with the following six themes: child or adolescent abuse as triggers for drug use; impact of combined child or adolescent abuse with loss or witnessing abuse; adult abduction or assault; trajectory from lifetime abuse, substance use, and criminal and antisocial behaviors to sobriety; role of friends and family support in recovery; and role of treatment and opioid court in recovery, which we related to SDH, gender-based criminogenic factors, and public health. Our findings support earlier studies that childhood exposure to multiple forms of abuse, trauma, and the disruption of family bonds leave adolescent girls vulnerable to attachment disorders and criminogenic risk (Dishon-Brown et al., 2017; Ryder, 2014). Our contributions to the literature explicates how this common trajectory could be prevented and mitigated through an SDH framework to address gender-based criminogenic risk and public health concerns (Kennedy, 2016; Zweig et al., 2012).

The women recognized the significance of their childhood and adolescent trauma experiences in shaping their lived adult experiences. The years of intergenerational substance use and victimization during childhood and adolescence progressed to: adult drug use, loss of child custody, stealing, sex work, IPV, and adult mental and physical health disorders. Relative to DTCs, OCs utilize incarceration less frequently, which may be less trauma-inducing (Morse et al., 2014). It is worthy of further study to examine whether OC treatment strategies grounded in gendered criminogenic risk assessment and trauma-informed care could impact participants’ self-reported trajectories at the structural determinant level of the SDH. Such studies could result in adoption of long-recommended trauma and gender-informed approaches.

Multiple researchers have established a gendered pathway from child, adolescent, and/or adult sexual abuse to substance use and mental health disorders and criminal behaviors (Bowen et al., 2018; Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2009). The women in our study recognized this connection, but despite years of effort, had not been able to mitigate their behaviors. Trauma-responsive treatment encompasses both trauma-informed and trauma-specific strategies (DeCandia et al., 2014; Fallot et al., 2011). Emotional abuse in the form of control or neglect was a common trigger for substance use and/or criminal behavior. Stories shared by women often described their development of a cycle of substance misuse in response to the frustration, hurt, and anger they felt. Breaking this cycle was important to their recovery. Trauma-responsive SUD treatment typically address these responses (Harris et al., 1998) and is recommended for those who have experienced victimization; yet, this is not universally available (Bloom & McDiarmid, 2000; Hall et al., 2013). Trauma-informed approaches typically seek to maximize client control and autonomy (Fallot et al., 2011), operating at the intermediary level of the SDH. While OC links participants to substance use treatment, that treatment may not be trauma responsive, nor is mental health treatment generally a specific goal of therapy courts. Examination of such approaches could contribute to their implementation. Our study highlights the reality that insight regarding the reasons contributing to substance use does not ensure recovery, which may be particularly important for women with trauma experiences and also worthy of future study.

Among study participants, five described combined abduction and sexual assault (16%), including for long periods and/or being trafficked. Human trafficking is known to result in long-term mental and physical health sequelae (Hossain et al., 2010). These extreme consequences highlight the importance of justice and health systems role in assessing and responding to this experience at both the structural and intermediary SDH.

In the county where study recruitment occurred, when compared with census data, disproportionate numbers of Black individuals were arrested for misdemeanor drug charges and participated in this OC, which is the general pattern in the U.S. Across the U.S. in 2018, 10.2 in 100,000 White compared with 7.2 in 100,000 Black women died of an opioid overdose. However, in this OC, women’s participation rates do not reflect these trends (Murphy et al., 2021). While 48% of all OC participants identified as Black, only 20% of this study’s women OC participants identified as Black. Furthermore, we had only one Black woman study participant and she did not complete the interview which she described as due to extraneous circumstances. It is possible that there was system-based mistrust among Black women that impacted OC acceptance or that there was racial bias in who was offered OC as an alternative to incarceration. Our experience mirrors the predominant attention to Whites in addressing the opioid epidemic. Yet, from 2015 to 2016, there was a disproportionate 40% increase of Black opioid overdose deaths compared to the overall U.S. population increase of 21% (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). This increase in overdose deaths among Black persons was the highest across all racial and ethnic U.S. populations, which co-occurs with racial disparities in incarceration (Hill, 2018), and indicates the urgency of addressing this SDH in health and justice systems.

Rooted in social justice, the discipline of public health is centrally concerned with both physical health and SDH. With an interdisciplinary team, this study gained a richer understanding of gender-based criminogenic risks of trauma-related experiences, and their impacts on multiple life domains for women. Our findings support a greater recognition of a public health role in improving population-based health outcomes, from individual-level to systemic change, by focusing on adverse experiences in early life and adulthood, and their impact on health outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). If the justice system had a public health informed approach, courts could impact the intergenerational trajectory of substance use and overdose deaths through requiring trauma and gender-informed, evidence-based interventions for children, adolescents, and women in particular.

The women in this study had mixed SUD with opioid dependence, which is a significant public health and SDH issue. Recent attention to the opioid epidemic has highlighted the role of the medical community in over-prescribing opioid pain medication, both to adolescents and adults (Muhuri et al., 2013). Still, the reasons for the increased percentage of women with opioid dependence from 20% to 50% remain unclear. Women are more likely to have chronic pain and seek medical care after multiple abuse experiences, which could have predisposed them to opioid pain utilization (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021; Hayes, 2015). The overlapping conditions of chronic pain and physical abuse in women are worthy of further study, examining whether treatment of both may be synergistic and public health and SDH implications.

The themes of trauma in our participants’ narratives included family substance use beginning at an early age for a number of women. Given participant experiences, the ensuing family disruption in the home could have contributed to childhood and/or adolescent rape, which had long-term consequences for women (Ryder, 2014). Compounding the sexual trauma, neglect in the form of lack of food and structure in the home contributed to illegal subsistence behaviors during adolescence, such as theft and selling drugs, which propagated a cycle of trauma, mental and physical health problems, substance use, sex work, and incarceration. This gender-based and SDH criminogenic risk for illegal behaviors is yet another indication for more risk-responsive approaches for women in medical, mental health, and justice settings as part of a complementary public health approach (Daly, 1992).

Another fairly common form of trauma was the death of a parent and/or sibling to overdose during the women’s childhood and/or adolescence. Though not a form of abuse, this co-occurred with various forms of abuse and left the women who experienced it needing to process an enormous loss with no opportunity to do so. Others have described the importance of considering all such adverse childhood experiences, including death of a loved one and the desire to escape insecure home environments as a prime risk for SUD (Boppre & Boyer, 2019). The trauma superimposed with other abuse experiences was devastating and contributed to PTSD and self-medicating with various substances. These deaths were likely reported to police, health, and perhaps school officials, but women primarily described assistance from substance-using family members. Rather than relying on poorly equipped family members, a systemic public health–based response to this SDH may be helpful in preventing gender-based criminogenic risk. County health departments are typically informed of all fatal and nonfatal opioid overdoses (Bogira, 2014) and could create a health and justice response team to offer assistance to families, specifically including children. This type of public health response could be studied and if found beneficial, disseminated nationally.

Child witnessing of IPV is a known risk factor for depression, death, SUD, and future victimization (Wathen & MacMillan, 2013). In our sample, witnessing IPV was a common part of a family violence pattern. As these situations are reported to police, health care providers, child protective agencies, or IPV agencies, there is an opportunity for a coordinated public health response to address the SDH needs of impacted children which could be implemented on a county-wide level. Utilizing this coordinated response could provide assistance, rather than punitive strategies for OC consumers and others entering various health, justice, or social systems.

The women in our study described a clear trajectory, from their parents’ substance use, their childhood victimization and trauma, and eventually, their own substance use, criminal and antisocial behaviors, and adult victimization. Yet, there is evidence that a history of child and lifetime sexual abuse is an independent risk for longer sentences for women (Kennedy et al., 2018). All participants have interacted with several potentially helping agencies, such as schools, public assistance, health, jail, and courts (Cerulli et al., in press). At the point when we encountered them in our study, they were in the OC, which is a new, therapeutic and non-punitive response by the justice system to the opioid epidemic. For women who have experienced a gender-based criminogenic risk pathway to the court system, it is worth considering whether this new less punitive Court could adapt and measure SDH-informed and trauma-responsive approaches to this therapeutic response. It is worth noting that gender-based criminogenic risk measures are not widely used and warrant more detailed investigation for serious consideration into routine practice (Salisbury & Van Voorhis, 2009; Wright et al., 2007).

Echoing findings from prior research, study participants’ SDH-based trajectories to poor health and well-being were rooted in physical, mental, emotional, and social health problems (Sprague et al., 2017). Participants’ childhood and adolescent traumatic experiences, including interpersonal loss and the perpetuation of the cycle of violence, have important implications for substance use and violence prevention public health efforts. For example, there is an urgent need to interrupt the intergenerational cycles of not only physical and sexual violence, but also SUDs. In family court settings, court professionals often disregard SUD when issuing protective orders regarding family violence, including IPV. It is possible for courts to use legal leverage to intervene earlier in the substance use trajectory to require mental health treatment for trauma, as well as for SUD (Lamberti et al., 2004). Our findings have important SDH, public health, and criminal justice implications and may offer insight for various stakeholders, including national funders and policy makers, to call for research by interdisciplinary research teams into addressing developmental trajectories related to adverse early life experiences and their link to substance use behaviors in adulthood (Ryder, 2014).

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of our research is its novelty in describing a population of women participants in a fairly new, understudied intervention strategy to address the opioid epidemic. The population was similar to many in the U.S. who are experiencing opioid dependence: most were unemployed, with unstable housing, had children, and had high school or less education (Cicero et al., 2014). This exploratory study is limited by the women being in only one OC and almost all White, despite 20% participation in this OC by Black women. (While we did not experience refusal to participate by women of color, one consenting Black participant did not complete the interview). Court participants in this county are only recruited in jails and there are varied requirements for non-violent offenses across the U.S. We did not inquire about prior felonies and therefore did not account for them; it is possible that women with more serious charges have different experiences. While women often suggested a linear route linking from trauma to incarceration, our methodology cannot verify a direct causal relationship between early life experiences and subsequent behaviors in adulthood. Prospective studies beginning in child and teen years could examine the impact of trauma on future mental health diagnoses, substance use, and resilience, as well as potential mitigating effects of preventive interventions, but would have to carefully address ethics in research. Only 24 of our 31 participants reported child, adolescent, or adult trauma in response to directly inquiry in their interviews; while this is a majority, it could represent an underestimate as some may not have wished to disclose. Lastly, opioid-dependent women who did not have criminal justice involvement could have had different child, adolescent, and adult trauma and health trajectories, and our interviews did not include that experience.

Conclusions

Of the 31 women Opioid Intervention Court participants who shared their stories of substance use and criminal justice involvement, 77% described child and/or adolescent victimization, 48% IPV, and 16% abduction and sexual assault. These women described SDH barriers and gender-based criminogenic risk trajectories that included profound disruption of family structure, intergenerational substance use, death of close relatives, and introduction to substance use and criminal behaviors at an early age. These experiences predisposed women to further physical and mental health disorders. This study supports the utility of increased use of gender-based criminogenic risk measures and responses, combined with coordinated court-public health system responses, and overall attention to SDH. Our findings inform future research and practice with women OC participants, as well as children in at risk situations and the multiple systems with which they interface.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the participants who generously contributed their time.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding for this research was supported by the University of Rochester Center for AIDS Research grant P30AI078498 (NIH/NIAID).

Biographies

Diane S. Morse, MD is an Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Medicine at the University of Rochester School of Medicine, researcher, medical educator, and internal medicine physician. She investigates implementation of evidence-based interventions with justice-involved individuals. She works to increase needed health services for medical, substance use disorder, and psychiatric conditions. She uses qualitative, quantitative, and community-based participatory research strategies.

Catherine Cerulli, JD, PhD is a Professor of Psychiatry, Director of the Laboratory of Interpersonal Violence and Victimization, and the Director of the Susan B. Anthony Center at the University of Rochester. She has extensive experience working directly to preserve and enhance the human rights of people who are marginalized due to violence, economics, safety, health disparities, or legal concerns.

Melissa Hordes, MPH, is a Research Associate at Denver Public Health, managing a study designed to improve engagement and retention in opioid use disorder care among individuals on medication for opioid use disorder. She has worked on multiple research projects involving opioid use disordered individuals at the University at Buffalo, University of Rhode Island, and Rhode Island Department of Health.

Nabila El-Bassel, PhD is a Professor at Columbia University School of Social Work. She directs multidisciplinary research focused on developing and testing prevention and intervention approaches for HIV, drug use, and gender-based violence, and disseminating them to local, national, and global communities. She is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Jacob Bleasdale is a PhD Student in the Department of Community Health and Health Behavior at the School of Public Health and Health Professions, University at Buffalo. His research focuses on HIV prevention and quality of life measures for people living with HIV. He is interested in using qualitative and quantitative methodologies to identify areas for intervention development.

Kennethea Wilson, MPH, is a public health mixed-methods researcher, focused on the prevention of adverse reproductive and sexual health outcomes, including HIV/STIs, unintended pregnancy, and coercion, among minorities. She completed a CDC infectious disease control fellowship at Johns Hopkins University. She is a research associate at the University at Buffalo School of Public Health and Health Professions.

Olivia Henry worked in this project as a Research Assistant at the University at Buffalo in the Department of Community Health and Health Behavior in the School of Public Health and Health Professions. She is an undergraduate student in Political Science, and plans to pursue her Master’s degree in Early Childhood Education.

Sarahmona M. Przybyla, PhD, MPH, is a public health interventionist with extensive training in HIV/STI prevention, substance use, and mixed methods research. She is an assistant professor in the Department of Community Health and Health Behavior and Assistant Dean, Director of Undergraduate Public Health Programs at the University at Buffalo’s School of Public Health and Health Professions.

Footnotes

Compliance With Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subject Review Board (RSRB case number: 72930). All participants provided written informed consent.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Altintas M, & Bilici M (2018). Evaluation of childhood trauma with respect to criminal behavior, dissociative experiences, adverse family experiences and psychiatric backgrounds among prison inmates. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 82, 100–107. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias I (2004). Report from the CDC. The legacy of child maltreatment: Long-term health consequences for women. Journal of Women’s Health, 13(5), 468–473. 10.1089/1540999041280990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour RS (2001). Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: A case of the tail wagging the dog? British Medical Journal, 322(7294), 1115–1117. 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B, & McDiarmid A (2000). Gender-responsive supervision and programming for women offenders in the community (pp. 11–18). Topics in Community Corrections. [Google Scholar]

- Bogira S (2014). No money for treating the traumatized. https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/safe-start-therapy-violence-social-worker-children-trauma-ptsd-south-side/Content?oid=15390389 [Google Scholar]

- Boppre B, & Boyer C (2019). “The traps started during my childhood”: The role of substance abuse in women’s responses to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 30(4), 1–21). 10.1080/10926771.2019.1651808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen K, Jarrett M, Stahl D, Forrester A, & Valmaggia L (2018). The relationship between exposure to adverse life events in childhood and adolescent years and subsequent adult psychopathology in 49,163 adult prisoners: A systematic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 131, 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). Preventing adverse childhood experiences. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/fastfact.html [Google Scholar]

- Cerulli C, Morse D, Hordes M, Bleasdale J, Wilson K, Schwab Reese LM, & Przybyla SM (in press). Understanding lived experiences: Female opioid court participants share narratives of interactions with siloed medical, legal and social service systems. Journal of Correctional Health Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, & Kurtz SP (2014). The changing face of heroin use in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(7), 821–826. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly K (1992). Women’s pathways to felony court: Feminist theories of lawbreaking and problems of representation. Southern California Review of Law and Women’s Studies, 2(1), 11–52. [Google Scholar]

- DeCandia CJ, Guarino K, & Clervil R (2014). Trauma-informed care and trauma-specific services: A comprehensive approach to trauma intervention. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Trauma-Informed%20Care%20White%20Paper_October%202014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dishon-Brown A, Golder S, Renn T, Winham K, Higgins GE, & Logan T (2017). Childhood victimization, attachment, coping, and substance use among victimized women on probation and parole. Violence and Victims, 32(3), 431–451. 10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-15-00100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallot RD, McHugo GJ, Harris M, & Xie H (2011). The trauma recovery and empowerment model: A quasi-experimental effectiveness study. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 7(1–2), 74–89. 10.1080/15504263.2011.566056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Brady JE, West BS, Pouget ER, Williams LD, Des Jarlais DC, & Cooper HLF (2016). Income inequality, drug-related arrests, and the health of people who inject drugs: Reflections on seventeen years of research. International Journal of Drug Policy, 32, 11–16. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friestad C, Åse-Bente R, & Kjelsberg E (2014). Adverse childhood experiences among women prisoners: Relationships to suicide attempts and drug abuse. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(1), 40–46. 10.1177/0020764012461235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Borrell LN, Latkin CA, Galea S, Ompad DC, Strathdee SA, & Vlahov D (2005). Effects of race, neighborhood, and social network on age at initiation of injection drug use. American Journal of Public Health, 95(4), 689–695. 10.2105/AJPH.2003.02178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, & Vlahov D (2002). Social determinants and the health of drug users: Socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health, 117(1), S135–S145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg ZE, Chin NP, Alio A, Williams G, & Morse DS (2019). A qualitative analysis of family dynamics and motivation in sessions with 15 women in drug treatment court. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 13, 117822181881884. 10.1177/1178221818818846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MT, Golder S, Conley CL, & Sawning S (2013). Designing programming and interventions for women in the criminal justice system. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(1), 27–50. 10.1007/s12103-012-9158-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M, Anglin J, & Community Connections (Washington, D.C.). Trauma Work Group (1998). Trauma recovery and empowerment: A clinician’s guide for working with women in groups. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MO (2015). The life pattern of incarcerated women: The complex and interwoven lives of trauma, mental illness, and substance abuse. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 11(4), 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Jung H, Lee JO, & Kim M (2017). Effects of child maltreatment, cumulative victimization experiences, and proximal life stress on adult crime and antisocial behavior. National Criminal Justice Reference Service. [Google Scholar]

- Hill H (2018). Report to the United Nations on racial disparities in the U.S. criminal justice system. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/un-report-on-racial-disparities/ [Google Scholar]

- Hill CE, Knox S, Thompson BJ, Williams EN, Hess SA, & Ladany N (2005). Consensual qualitative research: An update. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 196–205. 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins KM, & Morash M (2020). How women on probation and parole incorporate trauma into their identities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(23-24), NP12807–NP12830. 10.1177/0886260519898426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Abas M, Light M, & Watts C (2010). The relationship of trauma to mental disorders among trafficked and sexually exploited girls and women. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2442–2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes T, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, & Boyd CJ (2010). Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction, 105(12), 2130–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MS, Worthen MGF, Sharp SF, & McLeod DA (2018). Bruised inside out: The adverse and abusive life histories of incarcerated women as pathways to PTSD and illicit drug use. Justice Quarterly, 35(6), 1004–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SC (2016). The relationship between childhood polyvictimization and subsequent mental health and substance misuse outcomes for incarcerated women. [Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University; ]. http://purl.flvc.org/fsu/fd/FSU_2016SP_Kennedy_fsu_0071E_13166 [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy SC, Mennicke AM, Feely M, & Tripodi SJ (2018). The relationship between interpersonal victimization and women’s criminal sentencing: A latent class analysis. Women & Criminal Justice, 28(3), 212–232. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti JS, & Weisman RL (2004). Persons with severe mental disorders in the criminal justice system: challenges and opportunities. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 75(2), 151–64. DOI: 10.1023/b:psaq.0000019756.34713.c3. 1516883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Rose G, Shipley M, & Hamilton PJ (1978). Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. Journal of epidemiology and community, 32(4), 244–9. DOI: 10.1136/jech.32.4.244. 744814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Smith GD, Stansfeld S, Patel C, North F, Head J, White I, Brunner E, & Feeney A (1991). Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet, 337(8754), 1387–93. DOI: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k.1674771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse DS, Cerulli C, Bedell P, Wilson JL, Thomas K, Mittal M, Lamberti JS, Williams G, Silverstein J, Mukherjee A, Walck D, & Chin N (2014). Meeting health and psychological needs of women in drug treatment court. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(2), 150–157. 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, & Davies MC (2013). Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin use in the United States. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/associations-nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-and-initiation-heroin-use-united-states [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Arias E, & Tejada-Vera B (2021). Deaths:Final data for 2018. National Vital Statistics Reports, 69(13), 1–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Justice (2020). Overview of drug courts. https://nij.ojp.gov/topics/articles/overview-drug-courts [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (2020). Overdose death rates. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates [Google Scholar]

- New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (2020). Adult arrest demographics by county and region. https://www.criminaljustice.ny.gov/crimnet/ojsa/adult-arrest-demographics.html [Google Scholar]

- Park JN, Rouhani S, Beletsky L, Vincent L, Saloner B, & Sherman SG (2020). Situating the continuum of overdose risk in the social determinants of health: A new conceptual framework. The Milbank Quarterly, 98(3), 700–746. 10.1111/1468-0009.12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera EA, Phillips H, Warshaw C, Lyon E, Bland PJ, & Kaewken O (2015). An applied research paper on the relationship between intimate partner violence and substance use. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ryder JA (2014). Girls and violence: Tracing the roots of criminal behavior. Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury EJ, & Van Voorhis P (2009). Gendered pathways: A quantitative investigation of women probationers’ paths to incarceration. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(6), 541–566. 10.1177/0093854809334076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shokoohi M, Bauer GR, Kaida A, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Milloy MJ, Lloyd-Smith E, Carter A, & Loutfy M, CHIWOS Research Team (2019). Patterns of social determinants of health associated with drug use among women living with HIV in Canada: A latent class analysis. Addiction, 114(7), 1214–1224. 10.1111/add.14566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar O, & Irwin A (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO Document Production Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sormanti M, Pereira L, El-Bassel N, Witte S, & Gilbert L (2001). The Role of Community Consultants in Designing an HIV Prevention Intervention. AIDS Education and Prevention, 13(4). 10.1521/aeap.13.4.311.21431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague C, Scanlon ML, & Pantalone DW (2017). Qualitative research methods to advance research on health inequities among previously incarcerated women living with HIV in Alabama. Health Education & Behavior, 44(5), 716–727. 10.1177/1090198117726573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2020). The opioid crisis and the black/african American population: An urgent issue office of behavioral health equity. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Publication No. PEP20-05-02-001. [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi SJ, & Pettus-Davis C (2013). Histories of childhood victimization and subsequent mental health problems, substance use, and sexual victimization for a sample of incarcerated women in the US. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36(1), 30–40. 10.1016/j.ijlp.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau (n.d.). QuickFacts: Erie County. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/eriecountynewyork [Google Scholar]

- VanHouten J, Rudd R, Ballesteros M, & Mack K (2019). Drug Overdose Deaths Among Women Aged 30–64 Years - United States, 1999-2017. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(1), 1–5. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6801a1. 30629574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wathen CN, & MacMillan HL (2013). Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Impacts and interventions. Paediatrics & Child Health, 18(8), 419–422. 10.1093/pch/18.8.419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson ST (2018). Opioid courts expand in Erie, Niagara counties to tackle epidemic. The Buffalo News. https://buffalonews.com/2018/10/25/opiate-courts-expand-in-erie-niagara-counties-to-tackle-epidemic/ [Google Scholar]

- White HR, & Widom CS (2008). Three potential mediators of the effects of child abuse and neglect on adulthood substance use among women. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69(3), 337–347. 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winham K, Engstrom M, Golder S, Renn T, Higgins G, & Logan T (2015). Childhood victimization, attachment, psychological distress, and substance use among women on probation and parole. The American journal of orthopsychiatry, 85(2), 145–158. DOI: 10.1037/ort0000038. 25822606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright EM, Salisbury EJ, & Van Voorhis P (2007). Predicting the prison misconducts of women offenders: The importance of gender-responsive needs. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(4), 310–340. 10.1177/1043986207309595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig JM, Yahner J, & Rossman SB (2012). Does recent physical and sexual victimization affect further substance use for adult drug-involved offenders? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(12), 2348–2372. 10.1177/0886260511433517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]