Abstract

Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) also known as vanishing bone disease is an idiopathic and rare condition characterized by gross and progressive bone loss along with excessive growth of vascular and lymphatic tissue. Very little is known about the pathogenesis of GSD, which makes the diagnosis challenging and often diagnosed by elimination. We report a case of GSD in a 41-year-old male patient. He presented with bone pain and initial imaging showed widespread osteolytic lesions in the cervical and mid thoracic spine, ribs, sternum, clavicles, scapula, and humerus. Two percutaneous bone biopsies were performed, followed by an open spine biopsy of the lumber 2 spinous process for histological examination. Unfortunately, no diagnosis was reached. Although, he was treated symptomatically, he kept enduring pain and presented again after 7 months. His laboratory values were out of the normal range which prompted thorough investigations. New imaging and bone biopsy revealed multiple osteolytic lesions and vascular lesion with cavernous morphology respectively. GSD was diagnosed after ruling out a neoplastic process and confirming the cavernous morphology with immunohistochemical stain. He was treated symptomatically with immunomodulators, bisphosphonates, and supplements. Patient was counseled to see the specialist regularly. This case will help to increase familiarity and shed insights in the diagnosis of GSD.

Keywords: Vanishing bone disease, Osteolytic lesion, Bone biopsy, Spongious bone

Introduction

Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) or vanishing bone disease is a rare entity of unknown etiology, characterized by destruction of bony matrix and proliferation of vascular structures, resulting in disruption and dissolution of bone as well as generalized lymphatic proliferation. Although the pathophysiology is not well understood, in recent years, it is found that genetic mutation in phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway as well as somatic mutation in NRAS gene in lymphatic endothelium can be responsible for generalized lymphadenopathy in GSD. Investigations are fairly unremarkable except for the radiographs that usually show generalized osteolytic lesions and biopsy that shows absence of neoplastic lesions and presence of vascular lesion with cavernous morphology. Management is supportive. We present here a case of middle aged man with several symptoms that finally resulted in GSD. We treated the patient symptomatically; the patient is partially recovered and is on regular follow-up.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old male patient presented to the rheumatologist clinic, on August 2020, with complaints of lower back pain. The patient reported to have had back and chest pains, a feeling of general malaise and restricted walking movements during the last 2 years, but the pain had intensified in the last months. His medical history was unremarkable, without any known trauma and his family history was negative for bone diseases. On physical examination, he showed painful movement during the flexion and extension of the neck, spine, elbows, knees, and hands and during the internal and external rotation of the arms. Neither edema nor redness was present. He had positive Lasegue and Minell sign, which suggested pathological changes on the level of L4 and sacro-ileal joint. His complete blood count and blood chemistry panel was normal, except for low vitamin D level. During further investigations, multiple osteolytic bone lesions affecting the vertebral bodies were found together with a collapsed L5 vertebrae. It was initially suspected a diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Two percutaneous bone biopsies were performed. The biopsied material showed no neoplastic changes with the presence of all 3 hematopoietic lines (myeloid, erythroid, and megakaryocytic) with normal morphology and distribution. The myelogram was also normal. He was then admitted for an open spine biopsy, with the removal of the L2 spinous process for histologic examinations, which also failed to reach a diagnosis. He was released from the clinic being given medications for symptomatic treatment of his disease. Six months later, his symptoms persisted and he presented again to the clinic for follow-up. His complete blood count was normal, no increase in inflammation markers. His blood chemistry panel showed normal values. The levels of PTH, serum calcium, phosphorus, and calcitonin were normal. A sample of his bone tissue was again sent for e second evaluation. The specimens contained bone tissue that consisted of cortical and spongious bone. The spongious bone was considerably restructured, the trabecula were configured irregularly. In the fibrosed medullary space, there were numerous sinusoidally configured, thin-walled vessels, which were lined by inconspicuous flat epithelia and contained erythrocytes. Macrophages were transformed into foamy cells. There was no inflammatory cell infiltration, no nuclear and cell atypia. On the accompanying image, were seen multiple osteolytic lesions in the entire cervical spine and middle thoracic spine, in numerous ribs, sternum and scapula on both sides as well as clavicles on both sides and in the humerus. Overall, the pathologist concluded that it was a nonspecific vascular proliferation characterized by thin wall channels. In correlation with the imaging, the findings suggested a cystic skeletal angiomatosis with extensive manifestations in the spinal vertebrae, in the ribs, sternum, extremities and possibly also the base of the skull. (Fig. 1) A neoplastic process war ruled out. After performing immunohistochemical examinations, he continued to see a vascular lesion with a cavernous morphology; in connection with the imaging, the findings still suggested a cystic skeletal angiomatosis.

Fig. 1.

(A-D) Computed tomography examination of bone structures, from the neck to the distal femoral metaphysis, presents numerous osteolytic lesions, with bone destruction, with the presence of solid tissue within the osteolytic lesions, where most are significantly imbibed with i.v. contrast. Solid vertebral masses with oval or spherical shape, with external expansion in the spinal canal, with narrowing of the spinal canal and lateral recesses (neuro-foraminal spaces). Compared to the examinations done 1 year ago, there was a slight increase in size. Such lesions were present indiscriminately, as in the vertebral, sternal, rib, pelvic bones and both proximal femurs. Right femur showed massive osteolysis, where osteosynthetic metal rod, and hyperdense mass were observed in the bone defect (implanted synthetic material).

A diagnosis of GSD was made based on combination with histological, radiological, and clinical features (Fig. 2).

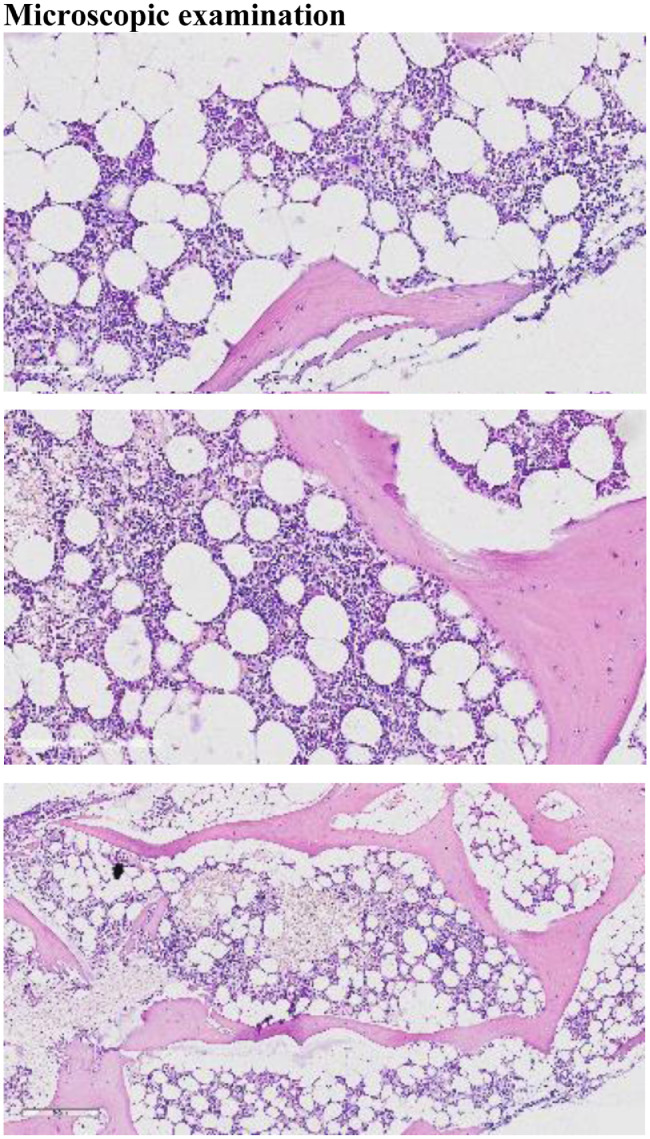

Fig. 2.

(A-C) Microscopic examination of the H&E-stained sections showed normocellular bone marrow for age, with presence of maturing trilineage hematopoiesis. Medium power view showed numerous thin-walled capillary-sized vascular channels, which were lined by inconspicuous flat epithelia and contained erythrocytes. No cellular atypia were noted ruling out malignancy. Histopathological examination of the medullary cavity suggested angiomatous tissue.

The patient was given symptomatic treatments (thalidomide, Xarelto, decortin, ibadronate, allopurinol, calcium, vitamin C, vitamin K, and ibuprofen), with the advice of continuous check-ups with the specialist.

Discussion

Gorham-Stout disease or vanishing bone disease, is a rare pathological entity, with only a few hundred cases reported in literature. It mainly affects the maxillofacial region, the upper extremities, the clavicle, ribs, vertebrae, the pelvis, as well as cranial bones [1], [2], [3]. It is characterized by massive osteolysis and osseous resorption, associated with an abnormal non-neoplastic proliferation of vascular and lymphatic tissue [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

The condition arises sporadically. A familial, inherited pattern, as well as environmental predisposing factors, has not been established [2].

To date, the pathogenesis of the disorder remains to be elucidated, however several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the pathological mechanisms involved in the bone resorption and neoangiogenesis processes. Gorham and Stout, who were the first to delineate it as a distinct disorder, hypothesized that a preceding traumatic event triggered the osteolytic process, which was subsequently aided by local factors such as changes in the pH, active hyperemia and changes in mechanical forces [3,4].

Nevertheless, recent research suggests that several elements including mononuclear phagocytes, multinuclear osteoclasts and the vascular endothelium are involved in the induction of massive osteolysis and development of a new network of vascular and lymphatic vessels. Moreover, studies show that precursors of these cells are more sensitive to humoral factors such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), promoting cell proliferation that leads to an increased number of circulating osteoclasts, increased osteoclastic activity and bone resorption, documented by elevated levels of CTX-1 (a marker of osteoclastic activity), in affected patients [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]. It has been noted that phagocytic and lymphatic endothelial cells from these lesions produce elevated levels of osteoclastogenic and angiogenic substances, promoting osteoclast proliferation and further contributing to the bone resorption [2], [3], [4], [5].

Growth factors associated with lymphangiogenesis such as PDGF-BB and VEGF have been implicated in pathogenesis of Gorham-Stout disease, however additional studies are needed to shed light on their role [2,5].

Incidentally, there are theories that dysregulations in the production of calcitonin, a hormone synthesized by parafollicular cells (C-cells) in the thyroid gland with anti-osteoclastic activity, may play a role [2], [3], [4].

Histopathological examination revealed that the lesions were characterized by wide, capillary-like vessels with an abnormal slow flow and changes in the adjacent soft tissue, likely due to the extension of the lymphangiogenesis into the surrounding tissues. Absence of cellular atypia was noted. It has been postulated that these structural qualities promote local hypoxia, that leads to an overproduction of hydrolytic enzymes, possibly instigating bone resorption [3,4].

Conclusion

We report a case of GSD, where the disease was not diagnosed in the initial stage. Due to its rarity and the controversy behind its etiology, GSD is often diagnosed by elimination and treatment is still in research, including medication therapy, radiation therapy, surgery and targeted therapies. This case emphasizes the need of extensive research on GSD so that we can make an accurate diagnosis at an earlier stage.

Patient consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the parent of the patient to publish this paper.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lala S, Mulliken J B, Alomari A I, Fishman S J, Kozakewich H P, et al. Gorham-Stout disease and generalized lymphatic anomaly—clinical, radiologic, and histologic differentiation. Skelet Radiol. 2013;42(7):917–924. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1565-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolaou VS, Chytas D, Korres D, Efstathopoulos N. Vanishing bone disease (Gorham-Stout syndrome): a review of a rare entity. World J Orthop. 2014;5(5):694–698. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i5.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiran D N, Anupama A. Vanishing bone disease: a review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69(1):199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saify FY, Gosavi SR. Gorham's disease: a diagnostic challenge. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18(3):411–414. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.151333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger MT, Garg N, Olsen BR. Viewpoints on vessels and vanishing bones in Gorham-Stout disease. Bone. 2014;63:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang W, Wang H, Zhou X, Li X, Sun W, et al. Lymphatic endothelial cells produce M-CSF, causing massive bone loss in mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(5):939–950. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]