Abstract

Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) tractography is an advanced imaging technique that enables in vivo reconstruction of the brain’s white matter connections at macro scale. It provides an important tool for quantitative mapping of the brain’s structural connectivity using measures of connectivity or tissue microstructure. Over the last two decades, the study of brain connectivity using dMRI tractography has played a prominent role in the neuroimaging research landscape. In this paper, we provide a high-level overview of how tractography is used to enable quantitative analysis of the brain’s structural connectivity in health and disease. We focus on two types of quantitative analyses of tractography, including: 1) tract-specific analysis that refers to research that is typically hypothesis-driven and studies particular anatomical fiber tracts, and 2) connectome-based analysis that refers to research that is more data-driven and generally studies the structural connectivity of the entire brain. We first provide a review of methodology involved in three main processing steps that are common across most approaches for quantitative analysis of tractography, including methods for tractography correction, segmentation and quantification. For each step, we aim to describe methodological choices, their popularity, and potential pros and cons. We then review studies that have used quantitative tractography approaches to study the brain’s white matter, focusing on applications in neurodevelopment, aging, neurological disorders, mental disorders, and neurosurgery. We conclude that, while there have been considerable advancements in methodological technologies and breadth of applications, there nevertheless remains no consensus about the “best” methodology in quantitative analysis of tractography, and researchers should remain cautious when interpreting results in research and clinical applications.

1. Introduction

Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging (dMRI) tractography is an imaging method that uniquely enables in vivo reconstruction of the brain’s white matter connections at macro scale (Basser et al., 2000). Since the first dMRI tractography methods were proposed in 1998–2000 (Basser, 1998; Basser et al., 2000; Conturo et al., 1999; Mori et al., 1999; Westin et al., 1999), tractography has enabled mapping of the brain’s structural connectivity in many neurological applications such as aging, development and disease (Assaf and Pasternak, 2008; Ciccarelli et al., 2008; Essayed et al., 2017; Nucifora et al., 2007; Shi and Toga, 2017; Yamada et al., 2009). Initial applications of tractography enabled the visualization of white matter tracts, a primarily qualitative approach that remains highly relevant today both in the clinic (Abhinav et al., 2015; Essayed et al., 2017; Pujol et al., 2015) and for the study of neuroanatomy (Catani et al., 2002; Ciccarelli et al., 2003; Makris et al., 2005). Recently, quantitative approaches have become popular tools for studying the brains connectivity and tissue microstructure using tractography. In this paper, we provide a high-level overview of how tractography is used to enable quantitative analysis of the brain’s structural connectivity. This review is intended to be useful to researchers studying the white matter, developers of quantitative analysis methods, and clinicians interpreting results related to tractography.

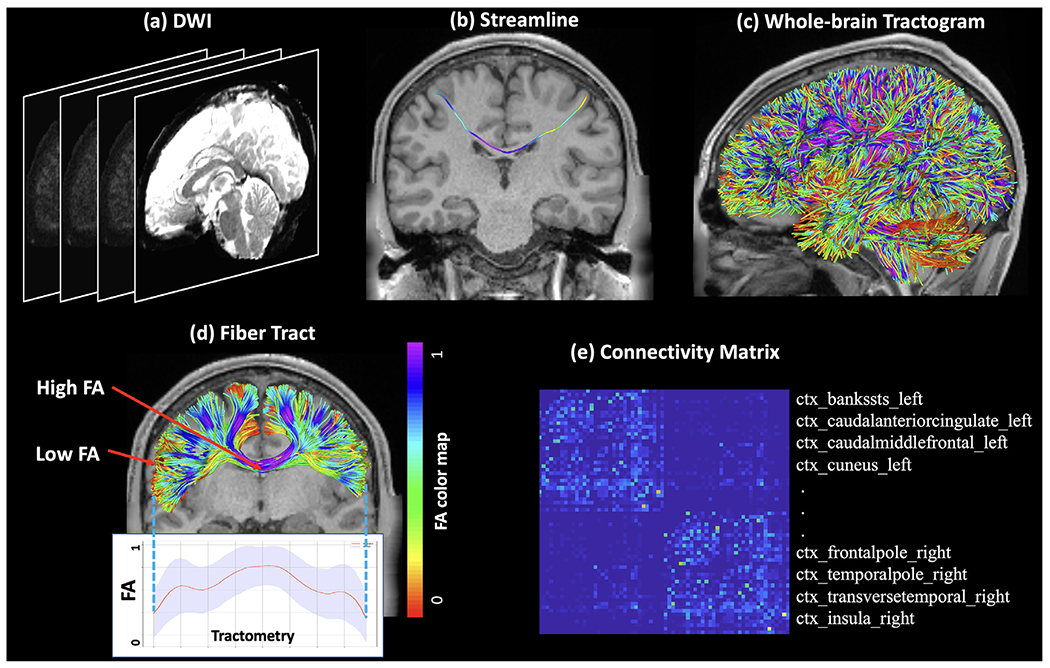

Due to the large number of proposed quantitative approaches and the evolution of the field over two decades, there is a proliferation of terminology related to the quantitative analysis of dMRI tractography. Therefore, we begin with a listing of common terms used throughout this paper and their definitions, as provided in Table 1. We also provide a visualization of many key concepts that will be used in the paper (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Common terms used throughout this paper and their definitions. We note that there are traditional terms that are widely used, but are not technically or biologically precise; in this table, we emphasize such terms and encourage the avoidance of their usage in future studies.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Tractography / Fiber tracking | Any computational process that estimates the anatomical trajectories of the white matter fiber pathways from dMRI data. Note: The term “Fiber tracing” and “Fiber tracking” are also widely used. However, we strongly suggest avoiding this term because “tracing” is frequently used in the context of ex vivo tracer injections, and “tracking” refers to following a moving object while white matter fibers do not move. |

| Streamline | A set of ordered points in 3D space, encoding a trajectory estimated through performing tractography (see Fig. 1(b)). Note: The term “fiber ” is also widely used. However, we strongly suggest avoiding this term because “fiber” is in reference to biology, while “streamline” implies the digital reconstruction of such. |

| Tractogram | A set of streamlines, often generated in such a way as to cover the entire white matter of the brain in order to capture any possible white matter connections. This can be referred to as a “whole-brain tractogram” (see Fig. 1(c)). |

| Steamline cluster/ Streamline connection/ Streamlines within an edge/ White matter parcel | A set of streamlines resulting from the subdivision of a tractogram. Such sets can result from a variety of methods for dividing the tractogram; hence there are several names in use for them. While such a set is often called a “fiber bundle,” “fiber tract,” or “fiber cluster” in the literature, to clarify that a set of streamlines is a computational data representation, we avoid using the word “fiber” in this paper. |

| Fiber Bundle / Fiber Tract / Fiber Fasciculus / Fiber Pathway | These terms have biological meanings as a set of white matter fibers (axons) forming a corticocortical or corticosubcortical connection in the brain (Schmahmann, Schmahmann, Pandya, 2009). In the neuroimaging literature, these terms are commonly used instead to refer to white matter connections reconstructed using tractography. Following this practice, in this paper we will use the terms “fiber tract,” “fiber bundle,” “fiber fasciculus,” or “fiber pathway” to refer to a white matter structure that corresponds to known anatomy with a traditional name (e.g., the corpus callosum or the corticospinal tract) (see Fig. 1(d)). |

| Brain Connectivity | In neuroimaging, the somewhat elusive and ambiguous concept of brain connectivity refers to measures of the structural and/or functional relationship between different brain regions (Horwitz, 2003; Rossini et al., 2019; Sakkalis, 2011; Uddin, 2013). |

| Structural Connectivity | A specific type of brain connectivity. Two brain regions are structurally connected if a fiber tract physically interconnects them. This is typically measured in vivo in humans using dMRI. However, there is no consensus on how this should be best quantified. Structural connectivity measures (also called “weights” or “strengths”) can include a variety of quantitative connectivity measures computed from a specific set of streamlines corresponding to a pathway of interest (e.g. those connecting two specific endpoints). The goal is often to approximate the true underlying fiber density or number of axons (Jones, 2010; Smith et al., 2020a). |

| Connectome / Brain Connectivity Matrix | A two-dimensional matrix wherein the rows and columns correspond to specific brain gray matter regions of interest (ROIs), and the value stored within each element of the matrix is the computed connectivity “ strength” between those regions corresponding to that row & column (Sporns, Tononi, Kötter, 2005) (see Fig. 1(e)). Such data are described mathematically as a graph. This matrix representation is directly inspired by invasive axonal tract-tracing experiments in animals, where the results of multiple studies are expressed as a quantitative connectivity matrix (Wakker et al., 2012). Without further specification, we use “connectome” throughout to implicitly refer to the structural connectome constructed using dMRI tractography, as opposed to those derived through other imaging modalities (e.g., functional MRI). |

| Diffusion Model | A theoretical model that connects the dMRI signal to salient features of tissue microstructure at the cellular level (Novikov et al., 2018; Panagiotaki et al., 2012; Yablonskiy and Sukstanskii, 2010). This includes tissue microstructure or biophysical models such as Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging (NODDI) (Zhang et al., 2012) and Free Water (FW) (Pasternak et al., 2012, 2009, as well as diffusion signal representations that include the diffusion tensor (Basser and Pierpaoli, 1996), diffusion kurtosis (Jensen and Helpern, 2010) and many others (Afzali et al., 2020; Alexander, 2006). |

| Microstructural Measure | Any parameter extracted from a diffusion model fit in each voxel that provides information regarding the underlying tissue microstructure (e.g., the fractional anisotropy (FA) that describes water diffusion anisotropy (Basser and Pierpaoli, 2011)). |

| Tractometry / Profilometry / Tract-based morphometry | An along-tract profiling analysis technique to investigate the distribution of the microstructural measures along the fiber pathway (Bells et al., 2011b; O’Donnell et al., 2009; Yeatman et al., 2012). |

Fig. 1.

Graphic illustration of tractography. (a) Example dMRI data, also known as diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) data. (b) An individual streamline computed after performing tractography. (c) An example whole-brain tractogram that consists of streamlines covering the entire white matter. (d) A fiber bundle that consists of a set of streamlines, representing an anatomical fiber tract named the corpus callosum. The streamlines are colored by a microstructural measure, i.e., fractional anisotropy (FA) that measures the anisotropy of water diffusion. The distribution of FA along the fiber tract is provided to show the tractometry of the tract. A low FA can be seen at the endpoint region of the streamlines (near the cortex) and a high FA can be seen in the middle of the streamlines (in the deep white matter). (e) An example brain structural connectivity matrix, which is constructed based on white matter tractography from the whole brain. Each row (and column) represents a brain gray matter ROI (See Fig. 3(c) for an example brain gray matter parcellation), and the value in an element of the matrix is the strength of the white matter connection between the two corresponding ROIs (quantified as the number of streamlines in this case).

Many quantitative tractography approaches can be applied to study the brain’s structural connectivity in health and disease. The fundamental goal of these analyses is to estimate quantitative measures of connectivity (or microstructure) of some pathway (or pathways) of interest. Quantitative analyses of tractography can be categorized into two main categories or styles: tract-specific analyses and connectome-based analyses (this categorization is helpful but imperfect, as some approaches blend aspects of both analysis styles). Tract-specific analysis refers to research that is typically hypothesis-driven and studies particular anatomical fiber tracts (Alexander et al., 2007; Levitt et al., 2020; Shany et al., 2017; Yeo et al., 2014). Tract-specific analysis has been increasingly adopted, particularly for the study of local white matter regions in health and disease (Alexander et al., 2007; Shany et al., 2017; Yeo et al., 2014). Connectome-based analysis refers to research that is more data-driven and generally studies the structural connectivity of the entire brain (Bastiani et al., 2012; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Sporns et al., 2005; Zalesky et al., 2012). This type of analysis aims to understand patterns of whole-brain anatomical connectivity, and therefore relies on tractography performed across the entire white matter.

In this paper, we first provide a brief introduction to tractography (Section 2), then a review of methodology for quantitative tractography analysis (Sections 3–5), followed by a review of studies that use quantitative tractography analysis to study the brain in health and disease (Section 6). For the methodology review, we organize the paper according to three main processing steps that are common across most approaches for quantitative analysis of tractography. The first common step corrects potential biases in tractography reconstruction that may otherwise be detrimental to, or outright preclude, quantitative analysis of such data; we refer to this as tractography correction (Section 3). The second common processing step identifies white matter pathways (e.g., subdivisions of the tractogram) that are meaningful for quantification of brain connectivity; we refer to this as tractography segmentation (Section 4). The third common step extracts quantitative indices that describe the microstructure and/or the “strength” of the brain connections; we refer to this as tractography quantification (Section 5). In each section, we aim to describe methodological choices, their popularity, and their potential pros and cons. Finally, we review studies that have used quantitative tractography approaches to study the brain’s white matter, including applications in development, aging, neurological disorders, mental disorders, and neurosurgery (Section 6).

2. Brief introduction to tractography

“Tractography” can refer to any computational process that estimates the anatomical trajectories of white matter fiber pathways from dMRI data. There are many methods available to perform tractography, including traditional streamline tractography based on the diffusion tensor model (Basser et al., 2000; Basser and Pierpaoli, 1996), which was originally proposed (as “hyperstreamlines”) for the visualization of tensor fields in the computer graphics community in 1993 (Delmarcelle and Hesselink, 1993). More recently, many streamline tractography methods using advanced diffusion models have been proposed and are under active development (Behrens et al., 2007; Descoteaux et al., 2008; Feng and He, 2020; Fernandez-Miranda et al., 2012; Friman et al., 2006; Jackowski et al., 2005; Jeurissen et al., 2014; Lazar and Alexander, 2005; Malcolm et al., 2010; Reddy and Rathi, 2016; Tournier et al., 2010; 2003; Wasserthal et al., 2019). Furthermore, many alternative tractography algorithms have been proposed, such as front evolution (Pichon et al., 2005; Sepasian et al., 2012; Tournier et al., 2003), geodesic (identifying likely connection trajectories based on assumed endpoints) (Jbabdi et al., 2008; 2007; Li et al., 2014; O’Donnell et al., 2002; Schreiber et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2009), atlas-based (Wasserthal et al., 2019; Yendiki et al., 2011), differential tractography (Yeh et al., 2019b) and various forms of “global” tractography that simultaneously fit the entire tractography reconstruction to all image data (either by progressively forming linked chains from a large set of randomly-initialized short segments (Christiaens et al., 2015; Fillard et al., 2009; Kreher et al., 2008; Mangin et al., 2013; Mangin et al., 2002; Reisert et al., 2011; Teillac et al., 2017)or iteratively perturbing a set of candidate trajectories (Battocchio et al., 2020; Close et al., 2015; Lemkaddem et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2012b). Work is additionally underway to improve tractography using machine learning (Neher et al., 2017; Poulin et al., 2019; Sarwar et al., 2020; Wasserthal et al., 2019; Wegmayr et al., 2018).

While a detailed introduction of tractography methods is out of the scope of this review, we refer the readers to these review papers (Jeurissen et al., 2019; Neher et al., 2015; Rheault et al., 2020b; Smith et al., 2020c) that are specific to tractography algorithms.

Many software packages are available to perform tractography research, including ANIMA (Descoteaux et al., 2008), BrainSUITE (Shattuck and Leahy, 2002), Camino (Cook et al., 2006), COMMIT (Daducci et al., 2013; 2014; Ocampo-Pineda et al., 2021; Schiavi et al., 2020a), Diffusion toolkit (Wang et al., 2007), Dipy (Garyfallidis et al., 2014), DMIPY (Fick et al., 2019), DSI studio (Yeh et al., 2013), DTIstudio (Jiang et al., 2006), ExploreDTI (Leemans et al., 2009), Fiber-Navigator (Chamberland et al., 2014), FSL (Jenkinson et al., 2012), MITK (Wolf et al., 2005), MRtrix3 (Tournier et al., 2012; 2019), PANDA (Cui et al., 2013), SlicerDMRI (Norton et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020b), TractSeg (Wasserthal et al., 2018), and Tracula (Yendiki et al., 2011). It is important to note that tractography is known to be sensitive to the choice of the underlying fiber tracking algorithms, which can further affect any subsequent quantitative analyses using the tractography data. On one hand, tractography results may vary across the large set of available diffusion models (Afzali et al., 2020; Alexander, 2006; Panagiotaki et al., 2012; Yablonskiy and Sukstanskii, 2010) and tractography methods (Basser et al., 2000; Behrens et al., 2007; Descoteaux et al., 2008; Feng and He, 2020; Fernandez-Miranda et al., 2012; Friman et al., 2006; Jackowski et al., 2005; Jeurissen et al., 2014; Lazar and Alexander, 2005; Malcolm et al., 2010; Reddy and Rathi, 2016; Tournier et al., 2010; 2003; Wasserthal et al., 2019). On the other hand, tractography results can also be sensitive to the choice of parameters (such as seeding and stopping thresholds) within a certain algorithm (Chamberland et al., 2014; Côté et al., 2013; Gong et al., 2018; Moldrich et al., 2010; Xie et al., 2020). While many research studies have been performed to compare different tractography algorithms (Bastiani et al., 2012; Fillard et al., 2011; Petrov et al., 2017; Pujol et al., 2015; Sinke et al., 2018; Wilkins et al., 2015; Zhan et al., 2015), there is no consensus on “the best algorithm.”

3. Improving tractography quality: methods for tractography correction

The goal of tractography correction methods is to tackle potential biases and errors that are produced in conventional or raw tractography algorithms. Where such an issue can be clearly demonstrated in exemplar data, and a tailored mechanism proposed that intrinsically addresses the issue, it is expected that the employment of such a mechanism in the reconstruction of empirical image data will lead to overall improved biological accuracy of the reconstruction (even in the absence of direct validation of such), which is important for the extraction of anatomical fiber tracts (Section 4.1) and the construction of quantitative structural connectivity matrices (Section 5.5). In this section, we consider the near-ubiquitous “streamlines” paradigm for dMRI tractography (Basser, 1998; Basser et al., 2000; Behrens et al., 2007; Conturo et al., 1999; Descoteaux et al., 2008; Feng and He, 2020; Fernandez-Miranda et al., 2012; Friman et al., 2006; Jackowski et al., 2005; Lazar and Alexander, 2005; Malcolm et al., 2010; Mori et al., 1999; Reddy and Rathi, 2016; Tournier et al., 2010; 2003; Wasserthal et al., 2019; Westin et al., 1999), and the ways in which specific undesirable behaviors or biases may be ameliorated through specific targeted mechanisms; see Fig. 2 for a visual summary of the relevant tractography biases included.

Fig. 2.

Demonstrations of various forms of errors and biases in tractography, as described in Section 3. Images are exemplars only; therefore there exist many other possible manifestations of such biases and errors. 1. Low-order integration methods under-estimate bundle curvature, leading to reconstructed paths overshooting the underlying curved trajectory. 2. In the absence of tailored constraints, streamlines may terminate in locations other than those known to contain axon synapses. 3. The number of streamlines generated within a bundle may not be proportional to the underlying axonal density of that bundle. 4. Because of the low resolution of diffusion MRI relative to the complexity of gyral folding, streamline termination may accumulate at gyral crowns rather than being distributed uniformly across the cortical ribbon. 5. Where macroscopic WM bundles intersect, streamlines may erroneously traverse part of one bundle and part of another, producing trajectories that are not present in the underlying structure (Schilling et al., 2021).

3.1. Curvature overshoot bias

Possibly the earliest bias established for dMRI tractography was the fact that if the streamline algorithm simply takes a step of finite size in the direction of the local fiber orientation at the current vertex (a so-called “first-order” method), streamlines in curved bundles will tend to under-estimate the curvature, resulting in erroneous trajectories (Tournier et al., 2002). While use of a step size that is small relative to the image voxel size mitigates the issue, use of a higher-order integration method during tracking that directly accounts for such curvature is a more direct solution (Basser et al., 2000). However, doing so in a manner that is compatible with diffusion models that account for crossing fibers can be technically difficult (Aydogan and Shi, 2020; Cherifi et al., 2018; Tournier et al., 2010).

3.2. Termination bias

“Termination” refers to the location at which the propagation of a streamline is ceased. Just as a tractography algorithm should produce streamlines whose tangents are faithful to the underlying fiber orientations, those streamlines should also terminate at locations corresponding to the endpoints of the underlying fiber tracts. Biases or inadequacies in such can result in partial fiber streamlines that stop prematurely in the white matter — despite the fact that white matter fibers synapse in the gray matter (Daducci et al., 2016) — or even that enter fluid-filled regions or cross sulcal banks. Such issues can be prevalent as tractography algorithms often operate using only the fitted diffusion model (e.g., diffusion tensor (Basser and Pierpaoli, 1996) or constrained spherical deconvolution (CSD) (Jeurissen et al., 2014; Tournier et al., 2007) in each image voxel. While these models provide strong evidence regarding fiber orientations to inform the direction of streamline propagation, the evidence they provide regarding where such fibers stop (and hence where streamlines should ideally be terminated) is weak (indeed, the diffusion-weighted signal itself does not provide direct evidence of fiber terminations (Smith et al., 2020b). Most fiber tracking algorithms exploit heuristic thresholds on features such as diffusion model anisotropy and streamlines curvature to serve as tractography termination criteria. However, the indirect nature of these metrics for this task, combined with the inferior spatial resolution of diffusion-weighted imaging, leads to such errors being highly prevalent (Smith et al., 2012). These common termination criteria are therefore not adequate to ensure biologically plausible streamline generation, resulting in a substantial proportion of streamlines from whole-brain tractography being unreasonable for quantification of white matter fiber connectivity (Yeh et al., 2016a).

The ill-posed nature of streamline terminations can be addressed by utilizing anatomical reference data to impose relevant prior information. This can ensure that the reconstructed streamlines fulfill some fundamental assumptions we could make, given an a priori understanding of how neurons are organized in the brain. For instance, axons emanate from cell bodies within the gray matter and connect to other cells elsewhere in either the brain or body, but they do not synapse in the middle of white matter or propagate into ventricles. Unlike conventional tractography algorithms, in which termination points can be distributed almost anywhere in the brain, the Anatomically-Constrained Tractography (ACT) framework (Smith et al., 2012) and similar methods (Girard and Descoteaux, 2012; Lemkaddem et al., 2014; Yeh et al., 2017) ensure that both streamline propagation and termination are constrained based on knowledge of where neuronal fibers locate, e.g., connecting between gray matter areas via the white matter. Although these methods cannot guarantee that every streamline accurately traces the complete trajectory of an underlying fiber connection, they do prevent the generation of streamlines that cannot possibly represent biological connectivity within the brain.

3.3. Connection density biases

While streamline tractography provides estimates of structural connection trajectories that are consistent with the underlying fiber orientations, it does not provide any guarantees regarding consistency between the number of such reconstructed connections with the density of those underlying fibers (i.e., the actual number of axons in a white matter region) (Jones, 2010; Jones et al., 2013). This limitation is often expressed as the mantra “streamline count is not quantitative.” There are myriad factors that may modulate the empirical streamline count between pathways, or within a pathway across individuals. Many are emergent phenomena from the nuances of the operation of any particular streamlines algorithm and therefore difficult to characterise. Nevertheless, the fact it can be trivially demonstrated that both that streamline count can be erroneously modulated in the absence of a difference in connection strength and erroneously constant in the presence of a difference in connection strength (Figs. 2, 3) highlights the inappropriateness of applying such a strong biological interpretation to raw streamline count.

Fig. 3.

Tractography segmentation: (a) Example whole-brain tractogram computed by performing tractography in DWI data; (b) Example anatomical tracts extracted from the tractogram; and (c) Example structural connectivity matrix constructed by performing whole brain tractography segmentation between all pairs of FreeSurfer cortical regions.

What would give greater confidence to the interpretation of tractography-based connection density as a quantitative measure is if, throughout the white matter, there were correspondence between the local density of reconstructed connections and the local density of fibers as evidenced by the diffusion image data (Smith et al., 2020a). Initially, aspiration for achieving this was limited to “global” tractography algorithms as mentioned in Section 2. More recently, methods have been devised to address this task by instead utilizing a pre-generated whole-brain streamline tractogram and modulating the contribution of each streamline toward the reconstructed white matter fiber density. Initial methods achieved this by selecting a subset of streamlines that best fit the diffusion image data, i.e., BlueMatter (Sherbondy et al., 2009), MicroTrack (Sherbondy et al., 2010) and SIFT (Smith et al., 2013), while later methods estimate a multiplier to be applied to each streamline, i.e., COMMIT (Daducci et al., 2013; 2014), LiFE (Pestilli et al., 2014), SIFT2 (Smith et al., 2015b), COMMIT2 (Schiavi et al., 2020a) and COMMIT2tree (Ocampo-Pineda et al., 2021); these “weights” represent an effective cross-sectional area of each streamline, which can be utilized as a direct measure of connection density (Smith et al., 2020a) (or indeed to modulate streamline contributions toward other aggregate measures of the connectivity “strength”; see Section 5).

3.4. Gyral bias

Gyral bias in tractography is the bias towards generating streamlines that terminate in gyri rather than sulci (Schilling et al., 2018a; Wu et al., 2020b), which reduces the agreement of the initiations or terminations of fiber streamlines with known ground truth from tracer studies and histology (Aydogan et al., 2018; Budde and Annese, 2013). The source of the gyral bias is multifactorial, such as the complexity of axon arrangement at the junction of cortical grey matter and superficial white matter (Van Essen et al., 2014). The partial volume effect from the limited MRI spatial resolution introduces difficulties in distinguishing complex fiber configurations based on the reconstructed fiber orientation distributions (FODs). Increasing the image resolution is beneficial to mitigate the gyral bias (Heidemann et al., 2012; Sotiropoulos et al., 2016), but is constrained by the signal-to-noise ratio of the acquired dMRI data. Even operating on high-resolution dMRI data, current tractography algorithms have been shown to deviate from the ground-truth fiber projections derived from histological staining, with greater streamline densities at gyral crowns than sulcal banks (Schilling et al., 2018b). The complex folding and convolutions of cortical gyri also pose challenges for the reconstruction of long-range connections (Reveley et al., 2015).

A surface flow approach has been proposed to model the arrangement of superficial axonal fibers at gyral crowns, thereby improving the consistency between streamlines’ initiations or terminations and the expectations from histological data (St-Onge et al., 2018). More recently, the gyral bias has been shown to be alleviated using an asymmetric FOD technique (Wu et al., 2020c), which can depict the highly-curved fiber geometry appearing at the superficial white matter (Bastiani et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020c).

3.5. False positive connections

Several orders of magnitude separate the resolution of dMRI acquisitions (cubic millimeters) from the typical size of the axons (few micrometers). This discrepancy introduces ambiguities in the white matter that can be compatible with multiple streamline configurations and are difficult for tractography to resolve (Girard et al., 2020; Guevara et al., 2012; Maier-Hein et al., 2017). This ill-posed nature of tractography has received a renewed interest in the past few years, and several studies have raised serious concerns about the anatomical accuracy of the reconstructions (Maier-Hein et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2014). In particular, it has been shown that tractography techniques suffer from a large number of false positives, i.e., streamlines that are reconstructed but do not correspond to real anatomical bundles, and that these erroneous connections can severely bias the estimation of connectivity (Drakesmith et al., 2015; Maier-Hein et al., 2017; Zalesky et al., 2016b). The anatomical accuracy of the reconstructions can be improved by manually filtering the streamlines with inclusion/exclusion ROIs, as seen in Section 4.1, but this requires prior knowledge of “where white matter pathways start, where they end, and where they do not go” (Schilling et al., 2020a). However, more automated procedures are desirable especially when analyzing large cohorts of subjects.

A widely-used approach to attempt to alleviate false positive connections when building a structural connectivity matrix is thresholding (Fornito et al., 2016), which refers to the removal of edges whose strength is smaller than a certain cut-off value. This strategy implicitly assumes a correlation between the strength of a reconstructed edge and its validity, which can be violated in a range of ways due to the errors produced by streamlines tractography not being simply random variance. The capacity for thresholding to differentiate between true and spurious connections remains a debated topic in the field.

Alternative solutions have been proposed, which are either knowledge- or data-driven. The former are described in Section 4.1, and typically use fully- or semi-automated algorithms, e.g., clustering, as a means to detect and discard streamlines considered outliers based on anatomical priors or geometrical properties, e.g., length and shape. On the other hand, the methods described in Section 3.3 for addressing density biases can also be used as filtering procedures, in which the streamlines that are not supported by the acquired dMRI data, i.e., whose estimated weight is zero, are discarded. While these approaches achieve good results in terms of removing duplicate streamlines or isolated ones that are likely spurious, actually none proved effective in discriminating between true and spurious connections in the connectome networks (Maier-Hein et al., 2017; Schiavi et al., 2020a).

It was recently demonstrated that the performance of filtering methods can be significantly boosted by combining knowledge- and data-driven strategies. These new formulations (Ocampo-Pineda et al., 2021; Schiavi et al., 2020a) allow taking explicitly into account two fundamental assumptions about the connections in the brain: (i) fibers are naturally organized in bundles (Mandonnet et al., 2018; Udin and Fawcett, 1988), and (ii) the number of bundles should be low to minimize the overall wiring cost (Bullmore and Sporns, 2012). This prior knowledge helps resolve some of the ambiguities present in the data and, as a consequence, allows significant improvement of the anatomical accuracy of the connectome (Ocampo-Pineda et al., 2021; Schiavi et al., 2020a). This is achieved by organizing the streamlines into groups and seeking for solutions which explain the measured signal with the minimum number of bundles, using the Group Lasso regularization (Yuan and Lin, 2006), thus promoting sparsity in the space of connections, rather than in the space of individual streamlines as implicitly done in previous filtering methods.

Research is still underway to determine the best method(s) for filtering, with some disagreement on the beneficial versus detrimental effect of these methods on the structural connectome (Buchanan et al., 2020; Civier et al., 2019; Drakesmith et al., 2015; Frigo et al., 2020; Schiavi et al., 2020a; Yeh et al., 2016a).

4. Defining regions for quantitation: methods for tractography segmentation

The goal of white matter tractography segmentation is to identify white matter pathways (e.g., subdivisions of the tractogram) that are meaningful for quantification of the brain’s structural connectivity. Critically, this step enables cross-subject quantitative comparison of the segmented white matter pathways; see (Smith et al., 2014) for a review of general considerations in multi-subject dMRI studies. (Tractography segmentation is also critical for qualitative applications such as visualization of fiber tracts, e.g., for neurosurgical white matter mapping; see Section 6.4.) Tractography segmentation methods can be generally grouped into two categories, related to the tract-specific and connectome-based analysis approaches, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The first category of methods identify anatomical white matter fiber tracts and label them with traditional names (such as the arcuate fasciculus or the corticospinal tract) (Section 4.1). The second category of methods parcellate, or subdivide, the entire white matter into many white matter parcels based on information about the streamline trajectories and/or endpoints (Section 4.2).

4.1. Anatomical tract identification

Anatomical tract identification aims to identify tractography streamlines that correspond to anatomically named white matter fiber tracts. This task is non-trivial, given the complex structures of the white matter anatomy and the large number of streamlines in the tractogram.

Conventional anatomical tract identification methods rely on manual streamline selection, also referred to as virtual dissection, where experts in anatomy interactively select tractography streamlines using manually drawn ROIs in the brain (Catani et al., 2002; de Schotten et al., 2011; Stieltjes et al., 2001; Wakana et al., 2007). Usually, inclusion ROIs are placed in the gray matter (cortical and subcortical) to define where the streamlines should terminate and in the white matter to define where the streamlines should pass, and exclusion ROIs are placed in other regions to exclude undesired streamlines (Rheault et al., 2020a; Wakana et al., 2007). Manual streamline selection is considered to be the gold standard to delineate anatomical fiber tracts in tractography and has been widely used to validate other anatomical tract identification techniques (Poulin et al., 2019; Pujol et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2020). Manual selection is also used in studies where specific clinical expertise is needed, e.g., for presurgical white matter mapping in tumor patients where the tumor and lesion can largely displace white matter fiber tracts (Radmanesh et al., 2015).

Due to the fact that manual tract selection is time-consuming and has high clinical and expert labor costs, modern studies increasingly focus on automated tract identification methods. These methods can be categorized into three categories: ROI-based, streamline labeling, and direct segmentation.

The ROI-based methods are the most commonly used. They automate ROI computation and perform streamline selection based on the ROIs a streamline terminates in and/or passes through. The majority of the ROI-based methods leverage a brain ROI atlas and use an image registration to automatically align the ROIs in the atlas space to the subject space (Allan et al., 2020; Astolfi et al., 2020; Hua et al., 2008; Lawes et al., 2008; Schurr et al., 2019; Verhoeven et al., 2010; Wassermann et al., 2016; Yeatman et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2008; 2010). Currently, popularly used brain ROI atlases include those provided in Freesurfer (Desikan et al., 2006; Fischl, 2012), MNI–ICBM152 (Mazziotta et al., 2001; Mori et al., 2008; Oishi et al., 2009; 2008), and JHU-DTI (Wakana et al., 2007; 2004) (see (Hansen et al., 2020) for a review of more atlases). There are also ROI-based methods that directly predict ROIs in subject space using machine learning (Astolfi et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020b).

The second category of automated tract identification methods, streamline labeling, assigns an anatomical label to each individual streamline. Often, streamline labeling is done by computing the geometric distance of each streamline to labeled streamlines in a reference tract segmentation, and then assigning a streamline label based on the closest reference tract (Bertò et al., 2020; Clayden et al., 2007; Gupta et al., 2018; 2017b; Kumar et al., 2019; Labra et al., 2017; Lam et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Maddah et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). There are also learning-based segmentation approaches that train a model from the reference tract segmentation data and predict an anatomical label for each streamline in a new subject (Gupta et al., 2018; 2017b; Kumar et al., 2019; Lam et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). To reduce the amount of labeling for each streamline, many streamline labeling methods first group streamlines into clusters (known as fiber clustering), followed by assigning an anatomical label for each cluster, thus labeling each streamline (Avila et al., 2019; Chekir et al., 2014; Garyfallidis et al., 2018; Guevara et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010; O’Donnell and Westin, 2007; Román et al., 2017; Ros et al., 2013; Siless et al., 2018; 2020; Tunç et al., 2014; Vázquez et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a; Yeh et al., 2018; Yoo et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018c; Ziyan et al., 2009).

The third category of automated tract identification is called direct segmentation in the literature (Bazin et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2019; Eckstein et al., 2009; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Ratnarajah and Qiu, 2014; Reisert et al., 2018; Rheault et al., 2019; Wasserthal et al., 2018; 2019; Yendiki et al., 2011; Zöllei et al., 2019). Unlike the aforementioned methods that work on precomputed tractography streamline data, the direct segmentation methods operate on DWI data (Yendiki et al., 2011; Zöllei et al., 2019) or derived volumetric image data (e.g., FOD maps (Wasserthal et al., 2018) and streamline density maps (Lu et al., 2020)) to predict the location for multiple tracts of interest, followed by performing tractography for only these tracts. Although the direct segmentation methods are relatively new and are relatively less used than the ROI-based and streamline labeling methods, the success of methods such as TRACULA (Yendiki et al., 2011), Tract-Seg (Wasserthal et al., 2018) and Bundle-specific tractography (BST) (Rheault et al., 2019) has shown highly promising tract segmentation performance.

There are several points that should be considered when selecting a method for anatomical tract identification. First, given the fact that there is no ground truth in tractography, validation of a tract identification method is difficult. One commonly used strategy to assess a tract identification method is to evaluate its reproducibility (in terms of intra- and inter-rater as well as test-retest reproducibility) (Rheault et al., 2020a; Tong et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Methods using manual streamline selection have been shown to be highly reproducible for specific tracts and segmentation protocols using the diffusion tensor tractography (Wakana et al., 2007), but with more modern multi-fiber tractography, reproducibility is lower, potentially due to the increase in spurious streamlines (Rheault et al., 2020a). However, manual streamline selection is still considered to be the gold standard for benchmarked comparisons and algorithm training (Kreilkamp et al., 2019; Wasserthal et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2010). For automated tract identification, one study indicates that streamline labeling has higher test-retest reproducibility than ROI-based segmentation (Zhang et al., 2019); however, no consensus has been reached given that many existing tract identification methods have not been compared. The second point is that a good tract identification method should be highly consistent across different populations and acquisitions (Sydnor et al., 2018; Wasserthal et al., 2018; Yendiki et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2018c). This is particularly important for automated tract identification methods, which are essential to perform across-lifespan and multi-site studies, which usually involve a large number of datasets (Alexander et al., 2017; Casey et al., 2018; Cetin-Karayumak et al., 2020; Harms et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2017). One factor that can affect the consistency of methods that segment tractography streamline data is the underlying tractography method that is employed. In general, studies indicate that modern multi-fiber tractography is more sensitive when performing tractography and thus is more consistent across subjects and timepoints than traditional single-fiber DTI tractography (Bucci et al., 2013; Prčkovska et al., 2016). The third point is that anatomical tract identification results can be highly variable across studies due to a lack of consistent fiber tract definitions, where different methods may give different results for the same target anatomical fiber tracts (Dick and Tremblay, 2012; Rheault et al., 2020a; Schilling et al., 2020b). Work is underway to provide sets of consistent rules for fiber tract definitions (e.g. the White Matter Query Language (Wassermann et al., 2016) and tractography-based fiber tract atlases (Mori et al., 2008; Yeh et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018c) that are provided in an open fashion for use and possible extension or modification by the community. The fourth point is that a method for performing tractography must be chosen: tract-specific tractography may be more computationally efficient if the number of tracts of interest is small, while whole-brain tractography can be computationally expensive but enables tract identification or parcellation of the whole white matter. (Note that a whole-brain tractogram is required for filtering (Sections 3.3 and 5.3) and analyses of the brain as a network using a connectivity matrix (Sections 5.5 and 5.6)). However, computation of whole-brain tractography considers the entire white matter simultaneously, estimating all fiber tracts using the same set of tractography parameters; this may not be ideal for fiber tracts that are difficult to compute using tractography, e.g., those requiring a lower anisotropy threshold, more lenient curvature threshold, or a dedicated tracking algorithm (such as the optic radiation (Sherbondy et al., 2008; Tax et al., 2014)). Recent approaches propose to better reconstruct white matter anatomy by exploring the tractography parameter space, e.g., by combining results from multiple tractography algorithms (“ensemble tractography”) (Takemura et al., 2016) and by exploring millions of parameter combinations (“augmented fiber tracking”) (Yeh, 2020). The fifth point is that selection of different tract identification methods may require different image registration methods. The ROI-based methods usually require volumetric registration (e.g., between a population T1-weighted template and individual dMRI data) to align ROIs to the dMRI space. While there are many sophisticated tools to compute these registrations such as FSL (Jenkinson et al., 2012) and ANTs (Avants et al., 2009), the performance is limited by nontrivial factors. For example, the intermodality registration between dMRI and T1-weighted images can be affected by differences in image resolutions (Malinsky et al., 2013) and echo-planar imaging (EPI) distortion in dMRI data (Albi et al., 2018). Many streamline labeling methods use streamline-based registration to directly align individual tractography data to a tractography atlas where a reference tract segmentation is available. Most widely used approaches perform a linear registration (Garyfallidis et al., 2015; O’Donnell et al., 2012), while many studies have proposed to perform non-linear approaches to enable deformations of the streamlines (Benou et al., 2019; Chandio and Garyfallidis, 2020; Olivetti et al., 2016). While using streamline-based registration can avoid the intermodality registration issue in ROI-based methods, streamline registration (especially a nonlinear registration) may be computationally heavier than volumetric registration. Most of the direct segmentation approaches use a training tract segmentation dataset and thus may not require image registration or require a small amount of work for registration (e.g., a rigid volumetric registration); however, we note that curation of a training tract segmentation dataset may require extensive work compared to performing image registration. Lastly, deep learning techniques have been increasingly applied for anatomical tract identification, showing high potential for future work and improvements in computational speed (Chen et al., 2021; Gupta et al., 2017a; 2018; 2017b; Lam et al., 2018; Reisert et al., 2018; Wasserthal et al., 2018; 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020a).

4.2. Parcellation of the whole-brain tractogram

Parcellation of the entire white matter (as represented by a whole-brain tractogram) aims to enable quantitative analysis of all possible white matter connections in the whole brain. There are generally two categories of methods: cortical-parcellation-based methods and fiber clustering methods (O’Donnell et al., 2013). The cortical-parcellation-based methods are more widely used as they enable construction of a connectivity matrix and its subsequent analysis using techniques from graph theory (as described in Section 5.6) (Bassett and Bullmore, 2017; Bullmore and Sporns, 2009a; Gong et al., 2009a; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Sporns et al., 2005; Yeh et al., 2016b; Zalesky et al., 2012). Though relatively less used, fiber clustering tractography parcellation methods are increasingly applied to study the brain’s structural connectivity in applications such as disease classification and between-population statistical analysis (Feng et al., 2020; Ji et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018a; 2018b). (Note that these methods could perhaps more correctly be called “streamline clustering,” but the term “fiber clustering” is very established in the literature.)

The cortical-parcellation-based methods work from a gray-matter-centric perspective. They parcellate tractography according to a cortical (and sometimes a subcortical) gray matter parcellation, focusing on the structural connectivity among different gray matter ROIs (Bassett and Bullmore, 2017; Bullmore and Sporns, 2009a; Gong et al., 2009a; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Sporns et al., 2005; Yeh et al., 2016b; Zalesky et al., 2012). Specifically, tractography segmentation is performed by extracting streamlines that connect pairs of ROIs. Therefore the resulting tractography segmentation is mainly determined by the selection of a cortical parcellation scheme. The majority of methods adopt a cortical parcellation that is computed from T1-weighted or T2-weighted MRI. The most popularly used cortical parcellation is the Freesurfer Desikan-Killiany cortical parcellation (Desikan et al., 2006; Fischl, 2012), while many other cortical parcellation schemes have also been widely used (Destrieux et al., 2010; Shattuck et al., 2008; Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002). Many cortical-parcellation-based methods have also used a functional cortical parcellation computed using functional MRI data (Eickhoff et al., 2005; Glasser et al., 2016; Schaefer et al., 2018; Yeo et al., 2011). Finally, an alternative approach is to use a vertex-wise cortical “parcellation,” i.e., by identifying streamlines that connect pairs of vertices in the cortical surface (Besson et al., 2014; Fellner et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2021). Currently, there is no consensus about which brain parcellation technique could be most useful (de Reus and Van den Heuvel, 2013; Yeh et al., 2020; Zalesky et al., 2012).

The fiber clustering methods work instead from a white-matter-centric perspective. They group tractography streamlines according to their geometric trajectories, describing the structural connectivity according to the white matter anatomy (Avila et al., 2019; Chekir et al., 2014; Garyfallidis et al., 2018; Guevara et al., 2012; Li et al., 2010; O’Donnell and Westin, 2007; Román et al., 2017; Ros et al., 2013; Siless et al., 2018; 2020; Tunç et al., 2014; Vázquez et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020a; Yeh et al., 2018; Yoo et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018c; Ziyan et al., 2009). In general, fiber clustering methods start with a computation of pairwise streamline geometric similarities, followed by a computational clustering method to group similar streamlines into clusters. Compared to the cortical-parcellation-based methods that focus on streamline terminal regions, fiber clustering methods leverage the full lengths of the streamline trajectories. As a result, the cortical-parcellation-based methods can erroneously group streamlines that follow completely different trajectories through the white matter but nevertheless end up at the same gray matter endpoints, whereas fiber clustering can be insensitive to streamlines diverging at the cortex if they pass through the same deep white matter regions. In addition, unlike the cortical-parcellation-based methods that leverage additional cortical parcellation information, the majority of fiber clustering methods work on tractography data only, such that there is no need for an inter-MR-modality registration, e.g., an image registration between dMRI and T1w images that can be affected by differences in image resolution (Malinsky et al., 2013) and echo-planar imaging (EPI) distortion in dMRI data (Albi et al., 2018). Due to these factors, several studies have demonstrated advantages of fiber clustering methods over the cortical-parcellation-based methods, including more consistent parcellation across subjects (Sydnor et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2017) and a higher reproducibility between test-retest scans (Zhang et al., 2019).

When choosing a method to perform parcellation of the entire white matter, the previously described points related to reproducibility and consistency of anatomical tract identification across different populations and acquisitions (as described in Section 4.1) are also important facts to consider (Buchanan et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2015a; Zhang et al., 2019; 2018d).

An additional point to be highlighted for parcellation of the entire white matter is the scale or the granularity of the parcellation, i.e., how many white matter parcels are to be obtained after parcellation. For constructing the connectome, this is related to the choice of the cortical parcellation (Hagmann et al., 2008a; Messé, 2020), while for fiber clustering this is related to the number of fiber clusters obtained by the clustering algorithms (Wu et al., 2020a; Zhang et al., 2018c). Various parcellation scales have been applied in different studies, ranging from tens to millions of white matter parcels (Besson et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017; Osmanlıoğlu et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2013; Zalesky et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2018a). Choosing parcellation scales depends on the target application, e.g., studies have suggested a fine scale white matter parcellation (over 2000 parcels) can be beneficial for machine learning and statistical analysis (Liu et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018a) while a coarse scale parcellation (fewer than 200 parcels) can improve the connectome consistency across individuals (Osmanlıoğlu et al., 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2013). We note that inter-subject connectome consistency may also be improved using other approaches, e.g., consistency-based thresholding (Baum et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2017).

5. Performing quantitative analysis: methods for tractography quantification

The goal of tractography quantification is to extract quantitative measures that are useful to assess the structural connectivity of the brain’s white matter pathways. In this section, we will first introduce the quantitative measures that can be computed from tractography (Section 5.1). Then we will focus on how to extract these measures within an individual white matter fiber pathway (Section 5.2) and how to perform filtering techniques to reduce potential biases in the extracted measures (Section 5.3). Next, we introduce how the extracted measures can be used for tract-specific analysis of anatomical white matter tracts (Section 5.4) and for computing the edge weights to construct a connectivity matrix (Section 5.5). Finally, we will introduce topological analyses of whole-brain connectivity based on graph theoretical measures and more advanced connectome measurements (Section 5.6).

5.1. Quantitative measures computed from tractography

There are many quantitative measures that can be computed from tractography, which can be subdivided into two categories based on the source of data used to compute the measures. The first category of quantitative measures are based on the tractography data alone, which are often used to define the connectivity strength (Jones, 2010; Smith et al., 2020a; Sotiropoulos and Zalesky, 2019; Yeh et al., 2020). The number of streamlines (NOS) is one widely used measure to quantify the connectivity strength (Hagmann et al., 2008b; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2016; Sporns et al., 2005; van Dellen et al., 2018). Several studies conducted on animals using invasive tract-tracing techniques have shown good agreement between the NOS and the biological connectivity as measured using ex vivo tract-tracing data (Delettre et al., 2019; Girard et al., 2020; van den Heuvel et al., 2015a). However, because of the difference in resolution between the measured dMRI signal and actual axon dimensions (as described in Section 3.3: “Connection density biases”), many studies have emphasized that NOS does not provide a truly quantitative measure of connection strength (Jones, 2010; Jones et al., 2013; Sotiropoulos and Zalesky, 2019; Yeh et al., 2020). Recent work aims to provide alternative, more quantitative measures of connectivity that better estimate the underlying connection density (Smith et al., 2020a) or modulate streamline contributions toward aggregate measures of connectivity (see Section 5.3). Other quantitative measures can be computed directly from tractography, such as the volume and the length of a fiber tract (Bajada et al., 2019; Behrman-Lay et al., 2015; Catani et al., 2007; Chandio et al., 2020a; Colby et al., 2012a; Grinberg et al., 2018; Rheault et al., 2020a; Song et al., 2015; Yeatman et al., 2012), have also been used.

The second category of quantitative measures computed from tractography leverages microstructural measures that are usually computed from a diffusion model (e.g., diffusion tensor model) or another quantitative imaging modality (e.g., myelin imaging). In this category of measures, tractography is generally used to define the locations in which microstructural measures are sampled. (This sampling may be done after performing tractography, or during performing tractography as part of sampling or computing a diffusion model). The most widely used microstructural measures are based on computational modeling of the dMRI signal. Popularly used diffusion-modeling-based microstructural measures include the fractional anisotropy, axial, radial and mean diffusivities (FA, AD, RD and MD respectively) derived from traditional diffusion tensor model (Basser and Pierpaoli, 1996). More advanced measures include those reflecting inter- and intra-cellular signal fractions derived from Diffusion Kurtosis Imaging (DKI) (Jensen and Helpern, 2010), Free Water modeling (Pasternak et al., 2012; 2009), Neurite Orientation Dispersion and Density Imaging (NODDI) (Zhang et al., 2012), Spherical Mean Technique (SMT) (Kaden et al., 2016), or Apparent Fiber Density (AFD) (Raffelt et al., 2012). It is important to be aware that changes in dMRI microstructural measures can be non-specific, in part due to the difference in scales between voxel-averaged dMRI signals (mm scale) and the scale of the individual axons and cells that are probed by the diffusing water (micrometer scale). For example, many factors (e.g., cell death, edema, gliosis, inflammation, change in myelination, increase in connectivity of crossing fibers, increase in extracellular or intracellular water, etc.) may cause changes in FA (Assaf and Pasternak, 2008; Jones et al., 2013; Le Bihan and Johansen-Berg, 2012). More details about sensitivity, specificity and interpretability of these microstructural measures are out of the scope of the present review but the reader can refer to the following studies (Alexander et al., 2019; Jelescu and Budde, 2017; Novikov et al., 2019; 2018). Other approaches for tractography quantification leverage information from imaging modalities other than dMRI, such as T1-weighted (T1w) imaging (Boshkovski et al., 2020a; Yeatman et al., 2014a), myelin sensitive maps (Lee et al., 2020; Mancini et al., 2020; Piredda et al., 2021) and g-ratio (Campbell et al., 2018). For example, researchers have used the longitudinal relaxation rate (R1), a measure sensitive to myelin, along the fiber tracts (Boshkovski et al., 2020a; Yeatman et al., 2012).

These microstructural measures can be computed along fiber pathways using several approaches. Usually, this is done by computing a model in each voxel to derive a 3D microstructural map (e.g., an FA image) and then using tractography to define the locations from which the values of this microstructural measure should be sampled. This sampling may be done by first generating a binary mask that defines the voxels through which streamlines pass and then sampling from an underlying microstructure image within this mask (Ciccarelli et al., 2003; Heiervang et al., 2006; Kunimatsu et al., 2004; Voineskos et al., 2010). The sampling may alternatively be done by sampling microstructural measures at each point of the streamlines from a pre-calculated microstructure image (Ciccarelli et al., 2003; Heiervang et al., 2006; Kunimatsu et al., 2004; Voineskos et al., 2010). Instead of using a pre-calculated microstructure image, the diffusion or fiber model can be simultaneously estimated when performing tractography so that the microstructural measures are directly computed at points along each streamline (Girard et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2018; Malcolm et al., 2010; Olszewski et al., 2017; Reddy and Rathi, 2016).

5.2. Domain of analysis: extraction of quantitative measures within white matter fiber pathways

After choosing a quantitative measure of interest (Section 5.1) and a method for tractography segmentation (Section 4), then there are many methods available to extract the measure within an individual white matter fiber pathway. This is important to enable tract-specific analysis (Section 5.4) and construction of a connectivity matrix (Section 5.5). Two main strategies can be employed: using a scalar value as a summary statistic, or using data along the length of the fiber pathway.

The most commonly adopted strategy for extraction of quantitative measures is to compute a scalar value as a summary statistic of the fiber pathway. (This is required for connectome-based analysis and is a popular approach for tract-specific analysis). While some quantitative measures intrinsically provide a single scalar value per pathway, e.g. NOS or tract volume, others (e.g. sampled values of a quantitative metric) necessitate calculation of some statistic in order to produce such a scalar. For microstructural measures, the mean measure within the fiber pathway is the most widely used. Other summary statistics such as the median, maximum and minimum have also been employed (Boshkovski et al., 2020b; Zhang et al., 2018a; 2018b). A summary statistic can be obtained in several ways according to how microstructural measures are computed along fiber pathways (as described in Section 5.1). It can be computed within a binary mask defining a fiber pathway in a microstructure image (e.g. the mean FA within the mask) (Ciccarelli et al., 2003; Heiervang et al., 2006; Jolly et al., 2021; Kunimatsu et al., 2004; Voineskos et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2021). It can also be computed by averaging microstructural measures sampled along each point of the streamlines (Gong et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2006; Olszewski et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018a; 2019). The choice of the best summary statistic for data measured within a fiber pathway is still open. For example, compared to the mean statistic, studies have shown that the median can be more robust against outliers and does not rely on the normality assumption for the distribution of the microstructure parameter along a streamline (Boshkovski et al., 2020b; Zhang et al., 2018b). One study has suggested that the maxima and minima are more discriminative than the mean value in machine-learning-based disease classification (Zhang et al., 2018a).

The second strategy to quantify an individual fiber pathway is to measure the distribution of the microstructural measures along the fiber pathway. This can enable the study of the tissue microstructure in local regions along the fiber pathway. This approach requires definition of a coordinate system, sampling framework, or surface-based representation to define how to sample the microstructural data of interest (Bells et al., 2011a; Chen et al., 2016b; Colby et al., 2012b; Corouge et al., 2006; Goodlett et al., 2009; Irimia et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2005; O’Donnell et al., 2009; Yeatman et al., 2012; Yeh, 2020). Most often, data are averaged across corresponding points along each streamline in the pathway, such that data can be analyzed (e.g., an along-tract or along-pathway plot) versus streamline arc length or other parameterization (Colby et al., 2012b; Corouge et al., 2006; Yeatman et al., 2012). Other approaches fit a medial surface representation to the pathway, such that sampled data can be represented in two dimensions and can be analyzed not only along the pathway but also across its cross-section (Chen et al., 2016b; Qiu et al., 2010; Yushkevich et al., 2009).

5.3. Quantitative measures using filtering techniques

The so called filtering methods discussed in Section 3.3 can also be used to perform “microstructure-informed” tractography with the aim to extract quantitative measures of white matter fiber pathways and reduce potential bias in the estimation of connectivity. Assuming that the microstructure properties corresponding to a single streamline remain constant along its path, these methods assign a specific microstructural property to each reconstructed pathway. The underling assumption comes from the fact that a streamline reconstructed from tractography cannot represent a single axon, but rather a group of axons following the same trajectory, and thus we can suppose that on average the microstructure properties the magnetic resonance signal is sensitive to at achievable resolution remain constant. While in its original implementation SIFT (Smith et al., 2013) provides only the NOS adjusted based on voxel-wise spherical deconvolution, its evolution SIFT2 (Smith et al., 2015b) optimizes per-streamline cross-section multipliers to match a whole-brain tractogram to fixel-wise fiber densities and thus provides a value for each streamline that can be used (for example) to define the edge weights of the connectome. Similarly, LiFE (Pestilli et al., 2014), COMMIT (Daducci et al., 2013; 2014; Schomburg and Hohage, 2019), COMMIT2 (Schiavi et al., 2020a) and COMMIT2tree (Ocampo-Pineda et al., 2021) deconvolve the measured dMRI signal on the streamlines and assign a single contribution, or “weight”, to each one of them using classical multi-compartment models (Panagiotaki et al., 2012). These methods have been used to investigate properties of healthy and pathological brains, showing better performance than the standard NOS (Schiavi et al., 2020b; Smith et al., 2015a; Yeatman et al., 2014b). In particular, because of their flexible implementations, COMMIT, COMMIT2 and COMMIT2tree allow complementing tractography with biophysical models of the tissue microstructure and, thus, enable one to access more quantitative and biologically informative features of individual bundles, such as average axon diameter (Barakovic et al., 2018), myelin content (Schiavi et al., 2019) and bundle-specific T2 (Barakovic et al., 2021b).

5.4. Tract-specific analysis using statistical or machine learning techniques

Once a quantitative measure has been extracted for individual fiber pathways, several options exist for tract-specific analysis, which may be hypothesis-driven using statistical analysis or data-driven using machine learning. These methods may rely on a summary statistic per tract, or analyze data along a tract.

One widely used analysis is based on a hypothesis-driven strategy to assess if there are statistical differences of tract(s)-of-interest between groups (e.g., between health and disease, or between different subtypes of a disease). Usually, given a quantitative measure of interest, a selected summary statistic (e.g. mean of the chosen microstructural measure) is extracted from the tract(s)-of-interest and is used to compute the level of group differences (e.g., the p-value) using statistical group-wise comparison methods such as Student’s t-test, ANOVA, or other more advanced statistical analysis methods (Habeck and Stern, 2010; Martí-Juan et al., 2020; Ombao et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018b). Another hypothesis-driven analysis uses a regression model (e.g., a generalized linear model (Dobson and Barnett, 2018) or support vector regression (Zhang and O’Donnell, 2020)) to assess correlation of the tract quantitative measurement and a behavioral or a disease symptom score. Such analyses have been applied to study, e.g., how white matter fiber tracts are affected in individuals with different disease severity (Cha et al., 2015; Chiang et al., 2016; Price et al., 2007), how tracts relate to cognitive and socio-emotional function (Zekelman et al., 2021), and how tracts are developing during human neurodevelopment and aging (Gertheiss et al., 2013; Hasan et al., 2009a; Michielse et al., 2010). One important point to note is that correction for multiple comparisons is needed if there are multiple tracts and/or multiple quantitative measurements analyzed. Commonly used multiple comparison correction methods include false discovery rate (FDR) (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) and Bonferroni (Holm, 1979) methods. However, it is important to highlight that such multiple comparison correction methods, which assume independence across data samples, can be overly conservative when applied to tests performed on multiple tracts and/or quantitative measurements that are not independent. For example, MD and FA are not mutually mathematically orthogonal measures (Ennis and Kindlmann, 2006).

Another tract-specific analysis strategy is data-driven and uses machine learning techniques to perform tasks such as disease classification and prediction (Deng et al., 2019; O’Dwyer et al., 2012; Payabvash et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018a), as well as prediction of behavioral measures and traits (Seguin et al., 2020a; Tian et al., 2021). In machine learning analysis, the quantitative measures computed from individual fiber pathways are treated as feature descriptors, which are input to a machine learning algorithm (e.g., a support vector machine) to train a model from a set of training samples with known information (e.g., labels such as disease or healthy control). Then the trained model can be used to predict new samples. Unlike statistical analysis methods that usually aim to find white matter structures with statistical group differences, the machine-learning-based methods aim to offer predictive relevance. This can be advantageous in situations where the within-group heterogeneity is large (e.g., in psychiatric diseases) and thus a statistical group comparison, which essentially compares the “average patient” to the “average control,” is not informative. Another advantage of machine learning is that it can be easily applied to multimodal data. For example, the combination of structural and functional connectivity measures has been shown to increase predictive power (Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2016).

Instead of using a single scalar value to summarize the entire pathway, many methods perform along-tract analysis to investigate the distribution of the microstructural measures along the fiber pathway (variously called “tractometry,” “profilometry,” and “tract-based morphometry”) (Bells et al., 2011b; O’Donnell et al., 2009; Yeatman et al., 2012). Along-tract analysis enables the study of local regions along the tract. After mapping microstructural measures along each point of the streamlines along the fiber pathway, a widely used strategy is to analyze data along the tract profile. One popular approach is to average data across corresponding points along each streamline in the pathway and leverage a prototype, core, or mean streamline to enable statistical analysis comparing subjects or groups (Colby et al., 2012b; Wang et al., 2016; Yeatman et al., 2012). Other approaches can employ streamlines of the entire tract in the statistical analyses (Chandio et al., 2020b). Additional studies have analyzed tracts represented as surfaces (Chen et al., 2016b; Qiu et al., 2010; Yushkevich et al., 2009) or performed data reduction techniques to reduce the dimensionality of the point-wise measurements along tracts (Ceschin et al., 2015; Chamberland et al., 2019; Geeraert et al., 2020). Several studies have shown that along-tract analysis can be more sensitive to detect differences that are not apparent in the mean value within the tract (Colby et al., 2012b; O’Donnell et al., 2009; St-Jean et al., 2019).

5.5. Construction of a structural connectivity matrix

Quantitative measures extracted for individual fiber pathways can also be used to construct a structural connectivity matrix to map the whole-brain network of structural connectivity between all pairs of gray matter regions (Hagmann et al., 2008a; Sporns et al., 2005). This approach is motivated by a general shift of focus away from the roles of isolated regions towards understanding the brain as a networked system (Barch et al., 2016; Friston, 2002). Construction of the connectivity matrix has been described in several reviews (Sotiropoulos et al., 2016; Yeh et al., 2020) and includes two major steps. First, parcellation of the whole-brain tractogram is needed to compute all possible fiber pathways in the brain, i.e., white matter parcels connecting all pairs of gray matter regions (as described in Section 4.2). Then, a metric of “connectivity” is needed to define quantitative edge weights in the connectivity matrix (see Fig. 1(e) for a graphic illustration). This is usually done by computing a scalar value for each white matter parcel (as described in Section 5.2). The most popular scalar value for connectivity matrix analysis is the NOS (Hagmann et al., 2008b; Ingalhalikar et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2016; Sporns et al., 2005; van Dellen et al., 2018), where higher values are considered to indicate stronger connectivity between pairs of gray matter regions. Other scalar values that are generally interpreted as measures of connectivity “strength” include microstructural measures, e.g., FA (Bathelt et al., 2017) and R1 (Boshkovski et al., 2020a). For scalar values that are interpreted as inversely related to connectivity “strength,” such as RD, MD, or maps reflecting extracellular or isotropic/free water components of the signal, a transformation of the connectivity matrix may be performed using the reciprocal or the log function prior to any subsequent connectivity analysis (Fornito et al., 2016).

While the construction of the connectivity matrix is straightforward, multiple factors that need careful consideration have been pointed out by researchers. Selection of a gray matter parcellation scheme (as described in Section 4.2) is the first essential consideration when constructing a structural connectivity matrix, and it has been shown to be highly consequential in connectome analysis (de Reus and Van den Heuvel, 2013; Yeh et al., 2020; Zalesky et al., 2012). Myriad components of the processing pipeline can also influence the resulting connectome matrix data, even down to the level of detail of the mechanism by which streamlines are assigned to those parcels (Yeh et al., 2019a). In addition, connectomes are usually post-processed to reduce potential bias in the estimation of graph measures. This step is typically done by simply thresholding according to some rule or to reach a predefined density, or using filtering techniques described in Section 5.3. Selection of tractography filtering strategies is important and has been shown to affect the analysis of the topology of brain networks (Civier et al., 2019; Frigo et al., 2020; Yeh et al., 2016a) and affect sensitivity and specificity when analyzing the connectomes (Zalesky et al., 2016a). Moreover, as concluded in several studies (Bastiani et al., 2012; Qi et al., 2015; Yeh et al., 2016a), several other factors (such as q-space sampling schemes, fiber orientation models, and tractography algorithms) that are not specifically reviewed in our paper, have also been shown to affect most network measures derived from the connectivity matrix.

5.6. Graph theoretical measures and advanced structural connectome measurements

A structural connectivity matrix defines a network (or graph) of whole-brain anatomical connectivity, where the nodes are typically gray matter regions or ROIs, and the edges represent the connectivity between these regions (Hagmann et al., 2008a; Sporns et al., 2005) (Fig. 4a). The disciplines of graph theory and network science provide a framework to quantify network properties of brain connectivity (Rubinov and Sporns, 2010) and investigate whole-brain models of structural wiring (Betzel et al., 2016). Over the last two decades, the study of the brain as a network has become increasingly popular in the neuroscience and neuroimaging communities, giving rise to the new fields of connectomics and network neuroscience (Bassett and Sporns, 2017; Fornito et al., 2013; 2015; 2016).

Fig. 4.

Graph theoretical analysis of the human connectome. (a) Network diagram of structural connectivity, where nodes represent gray matter ROIs and connections depict white matter fiber bundles. (b) Schematics of key graph theory concepts applied to the analysis of structural connectivity. The thickness of connections indicates the strength of structural connectivity between two ROIs (e.g., NOS or integrated FA). Region-level graph measures such as degree, strength, and centrality identify ROI B as an important hub in the network. At the mesocale, two modules or communities are observed. Intra-module connectivity is dense and inter-module connectivity in sparse. At the global scale, communication paths delineate multi-step sequences linking anatomically unconnected ROIs. Two possible paths connecting ROIs A and C are highlighted in green (shortest path) and orange (alternative path).

A daunting number of graph theoretical measures have been proposed to study the network properties of the brain’s connectome (Bullmore and Sporns, 2009b; Iturria-Medina et al., 2008; Rubinov and Sporns, 2010). The choice of which measures to focus on is dependent on the research questions and hypotheses at hand. Graph measures can be classified based on their resolution or scope—from local measures that quantify properties of individual ROIs (nodes), to mesoscale measures describing clusters of interconnected ROIs, to global measures that describe whole-brain connectivity properties (Betzel and Bassett, 2017; Fornito et al., 2016) such as network communication in the brain (Graham et al., 2020) (Fig. 4b). In the following paragraphs, we give examples of these popular graph measures that quantify aspects of brain networks at each level, from local to global.

At the local level, node centrality measures provide a useful characterization of the integrative importance of individual brain regions (Sporns et al., 2007). Degree and strength are the simplest and most popular node centralities, quantifying, respectively, the number of connections and the sum of connection weights of individual regions (see Oldham et al., 2019 for a review on advanced node centrality measures). Centrality measures find particular utility in identifying hub regions that may play a central role in integrative brain function (van den Heuvel and Sporns, 2013). Indeed, hubs identified with these measures have been found to entail high metabolic expenditures and be disproportionately implicated in brain disorders (Crossley et al., 2014; Fornito et al., 2015).