Abstract

COVID-19, whose etiological agent is the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has caused over 537.5 million cases and killed over 6.3 million people since its discovery in 2019. Despite the recent development of the first drugs indicated for treating people already infected, the great need to develop new anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs still exists, mainly due to the possible emergence of new variants of this virus and resistant strains of the current variants. Thus, this work presents the results of QSAR and similarity search studies based only on 2D structures from a set of 32 bicycloproline derivatives, aiming to quickly, reproducibly, and reliably identify potentially useful compounds as scaffolds of new major protease inhibitors (Mpro) of the virus. The obtained QSAR model is based only on topological molecular descriptors. The model has good internal and external statistics, is robust, and does not present a chance correlation. This model was used as one of the tools to support the virtual screening stage carried out in the SwissADME web tool. Five molecules, from an initial set of 2695 molecules, proved to be the most promising, as they were within the model’s applicability domain and linearity range, with low potential to cause carcinogenic, teratogenic, and reproductive toxicity effects and promising pharmacokinetic properties. These five compounds were then selected as the most competent to generate, in future studies, new anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents with drug-likeness properties suitable for use in therapy.

Keywords: COVID-19, 3CLpro, QSAR, Virtual screening, ADMET studies

Introduction

The COVID-19 virus, a disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, has caused, since its discovery (November 2019) to date (June 2022), more than 537.5 million cases and has been responsible for the deaths of more than 6.3 million people [1]. Moreover, an indefinite number of patients have neurological, physical, and psychological sequelae. In addition to the damage to public health worldwide, this pandemic has also caused severe economic and political consequences [2], as have not been seen in society for a long time. The European continent stood out as the region with the highest number of cases (over 224.4 million), while the Americas had the highest number of deaths (over 2.75 million) [1]. However, there are strong indications of underreporting of cases and deaths, which are higher or lower according to the country and region. Approximately half of the recorded deaths, in absolute numbers, were concentrated in just 12 countries: United States of America (USA), Brazil, India, Russian Federation, Mexico, Peru, United Kingdom, Italy, Indonesia, France, Iran, and Germany [3].

The disease manifests the first symptoms on average 5.2 days after infection by SARS-CoV-2 [4]. The most common manifestations include fever, cough, myalgia, or fatigue, while less common symptoms include increased mucus production, headache, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal manifestations [5]. However, there are descriptions of several even less common symptoms in the literature, such as skin rashes, brain fog, pink eyes, light sensitivity, sore eyes, itchy eyes, delirium or severe confusion, and hair loss [6]. Even with this extensive symptomatology, most cases are benign or without symptoms. However, circumstances with severe progression and serious lung damage can arise in a much more significant proportion than other infections and can lead to death. These cases may require oxygen-therapy support, requiring, in more severe cases, ventilatory help to maintain the patient [7].

From the elucidation of the replication cycle of SARS-CoV-2, it was possible to visualize promising targets for developing new drugs, either related to the virus cycle or to the host that allows or favors the virus entry and the establishment of the disease [8]. In this context, the major protease (3CLpro or Mpro) is one of the most critical and essential viral proteins in the cycle viral. It is responsible for cleavage at 11 sites in the immature polyproteins that will originate the viral proteins. For this reason, this enzyme has become an important target for developing new antiviral drugs [9–11], and some drugs that act on this target have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, even with the approval of these drugs, as well as vaccines developed by several pharmaceutical companies and universities, there is still a great need for the development of new preventive or therapeutic alternatives to fight this infection, mainly because of the potential emergence of new and resistant strains, and due to limited access to available immunizers, especially in the poorest countries [12], for instance, in some of the most recent periods of the pandemic, with the recurrent waves of infection caused by the Delta and Omicron strains [13]. The consequences of possible new waves of COVID-19 are unacceptable because of the high mortality rate, severe economic damage, and impact on the living habits of the population [14, 15].

Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship (QSAR) methods are among the many approaches to accelerate the development of new drugs, including antivirals. This approach can assist in this process by having the ability to assertively predict essential characteristics for the biological activity of candidates for new bioactive molecules through validated multivariate mathematical models [16, 17], besides being able to elucidate the complex relationships between the independent and dependent variables of the study. Despite the considerable number of in silico studies published since the emergence of the pandemic [18], including even the development of specific tools for the theme [19], the number of QSAR studies using sets of active compounds against targets useful for drug development for the COVID-19 treatment is limited since, in temporal terms, the emergence of this disease is considerably recent. Thus, there has not been enough time to obtain and publish many in vitro or in vivo active derivatives that can be useful as “seeds” or “starting points” for new projects or even target existing ones.

Considering the scenario presented, the authors present the results of a QSAR based only on the simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings [20, 21] of 32 bicycloproline derivatives [15]. The strings were used to calculate 0D, 1D, and 2D molecular descriptors (i.e., that do not depend on geometry optimization and can be quickly obtained). Similarly, the authors searched for new molecular scaffolds using only the common 2D chemical structure of the congener series selected for the study [22]. The authors used this process to identify new chemical scaffolds potentially helpful in developing new Mpro inhibitors via a more straightforward and faster process, as the approaches used to deal with classical chemoinformatics, chemometrics, and QSAR procedures. In this context, the validation of the model received particular attention, as well as the evaluation of its reliability regarding its use in a virtual screening step, aiming to strengthen the potential for success in future biological assays of the compounds selected at the end of the study.

Material and methods

Preparation of the dataset

The dataset consists of 32 bicycloproline derivatives synthesized and tested for Mpro inhibition by Qiao et al. [15], which derive from boceprevir and telaprevir, two molecules approved as drugs for treating hepatitis C virus (HCV) and which can inhibit Mpro. This dataset is one with the most significant number of compounds active against the target of interest available to date.

The dataset’s antiviral activity showed a good and wide range of activity variation (IC50 7.6 to 748.5 nM). The y-vector was preprocessed to minimize the prevalence of this range in later stages of the study [23] by converting the values to pIC50 (− log IC50, or Log 1/IC50), a standard process in QSAR studies [16], with a new range of 6.12 to 8.12 (i.e., two logarithmic units). This range is minimally acceptable considering the objectives of this study.

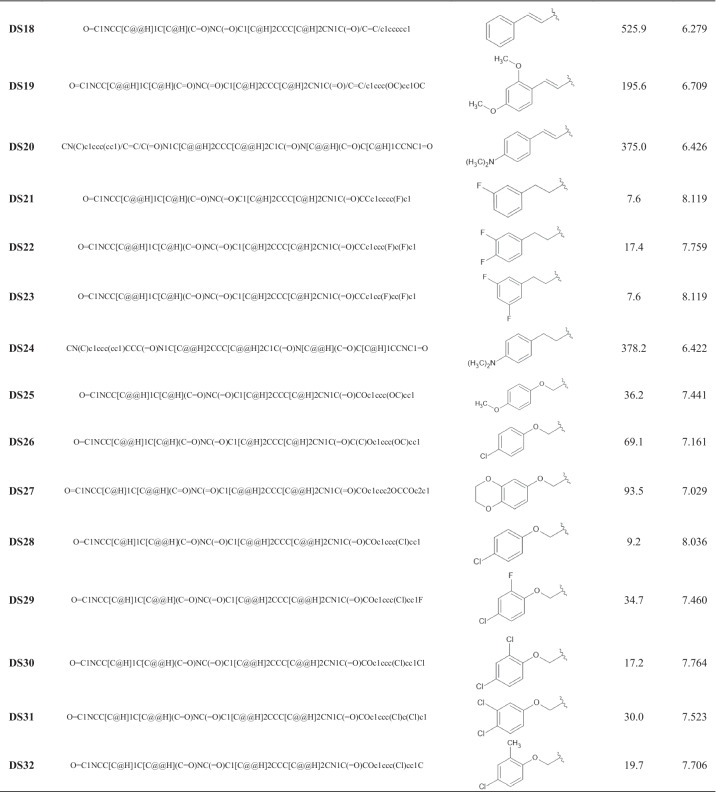

The editor ChemSketch 12.0 [24] allowed the construction of the dataset compounds’ structures and obtaining the respective SMILES strings [21]. The SMILES strings of the compounds, their basic structures, and their biological activities are available in Table 1. This structural representation aims to facilitate and simplify obtaining descriptors and reproducing results, although it does not encode information about properties that depend on three-dimensional geometries.

Table 1.

Basic structures and SMILES strings of the derivatives in the dataset (DS) and their respective IC50 and pIC50 values

Molecular descriptors

Molecular descriptors are numerical representations representing chemical information so that information systems and software can understand the characteristics of molecular structures [25]. Descriptors are unique pieces of information for each molecule. They are products of logical-mathematical processing, allowing the information of a given structure to be understood and processed by software in chemometric studies [26]. Thus, to build the model, to obtain the independent variables, and organizing these data is initially necessary. This process was accomplished using the Dragon 6 [27], with SMILES strings as input data, enabling the rapid obtaining of molecular descriptors that depend only on 0D, 1D, and 2D information about the structures of interest. The classes of descriptors used in this work are available in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relation of calculated molecular descriptors in Dragon 6

| Class | Quantity* |

|---|---|

| Constitutional indices | 43 |

| Ring descriptors | 32 |

| Topological indices | 75 |

| Walk and path counts | 46 |

| Connectivity indices | 37 |

| Information indices | 48 |

| 2D matrix-based descriptors | 550 |

| 2D autocorrelations | 213 |

| Burden eigenvalues | 96 |

| P_VSA-like descriptors | 45 |

| Extended topochemical atom (ETA) indices | 23 |

| Edge-adjacency indices | 324 |

| Functional group counts | 153 |

| Atom-centered fragments | 115 |

| Atom-type E-state indices | 170 |

| CATS2D fingerprints | 150 |

| 2D atom pairs | 1596 |

| Molecular properties | 17 |

| Total | 3733 |

*Total obtained before the variable reduction steps

However, modern descriptor calculation programs often generate hundreds of thousands of data, which is much more information than necessary to build a QSAR model. Many descriptors will be redundant, will not provide relevant information to describe the biological activity, will be invariant or slightly variant (i.e., will not present quantitative data), and may encode high covariance, among other possible problems [28]. Thus, one of the initial steps in building QSAR models is the variable reduction process, which consists of selecting variables that preserve the essential information in the entire dataset but eliminate redundancy; they are highly intercorrelated variables. The big difference from the variable selection process is that the unwanted descriptors are selected regardless of the dependent variable [25]. Thus, when exporting the descriptors calculated by Dragon 6, the following variable reduction processes were performed: (i) removal of descriptors with constant values; (ii) removal of descriptors with constant and near-constant variables; (iii) removal of descriptors with a standard deviation of less than 0.001; (iv) removal of descriptors with at least one missing value; and (v) removal of descriptors with a pair correlation larger than or equal to 0.90. Finally, the matrix went through a final reduction in the software QSAR Modeling [29] (download: http://lqta.iqm.unicamp.br), where the descriptors with absolute Pearson’s correlation coefficient (|r|) values with the vector y were lower than 0.2. This process was carried out to remove from the matrix descriptors that did not provide relevant information to explain the endpoint under study and could still impede the model building process.

Variable selection and model construction

The matrix resulting from the variable reduction step was submitted to variable selection. Typically, the number of descriptors in QSAR is much higher than the number of samples. For this reason, it is necessary to use methodologies that allow selecting that subset of descriptors (if present) that presents the most significant contribution to explaining an endpoint of interest. Currently, there are several methods to perform this type of study, and in this study, the Ordered Predictors Selection (OPS) algorithm was used. This methodology is a procedure that allows the assignment of importance to each descriptor based on an information vector. The columns of the data matrix are reorganized so that the most relevant descriptors are presented first in the matrix [30]. This data selection makes it possible to use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to run successive regressions to generate several correlation models of the descriptors with the biological activity using latent variables (LVs).

The best combinations found will then be used in model building. QSAR models are obtained through linear or non-linear regression methods, usually multivariate. These procedures evaluate the relationship between a dependent variable, y, and an independent variable, x [31]. The software used to build the models was also QSAR Modeling [29]. Both in the variable selection and the construction of the models, the variables were autoscaled, the most suitable process for QSAR studies (and other chemometric problems) where variables with different scales of variation are used [29, 30, 32].

Model validation

QSAR models encode and correlate compounds’ physicochemical properties with their biological activities. The equation should have statistical significance, and good predictive power should be robust and not present information resulting from spurious correlations. For this, the models must be statistically validated [16, 25, 32–42]. Usually, this process is divided into internal and external validation [36–46]. The internal validation evaluates the degree of model fit, the degree of significance, and its predictive ability, considering the same compounds used to construct the model [36, 43, 44]. This evaluation was carried out with statistical parameters generally utilized and recommended for QSAR studies, as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Metrics used in the internal and external validation steps

| Parameter | Definition | Expected/recommended result | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal validation | |||

| R2 | Coefficient of determination | ≥ 0.6 | [16, 25, 32] |

| RMSEC | Root mean square error of calibration | The smallest possible | [16, 25, 32] |

| F | F-test (Fp,n-p-1) at 95% significance (α = 0.05), with “p” as the number of variables in the model (including LVs) and “n” as the number of compounds used to construct the model | Greater than the tabulated critical value | [16, 25, 32] |

| Q2LOO | Determination coefficient of cross-validation | ≥ 0.5 | [16, 25, 32] |

| RMSECV | Root mean square error of cross validation | The smallest possible | [16, 25, 32] |

| R2-Q2LOO | Difference between R2 and Q2LOO | ≥ 0.1* | [34] |

| Average rm2(pred)-LOO | Scaled r2m metrics (average value) for internal validation | ≥ 0.5 | [16, 35] |

| Δrm2(pred)-LOO | Scaled r2m metrics (difference value) for internal validation | ≤ 0.2 | [16, 35] |

| External validation | |||

| R2pred | Determination coefficient of external prediction | ≥ 0.5 | [36–38] |

| RMSEP | Root mean square error of prediction | The smallest possible | [16] |

| |R20-R2′0| | Evaluation of the absolute difference between the values of the coefficients of determination centered on the origin of the two regressions | ≤ 0.3 | [39, 40] |

| k | Slopes of the straight lines obtained by regression between observed and predicted values | 0.85 ≤ k ≤ 1.15 | [39–41] |

| k′ | Slopes of the straight lines obtained by regression between predicted and observed | 0.85 ≤ k′ ≤ 1.15 | [39–41] |

| Average_r2m(pred)-scaled | Scaled r2m metrics (average value) for external validation | ≥ 0.5 | [16, 35] |

| Δr2m(pred)-scaled | Scaled r2m metrics (difference value) for external validation | ≤ 0.2 | [16, 35] |

| ARE (%) | Average relative error | The smallest possible | [41] |

| MAE | Mean absolute error | For good predictions, ≤ 0.1 × training set range; in this study, ≤ 0.2 | [42] |

| MAE (95%) | Mean absolute error without 5% of dataset | For good predictions, ≤ 0.1 × training set range; in this study, ≤ 0.2 | [42] |

*Some authors indicate that higher values can be accepted. A more demanding criterion was adopted, given the objectives of this study

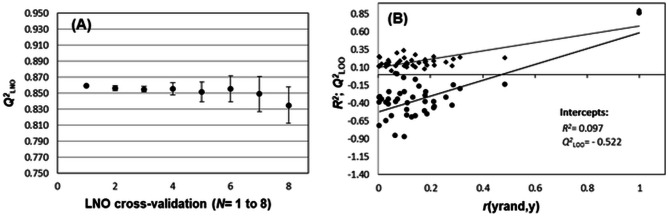

Still, in the internal validation stage, it is recommended that the presence of random correlations (i.e., which are not real, even if they appear to be) between the descriptors and the biological activity be evaluated through the y-randomization test. Here, the y-vector values are randomized. The X-matrix is kept fixed, thus building new models, which should be poor [47]. It is also advised to assess robustness (i.e., whether the model can withstand small and deliberate variations in its composition), and one of the most used methods to evaluate this property is leave-N-out cross-validation (LNO) [40, 48].

The outlier detection test checks the dataset for quality and ensures that the samples form a homogeneous set. Removing these compounds can improve the quality of the model. However, since QSAR is a reductionist approach, it is recommended to avoid removal when possible, especially for sets with few samples. The presence of outliers was assessed based on the leverage values and the values of the studentized residuals [45].

External validation, in turn, allows for a more effective analysis of the model’s predictive ability. A subset of samples (test set) is selected and removed for this. Then, using the model built with the remaining compounds (training set), this smaller set’s biological activity is calculated and compared with the experimental correspondent values [46, 47]. However, a characteristic of the dataset used is its small number of compounds. According to Roy and Ambure [49], it is difficult to develop robust and predictive models from small datasets because a significant amount of information related to the dependent and independent variables can be lost due to the removal of samples to compose the test set. Therefore, in this study, an alternative approach based on studies conducted by one of the authors was adopted [50–52]: the dataset was randomly divided into 100 different test sets, starting from the initial model obtained (defined as the auxiliary model), with the same number of compounds for each test set (eight derivatives, 25% of the dataset). The average values and standard deviations of external validation metrics (also in Table 1) parameters were calculated for each test set. The same approach was performed for the internal validation metrics to evaluate the influence of removing the various test sets and if this also influences the obtained model’s robustness. This process was carried out using an in-house algorithm written in Python. The best auxiliary model obtained using this method was used as an aid tool in one of the virtual screening process steps.

2D similarity-based virtual screening

A 2D similarity-based virtual screening [53, 54] was performed on the SwissSimilarity web tool [55], enabling ligand-based virtual screening of several libraries of small molecules using different approaches. The search was carried out in 31 databases [55]. With six bases it is possible to perform a combined search approach with the FP2 fingerprints, Electroshape-5D, Spectrophores-3D, Shape-IT, and Align-IT approaches, while with 24 bases it is possible to use a combined approach with only the first three methods. The only database that does not allow this type of combined search is the “By Click Chemistry from Sigma Aldrich library” database, where only the FP2 fingerprint search, which is the only one available for it, was used. The search was performed using the common main chain (Fig. 1) of the dataset (Table 1). After each database returned the sets, the duplicate structures and the structures with a similarity score less than 0.5 were removed. This value is equivalent to a minimum of 50% structural similarity to the structures used in the search and was selected arbitrarily. This value aimed to identify compounds not so similar to the dataset (which could lead to the identification of some samples from the dataset itself) but not so different as to allow the identification of hits without any potential to interact with Mpro.

Fig. 1.

Common structure of dataset used for 2D similarity search

Applicability domain, in silico toxicity, activity prediction, and in silico ADME

Considering a large number of compounds returned when querying the available SwissSimilarity databases, it was necessary to outline a dataset reduction approach, aiming to obtain a manageable number of compounds that had the potential to become interesting scaffolds for developing new Mpro inhibitors.

After performing tests (not shown), the Applicability Domain (AD) was selected as the first step of the process. The AD is the theoretical region in chemical space defined by the model descriptors and modeled response. This test is an important criterion to check, which enables judging the reliability of the predictive performance of a model [45, 56]. It is an especially relevant concern as the drug discovery space expands beyond small molecules to address the more challenging and novel target space with new modalities [57]. The selected approach was the Euclidean AD (using the Euclidean Applicability Domain 1.0, http://dtclab.webs.com/software-tools) because the hit compounds have no described activity, and the chemical space uses only the molecular descriptors of the dataset. To remain in the study, the hit should have a mean distance between 0 and 1, which is the criterion for defining whether the prediction of its activity is minimally reliable.

After this step, the set was reduced using in silico toxicity filters, using the VEGA QSAR 1.1.4 program [58]. Among the available models, compounds with the potential to trigger mutagenicity (AMES test), carcinogenicity, and developmental toxicity effects (all by CAESAR models) were evaluated. Those that had these effects predicted were removed from the set.

Next, the compounds had their activities predicted using the QSAR model obtained. The calculated values were evaluated for their inclusion in the two logarithmic unit linearity range of the dataset (pIC50 6.12 to 8.12), where the model is valid and reliable. Those compounds that had their values predicted outside this range (i.e., these values derived from extrapolation) were removed since these predictions are unreliable even within the AD.

As a final step, several physicochemical properties and other important characteristics [58–60] of medicinal chemistry were evaluated using the free web tool SwissADME [60]. Among the several tools available, hits were also evaluated by the BOILED-Egg model [59], an intuitive graphical classification model used to simultaneously predict the ability of a molecule to present both passive gastrointestinal absorption (HIA) and blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeation [58]. Along with these features, this web tool predicts the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) substrate, the most important active efflux mechanism involved in those biological barriers [60].

Results and discussion

Mechanistic interpretation

From the matrix with six descriptors used in the variable selection step with the OPS method, it was possible to obtain a PLS model formed by three latent variables (LVs) that originated from six molecular descriptors derived only from the SMILES strings of the dataset. One point to highlight is that, as proposed, SMILES strings (Table 1) were used to obtain the descriptors of each compound. This approach facilitates the reproduction and use of the models by potential stakeholders. Although these descriptors do not encode geometric properties of chemical compounds, SMILES-based studies are widely carried out in chemoinformatic studies, including QSAR [61, 62], and several studies using only molecular descriptors obtained from SMILES have also been carried out [63–65]. Although in this work the authors used Dragon 6 to generate the descriptors, the classes of the selected descriptors can be found in other programs, such as ChemDes [66] or AlvaDesc [67]. The selected descriptors are presented in Table 4, together with the self-scaled coefficients of each one, whose absolute values express the importance of each variable in the model obtained.

Table 4.

Definitions of the selected descriptors

| Symbol | Descriptor | Class | Autoscaled coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eig12_AEA(bo) | Eigenvalue n. 12 from augmented edge adjacency mat. weighted by bond order | Edge adjacency indices | − 0.431 |

| Eig08_AEA(dm) | Eigenvalue n. 8 from augmented edge adjacency mat. weighted by dipole moment | 0.275 | |

| VE2_B(m) | Average coefficient of the last eigenvector from Burden matrix weighted by mass | 2D matrix-based descriptors | − 0.515 |

| MATS4e | Moran autocorrelation of lag 4 weighted by Sanderson electronegativity | 2D autocorrelations | − 0.266 |

| GATS7e | Geary autocorrelation of lag 7 weighted by Sanderson electronegativity | − 0.169 | |

| F07[C-N] | C-N frequency at topological distance 7 | 2D atom pairs | − 0.289 |

The VE2_B(m), the most important descriptor of the model, is a sum of the coefficient of the last eigenvector weighted by atomic mass—the greater the number of graph vertices (nSK), the greater its value. Since the coefficient of this descriptor is negative, this result indicates that smaller molecules will tend to be more active. This property can also be expressed by weighting by atomic mass.

The Eig12_AEA(bo), the second most important descriptor, is challenging to interpret. Considering that it is weighted by bond order and the sign of its coefficient is negative, it is possible to propose that molecules with more π electrons tend to be less active. This group has already attributed similar behavior in two other studies [68, 69] using descriptors of the same class and weighting. This interpretation can be attributed to a negative influence of the properties encoded in this descriptor on the studied compounds’ hydrophobicity. If we consider the possibility of a similar interpretation in this study, it might be related to the importance of hydrophobic interactions in the active site of Mpro. Most amino acid residues in the binding site exhibit hydrophobic characteristics [70].

Interestingly, this interpretation somewhat contradicts Eig08_AEA(dm), a molecular descriptor of the same class that is the only descriptor in the model that positively influences the activity. The weighting factor dm is the dipole moments of the chemical bonds in this descriptor [71]; thus, one can propose that the positive coefficient indicates that the presence of unsaturated bonds, which have higher dm, is positive for the activity. This relationship seems to contradict Eig08_AEA(dm), but a higher number of unsaturations may favor the formation of charge-transfer complexes with aromatic rings at the binding site. In short, one can imagine that unsaturated bonds can be positive, but this is up to a certain number and size of the molecules, from which the activity will tend to decrease. Nevertheless, this descriptor is the fifth most important in the model, and the impact of this electronic characteristic is less relevant.

The descriptor F07[C-N] is a 2D frequency fingerprint descriptor. Its negative sign indicates that nitrogen in a topological distance (lag) of seven chemical bonds related to carbon atoms is detrimental to the activity. Indeed, it is possible to observe that compounds DS21 and DS23, the most potent in the dataset, do not have nitrogen in the side chain, while compound DS15, which is the least active and presents the highest value in the dataset for this descriptor, does. The first two have a lower number of coded lags in the descriptor (5 for both), reinforcing that the use of nitrogen substituents will likely generate less active compounds.

Sanderson’s electronegativity weights the MATS4e descriptor. When this property weights a topological descriptor, it is related to the importance of electrostatic interactions (i.e., hydrogen bonds) for binding the compounds understudy to the binding site of interest. As in the case under study, the descriptor coefficient and the values of the descriptors are negative, indicating that descriptors with high values (i.e., “less negatives”) will likely favor the affinity of the compounds. Still, GATS7e, the least important descriptor of all, also has a negative signal for the coefficient but with a positive sign for each compound. Electronegativity also weights this descriptor, but it also has a lag of 7, so an interpretation similar to F07[C-N] can be considered in this case. This characteristic may indicate that atoms with higher electronegativity in the derivatives may positively influence the activity to some degree. However, this characteristic can be impaired by the size of the molecule, strengthening the proposal that hydrophobicity, along with the formation of aromatic-type or charge-transfer complex interactions, is the crucial factor for Mpro inhibition for bicycloproline derivatives.

Model validations

Although the interpretation of the model presents a reasonable relationship with the Mpro inhibition mechanism and with the structural variation compared to the dataset, increasing its reliability, the main point to be considered in a prediction model is its approval in validation procedures [72]. The first step corresponds to the internal validation, where the explained variance is assessed by analyzing the data fit and statistical significance of the calibration obtained. The predicted variance is the first test to evaluate the predictive ability using leave-one-out cross-validation (LOO). Another OECD recommendation is to assess the robustness and chance correlation [73]. Using these approaches, the model represented in multivariate linear regression by Eq. (1) was obtained (the values of the descriptors that generate the model are provided in Table 5). No outliers were identified, so the model can be built with the complete set, which is a great advantage in this study, considering the small number of samples. The results obtained for the internal validation parameters show that the model can explain and predict an adequate amount of information (89.6% and 85.9%, respectively), which is considerably above the minimum value recommended in the literature. The scaled r2m metrics for internal validation are helpful to indicate whether there may be an error in obtaining Q2LOO (since the high values of this parameter may not necessarily mean that the predicted values for the compounds in cross-validation are close to actual values) [16]. The results also showed good values, helping to confirm the model’s internal prediction ability. The F value obtained is considerably higher than the tabulated reference value (2.95, for p = 3, and n-p-1 = 28, with α = 0.05), showing that the calibration achieved is significant. The R2-Q2LOO difference value is well below the recommended minimum, indicating that the chance of the data overfitting is minimal. The leave-N-out test (Fig. 2a) (N = 8, 25% of the dataset) showed that the model is robust, with the average Q2LNO being 0.852 (i.e., only 0.007 units of difference between Q2LOO). The maximum variation was observed for Q2L7O (where the standard deviation of the values obtained for the six replicates of the test at this point is only 0.023). The y-randomization test (Fig. 2b), on the other hand, showed that the model also exhibits no spurious correlations.

| 1 |

Table 5.

Values of selected descriptors for model 1, and the results of LOO cross validation

| Compounds | Eig13_EA(bo) | VE2_B(m) | MATS4e | Eig08_EA(dm) | F07[C-N] | GATS7e | pIC50 real | pIC50 LOO | Residuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DS1 | 2.162 | 0.107 | − 0.12 | 2.192 | 6 | 1.361 | 6.344 | 6.325 | 0.019 |

| DS2 | 2.21 | 0.094 | − 0.087 | 2.359 | 6 | 1.259 | 7.283 | 6.937 | 0.346 |

| DS3 | 1.972 | 0.101 | − 0.102 | 2.354 | 5 | 0.988 | 7.783 | 7.697 | 0.086 |

| DS4 | 1.973 | 0.095 | 0.096 | 2.592 | 5 | 0.759 | 7.733 | 7.725 | 0.008 |

| DS5 | 1.993 | 0.095 | − 0.054 | 2.362 | 5 | 0.911 | 7.879 | 7.837 | 0.042 |

| DS6 | 2.04 | 0.093 | − 0.066 | 2.363 | 5 | 1.062 | 7.839 | 7.764 | 0.075 |

| DS7 | 2.158 | 0.095 | − 0.116 | 2.37 | 6 | 1.001 | 7.364 | 7.337 | 0.027 |

| DS8 | 2.028 | 0.094 | − 0.052 | 2.363 | 5 | 1.042 | 7.429 | 7.742 | − 0.313 |

| DS9 | 2.158 | 0.094 | − 0.069 | 2.557 | 5 | 0.725 | 7.818 | 7.886 | − 0.068 |

| DS10 | 1.993 | 0.097 | − 0.091 | 2.363 | 5 | 1.116 | 7.294 | 7.784 | − 0.490 |

| DS11 | 2.017 | 0.097 | − 0.1 | 2.387 | 5 | 1.157 | 7.876 | 7.700 | 0.176 |

| DS12 | 1.99 | 0.1 | − 0.118 | 2.363 | 5 | 1.189 | 7.721 | 7.640 | 0.081 |

| DS13 | 1.993 | 0.096 | − 0.077 | 2.363 | 5 | 1.063 | 7.907 | 7.768 | 0.139 |

| DS14 | 2.017 | 0.096 | − 0.088 | 2.388 | 5 | 1.139 | 7.886 | 7.725 | 0.161 |

| DS15 | 1.957 | 0.122 | − 0.124 | 2.033 | 6 | 0.974 | 6.126 | 6.311 | − 0.185 |

| DS16 | 2.212 | 0.088 | − 0.161 | 2.084 | 7 | 1.174 | 6.815 | 7.072 | − 0.257 |

| DS17 | 2.212 | 0.092 | − 0.116 | 2.084 | 8 | 1.115 | 6.525 | 6.359 | 0.166 |

| DS18 | 2.211 | 0.113 | − 0.134 | 2.067 | 5 | 1.119 | 6.279 | 6.202 | 0.077 |

| DS19 | 2.212 | 0.1 | − 0.092 | 2.201 | 6 | 0.958 | 6.709 | 6.708 | 0.001 |

| DS20 | 2.217 | 0.104 | − 0.116 | 2.201 | 6 | 1.144 | 6.426 | 6.473 | − 0.047 |

| DS21 | 1.984 | 0.099 | − 0.125 | 2.201 | 5 | 0.815 | 8.119 | 7.688 | 0.431 |

| DS22 | 1.996 | 0.096 | − 0.128 | 2.201 | 5 | 0.796 | 7.759 | 7.941 | − 0.182 |

| DS23 | 1.985 | 0.096 | − 0.028 | 2.437 | 5 | 0.642 | 8.119 | 7.939 | 0.180 |

| DS24 | 2.213 | 0.097 | − 0.123 | 2.201 | 6 | 1.14 | 6.642 | 6.864 | − 0.222 |

| DS25 | 2.007 | 0.097 | − 0.137 | 2.201 | 5 | 1.242 | 7.441 | 7.604 | − 0.163 |

| DS26 | 2.211 | 0.1 | − 0.175 | 2.202 | 5 | 1.225 | 7.161 | 7.045 | 0.116 |

| DS27 | 2.213 | 0.094 | − 0.088 | 2.201 | 5 | 1.034 | 7.015 | 7.235 | − 0.220 |

| DS28 | 1.994 | 0.099 | − 0.145 | 2.201 | 5 | 1.127 | 8.036 | 7.596 | 0.440 |

| DS29 | 2.011 | 0.095 | − 0.09 | 2.21 | 5 | 0.991 | 7.46 | 7.701 | − 0.241 |

| DS30 | 2.011 | 0.095 | − 0.115 | 2.221 | 5 | 1.081 | 7.764 | 7.717 | 0.047 |

| DS31 | 1.996 | 0.095 | − 0.104 | 2.201 | 5 | 1.006 | 7.523 | 7.767 | − 0.244 |

| DS32 | 2.011 | 0.095 | − 0.156 | 2.201 | 5 | 1.272 | 7.706 | 7.716 | − 0.010 |

Fig. 2.

Results of leave-N-out (LNO) cross-validation (A) and y-randomization (B) tests for model 1

n = 32; Cumulated information: 67.411% (VL1: 41.135%; VL2: 17.236%; VL3: 9.041%);

R2 = 0.896; RMSEC = 0.191; F3,28 = 80.410; Q2LOO = 0.859; RMSECV = 0.221; R2-Q2LOO = 0.037; Average_r2m(LOO)-scaled = 0.816; Δr2m(LOO)-scaled = 0.101.

Model 1 has the largest structural information since this dataset consists of only 32 compounds. Unfortunately, the set under study can be considered small [49], although this is common in QSAR studies. In this context, Table 6 shows the mean values of the internal and external validation parameters for each of the 100 different models and 100 different test sets (all with ntraining = 24 and ntest = 8) and the respective standard deviations. All metrics adopted in this study were within the recommended limits (Table 2), even considering the number of test sets evaluated (and, consequently, a greater possibility of selecting sets that would lead to poor results). All results also show adequate standard deviations regarding the numerical scale of each parameter. Minimal variations can also be observed between the values of the internal validation of model 1 and the averages of the same parameters. This indicates that each of the 100 different models generated has strong similarities with the original model, and this model 1 can be used for prediction purposes. This is desirable in a situation like this, with a dataset with few compounds, since a model formed by all samples will encode as much structural information as possible. Thus, its AD will also be as broad as possible within the limitations imposed by the set size of such a study. Another information that can be obtained from this test is that, considering the minimal variation obtained in the mean parameters of the internal validations, the robustness property of model 1 is strengthened.

Table 6.

Average (Av) values of the results obtained during the performed internal and external validations with 100 different training and test sets

| Parameter | Average result | Standard deviation | Difference of model 1’s internal validation values with the means |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average values of the internal validation | |||

| Av_R2 | 0.901 | 0.021 | − 0.005 |

| Av_RMSEC | 0.184 | 0.018 | 0.007 |

| Av_F | 64.450 | 19.580 | 15.960 |

| Av_Q2LOO | 0.832 | 0.033 | 0.027 |

| Av_RMSECV | 0.240 | 0.021 | − 0.019 |

| Av_R2-Q2LOO | 0.069 | 0.019 | − 0.032 |

| Av_Average_r2m(LOO)-scaled | 0.767 | 0.048 | 0.049 |

| Av_Δr2m(LOO)-scaled | 0.079 | 0.045 | 0.022 |

| Average values of the external validation | |||

| Av_R2pred | 0.831 | 0.092 | |

| Av_RMSEP | 0.228 | 0.051 | |

| Av_k | 0.998 | 0.014 | |

| Av_k′ | 1.001 | 0.014 | |

| Av_|R20-R2′0| | 0.082 | 0.157 | |

| Av_ARE pred | 2.911% | 0.736 | |

| Av_Average_r2m(pred)-scaled | 0.721 | 0.151 | |

| Av_Δr2m(pred)-scaled | 0.115 | 0.079 | |

| Av_MAE | 0.183 | 0.045 | |

| Av_MAE95 | 0.148 | 0.043 | |

Virtual screening by 2D similarity

A set of 2694 hits with a similarity greater than 0.5 to the structure used for the search was initially obtained through the approach selected for this study (Fig. 1). The SMILES strings of the complete set of hits were used to calculate the same descriptors as the model in Dragon 6. This approach enabled the calculation of the Euclidean AD, shown in Fig. 3. After identification and removal of duplicates, only 423 compounds (15.7%) were within the AD.

Fig. 3.

Plot of the Euclidean applicability domain (AD) analyses. The AD corresponds to the gray areas. The compounds with a normalized mean distance > 1 are outside the AD. The compounds inside the small light gray rectangle near the data origin correspond to the dataset used for model building and consequent AD determination. The remaining compounds (1 to 2694) correspond to the composites obtained in the first stage of the virtual screening (without removal of duplicates)

Next, the SMILES strings of these compounds were filtered using algorithms available in VEGA QSAR software. Those compounds with any of the three selected toxicities predicted as possible were removed from the set, leaving 130 hits (4.82% of the original set). However, it is important to note that even if a compound synthesized or obtained by virtual screening shows undesirable toxicity profiles or biological activity in any test (in silico or experimental), its properties can be optimized by molecular modifications. This possibility fits the objectives of this work, which involves identifying new scaffolds that can originate, in further studies, new Mpro inhibitors. Naturally, using a scaffold as a starting point that does not present toxic properties either (after confirmation by experimental tests) increases the chances of obtaining compounds with a low toxicity profile, which, at some point, may give rise to new therapeutically useful drugs.

Subsequently, the hits had their activities predicted using model 1. Of these, 44 hits (1.63%) showed values within the biological activity range (6.12 < pIC50 < 8.12). For this reason, removing these compounds from the set was necessary. The SMILES strings, descriptors, and predicted activities of these 44 hits are shown in Table 7. Since results outside the biological activity range are derived from extrapolation, they are less reliable.

Table 7.

Structures (SMILES format) and molecular descriptors of the selected compounds

| Hit | NAME | Eig12_EA(bo) | VE2_B(m) | MATS4e | Eig08_EA(dm) | F07[C-N] | GATS7e | pIC50 pred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CC(NC(= O)C1CCN(CC1)C(= O)[C@H]1C[C@H]2[C@@H](N1)CCCC2)C | 0.658 | 0.17 | − 0.116 | 1.611 | 4 | 0.673 | 6.273 |

| 2 | CC(NC(= O)C1CCN(CC1)C(= O)[C@@H]1C[C@@H]2[C@@H](N1)CCCC2)C | 0.658 | 0.17 | − 0.116 | 1.611 | 4 | 0.673 | 6.273 |

| 3 | O = C([C@H]1NCC2(C1)CCNCC2)N1CCN(CC1)c1ccccc1 | 0.86 | 0.139 | − 0.082 | 1.225 | 4 | 1.216 | 6.345 |

| 4 | O = C([C@H]1CCCN1C(= O)C(C)(C)C)N[C@H]1CCN(C1)C1CC1 | 0.273 | 0.155 | − 0.188 | 1.278 | 4 | 1.444 | 7.348 |

| 5 | O = C([C@H]1NCC2(C1)CCNCC2)NC(CC1Cc2c(C1)cccc2)(C)C | 0.987 | 0.104 | 0.036 | 1.82 | 4 | 1.593 | 7.844 |

| 6 | O = C(N[C@]1(C)[C@@H]2CC[C@H](C1(C)C)C2)CNCCN1CCCC1 | 0.438 | 0.153 | − 0.034 | 0.983 | 4 | 1.245 | 6.269 |

| 7 | O = C(C1NCC2(C1)CCNCC2)NC(CC1Cc2c(C1)cccc2)(C)C | 0.987 | 0.104 | 0.036 | 1.82 | 4 | 1.593 | 7.844 |

| 8 | CC(NC(= O)C1CCN(CC1)C(= O)[C@@H]1C[C@H]2[C@@H](N1)CCCC2)C | 0.658 | 0.17 | − 0.116 | 1.611 | 4 | 0.673 | 6.273 |

| 9 | CN1CCC(CC1)CN(C(= O)CN1CCCCC1)CCc1ccccc1 | 1.04 | 0.12 | 0.003 | 1.535 | 6 | 1.473 | 6.268 |

| 10 | CN1CC2(C[C@@H]1C(= O)NC1CCN(CC1)Cc1ccccc1)CCNCC2 | 1.368 | 0.115 | 0.021 | 1.519 | 3 | 0.985 | 6.621 |

| 11 | O = C(N(C1CCCC1)CC1CCN(CC1)CCc1ccccc1C)[C@@H]1CCCN1 | 1.628 | 0.103 | − 0.059 | 1.641 | 6 | 0.862 | 6.294 |

| 12 | Clc1ccc(cc1)CN1CC2(CC1 = O)CCN(CC2)C(= O)[C@@H]1CCCN1 | 1.363 | 0.119 | − 0.109 | 1.943 | 4 | 0.771 | 7.278 |

| 13 | NC(= N)NCCCC1NC(= O)C2N(C1 = O)CCC2 | 0 | 0.185 | − 0.221 | 1.115 | 5 | 0.696 | 6.701 |

| 14 | CC(N1CCNCC1)C(= O)NCCC1CCCCCCC1 | 0.255 | 0.167 | − 0.044 | 1.216 | 4 | 1.443 | 6.259 |

| 15 | [H][C@@]12C[C@]1([H])N([C@@H](C2)C#N)C(= O)[C@@H](N)C1CCN(CC1)C(= O)C(C)(C)C | 0.576 | 0.177 | − 0.238 | 2.118 | 6 | 0.394 | 6.851 |

| 16 | CC(C)[C@H](N)C(= O)N1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)NCC1 = CC = CC = C1 | 0.5 | 0.147 | − 0.182 | 1.129 | 5 | 1.044 | 6.948 |

| 17 | CCN1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)NCC1CCN(CC1)C(= O)C(C)C | 0.236 | 0.174 | − 0.195 | 1.198 | 4 | 0.81 | 6.825 |

| 18 | CCN1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)N(C)CC1CCN(CC(C)C)CC1 | 0.188 | 0.171 | − 0.074 | 1.178 | 4 | 0.866 | 6.636 |

| 19 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)NCC1CCN(CC1)C1CCCC1 | 0.214 | 0.159 | − 0.153 | 1.077 | 5 | 1.008 | 6.958 |

| 20 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)NCC1CCN(CC1)C(= O)C1CC1 | 0.217 | 0.173 | − 0.273 | 1.177 | 4 | 0.872 | 7.116 |

| 21 | CCN1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)N1CCC(CC1)C(= O)NC | 0.153 | 0.189 | − 0.04 | 1.179 | 5 | 0.237 | 6.734 |

| 22 | CCN1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)N1CCC(CC1)C(= O)N(C)C | 0 | 0.197 | − 0.204 | 1.179 | 2 | 0.343 | 7.088 |

| 23 | CCN1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)N1CCC(CC1)C(= O)N | 0.153 | 0.189 | − 0.04 | 1.179 | 5 | 0.237 | 6.251 |

| 24 | CCN1CCC[C@H]1C(= O)N1CCC(C)(CC1)C(= O)N | 0 | 0.193 | − 0.171 | 1.077 | 3 | 0.508 | 6.703 |

| 25 | CCN(CC)[C@H]1CC[C@@H](CC1)NC(= O)[C@]1(C)CCCN1 | 0.184 | 0.177 | − 0.157 | 0.803 | 4 | 0.608 | 6.319 |

| 26 | CCN(CC)CCC[C@@H](C)NC(= O)[C@H]1CCCN1C(= O)C | 0.386 | 0.164 | − 0.053 | 1.117 | 4 | 0.721 | 6.412 |

| 27 | CCN(CC)CCC[C@@H](C)NC(= O)[C@@H]1CCCN1C(= O)C | 0.386 | 0.164 | − 0.053 | 1.117 | 4 | 0.721 | 6.412 |

| 28 | CCN(CC)C1CCC(CC1)NC(= O)[C@]1(C)CCCN1 | 0.184 | 0.177 | − 0.157 | 0.803 | 4 | 0.608 | 6.319 |

| 29 | CC1(CCN(CC1)C(= O)[C@H]1CCCN1)C(= O)N | − 0.239 | 0.208 | − 0.221 | 0.803 | 3 | 0.569 | 6.373 |

| 30 | CC1(CCN(CC1)C(= O)[C@@H]1CCCN1)C(= O)N | − 0.239 | 0.208 | − 0.221 | 0.803 | 3 | 0.569 | 6.373 |

| 31 | CC(C)(C)NC(= O)C1CCN(CC1)C(= O)[C@]1(C)CCCN1 | 0 | 0.19 | − 0.111 | 1.077 | 5 | 0.219 | 6.335 |

| 32 | O = C([C@H]1CCCN1)N1CCC(CCN2CCCCC2)CC1 | 0.306 | 0.171 | − 0.057 | 1.077 | 4 | 0.547 | 6.345 |

| 33 | O = C([C@H]1CCCN1)N1CCC(CCN2CCCC2)CC1 | 0.093 | 0.174 | − 0.044 | 1.077 | 4 | 0.552 | 6.699 |

| 34 | O = C([C@@H]1CCCN1)N1CCC(CCN2CCCCC2)CC1 | 0.306 | 0.171 | − 0.057 | 1.077 | 4 | 0.547 | 6.345 |

| 35 | O = C([C@@H]1CCCN1)N1CCC(CCN2CCCC2)CC1 | 0.306 | 0.171 | − 0.057 | 1.077 | 4 | 0.547 | 6.699 |

| 36 | O = C(NCC1CC1)[C@H]1CCCN1 | − 1 | 0.232 | − 0.203 | − 0.527 | 0 | 0.404 | 6.281 |

| 37 | O = C(NCC1CC1)[C@@H]1CCCN1 | − 1 | 0.232 | − 0.203 | − 0.527 | 0 | 0.404 | 6.281 |

| 38 | O = C(NC1CCCC1)[C@H]1CCCN1 | − 0.785 | 0.226 | − 0.081 | 0.301 | 0 | 0.361 | 6.673 |

| 39 | O = C(NC1CCCC1)[C@@H]1CCCN1 | − 0.785 | 0.226 | − 0.081 | 0.301 | 0 | 0.361 | 6.673 |

| 40 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)NCC1CCC1 | − 0.764 | 0.225 | − 0.231 | 0 | 1 | 0.836 | 6.257 |

| 41 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)NCC1CC1 | − 0.823 | 0.22 | − 0.278 | − 0.527 | 0 | 0.406 | 6.658 |

| 42 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)NC1CCCC1 | − 0.618 | 0.213 | − 0.175 | 0.322 | 0 | 0.328 | 7.233 |

| 43 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)NC1CCC1 | − 0.958 | 0.243 | − 0.208 | 0 | 0 | 0.221 | 6.418 |

| 44 | C[C@]1(CCCN1)C(= O)N1CCCCC1 | − 0.688 | 0.227 | − 0.216 | − 0.172 | 0 | 0.198 | 6.332 |

Finally, using SwissADME [60], physicochemical properties and ADME predictions of the 44 compounds were obtained. All these hits passed the drug-likeness rules of Lipinski [74], one of the most widely used approaches, and Veber [75]. On the other hand, five compounds (3, 13, 23, 29, and 30) showed a violation of Ghose’s rules [76] (all with WLOGP < − 0.4), and nine (36 to 44) showed a violation of any of Muegge’s rules [77]. In addition, 20 compounds (5, 7, 9 to 12, 14, 26, 27, 29, 30, and 36 to 44) violated one or more of Teague’s lead likeness rules [78]. Of the total, 21 compounds passed all criteria.

Figure 4 shows the Egan BOILED-Egg plot of the 44 hits (Table 5). This approach aids in evaluating the prediction of gastrointestinal absorption (HIA) and brain penetration or accessibility (BBB) of the hits under study. The yellow field corresponds to the molecules that present hydrophobicity (expressed by the WLogP algorithm) and polarity (represented by the topological polar surface area, TPSA), which allow them to present good HIA and BBB. In contrast, the white field corresponds to those molecules with only good HIA [60]. The predicted molecules as potential substrates of P-gp (PGP +) are shown as blue dots, while those predicted as non-substrates (PGP-) are shown as red dots [60]. It can be seen that while all compounds show good HIA and can be passively absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract, only compounds 2, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 20, 26, 27, 33, 39, 41, and 43 have the same property for the blood–brain barrier (BBB) characteristic. However, only 1, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 17, 19, 26, 32, 40, and 42 were predicted as PGP + ; i.e., they can be eliminated from the interior of the central nervous system (CNS) more efficiently, a desirable effect for drugs that are not intended to act in the CNS, decreasing the risk of neurotoxicity. In addition, compounds with this characteristic have a more significant potential to be distributed throughout the body [60].

Fig. 4.

BOILED-egg plot for gastrointestinal tract absorption and brain permeation prediction of the 44 selected compounds after drug-likeness and lead-likeness evaluations

Of these 12 compounds, only 1, 6, 17, 19, and 32 (Fig. 5) are among those that did not violate any rules of drug-likeness or lead-likeness. Moreover, while this point does not lead to a mandatory elimination of the remaining hits, particularly since the properties responsible for each violation can be optimized via structural modifications (the same being true for potential toxic effects), the five selected can be considered the most promising. These five compounds were also not predicted to be inhibitors of common CYP450 isoforms (1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6, and 3A4), indicating that they are at low risk of triggering hepatotoxicity [79]. None showed PAINS and BRENK structural toxicity alerts [80, 81]. Finally, considering that the approach indicating the degree of synthetic accessibility ranges from 1 (very easy) to 10 (very difficult), all hits show a good score for this characteristic, with 17 standing out. Therefore, these five hits were selected as the main candidates to be submitted to the inhibition assay of Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 to confirm the presence of activity and, consequently, their usefulness as new scaffolds for design of new antiviral agents.

Fig. 5.

Structures of the five-hit compounds were selected as the most promising at the end of the study. ConsLogP arithmetic mean of five different LogP prediction methodologies (including WLogP) available in SwisADME, SA synthetic accessibility, CCSigma “By Click Chemistry from Sigma Aldrich” library

Conclusion

In this study, QSAR and virtual screening studies, based only on 2D structures and molecular descriptors derived from SMILES strings, were performed based on a set of bicycloproline derivatives described as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. The adopted internal and external validation metrics indicated that the obtained model is significant, robust, does not show chance correlation, and has good external predictability. This allowed this model to be used as a support tool for the virtual screening stage, helping to identify a set of 44 hits, where five (1, 6, 17, 19, and 32) stood out as the most promising (considering the combination of several parameters related to reliability of predicted activities, toxicity, drug, and lead-likeness) to be used as new scaffolds in the design of new antiviral agents. Further assay studies will confirm whether each hit is indeed capable of inhibiting Mpro. If this is confirmed, structural optimization is expected to lead to developing new classes of anti-COVID-19 agents with potential therapeutic use. The obtained QSAR model could also be helpful as a support tool for synthesizing the new derivatives.

Author contribution

All authors (A.S.C., J.P.A.M., E.B.M.) contributed equally to the study, through periodic meetings to discuss the study data.

Funding

The authors wish to thank Fundação Araucária, PROAP/CAPES, CNPq (grant 311048/2018–8), and the Pro-Rectory of Research (PRPq) of Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) for the support received.

Data availability

Important data from the study are available in the main text.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 01 May 2022

- 2.Mavroudeas S. Int Crit Thought. 2020;10:559–565. doi: 10.1080/21598282.2020.1866235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID-19 Explorer. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/covid/. Accessed 22 June 2022

- 4.Phan L, Nguyen T, Luong Q, Nguyen T, Nguyen H, Le H, Nguyen T, Cao T, Pham Q. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:872–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. The Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNMC Nebraska Medicine. https://www.nebraskamed.com/COVID/7-strange-symptoms-of-covid-19-including-rashes-covid-toes-and-hair-loss. Accessed 01 May 2022

- 7.Jamilloux Y, Henry T, Belot A, Viel S, Fauter M, El Jammal T, Walzer T, François B, Sève P. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19:102567. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. JAMA. 2020;323:1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziebuhr J, Snijder EJ, Gorbalenya AE. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:853–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziebuhr J. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander MA, Kornoushenko YV, Karpenko AD, Bosko IP, Tuzikov AV. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39:5779–5791. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1792989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mótyán JA, Mahdi M, Hoffka G, Tozsér J. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3507. doi: 10.3390/ijms23073507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohapatra RK, Tiwari R, Sarangi AK, Sharma SK, Khandia R, Saikumar G, Dhama K. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1761–1765. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham BBS. Science. 2020;368:945–946. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiao J, Li Y, Zeng R, Liu F, Luo R, Huang C, Wang Y, Zhang J, Quan B, Shen C, Mao X, Liu X, Sun W, Yang W, Ni X, Wang K, Xu L, Duan Z, Zou Q, Zhang H, Qu W, Long Y, Li M, Yang R, Liu X, You J, Zhou Y, Yao R, Li W, Liu J, Chen P, Liu Y, Lin G, Yang X, Zou J, Li L, Hu Y, Lu G, Li W, Wei Y, Zheng Y, Lei J, Yang S. Science. 2021;371:1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.abf1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy K, Kar S, Das RN. Understanding the basics of QSAR for applications in pharmaceutical sciences and risk assessment. 1. London: Elsevier; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murato EN, Bajorath J, Sheridan RP, Tetko IV, Filimonov D, Poroikov V, Oprea TI, Baskin II, Varnek A, Roitberg A, Isayev O, Curtalolo S, Fourches D, Cohen Y, Aspuru-Guzik A, Winkler DA, Agrafiotis D, Cherkasov A, Tropsha A. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:3525–3564. doi: 10.1039/D0CS00098A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muratov EN, Amaro R, Andrade CH, Brown N, Ekins S, Fourches D, Isayev O, Kozakov D, Medina-Franco JL, Merz KM, Oprea TI, Poroikov V, Schneider G, Todd MH, Varnek A, Winkler DA, Zakharov AV, Cherkasov A, Tropsha A. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50:9121–9151. doi: 10.1039/D0CS01065K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korn D, Pervitsky V, Bobrowski T, Alves VM, Schmitt C, Bizon C, Baker N, Chirkova R, Cherkasov A, Muratov E, Tropsha A. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61:5734–5741. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grisoni F, Ballabio D, Todeschini R, Consonni V (2018) In: Nicolotti O (ed) Computational toxicology: methods and protocols, Humana Press, New York

- 21.Weininger D. J Chem Inf Comp Sci. 1988;28:31–36. doi: 10.1021/ci00057a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vyas V, Jain A, Jain A, Gupta A. Sci Pharm. 2008;76:333–360. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.0803-03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Werrmuth C (2008) The practice of medicinal chemistry Academic Press, Cambridge

- 24.ChemSkecth Freeware. https://www.acdlabs.com/resources/free-chemistry-software-apps/chemsketch-freeware/. Accessed 20 May 2022

- 25.Todeschini R, Consonni V. Molecular descriptors for chemoinformatics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puzyn T, Leszczyński J, Cronin M. Recent advances in QSAR studies: methods and applications. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helguera A, Combes R, Gonzalez M, Cordeiro M. Curr Top Med Chem. 2008;8:1628–1655. doi: 10.2174/156802608786786598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira MMC, Montanari CA, Gaudio AC. Quim Nova. 2002;25:439–448. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422002000300017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martins JPA, Ferreira MMC. Quím Nova. 2013;36:554–560. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422013000400013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teófilo RF, Martins JPA, Ferreira MMC. J Chemometrics. 2009;23:32–48. doi: 10.1002/cem.1192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu P, Long W. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;2009:1978–1998. doi: 10.3390/ijms10051978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kiralj R, Ferreira MMC. J Braz Chem Soc. 2009;20:770–787. doi: 10.1590/S0103-50532009000400021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaudio AC, Zandonade E. Quim Nova. 2001;24:658–671. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422001000500013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gramatica P, Chirico N, Papa E, Cassani S, Kovarich S. J Comput Chem. 2013;34:2121–2132. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy K, Chakraborty P, Mitra I, Ojha PK, Kar S, Das RN. J Comput Chem. 2013;34:1071–1082. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roy PP, Leonard JT, Roy K. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2008;90:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2007.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy PP, Roy K. QSAR Comb Sci. 2008;27:302–313. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200710043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golbraikh A, Tropsha A. J Mol Graph Model. 2002;20:269–276. doi: 10.1016/S1093-3263(01)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tropsha A, Gramatica P, Gombar VK. QSAR Comb Sci. 2003;22:69–77. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200390007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melagraki G, Afantitis A, Sarimveis H, Koutentis PA, Markopolus J, Igglessi-Markopoulou O. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2007;21:251–267. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tropsha A, Golbraikh A (2010) In: Faulon J, Bender A (eds) Handbook of chemoinformatics algorithms. CRC Press, Boca Raton

- 42.Roy K, Das RN, Ambure P, Aher RB. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2016;152:18–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2016.01.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leo AJ. Chem Rev. 1983;93:1281–1308. doi: 10.1021/cr00020a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitra I, Saha A, Roy K. Sci Pharm. 2011;79:31–57. doi: 10.3797/scipharm.1011-02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papa E, Dearden JC, Gramatica P. Chemosphere. 2007;67:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veerasamy R, Rajak H, Jain A, Sivadasan S, Varghes CP, Agrawal RK. Int J Drug Discov. 2011;2:511–519. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eriksson L, Jaworska J, Worth AP, Cronin MTD, McDowell RM, Gramática P. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1361–1375. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi L, Fang H, Tong W, Wu J, Perkins R, Blair R, Branham W, Dial S, Moland C, Sheehan D. J Chem Inf Comp Sci. 2001;41:186–195. doi: 10.1021/ci000066d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roy K, Ambure P. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 2016;159:108–126. doi: 10.1016/j.chemolab.2016.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Melo EB, Martins JPA, Rodrigues CHP, Bruni AT. J Braz Chem Soc. 2020;31:927–940. [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Campos LJ, de Melo EB. J Mol Graph Model. 2014;54:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birck MG, de Campos LJ, de Melo EB. Quim Nova. 2016;39:567–574. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nandy A, Kar S, Roy K. Mol Simul. 2014;40:261–274. doi: 10.1080/08927022.2013.801076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laufkötter O, Miyao T, Bajorath J. ACS Omega. 2019;4:15304–15311. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b02470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zoete V, Daina A, Bovigny C, Michielin O. J Chem Inf Model. 2016;56:1399. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jaworska J, Nikolova-Jeliazkova N, Aldenberg T. ATLA Altern Lab Anim. 2005;33:445–459. doi: 10.1177/026119290503300508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sahigara F, Mansouri K, Ballabio D, Mauri A, Consonni V, Todeschini R. Molecules. 2012;17:4791–4810. doi: 10.3390/molecules17054791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vega QSAR. https://www.vegahub.eu/portfolio-item/vega-qsar/. Accessed 20 May 2022

- 59.Daina A, Zoete V. ChemMedChem. 2016;11:1117–1121. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201600182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. Sci Rep. 2017;7:42717. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toropov AA, Benfenati E. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2007;4:77–116. doi: 10.2174/157016307781483432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Veselinovic AM, Veselinovic JB, Zivkovic JV, Nikolic GM. Curr Top Med Chem. 2015;15:1768–1779. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150506151533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Toropov AA, Toropova AP, Veselinović AM, Leszczynska A, Leszczynski J. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40:780–786. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1818627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toropov AA, Toropova AP, Roncaglioni A, Benfenati E. New J Chem. 2021;45:20713–20720. doi: 10.1039/D1NJ03394H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toropov AA, Toropova AP, Benfenati E. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2021;32:689–698. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2021.1952649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dong J, Cao D, Miao H, Liu S, Deng B, Yun Y, Wang N, Lu A, Zeng W, Chen A. J Cheminform. 2015;7:60. doi: 10.1186/s13321-015-0109-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.alvaDesc molecular descriptors. https://www.alvascience.com/alvadesc-descriptors/. Accessed 20 May 2022

- 68.de Campos LJ, de Melo EB. J Mol Struc. 2017;1141:252–260. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2017.03.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Costa AS, de Melo EB. Int J Quant Struct Prop Relat. 2016;1:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fernandes MS, Silva FS, Freitas ACSG, de Melo EB, Trossini GHG, Paula FR. Mol Inf. 2021;40:2000096. doi: 10.1002/minf.202000096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dragon 6 user’s manual. http://www.talete.mi.it/help/dragon_help/. Accessed 20 May 2022

- 72.Worth AP, Bassan A, Bruijn J, Saliner AG, Netzeva T, Patlewicz G, Pavan M, Tsakovska I, Eisenreich S. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2007;18:111–125. doi: 10.1080/10629360601054255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gómez-Jiménez G, Gonzalez-Ponce K, Castillo-Pazos D, Madariaga-Mazon A, Barroso-Flores J, Cortes-Guzman F, Martinez-Mayorga K. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol. 2018;113:85–117. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Veber D, Johnson S, Cheng H, Smith B, Ward K, Kopple K. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2615–2623. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ghose AK, Viswanadhan VN, Wendoloski JJ. J Comb Chem. 1999;1:55–68. doi: 10.1021/cc9800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Muegge I, Heald SL, Brittelli D. J Med Chem. 2001;44:1841–1846. doi: 10.1021/jm015507e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Teague S, Davis A, Leeson P, Oprea T. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1999;38:3743–3748. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19991216)38:24<3743::AID-ANIE3743>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Africa J, Arturo H, Bernardo L, Ching J, de la Cruz O, Hernandez J, Magsipoc R, Sales C, Agbay J, Neri G, Quimque M, Macabeo A. Philipp J Sci. 2022;151:35–58. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Baell JB, Holloway GA. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bruns RF, Watson IA. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9763–9772. doi: 10.1021/jm301008n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Important data from the study are available in the main text.

Not applicable.