Abstract

Sodium benzoate (SB), the sodium salt of benzoic acid, is widely used as a preservative in foods and drinks. The toxicity of SB to the human body attracted people’s attention due to the excessive use of preservatives and the increased consumption of processed and fast foods in modern society. The SB can inhibit the growth of bacteria, fungi, and yeast. However, less is known of the effect of SB on host commensal microbial community compositions and their functions. In this study, we investigated the effect of SB on the growth and development of Drosophila melanogaster larvae and whether SB affects the commensal microbial compositions and functions. We also attempted to clarify the interaction between SB, commensal microbiota and host development by detecting the response of commensal microbiota after the intervention. The results show that SB significantly retarded the development of D. melanogaster larvae, shortened the life span, and changed the commensal microbial community. In addition, SB changed the transcription level of endocrine coding genes such as ERR and DmJHAMT. These results indicate that the slow down in D. melanogaster larvae developmental timing and shortened life span of adult flies caused by SB intake may result from the changes in endocrine hormone levels and commensal microbiota. This study provided experimental data that indicate SB could affect host growth and development of D. melanogaster through altering endocrine hormone levels and commensal microbial composition.

Keywords: sodium benzoate, Drosophila melanogaster, development, commensal microbiota, endocrine hormone

Introduction

Sodium benzoate (SB) is the sodium salt of benzoic acid, represented by the chemical formula C7H5O2Na. It is widely used in the preservation of foods and drinks, such as jams, jellies, margarine, pickles, salads, sauces, vinegar, carbonated drinks, and fruit juices. SB is considered a “generally regarded as safe” compound by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Food and Drug Administration [FDA], 2017). FDA has limited the amount of SB added to less than 0.1% (1,000 ppm) in food preservation (Lennerz et al., 2015). The World Health Organization’s official publication allows SB as an animal food additive for up to 0.1% (Lennerz et al., 2015). However, the increased consumption of processed and fast foods in modern society has led to excessive use of preservatives including SB and raised safety concerns for human physical health. The calls for the evaluation of SB safety and the potential harm of additive overuse are increasing.

The effects of SB on human and animal physical health are protective-toxic dual sides. SB was reported to be beneficial to many diseases. SB was highly beneficial for treating metabolic disorders, such as urea cycle disorders, and other diseases with hyperammonemia (Husson et al., 2016; NeSmith et al., 2016; Piper and Piper, 2017). Besides, SB was also found to be of potential therapeutic value for liver failure (De Las Heras et al., 2017), multiple sclerosis (Kundu et al., 2016), schizophrenia (Lane et al., 2013; Matsuura et al., 2015), early stage Alzheimer’s disease (Lin et al., 2014), Parkinson’s disease (Khasnavis and Pahan, 2012), and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (Lin et al., 2020). However, Misel et al. (2013) showed that the significant high-dose dependence of SB may result in damage to the kidney, revealing the harmful effects of high-dose SB additions.

Many researchers have conducted experiments to test the toxicity of SB using animal models. SB was considered genotoxic, clastogenic, and neurotoxic, affecting cell cycle and DNA structure via intercalation (Linke et al., 2018). Mammals with chronic exposure to SB suffered from reduced food intake and growth (Nair, 2001). El-Shennawy et al. (2020) showed that SB significantly altered the reproductivity of male rats, as shown by the weight loss of reproductive organs, decreased sperm count and motility, and increased percentage of abnormal sperms. Consistent results were found in the study of Jewo et al. (2020), whereby the SB intake significantly reduced the total sperm count, and germ cell loss and sloughing of germinal epithelium were also found. Gaur et al. (2018) reported that SB changed developmental, morphological, biochemical, and behavioral features in developing zebrafish larva, including delayed hatching, pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, tail bending, oxidative stress, and anxiety-like behavior. In addition, SB induced liver histological alterations; increased lipid peroxidation and glutathione content; and declined catalase activity in the kidney tissues (Khodaei et al., 2019).

Gut microbiota is often referred to as a “superorganism” due to its vast number in the host body (Gill et al., 2006; Thursby and Juge, 2017). Gut microbiota draws dramatic attention in recent years owing to their extensive interactions with the host. The microbiota provides many beneficial effects on the health of the host, such as strengthening the gut integrity (Thursby and Juge, 2017), assisting the energy harvest (Murphy et al., 2010), protecting against pathogens (Bäumler and Sperandio, 2016), and regulating the host immunity (Gensollen et al., 2016). The antimicrobial effect has been well explored in the food and drink industries (Karabay et al., 2006; Zhao and Doyle, 2006). Stanojevic et al. (2009) found that the combination of sodium nitrite and SB synergistic inhibited 40% of Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus mucoides, and Candida albicans. Nevertheless, the effect of SB on commensal gut microbial community compositions and functions of the host remains scarce.

Drosophila melanogaster (D. melanogaster) has the advantages of easy feeding, short life cycle, low maintenance cost, etc. In addition, it has conserved metabolism pathways with human. Therefore, it is considered as an ideal animal model in scientific studies. In this study, we investigated the effect of SB on the growth and development of D. melanogaster larvae, and whether SB affects the commensal microbial compositions and functions. We also aim to clarify the interaction between SB, commensal microbiota and host development by analyzing the response of commensal microbiota in flies fed with SB. The results show that 2,000 ppm of SB or higher significantly retarded the development of D. melanogaster larvae, shortened the life span, and altered the commensal microbial community.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila melanogaster Husbandry

The D. melanogaster stock used in this study was Canton-S-iso3A (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center #9516, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, United States). The flies were raised on a standard yeast-sucrose-cornmeal diet containing 25 g yeast, 40 g sucrose, 42.4 g maltose, 66.825 g cornmeal, 9.18 g soybean meal, 6 g agar, 0.5 g SB, 0.25 g nipagin, and 6.875 ml propionic acid per liter. The SB (Aladdin, AR, 99%) treatment media comprised a standard diet supplemented with SB at either 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, or 5,000 ppm, respectively.

Mated females were transferred on an appropriate media for embryos laying, followed by transferring to SB treatment media. Fresh food was prepared every week and stored at 4°C to avoid desiccation. All flies were maintained under constant temperature (25°C) and humidity (65%) with a 12 h light-dark cycle.

Developmental Timing Measurement

The larval-pupal and pupal-adult metamorphosis timing of individuals raised in different SB treatments was quantified by counting the number of pupae and adults emerging over time.

Adult weight was estimated using 1-day-old adults. For each condition, the weight of a pool of ten adult individuals was weighed using a precision balance [Mettler Toledo, MS105DU (Zurich, Switzerland)]. Each graph represents the mean of at least six biological replicates, including at least 10 individuals each.

Survival Analysis

Two SB treatments (0 and 2,000 ppm) were selected to conduct survival analysis. Adult flies hatched from larvae growing on treatment media containing 0 and 2,000 ppm of SB were transferred to treatment media with 0 ppm and 2,000 ppm of SB and tested in the following four combinations, respectively. The group 0 + 0 means that survival analysis was tested on 0 ppm of SB media using adults hatched from larvae growing on 0 ppm of SB. The group 0 + 2000 means that survival analysis was tested on 2,000 ppm of SB media using adults hatched from larvae growing on 0 ppm of SB. The group 2000 + 0 means that survival analysis was tested on 0 ppm of SB media using adults hatched from larvae growing on 2,000 ppm of SB. The group 2000 + 2000 means that survival analysis was tested on 2,000 ppm of SB media using adults hatched from larvae growing on 2,000 ppm of SB.

Flies within 8 h of emergence were separated into single-sex groups (males and females) under light CO2 anesthesia. For both the male and female groups, 10 vials each containing 20 flies were used for the survival analysis of each treatment. Survival curves were determined by counting dead flies every 2–3 days, and the media was replaced every 5 days.

16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Analysis

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Adult flies (from both the SB fed and SB unfed groups) were collected and sequentially rinsed in 50% (v/v) bleach and 70% ethanol, after which they were washed extensively with phosphate buffer solution (PBS) before dissection. Guts from 15 flies in each sample were dissected in sterile PBS using sterile forceps, and the trachea, malpighian tubules, and crop were then carefully removed. Guts were collected in PBS on ice and then homogenized using a tissue grinder (Tiangen, OSE-Y20, Beijing, China) with a pestle (Tiangen, OSE-Y001, Beijing, China). Homogenized samples were stored at −80°C, and frozen gut samples were thawed at 37°C for 45 min in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and transferred to a 2 ml tube containing 600 μl LWA (BioBase, M2012-01, Chengdu, China). The supernatant was transferred to a 2 ml tube containing 30 μl BioBase Tissue beads (BioBase, M2012-01, Chengdu, China). After elution with WB and SPW buffers (BioBase, M2012-01, Chengdu, China), the beads were air-dried at room temperature. Finally, DNA was eluted using EB buffer (BioBase, M2012-01, Chengdu, China).

Illumina NovaSeq Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

The 16S rRNA genes of V3–V4 regions were amplified using specific primers [341F (5′-CCTAYGGGRBGCASCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACNNGGGTATCTAAT-3′)] with the barcode. PCR products were mixed in equidensity ratios, and then, the mixture of PCR products was purified with Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany).

Sequencing libraries were generated using TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, United States) following the manufacturer’s recommendations, and index codes were added. The library quality was assessed using the Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, United States). At last, the qualified library was sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform, and 250 bp paired-end reads were generated.

The bioinformatics analysis was conducted by following the “Atacama soil microbiome tutorial” of Qiime2 docs along with customized program scripts.1 De-multiplexed sequences from each sample were quality filtered and trimmed, de-noised, and merged, and then, the chimeric sequences were identified and removed using the QIIME2 dada2 plugin to obtain the feature table of amplicon sequence variant (ASV) (Callahan et al., 2016). The taxonomy table was generated by using the QIIME2 feature-classifier plugin aligning ASV sequences to a pretrained GREENGENES 13_8 99% database (Bokulich et al., 2018). Diversity metrics were calculated using the core-diversity plugin within QIIME2. Feature level alpha diversity indices, such as observed OTUs, Chao1 richness estimator, Shannon diversity index, and Simpson diversity index, were calculated to estimate the microbial diversity within an individual sample. Beta diversity distance measurements were performed to investigate the structural variation of microbial communities across samples and visualized via principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) (Vázquez-Baeza et al., 2013). Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) was introduced as a supervised model to reveal the commensal microbiota variation among groups using the “plsda” function in the R package “mixOmics” (Rohart et al., 2017). The potential KEGG Ortholog functional profiles of the commensal microbial communities were predicted with Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) (Langille et al., 2013). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) analysis was conducted by the LEfSe module on the online galaxy website.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR to Assess Related Gene Expression of Drosophila melanogaster

Adult flies that emerged from SB media (0 and 2,000 ppm) within 8 h were selected. Whole bodies (15–20 flies per sample) were homogenized in the translation lookaside buffer (TLB) (BioBase, N1002-01) using a tissue grinder (Tiangen, OSE-Y20) with a pestle (Tiangen, OSE-Y001), and then, the total RNA was extracted following the user guidance of the RNA Extraction Kit (BioBase, N1002). RNA concentrations were measured using the Nanodrop 2000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop2000c; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), and 1 μg of total RNA per sample was reverse-transcribed using the FastKing First-Strand Synthesis System (Thermo, #K1641). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using a Roche 480 II real-time PCR cycler (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) with 2 × Q3 QuantiNova SYBR Green II PCR Master Mix (TOLOBIO, 22204-1). The final mRNA expression fold change relative to the control was normalized to rp49. Primer sequences for qRT-PCR are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical Analysis

Development timing, survival curves, and Mantel-Cox tests were analyzed by the GraphPad Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, United States). For other comparisons between two samples, two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used. For multiple comparisons, a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test was used. Graphs without special illustrations show the mean with error bars of 1 SD. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks, where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Results

Developmental Timing Measurement

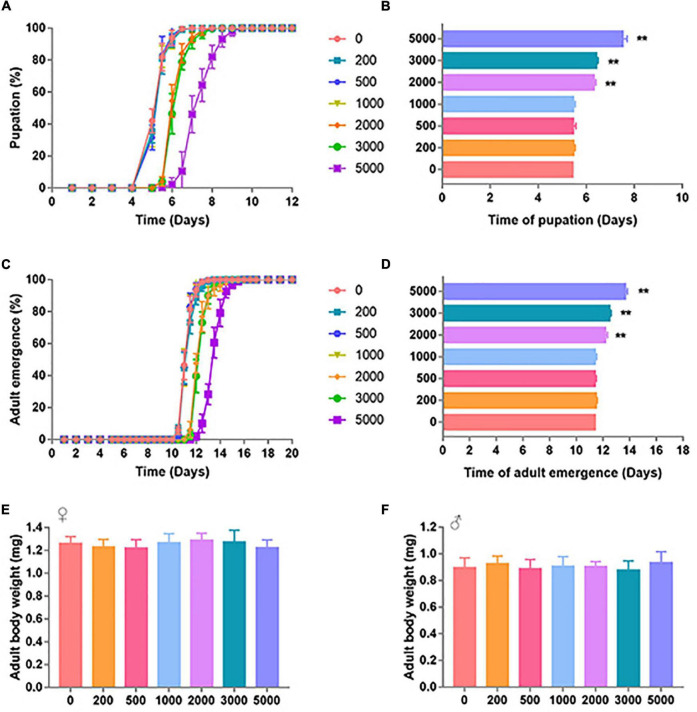

The effect of SB on D. melanogaster development was characterized by pupation time, adult emergence time, and body weight. The developmental process of D. melanogaster was significantly retarded by high dosages of SB (Figure 1). Low dosages (0–1,000 ppm) of SB had no significant effect on the time of pupation (Figures 1A,B), whereas higher SB dosages (between 2,000 and 5,000 ppm) showed a longer time of pupation (Figures 1A,B). Consistent with the change of pupation time, low addition (0–1,000 ppm) of SB had no significant effect on the time of adult emergence (Figures 1C,D). SB addition between 2,000 and 5,000 ppm showed a longer time of adult emergence (Figures 1C,D). However, both male and female flies fed with SB showed no significant change in body weight (Figures 1E,F).

FIGURE 1.

Development timing of SB-supplemented flies. (A) Pupation time of flies fed with SB. (B) Mean time of the pupation of flies fed with SB at 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 5,000 ppm. (C) Adult emergence time of flies fed with SB. (D) Mean time of the adult emergence time of flies fed with 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB. (E) Adult body weight of females fed with 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB. (F) Adult body weight of males fed with 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB. **p < 0.01.

Survival Analysis

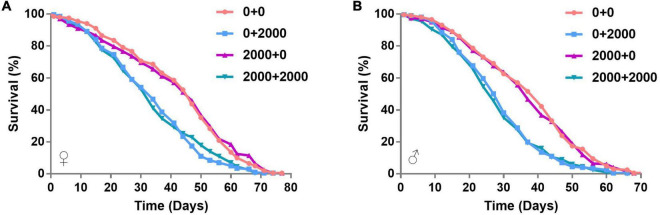

To find out the effect of SB on the life span of adult flies, we further conducted the survival analysis. The groups of 0 + 0 and 2000 + 0 were set to explore whether early life (larvae)-only exposed to SB could affect adult life span. Mean survival rates of females were 52.88 and 52.22% in 0 + 0 and 2000 + 0 groups, respectively (p = 0.6184) (Table 1). Mean survival rates of males were 50.07 and 47.42% in 0 + 0 and 2000 + 0 groups, respectively (p = 0.6793) (Table 1). These results indicated that the treatment of SB in the larval stage-only did not affect adult life spans in both female and male groups (Figures 2A,B and Table 1). Similar results were found by comparing the mean life span of 0 + 2000 with 2000 + 2000 groups.

TABLE 1.

Statistics for survival curves.

| Total no. of flies | Mean (% change) | Median (% change) | Log-rank | ||

| Female | |||||

| 0 + 0 | 0 + 2000 | 200 | 52.88 | 60.95 | p < 0.0001 |

| 2000 + 0 | p = 0.6184 | ||||

| 2000 + 2000 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| 0 + 2000 | 2000 + 0 | 200 | 44.13 (−8.75%) | 38.81 (−22.14%) | p < 0.0001 |

| 2000 + 2000 | p = 0.7802 | ||||

| 2000 + 0 | 2000 + 2000 | 200 | 52.22 (−0.66%) | 59.20 (−1.74%) | p < 0.0001 |

| 2000 + 2000 | 200 | 45.96 (−6.92%) | 38.06 (−22.87%) | − | |

| Male | |||||

| 0 + 0 | 0 + 2000 | 200 | 50.27 | 54.48 | p < 0.0001 |

| 2000 + 0 | p = 0.6793 | ||||

| 2000 + 2000 | p < 0.0001 | ||||

| 0 + 2000 | 2000 + 0 | 200 | 43.84 (−6.42%) | 33.58 (−20.90%) | p < 0.0001 |

| 2000 + 2000 | p = 0.6220 | ||||

| 2000 + 0 | 2000 + 2000 | 200 | 47.42 (−2.85%) | 46.77 (−7.71%) | p < 0.0001 |

| 2000 + 2000 | 200 | 44.49 (−5.77%) | 35.32 (−19.15%) | − |

Cohort sizes, mean and median life spans, percentage changes, and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests for survival curves in this study.

FIGURE 2.

Survival curves of flies fed with SB. (A) Female files fed with 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB. (B) Male files fed with 0, 200, 500, 1,000, 2,000, 3,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB.

The groups of 0 + 0 and 0 + 2000 were set to explore whether continuous adult exposure to SB could affect the adult life span. Mean survival rates of females were 52.88 and 44.13% in 0 + 0 and 0 + 2000 groups, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). Mean survival rates of males were 50.07 and 43.84% in 0 + 0 and 0 + 2000 groups, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Table 1). These results demonstrate that the treatment of SB in adult stage-only significantly shortened the life spans in both female and male groups (Figures 2A,B and Table 1). Similar results were found by comparing the mean life span of 2000 + 0 with 2000 + 2000 groups.

The above results indicate that SB treated in the larval stage-only would not change the life span, whereas SB treated in the adult stage would shorten the life span.

Commensal Microbiota

Sodium Benzoate Changed the Commensal Microbial Diversity of Flies

To investigate the effect of SB on commensal microbiota, we further conducted 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing. A total of 1,606,655 high-quality sequences were generated via sequencing, and a 99% identity cutoff was used to define each OTU by QIIME2 dada2. The OTU numbers ranged from 789 to 1,122 for each group. The 16S sequence data generated in this study were submitted to the NCBI SRA database (accession number PRJNA774185).

A large number abundance of Wolbachia was found in the sequencing data. This indicated that some Wolbachia contamination may occur. Wolbachia is an intracellular endosymbiont mostly found in the reproductive tract of Drosophila. Thus, to avoid the effect of Wolbachia and to get a more accurate effect of SB on the commensal gut microbiota of Drosophila, we conducted the microbial analysis based on the Wolbachia-excluded data in the “Results” section (Figures 4–7 and Tables 2, 3). In addition, to draw more accurate conclusions, the analysis of Wolbachia-included data was also carried out (Supplementary Figures 1–4 and Supplementary Tables 2, 3).

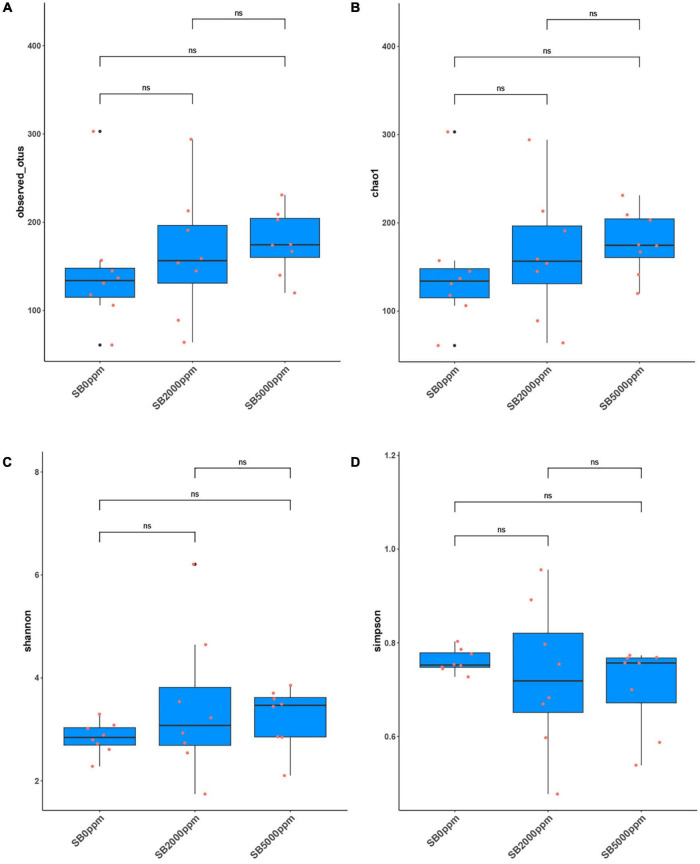

FIGURE 4.

Alpha diversity of flies’ commensal microbiota fed with SB at the genus level of Wolbachia-excluded data. (A) Observed OTUs. (B) Chao1. (C) Shannon. (D) Simpson.

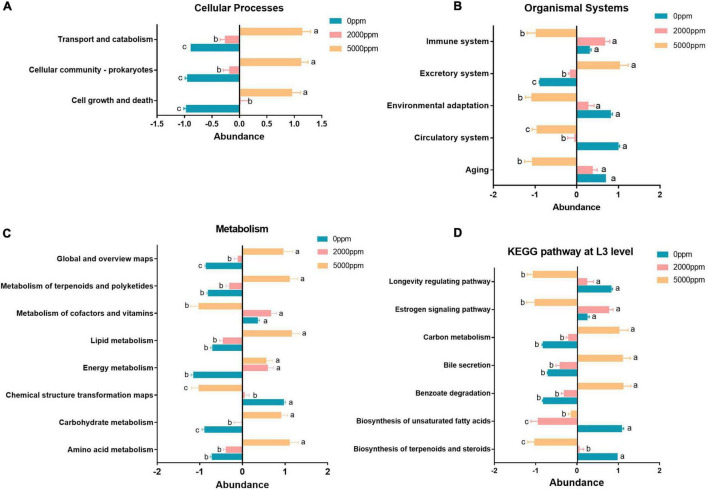

FIGURE 7.

Significant pathway (ANOVA) of the commensal microbial function of Wolbachia-excluded data. (A) Cellular processes. (B) Organismal systems. (C) Metabolism. (D) KEGG pathway at L3 level. The same letters (a, b, c) next to the bars indicate that there is a significant difference between the two groups and, otherwise, no significant difference between the two groups.

TABLE 2.

PERMANOVA of microbiota based on Bray–Curtis distance of Wolbachia-excluded data.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Sample size | Permutations | pseudo-F | P-value |

| SB0 ppm | SB2000 ppm | 16 | 999 | 12.117 | 0.002 |

| SB0 ppm | SB5000 ppm | 16 | 999 | 14.759 | 0.001 |

| SB2000 ppm | SB5000 ppm | 16 | 999 | 1.205 | 0.323 |

TABLE 3.

PERMANOVA of microbial function based on Bray–Curtis distance of Wolbachia-excluded data.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Sample size | Permutations | pseudo-F | P-value |

| SB0 ppm | SB2000 ppm | 16 | 999 | 72.177 | 0.001 |

| SB0 ppm | SB5000 ppm | 16 | 999 | 32.819 | 0.001 |

| SB2000 ppm | SB5000 ppm | 16 | 999 | 2.5958 | 0.12 |

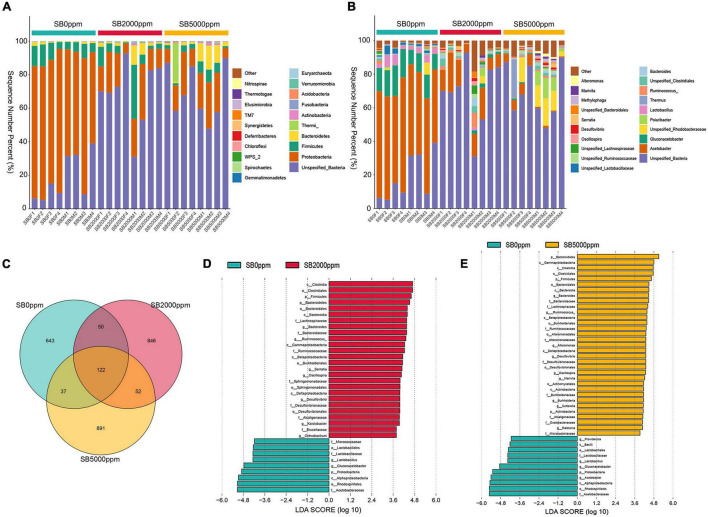

The commensal microbiota of phylum level consisted of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria, which were consistent with the Wolbachia-included data (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 1A). Genus levels mainly included Acetobacter, Gluconacetobacter, and Lactobacillus, which were also consistent with the Wolbachia-included data (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure 1B). There were 122 shared OTUs between 0, 2,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB groups (Figure 3C). There were 643, 846, and 891 unique OTUs in 0, 2,000, and 5,000 ppm of SB groups, respectively (Figure 3C). Species enrichment analysis showed that the dominant commensal bacteria of Acetobacteraceae, Gluconacetobacter, and Lactobacillus were lacking in flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB (Figure 3D), and Acetobacter was further depleted in flies fed with 5,000 ppm of SB (Figure 3E). In Wolbachia-included data, Acetobacter was depleted both in flies fed with 2,000 and 5,000 ppm of SB (Supplementary Figure 1D).

FIGURE 3.

Commensal microbial composition and species enrichment analysis of Wolbachia-excluded data. (A) Commensal microbial composition at the phylum level. (B) Commensal microbial composition at the genus level. (C) Common and unique OTUs number analysis. (D) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores of commensal microbial species in flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB. (E) LDA scores of commensal microbial species in flies fed with 5,000 ppm of SB.

The analysis of observed OTUs showed no significance in the sequencing depth index between SB supplemented flies and no SB supplemented flies whether Wolbachia was excluded or not (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 2A). Chao1 analysis showed that commensal microbiota richness also had no significance between SB supplemented flies and no SB supplemented flies whether Wolbachia was excluded or not (Figure 4B and Supplementary Figure 2B). However, it was uncertain that the commensal microbial diversity was affected by SB due to the inconsistent results of the Shannon and Simpson index between the Wolbachia-excluded data (Figures 4C,D) and the Wolbachia-included data (Supplementary Figures 2C,D).

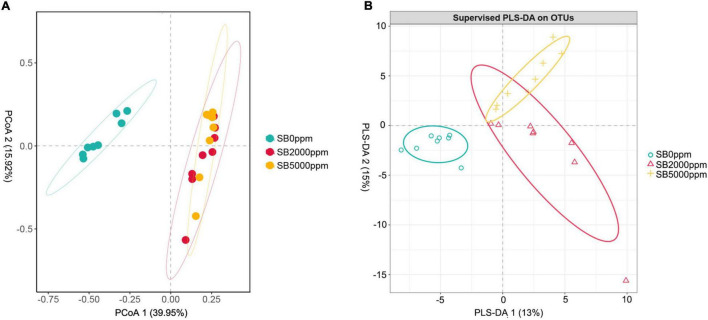

Commensal microbiota of flies fed with SB was well separated from that of flies fed with no SB whether Wolbachia was excluded or not (Figures 5A,B and Supplementary Figures 3A,B). Results of PERMANOVA also manifested that the commensal microbiota of SB-fed flies was significantly different from that of no SB-fed flies (p = 0.002, 0.001, Table 2, p = 0.001, 0.002, Supplementary Table 2). These results indicated that the addition of SB changed the commensal microbiota of D. melanogaster significantly.

FIGURE 5.

Beta diversity of flies’ commensal microbiota fed with SB at genus level of Wolbachia-excluded data. (A) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) score plot based on Bray-Curtis distance. (B) Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) plot.

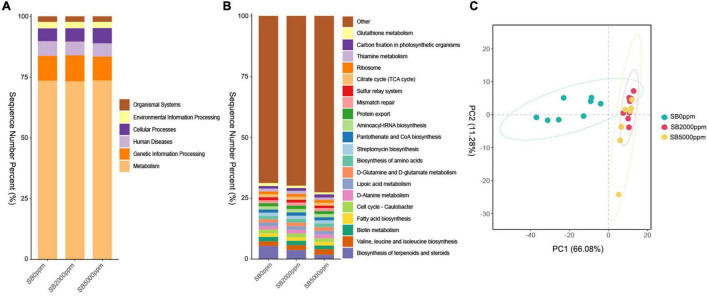

Sodium Benzoate Changed the Commensal Microbial Function of Flies

To further clarify whether the commensal microbial function is modified in a similar manner to shift along with the commensal microbial composition, we conducted function prediction by PICRUSt. The function of KEGG pathways includes metabolism, genetic information processing, human diseases, cellular processes, environmental information processing, and organismal systems at the L1 level in all groups (Figure 6A). KEGG pathway at the L3 level mainly included biosynthesis of terpenoids and steroids; valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis; biotin metabolism; fatty acid biosynthesis; cell cycle-caulobacter; D-alanine metabolism; lipoic acid metabolism; D-glutamine and D-glutamate metabolism; biosynthesis of amino acids; streptomycin biosynthesis; pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis; aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis; protein export; mismatch repair; sulfur relay system; citrate cycle (TCA cycle); ribosome; thiamine metabolism, carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms; and glutathione metabolism in all groups (Figure 6B). For Wolbachia-included data, similar results were found in commensal microbial function at the KEGG L1 level; however, there are some inconsistencies in commensal microbial function at the KEGG L3 level (Supplementary Figures 4A,B). The results of PCA and PERMANOVA showed that the commensal microbial function of flies fed with SB was significantly different from that of flies fed with no SB whether Wolbachia was excluded or not (Figure 6C, Table 3, Supplementary Figure 4C, and Supplementary Table 3).

FIGURE 6.

Function prediction of commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-excluded data. (A) KEGG pathway at L1 level. (B) KEGG pathway at L3 level. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of commensal microbial function at L3 level.

The results of KEGG pathway prediction manifest that cell growth and death, cellular community–prokaryotes, transport, and catabolism pathway abundance were reduced by SB (Figure 7A). Aging, circulatory system, environmental adaptation, and immune system were reduced by SB at 5,000 ppm, whereas the excretory system was increased by SB (Figure 7B). Nucleotide metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, energy metabolism, lipid metabolism, metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides, and global and overview maps were increased by SB at 5,000 ppm; however, chemical structure transformation and metabolism of cofactors and vitamins were reduced by SB at 5,000 ppm (Figure 7C). For KEGG L3 level, benzoate degradation, bile secretion, and carbon metabolism pathway abundance were increased by SB at 5,000 ppm, while biosynthesis of terpenoids and steroids, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, estrogen signaling pathway, and longevity regulating pathway abundance were reduced by SB at 5,000 ppm (Figure 7D).

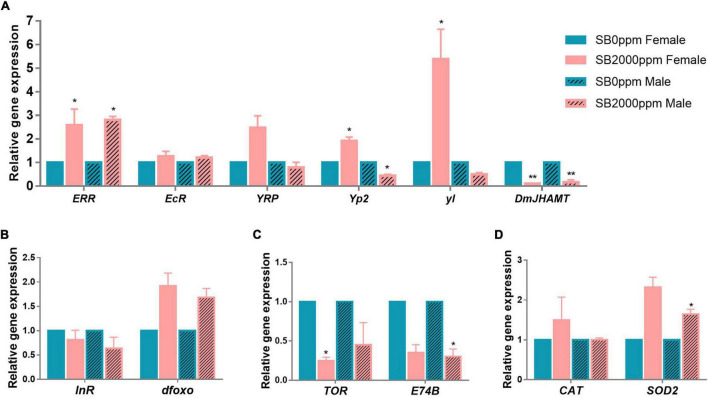

Gene Expressions of Males and Females Fed With Sodium Benzoate

To explore mechanisms of the retarded development of D. melanogaster by SB, we tested the expressions of hormone-, insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) signaling (IIS) pathway-, the target of rapamycin (TOR) pathway-, and antioxidant enzymes-related genes. The expression of ERR was increased in both female and male flies (Figure 8A). EcR and YPR were not affected by SB (Figure 8A). DmJHAMT expression was reduced by SB in both female and male flies (Figure 8A). The yl was highly expressed in females (Figure 8A); Yp2 expression was also increased in females, while it decreased in males (Figure 8A). It was shown that the expressions of InR and dfoxo of the IIS pathway were not altered in both male and female flies fed with SB (Figure 8B). TOR and E74B gene expressions were reduced in females and males, respectively (Figure 8C). For antioxidant enzyme-related genes, CAT was not changed by SB, and SOD2 was increased in male flies (Figure 8D).

FIGURE 8.

Gene expressions of flies fed with SB. (A) Hormone-related genes. (B) IIS pathway-related genes. (C) TOR pathway-related genes. (D) Antioxidant enzymes-related genes. The significance was achieved by comparing SB with the control groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Discussion

In this study, we attempted to explore the effect of SB on host development and the host commensal microbial community using D. melanogaster. Our results demonstrate that 2,000 ppm of SB or higher significantly slowed down the larvae development and shortened the adult life span of D. melanogaster. These results indicated that SB is harmful to host physical health when SB concentrations are added to food at 2,000 ppm or higher. This is consistent with the results of previous studies that showed high concentrations of SB would be harmful to the health, as evidenced by reduced reproductivity, developmental defects, oxidative stress, and anxiety-like behavior (Gaur et al., 2018; Khodaei et al., 2019; El-Shennawy et al., 2020; Jewo et al., 2020). Interestingly, the no significant difference in survival rates between 0 + 0 and 2000 + 0 groups indicates that the exposure of SB to flies in early life-only may not affect the life span (Figures 2A,B). However, the significant difference in the survival rates between 0 + 0 and 0 + 2000 groups indicates that continuous adult exposure had more harmful effects on Drosophila life span than early life-only exposure (Figures 2A,B).

Of note, the commensal microbial composition was changed in D. melanogaster fed with 2,000 or 5,000 ppm of SB. The symbionts could modulate the life-history traits of D. melanogaster, including juvenile growth, life span, and behavior (Erkosar et al., 2013; Lee and Brey, 2013; Strigini and Leulier, 2016). An increase in the unique OTUs after SB intake was found in this study. This could be explained by the decrease in the dominant species resulting in the rearrangement of the commensal microbiota ecological niche in D. melanogaster, and then, the rearrangement of the commensal microbiota ecological niche led to the increased abundance of unique OTUs.

Acetobacteraceae and Lactobacillaceae are two dominant families of Drosophila commensal intestinal tract bacteria in both wild and laboratory stains (Erkosar et al., 2013; Lee and Brey, 2013; Storelli et al., 2018), playing important roles in the development of D. melanogaster, including the larval growth, fecundity, immunity, and life cycle (Shin et al., 2011; Sansone et al., 2015; Elgart et al., 2016). Lactobacillus plantarum promoted the systemic growth of D. melanogaster by modulating hormonal signals and TOR-dependent nutrient sensing (Storelli et al., 2011), induced the intestinal peptidases transcription, and increased the amino acid uptake of D. melanogaster larvae (Storelli et al., 2018). Téfit and Leulier (2017) demonstrated that Lactobacillus plantarum promotes the growth of Drosophila larvae and leads to earlier metamorphosis and adult emergence upon nutrient scarcity compared with axenic individuals. In this study, SB intake significantly reduced the abundance of Lactobacillus, which may be one of the factors that result in delaying of the D. melanogaster larval development. Nevertheless, inconsistent results were found in the effect of Lactobacillus on the life span of Drosophila. Téfit and Leulier (2017) observed a life span extension in nutritionally challenged males, while Fast et al. (2018) displayed that mono-association of adult Drosophila with Lactobacillus plantarum curtailed adult longevity compared with germ-free flies. Thus, in this study, it is uncertain whether the shortened life span is related to the reduced Lactobacillus or not. Acetobacter could promote the growth and reproduction of Drosophila host (Shin et al., 2011; Fridmann-Sirkis et al., 2014; Elgart et al., 2016). Acetobacter increased triglycerides and starvation resistance, increased fecundity, enhanced larval growth, and shortened the longevity in D. melanogaster, whereas co-evolution confers that the host more fits to the adverse environment (Obata et al., 2018). We also observed a decreased abundance in Acetobacter by SB. We further speculated that the corresponding functional loss associated with Acetobacter may also be one of the reasons for postponing the development of D. melanogaster larvae.

The function of commensal microbiota in flies fed with 2,000 or 5,000 ppm of SB significantly differed from that in flies fed with no SB (Figure 6C, Table 3, Supplementary 4C, Supplementary Table 3). Pathways of metabolism, genetic information processing, human diseases, cellular processes, environmental information processing, and organismal systems were significantly changed by SB at concentrations of 2,000 ppm or higher. Moreover, we also found metabolism pathways at L3 level significantly changed by SB, including an increased abundance of benzoate degradation, bile secretion, and carbon metabolism pathways and a reduced abundance of biosynthesis of terpenoids and steroids, biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids, estrogen signaling pathway, and longevity regulating pathways (Figure 7D). The increased abundance of benzoate degradation may result from the high concentrations of SB intake. The reduced biosynthesis of terpenoids and steroids and estrogen signaling pathway may relate to the changed endocrine system by SB intake. Unsaturated fatty acids have effects on blood lipid concentrations, blood pressure, inflammatory response, arrhythmia and endothelial function (Lunn and Theobald, 2006). Unsaturated fatty acids also play a role in antimicrobial activity (Zheng et al., 2005). The decreased biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids may lead to a reduced protection of the host. The decreased abundance of longevity regulating pathway may explain a bit of the shortened life span by SB at concentrations of 2,000 ppm or higher. Strangely, the above pathways were changed more significantly in flies fed with 5,000 ppm of SB than in flies fed with 2,000 ppm. However, the physiological changes already occurred in flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB. The reason needs to be explored further.

In addition, some contamination of Wolbachia was found in this study. This may result from incomplete separation of the reproductive tract or the contamination during the reproductive tract dissection. We further compared the analysis results of Wolbachia-included data with Wolbachia-excluded data. Except for the further depletion of Acetobacter by 5,000 ppm of SB, similar results were found in differential species and commensal microbial composition whether the Wolbachia was excluded or not. Besides, the commensal microbial function was significantly affected by SB whether the Wolbachia was excluded or not. Wolbachia was a common symbiont with insects, playing important roles in modifications of host fitness. Wolbachia infection increased the reproduction and produced a positive- or a non-effect on host survival in D. melanogaster (Fry and Rand, 2002; Fry et al., 2004; Gruntenko et al., 2017). However, it is uncertain that the retarded development of larvae and shortened life span of adult flies were related to Wolbachia. Therefore, further studies performed in Wolbachia-free D. melanogaster are needed to exclude the effect of Wolbachia.

Larval development was reported to be most related to the endocrine hormone. Juvenile hormones (JHs), a family of sesquiterpenoid hormones, are a key endocrine regulator of insects’ metamorphosis, development, growth, reproduction, and aging (Gilbert et al., 2000; Meiselman et al., 2017). JH regulates insect metamorphosis, including preventing immature larvae from going through precocious larval-pupal transition and increasing the number of molts (Kayukawa et al., 2017). JH acid O-methyltransferase (JHAMT) is the enzyme that transfers a methyl group from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) to the carboxyl group of JH acids, resulting in the catalyzation of the final step of the JH to produce active JHs in Lepidoptera (Shinoda and Itoyama, 2003; Niwa et al., 2008). The decrease in DmJHAMT transcription of flies fed with SB indicates that the SB may have delayed the insect molting, leading to the slow development of Drosophila larvae.

Ecdysone receptor (EcR) is a nuclear hormone receptor that activates the arthropod steroid hormones ecdysteroids and regulates molting, metamorphosis, reproduction, diapause, and innate immunity in insects (Koelle et al., 1991; Yao et al., 1992; Thomas et al., 1993). EcR plays a considerable role in the larval-to-prepupal transition of Drosophila (Uyehara and McKay, 2019). EcR isoforms are required for larval molting and neuron remodeling during metamorphosis in insects (Schubiger et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2020). In addition, many studies have shown that EcR is a key factor affecting life span and reproduction (Antoniewski et al., 1996; Thummel, 1996; Riddiford et al., 2000). Reduced EcR levels lead to increased longevity and stress resistance in adults (Simon et al., 2003; Tricoire et al., 2009). In this study, the mRNA level of EcR remained unchanged in flies fed with SB, suggesting that the retarded larval development and shortened life span by SB were not likely through the EcR regulation.

Estrogen-related receptor (ERR), another nuclear hormone receptor, is a critical metabolic transition during Drosophila development. dERR is involved in a transcriptional switch during pupal development that determines the adult fly’s glucose oxidation and lipogenesis (Beebe et al., 2020). It also reported that dERR is essential for carbohydrate metabolism in larval stages, and dERR mutants die as larvae (Tennessen et al., 2011). Our study found that ERR transcripts increased in flies fed with SB. Nevertheless, the relationship between the retarded development of flies resulting from SB and the increased ERR transcripts still needs to be investigated.

The yolk protein (YP) receptor (YPR) is a receptor of egg yolk protein in D. melanogaster. Vitellogenin as a precursor of egg yolk protein has become a well-established biomarker for measuring the effect of environmental chemicals on estrogenic activity (Tufail and Takeda, 2009). We have observed no significant changes in the YPR level. Yp2 was significantly increased in females fed with 2,000 ppm of SB, whereas it decreased in males. Yolkless (yl) gene was significantly enhanced in females fed with 2,000 ppm of SB. Regarding the inconsistency in the changes of Yp2 and yl expression between males and females, it is uncertain that Yp2 and yl were related to the retarded development of larvae in this study.

The IIS pathway could be another factor that may affect Drosophila development. A previous study has demonstrated that IIS pathway controls the formation of larva, stress-resistant and long-lived (Kapahi et al., 2004). IIS directly regulates Drosophila developmental transition timing through the production of the molting hormone ecdysone (Ghosh, 2021). A previous study found that an increased IIS improved the larval growth rate and promoted the metamorphosis of Drosophila, which was accompanied by the synthesis of precocious ecdysone and increased transcription of ecdysone biosynthetic genes (Walkiewicz and Stern, 2009). For example, Tu et al. (2005) showed that IIS pathway may regulate JH synthesis through the control of JH regulatory neuropeptides. Moreover, it was reported that there is a feedback loop in the interaction of IIS and JH, where IIS controlled stress resistance through JH/dopamine signaling regulation (Gruntenko and Rauschenbach, 2018). There is also an interaction between the commensal microbiota and IIS. Increased abundance of Wolbachia could enhance IIS through an evolutionary explanation (Ikeya et al., 2009). However, InR and dfoxo, as two key factors of IIS, remained unchanged by 2,000 ppm of SB in our study. This indicated that the altered developmental rate of Drosophila was not through IIS pathway.

The TOR pathway has emerged as the major regulator of growth and size in Drosophila (Kapahi et al., 2004). TOR pathway is a highly conserved nutrient-sensing pathway that regulates growth, metabolism, and aging (Bjedov et al., 2010). L. plantarum association impacts both InR and Ecd signaling in larvae, and L. plantarum exerts its benefit by acting genetically upstream of the TOR-dependent host nutrient sensing system controlling hormonal growth signaling (Storelli et al., 2011). Our study shows that TOR decreased only in females and E74B decreased only in males fed with 2,000 ppm of SB, which means that SB may decrease the TOR pathway to some extent.

Overall, we investigated the effect of SB on the growth and development of D. melanogaster larvae and whether SB affects the commensal microbial compositions and functions. Our results will help to clarify the interaction between SB, commensal microbiota, and host development. In conclusion, we have found a longer larval–pupal and pupal–adult metamorphosis timing and a shorter life span in flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB or higher. Transcripts of endocrine encoding genes including ERR and DmJHAMT were changed. The commensal microbial compositions and functions were also found to be changed in adult flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB or higher. These results indicate that the retarded Drosophila larvae developmental time and shortened life span by SB may be caused by the changes in endocrine level and commensal microbiota. Further multi-omics studies, such as metagenomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics, are needed to verify this mechanism.

Data Availability Statement

The 16S sequence data generated in this study were submitted to the NCBI SRA database, accession number PRJNA774185 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA774185).

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the animal study because the manuscript presents results of research on invertebrate animals (Drosophila melanogaster).

Author Contributions

YD and QP contributed to the conception and design of the study. YD, ZD, LS, and DZ performed the experiments. YD and DZ collected and analyzed the data. YD wrote the manuscript. CX, SZ, LF, and HL reviewed and polished the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (grant numbers: ZR2020QC241 and ZR2020QD133) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 12105163).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.911928/full#supplementary-material

Commensal microbial composition and species enrichment analysis of Wolbachia-included data. (A) Commensal microbial composition at the phylum level. (B) Commensal microbial composition at the genus level. (C) Common and unique OUTs number analysis. (D) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores of commensal microbial species in flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB. (E) LDA scores of commensal microbial species in flies fed with 5,000 ppm of SB.

Alpha diversity of flies’ commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-included data fed with SB at the genus level. (A) Observed OTUs. (B) Chao1. (C) Shannon. (D) Simpson.

Beta diversity of flies’ commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-included data fed with SB at the genus level. (A) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) score plot based on Bray-Curtis distance. (B) Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) plot.

Function prediction of commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-included data. (A) KEGG pathway at L1 level. (B) KEGG pathway at L3 level. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of commensal microbial function at L3 level.

References

- Antoniewski C., Mugat B., Delbac F., Lepesant J. A. (1996). Direct repeats bind the EcR/USP receptor and mediate ecdysteroid responses in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 2977–2986. 10.1128/MCB.16.6.2977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäumler A. J., Sperandio V. (2016). Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature 535 85–93. 10.1038/nature18849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe K., Robins M. M., Hernandez E. J., Lam G., Horner M. A., Thummel C. S. (2020). Drosophila estrogen-related receptor directs a transcriptional switch that supports adult glycolysis and lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 34 701–714. 10.1101/gad.335281.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov I., Toivonen J. M., Kerr F., Slack C., Jacobson J., Foley A., et al. (2010). Mechanisms of life span extension by rapamycin in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster. Cell Metab. 11 35–46. 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokulich N. A., Kaehler B. D., Rideout J. R., Dillon M., Bolyen E., Knight R., et al. (2018). Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6:90. 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callahan B. J., McMurdie P. J., Rosen M. J., Han A. W., Johnson A. J. A., Holmes S. P. (2016). DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13 581–583. 10.1038/nmeth.3869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Las Heras J., Aldámiz-Echevarría L., Martínez-Chantar M. L., Delgado T. C. (2017). An update on the use of benzoate, phenylacetate and phenylbutyrate ammonia scavengers for interrogating and modifying liver nitrogen metabolism and its implications in urea cycle disorders and liver disease. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 13 439–448. 10.1080/17425255.2017.1262843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgart M., Stern S., Salton O., Gnainsky Y., Heifetz Y., Soen Y. (2016). Impact of gut microbiota on the fly’s germ line. Nat. Commun. 7:11280. 10.1038/ncomms11280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Shennawy L., Kamel M. A. E.-N., Khalaf A. H. Y., Yousef M. I. (2020). Dose-dependent reproductive toxicity of sodium benzoate in male rats: inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis. Reprod. Toxicol. 98 92–98. 10.1016/j.reprotox.2020.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkosar B., Storelli G., Defaye A., Leulier F. (2013). Host-intestinal microbiota mutualism:“learning on the fly”. Cell Host Microbe 13 8–14. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast D., Duggal A., Foley E. (2018). Monoassociation with Lactobacillus plantarum disrupts intestinal homeostasis in adult Drosophila melanogaster. MBio 9 e01114–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration [FDA] (2017). Food and Drug Administration of the United States of America (FDA). Food and beverages. Silver Spring: Food and Drug Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Fridmann-Sirkis Y., Stern S., Elgart M., Galili M., Zeisel A., Shental N., et al. (2014). Delayed development induced by toxicity to the host can be inherited by a bacterial-dependent, transgenerational effect. Front. Genet. 5:27. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A. J., Rand D. M. (2002). Wolbachia interactions that determine Drosophila melanogaster survival. Evolution 56 1976–1981. 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb00123.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry A., Palmer M., Rand D. (2004). Variable fitness effects of Wolbachia infection in Drosophila melanogaster. Heredity 93 379–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaur H., Purushothaman S., Pullaguri N., Bhargava Y., Bhargava A. (2018). Sodium benzoate induced developmental defects, oxidative stress and anxiety-like behaviour in zebrafish larva. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 502 364–369. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gensollen T., Iyer S. S., Kasper D. L., Blumberg R. S. (2016). How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 352 539–544. 10.1126/science.aad9378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. S. (2021). Novel Aspects of Insulin Signaling Underlying Growth and Development in Drosophila melanogaster. PhD Thesis. Dresden: Technische Universität. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert L. I., Granger N. A., Roe R. M. (2000). The juvenile hormones: historical facts and speculations on future research directions. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 30 617–644. 10.1016/s0965-1748(00)00034-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S. R., Pop M., DeBoy R. T., Eckburg P. B., Turnbaugh P. J., Samuel B. S., et al. (2006). Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312 1355–1359. 10.1126/science.1124234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntenko N. E., Rauschenbach I. Y. (2018). The role of insulin signalling in the endocrine stress response in Drosophila melanogaster: a mini-review. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 258 134–139. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruntenko N. Å, Ilinsky Y. Y., Adonyeva N. V., Burdina E. V., Bykov R. A., Menshanov P. N., et al. (2017). Various Wolbachia genotypes differently influence host Drosophila dopamine metabolism and survival under heat stress conditions. BMC Evolut. Biol. 17:252. 10.1186/s12862-017-1104-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husson M.-C., Schiff M., Fouilhoux A., Cano A., Dobbelaere D., Brassier A., et al. (2016). Efficacy and safety of iv sodium benzoate in urea cycle disorders: a multicentre retrospective study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 11:127. 10.1186/s13023-016-0513-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya T., Broughton S., Alic N., Grandison R., Partridge L. (2009). The endosymbiont Wolbachia increases insulin/IGF-like signalling in Drosophila. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 276 3799–3807. 10.1098/rspb.2009.0778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewo P. I., Oyeniran D. A., Ojekale A. B., Oguntola J. A. (2020). Histological and biochemical studies of germ cell toxicity in male rats exposed to sodium benzoate. J. Adv. Med. Pharm. Sci. 22 51–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P., Zid B. M., Harper T., Koslover D., Sapin V., Benzer S. (2004). Regulation of lifespan in Drosophila by modulation of genes in the TOR signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 14 885–890. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabay O., Kocoglu E., Ince N., Sahan T., Ozdemir D. (2006). In vitro activity of sodium benzoate against clinically relevant Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolates. J. Microbiol. 44 129–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayukawa T., Jouraku A., Ito Y., Shinoda T. (2017). Molecular mechanism underlying juvenile hormone-mediated repression of precocious larval–adult metamorphosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 1057–1062. 10.1073/pnas.1615423114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasnavis S., Pahan K. (2012). Sodium benzoate, a metabolite of cinnamon and a food additive, upregulates neuroprotective Parkinson disease protein DJ-1 in astrocytes and neurons. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 7 424–435. 10.1007/s11481-011-9286-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodaei F., Kholghipour H., Hosseinzadeh M., Rashedinia M. (2019). Effect of sodium benzoate on liver and kidney lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzymes in mice. J. Rep. Pharm. Sci. 8 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Koelle M. R., Talbot W. S., Segraves W. A., Bender M. T., Cherbas P., Hogness D. S. (1991). The Drosophila EcR gene encodes an ecdysone receptor, a new member of the steroid receptor superfamily. Cell 67 59–77. 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90572-g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu M., Mondal S., Roy A., Martinson J. L., Pahan K. (2016). Sodium benzoate, a food additive and a metabolite of cinnamon, enriches regulatory T cells via STAT6-mediated upregulation of TGF-β. J. Immunol. 197 3099–3110. 10.4049/jimmunol.1501628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane H. Y., Lin C. H., Green M. F., Hellemann G., Huang C. C., Chen P. W., et al. (2013). Add-on treatment of benzoate for schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of D-amino acid oxidase inhibitor. JAMA Psychiatry 70 1267–1275. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langille M. G., Zaneveld J., Caporaso J. G., McDonald D., Knights D., Reyes J. A., et al. (2013). Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 814–821. 10.1038/nbt.2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. J., Brey P. T. (2013). How microbiomes influence metazoan development: insights from history and Drosophila modeling of gut-microbe interactions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 29 571–592. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennerz B. S., Vafai S. B., Delaney N. F., Clish C. B., Deik A. A., Pierce K. A., et al. (2015). Effects of sodium benzoate, a widely used food preservative, on glucose homeostasis and metabolic profiles in humans. Mol. Genet. Metab. 114 73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Chen P. K., Chang Y. C., Chuo L. J., Chen Y. S., Tsai G. E., et al. (2014). Benzoate, a D-amino acid oxidase inhibitor, for the treatment of early-phase Alzheimer disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry 75 678–685. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C. H., Yang H. T., Chen P. K., Wang S. H., Lane H. Y. (2020). Precision medicine of sodium benzoate for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 16 509–518. 10.2147/NDT.S234371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke B. G., Casagrande T. A., Cardoso L. A. C. (2018). Food additives and their health effects: a review on preservative sodium benzoate. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 17 306–310. [Google Scholar]

- Lunn J., Theobald H. (2006). The health effects of dietary unsaturated fatty acids. Nutr. Bull. 31 178–224. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura A., Fujita Y., Iyo M., Hashimoto K. (2015). Effects of sodium benzoate on pre-pulse inhibition deficits and hyperlocomotion in mice after administration of phencyclidine. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 27 159–167. 10.1017/neu.2015.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiselman M., Lee S. S., Tran R.-T., Dai H., Ding Y., Rivera-Perez C., et al. (2017). Endocrine network essential for reproductive success in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 E3849–E3858. 10.1073/pnas.1620760114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misel M. L., Gish R. G., Patton H., Mendler M. (2013). Sodium benzoate for treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9:219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E., Cotter P., Healy S., Marques T. M., O’sullivan O., Fouhy F., et al. (2010). Composition and energy harvesting capacity of the gut microbiota: relationship to diet, obesity and time in mouse models. Gut 59 1635–1642. 10.1136/gut.2010.215665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair B. (2001). Final report on the safety assessment of Benzyl Alcohol, Benzoic Acid, and Sodium Benzoate. Int. J. Toxicol. 20 23–50. 10.1080/10915810152630729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NeSmith M., Ahn J., Flamm S. L. (2016). Contemporary understanding and management of overt and covert hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12:91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa R., Niimi T., Honda N., Yoshiyama M., Itoyama K., Kataoka H., et al. (2008). Juvenile hormone acid O-methyltransferase in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38 714–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata F., Fons C. O., Gould A. P. (2018). Early-life exposure to low-dose oxidants can increase longevity via microbiome remodelling in Drosophila. Nat. Commun. 9:975. 10.1038/s41467-018-03070-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper J. D., Piper P. W. (2017). Benzoate and sorbate salts: a systematic review of the potential hazards of these invaluable preservatives and the expanding spectrum of clinical uses for sodium benzoate. Comprehensive Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 16 868–880. 10.1111/1541-4337.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddiford L. M., Cherbas P., Truman J. W. (2000). Ecdysone receptors and their biological actions. Vitam. Horm. 60 1–73. 10.1016/s0083-6729(00)60016-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohart F., Gautier B., Singh A., Lê Cao K. A. (2017). mixOmics: an R package for ‘omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13:e1005752. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone C. L., Cohen J., Yasunaga A., Xu J., Osborn G., Subramanian H., et al. (2015). Microbiota-dependent priming of antiviral intestinal immunity in Drosophila. Cell Host Microbe 18 571–581. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubiger M., Wade A. A., Carney G. E., Truman J. W., Bender M. (1998). Drosophila EcR-B ecdysone receptor isoforms are required for larval molting and for neuron remodeling during metamorphosis. Development 125 2053–2062. 10.1242/dev.125.11.2053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin S. C., Kim S. H., You H., Kim B., Kim A. C., Lee K. A., et al. (2011). Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science 334 670–674. 10.1126/science.1212782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinoda T., Itoyama K. (2003). Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase: a key regulatory enzyme for insect metamorphosis. Proc.Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 11986–11991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon A. F., Shih C., Mack A., Benzer S. (2003). Steroid control of longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 299 1407–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic D., Comic L., Stefanovic O., Solujic-Sukdolak S. (2009). Antimicrobial effects of sodium benzoate, sodium nitrite and potassium sorbate and their synergistic action in vitro. Bulg. J. Agricult. Sci. 15 307–311. [Google Scholar]

- Storelli G., Defaye A., Erkosar B., Hols P., Royet J., Leulier F. (2011). Lactobacillus plantarum promotes Drosophila systemic growth by modulating hormonal signals through TOR-dependent nutrient sensing. Cell Metab. 14 403–414. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storelli G., Strigini M., Grenier T., Bozonnet L., Schwarzer M., Daniel C., et al. (2018). Drosophila perpetuates nutritional mutualism by promoting the fitness of its intestinal symbiont Lactobacillus plantarum. Cell Metab. 27 362–377.e8. 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.11.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strigini M., Leulier F. (2016). The role of the microbial environment in Drosophila post-embryonic development. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 64 39–52. 10.1016/j.dci.2016.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Téfit M. A., Leulier F. (2017). Lactobacillus plantarum favors the early emergence of fit and fertile adult Drosophila upon chronic undernutrition. J. Exp. Biol. 220 900–907. 10.1242/jeb.151522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennessen J. M., Baker K. D., Lam G., Evans J., Thummel C. S. (2011). The Drosophila estrogen-related receptor directs a metabolic switch that supports developmental growth. Cell Metab. 13 139–148. 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas H. E., Stunnenberg H. G., Stewart A. F. (1993). Heterodimerization of the Drosophila ecdysone receptor with retinoid X receptor and ultraspiracle. Nature 362 471–475. 10.1038/362471a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel C. S. (1996). Flies on steroids—Drosophila metamorphosis and the mechanisms of steroid hormone action. Trends Genet. 12 306–310. 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thursby E., Juge N. (2017). Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 474 1823–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricoire H., Battisti V., Trannoy S., Lasbleiz C., Pret A. M., Monnier V. (2009). The steroid hormone receptor EcR finely modulates Drosophila lifespan during adulthood in a sex-specific manner. Mech. Ageing Dev. 130 547–552. 10.1016/j.mad.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu M. P., Yin C. M., Tatar M. (2005). Mutations in insulin signaling pathway alter juvenile hormone synthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 142 347–356. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tufail M., Takeda M. (2009). Insect vitellogenin/lipophorin receptors: molecular structures, role in oogenesis, and regulatory mechanisms. J. Insect Physiol. 55 88–104. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyehara C. M., McKay D. J. (2019). Direct and widespread role for the nuclear receptor EcR in mediating the response to ecdysone in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 9893–9902. 10.1073/pnas.1900343116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Baeza Y., Pirrung M., Gonzalez A., Knight R. (2013). EMPeror: a tool for visualizing high-throughput microbial community data. Gigascience 2:16. 10.1186/2047-217X-2-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkiewicz M. A., Stern M. (2009). Increased insulin/insulin growth factor signaling advances the onset of metamorphosis in Drosophila. PLoS One 4:e5072. 10.1371/journal.pone.0005072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. Y., Deng P., Zhang Q., Li A., Fu K. Y., Guo W. C., et al. (2020). Ecdysone receptor isoforms play distinct roles in larval–pupal–adult transition in Leptinotarsa decemlineata. Insect Sci. 27 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao T. P., Segraves W. A., Oro A. E., McKeown M., Evans R. M. (1992). Drosophila ultraspiracle modulates ecdysone receptor function via heterodimer formation. Cell 71 63–72. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90266-f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T., Doyle M. P. (2006). Reduction of Campylobacter jejuni on chicken wings by chemical treatments. J. Food Protect. 69 762–767. 10.4315/0362-028x-69.4.762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng C. J., Yoo J. S., Lee T. G., Cho H. Y., Kim Y. H., Kim W. G. (2005). Fatty acid synthesis is a target for antibacterial activity of unsaturated fatty acids. FEBS Lett. 579 5157–5162. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Commensal microbial composition and species enrichment analysis of Wolbachia-included data. (A) Commensal microbial composition at the phylum level. (B) Commensal microbial composition at the genus level. (C) Common and unique OUTs number analysis. (D) Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores of commensal microbial species in flies fed with 2,000 ppm of SB. (E) LDA scores of commensal microbial species in flies fed with 5,000 ppm of SB.

Alpha diversity of flies’ commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-included data fed with SB at the genus level. (A) Observed OTUs. (B) Chao1. (C) Shannon. (D) Simpson.

Beta diversity of flies’ commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-included data fed with SB at the genus level. (A) Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) score plot based on Bray-Curtis distance. (B) Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) plot.

Function prediction of commensal microbiota of Wolbachia-included data. (A) KEGG pathway at L1 level. (B) KEGG pathway at L3 level. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of commensal microbial function at L3 level.

Data Availability Statement

The 16S sequence data generated in this study were submitted to the NCBI SRA database, accession number PRJNA774185 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=PRJNA774185).