Abstract

In cattle, Staphylococcus aureus is a major pathogen of increasing importance due to its association with intramammary infections (IMIs), which are a primary cause of antibiotic use on farms and thus of the rise in antibiotic resistance. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which are frequently isolated from cases of bovine mastitis, represent a public health problem worldwide. Understanding the epidemiology and the evolution of these strains relies on typing methods. Such methods were phenotypic at first, but more recently, molecular methods have been increasingly utilized. Multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA), a high-throughput molecular method for determining genetic diversity and the emergence of host- or udder-adapted clones, appears to be the most useful PCR-based method. Despite the difficulties present in reproducibility, interlaboratory reliability, and hard work, it is agreed that pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) remains the gold standard, particularly for short-term surveillance. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) is a good typing method for long-term and global epidemiological investigations, but it is not suitable for outbreak investigations. Staphylococcal protein A (spa) typing is the most widely used method today for first-line typing in the study of molecular evolution, and outbreaks investigations. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing has gained popularity for the evolutionary analysis of MRSA strains. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and DNA microarrays that represent relatively new DNA-based technologies, provide more information for tracking antibioresistant and virulent outbreak strains. They offer a higher discriminatory power, but are not suitable for routine use in clinical veterinary medicine at this time. Descriptions of the evolution of these methods, their advantages, and limitations are given in this review.

Keywords: Cattle; (IMIs), Intramammary infections; Molecular typing methods; (MRSA), Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; (S. aureus ), Staphylococcus aureus

1. Introduction

Bovine mastitis is the most frequent and costly infectious disease occurring in dairy cows, impacting milk production and leading to economic losses and public health concerns. Mastitis typically results from bacterial intramammary infections (IMIs), the most common causative agent being Staphylococcus aureus (Alzohairy, 2011, Naushad et al., 2020; Pérez et al., 2020). Its significance is widely recognized and its prevalence varies from 5% to 30% in clinical and 5% to 10% in subclinical mastitis cases (Marsilio et al., 2018, Peton and Le Loir, 2014). In humans, S. aureus is an important bacterial pathogen that is associated with serious community-acquired and nosocomial diseases (Stefani et al., 2012), and it is one of the most reported cause of food-borne diseases in the world (Aqib et al., 2018, Pérez et al., 2020). Multidrug-resistant strains of S. aureus in veterinary medicine are increasing in incidence and are a growing problem worldwide (Aires-de-Sousa, 2017). Initially, beta-lactam resistance, especially penicillin resistance, was reported in the 1940 s as one of the main problems related to the persistence of bovine mastitis caused by S. aureus (Werckenthin et al., 2001, Yang et al., 2017). Reported penicillin G resistance frequency has ranged from 30% to 100% in studies published in the last 10 years (Rabello et al., 2020). Another problem in cases of bovine mastitis caused by S. aureus is resistance to methicillin (Aires-de-Sousa, 2017, Fisher and Paterson, 2020, Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010, Yi et al., 2018) via the acquisition of a staphylococcal cassette chromosome (SCC)mec element carrying mecA (Aqib et al., 2018, Garcia-Alvarez et al., 2011). It complicates veterinary treatment (Havaei et al., 2015) and increases the risk of transmission of resistant strains from cows to humans (Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010). Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in cattle was first reported in Belgium between1972 and 1975 by Devriese et al. (1972). An increasing number of cases of MRSA isolates in cows were subsequently reported worldwide (Graveland et al., 2011). MRSA isolates have also been found in a wide range of animal species, including various livestock species (Aires-de-Sousa, 2017; Alzohairy, 2011). These MRSA strains have evolved into three types: healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) since the 1960 s; community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) since the 1990 s; and new strains that have been associated with livestock since the 2000 s, so-called live-stock-associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) (Graveland et al., 2011, Li et al., 2017). The emergence of the latest MRSA strains in cattle is of great concern for livestock and public health (Haran et al., 2012, Wang et al., 2015, Weese, 2010). Numerous strains clones have emerged and been disseminated worldwide (Aires-de-Sousa, 2017). Typical of this clone is its multiresistance to several classes of antimicrobial agents (Butaye et al., 2016). In this context, and over the past two decades, S. aureus isolates from humans and cattle have been extensively studied and a growing number of typing methods for epidemiological and evolutionary studies have been applied. Typing methods can be undertaken at different levels, depending on the situation, for small outbreak investigations or global epidemiological studies (van Belkum et al., 2007). At each of these levels, different methods may be applied. The current molecular typing methods include three categories: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based, DNA-fragment-analysis-based, and DNA-sequence-based methods (Ruppitsch, 2016). New techniques have also become available, including the use of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and virulence gene arrays (El-Ashker et al., 2015, Fisher and Paterson, 2020). In this review, we aim to show the usefulness of molecular typing methods used to investigate the epidemiology and evolutionary nature of S. aureus isolates from bovine IMIs. We start with the different phenotypic methods, and continue with current and promising new approaches. The greatest attention is given to molecular typing, for which we discuss the most widely used methods specifying their advantages and disadvantages.

2. Typing methods for bovine Staphylococcus aureus

Bacterial typing has been used for decades to study bacteria at the species and sub-species level (Zadoks et al., 2011). It is a crucial tool for pathogen surveillance and outbreak investigation (El-Ashker et al., 2015, Ruppitsch, 2016). It involves a large variety of methods that may have potential for epidemiological and evolutionary studies. Phenotypic and/or genotypic features can perform these typing methods. Two Several criteria are used to assess the utility of each system. The performance criteria include the typeability of the strains in question, the reproducibility of the results, and a high discriminatory power, whereas convenience criteria include versatility, rapidity, ease of execution and interpretation, cost, and the availability of materials and technical expertise (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018, Zadoks and Schukken, 2006).

2.1. Phenotypic typing methods

The earliest methods that were used to identify and type organisms were based on the determination of serotypes, biotypes, phage-types, antibiograms or Multilocus Enzyme Electrophoresis (MLEE). The phenotypic methods, in general, are simple, easy to perform, less expensive (El-Sayed et al., 2017), but have lower typeability, reproducibility, and discriminatory power than genotypic methods (Zadoks and Schukken, 2006). The features of phenotyping methods for S. aureus isolated from bovine IMIs are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Features of phenotyping methods for epidemiological studies of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine intramammary infections.

| Characteristic | R | T | S | DP | EU | TR | Int | Cost | ET | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiogram typing | Good | Low | No | Poor | Easy | Rapid | Simple | Low | Low | DeOliveira et al., 2000, Aarestrup et al., 1995, Sabour et al., 2004 |

| Biotyping | Limited | Low | No | Poor | Easy | Rapid | Simple | Low | Low | Aarestrup et al., 1995, Myllys et al., 1997, Sommerhäuser et al., 2003 |

| Serotyping | Limited | Moderate | No | Low | Easy | Rapid | Simple | High | Low | White et al., 1962, Guidry et al., 1998, Tollersrud et al., 2000b |

| Phage typing | Limited | Limited | No | Low | Difficult | Time consuming | Complex | High | Low | Aarestrup et al., 1997, Zadoks et al., 2002, Blair and Williams, 1961, Su et al., 1999, Sabour et al., 2004 |

| MLEE | High | Moderate | NA | Low | Difficult | Time consuming | Complex | High | Low | Fitzgerald et al., 1997, Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018, Su et al., 1999 |

| MALDI-TOF MS | High | High | NA | High | Easy | Very fast | Complex | High | Low | Barreiro et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2020, Shell et al., 2017, Kasela and Malm, 2018 |

Abbreviations: R: Reproducibility; T: Typeability; S: Stability; DP: Discriminatory power; EU: Ease of use; TR: Time required; Int: Interpretation; ET: Epidemiologic typing. MLEE: Multilocus Enzyme Electrophoresis; MALDI-TOF MS: Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry; NA: not available.

2.1.1. Antibiogram typing

Antibiogram typing involves the comparison of isolates’ susceptibilities to a range of selected antibiotics. This testing method is traditionally performed by means of disk diffusion or broth microdilution tests of an antibiotic (DeOliveira et al., 2000; Werckenthin et al., 2001). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing is still widely applied among S. aureus isolates from bovine mastitis for susceptibility verification, since its results are crucial for selecting effective antibiotic therapies (DeOliveira et al., 2000). S. aureus was found to be the most common penicillin-resistant pathogen in bovine mastitis (Alzohairy, 2011, Ben Said et al., 2016, Dendani Chadi et al., 2010; DeOliveira et al., 2000; Haveri et al., 2005, Kroning et al., 2018, Li et al., 2017, McMillan et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2018, Werckenthin et al., 2001, Yang et al., 2017). MRSA strains also are usually associated with a multidrug-resistant profile (Mohammed et al., 2018, Moon et al., 2007; Nam et al., 2011; Yi et al., 2018). Antibiogram typing is easy to perform, gives rapid results, and, above all, is cheap and readily available in a typical microbiology laboratory (DeOliveira et al., 2000). Nevertheless, with many strains were antibiotic susceptible or without plasmids, and poor discriminatory ability, antibiogram testing has no epidemiological purpose (Aarestrup et al., 1995, Sabour et al., 2004).

2.1.2. Biotyping

Devriese (1984) developed a biotyping scheme for S. aureus based on several phenotypic differences, including ruminant plasma coagulation, b-toxin, staphylokinase, and crystal violet growth reaction, allowing to subdivide it into ecological variants, or ecovars, which are delineated among human, poultry, or ruminant host associations. This method has been widely used to type S. aureus of bovine origin (Isigidi et al., 1992, Myllys et al., 1997), as it is usually inexpensive and easily applicable, given the workability of all tests, and it generates data that is simple to record and interpret (Aarestrup et al., 1995). Biotyping may give an indication of the origin of contamination, as the biotype correlates well with the animal host (Devriese, 1984). According to this Devriese’s biotyping system, strains isolated from bovine were classified in biotype C. However, biotyping has only limited utility in epidemiological typing, since it is not effective at grouping outbreak-related strains of S. aureus (Myllys et al., 1997), and its discriminatory power is relatively low compared to other typing methods (Sommerhäuser et al., 2003). When used in an outbreak situation, the main disadvantage of biotyping is the high proportion of untypable isolates (Aarestrup et al., 1995, Myllys et al., 1997).

2.1.3. Serotyping

Serotyping allows differentiation of isolates within the same species, and demonstrates antigenic variability as it uses a series of antibodies to detect antigens on the surface of bacteria. The original serotyping scheme to characterize staphylococci of bovine origin was developed by White et al. (1962). International epidemiological studies have revealed the existence of 11 capsular polysaccharide (CP) serotypes (Poutrel et al., 1988, Tollersrud et al., 2000b). CP5, CP8, and serotype 336 are among the most predominant serotypes in S. aureus isolates from bovine infections (Gogoi-Tiwari et al., 2015, Guidry et al., 1998), and are routinely used for S. aureus capsular serotyping. There seems to be a greater variation in the distribution of CP among these isolates from different geographic regions (El-Sayed et al., 2017). The advantages of the serological method are its greater technical simplicity and the smaller number of untypable strains (White et al., 1962). But it is normally inadequate as a single typing method for epidemiological purposes, for several reasons; it has very low discriminatory power (Guidry et al., 1998, Tollersrud et al., 2000b), and many unrelated isolates belonging to a small number of capsular serotypes. In addition, CP5- and CP8-specific antibodies are necessary reagents for these assays, but the necessary antisera are not commercially available (O’Riordan and Lee, 2004).

2.1.4. Phage typing

Phage typing is based on the pattern of resistance or susceptibility to a certain set of phages. It is standardized by the International Subcommittee on Phage Typing of Staphylococci (Blair and Williams, 1961). In cattle, it is one of the oldest standard methods that has been widely used in the past for characterizing outbreaks of S. aureus (Aarestrup et al., 1997, Davidson, 1972, Smith, 1948d), despite a number of limitations, including lack of reproducibility of results, and low discriminatory power (Aarestrup et al., 1997, Zadoks et al., 2002). Today, phage typing has lost its position and is no longer used in an outbreak situation (Zadoks et al., 2002), because the existence of many nontypable S aureus strains (Blair and Williams, 1961, Su et al., 1999, Zadoks et al., 2002), labor-intensive procedural steps, and complex technical requirements (Aarestrup et al., 1997, Sabour et al., 2004, Zadoks et al., 2002). In addition, it becomes inadequate as a single typing method; however, its association with biotyping or ribotyping is considered an efficient combination for epidemiological purposes of S. aureus IMIs (Aarestrup et al., 1995, Aarestrup et al., 1997).

2.1.5. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE)

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE), also called isoenzyme typing (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018), is a technique that indexes allelic variation in sets of randomly selected genes of the bacterial chromosome based on the electrophoretic mobility of a wide range of intracellular enzymes (Fitzgerald, 2012, Kapur et al., 1995). Major progress in the understanding of the global epidemiology of S. aureus occurred after the development of MLEE (Fitzgerald et al., 1997), which has successfully linked outbreak isolates and classified them correctly. The application of the MLEE method in bovine S. aureus population studies has revealed the clonal nature of the population of this pathogen (Fitzgerald et al., 1997, Kapur et al., 1995, Tollersrud et al., 2000a). S. aureus isolates are generally typeable with good reproducibility, but its discriminatory power is relatively low (Fitzgerald et al., 1997), and interpretation of data is difficult (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). In addition, MLEE is time consuming and labor-intensive making it unpractical in routine outbreak investigations (Fitzgerald et al., 1997, Su et al., 1999).

2.1.6. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS)

MALDI-TOF MS distinguishes between microorganisms’protein peaks, and differentiates spectra or the signatures of cell extracts, and whole cells. This technique has allowed the direct identification of bacterial strains of the genus and species, which has represented a cost-effective alternative to classical phenotypic and biochemical assays. In cattle, it is recently used as an alternative tool for identification of mastitis pathogens including S. aureus (Alharbi et al., 2021, Barreiro et al., 2017, El-Ashker et al., 2015, Nonnemann et al., 2019, Schmidt et al., 2015, Shell et al., 2017) allowing for more detailed classification of this pathogen (Liu et al., 2020). Besides, it has the potential to become an efficient type of detection method for MRSA identification (Elbehiry et al., 2016). This method can directly be applied in large scale in milk samples, which it showed to be simple to implement, reliable and highly reproducible (Barreiro et al., 2017, Liu et al., 2020). It could analyze samples within a few minutes, and it does not need large amounts of diagnostic material for analysis (Barreiro et al., 2017, Shell et al., 2017). It is also reported to be able to discriminate MRSA from MSSA (Alharbi et al., 2021). However, nowadays, MAL-DI-TOF MS is not commonly used in epidemiological studies due to the lack of guidelines for its validity, sensitivity and performance (Kasela and Malm, 2018, Shell et al., 2017). Furthermore, it is often time-consuming and laborious. (Barreiro et al., 2017).

2.2. Molecular typing methods

Molecular typing allows a study of polymorphism at the level of DNA, which examine chromosomal, plasmid, or total genomic DNA using techniques with/without DNA amplification by PCR and those identifying conformational polymorphisms of nucleic acids. Such methods have several uses: to investigate outbreaks, to track transmission of S. aureus at the local and global level, and to understand the evolution of high virulence MRSA strains (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). The most common methods, with respect to their usage for S. aureus strains IMIs, are presented below. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the molecular typing methods for epidemiological and evolutionary studies of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine intramammary infections.

Abbreviations; R: Reproducibility; T: Typeability; DP: Discriminatory power; EU: Ease of use; TR: Time required; Int: Interpretation; HT: High throughput; NA: not available; RAPD‐PCR: Random amplification of polymorphic DNA; AFLP: Amplified fragment length polymorphism; PCR-RFLP: Restriction fragment length polymorphism; RS-PCR: Ribosomal spacer; agr: Accessory gene regulator; MLVA: Multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis; PFGE: Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis; MLST: Multi-locus sequence typing; spa: Staphylococcal protein A; SCCmec: Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec; WGS: Whole genome sequencing;

2.2.1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)- based typing methods

Amplification-based typing methods also referred to as PCR-based methods; include a multitude of schemes that use PCR with many applications (Matthews et al., 1994). These schemes include, but not limited, RAPD, agr system, AFLP, PCR-RFLP, RS-PCR, and MLVA. PCR-based methods have emerged as the most rapid and the simplest ways to characterize and type S. aureus, and they are effective for epidemiological investigations of bovine staphylococcal infections (Zadoks and Schukken, 2006). Such methods facilitate the rapid and easy testing of large numbers of strains at a relatively low cost, and with high reliability and differentiation power (Chakraborty et al., 2019), but also have several limitations (Ruppitsch, 2016).

2.2.1.1. Random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD‐PCR) typing

RAPD-PCR typing, also known as arbitrarily primed-PCR (AP-PCR) (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018), is based on the amplification of one or more primers and it produces a set of fingerprinting patterns of different sizes specific to each strain (Adzitey et al., 2013). This PCR-based method is being increasingly used to type this pathogen, especially during mastitis outbreaks (Fitzgerald et al., 1997, Gurjar et al., 2012, Morandi et al., 2010, Myllys et al., 1997, Pereira et al., 2002, Reinoso et al., 2004, Wang et al., 2015). When compared to other typing methods, RAPD has been found to be more discriminating than coa-RFLP (Morandi et al., 2010), MLEE, and ribotyping (Fitzgerald et al., 1997), but less discriminating than other tested approaches, such as spa typing and microarrays (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016), and MLVA (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016, Morandi et al., 2010). This procedure’s discriminatory power highly depends on the number of primers, so it can be improved by applying more primers (Myllys et al., 1997, Reinoso et al., 2004). While this method is quick and easy to apply (Fitzgerald et al., 1997, Gurjar et al., 2012, Myllys et al., 1997), it has limited reproducibility (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018, Myllys et al., 1997) and interpretation of data is difficult (Su et al., 1999).

2.2.1.2. Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP)

In AFLP analysis, genomic DNA is digested with one or more restriction enzymes, and then specific DNA fragments, termed adapters, are ligated to DNA and used as targets for PCR primers (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). This technique has been used to investigate the clonal relationships between different S. aureus strains from various sources including cattle (Boerema et al., 2006, Sakwinska et al., 2011, Salasia et al., 2011). It is cheap to perform, very reproducible, and rapid (Salasia et al., 2011), but it has lower discriminatory power compared to other molecular typing methods such PFGE; however, an AFLP technique such as PFGE appears to be a useful tool for distinguishing clonal relationships between S. aureus isolates (Boerema et al., 2006). Adding another enzyme may improve the discriminatory power of this approach, but the technique then becomes laborious and expensive (Boerema et al., 2006). Hence, it may be a useful add-on tool in epidemiological investigations of bovine mastitis by performing the analysis of a large number of isolates (Sakwinska et al., 2011, Salasia et al., 2011).

2.2.1.3. Restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) analysis

In the PCR-RFLP technique after PCR amplification, DNA fragments are separated by gel electrophoresis with one or several restriction enzymes. The PCR-RFLP approach has been found to be useful for epidemiological investigations of S. aureus strains of bovine mastitis and has the advantages of ease of use, rapidity, and high reproducibility (Hakimi Alni et al., 2018, Morandi et al., 2010). Coagulase (coa) and protein A (spa), two of the most powerful PCR-based typing methods, have been widely used and may represent an interesting alternative for typing S. aureus of bovine origin in diagnostic laboratories even in developing countries (Moon et al., 2007, Morandi et al., 2010). Detection of coa gene polymorphisms by PCR has proven to be a simple and effective method for typing S. aureus isolates and MRSA on the basis of sequence variations within the 3′-end coding region of the gene (Raimundo et al., 1999, Su et al., 1999). The 3′-end coding region of the coa gene contains a series of 81 bp tandem repeats, which differ among S. aureus isolates in the number and location of AluI restriction sites (Chmagh and Abd Al-Abbas, 2019, Effendi et al., 2019). AluI performs better than HaeIII in S. aureus typing, but both can be used for higher reliability and sufficient power in discrimination (Javid et al., 2018). Identification based on PCR-RFLP of the coa gene gave the same results as PFGE (Dendani Chadi et al., 2016), and was considered a simpler and more accurate typing method for epidemiological investigations of bovine mastitis (Dendani Chadi et al., 2016, Morandi et al., 2010). Although its discriminatory power has been found to be lower, PCR-RFLP compares well with other techniques, such as PFGE (Hata et al., 2010), RAPD (Morandi et al., 2010), and MLVA (Hata et al., 2010, Morandi et al., 2010).

2.2.1.4. Ribosomal spacer (RS)-PCR

RS-PCR requires a set of primers to amplify by PCR the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region (Fournier et al., 2008). The spacer region exhibits large degrees of variation in sequence and length at the genus and species levels. This method has been successfully applied to study the epidemiology of bovine S. aureus species isolated from IMIs in cows, which is highly accurate with a high resolution, and has a moderate cost (Adkins et al., 2016, Ben Said et al., 2016, Boss et al., 2016, Cremonesi et al., 2015, Fournier et al., 2008, Graber et al., 2013, Graber, 2016; Monistero et al., 2018). Several studies performed RS-PCR to genotype S. aureus strains isolated from bovine milk, and showed a great genotypic variety, differing in their contagiousness (Boss et al., 2016, Cremonesi et al., 2015, Fournier et al., 2008), and are characterized by different epidemiological and clinical properties. Compared to spa typing and MLST, RS-PCR does not require DNA sequencing, which considerably simplifies the analysis and allows a high throughput (Ben Said et al., 2016, Boss et al., 2016, Graber, 2016). RS-PCR typing is well suited for routine purposes (Graber, 2016), and its use alone is sufficient to study the epidemiology of bovine S. aureus, despite its lower discriminatory power compared to PFGE and spa typing, since it was noted that RS-PCR failed to distinguish isolates with minor genetic differences (Adkins et al., 2016, Boss et al., 2016, Cremonesi et al., 2015).

2.2.1.5. Accessory gene regulator (agr) typing

In S. aureus, the agr globally controls the expression of many genes that code for the expression of exoproteins and cell-wall proteins (Kroning et al., 2018, Mitra et al., 2013), which exhibits highly conserved and hypervariable regions among S. aureus strains (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). In order to define agr types, the sequence of this hyperactive variable segment can be used as a target for PCR amplification (Krawczyk and Kur, 2018). There are four agr groups (agr type I, II, III and IV), which were first described by Ji et al. (1997). Several studies have revealed that the majority of S. aureus isolates, including MRSA of bovine origin belong to agr group I (Bardiau et al., 2016, Budd et al., 2015, Chu et al., 2013, Khemiri et al., 2018, Klibi et al., 2018, Kroning et al., 2018, Rossi et al., 2019, Schmidt et al., 2017). The determination of agr groups could be considered an effective approach for molecular tracking of S. aureus infections, and it might allow the assessment of a possible relationship between agr groups and the occurrence of virulence genes, and different clonal lineages (Bonsaglia et al., 2018, Mitra et al., 2013, Mohsenzadeh et al., 2015). The test provides a rapid, specific, and efficient tool for evaluating clinical isolates of this pathogen within a reasonable time frame and at an acceptable cost for use in routine laboratories (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018).

2.2.1.6. Multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA)

The use of an MLVA scheme was applied for the first time to type S. aureus in 2003 by Sabat et al. (2003), in which study five VNTR loci (sdr, clfA, clfB, ssp, and spa) were used. Several MLVA schemes have since been developed (Bergonier et al., 2014, Ikawaty et al., 2009, Morandi et al., 2010, Sobral et al., 2012, Van Duijkeren et al., 2014). MLVA is a high-throughput genotyping method for determining genetic diversity and identifying the evolution and emergence of host-adapted or udder-adapted clones (Bergonier et al., 2014, Sobral et al., 2012). With PFGE, MLST, and spa typing, MLVA is currently used for local and international large-scale analysis of molecular epidemiology of S. aureus and MRSA isolates (Bergonier et al., 2014, Hata et al., 2010, Sobral et al., 2012, Van Duijkeren et al., 2014) that have demonstrated comparatively high discriminatory power. MLVA was shown to be highly discriminant compared to MLST and spa typing, whereas its discriminatory power was found to be lower than but comparable with PFGE (Hata et al., 2010, Ikawaty et al., 2009) and microarray analysis (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016). MLVA has also proven to be more powerful compared to coa-PCR- RFLP (Hata et al., 2010) and RAPD-PCR (Morandi et al., 2010, Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016). Moreover, MLVA is a rapid, highly discriminatory, inexpensive, and easy to interpret method, which makes it applicable for molecular typing in veterinary settings in many laboratories (Bergonier et al., 2014, Ikawaty et al., 2009, Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016). Additionally, MLVA is characterized by its interlaboratory reproducibility, allowing for the development of international databases (Bergonier et al., 2014). Despite the publication of multiple schemes, there is still no standard methodology or nomenclature. In addition, the limitations of MLVA appear in highly conserved genomes, wherein DNA polymorphisms may not suffice to exhibit alleles in limited sequence targets (Stefani et al., 2012).

2.2.2. Restriction enzyme-based assays

2.2.2.1. Ribotyping

Ribotyping, or rRNA gene restriction pattern analysis, is a variant of the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) assay which is based on differences in the genes encoding the 16S, and 23S rRNA and flanking DNA (El-Sayed et al., 2017, van Belkum et al., 2007). EcoRI is one of the most frequently used endonucleases in this technique, because it produces more bands and types than HindIII (Aarestrup et al., 1995, Buzzola et al., 2001). Ribotyping constitutes a valuable tool for evaluating the clonal relationships between S. aureus isolates of bovine origin (Aarestrup et al., 1995, Myllys et al., 1997), with a high discriminatory index compared to biotyping, phage typing, and antibiogram typing (Aarestrup et al., 1995, Pereira et al., 2002). This technique has demonstrated considerable genetic heterogeneity within the S. aureus species and wide spread of some clones throughout different areas and guests (Aarestrup et al., 1997, Fitzgerald et al., 1997, Zhang et al., 2012). While this method is reproducible and less prone to variation (Duarte et al., 2015, Pereira et al., 2002), its discriminatory capacity is less satisfactory compared to PFGE (Buzzola et al., 2001, Fitzgerald et al., 1997), and RAPD (Myllys et al., 1997). It is based on the conserved nature of the probe-ribosomal genes, however, this factor can be optimized by the use of a wide range of restriction enzymes (Buzzola et al., 2001, Myllys et al., 1997). In addition, ribotyping is time consuming and expensive, and it requires special equipment (Su et al., 1999).

2.2.2.2. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

The PFGE technique is developed by Schwarz and Cantor (1984). It is based on the restriction endonuclease of bacterial genomic DNA, which detects only a few digestion sites in the chromosome, thus generating large DNA fragments (van Belkum et al., 2007). These are then separated by pulsed-field electrophoresis with periodic changes in the orientation of the electric field through the gel (He et al., 2014). As far as cattle are concerned, PFGE has been widely applied in epidemiological investigations of bovine mastitis outbreaks (Buzzola et al., 2001, Dendani Chadi et al., 2010, Jørgensen et al., 2005, Kroning et al., 2018, Rossi et al., 2019, Sabour et al., 2004, Said et al., 2010) and MRSA clones (Feltrin et al., 2016; Nam et al., 2011, Tavakol et al., 2012). PFGE is now recognized as being the most discriminatory and reproducible method, and it has therefore become a widely applied method for comparative typing, compared to most molecular methods such as MLVA (Adkins et al., 2016, Ikawaty et al., 2009), spa typing (Adkins et al., 2016, Hata et al., 2010, Ikawaty et al., 2009, Mitra et al., 2013, Said et al., 2010), MLST (McMillan et al., 2016, Rabello et al., 2007, Smith et al., 2005a, Srednik et al., 2018), ribotyping (Buzzola et al., 2001, Cremonesi et al., 2015), coa-RFLP (Dendani Chadi et al., 2016; Hata et al., 2010), phage typing (Sabour et al., 2004, Zadoks et al., 2002), AFLP (Boerema et al., 2006), and RS-PCR (Adkins et al., 2016, Cremonesi et al., 2015). This is one of the reasons why PFGE is often regarded as the gold standard in S. aureus typing and has therefore become a widely applied method for comparative typing methods (Castelani et al., 2013, Lisowska-Łysiak et al., 2018, Ji, 2020). However, PFGE has cons as well, which can be summarized as follows: (1) the long interval before results can be obtained, (2) technical difficulty, (3) labor-intensive protocols, (4) the cost of reagents, and (5) specialized equipment (Dendani Chadi et al., 2010, Zadoks and Schukken, 2006). In the case of large collections of isolates, PFGE is susceptible to failure in interpretations despite the limited number of gel bands it generates. Additionally, it is difficult to standardize and compare different laboratories’ PFGE results (Ikawaty et al., 2009, Szabó, 2014), making it unsuitable for international comparisons (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). However, in these situations, the Bionumerics software which can be used for digital analysis of the bands, allows PFGE profiles to be normalized and the images to be matched within and between different laboratories (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018) In addition, PFGE is incapable of identifying LA-MRSA strains and establishing a precise database (Hata et al., 2010). Despite SmaI PFGE has been widely and successfully used for bovine S. aureus outbreak analysis (Sabour et al., 2004, Zadoks et al., 2002), most bovine MRSA isolates belonging to ST398 were untypable by this enzyme PFGE (Haran et al., 2012, Kroning et al., 2018).

2.2.3. Sequence-based typing methods of bovine Staphylococcus. Aureus

DNA-sequence-based typing methods such as spa typing and MLST are the most advanced and accurate techniques currently available for species-/subspecies-/strain-level characterization of microorganisms, including S. aureus (Chakraborty et al., 2019, Ruppitsch, 2016). The former is based on DNA sequencing of the variable spacer region of the staphylococcal spa gene, whereas the latter requires the sequencing of 7 housekeeping genes (Boss et al., 2016). They characterized by a universal and worldwide nomenclature and by organized databases and networks. These techniques enable the determination of a precise and a refined population structure (Li et al., 2017, Peton and Le Loir, 2014), which single or multiple genes can or must be analyzed for strain characterization. For the investigation of global epidemiology and the clonal evolution of MRSA, a system that looks at slower accumulating genetic variation is required.spa typing (Hasman et al., 2010) and MLST (Smith et al., 2005a), can meet this requirement and are widely used for this purpose.

2.2.3.1. Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST)

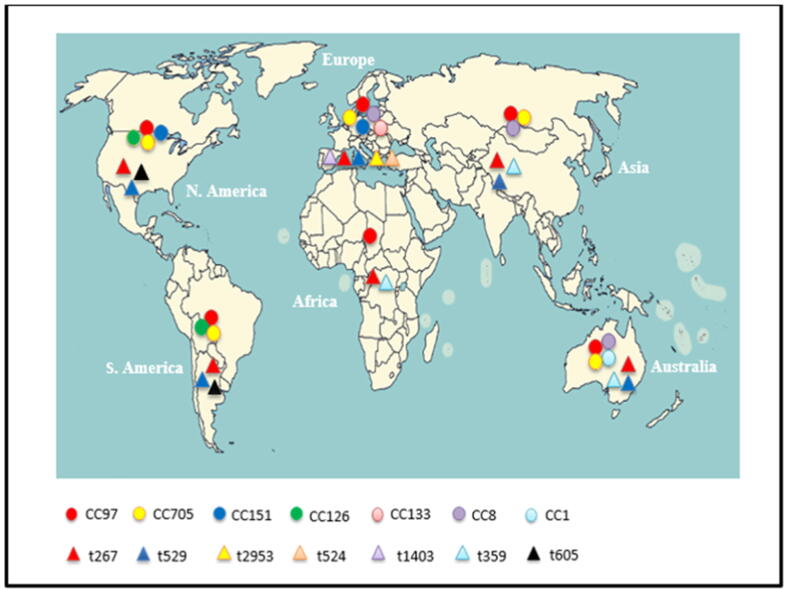

MLST differentiates S. aureus isolates on the basis of DNA sequences in seven relatively conserved housekeeping genes (loci) that encode essential proteins: carbamate kinase (arcC), shikimate dehydrogenase (aroE), glycerol kinase (glpF), guanylate kinase (gmk), phosphate acetyltransferase (pta), triosephosphate isomerase (tpi), and acetyl coenzyme A acetyltransferase (yqiL) (Boss et al., 2016, Smith et al., 2005a). The current terminology used to describe lineages is based on MLST clonal complexes (CCs), and allele number and sequence types (STs), are assigned by using the S. aureus MLST standardized nomenclature database (https://s.aureus.mlst.net) with the software package BURST (Zhang et al., 2016). MLST has been widely used in genotyping for epidemiological (Ben Said et al., 2016, Boss et al., 2016, Budd et al., 2015, Cremonesi et al., 2015, Khemiri et al., 2018, Kwon et al., 2005, Li et al., 2017, McMillan et al., 2016, Rabello et al., 2007, Silva et al., 2014, Schmidt et al., 2017, Smith et al., 2005a, Smith et al., 2005b), and evolutionary studies of bovine MRSA (Aqib et al., 2018, Basanisi et al., 2017, Silva et al., 2014, Tavakol et al., 2012; Tegegne et al., 2019; Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2015, Yi et al., 2018). MLST has been proven to be an excellent method for long-term global studies of S. aureus (Holmes and Zadoks, 2011). Using this method, it is possible to demonstrate broad, international spread of specific clones as causative agents of mastitis, which are distributed worldwide; these include clonal complex (CC) 1, CC5, CC8, CC9, CC20, CC50, CC71, CC97, CC126, CC133, CC151, CC398, CC479, and CC705 (Table 3). Of these, MLST types ST97/CC97 and ST705/CC705 have emerged as the dominant lineages isolated from bovine milk worldwide (Table 3). Despite some differences between continents, the most frequent CCs worldwide were; CC97 in Africa, CC97, CC151, CC133, CC705, and CC8 in Europe, CC97, CC1, CC8, and CC705 in Australia, CC97, CC705, and CC8 in Asia, and CC97, CC705, and CC126 in America. CC5, CC9, CC20, CC504, CC71, CC479, and CC398 were only reported in specific countries (Table 3, Fig. 1). Within these MLST types, several lineages have evolved independently over time in different geographic locations. Interestingly, lineage ST97 was previously described in humans at low frequency, and its isolation from close human contact suggests zoonotic transfer (Akkou et al., 2018, Butaye et al., 2016, Cremonesi et al., 2015, Schmidt et al., 2017). LA-MRSA of lineage ST398 in cows has spread worldwide and is the most predominant CC in Europe and the United States, whereas ST9 dominates in many Asian countries (Butaye et al., 2016, Li et al., 2017, Yi et al., 2018). LA-MRSA of lineage ST398 has emerged also in humans indicating a worldwide clonal lineage (Holmes and Zadoks, 2011, Silva et al., 2014). This clone causing bovine mastitis has been described worldwide—in the United States (Haran et al., 2012), the Netherlands (Tavakol et al., 2012), Brazil (Silva et al., 2014), Belgium (Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010), the Czech Republic (Tegegne et al., 2019), Germany (Feßler et al., 2010; Kadlec et al., 2019), Portugal (Couto et al., 2015), France and Switzerland (Sakwinska et al., 2011), the United Kingdom and Denmark (Fisher and Paterson, 2020, Paterson et al., 2012), Italy (Basanisi et al., 2017), and China (Wang et al., 2015, Yi et al., 2018)—although its prevalence varies widely from country to country. The major advantages of MLST are that it provides global epidemiological data, which can be very easily exchanged and compared between laboratories and/or entered into common databases over the Internet (https://www.mlst.net). Therefore, comparisons across herds, countries, and host species also became much easier (Zadoks et al., 2011). It is generally agreed that at present, MLST is the method that gives the most reliable information about the phylogenetic clustering of S. aureus isolates (Hasman et al., 2010). It also offers the advantages of being highly reproducible and typeable, making it an excellent tool for global comparisons of population structures (McMillan et al., 2016, Smith et al., 2005a, Smith et al., 2005b). It has been shown that MLST, which uses genetic variation that accumulates very slowly in seven housekeeping genes, has proven very useful for long-term macroepidemiology and evolutionary studies (Koreen et al., 2004; Stefani et al., 2012). The disadvantage of MLST is that it uses only seven loci, which limits the ability to detect some switches (Szabó, 2014). Moreover, in MLST sequencing of all PCR products of seven different genomic loci is the major drawback of this technique, which is associated with low throughput (Silva et al., 2014, Smith et al., 2005a, Szabó, 2014), and high cost (Boss et al., 2016, Ji, 2020; Ruppitsch, 2016; Schmidt et al., 2017; Stefani et al., 2012). Overall, MLST is less useful for outbreak investigations due to its limited discriminatory power compared to other typing methods, such as PFGE, MLVA, and spa typing (Boss et al., 2016, Hata et al., 2010, Hasman et al., 2010, McMillan et al., 2016, Rabello et al., 2007), since outbreak sittings require; high levels of discrimination to differentiate between closely related strains (O'Hara et al., 2016), rapid throughput of samples (Stefani et al., 2012), and rapid accumulation of genetic variation. This is particularly true for spa typing and PFGE (Koreen et al., 2004).

Table 3.

The most prevalent clonal lineages of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine intramammary infections across the world.

| Country/Continent | S. aureus (no. of isolates) | MLST ST/CC | Spa-type | Molecular methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Africa | MSSA (16) | CC97 / ST352/ ST2992 | t15533/ t15539 | Spa-MLST, PFGE, agr | Schmidt et al., 2017 |

| Ethiopia | S. aureus (76) | ST 97/ ST4550 | t042 / t15786 | spa, MLST | Mekonnen et al.,2018 |

| Algeria | S. aureus (9) | CC97 | t359 /t267 | spa, Microarray | Zaatout et al., 2019 |

| Algeria | MSSA (67) | CC97 /CC22 | t267/ t223 | spa, MLST, Microarray | Akkou et al., 2018 |

| Tunisia | MSSA (26) | CC398/ ST398 | t267 | agr,PFGE, spa, SCCmec, MLST | Khemiri et al., 2018 |

| MRSA(1) | CC97/ ST97 | t267 | |||

| Tunisia | MSSA (12) MRSA(3) | ST97/ ST4120 ST4114 / ST4120 | t267t10381// t267 | MLST, agr, spa | Klibi et al., 2018 |

| Tunisia | MSSA (43) | CC97/ ST97/ ST2826 CC1/ ST1 | t2421/ t521/t2112 | RS-PCR, spa, MLST | Ben Said et al., 2016 |

| Egypt | MRSA (12) MSSA (30) | CC97/ CC1 | t267/t127 | DNA-microarray spa typing. | El-Ashker et al., 2020 |

| Rwanda | MSSA (43) | CC97 / ST97/CC3591 | t1236 /t10103 | Microarray, MLST WGS | Antók et al., 2020 |

| Brazil | MSSA (62) | CC126/ ST126/ CC97 | ND | PFGE- MLST | Rabello et al., 2007 |

| Brazil | MSSA (56) | CC126 / ST126/ CC1/ST1/ CC133/ST133 | t605 / t127 | spa, agr, MLST | Silva et al., 2014 |

| Brazil | MSSA (2 8 5) | CC126/ST126/CC1/ST1 | t605 / t127 | MLST-agr-spa- PFGE | Bonsaglia et al., 2018 |

| Brazil | S. aureus (1 1 6) | CC126 /ST126/CC133/ ST133 | t605/ t10856 | PFGE, spa, MLST | Rossi et al., 2019 |

| Canada | MSSA (26) | ST97 | t359/t267/ t529/t605 | PFGE, spa | Said et al., 2010 |

| Canada | S. aureus (1 1 9) | CC151 /ST151/ST351/ CC97 / ST352/2187/CC126/ST126/2270 | t529/ t2445/ t267/ t359/ t605 | WGS, spa, MLST | Naushad et al., 2020 |

| Canada | S. aureus (1 5 0) | ND | t529 /t267/ t13401/t359/ t605 | spa | Veh et al., 2015 |

| Argentina | MSSA (2 2 9) | ST 97 / ST705/ ST746 | ND | PFGE-MLST | Srednik et al., 2018 |

| Colombia | S. aureus (1) | CC97/ ST126 | ND | WGS | Torres et al., 2020 |

| USA and Chile | MSSA(2 5 9) | CC97/ ST97/ ST124 /ST126 | ND | MLST | Smith et al., 2005a |

| Japan | MSSA (3 5 9) MRSA (4) | CC705/ ST705/ ST352/ CC97 /ST97/CC5/ST5/ST89 | t529/ t189/ t203/t224/ t267/ t359/t002/ t375 | MLVA, coa PCR-RFLP, MLST, PFGE, spa | Hata et al., 2010 |

| Country/Continent | S. aureus (no. of isolates) | MLST CC/ST | Spa-type | Molecular methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | S. aureus (62) | CC8/ ST630/ CC97/ ST97/ ST50 ST705/ ST398 | t529 / t2196/ t518 | MALDI-TOF-MS, agr, spa, MLST | Liu et al., 2020 |

| China | MSSA (1 9 8) MRSA (14) | CC97/ ST97/ CC520/ST520/ CC188/ ST188/ CC398/ ST398 CC9/ ST9 | t267/ t359/ t9303/ t189/ t034 t899 | MLST, SCCmec typing, PFGE, spa | Li et al., 2017 |

| China | S. aureus (56) | ND | t267/ t730/ t518 | spa | Zhang et al., 2020 |

| Iran | MSSA (23) MRSA (2) | CC5 / ST97 / ST352 / ST97 CC398 / ST291 | t267 / t521/ t527 t937 | Spa –MLST-SCCmec | Dastmalchi-Saei and Panah, 2020 |

| India | S. aureus (1 7 3) | ND | t267/t359/ t6877 | Spa, agr, PFGE | Mitra et al., 2013 |

| Russia | S. aureus (21) | CC97 | ND | WGS-MLST | Fursova et al., 2020 |

| Taiwan | S. aureus (10) | ST188/ ST705 | ND | agr-MLST-PFGE | Chu et al., 2013 |

| Australia | S. aureus (13) | CC97/ ST97/CC705/ ST705 CC1/ST1/ CC5/ ST5/ CC8/ ST8 | ND | PFGE-MLST | McMillan et al., 2016 |

| Australia | S. aureus (1 6 6 ) | CC97 /ST352/ ST97/ CC705/ ST705/ST81/ CC1/ ST1 | t189/ t224/ t237/ t267/ t359/ t529 | MLST-spa-WGS | O'Dea et al., 2020 |

| Austria | S. aureus (21) | CC97 /ST352 | ND | WGS, MALDI-TOF-MS | Marbach et al., 2019 |

| Austria | MSSA (58) | CC9 / ST9/ CC705/ ST504/ CC151 | t1939/ t529 | MLST, spa | Grunert et al., 2018 |

| France | S. aureus (1 1 8) | CC97/ CC133 / CC151/ CC479 | ND | MLVA,spa, MLST | Bergonier et al., 2014 |

| Germany | MSSA (1 8 9) MRSA (4) | CC151/ CC479/CC133/ CC97 CC398 | ND | Microarray | Schlotter et al., 2012 |

| Germany | S. aureus (70) | CC133 / ST133/ ST2821/ CC151/ ST504/ ST151/ CC97/ ST97 | t1403 / t529 / t521 | MLST, spa | Sheet et al., 2019 |

| Switzerland | S. aureus (58) | CC705 / ST504/ ST151/CC97/ ST352/ST71/ CC20 / ST389 | t529 / t267 / t359/t524 /t164 | MALDI-TOF-MS, Microarray, MLST, spa | Käppeli et al., 2019 |

| Switzerland | S. aureus (78) | CC151/ CC97/CC8/CC479 /CC20 | ND | Microarray | Moser et al., 2013 |

| Switzerland and France | S. aureus (3 4 3) | CC8 /CC151/ CC20 / CC97 | t2953/t529/t164/ t524 | AFLP-spa, MLST | Sakwinska et al., 2011 |

| Denmark | MSSA(1 1 2) | CC50 /ST50/ CC97 /ST97/CC151/ ST151/ CC133/ ST133/CC9/ST9 | t518/ t524/ t529/ t1403 | spa- MLST-PFGE | Hasman et al., 2010 |

| Denmark | S. aureus (1 5 7) | ST151/ ST133/ ST3891/ST97 ST479/ ST50 | t529 / t519 /t1403 | WGS-MLST-spa | Ronco et al., 2018 |

| Country/Continent | S. aureus (no. of isolates) | MLST CC/ST | Spa-type | Molecular methods | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | S. aureus (1 1 7) | CC1/ST133/ST132/ CC3/ ST130 | ND | PFGE, MLST | Jørgensen et al., 2005 |

| Ireland | S. aureus (1 2 6) | CC97/ ST71/ ST97/ CC151/ ST151/ ST136 | ND | Microarray–agr-MLST-WGS | Budd et al., 2015 |

| Netherlands | S. aureus (85) | CC97/ ST151/ CC705/ ST504/ ST479/ ST71 | t529/ t543/ t524 | MLVA, PFGE, spa MLST | Ikawaty et al., 2009 |

| UK | S. aureus (1 9 1) | CC97/ ST116/ ST118 | ND | MLST | Smith et al., 2005b |

| UK | S. aureus (37) | CC151/ ST151/ CC133/ ST771/ CC97/ ST97 | ND | Microarray | Sung et al., 2008 |

| Italy | S. aureus (8) | ST 126 | t605 | MLST, spa, Microarray | Snel et al., 2015 |

| Italy | S. aureus (54) | CC8/ ST8/ CC398/ ST398/ CC126/ ST126/ CC5/ ST5/ CC97/ ST97/ CC133/ CC705 | t2953/ t899/ t605/ t1730 | Ribotyping, PFGE, MLST, spa, RS-PCR | Cremonesi et al., 2015 |

| USA-Spain | S. aureus (52) | CC97/ ST97/ ST71/ CC126 / ST126/CC133/ ST133 | ND | Spa, MLST, agr | Smyth et al., 2009 |

| Sweden | CC133/ ST133 | Smyth et al., 2009 | |||

| Ireland | CC97/ ST97/ ST71/ CC705/ ST151/ CC133/ ST133/ | ND | Smyth et al., 2009 | ||

| 12 European countries | S. aureus (2 8 1) | CC8/ ST8/ CC705/ ST ST504/ CC97/ ST97 | t2953/ t024/ t529/t1403/ t524/ t267 | RS- PCR, spa MLST | Boss et al., 2016 |

| 11 European countries | S. aureus (2 7 6) | CC151/ CC97/ CC479 / CC398 | ND | WGS | Hoekstra et al., 2020 |

Abbreviations: Clonal complex: (CC); Sequence type: (ST); spa type: (t); Not done: ND;

Fig. 1.

Major Clonal lineages (Clonal complex [CC] and spa types[t]) among different continents.

2.2.3.2. Staphylococcal protein A (spa) typing

The spa typing method is based on two techniques: PCR amplification and sequencing of short sequence repeats (SSRs) from the polymorphic X region of the protein A gene (spa) (Ji, 2020). Deletion and duplication of the repetitive units coupled with point mutations generate the diversity of SSR regions (Krawczyk and Kur, 2018), which are well illustrated at https://www.seqnet.org. These regions are highly polymorphous, and are therefore potentially suitable for discrimination in outbreak investigations. The spa gene has been used as an epidemiological target to identify the genetic lineages of S. aureus typing of bovine IMIs (Ben Said et al., 2016, Bonsaglia et al., 2018, Hasman et al., 2010, Holmes and Zadoks, 2011, Käppeli et al., 2019, Klibi et al., 2018, Mitra et al., 2013, Said et al., 2010, Veh et al., 2015). It is also the most widely used method for local and global short-term epidemiological studies (Boss et al., 2016; Nam et al., 2011; Tavakol et al., 2012, Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010, Yi et al., 2018), since spa typing was capable of simultaneously indexing genetic variations that accumulate both rapidly and slowly (Koreen et al., 2004). Some prevalent spa types are widely distributed worldwide. In particular, t267 and t529 represent the most common widespread bovine lineages and are largely responsible for bovine mastitis cases in some countries among different continent (Table 3). The most prevalent spa types were t267, t529, t2953, t524, and t1403 in Europe, t267 and t529 in Asia, t267 and t359 in Africa, t267 and t529 in America and t267, t529 and t359 in Australia (Fig. 1, Table 3). Many other spa types were only reported in specific countries such as t127 and t605 that are prevalent in Brazilian, Canadian and Italian herds (Table 3). Regarding the clonal lineages of MRSA, spa types t011 and t034 belong to the CC398 MRSA clone isolates from bovine sources (Boss et al., 2016; Feßler et al., 2010; Haran et al., 2012, Li et al., 2017, Kreausukon et al., 2012; Tegegne et al., 2019; Tenhagen et al., 2014, Van Duijkeren et al., 2014, Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010, Yi et al., 2018). The main advantages of this typing method are its excellent interlaboratory reproducibility, rapidity, standard nomenclature, and portability (Bonsaglia et al., 2018, Hasman et al., 2010, Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016). Moreover, spa typing is an easy technique, and cheaper than MLST or PFGE (Bonsaglia et al., 2018), and it can be applied in geographically distant laboratories by adopting the different spa types circulating in diverse areas (Krawczyk and Kur, 2018). Additionally, this is a high-throughput method and simultaneously provides robust evidence for phylogenetic relationships (Hasman et al., 2010, Mitra et al., 2013; Stefani et al., 2012), since spa types are normally associated with specific MLST types (Bonsaglia et al., 2018, Hasman et al., 2010, Schmidt et al., 2017). spa typing based on the sequencing of only a single PCR amplicon, exhibits excellent discriminatory power and high throughput, compared to MLST (Hasman et al., 2010, Käppeli et al., 2019, Smyth et al., 2009). However, its disadvantages lie in the low discriminatory power compared to PFGE (Adkins et al., 2016, Hata et al., 2010, Ikawaty et al., 2009), and the limited resolving power, for it poorly distinguishes outbreak isolates from background ones, which is relevant in a local epidemic situation (Adkins et al., 2016, Hata et al., 2010, Ikawaty et al., 2009, Mitra et al., 2013). In addition, spa typing is incapable of identifying new lineages due to inherent homoplasia and variable evolutionary rate of spa alleles and clustering based on spa data that is complex (Sobral et al., 2012).

2.2.4. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing

SCCmec elements are genomic islands integrated into the chromosome of MRSA that carries mecA/mecC, coding for penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a), a transpeptidase conferring resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (Käppeli et al., 2019). SCCmec elements include the mec-gene complex (mec), which is responsible for the resistance to methicillin, and the ccr-gene complex (ccr), which is charged with the integration and excision of the cassette in the bacterial genome (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). SCCmec uses multiplex PCR (mPCR) to identify the structure of the mec complex and the availability of the different ccr gene complexes (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). To date, 13 structural types of SCCmec have been found (Lakhundi and Zhang, 2018). SCCmec typing is essential for the characterization of MRSA clones in epidemiological studies, and plays a core role in antimicrobial resistance characteristics (Feßler et al., 2010; Kwon et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2020; Nam et al., 2011, Vanderhaeghen et al., 2010, Wang et al., 2015). It has become popular for epidemiologic and evolutionary analysis of LA-MRSA strains (Dastmalchi-Saei and Panah, 2020; Fisher and Paterson, 2020; Pérez et al., 2020, Tavakol et al., 2012) that are mostly associated with a specific SCCmec type (Li et al., 2017). Accurately identifying the SCCmec type hosted in S. aureus is useful not only for epidemiological purposes, but also for defining the origin of staphylococci (Carretto et al., 2018). The most frequent SCCmec in bovine mastitis cases are types IV and V (Butaye et al., 2016; Feltrin et al., 2016; Havaei et al., 2015, Kwon et al., 2005). In addition, untypable cassettes and SCCmec type XI, containing mecC, have also been found in bovine isolates (Butaye et al., 2016, Li et al., 2017). This system is widely used, and it tends to be reliable and complete (Carretto et al., 2018). Unfortunately, its main disadvantages are the complexity of the typing system, since the SCCmec region is variable and new types are constantly being defined, and the need for different mPCR (Szabó, 2014). SCCmec genotyping is limited by the fact that the isolate must be MRSA, takes time and requires qualified personnel, which may not be feasible for routine purposes (Carretto et al., 2018).

2.2.5. Whole genome sequencing (WGS)

WGS provides the opportunity to reveal the structure of the genome and the genetic content of microorganisms, and it allows the comparison of the genetic differences between organisms down to the resolution of a single base pair. WGS has become more accessible and affordable as a genotyping tool (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016). In cattle, it is becoming more common to use it in the study of IMIs (Antók et al., 2020, Budd et al., 2015, Fisher and Paterson, 2020, Fursova et al., 2020, Hoekstra et al., 2020, Marbach et al., 2019, McMillan et al., 2016, Naushad et al., 2020, Ronco et al., 2018, Torres et al., 2020). These investigations have led to better knowledge of the population structure of S. aureus, the origin of antibiotic-resistant strains, the genetic basis of virulence, and the emergence and spread of lineages from local and global bovine populations (Fursova et al., 2020, Naushad et al., 2020). With technological advances, the application of WGS has gained traction during the past decade, and it has improved the accessibility and cost-effectiveness of high-throughput sequencing, providing in the process a huge amount of data and the greatest discriminatory power in identifying transmission events during outbreaks of S. aureus bovine (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016, Schmidt et al., 2017). At present however, this method requires time, is associated with a high cost of analysis, and involves a very high initial investment in hardware and software, which are the limiting factors for the use of this technique in local veterinary diagnostic centers and routine surveillance (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016, Schmidt et al., 2017). In addition, the interpretation of its data requires experience and defined criteria to assess the genetic relationships between strains, since the results may otherwise not be conclusive (Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016).

2.2.6. DNA microarray hybridization

Microarray technology was first described in 1995 by Schena et al. (1995), and the number of published research studies using this technology has continued to grow since then. This technology is based on the hybridization of hundreds of target genes loaded on to microarray chips, followed by visualization by exposure to sequence-complementary DNA probes conjugated with fluorescent or chemiluminescent stains (El-Sayed et al., 2017, Szabó, 2014). DNA microarray assay is an effective, highly accurate, high-performance, and reproducible tool (Lisowska-Łysiak et al., 2018) that is used to determine the presence of several hundred genes in an isolate of S. aureus, allowing a comprehensive analysis of the virulence properties, resistance determinants, and population structure of this pathogen (El-Ashker et al., 2015, Monecke et al., 2007). In cattle, this new method is becoming increasingly used to genotype pathogens that infect the mammary glands, offering additional features for epidemiological studies of S. aureus (Akkou et al., 2018, Antók et al., 2020, Käppeli et al., 2019, Monecke et al., 2007, Moser et al., 2013, Schlotter et al., 2012, Snel et al., 2015, Sung et al., 2008, Zaatout et al., 2019) and MRSA lineages (Budd et al., 2015; Feßler et al., 2010). Advantage of the microarray system is the possibility of automatically assigning the tested isolates to epidemic lineages. The data obtained can therefore be compared with current epidemiological reports on the CC/ST structure of S. aureus worldwide (Antók et al., 2020, Kosecka-Strojek et al., 2016). However, the use of the microarray assay is not without limitations: it is a technically complex and cost-consuming technology that is generally used in research laboratories (El-Sayed et al., 2017, Käppeli et al., 2019, Szabó, 2014). The biggest disadvantage is its ability to detect only known alleles of genes, so it is useless for detecting new single nucleotide mutations (Lisowska-Łysiak et al., 2018).

3. Conclusion

The different typing methods of S. aureus involved in bovine IMIs, do not meet all the performance and convenience criteria, requiring the use of alternative typing methods. MLVA is a faster and more available alternative to PFGE, and may be appropriate for investigations in veterinary settings. spa and SCCmec typing may be used that they are informative enough for outbreaks, and evolution. MLST is a good typing method for global epidemiological investigations, and is more suitable for defining lineages. However, it is not suitable for outbreak investigations. The use of different combinations of typing methods has provided a set of practical techniques, which has increased the index of discrimination and resulted in a useful subtyping scheme. Most importantly, WGS and DNA microarrays provide more information, so they can replace PFGE as the gold standard method, but their high cost and requirement of special laboratory equipment makes them hard to use in clinical veterinary medicine. Considering all data in these molecular epidemiologic and evolutionary analyses described, we found that adequate and accurate typing is of great concern. Therefore, many challenges must be overcome before these methods can move from the research stage to the routine veterinary laboratory setting with limited resources.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Dr. Marie-Anne Arcangioli, University of Lyon, VetAgro Sup, Campus Vétérinaire, Marcy l’Etoile, France for reading and correcting the manuscript.

Footnotes

Laboratory of Biodiversity and Pollution of Ecosystems.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Contributor Information

Zoubida Dendani Chadi, Email: z.dendani@hotmail.fr.

Loubna Dib, Email: dib_loubna_dz@yahoo.fr.

Fayçal Zeroual, Email: fayveto@gmail.com.

Ahmed Benakhla, Email: benakhlaahmed@gmail.com.

References

- Aarestrup F.M., Wegener H.C., Rosdahl V.T. Evaluation of phenotypic and genotypic methods for epidemiological typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bovine mastitis in Denmark. Vet. Microbiol. 1995;45(2-3):139–150. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(95)00043-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarestrup F.M., Wegener H.C., Jensen N.E., Jonsson O., Myllys V., Thorberg B.M., Waage S., Rosdahl V.T. A study of phage and ribotype patterns of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in the Nordic countries. Acta. Vet. Scand. 1997;38(3):243–252. doi: 10.1186/BF03548487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkins P.R.F., Middleton J.R., Fox L.K., Fenwick B.W. Comparison of virulence gene identification, ribosomal spacer PCR, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for typing of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from cases of subclinical bovine mastitis in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016;54(7):1871–1876. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03282-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzitey F., Huda N., Ali G.R.R. Molecular techniques for detecting and typing of bacteria, advantages and application to foodborne pathogens isolated from ducks. 3 Biotech. 2013;3(2):97–107. doi: 10.1007/s13205-012-0074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aires-de-Sousa M. MRSA among animals: current overview. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017;23:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkou M., Bouchiat C., Antri K., Bes M., Tristan A., Dauwalder O., Martins-Simoes P., Rasigade J.-P., Etienne J., Vandenesch F., Ramdani-Bouguessa N., Laurent F. New host shift from human to cows within Staphylococcus aureus involved in bovine mastitis and nasal carriage of animal's caretakers. Vet. Microbiol. 2018;223:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aqib A.I., Ijaz M., Farooqi S.H., Ahmed R., Shoaib M., Ali M.M., Mehmood K., Zhang H. Emerging discrepancies in conventional and molecular epidemiology of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine milk. Microb. Pathog. 2018;116:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi A., Al-Dubaib M., Elhassan M.A.S., Elbehiry A. Comparison of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with phenotypic methods for identification and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus causing mastitis. Trop Biomed. 2021;38:9–24. doi: 10.47665/tb.38.2.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzohairy M.A. Colonization and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of methicillin resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among farm animals in Saudi Arabia. Afric. J. Bacteriol. Res. 2011;3:63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Antók F.I., Mayrhofer R., Marbach H., Masengesho J.C., Keinprecht H., Nyirimbuga V., Fischer O., Lepuschitz S., Ruppitsch W., Ehling-Schulz M., Feßler A.T., Schwarz S., Monecke S., Ehricht R., Grunert T., Spergser J., Loncaric I. Characterization of antibiotic and biocide resistance genes and virulence factors of Staphylococcus species associated with bovine mastitis in Rwanda. Antibiotics. 2020;9(1):1. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics9010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardiau M., Caplin J., Detilleux J., Graber H., Moroni P., Taminiau B., Mainil J.G. Existence of two groups of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis based on biofilm formation, intracellular survival, capsular profile and agr-typing. Vet. Microbiol. 2016;185:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreiro J.R., Gonçalves J.L., Braga P.A.C., Dibbern A.G., Eberlin M.N., Veiga dos Santos M. Non-culture-based identification of mastitis-causing bacteria by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J. Dairy Sci. 2017;100(4):2928–2934. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basanisi M.G., La Bella G., Nobili G., Franconieri I., La Salandra G. Genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from milk and dairy products in South Italy. Food Microbiol. 2017;62:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Said M., Abbassi M.S., Bianchini V., Sghaier S., Cremonesi P., Romanò A., Gualdi V., Hassen A., Luini M.V. Genetic characterization and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine milk in Tunisia. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2016;63(6):473–481. doi: 10.1111/lam.12672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergonier D., Sobral D., Feßler A.T., Jacquet E., Gilbert F.B., Schwarz S., Treilles M., Bouloc P., Pourcel C., Vergnaud G. Staphylococcus aureus from 152 cases of bovine, ovine and caprine mastitis investigated by Multiple-locus variable number of tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) Vet. Res. 2014;45(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s13567-014-0097-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair J.E., Williams R.E.V. Phage typing of staphylococci. Bull. World Health Organ. 1961;24:771–784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerema J.A., Clemens R., Brightwell G. Evaluation of molecular methods to determine enterotoxigenic status and molecular genotype of bovine, ovine, human and food isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006;107(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsaglia E.C.R., Silva N.C.C., Rossi B.F., Camargo C.H., Dantas S.T.A., Langoni H., Guimarães F.F., Lima F.S., Fitzgerald J.R., Fernandes A., Rall V.L.M. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) isolated from milk of cows with subclinical mastitis. Microb. Pathog. 2018;124:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss R., Cosandey A., Luini M., Artursson K., Bardiau M., Breitenwieser F., Hehenberger E., Lam T.h., Mansfeld M., Michel A., Mösslacher G., Naskova J., Nelson S., Podpečan O., Raemy A., Ryan E., Salat O., Zangerl P., Steiner A., Graber H.U. Bovine Staphylococcus aureus: Subtyping, evolution, and zoonotic transfer. J. Dairy Sci. 2016;99(1):515–528. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd K.E., McCoy F., Monecke S., Cormican P., Mitchell J., Keane O.M., van Schaik W. Extensive genomic diversity among bovine-adapted Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for a genomic rearrangement within CC97. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butaye P., Argudín M.A., Smith T.C. Livestock-associated MRSA and its current evolution. Curr. Clin. Micro Rpt. 2016;3(1):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzola F.R., Quelle L., Gomez M.I., Catalano M., Steele-moore L., Berg D., Gentilini E., Denamiel G., Sordelli D.O. Genotypic analysis of Staphylococcus aureus from milk of dairy cows with mastitis in Argentina. Epidemiol. Infect. 2001;126(3):445–452. doi: 10.1017/s0950268801005519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretto E., Visiello R., Nardini P. Pet-To-Man Travelling Staphylococci. Elsevier; 2018. pp. 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Castelani L., Santos A., dos Santos Miranda M., Zafalon L., Pozzi C., Arcaro J. Molecular typing of mastitis-causing Staphylococcus aureus isolated from heifers and cows. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14(2):4326–4333. doi: 10.3390/ijms14024326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty S., Dhama K., Tiwari R., Iqbal Yatoo M., Khurana S.K., Khandia R., Munjal A., Munuswamy P., Kumar M.A., Singh M., Singh R., Gupta V.K., Chaicumpa W. Technological interventions and advances in the diagnosis of intramammary infections in animals with emphasis on bovine population—a review. Vet. Quart. 2019;39(1):76–94. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2019.1642546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmagh A.A., Abd Al-Abbas M.J. PCR-RFLP by AluI for coa gene of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolated from burn wounds, pneumonia and otitis media. Gene Rep. 2019;15:100390. [Google Scholar]

- Chu C., Wei Y., Chuang S.-T., Yu C., Changchien C.-H., Su Y. Differences in virulence genes and genome patterns of mastitis-associated Staphylococcus aureus among goat, cow, and human isolates in Taiwan. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013;10(3):256–262. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto N., Belas A., Kadlec K., Schwarz S., Pomba C. Clonal diversity, virulence patterns and antimicrobial and biocide susceptibility among human, animal and environmental MRSA in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015;70(9):2483–2487. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremonesi P., Pozzi F., Raschetti M., Bignoli G., Capra E., Graber H.U., Vezzoli F., Piccinini R., Bertasi B., Biffani S., Castiglioni B., Luini M. Genomic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus strains associated with high within-herd prevalence of intramammary infections in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015;98(10):6828–6838. doi: 10.3168/jds.2014-9074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dastmalchi Saei H., Panahi M. Genotyping and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dairy ruminants: differences in the distribution of clonal types between cattle and small ruminants. Arch. Microbiol. 2020;202(1):115–125. doi: 10.1007/s00203-019-01722-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson I.A. collaborative investigation of phages for typing bovine staphylococci. Bull. World Health Organ. 1972;46:81–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dendani Chadi Z., Arcangioli M.A., Bezille P., Ouzrout R., Sellami N.L. Genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine clinical mastitis by Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2010;9:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dendani Chadi Z., Bezille P., Arcangioli M.A. PCR and PCR-RFLP genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus coagulase gene: Convenience compared to pulse-field gel electrophoresis. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2016;25:1061–1064. [Google Scholar]

- DeOliveira A.P., Watts J.L., Salmon S.A., Aarestrup F.M. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Europe and the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2000;83:855–862. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)74949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriese L.A., Van Damme L.R., Fameree L. Methicillin (cloxacillin)-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis cases. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B. 1972;19:598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1972.tb00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriese L.A. A simplified system for biotyping Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from different animal species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1984;56:215–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1984.tb01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte C.M., Freitas P.P., Bexiga R. Technological advances in bovine mastitis diagnosis: an overview. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 2015;27:665–672. doi: 10.1177/1040638715603087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effendi M.H., Hisyam M.A.M., Hastutiek P., Tyasningsih W. Detection of coagulase gene in Staphylococcus aureus from several dairy farms in East Java, Indonesia, by polymerase chain reaction. Vet. World. 2019;12:68–71. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2019.68-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ashker M., Gwida M., Tomaso H., Monecke S., Ehricht R., El-Gohary F., Hotzel H. Staphylococci in cattle and buffaloes with mastitis in Dakahlia Governorate. Egypt. J. Dairy Sci. 2015;98:7450–7459. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ashker M., Gwida M., Monecke S., El-Gohary F., Ehricht R., Elsayed M., Akinduti P., El-Fateh M., Maurischat S. Antimicrobial resistance pattern and virulence profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from household cattle and buffalo with mastitis in Egypt. Vet Microbiol. 2020;240 doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.108535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbehiry A., Al-Dubaib M., Marzouk E., Osman S., Edrees H. Performance of MALDI biotyper compared with Vitek™ 2 compact system for fast identification and discrimination of Staphylococcus species isolated from bovine mastitis. Microbiologyopen. 2016;5:1061–1070. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sayed A., Awad W., Abdou N.E., Castañeda Vázquez H. Molecular biological tools applied for identification of mastitis causing pathogens. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2017;5:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijvsm.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltrin F., Alba P., Kraushaar B., Ianzano A., Argudín M.A., Di Matteo P., Porrero M.C., Aarestrup F.M., Butaye P., Franco A., Battisti A. A livestock-associated, multi-drug-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clonal complex 97 lineage spreading in dairy cattle and pigs in Italy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016;82:816–821. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02854-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feßler A., Scott C., Kadlec K., Ehricht R., Monecke S., Schwarz S. Characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 from cases of bovine mastitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:619–625. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, E. A., Paterson, G. K., 2020. Prevalence and characterization of methicillin-resistant staphylococci from bovine bulk tank milk in England and Wales. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. Pii, S2213-7165(20)30014-X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fitzgerald J.R., Meaney W.J., Hartigan P.J., Smyth C.J., Kapur V. Fine-structure molecular epidemiological analysis of Staphylococcus aureus recovered from cows. Epidemiol. Infect. 1997;119:261–269. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald J.R. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus: origin, evolution and public health threat. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20:192–198. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier C., Kuhnert P., Frey J., Miserez R., Kirchhofer M., Kaufmann T., Graber H.U. Bovine Staphylococcus aureus: association of virulence genes, genotypes and clinical outcome. Res. Vet. Sci. 2008;85(3):439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fursova K., Sorokin A., Sokolov S., Dzhelyadin T., Shulcheva I., Shchannikova M., Nikanova D., Artem'eva O., Zinovieva N., Brovko F. Virulence factors and phylogeny of Staphylococcus aureus associated with bovine mastitis in Russia based on genome sequences. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020;7:135. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alvarez L., Holden M.T.G., Lindsay H., Webb C.R., Brown D.F.J., Curran M.D., Walpole E., Brooks K., Pickard D.J., Teale C., Parkhill J., Bentley S.D., Edwards G.F., Girvan E.K., Kearns A.M., Pichon B., Hill R.L., Larsen A.R., Skov R.L., Peacock S.J., Maskell D.J., Holmes M.A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with a novel mecA homologue in human and bovine population in the UK and Denmark: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2011;11:595–603. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70126-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogoi-Tiwari J., Babra-Waryah C., Sunagar R., Veeresh H.B., Nuthanalakshmi V., Preethirani P.L., Sharada R., Isloor S., Bhat A., Al-Salami H., Hegde N.R., Mukkur T.K. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis cases in Australia and India. Aust. Vet. J. 2015;93:278–282. doi: 10.1111/avj.12349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber H.U., Pfister S., Burgener P., Boss R., Meylan M., Hummerjohann J. Bovine Staphylococcus aureus: Diagnostic properties of specific media. Res. Vet. Sci. 2013;95:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber H.U. Genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus by ribosomal spacer PCR (RS-PCR) J. Vis. Exp. 2016;4:54623. doi: 10.3791/54623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graveland H., Duim B., van Duijkeren E., Heederik D., Wagenaar J.A. Livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in animals and humans. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011;301:630–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunert T., Stessl B., Wolf F., Sordelli D.O., Buzzola F.R., Ehling-Schulz M. Distinct phenotypic traits of Staphylococcus aureus are associated with persistent, contagious bovine intramammary infections. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15968. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34371-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurjar A., Gioia G., Schukken Y., Welcome F., Zadoks R., Moroni P. Molecular diagnostics applied to mastitis problems on dairy farms. Vet. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2012;28:565–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidry A., Fattom A., Patel A., O'Brien C., Shepherd S., Lohuis J. Serotyping scheme for Staphylococcus aureus isolated from cows with mastitis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1998;59:1537–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi Alni R., Mohammadzadeh A., Mahmoodi P. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus of different origins based on the polymorphism of the spa gene: characterization of a novel spa type. 3Biotech. 2018;8:58. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-1061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haran K.P., Godden S.M., Boxrud D., Jawahir S., Bender J.B., Sreevatsan S. Prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, isolated from bulk tank milk from Minnesota dairy farms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50:688–695. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05214-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasman H., Moodley A., Guardabassi L., Stegger M., Skov R.L., Aarestrup F.M. Spa type distribution in Staphylococcus aureus originating from pigs, cattle and poultry. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;141:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hata E., Katsuda K., Kobayashi H., Uchida I., Tanaka K., Eguchi M. Genetic variation among Staphylococcus aureus strains from bovine milk and their relevance to methicillin-resistant isolates from humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:2130–2139. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01940-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havaei S.A., Assadbeigi B., Esfahani B.N., Hoseini N.S., Rezaei N., Havaei S.R. Detection of mecA and enterotoxin genes in Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with bovine mastitis and characterization of Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) in MRSA strains. Iran J. Microbiol. 2015;7:161–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haveri M., Suominen S., Rantala L., Honkanen-Buzalski T., Pyörälä S. Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic detection of penicillin G resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine intramammary infection. Vet. Microbiol. 2005;106:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Xie Y., Reed S. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1085:103–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-664-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra J., Zomer A.L., Rutten V.P.M.G., Benedictus L., Stegeman A., Spaninks M., Bennedsgaard T.W., Biggs A., De Vliegher S., Mateo D.H., Huber-Schlenstedt R., Katholm J., Kovács P., Krömker V., Lequeux G., Moroni P., Pinho L., Smulski S., Supré K., Swinkels J.M., Holmes M.A., Lam T.J.G.M., Koop G. Genomic analysis of European bovine Staphylococcus aureus from clinical versus subclinical mastitis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:18172. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75179-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]