Racial and ethnic inequities in kidney disease in the United States have long been recognized. For example, since the 1980s the United States Renal Data System’s (USRDS’s) Annual Data Report has consistently demonstrated higher incidence and prevalence of ESKD and lower access to kidney transplantation among most non-White race and ethnicity groups in analyses adjusted for age and sex.1 Despite modest reductions in these disparities in the last two decades and evidence that biology, behavior, environment, clinical practices, and health policy play some role,2 disparities have not been eliminated; the incidence of ESKD remains more than three times higher among Black individuals than among their White counterparts. Continued surveillance sheds light on progress toward, and lends urgency for achieving, health equity. We spotlight disparities in care and outcomes among patients with CKD and ESKD using data from the USRDS.

Prevalence of CKD

The 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report charts racial and ethnic disparities and explores potential reasons for worse outcomes among Black and Hispanic patients throughout the spectrum of kidney disease, including CKD, AKI, ESKD, and transplantation.1 There has been a much smaller difference between Black and White individuals in the prevalence of early stages of CKD compared with the large differences in ESKD incidence. However, using different GFR estimating equations could lead to changes in the reported prevalence of CKD among Black individuals.

A joint National Kidney Foundation–American Society of Nephrology Taskforce recently recommended adopting a new eGFR equation that was refitted without an adjustment for Black race.3,4 The 2021 ADR included data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and presented the distribution of eGFR among Black, White, and Hispanic individuals using the previous CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation that includes a race adjustment5 and the new refitted equation.4 Use of the new equation leads to a higher eGFR and systematically lowers the estimated prevalence of CKD among White and Hispanic individuals and leads to a lower eGFR and increases the estimated prevalence of CKD among Black individuals. Thus, although there was little difference in the prevalence of eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73m2 between Black and White individuals using the older equation (7.7% of White and 6.4% of Black individuals among NHANES participants from 2015 to 2018), Black individuals had a higher, and White individuals a lower, prevalence of CKD according to the new estimating equation (9.3% of Black versus 5.8% of White individuals). In other words, Black individuals are estimated to have a 60% higher rate of stage 3–5 CKD than White individuals using the new equation. Without a “gold standard” of measured eGFR in NHANES, the higher prevalence could indicate that the old equations underdiagnosed CKD or that the new equations overdiagnose CKD. It is possible that wider use of equations that include both serum creatinine and cystatin C will lead to more accurate estimation of GFR for important medical decisions for all races.

Access to CKD Care and Social Determinants

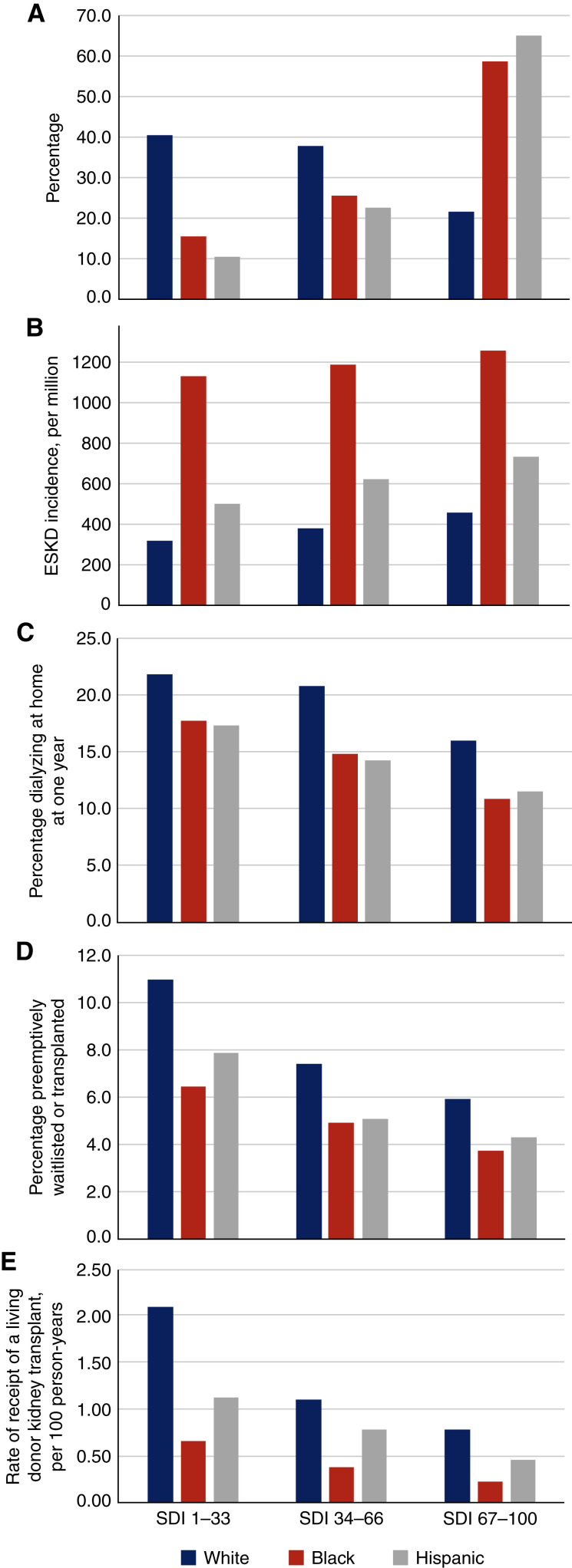

The disparity in kidney disease prevalence between Black and White individuals clearly widens as patients approach ESKD.1 Race may serve as a proxy for social, environmental, and structural factors that have important effects on health, or social determinants of health (SDOH). The Social Deprivation Index (SDI) is a composite measure of socioeconomic factors (education, living conditions, transportation, home ownership) derived from the American Community Survey6,7 at the ZIP code tabulation area level that can be used to examine the contribution of SDOH to racial and ethnic disparities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of race and ethnicity and SDI among patients with CKD and associations of race and ethnicity and SDI with CKD and ESKD outcomes. Higher SDI index indicates higher neighborhood deprivation. (A) The distribution of SDI by race and ethnicity groups among patients with CKD. (B) The incidence of ESKD per million population. (C) The percentage dialyzing at home 1 year after dialysis initiation. (D) The percentage listed for a transplant before dialysis initiation or receiving a transplant as the first treatment for ESKD. (E) The rate of receipt of a living-donor kidney transplant.

Access to CKD care may play a role in worsening racial disparities as kidney disease progresses. However, race and ethnicity and neighborhood deprivation were not associated with rates of outpatient nephrology visits and receipt of medications to treat CKD or its complications, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), potassium or phosphate binders, or sodium-glucost transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), among Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged ≥66 years.1 The lack of disparities in access to CKD care for older adults suggests that Medicare coverage, including Part D and the low income subsidy, provide comparable access to care for CKD across race and ethnicity groups and across levels of neighborhood deprivation. Medicare insurance has been shown to be an important leveler of disparities in access to medical care,8 including life-saving dialysis9 for Black versus White persons. However, research in other areas has suggested other factors including the quality of interactions between providers and patients (e.g., race and ethnicity concordance) may play a role in access to care.

Higher rates of hypertension and diabetes, which often begin at a younger age than among White individuals, likely contribute to the disparity in ESKD incidence among Black and Hispanic individuals. Indeed, persons of color are approximately 5 years younger at ESKD onset than their White counterparts. SDOH and barriers to access to care before Medicare eligibility likely contribute to the higher rates and earlier onset of diabetes and hypertension among Black and Hispanic individuals and to the higher risk of subsequent CKD and ESKD (Figure 1).

Access to ESKD Treatment and Social Determinants of Health

Patients’ race and ethnicity and neighborhood SDI are strongly associated with access to home dialysis and kidney transplantation.1 Black and Hispanic patients and those living in neighborhoods with high SDI scores are less likely to dialyze at home, to be waitlisted for a kidney transplant before initiating dialysis, and to receive a living donor kidney transplant than White patients and those living in less-deprived neighborhoods (Figure 1). Addressing barriers related to SDOH measures included in the SDI may be only part of the pathway toward successfully increasing utilization of home dialysis because the racial disparities are still present after accounting for neighborhood deprivation. Disparities in coronavirus disease 2019 mortality have been linked to structural factors, such as differences in the hospitals where members of different race groups receive care (i.e., health care segregation).10

Implementation of the new Kidney Allocation System for deceased kidney transplantation in December 2014 ameliorated disparities in access to deceased donor transplantation among Black patients with ESKD.1 Differences in living donor kidney transplantation and pre-emptive transplantation are now responsible for much of the ongoing disparity in overall access to transplantation between Black and White patients. These disparities are particularly significant because outcomes are superior for recipients of preemptive and living donor kidney transplants compared with recipients of deceased donor kidney transplants after ESKD onset. The discovery of APOL1 and evidence that donor kidneys with two high-risk alleles have worse graft survival could exacerbate access to these transplant modalities. Disparities in home dialysis and living donor kidney transplantation are also worthy of further scrutiny because fewer Black and Hispanic patients than White patients converted to home dialysis over the first year of treatment.1 Limited data make it difficult to examine the extent to which patients received appropriate education, guidance, or counseling about, and due consideration of, their candidacy for home dialysis and transplantation. To address these questions, there is an urgent need for data sources that probe more deeply into additional factors that may contribute to disparities, such as living conditions, social support, and trust in the health care system.

Caveats and Conclusions

It is important to understand that both neighborhood and individual-level social determinants may influence receipt of care.10 Using SDI, a measure at the ZIP code tabulation area rather than the individual level and grouping into three categories is crude and may underestimate the effects of SDOH. In addition, neighborhood or individual-level social factors may play a larger role in racial and ethnic disparities for some health or health care outcomes than others. Further examination of the contribution of SDOH at the neighborhood and individual level, along with the contribution of the myriad of other causes of disparities, should be a high priority. These should be assessed across the lifespan when risk factors for kidney disease develop and life changes ensue (e.g., changes in health insurance) and using more refined, sensitive tools. Determinants of racial and ethnic inequities including structural, interpersonal, and internalized racism should be uncovered with deeper measures, understood, and used as targets in interventions to improve and achieve health equity.

Disclosures

K. Johansen reports having consultancy agreements with Akebia; reports having an advisory or leadership role as a member of the Akebia Advisory Board and the Steering Committee for GlaxoSmithKline prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor clinical trials program; and other interests or relationships as Associate Editor for JASN. N. Powe reports receiving honoraria and having an advisory or leadership role as JASN Associate Editor, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, University of Washington, Vanderbilt University, and Yale University.

Funding

None.

Acknowledgment

The data reported here have been supplied by the USRDS. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the US government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Author Contributions

K. Johansen and N. Powe conceptualized the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript; and K. Johansen was responsible for the resources and wrote original draft.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System : USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Available at https://adr.usrds.org/2021. Accessed April 12, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powe NR: The pathogenesis of race and ethnic disparities: Targets for achieving health equity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 806–808, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delgado C, Baweja M, Crews DC, Eneanya ND, Gadegbeku CA, Inker LA, et al. : A unifying approach for GFR estimation: Recommendations of the NKF-ASN task force on reassessing the inclusion of race in diagnosing kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 2994–3015, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, et al. ; Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration : New creatinine- and cystatin C-based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med 385: 1737–1749, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips RL, Liaw W, Crampton P, Exeter DJ, Bazemore A, Vickery KD, et al. : How other countries use deprivation indices-and why the United States desperately needs one. Health Aff (Millwood) 35: 1991–1998, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robert Graham Center : Social Deprivation Index (SDI), Washington, DC, American Academy of Family Physicians, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wallace J, Jiang K, Goldsmith-Pinkham P, Song Z: Changes in racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and health among US adults at age 65 years. JAMA Intern Med 181: 1207–1215, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powe NR, Tarver-Carr ME, Eberhardt MS, Brancati FL: Receipt of renal replacement therapy in the United States: A population-based study of sociodemographic disparities from the Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II). Am J Kidney Dis 42: 249–255, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkin SS, Diez Roux AV, Coresh J, Fried LF, Jackson SA, Powe NR: Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and progressive chronic kidney disease in an elderly population: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Soc Sci Med 65: 809–821, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]