Abstract

Objectives

The well-being of doctors is recognised as a major priority in healthcare, yet there is little research on how general practitioners (GPs) keep well. We aimed to address this gap by applying a positive psychology lens, and exploring what determines GPs’ well-being, as opposed to burnout and mental ill health, in Australia.

Design

Semi-structured qualitative interviews. From March to September 2021, we interviewed GPs working in numerous settings, using snowball and purposive sampling to expand recruitment across Australia. 20 GPs participated individually via Zoom. A semi-structured interview-guide provided a framework to explore well-being from a personal, organisational and systemic perspective. Recordings were transcribed verbatim, and inductive thematic analysis was performed.

Results

Eleven female and nine male GPs with diverse experience, from urban and rural settings were interviewed (mean 32 min). Determinants of well-being were underpinned by GPs’ sense of identity. This was strongly influenced by GPs seeing themselves as a distinct but often undervalued profession working in small organisations within a broader health system. Both personal finances, and funding structures emerged as important moderators of the interconnections between these themes. Enablers of well-being were mainly identified at a personal and practice level, whereas systemic determinants were consistently seen as barriers to well-being. A complex balancing act between all determinants of well-being was evidenced.

Conclusions

GPs were able to identify targets for individual and practice level interventions to improve well-being, many of which have not been evaluated. However, few systemic aspects were suggested as being able to promote well-being, but rather seen as barriers, limiting how to develop systemic interventions to enhance well-being. Finances need to be a major consideration to prioritise, promote and support GP well-being, and a sustainable primary care workforce.

Keywords: general medicine (see internal medicine), mental health, occupational & industrial medicine, primary care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A positive framework—examining how general practitioner (GPs) keep well and thrive—was deliberately selected to examine GPs’ well-being, which complements literature on mitigating burnout.

Qualitative inquiry assists in understanding complex interactions between different determinants of well-being.

Our diverse sample includes GPs working in a wide range of clinical settings in Australia.

Our results may not be generalisable to all GPs, particularly those working outside of the Australian context.

Selection bias needs to be considered in any voluntary research participation.

Introduction

Healthcare typically aims to improve patient care, population health and cost-effectiveness.1 2 The well-being of healthcare professionals has been recognised as a priority, and further key component of the wider goals for healthcare in the USA and Canada.1–5 In Australia, the ‘National Medical Workforce Strategy’ developed a joint vision to provide effective, universally accessible and sustainable healthcare across the entire population,6 whereby doctor well-being, and insufficient generalist capacity, have been identified as top concerns.6 7

General practice is ideally placed to address healthcare goals by crucially providing cost-effective care to patients, and underpinning population health. However, demand for generalist services outweighs supply in many countries, including the UK, the USA and Australia, with an even greater undersupply of Australian GPs forecast by 2030.8–14 The additional strain of the pandemic15 highlights the urgency of prioritising GP well-being. Professional organisations are aware, and endeavouring to address this by offering support (ie, Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) programmes and resources16 17), and funding research into GPs’ health and well-being.

Doctors’ health research is typically informed by the clinical model, and there is a substantial body of literature aiming to explore and mitigate burnout, distress and mental ill health,18–25 and improve doctors’ uptake of health services across different settings.26–30 There is comparatively little research—particularly qualitative—that deliberately applies a positive lens, and explores how GPs keep well and thrive. We aim to explore this gap by drawing on positive psychology to complement the clinical model. The field of positive psychology provides several theories, definitions and measures of well-being, and most are defined as multi-dimensional constructs.31 Diener’s theory of subjective well-being comprises cognitive, often assessed as (life) satisfaction and affective (emotional) components.32 Cognitive well-being is more stable over time than affective well-being, and is linked to factors such as status, life events and income that may involve an appraisal of well-being over time.33–35 Ryff’s ‘psychological well-being’36 includes six dimensions: positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, personal growth and self-acceptance. Flourishing or PERMA, as construed by Seligman is a well-being theory described by positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment.37

We conceptualise well-being, and mental ill health/burnout as distinct, although related constructs, which merit separate consideration. Other research groups have similarly recognised the importance of exploring well-being in its own right. For example, a UK group focused on ‘psychological well-being’, and ‘mental well-being’ in GPs.38 39 Another group qualitatively explored ‘well-being’ in GPs as distinct from ‘burnout’.40 We aimed to add to this burgeoning approach, and explore GP’s well-being in the Australian context.

Overall, there is remarkably little evidence on how to effectively increase GP well-being, and related positive constructs.41 Our recent systematic review of both trials and policy changes exemplified the use of a wide variety of interventions, constructs and metrics.41 The review showed that these interventions had no consistent definition of well-being or its components, a lack of consensus on how to measure it (often with a scattergun set of measures), and few theoretical links between the intervention content and well-being target. Interventions were typically aimed at the individual GP, involved mindfulness practice and showed low to moderate effectiveness. Very few interventions targeted organisations, or health systems yet much of the discourse suggests interventions to improve well-being should be delivered at these levels. If this is the case, we also need to know what determinants of well-being such interventions should focus on enhancing.

Objectives

A robust and sustainable generalist workforce is important. In order to bolster the well-being of Australian GPs, and ultimately address the gap in the literature regarding effective well-being interventions for GPs as seen through a positive lens, we aimed to:

Apply a positive framework to explore GPs’ well-being, and key, potentially modifiable factors that determine it.

Qualitatively analyse how these determinants are interconnected, and what the underlying drivers are.

Methods

Qualitative approach and research design

We applied a six-step qualitative thematic analysis,42–45 providing a flexible and accessible way of analysing qualitative data, enabling iterative exploration of patterns and relationships between different themes while ensuring research rigour. The six steps included: (1) familiarising with data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes and subthemes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) refining, defining and naming themes; and (6) writing the report.45 We used an inductive data-driven (bottom-up), and a critical realist epistemological approach to our analysis.46 A Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research47 reporting checklist is provided.

Researcher characteristics and reflexivity

Our research team (four females and three males) consisted of a PhD candidate with background in medicine and coaching psychology (DN); two GPs, one (BG) a representative of a Primary Health Network (PHN), a GP led organisation responsible for the primary care of a large geographical location typically serving a few hundred thousand people, and a representative (LA) of a national private GP organisation; two psychiatrists (NG, IBH); a psychologist/researcher (AM), and a researcher (CK) both with extensive qualitative expertise. Collaborating with GPs within our research team enabled reflexivity across personal, professional, organisational and systemic experiences.48

Context and sampling strategy

Recruitment was aimed at GPs, and GP registrars working clinically in Australia. We chose a maximum variation sampling approach,49 50 and purposely engaged PHNs and a private GP organisation to announce our study in e-newsletters and communications. Furthermore, we used flyers, social media and snowballing.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the design or conduct of this research project.

Data collection and management

DN interviewed GPs one-on-one online in password protected Zoom conferencing rooms. A semi-structured topic guide (online supplemental file 1)—developed by the entire team—provided a framework, while allowing for further explorative questions. Interview topics included demographic information about participants, GPs’ conceptualisation of well-being, factors promoting their well-being on a personal, organisational and systems level, the impact of culture in healthcare on well-being, accessing information and support to assist with their well-being, and the impacts of COVID-19 on their well-being. We planned 20 interviews with the potential for further interviews. After independent analysis of half the transcripts (DN, CK) no new codes or themes were identified.51 Interviews were continued to capture GPs from various geographical locations and experience levels. No additional themes emerged, meeting the criteria for thematic data saturation.52 We concluded at 20 participants as intended.

bmjopen-2021-058616supp001.pdf (148.8KB, pdf)

Interviews were audio-recorded, and securely managed on University of Sydney research servers. Verbatim transcripts were checked for accuracy against original recordings and de-identified by DN before analysis.

Data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis45 was facilitated by Nvivo12 software.53 DN, CK, AM, NG engaged in steps (1) to (3) as described above, based on three different, randomly selected transcripts that were allocated to each researcher. DN developed a preliminary codebook in consultation with the research team with themes and subthemes (step 4), and coded all transcripts using NVivo.53 CK independently reviewed all transcripts and double coded half of them. Inter-coder variability54 ranged from k=0.48 to k=0.99 depending on the theme, providing the basis for further dialogue, reflexivity, and theme development (step 4 and 5). The codebook was iteratively refined throughout the process (DN, CK), and by triangulation with AM and NG (step 5); detailed descriptions of all codes were developed. For step 6, reporting of results, see later.

Results

From March to September 2021, we interviewed 20 GPs (mean duration of 32 min; range 20–43 min) with diverse experience levels, backgrounds, geographical and work arrangements (table 1). The interviews captured participants’ conceptualisation of well-being; determinants of well-being; and strategies for well-being. Running through each was a current focus on COVID-19 impacts on GPs’ well-being. Given the numerous definitions and metrics of well-being available we specifically did not provide these to the participants to let them generate their own conceptualisations. When asked GPs mostly equated well-being in a fairly concrete fashion with good physical health, mental health, happiness and social connection, rather than some of the constructs, for example, achievement or engagement, in the literature. We then explored ‘What promotes well-being for you on a personal, practice and systems level?’.

Table 1.

Demographics of interviewed general practitioners (GPs)

| Demographic | N=20 | Sub demographic |

| Sex | 11 9 |

Women Men |

| Experience | 2 2 4 4 4 4 |

GP registrars (trainees) GPs with 1–5 years of experience as a fellow GPs with 6–10 years of experience as a fellow GPs with 11–20 years of experience as a fellow GPs with 21–30 years of experience as a fellow GPs with 31–40 years of experience as a fellow |

| Current location | 15 3 1 1 |

NSW (11 metropolitan, 4 regional) VIC (2 metropolitan, 1 rural) QLD (metropolitan) SA (metropolitan) |

| Previous location AUS | 9 | GPs had previously worked in Australian locations that included regional, rural, and remote settings across different states (NSW, QLD, VIC, SA, WA, NT) |

| Previous location overseas | 10 | GPs trained and/or worked overseas (including the UK, New Zealand, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent and Africa) |

| Special interests | 18 | GPs had special interests including one or several of the following: rural medicine, aboriginal health, mental health, women’s health, parental care, paediatrics, skin, eye health, sports medicine, veteran’s health, prison health |

| Other professional roles | 10 | GPs held other professional roles, sometimes including several of the following: academic (research and education), GP training, corporate and management, policy, medico legal, RACGP, ACRRM, practice accreditation, Australian defence force |

| Work arrangement | 2 3 15 |

GP registrars were salaried GPs currently were partners/principals in a practice, and several more had been practice-owners at some point during their career GPs provided clinical work as contractors, or have mixed arrangements depending on their roles |

| Billing | 4 1 4 2 9 |

Practices bulk billed only Practice billed privately only Practices had mixed billing Practices had other mixed means of funding (ie, government grants) Interviewees did not discuss practice billing structure |

ACRRM, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine; AUS, Australia; bulk billing, Medicare rebates cover practitioner charges (no out of pocket fees for patients); NSW, New South Wales; NT, Northern Territory; QLD, Queensland; RACGP, Royal Australian College of General Practice; SA, South Australia; VIC, Victoria; WA, Western Australia.

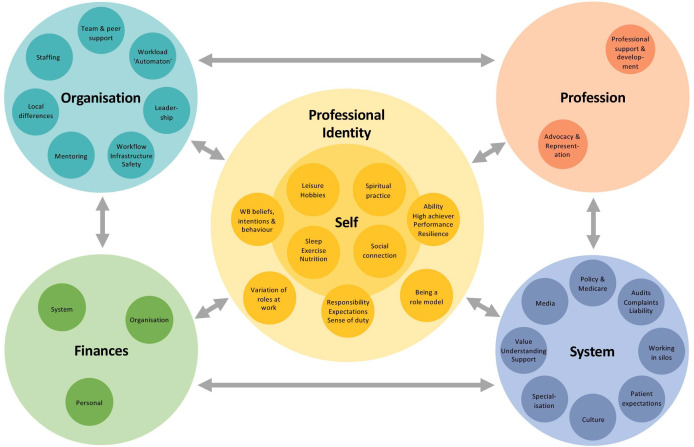

For determinants we discerned five themes, each with several subthemes. We charted these (figure 1), and important interconnections were analysed.

Figure 1.

Determinants of well-being in general practitioners and their interaction.

Strategies for well-being, and the COVID-19 specific influences on GP well-being are presented elsewhere.

Identity/self

Determinants of well-being were related to GPs’ identity as a person, and their identity as a professional with many seeing themselves as ‘well-being experts’ especially for physical and mental aspects of well-being (table 2a). Personal determinants included exercise, sleep, nutrition, social and community connection, leisure activities, spiritual practice and a ‘sense of balance’ overall (table 2b) determined by participants’ beliefs, intentions and behaviours.

Table 2.

Determinants of well-being—verbatim quotes

| Quote | Themes Subthemes |

Verbatim data (participant code) |

| a |

Identity/self Well-being beliefs, intentions and behaviour |

‘… I think it’s probably a case of the medical profession has lost control of wellbeing and it’s now the domain of Instagram influencers. … I think wellbeing as a principle is what we've been trying to do for years’. (GP9) |

| b |

Identity/self Exercise, nutrition social connection, leisure, hobbies |

‘So that’s probably exercise, and eating healthy, and being with friends and family is probably what keeps me well. … I suppose having your work/life in balance, and still being able to function at work at an optimal level, and still be able to maintain all your responsibilities outside of work, with family and recreation, I suppose. And being happy with both aspects of your life’. (GP18) |

| c |

Identity/self Responsibility, expectations, sense of duty |

‘You know, you’ve just got to be professional. Doesn’t matter how you’re feeling, doesn’t matter what’s happening. Work is work. And, if you don’t, bad things happen’. (GP5) |

| d |

Identity/self Ability, high achiever, performance, resilience |

‘I expect myself to be more resilient [than others]. And I expect myself to cope with hardships’. (GP8) |

| e |

Identity/self Variation of work roles |

‘If I work five, six, seven days [per week] in a general practice it really starts to affect you mentally. So, mixing it up is a fantastic way of keeping sane’. (GP5) |

| f |

System Specialisation |

‘The other things around the health system that I find very difficult and concerning, … is the proliferation of sub-, sub-, super-specialists. … That puts an incredible strain on you as a GP because now suddenly, like a GP is supposed to know everything. … You know, you’re a sub-doctor in everything, or you’re less of a doctor in everything because here these super-specialists telling you about the micro-details of how you should manage this one. But it also creates this huge gap. You’re the generalist, and the next step is to this super-specialist’. (GP14) |

| g |

Organisation Team and peer support |

‘I think that’s one of the most common causes of stress, depression, and mental illnesses in other practices, not having a good relationship with other GPs. … Belittling the other GP, and telling the patients that the other GP isn't good enough, or things like that. Or going against the medical advice of the other GP, even though that may have been correct, you know, trying to win over the patient, things like that’. (GP13) |

| h |

Organisation Local differences team and peer support |

‘And I feel quite strongly that general practice, particularly in [a metro area], is in a really bad state in relation to the lack of collegial relationships that most GPs have. And I really sense that moving from [a regional area], you know I came from—I worked in two separate practices as a registrar, with huge, big tearooms. We’d all sit down for like a one-and-a-half-hour lunch, just chat, connect, all that stuff. And then, I came back to [a metro area], and started going to interviews, and I said to everybody, like, ‘Where are your tearooms? Where do you guys have lunch?’ And they said, ‘Oh, I don’t know. Well, we were going to put a tearoom in, but we decided that, you know, we couldn’t really afford it. We just had to put another consulting room in’. Or others were like, ‘Well, I think the doctors just eat at their own table.’ And so, that I found really shocking. And I know that it’s, it’s just one thing. But I think that that really symbolizes just how much of a commodity that the general practitioner is seen as. You know, in most urban contexts… is you just come in, you sit at your table, you see the patients, and you go home. And I think that there’s a huge cost to that. You know that you’re, that you’re not having those, you know, informal chats over morning or lunch’. (GP12) |

| i |

Profession Advocacy and representation |

‘And I do find that the college is completely useless at sticking up for GPs. I refuse to join them. I find them very frustrating. They don’t, in my opinion, act as a good voice for us. So, mostly I work around them’. (GP6) |

| j |

System Value, understanding, support |

‘Maybe people who go into politics of general practice really have forgotten the basics. Yes, I think ‘naïve’ is the word. I don’t think they have a great idea of the day to day’. (GP10) |

| k |

System Value, understanding, support |

‘… With the vaccination programme … we weren’t regarded as frontline workers, and we did Covid testing. We treat people with respiratory illness. And so, that was kind of—I think that was a diminishing thing, really, apart from you know, not feeling protected’. (GP16) |

| l |

System Audits, complaints, liability |

‘This complaint, and all the other ones I've had, and other people I’ve seen … There should be some sort of triage system [within the HCCC, Health Care Complaints Commission] where the crap is weeded out, to reduce the stress on GPs, and other doctors, and save time. And at the same time not discouraging complainants, but perhaps it could be dealt with at a lower level’. (GP20) |

| m |

System Audits, complaints, liability |

‘The other thing that can affect you, is probably if you get a few patient complaints to HCCC and AHPRA, or to the board. That actually brings your morale down quite a lot. It’s one of the easiest things to complain against a doctor. You know, we’re all soft targets’. (GP13). |

| n |

System Patient expectations |

‘Patients think that they can come in, and see you, and have a great amount of things dealt with. And if you deal with three of the sixteen things, they walk away feeling unhappy, even though they’ve booked 15 minutes [consultation]’. (GP20) |

| o |

Finances System |

‘But the wellbeing that GPs achieve, is by their own measures, and they are to counteract the negative pressures that come from outside this [consult] room. So … the forces that are negative, are Medicare, and the way GPs are treated. Like the telehealth items are just going to be cut … ECGs [electro-cardiograms], that item was just cut. Joint injections, they were just cut’. (GP9) |

| p |

Finances Organisation |

So, [we are] private billing … with discretion, so that there will be some patients that, you know, we’ll bulk bill. But generally—And, I always have that mindset that I’m not going to undervalue myself. Otherwise, yeah, you know, yeah … And I think my patients have appreciated, that I do that extra bit for them and, you know, and they appreciate what they get. So, but I still will get occasional patients who will try [to get bulk billing]’. (GP15) |

| q |

Finances Organisation |

‘One of the things I like about a bulk billing practice, and it’s good, I think, for my wellbeing—I have worked at some practices that charge. I hated the stress at the end of every consult where someone would be saying, “Please, can you just bulk bill me”? or “I just can’t pay this week”. And honestly, it was a very stressful situation at the end of every consult …’ (GP2) |

| r |

Finances Personal |

‘Ahhm, I think GPs themselves hinder themselves. … I think doctors’ knowledge and understanding of Medicare, or GPs’, is often appalling. … They claim wrongly, they act poorly, they spend the public money poorly, and they’re scared of things they shouldn't be scared of, or conversely, they’re not scared of things they should be scared of. I think it’s GPs themselves, not Medicare. … It is ridiculous, because if you're a bulk billing GP your entire income is based on understanding that system, how can you possibly derive your income without understanding it? … There is tons of information, Medicare videos, tutorials, loads of stuff on there, regular webinars. GPs do not educate themselves, it’s their fault’. (GP4) |

| s |

Finances Personal |

‘And obviously, none of us get maternity leave from work. … So financially, it’s a huge source of stress, because—I’m lucky that my wife, who’s also a doctor, works in the hospital system. She’s put on and off about getting into general practice. Quite frankly, one of the things that puts her off is maternity leave and the thought of being completely unsupported by, you know, national government or any other organisation, if we were to take time off work’. (GP1) |

This table contains further verbatim quotes (overflow table) in addition to those embedded in the text.

Bulk billing, Medicare rebates cover practitioner charges (no out of pocket fees for patients); HCCC, Healthcare Complaints Commission; PHNs, Primary Care Networks.

However, several participants stated not (always) heeding the well-being advice they gave their patients.

… I’ve come to realise, actually, that what I’m imparting is good advice, but I need to follow it myself as well, because it does make sense, and it does improve my wellbeing as well. So, yeah, I think as GPs, I’m not sure we always do what’s right for ourselves, you know, compared to what we impart to our patients. (GP15)

A strong professional identity—defined by a sense of pride, duty, responsibility and high self-expectations—was ubiquitous (table 2c). GPs also saw themselves as high achieving, able and resilient (table 2d).

From an identity point of view, … being a doctor sometimes subsumes my identity, and it’s an important part of my identity. And therefore, my contentment at work and my recognition as a doctor, and the satisfaction I get at work impact on my identity as a doctor … (GP14)

Choosing variation in the type of work carried out was another determinant of keeping well, through avoiding monotony and isolation, deliberately taking on different roles, and by temporarily relinquishing the burden of patient responsibility (ie, having academic days, pursuing teaching and management, or assisting surgeons in theatre) (table 2e).

Aforementioned enablers of professional well-being were offset by a sense of being perceived as ‘less than’ a specialist by the system, the public, other doctors and often internalised by the GPs (table 2f).

Organisation

For the organisational (practice) theme, the most important factor determining personal well-being was team and peer support. This included mostly informal debriefs with colleagues about challenging patients, medical management, staff or personal issues, and was facilitated by organisational practices encompassing physical (eg, having a common tea-room), social (eg, protected breaks and collegial social activities), and work domains (eg, efficient practice management, routine workflow and infrastructure).

Ahh, having a good bunch of people to work with, people who are working together in an environment that is safe, there is timetabling of patients, that we are able to have a tea break, toilet break, lunch break, and be able to respond to patients’ needs as they arise, at the same time. That is important in a clinical setting. (GP3)

In contrast, GPs perceived working in competitive or negative team climates as highly detrimental to their well-being (table 2g). This was more often expressed by participants in metropolitan practices, where practices reportedly skimp on tea-rooms, and doctors routinely work through lunch breaks due to financial strains related to significantly higher living expenses than in regional/rural areas (table 2h). Effective practice leadership was helpful, whereas a lack of management understanding was detrimental.

High workload and the pressure to see patients, sometimes coupled with insufficient staffing were frequently cited as barriers to well-being.

… I feel that there is a real sausage factory sort of approach to it in Sydney. It’s just bang, bang, bang, go, go, go. (GP12)

Having a mentor or supervisor who modelled how to maintain personal well-being was seen as important to learning how to prioritise personal well-being, particularly for GP registrars.

… I think we need to be modelling. Because I think if people are going through the training and not experiencing any different, we shouldn’t be surprised that they then become like 30, 40, 50-year-old GPs who are totally burnt out, and have no sense of what’s actually important for their self-care. (GP12)

Profession

Determinants of well-being also originated from within the GP community, and their representative bodies.

Several GP trainees, and educators described that training organisations, and the college representing rural practitioners offered tangible support. Examples included providing vouchers for gym memberships, facilitating discussion rounds on GP trainee days about keeping well, and the importance of self-care.

However, most GPs were either only vaguely aware of college support resources for well-being, or were not interested.

… The college or the PHNs think they’re fabulous when they put on a wellbeing weekend—and there’s always a yoga class, you know, always a yoga class. I mean, what does that mean? That’s a token, and the wellbeing industry is—the corporate life is all about talking about people’s wellbeing, rather than providing real support. Communication, engagement, concern, yeah, the same as we look after our patients. And we don’t get looked after by anyone. (GP9)

Many interviewees were dissatisfied with their professional college because they felt ill-represented, or even that the college was actively working against them. Consequently, several participants withdrew their college membership (table 2i).

System

GPs’ views on the Australian health system varied, yet nobody was able to identify support for well-being within the system.

I’m not sure that there is anything from the system that supports my wellbeing … I think it’s up to you to look after yourself. (GP8)

The subtheme most frequently emphasised by GPs during the interviews was a sense of not being valued, and a lack of appreciation, respect and support.

And I think the government just think we are a disorganised bunch, and who we can just brush aside, and they will go the extra mile for their patients … Unless GPs get organised, and more militant, then we’re just going to be ground. (GP9)

Participants expressed, that others’ lack understanding of what a GP does on a daily basis, and the importance GPs play in the provision of population health (table 2j).

I think if more people had a concept of what general practice actually can do, and what it does, there would be a lot more respect. (GP17)

This lack of understanding was exemplified by limited GP consultation by the government concerning the COVID-19 response, and vaccination rollout (table 2k).

The fear of billing audits by Medicare (definition, online supplemental file 2), formal patient complaints (table 2l and m), litigation threats and bad media press compounded the lack of valuation.

Well, I think the Medicare audits—although I’ve been lucky enough not to receive an audit letter yet—I think that has sent … a whole load of fear through a lot of GPs who’ve tried to do the right thing. (GP11)

Over-specialisation (table 2f) and GP shortages, as well as working in silos, rather than hand in hand (ie, with other healthcare providers, between federal and state agencies) were mentioned by a small proportion of GPs.

Finally, GPs frequently encountered unrealistic expectations from patients, including to receive services for free (table 2n).

… You see a number of patients that basically see you as the local Coles [supermarket]. “OK, doctor, I need my prescription, and I need my referral …” And you know, you are just a dispensing machine, an ATM. And it doesn’t cost them anything because you are bulk billing. (GP14)

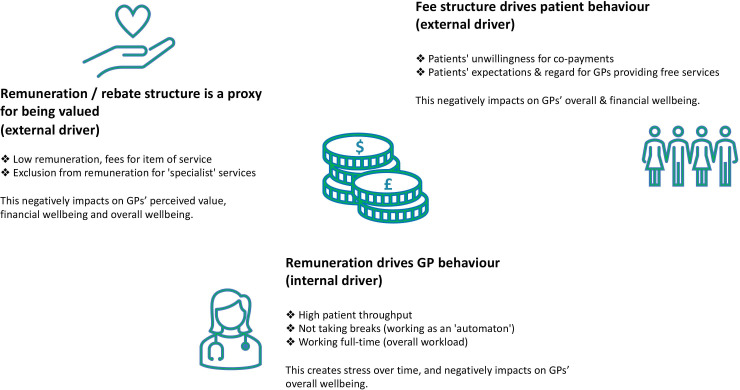

Finances

Financial aspects were interlinked with all themes, and directly and indirectly determined well-being (figure 2). First, Medicare rebate structure that determined fee for services (online supplemental file 2) was closely tied to a sense of being valued, and personal well-being. Second, fee structure drove patient behaviour, which impacted on GPs overall and financial well-being. And third, remuneration influenced GPs’ behaviour. In our sample, several GPs responded to low rebate structure and high patient expectations with increasing patient throughput and foregoing work breaks, with implications for their well-being.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of the negative impact of finances on the well-being of general practitioners (GPs).

Remuneration was perceived as a direct reflection of the value of a profession, a service, and a proxy for the outright value of a GP individually.

… To me, so, I’m really sort of fed up [with the Medicare rebate]—disillusioned with—where we’re at this stage, you know. And that, doesn’t help our wellbeing because we don’t—we feel undervalued. And the government has done nothing to really, you know, show any positive change in that respect. So definitely, and I don’t really know the way out of that, because, you know, even if they were to increase the rebate a small amount, it still doesn’t really reflect, you know, the amount of effort that we put into our patients, and the preventative side of things, I mean the amount of work we’re doing to prevent hospitalisations and, all of that sort of thing. (GP15)

GPs voiced frustration with the cutbacks of billable Medicare items (online supplemental file 2) crucial to general practice, and the impact that had on their well-being (table 2o).

GPs described two factors that influenced their income: the volume of patients seen; and how, and what they billed. High patient throughput was sometimes driven by practice owners, but more often by personal financial pressures. Particularly, when the GP was the main breadwinner, lived in a metropolitan area, and/or the practice bulk billed only, there was significant pressure to see as many patients as possible. For example, one participant saw over one thousand bulk billed patients per month. Some GPs charged patient gap payments above the Medicare rebate, to reflect the value they attributed to their expertise and services (table 2p). While others reported a reluctance to privately bill their patients, or unwillingness to argue with patients over charging the gap between private and bulk billing (table 2q).

‘Time is money’ was a frequently reported concept, which directly impacted on some GPs’ willingness to work less, and spend time on activities that they knew improved well-being, such as taking breaks, engaging in reflective practice, or attending peer review groups.

Fundamentally, I think the issue is … the way that we’re paid. And because we only generate billings when we’re seeing patients it just sort of warps your whole view of, you know, what’s worthwhile doing. (GP12)

According to one participant, GPs were ill-informed about Medicare’s billing structure available to general practice (table 2r). Indeed, several interviewees stated not being well versed or interested in financial management, so some deliberately engaged an accountant.

For GP registrars the financial pressures were compounded, as they are salaried, and remuneration is typically lower than for a fully qualified GP. Unpaid maternity leave was a relevant consideration (table 2s), however, high autonomy and flexible working arrangements were specifically stated by women as key benefits of going into general practice.

And I think that in general practice we’re lucky that we have somewhat well, we do have quite good control of our hours in that in that sense, particularly as a part time worker balancing a family at home. (GP19)

Overall, what was most striking, was the tension and complex balancing act required between all determinants, at the centre of which stood the individual GP. We did not observe a simplistic ‘work-life balance’, that is, predicted on reducing hours and demands at ‘work’ to enable more ‘life’. In this cohort much of GPs’ sense of self—and well-being—lay in how they viewed themselves professionally, including how they designed their working life.

Discussion

Summary

Determinants of well-being were qualitatively explored in the interviews. We presented five themes each with subthemes: identity/self, organisation, profession, system and finances. They are all are strongly interconnected, and each has several subthemes (see figure 1). GP well-being—or lack thereof—is a complex interplay between different determinants, and stakeholders. GPs provided examples of both enablers and barriers to their well-being. What clearly emerged is that enablers of well-being were mostly attributed to their personal lives, and for some, their immediate practices. A sense of pride in their abilities, performance, and resilience were key enablers of well-being. The main, underlying barriers—inadequate professional value and recognition—predominantly emanated from the system, and were underpinned by remuneration. GPs largely counter-balance barriers to well-being as best they can personally, and crucially, through informal peer support. When these mechanisms are exhausted or impossible, well-being quickly deteriorates. Furthermore, several GPs compensate low remuneration, inadequate professional recognition and high patient demand with means detrimental to their well-being (ie, by working harder, figure 2).

It is noteworthy, that without guidance or provision of a definition of well-being, many GPs tended to focus on aspects of the system as barriers, rather than enablers of well-being. This was likely due to significant systemic pressures, GPs’ perceived lack of agency regarding systemic and professional issues, and the frustration this causes. It may also be that GPs expect to look after themselves, or do not see how the system and professional bodies could bolster their well-being, for example, by codesigning organisational or policy interventions. Seen through this lens, it becomes clear that resilience and well-being seminars designed for individual practitioners will not suffice, nor be embraced, especially when they are offered by the very organisations and systems that GPs deem responsible for hindering their well-being.

Comparison with existing literature

Although GPs defined well-being in fairly limited ways they described components of affective well-being,32 psychological well-being36 and flourishing37 when discussing what promotes well-being on a personal and practice level (ie, social connections at work, autonomy and flexibility of work, sense of pride in their abilities). Interpreting the barriers to well-being is more complex. While, for example, remuneration and valuation are determinants of how one might appraise cognitive well-being, these seemed viewed as something that could only detract from well-being, that is, as drivers of burnout? If we conceptualise well-being as a distinct construct—although related to burnout, then the answer is likely more nuanced than both being directly opposing sides of the same spectrum. Could improving remuneration or valuation actually improve well-being? While some may see the answer as obvious (as life satisfaction continues to rise with income, although slowly at the income level of doctors34) this remains an empirical question.

We compared our findings with qualitative research on well-being, and related positive constructs such as satisfaction, and with selected quantitative research directly relevant to the Australian general practice landscape.

A UK group conducted focus groups with 25 GPs to identify factors that contribute to burnout and poor well-being, and strategies to improve both. Similar to our results, they identified the importance of team support, taking breaks, variety of and control over their work, on an internal level; and wider governmental and public support, resources and funding on an external level.40 British GP trainee focus groups (n=16) discussed the benefits of supportive professional relationships (ie, supportive trainers), control over workload and barriers to well-being of ‘not being valued’, and work-life imbalance.55 The European General Practice Research Network interviewed 183 GPs across eight countries, and described factors that promote job satisfaction: freedom to organise and choose their practice environment; professional education; and establishing strong patient–doctor relationships.56 Interestingly, patient–doctor relationships and professional education were not mentioned in our cohort. It was more a case of patient expectations being detrimental to well-being, and role modelling for registrars being useful. Female rural family doctors in the USA were interviewed regarding practice attributes that promote satisfaction, whereby supportive professional relationships were crucial.57 Our interviewees described the importance of professional peer support, and particularly women appreciated the autonomy and flexibility to choose when, and where to work.

In our interviews, stress of formal patient complaints and audits surfaced repeatedly. Similarly, a patients’ complaints culture, and defensive practice were also described as stressors in focus groups exploring GP resilience and coping.58

A systematic review thematically analysed studies broadly focusing on positive factors related to general practice. They discerned general medical workforce themes, general practice specific themes, and professional/personal issues impacting on GP satisfaction in clinical practice.59 Subthemes included balance between income and workload; flexibility, variety and freedom to choose work; responsibility, competency, recognition; positive self-image, personality and values; and relationships with community, patients, carers and other professionals.59 So overall, previous qualitative research in international contexts demonstrate alignment with our results, despite vastly different healthcare systems across countries.

Our data also shows similarities with Australian quantitative data on life and job satisfaction, particularly regarding remuneration, value and the strain of maintaining balance. The ‘Medicine in Australia—Balancing Employment and Life’ surveys, were conducted from 2008 to 2018 with annual participant numbers of >3000 GPs,12 60–67 furthermore the RACGP regularly commissions surveys, and reports.68 69 GPs are most satisfied with variety and choosing how to work, least satisfied with remuneration and recognition, and about half of surveyed GPs report that maintaining work-life balance is a challenge.66 68–70 Over several years, >40% of GPs have identified Medicare rebates as a top priority for policy action.68 Positive associations for job satisfaction in all doctor types include doctor characteristics (age close to retirement, Australian trained, good health); social characteristics (living with a partner, social interaction); and job characteristics (part-time work, opportunities for professional development, support networks, realistic patient expectations).62 63

Strengths and limitations

Strengths include the diversity of participants and their combined wealth of experience (table 1), which allowed for a broad exploration and analysis of multiple determinants of GP well-being, and their interconnections. Sample sizes in qualitative research are generally small (n=20 in this study), however, data saturation was reached.

Limitations include selection bias often inherent in qualitative research with voluntary participation. We purposely only included GPs working in Australia for practicability reasons, and local relevance. These results may not equally apply to GPs working elsewhere, different factors may be present for GPs in other countries, particularly around funding structures and policy.

There are many definitions and metrics of well-being in the literature,31 71 which adds complexity to research in this space. For quantitative studies a well-being definition and dedicated measure can and should be selected.31 41 We did not define well-being for our participants, but rather let them use their own conceptualisation, so as to not bias participants’ answers.

Mean interview duration was 32 min. Conducting longer interviews with busy GPs during a global pandemic was impossible. Ethnicity of participants was not recorded.

Implications for research and/or practice

To prioritise Australian GPs’ well-being, we need to understand the full breadth of determinants (enablers and barriers) of well-being, and how they interplay. Moving beyond individual well-being interventions, our data suggests why organisational, professional and systemic structures need to be targeted. This will require advocacy, commitment and funding. It will take careful planning by professional bodies, organisations and policy makers in collaboration with practitioners.

In terms of research implications, well-being must be clearly defined, it must be distinguished from burnout both when it comes to designing interventions, and selecting metrics to assess their effectiveness.

Strategies to advance well-being were discussed in the interviews, and are detailed in our subsequent publication.

Conclusion

GPs balance complex and interconnected determinants of well-being, whereby value, remuneration and peer support are crucial. Organisations, professional bodies and policy makers have an untapped opportunity to enable GPs’ well-being, with benefits to practitioners, their patients, the sustainability of the general practice workforce, and population health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, we would like to thank all participants for sharing their time and insights. We would like to acknowledge the support extended by the Central and Eastern Sydney Primary Health Network, New South Wales; the Murray Primary Health Network, Victoria; and Healius Pty Ltd, Australia.

Footnotes

Contributors: DN is the guarantor and corresponding author and attests that DN, NG, CK, LA, BG, IBH, AM meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. All authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. Specifically, DN devised, and contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis of the data, interpretation of the data, drafted the manuscript, finalised the manuscript for reporting and acts as corresponding author. NG contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis of the data, interpretation of the data, assisted in drafting the manuscript and revising the final manuscript for reporting. CK contributed to analysis of the data, interpretation of the data, assisted in drafting the manuscript and revising the final manuscript for reporting. LA contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of the data, assisted in drafting the manuscript and revising the final manuscript for reporting. BG contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, assisted in drafting the manuscript and revising the final manuscript for reporting. IBH contributed to the study conception and design, and revising the final manuscript for reporting. AM contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis of the data, interpretation of the data, assisted in drafting the manuscript and revising the final manuscript for reporting.

Funding: DN was supported through the Raymond Seidler PhD scholarship. The funding source had no influence on the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript nor the decision to submit the article for publication. Award/Grant number is not applicable. This research was supported (partially or fully) by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council's Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (Project ID CE200100025). The funding source did not have any influence on the design or conduct of this research.

Competing interests: Beyond the Raymond Seidler PhD scholarship for DN, and support for NG, AM and CK through ARC’s Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course (Project ID CE200100025) there was no support from any organisation for the submitted work. Ian Hickie has competing interests to declare. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. We will consider sharing de-identified data upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research and Ethics Committee (2020/822).

References

- 1.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573–6. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spinelli WM. The phantom limb of the triple aim. Mayo Clin Proc 2013;88:1356–7. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet 2009;374:1714–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn PM, Arnetz BB, Christensen JF, et al. Meeting the imperative to improve physician well-being: assessment of an innovative program. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1544–52. 10.1007/s11606-007-0363-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luchterhand C, Rakel D, Haq C, et al. Creating a culture of mindfulness in medicine. WMJ 2015;114:105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Australian Government, Department of Health . National Medical Workforce Strategy - Investing in our medical workforce to meet Australia’s health needs 2021.

- 7.Australian Government, Department of Health . National medical workforce strategy - scoping framework. Canberra 2019.

- 8.Addicott R, Maguire D, Honeyman M, et al. Workforce planning NHS kings fund. London: The King’s Fund, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nussbaum C, Massou E, Fisher R, et al. Inequalities in the distribution of the general practice workforce in England: a practice-level longitudinal analysis. BJGP Open 2021;5:66 10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abel GA, Gomez-Cano M, Mustafee N, et al. Workforce predictive risk modelling: development of a model to identify general practices at risk of a supply-demand imbalance. BMJ Open 2020;10:e027934. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandhu D, Blythe A, Nayar V. How can medical schools create the general practice workforce? An international perspective. MedEdPublish 2020;9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott A. The evolution of the medical workforce. ANZ health sector report: Melbourne Institute: applied economic and social research, the University of Melbourne 2021.

- 13.Scott A, Witt J, Humphreys J, et al. Getting doctors into the bush: general practitioners' preferences for rural location. Soc Sci Med 2013;96:33–44. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deloitte . General practitioner workforce report. Deloitte access economics 2019.

- 15.Scott A. The impact of COVID-19 on GPs and non-GP specialists in private practice. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.RACGP . The Royal Australian College of general practitioners. annual report 2019–20. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.RACGP . GP wellbeing Royal Australian College of general practitioners website, 2021. Available: https://www.racgp.org.au/running-a-practice/practice-management/gp-wellbeing

- 18.Harvey SB, Epstein RM, Glozier N, et al. Mental illness and suicide among physicians. Lancet 2021;398:920–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01596-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petrie K, Crawford J, Baker STE, et al. Interventions to reduce symptoms of common mental disorders and suicidal ideation in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:225–34. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30509-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016;388:2272–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med 2018;283:516–29. 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J. How to prevent burnout in cardiologists? A review of the current evidence, gaps, and future directions. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2018;28:1–7. 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1317–30. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 24.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:195–205. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley R, Spiers J, Buszewicz M, et al. What are the sources of stress and distress for general practitioners working in England? A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e017361. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kay M, Mitchell G, Clavarino A. What doctors want? A consultation method when the patient is a doctor. Aust J Prim Health 2010;16:52–9. 10.1071/py09052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay M, Mitchell G, Clavarino A, et al. Doctors as patients: a systematic review of doctors' health access and the barriers they experience. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:501–8. 10.3399/bjgp08X319486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kay M, Mitchell G, Clavarino A, et al. Developing a framework for understanding doctors' health access: a qualitative study of Australian GPs. Aust J Prim Health 2012;18:158–65. 10.1071/PY11003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clough BA, March S, Leane S, et al. What prevents doctors from seeking help for stress and burnout? A mixed-methods investigation among metropolitan and regional-based Australian doctors. J Clin Psychol 2019;75:418–32. 10.1002/jclp.22707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiers J, Buszewicz M, Chew-Graham CA, et al. Barriers, facilitators, and survival strategies for GPs seeking treatment for distress: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e700–8. 10.3399/bjgp17X692573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linton M-J, Dieppe P, Medina-Lara A. Review of 99 self-report measures for assessing well-being in adults: exploring dimensions of well-being and developments over time. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010641. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diener E. Assessing subjective well-being: progress and opportunities. Soc Indic Res 1985;31:103–57. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kettlewell N, Morris RW, Ho N, et al. The differential impact of major life events on cognitive and affective wellbeing. SSM Popul Health 2020;10:100533. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris RW, Kettlewell N, Glozier N. The increasing cost of happiness. SSM Popul Health 2021;16:100949. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diener E, Ng W, Harter J, et al. Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. J Pers Soc Psychol 2010;99:52–61. 10.1037/a0018066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;57:1069–81. 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seligman M. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. J Posit Psychol 2018;13:333–5. 10.1080/17439760.2018.1437466 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Murray MA, Cardwell C, Donnelly M. GPs' mental wellbeing and psychological resources: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e547–54. 10.3399/bjgp17X691709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray M, Murray L, Donnelly M. Systematic review of interventions to improve the psychological well-being of general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:36. 10.1186/s12875-016-0431-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hall LH, Johnson J, Heyhoe J, et al. Strategies to improve general practitioner well-being: findings from a focus group study. Fam Pract 2018;35:511–6. 10.1093/fampra/cmx130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naehrig D, Schokman A, Hughes JK, et al. Effect of interventions for the well-being, satisfaction and flourishing of general practitioners-a systematic review. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046599. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V, Clarke V. What can thematic analysis offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:26152. 10.3402/qhw.v9.26152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol 2017;12:297–8. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological 2012:57–71.

- 46.Archer M, Bhaskar R, Collier A. Critical realism: essential readings, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barry CA, Britten N, Barber N, et al. Using reflexivity to optimize teamwork in qualitative research. Qual Health Res 1999;9:26–44. 10.1177/104973299129121677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandelowski M, Docherty S, Emden C. Focus on qualitative methods. Sample size in qualitative research Research in Nursing & Health 1995;18:179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rice PL, Ezzy D. Qualitative research methods: a health focus. Melbourne, Australia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fusch P, Ness L. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. TQR 2015;20:1408–16. 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health 2010;25:1229–45. 10.1080/08870440903194015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.NVivo 12: QSR international Pty Ltd, 2020. Available: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- 54.O’Connor C, Joffe H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: debates and practical guidelines. Int J Qualit Method 2020;19. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ansell S, Read J, Bryce M. Challenges to well-being for general practice trainee doctors: a qualitative study of their experiences and coping strategies. Postgrad Med J 2020;96:325–30. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2019-137076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Le Floch B, Bastiaens H, Le Reste JY, et al. Which positive factors give general practitioners job satisfaction and make general practice a rewarding career? a European multicentric qualitative research by the European general practice research network. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:96. 10.1186/s12875-019-0985-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hustedde C, Paladine H, Wendling A, et al. Women in rural family medicine: a qualitative exploration of practice attributes that promote physician satisfaction. Rural Remote Health 2018;18:4355. 10.22605/RRH4355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheshire A, Ridge D, Hughes J, et al. Influences on GP coping and resilience: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e428–36. 10.3399/bjgp17X690893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Le Floch B, Bastiaens H, Le Reste JY, et al. Which positive factors determine the GP satisfaction in clinical practice? A systematic literature review. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:133. 10.1186/s12875-016-0524-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scott A. The impact of COVID-19 on GPs and non-GP specialists in private practice. Applied Economic & Social Research, The University of Melbourne. Melbourne Institute, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott A. General practice trends. The University of Melbourne, Melbourne: Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joyce C, Wang WC. Job satisfaction among Australian doctors: the use of latent class analysis. J Health Serv Res Policy 2015;20:224–30. 10.1177/1355819615591022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joyce CM, Schurer S, Scott A, et al. Australian doctors' satisfaction with their work: results from the MABEL longitudinal survey of doctors 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Joyce CM, Scott A, Jeon S-H, et al. The "medicine in Australia: balancing employment and life (MABEL)" longitudinal survey--protocol and baseline data for a prospective cohort study of Australian doctors' workforce participation. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:50. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rodwell J, Gulyas A. A taxonomy of primary health care practices: an avenue for informing management and policy implementation. Aust J Prim Health 2013;19:236–43. 10.1071/PY12050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shrestha D, Joyce CM. Aspects of work-life balance of Australian general practitioners: determinants and possible consequences. Aust J Prim Health 2011;17:40–7. 10.1071/PY10056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Medicine in Australia . Balancing employment and life, Australia’s national longitudinal survey of doctors: Melbourne Institute, University of Melbourne, 2021. Available: https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/mabel/home

- 68.RACGP . General practice: health of the nation 2020. East Melbourne, Vic: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 69.RACGP GP survey. Melbourne: EY Sweeney 2020.

- 70.McGrail MR, Humphreys JS, Scott A, et al. Professional satisfaction in general practice: does it vary by size of community? Med J Aust 2010;193:94–8. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03812.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dodge R, Daly A, Huyton J, et al. The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing 2012;2:222–35. 10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-058616supp001.pdf (148.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. We will consider sharing de-identified data upon reasonable request.