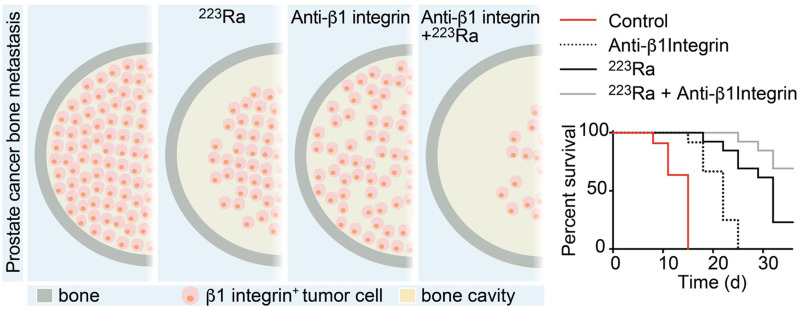

Visual Abstract

Keywords: 223Ra, prostate cancer, bone metastasis, integrin β-1

Abstract

223Ra is an α-emitter approved for the treatment of bone metastatic prostate cancer (PCa), which exerts direct cytotoxicity toward PCa cells near the bone interface, whereas cells positioned in the core respond poorly because of short α-particle penetrance. β1 integrin (β1I) interference has been shown to increase radiosensitivity and significantly enhance external-beam radiation efficiency. We hypothesized that targeting β1I would improve 223Ra outcome. Methods: We tested the effect of combining 223Ra and anti-β1I antibody treatment in PC3 and C4-2B PCa cell models expressing high and low β1I levels, respectively. In vivo tumor growth was evaluated through bioluminescence. Cellular and molecular determinants of response were analyzed by ex vivo 3-dimensional imaging of bone lesions and by proteomic analysis and were further confirmed by computational modeling and in vitro functional analysis in tissue-engineered bone mimetic systems. Results: Interference with β1I combined with 223Ra reduced PC3 cell growth in bone and significantly improved overall mouse survival, whereas no change was achieved in C4-2B tumors. Anti-β1I treatment decreased the PC3 tumor cell mitosis index and spatially expanded 223Ra lethal effects 2-fold, in vivo and in silico. Regression was paralleled by decreased expression of radioresistance mediators. Conclusion: Targeting β1I significantly improves 223Ra outcome and points toward combinatorial application in PCa tumors with high β1I expression.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the fifth leading cause of death from cancer worldwide and the most common malignancy in elderly men (1). Androgen receptor signaling inhibitors and chemotherapy are effective in local tumors, with a 99% survival rate at 5 y from diagnosis but responses of short duration for advanced metastatic disease (<30% survival at 5 y) (1). Bone is the most frequent site for PCa distant colonization, as identified in 84% of the patients with metastatic lesions (2). The interactions between cancer and bone-resident cells disrupt the finely balanced biology of bone, leading to symptomatic remodeling, spinal cord compression, fractures, limited mobility, and ultimately the patient’s death (3,4).

223Ra, a bone-targeted radionuclide, has recently been approved for the treatment of advanced metastatic PCa patients with bone lesions (5). This α-emitter accumulates in mineralized bone tissue because of its calcium-mimetic properties and is enriched in areas with high bone turnover (6,7). The short penetration range of α-particles (<100 μm) minimizes the impact on the healthy bone marrow tissue, thus reducing side effects associated with treatment with β-emitters (6,8). 223Ra low systemic toxicity coupled to improved survival and significant delay of first symptomatic skeletal events led to clinical testing in other neoplasias in bone, including multiple myeloma; renal cell carcinoma; and breast, lung, and thyroid cancer (9).

Recently, we demonstrated that 223Ra kills with maximum efficiency PCa cells proximal to the bone surface (within 100 μm), whereas it leaves the distant core unperturbed (7). On the basis of this strictly zonal toxicity, 223Ra therapy was more effective when applied to lesions of limited size (7). As an alternative, the combination of 223Ra with other agents that radiosensitize PCa cells could enhance its efficacy.

The inhibition of integrin pathways increases the effectiveness of external-beam radiation in multiple cancer types, including head and neck, breast, and prostate, both locally and in metastatic sites (10–14). Integrins are heterodimeric transmembrane receptors composed of α- and β-subunits, which mediate interactions with extracellular matrix ligands (15) and signaling cross-talk with growth factor receptors (16). Through these combined functions, integrins support cell growth, decrease cell death by promoting anchorage-dependent survival, and enable radioresistance mechanisms on exposure to ionizing γ-radiation, including induction of adhesion and survival signaling and enhanced DNA repair (14,17,18). Anti-β1 integrin (β1I) targeting improves irradiation treatment outcomes in breast cancer cells in 3-dimensional cultures and in vivo subcutaneous xenografts, reaching efficacy comparable to high-dose radiotherapy (11). Blocking β1I in PC3 PCa subcutaneous tumors further inhibits their growth on irradiation (13). Consequently, targeting of β1I in combination with γ-radiation can increase response and reduce survival of cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In Vivo Studies

Animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and were performed according to the institutional guidelines for animal care and handling. Luciferase-expressing PCa cells were administered in the tibia as previously reported (7). Details on in vivo studies are provided in the supplemental information.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism, version 8.0 (GraphPad Software). An unpaired 2-sided Student t test was applied to analyze 2 populations, whereas 1-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey honestly-significant-difference post hoc test, was performed to compare more than 2 populations. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and statistical significance was considered for a P value of less than 0.05. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Further experimental methods are detailed in the supplemental information.

RESULTS

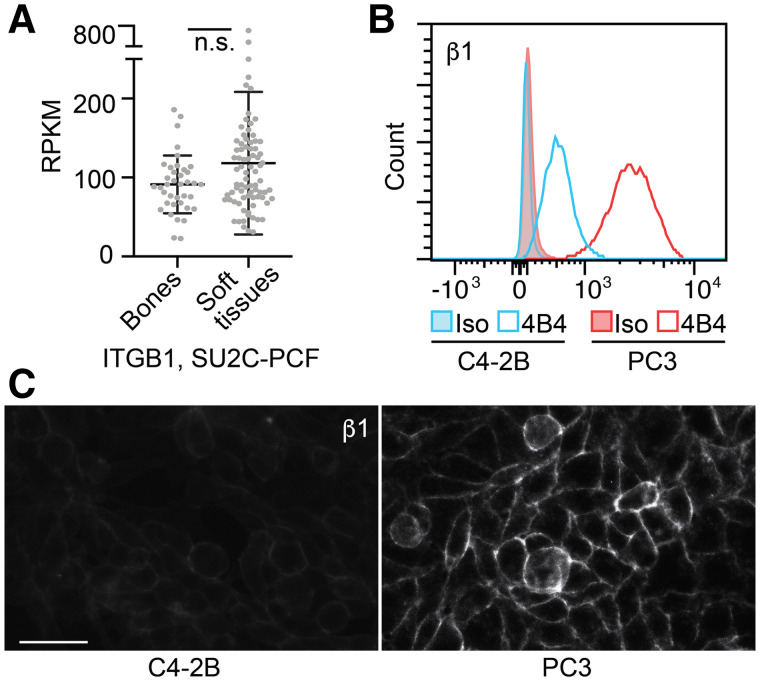

Expression of β1I and Consequences of Targeting, In Vitro

To define the relevance of anti-β1I targeting in PCa bone metastasis, we confirmed its expression by interrogating transcriptomic data from the Stand Up to Cancer/Prostate Cancer Foundation database, which contains RNA sequence data derived from a cohort of 150 bone or soft-tissue biopsies (19). The β1I transcript showed heterogeneous expression in both sample types, with no significant differences (Fig. 1A), indicating that PCa bone metastases can retain β1I expression at different levels. To recapitulate the role of β1I targeting in PCa, we used PC3 and C4-2B cells as models for high or low β1I expression (20), respectively, which was confirmed by flow cytometry and immunofluorescence analysis (Figs. 1B and 1C). For targeting, we used the antihuman β1I 4B4 blocking monoclonal antibody (4B4-mAb), which sensitizes solid tumors to γ-irradiation (21). To explore the functional significance of β1I interference, we monitored PCa cell growth in the presence of 4B4-mAb. PC3 cell proliferation and mitotic index were significantly reduced by 4B4-mAb treatment (Supplemental Fig. 1A; supplemental materials are available at http://jnm.snmjournals.org), whereas C4-2B cell culture was not affected by anti-β1I targeting (Supplemental Fig. 1B). These results suggest that β1I is variably expressed in PCa patients and cell lines and that its targeting has biologically active effects in a PCa subset endowed with higher expression levels.

FIGURE 1.

β1I expression, in vitro. (A) RNA expression of ITGB1 in bones and soft-tissue metastasis, Stand Up to Cancer/Prostate Cancer Foundation database. (B and C) Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence analysis of β1I expression in PC3 and C4-2B cells. Experiment was repeated twice. Bar = 50 μm; n.s. = nonsignificant.

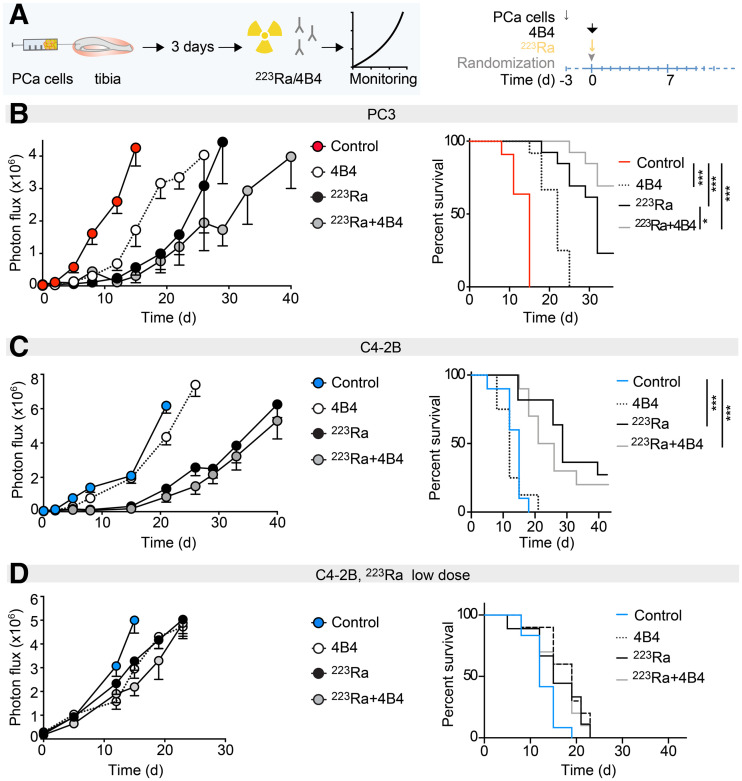

Effects of Combined 223Ra and Anti-β1I Treatment on PCa Cell Growth in the Tibia

To determine the effects of 223Ra and anti-β1I combinatorial treatment on PCa bone lesions, luciferase-expressing PC3 cells were injected into mouse tibiae (n = 13–19 tibiae/group), randomized at day 3 after implantation and treated with a single dose of 223Ra (300 kBq/kg) and 4B4-mAb (100 μg/mouse), alone or in combination, and tumor growth was monitored longitudinally by macroscopic bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 2A; Supplemental Fig. 2). 4B4-mAb specifically targets human β1I without cross-reactivity to murine integrins (22), thus allowing identification of direct effects exerted on human tumor cells without perturbing the murine bone microenvironment. PC3 tumors retained β1I expression in vivo (Supplemental Fig. 3), and treatment with 4B4-mAb delayed their growth and significantly extended mouse survival compared with control-treated animals (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Fig. 2A). 223Ra treatment alone extended survival more efficiently, and combinatorial treatment further significantly improved mouse survival, with approximately 70% of mice still alive 40 d after treatment (Fig. 2B). No signs of increased distress (including major weight loss, reduced hydration, difficulties in breathing, aberrant behavior and movements, abdominal cavity swelling) were identified in mice treated with 223Ra or 4B4-mAb, alone or in combination.

FIGURE 2.

In vivo response of PCa cells in bone to anti-β1I (4B4) and 223Ra treatments. (A) Experimental design and timeline of treatment schedule. (B) PC3 tumors, growth, and survival curve over time (223Ra, 300 kBq/kg; 4B4-mAb, 100 μg/mouse; n = 13–19 tumors). (C and D) C4-2B tumors, growth curve, and survival curve over time (223Ra, 300 kBq/kg; 4B4-mAb, 100 μg/mouse; n = 8–10 tumors [C]; 223Ra, 100 kBq/kg; 4B4-mAb, 100 μg/mouse; n = 9–12 tumors [D]). *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001, 1-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey honestly-significant-difference post hoc test.

When tested in C4-2B tumors implanted in bone (n = 8–10 tibiae/group), 4B4-mAb improved neither survival nor the efficacy of 223Ra (Fig. 2C; Supplemental Figure 2B), indicating insensitivity to β1I targeting, probably due to low β1I expression levels in vivo (Supplemental Fig. 3). By comparison with PC3 bone lesions, C4-2B tumors showed negligible growth until day 21 after 223Ra treatment. To rule out the possibility that therapeutic improvement by 4B4-mAb treatment was confounded by this strong response, a second cohort (n = 9–12 tibiae/group) received low-dose 223Ra treatment (100 kBq/kg) combined with 4B4-mAb. Reduced dosing of 223Ra resulted in accelerated tumor progression, but similar to the high-dose regimen, 4B4-mAb did not improve 223Ra outcome (Fig. 2D; Supplemental Fig. 2C). These results suggest that combining β1I targeting and 223Ra treatment improves efficacy of 223Ra in PCa tumors with higher β1I expression.

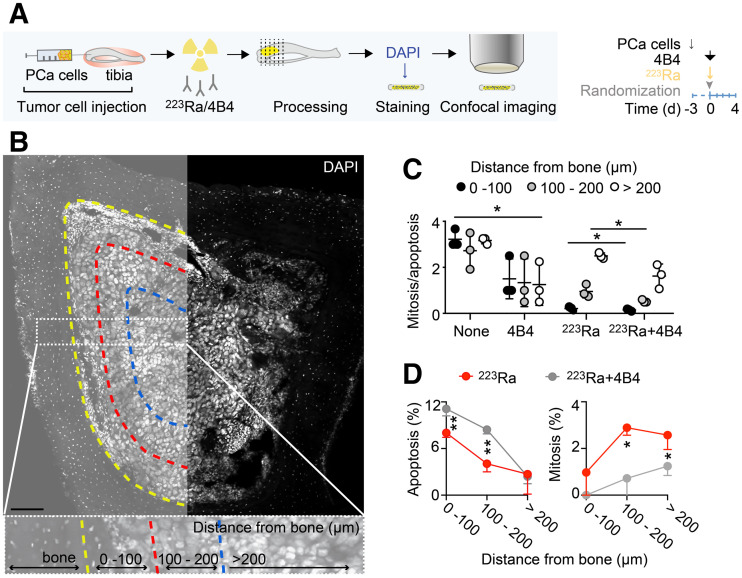

223Ra and 4B4-mAb Zonal Toxicity in PCa Bone Lesions

To determine the cellular effects of combined 223Ra and 4B4-mAb treatment on PC3 bone lesions, we monitored cytotoxicity exerted by combinatorial therapy versus single treatments by single-cell cytometry in transversal 3-dimensional bone sections captured at the confocal microscope 4 d after treatment (Fig. 3A). PC3 lesions were segmented, and the number of mitotic and apoptotic events was quantified for subregions with a 100-, 200-, or greater than 200-μm distance from cortical bone (Fig. 3B), a corridor that fully accommodates the short distance reached by α-particles (<100 μm) (8). PC3 tumor cells were easily distinguishable from resident bone marrow cells on the basis of the large nuclear size and pattern of heterochromatin; also, mitotic figures and cell death were clearly identifiable on the basis of their typical nuclear pattern (Supplemental Fig. 4). Control-treated lesions lacked a zonal increase in mitotic or apoptotic cells; 4B4-mAb induced a uniform decrease in mitotic index throughout the tumor (Fig. 3C), whereas 223Ra induced zonal toxicity with higher rates of cell death next to the cortical bone (0–100 μm) and a decreasing effect at a greater distances (Fig. 3C), as described (7). The combination of 223Ra and 4B4-mAb improved zonal efficacy by decreasing the mitosis-to-apoptosis ratio (Fig. 3C). This effect was mediated by coupling of significantly increased levels of apoptosis with a significant reduction in mitosis, compared with 223Ra alone (Fig. 3D). These results suggest that both the spatial extension of 223Ra cytotoxic effects and a decrease in mitosis contribute to improved outcome (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 3.

Cellular mechanisms of response to anti-β1I and 223Ra treatments. (A) Cartoon and timeline. (B) Representative overview micrograph. Insert shows zoomed subregions segmented every 100 μm from bone interface. Bar = 100 μm. (C) Quantification of mitosis/apoptosis nucleus ratio for each treatment condition. Data are mean ± SD (n = 3 bones/treatment, 3–5 slices/bone). (D) Zonal comparison of apoptotic and mitotic cells for 223Ra and 223Ra + 4B4 treatments. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01 by 1-way ANOVA and honestly-significant-difference post hoc test. DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Enlargement of the tumor cell nucleus induced by genome replication without cell division follows exposure to high doses of ionizing radiation and is already visible during the first days after irradiation (23–25). No changes in size were evident in control- or 4B4-treated lesions at any distance from bone, as quantified using ImageJ and StarDist software (26,27). 223Ra induced a tumor cell nuclear size enlargement within 100 μm, compared with both 100–200 μm and more than 200 μm of distance from bone, whereas the 223Ra-4B4 combination showed a significantly increased size up to a 200-μm distance from bone, confirming that a broader area was impacted by radiation effects (Supplemental Figs. 5A and 5B).

Overall, these results indicate that β1I targeting decreases mitosis and sensitizes PC3 cells to 223Ra by broadening the tumor volume fraction that responds to radiation therapy.

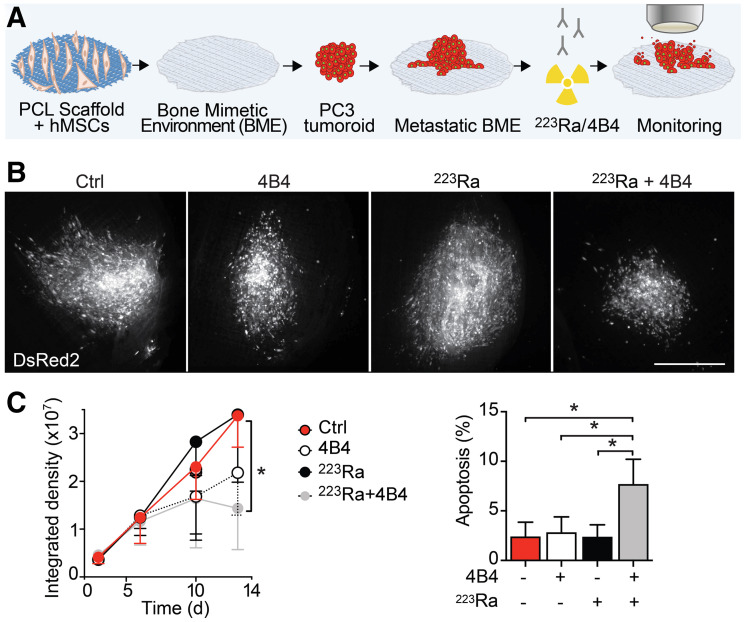

Sensitization of Tumor Cells to Radiation Through 4B4-mAb Treatment

To address the ability of β1I interference to radiosensitize for 223Ra, we implemented PC3 cell treatment with ultra-low 223Ra doses in a 3-dimensional in vitro bone mimetic environment (BME). This system consists of a polycaprolactone scaffold functionalized by human mesenchymal stem cells differentiated to bioactive osteoblasts that produce a calcified bone matrix (Fig. 4A), which incorporates 223Ra efficiently and simulates in vivo distribution (28). PCa tumoroids were seeded on BMEs and were treated with 4B4-mAb or 223Ra (10 Bq/mL (28)), and the response was evaluated longitudinally by live-cell microscopy (Fig. 4A). Individually, neither 223Ra nor 4B4-mAb as single modalities significantly impaired PC3 viability or growth. When combined, however, they significantly decreased tumoroid growth and increased the number of apoptotic cells (Figs. 4B and 4C; Supplemental Fig. 6). To further identify whether β- or γ-emission (which represent 3.6% and 1.1% of 223Ra decay series, respectively (29)) may contribute to 223Ra-mediated cytotoxicity, we preadsorbed 223Ra at high doses (1,600 Bq/mL) to BMEs, washed them, and fit them in a Transwell system (Corning) at more than a 1-mm distance from PC3 cells, ruling out α-particles (Supplemental Fig. 7A). 223Ra was retained within BMEs, with negligible release in the medium (<2%; Supplemental Fig. 7B). However, PC3 cell growth was significantly reduced in this large-distance culture by 223Ra alone and was further diminished by 223Ra + 4B4-mAb treatment (Supplemental Fig. 7C). These data indicate that, besides a direct short-range effect of α-particles, 223Ra cytotoxicity may be supported by β- or γ-emission, but considering the limited fraction emitted (29), a minor contribution can be expected at therapeutic doses.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of 4B4-mAb treatment on α-radiation sensitization. (A) Cartoon of experimental pipeline. (B and C) Representative pictures of PC3 tumoroids treated with 4B4-mAb (15 μg/mL) and 223Ra (10 Bq/mL) alone or in combination (B); growth curve, with 3 independent experiments performed (means ± SD, 6 scaffolds/condition; C, left panel); and percentage of apoptotic cells after treatment (means ± SD, 6 scaffolds/treatment; C, right panel). Bar = 100 μm. *P < 0.05 by 1-way ANOVA and honestly-significant-difference post hoc test.

Interestingly, functional proteomics (reverse-phase protein array) performed on PC3 bone lesions treated with 4B4-mAb showed that the top proteins mostly affected by β1I targeting (Supplemental Table 1) were involved in tumor cell proliferation and radiosensitization, including lactate dehydrogenase-A (30), bromodomain-containing protein 4 (31), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (32). Lactate dehydrogenase-A overexpression in PCa has been linked to aggressive tumors with a higher frequency of local relapse on radiotherapy treatments, whereas its knockdown causes radiosensitization of PC3 cells (30). Bromodomain-containing protein 4 plays a central role in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks, and high expression is associated with poor prognosis after PCa radiation therapy (31). Mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal–regulated kinase pathway, thus affecting the survival of nonadherent cells (33), whereas its inhibition increases radiosensitivity of PCa xenografts via c-Myc downregulation (32). Transcription factor A, glutaminase, and fatty acid synthase have been also linked to radioresistance (34–36).

Overall, these results suggest that anti-β1I treatment can sensitize tumor cells to 223Ra treatment.

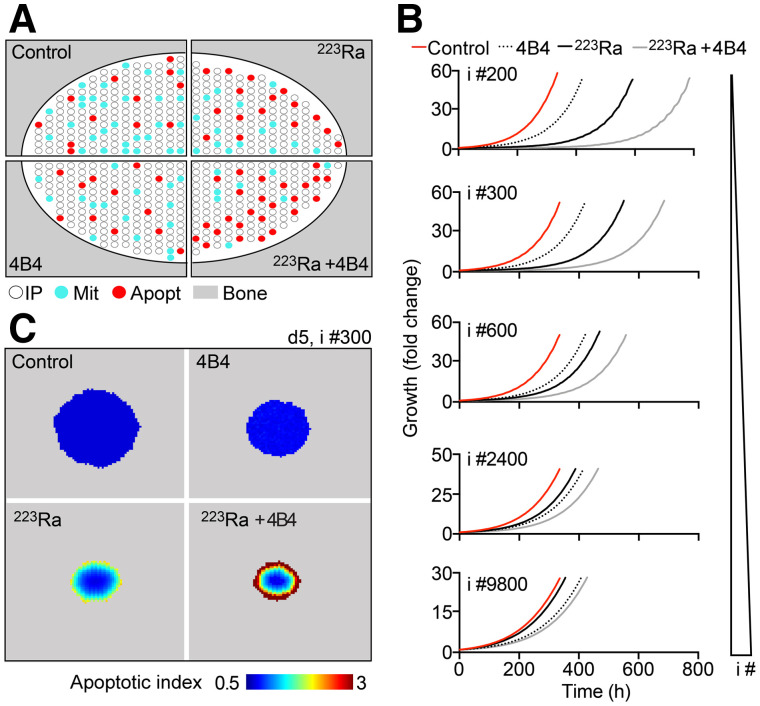

Mathematic Modeling of 223Ra and 4B4-mAb Zonal Toxicity in PCa Bone Lesions

Our analyses suggest that β1I interference decreases mitosis rates, and when combined with 223Ra treatment, increases apoptosis along the bone interface. This dual effect may translate into tumor growth reduction and improved survival. To confirm whether decreased mitosis combined with extended zonal toxicity could mechanistically explain in vivo outcome, we performed in silico simulation based on an agent-based model that recapitulates zonal toxicity of 223Ra on tumors in bone (7,37). The agent-based model was further developed to account for the response to 4B4-mAb based on probabilities of mitosis or apoptosis obtained from 4B4-treated mice (Figs. 3C and 5A). Tumor growth simulations in response to 4B4-mAb as a single agent or in combination with 223Ra were performed for up to 800 h in tumors of different sizes (1–9,800 cells; Figs. 5A and 5B). The responses to combinatorial regimen and tumor size were inversely correlated, with potent tumor rejection of single or few cells and further efficacy improvement in bigger lesions that responded poorly to 223Ra monotherapy (e.g., initial size of 2,400 cells; Fig. 5B; Supplemental Table 2). Control and 4B4-treated lesions did not show any spatial correlate for mitotic or apoptotic probabilities (Fig. 5C; Supplemental Fig. 8), as expected. 223Ra treatment increased the apoptotic index along the bone interface, in a time-dependent manner accounting for 223Ra decay. Combined 223Ra and 4B4-mAb broadened the zone and duration of an elevated apoptotic index. These results confirm that 4B4-mediated extension of 223Ra lethal effects combined with mitosis reduction support increased efficacy in vivo.

FIGURE 5.

Mathematic modeling of 223Ra and 4B4 response. (A) Schematic representation of in silico tumor lesions in bone. White dot = interphase (IP) cell; red dot = apoptotic cell; cyan dot = mitotic cell. (B) In silico simulations of tumor growth by lesions of different sizes in control, 4B4-mAb, 223Ra, or 223Ra + 4B4 treated samples (data represent means of 10 simulations). i #= initial number of tumor cells. (C) Apoptotic index (probability of apoptosis/probability of mitosis for each agent).

DISCUSSION

Metastatic cancer to bone is a persistent clinical challenge and a source of significant morbidity and mortality for patients afflicted with PCa. The inefficiency of current clinical investigations can be overcome, in part, by identifying new vulnerabilities and markers that can be used to select patients and monitor therapy response. We were motivated to perform this work to address the promising but limited efficacy that recently emerged from targeting bone metastasis by 223Ra. β1I interference increased 223Ra therapeutic outcome in tumors expressing higher levels of β1I by decreasing tumor growth and improving mouse survival via combined reduction of tumor cell mitosis and extension of 223Ra-mediated zonal apoptosis. Although β1I interference increases the efficacy of radiotherapy by means of external-beam radiation, we here establish integrin targeting as an efficient radiosensitizing strategy to improve the efficacy of α-particle–emitting bone-seeking radioisotopes.

Activation of β1I occurs during PCa progression and has been detected in 65% and 72% of primary PCa or lymph node specimens compared with normal prostatic tissue (38). Variable expression of transcripts has been also identified in both soft-tissue and bone metastatic patient samples (19). Accordingly, β1I is constitutively activated in highly metastatic PC3 cells compared with low metastatic C4-2B. Notably, β1I expression levels in PCa cells do not correlate with their lytic function, as strongly osteoblastic MDA PCa 118b tumors display higher expression levels of β1I than do PC3 cells (20).

β1I represents a potential marker to select a subset of metastatic patients who would benefit of cotargeting by 223Ra as a novel therapeutic strategy. Here, we tested only 2 cell lines endowed with β1I expression levels that differ by about 1 log in vitro and 1.5–2 log in vivo. The resistance of C4-2B cells to 4B4-mAb treatment suggests that β1I expression levels can correlate with targeting efficacy; however, we do not exclude that further alternative mechanisms could support resistance to this treatment. To better characterize this process and define a threshold for effective targeting of malignant cells, expression of β1I in vivo should be tested in a variety of PCa patient-derived xenografts (39) followed by combined 223Ra/anti-β1I treatment and response monitoring. Patient-derived xenografts have the advantage of replicating the heterogeneity of human cancer biology with high fidelity, thus more accurately modeling these aspects in translational therapeutic studies. In this work, we identified the consequences of specific tumor cell targeting by 4B4-mAb, which blocks exclusively human β1I and does not cross-react with the mouse stroma. Although being mechanistically informative about the direct effects on the tumor compartment, this approach does not address the role of targeting the bone environment. Besides in tumor cells, this integrin is expressed by bone stromal and immune cells (40), the targeting of which could further improve outcome, such as by interfering with the vicious cycle that supports cancer progression. On the other hand, stronger 223Ra-mediated effects on bone cells might exacerbate bone remodeling or increase bone marrow toxicity, which can be mitigated by administration of bisphosphonates or granulocyte-stimulating factor, respectively. These studies would require analysis in syngeneic or genetically engineered models using an antimouse β1I antibody that targets both tumor and stromal cells.

Combination of 4B4-mAb with 223Ra extended cancer cell apoptosis beyond the spatial range expected to be reached by α-particles (<100 μm). Reduced tumor density, caused by death induction, may allow the α-particles to travel farther than in a tighter, denser cellular matrix. In addition, we showed in a high-dose setting, in vitro, that long-range cytotoxicity can be in principle caused by 223Ra, but further biophysical analyses are needed to dissect the relative contribution of α-, β-, or γ-radiation to the zonal cytotoxic effect achieved in bone at a therapeutically administered dose. Lastly, enhanced bystander effects may account for broadened zonal cytotoxicity by 223Ra. Irradiation can induce a mutagenic response and cell activation, followed by juxtracrine bystander signaling toward nonirradiated neighboring cells through cell–cell interactions and release of soluble factors, including reactive oxygen species, toxic metabolites, and cytokines, which might be amplified by β1I targeting (41,42). In line with these concepts, indirect effects of 223Ra are supported by recent mouse and computational modeling, showing that a robust bystander effect component was required to simulate results achieved in vivo whereas a direct-effect component contributed modestly and was insufficient to explain in vivo outcome (43,44).

Interestingly, a humanized anti-β1I monoclonal antibody has recently been developed for applications in patients and is currently being tested in a phase I clinical trial for glioblastoma (45). Therefore, clinical β1I targeting combined with 223Ra may be a realistic option in patients on identification of suitable candidates based on its expression levels.

CONCLUSION

Targeting bone metastasis by 223Ra resulted in promising but limited therapeutic efficacy due to short α-particle penetrance. Our work identified β1-integrin interference as the first cotargeting strategy to improve 223Ra outcome.

DISCLOSURE

This work was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RP140482); the Prostate Cancer Foundation (16YOUN24); Prostate Cancer SPORE (P50 CA140388-07); the European Research Council (ERC-CoG DEEPINSIGHT, 617430); the National Institutes of Health (U54 CA210184–01; P41 EB023833; P30 CA016672); and the Cancer Genomics Cancer, The Netherlands. 223Ra is from Bayer. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Kent Gifford (University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center) for the insightful discussion.

KEY POINTS

QUESTION: Can we improve the promising (but limited) efficacy that recently resulted from targeting bone metastasis by 223Ra?

PERTINENT FINDINGS: β1I interference combined with 223Ra reduced PCa cell growth in bone and significantly improved overall mouse survival. Targeting β1I significantly decreased the tumor cell mitosis index and spatially doubled 223Ra lethal effects through radiosensitization and reduction of radioresistance mediators.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PATIENT CARE: β1I expression can represent a biomarker to select a subset of metastatic patients who would benefit from cotargeting by 223Ra; the availability of a humanized anti-β1I monoclonal antibody will soon make combinatorial testing in patients clinically feasible.

REFERENCES

- 1. Steele CB, Li J, Huang B, Weir HK. Prostate cancer survival in the United States by race and stage (2001-2009): findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer. 2017;123(suppl 24):5160–5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Schiffmann J, et al. Distribution of metastatic sites in patients with prostate cancer: a population-based analysis. Prostate. 2014;74:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D’Oronzo S, Coleman R, Brown J, Silvestris F. Metastatic bone disease: pathogenesis and therapeutic options: up-date on bone metastasis management. J Bone Oncol. 2019;15:004-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Park SH, Eber MR, Widner DB, Shiozawa Y. Role of the bone microenvironment in the development of painful complications of skeletal metastases. Cancers (Basel). 2018;10:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bruland ØS, Nilsson S, Fisher DR, Larsen RH. High-linear energy transfer irradiation targeted to skeletal metastases by the alpha-emitter 223Ra: adjuvant or alternative to conventional modalities? Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6250s–6257s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dondossola E, Casarin S, Paindelli C, et al. Radium 223-mediated zonal cytotoxicity of prostate cancer in bone. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:1042–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abou DS, Ulmert D, Doucet M, Hobbs RF, Riddle RC, Thorek DL. Whole-body and microenvironmental localization of radium-223 in naive and mouse models of prostate cancer metastasis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016. 5;108:djv380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Morris MJ, Corey E, Guise TA, et al. Radium-223 mechanism of action: implications for use in treatment combinations. Nat Rev Urol. 2019;16:745–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nam JM, Chung Y, Hsu HC, Park CC. β1 integrin targeting to enhance radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Biol. 2009;85:923–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Park CC, Zhang HJ, Yao ES, Park CJ, Bissell MJ. β1 integrin inhibition dramatically enhances radiotherapy efficacy in human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4398–4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cordes N, Blaese MA, Meineke V, Van Beuningen D. Ionizing radiation induces up-regulation of functional β1-integrin in human lung tumour cell lines in vitro. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goel HL, Sayeed A, Breen M, et al. Beta1 integrins mediate resistance to ionizing radiation in vivo by inhibiting c-jun amino terminal kinase 1. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1601–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eke I, Deuse Y, Hehlgans S, et al. B1 integrin/FAK/cortactin signaling is essential for human head and neck cancer resistance to radiotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu X, Lu D, Scully M, Kakkar V. The role of integrins in cancer and the development of anti-integrin therapeutic agents for cancer therapy. Perspect Medicin Chem. 2008;2:57–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eliceiri BP. Integrin and growth factor receptor crosstalk. Circ Res. 2001;89:1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blandin AF, Renner G, Lehmann M, Lelong-Rebel I, Martin S, Dontenwill M. Beta1 integrins as therapeutic targets to disrupt hallmarks of cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dickreuter E, Eke I, Krause M, Borgmann K, van Vugt MA, Cordes N. Targeting of β1 integrins impairs DNA repair for radiosensitization of head and neck cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35:1353–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Robinson D, Van Allen EM, Wu YM, et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell. 2015;161:1215–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee YC, Lin SC, Yu G, et al. Identification of bone-derived factors conferring de novo therapeutic resistance in metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4949–4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haeger A, Alexander S, Vullings M, et al. Collective cancer invasion forms an integrin-dependent radioresistant niche. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20181184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takada Y, Puzon W. Identification of a regulatory region of integrin beta 1 subunit using activating and inhibiting antibodies. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17597–17601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schwarz-Finsterle J, Scherthan H, Huna A, et al. Volume increase and spatial shifts of chromosome territories in nuclei of radiation-induced polyploidizing tumour cells. Mutat Res. 2013;756:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gasperin P, Jr, Gozy M, Pauwels O, et al. Monitoring of radiotherapy-induced morphonuclear modifications in the MXT mouse mammary carcinoma by means of digital cell image analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;22:979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen J, Niu N, Zhang J, et al. Polyploid giant cancer cells (PGCCs): the evil roots of cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2019;19:360–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schmidt U, Weigert M, Broaddus C, Myers G. Cell detection with star-convex polygons. In: Frangi A, Schnabel J, Davatzikos C, Alberola-López C, Fichtinger G, eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2018. 2018:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:671–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Paindelli C, Navone N, Logothetis CJ, Friedl P, Dondossola E. Engineered bone for probing organotypic growth and therapy response of prostate cancer tumoroids in vitro. Biomaterials. 2019;197:296–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eckerman K, Endo A. ICRP publication 107: nuclear decay data for dosimetric calculations. Ann ICRP. 2008;38:7–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Panteliadou M, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 isoenzyme overexpression defines resistance of prostate cancer to radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2217–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li X, Baek G, Ramanand SG, et al. Brd4 promotes DNA repair and mediates the formation of tmprss2-erg gene rearrangements in prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 2018;22:796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ciccarelli C, Di Rocco A, Gravina GL, et al. Disruption of MEK/ERK/c-Myc signaling radiosensitizes prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144:1685–1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kyjacova L, Hubackova S, Krejcikova K, et al. Radiotherapy-induced plasticity of prostate cancer mobilizes stem-like non-adherent, Erk signaling-dependent cells. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:898–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jiang X, Wang J. Down-regulation of TFAM increases the sensitivity of tumour cells to radiation via p53/TIGAR signalling pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:4545–4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fu S, Li Z, Xiao L, et al. Glutamine synthetase promotes radiation resistance via facilitating nucleotide metabolism and subsequent DNA damage repair. Cell Rep. 2019;28:1136–1143.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rae C, Haberkorn U, Babich JW, Mairs RJ. Inhibition of fatty acid synthase sensitizes prostate cancer cells to radiotherapy. Radiat Res. 2015;184:482–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Casarin S, Dondossola E. An agent-based model of prostate cancer bone metastasis progression and response to radium223. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lee YC, Jin JK, Cheng CJ, et al. Targeting constitutively activated beta1 integrins inhibits prostate cancer metastasis. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:405–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Palanisamy N, Yang J, Shepherd PDA, et al. The MD Anderson prostate cancer patient-derived xenograft series (MDA PCa PDX) captures the molecular landscape of prostate cancer and facilitates marker-driven therapy development. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:4933–4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hughes DE, Salter DM, Dedhar S, Simpson R. Integrin expression in human bone. J Bone Miner Res. 1993;8:527–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang R, Coderre JA. A bystander effect in alpha-particle irradiations of human prostate tumor cells. Radiat Res. 2005;164:711–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Narayanan PK, Goodwin EH, Lehnert BE. Alpha particles initiate biological production of superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide in human cells. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3963–3971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rajon DA, Canter BS, Leung CN, et al. Modeling bystander effects that cause growth delay of breast cancer xenografts in bone marrow of mice treated with radium-223. Int J Radiat Biol. 2021;97:1217–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Leung CN, Canter BS, Rajon D, et al. Dose-dependent growth delay of breast cancer xenografts in the bone marrow of mice treated with 223Ra: the role of bystander effects and their potential for therapy. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Convection-enhanced delivery of OS2966 for patients with high-grade glioma undergoing a surgical resection. ClinicalTrials.gov website. https://clinicaltrials.Gov/ct2/show/nct04608812. Published October 29, 2020. Updated January 26, 2022. Accessed February 24, 2022.