Abstract

A major barrier in the discovery of new secondary metabolites from microorganisms is the difficulty of distinguishing the minor fraction of productive cultures from the majority of unproductive cultures and growth conditions. In this study, a rapid, direct-infusion electrospray mass spectrometry (ES-MS) technique was used to identify chemical differences that occurred in the expression of secondary metabolites by 44 actinomycetes cultivated under six different fermentation conditions. Samples from actinomycete fermentations were prepared by solid-phase extraction, analyzed by ES-MS, and ranked according to a chemical productivity index based on the total number and relative intensity of ions present in each sample. The actinomycete cultures were tested for chemical productivity following treatments that included nutritional manipulations, autoregulator additions, and different agitation speeds and incubation temperatures. Evaluation of the ES-MS data from submerged and solid-state fermentations by paired t test analyses showed that solid-state growth significantly altered the chemical profiles of extracts from 75% of the actinomycetes evaluated. Parallel analysis of the same extracts by high-performance liquid chromatography–ES-MS–evaporative light scattering showed that the chemical differences detected by the ES-MS method were associated with growth condition-dependent changes in the yield of secondary metabolites. Our results indicate that the high-throughput ES-MS method is useful for identification of fermentation conditions that enhance expression of secondary metabolites from actinomycetes.

Many traits of microbes, both positive and negative, are attributed to expression of biologically active secondary metabolites. These metabolites are typically produced only under specific physiological conditions, and many are not essential for growth (6, 33). Although the physiological role of most secondary metabolites remains an area of speculation (25), these compounds have been ascribed apparent roles, including cell differentiation, cell signaling or communication, nutrient sequestering, and defense (6, 7, 12, 21, 26, 33).

The foremost value of secondary metabolites to humanity has been in providing the basis for new commercial drugs, both directly (e.g., penicillin) and indirectly (e.g., synthetic or semisynthetic compounds derived from secondary metabolites [8]). In recent years, several factors have increased the difficulty of discovering secondary metabolites with the potential to be drug leads. These factors include the difficulty of managing the compatibility of complex natural extracts with high-throughput and ultra-high-throughput screening methods, the reality that most discoveries are rediscoveries of known compounds, and competition from laboratory-synthesized chemical diversity, the supply of which has been dramatically increased by combinatorial methods (4, 14). However, human awareness of microbial biodiversity has expanded tremendously in the past few years, so we now recognize that less than a few percent of the biodiversity on earth have been evaluated in drug-screening programs (37). This awareness has renewed interest in evaluating microbes as a potential source of new secondary metabolites. The number of microbes and the biological diversity of microbes are so large that many strategies are being invoked to cope. Examples include cloning to express secondary metabolite pathways in surrogate hosts (36) and development of special methods to cultivate and elicit secondary metabolism in new microbial groups (34). While the traditional methods of cultivation and elicitation, as well as the newer strategies, are intended to give access to previously unknown secondary metabolites, all methods are limited by the large number of samples that must be evaluated before meaningful inferences can be made about the effectiveness of one treatment relative to another with regard to the ultimate objective, production of secondary metabolites.

Feedback on expression of secondary metabolites comes from two classes of analyses, biological and chemical (40). Because of the many vagaries of biological assays (e.g., nonlinear responses, chemical interference, lack of correlation between bioassay data, and domination of activity outcomes by a few common metabolites), we favor more general chemical analyses to provide data to guide improved expression of secondary metabolites. At present, the best chemical analyses depend on initial separation of natural product extracts (by thin-layer chromatography or high-performance liquid chromatography [HPLC]) followed by detection of the resolved secondary metabolites by suitable detectors (15, 23). However, the benefits of superior resolution resulting from chromatographic separation of natural product extracts are often offset by lower throughput because of the greater time, reagents, and labor necessary for chromatography. Ideally, basic comparisons of groups of cultures or expression conditions could be done at a lower cost and with higher throughput yet still account for differences in the concentrations and diversities of secondary metabolites present in extracts.

In the accompanying paper we describe a direct-infusion electrospray mass spectrometry (ES-MS) method that has the sensitivity and throughput required for analysis of large numbers of natural product extracts (20); we demonstrated the effectiveness of this method for ranking cultures grown under one set of common conditions. In this study we extended the application to the more difficult problem of comparing the effects of different growth conditions on expression of secondary metabolites by actinomycetes, and we corroborated conclusions resulting from the rapid method with the results of the best available HPLC method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and cultivation.

Cultures of 44 actinomycetes (Table 1) were started from cryogenic stocks in a vegetative medium that contained (per liter) 30 g of tryptic soy broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), 3 g of yeast extract (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), 2 g of MgSO4, 5 g of glucose, and 4 g of maltose. At the mid-log phase, 60 μl (∼0.4% inoculum) of each vegetative culture was transferred into 12 ml of complex growth medium A, which contained (per liter) 10 g of glucose, 40 g of potato dextrin (Avedex, Keokuk, Iowa), 15 g of cane molasses (Cargill, Minneapolis, Minn.), 10 g of Hy-case amino (Sheffield Products, Norwich, N.Y.), 1 g of MgSO4, and 2 g of CaCO3; the final pH was 7.0. Other complex fermentation media used for submerged fermentations included medium B, which contained (per liter) 5 g of soybean flour Nutrisoy (Archer Daniels Midland, Decatur, Ill.), 10 g of glucose, 10 g of glycerin, 5 g of soluble starch (Difco), 20 g of potato dextrin, 0.1 g of FeCl2 · 4H2O, 0.1 g of ZnCl2, 0.1 g of MnCl2 · 4H2O, 0.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 5 g of corn steep powder (Sigma), 3 g of CaCO3, 1 g of phytic acid (Sigma), and 10 g of cane molasses (final pH, 7.0); medium C, which contained (per liter) 15 g of hexaglycerol dioleate, 5 g of corn steep powder, 3 g of CaCO3, 5 g of glucose, 50 g of lactose, 10 g of soybean flour Nutrisoy, 5 g of peptone, 2 g of NH4SO4, 0.1 g of FeCl2 · 4H2O, 0.1 g of ZnCl2, 0.1 g of MnCl2 · 4H2O, and 0.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O (final pH, 7.0); and medium D, which contained (per liter) 10 g of glucose, 40 g of potato dextrin (Avedex), 15 g of cane molasses (Cargill), 10 g of Hy-case amino (Sheffield Products), 1 g of MgSO4, 2 g of CaCO3, and 3 g of Na2HPO4 (final pH, 7.0).

TABLE 1.

Detection of solid-state-dependent changes in the chemical compositions of extracts from 44 actinomycetes grown in submerged and solid-state fermentations by using medium A

| Strain | Solid-state response

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Response categorya | Response magnitudeb | |

| Streptomyces griseus ATCC 10137 | E | 1,220 |

| Nocardia mediterranei ATCC 13685 | E | 1,168 |

| Streptomyces aureofaciens ATCC 31445 | E | 973 |

| Nocardia lurida ATCC 14930 | E | 897 |

| Streptomyces endus ATCC 23904 | E | 871 |

| Micromonospora megalomicea ATCC 27597 | E | 847 |

| Streptomyces cinnamonensis ATCC 15413 | E | 735 |

| Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC 14585 | E | 698 |

| Streptomyces griseolus ATCC 19764 | E | 652 |

| Streptomyces sioyaensis ATCC 13989 | E | 646 |

| Saccharopolyspora erythraea ATCC 11635 | E | 633 |

| Nocardia orientalis ATCC 19795 | E | 621 |

| Streptomyces spheroides ATCC 23965 | E | 615 |

| Streptomyces albus ATCC 21132 | E | 568 |

| Saccharopolyspora spinosa ATCC 49460 | E | 516 |

| Streptomyces rutgersensis ATCC 14876 | E | 491 |

| Streptomyces candidus ATCC 19891 | E | 489 |

| Streptomyces roseosporus ATCC 31568 | E | 480 |

| Streptomyces aureofaciens ATCC 10762 | N | 432 |

| Streptomyces spadicus ATCC 19017 | N | 419 |

| Actinoplanes missouriensis ATCC 31682 | N | 394 |

| Kibdelosporangium aridum ATCC 39323 | N | 312 |

| Streptomyces spectabilis ATCC 27465 | N | 297 |

| Streptomyces clavuligerus ATCC 27064 | N | 280 |

| Streptomyces galilaeus ATCC 31133 | N | 257 |

| Streptomyces filipinensis ATCC 23905 | N | 255 |

| Micromonospora echinospora ATCC 15838 | N | 216 |

| Streptomyces rimosus ATCC 23955 | N | 207 |

| Streptoalloteichus hindustanus ATCC 31217 | N | 205 |

| Streptomyces venezuelae ATCC 10595 | S | 175 |

| Streptomyces tanashiensis ATCC 31053 | S | 113 |

| Streptomyces capreolus ATCC 23892 | S | 90 |

| Streptomyces chartreusis ATCC 23336 | S | 66 |

| Micromonospora rosaria ATCC 29337 | S | 50 |

| Nocardia lurida ATCC 14930 | S | 24 |

| Micromonospora carbonacea ATCC 27114 | S | 24 |

| Actinoplanes teichomyceticus ATCC 31121 | S | 8 |

| Streptomyces bikiniensis ATCC 11062 | S | −98 |

| Streptomyces nodosus ATCC 14899 | S | −130 |

| Streptomyces antibioticus ATCC 8663 | S | −141 |

| Streptomyces avermitilis ATCC 31267 | S | −142 |

| Streptomyces kanamyceticus ATCC 12853 | S | −235 |

| Streptomyces tenebrarius ATCC 17920 | S | −398 |

| Streptomyces fradiae ATCC 19609 | S | −1,515 |

The fermentation vessel consisted of a rectangular Axid (Eli Lilly and Co., Indianapolis, Ind.) polypropylene bottle that was approximately 3.5 cm long by 4.25 cm wide by 6 cm high. The closure for each small shake flask fermentation bottle consisted of a γ-irradiated, vented polypropylene cap lined with a gas-permeable membrane (Performance Systematix, Inc., Caledonia, Mich.). Submerged fermentations were incubated at 30°C for 7 days on an orbital shaker (stroke length, 2 in.) at 110 rpm. For solid-state fermentations, Noble agar (Difco) was added to fermentation medium A to a final concentration of 1.5%. Solid-state fermentations were incubated under growth conditions that were identical to those used for submerged fermentations, except that solid-state fermentations were incubated without shaking. The majority of growth was restricted to the surface of the agar, except for the substrate mycelia, which penetrated approximately 1.5 mm into the agar for most cultures. Contamination was assessed for all fermentations at the end of the incubation period by removing approximately 20 μl of broth and spreading it on tryptic soy agar (Difco). Culture purity was assessed after 2 days of incubation at 30°C, and contaminated fermentations (containing more than one microorganism) were discarded. The rate of contamination for fermentations completed in this study was less than 0.8%.

Liquid fermentations were prepared for chemical analysis by addition of an equal volume of absolute ethanol to the original fermentation vessel. Solid-state fermentations were prepared for chemical analysis by two methods. In the initial experiments the fermentations were prepared so that they were analogous to the liquid fermentations described below. Later, we modified the cultivation method by introducing a nylon membrane between the agar and the colony to allow separation for quantitation (see below). For the initial solid-state fermentations, grown directly on agar, samples were prepared by solublization of secondary metabolites by the protocol described below for submerged fermentations, except that a lower ratio of ethanol to water (42:58, vol/vol) was used. The lower ratio of ethanol to water was based on gas chromatographic analyses of the ethanol concentration during the 16-h extraction process for five independent solid-state fermentations of Saccharopolyspora erythraea. The results showed that 8 to 10% of the water present in the extraction solution was lost during extraction of solid-state fermentations. This loss of water was compensated for by using an extraction solution with a lower ratio of ethanol to water (42:58, vol/vol). Analyses of ethanol were performed by injecting 1 μl of an extract into a Hewlett-Packard model 5890 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector and a DB wax column (15 m by 0.53 mm; J. W. Scientific, Folsom, Calif.). The gas chromatography program parameters were as follows: isocratic run time, 3.5 min; oven temperature, 80°C; and injector and detector temperature, 230°C. For both submerged and solid-state fermentations, vessels containing ethanol were agitated for 2 h on an orbital shaker (stroke length, 2 in.) at 200 rpm, and then the contents were allowed to settle for 16 h at 4°C. The aqueous ethanol extracts were then filtered through a 100-μm-pore-size nylon screen and transferred to 96-well plates for chemical analysis. Dry cell weights of submerged fermentations were determined by using the water-washed particulate (10,000 × g, 15 min) fractions from 6-ml samples of the fermentation broths. The particulate materials were transferred to preweighed aluminum weighing dishes and dried under a vacuum (−80 kPa) at 70°C for 16 h.

A-factor (2-isocapryloyl-3R-hydroxymethyl-γ-butyrolactone) was isolated from Streptomyces griseus ATCC 10137 by extraction of biomass with ethyl acetate, followed by reverse-phase chromatography of the lyophilized extract as previously described (3, 17). Purified A-factor was solublized in ethanol, filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter, and added to sterile fermentation vessels to a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. This concentration was based on studies of A-factor production in S. griseus IFO13350, which showed that the concentration of A-factor reached a maximum value (25 ng/ml) during log-phase growth (3). The ethanol was removed before addition of medium A by evaporation of the solvent under a vacuum (−80 kPa, 25°C) for 1 h.

SPE of actinomycete extracts.

Polar materials were removed from 0.7-ml samples of actinomycete extracts by solid-phase extraction (SPE) on Empore octadecyl SD high-performance 96-well extraction disk plates (3M Company, St. Paul, Minn.). The SPE stationary phase was conditioned before use by sequential washing with 2 ml of distilled H2O, with 2 ml of methanol, and finally with 2 ml of 1 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5) in distilled H2O. The ethanol was removed from a 0.7-ml sample of actinomycete extract under a vacuum (−80 kPa) at 20°C for 16 h. The residual aqueous material was resuspended to a total volume of 0.5 ml with 1 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5) and loaded on the conditioned SPE stationary phase. The SPE stationary phase was washed with 5 ml of 1 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5), and then the secondary metabolite-containing fraction was eluted with 0.7 ml of a solution consisting of 70% (vol/vol) acetonitrile, 30% (vol/vol) methanol, and 6.5 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.5). The eluate, enriched in secondary metabolites, was transferred into microwell plates and analyzed by ES-MS and by HPLC–ES-MS.

Quantification of secondary metabolites from solid-state fermentations.

Although the initial solid-state fermentation analyses were performed by extraction of mycelia grown directly on agar (see above), we extracted mycelia grown on nylon membranes for quantification of cell mass and secondary metabolites. The actinomycetes were grown on 0.64-cm-diameter, matched-weight (24.0 ± 0.2 mg) filter disks that were placed on the agar surface of the solid-state fermentation medium. Biomass and secondary metabolite contents were determined directly by using the growth present on disks that were placed on 2 ml of fermentation medium containing 1.5% Noble agar (Difco). Fermentations were completed in 24-well tissue culture plates (Falcon no. 3047; Becton Dickinson Co., Lincoln Park, N.J.) by transferring 10 μl of a vegetative culture to the center of a disk. Initially, the following four types of disks were evaluated: Millipore Immobilon N+ (pore size, 45 μm; catalog no. 202-00), Schleicher & Schuell Nytran (pore size, 0.2 μm; catalog no. 78179), Gelman Sciences Biotrace polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) (pore size, 0.45 μm; catalog no. 66542), and Gelman Sciences Biotrace nitrocellulose (pore size, 0.45 μm; catalog no. 66489). The Schleicher & Schuell filters were ultimately selected for use (see below). Dry cell weight and chemical analyses were completed in parallel, and three disks were used for each analysis. For dry cell weight determinations, disks were removed from the surface of the medium, placed in preweighed aluminum weighing dishes, and dried under a vacuum (−80 kPa) at 70°C for 16 h. The mean weight obtained from four uninoculated filter disks was subtracted from individual dry weight values to determine the dry weights of the samples. For chemical analyses, disks were removed from the agar surface and each disk was placed in a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 1 ml of an aqueous 50% (vol/vol) ethanol solution. Each filter disk was vortexed vigorously for 1 min and then stored for 24 h at 4°C. Following storage, the extract was vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was analyzed by ES-MS or HPLC–ES-MS.

The efficiency of recovery of the secondary metabolites present on membranes was estimated by applying aqueous solutions of purified tylosin (reference standard grade; lot RS0193; Eli Lilly and Co.) to Streptomyces spadicus biomass present on a membrane surface to a final quantity of 50 or 100 μg/disk. The stock solutions used for adding 50 and 100 μg of tylosin consisted of tylosin dissolved in aqueous solutions of 50% (vol/vol) ethanol at concentrations of 2.5 and 5 mg/ml, respectively. The disks were allowed to air dry and then were dried under a vacuum (−80 kPa) at 25°C for 1 h. The dried disks were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes and extracted as described above.

Chemical and statistical analyses.

Chemical analyses of filtered ethanol extracts or of SPE eluates were performed by HPLC–ES-MS as described by Julian et al. (23) or by ES-MS as described by Higgs et al. (20). A standard mixture consisting of caffeine, m-cresol purple, Spinosad (a mixture of isomeric spinosyn factors A and D; Dow Agrosciences, Indianapolis, Ind.), narasin A, and tylosin (100 μg/ml each) was injected at the beginning, at the end, and after every 10th sample to assess instrument stability and performance during the analyses. Data from the ES-MS studies were evaluated with a UNIX workstation by using the productivity index algorithms described by Higgs and coworkers (20). Background corrections were completed for all treatments by subtracting the chemical productivity score for the uninoculated treatment (20). Data for ES-MS experiments are reported below in chemical productivity units (cp units) per milligram (dry weight of cells, and 1 cp unit was defined as 1/6,171th of the ES-MS signal response obtained with the standard mixture consisting of caffeine, m-cresol purple, Spinosad, narasin A, and tylosin, each at a concentration of 100 μg/ml.

Statistical evaluation of data and the experimental design was performed with JMP statistical discovery software (version 3; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, N.C.).

RESULTS

Reproducibility of ES-MS measurements and fermentation output.

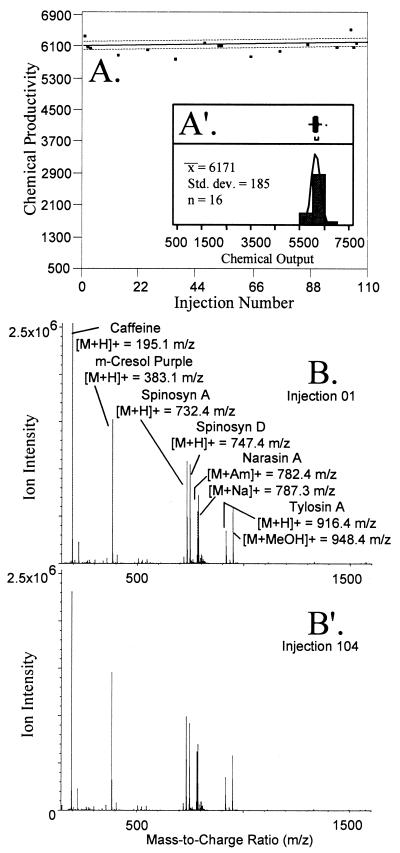

In the accompanying paper we describe a high-throughput ES-MS method to quantify compounds present in natural product extracts (20). In this method, the mass-to-charge ratios and the intensities of ions present in ES-MS spectra are used to measure the chemical productivity of natural product extracts. The reproducibility of these ES-MS-based measurements is influenced by changes in instrument sensitivity or performance, the efficiency of sample preparation procedures, and growth parameters, such as temperature, incubation time, and plating methods. Instrument reproducibility was assessed throughout the experiment by injecting the standard mixture first, last, and after every 10th experimental sample. Chemical productivity measurements for 16 control injections of the standard mixture that were interspersed among 88 experimental samples (total number of samples, 104) revealed a mean of 6,171 cp units, a standard deviation of 185 cp units (Fig. 1), and a coefficient of variance of 5.8%. The coefficients of variance for all bracketing control injections evaluated in this study (n = 56) were less than or equal to 7.1%. Lower concentrations of the standard mixture yielded mean chemical productivity values that were linearly related to the known concentrations between 5 and 100 μg/ml. The standard deviations for lower concentrations of the standard mixture were also observed to decrease in a nearly linear fashion between concentrations of 5 and 100 μg/ml.

FIG. 1.

Reproducibility of analysis of standards that were interspersed among experimental measurements. (A and A′) Sequential chemical productivity values due to variations in instrument performance during sample analysis (A) and their distribution (A′). (B and B′) Assignment of ions in the ES-MS standard mixture for the first (injection 01) (B) and last injection (injection 104) (B′) of the experiment.

The overall experimental variability due to the combination of ES-MS instrument performance, sample preparation procedures, and reproducibility of growth was estimated by using eight independent fermentations of S. erythraea that were cultivated under submerged and solid-state conditions. Measurements for the eight SPE eluates from solid-state fermentations of S. erythraea obtained by ES-MS methods resulted in a mean of 3,410 cp units and a standard deviation of 139 cp units, while measurements for the eight SPE eluates from submerged fermentations resulted in a mean of 1,152 cp units and a standard deviation of 121 cp units. The difference between the sampling means (2,258 cp units) for solid-state and submerged fermentations was approximately 12-fold higher than the difference associated with sources of variability and, therefore, was attributed to the treatment effects of solid-state growth. The overall variability was found to be similar to the variability associated solely with instrument performance (130 versus 185 cp units). These results show that the variability associated with cultivation or sample preparation procedures can be minimized by adherence to standard cultivation and sample preparation procedures, at least for some microorganisms.

Measurement of growth condition-dependent changes in secondary metabolites from 44 actinomycetes.

Growth condition-dependent changes in the chemical compositions of extracts were evaluated for 44 actinomycetes cultivated under six different fermentation conditions by using the paired t test. The mean differences and standard errors for paired t test comparisons between the treatments shown in Table 2 were used to quantify treatment effects. A comparison of extracts from two independent fermentations of the 44 actinomycetes, completed in control medium A, revealed a low mean difference and standard error (Table 2). Similar results (mean difference values, ≤10%) were observed for fermentation extracts from the 44 actinomycetes cultivated for different growth periods (5, 7, and 12 days), at different incubation temperatures (25 and 30°C), and at different agitation speeds (110 and 165 rpm) by using medium A (data not shown). The low mean difference values and low standard errors for these comparisons indicated that growth conditions did not differ significantly in the capacity to stimulate secondary metabolism. The sum of the mean differences for paired t tests between treatments was used to identify fermentation conditions that most effectively stimulated secondary metabolism in actinomycetes (Table 2). The results of this analysis demonstrated that solid-state fermentation in medium A and submerged fermentation in medium B provided extracts with the greatest chemical productivity, while all other fermentation conditions provided lower levels of chemical productivity.

TABLE 2.

Distance matrix for paired t test analyses of chemical productivity scores for 44 actinomycetes grown under six different fermentation conditions

| Fermentation growth medium or conditions | Chemical productivity (cp units · mg [dry wt] of cells−1) in:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium A (control) | Medium A (replicate) | Medium B | Medium C | Medium D | Medium A + solid state | Medium A + A-factor | |

| Medium A (control) | 1 | 39 ± 33 | 367 ± 94 | 56 ± 53 | 208 ± 129 | 336 ± 70 | 43 ± 39 |

| Medium A (replicate) | 1 | 361 ± 101 | 69 ± 52 | 225 ± 119 | 324 ± 70 | 51 ± 42 | |

| Medium B | 1 | 223 ± 113 | 258 ± 88 | 581 ± 145 | 332 ± 85 | ||

| Medium C | 1 | 265 ± 130 | 395 ± 99 | 79 ± 61 | |||

| Medium D | 1 | 359 ± 147 | 151 ± 128 | ||||

| Medium A + solid state | 1 | 419 ± 66 | |||||

| Medium A + A-factor | 1 | ||||||

| Summed distance matrix scorea | 1,049 | 1,069 | 1,758b | 1,025b | 1,984b | 1,028b | |

The summed distance matrix score represents the total of distance matrix values for individual treatments.

An average of the medium A and medium A replicate values was used to calculate the summed mean difference for treatments.

Development of a filter growth method to facilitate measurement of yields of secondary metabolites from solid-state fermentations.

The paired t test analysis showed that the solid-state growth conditions provided extracts with the greatest chemical productivity values compared to the values obtained with other fermentation conditions. However, our initial attempts to measure dry cell weight to calculate specific productivity values were hindered by an inability to obtain reproducible biomass samples due to the attachment of substrate mycelia to the agar surface. Therefore, a method for growing organisms on the surface of a filter disk was developed in order to prevent substrate mycelium attachment to the agar surface. Four different filter supports, including two nylon membranes with different pore sizes (0.2 and 0.45 μm), one PVDF membrane, and one nitrocellulose membrane, were tested to evaluate the effect of immobilized growth on the yield of erythromycin from S. erythraea. Similar yields of erythromycin (20.8 ± 4.2 μg of erythromycin/mg [dry weight] of cells) were obtained with nitrocellulose and nylon membranes, while no growth was observed on the PVDF membranes. The nylon membrane with the 0.2-μm pores (Nytran) was chosen for all subsequent solid-state yield determinations since it exhibited greater mechanical strength than the 0.45-μm-pore-size nylon or nitrocellulose membranes and was resistant to changes in shape caused by heat or pressure during sterilization.

The effect of the Nytran nylon membrane on expression of secondary metabolites was assessed by comparing the yields of erythromycin from S. erythraea grown directly on solid-state medium A and grown on nylon membranes supported by solid-state medium A. No apparent differences in the area of growth or the morphology of S. erythraea were observed between solid-state fermentations grown directly on the agar and solid-state fermentations grown on the agar-supported nylon membrane. Furthermore, no qualitative chemical differences in the HPLC–ES-MS profiles of ethanol extracts were observed between S. erythraea grown on the membrane surface and S. erythraea grown directly on the agar surface. Equivalent erythromycin yields based on surface area of growth were obtained when S. erythraea was grown directly on the agar and when it was grown on the membrane (324 ± 43 and 311 ± 34 μg of erythromycin · cm−2, respectively). These results indicated that the membrane surface did not significantly influence secondary metabolism in S. erythraea.

An experiment utilizing the ES-MS methods was performed with the group of 44 actinomyetes to confirm that secondary metabolism was not influenced by growth on the nylon membrane surface. The mean difference and standard error (37 ± 31 cp units · mg [dry weight] of cells−1) for the paired t test analysis of ES-MS data for actinomycetes grown on solid-state medium A or the nylon membrane supported by solid-state medium A were found to be similar to the mean difference and standard error for repeat fermentations of the 44 actinomycetes completed in medium A (39 ± 33 cp units · mg [dry weight] of cells−1) (Table 2). These results provide additional evidence that secondary metabolism in actinomycetes grown under solid-state conditions is not influenced by growth on a membrane surface.

The recovery efficiency for the secondary metabolite extraction process was measured by applying purified tylosin (internal standard) to S. spadicus biomass present on nylon membranes. Analyses, performed in triplicate by adding 50 and 100 μg of solublized tylosin to S. spadicus biomass present on nylon membranes, resulted in levels of recovery of tylosin of 93% ± 2.4% and 96% ± 1.9%, respectively. These results were similar to the recovery efficiencies obtained for submerged fermentations and provided justification for comparison of solid-state and submerged growth conditions.

Characterization of treatment effects associated with solid-state growth.

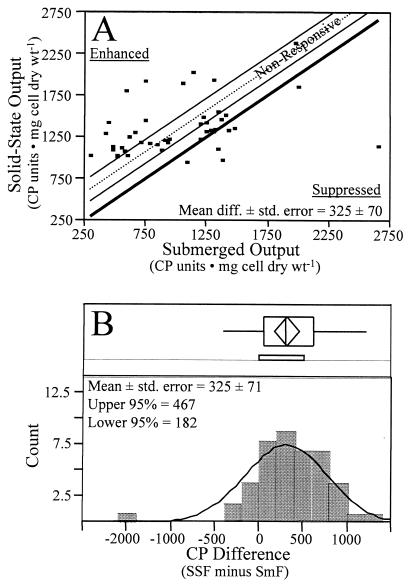

Actinomycetes cultivated under solid-state conditions provided the greatest level of chemical productivity when these conditions were compared to the other growth conditions evaluated in this study. A paired t test of the results for extracts from the 44 actinomycetes cultivated in medium A under submerged or solid-state conditions showed that significant differences in expression of metabolites occurred in response to growth conditions (Fig. 2A). Differences in expression of metabolites for the two growth conditions were also quantified by analyzing the distribution of the differences between productivity values (solid state minus submerged) for individual cultures. The 95% confidence intervals for this distribution (182 ≤ x ≤ 467 cp units · mg [dry weight] of cells−1) were used to place treatment responses associated with the ES-MS measurements into subsets. Treatment effects were assigned to three expression categories (solid state enhanced, nonresponsive, and solid state suppressed) based on the position of data points in relation to the 95% confidence intervals. The assignments to these categories are shown in Table 1. Approximately 41% (18 of 44) of the actinomycetes tested showed enhanced chemical productivity when they were grown under solid-state conditions, while a slightly lower number (34%, 15 of 44 actinomycetes) showed reduced chemical productivity when they were grown under solid-state conditions. The treatment effects due to solid-state growth did not significantly influence chemical productivity measurements for 25% (11 of 44) of the actinomycetes evaluated.

FIG. 2.

(A) Paired t test for normalized chemical productivity (CP) values from 44 actinomyctes grown under solid-state and submerged growth conditions. Treatment-induced displacement of the mean difference is indicated by the dashed line, and associated 95% confidence intervals (solid lines) from the predicted mean value (boldface line) are also indicated. (B) Distribution for the difference between solid-state (SSF) and submerged (SmF) chemical productivity values for 44 actinomycetes.

Correlation of growth condition-dependent changes detected by ES-MS with changes in the yields of known secondary metabolites from actinomycetes.

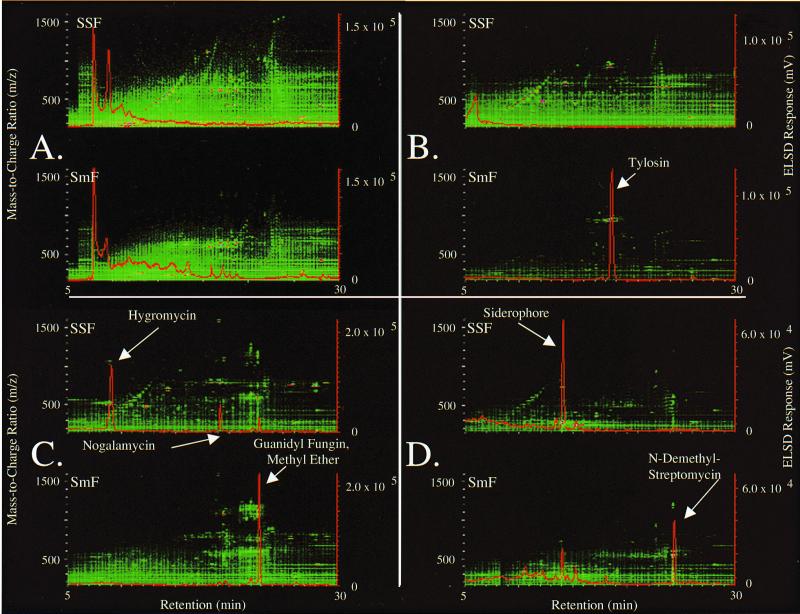

The 44 actinomycetes evaluated in this study were chosen, in part, due to their established production of a number of known, chemically diverse secondary metabolites. Secondary metabolites present in extracts were separated by reverse-phase chromatography, and the properties of compounds resolved were compared to the properties of authentic standards of known secondary metabolites based on UV-visible light absorption, chromatographic retention, and positive- and negative-ion ES-MS spectra in order to establish the identities of the compounds. The secondary metabolite concentrations for compounds listed in Table 3 were determined by comparison of the areas under the curve in HPLC evaporative light scattering chromatograms to the areas under the curve for authentic standards. Concentrations were converted to yields by using cell dry weight measurements for actinomycetes grown under solid-state and submerged conditions (Table 3). Solid-state fermentation was found to influence the yields of all of the secondary metabolites listed in Table 3 except erythromycin. The yield of erythromycin remained unchanged when the fermentation conditions were switched from submerged to solid state. The higher concentration of erythromycin in submerged fermentations was offset by the twofold increase in biomass that occurred under submerged fermentation conditions (Table 3; Fig. 3). Solid-state growth was found to enhance the yield of secondary metabolites for three of the six actinomycetes shown in Table 3. The greatest change in the yield of secondary metabolites for cultures grown under solid-state conditions occurred with hygromycin, whose yield increased more than 4,000-fold compared to the yield achieved under submerged growth conditions. Similar improvements in the yields of nogalamycin, the iron-binding siderophore, and rimocidin were observed under solid-state conditions (Table 3). In addition to the improvements in yield for some secondary metabolites, solid-state growth was observed to significantly reduce the yields of several secondary metabolites, including tylosin, calcimycin, guanidyl fungin methyl ether, and N-demethyl streptomycin (Table 3; Fig. 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the concentrations and yields of secondary metabolites from actinomycetes grown under solid-state and submerged growth conditions

| Organism | Solid-state response category | Secondary metabolite properties

|

Secondary metabolite conc (μg · fermentation−1)a

|

Specific secondary metabolite yield (μg · mg of cells−1)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | Mass (Da) | Retention time (min) | Solid-state conditions | Submerged conditions | Solid-state conditions | Submerged conditions | ||

| Saccharopolyspora erythraea | Nonresponsive | Erythromycin A | 733.9 | 17.7 | 112 ± 16 | 244 ± 25 | 21.1 ± 3.0 | 18.8 ± 2.0 |

| Streptomyces fradiae | Suppressed | Tylosin A | 916.1 | 18.3 | <0.1 | 149 ± 14 | <0.02 | 11.5 ± 1.1 |

| Tylosin D | 918.1 | 18.3 | <0.1 | 122 ± 11 | <0.02 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | ||

| Streptomyces chartreusis | Suppressed | Calcimycin | 523.6 | 25.0 | <0.1 | 31 ± 2 | <0.015 | 2.6 ± 0.2 |

| Streptomyces spadicus | Nonresponsive | Hygromycin A | 511.5 | 8.8 | 179 ± 36 | <0.1 | 28.9 ± 5.9 | <0.007 |

| Nogalamycin | 787.8 | 18.4 | 60 ± 24 | 5 ± 0.3 | 9.7 ± 3.9 | 0.3 ± 0 | ||

| Guanidyl fungin methyl ether | 1,144.5 | 23.1 | 23 ± 7 | 395 ± 56 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 34.3 ± 3.7 | ||

| Streptomyces griseus | Enhanced | N-Demethyl-streptomycin | 567.5 | 24.6 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 89 ± 3 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 6.9 ± 0.2 |

| Iron siderophore | 281.2 | 13.7 | 94 ± 12 | 40 ± 14 | 23.5 ± 3.0 | 3.1 ± 1.1 | ||

| Streptomyces rimosus | Nonresponsive | Rimocidin | 767.9 | 19.8 | 52 ± 3 | 77 ± 5 | 10.6 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.4 |

Total secondary metabolite output for solid-state fermentations was based on the amount of secondary metabolites extracted from disks in 1-ml extraction volumes, while total secondary metabolite output for submerged fermentations was based on the amount of secondary metabolites present in 1 ml of the fermentation preparation. Data are averages ± ranges based on triplicate fermentations.

FIG. 3.

Effects of solid-state (SSF) and submerged (SmF) growth on the concentrations of secondary metabolites present in extracts: HPLC separation of SPE eluates from Streptomyces aureofaciens (nonresponsive) (A), Streptomyces fradiae (suppressed) (B), S. spadicus (nonresponsive) (C), and S. griseus (enhanced) (D), showing ion contour maps and the evaporative light scattering chromatograms (red). The signal intensities for ions present in the ion contour map ranged from low (green) to high (white).

The yields of specific metabolites produced under solid-state and submerged growth conditions appeared to be a predictive indicator of the expression response category assigned by ES-MS methods for cultures described in Table 3. This result was anticipated, since both the ES-MS and HPLC evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD) methods respond quantitatively to analytes present in fermentation samples and since both data sets were normalized to biomass concentration. A positive correlation was observed between the yields of specific metabolites produced by cultures shown in Table 3 and the expression response categories assigned by ES-MS methods. For example, two cultures categorized as nonresponsive by ES-MS methods, S. erythraea and Streptomyces rimosus, showed relatively small differences (11 to 35%) in the yields of secondary metabolites for submerged and solid-state fermentations. Cultures categorized as either solid state enhanced or solid state suppressed exhibited more noticeable differences (from 98.9% for N-demethyl streptomycin to 99.9% for tylosin) in the yields of secondary metabolites for the two growth conditions. Two cultures, S. spadicus and S. griseus, exhibited complex changes in the expression profiles in response to growth conditions (Table 3). These complex changes involved opposite trends in the yields of two or more secondary metabolites found in the extracts when growth conditions were changed from submerged to solid state. A comparison of the total yield of secondary metabolites and the assigned ES-MS response category for each of the latter cultures showed that the basis of the ES-MS assignment was essentially the same as that for cultures exhibiting simple secondary metabolite profiles. The total yield of secondary metabolites produced by S. griseus, identified as a solid-state-enhanced culture, increased 58% after the culture was switched from submerged to solid-state growth conditions. For S. spadicus, a culture categorized as nonresponsive to growth conditions, the yields of secondary metabolites produced under solid-state and submerged growth conditions were quantitatively similar (18% difference). Close examination of the secondary metabolite profiles produced by S. spadicus under solid-state and submerged growth conditions showed that the ES-MS-assigned response category did not reflect the major qualitative changes that occurred in the secondary metabolite profile in response to growth conditions (Table 3).

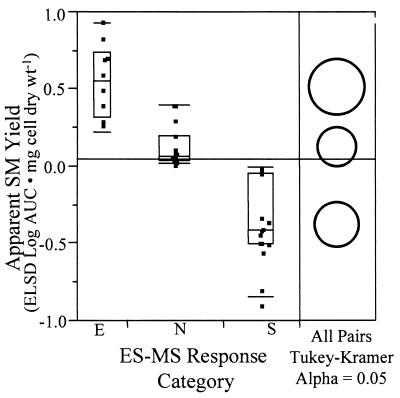

An alternative to evaluation of treatment effects on individual, known secondary metabolites would be to evaluate treatment effects on all apparent secondary metabolites. The ELSD response is based on scattering of light by molecules that are less volatile than the mobile phase and is regarded as a generic molecule detector (11, 16). Therefore, the summarized area under the curve for ELSD chromatograms was chosen as a surrogate for total secondary metabolite concentration to characterize differences between response categories identified by ES-MS methods. The total areas under the curve for ELSD chromatograms were first normalized by using cell dry weight values to determine apparent yields, and then the difference between solid-state and submerged conditions was calculated for each culture (solid state minus submerged). The resulting differences in apparent ELSD yields were then compared for the three groups (enhanced, suppressed, and nonresponsive) that were identified based on 95% confidence intervals for the distribution of ES-MS data (see above) (Table 1). An analysis of variance was performed with the ES-MS category (enhanced, suppressed, or nonresponsive) as a predictor and the difference between the ELSD-based apparent yields for the solid-state fermentations and the submerged fermentations as the response. The overall F test for the analysis of variance indicated that the mean responses of the three ES-MS-derived categories were not all equal (P < 0.0001). A qualitative examination of the ELSD-based response versus the ES-MS category showed that cultures classified as either enhanced or suppressed by ES-MS showed large differences in their ELSD-based responses, while cultures classified as nonresponsive showed small differences (Fig. 4). To identify ES-MS-derived categories with statistically significant differences in the ELSD-based response, a Tukey-Kramer test was performed to compare the mean responses for all pairwise combinations of ES-MS categories (29). The Tukey-Kramer test was chosen because of its conservative nature when the sample sizes for the effect categories are unequal, as they were in this case. The results of the Tukey-Kramer test were graphically depicted by nonoverlapping circles indicating that all three ES-MS categories were different at an alpha level of 0.05 (P < 0.0001). This analysis independently corroborated the finding that the rapid ES-MS method is sensitive to chemical changes in the composition of actinomycete extracts that occur in response to growth conditions.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of variance for the differences in apparent yields of secondary metabolites (SM) between solid-state and submerged growth conditions (solid-state minus submerged areas under the curve [AUC]) for the three ES-MS response categories defined in Table 1 and Fig. 2. The Tukey-Kramer mean comparison circle plot (inset) shows the differences (P < 0.0001) between the means of metabolite yields for the three ES-MS response categories (alpha level = 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The inability to recognize and directly measure general chemical productivity in natural product extracts by high-throughput, chemically based approaches has been a barrier to progress in discovery of new secondary metabolites for pharmaceutical and commercial applications. Historically, the secondary metabolite discovery process has been guided by activity-based screening approaches that identify active extracts based on their ability to affect a specific biological assay (4, 40). Activity-based screening often results in enrichment of compounds that are already known and is subject to high false-positive rates due to the complex nature of natural product extracts (27). One approach that has been employed to improve the quality of biological screening efforts has been to prescreen natural product extracts by chemical methods in an attempt to ensure a high level of chemical diversity in screening libraries. This general approach, referred to as physicochemical screening (41), is based on coupled separation and detection of secondary metabolites present in natural product extracts by various methods, including thin-layer chromatography–UV-visible light absorbance (15), HPLC–UV-visible light absorbance, HPLC–ES-MS (23), and HPLC-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1, 30). In addition to its application in prioritization of natural product extracts entering biological screening analyses, chemical screening has been used as the basis for selection of cultures and growth conditions that support expression of secondary metabolites. Monaghan and coworkers (28) used HPLC coupled with UV-visible light absorbance detection to show that rare fungal metabolites are more often associated with cultures that show high levels of chemical productivity. Culture productivity was assessed by the numbers and intensities of chromatographic peaks present in chromatograms. This study showed that chemical productivity criteria could be used to select new sources of natural products or as a means to improve secondary metabolite expression for existing natural product sources.

While chemical screening approaches have shown considerable promise as ways to expedite discoveries in natural product research, they have not gained widespread use due to limitations associated with low sample throughput and the challenges associated with acquiring meaningful information from many chromatograms. In this report we describe a rapid ES-MS method for measuring chemical productivity of actinomycete extracts and application of the method to evaluate growth conditions and other treatments that influence secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. This compound-centered profiling method differs from prior screening approaches used in natural product discovery in that it provides direct information on the composition of a natural product extract based on the number and intensity of ions present in the sample without the cost of chromatographic separation. This general measure of chemical productivity was shown to positively correlate with the yields of specific secondary metabolites or the total apparent yield of metabolites present in extracts from submerged and solid-state fermentations. The results of this study show that ES-MS is a useful surrogate for HPLC methods for identifying cultures and growth conditions that provide high levels of chemical productivity. Identification of productive extracts is accomplished without prior knowledge of target compounds that are present in the samples and is achieved with high throughput (∼50 samples/h) compared to other chemical screening strategies that require separation by high-resolution chromatography methods (24, 28).

Statistical analysis of ES-MS productivity scores by the paired t test provided a means to segregate the actinomycete population based on the magnitude of growth condition-dependent responses. This approach allowed us to rank cultivation conditions for individual cultures based on growth condition-dependent differences in the chemical productivity scores. Through use of this method, it was demonstrated that solid-state fermentation in medium A and submerged fermentation in medium B provided the highest levels of chemical productivity compared to other cultivation conditions. Parallel analyses of the same extracts from solid-state and submerged fermentations by both HPLC–ES-MS and ES-MS confirmed the ES-MS results and showed that the chemical productivity score was sensitive to most changes in the expression of secondary metabolites that occurred in response to growth conditions.

Solid-state fermentation was shown to provide the highest level of chemical productivity and diversity when it was compared to other cultivation conditions evaluated in this study. Solid-state growth conditions have previously been shown to elicit altered physiological states in a few, well-characterized filamentous microorganisms (2, 5, 32, 35). For example, mycotoxin production by the filamentous fungus Aspergillus flavus is enhanced more than twofold on the basis of weight when growth conditions are changed from submerged to solid-state fermentation (18, 19). Similar improvements in the yields of antibiotics and other secondary metabolites have been observed for a small group of actinomycetes and spore-forming nonfilamentous bacteria grown on solid substrates (22, 32, 39). In addition to changes in the expression of small molecules, solid-state fermentation has been shown to influence the expression of extracellular enzymes and the cellular localization of enzymes in actinomycetes and fungi (2, 35).

While this study and other studies have documented the advantages of solid-state fermentation processes for production of secondary metabolites, widespread application of solid-state procedures in fermentation processes has been hindered by difficulties in measuring the key fermentation process variables, including biomass, pH, nutrient concentration, and temperature (5, 31). Direct measurement of filamentous microorganism biomass on solid substrates is often complicated by attachment of substrate mycelia to the surface. Because of the difficulties in directly measuring cell biomass, a number of previous studies have utilized indirect ways to measure biomass, including glucosamine, total sugar, and DNA contents, and the rate of carbon dioxide production to indirectly monitor cell growth (9, 10, 38). Unfortunately, these indirect biomarkers provide only estimates of biomass and often cannot be used in studies of uncharacterized microorganisms without employing assumptions concerning the physiology of the microorganisms. To eliminate these problems, we developed a method for growing actinomycetes on an agar-supported nylon membrane. The yield of secondary metabolites produced in a solid-state fermentation can be directly quantified from the weight of biomass present on the membrane and the concentration of secondary metabolites extracted from the biomass. Growth of actinomycetes on the membrane surface had the additional benefit of providing extracts that were virtually free of contamination from the complex growth medium. Thus, the procedure is a way to produce high-quality actinomycete extracts that can be introduced directly into a mass spectrometer without the expense of the SPE step that was necessary without the membrane method. While growth on a filter membrane reduced problems associated with attachment of biomass to the agar surface or with contaminating medium components, the method may underestimate the concentrations of certain highly polar secondary metabolites that may diffuse from the filter disk during growth.

Treatments that enhanced chemical productivity in actinomycetes often created nonequivalent sample matrices. The most notable examples of treatment-dependent matrix interference included interference from residual medium components or other polar compounds associated with the growth media. An ability to suppress matrix effects associated with individual treatments was necessary to measure differences in expression of secondary metabolites that occurred in response to the various treatments. One approach to minimize matrix interference was to select treatments that did not directly contribute to the detector response of the mass spectrometer. The treatments in this group were specifically physical parameters (i.e., agitation rate and incubation temperature) and addition of compounds that did not ionize and compounds whose masses were below the mass range scanned by the mass spectrometer (γ-butyrolactones and Na2HPO4 [medium D], respectively). While this approach provided a higher level of assurance that treatment effects did not contribute to changes in the chemical productivity measurements, it severely limited the choice of potential treatments that could be evaluated. A second strategy, one that has been commonly employed in previous natural product research efforts, focused on selectively removing matrix interference while simultaneously enriching for compounds of interest (secondary metabolites) in the samples by solid-phase extraction. This strategy is based on the assumption that the majority of valuable drug leads come from moderately to highly nonpolar compounds that have masses ranging from 250 to 700 g/mol (4). Methods for enrichment of secondary metabolites from chemically complex matrices include extraction with water-immiscible organic solvents, such as ethyl acetate and chloroform, and solid-phase extraction on nonpolar stationary phases (13). In this study, solid-phase extraction on a C18 stationary phase was chosen as a means to enrich secondary metabolites from the complex organic matrices. The solid-phase extraction procedure ensured that ES-MS measurements responded mainly to the changes in the expression of target compounds having the druglike chemical and physical properties mentioned above.

Many laboratory investigations have shown that secondary metabolism in microorganisms is influenced by environmental parameters that affect cell physiology and biochemistry (13, 25, 33, 40). The results of this study confirmed the importance of selecting the appropriate growth conditions for expression of secondary metabolites from actinomycetes and quantified the relative effects of these conditions on secondary metabolism for a small set of actinomycetes by using a new chemical screening strategy. The results indicate that the ES-MS method is an efficient, high-throughput method for detecting and quantifying changes that occur in the expression of secondary metabolites from actinomycetes. This approach could be used to optimize conditions for expression of secondary metabolites from other microorganisms, to detect sources of variability in a single microorganism, or to optimize secondary metabolite extraction and sample preparation methods.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jeff Gygi, Mike Goodwin, John Scheuring, Dale Duckworth, Matt Clemens, and Mark Strege (Eli Lilly and Company) for insightful discussions and for the analysis of actinomycete extracts by ES-MS and HPLC ES-MS/ELSD.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel C B L, Lindon J C, Noble D, Rudd B A M, Sidebottom P J, Nicholson J K. Characterization of metabolites in intact Streptomyces citricolor culture supernatants using high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance and directly coupled high-pressure liquid chromatography-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:220–230. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acuna-Arguelles M E, Gutierrez-Rojas M, Viniegra-Gonzalez G, Favela-Torres E. Production and properties of three pectinolytic activities produced by Aspergillus niger in submerged and solid-state fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:808–814. doi: 10.1007/BF02431912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando N, Ueda K, Horinouchi S. A Streptomyces griseus gene (sga A) suppresses the growth disturbance caused by high osmolarity and high concentration of A-factor during early growth. Microbiology. 1997;143:2715–2723. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashton M J, Jaye M C, Mason J S. New perspectives in lead generation. II. Evaluating molecular diversity. Drug Discov Today. 1996;1:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrios-Gonzalez J, Mejia A. Production of secondary metabolites by solid-state fermentation. Biotechnol Annu Rev. 1996;2:85–121. doi: 10.1016/s1387-2656(08)70007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett J W, Bentley R. What's in a name?—microbial secondary metabolism. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1989;34:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beppu T. Secondary metabolites as chemical signals for cellular differentiation. Gene. 1992;115:159–165. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demain A L. Pharmaceutically active secondary metabolites of microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;52:455–463. doi: 10.1007/s002530051546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desgranges C, Vergoignan C, Georges M, Durand A. Biomass estimation in solid-state fermentation: manual biochemical methods. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:200–205. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desgranges C, Vergoignan C, Georges M, Durand A. Biomass estimation in solid-state fermentation: on-line measurements. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:206–209. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dreux M, Lafosse M, Morin-Allory L. The evaporative light scattering detector: a universal instrument for non-volatile solutes in LC and SFC. LC-GC Int. 1996;9:148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunny G M, Leonard B A. Cell-cell communication in gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:527–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franco C M M, Coutinho L E L. Detection of novel secondary metabolites. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1991;11:193–276. doi: 10.3109/07388559109069184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gayo L M. Solution-phase library generation: methods and applications in drug discovery. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1998;61:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grabley S, Thiericke R. Bioactive agents from natural sources: trends in discovery and application. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 1999;64:101–154. doi: 10.1007/3-540-49811-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guiochon G, Moysan A, Holley C. Influence of various parameters on the response factors of the evaporative light scattering detector for a number of non-volatile compounds. J Liq Chromatogr. 1988;11:2547–2570. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hara O, Beppu T. Mutants blocked in streptomycin production in Streptomyces griseus: the role of A-factor. J Antibiot. 1982;35:349–358. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesseltine C W. Solid-state fermentation, part 1. Proc Biochem. 1977;12:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hesseltine C W. Solid-state fermentation, part 2. Proc Biochem. 1977;12:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgs R E, Zahn J A, Gygi J D, Hilton M D. Rapid method to estimate the presence of secondary metabolites in microbial extracts. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:371–376. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.371-376.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Autoregulatory factors and communication in actinomycetes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:377–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jermini M F G, Demain A L. Solid-state fermentation for cephalosporin production by Streptomyces clavuligerus and Cephalosporium acremonium. Experientia (Basel) 1989;45:1061–1065. doi: 10.1007/BF01950159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julian R K, Higgs R E, Gygi J D, Hilton M D. A method for quantitatively differentiating crude natural extracts using high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3249–3254. doi: 10.1021/ac971055v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier A, Maul C, Zerlin M, Sattler I, Grabley S, Thiericke R. Biomolecular-chemical screening: a novel screening approach for the discovery of biologically active secondary metabolites. J Antibiot. 1999;52:945–951. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.52.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marahiel M A, Stachelhaus T, Mootz H D. Modular peptide synthetases involved in nonribosomal peptide synthesis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2651–2673. doi: 10.1021/cr960029e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCann P A, Pogell B M. Pamamycin: a new antibiotic and stimulator of aerial mycelia formation. J Antibiot. 1979;32:673–678. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.32.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metsa-Ketela M, Salo V, Halo L, Hautala A, Hakala J, Mantsala P, Ylihonko K. An efficient approach for screening minimal PKS genes from Streptomyces. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;180:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monaghan R L, Polishook J D, Pecore V J, Bills G F, Nallin-Omstead M, Streicher S L. Discovery of novel secondary metabolites from fungi — is it really a random walk through a random forest? Can J Bot. 1995;73(Suppl. 1):S925–S931. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montgomery D C. Design and analysis of experiments. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore J. NMR screening in drug discovery. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:54–58. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)80010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murthy M V R, Karanth N G, Raghava Rao K S M S. Biochemical engineering aspects of solid-state fermentation. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1993;38:99–147. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohno A, Ano T, Shoda M. Production of antifungal antibiotic, iturin in a solid-state fermentation by Bacillus subtilis nb22 using wheat bran as a substrate. Biotechnol Lett. 1992;14:817–822. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rose A H. Production and industrial importance of secondary products of metabolism. In: Rose A H, editor. Secondary products of metabolism. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1979. pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schimmel T G, Coffman A D, Parsons S J. Effect of butyrolactone I on the producing fungus, Aspergillus terreus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3707–3712. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3707-3712.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selvakumar P, Ashakumary L, Helen A, Pandey A. Purification and characterization of glucoamylase produced by Aspergillis niger in solid-state fermentation. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;23:403–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seow K T, Meurer G, Gerlitz M, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Hutchinson C R, Davies J. A study of iterative type II polyketide synthases, using bacterial genes clones from soil DNA: a means to access and use genes from uncultured microorganisms. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7360–7368. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7360-7368.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein J L, Simon M I. Archaeal ubiquity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6228–6230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugama S, Okazaki N. Growth estimation of Aspergillus oryzae cultured on solid media. J Ferment Technol. 1979;57:408–412. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang S S, Ling M Y. Tetracycline production with sweet potato residue by solid-state fermentation. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1989;33:1021–1028. doi: 10.1002/bit.260330811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yarbrough G G, Taylor D P, Rowlands R T, Crawford M S, Lasure L L. Screening microbial metabolites for new drugs: theoretical and practical issues. J Antibiot. 1993;46:535–544. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zähner H, Drautz H, Weber W. Novel approaches to metabolite screening. In: Bu'lock J D, Nisbet L J, Winstanley D J, editors. Bioactive microbial products: search and discovery. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]