Abstract

Many individuals who have had a stroke leave the hospital without postacute care services in place. Despite high risks of complications and readmission, there is no standard in the United States for postacute stroke care after discharge home. We describe the rationale and methods for the development of the COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) care model and the structure and quality metrics used for implementation. COMPASS, an innovative, comprehensive extension of the TRAnsition Coaching for Stroke (TRACS) program, is a clinician-led quality improvement model providing early supported discharge and transitional care for individuals who have had a stroke and have been discharged home. The effectiveness of the COMPASS model is being assessed in a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial in 41 sites across North Carolina, with a recruitment goal of 6,000 participants. The COMPASS model is evidence based, person centered, and stakeholder driven. It involves identification and education of eligible individuals in the hospital; telephone follow-up 2, 30, and 60 days after discharge; and a clinic visit within 14 days conducted by a nurse and advanced practice provider. Patient and caregiver self-reported assessments of functional and social determinants of health are captured during the clinic visit using a web-based application. Embedded algorithms immediately construct an individualized care plan. The COMPASS model’s pragmatic design and quality metrics may support measurable best practices for postacute stroke care.

Keywords: stroke, patient-centered, post-acute care, transitional care, quality improvement

Stroke is a major cause of disability in the United States and incurs a high cost to stroke survivors, their caregivers, and society.1 In the United States, approximately 45% of all individuals who have had a stroke and 65% of those younger than 65 receive no postacute care services.2 Only 40% of Medicare beneficiaries receive physical or occupational therapy during the first 30 days after discharge home.3 Shortly after discharge, individuals who have had a stroke are particularly likely to be readmitted to the hospital or transition to a more intensive level of care.4 Some of the most common reasons for readmission and emergency department (ED) visits are stroke related, including poor balance, falls, fractures, recurrent stroke or exacerbation of stroke symptoms, and dysphagia. Complex comorbidities and medication regimens increase the likelihood of medication nonadherence5 and recurrent stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).6 Many stroke survivors and caregivers have poor health literacy related to understanding stroke risk factors7 and how to manage them.8 Managing medications, appointments, and therapies can be a major strain on caregivers, which can further impede stroke recovery.9

Many individuals who have had a stroke and their caregivers cite a lack of resources that provide necessary tools and support to manage postacute stroke care,10–12 and many lack knowledge about available community providers and programs. Furthermore, there are barriers to medical record transfer from hospitals to community-based providers.13 Consequently, the plan for stroke prevention and continued recovery after hospitalization is often absent or poorly defined.

There are no best-practice measures of postacute stroke care quality in the United States nor a consensus on which outcomes should be used to assess its delivery.14 How individuals who have had a stroke are referred to services after discharge varies widely,2 and few effective models provide potential pathways for postacute care standardization. A recent meta-analysis found that only 6 of 13 models of stroke transitional care were associated with improvement in one or more measured outcomes, including mortality, disability, neuromotor function, risk factor management, and other stroke-related outcomes, and none significantly reduced 30-day readmissions or ED visits.15 A 2013 review of 43 interventions to reduce 30-day readmissions for individuals discharged home reported that, although stand-alone interventions (e.g., education, discharge planning, follow-up telephone call, person-centered discharge instructions, discharge nurses) were not effective in reducing readmissions, multicomponent interventions resulted in reductions in 30-day readmission of 3.6 to 28 percentage points.16 A systematic review of stroke transitional care models reported early supported discharge, which has largely been tested and adopted in the United Kingdom,17 other European countries,18,19 and Canada,17 as the most effective model.20 Transitional care management (TCM) models have been widely tested in the United States in individuals with conditions other than stroke,21 including heart failure22 and myocardial infarction.23

To promote the use of effective postacute care coordination, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed billing codes for the care coordination of early postdischarge follow-up of complex chronic diseases,24 but many providers are uncertain how best to implement programs that fulfill these billing requirements for stroke. The CMS Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) requires implementation of a merit-based incentive payment system, which requires that hospitals provide care coordination, care plans for medically complex individuals, and patient engagement for self-management and shared decision making.25 Care plans must be available to all patients and providers to manage care coordination, optimize self-management, address relevant health concerns, and identify functional and psychosocial needs and the resources to meet those needs.25

Aligned with CMS TCM and MACRA requirements to address current gaps in postacute stroke care, the COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) model is being compared with usual care in a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial in 41 hospitals across North Carolina. The COMPASS trial focuses on individuals diagnosed with stroke or TIA and discharged home, with the primary outcome measure of functional status 90 days after discharge.26 Detailed methods have been described.27

We discuss the rationale and methods used to develop the COMPASS model and the process through which this complex, pragmatic model was designed. We also describe the structures and processes for implementation of COMPASS in real-world practice.

METHODS

Evidenced-based models including early supported discharge,17 TCM,24 and our experience with the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center TRAnsitional Coaching for Stroke (TRACS) quality improvement program, designed to reduce 30-day readmissions and improve functional outcomes for individuals who have had a stroke discharged home,28 were used to develop COMPASS. In the TRACS model, a registered nurse provided education at discharge and contacted eligible individuals within 2 days after discharge. A nurse practitioner conducted an outpatient visit within 14 days, at which he or she identified needs of individuals with stroke and their caregivers and provided recommended referrals to rehabilitation services, therapies, home health, and community resources.24,28 Participation in TRACs was associated with a nearly 50% reduction in 30-day readmissions, even after adjustment for stroke severity, complex comorbidities, prior hospitalizations, and prior stroke.29

In the COMPASS model, we build on the multicomponent TRACs model by adding components that more comprehensively address the medical, psychosocial, and practical postacute care needs of individuals with stroke or TIA.

COMPASS Model

Expanding on TRACS,29 COMPASS provides a truly comprehensive postacute care model by addressing the diverse and complex needs of patients and their caregivers from a cumulative medical, neurological, functional, and social perspective.30,31 Incorporating person-centeredness, the COMPASS team engaged stakeholders (stroke survivors, caregivers, nurses, hospital staff, therapists, primary care providers, pharmacists, home health agencies) to inform modifications of the TRACS model32 (Figure 1, Table 1). In an effort to optimize outcomes, guide stroke recovery management, and provide a person-centered model with maximum practical feasibility, COMPASS expands on TRACS using a number of core elements.

Figure 1.

COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) model key message domains.

Table 1.

Comparison of TRAnsition Coaching for Stroke (TRACS) and COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) Model Components

| TRACS | COMPASS |

|---|---|

| Educational materials given at discharge | Educational materials given at discharge, including blood pressure log and refrigerator magnet with COMPASS pathway |

| 2- to 7-day follow-up telephone call | 2-day follow-up telephone call including assessment of transportation to clinic and other appointments |

| Clinic visit with stroke nurse practitioner 2 to 3 weeks after discharge, including: ● Follow-up on stroke examination ● Assessment of risk factor management, depression, cognition, communication, modified Rankin scale ● Referrals to home health; outpatient physical, occupational, speech therapy; community resources ● Communication with primary care physician and other specialists |

Clinic visit with advanced practice provider within 2 weeks of discharge, including: ● Follow-up on stroke examination ● Assessment of risk factor management, depression, cognition, communication, modified Rankin scale, lifestyle management, physical activity ● Postacute functional assessment ● Caregiver assessment (if triggered) ● COMPASS-CP based on assessments including referrals to home health; outpatient physical, occupational, speech therapy; community resources ● Communication with primary care physician with cover letter in electronic medical record and access code to COMPASS-CP on secure COMPASS Website ● Informational documents for patients and caregivers at clinic visit and on secure COMPASS website |

| Follow-up telephone calls at 30 and 60 days by postacute care coordinator | |

|

Monthly post-acute quality metrics for each site, including percent of eligible patients that: ● Received 2-day call ● Were seen at clinic visit and received COMPASS-CP ● Received referred rehabilitation services |

|

| Follow-up with stroke neurologist 3 to 6 months after nurse practitioner visit at discretion of nurse practitioner | Outcome assessments via telephone at 90 days by coordinating center |

Bold type indicates key differences between TRACS and COMPASS models.

COMPASS-CP = web-based application generating a COMPASS Care Plan at the point of care.

Standardized Messaging

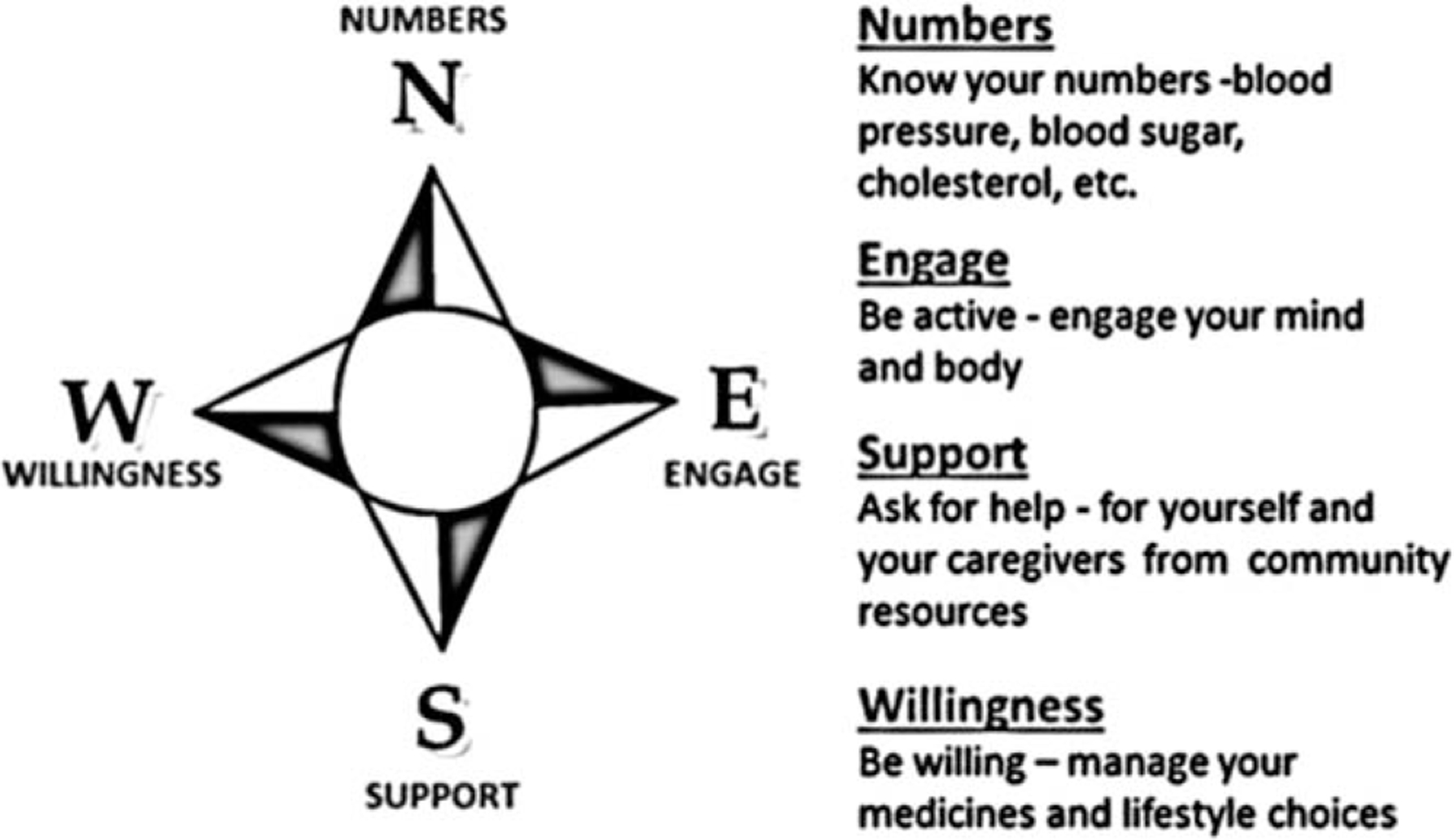

Patients and caregivers shared that they felt overwhelmed with multiple and inconsistent messages from various providers. To address this, the interdisciplinary COMPASS team developed standardized messaging32 addressing 4 essential domains of self-management and care to help people find their way forward after stroke for optimal recovery, independence, and health: know your numbers, engage, support, and willingness to manage medications and lifestyle (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure S1). Each of these domains addresses three questions:

Figure 2.

Key stakeholders in COMPrehnsive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) model development.

What are my health concerns? Identify clinical and nonclinical health factors affecting health, independence, and recovery.

Why is this important to me? Explain the importance of each area of concern based on postdischarge assessments and how each affects recovery and secondary prevention.

How do I find my way forward? Provide recommendations for self-management and referrals consistent with the individual’s needs, goals, and preferences.

Electronic Individualized Care Plans

Patient and caregiver self-report assessments of poststroke limitations at the clinic visit27 identify patients’ goals and functional and social factors affecting self-management and recovery. Assessments also include preferences for advanced directives and information about access to and use of primary care and rehabilitation services, ED visits and hospitals admissions, and knowledge of cardiovascular and stroke risk factors.27 These data are supplemented with essential health data (e.g., medication reconciliation, blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin, cholesterol, international normalized ratio (INR) values) and lifestyle information (alcohol, smoking, drug use, physical activity). Because an important driver of health outcomes for many people is the presence of a willing and able caregiver,10,12 we also assess caregivers’ roles and ability to provide support and assistance.

Using embedded algorithms, assessments immediately generate provider reports and care plans with individualized suggestions for self-management and referrals based on the individual’s problems, resources, and needs. This care plan-generating application (COMPASS-CP) also produces an electronic report detailing individualized concerns and recommendations and electronic follow-up notes to primary care providers, pharmacists, and rehabilitation providers that can be accessed on the secure COMPASS website.

Community Resources Directory

A stroke-specific community resources directory (CRD) was systematically created for all 100 North Carolina counties and is included in the COMPASS-CP algorithm, based on individuals’ addresses and identified needs. The CRD provides contact information for local support groups, behavioral health services, pharmacy services, area agency on aging services, fall prevention programs, chronic disease management and prevention programs, and community exercise programs. Special attention is paid to organizations providing services to individuals younger than 60 and those who are uninsured with no ability to pay, are living in rural areas, have cognitive deficits, or have limited access to transportation.

Education Materials

Educational and resource materials were designed to optimize messaging regarding what matters most to stroke survivors, their caregivers, and their providers (Supplementary Table S2). Materials were targeted for patient, caregiver, and provider audiences and were synergized to ensure a consistent message across the continuum of care and for all postacute care providers.

Performance Quality Metrics

We developed a set of postacute care quality measures to evaluate adherence to the COMPASS care model processes, including receipt of a follow-up call within 2 business days, a clinic visit within 14 calendar days, a printed COMPASS-CP during the clinic visit, and home health or outpatient rehabilitation services within 30 days for those who are referred. Metrics are reported monthly to the stroke care team at each site (Table 1) to drive continuous feedback and quality improvement.

Ethics Approval

The Wake Forest University Health Sciences institutional review board (IRB), acting as central IRB for 36 participating hospitals, approved this study. Five additional sites granted local IRB approval. Informed consent is provided at the outset of the 90-day call for all patients and, additionally, at the outset of the clinic visit for patients discharged from intervention sites. Additional details have been published elsewhere. 27

RESULTS

Critical Elements of the COMPASS Model

To ensure efficient workflow and meet TCM billing code requirements,24 the COMPASS model requires participation from at least 2 staff members at each participating hospital: a postacute coordinator (PAC; registered nurse or licensed practical nurse) and an advanced practice provider (APP; nurse practitioner or physician assistant) or physician. Both receive stroke-specific training on inpatient and outpatient aspects of stroke care and coordination of local postacute care resources in a 2-day in-person program that an interdisciplinary team designed and is eligible for continuing education credit. All providers (acute care, primary care, home health agencies, outpatient therapists) are also given access to educational videos, webinars, and documents through the COMPASS website, some of which meet criteria for continuing education credits. At each hospital implementing the COMPASS intervention, a liaison (usually the PAC) assists the COMPASS team in creating a CRD for the hospital’s primary catchment area.

Important responsibilities of the PAC are:

Proactively identifying eligible individuals with stroke and TIA discharged home.27

Recruiting and enrolling eligible individuals at the bedside, including sharing information about the COMPASS care model, blood pressure log and instructions, setting up a clinic appointment and other urgent appointments, and obtaining patient and caregiver contact information.

Placing a 2-day call to the individual or caregiver to confirm medication reconciliation, appointments for COMPASS clinic, primary care, and outpatient therapy (if needed) and obtaining INR values for individuals taking warfarin, blood pressure measurements, and information on new stroke symptoms and falls and reinforcing stroke education.

Conducting a brief (approximately 15 minutes) standardized functional assessment of the patient and caregiver during the clinic visit.

Placing 30- and 60-day follow-up calls to obtain information about the individual’s functional status and receipt of referrals and associated services.

The APP is responsible for completing a comprehensive 7- to 14-day in-clinic evaluation (approximately 45 minutes) 24 and printing, sharing, and reviewing the COMPASS-CP with the individual and caregiver.

Evidence of feasible implementation

As the COMPASS coordinating site, the Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center Comprehensive Stroke Center was designated the vanguard site, where the COMPASS model was developed, piloted, and refined 6 weeks before launching the COMPASS trial. Based on this experience, we continuously refine implementation of the intervention to address challenges identified in clinical practice, training, and workflow.33

DISCUSSION

COMPASS addresses a significant gap in postacute care for individuals with stroke discharged home. It is an evidence-based, person-centered, stakeholder-driven model of postacute stroke care that is aligned with CMS TCM and MACRA requirements. It incorporates quality metrics for assessing implementation success and effectiveness in improving outcomes. The COMPASS model uses a secure, mobile, electronic format that can be integrated into various electronic medical record platforms to enable structured, efficient charting.

The COMPASS model also addresses multiple areas of clinical research identified as among the most critically needed for older adults with complex chronic conditions.34 It addresses 13 of the 15 top topics that leading aging health researchers have identified: health-related quality of life; development of assessment tools to assess self-reported outcome measures; medication interactions; disability; implementation of novel, scalable care models; association between chronic conditions and clinical, financial, and social outcomes; caregivers’ roles; symptom burden; shared decision-making to enhance care planning; tools to improve clinical decision-making; interventions that promote self-management; interventions that involve multiple components and pragmatic trials; and symptom management. Although one of the core strengths of the COMPASS model is that it is customized to meet the specific, complex needs of stroke survivors, an equally valuable strength is that it can easily be adapted to meet the specific needs of other complex chronic conditions.

Although the COMPASS model has many benefits, there are a number of implementation challenges. First, identifying eligible individuals with stroke or TIA is challenging when hospital stays are short and the final diagnosis may only be determined immediately before discharge. Also, individuals with TIA may be in observation in the ED for less than 24 hours and are difficult to capture prospectively. Identifying vascular (versus nonvascular) TIA events is challenging because of reliance on clinical symptoms and because multiple transient conditions can mimic a TIA. To address this, we created an enrollment algorithm27 based on the American Heart Association definition of TIA to help PACs identify eligible individuals that was piloted and refined at the vanguard site.35

Incorporating the COMPASS staffing model into each hospital’s unique clinical workflow and staffing structure is challenging. At the vanguard site, the PAC and APP worked together to determine a sustainable clinical workflow that might be most easily transferrable to other hospitals. A dedicated COMPASS implementation coordinator helps staff individualize implementation of the core model components at each site, and lessons learned are systematically incorporated into each following implementation effort.

Barriers to successful participation in the clinic visit identified at the vanguard site were transportation, scheduling conflicts, and financial burdens. To address these challenges, uninsured and underinsured individuals are offered financial assistance, more flexible appointment schedules are provided to better accommodate COMPASS patient schedules or urgent concerns, and PACs are encouraged to recommend the use of community transportation resources for individuals with transportation challenges.

To address the variation in referral processes between postacute care providers, the vanguard team partnered with home health and outpatient providers to develop the CRD and discuss the COMPASS-CP. Together they established an algorithm to share the COMPASS-CP among providers and promote a uniform referral process.

This unique model of early supported discharge managed by a multidisciplinary team, combined with an extensive local CRD, is an innovative step forward in postacute stroke care. COMPASS is an evidence-based, holistic, person-centric approach that integrates medical and community resources to meet the needs of stroke survivors and caregivers. COMPASS aims to optimize function and independence, reduce caregiver stress, facilitate self-management of risk factors and lifestyle changes, optimize medication adherence, facilitate self-management of chronic disease, and support reintegration into the community through the use of local resources.

The development of the COMPASS model exemplifies a learning health system. COMPASS incorporates assessments used to create individualized care plans at the point of clinical care, with vetting and active engagement from individuals, caregivers, and clinicians. This approach simultaneously promotes innovation and person-centered care. The COMPASS model is being expanded, embedded in clinical care, and evaluated in a large cluster-randomized pragmatic trial to evaluate its effectiveness in 41 diverse hospitals in North Carolina. The results of this trial may provide real-world evidence to inform strategies for widespread implementation, and the results may drive public policy regarding postacute stroke care.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Sample COMPASS-CP: Numbers Domain.

Table S2. Description of the educational materials developed for patients, caregivers, and providers participating in the COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Rica Abbott, Andrea Tate Mullins, and Ann Pennell Furstenberg for their input and assistance.

Financial Disclosure:

Research reported in this publication was funded through Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Awards PCS-1403–14532 and NCT02588664 and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Award UL1TR001420. We would also like to acknowledge the REDCap support of the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR001420.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02588664.

The statements presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute or its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Conflict of Interest: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettger JP, McCoy L, Smith EE et al. Contemporary trends and predictors of postacute service use and routine discharge home after stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 2015;4: pii: e001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Freburger JK, Li D, Johnson AM, Fraher EP. Physical and occupational therapy from the acute to community setting after stroke: Predictors of use, continuity of care, and timeliness of care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;pii: S0003–9993(17)30220–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Kind AJH, Smith MA, Frytak JR, Finch MD. Bouncing-back: Patterns and predictors of complicated transitions thirty days after hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:365–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bushnell CD, Zimmer LO, Pan W et al. Persistence with stroke prevention medications 3 months after hospitalization. Arch Neurol 2010;67:1456–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings DM, Letter AJ, Howard G et al. Medication adherence and stroke/TIA risk in treated hypertensives: Results from the REGARDS study. J Am Soc Hypertens 2013;7:363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willey JZ, Williams O, Boden-Albala B. Stroke literacy in central Harlem: A high-risk stroke population. Neurology 2009;73:1950–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fang MC, Panguluri P, Machtinger EL, Schillinger D. Language, literacy, and characterization of stroke among patients taking warfarin for stroke prevention: Implications for health communication. Patient Educ Couns 2009;75:403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salter K, Allen L, Richardson M et al. Chapter 19: Community Reintegration. Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation; 2013. [on-line]. Available at http://www.ebrsr.com/evidence-review/19-community-reinte-gration Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 10.Cameron J, Gignac M. “Timing It Right”: A conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the hospital to the home. Patient Educ Couns 2008;70:305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legg LA, Quinn TJ, Mahmood F et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for caregivers of stroke survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;10:CD008179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forster A, Brown L, Smith J et al. Information provision for stroke patients and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:CD001919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM et al. A failure to communicate: A qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:417–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker MF, Sunnerhagen KS, Fisher RJ. Evidence-based community stroke rehabilitation. Stroke 2013;44:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puhr MI, Thompson HJ. The use of transitional care models in patients with stroke. J Am Assoc Neurosci Nurses 2015;47:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kripalani S, Theobald CN, Anctil B, Vasilevskis EE. Reducing hospital readmission rates: Current strategies and future directions. Annu Rev Med 2014;65:471–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fearon P, Langhorne P. Early Supported Discharge Trialists. Services for reducing duration of hospital care for acute stroke patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9:CD000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fjærtoft H, Indredavik B, Lydersen S. Stroke unit care combined with early supported discharge: Long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2003;34:2687–2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorsén AM, Holmqvist LW, de Pedro-Cuesta J, von Koch L. A randomized controlled trial of early supported discharge and continued rehabilitation at home after stroke: Five-year follow-up of patient outcome. Stroke 2005;36:297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prvu Bettger J, Alexander KP, Dolor RJ et al. Transitional care after hospitalization for acute stroke or myocardial infarction: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012;157:407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, Hirschman KB. The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:746–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vedel I, Khanassov V. Transitional care for patients with congestive heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:562–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prvu Bettger J, Alexander KP, Dolor RJ et al. Transitional care after hospitalization for acute stroke or myocardial infarction: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:407–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Transitional Care Management Services Fact Sheet. Quality Payment Program Resource Library [on-line] Available at https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf Accessed June 19, 2017.

- 25.Quality Payment Program. Quality Payment Program Resource Library [on-line] Available at https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/education Accessed April 8, 2017.

- 26.Duncan P, Lai S, Bode R, Perera S, DeRosa J. Stroke Impact Scale-16. A brief assessment of physical function. Neurology 2003;60:291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan PW, Bushnell CD, Rosamond W et al. The Comprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) Study: Design and methods for a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. BMC Neurol 2017;17:133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bushnell C, Arnan M, Han S. A new model for secondary prevention of stroke: Transition coaching for stroke. Stroke 2014;5:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Condon C, Lycan S, Duncan P, Bushnell C. Reducing readmissions after stroke with a structured nurse practitioner/registered nurse transitional stroke program. Stroke 2016;47:1599–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, R Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: A functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:1041–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M. Preventing 30-day hospital read-missions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1095–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gesell SB, Klein KP, Halladay J et al. Methods guiding stakeholder engagement in planning a pragmatic study on changing stroke systems of care. J Clin Transl Sci 2017;1:121–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson AM, Jones SB, Duncan PW et al. Hospital recruitment for a pragmatic cluster-randomized clinical trial: Lessons learned from the COMPASS study. BMC Trials 2018;19:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tisminetzky M, Bayliss EA, Magaziner JS et al. Research priorities to advance the health and health care of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:1549–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack. Stroke 2009;40:2276–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Sample COMPASS-CP: Numbers Domain.

Table S2. Description of the educational materials developed for patients, caregivers, and providers participating in the COMprehensive Post-Acute Stroke Services (COMPASS) intervention.