Abstract

Background.

Rotavirus is a common cause of acute gastroenteritis and has also been associated with generalized tonic-clonic afebrile seizures. Since rotavirus vaccine introduction, hospitalizations for treatment of acute gastroenteritis have decreased. We assess whether there has been an associated decrease in seizure-associated hospitalizations.

Methods.

We used discharge codes to abstract data on seizure hospitalizations among children <5 years old from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. We compared seizure hospitalization rates before and after vaccine introduction, using Poisson regression, stratifying by age and by month and year of admission. We performed a time-series analysis with negative binomial models, constructed using prevaccine data from 2000 to 2006 and controlling for admission month and year.

Results.

We examined 962 899 seizure hospitalizations among children <5 years old during 2000–2013. Seizure rates after vaccine introduction were lower than those before vaccine introduction by 1%–8%, and rate ratios decreased over time. Time-series analyses demonstrated a decrease in the number of seizure-coded hospitalizations in 2012 and 2013, with notable decreases in children 12–17 months and 18–23 months.

Conclusions.

Our analysis provides evidence for a decrease in seizure hospitalizations following rotavirus vaccine introduction in the United States, with the greatest impact in age groups with a high rotavirus-associated disease burden and during rotavirus infection season.

Keywords: Rotavirus, seizures, vaccine

Rotavirus is a common cause of acute gastroenteritis in children. Severe rotavirus-associated acute gastroenteritis frequently results in viremia, making extraintestinal manifestations of the disease possible [1]. Several case reports have described central nervous system complications associated with rotavirus infections, including seizures [2–5]. Seizures in hospitalized children with laboratory-confirmed rotavirus infections have been characterized in retrospective chart reviews. The majority of cases were generalized tonic-clonic afebrile seizures [2, 6]. In a prospective study examining viral illnesses in children presenting with firsttime seizures, researchers found that children with seizures not associated with febrile illness were more likely to have acute gastroenteritis, compared with those who had febrile seizures [7].

Two live, oral rotavirus vaccines are currently licensed and available in the United States: a 3-dose pentavalent reassortant vaccine containing strains of bovine and human origin (RotaTeq [RV5]; Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ) and a 2-dose monovalent vaccine based on an attenuated rotavirus strain of human origin (Rotarix [RV1]; GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium). In 2006, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended routine vaccination of US infants with RV5 and, in 2008, updated the recommendations to include RV1 [8, 9]. Rotavirus vaccine introduction in the United States has substantially decreased acute gastroenteritis–associated hospitalizations, with a recent analysis demonstrating that, from 2008 to 2012, all-cause acute gastroenteritis–associated hospitalization rates in US children <5 years of age declined by 31%–55% [10]. Given the association between rotavirus infection and seizures, we would expect a reduction in hospitalizations for acute gastroenteritis due to rotavirus to correlate with a decrease in seizure-associated hospital admissions.

The impact of rotavirus vaccination on the risk of seizures in children has not been extensively studied. In the United States, rotavirus vaccination was associated with a reduction in the risk of seizure requiring hospitalization or emergency department care in the year following vaccination [11]. In Spain, researchers found that annual hospitalization rates for seizures in children <5 years old correlated with rotavirus vaccine coverage and rates of hospitalization due to rotavirus-associated gastroenteritis [12]. The objective of the current evaluation is to examine the incidence and population-level trends in seizure-associated hospitalizations among children <5 years old in the United States before and after rotavirus vaccine introduction.

METHODS

Data were extracted from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), produced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The HCUP is currently the largest collection of nationwide and state-specific longitudinal hospital care data in the United States and enables research on a range of health policy issues. Forty-eight states and the District of Columbia contribute full-year hospitalization data, which is sent to HCUP for standardization and subsequently released to researchers [13]. The State Inpatient Databases component of HCUP captures all hospitalizations occurring in community hospitals in participating states. This evaluation was conducted through active collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Because hospitalization data were deidentified and provided in summary form, informed consent was not required for this analysis.

All discharges for seizure hospitalizations were identified using the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, in any diagnostic position, for the diagnosis at discharge of seizure of determined etiology: 780.3 (convulsions), 779.0 (convulsions in newborn), 333.2 (myoclonus), and 345 (epilepsy).

The analysis was restricted to 26 states that consistently reported data each year during the study period, from 2000 to 2013. These states include the following: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and West Virginia. According to the National Center for Health Statistics’s Bridged Race population estimates for 2000–2013, approximately 72% of children <5 years old in the United States resided in these 26 consistently reporting states. Hospitalization rates were calculated by dividing the annual number of hospitalizations by the number of children <5 years old residing in the 26 participating states during that year, using the National Center for Health Statistics’ bridged-race postcensal population estimates for 2000–2013 as the denominator [14]. Hospitalization rates were further analyzed by admission month, sex, and age group (ie, 0–2, 3–5, 6–11, 12–17, 18–23, 24–35, 36–47, 48–59 months). Admission month data were available for 23 states (excluding Florida, Michigan, and New York), comprising 60% of the US population aged <5 years old.

To compare hospitalization rates for seizures before and after rotavirus vaccine licensure, we compared the mean hospitalization rate for calendar years 2000–2006 with that for calendar years 2008–2013. Data from 2007 were excluded because rotavirus vaccine coverage rates were low and uneven during the first year after vaccine introduction. Poisson regression was used to generate estimates of rates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and rate ratios for the periods before (reference) and after vaccine introduction, by admission year, admission month, and age group.

To further understand potential differences in seizure hospitalization rates before and after vaccine introduction, we performed a time-series analysis. Negative binomial models were constructed using data before vaccine introduction (ie, during 2000–2006) and controlling for month and year to account for seasonal and secular trends in seizure hospitalizations. Parameter estimates were then used to generate expected counts and rates for seizure-related hospitalizations for 2000–2013, using population estimates as described above. These analyses were stratified by age group. In the body text, we present the age groups when the burden of rotavirus is the greatest: 0–59 months, 6–11 months, 12–17 months, and 18–23 months. The other age groups (0–2 months, 3–5 months, 24–35 months, 36–47 months, and 48–59 months) appear in the Supplementary Materials. Observed rates were plotted against expected rates.

This project was determined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to be exempt from institutional review board review because data were derived from a publicly available deidentified administrative data set.

RESULTS

We examined 962 899 seizure hospitalizations among children <5 years of age during 2000–2013. Male children composed 55% of seizure hospitalizations (330 340 of 598 888). Neonates (age 0–2 months) composed 22% of the study population (127 959 of 592 721 individuals), and 24–35-month-old children composed 14% (81 001; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients With Seizure Data Abstracted From the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)

| Variable | Seizures, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group, mo | |

| 0–2 | 127 959 (21.6) |

| 3–5 | 39 189 (6.6) |

| 6–11 | 71 945 (12.1) |

| 12–17 | 81 001 (13.7) |

| 18–23 | 63 371 (10.7) |

| 24–35 | 87 098 (14.7) |

| 36–47 | 66 973 (11.3) |

| 48–59 | 55 185 (9.3) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 330 340 (55.2) |

| Female | 268 548 (44.8) |

Data are from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP; [13]) and include the following states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and West Virginia.

Before vaccine introduction (ie, during 2000–2006), the estimated mean annual seizure hospitalization rate among children <5 years old was 388 cases/100 000 (95% CI, 387–390). The seizure hospitalization rate varied substantially by age, ranging from 176 cases/100 000 (95% CI, 174–178) in children 48–59 months of age to 1631 cases/100 000 (95% CI, 1620–1642) in children 0–2 months of age. Annual seizure hospitalization rates after vaccine introduction among all children <5 years of age were 1%–8% lower than rates before vaccine introduction, with the greatest differences apparent in the later years of the analysis period (Table 2). The greatest reduction in rates (by 14%–16% in 2013 as compared to 2000–2006) was seen in children 0–2 months old and those 12–23 months old (Table 2). Higher rates of seizure hospitalization were observed among male children, although rate reductions were similar for male and female children (data not shown).

Table 2.

Estimates of Seizure Rates Before (During 2000–2006) and After Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction, by Age Group

| Age, Time Analyzed | Seizure Rate, Cases/100 000 (95% CI) | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–59 mo | |||||

| Before introduction | 388.48 (387.27–389.69) | 1 | |||

| After introduction | |||||

| 2008 | 382.26 (379.15–385.39) | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | .0003 | ||

| 2009 | 383.42 | (380.30, 386.56) | 0.99 | (0.98, 1.00) | .003 |

| 2010 | 373.74 | (370.66, 376.85) | 0.96 | (0.95, 0.97) | <.0001 |

| 2011 | 374.90 | (371.81, 378.02) | 0.97 | (0.96, 0.97) | <.0001 |

| 2012 | 365.48 | (362.42, 368.57) | 0.94 | (0.93, 0.95) | <.0001 |

| 2013 | 357.09 | (354.05, 360.15) | 0.92 | (0.91, 0.93) | <.0001 |

| 6–11 mo | |||||

| Before introduction | 453.09 | (449.01, 457.20) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | |||||

| 2008 | 477.47 | (466.67, 488.53) | 1.05 | (1.03, 1.08) | <.0001 |

| 2009 | 480.45 | (469.43, 491.73) | 1.06 | (1.03, 1.09) | <.0001 |

| 2010 | 463.87 | (452.99, 475.02) | 1.02 | (1.00, 1.05) | .069 |

| 2011 | 457.87 | (447.08, 468.92) | 1.01 | (0.99, 1.04) | .42 |

| 2012 | 438.19 | (427.61, 449.04) | 0.97 | (0.94, 0.99) | .012 |

| 2013 | 443.59 | (432.95, 454.51) | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.00) | .11 |

| 12–17 mo | |||||

| Before introduction | 535.35 | (530.88, 539.85) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | |||||

| 2008 | 539.76 | (528.22, 551.56) | 1.01 | (0.99, 1.03) | .49 |

| 2009 | 506.20 | (495.00, 517.66) | 0.95 | (0.92, 0.97) | <.0001 |

| 2010 | 505.61 | (494.24, 517.24) | 0.94 | (0.92, 0.97) | <.0001 |

| 2011 | 484.73 | (473.62, 496.10) | 0.91 | (0.88, 0.93) | <.0001 |

| 2012 | 481.17 | (470.13, 492.48) | 0.90 | (0.88, 0.92) | <.0001 |

| 2013 | 450.76 | (440.04, 461.74) | 0.84 | (0.82, 0.86) | <.0001 |

| 18–23 mo | |||||

| Before introduction | 419.11 | (415.16, 423.09) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | |||||

| 2008 | 409.73 | (399.69, 420.02) | 0.98 | (0.95, 1.00) | .095 |

| 2009 | 416.39 | (406.24, 426.79) | 0.99 | (0.97, 1.02) | .63 |

| 2010 | 401.05 | (390.93, 411.42) | 0.96 | (0.93, 0.98) | .002 |

| 2011 | 397.83 | (387.78, 408.14) | 0.95 | (0.92, 0.98) | .0002 |

| 2012 | 365.47 | (355.86, 375.34) | 0.87 | (0.85, 0.90) | <.0001 |

| 2013 | 361.99 | (352.40, 371.84) | 0.86 | (0.84, 0.89) | <.0001 |

Data are from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project [13] and include the following states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and West Virginia.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

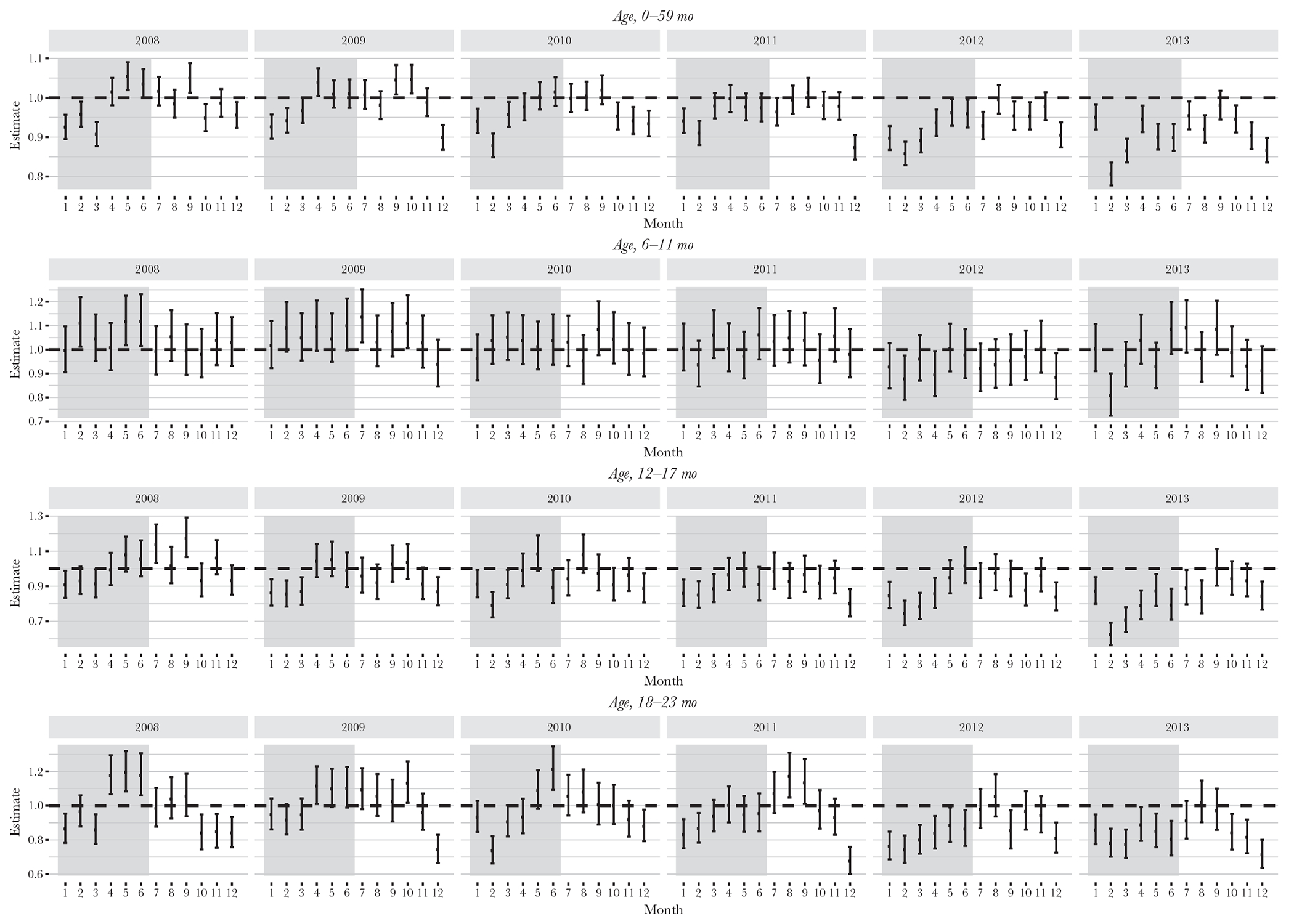

Stratification of seizure hospitalization rates by month and year revealed that the estimated rate ratios for months during the season of peak rotavirus infection (ie, during January–June) were generally lower than those for months in the nonrotavirus season, with this difference becoming more pronounced over time; in 2013, the estimated rate ratios during almost every month of the rotavirus season were statistically significant (Figure 1). Among children eligible to receive rotavirus vaccine, the greatest reduction in rotavirus season–specific seizure rates from the period before to the period after vaccine introduction (from 553 to 493 cases/100 000) was observed in 12–17-month-old children (Table 3). Seizure hospitalization rates in this age group were significantly reduced for most months of the rotavirus seasons during 2011–2013. A less pronounced effect was also seen in 18–23-month-old children (Figure 1). Rates were not consistently lower during the rotavirus season for children 6–11 months of age.

Figure 1.

Rate ratios and 95% confidence intervals for seizure hospitalizations before (during 2000–2006) and after (during 2008–2013) rotavirus vaccine introduction, by month, year, and age group. The shaded area indicates the historical peak rotavirus season of January–June. Poisson models were used to generate estimates, with population sizes drawn from census estimates. Seizure hospitalization data are from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (reference) and include 26 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and West Virginia.

Table 3.

Estimated Seizure Rates Before (During 2000–2006) and After (During 2008–2013) Rotavirus Vaccine Introduction, by Season and Age Group

| Age Group, Season,a Time Analyzed | Seizure Rate, Cases/100 000 (95% CI) | Rate Ratio (95% CI) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–59 mo | |||||

| Rotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 386.29 (384.39–388.20) | 1 | |||

| After introduction | 366.13 (364.17–368.11) | 0.95 (0.94–0.95) | <.0001 | ||

| Nonrotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 346.41 | (344.61, 348.22) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 334.75 | (332.87, 336.64) | 0.97 | (0.96, 0.97) | <.0001 |

| 6–11 mo | |||||

| Rotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 448.55 | (442.17, 455.03) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 453.52 | (446.62, 460.54) | 1.01 | (0.99, 1.03) | .3 |

| Nonrotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 401.48 | (395.45, 407.61) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 404.12 | (397.60, 410.74) | 1.01 | (0.98, 1.03) | .56 |

| 12–17 mo | |||||

| Rotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 552.60 | (545.46, 559.83) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 493.24 | (486.05, 500.53) | 0.89 | (0.88, 0.91) | <.0001 |

| Nonrotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 454.44 | (447.97, 461.00) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 429.88 | (423.18, 436.69) | 0.95 | (0.93, 0.97) | <.0001 |

| 18–23 mo | |||||

| Rotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 434.67 | (428.35, 441.09) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 401.00 | (394.53, 407.58) | 0.92 | (0.90, 0.94) | <.0001 |

| Nonrotavirus season | |||||

| Before introduction | 349.11 | (343.45, 354.87) | 1 | ||

| After introduction | 328.81 | (322.95, 334.77) | 0.94 | (0.92, 0.97) | <.0001 |

Data are from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project [13] and include the following states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and West Virginia.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

The peak season of rotavirus infection lasts from January to June.

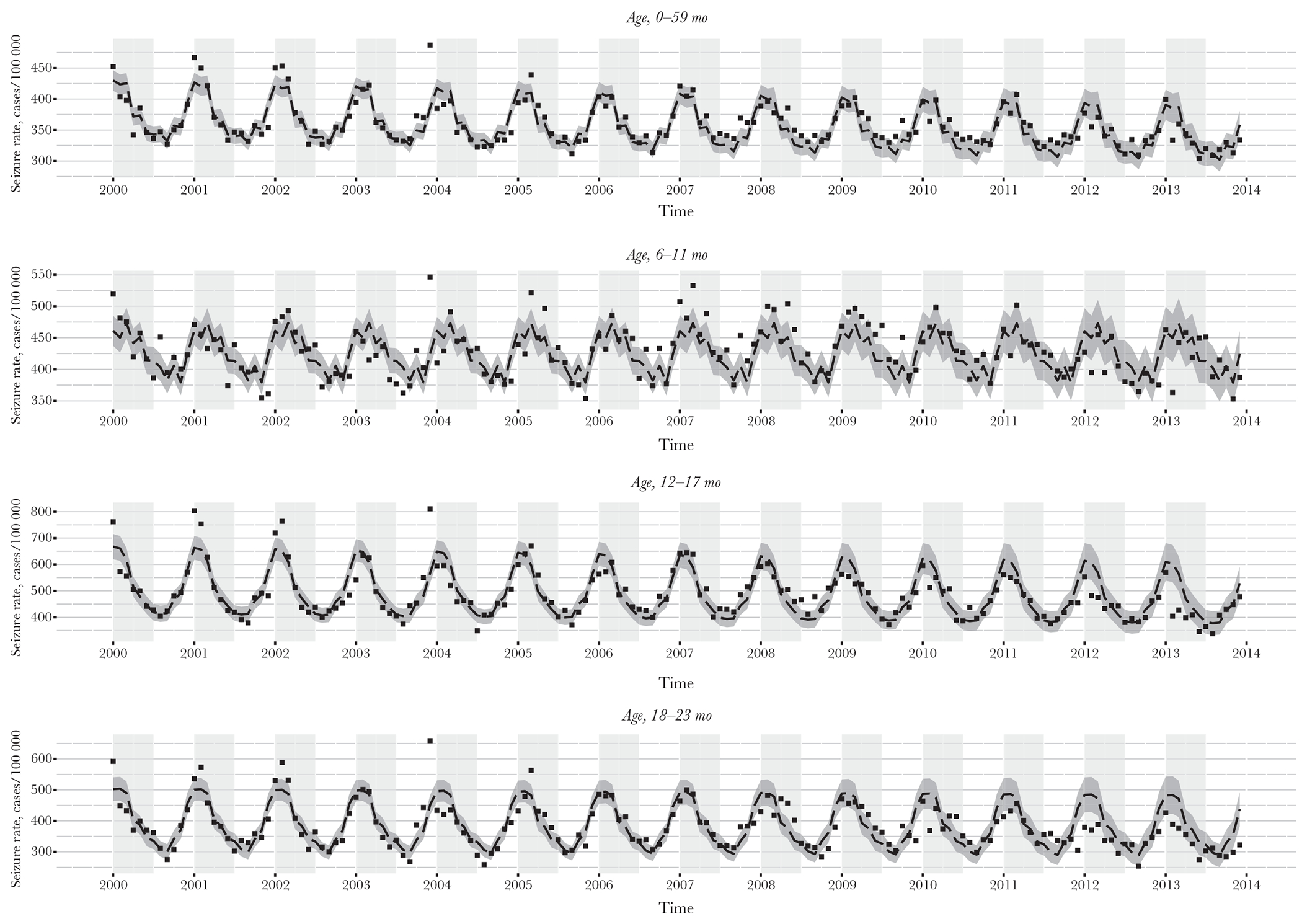

Time-series analyses demonstrated a decrease in the observed as compared to expected number of seizure-coded hospitalizations in children <5 years old in 2012 and 2013, with differences most notable during the rotavirus season. The 2 age groups with the largest decrease in seizure-coded hospitalizations were 12–17 months and 18–23 months. The 6–11-month age group showed a minimal decrease in seizure rates, and no difference was seen in the 24–35-month or 36–48-month age groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Estimates of predicted seizure hospitalization rates as compared to observed seizure hospitalization rates, 2000–2013, by month, year, and age group. The light gray shaded area indicates the historical rotavirus season of January–June. The dashed line indicates the estimated seizure rates, by month and year. The dark gray ribbon indicates the 95% confidence bounds for the estimated rates. The black squares indicate observed seizure rates, by month and year. Estimates were generated using predicted values from the results of negative binomial models run on age-stratified data from 2000 to 2006 and controlling for month and year. Population sizes were drawn from census estimates. Seizure hospitalization data are from the State Inpatient Databases of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (reference) and include 26 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Washington, Wisconsin, and West Virginia.

DISCUSSION

Overall, we documented a 4% decrease in seizure-coded hospitalizations in all children <5 years old from the period before to the period after rotavirus vaccine licensure. We observed the largest reduction in the rate of seizure hospitalizations in children 12–23 months of age, particularly during the traditional rotavirus season, from January to June. Larger decreases in the rate of seizure hospitalizations were observed in later years, when rotavirus vaccine coverage was higher. Rotavirus vaccine coverage increased steadily during the analysis period, from 63% in 2008 to 79% in 2013 [15]. These observations—that decreased seizure hospitalizations occurred in age groups more affected by rotavirus, occurred during the rotavirus season, and were more pronounced as rotavirus vaccine coverage increased—provide evidence to support that the rotavirus vaccine contributed to the decrease in seizure hospitalizations. This work supports previous findings by Payne et al, who used a distinct US database with different characteristics, including knowledge of vaccination status and availability of only 1 year of data after vaccine receipt, but it draws the same conclusion that rotavirus immunization has led to fewer seizure hospitalizations [11]. This US work also aligns with findings from a comparison of data on hospitalization due to seizures in Spain before versus after vaccine introduction [12].

Despite the observed decreases in seizure hospitalization rates, we see some inconsistencies in the data. We did not see a clear reduction in the rate of seizure hospitalization in infants aged 6–11 months, an age group that typically has a high burden of rotavirus infection. This may be due to the fact that seizures in children <1 year of age may not be due to a primary neurologic disorder but may have another etiology, such as a structural malformation or metabolic disorder. Furthermore, it commonly takes several months to determine seizure etiology in young children, which could lead to a higher proportion of nonspecific codes (eg, 780.39 [convulsions NEC]) in younger age groups. Seizure discharge codes likely become more specific as the child ages, as there has been more time for further testing and multiple clinical presentations of a neurologic disease over a period of months, leading to a more specific diagnosis. It seems likely that the 12–23-month-old children lay at the intersection of the high burden of rotavirus infections and the ability to assign more-specific neurologic codes [16]. Unfortunately, given the structure of our summarized database, we were unable to examine differences in coding practices by age. Additionally, overall rates of seizure hospitalizations decreased steadily over time and did not reflect the typical biennial pattern of rotavirus disease burden that has emerged in since rotavirus vaccine introduction, with small increases in the rotavirus disease burden in alternate years. This is likely because other factors have also contributed to the reduction in seizure hospitalizations, and we could not detect the subtleties of a biennial disease pattern with the limitations of our database.

Our analysis has some limitations. First, while the rotavirus ICD-9-CM code has been shown to be specific for identifying laboratory-confirmed rotavirus infections, <1% of our population carried the rotavirus-specific code during the years before and after vaccine introduction. This could be because afebrile infectious causes of seizures are not commonly considered in a child first presenting with a seizure. Second, for young children, particularly those <1 year of age, the diagnostic process can be challenging, and require multiple presentations and detailed diagnostic testing over a period of time. This may result in a lack of specific codes in children <1 year of age during initial clinical presentations. This results in artifacts in the ICD-9-CM codes. Additionally, a stool sample or a lumbar puncture must be collected or performed, respectively, to test for rotavirus, and these activities are not commonly done in children who present with generalized tonic-clonic seizures to the hospital. Finally, we do not know the rotavirus vaccination status of the children included in this analysis.

These findings suggest a possible additional vaccine benefit of decreasing hospitalizations due to rotavirus-related seizures, although there are some inconsistencies in the data. Efforts should continue to increase rotavirus vaccine coverage, which still remains an estimated 6–8 percentage points below that for diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis vaccine (DTaP) coverage [15]. Further understanding of the potential impact of rotavirus vaccination on seizure hospitalizations is needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the following HCUP state partners for their active support of this evaluation: the Arizona Department of Health Services, the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, the Colorado Hospital Association, the Connecticut Hospital Association, the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, the Georgia Hospital Association, the Hawaii Health Information Corporation, the Illinois Department of Public Health, the Iowa Hospital Association, the Kansas Hospital Association, the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services, the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission, the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis, the Michigan Health and Hospital Association, the Missouri Hospital Industry Data Institute, the New Jersey Department of Health, the New York State Department of Health, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, the Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems, the South Carolina Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Office, the Tennessee Hospital Association, the Texas Department of State Health Services, the Utah Department of Health, the Washington State Department of Health, the West Virginia Health Care Authority, and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Footnotes

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

References

- 1.Chitambar SD, Tatte VS, Dhongde R, Kalrao V. High frequency of rotavirus viremia in children with acute gastroenteritis: discordance of strains detected in stool and sera. J Med Virol 2008; 80:2169–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd MB, Lloyd JC, Gesteland PH, Bale JF Jr. Rotavirus gastroenteritis and seizures in young children. Pediatr Neurol 2010; 42:404–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch M, Lee B, Azimi P, et al. Rotavirus and central nervous system symptoms: cause or contaminant? Case reports and review. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:932–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isik U, Caliskan M. Reversible EEG changes during rotavirus gastroenteritis. Brain Dev 2008; 30:73–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyadurai S, Troester M, Harmala J, Bodensteiner J. Benign afebrile seizures in acute gastroenteritis: is rotavirus the culprit? J Child Neurol 2007; 22:887–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang B, Kim DH, Hong YJ, Son BK, Kim DW, Kwon YS. Comparison between febrile and afebrile seizures associated with mild rotavirus gastroenteritis. Seizure 2013; 22:560–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin ET, Kerin T, Christakis DA, et al. Redefining outcome of first seizures by acute illness. Pediatrics 2010; 126:e1477–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortese MM, Parashar UD; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2009; 58:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parashar UD, Alexander JP, Glass RI; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis among infants and children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leshem E, Tate JE, Steiner CA, Curns AT, Lopman BA, Parashar UD. Acute gastroenteritis hospitalizations among US children following implementation of the rotavirus vaccine. JAMA 2015; 313:2282–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payne DC, Baggs J, Zerr DM, et al. Protective association between rotavirus vaccination and childhood seizures in the year following vaccination in US children. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:173–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pardo-Seco J, Cebey-López M, Martinón-Torres N, et al. Impact of Rotavirus Vaccination on Childhood Hospitalization for Seizures. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34:769–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cost Healthcare and Project Utilization. SID database documentation. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/siddb-documentation.jsp. Accessed 8 June 2017.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Vital Statistics System, bridged race categories. Atlanta: CDC, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pringle K, Cardemil CV, Pabst LJ, Parashar UD, Cortese MM. Uptake of rotavirus vaccine among US infants at Immunization Information System Sentinel Sites. Vaccine 2016; 34:6396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinberg GA. Editorial commentary: unexpected benefits of immunization: rotavirus vaccines reduce childhood seizures. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58:178–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.