Abstract

This modeling study estimates the excess deaths attributable to COVID-19 disease in Massachusetts during the Delta (June to December 2021) and Omicron (December 2021 to February 2022) waves.

The COVID-19 pandemic has produced excess deaths, the number of all-cause fatalities exceeding the expected number in any period.1,2 Given reports that the Omicron variant may confer less risk than prior variants, we compared excess mortality in Massachusetts, a highly vaccinated state, during the Delta and initial Omicron periods.3

Methods

We applied autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models to US Census populations (2014-2019) and seasonal ARIMA (sARIMA) models to Massachusetts Department of Health all-cause mortality statistics (from January 5, 2015, through February 8, 2020) to account for prepandemic age and mortality trends and to project the age-stratified (0-17, 18-49, 50-64, and ≥65 years) weekly population and the weekly number of expected deaths in Massachusetts during the pandemic period (February 9, 2020, through February 20, 2022), focusing on the Delta (June 28, 2021, through December 5, 2021), the Delta-Omicron transition (December 6-26, 2021), and Omicron COVID-19 periods (December 27, 2021, through February 20, 2022). Period barriers were determined by variant dominance in regional wastewater.4

The population of Massachusetts is approximately 6.9 million individuals. We corrected expected deaths for the decreased population owing to cumulative pandemic-associated excess deaths (eAppendix in the Supplement). Population covariates were used to calculate 95% CIs for expected deaths. Excess mortality for each period was defined as the difference between the observed deaths and point estimate for sARIMA-determined expected deaths. Incident rate ratios were calculated to compare the Omicron and Delta periods. According to the Massachusetts Department of Health, deaths recorded from 2020 to 2022 were considered provisional. Excess mortality for individuals aged 0 to 17 years was determined and included in the overall analysis, but not presented separately because the death rates were considered too small to be reliable.

Analyses were conducted with R version 4.1.2. Statistical significance was defined as a 95% CI that did not include 0. This study used publicly available data and was not subject to institutional review board approval according to the Massachusetts Registry of Vital Records and Statistics.

Results

During the 23-week Delta period, 1975 all-cause excess deaths occurred (27 265 observed; 25 290 expected; 95% CI, 671-3297 excess deaths). During the 8-week Omicron period, 2294 excess deaths occurred (12 231 observed; 9937 expected; 95% CI, 1795-2763 excess deaths). The per-week Omicron to Delta incident rate ratio for excess mortality was 3.34 (95% CI, 3.14-3.54) (Table).

Table. Excess and COVID-19–Attributed Deaths in Massachusetts, June 28, 2021, to February 20, 2022.

| Cases by age, y | Expected deaths, No. (95% CI) | Observed deaths, No. | Ratio of observed to expected deaths (95% CI) | Excess deaths, No. (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 28, 2021–February 20, 2022; 238 d | ||||

| Massachusetts total (all ages) | 38 715 (37 258-40 127) | 43 738 | 1.13 (1.09-1.17) | 5023 (3611-6480) |

| ≥65 | 30 071 (28 831-31 336) | 33 823 | l.12 (1.08-1.17) | 3752 (2487-4992) |

| 50-64 | 5528 (5323-5736) | 6420 | 1.16 (1.12-1.21) | 892 (684-1097) |

| 18-49 | 2800 (2676-2922) | 3103 | 1.11 (1.06-1.16) | 303 (181-427) |

| Delta (June 28, 2021–December 5, 2021; 161 d) | ||||

| Massachusetts total (all ages) | 25 290 (23 968-26 594) | 27 265 | 1.08 (1.03-1.14) | 1975 (671-3297) |

| ≥65 | 19 514 (18 372-20 681) | 20 898 | 1.07 (1.01-1.14) | 1384 (217-2526) |

| 50-64 | 3651 (3481-3817) | 4107 | 1.12 (1.08-1.18) | 456 (290-626) |

| 18-49 | 1908 (1806-2008) | 2026 | 1.06 (1.01-1.12) | 118 (18-220) |

| Delta-Omicron transition (December 6-26, 2021; 21 d) | ||||

| Massachusetts total (all ages) | 3489 (3284-3686) | 4242 | 1.22 (1.15-1.29) | 753 (556-958) |

| ≥65 | 2733 (2560-2911) | 3291 | 1.20 (1.13-1.29) | 558 (380-731) |

| 50-64 | 488 (432-543) | 616 | 1.26 (1.13-1.43) | 128 (73-184) |

| 18-49 | 236 (199-270) | 310 | 1.31 (1.15-1.56) | 74 (40-111) |

| Omicron (December 27, 2021–February 20, 2022; 56 d) | ||||

| Massachusetts total (all ages) | 9937 (9468-10 436) | 12 231 | 1.23 (1.17-1.29) | 2294 (1795-2763) |

| ≥65 | 7824 (7412-8246) | 9634 | 1.23 (1.17-1.30) | 1810 (1388-2222) |

| 50-64 | 1389 (1297-1487) | 1697 | 1.22 (1.14-1.31) | 308 (210-400) |

| 18-49 | 656 (595-713) | 767 | 1.17 (1.08-1.29) | 111 (54-172) |

Excess deaths do not sum to total because individuals aged 0 to 17 years are not shown.

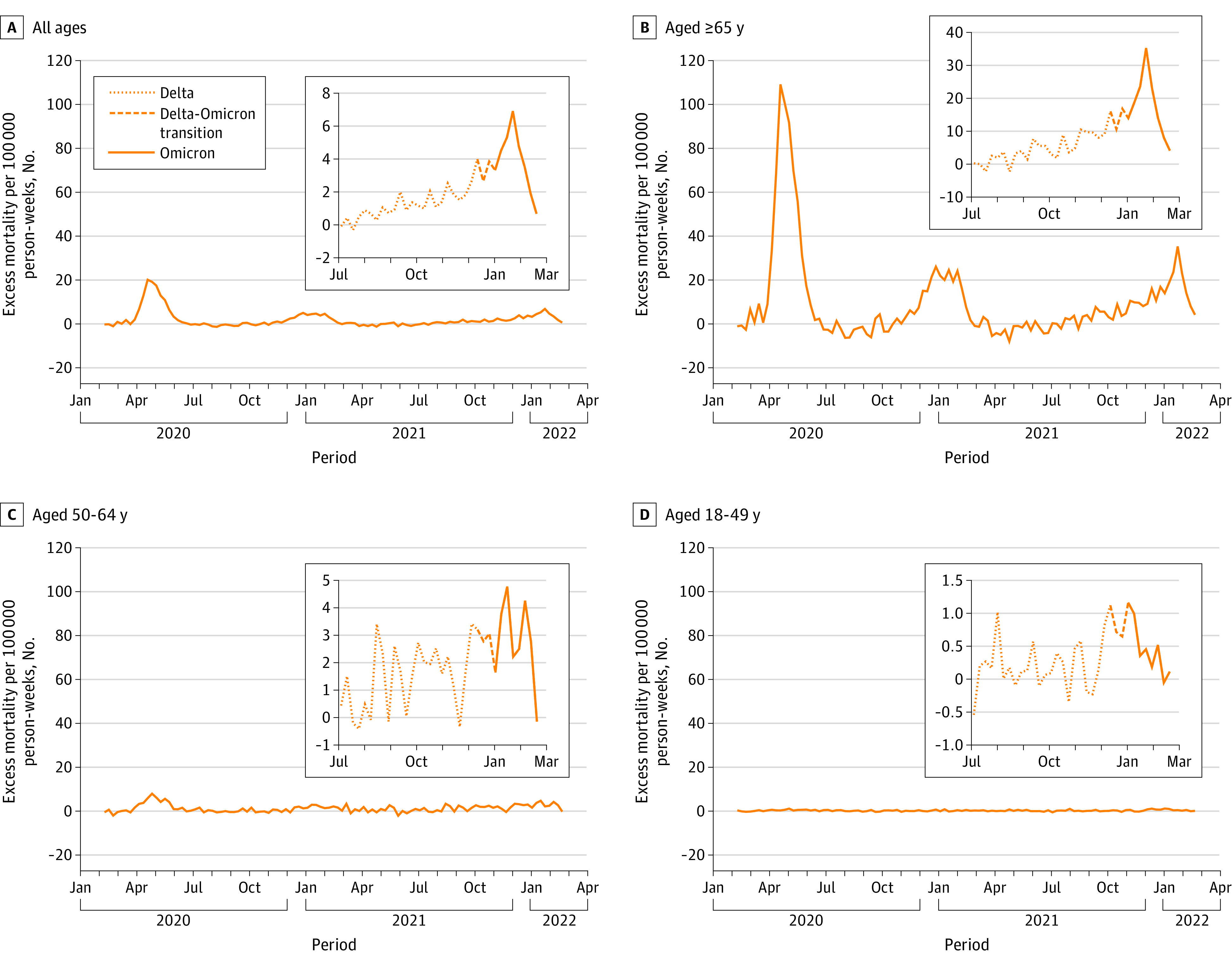

Statistically significant excess mortality occurred in all adult age groups at various times during the study period and in each period overall (Figure, Table). For all adult age groups, the ratio of observed to expected excess mortality increased during the Omicron period compared with the Delta period (Table).

Figure. Weekly All-Cause Excess Deaths in Massachusetts per 100 000 Person-Weeks From February 9, 2020, Through February 20, 2022.

Insets for each age group are enlargements of the Delta period (dotted lines), Delta-Omicron transition period (dashed lines), and Omicron period (solid lines). Baseline (0 excess deaths) was determined with seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average.

Discussion

More all-cause excess mortality occurred in Massachusetts during the first 8 weeks of the Omicron period than during the entire 23-week Delta period. Although numerically there were more excess deaths in older age groups, there was excess mortality in all adult age groups, as recorded in earlier waves, including in younger age groups.5,6 Moreover, the ratio of observed to expected all-cause deaths was similar in all age groups, and increased during the Omicron period compared with the Delta period.

Others have reported that the Omicron variant may cause milder COVID-19. If true, increased all-cause excess mortality observed during the Omicron wave in Massachusetts may reflect a higher mortality product (ie, a moderately lower infection fatality rate multiplied by far higher infection rate).

This observational study was limited by use of preliminary data, although mortality reporting for the study period in Massachusetts is more than 99% complete. Also, during the early Omicron period, a small number of deaths may have been caused by Delta infections that occurred several weeks earlier. Nevertheless, the present findings indicate that a highly contagious (although relatively milder) SARS-CoV-2 variant can quickly confer substantial excess mortality, even in a highly vaccinated and increasingly immune population.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

References

- 1.Bilinski A, Emanuel EJ. COVID-19 and excess all-cause mortality in the US and 18 comparison countries. JAMA. 2020;324(20):2100-2102. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Zimmerman EB. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes in the US, March 1, 2020, to January 2, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(17):1786-1789. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharyya RP, Hanage WP. Challenges in inferring intrinsic severity of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(7):e14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2119682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broad Institute . Broad COVID dashboard. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://covid-19-sequencing.broadinstitute.org

- 5.Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, Anderson RN, et al. Disparities in excess mortality associated with COVID-19—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(33):1114-1119. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7033a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faust JS, Krumholz HM, Du C, et al. All-cause excess mortality and COVID-19–related mortality among US adults aged 25-44 years, March-July 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(8):785-787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods