Abstract

The present study examined the association between anxiety, stigma, social support and intention to use illicit drugs, and the moderating role of social support on the association between anxiety / stigma and intention to use illicit drugs among 450 Chinese HIV-positive MSM. Findings show that controlling for significant background variables, self-stigma and anxiety were positively associated with intention to use illicit drugs, while social support was negatively associated with intention to use illicit drugs. A significant moderation effect of social support was also observed, that the negative association between self-stigma / anxiety and intention to use illicit drugs was only significant among participants with lower levels of social support. Findings highlight the importance of reducing self-stigma and anxiety, and promoting social support in drug use prevention for HIV-positive MSM.

Keywords: social support, intention to use illicit drugs, anxiety, stigma, men who have sex with men

Introduction

HIV-positive MSM as an at-risk group for illicit drug use

The HIV epidemic continues to expand among men who have sex with men (MSM) in China. The prevalence of HIV among MSM had increased from 0.9% in 2003 to 7.8% in 2014 (1). Among the 654,000 people living with HIV (PLWH) in China, more than a quarter (27.5%) of which were MSM as of 2016 (2). Studies have revealed that there are higher rates of risky health behaviors, especially substance abuse and dependence, among MSM (3, 4). For example, one recent study from the United States reported that gay and bisexual men were 1.4-1.9 times more likely to meet criteria for a substance use disorder (5). Illicit drug use is disproportionally high among MSM with HIV (6). For example, it has been found that the lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders was higher among HIV-positive MSM (42%) than HIV-negative MSM (27%) (7). A recent study among HIV-positive gay/ bisexual men reported that over half of them (53%) have used illicit drugs in the past 3 months (8). Illicit drug use is a significant health issue for HIV-positive MSM as it is associated with significant health impairments such as damage to the immune system and effects of medications decreased adherence to HIV medications, and worsen psychosocial and cognition functioning (9, 10). It also facilitates maladaptive behaviors that weaken immune system and worsen the conditions of HIV (11).

Self-stigma as a risk factor of illicit drug use

HIV has been considered as one of the most stigmatized health conditions (12, 13). In the context of HIV, stigma has been shown to adversely affect quality of life, medication adherence, coping and mental health (14–20). It also serves as an important risk factor of illicit drug use among MSM (21). HIV-positive MSM are facing dual stigmas of being MSM and HIV-positive, which further heighten their vulnerability (22, 23). Dual stigma poses significant threat on both physical health and psychological well-being among HIV-positive MSM. A study revealed that stigma associated with having HIV and being an MSM acted as significant barriers for treatment seeking (24), and significant risk factors for risky sexual behaviors among HIV-positive MSM (25). Stigma and discrimination can increase illicit drug use, through worsening mental health and facilitating adoption of avoidant coping strategies to cope with stress or suppress negative feelings (26, 27). One 21-day study among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men found direct effects of stigma on later emotion dysregulation and increased likelihood of stimulant use (28).

Anxiety as a risk factor of illicit drug use

Living with HIV is intensely stressful. Studies have indicated that HIV-positive men presented higher level of anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric conditions than HIV-negative men (29). HIV-positive MSM also suffer from significant minority stress due to their same sex behaviours, which further increases anxiety. One study among HIV-positive MSM reported that more than 47% of participants met diagnostic criteria for any anxiety disorder (8). Anxiety has been found to increase the risk of illicit drug use across various populations, including MSM (21) and primary care patients (30). One recent study has also revealed that having anxiety or depression was associated with sexualized drug use among HIV-positive MSM (31). It is conjectured that HIV-positive MSM may use illicit drugs as a way to cope with their anxiety, in addition to their life challenges.

The buffering role of social support in HIV

The beneficial role of social support on health has been widely demonstrated in the literature (32, 33). Social support can serve as both problem-focused and emotional-focused coping strategy by providing information or tangible assistance to solve a problem, or regulating emotions that arise from stressful events. Studies among HIV-positive populations found that supportive others can act as collaborators to help with information seeking or avoiding, provide instrumental support, contribute to skill development, give acceptance or ventilation, and facilitate perspective shifts, which help patients manage uncertainty (34, 35). Other studies also reported that social support is associated with better psychological adjustment, emotional well-being and longevity, and lower levels of illicit drug use among HIV-positive individuals (36, 37). Lack of social support has also found to be an important risk factor for illicit drug use across various populations, including MSM (38). Social support can play a vital role in maintaining HIV-positive MSM’s physical health and emotional and mental well-being, which in turn, reduces illicit drug use tendency.

Social support can also provide a buffer against adverse life events and negative impacts of stressors, leading to positive outcomes (33). Numerous studies indicated that social support plays a buffering role from health problems or risky behaviors (39, 40). In the context of HIV, studies have shown that social support buffered the association between polydrug use and depression (41), and between self-stigma and HIV symptoms among people living with HIV (42) .

The present study

MSM and HIV-positive are the two main groups at risk of illicit drug use. Few studies have examined the drug use among HIV-positive MSM in China. We only identified one qualitative study that has suggested a positive association between HIV stigma and substance use among HIV–infected MSM (43). The present study examined the association between anxiety, self-stigma, social support, and illicit drug use intention among HIV-positive MSM. The moderating role of social support on the association between anxiety / self-stigma and illicit drug use intention was also explored. It is hypothesized that self-stigma and anxiety would be positively associated with drug use intention, while social support would be negatively associated with drug use intention among HIV-positive MSM. It is further hypothesized that social support would weaken the relationship between anxiety / self-stigma and drug use intention among HIV-positive MSM.

Methods

Study population and procedure

Participants of the present study were cisgender HIV-positive MSM who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 18 years old or above, (2) men with Chinese nationality, (3) reported having had sex with at least one man in the past six months, and (4) diagnosed as HIV positive for at least three months when the survey was conducted.

Participants were recruited from a local non-governmental organization (NGO) serving MSM from Chengdu, China. The NGO was one of the largest organizations providing HIV prevention and care services to HIV-positive MSM in Chengdu. It maintained a list of HIV-positive MSM who have agreed to be contacted for research purposes. The NGO staff contacted prospective participants, briefed them about the study procedure, and invited them to participate in the study after confirming their eligibility. The study was also publicized by the NGO through posters, leaflets, and social media. Those who agreed to take part in the study were invited to meet the research assistant at the NGO. They were assured that they could quit the interview anytime they wanted and their refusal would not affect their right to use any services the NGO offered. After obtaining the participants’ written informed consent, the research assistant conducted anonymous face-to-face interviews using a pilot-tested and structured questionnaire in a room with ensured privacy. Upon completion of the interview, the participants were provided with an honorarium of RMB 50 (about USD 7.5) to compensate their time and travel cost. A total of 450 HIV-positive MSM were successfully contacted by the fieldworkers, among which 415 (92.2%) completed the interview. Ethical approval was obtained from the Survey and Behavioral Research Ethics, the Chinese University of Hong Kong. .

Measures

Sociodemographic variables, including age, education, and marital status were measured. HIV- and health-related information, including duration of HIV diagnosis and HIV stage, and self-perceived health status (from 1 = very poor to 5 = very good) was also collected. Participants were also asked to report whether they have used illicit drugs in their lifetime.

Intention to use illicit drugs was assessed by asking the participant “How likely will you use any illicit drugs (e.g. heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, ketamine, and RUSH) in the next 6 months?” The response was rated at a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = very unlikely to 5 = very likely), that a higher score indicated higher intention to use illicit drugs in the future.

Self-stigma was assessed with the 9-item Self-Stigma Scale-Short Form (SSS-S), which assesses affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions of HIV-related self-stigma as applicable across stigmatized groups. The Chinese version has been validated (44). Participants rated the extent to which they endorsed each item rate on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Sample items included, “I am afraid that others know that I have HIV” and “I will avoid interacting with others because I have HIV.” Higher scores indicated a stronger sense of self-stigma. The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.89 in the present study.

Anxiety was measured by the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)(45). The Chinese version has been validated (46). The participants were asked to rate the frequency of anxiety symptoms on a 4-point scale (0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day). Higher scores indicated a higher level of anxiety. The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.93 in the present study.

Social Support was measured by adapting two items that have been used to measure social support in previous studies (47). The two items measure the level of emotional and material support the participants received. Participants were asked: (1) “How often do you receive emotional support from family/friends/colleagues when you need it?” and (2) “How much do you receive material support (e.g. financial help) from family/friends/colleagues when you need it?” Responses were recorded on scales that ranged from 0 (‘none’) to 10 (‘a lot’). The responses of the two items were summed up to construct the index of social support. Higher score indicated higher level of social support. The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.90 in the present study.

Analytic strategy

All the analyses were performed using Stata 14.1. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to show the associations between the major variables. Hierarchical regression was used to examine the association between anxiety / self-stigma and illicit drug use intention, with social support as a potential moderator in such associations. We first investigated the relationship between past drug use, multiple socio-demographic and HIV- and health-related variables, and illicit drug use intention using OLS regression. Next, we examined the main effects of self-stigma and social support on illicit drug use intention, after adjusting for background variables. Notably, we predicted intention to use when controlling for past use, which made the analysis more rigorous. In order to examine whether the relationship between self-stigma and illicit drug use intention was moderated by social support, we computed the two-way interaction term between self-stigma and social support and added it to the model. Such analyses were repeated for anxiety as an alternate independent variable so as to ascertain the effect of anxiety and its interaction with social support on illicit drug use intention. Considering a bidirectional relationship between psychosocial variables and drug use may exist, it would be inappropriate to examine the association between the psychosocial variables and past illicit drug use behaviors using cross-sectional data. Thus, only intention to use illicit drugs in the future was investigated in the study. Both unstandardized and standardized coefficients with 95% confidence intervals were reported. A p value of .05 was set as the level of statistical significance.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics are displayed in Tables 1. The mean age of the 415 participants was 30.2 (SD=7.57). About 90% of the participants had obtained a high school education or above. A majority of the participants surveyed were single (65.1%). For the HIV-related characteristics, more than 80% of the participants were diagnosed with HIV for more than 6 months. Majority (89%) of the participants were at the asymptomatic stage. More than 90% of the participants perceived their health as fair, good, or very good. About 1/6 of the participants had used illicit drugs in their lifetime. As for the intention to use illicit drugs, 6.0% of the participants were neutral about their intention, and 3.1% and 2.2% of the participants indicated that they were likely or very likely to use illicit drugs in the next 6 months, respectively.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the participants (n = 415).

| Variable | N / Mean (% / SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 30.2 | (7.57) |

| Level of education | ||

| Middle school or below | 44 | (10.60) |

| High school or above | 371 | (89.40) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 270 | (65.06) |

| Married/cohabited/divorced/widowed | 145 | (34.94) |

| HIV-related characteristics | ||

| Duration of HIV diagnosis | ||

| <6 months | 77 | (18.55) |

| ≥6 months | 338 | (81.45) |

| HIV stage | ||

| Asymptomatic | 369 | (88.92) |

| AIDS | 46 | (11.08) |

| Self-perceived health | ||

| Very poor/poor | 31 | (7.47) |

| Fair/good/very good | 384 | (92.53) |

| Illicit drug use | ||

| Lifetime illicit drug use | ||

| Yes | 68 | (16.40) |

| No | 347 | (83.60) |

| Intention to use illicit drugs | ||

| Very unlikely | 297 | (71.57) |

| Unlikely | 71 | (17.11) |

| Neutral | 25 | (6.02) |

| Likely | 13 | (3.13) |

| Very likely | 9 | (2.17) |

Correlations among variables

Table 2 presents the pairwise correlations among all the variables. The results showed that both self-stigma (r = 0.17, p <0.01) and anxiety (r = 0.17, p <0.01) were positively associated with intention to use illicit drugs, while social support was negatively associated with illicit drug use intention (r = −0.16, p < 0.01). Most of the background variables were not associated with intention to use illicit drugs, except for lifetime illicit drug use (r = 0.44, p < 0.01). Since all the correlation coefficients were below 0.5, the multicollinearity issue was of modest concern.

Table 2.

Correlation between variables (N = 415)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Intention to use illicit drugs | - | ||||||||||

| 2 Self-stigma | 0.17** | - | |||||||||

| 3 Anxiety | 0.17** | 0.54** | - | ||||||||

| 4 Social support | −0.16** | −0.21** | −0.22** | - | |||||||

| 5 Age | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.09 | - | ||||||

| 6 Education | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.17** | - | |||||

| 7 Marital status | −0.09 | −0.12** | −0.10* | 0.12** | 0.27** | −0.14* | - | ||||

| 8 Diagnosed year | 0.07 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.03 | - | |||

| 9 HIV stage | −0.09 | −0.09 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.13** | −0.08 | 0.00 | 0.01 | - | ||

| 10 Self-perceived health | 0.02 | −0.11* | −0.22** | 0.13** | −0.09 | 0.11* | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.13** | - | |

| 11 Lifetime illicit drug use | 0.44** | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.08 | 0.07 | −0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | - |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

Regression results

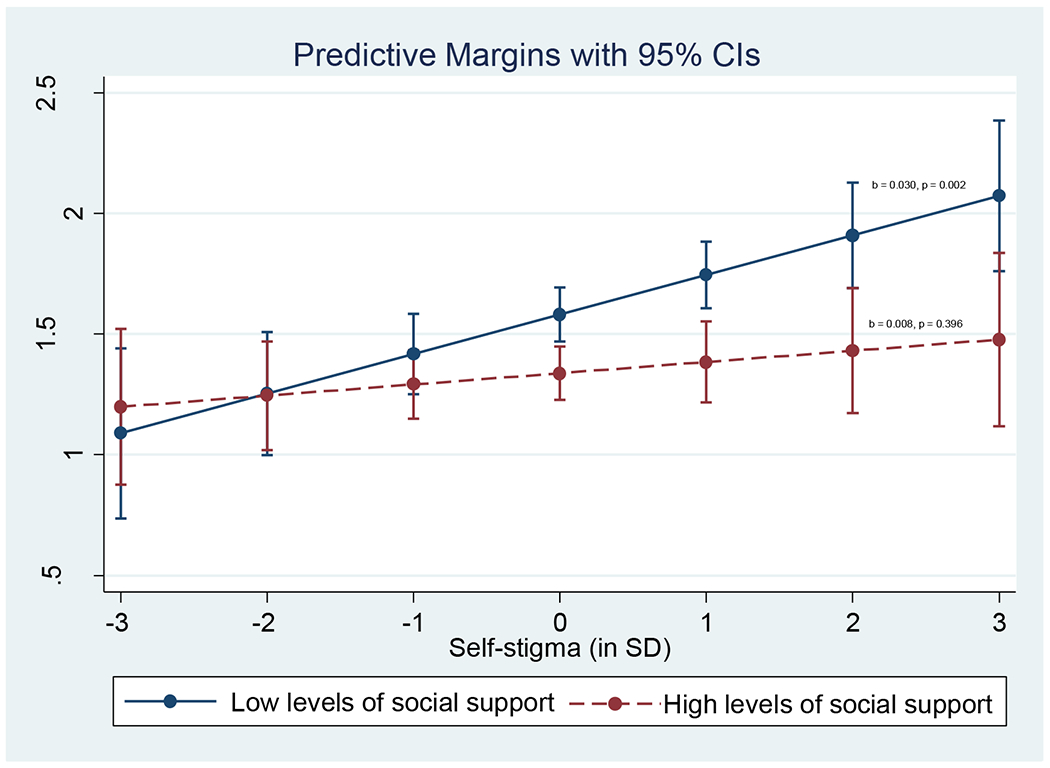

Table 3 shows the hierarchical regression analysis of self-stigma and social support on intention to use illicit drugs. First, Block 1 assessed the relationship between socio-demographic and health-related variables and illicit drug use intention. The only significant variable was lifetime illicit drug use (β = 0.44, CI = [0.84, 1.27], p < 0.001). Consistent with our hypothesis, Block 2 showed that after adjusting for all background variables, self-stigma was positively associated with illicit drug use intention (β = 0.12, CI = [0.00, 0.03], p < 0.05), while social support was negatively associated with intention to use illicit drugs (β = −0.14, CI = [−0.04, −0.01], p < 0.01). Block 3 further investigated the interaction between self-stigma and social support in explaining the variance in intention to use illicit drugs among HIV-positive MSM. A negative interaction emerged, though it did not reach the .05 significance level (β = −0.07, CI = [−0.00, 0.00], p = 0.09). Results of simple slopes analysis (Figure 1) showed that the negative association between self-stigma and intention to use drugs was significant among participants with lower levels of social support, but not among those with higher levels of social support.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analysis of self-stigma and social support on intention to use illicit drugs (N = 415)

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | 95%CI | B | β | 95%CI | B | β | 95%CI | |

| Age | −0.00 | −0.02 | [−0.01,0.01] | −0.01 | −0.05 | [−0.02,0.01] | −0.01 | −0.06 | [−0.02,0.01] |

| Education | |||||||||

| Middle school or below | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| High school or above | −0.03 | −0.01 | [−0.29,0.23] | −0.06 | −0.02 | [−0.32,0.20] | −0.05 | −0.02 | [−0.31,0.20] |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single/divorced | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Married/cohabited | −0.12 | −0.06 | [−0.28,0.07] | −0.03 | −0.02 | [−0.21,0.14] | −0.03 | −0.02 | [−0.20,0.15] |

| HIV diagnose year | |||||||||

| <6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| ≥6 months | 0.17 | 0.07 | [−0.03,0.40] | 0.22* | 0.09* | [0.02,0.45] | 0.22* | 0.10* | [0.03,0.45] |

| HIV stage | |||||||||

| Asymptomatic | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| AIDS | −0.27 | −0.09 | [−0.51,0.00] | −0.21 | −0.07 | [−0.45,0.05] | −0.21 | −0.07 | [−0.44,0.06] |

| Self-perceived health | |||||||||

| Very poor/poor | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Fair/good/very good | 0.00 | 0.00 | [−0.30,0.30] | 0.11 | 0.03 | [−0.19,0.41] | 0.13 | 0.04 | [−0.17,0.43] |

| Lifetime illicit drug use | |||||||||

| No | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.06*** | 0.44*** | [0.84,1.27] | 1.03*** | 0.42*** | [0.82,1.23] | 1.03*** | 0.42*** | [0.82,1.24] |

| Self-stigma | 0.02* | 0.12* | [0.00,0.03] | 0.02* | 0.12* | [0.00,0.03] | |||

| Social support | −0.02** | −0.14** | [−0.04,−0.01] | −0.02** | −0.13** | [−0.04,−0.01] | |||

| Self-stigma × Social support | −0.00# | −0.07# | [−0.00,0.00] | ||||||

| DF | 9 | 11 | 12 | ||||||

| F | 12.56*** | 12.36*** | 12.50*** | ||||||

| R square | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.26 | ||||||

95% confidence intervals in brackets

p < 0.1,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Figure 1.

Interaction between self-stigma and social support on intention to use illicit drugs (N = 415)

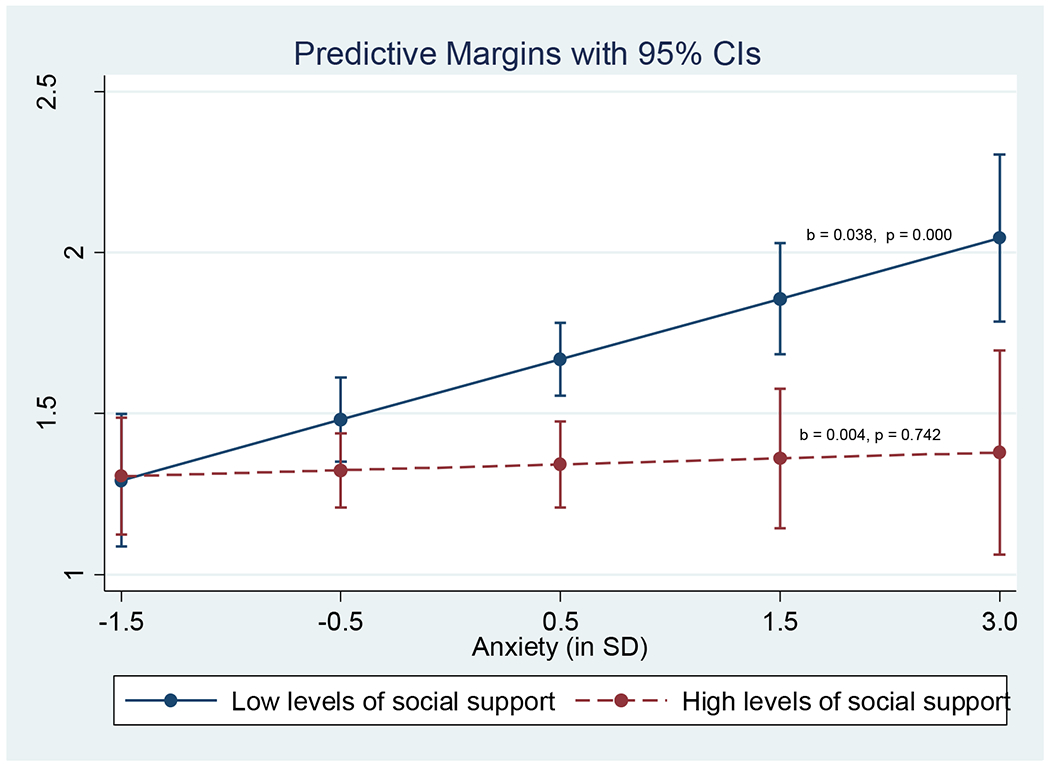

Similarly, Table 4 presents the results of the effects of anxiety and social support, as well as their interaction in explaining the variance in illicit drug use intention. Results in Block 2 showed a positive relationship between anxiety and intention to use illicit drugs after controlling for background characteristics (β = 0.12, CI = [0.01, 0.04], p < 0.01), while social support was negatively associated with intention to use illicit drugs (β = −0.13, CI = [−0.04, −0.01], p < 0.01). In Block 3, a significant two-way interaction emerged between anxiety and social support (β = −0.11, CI = [−0.01, 0.00], p < 0.05). Results of the simple slopes analysis (Figure 2) demonstrated that negative relationship between anxiety and intention to use illicit drugs was only significant among the participants with lower levels of social support, whereas not significant among those with higher levels of social support.

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression analysis of anxiety and social support on intention to use illicit drugs (N = 415)

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Β | 95%CI | B | β | 95%CI | B | β | 95%CI | |

| Age | −0.00 | −0.02 | [−0.01,0.01] | −0.00 | −0.03 | [−0.01,0.01] | −0.00 | −0.03 | [−0.01,0.01] |

| Education | |||||||||

| Middle school or below | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| High school or above | −0.03 | −0.01 | [−0.29,0.23] | −0.04 | −0.01 | [−0.30,0.22] | −0.04 | −0.01 | [−0.29,0.22] |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single/divorced | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Married/cohabited | −0.12 | −0.06 | [−0.28,0.07] | −0.05 | −0.03 | [−0.22,0.13] | −0.06 | −0.03 | [−0.22,0.12] |

| HIV diagnose year | |||||||||

| <6 months | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| ≥6 months | 0.17 | 0.07 | [−0.03,0.40] | 0.22* | 0.09* | [0.03,0.45] | 0.24* | 0.10* | [0.05,0.47] |

| HIV stage | |||||||||

| Asymptomatic HIV infection | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| AIDS | −0.27 | −0.09 | [−0.51,0.00] | −0.25* | −0.09* | [−0.49,0.01] | −0.25* | −0.09 | [−0.48,0.01] |

| Self-perceived health | |||||||||

| Very poor/poor | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Fair/good/very good | 0.00 | 0.00 | [−0.30,0.30] | 0.15 | 0.04 | [−0.15,0.46] | 0.19 | 0.06 | [−0.11,0.50] |

| Lifetime illicit drug use | |||||||||

| No | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.06*** | 0.44*** | [0.84,1.27] | 1.03*** | 0.42*** | [0.81,1.23] | 1.04*** | 0.42*** | [0.82,1.23] |

| Anxiety | 0.02** | 0.12** | [0.01,0.04] | 0.02* | 0.11* | [0.01,0.04] | |||

| Social support | −0.02** | −0.13** | [−0.04,−0.01] | −0.02* | −0.13** | [−0.04,−0.01] | |||

| Anxiety × Social support | −0.00* | −0.11* | [−0.01,−0.00] | ||||||

| DF | 9 | 11 | 12 | ||||||

| F | 12.56*** | 11.57*** | 12.05*** | ||||||

| R square | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.26 | ||||||

95% confidence intervals in brackets

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Figure 2.

Interaction between anxiety and social support on intention to use illicit drugs (N = 415)

Discussion

Illicit drug use is a significant health issue for HIV-positive MSM as it can adversely affect their health and medication regimes. Currently, there is a dearth of studies exploring the issue of illicit drug use among HIV-positive MSM in China. The present study aimed to fill up this important gap by examining the role of self-stigma, anxiety, and social support on illicit drug use intention among HIV-positive MSM.

In the current sample of HIV-positive MSM, 16.4% reported that they have ever used illicit drugs, and 5.2% indicated that they had the intention to use illicit drugs in the future. The figure is much lower than those reported in other countries (7, 8). Given the intense level of stigma associated with illicit drug use in China (48, 49), it would be possible that the level of illicit drug use was underreported in the current study. Despite this, the issue of illicit drug use among HIV-positive MSM remains at a worrying level that warrants public health concern. Given that an individual who possess an intention to perform a behavior will be highly like to act in the future, interventions to prevent future illicit drug use behaviors among this at-risk group are highly warranted.

The present study sought to explore factors associated with illicit drug use intention among HIV-positive MSM. First of all, findings revealed that having ever used illicit drugs is the most significant factor for illicit drug use intention. Findings were in line with the proposition that past behaviors affect future behavior indirectly through conscious intentions to behave (50). It can be conjectured that individuals who have frequently performed a behavior in the past are more likely to form favourable attitude towards the behavior, or to believe that the behavior is under one’s control, resulting to more favourable intentions for future action. They may be more likely to generate intentions that are consistent to their previous acts (50).

The present study revealed that individuals with higher level of anxiety report higher intention to use illicit drugs in the future. Findings support the extant literature which documents the co-occurrence of anxiety and illicit drug use disorders (51). It also concurs with the studies that anxiety was associated with increases in illicit drug-related harms, or higher relapse rates following illicit drug abuse treatment (21, 30). Individuals who are susceptible to anxiety symptoms might be more likely to turn to illicit drug use to cope with the unpleasant feelings. Anxiety may impair decision-making capacities and therefore, leading to higher tendency to use illicit drugs in the future.

Stigma is a powerful social label that discredits one’s image and may lead to self-marginalization and isolation (52). The present study revealed that individuals with higher level of self-stigma showed higher level of intention to use illicit drugs in the future. Findings were in line with the previous studies that self-stigma was associated with health compromising behaviors among individuals living with HIV (14–20). Self-stigma might increase stress, or inhibit individuals from disclosing their HIV infection status, establishing interpersonal relationships, or obtaining social networks and support (12, 20). The increase in psychological distress and decrease in social resources might increase their tendency to use illicit drugs.

There has been extensive evidence that social support is associated with better health outcomes across the lifespan. Findings of the present study indicate that perceived support from others may have a critical role in protecting against illicit drug use. A good support network helps individuals with HIV develop coping skills, which can lead to better decision-making and self-advocacy skills (34, 35). Patients with higher level of support might therefore be more likely to receive emotional, informational, or instrumental resources that could help them cope with adversities or addictions. It may also improve their level of self-worth and subsequently increase their motivation to conform to positive behaviors.

The ‘buffering’ hypothesis proposes that social support prevent negative outcomes by helping the individual materially and emotionally at the time of major life stresses (33). In the present study, social support was found to be a significant moderator on the association between anxiety / self-stigma and illicit drug use intention. Further investigations found that the negative effect of anxiety / self-stigma was only evident among patients with lower level of social support. It may be possible that for patients with higher level of social support, the material help, information, emotional support or psychological reassurance they received help them avoid deterioration from the deleterious effects of anxiety / self-stigma. The belief that others will provide necessary support if needed could also help patients reappraise the potential harm posed by the negative events, or improve their capability to cope with the demands. This would prevent them from perceiving the event as negative, thereby mitigating the negative effects of anxiety / self-stigma.

Implications for practice

Findings obtained from the present study have important implications for public health interventions to reduce illicit drug use among HIV-positive MSM. Findings provide clear evidence that issues of illicit drug use should be assessed and addressed by health care professionals working for HIV-positive MSM. Such programs would be critical to improving health of HIV-positive MSM and consequently decreasing their level of HIV transmissions. First of all, the important role of past behaviors on illicit drug use documented in the present study suggest that HIV-positive MSM who have previously abused illicit drugs should be given the priority for health interventions. It is also important to break the linkage between well-established behaviors and future intentions. It has been suggested that changing frequently practised behaviors would require cognizant decision making, and development of concrete and explicit plans to implement a new behavior (50). Ensuring the new behavior would result in immediate favourable outcomes would also help increase one’s intention to change.

Second, findings also suggest that interventions to reduce illicit drug use among HIV-positive MSM should seek to reduce their self-stigma and anxiety symptoms. This is particularly important given that a high level of self-stigma and anxiety has been observed in the HIV-positive MSM populations. There has been evidence that intervention that facilitates information dissemination, and promotes emotional disclosure, coping and social support (53, 54) would be effective in reducing self-stigma for people living with HIV. Furthermore, a systematic review has also suggested that intervention that utilizes cognitive behavioral therapy or cognitive behavioral stress management would be effective in reducing anxiety for people living with HIV (55).

Third, results suggest that increasing social support might be a useful tool for HIV-positive MSM in buffering the adverse effect of self-stigma and anxiety. Peer support group would have great potential to serve as a hub for network and emotional support for HIV-positive MSM, as most of them would be more comfortable interacting with peers with similar backgrounds and challenges (56). Linkage with healthcare professionals has also been shown to be effective in improving social support for people living with HIV (57).

Limitations

There were several limitations of the study that should be noted. First of all, the study was cross-sectional in nature and causality could not be inferred from these results. Second, a self-selected bias might exist, that those who agreed to take part in the study might be healthier and thus less likely to use illicit drugs. Third, the use of face-to-face structured interview might have induced social desirability bias, therefore the prevalence of intention to use illicit drugs might have been under-reported. The lower level of illicit drug use detected might have caused an inadequate statistical power, thus increasing the chance of type 2 error. Fourth, as it would be inappropriate to examine the association between the psychosocial variables and past illicit drug use behaviors, only intention to use illicit drugs in the future was investigated in the study. As indicated in the literature, a gap between intention and behavior might exist (58). Longitudinal studies are warranted to elucidate the relationship between anxiety, self-stigma, and future illicit drug use behavior. Fifth, studies have reported that MSM used a variety of illicit drugs and most of them selectively use illicit drugs in some context such as before or during sex. The present study did not specifically assess their prevalence of illicit drug use in the context of sexual encounters. Sixth, the items for measuring social support were not validated although they were adapted from previous studies and the internal consistency was satisfactory. Finally, the sample was only collected in one city. Therefore, findings of the study might not be generalizable to all HIV-positive MSM in China.

Conclusion

The present study examined the association between anxiety, self-stigma, social support, and illicit drug use intention among Chinese HIV-positive MSM. Results showed that lifetime illicit drug use, anxiety and self-stigma were significant risk factors for intention to use illicit drugs among HIV-positive MSM. The buffering effect of social support was also confirmed, that the harmful effects of anxiety / self-stigma on illicit drug use intention was more evident among participants with lower level of support. Interventions to prevent illicit drug use should seek to reduce anxiety and self-stigma, and promote social support among HIV-positive MSM.

Acknowledgment

The study was supported by the Lifespan/Tufts/Brown Center for AIDS Research International Developmental Grant [P30AI042853] and the National Natural Science Foundation of China Young Scientists’ Grant [81302479].

References

- 1.National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. 2015. China AIDS response progress report 2015 [Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/CHN_narrative_report_2015.pdf.

- 2.NCAIDS C. Update on the AIDS/STD epidemic in China. Chin J Aids STD. 2016;22(10):767. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cochran SD, Ackerman D, Mays VM, Ross MW. Prevalence of non-medical drug use and dependence among homosexually active men and women in the US population. Addiction. 2004;99(8):989–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kerridge BT, Pickering RP, Saha TD, Ruan WJ, Chou SP, Zhang H, et al. Prevalence, sociodemographic correlates and DSM-5 substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among sexual minorities in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;170:82–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood GL, White EW, Page-Shafer K, Bein E, Osmond DH, Paul J, et al. Correlates of heavy substance use among young gay and bisexual men: The San Francisco Young Men’s Health Study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;61(2):105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrando S, Goggin K, Sewell M, Evans S, Fishman B, Rabkin J. Substance use disorders in gay/bisexual men with HIV and AIDS. American Journal on Addictions. 1998;7(1):51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O׳Cleirigh C, Magidson JF, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Prevalence of Psychiatric and Substance Abuse Symptomatology Among HIV-Infected Gay and Bisexual Men in HIV Primary Care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(5):470–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, Israelski DM, Stone L, Chesney MA, et al. Social Support, Substance Use, and Denial in Relationship to Antiretroviral Treatment Adherence among HIV-Infected Persons. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2003;17(5):245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrington RD, Woodward JA, Hooton TM, Horn JR. Life-threatening interactions between HIV-1 protease inhibitors and the illicit drugs MDMA and gamma-hydroxybutyrate. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(18):2221–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(8):721–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herek GM. AIDS and stigma. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42(7):1106–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: Prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(3):371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dlamini PS, Wantland D, Makoae LN, Chirwa M, Kohi TW, Greeff M, et al. HIV stigma and missed medications in HIV-positive people in five African countries. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(5):377–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waite KR, Paasche-Orlow M, Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Literacy, social stigma, and HIV medication adherence. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(9):1367–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18(8):904–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mo PKH, Mak WWS. Intentionality of medication non-adherence among individuals living with HIV/AIDS in Hong Kong. AIDS Care. 2009;21:785–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dowshen N, Binns HJ, Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(5):371–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang NG. Stigma, self-esteem, and depression:psychosocial responses to risk of AIDS. Human Organization. 1991;50:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, Bharat S, Chandy S, Wrubel J, et al. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67(8):1225–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kecojevic A, Wong CF, Corliss HL, Lankenau SE. Risk factors for high levels of prescription drug misuse and illicit drug use among substance-using young men who have sex with men (YMSM). Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;150:156–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chenard C The impact of stigma on the self-care behaviors of HIV-positive gay men striving for normalcy. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(3):23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy CE, Baral SD, Fielding-Miller R, Adams D, Dludlu P, Sithole B, et al. “They are human beings, they are Swazi”: intersecting stigmas and the positive health, dignity and prevention needs of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Swaziland. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16(4S3):18749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckerman A, Fontana L. Medical treatment for men who have sex with men and are living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Mens Health. 2009;3(4):319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnham KE, Cruess DG, Kalichman MO, Grebler T, Cherry C, Kalichman SC. Trauma symptoms, internalized stigma, social support, and sexual risk behavior among HIV-positive gay and bisexual MSM who have sought sex partners online. AIDS Care. 2016;28(3):347–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1946–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizuno Y, Borkowf C, Millett GA, Bingham T, Ayala G, Stueve A. Homophobia and racism experienced by Latino men who have sex with men in the United States: correlates of exposure and associations with HIV risk behaviors. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):724–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rendina HJ, Millar BM, Parsons JT. Situational HIV stigma and stimulant use: A day-level autoregressive cross-lagged path model among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;83:109–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dew MA, Becker JT, Sanchez J, Caldararo R, Lopez OL, Wess J, et al. Prevalence and predictors of depressive, anxiety and substance use disorders in HIV-infected and uninfected men: a longitudinal evaluation. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):395–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bertholet N, Cheng DM, Palfai TP, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Samet JH, Saitz R. Anxiety, Depression, and Pain Symptoms: Associations With the Course of Marijuana Use and Drug Use Consequences Among Urban Primary Care Patients. Journal of addiction medicine. 2018;12(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pufall EL, Kall M, Shahmanesh M, Nardone A, Gilson R, Delpech V, et al. Sexualized drug use (‘chemsex’) and high-risk sexual behaviours in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 2018;19(4):261–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchino BN, Bowen K, Kent de Grey R, Mikel J, Fisher EB. Social Support and Physical Health: Models, Mechanisms, and Opportunities. In: Fisher EB, Cameron LD, Christensen AJ, Ehlert U, Guo Y, Oldenburg B, et al. , editors. Principles and Concepts of Behavioral Medicine: A Global Handbook. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2018. p. 341–72. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen S, Gottlieb BH, Underwood LG. Social relationships and health. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brashers DE, Neidig JL, Goldsmith DJ. Social Support and the Management of Uncertainty for People Living With HIV or AIDS. Health Communication. 2004;16(3):305–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brashers DE, Neidig JL, Haas SM, Dobbs LK, Cardillo LW, Russell JA. Communication in the management of uncertainty: The case of persons living with HIV or AIDS. ComM. 2000;67(1):63–84. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen NB, Cavanaugh CE, Vaughan EL, Connell CM, Tate DC, Sikkema KJ. The influence of personality disorder indication, social support, and grief on alcohol and cocaine use among HIV-positive adults coping with AIDS related bereavement. AIDS and Behavior. 2009;13(2):375–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, Greene S, Sobota M, Koornstra J, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(3):337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buttram ME, Kurtz SP, Surratt HL. Substance use and sexual risk mediated by social support among Black men. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rueger SY, Malecki CK, Pyun Y, Aycock C, Coyle S. A meta-analytic review of the association between perceived social support and depression in childhood and adolescence. Psychol Bull. 2016;142(10):1017–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creswell KG, Cheng Y, Levine MD. A test of the stress-buffering model of social support in smoking cessation: is the relationship between social support and time to relapse mediated by reduced withdrawal symptoms? Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(5):566–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Dawson-Rose C, Parsons JT. Correlates of depressive symptoms among HIV-positive injection drug users: the role of social support. AIDS Care. 2003;15(5):689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Earnshaw VA, Lang SM, Lippitt M, Jin H, Chaudoir SR. HIV Stigma and Physical Health Symptoms: Do Social Support, Adaptive Coping, and/or Identity Centrality Act as Resilience Resources? AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(1):41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edelman EJ, Cole CA, Richardson W, Boshnack N, Jenkins H, Rosenthal MS. Stigma, substance use and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-infected men who have sex with men: A qualitative study. Preventive medicine reports. 2016;3:296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mak WWS, Cheung RYM. Self-stigma among concealable minorities: Conceptualization and unified measurement. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80(2):267–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy research. 2016;120:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu J, Cheng Y, Lau JTF, Wu AMS, Tse VWS, Zhou S. The Majority of the Migrant Factory Workers of the Light Industry in Shenzhen, China May Be Physically Inactive. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0131734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo S, Lin C, Feng N, Wu Z, Li L. Stigma towards people who use drugs: A case vignette study in methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. The International journal on drug policy. 2019;71:73–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan KY, Yang Y, Zhang KL, Reidpath DD. Disentangling the stigma of HIV/AIDS from the stigmas of drugs use, commercial sex and commercial blood donation - a factorial survey of medical students in China. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ouellette JA, Wood W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1998;12(1):54–74. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith JP, Book SW. Anxiety and Substance Use Disorders: A Review. The Psychiatric times. 2008;25(10):19–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crawford AM. Stigma associated with AIDS: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1996;26(5):398–416. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abel E, Rew L, Gortner EM, Delville CL. Cognitive reorganization and stigmatization among persons with HIV. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(5):510–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rao D, Desmond M, Andrasik M, Rasberry T, Lambert N, Cohn SE, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the unity workshop: an internalized stigma reduction intervention for African American women living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012;26(10):614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clucas C, Sibley E, Harding R, Liu L, Catalan J, Sherr L. A systematic review of Interventions for anxiety in people with HIV. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2011;16(5):528–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mo PKH, Coulson NS. Online support group use and psychological health for individuals living with HIV/AIDS. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(3):426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Broaddus MR, Hanna CR, Schumann C, Meier A. “She makes me feel that I’m not alone”: Linkage to Care Specialists provide social support to people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2015;27(9):1104–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sheeran P Intention—Behavior Relations: A Conceptual and Empirical Review. European Review of Social Psychology. 2002;12(1):1–36. [Google Scholar]