Abstract

Purpose:

The para-aortic nodes are a common site of recurrence of endometrial cancer, especially among patients previously treated with pelvic radiation. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) can be used to deliver a tumoricidal dose to para-aortic disease while minimizing dose to normal adjacent structures. In this study, we reviewed the outcomes of patients treated with IMRT for unresected or incompletely resected para-aortic recurrences of primary uterine cancer.

Methods:

Between 2000 and 2009, 27 patients with unresected (19 patients) or incompletely resected (8 patients) para-aortic relapse of endometrial cancer were treated with curative intent using IMRT. The para-aortic basin was generally treated to a dose of 45–50 Gy, and gross disease was treated to a mean total dose of 61.7 Gy (range, 54–66 Gy). Seventeen patients (63%) received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Fifteen (56%) received cisplatin concurrently with IMRT. Rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) following salvage IMRT were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method, and differences between subgroups were assessed using the log-rank statistic.

Results:

Of the 27 patients, 19 (70%) had local control of para-aortic disease after a median follow-up time of 25 months (range, 4–83 months). Two-year actuarial OS and PFS rates were 63% and 53%, respectively. Five patients (19%) experienced severe late gastrointestinal toxic effects (grade 3–5).

Conclusions:

IMRT can serve as salvage therapy of para-aortic recurrence of endometrial cancer. However, the risk of severe gastrointestinal toxic effects is high, and care should be taken during treatment planning to minimize the dose to the small bowel.

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic cancer in the United States; approximately 40,000 cases are diagnosed per year.1 Surgery is the the mainstay of treatment, with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy tailored on the basis of operative findings. Despite optimal staging and multimodality therapy, some women still develop regional recurrences in the pelvis or paraaortic lymph nodes. The risk of para-aortic involvement is particularly high among stage IIIC patients treated initially with pelvic irradiation. In these patients, paraaortic nodes are the most frequent site of relapse.2

Currently, evidence-based guidelines for salvage of nodal relapse are lacking, and management varies widely, from aggressive surgical therapy followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy to palliative chemotherapy alone.3, 4 Because of their proximity to small bowel, duodenum, kidneys, and other critical structures, treatment of para-aortic recurrences with radiation therapy is challenging, and concern about injury to these structures has tended to limit the dose and effectiveness of radiotherapy. During the past 10 years, the advent of intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) has made it possible to deliver high-dose conformal treatment to gross disease in the para-aortic nodes while limiting the dose to normal tissues. The purpose of this study was to investigate overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), para-aortic control, and toxic effects in patients with para-aortic recurrences treated definitively with IMRT.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

Our institution’s tumor registry and radiation oncology databases were searched to identify patients treated with definitive IMRT for recurrent endometrial cancer in the para-aortic nodes between 2000 and 2009. Nodes were classified as being para-aortic if they were located between the superior edge of the T12 vertebra and the inferior edge of the L5 vertebrae. Histologic subtypes allowed in our study included endometrioid carcinoma and high-risk uterine cancers such as papillary serous carcinoma, malignant mixed mullerian tumor, clear cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, and mixed carcinomas that contained high-risk subtypes. Patients were included if they underwent irradiation of the para-aortic recurrence with curative intent. Thus, patients treated with radiotherapy to adjuvant doses following complete resection were not included, but patients who did not undergo resection and patients whose recurrence was incompletely resected (based on surgeon report or post-operative imaging) were included. Patients with synchronous recurrences in the pelvis were included provided that these patients had not previously had pelvic radiotherapy and so could also be treated definitively in the pelvis. Patients with synchronous recurrences at other sites were excluded.

We identified 27 patients who fit these inclusion criteria. Data regarding patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics were abstracted from the hospital and radiation oncology records. Patients no longer followed at our institution were contacted annually by the institution’s Department of Patient Studies to obtain information about tumor status and general medical problems. This information was recorded in each patient’s medical record. The Institutional Review Board granted permission for this study and procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Management at Initial Diagnosis

Twenty four (89%) of the 27 patients in this study underwent surgical resection and adjuvant therapy for their initial presentation at outside facilities, while three (11%) received treatment at our institution for their initial diagnosis of endometrial cancer. All patients underwent total abdominal hysterectomy. The use of lymphadenectomy or lymph node sampling, adjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant external-beam radiotherapy, and intracavitary brachytherapy varied according to clinical presentation and local patterns of care (Table 1). Fourteen patients (52%) had adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy as part of their initial treatment, of which 3 received this treatment at our institution.

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics at time of initial therapy

| Characteristic | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 27 | 100 |

| Age, years | ||

| <50 | 2 | 7 |

| 50–69 | 18 | 67 |

| ≥70 | 7 | 26 |

| Histologic subtype | ||

| Endometrioid | 14 | 52 |

| Papillary serous | 1 | 4 |

| MMMT | 5 | 19 |

| Mixed1 | 6 | 22 |

| Poorly differentiated | 1 | 4 |

| 2009 FIGO2 stage | ||

| IA | 10 | 37 |

| IB | 4 | 15 |

| II | 1 | 4 |

| IIIA | 1 | 4 |

| NIB | 0 | 0 |

| IIIC1 | 5 | 18 |

| IIIC2 | 3 | 11 |

| IV | 2 | 7 |

| Unknown | 1 | 4 |

| Lymph node sampling | ||

| Pelvic only | 10 | 37 |

| Pelvic and para-aortic | 7 | 26 |

| Unspecified | 1 | 4 |

| Not performed | 9 | 33 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 14 | 52 |

| No | 13 | 48 |

| Pelvic radiotherapy | ||

| Yes | 14 | 52 |

| No | 13 | 48 |

| Brachytherapy | ||

| Yes | 8 | 30 |

| No | 19 | 70 |

5/6, endometrioid and papillary serous; 1/6, endometrioid and clear cell.

FIGO, International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology; MMMT, malignant mixed Mullerian tumor.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Recurrent Disease

Recurrence of endometrial cancer was suspected because of radiographic appearance on computed tomography, positron emission tomography, or magnetic resonance during imaging-based surveillance and/or rising CA-125 level. Among the 27 patients in this study, 22 (81%) had pathologic confirmation of disease in the para-aortic nodes via surgical or needle biopsy. Three patients were diagnosed with para-aortic recurrence on the basis of the radiographic appearance of the para-aortic nodes in the presence of synchronous, pathologically confirmed disease in the pelvis (in total there were 4 patients with synchronous recurrence in both pelvis and para-aortic nodes). Two of the 27 patients were presumed to have a para-aortic recurrence because of radiographic evidence and concurrent elevation of CA-125.

Modalities used in the treatment of para-aortic recurrences are summarized in Table 2. Typically, decision to perform an initial resection or proceed with definitive radiation treatment was made after multidisciplinary discussion involving gynecologic and radiation oncologists, pathologists, and diagnostic imaging specialists. Among the 27 patients in the study, 8 (30%) had partial surgical debulking, and 17 patients (63%) received neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy. Fifteen patients (56%) received concurrent cisplatin with their radiotherapy regimen, which was most commonly delivered weekly at 40 mg/m2.

Table 2.

Timing and treatment of para-aortic recurrences

| Characteristic | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 27 | 100 |

| Time after TAH1, months | ||

| <12 | 5 | 19 |

| 12–23 | 10 | 37 |

| 24–35 | 5 | 19 |

| >36 | 7 | 26 |

| Para-aortic node dissection | ||

| Yes | 8 | 30 |

| No | 19 | 70 |

| Neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 17 | 63 |

| No | 10 | 37 |

| Radiation dose, Gy | ||

| >60 | 18 | 67 |

| ≤60 | 9 | 33 |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | 15 | 56 |

| No | 12 | 44 |

TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy.

Radiotherapy was delivered via IMRT technique. Twenty-five patients (93%) received treatment to the entire para-aortic nodal basin in addition to grossly involved nodes. Of the 13 women who did not receive pelvic radiotherapy prior to initial presentation, six received treatment to the whole pelvis in addition to the para-aortic nodal basin. With regard to technique, the para-aortic and/or pelvic nodal basins were treated with IMRT to 45–50 Gy with a 0.7- to 1-cm margin. The para-aortic basin was defined as the region anterior to the vertebral bodies from the top of the L5 or S1 vertebral body (or the superior border of prior pelvic radiotherapy) to the top of the T12 vertebral body. The grossly involved para-aortic nodes were treated with an integrated, sequential, and/or combined boost to bring the total mean dose of 61.7 Gy (range, 54–66 Gy).

Follow-up

After the completion of treatment, patients were usually seen at 3-month intervals for 2–3 years, at 6-month intervals for an additional 2 years, and then yearly. Abdomino-pelvic imaging was not done routinely for patients treated for early-stage endometrioid carcinoma; for these patients, imaging that identified recurrence was precipitated by symptoms. For patients with stage III endometrioid carcinoma or high-risk histologic subtypes, imaging was done every six months or annually at the discretion of the follow-up physician.Toxic effects were graded according to Radiation Therapy Oncology Group criteria.5, 6

Statistical Analysis

Time intervals were measured from the date of para-aortic recurrence. For calculations of PFS, progressive disease at the treated para-aortic nodes, new loco-regional recurrence in the pelvis or para-aortic nodes, and the appearance of distant metastases were scored as events. Actuarial OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method with differences between groups analyzed using the log-rank statistic. For para-aortic control, treatment response was evaluated by reviewing all surveillance images obtained after the completion of radiotherapy. Progression in nodal size or development of new para-aortic nodal disease was scored as para-aortic failure.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Para-aortic Recurrence

The median time to para-aortic recurrence after hysterectomy was 26 months (range, 6.5–117 months). The L3 vertebral body was the most common site of para-aortic recurrence (Supplementary Figure 1). The mean maximum axial diameter of involved nodes prior to local therapy (surgical resection attempt or radiotherapy) was 2.9 cm (range, 1–5 cm; 95% confidence interval, 2.4–3.4 cm). Three patients had concurrent disease in two or more noncontiguous para-aortic locations, and four patients had concurrent gross disease in the pelvis. For two patients, disease at the para-aortic nodes represented a second, isolated relapse after local control of a prior pelvic recurrence with pelvic radiotherapy.

Among the 14 patients who had undergone postoperative pelvic radiotherapy at their initial diagnosis, there were 16 nodal recurrences. The mean distance from the superior border of the prior pelvic field to the epicenter of the nodal recurrence was 8.0 cm (range, 0.5–17 cm). Eleven (69%) of the recurrences were located more than 5 cm from the superior border of the prior pelvic fields.

Para-aortic Control

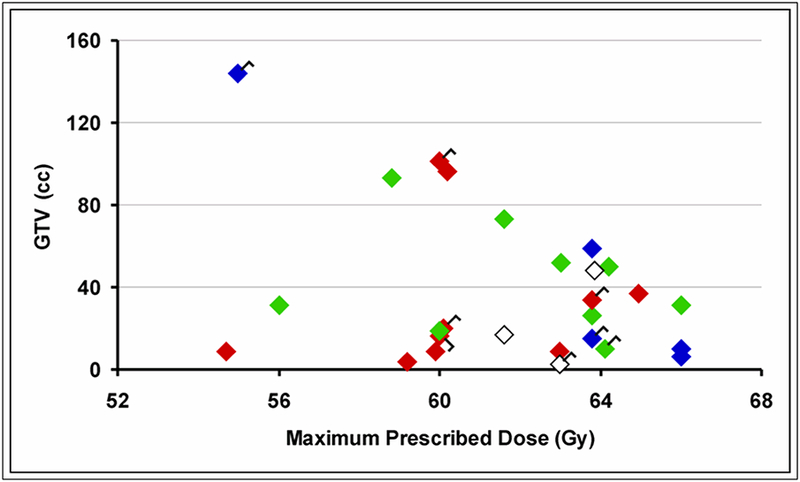

At a median follow-up time of 25 months (range, 4–83 months), para-aortic control following IMRT occurred in 19 patients (70%). Figure 1 illustrates radiographic responses in relation to the prescribed dose and the contoured gross tumor volume (GTV) for all patients. No clear pattern of dose response for local control was evident in this cohort. An example of complete resolution following treatment is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Radiographic response of involved para-aortic nodes following definitive therapy according to gross tumor volume (GTV) at time of radiotherapy and maximum prescribed dose. Red = complete response. Green = partial response or stable disease. Blue = para-aortic progression or relapse. White = unknown. Flags are tagged to the responses for the eight patients who underwent partial surgical debulking.

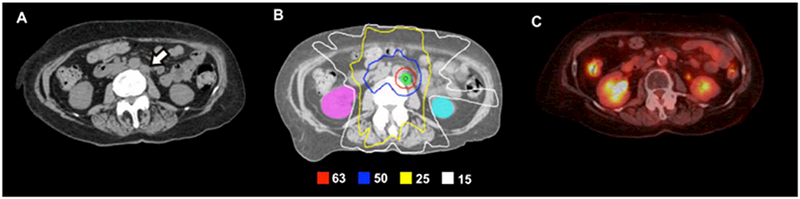

Figure 2.

A 69-year-old woman with stage IC, grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma with pathologically confirmed para-aortic recurrence 3 years after initial therapy. The recurrence was refractory to systemic chemotherapy and was subsequently treated with definitive IMRT alone. (A) Preradiotherapy axial computed tomography (CT) image demonstrating the enlarged para-aortic node (white arrow). (B) IMRT plan to deliver 63 Gy to the gross node in 28 daily fractions. The para-aortic nodal basin was treated to 50.4 Gy. (C) Surveillance positron emission tomography/CT scan obtained approximately 4 years following IMRT demonstrates complete resolution of the involved node. The patient was also without evidence of disease elsewhere.

There was only one isolated para-aortic failure following salvage IMRT, which occurred in a patient with endometrioid disease treated early in our experience. The nodal GTV was treated to 55 Gy, and recurrence eventually occurred at the field margin 3 years after completion of IMRT. Four patients experienced synchronous para-aortic failure in the setting of distant metastases (two with uterine papillary serous carcinoma and two with malignant mixed mullerian tumor). Three patients were not evaluated for local recurrence due to absence of abdominal surveillance imaging at the time of this study or death from other causes.

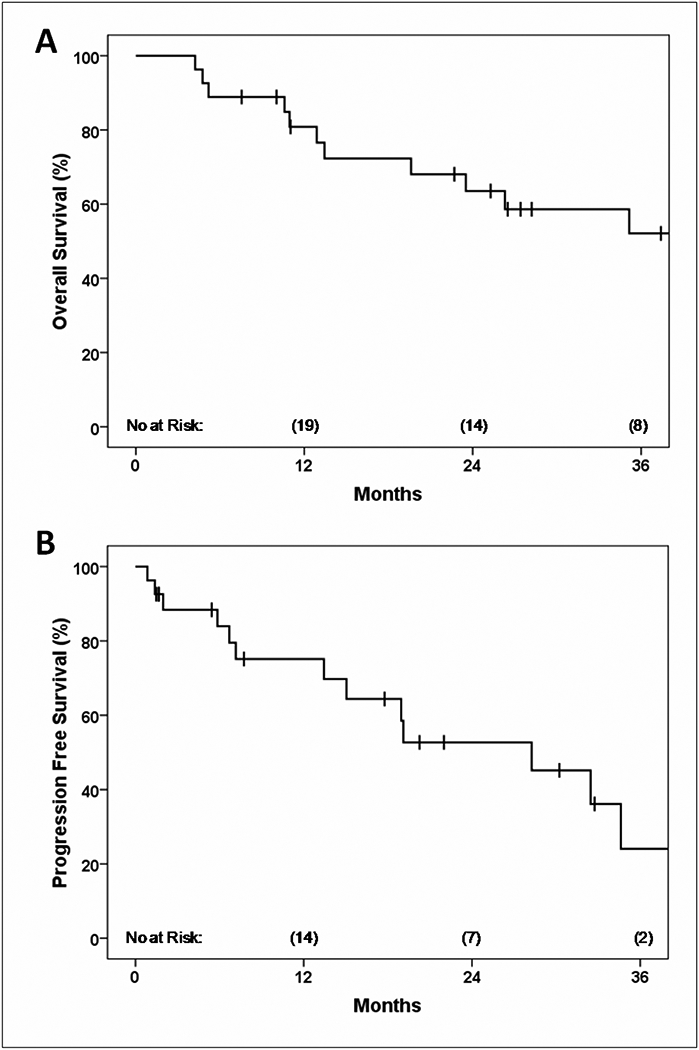

Progression-Free Survival and Overall Survival

Thirteen patients (48%) experienced disease progression at any site after paraaortic IMRT. Distant metastatic disease was the most common site of failure, occurring in 11 of the 13 relapses (85%). Of the remaining two, one patient had isolated para-aortic recurrence as described above, while the other had an unspecifiedrelapse discovered at an outside hospital whose records were unavailable for review. From the date of para-aortic recurrence, 2-year OS and PFS rates were 63% and 53%, respectively (Figure 3). Median follow-up among the 16 survivors (59%) in the cohort was 28 months.

Figure 3.

Overall survival (A) and PFS (B) from the date of para-aortic nodal recurrence.

Toxic Adverse Effects

Four patients (15%) required hospitalization during IMRT for severe nausea (grade 2 toxic effect); three of these patients received concurrent chemotherapy with radiotherapy. No acute grade 3, 4, or 5 gastrointestinal toxic effects occurred. With regard to late toxicity, two patients required temporary hospitalization for medical management of partial small bowel obstruction (grade 2 toxic effect). Furthermore, five patients had grade 3 or greater complications, all of which involved the gastrointestinal tract: One patient had a small bowel obstruction requiring surgical intervention (grade 3). Three patients experienced small bowel perforations or fistulae (grade 4). Finally, one patient experienced a duodenal fistula and subsequently died of hematemesis (grade 5). Treatment characteristics of the 5 patients with grade 3–5 late toxic effects are summarized in Table 3. All five were treated to more than 60 Gy to the GTV.

Table 3.

Treatment characteristics of patients experiencing grade 3–5 toxic effects after definitive radiotherapy for para-aortic recurrence

| Grade of toxic effect | Type of toxic effect | Age, years | Location of para-aortic recurrence | GTV1 (cc) | Prior Pelvic RT | Surgical debulking | Neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy | Concurrent chemotherapy | Maximum dose (Gy) / fraction no. | Small bowel maximum / mean dose (Gy) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Duodenal fistula | 59 | L4–L5 | 31 | No | No | Yes | Cisplatin | 66 / 30 | 64.3 / 21.5 |

| 4 | Small bowel fistula | 63 | T12 | 2.6 | No | Yes | No | None | 63 / 28 | 56.1 / 24.7 |

| 4 | Small bowel perforation | 54 | L3–L4 | 15 | No | Yes | Yes | Cisplatin | 63.8 / 29 | 69.0 / 26.0 |

| 4 | Duodenal fistula | 78 | L3 | 17 | Yes | No | Yes | Cisplatin | 61.6 / 28 | 61.1 / 23.5 |

| 3 | Small bowel obstruction | 53 | L1–L2 | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cisplatin | 64.12 / 28 | 65 / 16.2 |

GTV, gross tumor volume.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to review outcomes following IMRT for para-aortic relapse of a primary endometrial malignancy. Our findings indicate that a significant proportion of patients can expect excellent local control and that some patients can expect long-term survival with this approach. Actuarial 2-year overall survival and relapse-free survival rates 2 years were modestly worse than those seen in patients with recurrences at the vaginal cuff treated with definitive radiotherapy, but this may reflect the fact doses that are achieved at the vaginal cuff are significantly higher (~75 Gy) than what can be safely delivered to the para-aortic nodes.7, 8

Endometrial tumors have the potential to spread to the para-aortic nodes both through stepwise progression from the pelvic nodes and from direct colonization via the tubo-ovarian ligament.9, 10 Relapse in the para-aortic nodes is relatively rare among all patients, accounting for 5–10% of recurrences. However, this rate is higher in patients with higher-grade tumors and nodal disease at presentation and lower in patients who undergo adjuvant para-aortic node irradiation.2, 11, 12 The incidence of isolated para-aortic relapse is also expected to increase with more frequent follow-up imaging after initial therapy.13–16 Currently, at our institution, patients with advanced endometrial cancer are evaluated every 3–6 months for 2–5 years. Imaging is reserved for symptoms for patients with low-grade early-stage carcinomas but is used with increasing frequency on a routine basis for patients with high risk disease (stage III endometrioid carcinomas and high-risk histologic subtypes); as a consequence, isolated nodal recurrences are often detected before distant metastases have developed. The fact that longterm survivors were observed in this series provides a potential justification for regular abdominal screening in high risk patients, but larger studies are required to test this hypothesis.

In our series, all of the patients who had late severe gastrointestinal toxic effects were prescribed GTV doses of more than 60 Gy and underwent aggressive multimodality therapy including partial nodal dissection, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy, concurrent chemotherapy, or a combination thereof (Table 3). In view of these findings, the potential advantages of intense multimodality treatment should be carefully weighed against the risk of serious late toxic effects.

Technical Recommendations

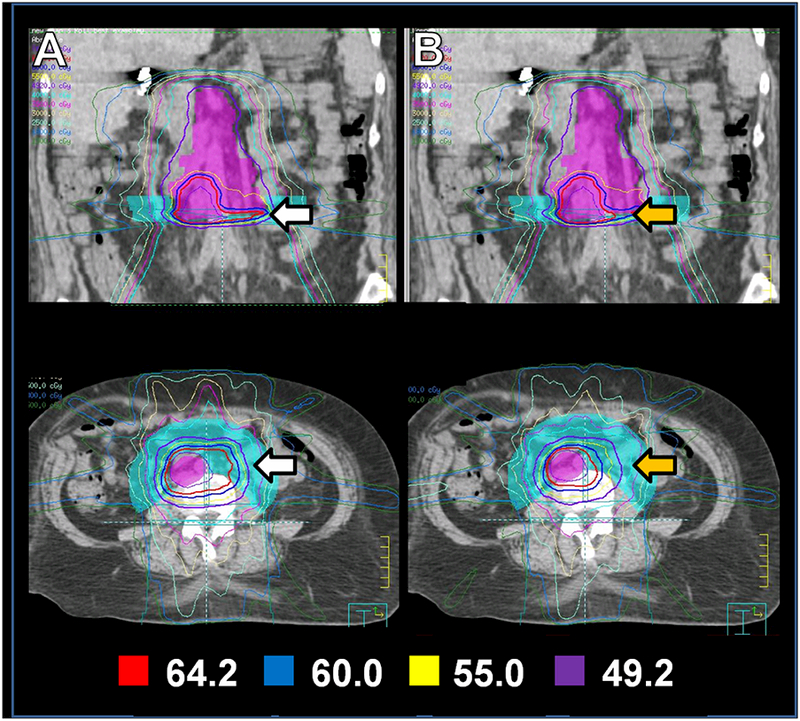

Planning of para-aortic IMRT should include very careful assessment of the dose and irradiated volume of critical structures, particularly duodenum and small bowel, and patients should be carefully monitored for gastrointestinal toxic effects during and after radiotherapy. To that end, an important technical dilemma arises during para-aortic IMRT treatment planning for patients who have previously undergone radiation to the whole pelvis. Namely, prior pelvic fields are typically delivered with the placement of the isocenter near the center of the pelvis, which results in superior divergence of these fields into the lower abdomen. If a need arises to deliver definitive IMRT to the para-aortic basin, a high region of excess cumulative dose in the small bowel is created where the new para-aortic fields overlap with the divergence of the prior pelvic fields (Figure 4A). This issue is compounded by the designation of kidneys as an avoidance structure in the upper abdomen, which tends to favor anterior and posterior weighting of the IMRT fields. In turn, this field geometry can escalate the total composite dose received by bowel in the lower abdomen.

Figure 4.

“Bowel-push” technique: The para-aortic basin and grossly involved node that constitute the PTV (lavender) are near the junction of the prior pelvic fields. Therefore, the new IMRT plan results in a large hot spot (white arrows) in the composite plan (column A). After designating the “bowel-push” structure (aqua) as an avoidance structure (column B), better conformality around the gross node is achieved (orange arrows) with concomitant reduction of normal tissue exposure in the bowel-push region. Exposure of bowel to low-dose radiation in the anterior abdomen is also reduced.

Because of the relatively high rate of severe gastrointestinal toxicity observed in our early experience, at our institution we have recently developed the following practice to avoid a bowel hotspot at the junction of prior pelvic fields and IMRT fields directed at the para-aortic nodes. A structure is created which encompasses the bowel adjacent to the para-aortic target volume at the level where divergence from the previous pelvic fields overlaps with the para-aortic IMRT target. This arc-shaped “bowel push” structure is then given a priority level during IMRT treatment planning that minimizes dose to the bowel at the region of overlap. We find that this technique reduces the volume of bowel receving a high dose (Figure 4B) without reducing coverage of the para-aortic nodes (Figure 5).

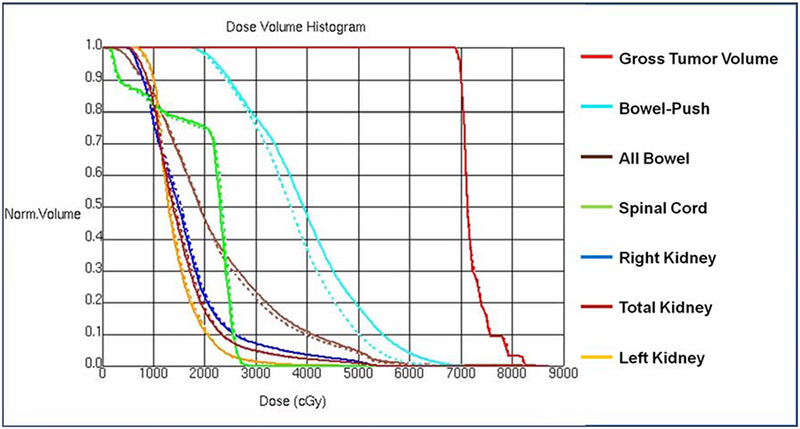

Figure 5.

DVH of plan in Figure 4, with (solid) and without (dashed) the bowel-push structure designated as an avoidance structure. There is diminishment of dose to the bowel inside the bowel-push region with minimal impact on dosimetry of the target and other organs-at-risk.

Clinical judgment regarding the maximum acceptable dose to the small bowel will need to take into account the the proximity of the recurrence to the previous field, the mobility of the bowel and the interval since the prior pelvic radiation. For most patients simulated in supine fashion, bowel will be present in the overlap region, which should favor use of this technique. Similarly, we consider intervals less than 2 years since prior radiation to place patients at particular risk for bowel toxicity.

Finally, we note that some leverage can be gained by manipulation of the isocenter of the initial pelvic fields or the later para-aortic IMRT plan. For instance, in patients for whom there is strong clinical suspicion that para-aortic IMRT may eventually be required, one can consider placing the 4-field pelvis isocenter at the superior border, thus avoiding superior divergence into the abdomen altogether.Likewise, in some patients who have already undergone pelvic radiation, placing the para-aortic IMRT isocenter at the inferior border of the field can be useful in minimizing inferior divergence of the IMRT fields into the pelvis. This can assist in limiting the overlap region to an area above the prior superior border of the pelvic fields.

Limitations

An important limitation to our study is that the number of patients was small, and the cases included a heterogeneous mix of stages, histologies, and multimodality treatments. This is a consequence of the effectiveness of initial therapy, and the fact that para-aortic recurrence is still a relatively rare event. Although it is apparent from our series that definitive treatment with IMRT can achieve long-term survival for some patients with para-aortic node recurrences, future observation of more patients and longer follow-up will be required to inform optimal therapy of para-aortic recurrences.

Conclusion

We recommend therapy with curative intent for patients with isolated paraaortic recurrences. At our institution, patients in whom complete resection is possible may undergo lymph node dissection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy with or without additional chemotherapy or alternatively may be treated with definitive chemoradiation alone. Patients in whom complete resection is not feasible are more often treated with definitive chemoradiation with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. For delivering definitive chemoradiation, IMRT can be used to achieve doses that result in successful local control. However, the risk of severe gastrointestinal toxic effects is high, and treatment planning should seek to minimize dose to the small bowel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant, CA016672.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST NOTIFICATION

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. Mar–Apr 2008;58(2):71–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klopp AH, Jhingran A, Ramondetta L, Lu K, Gershenson DM, Eifel PJ. Node-positive adenocarcinoma of the endometrium: outcome and patterns of recurrence with and without external beam irradiation. Gynecol Oncol. Oct 2009;115(1):6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Carmen MG, Boruta DM 2nd, Schorge JO. Recurrent endometrial cancer. Clin Obstet Gynecol. Jun 2011;54(2):266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odagiri T, Watari H, Hosaka M, et al. Multivariate survival analysis of the patients with recurrent endometrial cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. Mar 31 2011;22(1):3–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.RTOG Acute Radiation Morbidity Scoring Criteria: http://www.rtog.org/ResearchAssociates/AdverseEventReporting/AcuteRadiationMorbidityScoringCriteria.aspx. Accessed on June 1, 2011.

- 6.RTOG/EORTC Late Radiation Morbidity Scoring Schema. http://www.rtog.org/ResearchAssociates/AdverseEventReporting/RTOGEORTCLateRadiationMorbidityScoringSchema.aspx. Accessed on June 1, 2011.

- 7.Lin LL, Grigsby PW, Powell MA, Mutch DG. Definitive radiotherapy in the management of isolated vaginal recurrences of endometrial cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. Oct 1 2005;63(2):500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jhingran A, Burke TW, Eifel PJ. Definitive radiotherapy for patients with isolated vaginal recurrence of endometrial carcinoma after hysterectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. Aug 1 2003;56(5):1366–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Kurman RJ, et al. Relationship between surgical-pathological risk factors and outcome in clinical stage I and II carcinoma of the endometrium: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. Jan 1991;40(1):55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariani A, Dowdy SC, Cliby WA, et al. Prospective assessment of lymphatic dissemination in endometrial cancer: a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol. Apr 2008;109(1):11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abu-Rustum NR, Chi DS, Leitao M, et al. What is the incidence of isolated paraaortic nodal recurrence in grade 1 endometrial carcinoma? Gynecol Oncol. Oct 2008;111(1):46–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mundt AJ, Murphy KT, Rotmensch J, Waggoner SE, Yamada SD, Connell PP. Surgery and postoperative radiation therapy in FIGO Stage IIIC endometrial carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. Aug 1 2001;50(5):1154–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nout RA, Smit VT, Putter H, et al. Vaginal brachytherapy versus pelvic external beam radiotherapy for patients with endometrial cancer of high-intermediate risk (PORTEC-2): an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet. Mar 6;375(9717):816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randall ME, Filiaci VL, Muss H, et al. Randomized phase III trial of whole-abdominal irradiation versus doxorubicin and cisplatin chemotherapy in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. Jan 1 2006;24(1):36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greven K, Winter K, Underhill K, Fontenesci J, Cooper J, Burke T. Final analysis of RTOG 9708: adjuvant postoperative irradiation combined with cisplatin/paclitaxel chemotherapy following surgery for patients with high-risk endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. Oct 2006;103(1):155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roland PY, Kelly FJ, Kulwicki CY, Blitzer P, Curcio M, Orr JW Jr. The benefits of a gynecologic oncologist: a pattern of care study for endometrial cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol. Apr 2004;93(1):125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.