Abstract

Background

Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care (EPAC) is a model that helps shift the culture in long-term care (LTC) so that residents who could benefit from palliative care are identified early. Healthcare Excellence Canada supported the implementation of EPAC in seven teams from across Canada between August 2018 and September 2019.

Objective

To identify effective strategies for supporting the early identification of palliative care needs to improve the quality of life of residents in LTC.

Intervention

Training methods on the EPAC model included a combination of face-to-face education (national and regional workshops), online learning (webinars and access to an online platform) and expert coaching. Each team adapted EPAC based on their organisational context and jurisdictional requirements for advance care planning.

Measures

Teams tracked their progress by collecting monthly data on the number of residents who died, date of their most recent goals of care (GOCs) conversation, location of death and number of emergency department (ED) transfers in the last 3 months of life. Teams also shared their implementation strategies including successes, barriers and lessons.

Results

Implementation of EPAC required leadership support and dedicated time for changing how palliative care is perceived in LTC. Based on 409 resident deaths, 89% (365) had documented GOC conversations; 78% (318) had no transfers to the ED within the last 3 months of life; and 81% (333) died at home. A monthly review of the results showed that teams were having earlier GOC conversations with residents. Teams also reported improvements in the quality of care provided to residents and their families.

Conclusion

EPAC was successfully adapted and adopted to the organisational contexts of homes participating in the collaborative.

Keywords: Palliative Care, Quality improvement, Long-Term Care, Patient-centred care, Implementation science

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Many people would prefer to be cared for in the familiarity and comfort of their own home if they have access to the support they need at the end of their life. However, few Canadians have early access to palliative care in their community.

People who receive palliative care at home or in long-term care (LTC) in their last year of life are more likely to die in their residence and less likely to visit emergency departments.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care (EPAC) model required leadership support and dedicated time for changing how palliative care is perceived in LTC.

EPAC contributed to earlier goals of care conversations and improvements in the quality of care provided to residents and their families in LTC.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

EPAC was successfully adapted and adopted to the organisational contexts of LTC homes across Canada participating in the collaborative.

It is important to explain not only how to implement the EPAC model but also the value of the gift of time in palliative care by sharing personal stories with loss and grief to emphasise the ‘why’ behind the collaborative.

Introduction

Problem description

While there have been improvements in the provision of palliative care in Canada, there are still gaps in accessing quality palliative care in the community, specifically at home or in long-term care (LTC).1 Many people would prefer to be cared for in the familiarity and comfort of their own home if they have access to the support they need at the end of their life. People who receive palliative care at home or in LTC in their last year of life are more likely to die in their residence and less likely to visit emergency departments (EDs). However, few Canadians have early access to quality palliative care in their community.2 The Conference Board of Canada projected the demand for LTC will nearly double by 2035, specifically for people aged 75 and up, suggesting more people are likely to live their final years in LTC homes as Canada’s population ages.3 Identifying the palliative care needs of residents in LTC goes beyond advance care planning, which is focused on preparing residents and their substitute decision makers for future decision making. Goals of care (GOCs) have a broader focus on the resident’s goals for living and how LTC staff can support these goals to improve the quality of life of residents, including preference to receive care in their LTC home where appropriate.

Available knowledge

The profile of LTC residents includes complex health conditions, multiple comorbidities, and cognitive impairment or dementia.4 As the current average length of stay (LOS) in LTC is 18 months, palliative care services should ideally be initiated at the time of moving into the home.5 A model is needed on how to provide quality palliative care in LTC based on the Canadian context.6 A recent scoping review identified various models that ranged from referring residents to external specialists to building capacity within the home to provide palliative and end-of-life care. The ‘in-house’ model broadens the access to palliative care to everyone living in the LTC home. The success of this model relies on supportive leaders and team champions, knowledgeable and skilled staff, and continuous learning to improve the home’s approach to palliative care.7

Rationale

Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care (EPAC) was a model of care developed at Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) in British Columbia. It was generated based on the barriers to enabling well-planned and coordinated palliative care for people in LTC homes in the VCH region. Identifying palliative care needs early is referred to as the ‘gift of time’ that LTC staff can offer to residents and the people that are important to them. The gift of time promotes earlier GOC conversations about things that matter to residents and provide permission for collaborative planning and saying goodbye in a meaningful way. GOC conversations ensure that the care provided in LTC is guided by a resident’s values, contributing to increased comfort, better quality of life and satisfaction with care. Improvements to the quality of life of residents refer to positive changes as a result of the palliative care received, including adequate pain and symptom management, psychosocial care, sense of control, clear decision making and avoidance of aggressive care.8

Healthcare Excellence Canada (HEC, the new organisation that brings together the Canadian Patient Safety Institute and Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement) led a 12-month quality improvement collaborative to support the implementation of EPAC in LTC homes across Canada in 2018–2019. The main rationale for the EPAC collaborative was to support the spread and scale of early identification of palliative care needs to improve the quality of life of residents and evaluate the impact of this palliative care model in a broader context using HEC’s quality improvement framework.

Specific aims

The goal of the EPAC collaborative was to change the culture in LTC so that death, palliative care and quality of life are freely discussed with residents and their family members. This goal was achieved by (1) improving the ability of staff to have effective, timely goals of care (GOCs) discussions with residents and their substitute decision makers; (2) improving the quality of palliative care for residents and families; and (3) improving capacity to provide palliative care in the location of the resident’s choice and reducing unnecessary hospital transfers.

Methods

Context

HEC supported implementation of the EPAC model in seven teams from Québec (1), Alberta (1), Ontario (2), New Brunswick (1), Newfoundland and Labrador (1) and the Yukon (1) between August 2018 and September 2019. Each team received $30 000–$45 000 in seed funding to support the implementation of EPAC.

Intervention

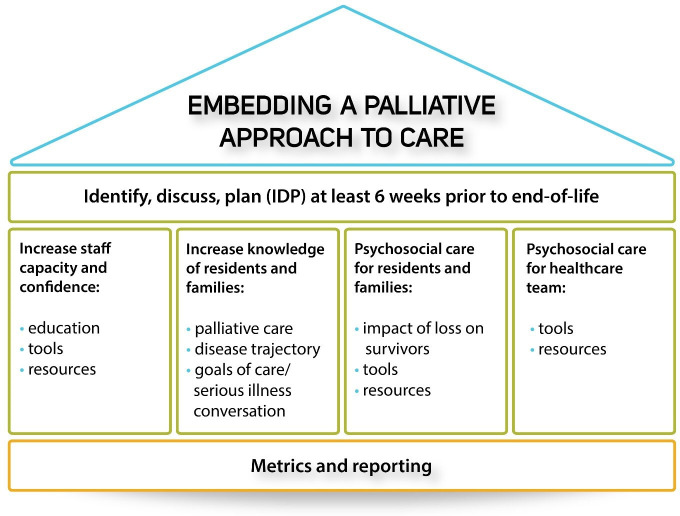

Teams were trained to use a continuous cycle to identify, discuss and plan (IDP) GOC discussions with residents at least 6 weeks prior to end of life. The IDP process is supported by the following four EPAC pillars (figure 1): (1) increase capacity and confidence of staff, (2) increase knowledge of residents and families, (3) provide psychosocial care for residents and families, and (4) provide psychosocial care for healthcare teams.

Figure 1.

Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care pillars.

HEC led several knowledge sharing activities to support each team to adapt the EPAC model based on their organisational context and exchange lessons learnt. This included eight regional workshops to train over 200 healthcare providers from the seven participating teams between September and December 2018, a national bilingual workshop in Ottawa at the mid-implementation phase of the collaborative (March 2019) to facilitate peer-to-peer learning, and 10 bilingual webinars on quality improvement (change management, resident and family engagement, and culture change) and palliative care strategies (spirituality, psychosocial support, dementia and medication management). In addition, teams had access to an online learning platform that included more than 40 educational resources including resources that teams had developed and/or adapted to implement EPAC in their home. Teams also received tailored support from HEC staff and four contracted coaches. Fifteen coaching calls were completed during the EPAC collaborative to provide an update on progress, share challenges and obtain guidance.

Study of the intervention

A mixed methods approach was used to collect qualitative and quantitative data from all seven teams on their implementation experience and the impact of the EPAC model between August 2018 and September 2019.

Measures

The EPAC collaborative included several, common measures to understand how the teams implemented the four EPAC pillars and their impact on the EPAC collaborative aims. A supplementary document outlines the data sources collected from the teams for each of these components in more detail (online supplemental material 1).

bmjoq-2021-001581supp001.pdf (42.4KB, pdf)

Implementation

Each of the seven teams provided qualitative and quantitative data on their implementation strategies including successes, barriers and lessons learnt: (1) pre/post primarily quantitative, implementation surveys circulated to project leads (and site leads where applicable) to identify their top perceived barriers and facilitators for implementing EPAC (pre-implementation: 21 responses, and post implementation: 14 responses), (2) a final report completed by project leads containing primarily qualitative data summarising implementation results and lessons learnt (seven reports), and (3) one poster (mid-implementation) and two presentations (mid and post implementation) prepared by each of the seven teams using templates provided by HEC to describe their objectives, implementation strategies, successes and challenges.

Impact

Qualitative and quantitative data were also collected from each of the seven teams to evaluate the impact on the EPAC collaborative aims: (1) a final, quantitative survey for team members who participated in at least one of HEC’s learning activities (webinars, workshops and coaching calls) to rate their knowledge and skills in palliative care before and after their participation in the EPAC collaborative (47 responses); (2) the previously referenced pre-implementation/post implementation surveys, which also asked respondents to rate the effectiveness of palliative care conversations with residents and families; and (3) the previously referenced final reports and team posters/presentations, which included reflections from staff on culture change in their LTC home and impact stories/quotes from families. Teams obtained feedback from families using satisfaction surveys, focus groups, informal discussions and/or ‘thank you’ cards.

Teams were also supported to track their progress by submitting deidentified, site-level data monthly between August 2018 and September 2019: date of admission, date of the first GOC conversation, date of the most recent GOC, date of death, location of death, and number of ED transfers and hospital admissions (via ED or direct transfer) in the last 3 months of life (including reason for transfer). HEC shared aggregate data during workshops and webinars for continuous improvement and prepared a summary of team-level data with recommendations at the end of the collaborative.

Analysis

A deductive approach was used to analyse the qualitative data from the surveys, presentations, posters and reports. These data were coded using NVivo to identify common themes on the implementation and impact of the EPAC collaborative. The four EPAC pillars provided a framework for coding, analysing and interpreting the implementation results where teams adapted the EPAC model based on organisational needs (figure 1). The three aims of the EPAC collaborative outlined in the Introduction provided a framework for reviewing the impact results. Two of the authors were involved in the coding and analysis of the data.

Descriptive analysis was completed on the quantitative data from the surveys and monthly data submissions using percentages and/or averages as appropriate. A paired sample t-test was performed to determine whether the average differences between the knowledge and skills of the respondents in palliative care before/after the EPAC collaborative were significant.

The results from the surveys were cross-referenced with the final reports where applicable to validate the findings, specifically the relationship between knowledge, skills and level of comfort of staff with GOC conversations and the staff’s perceived effectiveness of GOC conversations with residents and families.

Results

Implementation

Adaptation of the EPAC model

HEC supported teams in adapting each of the four EPAC pillars based on their local context. Teams engaged relevant stakeholders within their organisation (ie, resident representatives/family members, personal support workers, nursing staff, social workers, physicians and senior leadership) to support the implementation of the EPAC model. This included embedding palliative care into orientation materials, integrating palliative care discussions into existing processes (eg, resident moving-in agenda, amendments to care planning discussions, and using common assessment tools for GOC and the decision-making capacity of residents) and having palliative medication order sets for physicians.

Pillar 1: increase capacity and confidence of staff

Teams used a variety of education methods to support staff to identify palliative care needs, to have early GOC conversations with residents and families, and to implement effective palliative care plans. Implementation strategies included assessing staff comfort levels, maintaining awareness of the importance of palliative care conversations (eg, regular meetings, staff huddles and staff retreats), making palliative care education mandatory for staff and having access to experts in palliative care to provide mentorship. Learning methods included dedicated training sessions, developing (or using existing) palliative care resources and ensuring that the programme was linked to materials available within their jurisdiction.

Pillar 2: increase knowledge of residents and families

Teams raised awareness of the importance of GOC conversations and the value of palliative care with residents and families by referring to illness trajectory pamphlets and posters, revising ‘moving-in’ checklists to initiate early GOC conversations and integrating palliative care into resident handbooks. Strategies for engagement with residents and families were a common theme for discussion in the team coaching calls. Teams shared the following examples:

We hosted a family information session where one of the topics was having conversations about goals of care and end-of-life care.

We created individual posters based on common myths [about palliative care] to support knowledge sharing with residents and families.

Pillar 3: provide psychosocial care for residents and families

One of the core components of the EPAC model was encouraging teams to ask residents and families how they wanted to be notified about resident deaths and how they wanted to be honoured and remembered. In addition to honouring the death of a resident, teams also identified specific strategies to support families and other residents after their loss. Examples included providing access to grief counselling, preparing comfort carts for families, providing a comfortable and private space for grieving, and writing sympathy cards. Teams shared the following feedback from families as examples:

Opening ceremony to all faiths, including First Nations, Inuit and Metis, to engage spiritual leaders/supports within the community.

Working to ensure that residents have one to one support and monitor resident wellbeing.

Pillar 4: provide psychosocial care for healthcare teams

Another key component of the EPAC model was encouraging teams to ask staff what kinds of support mechanisms they would find most helpful and how they would like to be notified about resident deaths. Teams used creative methods to honour residents who died by offering dedicated memorial areas (eg, garden, shelf with memorable pictures and reflection room) and services (eg, lighting a candle, sending a condolence card to the family and sharing stories at resident council meetings). Teams shared the following examples:

Forming an honour guard has helped with honouring the deceased residents and providing greater psychological support to the existing residents, families, staff and volunteers.

Implemented staff huddles 24 hours after death to remember and express emotions among staff.

In addition to honouring deceased residents, teams supported staff following the death of a resident through employee assistance programmes, peer support and debriefing sessions for staff to express their emotions and ask questions in a safe and supportive space.

Facilitators and barriers

Facilitators

The top five implementation facilitators based on 14 responses from project/site leads consisted of ‘effective clinical leadership’ (11, 79%), ‘existing palliative care programme’ (10, 71%), ‘staff engagement’ (9, 64%), ‘existing policies and procedures to support palliative care’ (9, 64%) and ‘existing good collaborative practice’ (8, 57%). These results highlighted multiple factors that facilitated the implementation of EPAC, including having leadership support and an existing strategy for palliative care. This is in line with long-term success factors for quality improvement to demonstrate leadership support and alignment with organisational priorities.9

Barriers

A common barrier noted by teams was having more time to implement the EPAC model as reflected in the top five implementation barriers: ‘clinical champion is an added role’ (7, 50%), ‘lack of capacity to undertake quality improvement projects’ (6, 43%), ‘changing culture’ (6, 43%), ‘GOC documentation issues’ (6, 43%), and ‘lack of understanding of how and when to implement palliative care’ (6, 43%). As the premise of the EPAC model was to promote shared responsibility for palliative care, some of the challenges noted by teams were staff buy-in, lack of comfort with GOC discussions and uncertainty about role responsibility. For example, teams shared that an allied health provider group was perceived as the ‘keepers of end-of-life conversations’.

Impact

The overall goal of implementing the EPAC model in LTC homes was culture change so that death, palliative care and quality of life are freely discussed as demonstrated by early and frequent GOC conversations with residents and families. As referenced earlier in the report, changing culture was identified as one of the top five barriers for implementing the EPAC model. Reflections from teams on the impact of the EPAC collaborative on organisational culture included changes in the perception of palliative care and increases in knowledge and skills of staff members. Teams reported increased focus on resident-centred care, earlier and more frequent GOC discussions, and improved team collaboration and staff engagement. The following quotes from two of the project leads captured the heart of the culture change required in LTC.

Thinking about our own end-of-life phase made us realize that our practices were built around our organizational objectives and that it is imperative to recalibrate our aim to focus on the resident’s wishes - the things that really matter in life.

I am sure that this awareness will lead to changes to our culture and approach. Jane’s presentation had a significant impact on me, it changed me and helped me grow. I would like to offer this gift to our residents by spreading this message of change to more people.

Aim 1: improving the ability of staff to have effective, timely GOC discussions

The first aim of the EPAC collaborative was to increase the knowledge and skills of staff in palliative care so that they are more comfortable initiating effective GOC discussions with residents ideally when they first move into the home.

Staff capacity and confidence

Teams rated their knowledge and skills before and after their participation in the EPAC collaborative on a scale from 1 to 10 (one being the lowest score). The average score shows an increase in knowledge and skills for all the items based on 47 responses from seven teams (table 1). The item with the highest increase for both knowledge and skills was ‘earlier identification of residents’. A paired sample t-test was performed to compare the average scores of respondents in terms of knowledge and skills on earlier identification of residents before and after the EPAC collaborative. There were significant differences in knowledge before (M=5.17, SD=4.87) and after (M=8.26, SD=2) (t(41)=−8.96, p<0.001), and skills before (M=5.73, SD=4.85) and after (M=8.02, SD=2.32) (t(40)=−6.99, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Knowledge and skills before/after the Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care collaborative (average score)

| Knowledge | Skill | |||

| Before | After | Before | After | |

| Earlier identification of residents | 5.2 | 8.3 | 5.7 | 8 |

| Difficult conversations | 5.5 | 8.1 | 5.6 | 7.9 |

| Respecting resident’s wishes | 5.7 | 8 | 6 | 8.1 |

| Psychosocial support | 5.6 | 7.8 | 5.8 | 7.9 |

| Plan for the usual trajectories of care | 5.5 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 7.5 |

| Quality improvement methods | 5.7 | 7.5 | 5.6 | 7.4 |

| Resident and family engagement | 5.4 | 8.3 | 5.5 | 7.6 |

| Interdisciplinary teamwork | 5.4 | 8 | 6.3 | 8 |

| Change management | 5.5 | 7.8 | 5.7 | 7.7 |

These results are validated in the final reports where the project leads noted an increase in the capacity and comfort of staff to have GOC conversations with residents and families through learning activities.

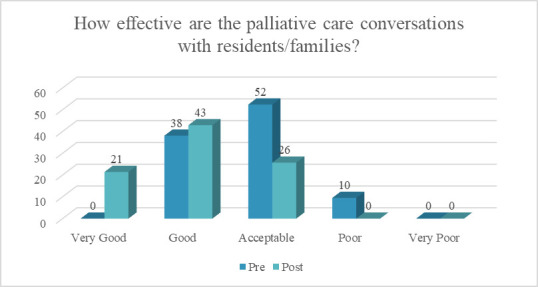

Effectiveness of GOC discussions

The respondents to the pre-implementation/post implementation surveys (project/site leads) reported an improvement in the effectiveness of the palliative care conversations with residents and families (figure 2). The percentage of respondents who indicated that the GOC discussions were ‘very good’/‘good’ increased from 38% (8/21) to 64% (9/14). Improving staff capacity and confidence may have contributed to more effective GOC discussions as evidenced by teams reporting the following as examples: ‘Staff have become more confident when speaking of palliative care with families. They’re having these conversations earlier and more regularly’, and ‘Some staff have felt more empowered to care for dying residents and grieving families and have been provided with resources to assist during these times’.

Figure 2.

Pre-implementation/post implementation survey results (%).

These precomparisons/postcomparisons demonstrate that the learning activities (eg, workshops, webinars and coaching calls) contributed to increases in the knowledge and skills of staff in palliative care, which resulted in more effective conversations with residents and families. The linkage between knowledge, confidence and competence seems to be a common finding in quality improvement initiatives.10 11

Timing of GOC discussions

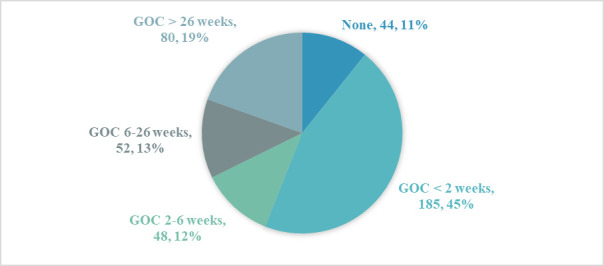

Teams reported that improvements in staff confidence helped staff initiate GOC conversations earlier and more often with residents and their families. Teams had also improved their organisational practices to better integrate palliative care into their moving-in process. This contributed to most resident deaths having documented GOC at the time of their death (n=365, 89%) and that more than half of the residents had their GOC reviewed at least once before their death (n=252, 62%).

There was some variability in the timing of these conversations (figure 3). Based on the VCH experience, teams were encouraged to have GOC conversations at least 6 weeks before death to allow enough time for planning with residents and families and avoid end-of-life care decisions during ‘crisis’ situations. In the pan-Canadian collaborative, approximately half of the residents had GOC conversations less than 2 weeks before death (n=185, 45%). However, these conversations were a review of the initial GOC for most of these residents (n=162/185, 88%). The timing of GOC for 12% (n=48) of the residents was 2–6 weeks before death; that for 13% (n=52) was between 6 and 26 weeks; and that for 19% (n=80) was more than 26 weeks before death (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of resident deaths with GOC (August 2018–September 2019). GOC, goal of care.

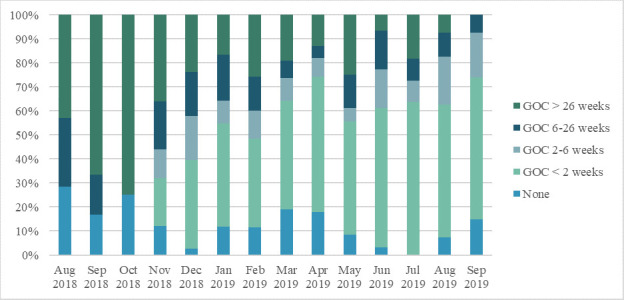

The overall GOC results in figure 3 were analysed by month to identify any trends during the collaborative. There were some improvements in the timing of GOC during the collaborative as indicated in figure 4 (August 2018–September 2019). There was a gradual increase in the percentage of residents with GOC less than 26 weeks before death, and a decrease in the percentage of residents with GOC more than 26 weeks before death, indicating teams were having earlier GOC with residents. This suggests teams were effectively identifying residents at high risk of death and prioritising these residents for the initial GOC conversations.

Figure 4.

Percentage of resident deaths with GOC by month. GOC, goal of care.

These results are limited to the monthly data reported by teams on resident deaths. The average LOS of residents for all teams was 4 years, while the duration of the EPAC collaborative was 12 months. Given that teams had updated their organisational practices to include GOC conversations as part of the moving-in process, it will take some time before the full impact of the EPAC model can be evaluated based on resident death data.

Aim 2: improving the quality of palliative care for residents and families

The second aim of the EPAC collaborative was to improve the quality of end-of-life care for residents and families. While location of death is an important quality measure, it does not consider the quality of care provided by staff.12 Teams reported improvements in quality of life of residents, including increased and improved communication and conversations about GOC, death and dying. Residents and families provided positive feedback about the team’s compassionate approach to palliative care and reported that they were comfortable asking questions and making decisions about their care in a safe and supportive environment. These quotes were received from family members describing the quality of care that their mothers had received:

My mother truly received the best end-of-life care possible from both attendants and nurses. The entire staff was so extraordinary. We’ll always think of these three words when we look back on our mother’s experience: respect, dignity and love.

I am truly grateful for the loving kindness and respect you all showed my Mum. It is such a comfort that she was surrounded by such wonderful caring people right to the end. She would have loved to receive a 100th birthday card from the Queen, but she at least was treated like royalty.

Aim 3: respecting the resident’s choice to die at home

The third aim of the EPAC collaborative was to improve staff capacity to provide end-of-life care in the location of the resident’s choice and to reduce unnecessary visits to the ED. The results were based on a sample size of 409 residents (ie, number of reported resident deaths).

Less than a quarter of resident deaths occurred in the hospital (19%, 76). Approximately 78% (318) of resident deaths happened without any transfers to the ED within the last 3 months of life. During the collaborative, 19% (n=76) of resident deaths occurred in the hospital, and 22% (n=91) of residents were transferred to the ED at least once within the last 3 months of life (table 2). The top five reasons for transfers to the ED included ‘injuries from falls’, ‘hypoxia’, ‘stroke’, ‘shortness of breath’ and ‘general health decline’. Depending on the wishes of the resident, some of these ED transfers could have potentially been avoided and managed by staff at home, specifically transfers related to general health decline. Teams were provided with a chart audit tool to assist in case review to analyse care provided, including reasons for hospital transfer, and to identify opportunities for improvement.

Table 2.

Percentage of resident deaths by location and number of ED visits

| Deaths at home | Deaths in the hospital | Total | |||

| No GOC | GOC | No GOC | GOC | ||

| Resident deaths with no ED visits (last 3 months of life) | 7% (30) | 59% (240) | 2% (10) | 9% (38) | 78% (318) |

| Resident deaths with +1 ED visits (last 3 months of life) | 0% (2) | 15% (61) | 0% (2) | 6% (26) | 22% (91) |

| Total | 8% (32) | 74% (301) | 3% (12) | 16% (64) | 100% (409) |

ED, emergency department; GOC, goal of care.

While most resident deaths had documented GOC (n=365, 89%), there were differences in the timing of these conversations between residents who died at home with no ED visits in the last 3 months of life and residents who died in the hospital with at least one ED visit (table 3). On average, the first group had the GOC discussion 35 weeks before death compared with the latter group where this discussion happened at 78 weeks. The length of time between the most recent GOC and time of death is almost double for residents who died in the hospital compared with those who died at home. Their GOC discussion may have been completed as part of the moving-in process but not reviewed more recently following readmission and/or changes in the resident’s condition. This suggests that GOC conversations not only need to happen earlier but also should be reviewed regularly and specifically when there are changes in the resident’s condition.

Table 3.

Comparison of GOC timing by location of death, number of ED visits and LOS

| LOS (years) | Average GOC timing in weeks | |

| Residents who died at home with no ED visits within the last 3 months of life (n=240) |

Residents who died in the hospital with at least one ED visit within the last 3 months of life (n=26) | |

| 0–2 | 6 | 19 |

| 3–5 | 21 | 33 |

| +5 | 88 | 304 |

| All | 35 | 78 |

ED, emergency department; GOC, goal of care; LOS, length of stay.

Discussion

Summary

Implementing a new intervention in LTC relies on successfully changing the perceptions and behaviours of staff.13 Success factors include adapting the intervention to the organisational context, providing dedicated resources and highlighting the impact of the intervention on resident outcomes.14 Implementing the EPAC model in LTC is a complex intervention that required a multifaceted approach which included the identification of stakeholders and champions, ongoing education and training, communication, consistent use of clinical assessment tools and documentation, integration of GOC discussions into the moving-in process, and regular touch-points with family members and residents.

Table 4 summarises key takeaways. The collaborative provided education on a model for palliative care in LTC with supporting resources and tools that helped train over 200 participants. The collaborative also included opportunities for peer-to-peer knowledge sharing. This approach contributed to changes in the perception of palliative care and increases in knowledge and skills of staff members to have GOC with residents. These changes had a positive impact on staff confidence and comfort leading to earlier and more frequent GOC discussions, and improved team collaboration.

Table 4.

Key takeaways from HEC’s EPAC collaborative

| Topic | Key learnings |

| Education on palliative care | HEC learning activities increased the knowledge, skills and comfort level of staff to have earlier and more effective GOC conversations with residents and families. It is recommended to have palliative care education as a core part of staff orientation and subsequent training and consider creative methods for tracking progress and celebrating successes (eg, team posters and/or presentations). |

| Education in LTC | HEC’s regional workshop approach helped train more people on the EPAC model on-site and increased the level of engagement of teams. This is especially important in LTC where staff travel may be a barrier to participating in face-to-face learning activities. |

| Understanding the ‘why’ | The experience of HEC’s lead coach with the EPAC model in VCH helped provide practical advice, resources and tools. As the innovator of the EPAC model, HEC’s lead coach explained the value of the gift of time in palliative care by sharing personal stories with loss and grief to emphasise the why behind the collaborative. |

EPAC, Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care; HEC, Healthcare Excellence Canada; LTC, long-term care.

Interpretation

Palliative approaches to care can improve quality of life for residents living in LTC. The goal of the EPAC collaborative was to transform palliative approaches to care in LTC to allow residents, family members and teams working alongside them, to feel confident and comfortable in having effective and timely conversations to understand palliative care needs to improve care, ensure residents receive palliative care in the location of their choice and thereby reduce unnecessary hospital transfers.

Studying this intervention led to identifying success factors including effective stakeholder engagement, having a common understanding around palliative care approaches, having policies in place which are supportive of the new/revised approach, using appropriate learning strategies and sustaining change (online supplemental material 2).

bmjoq-2021-001581supp002.pdf (55.1KB, pdf)

Involving the right people

Stakeholders for the EPAC collaborative included residents and family members, physicians, front-line staff and senior leadership. Understanding who is impacted by change and engaging them in meaningful ways in the improvement is central to success. Successful engagement helps to create an improvement culture of doing with instead of doing for, with most change management models incorporating some element of stakeholder engagement.15 16 Stakeholder engagement is essential for improving the acceptability and feasibility of interventions.17 Engaging stakeholders to design strategies which meet their needs is also noted to improve the outcomes of change.9 18 In this project, all teams had objectives focused on engaging with their stakeholders to understand different perspectives and to share information about the project and about palliative care. Teams continued to acknowledge they still had work to do to fully engage some team members, which was a barrier to ongoing implementation of the EPAC model.

Changing the culture to support the implementation of palliative care approaches, such as EPAC, in the LTC setting is challenging because as a sector, LTC is arguably under-resourced and impacted by increased staff turnover.19–21 Issues with resourcing and increased staff turnover made it challenging for some of the LTC homes to implement changes, such as EPAC. It was noted that dedicated project management resources, which some teams were able to leverage, improved the chances of successful implementation of the EPAC model. Not surprisingly, the association between successful change and dedicated resources is seen in the literature.22 23 Without dedicated support, the additional burden on other team members who were expected to act as a ‘clinical champion’ was too great alongside other responsibilities.

Having a common perception

The first phase of any change involves preparing the team to accept that change is necessary.24 In this project, teams were invited to assess the current state of palliative care approaches in their LTC homes. Therefore, project leads were able to articulate the need for change to their teams, a strategy which is widely cited in the change management literature.9 15 24 25 Teams used a variety of strategies to understand existing palliative care approaches in the LTC homes by engaging stakeholders in a range of activities, including surveys, document reviews and meetings. Engaging stakeholders in the conversation helped to inform the approach needed for education and training, but also created opportunities for increased open dialogue and comfort in having discussions relating to palliative and end-of-life care. Being able to have open conversations with residents, families and staff about palliative care needs, normalised death and dying and contributed to culture change in the LTC home.26 27 This approach to openness around palliative care discussions, such as talking with residents and families about GOC or advance care planning discussions, was a key aspect of culture change in this project. Rather than being afraid to broach the subject of death and dying, teams learnt that residents and families were often relieved to be able to talk about what gave their lives meaning and how they wanted to use their gift of time.27 28

Developing supportive policies

Teams were able to leverage what they heard from stakeholders to develop policies and processes in the LTC home to enhance palliative care approaches. Identifying strategies to engage patients and families in the design and delivery of health services can inform policies around service delivery and education.29 This was seen in this project, as teams integrated what they heard from residents and families about care into everyday practice. Strategies to embed supportive policy and process included (1) completing GOC conversations as part of the moving-in process using common assessment tools for early identification of palliative care needs and clarifying when GOC discussions need to be reviewed with the resident; (2) providing access to psychosocial support following the loss of a resident to families, staff and other residents; (3) providing education and training sessions on palliative care as part of the orientation process, with refresher sessions; (4) collaborating with physicians and pharmacists to review medication order sets and provide residents with comfort care; and (5) including the GOC of a resident in their hospital transfer report and reviewing the appropriateness of ED transfers on a case-by-case basis.

Learning to improve performance

EPAC and its resulting change in culture is a complex intervention, requiring a thoughtful and ongoing implementation strategy.30 The purpose of the collaborative was to equip teams with the knowledge and skills needed to start, learn from their implementation experience, and then sustain and spread the EPAC model. Learning strategies adopted by teams included peer-to-peer sharing, collecting and reviewing monthly data on resident deaths, team huddles and formal evaluation strategies, such as focus groups, surveys and/or informal discussions with families and residents. Teams also found tremendous value in sharing stories of how changes had been implemented (eg, during resident and family council, in newsletters and staff meetings).31 The value of sharing stories in the quality improvement journey has been seen in the literature.32–34 An element in many well-known quality improvement frameworks is using data to support quality improvement.35–38 This was a key aspect in this project as teams used data which they were collecting as part of performance management requirements to identify learning opportunities.

Sustaining changes to practice

Using the Long-Term Success Tool was part of the process which guided the EPAC implementation in this project.9 The complex task of sustaining changes to practice requires a common perception of the goals of change, implementation of supportive policies, capacity and readiness to successfully undertake improvement, leadership support and alignment with organisational objectives.39 The EPAC model is a flexible framework that was adapted based on the context of each LTC home to leverage local assets and meet needs, again aligned to long-term success factors for sustainability.9 Teams have shared plans to sustain progress by continuing to provide education on GOC, reviewing policies based on lessons learnt from the collaborative, ongoing dialogue with stakeholders, and continuing to engage with residents and families, who may need enhanced communication around end-of-life and palliative care needs.26–29 However, stakeholders were also engaged as change agents to support sustainability of improvements.9 17 40 In this project, it was noted that staffing and resource issues were a potential barrier to sustained change in the LTC setting.19–21 23 It is not clear how these challenges with resources and health human workforce capacity will be met in LTC homes as we move forward in a postpandemic world where LTC has experienced a significant increase in deaths and added demands of restrictions and increased workloads for caregivers.41 42 In this time, LTC has seen a subsequent increased demand on palliative and end-of-life care in an environment where resources are already strained.43 Sustaining the improvements made in this project needs to have visible commitment from senior leadership in LTC homes to ensure that changes are anchored into custom and practice and where there is continued alignment between the EPAC model and other organisational values, culture and priorities.9 15 16

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this collaborative included the use of an innovative model, consistent coaching, support from the original implementation site (VCH), flexible implementation approach (eg, customised regional workshops and curriculum modifications based on feedback) and multiple peer-to-peer sharing opportunities. Teams had access to data submission and tracking for improvement as well as feedback on their implementation progress through both data and coaching support.

The collaborative also had limitations. The first one is the data collection interval. Teams were reporting monthly on any resident deaths for that month (where n>5). However, given that the average LOS was 4 years for the homes participating in this collaborative, the 12-month collaborative timeline was insufficient to evaluate the impact of EPAC on the entire resident cohort. The second limitation is the use of self-assessment data which is a subjective method for evaluating the impact of the EPAC model on the knowledge and skills of staff. The third limitation is the variability in care environments (eg, seasonal illness, construction and natural disasters) that impacted ability to dedicate resources to the EPAC implementation. This, along with the relatively small number of participating teams, limited the value of detailed cross-site comparisons in the evaluation analysis.

Conclusion

The EPAC collaborative provided a successful roadmap for participating teams to improve palliative care delivery by increasing the comfort and confidence of staff, encouraging earlier and more frequent GOC conversations with residents and their families, and implementing care plans in a way that is consistent with their expressed preferences. Successful implementation of EPAC depends on a shift in the culture of care, which requires leadership support, a shared commitment to what it means to provide quality palliative care, and dedicated time and resources for learning and improvement.

Acknowledgments

HEC thanks all the Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care (EPAC) teams, including the staff, residents and families, and coaches (Jane Webley, Dr Alain Legault, Claire Ludwig and Cynthia Sinclair) for their participation in the EPAC collaborative.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DianaSarakbi

Contributors: DS is responsible for the content as the guarantor. DS led the evaluation of the Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care (EPAC) collaborative and prepared the manuscript. EG led the design of the EPAC collaborative and provided input into the manuscript. GK supported the evaluation of the EPAC collaborative. JW developed the EPAC model and provided input into the manuscript. SC supported the knowledge translation activities of the EPAC collaborative and provided input into the manuscript. CQ oversaw the EPAC collaborative and provided input into the manuscript.

Funding: This quality improvement project was funded by Healthcare Excellence Canada.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. N/a (quality improvement report)

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Since the Embedding a Palliative Approach to Care collaborative was a quality improvement initiative, research ethics board approval was not required.

References

- 1.Health Canada . Framework on palliative care in Canada, 2018. Available: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/palliative-care/framework-palliative-care-canada/framework-palliative-care-canada.pdf

- 2.Canadian and Institute for Health Information . Access to palliative care in Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Conference Board of Canada . Sizing up the demand for long-term care in Canada. Ottawa, Canada: The Conference Board of Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ontario Long Term Care Association . This is long-term care 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Institute of Health Information . Sources of potentially avoidable emergency department visits, 2014. Available: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/ED_Report_ForWeb_EN_Final.pdf

- 6.Hall S, Kolliakou A, Petkova H, et al. Interventions for improving palliative care for older people living in nursing care homes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011:CD007132. 10.1002/14651858.CD007132.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaasalainen S, Sussman T, McCleary L, et al. Palliative care models in long-term care: a scoping review. Nurs Leadersh 2019;32:8–26. 10.12927/cjnl.2019.25975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudgeon D. The impact of measuring patient-reported outcome measures on quality of and access to palliative care. J Palliat Med 2018;21:S-76–S-80. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lennox L, Doyle C, Reed JE, et al. What makes a sustainability tool valuable, practical and useful in real-world healthcare practice? A mixed-methods study on the development of the long term success tool in northwest London. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014417. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bissett KM, Cvach M, White KM. Improving competence and confidence with evidence-based practice among nurses: outcomes of a quality improvement project. J Nurses Prof Dev 2016;32:248–55. 10.1097/NND.0000000000000293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selman L, Robinson V, Klass L, et al. Improving confidence and competence of healthcare professionals in end-of-life care: an evaluation of the 'Transforming End of Life Care' course at an acute hospital trust. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:231–6. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billingham MJ, Billingham S-J. Congruence between preferred and actual place of death according to the presence of malignant or non-malignant disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:144–54. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caspar S, Cooke HA, Phinney A, et al. Practice change interventions in long-term care facilities: what works, and why? Can J Aging 2016;35:372–84. 10.1017/S0714980816000374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low L-F, Fletcher J, Goodenough B, et al. A systematic review of interventions to change staff care practices in order to improve resident outcomes in nursing homes. PLoS One 2015;10:e0140711. 10.1371/journal.pone.0140711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotter JP, change L. Boston. Mass: Harvard Business School Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters TJ, Waterman RH, Human Resource Management . In search of excellence. 22. New York: Harper & Row, 1982: 325–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heckman GA, Boscart V, Quail P, et al. Applying the knowledge-to-action framework to engage stakeholders and solve shared challenges with person-centered advance care planning in long-term care homes. Can J Aging 2022;41:110–20. 10.1017/S0714980820000410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward ME, De Brún A, Beirne D, et al. Using co-design to develop a collective leadership intervention for healthcare teams to improve safety culture. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061182. [Epub ahead of print: 05 06 2018]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collingridge Moore D, Payne S, Van den Block L, et al. Strategies for the implementation of palliative care education and organizational interventions in long-term care facilities: a scoping review. Palliat Med 2020;34:558–70. 10.1177/0269216319893635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chenoweth L, Jessop T, Harrison F, et al. Critical contextual elements in facilitating and achieving success with a person-centred care intervention to support antipsychotic deprescribing for older people in long-term care. Biomed Res Int 2018;2018:1–12. 10.1155/2018/7148515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Froggatt KA, Moore DC, Van den Block L, et al. Palliative care implementation in long-term care facilities: European association for palliative care white paper. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21:1051–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prosci . Five levers of organizational change management, 2017. Available: https://www.prosci.com/resources/articles/five-levers-of-organizational-change-management

- 23.Errida A, Lotfi B. The determinants of organizational change management success: literature review and case study. Int J Eng Bus Manag 2021;13:184797902110162. 10.1177/18479790211016273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewin K. Field Theory of Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers. In: Cartwright D, ed. The ANNALS of the American Academy of political and social science. 276. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1951: 146–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith ME. Implementing organizational change: correlates of success and failure. Perform Improv Q 2002;15:67–83. 10.1111/j.1937-8327.2002.tb00241.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clark D. 'Total pain', disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:727–36. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00098-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durepos P, Kaasalainen S, Sussman T, et al. Family care conferences in long-term care: exploring content and processes in end-of-life communication. Palliat Support Care 2018;16:590–601. 10.1017/S1478951517000773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilissen J, Pivodic L, Smets T, et al. Preconditions for successful advance care planning in nursing homes: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;66:47–59. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2018;13:98. 10.1186/s13012-018-0784-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caspar S. Stakeholder engagement for successful practice change in long‐term care: evaluating the feasible and sustainable culture change initiative (FASCCI) model. Alzheimer's & Dementia 2020;16:e036917. 10.1002/alz.036917 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen PW. Stories beyond the box. Health Aff 2008;27:1148–53. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stargatt J, Bhar S, Bhowmik J, et al. Digital Storytelling for health-related outcomes in older adults: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2022;24:e28113. 10.2196/28113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcock PM, Brown GCS, Bateson J, et al. Using patient stories to inspire quality improvement within the NHS modernization agency collaborative programmes. J Clin Nurs 2003;12:422–30. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ham C, Berwick D, Dixon J. Improving quality in the English NHS. London: The King’s Fund, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah A. Using data for improvement. BMJ 2019;364:l189. 10.1136/bmj.l189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Au S, Murray E. Data management for quality improvement: how to collect and manage data. AACN Adv Crit Care 2021;32:213–8. 10.4037/aacnacc2021118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deming WE. The new economics for industry, government, education. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Center for Advanced Engineering Study, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langley GJ, Moen R, Nolan KM. The improvement guide: a practical approach to enhancing organizational performance. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass,, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci 2018;13:27. 10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baetz-Dougan M, Reiter L, Quigley L, et al. Enhancing care for long-term care residents approaching end-of-life: a mixed-methods study assessing a palliative care transfer form. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38:1195–201. 10.1177/1049909120976646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Government of Ontario . How Ontario is responding to COVID-19, 2020. Available: https://www.ontario.ca/page/how-ontario-is-responding-covid-19

- 42.Lapid MI, Koopmans R, Sampson EL, et al. Providing quality end-of-life care to older people in the era of COVID-19: perspectives from five countries. Int Psychogeriatr 2020;32:1345–52. 10.1017/S1041610220000836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inzitari M, Risco E, Cesari M, et al. Editorial: nursing homes and long term care after COVID-19: a new era? J Nutr Health Aging 2020;24:1042–6. 10.1007/s12603-020-1447-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2021-001581supp001.pdf (42.4KB, pdf)

bmjoq-2021-001581supp002.pdf (55.1KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. N/a (quality improvement report)