Key Points

Question

How did people’s pregnancy preferences change over the year before and the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Findings

In a cohort study of 627 participants aged 15 to 34 years in the US Southwest, the summer 2020 COVID-19 case surge was associated with a significant short-term curtailing of a pre-COVID-19 trend toward greater desire for pregnancy. Trends were most pronounced among younger nulliparous and primiparous participants.

Meaning

Given that disruptive events can increase the desire to prevent or postpone pregnancy, expanded contraceptive and abortion care models like pharmacy access will be important to reproductive autonomy during future disruptions.

This cohort study investigates longitudinal changes in pregnancy desires during the year before and the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abstract

Importance

Understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic affected people’s desire to avoid pregnancy is essential for interpreting the pandemic’s associations with access to reproductive health care and reproductive autonomy. Early research is largely cross-sectional and relies on people’s own evaluations of how their desires changed.

Objective

To investigate longitudinal changes in pregnancy desires during the year before and the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cohort study, participants reported their pregnancy preferences at baseline and quarterly for up to 18 months between March 2019 and March 2021. An interrupted time series analysis with mixed-effects segmented linear regression was used to examine population-averaged time trends. People were recruited from 7 primary and reproductive health care facilities in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Participants were sexually active, pregnancy-capable people aged 15 to 34 years who were not pregnant or sterilized. Data analysis was performed from September 2021 to January 2022.

Exposures

Continuous time, with knots at the onset of the first (July 1, 2020, summer surge) and second (November 1, 2020, fall surge) COVID-19 cases surges in the Southwest.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Preferences around potential pregnancy in the next 3 months, measured using the validated Desire to Avoid Pregnancy (DAP) scale (range, 0-4, with 4 indicating a higher desire to avoid pregnancy).

Results

The 627 participants in the analytical sample had a mean (SD) age of 24.9 (4.9) years; 320 (51.0%) identified as Latinx and 180 (28.7%) as White. Over the year before the first case surge in the US Southwest in summer 2020, population-averaged DAP scores decreased steadily over time (−0.06 point per quarter; 95% CI, −0.07 to −0.04 point per quarter; P < .001). During the summer 2020 surge, DAP scores stopped declining (0.05 point per quarter; 95% CI, −0.03 to 0.13 point per quarter; change in slope, P < .001). During the fall 2020 surge, however, DAP scores declined again at −0.11 point per quarter (95% CI, −0.26 to 0.04 point per quarter; change in slope, P = .10). Participants aged 15 to 24 years and those who were nulliparous and primiparous experienced greater declines in DAP score before the summer surge, and greater reversals of decline between summer and fall 2020, than did those who were aged 25 to 34 years and multiparous.

Conclusions and Relevance

These findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic onset was associated with the stalling of a prior trend toward greater desire for pregnancy over time, particularly for people earlier in their reproductive lives.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in widespread disruption of people’s social and economic lives, including their sexual and reproductive health. This social disturbance, economic insecurity, and strain on health systems may have compromised access to contraceptive care, fertility treatment, abortion, and autonomy over sexual behavior and may have changed people’s desires around pregnancy and childbearing.1,2,3,4,5 Interpreting the degree to which any observed changes in individuals’ reproductive health, including in pregnancy rates, birth rates and intervals, and abortion rates, are due to modified childbearing desires vs people’s compromised ability to attain their childbearing desires requires understanding how pregnancy preferences changed during the pandemic.

A growing body of cross-sectional, usually internet-based, survey research has found that reports of modified pregnancy desires were common early in the pandemic. Conducted in the US6,7,8 and other countries in the Northern Hemisphere,9,10,11,12,13 these surveys have broadly found up to one-half of respondents reporting that their desire for pregnancy declined (or that they wanted to postpone pregnancy), citing health risks, financial concerns, loss of income, and sense of uncertainty about the future. At the same time, these studies have found smaller proportions of respondents reporting increased desire for pregnancy because of the pandemic, owing to wanting change and positivity in their life, lower opportunity costs of taking time off work for child-rearing, and a recalibration of priorities.

Despite these findings, robust evidence on how the COVID-19 pandemic affected pregnancy desires at the population level remains sparse because of important methodological limitations. First, virtually all research to date has been cross-sectional and has relied on respondents’ own evaluations of how their pregnancy desires had changed because of the pandemic, rather than comparing prepandemic preferences with those measured during the pandemic. Reproductive health experts have increasingly recognized that many individuals do not hold clear pregnancy desires or intentions, especially if their life circumstances have not prompted them to form an explicit intention.14,15,16 As a result, people may not be fully aware of their preferences, know when changes happened, or attribute changes specifically to the pandemic. To date, we have lacked prospective data on pregnancy desires both before the pandemic and as the pandemic evolved over many months.

Furthermore, until recently,14 research has lacked rigorous measurement instruments to capture the full range of feelings people have about pregnancy,17,18 relying instead on simple assessments of trying or not trying, or wanting more or wanting less. Such categories do not comprehensively capture the preferences people have about a potential pregnancy, nor do they account for ambivalence or uncertainty.19,20

In this cohort study, we used longitudinal data and an interrupted time series approach to examine changes in people’s pregnancy desires over the years before (March 2019 to March 2020) and after (March 2020 to March 2021) the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We hypothesized that, on the population level, there would be an increase in preference to avoid pregnancy with the onset of the shelter-in-place mandate and during the two 2020 surges in COVID-19 cases. To our knowledge, this study is the first to use repeated measurements among the same individuals over time, over a year before and a year during the pandemic, to investigate changes in pregnancy preferences.

Methods

Study Procedures and Participants

The study protocol was approved by the University of California, San Francisco’s institutional review board. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Data were drawn from the first 2 years of the Attitudes and Decisions After Pregnancy Study, an ongoing observational cohort study examining pregnancy preferences, pregnancy decision-making, and the impact of pregnancy on people’s health and lives. Participants were recruited in the waiting rooms of 7 primary care and reproductive health facilities in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas between March 16, 2019, and February 16, 2020. To be eligible, patients had to read and speak English or Spanish and be aged 15 to 34 years, with parental consent required for minors aged 15 to 17 years if required by state law and the facility to obtain the care they were seeking. Patients had to have the capacity for pregnancy (eg, a uterus), have been sexually active with a person with sperm within 3 months, and live in a study state or bordering state. Patients were ineligible if they were sterilized, had an intrauterine device or subdermal implant placed, or were currently pregnant, unless recruited at an abortion appointment.

Eligible patients who agreed to participate completed written informed consent with a trained research assistant and received a link to an online survey to be completed within 2 weeks. Participants could opt to complete their surveys via telephone with a research assistant. Baseline surveys asked about participants’ pregnancy preferences and sociodemographic and partnership characteristics. Participants were followed for a minimum of 1 year and were asked to complete surveys every 6 weeks about new pregnancies and quarterly on a set of reproductive health indicators. A subset of participants (approximately 1 in 6) was monitored for up to 2 additional years for a separate component of the study. Participants were remunerated with a $50 gift card for completing the baseline survey, $20 for each quarterly follow-up survey, and $5 for interim pregnancy check-ins.

Measures

Our dependent variable of interest was preferences about a potential pregnancy measured with the Desire to Avoid Pregnancy (DAP) Scale.14 The DAP Scale is a validated, 14-item instrument that measures preferences about pregnancy in the next 3 months and childbearing within the next year across 3 domains: cognitive desires, affective feelings, and anticipated consequences. The DAP is unique conceptually in that it does not assume individuals hold clear intentions and allows people’s preferences to be ambivalent and underspecified. It purposefully asks about preferences within a short time frame, acknowledging that many people do not formulate long-term plans about childbearing and that preferences change with changing life circumstances. Response options for each item are a 5-point scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree); responses are averaged for a final DAP score of 0 to 4, with 4 representing a higher desire to avoid pregnancy and 0 indicating greater openness to pregnancy or, for some, desire for pregnancy.

The independent variable was continuous calendar time, from March 16, 2019, through March 15, 2021. Time coefficients are presented in quarters (eg, 3 months). We included covariables identified a priori as factors associated with pregnancy preferences, including age, participant-identified race and ethnicity, parity, partnership and cohabitation status, and experiencing food insecurity. Race and ethnicity were included to capture the sociocultural norms and life experiences (eg, racism) that can influence pregnancy preferences. Participants could choose from prespecified options and/or provide their own response. Those indicating multiple races or ethnicities were subsequently asked the race or ethnicity with which they most identified. We used food insecurity as an indicator of socioeconomic status because household income is often misreported and is often unknown among adolescents.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed from September 2021 to January 2022. Analyses included participants enrolled into the study through February 16, 2020, each contributing at least 1 observation before the onset of the COVID-19 shelter-in-place mandate and a maximum of 18 months of observation through March 15, 2021. Participants experiencing pregnancy were included in analyses until the pregnancy was reported. We described numbers of participants screened, eligible, and completing the baseline survey during the year before the onset of COVID-19. We compared age, race and ethnicity, and screening language between eligible patients who completed baseline vs those who did not using mixed-effects models that account for site clustering.

We conducted segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series data to examine population-averaged trajectories in DAP scores from March 16, 2019, to March 15, 2021.21,22 Our modeling approach was multivariable mixed-effects linear regression. Models included calendar time, modeled continuously as a linear spline with knot locations chosen as described later and with possible discontinuities (jumps) at the knots; possible interactions of the time trajectory with sociodemographic factors as described later; and random effects for participant-specific intercept and slope to allow for unique trajectories for each participant, which improved models’ fit over random intercept only models, based on log likelihood ratio tests, with significance set at P < .05. We used Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data to identify relevant COVID-19 dates to serve as hypothesized change points (eFigure in the Supplement).23 For knot locations in the linear spline, we considered (1) the onset of shelter-in-place mandates in study states (April 1, 2020); (2) 1 month into the first surge in cases in the study region following the lifting of shelter-in-place orders in summer 2020 (July 1, 2020); and (3) 1 month into the large second surge in cases in fall 2020 (November 1, 2020). We confirmed we had not missed notable change points by using data visualization, fitting models with fixed effects for month and quarter, as well as examining Harrell recommended knot locations.24

We first fit a full segmented regression model that included the 3 hypothesized change points. We examined adding discontinuities (jumps) in DAP scores at the change points; however, we excluded these parameters because we found no evidence of abrupt changes at the change points at the P < .10 level. Our final model included 2 change points, during the summer and fall surges, as no change in slope was observed at the onset of shelter-in-place. Time coefficients can be interpreted as mean change in DAP score over 3 months. We conducted complete case analyses because missing data were minimal (<3% for any variable).

To explore whether the degree of change in DAP scores differed by sociodemographic factors, we fit companion models that included interactions for factors we hypothesized post hoc might affect how people’s pregnancy preferences change in response to COVID-19. We included age group (15-24 vs 25-34 years), parity (nulliparous and primiparous vs multiparous), partnership status (main partner vs not), and food insecurity (yes vs no). We considered an interaction to be present if a joint test of time-by-factor interaction terms was significant at P < .10, indicating nonparallel trajectories. Analyses were conducted with Stata statistical software version 15 (StataCorp); results are reported at the 2-sided P < .05 significance level.

Results

Participant Characteristics

The 627 participants had a mean (SD) age of 24.9 (4.9) years at baseline (Table 1). Forty-six participants (7.3%) identified as Black, 320 (51.0%) were Latinx, 180 (28.7%) were White, and 81 (12.9%) were multiracial or identified with another race or ethnicity (eg, Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian, Middle Eastern, Native Hawaiian, North African, and Pacific Islander). Two hundred eighty-six participants (45.8%) were nulliparous, 134 (21.5%) were primiparous, and 204 (32.7%) were multiparous. Three hundred fifteen (50.3%) were living with a main romantic partner, and 231 (37.8%) had experienced food insecurity in the prior month.

Table 1. Baseline Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Participants, No. (%) (N = 627)a |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) [range], yb | 24.9 (4.9) [15-35] |

| Age group, y | |

| 15-19 | 102 (16.3) |

| 20-24 | 203 (32.4) |

| 25-29 | 193 (30.8) |

| 30-34 | 129 (20.6) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Black | 46 (7.3) |

| Latinx | 320 (51.0) |

| White | 180 (28.7) |

| Multiracial or otherc | 81 (12.9) |

| Parity (n = 624) | |

| 0, nulliparous | 286 (45.8) |

| 1, primiparous | 134 (21.5) |

| 2, multiparous | 118 (18.9) |

| ≥3, multiparous | 86 (13.8) |

| Partnership status (n = 626) | |

| Has a main partner, living together | 315 (50.3) |

| Has a main partner, not living together | 204 (32.6) |

| Has no main partner | 107 (17.1) |

| Food insecurity in last month (n = 611) | |

| Yes | 231 (37.8) |

| No | 380 (62.2) |

| Reason for clinic visit (n = 613) | |

| Contraceptive care | 257 (41.9) |

| Abortion | 95 (15.5) |

| Other reproductive health care | 203 (33.1) |

| Nonreproductive primary care | 58 (9.5) |

| Current contraceptive method | |

| None | 162 (25.8) |

| Natural or withdrawal | 69 (11.0) |

| Condom | 115 (18.3) |

| Short-acting hormonal | 241 (38.4) |

| Intrauterine device or implantd | 40 (6.4) |

Percentages may not add to 100% because of rounding.

The sample includes 4 participants determined after enrollment to be aged 35 years by their baseline survey.

Other includes Alaska Native, American Indian, Asian, Middle Eastern, Native Hawaiian, North African, Pacific Islander.

Participants had an intrauterine device or implant placed between eligibility screening and completing the baseline survey.

Enrollment

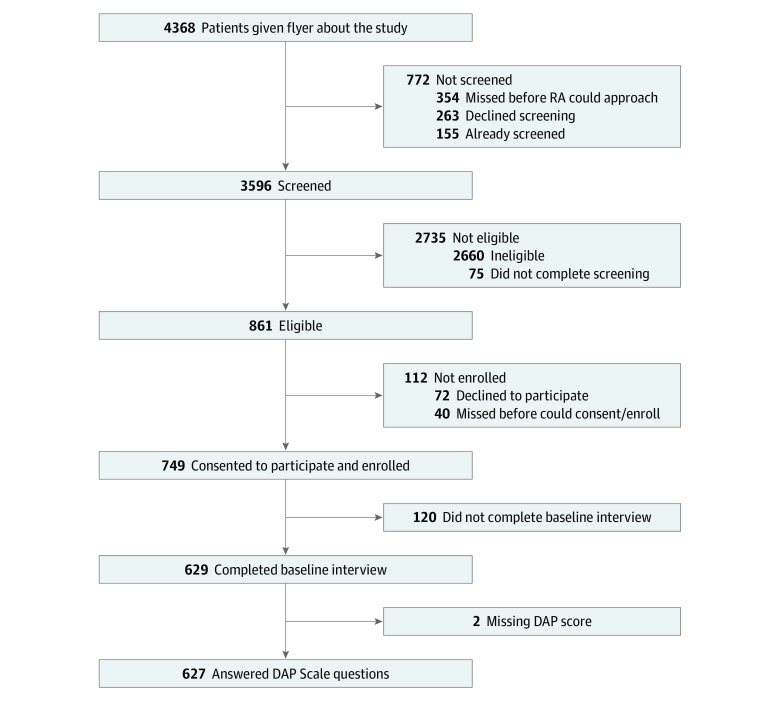

During recruitment, 4368 potential participants entered clinic waiting rooms, 3596 of whom completed eligibility screening; 861 were eligible (Figure 1). The most common reasons for ineligibility included pregnancy (1330 participants [50.5%]), age (695 participants [26.5%]), having an intrauterine device or implant (487 participants [18.6%]), no recent sexual activity (383 participants [14.9%]), and being sterilized (241 participants [9.2%]). Among eligible patients, 749 (86.6%) were enrolled. Eligible patients who completed the baseline survey did not differ from eligible patients who did not in terms of age, race and ethnicity, or language. Among the 629 participants who completed baseline, 2 did not contribute to analyses because none of their observations included a DAP score. Analyses include 2817 observations (median [IQR], 5 [5-5] observations) among 627 participants; 544 participants (86.8%) were retained at least 6 months.

Figure 1. Flowchart of Enrollment Into the Attitudes and Decisions After Pregnancy Study Before March 15, 2020.

The flowchart presents the numbers of participants screened, eligible, consenting to participate, and completing the baseline interview of the study. DAP indicates Desire to Avoid Pregnancy Scale; RA, research assistant.

DAP Scores

Baseline DAP scores covered the full 0 to 4 range of the scale, with a mean (SD) of 2.28 (1.08), demonstrating a slight skew toward greater desire to avoid pregnancy (median [IQR] score, 2.36 [1.50-3.14]). Three hundred eighty-six participants (61.6%) disagreed or strongly disagreed they wanted to have a baby within the next year, 202 (32.2%) agreed or strongly agreed it would be hard for them to manage raising a child if they had one in the next year, and 132 (21.1%) agreed or strongly agreed that thinking about pregnancy in the next 3 months made them feel excited (eTable in the Supplement).

Segmented Regression

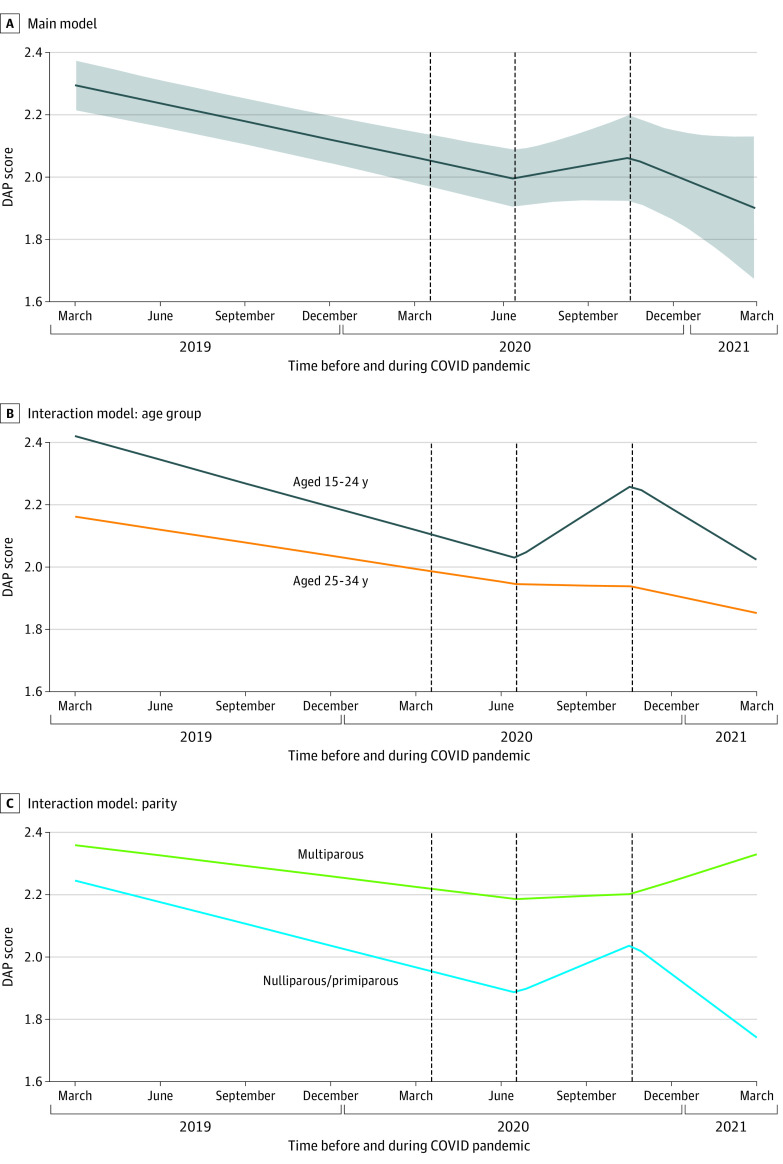

Over the year before the COVID-19 pandemic onset and the first surge of cases in summer 2020 in the US Southwest (July 1, 2020), DAP scores declined 0.06 point on the 0 to 4 DAP scale per quarter (95% CI, −0.07 to −0.04 point per quarter; P < .001) (Table 2 and Figure 2A). During the summer surge, this decline ceased, and DAP scores began to increase slightly, reflecting a significant change in slope to 0.05 point per quarter (95% CI, −0.03 to 0.13 point per quarter; change in slope, P < .001). During the fall 2020 COVID-19 surge (November 1, 2020), DAP scores resumed their pre-COVID-19 downward trajectories (−0.11 point per quarter; 95% CI, −0.26 to 0.04 point per quarter; change in slope, P = .10). There was marked individual variation in change in DAP before (slope SD, 0.12) and after (slope SD, 0.22) the summer COVID-19 surge.

Table 2. Multivariable Random Slope Mixed-Effects Model of Changes in Desire to Avoid Pregnancy Score, March 16, 2019, to March 15, 2021.

| Main model and timea | Coefficient (95% CI)b | Slopec | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope differs from 0 | Change in slope from prior slope | |||

| Before summer 2020 surge | −0.06 (−0.07 to −0.04) | −0.06 (−0.07 to −0.04) | <.001 | Not applicable |

| After summer 2020 surge | 0.11 (0.02 to 0.19) | 0.05 (−0.03 to 0.13) | .25 | <.001 |

| After fall 2020 surge | −0.16 (−0.35 to 0.03) | −0.11 (−0.26 to 0.04) | .14 | .10 |

Time is treated continuously; coefficients and slopes are reported in quarters (eg, per 3 months).

Model includes participant age, race and ethnicity, parity, partnership and cohabitation, food insecurity, and recruitment site. The Desire to Avoid Pregnancy score is on a range of 0 to 4 points, with 4 indicating greater desire to avoid pregnancy.

Slope between change points can be derived by summing coefficients.

Figure 2. Trajectory of Desire to Avoid Pregnancy (DAP) Scale Scores Before and After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Graphs show population-averaged DAP scores over the year before and year 1 of the COVID-19 pandemic. Time (in quarters) is on the x-axis; DAP score (range, 0-4, with 4 indicating higher desire to avoid pregnancy) is on the y-axis. The 3 hypothesized changes points are indicated with dashed lines (shelter-in-place [April 1, 2020], 1 month into the summer surge [July 1, 2020], and 1 month into the fall surge [November 1, 2020]). Panel A presents DAP score trajectory for the study sample, as a whole, with 95% CIs shown with shading. Panel B presents DAP score trajectories by age group from an interaction model. Panel C presents DAP score trajectories by parity from an interaction model.

The magnitude of changes in DAP scores during the study period did not differ according to partnership status or food insecurity. However, there were significant interactions with time by age group and parity. Over the 16 months before the summer 2020 surge, DAP scores declined more steeply among those aged 15 to 24 years than those aged 25 to 34 years (−0.08 point per quarter [95% CI, −0.10 to −0.05 point per quarter] vs −0.04 point per quarter [95% CI, −0.06 to −0.02 point per quarter]; P = .04) (Table 3 and Figure 2B). At the summer surge, DAP trajectories among those aged 15 to 24 years reversed and increased 0.18 point per quarter (95% CI, 0.06 to 0.28 point per quarter; change in slope, P < .001). In contrast, among those aged 25 to 34 years, the magnitude of the decline before summer 2020 attenuated to be flat (−0.01 point per quarter; 95% CI, −0.12 to 0.10 point per quarter; no significant change in slope; difference from those aged 15-24 years, P = .03).

Table 3. Age Group–by-Time and Parity-by-Time Interaction Models: Multivariable Random Slope Mixed-Effects Models of Changes in Desire to Avoid Pregnancy Score, March 16, 2019, to March 15, 2021.

| Interaction model | Coefficient (95% CI)a,b | P value for interaction | Joint P value for interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (reference, 25-34 y) | |||

| Age 15-24 y | 0.26 (0.07 to 0.44) | NA | NA |

| Time before summer 2020 surgec | −0.04 (−0.06 to −0.02) | NA | NA |

| Time after summer 2020 surgec | 0.04 (−0.08 to 0.15) | NA | NA |

| Time after fall 2020 surgec | −0.05 (−0.31 to 0.21) | NA | NA |

| Age 15-24 y by time interaction before summer 2020 surgec | −0.03 (−0.07 to −0.002) | .04 | .05 |

| Age 15-24 y by time interaction after summer 2020 surgec | 0.21 (0.04 to 0.38) | .02 | |

| Age 15-24 y by time interaction after fall 2020 surgec | −0.29 (−0.67 to 0.09) | .13 | |

| Parity (reference, multiparous) | |||

| Nulliparous-primiparous | −0.11 (−0.31 to 0.08) | NA | NA |

| Time before summer 2020 surgec | −0.03 (−0.06 to −0.004) | NA | NA |

| Time after summer 2020 surgec | 0.04 (−0.10 to 0.19) | NA | NA |

| Time after fall 2020 surgec | 0.08 (−0.25 to 0.41) | NA | NA |

| Nulliparous-primiparous by time interaction before summer 2020 surgec | −0.04 (−0.07 to −0.001) | .04 | .06 |

| Nulliparous-primiparous by time interaction after summer 2020 surgec | 0.14 (−0.04 to 0.31) | .14 | |

| Nulliparous-primiparous by time interaction after fall 2020 surgec | −0.41 (−0.81 to −0.001) | .05 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Models include participant age, race and ethnicity, parity, partnership and cohabitation, food insecurity, and recruitment site. The Desire to Avoid Pregnancy score is on a range of 0 to 4 points, with 4 indicating greater desire to avoid pregnancy.

Slope between change points can be derived by summing coefficients.

Time is treated continuously; coefficients and slopes are reported in quarters (eg, per 3 months).

Similarly, before the summer 2020 surge, DAP scores declined more steeply among nulliparous and primiparous participants than multiparous participants (−0.07 point per quarter [95% CI, −0.09 to −0.05 point per quarter] vs −0.03 point per quarter [95% CI, −0.06 to −0.004 point per quarter]; P = .04) (Table 3 and Figure 2C). DAP trajectories among nulliparous and primiparous participants reversed after the summer surge to 0.11 point per quarter (95% CI, 0.02 to 0.21 point per quarter; change in slope, P < .001), whereas they attenuated slightly among multiparous participants to 0.01 point per quarter (95% CI, −0.13 to 0.15 point per quarter; no significant change in slope).

Discussion

In this longitudinal cohort study in the US Southwest, the summer 2020 surge in COVID-19 cases was associated with a substantial attenuation in a prior time trend toward greater desire for pregnancy. The steady decline in preference to avoid pregnancy before summer 2020 was observed across sociodemographic groups. However, although the surge did not substantively alter pregnancy desires among women aged 25 to 34 years and multiparous women, it significantly changed trajectories among those aged 15 to 24 years, nulliparous, or primiparous, marking a shift toward greater desire to avoid pregnancy.

The steady decline in DAP scores before the pandemic likely reflects an age association; as reproductive-aged individuals get older, they approach a life stage at which they may want to raise a child. This reduction in desire to avoid pregnancy over time was more marked for those who would be having a first or second child than for those who would be having a third or higher order child. These differences aside, the reversing in this age trend associated with the first COVID-19 case surge bolsters early evidence suggesting that, early in the pandemic, people’s openness toward the prospect of pregnancy was reduced.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Notably, in the US Southwest, COVID-19 case rates remained low around April 2020, when the shelter-in-place mandate went into effect, and the curtailing of the DAP score decline occurred 3 months later during the first surge in COVID-19 cases in the region. This timing suggests individuals’ pregnancy preferences may have been associated more with increasing regional COVID-19 case rates than shelter-in-place mandates enacted in response to high case rates nationally.

Counter to our hypotheses, during the large fall 2020 case surge regionally and nationally, DAP scores returned to their prepandemic declining trend, rather than further increasing (although the change in slope was not significant). This trend suggests population-level changes in pregnancy preferences were short lived; as it became clear that the pandemic would be a long-standing public health emergency, individuals returned to their original trajectories. Such a trend would be consistent with fertility trends seen in reaction to other emergencies, wars, or natural disasters, during which research has found short-term declines in fertility, followed by rebounds.25,26 The age interaction we detected might reflect women’s greater flexibility in pregnancy preferences when they have more years to conceive following the emergency.

Evidence of reduced birth rates in late 2020 and early 2021 has emerged for the US and for the southwestern states, with a possible subsequent rebound.27,28 Our finding of a temporary curtailing of the pre-COVID-19 trend toward greater openness to pregnancy at the first COVID-19 surge in the Southwest is generally consistent with these rates. However, multiple factors are associated with birth rates, and not all individuals preferring to prevent or postpone childbearing were able to do so. Research has documented substantial constraints in accessing contraceptive and abortion care early in the pandemic,4,5,29,30,31,32 followed by implementation of novel approaches to expand access to care via telehealth, mail order, and pharmacies.33,34 Given that social and economic disruptive events can cause population-level increases in people’s desire to prevent or postpone pregnancy, continued implementation and evaluation of these expanded care models will be important to attain reproductive autonomy during future disruptions.

Limitations and Strengths

Because the COVID-19 pandemic was a ubiquitous exposure, we relied on 1-sample interrupted time series, rather than including a control group and examining differential changes by exposure. We, thus, could not account for other large-scale events that could have affected pregnancy preferences in 2019 to 2021. Because of our declining sample size as participants exited the study over 2020, we had limited precision to detect significant trends in later 2020 and early 2021. As a result of the association of age with parity, we lacked precision to fully disentangle each of their independent associations. In addition, this research was in 1 geographical region (US Southwest) and focused on sexually active people aged 15 to 34 years with the capacity for pregnancy who had access to health care. Results may not be generalizable beyond these groups.

The study also has substantial strengths. Because we were already following a cohort before COVID-19 and regularly measuring their pregnancy preferences, we were able to prospectively examine individual-level trends over time both before and during the pandemic. We measured changes in peoples’ pregnancy preferences with repeated measurements over time, rather than asking people to evaluate themselves how their preferences had changed. Our use of a robust instrument to measure pregnancy preferences allowed us to capture subtle changes in preferences along a continuum.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic onset was associated with a temporary stalling of a prior trend toward greater desire for pregnancy over time, particularly for people earlier in their reproductive lives. Expanded contraceptive and abortion care models, such as pharmacy access, telemedicine, and mail order, will be important to reproductive autonomy during future disruptions to medical care access.

eFigure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tracking of the Trend in Number and Seven-Day Average of Positive COVID-19 Cases in Arizona, March 15, 2020-March 15, 2021

eTable. Desire to Avoid Pregnancy (DAP) Scale Sample Item Frequencies at Baseline (N=627), Selected From 14 Items

References

- 1.Campbell AM. An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;2:100089. doi: 10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawson AK, McQueen DB, Swanson AC, Confino R, Feinberg EC, Pavone ME. Psychological distress and postponed fertility care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(2):333-341. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-02023-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts SCM, Schroeder R, Joffe C. COVID-19 and independent abortion providers: findings from a rapid-response survey. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2020;52(4):217-225. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balachandren N, Barrett G, Stephenson JM, et al. Impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on access to contraception and pregnancy intentions: a national prospective cohort study of the UK population. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2022;48(1):60-65. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2021-201164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey MJ, Bart L, Lang VW. The missing baby bust: the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for contraceptive use, pregnancy, and childbirth among low-income women. Popul Res Policy Rev. Published online March 2, 2022. doi: 10.3386/w29722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin TK, Law R, Beaman J, Foster DG. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic security and pregnancy intentions among people at risk of pregnancy. Contraception. 2021;103(6):380-385. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindberg LD, VandeVusse A, Mueller J, Kirstein M. Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from the 2020 Guttmacher survey of reproductive health experiences. June 2020. Accessed May 26, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/early-impacts-covid-19-pandemic-findings-2020-guttmacher-survey-reproductive-health

- 8.Kahn LG, Trasande L, Liu M, Mehta-Lee SS, Brubaker SG, Jacobson MH. Factors associated with changes in pregnancy intention among women who were mothers of young children in New York City following the COVID-19 outbreak. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(9):e2124273. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Micelli E, Cito G, Cocci A, et al. Desire for parenthood at the time of COVID-19 pandemic: an insight into the Italian situation. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;41(3):183-190. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1759545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coombe J, Kong F, Bittleston H, et al. Contraceptive use and pregnancy plans among women of reproductive age during the first Australian COVID-19 lockdown: findings from an online survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021;26(4):265-271. doi: 10.1080/13625187.2021.1884221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flynn AC, Kavanagh K, Smith AD, Poston L, White SL. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnancy planning behaviors. Womens Health Rep (New Rochelle). 2021;2(1):71-77. doi: 10.1089/whr.2021.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sienicka A, Pisula A, Pawlik KK, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on reproductive intentions among the Polish population. Ginekol Pol. Published online July 15, 2021. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2021.0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu C, Wu J, Liang Y, et al. Fertility intentions among couples in Shanghai under COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;151(3):399-406. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rocca CH, Ralph LJ, Wilson M, Gould H, Foster DG. Psychometric evaluation of an instrument to measure prospective pregnancy preferences: the Desire to Avoid Pregnancy Scale. Med Care. 2019;57(2):152-158. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhrolchain MN, Beaujouan E. How real are reproductive goals? uncertainty and the construction of fertility preferences. December 21, 2015. Accessed November 24, 2017. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/385269/

- 16.Bachrach CA, Morgan SP. A cognitive-social model of fertility intentions. Popul Dev Rev. 2013;39(3):459-485. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00612.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mumford SL, Sapra KJ, King RB, Louis JF, Buck Louis GM. Pregnancy intentions: a complex construct and call for new measures. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(6):1453-1462. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, et al. ; Unintended Pregnancy Working Group . The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35(2):94-101. doi: 10.1363/3509403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. “It just happens”: a qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91(2):150-156. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kendall C, Afable-Munsuz A, Speizer I, Avery A, Schmidt N, Santelli J. Understanding pregnancy in a population of inner-city women in New Orleans: results of qualitative research. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(2):297-311. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linden A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J. 2015;15(2):480-500. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1501500208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker. 2021. Accessed October 1, 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

- 24.Harrell FE Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer; 2001. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3462-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aassve A, Cavalli N, Mencarini L, Plach S, Livi Bacci M. The COVID-19 pandemic and human fertility. Science. 2020;369(6502):370-371. doi: 10.1126/science.abc9520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chandra S, Christensen J, Mamelund S-E, Paneth N. Short-term birth sequelae of the 1918–1920 influenza pandemic in the United States: state-level analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(12):2585-2595. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Martin JA. Changes in births by month: United States, January 2019-June 2021. NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release, no 19. March 2022. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr019.pdf

- 28.Morse A. US births declined during the pandemic: fewer babies born in December and January but number started to rise in March. September 21, 2021. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/09/united-states-births-declined-during-the-pandemic.html

- 29.Lewis R, Blake C, Shimonovich M, et al. Disrupted prevention: condom and contraception access and use among young adults during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic—an online survey. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2021;47(4):269-276. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2020-200975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steenland MW, Geiger CK, Chen L, et al. Declines in contraceptive visits in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception. 2021;104(6):593-599. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zapata LB, Curtis KM, Steiner RJ, et al. COVID-19 and family planning service delivery: findings from a survey of U.S. physicians. Prev Med. 2021;150:106664. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts SCM, Berglas NF, Schroeder R, Lingwall M, Grossman D, White K. Disruptions to abortion care in Louisiana during early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(8):1504-1512. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tschann M, Ly ES, Hilliard S, Lange HLH. Changes to medication abortion clinical practices in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Contraception. 2021;104(1):77-81. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiner RJ, Zapata LB, Curtis KM, et al. COVID-19 and sexual and reproductive health care: findings from primary care providers who serve adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(3):375-382. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Tracking of the Trend in Number and Seven-Day Average of Positive COVID-19 Cases in Arizona, March 15, 2020-March 15, 2021

eTable. Desire to Avoid Pregnancy (DAP) Scale Sample Item Frequencies at Baseline (N=627), Selected From 14 Items