Key Points

Question

What is the overall frequency of use and cost of low-value services delivered to veterans enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration (VA) by VA facilities and VA Community Care (VACC) programs?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 5.2 million enrolled veterans, 19.6 low-value services per 100 veterans were delivered by VA facilities or VACC programs in fiscal year 2018, involving 13.6% of veterans at a cost of $205.8 million.

Meaning

These findings suggest that low-value service use is common and costly among veterans enrolled in the VA, representing opportunities to reduce unnecessary health services delivered by VA facilities and VACC programs.

This cross-sectional study compiles use and cost data of low-value health services delivered or paid for by the Veterans Health Administration (VA).

Abstract

Importance

Within the Veterans Health Administration (VA), the use and cost of low-value services delivered by VA facilities or increasingly by VA Community Care (VACC) programs have not been comprehensively quantified.

Objective

To quantify veterans’ overall use and cost of low-value services, including VA-delivered care and VA-purchased community care.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study assessed a national population of VA-enrolled veterans. Data on enrollment, sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health care services delivered by VA facilities or paid for by the VA through VACC programs were compiled for fiscal year 2018 from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse. Data analysis was conducted from April 2020 to January 2022.

Main Outcomes and Measures

VA administrative data were applied using an established low-value service metric to quantify the use of 29 potentially low-value tests and procedures delivered in VA facilities and by VACC programs across 6 domains: cancer screening, diagnostic and preventive testing, preoperative testing, imaging, cardiovascular testing and procedures, and other procedures. Sensitive and specific criteria were used to determine the low-value service counts per 100 veterans overall, by domain, and by individual service; count and percentage of each low-value service delivered by each setting; and estimated cost of each service.

Results

Among 5.2 million enrolled veterans, the mean (SD) age was 62.5 (16.0) years, 91.7% were male, 68.0% were non-Hispanic White, and 32.3% received any service through VACC. By specific criteria, 19.6 low-value services per 100 veterans were delivered in VA facilities or by VACC programs, involving 13.6% of veterans at a total cost of $205.8 million. Overall, the most frequently delivered low-value service was prostate-specific antigen testing for men aged 75 years or older (5.9 per 100 veterans); this was also the service with the greatest proportion delivered by VA facilities (98.9%). The costliest low-value services were spinal injections for low back pain ($43.9 million; 21.4% of low-value care spending) and percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary disease ($36.8 million; 17.9% of spending).

Conclusions and Relevance

This cross-sectional study found that among veterans enrolled in the VA, more than 1 in 10 have received a low-value service from VA facilities or VACC programs, with approximately $200 million in associated costs. Such information on the use and costs of low-value services are essential to guide the VA’s efforts to reduce delivery and spending on such care.

Introduction

Low-value care, defined as the use of a health service whose harms or costs outweigh its benefits, is a major driver of wasteful health care spending and exerts negative physical, psychological, and financial harms upon patients.1,2,3 Estimates suggest that low-value services are common and costly, affecting as many as 43% of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare and private insurance plans.1,4,5,6

Studies on the use of individual health services have suggested that low-value care may also be prevalent within the Veterans Health Administration (VA), the largest integrated health care system in the US.3,7,8,9,10 This suggested prevalence in the VA is notable because VA clinicians are government employees and largely protected from malpractice concerns that may drive overuse. Furthermore, VA facilities have little financial incentive to deliver unnecessary tests and procedures. However, no published studies have applied a comprehensive metric to quantify low-value service use within the VA, and the VA does not routinely monitor low-value services delivered by its facilities in concert with its other extensive health care quality monitoring programs.10

As a result of the recently legislated Veterans Choice Program and MISSION Act, up to one-third (ie, 2.6 million) of VA-enrolled veterans have also been referred to non-VA providers to receive care paid for by the VA but not readily available from primary VA facilities because of either long appointment wait times or distance and driving time barriers.11,12 When these barriers are encountered, veterans are referred to VA Community Care (VACC) programs to receive the specific type of care they are seeking, with the 3 most common referrals being physical therapy, ophthalmology, and orthopedic care.11 However, the overall use and cost of low-value services delivered by VACC programs are not well characterized. Non–VA facilities largely operate within a fee-for-service system and lack the robust decision support tools and ordering restrictions embedded in the VA’s unified electronic medical record, potentially leading to an increased use of low-value services.12,13 As the primary payer for VACC programs, the VA currently bears the cost without mechanisms to ensure that clinicians minimize their use of such low-value services.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to quantify veterans’ overall use and the cost of low-value services, including VA-delivered care and VA-purchased community care.

Methods

Study Design, Data Sources, and Cohorts

This retrospective cross-sectional study used VA administrative data and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.14 Because the study used deidentified data, it was deemed exempt by the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

From the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), we compiled enrollment data, sociodemographic characteristics, medical comorbidity data, and health services delivered by VA facilities, which include both VA medical centers and their affiliated community-based outpatient clinics.15 To capture the use of health services delivered in VACC programs, we used institutional and professional service claims within the VA Program Integrity Tool and fee-basis files, both of which were also contained within the CDW.16 We also compiled diagnosis codes and other health service claims from the Medicare Outpatient, Inpatient, Skilled Nursing Home Stay, Home Health, Hospice, and Carrier files for a sensitivity analysis that incorporated Medicare Data.

We used data from fiscal year 2018 (FY18) to determine veterans’ low-value service use and cost, data from FY17 to identify sociodemographic characteristics, and data from FY15-18 to identify historical diagnoses, procedure codes, and any other data elements used to determine a veteran’s eligibility to receive 1 or more low-value health services.

The overall cohort comprised all veterans continuously enrolled in the VA during FY17-18 with 1 or more inpatient or outpatient encounter in FY18 to ensure engagement in VA care (eFigure in the Supplement). We also compiled service-specific cohorts of veterans eligible to receive each low-value service on the basis of their medical history (eg, veterans with a history of low back pain were eligible to receive a related low-value imaging study).

Identifying Low-Value Service Use

We applied a metric originally developed for Medicare data to identify 29 potentially low-value tests and procedures across 6 domains: cancer screening, diagnostic and preventive testing, preoperative testing, imaging, cardiovascular testing and procedures, and other procedures (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement).4,17 This metric has previously been applied within the VA to identify low-value prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening and imaging tests.7,18

As previously used in Medicare and by the VA,4,7,10 we applied 2 versions of each low-value health service metric: one with higher sensitivity (and lower specificity), which served as a base measure, and one with higher specificity (and lower sensitivity). For example, PSA screening for prostate cancer is typically of low value in men aged 75 years or older because it results in overdiagnosis of prostate cancer. Therefore, men aged 75 years or older who underwent PSA screening would be captured when applying the sensitive criteria for low-value PSA testing. However, PSA testing may be appropriate for surveillance in men with a history of prostate cancer; thus, these men would be excluded from the specific criteria. Through this approach, we identified a range of potential low-value service use for each test or procedure that accounts for variations in related guidelines and acknowledges the inherent subjectivity of labeling a service as low-value on the basis of administrative data.4

Many veterans enrolled in the VA are also enrolled in Medicare. For these veterans, some of the diagnosis and procedure codes relevant to classifying a service as potentially low value may only be present in Medicare claims.19 Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we incorporated VA and Medicare data to evaluate how the use of both of these data sources influences whether health services delivered by VA facilities are characterized as low value.

Calculating Cost

We applied standardized cost estimates for each low-value service generated by the VA Health Economics Resource Center.20 These estimates represent the hypothetical reimbursement for performing a test or procedure based on average national Medicare and private sector reimbursement rates. For each low-value service, we applied the cost directly attributable to the Current Procedural Terminology code recorded for the service and the costs attributable to any facility fees or other necessary ancillary tasks, such as venipuncture for a low-value blood test or sedation for a low-value procedure (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Veteran Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

At the veteran level, we generated sociodemographic variables for age, sex, and race and ethnicity (ie, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, or other [including American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Pacific Islander, and multiracial]) based on categories available within the VA CDW. We used the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index to capture veterans’ comorbid medical conditions.21 We also determined VA priority status, which dictates the generosity of a veteran’s VA benefits.22

We characterized variables that may enable the availability of health services delivered by VA facilities and VACC programs. Specifically, we used the VA Planning System and Support Group database to determine census region (ie, Northeast, Midwest, South, West) and driving time and distance to the VA facility where each veteran received the plurality of their care. From the Area Health Resource File, we used the urban influence code to identify the rurality of each veteran’s place of residence.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were completed from April 2020 to January 2022. We calculated the means and SDs for all continuous sociodemographic variables and frequencies for all categorical variables. In the overall cohort, we applied both the specific and sensitive criteria to determine the percentage of veterans who received at least 1 low-value service and the service counts per 100 veterans in total, by domain (eg, cancer screening), and for each unique service delivered in FY18. In addition, we determined the count and percentage of each low-value service delivered by VA facilities and through VACC programs, the overall cost and percentage of overall low-value service costs for each low-value service, and the service counts per 100 veterans in each service-specific cohort. In the sensitivity analysis, we determined the absolute change in count of each low-value health service, applying the specific criteria using VA data alone vs VA and Medicare data.

Results

There were 5 242 301 VA-enrolled veterans in the overall cohort (eFigure in the Supplement). The mean (SD) age was 62.5 (16.0) years. A total of 4 807 110 (91.7%) of veterans were men, and 435 191 (8.3%) women; 330 819 (6.3%) were Hispanic, 904 818 (17.3%) were non-Hispanic Black, 3 565 789 (68.0%) were non-Hispanic White, and 161 535 (3.1%) were of other race and ethnicity (American Indian or Alaska Native, 34 677 [0.66%]; Asian, 49 112 [0.94%]; Pacific Islander, 37 801 [0.72%]; multiracial, 39 945 [0.76%]). Race and ethnicity data were missing for 279 340 (5.3%) of veterans (Table 1). Overall, 1.7 million (32.3%) veterans received any type of health service through VACC programs in FY18.

Table 1. Patient Characteristicsa.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 62.5 (16.0) |

| 18-39 | 635 195 (12.1) |

| 40-64 | 1 802 767 (34.4) |

| 65-84 | 2 424 299 (46.2) |

| ≥85 | 380 040 (7.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 4 807 110 (91.7) |

| Female | 435 191 (8.3) |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 330 819 (6.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 904 818 (17.3) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 3 565 789 (68.0) |

| Other | 161 535 (3.1) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 34 677 (0.66) |

| Asian | 49 112 (0.94) |

| Pacific Islander | 37 801 (0.72) |

| Multiracial | 39 945 (0.76) |

| Missing | 279 340 (5.3) |

| VA priority groupb,c | |

| 1-4 | 2 977 241 (56.8) |

| 5 | 1 082 383 (20.6) |

| 6-8 | 1 180 780 (22.5) |

| Census regionc | |

| Northeast | 672 018 (12.8) |

| Midwest | 1 145 993 (21.9) |

| South (+ Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands) | 2 334 174 (44.5) |

| West (+ Guam) | 1 082 545 (20.7) |

| Urban/rural living environmentd | |

| Large metropolitan | 2 211 390 (42.2) |

| Small metropolitan | 1 957 027 (37.3) |

| Micropolitan | 610 330 (11.6) |

| Noncore rural | 452 111 (8.6) |

| Driving distance to the nearest VA facility, mean (SD),c miles | 15.3 (15.1) |

| Driving time to the nearest VA facility, mean (SD),c min | 20.6 (16.1) |

| No. of Elixhauser conditions, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.7) |

Abbreviation: VA, Veterans Health Administration.

N = 5 242 301.

Veterans are assigned to 1 of 8 priority groups upon VA enrollment based on service-connected illnesses, era of service, and socioeconomic status as determined by means testing. The priority group determines the veteran’s level of copays. We categorized priority status into 3 groups associated with generosity of VA health benefits: service-connected disability present, low income, and no service-connected disability/low income.

Missing values: VA priority group, 1897 (<0.1%); census region, 7571 (0.1%); urban vs rural living environment, 11 443 (0.2%); driving time and distance, 10 311 (0.2%).

Derived from the Urban Influence Codes classification scheme.

Use and Cost of Low-Value Services

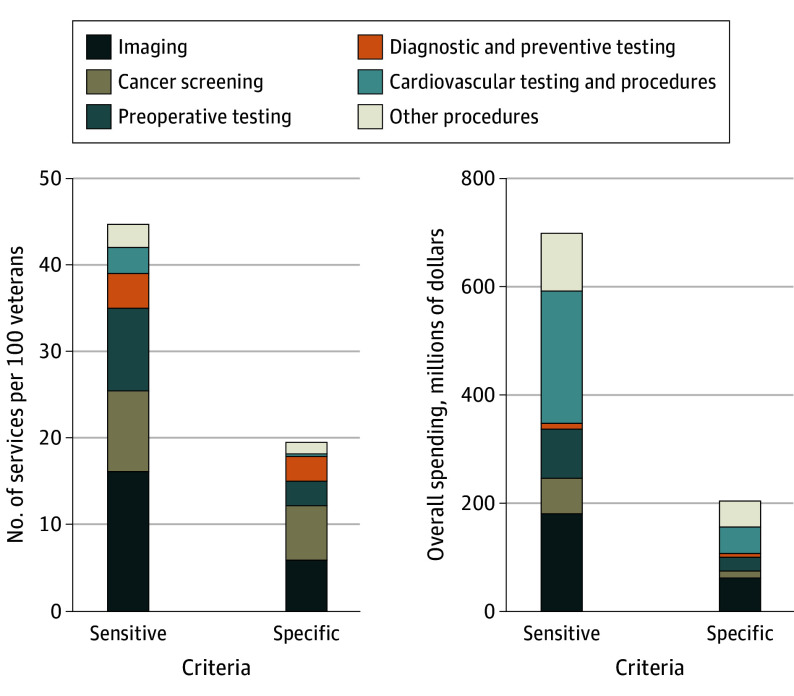

For brevity, the rates of low-value services and associated spending are presented as the specific version of the measures, followed in parentheses by the corresponding value for the sensitive version. Overall, 19.6 (44.8) low-value services per 100 veterans were delivered, with 13.6% (22.1%) of veterans receiving at least 1 such service. The total cost of low-value services in FY18 was $205.8 million ($698.9 million) (Figure). By domain, veterans most frequently received cancer screening at 6.2 (9.3) per 100 veterans, and total spending was greatest for imaging at $64.7 million ($183.6 million). Cardiovascular testing and procedures at $49 million ($243.7 million) and other surgery at $46.9 million ($105.3 million) comprised a greater share of overall spending relative to their use because of the higher unit costs of such procedures and their associated facility fees.

Figure. Overall Use and Cost of Low-Value Services Delivered to Veterans Health Administration–Enrolled Veterans in Fiscal Year 2018, Applying Both Sensitive and Specific Criteria.

Number of services per domain: imaging, 8; preoperative testing, 4; cardiovascular testing and procedures, 5; cancer screening, 4; diagnostic and preventive testing, 6; and other surgery, 2.

As shown in Table 2 (specific criteria) and eTable 3 in the Supplement (sensitive criteria), the most frequently delivered individual low-value services were PSA testing for men aged 75 years or older (5.9 [7.8] per 100 veterans), followed by back imaging for patients with nonspecific low back pain (2.7 [10.6] per 100 veterans) and preoperative chest radiography (2.3 [7.2] per 100 veterans). The low-value services with the greatest proportion delivered by VA facilities (Table 2) included PSA testing for men aged 75 years or older (306 317 [98.9%]), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D testing in the absence of hypercalcemia or decreased kidney function (26 451 [98.5%]), and cervical cancer screening for women aged 65 years or older (4496 [97.8%]).

Table 2. Overall Use of Low-Value Services Delivered by Veterans Health Administration (VA) Facilities and in VA Community Care (VACC) Programs in Fiscal Year 2018a.

| Low-value health services by domain | Overall use (VA + VACC settings),b No. | By setting, No. (row %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Per 100 veteransc | VA facilities | VACC programs | |

| Cancer screening | ||||

| PSA testing for men aged ≥75 y | 309 731 | 5.9 | 306 317 (98.9) | 3414 (1.1) |

| Colorectal cancer screening for adults aged ≥75 y | 7220 | 0.1 | 6050 (83.8) | 1170 (16.2) |

| Cervical cancer screening for women aged ≥65 y | 4599 | 0.1 | 4496 (97.8) | 103 (2.2) |

| Cancer screening for patients with CKD receiving dialysis | 2082 | 0.04 | 1909 (91.7) | 173 (8.3) |

| Total | 323 632 | 6.2 | 318 772 (98.5) | 4860 (1.5) |

| Imaging | ||||

| Back imaging for patients with nonspecific low back pain | 141 424 | 2.7 | 122 801 (86.8) | 18 623 (13.2) |

| Screening for carotid artery disease in asymptomatic adults | 90 080 | 1.7 | 81 127 (90.1) | 8953 (9.9) |

| Head imaging for uncomplicated headache | 51 333 | 1.0 | 42 340 (82.5) | 8993 (17.5) |

| Head imaging for syncope | 15 606 | 0.3 | 12 255 (78.5) | 3351 (21.5) |

| CT of the sinuses for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis | 8908 | 0.2 | 7418 (83.3) | 1490 (16.7) |

| Screening for carotid artery disease for syncope | 7007 | 0.1 | 5114 (73.0) | 1893 (27.0) |

| Imaging for diagnosis of plantar fasciitis | 4745 | 0.1 | 3480 (73.3) | 1265 (26.7) |

| EEG for headaches | 1984 | 0.04 | 1266 (63.8) | 718 (36.2) |

| Total | 321 087 | 6.1 | 275 801 (85.9) | 45 286 (14.1) |

| Preoperative testing | ||||

| Chest radiography | 117 777 | 2.3 | 105 054 (89.2) | 12 723 (10.8) |

| Echocardiography | 14 355 | 0.3 | 12 662 (88.2) | 1693 (11.8) |

| Stress test | 12 830 | 0.2 | 9508 (74.1) | 3322 (25.9) |

| Pulmonary function test | 7044 | 0.1 | 6119 (86.9) | 925 (13.1) |

| Total | 152 006 | 2.9 | 133 343 (87.7) | 18 663 (12.3) |

| Diagnosis and preventive testing | ||||

| PTH measurement for patients with stage 1-3 CKD | 83 664 | 1.6 | 80 459 (96.2) | 3205 (3.8) |

| 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D testing in the absence of hypercalcemia or decreased kidney function | 26 849 | 0.5 | 26 451 (98.5) | 398 (1.5) |

| Total or free T3 level testing for patients with hypothyroidism | 24 205 | 0.5 | 22 263 (92.0) | 1942 (8.0) |

| Homocysteine testing for cardiovascular disease | 4878 | 0.1 | 4411 (90.4) | 467 (9.6) |

| BMD testing at frequent intervals | 3460 | 0.1 | 3357 (97.0) | 103 (3.0) |

| Hypercoagulability testing for patients with deep vein thrombosis | 3117 | 0.1 | 2503 (80.3) | 614 (19.7) |

| Total | 146 173 | 2.8 | 139 444 (95.4) | 6729 (4.6) |

| Other procedures | ||||

| Spinal injection for low back pain | 72 659 | 1.4 | 44 435 (61.2) | 28 224 (38.8) |

| Arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis | 998 | 0.02 | 616 (61.7) | 382 (38.3) |

| Total | 73 657 | 1.4 | 45 051 (61.2) | 28 606 (38.8) |

| Cardiovascular testing and procedures | ||||

| Stress testing for stable coronary disease | 6914 | 0.1 | 5018 (72.6) | 1896 (27.4) |

| PCI with balloon angioplasty or stent placement for stable coronary disease | 3471 | 0.1 | 1450 (41.8) | 2021 (58.2) |

| IVC filters to prevent pulmonary embolism | 1423 | 0.03 | 643 (45.2) | 780 (54.8) |

| Renal artery angioplasty or stenting | 182 | 0.003 | NA | NA |

| Carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients | 37 | 0.001 | NA | NA |

| Total | 12 027 | 0.2 | 7219 (60.0) | 4808 (40.0) |

| Grand total | 1 028 582 | 19.6 | 919 630 (89.4) | 108 952 (10.6) |

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalogram; IVC, inferior vena cava; NA, not available; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PTH, parathyroid hormone; T3, triiodothyronine.

Data are masked to avoid presenting small cell sizes in accordance with our data use agreement with Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services guidelines.

Counts represent low-value health services identified by applying specific criteria.

Denominator is 5 242 301 for the full cohort.

With application of the specific criteria, the most frequently delivered services in VACC programs were spinal injection for low back pain (28 224 [38.8%]), back imaging for patients with nonspecific low back pain (18 623 [13.2%]), and preoperative chest radiography (12 723 [10.8%]). The low-value services with the greatest proportion delivered through VACC programs included percutaneous coronary intervention with balloon angioplasty or stent placement for stable coronary disease (2021 [58.2%]) and inferior vena cava filters to prevent pulmonary embolism (780 [54.8%]); however, the total number of these services delivered was low relative to other services (Table 2).

The costliest low-value service was spinal injection for low back pain ($43.9 million), which represented 21.4% of overall spending on low-value care in FY18 (Table 3). Percutaneous coronary intervention with balloon angioplasty or stent placement for stable coronary disease ($36.8 million, 17.9% of overall spending) and back imaging for nonspecific low back pain ($25.4 million, 12.3% of overall spending) were the second and third costliest services, respectively.

Table 3. Cost of Low-Value Health Services Delivered by Veterans Health Administration (VA) Facilities and in VA Community Care Programs in Fiscal Year 2018.

| Low-value health services by domain | Costa | |

|---|---|---|

| Millions of dollars | Proportion of overall cost, % | |

| Cancer screening | ||

| PSA testing for men aged ≥75 y | 7.9 | 3.8 |

| Colorectal cancer screening for adults aged ≥75 y | 4.3 | 2.1 |

| Cervical cancer screening for women aged ≥65 y | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Cancer screening for patients with CKD receiving dialysis | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Total | 13.0 | 6.3 |

| Imaging | ||

| Imaging for patients with nonspecific low back pain | 25.4 | 12.3 |

| Screening for carotid artery disease in asymptomatic adults | 19.6 | 9.5 |

| Head imaging for uncomplicated headache | 12.7 | 6.2 |

| Head imaging for syncope | 3.1 | 1.5 |

| CT of the sinuses for uncomplicated acute rhinosinusitis | 1.5 | 0.7 |

| Screening for carotid artery disease for syncope | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| Imaging for diagnosis of plantar fasciitis | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| EEG for headaches | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Total | 64.7 | 31.4 |

| Preoperative testing | ||

| Chest radiography | 8.7 | 4.2 |

| Echocardiography | 7.9 | 3.8 |

| Stress test | 7.5 | 3.7 |

| Pulmonary function test | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| Total | 25.1 | 12.2 |

| Diagnostic and preventive testing | ||

| PTH measurement for patients with stage 1-3 CKD | 4.5 | 2.2 |

| 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D testing in the absence of hypercalcemia or decreased kidney function | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| Total or free T3 level testing for patients with hypothyroidism | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| Homocysteine testing for cardiovascular disease | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| BMD testing at frequent intervals | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Hypercoagulability testing for patients with deep vein thrombosis | 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Total | 7.0 | 3.4 |

| Other procedures | ||

| Spinal injection for low back pain | 43.9 | 21.4 |

| Arthroscopic surgery for knee osteoarthritis | 3.0 | 1.4 |

| Total | 46.9 | 22.8 |

| Cardiovascular testing and procedures | ||

| Stress testing for stable coronary disease | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| PCI with balloon angioplasty or stent placement for stable coronary disease | 36.8 | 17.9 |

| IVC filters to prevent pulmonary embolism | 6.4 | 3.1 |

| Renal artery angioplasty or stenting | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic patients | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total | 49.0 | 23.8 |

| Grand total | 205.8 | 100 |

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CT, computed tomography; EEG, electroencephalogram; IVC, inferior vena cava; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PTH, parathyroid hormone; T3, triiodothyronine.

Cost is derived from the use of low-value health services by specific criteria and is based on standardized cost estimates for each low-value service generated by the VA Health Economics Resource Center. For each low-value service, we applied the cost directly attributable to the Current Procedural Terminology code recorded for the service and the costs attributable to any facility fees or other necessary ancillary tasks, such as venipuncture for a low-value blood test or sedation for a low-value procedure.

Additional information on the overall use and cost of low-value services delivered by VA facilities and through VACC programs by sensitive criteria is listed in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Use of Low-Value Services Within Service-Specific Cohorts

As shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement, within each cohort of veterans eligible for a specific low-value service (eg, those with a history of low back pain at risk of receiving low-value back imaging), the low-value services most frequently delivered were prostate-specific antigen testing for men aged ≥75 years (26.5 [34.9] per 100 male veterans aged ≥75 years), head imaging for syncope (19.1 [47.3] per 100 veterans with syncope), and preoperative chest radiography (16.3 [52.4] per 100 veterans undergoing selected surgeries).

Sensitivity Analysis Incorporating Medicare Data

Integration of diagnosis codes and other historical data from Medicare into the specific criteria resulted in a decrease of 2 percentage points in the count of low-value services from 17.5 to 17.2 services per 100 veterans (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Both preoperative testing and diagnostic and preventive testing exhibited absolute increases in low-value service counts of 0.1 per 100 veterans. The domain with the greatest decrease was low-value cancer screening, with a decrease in testing of 0.4 per 100 veterans (decrease of 6.1 to 5.7 low-value tests per 100 veterans).

Discussion

In this national cross-sectional study of VA-enrolled veterans, 19.6 low-value services per 100 veterans were delivered by VA facilities or VACC programs in FY18 when applying the specific criteria, affecting more than 1 in 10 veterans. When applying the sensitive criteria, 44.8 low-value services per 100 veterans were delivered, affecting approximately 1 in 5 veterans. Total costs ranged from $205.8 million to $698.9 million for the specific and sensitive criteria, respectively, which represents 0.003% to 0.01% of total FY18 VA expenditures ($72.3 billion). Our findings distinguish which low-value services were most frequently delivered to veterans overall and by VA or VACC setting and identify services that were most prevalent in the overall cohort vs within each service-specific cohort. Finally, rates of low-value care exhibited only minimal changes when integrating Medicare data, indicating that despite veterans’ routine receipt of care from non-VA sources, VA data alone may be reliably used to adjudicate whether a service received by a veteran from a VA facility or VACC program is a potentially low-value service.

This study represents, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive analysis of the use and costs of low-value services either directly delivered or paid for by the VA. Previous studies that evaluated low-value service use among VA-enrolled veterans largely focused on individual services delivered directly by VA facilities.3,7,8,9 More recently, Kerr et al23 convened an expert Delphi panel of VA clinicians to identify low-value services of greatest priority for deimplementation within the VA. Our findings build on and reinforce these studies by revealing that low-value care is prevalent within the VA across a wide variety of health services, many of which align with those identified by Kerr et al.23

In addition, most low-value services identified in our study were delivered directly by VA facilities, which reflects the degree to which veterans received care directly from the VA relative to VACC programs; only 32% of veterans in our cohort received any service through VACC programs. For example, PSA testing for prostate cancer was the most common low-value service in our cohort. This finding reflects how the VA-enrolled population receives the bulk of their primary care services directly from VA facilities.7,24,25 In contrast, veterans most commonly use VACC programs to receive specific subspecialty services.26 Correspondingly, the low-value services most commonly delivered in VACC were spinal injection and imaging for low back pain. These differences have the potential to evolve over time as more VA-enrolled veterans begin to receive community care through the full implementation of the MISSION Act, which was passed in 2019.

Despite the VA operating as an integrated delivery and financing system with a unified electronic medical record, this study suggests that low-value care is prevalent within the VA. However, the overall count of low-value service use by specific criteria was approximately two-thirds that of Medicare beneficiaries, despite incorporating 3 additional low-value services in this study.4 Many of the common factors believed to incentivize the delivery of low-value care in Medicare, including operating within a fee-for-service delivery model and fear of malpractice litigation, are not present within the VA, suggesting that the drivers of low-value care are diverse and less tied to financial incentives than is commonly perceived.27 These differences may also be a result of differences in the case mix of VA vs Medicare beneficiaries (eg, differences in sex distribution and comorbidity burden). Our study lays the groundwork for ongoing research to identify these drivers and understand VA clinicians’ perspectives on incentives, disincentives, and practice environments at their facilities, which may influence their decision to engage in or avoid low-value service use.

The VA has asserted its commitment to improving the quality and value of care for veterans, and our findings have the potential to enhance efforts to systematically track and ultimately reduce the low-value services that veterans receive from VA facilities or VACC programs. Through its Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning system, the VA monitors facility-level performance across numerous quality measures, but not health care value. By using administrative data, our approach may be integrated into the VA’s existing infrastructure to develop new value-based metrics. In addition, the VA is increasingly serving as a payer of health services through VACC programs, but no tools are currently in place to measure the quality and value of care delivered through VACC. As participation in these programs continues to grow, the VA must ensure that care delivered in these community settings is of comparable quality and value to that delivered directly by VA facilities, and our findings may serve as a starting point for such initiatives.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, there are inherent challenges in measuring health care value by using administrative data, because value is a subjective construct. Application of both sensitive and specific criteria to identify each low-value service may account for such uncertainty by establishing a range of potentially low-value care. However, the extent to which the services identified in this study are truly inappropriate is not clear and may differ across populations. Second, we did not conduct a formal comparison between the delivery of low-value services in VA facilities vs VACC programs. Veterans are referred to VACC programs to receive specific services, and as a result, they have much more limited opportunities to receive low-value care through VACC programs than through VA facilities. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is much less low-value service delivery in VACC programs vs VA facilities. Although our findings suggest which low-value services are most common in VACC programs vs VA facilities, they do not indicate the relative performance of the VA vs VACC in avoiding low-value care when specific diagnoses or referrals occur in each setting, presenting an important direction for future research. Finally, our use of Health Economics Resource Center estimates to determine cost may not reflect the total cost of each low-value service, which may also include costs related to any subsequent care or harms veterans may experience as part of a low-value care cascade.

Conclusions

The findings from this cross-sectional study suggest that low-value care is common and costly across a variety of services within the VA. To ensure that veterans receive high-value care in any setting, our findings may provide a foundation for the development of policies and interventions to more carefully monitor and ultimately reduce low-value care delivered directly by VA facilities and inform the development of value-based standards for non-VA clinicians who participate in VACC programs.

eTable 1. Low-Value Service Definitions

eTable 2. Administrative Codes Used to Identify Relevant Medical History, Exclusion Criteria, and Low-Value Service Use

eFigure. Construction of the Cohort

eTable 3. Overall Use and Cost of Low-Value Services Delivered by VA Facilities and in VA Community Care in Fiscal Year 2018 Applying the Sensitive Criteria

eTable 4. Overall Use of Low-Value Services in FY2018 Among Veterans at Risk to Receive Each Service Applying the Specific and Sensitive Criteria

eTable 5. Changes in Detection of Low-Value Service Use Delivered by VA Facilities When Integrating VA and Medicare Data to Identify Veterans Satisfying the Specific Criteria for Each Low-Value Health Service

References

- 1.Korenstein D, Chimonas S, Barrow B, Keyhani S, Troy A, Lipitz-Snyderman A. Development of a conceptual map of negative consequences for patients of overuse of medical tests and treatments. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1401-1407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1501-1509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke JF, Kerr EA, McCammon RJ, Holleman R, Langa KM, Callaghan BC. Neuroimaging overuse is more common in Medicare compared with the VA. Neurology. 2016;87(8):792-798. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM. Measuring low-value care in Medicare. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1067-1076. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid RO, Rabideau B, Sood N. Low-value health care services in a commercially insured population. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1567-1571. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mafi JN, Russell K, Bortz BA, Dachary M, Hazel WA Jr, Fendrick AM. Low-cost, high-volume health services contribute the most to unnecessary health spending. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1701-1704. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Radomski TR, Huang Y, Park SY, et al. Low-value prostate cancer screening among older men within the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(9):1922-1927. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubenstein JH, Pohl H, Adams MA, et al. Overuse of repeat upper endoscopy in the Veterans Health Administration: a retrospective analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(11):1678-1685. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saini SD, Powell AA, Dominitz JA, et al. Developing and testing an electronic measure of screening colonoscopy overuse in a large integrated healthcare system. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(suppl 1):53-60. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3569-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller G, Rhyan C, Beaudin-Seiler B, Hughes-Cromwick P. A framework for measuring low-value care. Value Health. 2018;21(4):375-379. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Community Care. 2018. US Department of Veterans Affairs . Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.va.gov/communitycare/.

- 12.Kizer KW. Veterans and the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2012;307(8):789-790. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gellad WF. The Veterans Choice Act and dual health system use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):153-154. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3492-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghaferi AA, Schwartz TA, Pawlik TM. STROBE reporting guidelines for observational studies. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(6):577-578. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.0528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health Services Research & Development: Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). US Department of Veterans Affairs . Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm.

- 16.Community Care Data - Program Integrity Tool (PIT). US Department of Veterans Affairs . Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.herc.research.va.gov/include/page.asp?id=choice-pit.

- 17.Schwartz AL, Chernew ME, Landon BE, McWilliams JM. Changes in low-value services in year 1 of the Medicare Pioneer Accountable Care Organization Program. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1815-1825. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Radomski TR, Feldman R, Huang Y, et al. Evaluation of low-value diagnostic testing for 4 common conditions in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2016445. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radomski TR, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, et al. VA and Medicare utilization among dually enrolled veterans with type 2 diabetes: a latent class analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):524-531. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3631-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Average cost. US Department of Veterans Affairs . Accessed October 13, 2021. https://www.herc.research.va.gov/include/page.asp?id=average-cost.

- 21.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.VA priority groups. US Department of Veterans Affairs . Accessed January 26, 2022. https://www.va.gov/health-care/eligibility/priority-groups/.

- 23.Kerr EA, Klamerus ML, Markovitz AA, et al. Identifying recommendations for stopping or scaling back unnecessary routine services in primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(11):1500-1508. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.4001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walter LC, Bertenthal D, Lindquist K, Konety BR. PSA screening among elderly men with limited life expectancies. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2336-2342. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.So C, Kirby KA, Mehta K, et al. Medical center characteristics associated with PSA screening in elderly veterans with limited life expectancy. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(6):653-660. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1945-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattocks KM, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Kinney R, Elwy AR, Cunningham KJ, Mengeling MA. Understanding VA’s use of and relationships with community care providers under the MISSION Act. Med Care. 2021;59(suppl 3):S252-S258. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oakes AH, Radomski TR. Reducing low-value care and improving health care value. JAMA. 2021;325(17):1715-1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.3308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Low-Value Service Definitions

eTable 2. Administrative Codes Used to Identify Relevant Medical History, Exclusion Criteria, and Low-Value Service Use

eFigure. Construction of the Cohort

eTable 3. Overall Use and Cost of Low-Value Services Delivered by VA Facilities and in VA Community Care in Fiscal Year 2018 Applying the Sensitive Criteria

eTable 4. Overall Use of Low-Value Services in FY2018 Among Veterans at Risk to Receive Each Service Applying the Specific and Sensitive Criteria

eTable 5. Changes in Detection of Low-Value Service Use Delivered by VA Facilities When Integrating VA and Medicare Data to Identify Veterans Satisfying the Specific Criteria for Each Low-Value Health Service