Community-Health Workers

Community-health workers (CHWs), such as patient navigators and promotoras, are lay, nonmedical individuals who are trusted and share the lived experience and characteristics of the community they serve (e.g., race and ethnicity, language, immigration status, socioeconomic challenges, medical illness).1 CHWs typically provide support with social- and health-related challenges. CHW interventions became an important community-based strategy to address health disparities after landmark research demonstrated their efficacy in reducing breast cancer screening and treatment disparities.1 CHW interventions deserve consideration to reduce kidney health disparities, particularly for individuals who experience poverty, and members of racial and ethnic minority groups who face a disproportionate burden of social and structural challenges.

Characteristics and Training of CHWs

Ideally, CHWs should mirror the demographics and language characteristics of their target community, and share experiences in facing social and structural challenges. A culture- and language-concordant CHW may more easily earn an individual’s trust, serve as a source of information, and provide a bridge to health care clinicians and services. A CHW with personal experience with kidney disease may be valuable, because they can empathize with patients and understand the health challenges imposed by kidney disease. The preferability of support from someone with personal experience with kidney disease was confirmed with qualitative findings that assessed the needs and preferences of Latinx individuals with kidney failure, and of interdisciplinary clinicians on how to best support Latinx individuals with kidney failure.2,3

Training for CHWs should be guided by, and specific to, the target community and intended outcomes. Training may include: (1) social risk assessment and how to identify resources and support for individuals with social and structural challenges; (2) behavioral training such as motivational interviewing and patient activation; (3) basic CHW skills (e.g., professional conduct, health promotion, care coordination, health care system overview, electronic health record, or computer training); (4) kidney-specific education and experience that may include clinical shadowing of interdisciplinary clinicians treating kidney disease.4

Opportunities for CHWs to Reduce Kidney Health Disparities

Health disparities in using home dialysis and receiving kidney transplant are especially prevalent among racial and ethnic minority groups and individuals who experience poverty.5 Challenges to increasing home dialysis and transplant include clinician, health-system, and patient-related factors. The Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative is a 2019 executive order that challenged the community to increase the number of individuals with kidney failure who receive either home dialysis or a kidney transplant.6 In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services implemented the ESRD Treatment Choices and the Kidney Care Choices models.7 CHWs trained in RRT options can provide emotional support, educate patients with low health literacy, support them in dealing with competing social challenges and language interpretation, accompany patients to key encounters, such as the first transplant center visit, or home-based clinician evaluation for home dialysis. CHWs can use their training in motivational interviewing and patient activation to strengthen a patient’s engagement in preparing for, and responding to, the demands related to RRT choice.

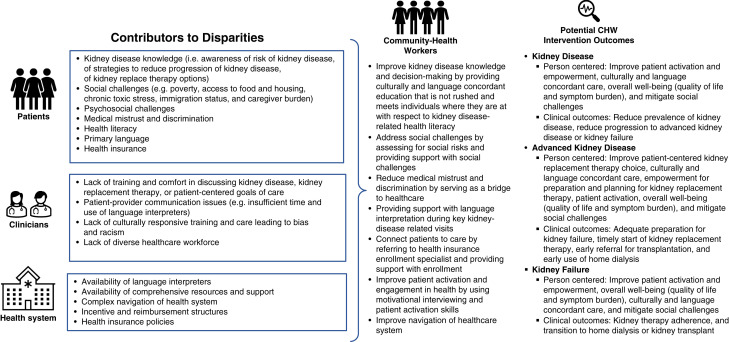

CHWs can also be active in: (1) supporting efforts to screen patients at risk for kidney disease to reduce the prevalence; (2) connecting patients with kidney disease to clinical care to reduce the progression of kidney disease to kidney failure; (3) providing support to patients with advanced kidney disease for shared decision-making regarding choice of RRT; and (4) improving the transition to transplant or dialysis for patients with kidney failure (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Contributors to disparities and opportunities for CHW interventions.

Example of CHW Intervention

We partnered with a community-advisory panel to create and pilot test a one-arm feasibility study of a CHW intervention in response to Latinx community members, indicating that socioeconomic challenges compounded by low health literacy and lack of language interpretation were the most distressing aspects of living with kidney failure.2,8 We are now conducting a small (140 Latinx participants) randomized trial of the CHW intervention at five inner-city dialysis centers in Denver. The CHWs consent for participants, and those randomized to the intervention receive at least five visits over 3 months. The CHW provides support with social challenges, language interpretation during key clinical visits, and uses motivational interviewing and patient activation to support patient-centered decision making. Visits occur at the dialysis center, at home, or at clinical encounters. The CHW works in partnership with social workers, who are often overwhelmed by the demand in urban dialysis centers. They are also often integrated into the interdisciplinary dialysis team meetings, because they can provide a deeper understanding of the social and structural challenges that may be influencing kidney care and adherence. We achieved a recruitment rate of approximately 80% for both studies because the CHW is not rushed, describes the study in a culturally and language concordant manner, and develops a personalized relationship. Our preliminary findings confirm the many social challenges that participants face, and demonstrate where a CHW has been crucial to improving patient-centered outcomes (i.e., outcomes that matter to, and are prioritized by, patients) such as support with social challenges and communication.

Building Sustainability

As we build an evidence base to demonstrate the effectiveness of CHW interventions, a key element will be research to demonstrate the cost effectiveness of CHWs in reducing kidney health disparities. Strategic advocacy will also require a policy analysis that describes legislative options. In 2021, the National Academy for State Health Policy released a report describing state-level approaches and financing strategies across the United States. The report stresses that CHWs are a “critical segment of the community-based workforce that is increasingly central to state workforce and equity planning.”9 As the evidence base for CHWs grows, there may be an opportunity to partner with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and include reimbursement for CHWs through value-based payment systems, bundled reimbursement, or alternative payment models. Additionally, as the effects of the ESRD Treatment Choices and Kidney Care Choices models on underserved populations are monitored, there may be an opportunity, even imperative, to integrate CHWs to further improve patient experiences and outcomes.

CHW interventions are a promising community-based approach to reduce kidney health disparities for racial and ethnic minorities and people that experience poverty along the kidney care continuum. Effectiveness, policy, and reimbursement considerations for CHW support must be prioritized to create sustainable change and meaningfully reduce disparities.

Disclosures

B. Robinson reports receiving research funding as the Principal Investigator of the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study Program, which is funded by a consortium of private industry, public funders, and professional societies, all support is provided without restrictions on publications; all funds are made to Arbor Research Collaborative for Health and not directly to Dr. Robinson; the full Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study Program support and additional support for specific projects and countries can be found at https://www.dopps.org/AboutUs/Support.aspx; reports receiving honoraria from consultancy fees or travel reimbursement in the last 3 years from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyowa Kirin Co., and Monogram Health, all paid directly to the institution of employment; and reports having an advisory or leadership role on the Editorial Board of the American Journal of Kidney Diseases. L. Cervantes reports receiving research funding from Retrophin; reports having an advisory or leadership role with Retrophin/Travere; reports other interests or relationships with the National Kidney Foundation; and reports receiving general research funds from DaVita, paid directly to the foundation at the institution of employment. L. Myaskovsky reports having an advisory or leadership role as Associate Editor for Clinical Transplantation; and reports other interests or relationships as the Director of the Center for Healthcare Equity in Kidney Disease, which is funded by Dialysis Clinic Inc., a national nonprofit dialysis provider. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant K23DK117018, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars grant 77887 (to L. Cervantes), NIH, National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities grant R01MD013752, and Dialysis Clinic Inc., a national nonprofit dialysis provider, grant C-3924 (to L. Myaskovsky).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Author Contributions

L. Cervantes, L. Myaskovsky, B. Robinson, and J. Steiner wrote the original draft and reviewed and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cervantes L, Hasnain-Wynia R, Steiner JF, Chonchol M, Fischer S. Patient navigation: Addressing social challenges in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 76: 121–129, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cervantes L, Jones J, Linas S, Fischer S. Qualitative interviews exploring palliative care perspectives of Latinos on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 788–798, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervantes L, Rizzolo K, Carr AL, Steiner JF, Chonchol M, Powe N, et al. : Social and cultural challenges in caring for Latinx individuals with kidney failure in urban settings. JAMA Netw Open 4: e2125838, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patient Navigator Training Collaborative : Leading and Administering a Patient Navigation Program. Available at: https://patientnavigatortraining.org/courses/level3//. Accessed April 1, 2022

- 5.United States Renal Data System : 2021 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Available at: https://adr.usrds.org/2021. Accessed April 1, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Advancing American Kidney Health : Executive Order 13879. July 10, 2019. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/07/15/2019-15159/advancing-american-kidney-health. April 1, 2022

- 7.Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services : CMS takes decisive steps to reduce healthcare disparities among patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-takes-decisive-steps-reduce-health-care-disparities-among-patients-chronic-kidney-disease-and. Accessed April 1, 2022

- 8.Cervantes L, Chonchol M, Hasnain-Wynia R, Steiner JF, Havranek E, Hull M, et al. : Peer navigator intervention for latinos on hemodialysis: A single-arm clinical trial. J Palliat Med 22: 838–843, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins EC, Wilkniss S, Tewarson H. National Academy for State Health Policy. Lessons for advancing and sustaining state community health worker partnerships. Available at: https://www.nashp.org/lessons-for-advancing-and-sustaining-state-community-health-worker-partnerships/. Accessed April 1, 2022