Abstract

The current consensus in the management of hypopharyngeal cancers favors the non-surgical management. However, many studies have reported relatively better oncological and functional outcomes with the surgical approach in locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers. In here, we report a tertiary care center’s experience with total laryngopharyngoesophagectomy with gastric pull-up done for such cases. We also describe a slight modification of the procedure that has been followed at our institute, and discuss its advantages. It is a retrospective study of patients who have undergone the surgical procedure between the September 2016 and the March 2019. The primary objective was to analyze the surgical complications and the benefits in terms of disease clearance, survival duration, and functional outcomes. Study consisted of 15 patients, mostly men, with mean age of 56 years. 12/15 had stage IV disease and 7/15 were failed chemoradiotherapy. Most common complication of surgery was anastomotic failure (33%). Perioperative mortality rate was 13.3%. Higher complications could probably be attributed to poor nutrition and tension over the anastomosis. Mean survival duration and disease free interval were 12.1 and 11 months, respectively. Oral feeds was restored in 77%, and the average time to restore oral feeds was 17 days. Most of our results were comparable with the literature, which supports the surgical excision of larynx–pharynx–esophagus and reconstruction by pull-up, in all those medically fit cases of radio-recurrent/residual tumors, and also in primary cases of locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers with non-functional larynx. In these scenarios, the radical surgical treatment would atleast serve as palliative if not curative.

Keywords: Hypopharyngeal cancer, Total laryngopharyngectomy, Gastric pull-up, Gastric transposition, Jejunal free flap, Pharyngeal reconstruction

Introduction

Most of the hypopharyngeal cancers present in an advanced stage and carry a poor prognosis [1, 2]. The 5-year survival rates of hypopharyngeal cancers vary between 34 and 41.3%, which is much lower than the survival rates of other head and neck cancers [2–4]. Though, the survival benefits in hypopharyngeal cancers in general do not differ significantly between the surgical treatment and the organ preservation protocols, the consensus has been favoring the latter because of the reasonable organ preservation rates associated with it [2, 3, 5, 6]. But when it comes to the locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers, many authors have reported a better survival outcome with surgical treatment with (or without) adjuvant radiotherapy [2, 4–6]. For such locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers, the conventional surgical treatment is the total laryngopharyngoesophagectomy (TLPE) with the reconstruction of pharyngo-esophagus by the gastric pull-up (GP). Lately, the esophagus sparing total laryngopharyngectomy with reconstruction by fasciocutaneous, musculocutaneous or jejunal free flaps are also increasingly becoming popular in this regard [7–9]. However, there are issues related to oncological safety of preserving esophagus in hypopharyngeal cancers when there is a significantly higher probability of skip lesions or second primary in the esophagus [10–15]. Moreover, the cost and the expertise involved in microvascular reconstruction, and the patients’ willingness or availability for long term follow up are some of the other concerns that are still relevant in developing countries. For all these reasons, TLPE remains to be one of the commonly performed surgeries for locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers across the globe. The criticism of high morbidity and mortality associated with TLPE is also falling out of favor, as these rates are reducing significantly over last few decades [16, 17]. The present study is a single-center experience with TLPE and GP reconstruction done for locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers over 3 years. Along with the description of a slight modification of TLPE that we follow at our institute, we have also discussed the peculiarity of results seen in our study with the appropriate literature review.

Materials and Methods

Study Details

It is a retrospective study analyzing the functional as well as oncological outcomes of TLPE with GP in patients of locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers. For this study, the relevant data of the patients who had undergone the surgical procedure between the September 2016 and the March 2019 in the department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck surgery of a tertiary care hospital was retrieved from the medical records department. The primary objective of the study was to analyze the surgical morbidity and mortality, and the benefits of surgery in terms of disease clearance, survival duration as well as the functional outcomes among the patients undergoing the TLPE with GP. After obtaining the approval of the institutional review board and the ethical committee, the data retrieval and the data analysis were carried out from April 2019 to July 2019. Patients who had received treatment for some other head and neck cancer in the past other than for the hypopharyngeal cancer and those with incomplete medical information were excluded from the study. The data tabulated included demographics, disease characteristics, oncological clearance, post-operative complications, biochemical changes, oral feeding restoration, and survival status until the last follow up date or death. The parameters considered for defining the functional results of the TLPE with GP included the oral feeding restoration rates and the time since surgery for restoration of the oral feeds. Owing to the smaller sample size and the shorter follow-up duration of the study, instead of the survival analysis, some of the unconventional parameters like the post-operative morbidity rates, the disease-free interval, and the survival time since surgery were used for defining the clinically meaningful oncological results.

Procedure Details

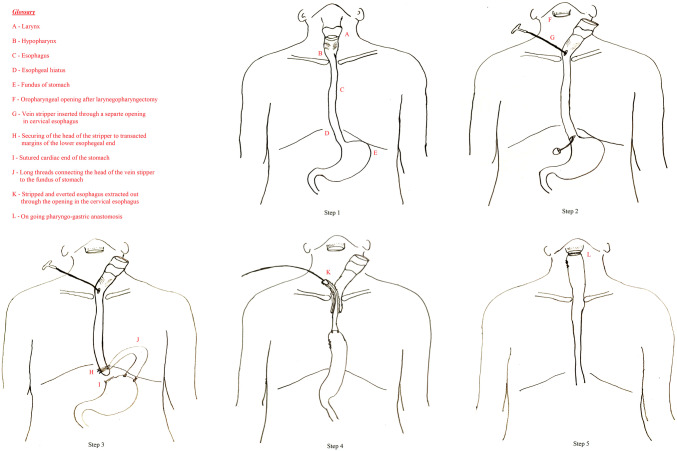

The surgical procedure of TLPE with GP had been carried out by a surgical team that included otolaryngologists and general surgeons. The standard surgical steps, as illustrated in Fig. 1 had been followed in the same defined order in all these patients, with some minor modifications at times as warranted intraoperatively. First, the head and neck surgeon performs the appropriate neck dissection and then mobilizes the laryngopharynx by a transcervical approach. This is followed by an entry into the larynx at the level of oropharynx and completion of the total laryngopharyngectomy, however, keeping intact the continuity with the esophagus. Meanwhile, the general surgeons do a laparotomy to prepare the stomach for the “pull-up” by careful mobilization of the stomach with preserved blood supply based on the right gastroepiploic vessels and in some cases even the right gastric vessels. The blunt finger dissection then widens the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm. The next step consisted of modified trans-hiatal esophagectomy by the transluminal upward eversion stripping method. In this, a varicose vein stripper is passed into the cervical esophageal lumen through a separately made opening and is pushed down the esophagus till it is felt at the gastroesophageal junction. Subsequently, the gastroesophageal junction is transacted, the stripper is brought out of the lumen, to which, a medium-sized stripper head is fixed and secured to the lower end of the esophagus with the help of stout silk sutures. The transacted cardiac end of the stomach is then closed in two layers. Two or three separate silk ties of around 20 to 25 cm length are secured to the bulb of the vein stripper and the other end of the ties sutured to the wall of the gastric fundus. Thereafter, gentle upward traction on to the cervical end of the vein stripper would strip off the esophagus from its fascial attachments in the mediastinum, and by progressive eversion of its lumen, the entire esophagus would now get delivered to the neck. At this juncture, the whole of the surgical specimen consisting of the larynx, the pharynx, and the esophagus gets removed en-block. The stomach can then be brought to the neck by the continued upward pull on the threads attached to the fundus of the stomach. The general surgeon assists this step by feeding the stomach through the posterior mediastinum with maintained anatomical orientation, to ensure an uncompromised vascular supply and less tension on the tissue. After getting the sufficient length of the stomach into the neck, the head and neck surgeon creates a separate opening on its highest point, and performs the anastomosis of this opening of the “pulled up” gastric conduit with the free margin of recipient pharyngeal opening, by interrupted sutures in two layers. This surgical procedure of TLPE with GP, especially the step of transhiatal esophageal extraction by the upward eversion stripping method using a vein stripper was pioneered at our institute a few decades ago and is still being followed routinely [18, 19].

Fig. 1.

Surgical steps of the total laryngopharyngoesophagectomy with gastric pull-up (for details of the steps, please refer the text)

Results

A total of 15 patients of locally advanced carcinoma of hypopharynx had undergone the TLPE with GP in the study period. Table 1 summarizes the demographics, the clinical manifestations, and the pre-operative characteristics of the study cohort. The patients included were belonging to the age group of 37–70 years, with a mean age of 56. Most of the patients in our surgical cohort were men with a ratio of 6:1. All the 15 patients had dysphagia of varying duration and severity. Most of the patients also had multiple other symptoms like hoarseness, aspiration, and respiratory difficulty and had undergone preoperative tracheostomy. The epicenters of the tumor origin in our study cohort were the pyriform sinus (n = 9) and the post-cricoid area (n = 6). Histologically, all patients except one had squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx, of varying differentiation. One patient had well-differentiated liposarcoma of the lower hypopharynx and upper esophagus. 12 of 15 patients had stage IV disease as per the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual. Though, six of our patients had one or more co-morbidities in the form of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or hypothyroidism, they were under appropriate treatment, and the general condition of all the patients was adequately preserved prior to the surgery. The procedure of TLPE with GP was done either primarily, as a part of the multimodal treatment plan in patients who had dysfunctional larynx (n = 8), or as a salvage surgery following the failure of non-surgical treatment (n = 7). Similarly, whenever deemed necessary oncologically, and feasible medically, the adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation or both had been offered to the patients after the TLPE (n = 5). Table 2 highlights the surgical profile of the study subjects, the post-operative course, and the outcomes of surgical procedure, in terms of disease clearance, surgical morbidity, functional restoration, and survival duration.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinico-pathological characteristics of the study cohort

| Indirect identifier | Age (years) | Sex | Comorbidities | Site | TNM stage | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPU 1 | 37 | M | Nil | PCA | cT3N0M0 | MD SCC |

| GPU 2 | 51 | M | Nil | PCA | T4aN2bM0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 3 | 51 | M | Nil | PCA | cT4bN0M0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 4 | 70 | M | DM, HTN | PFS | cT3N0M0 | WD liposarcoma |

| GPU 5 | 60 | M | Nil | PCA | cT4aN2bM0 | MD SCC |

| GPU 6 | 52 | M | HTN | PFS | cT4aN0M0 | MDSCC |

| GPU 7 | 68 | M | Nil | PFS | cT3N2cM0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 8 | 48 | M | Nil | PFS | cT4aN0M0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 9 | 60 | F | Nil | PFS | cT4aN0M0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 10 | 62 | M | DM, HTN | PFS | cT4aN0M0 | MDSCC |

| GPU 11 | 49 | M | HT | PCA | cT4aN0M0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 12 | 69 | F | Nil | PFS | cT4aN0M0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 13 | 44 | M | Nil | PFS | cT3N0M0 | MD SCC |

| GPU 14 | 45 | M | HT | PCA | cT4aN0M0 | WDSCC |

| GPU 15 | 70 | M | HTN | PFS | cT4a N0 M0 | MD SCC |

c clinical; DM diabetes mellitus; F female; GPU gastric pull up; HTN hypertension; HT hypothyroidism; M male; MD SCC moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma; PCA post cricoid area; PFS pyriform sinus; TNM tumor, neck node and metastasis (distant); WD SCC well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma

Table 2.

Surgical and post-surgical profile of the study subjects along with follow up details

| Indirect identifier | KPS | Type of surgery | Pathological risk factor | Post-operative morbidity-management | Serum studies | Oral feeds started on | Further course | Survival time since surgery (in days) | Disease free interval (in days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPU 1 | 90 | Primary | R0, N2b, ECE | Hypocalcemia—conservative | Low albumin | Day 12 | Discharged on Day 16, sudden cardiac death on day 29 | – | – |

| GPU 2 | 70 | Primary | R0, N0 | Pneumonia, hypotension and arrhythmia on day 3—death | Low albumin | NS | – | – | – |

| GPU 3 | 90 | Primary | R1, N0 | Nil | Low albumin | Day 14 | Adjuvant CTRT. Death due to unrelated cause after 1½ years | 502 | 502 |

| GPU 4 | 80 | Salvage | R0, N0 | PCF—conservative | Low albumin, Anemia | NS | Developed pneumonia, sepsis—expired on day 28 | – | – |

| GPU 5 | 90 | Primary | R0, N1 | MI on day 6—angioplasty | Nil | Day 12 | Adjuvant RT given. Recurrent MI at home after 1 year—death | 448 | 448 |

| GPU 6 | 70 | Salvage | R0, N0 | Pneumonia—conservative sudden cardiac death on day 3 | NA | NS | – | – | – |

| GPU 7 | 90 | Primary | R0, N2b | Nil | Low albumin | Day 15 | Adjuvant RT given. Alive and disease free | 727 | 727 |

| GPU 8 | 70 | Primary | R0, N0 | Hemorrhage, Gastric necrosis—blind sac closure of stomach upper end | Low albumin, Anemia | NS | Was on RT feeds. Had breathing difficulty—death at local hospital | 146 | 146 |

| GPU 9 | 90 | Primary | R0, N0 | Symptomatic Hypocalcemia, PCF—repair of fistula | Nil | Day 21 (Day 11 of repair) | Lost to follow up | 52 | – |

| GPU 10 | 90 | Salvage | R1, N0 | Nil | Nil | Day 31 | Alive, Regional recurrence—on palliative CT | 236 | 129 |

| GPU 11 | 80 | Salvage | R0, N0 | Nil | Low albumin | Day 17 | Local recurrence—excision with PMMC. Persistent disease—carotid blow out after 146 days of PMMC—death | 206 | 91 |

| GPU 12 | 90 | Salvage | R0, N0 | Hypocalcemia, PCF—conservative | Low albumin | Day 23 | Alive and disease free | 195 | 195 |

| GPU 13 | 90 | Salvage | R0, N0 | Nil | Nil | Day 13 | Adjuvant CT. Disease free for 1½ years. Expired due to stomal recurrence. | 575 | 461 |

| GPU 14 | 80 | Salvage | R0, N0 | Hypocalcemia—conservative | Nil | Day 13 | Alive and disease free | 523 | 523 |

| GPU 15 | 80 | Primary | R0, N1 | Gastric necrosis—conservative | Low albumin | NS | Received adjuvant RT. After 3 months—death due to sepsis secondary to gangrene of lower limb | 140 | 140 |

CT chemotherapy; ECE extracapsular extension; GPU gastric pull up; KPS karnofsky performance status; MI myocardial infarction; N0 no pathological node; N1 pathological positive lymph node; N2b multiple ipsilateral pathologically positive lymphnodes; NS not started; PCF pharyngocutaneous fistula; PMMC pectoralis major myo-cutaneous flap; R0 microscopic margin negative; R1 microscopic margin positive; RT radiotherapy

The procedure of TLPE was able to provide the oncological clearance of disease in 13 patients (86.6%). The major postoperative morbidities seen after TLPE with GP in our patients included pharyngo-cutaneous fistula (PCF) or frank gastric margin necrosis (GN), seen in 5 patients (33.3%), symptomatic hypocalcemia necessitating intravenous supplementation (n = 4, 26.6%), cardiac events like myocardial ischemia, arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death (n = 3, 20%), pneumonia/mediastinitis (n = 3, 20%) and hemorrhage from the surgical site (n = 1, 6.6%). In two of the anastomotic failure cases, the surgical explorations had been carried out within the first post-operative week itself. One was a case of gastric necrosis and evident leak of gastric contents who underwent surgical exploration with blind sac closure of the upper end of stomach, and the other was a case of high salivary output PCF who had the repair of fistula with augmentation by local muscular flap. In one of the other cases with a significant new-onset myocardial infraction, emergency angioplasty was carried out to restore the myocardial blood flow. Except for these three instances, all other post-operative complications were appropriately managed by aggressive medical treatment. Additionally, biochemical workup revealed hypoalbuminemia (n = 9, 60%) and anemia (n = 2, 13.3%), which were brought to normal limits within 2–3 weeks of the surgery by supplementation therapy. Overall, though the post-operative morbidity rate in our cohort was around 66.6% (n = 10 patients), most of them were transient and could be managed conservatively.

In terms of mortality, two patients in our cohort had succumbed within 3 days of surgery, both were due to pneumonia and sepsis, constituting perioperative mortality rate of 13.3% in our series. However, two more patients had expired within a month of the surgery, one due to a sudden cardiac event at home who was otherwise doing well with restored oral feeds, and the other, due to persistent PCF leading to sepsis. Among the remaining 11 patients, one patient had lost to follow up after 2 months of surgery, and six patients had expired subsequently. Of those six patients, four succumbed due to unrelated cause and the other two due to recurrent/metastatic disease. Additionally, one patient had developed inoperable local recurrence and was under palliative chemotherapy at the time of data analysis. Excluding the patient who lost to follow up after 2 months and those who succumbed within a month of surgery, the overall follow up duration in remaining ten patients including those who developed recurrence (n = 3) ranged from 4.6 to 23.9 months. Taking into account till the last date of follow up or the time of death in these ten patients, the mean and the median overall survival durations since the TLPE were 12.1 and 11.2 months, respectively. Similarly, the mean and the median disease-free intervals after TLPE were 11.0 and 10.5 months, respectively. Nevertheless, at the time of compilation of data for this study, only 4 out of 15 patients were alive, among whom only three were disease-free with a disease-free interval of 15.8 months.

With respect to the functional outcomes, excluding those two cases who could not make it beyond 3 days of the post-operative period, 8 out of 13 patients had resumed oral feeds within 2 weeks of surgery, and another two were started on an oral diet within the following 2 weeks, after managing their PCF. The restoration rates of oral feeds in our series was 77%, and the average time since surgery to restore the oral feeds in these ten patients was 17 days. In our series, none of the patients had undergone the tracheogastric puncture, and thus, further analysis concerning speech rehabilitation was not possible. However, the medical records revealed that most of the patients were able to produce monosyllable or bi-syllable words of low amplitude with the help of air entrapped in mouth, and refused secondary rehabilitative measures for speech restoration citing various reasons.

Discussion

Disa et al. [20] classified hypopharyngeal defects resulting from oncological excision of part or whole of the hypopharynx into three broad categories depending on the amount of tissue loss, and accordingly suggested the most appropriate free flap for reconstruction. The group had also identified another class of hypopharyngeal defect called type IV defect wherein the excision involves the thoracic esophagus. The best reconstruction option for such type IV defect as per the authors was GP [20]. Though many other options of reconstruction like pectoralis major flap, colon interposition, fasciocutaneous free flaps [like a radial forearm or anterolateral thigh flap], and free jejunum flaps have increasingly been tried over the years, most of these options are suitable for either type II or type III defects [8, 9, 21]. GP unequivocally remains the first choice of reconstruction after TLPE, which offers many unique advantages over other reconstruction options, as discussed in the subsequent paragraphs. The most basic and straightforward advantage of GP after TLPE is the single site end-to-end anastomosis of the digestive tract in the form of the pharyngo-gastric anastomosis to restore the oral feeding. Most of the other listed options would require multiple anastomoses of alimentary canal and even microvascular multi-vessel anastomoses. Since all our cases were locally advanced with dysfunctional larynx or failed chemoradiation, the preferred surgical procedure was TLPE with GP in all these cases, wherein we have used a modified technique for the transhiatal esophagectomy and gastric transposition.

The standard surgical procedure of TLPE with GP consists of four significant steps, namely transcervical laryngopharyngectomy, transhiatal esophagectomy, gastric transposition by laparotomy and 2-layered pharyngo-gastric anastomosis by interrupted sutures, in that order [17]. Several modifications in the standard procedure like the laparoscopic mobilization of the stomach, the thoracoscopic dissection of the esophagus and the stapler anastomosis of the pharyngo-gastric junction have been shown to reduce the morbidity and mortality of the TLPE and thus, are slowly gaining popularity [14, 22–24]. At our center, though we followed the standard procedure for TLPE, we used a modification in the step of transhiatal esophageal extraction, wherein instead of any dissection of the esophagus in the mediastinum, we used a vein stripper to avulse the esophagus from below upwards after esophagogastric separation [18, 19]. This vein stripper based eversion technique is based on the description by Akiyama et al., however, unlike their technique of downward eversion of the esophagus to abdomen, we do an upward eversion to the neck, to enable en-block removal of the whole of the surgical specimen [18, 19, 25]. This technique not only reduces the chances of mediastinal complications but also is simple to perform, reducing the operating time [18, 19, 25].

The procedure-related mortality rates of TLPE with GP reported in the literature varies between 0 and 50% [14, 16, 17, 19, 26–30], most of which can be attributed to respiratory events, consequences of anastomotic failure and cardiovascular complications, as is the case in our series. Similarly, the rates of post-operative morbidity of TLPE with GP across these studies varies from 0 to 66%. The most common of which is again anastomotic leak. Some authors have differentiated partial failure of the anastomosis from the complete circumferential failure of the anastomosis, though, such differentiation may not be technically possible many a times [31]. Together, these anastomotic failure rates are reported to be around 8–40% even in the recent years [26, 29, 32, 33], Interestingly, the morbidity and mortality of GP has been reported to be significantly less [34] or comparable to jejunal or other free flaps in previous reports [8, 9, 32]. Despite being comparable with the reported rates in literature, the procedure-related mortality and morbidity rates of TLPE with GP were relatively on a higher side in this series. Infact, the morbidity and mortality rates seen in these patients were higher than those reported in previously published studies from the same institute [18, 19], which we attribute to some of the unfavorable perioperative factors seen in current cohort.

In our cohort, almost all the cases had an advanced disease of the hypopharynx necessitating extensive resection of the laryngopharynx, and in many cases, the resection margin had extended high into the oropharynx. The resultant high pharyngo-gastric anastomosis could be the reason for higher PCF/GN rates in our series. Such high anastomosis puts undue pressure on the gastric conduit, could compromise its vascularity and increases the possibility of anastomotic failure and leak. In such situations, the free jejunal graft interposition between the mobilized stomach and the oropharyngeal margin is highly effective with almost no risk of anastomotic leak or fistula in the reported series [35, 36]. It has also been opined that at least third of the mortality after TLPE has been attributable directly or indirectly to failure of pharyngo-gastric anastomosis [31], which probably explains the higher mortality rate in our series. The calamitousness of pharyngo-gastric anastomosis failure compared to failed free flap or axial flap is perhaps because of extravasation or regurgitation of gastric contents like bile or gastric acid which are strong irritants of the soft tissue, compared to less irritant salivary leak seen with other fistulas. Nevertheless, it is worthwhile to reiterate here that the key in reducing the pharyngo-gastric anastomotic failure along with its associated morbidity and mortality rates is the provision of a tension-free pharynx.

Another factor which could have contributed significantly to morbidity in our series is suboptimal nutrition. The perioperative hypoalbuminemia seen in most of our patients reflected the poor nutrition status in them. Low albumin level has been reported to have an association with high morbidity in GP [27]. Moreover, the crucial role of nutrition in wound healing is evidenced by the fact that the correction of albumin levels aided in successful healing of PCF in many of our patients as well as in other studies [29] even without any surgical intervention. As far as the effect of pre-operative radiotherapy is concerned, our results support the conclusion of a large meta-analysis, which showed that the none of the morbidity or mortality related to TLPE with GP were associated with pre-operative radiotherapy [17]. However, the sample size of our cohort did not permit the statistical analyses of clinic-pathological predictors of morbidity and mortality of TLPE with GP, including the effect of radiotherapy. Interestingly, the tracheal necrosis, one of the worrisome complication described with TLPE [14], was not seen in our series. This is probably attributable to the dissection less eversion stripping technique used for transhiatal esophagectomy, in which, the possibility of vascular injury to the tracheal wall is almost negligible [18, 19].

The most striking advantage of TLPE with GP is the functional restoration of swallowing, which is consistently achievable in around 70–80% of the operated cases [17, 19, 26, 28, 30]. The time taken for the restoration of oral intake after GP averages around 15 days as per the published reports [19, 24]. The restoration rate of oral feeds and the average time taken for restoration in our series are at par with literature reports. Additionally, reconstruction of pharyngo-esophagus with GP is associated with significantly lesser stricture or stenosis rates compared to reconstruction by fascio-cutaneous or musculocutaneous free flaps [8, 37]. Overall, early restoration of oral feeding and higher restoration rates, along with fewer stenosis rates make GP one of the most successful reconstruction option as for the swallowing function is concerned. Studies have shown that survival without dysphagia after TLPE is better with GP reconstruction than with any other options like free flaps or axial flaps [17]. The major drawback of GP in our series is that the primary rehabilitation of speech in the form of trachea-gastric puncture was not done. Though patients had alternative means of communication, we could not analyze or quantify the speech-related outcome after TLPE in our patients. The other shortcoming of our study is the follow-up duration. However, due to poor survival in hypopharyngeal cancers, that too, in advanced cases that necessitate TLPE, it is not practically feasible to analyze the long term functional or survival outcomes [17]. The mean follow-up duration, the recurrence rates, and the survival rates observed in our study are closely comparable with the reported rates in the literature [14, 30, 34, 38, 39].

Compared to organ preservation treatment regimes, the survival has been shown to be significantly better after primary radical surgery with or without adjuvant radiotherapy in locally advanced disease of the hypopharynx [4, 6]. As recommended by the guidelines [40], we emphasize that the TLPE should be considered upfront even in primary cases of advanced hypopharyngeal cancers, especially in those with non-functional larynx who are dependent on tracheostomy and feeding tube. Similarly, even in cases of failed chemoradiation or recurrence after previous chemoradiation, the procedure of TLPE with GP should be contemplated in all those cases who otherwise have a good general condition to tolerate this radical procedure. However, since some patients who receive chemoradiation can achieve complete remission a bit later, it is better to delay the salvage surgery until 6 months of completing the therapy [41]. The TLPE with GP in such situations will at least serve as a palliative procedure, if not as a curative one, with the optimal restoration of oral feeding. The benefits of procedure like ‘disease clearance rate’ of 86.6%, ‘mean survival duration’ of 12.1 months, ‘disease-free interval’ of more than 11 months, and ‘oral swallowing restoration rates’ of 77% are at par with any other treatment options offered to these cases of advanced hypopharyngeal malignancy.

Conclusion

In summary, though the current consensus prefers the non-surgical treatment for primary cases of hypopharyngeal cancers, the TLPE with GP can serve better especially in locally advanced cases with dysfunctional larynx, considering the optimal swallowing function and possibly, a better survival outcome. In radio-recurrent/residual cases of locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancers, the procedure of TLPE with GP has the ability to best serve as palliative procedure if not as curative, and it should be considered in all those cases with good performance status. Provision of tension free stomach for pharyngo-gastric anastomosis and optimization of nutrition status are some of the measures that are likely to reduce the procedure related complications. Our modification of upward eversion stripping technique for transhiatal esophagectomy could further lessen the complications of TLPE.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

Appropriate permission from the institute ethical committee obtained.

Informed Consent

Not applicable, as it is a retrospective study. However, IEC approval obtained for the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hall SF, Groome PA, Irish J, O’Sullivan B. The natural history of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1362–1371. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318173dc4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y-J, Lee R. Surgery versus radiotherapy for locally advanced hypopharyngeal cancer in the contemporary era: a population-based study. Cancer Med. 2018;7:5889–5900. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newman JR, Connolly TM, Illing EA, Kilgore ML, Locher JL, Carroll WR. Survival trends in hypopharyngeal cancer: a population-based review. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:624–629. doi: 10.1002/lary.24915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petersen JF, Timmermans AJ, van Dijk BAC, Overbeek LIH, Smit LA, Hilgers FJM, et al. Trends in treatment, incidence and survival of hypopharynx cancer: a 20-year population-based study in the Netherlands. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2018;275:181–189. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4766-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habib A. Management of advanced hypopharyngeal carcinoma: systematic review of survival following surgical and non-surgical treatments. J Laryngol Otol. 2018;132:385–400. doi: 10.1017/S0022215118000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo P, Chen MM, Decker RH, Yarbrough WG, Judson BL. Hypopharyngeal cancer incidence, treatment, and survival: temporal trends in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:2064–2069. doi: 10.1002/lary.24651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen WF, Chang K-P, Chen C-H, Shyu VB-H, Kao H-K. Outcomes of anterolateral thigh flap reconstruction for salvage laryngopharyngectomy for hypopharyngeal cancer after concurrent chemoradiotherapy. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan NC, Lin P-Y, Kuo P-J, Tsai Y-T, Chen Y-C, Nguyen KT, et al. An objective comparison regarding rate of fistula and stricture among anterolateral thigh, radial forearm, and jejunal free tissue transfers in circumferential pharyngo-esophageal reconstruction. Microsurgery. 2015;35:345–349. doi: 10.1002/micr.22359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pegan A, Rašić I, Košec A, Solter D, Vagić D, Bedeković V, et al. Type II hypopharyngeal defect reconstruction—a single institution experience. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;57:673–680. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.04.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei WI. The dilemma of treating hypopharyngeal carcinoma: more or less: hayes Martin lecture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:229–232. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosoya Y, Sarukawa S, Matsumoto S, Zuiki T, Hyodo M, Abe K, et al. Esophagectomy and gastric pull-up in patients with previous free jejunal transfer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:647–649. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung S-H, Tsai M-C, Liu T-C, Lin H-C, Chung S-D. Routine endoscopy for esophageal cancer is suggestive for patients with oral, oropharyngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morita M, Saeki H, Ito S, Ikeda K, Yamashita N, Ando K, et al. Technical improvement of total pharyngo-laryngo-esophagectomy for esophageal cancer and head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1671–1677. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Homma A, Nakamaru Y, Hatakeyama H, Mizumachi T, Kano S, Furusawa J, et al. Early and long-term morbidity after minimally invasive total laryngo-pharyngo-esophagectomy with gastric pull-up reconstruction via thoracoscopy, laparoscopy and cervical incision. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2015;272:3551–3556. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3420-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwatsubo T, Ishihara R, Morishima T, Maekawa A, Nakagawa K, Arao M, et al. Impact of age at diagnosis of head and neck cancer on incidence of metachronous cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:3. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-5231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei WI, Lam LK, Yuen PW, Wong J. Current status of pharyngolaryngo-esophagectomy and pharyngogastric anastomosis. Head Neck. 1998;20:240–244. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199805)20:3<240::AID-HED9>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butskiy O, Rahmanian R, White RA, Durham S, Anderson DW, Prisman E. Revisiting the gastric pull-up for pharyngoesophageal reconstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mortality and morbidity. J Surg Oncol. 2016;114:907–914. doi: 10.1002/jso.24477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajan R, Rajan R, Rajan N, Pai US. Gastric pull-up by eversion stripping of oesophagus. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:1021–1024. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100125150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shenoy RK, Pai SU, Rajan N. Stomach as a conduit for esophagus—a study of 105 cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1996;15:52–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Disa JJ, Pusic AL, Hidalgo DA, Cordeiro PG. Microvascular reconstruction of the hypopharynx: defect classification, treatment algorithm, and functional outcome based on 165 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:652–660. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041987.53831.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Evans KF, Mardini S, Salgado CJ, Chen H-C. Esophagus and hypopharyngeal reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2010;24:219–226. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1255339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe M, Baba Y, Yoshida N, Ishimoto T, Sakaguchi H, Kawasuji M, et al. Modified gastric pull-up reconstructions following pharyngolaryngectomy with total esophagectomy. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:255–261. doi: 10.1111/dote.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sallum RA, Coimbra FJF, Herman P, Montagnini AL, Machado MAC. Modified pharyngogastrostomy by a stapler technique. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:540–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huscher C, Mingoli A, Mereu A, Sgarzini G. Pharyngolaryngo-esophagectomy with laparoscopic gastric pull-up: a reappraisal for the pharyngoesophageal junction cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:2980. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akiyama H, Hiyama M, Miyazono H. Total esophageal reconstruction after extraction of the esophagus. Ann Surg. 1975;182:547–552. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197511000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marion Y, Lebreton G, Brévart C, Sarcher T, Alves A, Babin E. Gastric pull-up reconstruction after treatment for advanced hypopharyngeal and cervical esophageal cancer. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2016;133:397–400. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi P, Nair S, Chaturvedi P, Chaukar D, Pai P, Agarwal JP, et al. Hypopharyngeal cancers requiring reconstruction: a single institute experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;65:135–139. doi: 10.1007/s12070-013-0627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dudhat SB, Mistry RC, Fakih AR. Complications following gastric transposition after total laryngo-pharyngectomy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25:82–85. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1998.0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuangba H, Jingwu S, Yinfeng W, Yanming H, Qiuping L, Xianguang L, et al. Complication following gastric pull-up reconstruction for advanced hypopharyngeal or cervical esophageal carcinoma: a 20-year review in a Chinese institute. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32:275–278. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Deng T, Li C, Peng L, Li Q, Zhu G, et al. Reconstruction of hypopharyngeal and esophageal defects using a gastric tube after total esophagectomy and pharyngolaryngectomy. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2016;78:208–215. doi: 10.1159/000446805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butskiy O, Anderson DW, Prisman E. Management algorithm for failed gastric pull up reconstruction of laryngopharyngectomy defects: case report and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45:41. doi: 10.1186/s40463-016-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keereweer S, de Wilt JHW, Sewnaik A, Meeuwis CA, Tilanus HW, Kerrebijn JDF. Early and long-term morbidity after total laryngopharyngectomy. Eur Arch Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2010;267:1437–1444. doi: 10.1007/s00405-010-1244-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sayles M, Grant DG. Preventing pharyngo-cutaneous fistula in total laryngectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1150–1163. doi: 10.1002/lary.24448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Triboulet JP, Mariette C, Chevalier D, Amrouni H. Surgical management of carcinoma of the hypopharynx and cervical esophagus: analysis of 209 cases. Arch Surg Chic Ill. 2001;136:1164–1170. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.10.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyata H, Sugimura K, Motoori M, Fujiwara Y, Omori T, Mun M, et al. Clinical assessment of reconstruction involving gastric pull-up combined with free jejunal graft after total pharyngolaryngoesophagectomy. World J Surg. 2017;41:2329–2336. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-3948-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni S, Zhu Y, Li D, Li Z, Wu Y, Xu Z, et al. Gastric pull-up reconstruction combined with free jejunal transfer (FJT) following total pharyngolaryngo-oesophagectomy (PLE) Int J Surg Lond Engl. 2015;18:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark JR, Gilbert R, Irish J, Brown D, Neligan P, Gullane PJ. Morbidity after flap reconstruction of hypopharyngeal defects. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:173–181. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000191459.40059.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sreehariprasad AV, Krishnappa R, Chikaraddi BS, Veerendrakumar K. Gastric pull up reconstruction after pharyngo laryngo esophagectomy for advanced hypopharyngeal cancer. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2012;3:4–7. doi: 10.1007/s13193-012-0135-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bova R, Goh R, Poulson M, Coman WB. Total pharyngolaryngectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx: a review. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:864–869. doi: 10.1097/01.MLG.0000158348.38763.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pracy P, Loughran S, Good J, Parmar S, Goranova R. Hypopharyngeal cancer: United Kingdom national multidisciplinary guidelines. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:S104–S110. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116000529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chun S-J, Keam B, Heo DS, Kim KH, Sung M-W, Chung E-J, et al. Optimal timing for salvage surgery after definitive radiotherapy in hypopharyngeal cancer. Radiat Oncol J. 2018;36:192–199. doi: 10.3857/roj.2018.00311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]