In 2019, the Advancing American Kidney Health (AAKH) Executive Order set a goal: by 2025, 80% of patients with incident kidney failure should be started on home dialysis therapies, or receive a kidney transplant. Racial and ethnic minority populations have a disproportionately high risk of kidney failure: Black and Latinx individuals have a 3.4-fold and 1.3-fold greater risk, respectively, compared with non-Latinx White people.1 Despite this, Black and Latinx patients are less likely than non-Latinx White patients to be treated with home dialysis: 7.3% of Black patients and 7.4% of Latinx prevalent patients with kidney failure are treated with home dialysis therapies, compared with 9.3% of non-Latinx White patients.1 The lower rates of home dialysis use in the Black and Latinx communities are not completely explained by geographic, demographic, and clinical factors.2 This perspective examines other contributing factors, specifically environmental, social, and system-level barriers to home dialysis faced by Black and Latinx patients with kidney failure. It also offers solutions to the problem of inequitable access to home modalities.

Barriers to Home Dialysis

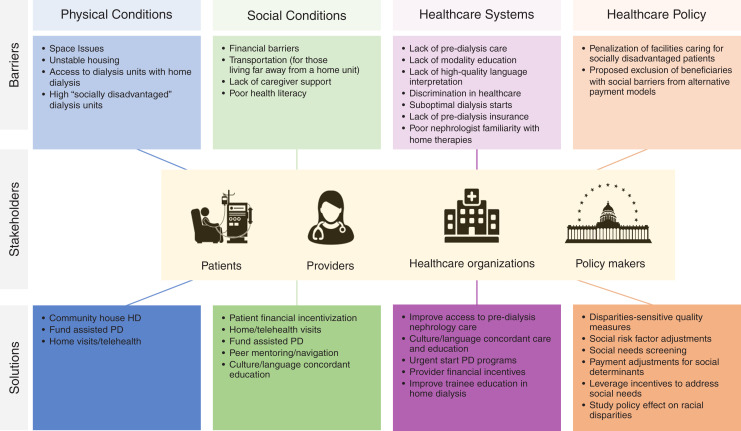

Many barriers to home dialysis exist, as do potential solutions to them (Figure 1). Environmental and social conditions, and health care systems and policies, all play pivotal roles in access to home dialysis.

Figure 1.

Barriers and potential solutions to racial and ethnic disparities in home dialysis care. HD, hemodialysis.

Environmental and Social Conditions

Lack of home space to store dialysis supplies and an absence of social support are more likely to be barriers to peritoneal dialysis (PD) use for patients with low income and education.3 Financial factors, such as the inability to pay for out-of-pocket costs for home dialysis and lack of health insurance, compound these challenges. In the United States, this has translated into community-level disparities. At the neighborhood level, zip codes with higher Black populations are associated with less home dialysis utilization.4 Dialysis facilities that serve higher numbers of incident Black and Latinx patients, patients who are uninsured or Medicaid-insured at dialysis initiation, or patients residing in neighborhoods of high social disadvantage have lower rates of home dialysis referral and initiation.5

Systems and Policies

Black and Latinx patients with kidney failure are more likely to have later referral to nephrologists, less predialysis nephrology care, inadequate patient-centered dialysis modality education, and higher rates of unplanned dialysis initiation than non-Latinx White patients. Lack of predialysis nephrology care is associated with less modality education and higher rates of urgent dialysis initiation, which is predominantly hemodialysis with a dialysis catheter, except in rare areas where urgent-start PD is offered. Even with adequate predialysis education, many patients report they did not make their own choice about dialysis modality.6 Provider bias may play a role in these provider-patient interactions, although this connection has not been studied in home dialysis.

At the policy level, many value-based models disproportionately penalize health care systems caring for racial and ethnic minorities. The ESRD Treatment Choices Model (ETC), introduced under the AAKH, aims to positively adjust Medicare payments for home-dialysis modality use. In its first ETC model, the Centers for Medicaid Services (CMS) considered excluding beneficiaries with social barriers (such as unstable housing) from home dialysis payment models under the ETC, potentially widening barriers to home dialysis. After public review, CMS has since made changes more broadly incorporating health equity into this model.7 To address social barriers, implementation of the models under the AAKH will require stakeholder and health system coordination to improve existing barriers and implement novel solutions.

Solutions

The AAKH initiative offers an opportunity for improving the care of patients with kidney disease who cannot be reached without strategic efforts to care for racial and ethnic minorities.

Several innovative strategies have demonstrated improved home dialysis access through addressing social and environmental barriers. Community house hemodialysis, where multiple patients perform home hemodialysis in a common house, is performed in New Zealand for those with unstable housing and has been especially helpful in Indigenous communities.8 Assisted PD (PD at home with the assistance of a trained caregiver) is reimbursed by health care systems in Canada, Denmark, and France. This addresses issues of social isolation, lack of caregiver support, and transportation.9 Further, telehealth appointments for those with adequate internet access and technological proficiency, or home visits may increase access for patients who do not live near a home dialysis clinic. Patient financial incentives, such as reimbursement for days off work for training, or covering travel costs for those who do not live close to a home dialysis clinic, can mitigate issues such as transportation barriers that often affect individuals with a lower income. Studies of peer navigators and mentors (typically nonmedical individuals who share patients’ lived experiences) have also demonstrated improved patient education, motivation, and quality of life in other health conditions.10

At the health care system level, changes to predialysis education and care delivery require an interdisciplinary effort. Nephrologists must be confident in their knowledge of home therapies to offer the modality, and to dispel the myth that patients from under-resourced communities are not good candidates. Financial incentives for providers to provide better predialysis care, including proper modality education, and high-quality home therapies, may encourage providers to build the infrastructure to facilitate home dialysis. Patient education must be provided in a culturally and language-concordant way. Providers should receive training to provide culturally responsive care and use language interpreters for patients with limited-English proficiency.11 Health care system–level changes to improve access to home dialysis includes wider implementation of urgent start PD programs. These programs allow patients who unexpectedly and urgently initiate dialysis, a population that is disproportionately Black, Latinx, and under-resourced, to start on home modalities.

At the policy level, socioeconomic disadvantage must be carefully and strategically addressed in payment models. Early value-based care models penalized health care systems taking care of socially disadvantaged patients.12 Indeed, the first version of the ETC under AAKH did not incorporate risk adjustment accounting for potential barriers to home dialysis, such as unstable housing or access to care, into payment models. This threatened to inadvertently penalize dialysis units and providers taking care of socially disadvantaged patients, through lack of financial incentivization and further limiting investment in care delivery required for those with more barriers to home dialysis. In response to this concern from stakeholders, the CMS released the Health Equity Incentive in October 2021, which aimed to improve financial incentives for patients who were dual eligible. These changes include a payment incentive for home dialysis and transplant uptake for dialysis facilities and providers managing lower-income beneficiaries, improved data collection monitoring health disparities, and limiting payment reductions under the ESRD Quality Incentive Program.7

Further revisions to the Health Equity Incentive may include incorporating disparity-sensitive quality measures, social risk factor adjustments, and universal social needs screening into alternative payment models to equitably meet AAKH goals.12 Reddy et al. have proposed utilizing payments through AAKH initiatives to further address barriers to home dialysis through novel means, including partnering with governments to prioritize subsidized housing for those unstably housed, allowing transitional care units to function as self-training units for home therapies, and incentivizing participant investments in RRT education and referral programs.13 In addition, the Improving Access to Home Dialysis Act was recently introduced in Congress. This act would allow Medicare to pay for assisted PD and require governments to study racial disparities in home dialysis use.

Despite the higher incidence and prevalence of kidney disease in Black and Latinx communities, home dialysis therapies are disproportionately underused. Meeting AAKH goals will require establishing systems and policies that center the margins, specifically addressing barriers faced by racial and ethnic minorities to equitably provide access to home dialysis care.

Disclosures

J.I. Shen reports having an advisory or leadership role as the Kidney Medicine Associate Editor, Peritoneal Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (PDOPPS) Steering Committee, Peritoneal Dialysis International Editorial Board North American Council of the International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis; and reports having other interests or relationships as a member of the ASN and National Kidney Foundation. K. Rizzolo reports having other interests or relationships with ASN Health Care Justice Committee. L. Cervantes reports receiving research funding from Retrophin; reports having an advisory or leadership role with Retrophin/Travere; and reports other interests or relationships with the National Kidney Foundation.

Funding

This work is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases/National Institutes of Health grant 5T32DK007135-46 (to K. Rizzolo)

Author Contributions

K. Rizzolo conceptualized the study; L. Cervantes, K. Rizzolo, and J. Shen were responsible for the formal analysis; L. Cervantes and J. Shen provided supervision; K. Rizzolo wrote the original draft; and L. Cervantes, K. Rizzolo, and J. Shen reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.System USRDS : USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Available at https://adr.usrds.org/2020/end-stage-renal-disease/1-incidence-prevalence-patient-characteristics-and-treatment-modalities. March 6, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen JI, Chen L, Vangala S, Leng L, Shah A, Saxena AB, et al. : Socioeconomic factors and racial and ethnic differences in the initiation of home dialysis. Kidney Med 2: 105–115, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prakash S, Perzynski AT, Austin PC, Wu CF, Lawless ME, Paterson JM, et al. : Neighborhood socioeconomic status and barriers to peritoneal dialysis: A mixed methods study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1741–1749, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walker DR, Inglese GW, Sloand JA, Just PM: Dialysis facility and patient characteristics associated with utilization of home dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1649–1654, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorsness R, Wang V, Patzer RE, Drewry K, Mor V, Rahman M, et al. : Association of social risk factors with home dialysis and kidney transplant rates in dialysis facilities. JAMA 326: 2323–2325, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wuerth DB, Finkelstein SH, Schwetz O, Carey H, Kliger AS, Finkelstein FO: Patients’ descriptions of specific factors leading to modality selection of chronic peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int 22: 184–190, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: CMS Takes Decisive Steps to Reduce Health Care Disparities Among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease . Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-takes-decisive-steps-reduce-health-care-disparities-among-patients-chronic-kidney-disease-and. Accessed April 7, 2022

- 8.Walker RC, Tipene-Leach D, Graham A, Palmer SC: Patients’ experiences of community house Hemodialysis: A qualitative study. Kidney Med 1: 338–346, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliver MJ, Salenger P: Making assisted peritoneal dialysis a reality in the United States: A Canadian and American viewpoint. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 566–568, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cervantes L, Hasnain-Wynia R, Steiner JF, Chonchol M, Fischer S: Patient navigation: Addressing social challenges in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 121–129, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cervantes L, Rizzolo K, Carr AL, Steiner JF, Chonchol M, Powe N, et al. : Social and cultural challenges in caring for Latinx individuals with kidney failure in urban settings. JAMA Netw Open 4: e2125838, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tummalapalli SL, Ibrahim SA: Alternative payment models and opportunities to address disparities in kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 77: 769–772, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy YNV, Tummalapalli SL, Mendu ML: Ensuring the equitable advancement of American Kidney Health-the need to account for socioeconomic disparities in the ESRD treatment choices model. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 265–267, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]