Abstract

We constructed a model for Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1 toxin binding to midgut membrane vesicles from Heliothis virescens. Brush border membrane vesicle binding assays were performed with five Cry1 toxins that share homologies in domain II loops. Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, Cry1Ja, and Cry1Fa competed with 125I-Cry1Aa, evidence that each toxin binds to the Cry1Aa binding site in H. virescens. Cry1Ac competed with high affinity (competition constant [Kcom] = 1.1 nM) for 125I-Cry1Ab binding sites. Cry1Aa, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja also competed for 125I-Cry1Ab binding sites, though the Kcom values ranged from 179 to 304 nM. Cry1Ab competed for 125I-Cry1Ac binding sites (Kcom = 73.6 nM) with higher affinity than Cry1Aa, Cry1Fa, or Cry1Ja. Neither Cry1Ea nor Cry2Aa competed with any of the 125I-Cry1A toxins. Ligand blots prepared from membrane vesicles were probed with Cry1 toxins to expand the model of Cry1 receptors in H. virescens. Three Cry1A toxins, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja recognized 170- and 110-kDa proteins that are probably aminopeptidases. Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac, and to some extent Cry1Fa, also recognized a 130-kDa molecule. Our vesicle binding and ligand blotting results support a determinant role for domain II loops in Cry toxin specificity for H. virescens. The shared binding properties for these Cry1 toxins correlate with observed cross-resistance in H. virescens.

Bacillus thuringiensis produces parasporal crystals composed of Cry proteins during the sporulation phase of growth (1, 45). Most Cry proteins are toxic to insects, and Cry1 proteins are specifically toxic to larvae of Lepidoptera. Cry1 crystals are solubilized in the midgut of larvae, releasing 130- to 140-kDa protoxins that are subsequently processed to 55- to 60-kDa active toxins by midgut proteinases. Passing through the peritrophic membrane, Cry toxins bind to specific receptors on the brush border membrane of the midgut cells (53, 54) in a reversible manner. An irreversible binding phase, attributed to toxin insertion into the midgut membrane, takes place (29), followed by toxin oligomerization (3) and pore formation. The osmotic shock resulting from toxin-induced pores leads to cell lysis, gut paralysis, and insect death (24).

Cry toxins consist of three structural domains (23, 28) that are associated with different steps of the toxin mode of action. Domain I, composed of α-helices, is involved in pore formation (28, 46). Domain II, composed mainly of β-sheets, contains the primary determinants that specify binding to receptors on the midgut brush border (5, 10, 42, 43). Domain III (also composed of β-sheets) has been implicated in toxin stability and binding specificty in some insects (7, 11).

Since the commercial introduction of B. thuringiensis corn, cotton, and potatoes in 1996, B. thuringiensis toxins have become one of the most important tools for pest insect control. However, the development of resistance by insects challenges their future efficacy. Insects are capable of developing high levels of resistance to B. thuringiensis toxins after laboratory (20, 21, 40, 56) or field (48, 49) selection. Resistant insects are often cross resistant to B. thuringiensis toxins that were not in the environment of selection (20, 21, 50, 51), suggesting that the mechanism(s) of acquired resistance can be effective against toxins that have never been used against that insect. Although several mechanisms of resistance have been proposed (16, 41), the best-documented mechanism is the alteration of binding to the specific receptors in the midgut (15, 26, 55).

Toxins that share high homology in the loops of domain II (50) often share midgut binding sites (4, 14) and display cross-resistance. For example, Cry1Fa and Cry1A toxins have a common high-affinity binding site on brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) prepared from Plutella xylostella (22). Cry1Ac-resistant P. xylostella show greatly reduced Cry1Ac binding and cross-resistance to Cry1Fa. Though direct binding studies of Cry1Fa are not reported, it appears that when P. xylostella adapted to Cry1Ac toxin the modification that reduced Cry1Ac binding also reduced Cry1Fa toxicity. Cry1Ja, another toxin that shares high sequence homology in the loops of domain II with Cry1A toxins, presents a similar pattern of cross-resistance in P. xylostella (51).

Heliothis virescens, the subject of this study, is an important pest of cotton in the United States and the major target of transgenic cotton expressing the B. thuringiensis cry1Ac gene. H. virescens selected for Cry1Ac resistance in the laboratory is cross resistant to Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, and Cry1Fa toxins (21). In H. virescens, a model of three populations of receptor molecules for Cry1A toxins is generally accepted (17, 30, 37, 53). According to this model, receptor A (previously identified as a 170-kDa aminopeptidase N [APN]) binds Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, and Cry1Ac. Receptor B binds Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac, and receptor C only binds Cry1Ac. Alteration of receptor A is implicated as a mechanism for H. virescens resistance to Cry1A toxins (26). The 170-kDa APN elicits binding and pore formation by all three Cry1A toxins (30). Other authors (26, 39) have suggested that a 130-kDa aminopeptidase may also function as receptor A. The 170-kDa APN in H. virescens was found to be a low-affinity binding site for Cry1Ac, while the 130-kDa aminopeptidase showed high affinity (32.1 nM) for this toxin. The 170- and 130-kDa APNs may be the product of differential posttranslational glycosylation of the same protein precursor (39).

The objective of this study was to determine if toxins that share homology in the loops of domain II share binding sites on BBMV from H. virescens. Four of the toxins (Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, and Cry1Fa) are highly active against H. virescens, while Cry1Ja has low toxicity. We then used ligand blotting to determine the molecular sizes of toxin binding proteins for each Cry1 toxin. By integrating data from vesicle binding experiments, ligand blotting, and published results, we further developed the model of Cry1A toxin binding in H. virescens to include Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja toxins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insect bioassays.

The H. virescens strain used in this work was started from insects collected in Alabama by J. Graves (Louisiana State University). The colony has been maintained on an artificial diet (Southland Products, Lake Village, Ark.) in the laboratory for 23 generations.

For insect bioassays, at least five dilutions of each toxin were prepared in 20 mM Na2CO3 (pH 9.6), and 50-μl aliquots were applied uniformly over the surface of artificial diet in 2-cm2 wells (EC-International). Each toxin dilution was assayed with at least 12 neonate larvae, and the bioassay was repeated three times. Mortality was scored after 7 days. The 50% lethal concentration (LC50) values and the slopes of concentration-mortality regression lines were obtained using the Polo-PC program (44).

Bacterial strains and toxin purification.

B. thuringiensis HD-37 and HD-73 producing Cry1Aa and Cry1Ac, respectively, were obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (Columbus, Ohio). B. thuringiensis strains producing Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja were obtained from Ecogen Inc. (Langhorne, Pa.). B. thuringiensis strain MR522 producing Cry1Ea was obtained from Dow Agrosciences (San Diego, Calif.). An Escherichia coli strain carrying the B. thuringiensis NRD-12 cry1Ab toxin gene was kindly provided by Luke Masson (National Research Council of Canada, Montreal).

Toxins were prepared and purified from B. thuringiensis, as described elsewhere (31). Cry1Ab inclusions were prepared from E. coli NRD-12, and toxin was purified as previously described (34).

Fractions containing pure toxin (as determined by gel electrophoresis) were pooled, quantified by the Bradford protein assay (6) using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard, and stored at −80°C until used.

Gel electrophoresis.

Purified Cry1 toxin samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Briefly, 10 μg of toxin (for gels stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250) or 105 cpm (for 125I-Cry1A toxins) per lane was used in SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 or exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film with an intensifying screen at −80°C for 1 h.

Iodination and biotinylation of Cry1A toxins.

Labeling of purified Cry1A toxins with Na125I was done using the Chloramine T method (17). Toxin (1 μg) was labeled with 0.5 mCi of Na125I (Amersham-Pharmacia). Cry1A toxicity to insect larvae is not reduced by iodination using the Chloramine T method (53). The specific activities were 6.2 μCi/μg for Cry1Aa, 10.5 μCi/μg for Cry1Ab, and 28.4 μCi/μg for Cry1Ac (based on input toxin).

For toxin biotinylation, 0.5 mg of purified toxin was incubated (1:30 molar ratio) with EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Pierce) for 30 min at room temperature. To remove excess biotin, samples were dialyzed overnight in 20 mM Na2CO3–200 mM NaCl (pH 9.6). Biotinylated toxins were quantified as described above and stored at −80°C until used.

Midgut isolation and BBMV preparation.

Midguts were dissected from fifth instar H. virescens larvae, washed in ice-cold SET buffer (250 mM sucrose, 17 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM EGTA), and kept at −80°C until used.

BBMV were prepared by the differential magnesium precipitation method (57), as modified by Carroll and Ellar (8). The final BBMV pellet was suspended in ice-cold TBS (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 2 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl), and the protein concentration was quantified by the method of Bradford (6), as described above. BBMV were frozen in dry ice and kept at −80°C until used. After thawing, BBMV were centrifuged for 10 min at 13,500 × g and resuspended in binding buffer for binding assays (see below).

Aminopeptidase-specific activity was used as an enzymatic marker of enrichment for brush border membranes (52), using leucine-ρ-nitroanilide as the substrate. Typical activity enrichment in the BBMV preparations was five to seven times the activity measured in the initial midgut homogenates.

Binding of 125I-Cry1A to BBMV.

For qualitative binding experiments, increasing amounts of BBMV were incubated with either 0.5 nM (125I-Cry1Aa) or 0.1 nM (125I-Cry1Ab and 125I-Cry1Ac) labeled toxin in 0.1 ml (final volume) of binding buffer (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 3 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 0.1% BSA) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 13,500 × g for 10 min, and the pellets were washed twice with 0.5 ml of cold binding buffer. Nonspecific binding was determined by adding a 1,000 nM concentration of the respective unlabeled toxin to the reaction mixtures. Radioactivity was measured in a Beckman Gamma 4000 detector.

Homologous and heterologous competition experiments were done by incubating 40 μg (for Cry1Aa), 10 μg (for Cry1Ab), or 5 μg (for Cry1Ac) of BBMV with 0.5 nM (125I-Cry1Aa) or 0.1 nM (125I-Cry1Ab and 125I-Cry1Ac) labeled toxin for an hour at room temperature. Increasing amounts of unlabeled homologous or heterologous competitor were used to compete binding. Competition reactions were stopped by centrifugation at 13,500 × g for 10 min, and the pellets were washed as described before. Data were analyzed using the LIGAND program (35) to obtain a representative value of the binding affinity constant and the concentration of receptors for all toxins. The competition constant (Kcom) is used as the binding constant instead of Kd, due to the two-step binding process (reversible plus irreversible) taking place (7, 58).

Ligand blotting.

BBMV proteins (15 μg) were separated by SDS–8% PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride Q membrane filter (Millipore). The filter was blocked for 1 h in 3% BSA in TBST (25 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 3 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) and then cut into strips for the different treatments after washing. Subsequent incubations and washes were done in 0.1% BSA–TBST.

Ligand blotting with radiolabeled toxins was done by incubating the filters with 106 cpm of 125I-labeled toxin in 10 ml of 0.1% BSA–TBST for 3 h. After this, membranes were washed before exposure to film overnight at −80°C.

For biotinylated toxin ligand blots, the blocked filters were incubated with biotin-toxin (1.6 nM) for 1 h. After washing, filters were incubated with anti-biotin (Sigma) antibody (1:50,000 dilution) for an hour. Binding proteins were visualized using the ECL kit (Amersham-Pharmacia) following the manufacturer's instructions.

For the ligand blots with antibodies against the toxins, blocked filters were incubated with toxin (5 nM) for 1 h. After washing, filters were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against Cry1Ac or Cry1Fa (1:5,000 dilution) for an hour. After washing, filters were incubated with donkey anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:30,000 dilution) (Amersham-Pharmacia) for another hour. Binding proteins were visualized with an ECL kit, as described for biotinylated toxins.

RESULTS

Toxicity of Cry1 toxins to H. virescens.

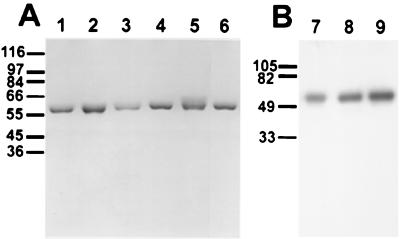

As shown in Fig. 1, each purified toxin appeared as a single band on SDS-PAGE after staining or autoradiography for 125I-labeled Cry1A toxins.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE (A) and autoradiography (B) analyses of purified and 125I-labeled Cry1 toxins. Lane 1, Cry1Aa; lane 2, Cry1Ab; lane 3, Cry1Ac; lane 4, Cry1Fa; lane 5, Cry1Ea; lane 6, Cry1Ja; lane 7, 125I-Cry1Aa; lane 8, 125I-Cry1Ab; lane 9, 125I-Cry1Ac. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left.

Table 1 shows the results of bioassays conducted with H. virescens. As previously reported, Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, and Cry1Fa, but not Cry1Ea and Cry1Ja, are highly toxic to H. virescens (18, 26, 37, 53, 54). Cry1Aa was more toxic for this study than for previous reports (53, 54). Bioassays with an independent Cry1Aa preparation (kindly provided by L. Potvin, National Research Council of Canada, Montreal) gave the same toxicity results. Peptide mapping analyses confirmed the identity and purity of our Cry1Aa preparation (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Toxicity of purified Cry1 toxins to neonate larvae of H. virescens

| Toxin | LC50 (95% fiducial limits)a | Slope ± SE |

|---|---|---|

| Cry1Aa | 5.0 (2.9–7.4) | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| Cry1Ab | 1.5 (0.8–2.3) | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| Cry1Ac | 0.5 (0.1–1.1) | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| Cry1Fa | 1.9 (1.2–2.5) | 3.2 ± 0.7 |

| Cry1Ja | 660 (464.3–921.4) | 3.2 ± 0.9 |

| Cry1Ea | >9,000 | 2.8 ± 0.6 |

| Cry1Fa-biotin | 1.9 (0.5–5.1) | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| Cry1Ja-biotin | 793 (246–5,989) | 3.2 ± 1.2 |

LC50 is expressed in nanograms of protein per square centimeter of artificial diet.

As the activities of biotinylated Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja toxins are unknown, we performed bioassays with these modified toxins. Activities of these biotinylated toxins against H. virescens were the same as those of unmodified Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja. The toxicity of Cry1Ab was previously reported to be unchanged by biotinylation (12).

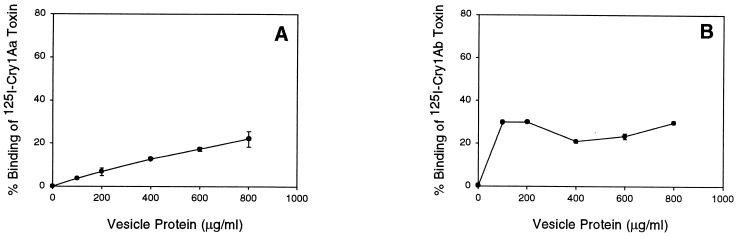

Binding of 125I-Cry1A toxins to BBMV.

Total binding experiments done with 125I-labeled toxins and various concentrations of BBMV provided the basis for selecting BBMV concentrations appropriate for subsequent competition experiments. The levels of 125I-Cry1Aa, 125I-Cry1Ab, and 125I-Cry1Ac binding shown in Fig. 2 were similar to those found in previous studies (26, 53). The amounts of BBMV needed to reach maximum binding were different for the three toxins, and they correlated directly with their in vivo activities against H. virescens. Thus, the most toxic toxin, Cry1Ac, reached maximum specific binding at 50 μg of BBMV per ml, while Cry1Aa (the least toxic of the Cry1A toxins tested) maximum binding increased, up to 1 mg/ml. These binding data identified the lowest BBMV concentration that gave maximal specific binding. According to the binding observed, 400 μg (for Cry1Aa), 100 μg (for Cry1Ab), and 50 μg (for Cry1Ac) per ml were selected as the BBMV concentrations for binding competition experiments.

FIG. 2.

Specific binding of 125I-Cry1Aa (A), 125I-Cry1Ab (B), and 125I-Cry1Ac (C) toxins to H. virescens BBMV. Vesicles at the concentrations indicated were incubated with 125I-Cry1A toxins. Binding is expressed as a percentage of input 125I-Cry1A. Binding in the presence of 1,000 nM unlabeled homologous toxin was subtracted from total binding. Maximum nonspecific binding was 20% of total binding for 125I-Cry1Aa and 40% for both 125I-Cry1Ab and 125I-Cry1Ac at the highest vesicle concentrations tested. Each data point is the average of the means based on independent trials with duplicate samples. Standard deviations of the mean values are depicted by error bars.

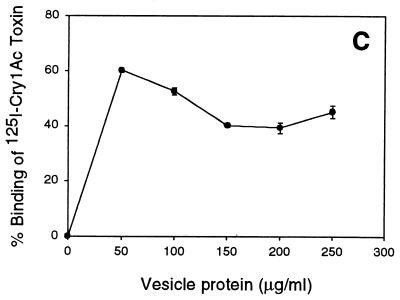

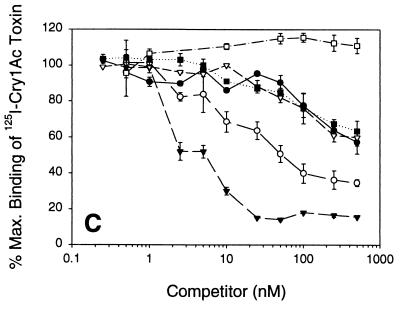

Competitive binding with 125I-Cry1A toxins.

Using unlabeled Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja as competitors, we performed heterologous binding competition experiments. For negative controls we also tested Cry2Aa and Cry1Ea toxins, and neither toxin competed with labeled Cry1A toxins (Cry2Aa data not shown).

When using 125I-Cry1Aa, high-affinity competitive binding was observed with Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, and Cry1Ac (Fig. 3). These toxins competed up to 90% of 125I-Cry1Aa binding at low concentrations. Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja both competed with 125I-Cry1Aa, although the levels of affinity were lower, as reflected in the Kcoms (Table 2). Cry1Ja and Cry1Fa competed 90% of the 125I-Cry1Aa binding, although 10 times more toxin was required to reach the 90% level of competition in the case of Cry1Fa. The fact that these unlabeled toxins competed up to 90% of the 125I-Cry1Aa binding is evidence that these toxins all recognize the single population of Cry1Aa binding sites present in the BBMV.

FIG. 3.

Binding competition between 125I-Cry1Aa (A), 125I-Cry1Ab (B), and 125I-Cry1Ac (C) and unlabeled Cry1Aa (●), Cry1Ab (○), Cry1Ac (▾), Cry1Fa (▿), Cry1Ja (■), or Cry1Ea (□). H. virescens BBMV were incubated with 125I-Cry1A toxins at a concentration of 0.5 nM (125I-Cry1Aa) or 0.1 nM (125I-Cry1Ab and 125I-Cry1Ac) plus increasing concentrations of unlabeled toxins. Binding was expressed as a percentage of the maximum amount of toxin bound during incubation with labeled toxin. Each data point is a mean based on data from independent trials. Standard deviations of the mean values are depicted by error bars.

TABLE 2.

Kcoms and concentrations of binding sites (Rts) of Cry1 toxins on BBMV from H. virescens

| Toxin |

125I-Cry1Aa

|

125I-Cry1Ab

|

125I-Cry1Ac

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcom (nM) ± SE | Rt (pmol/mg of protein) ± SE | Kcom (nM) ± SE | Rt (pmol/mg of protein) ± SE | Kcom (nM) ± SE | Rt (pmol/mg of protein) ± SE | |

| Cry1Aa | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.0 | 304.4 ± 100.0 | 69.5 ± 13.0 | 292.7 ± 100.0 | 142.0 ± 15.6 |

| Cry1Ab | 1.0 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 73.6 ± 44.0 | 16.6 ± 3.7 |

| Cry1Ac | 1.5 ± 2.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 2.3 ± 2.0 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| Cry1Fa | 12.6 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.6 | 284.5 ± 100.0 | 64.2 ± 11.4 | 233.0 ± 60.0 | 97.2 ± 10.2 |

| Cry1Ja | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 179.0 ± 100.0 | 6.5 ± 2.1 | 326.0 ± 138.0 | 150.0 ± 98.5 |

In competition experiments, only the heterologous Cry1Ac and the homologous Cry1Ab competed with high affinity for 125I-Cry1Ab binding sites. While Cry1Aa, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja reduced the amount of 125I-Cry1Ab bound, relatively higher concentrations of competitor toxins were needed, and lower total competition was observed. These results support a two-binding-site model, whereby Cry1Aa, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja have low affinity and Cry1Ac has high affinity for one Cry1Ab site. Only the homologous toxin and Cry1Ac recognize this Cry1Ab binding site.

In heterologous competition assays Cry1Aa competed with a low affinity (Kcom = 292.7 nM) for 40% of the 125I-Cry1Ac binding sites. Cry1Ab showed higher affinity (Kcom = 73.6 nM) than Cry1Aa for 125I-Cry1Ac binding sites, competing for more than 60% of the 125I-Cry1Ac binding. The Cry1Ac Kcom was 2.3 nM, and maximal competition was 90%. Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja competed with low affinity for a Cry1Ac binding site. These binding results are evidence for a population of receptors recognized exclusively by Cry1Ac, a second population recognized by Cry1Ac and Cry1Ab, and a third population recognized by Cry1Ac, Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja.

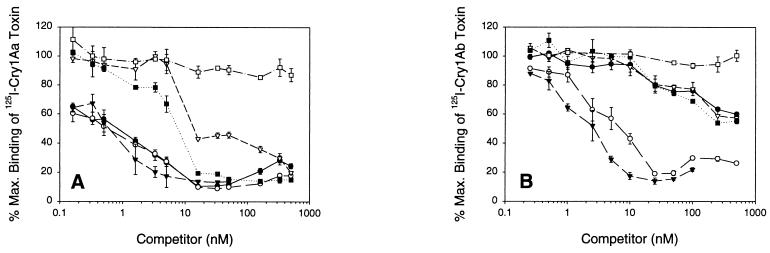

Ligand blot analyses.

Ligand blotting with BBMV was performed to relate the H. virescens Cry1 receptor model constructed from BBMV binding studies to Cry1 toxin binding proteins. Ligand blotting with 125I-labeled Cry toxins has inherent challenges due to differences in toxin labeling efficiencies and, as with Cry1Fa (31), loss of toxicity attributed to modification of critical amino acids. We employed 125I-labeled toxins, biotinylated toxins, and anti-Cry protein antibodies to ensure that toxin binding proteins visualized on blots were a consequence of toxin recognition and not the labeling technique.

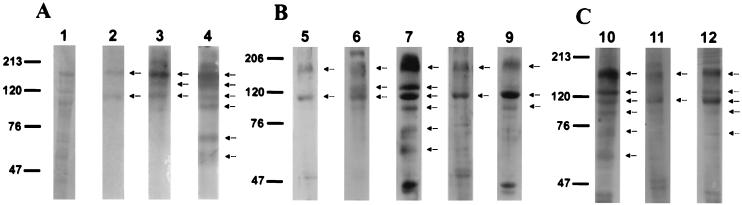

Binding molecules detected with 125I-Cry1A toxins are shown in Fig. 4 (lanes 2 to 4). Each 125I-Cry1A toxin bound to 170- and 110-kDa proteins. Apart from these common molecules, 125I-Cry1Ab and 125I-Cry1Ac also bound to a 130-kDa protein. 125I-Cry1Ac also bound to 100-kDa and smaller molecules.

FIG. 4.

Ligand blot analyses of SDS-PAGE-separated H. virescens BBMV proteins. (A) Lane 1, BBMV proteins transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride filter detected by Coomassie blue staining; lanes 2 to 4, autoradiography of blots incubated with 125I-Cry1Aa, 125I-Cry1Ab, and 125I-Cry1Ac, respectively. (B) Blots were incubated with biotinylated toxins and then antibiotin antibody-peroxidase conjugate, and detection was enhanced by chemiluminescence. Lane 5, Cry1Aa; lane 6, Cry1Ab; lane 7, Cry1Ac; lane 8, Cry1Fa; lane 9, Cry1Ja. (C) Blots were incubated with 5 nM Cry1Ac (lane 10), 5 nM Cry1Fa (lane 11), or 10 nM Cry1Fa (lane 12). The primary antibody was anti-Cry1Ac or -Cry1Fa sera, the secondary antibody was anti-rabbit peroxidase, and detection was enhanced by chemiluminescence. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left of each panel.

We used biotinylated Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja to detect binding molecules on blots (Fig. 4B). As a comparison, ligand blots with biotinylated Cry1A toxins are also shown (lanes 5, 6, and 7). Biotinylated Cry1A toxins recognized the same molecules as radiolabeled Cry1A toxins. Although both Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja bound to the 170- and 110-kDa molecules, binding to the 130-kDa protein was almost absent, unlike for Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac.

Direct detection of bound toxin on blots with antitoxin antibodies avoids the covalent modification of the toxin but requires antibodies against each toxin studied. Immunoblots with Cry1Ac and Cry1Fa revealed the same patterns of binding molecules as seen with biotinylated toxins (Fig. 4, lanes 10 to 12). In these experiments, Cry1Fa bound to the 130-kDa protein when using higher amounts of toxin (lane 12).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to construct a model for the binding sites in H. virescens recognized by five Cry1 toxins sharing high homology in domain II loops.

We determined the in vivo potencies of the selected toxins. Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, and Cry1Fa were highly toxic to H. virescens, while Cry1Ja only killed larvae at high concentrations. Cry1Aa was about 10-fold more toxic than reported by Van Rie et al. (53), but this was in agrreement with Ge et al. (18). Since the LC50 values for Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac are similar to reported values, there may be differences in Cry1Aa susceptibility between populations of H. virescens. We also tested the activity of biotinylated Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja toxins, since the toxicities of these modified toxins were unknown. Bioassay results are evidence that biotinylated Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja toxins retain their activity against H. virescens.

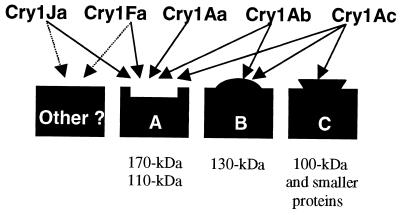

Cry1A binding to H. virescens fits a three-site model (53) (Fig. 5). As expected from this model (26, 53), Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, and Cry1Ac competed with high affinity (1 nM range) for 125I-Cry1Aa binding sites. Based on Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja competition with 125I-Cry1Aa and 125I-Cry1Ab, we conclude that those toxins recognize receptor A. Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja had high affinity (12.6 and 2.4 nM, respectively) for receptor A in 125I-Cry1Aa binding assays. The Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja Kcom values for 125I-Cry1Ab and 125I-Cry1Ac were of considerably lower affinity (179 to 326 nM), indicating that these toxins have low affinity for the receptor shared with these toxins (receptor A). The ability of the Cry1Ja toxin to bind with high affinity but not to kill is analogous to Cry1Ac binding to BBMV from Spodoptera frugiperda (17).

FIG. 5.

Model proposed for binding of B. thuringiensis Cry1 toxins to sites in the H. virescens midgut membrane. Binding proteins correlated with specific sites are listed. Dashed arrows indicate predicted, but not determined, sites.

Receptor B is a high-affinity binding site for Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac (Table 2) (53). Cry1Aa, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja do not recognize receptor B. The competition of Cry1Ab for 125I-Cry1Ac binding (Kcom = 73.6 nM) is possibly the composite of competition for receptors A and B.

Cry1Ac was the only toxin tested to recognize receptor C (Fig. 5). Van Rie et al. (53) proposed the existence of receptor C. An argument for receptor C follows. Since Cry1Ac competes all 125I-Cry1Aa (Fig. 3A) and 125ICry1Ab (Fig. 3B), but the reciprocal heterologous competition was not detected (Fig. 3C), there must exist a population of receptors unique to Cry1Ac, and this population is termed receptor C.

Our ligand blotting results were internally consistent for detection of similar-sized binding proteins by three techniques (125I-labeled Cry1A toxins, antibodies against biotinylated Cry toxins, or antibodies against Cry1Ac and Cry1Fa). Similar patterns have been previously reported for 125I-Cry1A toxins (9, 17, 30). 125I-labeled Cry1A toxins bound to 170- and 110-kDa proteins on ligand blots. Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja bound the 170- and 110-kDa proteins. The 170-kDa protein is an isoform of APN. Both the 170-kDa and the 110-kDa proteins reacted with anti-APN serum (data not shown).

Although ligand blotting data have to be interpreted with caution (27), in our model of Cry1 binding proteins (Fig. 5), binding competition experiments and ligand blot observations agree. Based on the definition of receptor A being recognized by Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, and Cry1Ac, receptor A would be comprised of 170- and 110-kDa proteins. How do we reconcile this model with the previous designation of the 170-kDa APN as a low-affinity binding site for Cry1Ac and receptor A (39)? It is not surprising that multiple molecules bind related Cry1A toxins, since this has been shown previously in Manduca sexta (47). Schwartz et al. (47) reported that multiple binding proteins were associated in a complex containing glycosylphosphatidyl inositol-anchored proteins. Also, it is possible that the high-affinity Cry1Ac binding site is a consequence of combined affinity for the 170- and 110-kDa molecules.

Modification of receptor A in a Cry1Ac-selected strain (YHD2) of H. virescens is implicated in high levels of resistance against Cry1Ac and cross-resistance to Cry1Aa and Cry1Ab (26). Apparently, the observed loss of Cry1Aa binding in strain YHD2 was due to a modification of receptor A (26). Our vesicle binding and ligand blotting results may explain the H. virescens cross-resistance to Cry1Fa (21) and Cry1Ja (F. Gould, unpublished personal communication) observed in strain YHD2: the modification of the shared receptor A also affects Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja binding and toxicity. This highlights the important role of the shared receptor A for toxicity in H. virescens, as suggested previously (26).

Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac also recognized a 130-kDa molecule. The 130-kDa molecule was recognized slightly by Cry1Aa but not by biotinylated Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja. Cry1Fa binding to the 130-kDa molecule was visualized only when high amounts of toxin (10 nM) were used, suggesting that the 130-kDa protein is a low-affinity binding molecule for Cry1Fa. The 130-kDa protein recognized by Cry1Ac and Cry1Ab on ligand blots is a candidate for receptor B.

Molecules of 100 kDa and smaller were recognized only by 125I-Cry1Ac. These molecules may constitute receptor C, although some of these proteins seem to also bind Cry1Ja and Cry1Fa. We occasionally detected a 205-kDa molecule that bound Cry1 toxins, although this observation seemed to depend on the efficacy of the transfer, due to the high molecular size of this molecule. Cry1A binding molecules of this size in ligand blots have been previously described for M. sexta (33).

The 170- and 110-kDa proteins bind Cry1A toxins and the toxins with the highest homology in domain II loops: Cry1Fa and Cry1Ja. This domain II homology suggests that binding to receptor A is specified within the loops of domain II. In agreement with this notion, highly decreased toxicity and reduced binding to the 170-kDa protein have been reported for a Cry1Ab with mutated domain II loop 2 amino acids (42). Specificity of binding to receptors B and C seems not to be related to this homology, since high homology does not relate to competition for these sites.

Our data also imply that resistance in H. virescens strain YHD2 is directed against the homologous domain II loops in these toxins. This conclusion is especially relevant when considering strategies to decrease the development of H. virescens resistance to B. thuringiensis toxins. Thus, toxins with low homology to Cry1A toxins in domain II loops are reasonable alternative toxins to Cry1A toxins in B. thuringiensis plant and biopesticide formulations. In support of this strategy, high levels of toxicity against the resistant YHD2 strain are reported for transgenic tobacco plants producing Cry2Aa2 (25). Cry2Aa2 clusters in a group distant from Cry1A toxins in a domain II loop on a sequence similarity dendrogram (51).

The availability of receptor models for Cry toxins provides a framework for exploring mechanisms of resistance and reduces the chance of selecting toxin combinations that promote cross-resistance. Our results encourage further investigations into the relationship between domain II loops and toxin binding in H. virescens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Banks, S. F. Garczynski, and F. Granero for helpful comments on the binding assays, J. Ferré for critically reading the manuscript, and L. Potvin for a gift of purified Cry1Aa toxin.

This research was supported by the NRI Competitive Grants Program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adang M J. Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins: gene structure, action, and utilization. In: Maramorosch K, editor. Biotechnology for biological control of pests and vectors. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson A I, Wu D, Zhang C. Mutagenesis of specificity and toxicity regions of a Bacillus thuringiensis protoxin gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4059–4065. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4059-4065.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson A I, Geng C, Wu L. Aggregation of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins upon binding to target insect larval midgut vesicles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2503–2507. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2503-2507.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballester V, Granero F, Tabashnik B E, Malvar T, Ferré J. Integrative model for binding of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in susceptible and resistant larvae of the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1413–1419. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1413-1419.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballester V, Granero F, de Maagd R A, Bosch D, Mensua J L, Ferré J. Role of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin domains in toxicity and receptor binding in the diamondback moth. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1900–1903. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1900-1903.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton S L, Ellar D J, Li J, Derbyshire D J. N-acetylgalactosamine on the putative insect receptor aminopeptidase N is recognised by a site on the domain III lectin-like fold of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:1011–1022. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll J, Ellar D J. An analysis of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin action on insect-midgut-membrane permeability using a light-scattering assay. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:771–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowles E A, Yunovitz H, Charles J F, Gill S S. Comparison of toxin overlay and solid-phase binding assays to identify diverse Cry1A(c) toxin-binding proteins in Heliothis virescens midgut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2738-2744.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean D H, Rajamohan F, Lee M K, Wu S-J, Chen X J, Alcantara E, Hussain S R. Probing the mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal proteins by site-directed mutagenesis—a minireview. Gene. 1996;179:111–117. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Maagd R A, Kwa M S G, van der Klei H, Yamamoto T, Schipper B, Vlak J M, Stiekema W J, Bosch D. Domain III substitutions in Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1A(b) results in superior toxicity for Spodoptera exigua and altered membrane protein recognition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1537–1543. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1537-1543.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denolf P, Jansens S, Van Houdt S, Peferoen M, Degheele D, Van Rie J. Biotinylation of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1821–1827. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.6.1821-1827.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du C, Nickerson K W. The Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin binds biotin-containing proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2932–2939. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2932-2939.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escriche B, Ferré J, Silva F J. Occurrence of a common binding site in Mamestra brassicae, Phthorimaea operculella, and Spodoptera exigua for the insecticidal crystal proteins CryIA from Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;27:651–656. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferré J, Real M D, Van Rie J, Jansens S, Peferoen M. Resistance to the Bacillus thuringiensis bioinsecticide in a field population of Plutella xylostella is due to a change in a midgut membrane receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5119–5123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forcada C, Alcacer E, Garcerá M D, Martínez R. Differences in the midgut proteolytic activity of two Heliothis virescens strains, one susceptible and one resistant to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 1996;31:257–272. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garczynski S F, Crim J W, Adang M J. Identification of putative insect brush border membrane-binding molecules specific to Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin by protein blot analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:2816–2820. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.10.2816-2820.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge A Z, Rivers D, Milne R, Dean D H. Functional domains of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal crystal proteins. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17954–17958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gill S S, Cowles E A, Francis V. Identification, isolation and cloning of a Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin-binding protein from the midgut of the lepidopteran insect Heliothis virescens. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27277–27282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gould F, Martínez-Ramírez A, Anderson A, Ferré J, Silva F J, Moar W J. Broad-spectrum resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in Heliothis virescens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7986–7990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gould F, Anderson A, Reynolds A, Bumgarner L, Moar W J. Selection and genetic analysis of a Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) strain with high levels of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. J Econ Entomol. 1995;88:1545–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granero F, Ballester V, Ferré J. Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins Cry1Ab and Cry1Fa share a high affinity binding site in Plutella xylostella (L.) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;224:779–783. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grochulski P, Masson L, Borisova S, Pusztai-Carey M, Schwartz J L, Brousseau R, Cygler M. Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA(a) insecticidal toxin: crystal structure and channel formation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knowles B H. Mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal δ-endotoxins. Adv Insect Physiol. 1994;24:275–308. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kota M, Daniell H, Varma S, Garczynski S F, Gould F, Moar W J. Overexpression of the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) Cry2Aa2 protein in chloroplasts confers resistance to plants against susceptible and Bt-resistant insects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1840–1845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee M K, Rajamohan F, Gould F, Dean D H. Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA δ-endotoxins in a laboratory-selected Heliothis virescens strain is related to receptor alteration. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3836–3842. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3836-3842.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee M K, Dean D H. Inconsistencies in determining Bacillus thuringiensis toxin binding sites relationship by comparing competition assays with ligand blotting. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:575–580. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li J, Carroll J, Ellar D J. Crystal structure of insecticidal δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5 Å resolution. Nature. 1991;353:815–821. doi: 10.1038/353815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang Y, Patel S S, Dean D H. Irreversible binding kinetics of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA δ-endotoxins to gypsy moth brush border membrane vesicles is directly correlated to toxicity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24719–24724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo K, Sangadala S, Masson L, Mazza A, Brousseau R, Adang M J. The Heliothis virescens 170-kDa aminopeptidase functions as “receptor A” by mediating specific Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A δ-endotoxin binding and pore formation. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;27:735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(97)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo K, Banks D, Adang M J. Toxicity, binding, and permeability analyses of four Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1 δ-endotoxins by use of brush border membrane vesicles of Spodoptera exigua and Spodoptera frugiperda. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:457–464. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.457-464.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luttrell R G, Wan L, Knighten K. Variation in susceptibility of noctuid (Lepidoptera) larvae attacking cotton and soybean to purified endotoxin proteins and commercial formulations of Bacillus thuringiensis. J Econ Entomol. 1999;92:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez-Ramírez A C, Gonzalez-Nebauer S, Escriche B, Real M D. Ligand blot identification of a Manduca sexta midgut binding protein specific to three Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A-type ICPs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;201:782–787. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masson L, Prefontaine G, Peloquin L, Lau P C K, Brousseau R. Comparative analysis of the individual protection components in P1 crystals of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki isolates NRD-12 and HD-1. Biochem J. 1989;269:507–512. doi: 10.1042/bj2690507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munson P J, Rodbard D. LIGAND: a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naim H Y, Joberty G, Alfalah M, Jacob R. Temporal association of the N- and O-linked glycosylation events and their implication in the polarized sorting of intestinal brush border sucrase-isomaltase, aminopeptidase N, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17961–17967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oddou P, Hartmann H, Geiser M. Identification and characterization of Heliothis virescens midgut membrane proteins binding Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:673–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oddou P, Hartmann H, Radecke F, Geiser M. Immunologically unrelated Heliothis sp. and Spodoptera sp. midgut membrane-proteins bind Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA(b) δ-endotoxin. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:145–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oltean D I, Pullikuth A K, Lee H K, Gill S S. Partial purification and characterization of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxin receptor A from Heliothis virescens and cloning of the corresponding cDNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4760–4766. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4760-4766.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oppert B, Kramer K J, Johnson D E, MacIntosh S C, McGaughey W H. Altered protoxin activation by midgut enzymes from a Bacillus thuringiensis resistant strain of Plodia interpunctella. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198:940–947. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oppert B, Kramer K J, Beeman R W, Johnson D, McGaughey W H. Proteinase-mediated insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23473–23476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajamohan F, Cotrill J A, Gould F, Dean D H. Role of domain II, loop 2 residues of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIAb δ-endotoxin in reversible and irreversible binding to Manduca sexta and Heliothis virescens. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2390–2396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajamohan F, Hussain S-R A, Cotrill J A, Gould F, Dean D H. Mutations in domain II, loop 3 of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIAa and CryIAb δ-endotoxins suggest loop 3 is involved in initial binding to lepidopteran midguts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25220–25226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Russell R M, Robertson J L, Savin N E. POLO: a new computer program for probit analysis. Bull Entomol Soc Am. 1977;23:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Van Rie J, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Zeigler D R, Dean D H. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz J-L, Juteau M, Grochulski P, Cygler M, Prefontaine G, Brousseau R, Masson L. Restriction of intramolecular movements within the Cry1Aa toxin molecule of Bacillus thuringiensis through disulfide bond engineering. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:397–402. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwartz J-L, Lu Y J, Soehnlein P, Brousseau R, Masson L, Laprade R, Adang M J. Ion channels formed in planar lipid bilayers by Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in the presence of Manduca sexta midgut receptors. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:270–276. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shelton A M, Robertson J L, Tang J D, Perez C, Eigenbrode S D, Preisler H K, Wilsey W T, Cooley R J. Resistance of diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) to Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies in the field. J Econ Entomol. 1993;86:697–705. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabashnik B E, Cushing N L, Finson N, Johnson M W. Field development of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) J Econ Entomol. 1990;83:1671–1676. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tabashnik B E, Finson N, Johnson M W, Heckel D G. Cross-resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin CryIF in the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4627–4629. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4627-4629.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tabashnik B E, Malvar T, Liu Y B, Finson N, Borthakur D, Shin B S, Park S H, Masson L, de Maagd R A, Bosch D. Cross-resistance of the diamondback moth indicates altered interactions with domain II of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2839–2844. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2839-2844.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Terra W R, Ferreira C. Insect digestive enzymes: properties, compartmentalization and function. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1994;109B:1–62. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Rie J, Jansens S, Hofte H, Degheele D, Van Mellaert H. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins: importance of specific receptors on the brush border membrane of the mid-gut of target insects. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:239–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Rie J, Jansens S, Hofte H, Degheele D, Van Mellaert H. Receptors on the brush border membrane of the insect midgut as determinants of the specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1378–1385. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1378-1385.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Rie J, McGaughey W H, Johnson D E, Barnett B D, Van Mellaert H. Mechanism of insect resistance to the microbial insecticide Bacillus thuringiensis. Science. 1990;24:72–74. doi: 10.1126/science.2294593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whalon M E, Miller D L, Hollingworth R M, Grafius E J, Miller J R. Selection of a colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) strain resistant to Bacillus thuringiensis. J Econ Entomol. 1993;86:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolfersberger M, Luethy P, Maurer A, Parenti P, Sacchi F V, Giordana B, Hanozet G M. Preparation and partial characterization of amino acid transporting brush border membrane vesicles from the larval midgut of the cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae) Comp Biochem Physiol. 1987;86A:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu S J, Dean D H. Functional significance of loops in the receptor binding domain of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIIIA δ-endotoxin. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:628–640. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]