Abstract

Objectives

Earlier retrospective studies have suggested a relation between DISH and cardiovascular disease, including myocardial infarction. The present study assessed the association between DISH and incidence of cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with high cardiovascular risk.

Methods

In this prospective cohort study, we included 4624 patients (mean age 58.4 years, 69.6% male) from the Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease cohort. The main end point was major cardiovascular events (MACE: stroke, myocardial infarction and vascular death). Secondary endpoints included all-cause mortality and separate vascular events. Cause-specific proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the risk of DISH on all outcomes, and subdistribution hazard models were used to evaluate the effect of DISH on the cumulative incidence. All models were adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, blood pressure, diabetes, non-HDL cholesterol, packyears, renal function and C-reactive protein.

Results

DISH was present in 435 (9.4%) patients. After a median follow-up of 8.7 (IQR 5.0–12.0) years, 864 patients had died and 728 patients developed a MACE event. DISH was associated with an increased cumulative incidence of ischaemic stroke. After adjustment in cause-specific modelling, DISH remained significantly associated with ischaemic stroke (HR 1.55; 95% CI: 1.01, 2.38), but not with MACE (HR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.24), myocardial infarction (HR 0.88; 95% CI: 0.59, 1.31), vascular death (HR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.68, 1.27) or all-cause mortality (HR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.77, 1.16).

Conclusion

The presence of DISH is independently associated with an increased incidence and risk for ischaemic stroke, but not with MACE, myocardial infarction, vascular death or all-cause mortality.

Keywords: DISH, cardiovascular events, cardiovascular disease, mortality, ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, MACE

Rheumatology key messages.

The presence of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is associated with an increased incidence of ischaemic stroke.

Subjects with DISH have a 55% increased rate of ischaemic stroke.

Introduction

First described in 1950 by Forestier and Rotes-Querol [1], DISH is a common condition mainly affecting the spinal entheses, tendons and ligaments [2]. The formation of new bone at the anterolateral spine is the hallmark of DISH and, to date, its exact aetiology and pathophysiology remain poorly understood [2]. Patients affected with DISH are most often male and the prevalence of DISH increases with older age, with a prevalence of up to 42% reported for patients over the age of 65 years [3]. As DISH is frequently associated with hyperinsulinemia, obesity, type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, it is thought that metabolic derangements and low-grade inflammation are involved in the process of bone formation in DISH [2, 4–6]. DISH is largely asymptomatic, but symptoms of stiffness, back pain and reduced range of motion of affected segments are most commonly reported [2].

DISH has been associated with risk factors for cardiovascular disease [2, 7, 8], including increased coronary artery calcifications [7] and risk factors for stroke [9], yet, few studies have been published on incident cardiovascular outcomes in patients with DISH.

Limited data from a very small retrospective study suggested a relation between DISH and incident myocardial infarction [10]. To our best knowledge, large prospective cohort studies on the relation between DISH and risk of cardiovascular events and mortality have not yet been reported. Moreover, the relation between DISH and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) is still unknown. An independent relation between DISH and incident cardiovascular events may aid in the early identification and stratification of patients prone to cardiovascular death, as DISH can be easily scored on chest radiographs and computed tomography scans [11]. Furthermore, understanding DISH as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease may improve our understanding of the development of cardiovascular disease.

In the current study, we aimed to investigate whether the presence of DISH was related to future MACE and all-cause mortality, using data from a prospective cohort of patients with established vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease.

Methods

Patient population

The Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease (UCC-SMART) study is an ongoing single-centre prospective cohort study initiated in 1996, following patients with clinically manifest vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease [12]. All participants, aged 18–79 years, have been included with a referral to the University Medical Center Utrecht (UMC Utrecht), the Netherlands. At inclusion, patients underwent comprehensive vascular screening including a questionnaire, blood chemistry and ultrasonography. A standardized diagnostic protocol was followed consisting of physical examination and laboratory testing in the fasting state. The rationale and design of the UCC-SMART study has been described in detail previously [12]. The UCC-SMART study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the medical ethics committee of the UMC Utrecht (NL45885.041.13) and all included patients provided written informed consent. All patients with a digital chest radiograph within three months of inclusion in the UCC-SMART study were queried, yielding 4791 patients. Subsequently, 167 patients were excluded due to missing follow-up (n = 79), technical image deficiencies (n = 44), only AP radiograph being available (n = 34) and poor image quality (n = 10), ultimately resulting in 4624 available patients for inclusion in the current study.

Clinical and laboratory measurements

Measurements for individual patients were all performed within one day at the UMC Utrecht. An overnight fasting blood sample was taken to determine glucose, lipid levels and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). Body mass index was calculated by dividing the weight by the squared height (kg/m2). Waist circumference (cm) was measured halfway between the lower rib and the iliac crest in the standing position. Blood pressure was measured using a non-random sphygmomanometer three times simultaneously at the right and left upper arm in an upright position with an interval of 30 s. The mean of the last two measurements from the highest arm was used. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg and/or the usage of antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes mellitus at baseline was defined as either a referral diagnosis of diabetes, self-reported diabetes including use of glucose-lowering agents, glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l, or initiation of glucose lowering treatment within one year after inclusion with a glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l at baseline. The metabolic syndrome was defined according to the National Cholesterol Education Program criteria [13]. Hyperlipidaemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein cholesterol >2.6 mmol/l, or self-reported use of lipid-lowering drugs. Smoking habits and alcohol intake were assessed using questionnaires. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated with the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation [14].

Follow-up

The primary end point of our study was MACE: a composite outcome comprising non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and vascular death. Secondary endpoints were individual components of MACE and all-cause mortality. The exact definitions of events and outcomes of interest of this study are shown in Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online. Patients were asked to biannually complete a questionnaire on hospitalizations and outpatient clinic visits. In the case of a possible reported event, hospital discharge letters, other correspondence and investigations including data from the general practitioner, and the results of relevant laboratory and radiological examinations were retrieved. Based on this information, all events were audited by three independent members of the SMART study Endpoint Committee, comprising physicians from different departments. In case of disagreement, the opinion of other members of the Endpoint Committee was sought and final adjudication was based on the majority of the classifications obtained. Follow-up duration was defined as the period between enrolment to death from any cause, the occurrence of an event, date of loss to follow-up, or the preselected date of March 2018.

DISH assessment

Using the Resnick criteria [15], chest radiographs were scored for DISH by six certified readers (P.A.dJ., F.A.A.M.H., R.W., P.H.vdV., M.E.H. and W.F.; Entrustable Professional Activity level 4 or 5 for chest radiograph interpretation) from the department of Radiology of the UMC Utrecht. DISH is classified following the presence of ossification of at least four contiguous vertebrae; (relative) preservation of the intervertebral disc height; and the absence of apophyseal joint bony ankylosis or sacroiliac joint erosion.

Statistics

Normal distributed data were stated with means and standard deviations, and categorical variables with frequencies and percentages. Positive skewed data were transformed using logarithmic transformation. Differences between groups were analysed by calculating age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI.

Incidence rates per 1000 person-years were calculated. Regression modelling was performed in the presence of competing risks. To evaluate the effect of covariates on each outcome, cause specific hazards (CSH) models were used for the association between DISH and MACE, individual MACE endpoints, and all-cause mortality stated as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI. In subjects who are currently event-free, the regression coefficient of the CSH presents the relative effect of DISH on the relative change in the rate of an event of interest occurring. In addition, the subdistribution hazard ratio model of Fine and Gray was used to estimate the effect of DISH on the cumulative incidence function for the different outcomes. Adjusted cumulative incidence curves in the presence of competing risks were estimated for each outcome. In the case of multiple events in a patient, the first event was used in the analyses. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by the use of Schoenfeld residuals, which was not violated. In addition to the crude analysis, two models were used using a stepwise-adjusted approach including confounder selection based upon literature and etiologic considerations. In the second model, adjustments were made for confounders age and sex and a third model additionally adjusted for BMI, systolic blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, packyears, eGFR, non-high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol and hsCRP. We performed exploratory analysis with hypertension and hyperlipidaemia as covariates, instead of systolic blood pressure and non-HDL cholesterol. Furthermore, we explored whether age and a history of vascular disease influenced the relation between DISH and each outcome using interaction analyses for effect modification. Missing covariate data, including BMI (0.1%), non-HDL cholesterol (0.3%), systolic blood pressure (0.1%), packyears (0.1%) and renal function (0.3%) were imputed with single regression imputation using the mice package [16]. Data analysis was performed using R, version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 4624 patients in the current study, 435 (9.4%) satisfied criteria for DISH. The population characteristics for subjects with and without DISH are listed in Table 1. Patients with DISH were older (65.7 vs 57.6 years) and more often male (86% vs 68%) compared with patients without DISH. Moreover, DISH patients more often had higher pulse pressure (64 mmHg vs 58 mmHg), BMI (28.6 kg/m2vs 26.9 kg/m2) and waist circumference (102 cm vs 94.9 cm), and more hypertension (30.8% vs 24.3%), diabetes (31% vs 21%), and the metabolic syndrome (65.1% vs 52.8%). After adjusting for age and sex, DISH was significantly associated with presence of the metabolic syndrome: OR 1.76 (95% CI: 1.42, 2.18) and the presence of diabetes: OR 1.54 (95% CI: 1.22, 1.93). Systolic blood pressure (per 1 mmHg), the presence of hypertension, and pulse pressure (per 1 mmHg) were also significantly associated with DISH.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics and logistic regression analysis of factors associated with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis

| Variable | Total group (n = 4624) | DISH group (n = 435) | No DISH group (n = 4189) | Age and sex adjusted OR (95% CI) | Age and sex adjusted P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 58.4 (11.2) | 65.7 (7.8) | 57.6 (11.2) | 2.3 (2.0, 2.6)c | <0.001 |

| Sex (male), % | 69.6% | 85.5% | 68% | 2.86 (2.17, 3.85) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (s.d.) | 27.1 (4.5) | 28.6 (4.5) | 26.9 (4.5) | 1.12 (1.09, 1.15) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (s.d.) | 95.6 (13.0) | 102.0 (12.1) | 94.9 (13.0) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 21.8% | 31.0% | 21.0% | 1.54 (1.22, 1.93) | <0.001 |

| Glucose (mmol/L), mean (s.d.) | 6.4 (1.9) | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.9) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.15) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%), mean (s.d.) | 6.0 (1.1) | 6.1 (1.0) | 6.0 (1.1) | 1.15 (1.02, 1.28) | 0.01 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2), mean (s.d.) | 78 (19) | 73 (18) | 79 (19) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.14 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg), mean (s.d.) | 58.2 (15) | 64 (16) | 58 (15) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (s.d.) | 141 (22) | 146 (22) | 141 (21) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.01) | 0.002 |

| Hypertension, %a | 24.9% | 30.8% | 24.3% | 1.43 (1.14, 1.79) | 0.002 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L), mean (s.d.) | 1.25 (0.38) | 1.20 (0.36) | 1.25 (0.38) | 0.71 (0.51, 0.96) | 0.03 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mmol/L), mean (s.d.) | 3.66 (1.30) | 3.64 (1.57) | 3.7 (1.27) | 1.16 (1.07, 1.26) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, %a | 42.2% | 38.4% | 42.7% | 1.17 (0.94, 1.44) | 0.16 |

| hsCRP (mg/L), mean (s.d.)b | 1.25 (0.78) | 1.29 (0.76) | 1.25 (0.78) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) | 0.68 |

| Metabolic syndrome, %a | 53.9% | 65.1% | 52.8% | 1.76 (1.42, 2.18) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (current vs former), %a | 73.1% | 77.2% | 72.7% | 1.03 (0.80, 1.32) | 0.83 |

| Packyears, mean (s.d.) | 17.5 (19.5) | 18.6 (19.9) | 17.4 (19.4) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.27 |

| Drinking (current vs former), %a | 80.4% | 85.7% | 79.9% | 1.13 (0.84, 1.55) | 0.42 |

| History of vascular disease, %a | 71.4% | 78.0% | 70.6% | 0.66 (0.51, 0.87) | 0.002 |

Percentages were calculated after excluding missing cases from the denominator. bLog-transformed. cAge per 10 years. Data are displayed using number (percentage) for categorical variables, and mean (s.d.) for normally continuous data. HDL: high density lipoprotein; hsCRP: high sensitivity CRP; OR: odds ratio.

Events and incidence rates during follow-up

The median follow up was 8.7 (interquartile range: 5.0–12.0) years, during which 864 (18.7%) patients died, including 356 deaths attributable to a vascular cause. In addition, 728 MACE, 173 cases of ischaemic stroke and 283 cases of myocardial infarction occurred during the follow-up period. Incident rates for patients with and without DISH on mortality, ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction are listed in Table 2. The cumulative incidence functions for each different outcome between the DISH and no DISH groups are displayed in Supplementary Figs S1–S5, available at Rheumatology online. In subdistribution hazard modelling, the presence of DISH was associated with an increased incidence of ischaemic stroke (HR 1.53; 95% CI: 1.00, 2.35), but not with MACE (HR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.78, 1.21), myocardial infarction (HR 0.89; 95% CI: 0.60, 1.33), vascular death (HR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.68, 1.23) or all-cause mortality (HR 0.91; 95% CI: 0.75, 1.11) after full adjustments. A more detailed description of subdistribution hazard models is shown in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Fig. S6, available at Rheumatology online.

Table 2.

Incidence rates between DISH and no DISH group for different outcomes

| Total group (n = 4624) | DISH group (n = 435) | no DISH group (n = 4189) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | |||

| Sum person-years | 40 372 | 3812 | 36 559 |

| No. of cases | 864 | 113 | 751 |

| Incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 21.4 | 29.6 | 20.5 |

| MACE | |||

| Sum person-years | 37 955 | 3569 | 34 387 |

| No. of cases | 728 | 92 | 636 |

| Incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 19.2 | 25.8 | 18.5 |

| Myocardial infarction | |||

| Sum person-years | 38 767 | 3672 | 35 094 |

| No. of cases | 283 | 29 | 254 |

| Incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 7.3 | 7.9 | 7.2 |

| Ischemic stroke | |||

| Sum person-years | 39 355 | 3684 | 35 672 |

| No. of cases | 173 | 27 | 146 |

| Incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 4.4 | 7.3 | 4.0 |

| Vascular death | |||

| Sum person-years | 40 372 | 3812 | 36 559 |

| No. of cases | 356 | 50 | 306 |

| Incidence rate per 1000 person-years | 8.8 | 13.1 | 8.4 |

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events.

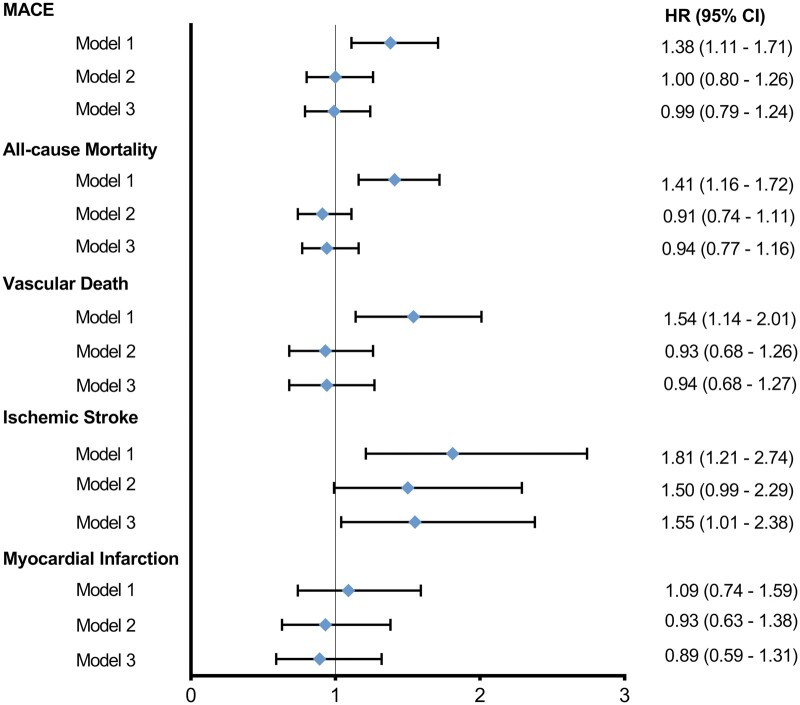

DISH in relation to mortality and cardiovascular events

Cause-specific cox regression analyses for the total DISH group in relation to all-cause mortality, vascular and non-vascular death, and cardiovascular outcomes are listed in Table 3 and Fig. 1. In crude analysis, the presence of DISH was significantly associated with MACE (HR 1.38; 95% CI: 1.11, 1.71), all-cause mortality (HR 1.41; 95% CI: 1.16, 1.72), vascular death (HR 1.54; 95% CI: 1.14, 2.01) and ischaemic stroke (HR 1.81; 95% CI: 1.21, 2.74), but not with myocardial infarction (HR 1.09; 95% CI: 0.74–1.59).

Table 3.

DISH and risk of mortality and cardiovascular events

| Model | MACE |

All-cause mortality |

Vascular death |

Ischaemic Stroke |

Myocardial infarction |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | ||

| Total DISH group | 1 | 1.38 (1.11, 1.71)* | 1.41 (1.16, 1.72)* | 1.54 (1.14, 2.01)* | 1.81 (1.21, 2.74)* | 1.09 (0.74, 1.59) |

| 2 | 1.00 (0.80, 1.26) | 0.91 (0.74, 1.11) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.26) | 1.50 (0.99, 2.29) | 0.93 (0.63, 1.38) | |

| 3 | 0.99 (0.79, 1.24) | 0.94 (0.77, 1.16) | 0.94 (0.68, 1.27) | 1.55 (1.01, 2.38)* | 0.89 (0.59, 1.31) |

Model 1: DISH crude.

Model 2: adjusted for age and sex.

Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, non-HDL cholesterol, packyears, renal function, and log-transformed hsCRP.

P < 0.05.

HR: hazard ratio; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular event.

Fig. 1.

Unadjusted and adjusted cause-specific hazard ratios for each outcome of interest

Model 1: diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis crude. Model 2: adjusted for age and sex. Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, non-HDL cholesterol, packyears, renal function and log-transformed hsCRP. HR: hazard ratio; MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events.

These relations became attenuated after adjusting for confounders age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors, for MACE (HR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.79, 1.24), all-cause mortality (HR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.77, 1.16), vascular death (HR 0.94; 95% CI: 0.68, 1.27), and myocardial infarction (HR 0.89; 95% CI: 0.59, 1.31). The presence of DISH was independently associated with ischaemic stroke (HR 1.55; 95% CI: 1.01, 2.38). These results did not change after exploratory analysis with hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (data not shown). Likewise, the relation between DISH and ischaemic stroke was unaffected by the inclusion of a history of vascular disease (P-interaction = 0.93) or age (P-interaction = 0.30) in the final model.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, the presence of DISH was associated with an increased incidence of ischaemic stroke. Furthermore, we found that the presence of DISH was associated with a 55% increased rate of ischaemic stroke, which remained after correcting for age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors. No other independent relations were found for MACE, all-cause mortality, vascular death or myocardial infarction.

No study has previously assessed the relation between DISH and MACE. Other outcomes have been reported in a small retrospective study by Glick et al. [10] who found an association between DISH and myocardial infarction, but not with stroke, all-cause mortality and vascular death, which were solely adjusted for obesity, diabetes and dyslipidaemia. Furthermore, their study had a limited sample size and a patient population without history of cardiovascular disease and which was largely female.

While the exact pathophysiology of DISH remains undetermined, various mechanisms have been hypothesized to contribute to the development of DISH including hyperinsulinemia and inflammation [2, 17]. Recently, Mader et al. [6] reviewed the evidence of the involvement of inflammation in the pathogenesis of DISH. Local inflammation in entheses, which can be either primary or secondary to metabolic derangements, may contribute to bone formation in DISH. Previous research has shown that elevated levels of hsCRP, a marker of inflammation, are associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease [18]. Increased inflammation is known to facilitate the development of atherosclerosis, leading to increased mortality, morbidity and cardiovascular events in various rheumatologic disorders [19–23].

Patients with DISH have significantly more cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery calcifications [2, 7]. Yet, we did not find an association between DISH and myocardial infarction in our cohort. Increased calcium scores are strong independent predictors for future cardiovascular events, irrespective of present cardiovascular risk factors [24]. The relation between DISH and coronary artery calcifications seems to be more complex than initially thought. The role of calcification formation in coronary artery disease is not fully elucidated, but a possible reason is that calcifications may limit plaque growth and rupture and are in essence a positive healing effect in the coronaries [25]. Nonetheless, a satisfactory explanation for this (dis)association in relation to DISH is yet to be found.

While myocardial infarction is predominantly caused by unstable plaques in the coronaries, the aetiology of ischaemic stroke is more heterogeneous. Ischaemic stroke can be caused by large-artery atherosclerosis, large-artery stiffening, small-vessel disease, or cardioembolisms [26]. DISH has been previously linked with middle cerebral artery calcification in a small retrospective study [9], supporting the association in our study, though the exact relation between DISH and small-vessel disease is not known. In the intracranial vessels it is postulated that the role of calcifications may differ from the coronary bed. People prone to bone formation may form these calcifications more easily. Intracranial calcifications are common and may result in higher pulsatility, which may be detrimental for ‘soft organs’ such as the brain [27].

The association of stroke in DISH patients can perhaps be (partly) explained by the link between DISH and arterial wall stiffness and vessel pulsatility. Vascular calcification in the ascending aorta, intracranial or extracranial carotid arteries may directly increase arterial stiffness [28], and determinants of arterial stiffness, including pulse pressure, systolic blood pressure and renal function are strong independent predictors for cardiovascular events, including stroke [29, 30]. In population-based cohorts, systolic blood pressure was significantly higher for subjects with DISH [31], which was also the case in our cohort. DISH subjects also had higher pulse pressure compared with non-DISH subjects.

Both DISH and cardiovascular disease share common traditional cardiovascular risk factors including older age, male sex, obesity, hypertension and diabetes mellitus.

As research on this subject is still emerging and in an early phase, cardiovascular disease remains often underdiagnosed in patients with DISH. It is important to recognize that patients with DISH seem to be a group at risk for developing stroke.

We acknowledge that our patient population is one more prone to developing DISH as well as cardiovascular events. Whether the relation between DISH and ischaemic stroke would hold true in patient samples derived from the other populations, including lower risk patients, warrants further investigation.

Strengths and limitations

Major strengths of the current study include, firstly, the prospective cohort design and large patient population with long and complete follow-up. Secondly, the assessment of endpoints was well documented, which reduced the chance of subjective end point assessment. Thirdly, the extensive and accurate documentation of cardiovascular risk factors made it possible to assess the independent relations between DISH and mortality and cardiovascular events.

Nevertheless, some limitations of our study should also be noted. The inclusion of patients using chest radiographs within three months might have increased the selection of patients with a recent (cardiovascular) event, which may have resulted in increased incident rates. Secondly, as it has been established that DISH is a progressive disease [32], another limitation is that earlier (but still active and progressive) forms of DISH may not fulfil the Resnick criteria yet, which might lead to an underestimation of some associations, as DISH was not re-assessed during follow-up or at the time of the occurrence of an event. Future studies into the development of cardiovascular disease in relation to progression of DISH may be warranted. Finally, DISH may lead to back pain [2], which could potentially impact the usage of (over the counter) NSAID. Depending on the type of NSAID, various cardiovascular adverse effects have been associated with NSAIDs, including myocardial infarction [33]. As this was not documented in our study at baseline, we were not able to include NSAID usage in our analyses.

Conclusion

In this first prospective cohort study, which to our knowledge is among the largest study on cardiovascular events and mortality in DISH, we found that DISH was independently related to increased incidences and rates of ischaemic stroke, but not with MACE, myocardial infarction, vascular death and all-cause mortality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the research nurses; R. van Petersen (data-manager); B. van Dinther (study manager) and the Members of the Utrecht Cardiovascular Cohort-Second Manifestations of ARTerial disease-Studygroup (UCC-SMART-Studygroup): F.W. Asselbergs and H.M. Nathoe, Department of Cardiology; G.J. de Borst, Department of Vascular Surgery; M.L. Bots and M.I. Geerlings, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care; M.H. Emmelot, Department of Geriatrics; P.A. de Jong and T. Leiner, Department of Radiology; A.T. Lely, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology; N.P. van der Kaaij, Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery; L.J. Kappelle and Y.M. Ruigrok, Department of Neurology; M.C. Verhaar, Department of Nephrology; F.L.J. Visseren (chair) and J. Westerink, Department of Vascular Medicine, University Medical Center Utrecht and Utrecht University.

Funding: No specific funding was received from any bodies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors to carry out the work described in this article.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The informed consent that was signed by the study participants is not compliant with publishing individual data in an open access institutional repository or as supporting information files with the published paper. However, a data request can be sent to the SMART Steering Committee at uccdatarequest@umcutrecht.nl.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

Contributor Information

Netanja I Harlianto, Department of Radiology; Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University Medical Center Utrecht and Utrecht University, Utrecht.

Nadine Oosterhof, Department of Radiology.

Wouter Foppen, Department of Radiology.

Marjolein E Hol, Department of Radiology.

Rianne Wittenberg, Department of Radiology, Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam.

Pieternella H van der Veen, Department of Radiology.

Bram van Ginneken, Department of Medical Imaging, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen and .

Firdaus A A Mohamed Hoesein, Department of Radiology.

Jorrit-Jan Verlaan, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University Medical Center Utrecht and Utrecht University, Utrecht.

Pim A de Jong, Department of Radiology.

Jan Westerink, Department of Vascular Medicine, University Medical Center Utrecht and Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands.

for the UCC-SMART-Studygroup:

R van Petersen, B van Dinther, F W Asselbergs, H M Nathoe, G J de Borst, M L Bots, M I Geerlings, M H Emmelot, P A de Jong, T Leiner, A T Lely, N P van der Kaaij, L J Kappelle, Y M Ruigrok, M C Verhaar, F L J Visseren, and J Westerink

References

- 1. Forestier J, Rotes-Querol J.. Senile ankylosing hyperostosis of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis 1950;9:321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mader R, Verlaan JJ, Buskila D.. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: clinical features and pathogenic mechanisms. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2013;9:741–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holton KF, Denard PJ, Yoo JU. et al. Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Group. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis and its relation to back pain among older men: the MrOS Study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011;41:131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harlianto NI, Westerink J, Foppen W. et al. Visceral adipose tissue and different measures of adiposity in different severities of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. J Personal Med 2021;11:663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kiss C, Szilágyi M, Paksy A, Poór G.. Risk factors for diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: a case-control study. Rheumatology 2002;41:27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mader R, Pappone N, Baraliakos X. et al. Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis (DISH) and a possible inflammatory component. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2021;23:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oudkerk SF, Mohamed Hoesein FAA, PThM Mali W. et al. Subjects with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis have an increased burden of coronary artery disease: an evaluation in the COPDGene cohort. Atherosclerosis 2019;287:24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zincarelli C, Iervolino S, Di Minno MN. et al. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis prevalence in subjects with severe atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1765–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miyazawa N, Akiyama I.. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis associated with risk factors for stroke: a case-control study. Spine 2006;31:E225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Glick K, Novofastovski I, Schwartz N, Mader R.. Cardiovascular disease in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH): from theory to reality-a 10-year follow-up study. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oudkerk SF, de Jong PA, Attrach M. et al. Diagnosis of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis with chest computed tomography: inter-observer agreement. Eur Radiol 2017;27:188–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Simons PC, Algra A, van de Laak MF, Grobbee DE, van der Graaf Y.. Second manifestations of ARTerial disease (SMART) study: rationale and design. Eur J Epidemiol 1999;15:773–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Resnick D, Niwayama G.. Radiographic and pathologic features of spinal involvement in diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH). Radiology 1976;119:559–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K.. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45:1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mueller MB, Blunk T, Appel B. et al. Insulin is essential for in vitro chondrogenesis of mesenchymal progenitor cells and influences chondrogenesis in a dose-dependent manner. Int Orthop 2013;37:153–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilson AM, Ryan MC, Boyle AJ.. The novel role of C-reactive protein in cardiovascular disease: risk marker or pathogen. Int J Cardiol 2006;106:291–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Di Minno MN, Iervolino S, Lupoli R. et al. Cardiovascular risk in rheumatic patients: the link between inflammation and atherothrombosis. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012;38:497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agca R, Heslinga SC, van Halm VP, Nurmohamed MT.. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic inflammatory joint disorders. Heart 2016;102:790–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castañeda S, Nurmohamed MT, González-Gay MA.. Cardiovascular disease in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016;30:851–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liew JW, Ramiro S, Gensler LS.. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2018;32:369–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Castañeda S, Martín-Martínez MA, González-Juanatey C. et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and associated risk factors in Spanish patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases attending rheumatology clinics: baseline data of the CARMA Project. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2015;44:618–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE.. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:434–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bartstra JW, van den Beukel TC, Van Hecke W. et al. Intracranial arterial calcification: prevalence, risk factors, and consequences: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:1595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fisher M, Folland E.. Acute ischemic coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke: similarities and differences. Am J Ther 2008;15:137–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Tuijl RJ, Ruigrok YM, Velthuis BK. et al. Velocity pulsatility and arterial distensibility along the internal carotid artery. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e016883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mackey RH, Venkitachalam L, Sutton-Tyrrell K.. Calcifications, arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis. Adv Cardiol 2007;44:234–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu FD, Shen XL, Zhao R. et al. Pulse pressure as an independent predictor of stroke: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Clin Res Cardiol 2016;105:677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dad T, Weiner DE.. Stroke and chronic kidney disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and management across kidney disease stages. Semin Nephrol 2015;35:311–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pariente-Rodrigo E, Sgaramella GA, Olmos-Martínez JM. et al. Relationship between diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, abdominal aortic calcification and associated metabolic disorders: data from the Camargo Cohort. Med Clin 2017;149:196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kuperus JS, de Gendt EEA, Oner FC. et al. Classification criteria for diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis: a lack of consensus. Rheumatology 2017;56:1123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schjerning AM, McGettigan P, Gislason G.. Cardiovascular effects and safety of (non-aspirin) NSAIDs. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:574–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The informed consent that was signed by the study participants is not compliant with publishing individual data in an open access institutional repository or as supporting information files with the published paper. However, a data request can be sent to the SMART Steering Committee at uccdatarequest@umcutrecht.nl.