Abstract

Sphaeropsis sapinea is a fungal endophyte of Pinus spp. that can cause disease following predisposition of trees by biotic or abiotic stresses. Four morphotypes of S. sapinea have been described from within the natural range of the fungus, while only one morphotype has been identified on exotic pines in the Southern Hemisphere. The aim of this study was to develop robust polymorphic markers that could be used in both taxonomic and population studies. Inter-short-sequence-repeat primers containing microsatellite sequences and degenerate anchors at the 5′ end were used to target microsatellite-rich areas in an S. sapinea isolate. PCR amplification using an annealing temperature of 49°C resulted in profiles containing 5 to 10 bands. These bands were cloned and sequenced, and new short-sequence-repeat (SSR) primer pairs were designed that flanked microsatellite-rich regions. Eleven polymorphic SSR markers were tested on 40 isolates of S. sapinea representing different morphotypes as well as on 2 isolates of the closely related species Botryosphaeria obtusa. The putative I morphotype was found to be identical to B. obtusa. Otherwise, the markers clearly distinguished the remaining three morphotypes and, furthermore, showed that the C morphotype was more closely related to the A than the B morphotype. The B morphotype was the most genetically diverse, and the isolates could be further divided based on their geographic origins. Sequencing of different alleles from each locus showed that the most polymorphic markers had mutations within a microsatellite sequence.

Sphaeropsis sapinea is a fungal endophyte of Pinus spp. that is associated with symptomless infections and that was introduced into the Southern Hemisphere along with its hosts. Predisposition due to a variety of biotic and abiotic stress factors can result in this normally benign fungus causing substantial deaths in exotic pine plantations (12, 29). In South Africa, for example, significant economic losses in pine plantations occur due to shoot and crown dieback after hail (29, 35). S. sapinea is thought to reproduce solely by asexual mitospores, as no known sexual stage has ever been found in this well-studied fungus. Phylogenetic studies based on internal transcribed spacer sequence data group this fungus with species of Botryosphaeria that have Sphaeropsis anamorphs, most closely related to Botryosphaeria obtusa (11).

In the mid 1980s, two morphotypes (A and B) of S. sapinea from the United States were described, based on spore morphology and culture characteristics (19). This division was confirmed using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers (27). Two recent studies have provided evidence for a third and possibly a fourth morphotype. De Wet et al. (5) used the RAPD markers and morphological characters and showed the existence of a C morphotype of S. sapinea among isolates from Indonesia that had spores larger than those of the A morphotype. Likewise, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) fingerprinting of ribosomal DNA (DNA) coupled with morphological characters led Hausner et al. (9) to propose an I morphotype among Canadian isolates that had spores intermediate in size between those of the A and B morphotypes. RAPD analysis of New Zealand isolates of S. sapinea has also indicated high genomic variability and possibly the existence of more than just the A and B morphotypes (S. J. Kay, R. L. Farrell, D. Hofstra, T. Harrington, S. Duncan, A. Ah Chee, E. Hadar, Y. Hadav, and R. Blanchette, APPS, 12th Biennial Conf. Asia-Pacific Plant Pathol. New Millennium, p. 348).

RAPD-PCR uses short primers (10 bp) and low annealing temperatures to produce differential banding patterns between individuals, usually due to mutations at the primer binding sites. This results in dominant markers (presence or absence of a band) and occasionally codominant length polymorphism markers (23). With diploid organisms, dominant markers can be a problem because homozygous and heterozygous alleles cannot be distinguished, which results in biased gene diversity estimates (10). Many fungi are haploid, and distinguishing homozygous and heterozygous alleles is not necessary; however, some isolates will have null alleles, and this makes analysis difficult. In addition, the low annealing temperatures used for RAPD-PCR often cause problems with repeatability and reproducibility in other laboratories (2).

Codominant markers are powerful tools for genetic analysis of populations. RFLP analysis, which involves cutting genomic DNA with restriction enzymes to produce a complex DNA profile, does produce codominant markers, but it requires large quantities of DNA (23). RFLP analysis following the amplification of a known region of genomic DNA, such as the IGS region of stet rDNA (9), requires less DNA than RFLP analysis of complete genomic DNA (15). However, as only a few bands are produced, this technique can be used to identify isolates but is not suitable for population studies.

Techniques such as sequence characterized amplified regions PCR and simple sequence repeat (SSR), or microsatellite, PCR, where known DNA sequences are amplified, provide codominant Mendelian markers. These are much more powerful than dominant markers and can be used to determine population genetic structure, kinship, reproductive mode, and genetic isolation (21, 33). SSR markers are usually found by probing partial or enriched genomic libraries with di- or trinucleotide repeats (18). However, polymorphic markers, often rich in microsatellite repeats, have been developed by sequencing fragments amplified by RAPD-PCR (3, 4, 6) and inter-SSR (ISSR) PCR (2, 6, 34). During the last decade, SSR markers have been extensively used in population studies of many plants and animals (31), although to date there have been few studies of fungi (16). Fungal studies have generally used only a few markers, predominantly for genotyping (7, 8, 14, 17). Recently, however, Epichloë endophytes have been identified in planta using 11 polymorphic microsatellite markers (16).

The aim of this study was to develop polymorphic SSR markers for the identification of different S. sapinea morphotypes which could also ultimately be used in population studies. The robustness of the markers was tested on the previously described morphotypes. Polymorphic alleles at each locus were sequenced to establish the specific base changes causing the length polymorphisms and also to determine whether alleles were identical in length through mutation or by descent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal cultures.

Forty single conidial isolates of S. sapinea were used in this study: 13 of the A morphotype, 14 of the B morphotype, 11 of the C morphotype and 2 of the I morphotype (4, 9, 19, 27) (Table 1). A morphotype isolates were from the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. B morphotype isolates were from the United States and Mexico. Isolates from the United States included CMW 190 and 189, first described as representative of the A and B morphotypes, respectively, by Palmer et al. (19). Many other isolates had been characterized in previous studies (Table 1) (4, 9, 19, 27). C morphotype isolates were collected from four plantations within 20 km of each other in Indonesia (4). I morphotype isolates were from Canada (9). Two isolates of a closely related species, B. obtusa, were included for comparison. The isolates were maintained on malt extract agar and are all stored in the culture collection at the Forestry and Agriculture Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria.

TABLE 1.

Isolates used in this study

| Species | Isolate no. | Other code | Morphotype | Origin | Collector | SSR profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. sapinea | CMW 190c | 124a | A | USA | M. A. Palmer | 11215322765 |

| CMW 5974 | 94-100e | A | USA | G. Stanosz | 11217312665 | |

| CMW 5975 | 94-29e | A | USA | G. Stanosz | 11215322562 | |

| CMW 4332c | 95-69e | A | USA | G. Stanosz | 11215322962 | |

| CMW 5976 | 94-111e | A | USA | G. Stanosz | 11215322664 | |

| CMW 5977 | A | Australia | T. Burgess | 11215322572 | ||

| CMW 5978 | A | Australia | T. Burgess | 11214322562 | ||

| CMW 5979 | A | Australia | T. Burgess | 11214322862 | ||

| CMW 5980 | A | South Africa | H. Smith | 11214322872 | ||

| CMW 5981 | A | New Zealand | P. TenVelde | 11214322862 | ||

| CMW 4899c | A | Mexico | M. J. Wingfield | 11216322862 | ||

| CMW 5693 | SSM 910875d | A | Canada | J. Reid | 11217413565 | |

| CMW 5695 | SSM 900297d | A | Canada | J. Reid | 11215323762 | |

| CMW 189c | 124ab | B | USA | M. A. Palmer | 23323274213 | |

| CMW 4334c | 474b | B | USA | G. Stanosz | 13223274213 | |

| CMW 4333c | 215ab | B | USA | G. Stanosz | 23325275313 | |

| CMW 5982 | B | USA | M. J. Wingfield | 43327269112 | ||

| CMW 5983 | B | USA | M. J. Wingfield | 43326268117 | ||

| CMW 5984 | B | USA | M. J. Wingfield | 33323267116 | ||

| CMW 5985 | B | USA | M. J. Wingfield | 13325267116 | ||

| CMW 4896c | B | Mexico | M. J. Wingfield | 23318283318 | ||

| CMW 4900c | B | Mexico | M. J. Wingfield | 53315283317 | ||

| CMW 4898c | B | Mexico | M. J. Wingfield | 13317286313 | ||

| CMW 4897c | B | Mexico | M. J. Wingfield | 43315283315 | ||

| CMW 5694 | SSM 910843d | B | Canada | J. Reid | 23224276213 | |

| CMW 5698 | UM 955d | B | Canada | J. Reid | 23224274216 | |

| CMW 5699 | UM 958d | B | Canada | J. Reid | 23224276213 | |

| CMW 5986 | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332431 | ||

| CMW 5987 | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332431 | ||

| CMW 5988 | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332451 | ||

| CMW 5989 | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332451 | ||

| CMW 5990 | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332431 | ||

| CMW 4876c | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332451 | ||

| CMW 4877c | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 41212332441 | ||

| CMW 4878c | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11312332451 | ||

| CMW 4881c | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332451 | ||

| CMW 4883c | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332451 | ||

| CMW 4886c | C | Indonesia | M. J. Wingfield | 11212332451 | ||

| CMW 5696 | SSM 920729d | I | Canada | J. Reid | 22311241624 | |

| CMW 5697 | SSM 810704d | I | Canada | J. Reid | 22311241724 | |

| B. obtusa | CMW 5991 | South Africa | W. A. Smit | 22131151724 | ||

| CMW 5992 | South Africa | W. A. Smit | 22131151724 |

DNA extraction.

A small plug (4 mm2) of actively growing mycelium from the edge of 7-day-old cultures was transferred to Eppendorf tubes containing 0.5 ml of malt extract broth. The tubes were inverted and incubated at 25°C for 3 days. The tubes were then centrifuged, the broth was removed, and the mycelium was freeze-dried and stored at −20°C until it was required. The mycelium (approximately 10 mg) was ground to a fine powder with a pestle in the same Eppendorf tube, using liquid nitrogen to keep the mycelium frozen, and DNA was extracted as previously described (22). The DNA concentration was estimated by comparing the intensity of ethidium bromide fluorescence of the DNA sample to a known concentration of lambda DNA marker on agarose gels using a UV transilluminator imaging system (UVP, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

Development of SSR markers.

ISSR-PCR of S. sapinea isolate CMW 5977 (belonging to the A morphotype) was conducted with seven primers, 5′DDB(CCA)5, 5′DHB(CGA)5, 5′YHY(GT)5G, 5′HVH(GTG)5, 5′NDB(CA)7C, 5′NDV(CT)8, and 5′HBDB(GACA)4, as previously described (34) except that an annealing temperature of 49°C was used for all of the primers. The amplification products from each ISSR primer were purified with the High Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The purified products were ligated overnight at 10°C into the pGEM-T vector using the pGEM-T Easy Vector System (Promega, Madison, Wis.). The ligation products were transformed into competent Escherichia coli JM109 (Promega) and screened on Luria-Bertani medium containing 80 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) ml−1, 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1. Positive clones were grown overnight in Luria-Bertani medium containing 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1, and the plasmids were recovered by alkaline lysis (25). Plasmid DNA was digested with EcoRI to release the insert and determine its size. Inserts were sequenced with the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) using the T7 and Sp6 universal primers. The products were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) on an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Corp.). Electropherograms were analyzed using Sequence Navigator software (Perkin-Elmer Corp.).

Genome walking.

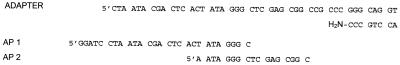

For some sequences, the microsatellite region of interest was at the beginning or end of the insert in the region recognized by the ISSR primer. In order to obtain the full repeat sequence, genome walking was performed using a modification of the method previously described (26). Genomic DNA (1.2 μg) of isolate CMW 5977 was digested in separate tubes with 10 U of one of three blunt-ended restriction enzymes (HaeIII, EcoRV, and ScaI). The cut DNA was extracted as described above, and the adapter DNA (Fig. 1) was then ligated to each restriction digest, creating three libraries (26). Each library was used as a template in primary PCRs, using a gene-specific primer from the sequence of interest and the first adapter-specific primer, AP1 (Fig. 1). The PCR mixture contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 50 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 300 nM (each) primer, 2 ng of DNA, 5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and water to a final volume of 50 μl. The reactions were carried out in an Eppendorf (Hamburg, Germany) thermocycler programmed for an initial denaturization of 1 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 95°C and 6 min at 68°C, and a final extension of 15 min at 68°C. The lower strand of the adapter has an amine group that blocks polymerase extension, preventing the generation of the primer binding site, unless a defined distal gene-specific primer extends a DNA strand opposite the upper strand of the adapter.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of adapter and primer sequences used in genome walking as given by Siebert et al. (26).

A secondary PCR was conducted with 1 μl of a hundredfold dilution of the primary PCR product using a nested gene-specific primer and the second adapter-specific primer, AP2 (Fig. 1). The reaction mixture composition was the same, as were the cycle parameters, except that 20 cycles were performed. AP2 is shorter than the adapter. If any individual strands are generated that contain double-stranded adapter sequences at both ends, then the ends of these strands form a panhandle structure following the denaturization step due to the presence of inverted repeats. This structure is stable and will not be amplified. Thus, strands that have the adapter at one end and the specific primer at the other are favored.

The amplification products were separated on a 1% agarose gel. If no bands were produced after the secondary PCR, then the thermocycler program was changed for both the primary and secondary PCR for an initial denaturization of 1 min at 95°C, followed by cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 1 min at 60°C, and 6 min at 68°C, and a final extension of 15 min at 68°C. The rationale was that 68°C might have been too high for the gene-specific primer to bind, and thus, using a lower annealing temperature could produce improved binding and amplification of the desired region.

The resultant bands were excised from the gel and dissolved in 100 μl of water, and 1 μl was used as a template in a tertiary PCR using the same reaction mixture composition as before but changing the thermocycler program for an initial denaturization of 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 40 s at 60°C, 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C. The amplification product was then purified, sequenced, and aligned with the known sequence.

PCR amplification of SSR loci.

Specific primers were designed to flank microsatellite-rich regions. Particular care was taken to identify primer pairs that would amplify different-size fragments. This allows multiplexing of more than one reaction per lane during analysis of the fragments. Twenty-two primer pairs were constructed to amplify microsatellite-rich regions or SSRs in S. sapinea. Primer pairs were designed with a melting temperature between 58 and 66°C (Table 2). SSR-PCR was conducted with a PCR mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 100 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 300 nM (each) primer, 2 ng of DNA template, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and water to a final volume of 25 or 50 μl. The reactions were carried out in either a HYBAID (Teddington, United Kingdom) or an Eppendorf thermocycler programmed for an initial denaturization of 2 min at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 40 s at the annealing temperature (Table 3), and 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension of 7 min at 72°C.

TABLE 2.

Core sequence amplified by SSR primer pairs designed for S. sapinea

| SSR primer pair | Sequence | Calculated Tm (°C)b | Expected fragment length (bp) | Core sequencec | Annealing temp (°C) | Band pattern | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB1 | 5′ CAT GCA TCG ATC CTG TAG AGC | 60 | 324 | Alternates between regions rich in G, C, and T and regions rich in G, C, and A (each about 20 bp) | 58 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB2-2 | 5′ CCA AGT GAT GAC CCT ATA GAG | 60 | ||||||

| TB3 | 5′ CCT CAG TCC TCT AAC ATC ACC | 58 | 297 | Sequence rich in T, TT, and TTT | 58 | Single band; monomorphic | ||

| TB4 | 5′ GAA TGA CAG AGG ACA TAG TCC | 58 | ||||||

| TB5 | 5′ TGT GGT GAG AGA CTA CTG GAC | 60 | 199 | ∗(GA)3∗(CT)4∗; sequence rich in A | 58 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB6 | 5′ CGC TCA TTT GCT GGA ACT TGG | 60 | ||||||

| TB7 | 5′ GCC GAA TTG AAC GGC AGA GC | 62 | 182 | Sequence rich in G and A (>70%) | 58 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB8 | 5′ CAG TGT CGA TTG CTC GCT CG | 61 | ||||||

| TB9 | 5′ CGA CAC GAA CAA CCA CTG GC | 60 | 182 | Sequence rich in CCG and GGT | 58 | Single band; monomorphic | ||

| TB10 | 5′ CCT CCA TGT CAA CAG CGG TG | 60 | ||||||

| TB11 | 5′ CTG ATA GTA GAC GGC GCT CG | 61 | 174 | ∗GA∗(GA)3∗(GA)2∗ | 54–64 | Multiple bands | ||

| TB12 | 5′ GAC ATT CTC AAC GGT GAG CC | 60 | ||||||

| TB13 | 5′ GAG TCC TTC GTT CGG GAA C | 60 | 291 | ∗(CCCT)3∗(GCC)4 | 62 | Single band; monomorphic | ||

| TB14 | 5′ CGA CAA TTA AGC GTG GCG TG | 60 | ||||||

| TB15 | 5′ GAG GAC TCC GAC GCA GAG T | 61 | 406 | Regions rich in CT, CTT, and CCT | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB16 | 5′ CGG AGG TGG CTT CTC TTA AG | 60 | ||||||

| TB17 | 5′ GCA ACC GCT TCT GGA ATT TC | 57 | 205 | ∗(T)22∗; regions rich in T | 54–64 | No amplification | ||

| TB18 | 5′ GCT TGA TTA ATG ATG GTG CG | 55 | ||||||

| TB19 | 5′ CCT GAG CGA CTC CAA GCT TG | 61 | 453 | ∗(T)19∗; regions rich in C and T or G and A | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB20-2 | 5′ CTC ATT GGC TGC GAA ACG TG | 62 | ||||||

| TB21 | 5′ CCA TCA GGA AGC CTT TGT GAC | 60 | 237 | ∗(G)5∗(T)7∗(T)9A(T)5∗(TCTCCC)3∗ | 58 | Single band; polmorphic | ||

| TB22 | 5′ CTT TAC TTA CGT CAT GGT GCG | 58 | ||||||

| TB23 | 5′ GAC AGA CAT CTA GGC CCT GC | 61 | 384 | ∗(T)6C(T)4∗(T)8(GATTTT)2∗(TCC)5∗(CGA)3∗; a 100-bp T-rich region (>60%) | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB24 | 5′ GAT CAG TCG GTC GAG ACG AG | 61 | ||||||

| TB25 | 5′ GGT CTA AAT GCT GCT GGC C | 59 | 320 | ∗(TGC)3∗(TACA)3∗(GAC)3∗(GGT)4∗(GCA)8∗ | 54–64 | Multiple bands | ||

| TB26 | 5′ CAC TGG TGC TGC TTT CGT GCC | 61 | ||||||

| TB27 | 5′ GTA CGT ACG TAC CCC AGA CG | 61 | 260 | ∗(CG)3∗(A)6∗; sequence rich in GAA and TC | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB28 | 5′ CCG CAC ATA AGA TGC CAG GA | 60 | ||||||

| TB29 | 5′ CAT TTC GCT GCC AAA CAC TCT | 58 | 310 | ∗(CGGG)3∗(TG)4∗(TA)3∗(TTTC)5∗(TC)5∗ | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB30 | 5′ CCA CCG CCA GAC ACC ATT AG | 61 | ||||||

| TB31 | 5′ CCT AAG CAG CGA CGC CTT TC | 61 | 310 | Sequence rich in T | 54–64 | Multiple bands | ||

| TB32 | 5′ CAG CGG ACC CAC TGA GAT AC | 61 | ||||||

| TB33 | 5′ CGG ACC CAC TGA GAT ACC AG | 61 | 374 | ∗(T)8G(T)5∗(CT)4∗ | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB34 | 5′ GAA ACA CCC GTG TGC GAG TG | 61 | ||||||

| TB35-2 | 5′ CCA CGA ATA ACG CCC CCA CC | 61 | 286 | ∗(GA)5∗(GAAA)5∗(TA)3∗(CA)4∗(CCCG)3∗ | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB36a | 5′ GCA TGG CAT CAG TGT CTG GC | 61 | ||||||

| TB37 | 5′ CAG CGG TTT CAT TGA AAT GCC | 58 | 252 | ∗(T)15∗(GC)4∗(TG)4∗(GA)4∗ | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB38 | 5′ GAC TTG TCT CCT ACC GAT TCC | 60 | ||||||

| TB39 | 5′ GTG AAG GGT TCT GCC TGT GT | 60 | 472 | ∗(TA)5∗(GAC)3∗(GAT)5∗(T)15∗(CAA)3∗(A)9∗ | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB40 | 5′ GAC TGG GAG GGG AGC ATA TG | 61 | ||||||

| TB41 | 5′ GCC AAC CCT AAT GCT TCC ATG | 60 | 313 | ∗(CA)2∗(CA)2∗(CA)12CCCAA(CA)4∗(CAG)3∗(CCG)3∗ | 62 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB42a | 5′ CAG CGG CGA TTG CGG TAT GG | 60 | ||||||

| TB43 | 5′ GTA ACA TTT CCC CAC GTC AGC | 60 | 174 | ∗(GTT)2AA(GTT)2(G)7∗(GGGTA)3∗ | 58 | Single band; polymorphic | ||

| TB44a | 5′ GGA AGT ACT ACA TGG TCT TCG | 58 |

Primer pairs designed after genome walking.

Im, melting temperature.

Parentheses indicate repeated motifs, and subscript numbers indicate the number of repeats. ∗, unspecified length of sequence.

TABLE 3.

Alleles observed at each locus for S. sapinea morphotypes and B. obtusa and summary of mutational processes causing polymorphisms among S. sapinea morphotypes A, B, and C

| Locus | SSR primers | Annealing temp (°C) | Allele(s)

|

Mutational processesa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. sapinea morphotype

|

B. obtusa | |||||||

| A | B | C | I | |||||

| SS1 | TB1 and 2-2 | 58 | 326 | 326, 361, 432, 468, 508 | 326, 468 | 361 | 361 | Transversion: C→A |

| Transition: G→A6, C→T3 | ||||||||

| Indel: TGT, C, AC (CCCGGTCTCTGCTACATGAACGAGGACGACGGGCTG)1–5 | ||||||||

| SS2 | TB5 and 6 | 58 | 198 | 206 | 198 | 204 | 204 | Transversion: C→A2 |

| Transition: G→A, C→T | ||||||||

| Indel: CATA, C, A, GT, AA, G | ||||||||

| SS3 | TB7 and 8 | 58 | 182 | 182, 184 | 182, 184 | 184 | 171 | Transversion: C→A |

| Transition: G→A3 | ||||||||

| Indel: AAA, A2, G3 | ||||||||

| SS4 | TB15 and 16 | 62 | 406 | 406, 409 | 406 | 406 | Null | Transversion: G→C |

| Indel: G2 | ||||||||

| SS5 | TB19 and 20-2 | 62 | 452, 453, 454, 455 | 451, 452, 453, 454, 455, 456 | 450 | 443 | 443 | Transversion: G→T, T→A |

| Transition: G→A3, C→T2 | ||||||||

| Indel: A, TGTA, CTA, (T)0–6 | ||||||||

| SS6 | TB21 and 22 | 58 | 237 | 224 | 237 | 224 | 220 | Transversion: C→A, G→C, G→T |

| Transition: G→A, C→T3 | ||||||||

| Indel: CAC, C2, G, TTATTTT, TCCCTC | ||||||||

| SS7 | TB23 and 24 | 62 | 384, 383 | 396, 404, 411, 415 | 387 | 389 | 394 | Transversion: C→A, G→C |

| Transition: G→A6, C→T6, | ||||||||

| Indel: T2, CC, A2, (T)0–4, TCT, CTC, (TCT)0–7 | ||||||||

| SS8 | TB35-2 and 36 | 62 | 285 | 287, 293, 301, 305, 333, 337, 349 | 285 | 281 | 281 | Transversion: C→A, T→A |

| Transition: G→A2, C→T2 | ||||||||

| Indel: AGA, TA, G2, A, (GAAA)0–16 | ||||||||

| SS9 | TB37 and 38 | 62 | 252, 253, 255, 256, 257 | 236, 237, 238 | 250 | 253, 255 | 255 | Transversion: G→C, C→A, T→A |

| Transition: G→A2, C→T3 | ||||||||

| Indel: T, A2, G, (T)0–12, TGG, TAG(TG)3G | ||||||||

| SS10 | TB41 and 42 | 62 | 313, 315 | 288 | 308, 310, 312 | 306 | 306 | Transversion: C→A, T→A |

| Transition: G→A, C→T4 | ||||||||

| Indel: (CA)0–9CCCAA(CA)0–4 | ||||||||

| SS11 | TB43 and 44 | 58 | 174, 176, 177 | 174, 175, 177, 178, 179, 180 | 173 | 176 | 176 | Transversion: G→C, T→A2, G→T, C→A |

| Transition: G→A2, C→T2 | ||||||||

| Indel: (C)0–5, T2, A2, CT, (G)0–6, (A)6CCACC, TAGG(A)3GA | ||||||||

Parentheses surround repeated motifs, with the subscript indicating the number of repeats. Subscripts after motifs not in parentheses indicate a mutation that occurs more than once in the sequence but not as a repeat.

Polymorphisms were identified by separating the amplification products by nondenaturing PAGE (6% acrylamide in 50 mM Tris-borate-EDTA buffer; 7 h at 140 V) followed by silver staining (1). If a primer pair produced a single band that was polymorphic in different isolates, then one of the pair was labeled with a phosphoramidite fluorescent dye, TET or FAM (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany) (Table 2).

Separation of SSR-PCR products.

Fluorescence-labeled SSR-PCR products (0.5 μl containing approximately 1.5 ng of DNA from each amplification product) and 0.5 μl of the internal standard GS-500 TAMRA (Perkin-Elmer Corp.) were added to 1.5 μl of loading buffer. The mixture was heated to 95°C for 3 min. One microliter of this mixture was separated by PAGE (4.25% acrylamide) on an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer. The allele size was estimated by comparing the mobility of the SSR products to that of the internal size standard as determined by GeneScan 2.1 analysis software (Perkin-Elmer Corp.) in conjunction with Genotyper 2 (Perkin-Elmer Corp.). Repeatibility was confirmed by running the same reference samples (from S. sapinea isolate CMW 5977) on every gel.

Data analysis.

Data from Genotyper were compiled in Excel files (Microsoft). For each isolate, a data matrix of characters was compiled by scoring the presence or absence of each allele at each locus. For simplicity, these data are presented as multistate characters (Table 1). Parsimony analysis was performed on the data set using PAUP∗ (30). The most parsimonious trees were obtained by using heuristic searches with random addition in 1,000 replicates, with the tree bisection-reconnection branch-swapping option on and the steepest-descent option off. Bootstrap consensus trees were constructed using the same conditions.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences for each of the SSR loci have been deposited in the GenBank database with the accession numbers AF263294 to −304 for SS1 to SS11, respectively.

RESULTS

Evaluation of SSR markers.

The ISSR primers each amplified 5 to 10 bands that ranged in size between 300 and 2,500 bp. A total of 42 cloned inserts were sequenced, 6 from each of the primers. Nineteen SSR primer pairs were designed to flank microsatellite-rich regions found within the sequence.

Genome walking was performed by using primers designed from four cloned inserts, and when completed, a further three SSR primer pairs were designed (TB35 and -36, TB41 and -42, TB43 and -44). Thus, from 42 clones, 22 primer pairs were designed. Repeat motifs in the core sequence ranged from 3 to 22 uninterrupted repeats, with most inserts comprising a number of repeat motifs separated by imperfect repeats (Table 2). TB35 and -36 and TB29 and -30 were found to amplify overlapping regions of sequence, and the pair TB29 and -30 was thereafter excluded (Table 2).

Of the 21 primer pairs (TB29 and -30 excluded), only one failed to produce bands over a range of annealing temperatures, three produced multiple bands, and three were monomorphic. The remaining 15 SSR primer pairs each amplified a single band that was polymorphic between isolates of S. sapinea (Table 2). The primer pairs amplified fragments at annealing temperatures of either 58 or 62°C and produced fragments ranging in size from 174 to 472 bp.

Identification of the putative I morphotype.

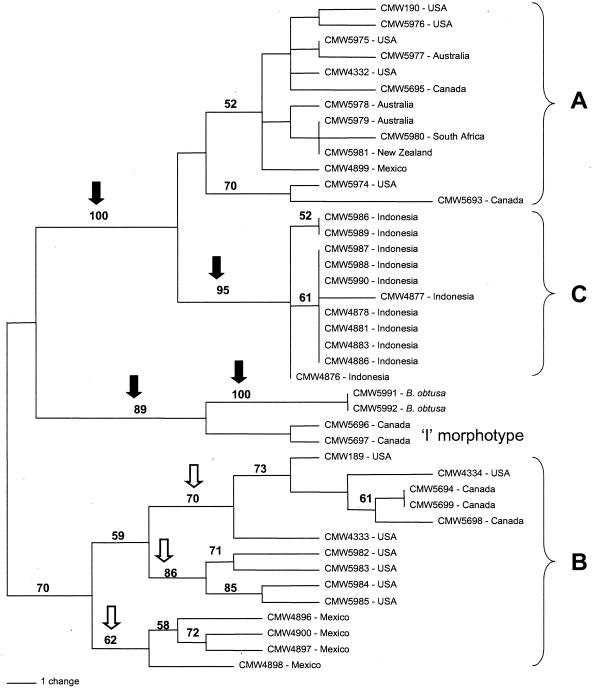

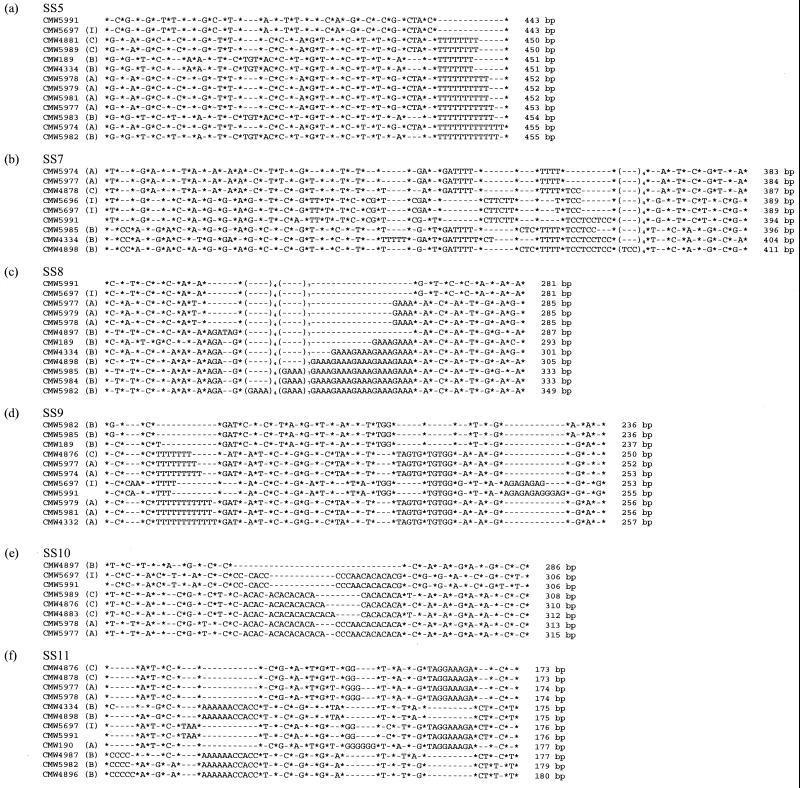

Two isolates of the I morphotype were examined. Phylogenetic analysis grouped these isolates with B. obtusa, and their separation from the other S. sapinea morphotypes had strong bootstrap support (Fig. 2). At SS2, SS5, SS8, and SS10, alleles were shared by B. obtusa and the I isolates which were not present in the other morphotypes (Table 3). Both B. obtusa and the putative I isolates shared alleles with the B isolates at SS1 and with the A isolates at SS9 and SS11. I isolates also shared alleles with the B isolates at SS3 and SS6 and with the A isolates at SS4. Interestingly, sequences of SS5, SS8, SS10, and SS11 were identical for the putative I isolates and B. obtusa (Fig. 3). Allele size differed between the putative I isolates and B. obtusa at SS7 and SS9. However, in both cases this was due to a mutation in a microsatellite region, and all other substitutions and small indels were identical (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Unrooted most parsimonious tree generated from SSR polymorphic data showing bootstrap values for the major branches. The solid arrows indicate the strongly supported branches separating the A, B, and C morphotypes of S. sapinea from the putative I morphotype and the closely related B. obtusa. The open arrows indicate the moderately supported branches separating geographically isolated populations of the B morphotype.

FIG. 3.

Aligned nucleotide sequences indicating polymorphism among different isolates of S. sapinea at loci SS5 (a), SS7 (b), SS8 (c), SS9 (d), SS10 (e), and SS11 (f). ∗, unspecified length of homologous sequence; −, gaps that indicate variation between aligned sequences. The isolate code is given at the beginning, and the length of the fragment is shown at the end of each sequence. The morphotype of the isolate is given in parentheses after the code. The isolate without a morphotype, CMW5991, is B. obtusa.

Segregation of SSR alleles.

C isolates were monomorphic at 8 of the 11 loci, producing a total of only 15 alleles across all loci (Tables 1 and 3). A isolates were monomorphic at 5 of the 11 loci but produced 23 alleles across all loci. B isolates were only monomorphic at three loci (SS2, SS6, and SS10) and were the most diverse, with 38 alleles across all loci (Table 3).

At three loci (SS1, SS3, and SS4), one allele was shared among S. sapinea morphotypes A, B, and C. At all these loci, A isolates were monomorphic, and at SS4, C isolates were also monomorphic. At SS1 and SS3, C isolates had a second allele that was also present in B isolates. Isolates of the A and C morphotypes shared alleles at three further loci (SS2, SS6, and SS8), with both morphotypes being monomorphic at these loci. Overall, A and C isolates shared alleles at six loci, and at four of these loci, both morphotypes were monomorphic (Table 3).

Isolates of the B and C morphotypes also shared an allele at locus SS5 (Table 3). B isolates shared alleles with A isolates at SS11. B isolates shared alleles with other morphotypes at five loci, but they were polymorphic at all these loci, whereas isolates from the other morphotypes were monomorphic. Overall, B isolates displayed much more variability than A or C isolates. At three loci, SS7, SS9, and SS10, all morphotypes had unique alleles. These loci potentially could be used individually to distinguish the S. sapinea morphotypes.

Parsimony analysis of SSR markers.

The data matrix comprised 65 characters, each character representing an individual allele at one of the 11 polymorphic SSR loci. Of the 65 characters, 55 were parsimony informative. Heuristic searches using parsimony resulted in 362 trees of 114 steps, one of which is shown in Fig. 2. Bootstrap analysis supported strong branches separating each of the morphotypes.

The A morphotype had 12 genotypes among 13 isolates, the B morphotype had 13 genotypes among 14 isolates, and the C morphotype had 4 genotypes among 11 isolates (Fig. 2). Isolates representing the C morphotype were closely related. Isolates CMW 4878, 4881, 4883, 4886, 5987, 5988, and 5990, from four plantations in Indonesia, had identical SSR profiles. These clustered together with CMW 4877 with moderate bootstrap support (Table 1). Isolates CMW 5986 and 5989 were also identical.

A isolates were also closely related to each other, but less so than for the C isolates. Isolates CMW 5974 from the north-central United States and CMW 5693 from Canada differed from other A isolates and clustered together with moderate bootstrap support. All other isolates clustered together, with weak bootstrap support for any further divisions within this group.

Isolates representing the B morphotype showed the most variation with the largest distances between subgroups (Fig. 2). The isolates separated into three groups, with moderate bootstrap support based on their origins: Mexico (isolates CMW 4896, 4897, 4898, and 4900), California (isolates CMW 5982, 5983, 5984, and 5985), and north-central United States and Canada (isolates CMW 189, 4333, 4334, 5694, 5698, and 5699) (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Source of polymorphisms.

For each locus, two or more alleles were sequenced. There were many transitions and transversions that altered the sequence but not the size of the fragment (Fig. 2). Polymorphisms at loci SS5 (Fig. 3a), SS7 (Fig. 3b), SS8 (Fig. 3c), SS9 (Fig. 3d), and SS10 (Fig. 3e) were due to a mutation within a repeat motif. Polymorphism in locus SS1 resulted from a 36-bp indel that had been inserted between one and five times (Table 3). Polymorphisms at the remaining loci were due to indels of various sizes (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

At several loci, isolates of the same morphotype with the same allele size were also sequenced. At loci SS1, SS5, SS8, and SS11, A isolates with the same allele size had the same sequence (Fig. 3a, c, and f). At loci SS5 and SS11, C isolates with the same allele size also had the same sequence (Fig. 3a and f). For the B morphotypes, isolates with the same allele size at loci SS6 and SS9 had different sequences (Fig. 3d), while at loci SS5 and SS11 they had the same sequence (Fig. 3a and f). From these examples, it appears that for the A morphotype, alleles of the same size have identical sequences, and for the B morphotype, alleles of the same size can have different sequences. This supports observations of high levels of diversity among isolates of the B morphotype (Fig. 2).

At loci SS1, SS3, SS4, SS5, and SS11, alleles from B isolates were the same size as those from either the A or C isolates. These were sequenced to determine whether the alleles were identical by descent or through mutation. Alleles of the same size from different morphotypes at loci SS1, SS3, and SS4 had the same sequence. At loci SS5 and SS11, alleles of the same size from different morphotypes had different sequences (Fig. 2a and f and Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, ISSR-PCR was effectively used to produce SSR markers for S. sapinea. From 42 sequences amplified by ISSR, 22 primer pairs were designed, and of these, 15 produced polymorphic amplification products. This is a success rate of 35% compared with less than 10% for more traditional methods of obtaining polymorphic markers, such as screening genomic libraries with a microsatellite probe (2).

The SSR markers developed in this study clearly distinguished among the morphotypes of S. sapinea. Isolates previously designated as representing the A and B morphotypes using RAPD and morphological data were once again found within these groups using SSR-PCR (19, 27, 28). There were 16 common isolates for the current study and that of de Wet et al. (5), with the resultant classification of the morphotypes being the same for all but 2 isolates. These isolates, CMW 4886 and 4899, had been difficult to classify using RAPD (J. de Wet, personal communication). Isolate CMW 4899 was designated as belonging to the C morphotype by de Wet et al. (5), while SSR-PCR placed it firmly in the A morphotype group. CMW 4886 was designated as an A morphotype isolate by de Wet et al. (5), but using SSR-PCR it was shown to represent the C morphotype, along with all the other Indonesian isolates. The five isolates designated as belonging to the A and B morphotypes using RFLP (9) also fell into those groups using SSR-PCR. Overall, characterization of isolates by SSR-PCR gave the same results as those previously derived using the RAPD and RFLP techniques (4, 9, 27, 28).

The use of higher annealing temperatures and automated analysis resulted in highly reproducible SSR markers that are much more robust than the RAPD markers used previously (4, 27, 28). The SSR markers are also more useful than the RFLP profiles generated from rDNA (9). These RFLP profiles can be used to distinguish between morphotypes, but compared with polymorphic markers, they are of little use in population studies. Three of the SSR markers (SS7, SS9, and SS10) produced different-size alleles for each of the morphotypes and could be used for a simple diagnostic test to distinguish morphotypes of S. sapinea.

An interesting result of this study was that the two isolates described by Hausner et al. (9) as belonging to a putative I morphotype were found to be identical to B. obtusa. B. obtusa is closely related to S. sapinea and has a Sphaeropsis anamorph (11). B. obtusa is a cosmopolitan fungus that is commonly found in temperate areas on numerous woody hosts, including Pinus spp. (20). The two isolates used in this study were collected in Ontario, Canada, from Picea glauca and Pinus banksiana (9). Examination of SSR marker sequences for representative isolates of all morphotypes of S. sapinea and B. obtusa revealed that while some substitutions and small indels are unique to B. obtusa, many are identical to those found in either the A or B morphotype.

Parsimony analysis of SSR markers generated in this study strongly supported the divisions among the three S. sapinea morphotypes. The C morphotype, however, clustered closely with the A morphotype. This confirmed previous observations based on culture characteristics, spore morphology, and internal transcribed spacer sequence data (5). The isolates of the B morphotype were much more polymorphic than those of the A or C morphotype. This is particularly interesting, as the markers were developed using isolate CMW 5977, which is a representative of the A morphotype. As a general principle, markers are usually more diverse in the population for which they are designed.

The 14 isolates of the B morphotype separated into three groups based on geographic location. At five loci, different alleles were fixed in these geographically isolated populations. Genetic isolation can lead to the loss of shared polymorphisms (32, 33). Thus, when all isolates are examined together, it would appear that the population consisted of a number of clones when in fact each genetically isolated population could be undergoing recombination. In order to ascertain the mode of reproduction, geographically isolated populations will need to be examined separately (32, 33).

Genomic regions containing microsatellites are evolving and mutating more rapidly than other areas due to slipped-strand mispairing during replication, with the slippage rate dependent upon the length of the repeat (13). Thus, the longer the repeat the more likely there is to be slippage. This is supported by our sequence data. We observed that the most polymorphic of the 11 loci examined were those where mutations occurred in a repeat motif (SS7, SS8, SS9, and SS10).

In this study, we have clearly demonstrated sequence differences between alleles of the same size. At loci SS5 and SS11, isolates of the A and B morphotypes of S. sapinea all shared an allele. Sequencing of these fragments showed that they are very different. Although microsatellite alleles are considered to be codominant markers, differences in alleles are measured based solely on size. There is the possibility of single point mutations within the flanking sequence that do not result in a change in the fragment length. It is also possible that different indels could result in fragments of the same size that have different sequences. Thus, the genotypic diversity in a population will always be underestimated using such markers. Additional information could be obtained from loci such as SS11, using single-strand conformation polymorphisms of same-size alleles to confirm their similarity in sequence as well as size (6, 24).

The SSR markers developed in this study can be used to distinguish morphotypes of S. sapinea. However, the markers are more powerful than a simple diagnostic tool. Interesting results will emerge from comparing populations of this asexual fungus from distinct geographic locations. Thus, future studies will focus on the population diversity and recombination within and between native and introduced populations of S. sapinea.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Oliver Preisig, Albe van der Merwe, Juanita de Wet, and Paulette Bloomer for advice and Paul TenVelde for collecting isolates of S. sapinea in New Zealand.

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the University of Pretoria, the National Research Foundation, members of the Tree Pathology Co-operative Programme, and THRIP funding from the Department of Trade and Industry, South Africa.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blum H, Beier H, Gross H J. Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis. 1987;8:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brady J L, Scott N S, Thomas M R. DNA typing of hop (Humulus lupulus) through application of RAPD and microsatellite marker sequences converted to sequence tagged sites (STS) Euphytica. 1996;91:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt A, Carter D A, White T J, Taylor J W. DNA sequencing with arbitrary primer pairs. Mol Ecol. 1994;3:523–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1994.tb00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desmarais E, Lanneluc I, Lagnel J. Direct amplification of length polymorphisms (DALP) or how to get and characterize new genetic markers in many species. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1458–1465. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.6.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Wet J, Wingfield M J, Coutinho T A, Wingfield W D. Characterization of Sphaeropsis sapinea isolates from South Africa, Mexico and Indonesia. Plant Dis. 2000;84:151–156. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2000.84.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dusabenyagasani M, Lecours N, Hamelin R C. Sequence-tagged sites (STS) for molecular epidemiology of scleroderris canker of conifers. Theor Appl Genet. 1998;97:789–796. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geistlinger J, Weising K, Kaiser W J, Kahl G. Allelic variation at a hypervariable compound microsatellite locus in the ascomycete Ascochyta rabiei. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;256:298–305. doi: 10.1007/s004380050573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groppe K, Boller T. PCR assay based on a microsatellite-containing locus for detection and quantification of Epichloë endophytes in grass tissue. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1543–1550. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1543-1550.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausner G, Hopkin A A, Davis C N, Reid J. Variation in culture and rDNA among isolates of Sphaeropsis sapinea from Ontario and Manitoba. Can J Plant Pathol. 1999;21:256–264. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isabel N, Beaulieu J, Thériault P, Bousquet J. Direct evidence for biased gene diversity estimates from dominant random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) fingerprints. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:477–483. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs K A, Rehner S A. Comparison of cultural and morphological characters and ITS sequences in anamorphs of Botryosphaeria and related taxa. Mycologia. 1998;90:601–610. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laughton E M. The incidence of fungal diseases of timber trees in South Africa. S Afr J Sci. 1937;33:337–382. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levinson G, Gutman G A. Slipped-strand mispairing: a major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:203–221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longato S, Bonfante P. Molecular identification of mycorrhizal fungi by direct amplification of microsatellite regions. Mycol Res. 1997;101:425–432. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahuku G S, Hsiang T, Yang L. Genetic diversity of Microdochium nivale isolates from turfgrass. Mycol Res. 1998;102:559–567. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moon C D, Tapper B A, Scott B. Identification of Epichloë endophytes in planta by microsatellite-based PCR fingerprinting assay with automated analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1268–1279. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1268-1279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neu C, Kaemmer D, Kahl G, Fischer D, Weising K. Polymorphic markers for the banana pathogen Mycosphaerella fijiensis. Mol Ecol. 1999;8:523–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostrander E A, Jong P M, Rine J, Duyk G. Construction of small-insert genomic DNA libraries highly enriched for microsatellite repeat sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3419–3423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer M A, Stewart E L, Wingfield M J. Variation among isolates of Sphaeropsis sapinea in North Central United States. Phytopathology. 1987;77:944–948. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Punithalingam E, Waller J M. Botryosphaeria obtusa. CMI descriptions of pathogenic fungi and bacteria, no. 394. Kew, England: Commonwealth Mycological Institute and Association of Applied Biologists; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Queller D C, Strassmann J E, Hughes C R. Microsatellites and kinship. Tree. 1993;8:285–288. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90256-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raeder U, Broda P. Rapid preparation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1985;1:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. Genetic diagnostics in plant breeding: RAPDs, microsatellites and machines. Trends Genet. 1993;9:275–279. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(93)90013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosendahl S, Taylor J W. Development of multiple genetic markers for studies of genetic variation in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi using AFLP. Mol Ecol. 1997;6:821–829. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siebert P D, Chenchik A, Kellogg D E, Lukyanov K A, Lukyanov S A. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1087–1088. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.6.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith D R, Stanosz G R. Confirmation of two distinct populations of Sphaeropsis sapinea in the Northern Central United States using RAPDs. Phytopathology. 1995;85:669–704. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanosz G R, Swart W J, Smith D R. RAPD marker and isozyme characterization of Sphaeropsis sapinea from diverse coniferous hosts and locations. Mycol Res. 1999;103:1193–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swart W J, Wingfield M J, Knox-Davies P S. Sphaeropsis sapinea, with special reference to its occurrence on Pinus spp. in South Africa. S Afr For J. 1985;35:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swofford, D. L., PAUP∗ 4.0 phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (∗ and other methods). Sinauer, Sunderland, Mass.

- 31.Tautz D. Hypervariability of simple sequences as a general source of polymorphic DNA markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6463–6471. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.16.6463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor J W, Geiser D M, Burt A, Koufopanou V. The evolutionary biology and population genetics underlying fungal strain typing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:126–146. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor J W, Jacobson D J, Fisher M C. The evolution of asexual fungi: reproduction, speciation and classification. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1999;37:197–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.37.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Nest M A, Steenkamp E T, Wingfield B D, Wingfield M J. Development of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers in Eucalyptus from amplified inter-simple sequence repeats (ISSR) Plant Breeding. 2000;119:433–436. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zwolinski J B, Swart E J, Wingfield M J. Economic impact of a post-hail outbreak of dieback induced by Sphaeropsis sapinea. Eur J For Pathol. 1990;20:405–411. [Google Scholar]