Abstract

Translation is a tightly regulated process that ensures optimal protein quality and enables adaptation to energy/nutrient availability. The α-kinase eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF-2K), a key regulator of translation, specifically phosphorylates the guanosine triphosphatase eEF-2, thereby reducing its affinity for the ribosome and suppressing the elongation phase of protein synthesis. eEF-2K activation requires calmodulin binding and autophosphorylation at the primary stimulatory site, T348. Biochemical studies predict a calmodulin-mediated activation mechanism for eEF-2K distinct from other calmodulin-dependent kinases. Here, we resolve the atomic details of this mechanism through a 2.3-Å crystal structure of the heterodimeric complex of calmodulin and the functional core of eEF-2K (eEF-2KTR). This structure, which represents the activated T348-phosphorylated state of eEF-2KTR, highlights an intimate association of the kinase with the calmodulin C-lobe, creating an “activation spine” that connects its amino-terminal calmodulin-targeting motif to its active site through a conserved regulatory element.

Calmodulin activates eEF-2K through a unique structural mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic protein levels are predominantly controlled by mRNA translation (1), an energetically expensive process (2) that is highly regulated (3) to ensure optimal transit times for protein quality control (4) and to fashion the cellular response to environmental stress and changes in the availability of energy and/or nutrients (5). A primary driver of this regulation is the specific phosphorylation (on Thr56) of the guanosine triphosphate (GTP)–dependent translocase, eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF-2). This covalent modification, uniquely catalyzed by an atypical kinase, eEF-2 kinase (eEF-2K) (6, 7), diminishes the ability of eEF-2 to engage the ribosome and suppresses the elongation phase of protein synthesis (8, 9). Dysregulation of eEF-2K activity has been linked to neurological conditions such as Alzheimer’s-related dementia (10) and Parkinson’s disease (11). Aberrant eEF-2K function has been correlated with enhanced tumorigenesis (12), invasion, and metastasis (13). Given these properties, eEF-2K is an emerging target for the development of therapeutics against several diseases, including many cancers (14–16), and neuropathies (17), underscoring the importance of understanding its activation and regulation in mechanistic detail.

Members of the α-kinase family (18, 19), which includes eEF-2K, show poor sequence similarity with “conventional” kinases that comprise the branches of the eukaryotic kinome tree (20). While widely distributed in complex eukaryotes, vertebrates and invertebrates encode distinct α-kinases. eEF-2K is the only member of this family whose orthologs appear in both vertebrates and invertebrates, indicating its place in the evolutionary history of this family and highlighting its role in regulating a fundamental cellular process. The unique nature of eEF-2K is also underscored by the fact that it is the only α-kinase reliant on calmodulin (CaM) (6) for activation. Activation of eEF-2K has been suggested to occur through an allosteric process (21) mediated by its interaction with CaM. CaM binding enhances the apparent kcat of eEF-2K toward a peptide substrate by ~2400-fold without substantially altering affinity. Subsequent autophosphorylation at the primary up-regulating site (T348) provides an additional ~6-fold increase in kcat, yielding the fully activated state. This mechanism is distinct from those operative in other CaM-dependent kinases that rely on the CaM-induced displacement of an autoinhibitory segment to enable enhanced substrate access (22). eEF-2K activity is further modulated by Ca2+ (23), pH (24), and additional regulatory phosphorylation events (25) via multiple pathways including mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK), and extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) (12). Obtaining insight into eEF-2K activation and regulation in atomic detail has been hindered by the absence of structures of the full-length enzyme or its CaM-bound activated complex. We have identified a minimal functional construct of eEF-2K, eEF-2KTR (Fig. 1A and fig. S1), which is activated by CaM similarly to the wild-type enzyme and efficiently phosphorylates eEF-2 in cells (26). Using x-ray crystallography, we resolved the structure of its T348-phosphorylated state (peEF-2KTR) in an activated heterodimeric complex with CaM (CaM•peEF-2KTR) to 2.3 Å (details of the data collection and statistics are shown in Table 1). Almost four decades after its discovery and biochemical characterization (6), this structure provides the first critical insight into the atomic details of the unique mechanism of the CaM-mediated activation of eEF-2K. It lays the foundation for the structural interpretation of the large library of biochemical data available in the literature (23) while facilitating the rational design of small-molecule modulators targeting this unique enzyme for various human diseases (27).

Fig. 1. Structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex.

(A) Schematic representation of the structural modules of eEF-2K (top) indicating the calmodulin-targeting motif (CTM; cyan), the regulatory element (RE; pink), the kinase domain (KD; lime green), the regulatory loop (R-loop; dark gray), and the C-terminal domain (CTD; dark orange). The eEF-2KTR construct (bottom) is missing 70 N-terminal residues of eEF-2K, and a 6-glycine linker replaces the 359–489 segment of the R-loop. (B) Structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex in surface (top) and ribbon (bottom) representations; the CaM N-lobe (CaMN) and C-lobe (CaMC) are colored bright and dull yellow, respectively; the eEF-2KTR colors are the same as in (A). (C) Structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex fitted into the molecular envelope of one of two dominant clusters calculated from previously described small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) data acquired on the low-concentration sample of the CaM•eEF-2KTR complex (unphosphorylated T348) (26). The corresponding experimental data (blue circles), the theoretical fit (red curve), and the reduced residuals (Δ/σ) are shown (bottom). While the SAXS-generated envelope reproduces the overall structural features in solution, the reduced residuals at low s values and the relatively large χ2 value suggest differences between the molecular species. Some of these differences can be attributed to the fact that the SAXS data were acquired on the unphosphorylated complex in the presence of Ca2+ but in the absence of Mg2+.

Table 1. Data collection and refinement statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell. Rmerge = ∑|(I − <I>)|/∑I, where I is the observed intensity.

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | NSLS-II BEAMLINE 19-ID |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97946 |

| Space group | P3121 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 58.50, 58.50, 365.78 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 |

| Resolution (Å) | 121.9, 2.34 |

| (2.382, 2.342) | |

| R merge | 0.362 (1.778) |

| I/σ(I) | 14.5 (2.5) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) |

| Redundancy | 25.9 (24.5) |

| Wilson B factor | 14.99 |

| Number of unique reflections | 32,010 (1,494) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.66–2.34 |

| No. reflections | 31,982 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.2293/0.2520 |

| Number of nonhydrogen atoms | |

| Macromolecules | 5,117 |

| Ligands | 8 |

| Solvent | 144 |

| Protein residues | 637 |

| RMS (bond) (Å) | 0.003 |

| RMS (angles) (°) | 0.533 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Most favored (%) | 91.1 |

| Additionally favored (%) | 8.7 |

| Generously favored (%) | 0.2 |

| Disallowed (%) | 0.0 |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.38 |

| Clash score | 4.29 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | 35.37 |

| Macromolecules | 35.6 |

| Ligands | 29.35 |

| Solvent | 27.61 |

| PDB accession code | 7SHQ |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex reveals an elongated assembly

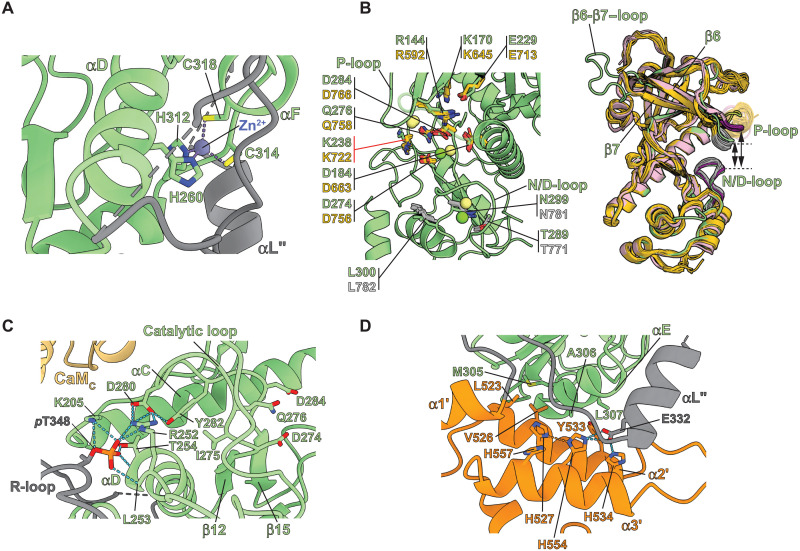

The CaM•peEF-2KTR complex forms an elongated structure (Fig. 1B) that is consistent with previous solution-state small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) measurements on the inactive complex (unphosphorylated T348) (Fig. 1C) (26). The kinase domain (KD) shows a characteristic α-kinase architecture, with its C-lobe (KDC) harboring the invariant structural Zn2+ ion coordinated in a tetrahedral arrangement by the side chains of H260, H312, C314, and C318 (Fig. 2A). While the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex was crystallized in the presence of the slowly hydrolyzable adenosine triphosphate (ATP) analog, adenylyl-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP), no density corresponding to bound nucleotide was seen. However, a comparison with the available structures of the related myosin heavy chain kinase A (MHCK-A) KD (Fig. 2B, left) (28, 29) allows the assignment of “catalytic” residues of eEF-2KTR. R144 (R592 in MHCK-A, α, and β phosphates), K170 (K645, α phosphate and the adenine ring), E229 (E713, adenine amino group), K238 (K722, water-mediated recognition of the γ phosphate), and Q276 (Q758, catalytic Mg2+ and γ phosphate) represent residues that likely coordinate the nucleotide, and D274 (D756) is the putative catalytic base. As seen for the case of the nucleotide-bound states of MHCK-A (Fig. 2B, right), the P and N/D-loops of peEF-2KTR are closed relative to each other, with the relevant ATP-coordinating residues (except perhaps K238, indicated by the red marker in Fig. 2B) in their proper orientations to coordinate nucleotide. It is therefore somewhat surprising that no bound nucleotide is seen in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex.

Fig. 2. Structural features of peEF-2KTR in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex.

(A) Tetrahedral coordination mode of the structural Zn2+ characteristic of α-kinases. (B) Comparison of the orientations of key catalytic residues (in green) of the eEF-2KTR KD in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex with corresponding residues (in dark yellow) in several structures of the related MHCK-A KD is illustrated on the left. Also shown (MHCK-A residues in light gray) are key N/D-loop residues discussed in the text. The Mg2+ ions seen in the structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex are shown in green, and those seen in the MHCK-A structures are shown in lime green. Right: Overlay of the KD of peEF-2KTR in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex (green) and MHCK-A KDs in their nucleotide-bound (dark yellow) or nucleotide-free structures (pink), with the corresponding P- and the N/D-loops colored light gray and dark magenta, respectively. A closed conformation of the P-loop relative to the N/D-loop in the presence of nucleotide is evident. This closed configuration is also seen for the eEF-2KTR KD in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex. (C) Interactions that stabilize pT348 at the phosphate-binding pocket (PBP) and couple the PBP to the active site are indicated. Key catalytic loop residues, including D274 (the putative catalytic base), Q276, and D284, are shown for reference. (D) Key interactions involving the αE-α2′-α3′ element that stabilize the KD/CTD interface. The H527-H554 δ-δ hydrogen bond is indicated by the orange dotted line.

In analogy to MHCK-A, the roles of T289 (T771 in MHCK-A), N299 (N781), and L300 (L782) on the N/D-loop (Fig. 2B, left) of eEF-2KTR may also be inferred. N299 is stabilized through hydrogen bonds with the T289 side chain and the D294 backbone. This “asparagine-in” conformation has been suggested to be characteristic of the active state of MHCK-A (28). In MHCK-A, N781 and L782 have been suggested to determine the accessibility of the active site. Given their similar spatial location and orientations, a similar role for the analogous N299 and L300 in eEF-2KTR can be envisaged.

It is to be mentioned that while the eEF-2KTR KD, like those of the related MHCK-A (28) and ChaK (30), displays a characteristic dual lobe fold seen in conventional eukaryotic protein kinases, structural deviations are evident (fig. S2A). A higher degree of similarity is seen for the N-lobe (KDN) than KDC, with the latter displaying structural features that resemble an ATP-grasp fold (31), as noted before (30). The spatial distribution of eEF-2KTR catalytic residues is also distinct compared to conventional kinases (fig. S2B), indicative of its significant divergence from the latter.

As noted above, in the structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex the primary activating T348 is phosphorylated (pT348; fig. S3). pT348 docks into a phosphate-binding pocket (PBP) forming hydrogen bonds with the K205, R252, and T254 side chains, and the L253 and T254 backbones (Fig. 2C). D280 on the catalytic loop hydrogen bonds with the side chains of R252 and Y282. This interaction promotes methyl-π interactions between I275 and Y282 (Fig. 2C), thereby coupling the catalytic site to the PBP. In some structures of the MHCK-A KD, the conserved residues D663 (29) and D766 (28) (Fig. 2B, left) were found to be phosphorylated. These phospho-aspartyl species were proposed to influence activity. We do not find evidence of phosphorylation on the equivalent residues (D184 and D284) in eEF-2KTR within the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex.

The all-helical C-terminal domain (CTD) represents a feature unique to eEF-2K that forms a docking platform for eEF-2 (25, 32). The α2′-α7′ region displays a pattern typical of SEL1-like repeats (33), the α8′-α10′ segment partially deviates from this arrangement, and α1′ is somewhat disengaged from the rest of the CTD. α2′ stabilizes the KD/CTD interface, interacting with αE on KDC and α3′ (Fig. 2D). The αE-α2′ interface features hydrophobic interactions involving Y533 that is sandwiched by A306 and L307, with V526 inserted between M305 and L523. A curious feature within the αE-α2′-α3′ element is the linear spatial positioning of three conserved (fig. S1) His residues (H527 and H534 on α2′; H554 on α3′; Fig. 2D); the also spatially proximal H557 (on α3′) stacks with H527. H554 forms a rare δ-δ hydrogen bond with H527 (34). H534 and H554 form salt bridges with the conserved E332 on a helical R-loop segment (αL″). It is tempting to speculate that alternative protonation states of one or more of these His residues would modify interactions within the KD/CTD interface, and perhaps its coupling to the R-loop, through the αE-α2′-α3 element, and thereby contribute to the observed pH response of the enzyme (24). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies (32) have localized the eEF-2 docking site to the C terminus of the CTD (α9′-α10′), ~60 Å away from the active site, suggesting that distinct interactions drive eEF-2 recognition and its subsequent phosphorylation.

The C-terminal lobe of CaM plays a dominant role in recognizing peEF-2KTR

CaM contacts peEF-2KTR in an extended conformation using both its N- (CaMN) and C-terminal (CaMC) lobes, with CaMC being more intimately associated with the kinase (Fig. 3A). This assembly is consistent with changes in protection seen in previous hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry (HXMS) analyses (fig. S4) (26, 35). All four CaMC helices engage the CaM-targeting motif (CTM) through their hydrophobic faces in a Ca2+-bound “open” conformation of the lobe, and all, except αH, interact with KDN using their predominantly hydrophilic faces. A deep hydrophobic pocket, lined by the side chains of Ala88 (three-letter codes used for CaM residues), Phe92, Ile100, Leu105, Met124, Ile125, Val136, Phe141, Met144, and Met145, accommodates W85 from the eEF-2KTR CTM. Additional hydrophobic interactions of I89 with Ala88 and Met145, and of A92 with Val91 and Leu112 generate a 1-5-8 binding mode (Fig. 3B) within a helical CTM as in the NMR structure of the complex of CaM with a peptide encoding the CTM (CTM-pep, 74–100) (36). However, no CaMC-bound Ca2+ ions were seen in the peptide complex (36). The hydrophilic face of CaMC makes numerous contacts with KDN over a large interaction surface (Fig. 3C). A “virtual alanine scan” at this interface identified several contacts involving residues for which in silico Ala mutations are substantially destabilizing (ΔΔG > 1.5 kcal/mol) (37). These include Asp95 and Ser101 on CaMC and K192 and D208 on the eEF-2KTR KD; the side chains of all these residues form a mesh of hydrogen bonds centered on K192 (ΔΔG = 2.5 kcal/mol). Other notable interactions at the interface include a hydrogen bond between the Arg90 side chain and the A164 backbone and an L281-His107 methyl-π interaction. These interactions collectively localize the CTM-tethered CaMC behind the kinase active site. An additional salt bridge between Asp122 and R351 couples CaMC to the R-loop. In contrast, CaMN appears to interact more superficially with peEF-2KTR within the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex. The β6-β7–loop on KDN associates with shallow hydrophobic grooves on CaMN; F155 interacts with Leu39 and Phe12, and L156 with Leu4 and Met76 (Fig. 3D).

Fig. 3. Intermolecular interactions between CaM and peEF-2KTR.

(A) CaM and eEF-2KTR are shown in ribbon and surface representations, respectively. The constituent helices of CaMN (αA-αD) and CaMC (αE-αH) are indicated. Interactions with the hydrophobic (B) and hydrophilic (C) faces of CaMC with the CTM and KDN, respectively, are illustrated. (D) Interactions of CaMN with the β6-β7–loop of KDN. Elements not directly involved in the interaction are hidden to aid visualization.

The N-terminal lobe of CaM adopts a closed conformation in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex

Contrasting its Ca2+-bound open conformation seen in the CTM-pep complex (36), CaMN is in an Mg2+-bound “closed” state (38) when engaged to peEF-2KTR (Fig. 4, A and B). To the best of our knowledge, this conformation has not been previously observed in a CaM complex. CaMN is further stabilized through numerous crystal contacts with symmetry-related neighbors (Fig. 4C). Given this unique conformation and the high Mg2+concentration used for crystallization, we tested the influence of Mg2+ on CaMN/peEF-2KTR interactions in solution. While free Mg2+ in mammalian cells remains relatively constant at ~1 mM (39), the Ca2+ concentration, ~50 to 100 nM in resting cells, can be enhanced to as much as ~100 μM (40) in calcium microdomains under specific stimuli. The Ca2+:Mg2+ ratio (1:100) used for crystallization lies well within this cellular range. It is notable that eEF-2KTR retains the ability to efficiently autophosphorylate on T348 under these conditions (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. Conformation of CaMN in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex.

(A) Conformation of CaMN in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex (yellow) and that bound to Mg2+ (orange; PDB:3UCW) (38); the corresponding bound Mg2+ ions are shown as light or dark green spheres. (B) The conformation of CaMN in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex is compared with that in the NMR structure (gray, PDB: 5J8H) of the complex with CTM-pep in the presence of Ca2+ (36). CaMN engages peEF-2KTR in a Mg2+-bound closed conformation rather than a Ca2+-bound open conformation as in the CTM-pep complex. The metal ions have been omitted for clarity. (C) Interactions between two neighboring CaMN units (yellow and green) related by symmetry within the crystal are shown as ribbons (left) or surfaces (right). The extensive crystal contacts involving αC and αD (the interactions with peEF-2KTR largely involve hydrophobic residues on αA and αB) suggest that this arrangement stabilizes the complex within the lattice. (D) eEF-2KTR retains the ability to efficiently autophosphorylate on T348 under conditions where the Ca2+ to Mg2+ ratio (1:100) are similar to that used for crystallization. The time courses for T348 autophosphorylation measured using two different sets of concentrations for Ca2+ and Mg2+ while holding their ratio constant are shown.

NMR analyses (Fig. 5) using Ile-δ1 and Met-ε resonances of CaM (see fig. S5 for representative spectra) indicate no appreciable perturbations in the CaMC resonances with increasing Mg2+ concentration within a complex formed in the presence of Ca2+. This suggests that Mg2+, even at very high concentrations, is unable to significantly affect the interactions of peEF-2KTR with CaMC. In contrast, CaMN resonances display evidence of exchange between Ca2+- and Mg2+-bound conformations with increasing Mg2+. At a very high Mg2+ concentration where the Ca2+:Mg2+ ratio is heavily skewed toward Mg2+, as in resting cells, CaMN disengages from peEF-2KTR.

Fig. 5. Influence of the Ca2+/Mg2+ ratio on CaM within the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex in solution.

(Top) Chemical shift perturbations induced by peEF-2KTR on IM-labeled CaM in the presence of Ca2+ (and the absence of Mg2+). Fully broadened resonances are indicated by the gray bars. The largest perturbations are observed for CaMC. The patterns of perturbations are similar to those induced by the presence of eEF-2KTR (unphosphorylated T348) (41), suggesting that the CaM recognition modes of eEF-2KTR and peEF-2KTR are similar in the two cases. (Middle) Perturbations induced by Mg2+ (450 mM MgCl2) on IM-labeled CaM in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex (containing 300 μM CaCl2). Significant perturbations are seen on CaMN; minimal perturbations are seen for CaMC (except for the Met109 resonance that is broadened to below the noise). (Bottom) Perturbations in IM-labeled CaM comparing the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex in buffer containing 300 μM CaCl2 and 450 mM MgCl2, with CaM alone in the presence of 310 mM MgCl2. The data suggest that, at high concentrations, Mg2+ replaces Ca2+ on CaMN, leading to its disengagement from peEF-2KTR.

As noted earlier, the CaMC metal-binding sites also appear to be occupied by Ca2+ in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex, contrasting our previous studies on the CaM•CTM-pep (36) and CaM•eEF-2KTR (41) complexes, both carried out in the absence of Mg2+ using high- and low-resolution NMR approaches, respectively. Given the similar open configuration of CaMC in the complexes with peEF-2KTR and CTM-pep, it is apparent that minor rearrangements of its Ca2+-binding EF-hands would suffice to accommodate Ca2+. A difference in the engagement of CaMC by the CTM (a shift of approximately half a helical turn) is seen upon comparing the two cases; the small accompanying changes in the corresponding EF-hands appear sufficient to accommodate Ca2+ (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Comparison of the CaMC/CTM module in the peEF-2KTR and CTM-pep complexes.

(A) The CaMC/CTM modules in the NMR ensemble of the complex of CaM with CTM-pep (PDB: 5J8H) (36) or in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex are compared. CaMC (CTM) is shown in red (magenta) and dark blue (light blue) in the NMR and crystal structures, respectively. The CTM is displaced by approximately half a helical turn within CaMC in the crystal structure compared to that in the NMR ensemble. The W85 and I89 side chains are shown for only five representative structures of the NMR ensemble for ease in visualization. The W85 side chain occupies a similar spatial position, on average, in the crystal structure and the NMR ensemble. The orientation of the side chains of I89 and A92 (hidden) is significantly different in the two cases. (B) Backbone traces of the Ca2+-binding EF-hands (EF3 and EF4) of CaMC in the NMR ensemble (red) of the CaM•CTM-pep complex illustrate their displacement from the spatial positions seen in the crystal structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex (blue). These displacements make the CaMC EF-hands unsuitable for coordinating Ca2+ (shown as gray spheres for the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex) in the CaM•CTM-pep complex.

It has been shown that the maximal activity of eEF-2K toward a peptide substrate is independent of Ca2+ with similar kcat values obtained in its absence (11 s−1) or presence (25 s−1), contrasting an ~900-fold increase in the apparent Ca2+-induced CaM affinity (37 μM versus 42 nM) (42). The similar kcat values suggest that divalent cations (Mg2+ or Ca2+) within CaM minimally influence the nature of the active complex. Instead, we predict that the predominant role of these ions is to modulate the overall affinity of the CaM/eEF-2KTR interactions, i.e., to alter the “concentration” of the complex through additional interactions largely independent of those that define the active state.

The C-terminal lobe of CaM couples to the peEF-2KTR active site

The loop [regulatory element (RE)] that connects the eEF-2KTR CTM and KD contains a 96PDPWA100 sequence, fully conserved in vertebrates (97DPW99 is universally conserved), that has been deemed essential for activity (43). In the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex, D97, aligned through the flanking P96 and P98, forms hydrogen bonds to the backbones of W99 and A100 using its side chain and backbone, respectively. This conformation generates a bulge within the RE, placing W99 within a pocket created by the side chains of P98, F102, F138, R148, V168, and Y231 (Fig. 7A). This configuration aligns an “activation spine” [invoking Kornev et al. (44)] comprising CaMC and highly conserved, predominantly hydrophobic (except R148) residues of the CTM, RE, and KDN to support the energetic coupling of CaM binding to the active site through the bound ATP (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7. Activation of eEF-2KTR by CaM.

(A) Key interactions of the RE with KDN. (B) Residues of the activation spine that connect CaMC (in dull yellow) to the eEF-2KTR active site are illustrated. eEF-2KTR residues are colored according to their AL2CO conservation scores (cyan, variable; maroon, fully conserved). The colors of the corresponding labels indicate the domains that the residues belong to. Residues of the RE are labeled in black font to avoid confusion with the AL2CO coloring scheme. Labels for catalytic site residues are italicized. AMP-PNP, which is missing in the structure, has been modeled in. (C) Activity of wild-type full-length eEF-2K (WT, black) and the corresponding W85A (blue) and W99A (red) mutants determined using a fluorescence-based kinetic assay are indicated. The experimental data are indicated by the filled circles, and the lines indicate fits to Eq. 2. Error bars indicate SDs over n = 2 (WT) and n = 3 (mutants) measurements. The inset shows an expansion of the activity profiles of the two mutants.

Given the close-packed nature of the spine in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex, one would predict that its disruption would have profound functional consequences. For example, a W99A mutation is expected to be substantially more perturbative than replacement by a similarly sized Leu, as borne out by functional studies (45). Furthermore, P98 hydroxylation (43) or a His107Lys mutation (24), both of which would significantly misalign the spine, are deleterious to function. This effect contrasts with a more modest impact of a less disruptive His107Ala mutation (24). In addition, sequence analyses suggest that mutations in the least, but still significantly conserved, spine residues, F138 and R148, covary with a nearby catalytic residue, R144. These are P139/P149/V145 in Ursus americanus and V137/V147/K143 in Bos mutus, perhaps resulting in nonfunctional enzymes. Thus, in our proposed model, W85 provides intrinsic binding energy (46) for the interaction with CaMC (36), which is used, in part, to stabilize the configuration of the spine and concomitantly the active state of the kinase; W99 only contributes to the latter effect. To test this prediction, we used our previously developed fluorescent peptide substrate (Sox-tide) (47) to test the influence of CaM concentration on the activity of full-length wild-type eEF-2K and corresponding W85A and W99A spine mutants (Fig. 7C). As expected, a W85A mutation leads to an ~9-fold reduction in the catalytic activity (wild-type, 0.63 ± 0.02 s−1; W85A, 0.07 ± 0.002 s−1) and an ~8-fold decrease in the CaM affinity (wild-type, 44 ± 5 nM; W85A, 353 ± 29 nM). In contrast, a W99A mutation leads to an ~32-fold decrease in the catalytic activity (kobs,max = 0.02 ± 0.001 s−1) without affecting CaM affinity (38 ± 10 nM).

Our structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex provides a framework to interpret, in atomic detail, the large body of biochemical and functional data generated by almost 4 decades of work on the unique enzyme that is eEF-2K. This structure, combined with current and previous biochemical/biophysical measurements, suggests a central role of CaMC in activating eEF-2K and defining the nature of the active state. In contrast, CaMN appears to play a more supporting role, serving primarily as a sensor of dynamic changes in Ca2+, e.g., during neuronal Ca2+ spikes/waves, in the face of a relatively constant Mg2+ level, to enhance the cellular concentration of active complex. A similar Ca2+-induced shift between functional states has been suggested by time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) studies of CaM in its complex with the ryanodine receptor (RyR1 isoform) (48). In analogy to that suggested by structures of the CaM complexes of the ryanodine receptor (RyR2 isoform) in their high and low Ca2+ states (49), this is likely achieved by altering the interaction of eEF-2K with CaMN (and perhaps also with CaMC) through Ca2+ binding and a transition to an open state of the lobe from its Mg2+-bound closed state. Overall, this regulation mechanism ensures the maintenance of basal levels of the active species and optimal elongation rates through eEF-2 phosphorylation under normal cellular conditions while allowing its rapid modulation in response to specific signals. A further wrinkle in this picture is the possible role of pH that, as previously mentioned, influences the activity of eEF-2K (24). Alterations in pH have been suggested to mimic Ca2+-driven conformational changes in CaM (50), providing another mechanism to modulate the metal ion requirement of the CaM/eEF-2K interaction.

Another question about eEF-2K regulation that remains unresolved by the current structure concerns the mechanism of the stimulatory autophosphorylation on S500 (51), which is also a target of protein kinase A (PKA) (52). S500 is buried in a shallow pocket lined by the side chains of H260, E264, H268, and F309 on the face opposite key catalytic elements, more than 20 Å away from the base, D274 (Fig. 8). Autophosphorylation in cis could, in principle, be achieved by a partial unfolding of α1′, with the added flexibility provided by an intact R-loop in full-length eEF-2K. Autophosphorylation on S500 is extremely slow and requires prior phosphorylation on T348 (42); we could not detect phosphorylation on S500 in peEF-2KTR despite incubation with Ca2+ and Mg2+/ATP over 1 hour. Alternatively, autophosphorylation in trans (or phosphorylation by PKA) would require less substantial structural transitions and occur within a transiently assembled 2:2 species with an antiparallel arrangement of its constituent CaM•peEF-2KTR subunits. Such an assembly would be compatible with our previous cross-linking MS results (26), which are not consistent with the current heterodimeric structure (fig. S6), without invoking marked conformational changes. Native MS studies on the CaM•eEF-2KTR complex reveal charge states corresponding to a 2:2 complex, albeit at extremely low levels (26). Similar questions regarding the conformational changes that enable (or follow) other regulatory phosphorylation events, e.g., on S366 [a target for p90RSK (53)], also remain unresolved since several of these modulatory R-loop sites are missing in eEF-2KTR.

Fig. 8. The binding site of S500 in the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex.

S500, the secondary site of activating autophosphorylation, is buried in a pocket within KDC, being stabilized through hydrogen bonds involving the side chains of the Zn2+-coordinating H260, and E264, at a significant distance from the catalytic site (e.g., the S500,Oγ–D274,Oδ1 and S500,Oγ–K170,Nζ distances are 20.0 and 29.7 Å, respectively), suggesting that autophosphorylation at this position in cis would require significant conformational rearrangements, including a partial unfolding of α1′. The position of pT348 bound at the PBP is also shown for reference.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystallization of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex

The protocols used for the expression and purification of eEF-2KTR and CaM, the selective phosphorylation of the former at T348 (to generate peEF-2KTR), and the subsequent purification of the 1:1 heterodimeric CaM•peEF-2KTR complex were performed as described previously (26, 35). The final samples used in the crystallization trials consisted of ~11.0 mg/ml of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex in a buffer containing 20 mM tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 3.0 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP; GoldBio), 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1.0 mM AMP-PNP (MilliporeSigma). Initial screens to identify crystallization conditions were performed under oil at the National Crystallization Center at the Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute. Potential conditions were further optimized in-house, and optimal conditions were identified as the following: 100 mM bis-tris (pH 6.9), 200 to 300 mM MgCl2, and 20 to 26% PEG3350 (polyethylene glycol 3350) combined in a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio plated on Greiner 72-well micro-batch plates (Hampton Research) under paraffin oil (EMD Chemicals) at ambient temperature. Multiple crystal clusters emerged in less than 12 hours, reaching their maximum size within a few days. Most of these, however, were extremely fragile and diffracted poorly. A single condition, 1:1 ratio, 24% PEG3350, and 300 mM MgCl2, yielded crystals that produced diffraction data of good quality.

Structure determination

Data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II) light source at Brookhaven National Laboratory using the 19-ID (NYX) beamline. Two datasets collected on distinct regions of the same crystal were processed and combined using the autoPROC toolbox (54), resulting in a dataset with a resolution of 2.3 Å. The crystal (P3121) with an elongated unit cell (a = b = 58.49 Å, c = 365.78 Å) contained a single CaM•peEF-2KTR heterodimer in the asymmetric unit. Initial phases were obtained using Phenix.mr_rosetta (55) and an alignment file obtained from the HHpred server (56) containing 53 entries, including sequences corresponding to the crystal structures of the α-kinase domains of MHCK-A (28, 29), ChaK (30), together with those of several SEL-1 and tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) containing proteins. The initial model was built using multiple cycles consisting of Phaser (57), Coot (58), and phenix.refine (59). At the end of the initial build, further optimization was carried out using the PDB_REDO server (60), yielding a model that contained 469 eEF-2KTR residues (88%) and the C-lobe of CaM. Most of the CaM N-lobe (except the loop between helices αC and αD) was built through iterative manual fitting with Coot followed by refinement using Phenix. A comparison of the CaM N-lobe fold with existing CaM structures using the DALI server (61) showed its close resemblance to a Mg2+-bound closed form. Molecular replacement using Phaser and PDB:3UCW (38) and the rest of the CaM•eEF-2KTR complex structure yielded a nearly complete model. The remaining missing segments of the structure of the complex were then progressively added and improved using Coot, phenix.refine, and ISoLDE (62). Cations were identified using the CheckMyBlob server (63) and inserted with solvent molecules using Coot and refined using Phenix. The final structural model consisted of 493 and 145 residues of eEF-2KTR (92.8%) and CaM (97.9%), respectively, together with 1 Zn2+, 2 Ca2+, and 5 Mg2+ ions and 145 water molecules. No density for AMP-PNP was discernible. Details about data collection and refinement are shown in Table 1.

Sequence analysis

The degree of sequence conservation in eEF-2K was obtained using the ConSurf server (64). ConSurf defines a conservation score based on the evolutionary rate of a particular position through alignment and phylogenetic analysis of homologous sequences. A total of 150 sequences from the nonredundant UniRef90 database (65) were selected using the HMMER algorithm (E value cutoff 0.0001) (66), aligned using MAFFT-NS-i (67) with maximum and minimum sequence identity cutoffs of 95% and 35%, respectively, and used to derive normalized conservation scores. The conservation scores were distributed into nine bins (grades), with the most variable and the most conserved occupying bins 1 and 9, respectively. The generated alignment file was read into UCSF ChimeraX (68) and represented on the eEF-2KTR structure, with the corresponding residues colored by their AL2CO scores (69).

Solution NMR spectroscopy

13C,1H-Ile-δ1, Met-ε, 2H,15N-labeled CaM (IM-labeled CaM) (41) and unlabeled peEF-2KTR (35) were prepared as previously described, and the corresponding 1:1 heterodimeric complex was purified as described above. All NMR samples (unless specifically noted) were prepared in a buffer (NMR buffer) containing 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 1.0 mM TCEP, and 5% 2H2O. The following samples were prepared: (i) IM-labeled CaM alone (~100 μM) in NMR buffer containing 3.0 mM CaCl2 or (ii) as part of the corresponding CaM•peEF-2KTR complex (~147 μM); (iii) IM-labeled CaM (~100 μM) in NMR buffer containing 5.0 mM EGTA and 310 mM MgCl2; (iv) IM-labeled CaM alone (~100 μM) in NMR buffer containing 3.0 mM CaCl2 and 300 mM MgCl2 or (v) as part of the corresponding CaM•peEF-2KTR complex (~147 μM); (vi) ~50 μM samples of IM-labeled CaM in NMR buffer containing ~150 μM 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) and 0, 0.2, 0.4, 5.0, 20, 103, or 310 mM MgCl2 (all samples contained EGTA in an ~1:60 ratio with respect to Mg2+); (vii) samples containing ~18 μM of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex in buffer comprising 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, ~150 μM DSS, and 0.3 mM CaCl2 with 0, 1.0, 3.0, 6.0, 12.0, 36, 68, 115, 240, and 450 mM MgCl2. 1H,13C SOFAST-HMQC (70) experiments were carried out on all samples using sweep widths of 13.95 parts per million (ppm) (512 complex points) and 12.0 ppm (128 complex points) in the direct and indirect dimensions, respectively. All experiments were carried out at 25°C on an 800-MHz Bruker Avance-III HD spectrometer equipped with a triple-resonance cryogenic probe capable of applying pulsed-field gradients along the z axis. Data were processed using nmrPipe (71) and analyzed using nmrViewJ (72). Chemical shift perturbations (Δδ in ppm) were calculated using (41)

| (1) |

where δref,H and δref,C are the reference 1H and 13C methyl chemical shifts, respectively, and δH and δC are the corresponding shifts in the presence of relevant ligands.

Small-angle x-ray scattering

SAXS data were acquired on two samples containing 1.9 mg/ml (lc) and 6.4 mg/ml (hc) of the CaM•eEF-2KTR complex (unphosphorylated eEF-2KTR), as previously described (26). These data were reanalyzed using ATSAS 3.0.1 software (73), and identical results as those shown in table 3 of Will et al. (26) were obtained. However, a slightly different approach was used to obtain ab initio three-dimensional models from the SAXS data. Twenty-five structures were calculated for each of the hc and lc datasets using DAMMIF (74) using default parameters in the slow mode and clustered using DAMCLUST (75). For the hc dataset, a total of six clusters were obtained in which three (hc_1, hc_2, and hc_4) contained a single member, one each contained two (hc_5) or three (hc_3) members, and the largest cluster [hc_6; normalized spatial discrepancy (NSD) to all other clusters = 1.47 ± 0.31] consisted of 17 members. The averaged envelope from 6_hc was refined against the experimental hc dataset (χ2 = 0.9766) using DAMMIN (76) (run in the slow mode using default parameters) by restricting the search volume using DAMSTART. For the lc dataset, two clusters contained a single member (lc_1 and lc_2), one each contained three (lc_5), five (lc_6), seven (lc_3), or eight members (lc_4). Thus, the averaged structures from the two largest clusters (lc_3 and lc_4, NSD = 1.16) were separately refined against the experimental lc dataset (χ2 = 0.7761 and χ2 = 0.7767 for lc_3 and lc_4, respectively).

The SAXS profile was calculated from the structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex using CRYSOL3 (77) and fitted separately to the lc and hc datasets, yielding χ2 values of 1.504 and 3.217, respectively, suggesting that the former provides a somewhat better agreement with that expected from the structure. The molecular envelopes calculated from each dataset (lc_3, lc_4, and hc_6) were superimposed on the crystal structure using SUPCOMB (78). The structure of the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex fitted into the refined molecular envelope of the lc_3 cluster, and a comparison of the theoretical and calculated data for the lc dataset is shown in (Fig. 1C).

Measurement of eEF-2KTR activity in the presence of Mg2+

Autophosphorylation of eEF-2KTR (500 nM) was carried out in buffer comprising 25 mM Hepes (pH 7.0), 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), bovine serum albumin (BSA; 40 μg/ml), 50 mM KCl, and 5 μM CaM. The reaction was conducted under two distinct conditions—one with 15 mM MgCl2 and 0.15 mM CaCl2 and a second with 150 mM MgCl2 and 1.5 mM CaCl2. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 10 min, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 500 μM [γ-32P]ATP (100 to 1000 cpm/pmol) in a final volume of 250 μl. Aliquots (10 pmol/20 μl) of eEF-2KTR were removed every 0, 10, 23, 32, 40, 60, 120, and 300 s over a 5-min time period and directly added to hot SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample loading buffer containing 125 mM tris-HCl (pH 6.75), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 10% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol, 4% SDS, and 0.02% bromophenol blue to quench the reaction. The mixture was further heated for 5 min at 95°C to ensure complete denaturation. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Gels were exposed for 8 hours in a phosphorimager cassette, scanned in a Typhoon 9500 imager, and analyzed using ImageJ. Autophosphorylation was quantified by drying the gels and excising the eEF-2KTR–containing segments. The radioactivity was measured with a Packard 1500 liquid scintillation analyzer.

Measurement of the activity of full-length eEF-2K and spine mutants

Assays were performed in buffer containing 25 mM Hepes, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 150 μM CaCl2, BSA (20 μg/ml), 100 μM EGTA, 2 mM DTT, 0 to 4 μM CaM, and 10 μM Sox-tide (47). The assays used concentrations (CE) of 5, 10.5, or 8.5 nM for unphosphorylated wild-type eEF-2K, the W85A mutant, or the W99A mutant, respectively. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 1 mM ATP. Product turnover was monitored by fluorescence (excitation at 360 nm and emission at 482 nm) using a Synergy H4 plate reader (BioTek). To convert the fluorescence data into rate constants (kobs), the protocol described by Devkota et al. (79) was used. The variation of kobs with CaM concentration (CCaM) was fitted to Eq. 2 to obtain the maximal rate at saturating CaM (kobs,max) and the CaM affinity (KCaM) values. Experiments were performed in duplicate (for wild-type) or in triplicate (for the W85A and W99A mutants).

| (2) |

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Hajredini and K. Lee (Harvard Medical School) for comments about the work. We also thank K. Battaile (New York Structural Biology Center) for support during data collection and analysis.

Funding: This work is supported by NIH award R01 GM123252 (to K.N.D. and R.G.) and the Welch Foundation F-1390 (K.N.D.). The National Crystallization Center at Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute is supported through NIH award R24 GM141256. Use of the NYX beamline (19-ID) at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS II) is supported by the member institutions of the New York Structural Biology Center. NSLS II is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under contract DE-SC0012704.

Author contributions: A.P. prepared samples for all biophysical measurements and optimized crystallization conditions together with E.A.I.; A.P. and E.A.I. collected crystallographic data; A.P. calculated and refined the structural model with support from E.A.I. and D.J.; A.P. performed and analyzed all the solution NMR measurements; K.L., A.L.B., and E.A.K. performed the functional studies; N.W. designed the eEF-2KTR construct; K.N.D. and R.G. developed the project; A.P. generated the first draft of the manuscript and figures, which K.N.D. and R.G. subsequently refined with input from all the authors.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Atomic coordinates for the CaM•peEF-2KTR complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with accession code 7SHQ. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S6

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Liu Y., Beyer A., Aebersold R., On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 165, 535–550 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buttgereit F., Brand M. D., A hierarchy of ATP-consuming processes in mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 312( Pt 1), 163–167 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schuller A. P., Green R., Roadblocks and resolutions in eukaryotic translation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 526–541 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein K. C., Frydman J., The stop-and-go traffic regulating protein biogenesis: How translation kinetics controls proteostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 2076–2084 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han N.-C., Kelly P., Ibba M., Translational quality control and reprogramming during stress adaptation. Exp. Cell Res. 394, 112161 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nairn A. C., Bhagat B., Palfrey H. C., Identification of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III and its major Mr 100,000 substrate in mammalian tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 7939–7943 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nairn A. C., Palfrey H. C., Identification of the major Mr 100,000 substrate for calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III in mammalian cells as elongation factor-2. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 17299–17303 (1987). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryazanov A. G., Shestakova E. A., Natapov P. G., Phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 by EF-2 kinase affects rate of translation. Nature 334, 170–173 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryazanov A. G., Davydova E. K., Mechanism of elongation factor 2 (EF-2) inactivation upon phosphorylation. Phosphorylated EF-2 is unable to catalyze translocation. FEBS Lett. 251, 187–190 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang W., Zhou X., Ryazanov A. G., Ma T., Suppression of the kinase for elongation factor 2 alleviates mGluR-LTD impairments in a mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 98, 225–230 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jan A., Jansonius B., Delaidelli A., Bhanshali F., An Y. A., Ferreira N., Smits L. M., Negri G. L., Schwamborn J. C., Jensen P. H., Mackenzie I. R., Taubert S., Sorensen P. H., Activity of translation regulator eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase is increased in parkinson disease brain and its inhibition reduces alpha synuclein toxicity. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 6, 54 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leprivier G., Remke M., Rotblat B., Dubuc A., Mateo A.-R. F., Kool M., Agnihotri S., El-Naggar A., Yu B., Somasekharan S. P., Faubert B., Bridon G., Tognon C. E., Mathers J., Thomas R., Li A., Barokas A., Kwok B., Bowden M., Smith S., Wu X., Korshunov A., Hielscher T., Northcott P. A., Galpin J. D., Ahern C. A., Wang Y., McCabe M. G., Collins V. P., Jones R. G., Pollak M., Delattre O., Gleave M. E., Jan E., Pfister S. M., Proud C. G., Derry W. B., Taylor M. D., Sorensen P. H., The eEF2 kinase confers resistance to nutrient deprivation by blocking translation elongation. Cell 153, 1064–1079 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie J., Shen K., Lenchine R. V., Gethings L. A., Trim P. J., Snel M. F., Zhou Y., Kenney J. W., Kamei M., Kochetkova M., Wang X., Proud C. G., Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase upregulates the expression of proteins implicated in cell migration and cancer cell metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 142, 1865–1877 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Temme L., Asquith C. R. M., eEF2K: An atypical kinase target for cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 577 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu S., Liao M., Tan H., Zhu L., Chen Y., He G., Liu B., Inhibiting eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase: An update on pharmacological small-molecule compounds in cancer. J. Med. Chem. 64, 8870–8883 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russnes H. G., Caldas C., eEF2K—A new target in breast cancers with combined inactivation of p53 and PTEN. EMBO Mol. Med. 6, 1512–1514 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beretta S., Gritti L., Verpelli C., Sala C., Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase a pharmacological target to regulate protein translation dysfunction in neurological diseases. Neuroscience 445, 42–49 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryazanov A. G., Pavur K. S., Dorovkov M. V., Alpha-kinases: A new class of protein kinases with a novel catalytic domain. Curr. Biol. 9, R43–R45 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middelbeek J., Clark K., Venselaar H., Huynen M. A., van Leeuwen F. N., The alpha-kinase family: An exceptional branch on the protein kinase tree. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 67, 875–890 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manning G., Whyte D. B., Martinez R., Hunter T., Sudarsanam S., The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298, 1912–1934 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavares C. D. J., Ferguson S. B., Giles D. H., Wang Q., Wellmann R. M., O’Brien J. P., Warthaka M., Brodbelt J. S., Ren P., Dalby K. N., The molecular mechanism of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 23901–23916 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swulius M. T., Waxham M. N., Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 2637–2657 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proud C. G., Regulation and roles of elongation factor 2 kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43, 328–332 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie J., Mikolajek H., Pigott C. R., Hooper K. J., Mellows T., Moore C. E., Mohammed H., Werner J. M., Thomas G. J., Proud C. G., Molecular mechanism for the control of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase by pH: Role in cancer cell survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35, 1805–1824 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pigott C. R., Mikolajek H., Moore C. E., Finn S. J., Phippen C. W., Werner J. M., Proud C. G., Insights into the regulation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and the interplay between its domains. Biochem. J. 442, 105–118 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Will N., Lee K., Hajredini F., Giles D. H., Abzalimov R. R., Clarkson M., Dalby K. N., Ghose R., Structural dynamics of the activation of elongation factor 2 kinase by Ca2+-calmodulin. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 2802–2821 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight J. R. P., Garland G., Pö yry T., Mead E., Vlahov N., Sfakianos A., Grosso S., De-Lima-Hedayioglu F., Mallucci G. R., von der Haar T., Smales C. M., Sansom O. J., Willis A. E., Control of translation elongation in health and disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 13, dmm043208 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye Q., Crawley S. W., Yang Y., Côté G. P., Jia Z., Crystal structure of the α-kinase domain of Dictyostelium myosin heavy chain kinase A. Sci. Signal. 3, ra17 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ye Q., Yang Y., van Staalduinen L., Crawley S. W., Liu L., Brennan S., Côté G. P., Jia Z., Structure of the Dictyostelium myosin-II heavy chain kinase A (MHCK-A) α-kinase domain apoenzyme reveals a novel autoinhibited conformation. Sci. Rep. 6, 26634 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamaguchi H., Matsushita M., Nairn A. C., Kuriyan J., Crystal structure of the atypical protein kinase domain of a Trp channel with phosphotransferase activity. Mol. Cell 7, 1047–1057 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fawaz M. V., Topper M. E., Firestine S. M., The ATP-grasp enzymes. Bioorg. Chem. 39, 185–191 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piserchio A., Will N., Giles D. H., Hajredini F., Dalby K. N., Ghose R., Solution structure of the carboxy-terminal tandem repeat domain of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and its role in substrate recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 2700–2717 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mittl P. R. E., Schneider-Brachert W., Sel1-like repeat proteins in signal transduction. Cell. Signal. 19, 20–31 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iyer A. H., Krishna Deepak R. N. V., Sankararamakrishnan R., Imidazole nitrogens of two histidine residues participating in N-H⋯N hydrogen bonds in protein structures: Structural bioinformatics approach combined with quantum chemical calculations. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 1205–1212 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piserchio A., Long K., Lee K., Kumar E. A., Abzalimov R., Dalby K. N., Ghose R., Structural dynamics of the complex of calmodulin with a minimal functional construct of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and the role of Thr348 autophosphorylation. Protein Sci. 30, 1221–1234 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee K., Alphonse S., Piserchio A., Tavares C. D. J., Giles D. H., Wellmann R. M., Dalby K. N., Ghose R., Structural basis for the recognition of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase by calmodulin. Structure 24, 1441–1451 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kortemme T., Kim D. E., Baker D., Computational alanine scanning of protein-protein interfaces. Sci. STKE 2004, pl2 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Senguen F. T., Grabarek Z., X-ray structures of magnesium and manganese complexes with the N-terminal domain of calmodulin: Insights into the mechanism and specificity of metal ion binding to an EF-hand. Biochemistry 51, 6182–6194 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Romani A., Regulation of magnesium homeostasis and transport in mammalian cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 458, 90–102 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandez-Sanz C., De la Fuente S., Sheu S.-S., Mitochondrial Ca2+ concentrations in live cells: Quantification methods and discrepancies. FEBS Lett. 593, 1528–1541 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee K., Kumar E. A., Dalby K. N., Ghose R., The role of calcium in the interaction between calmodulin and a minimal functional construct of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase. Protein Sci. 28, 2089–2098 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tavares C. D. J., Giles D. H., Stancu G., Chitjian C. A., Ferguson S. B., Wellmann R. M., Kaoud T. S., Ghose R., Dalby K. N., Signal integration at elongation factor 2 kinase: The roles of calcium, calmodulin, and Ser-500 phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 2032–2045 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore C. E., Mikolajek H., Regufe da Mota S., Wang X., Kenney J. W., Werner J. M., Proud C. G., Elongation factor 2 kinase is regulated by proline hydroxylation and protects cells during hypoxia. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35, 1788–1804 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kornev A. P., Taylor S. S., Ten Eyck L. F., A helix scaffold for the assembly of active protein kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 14377–14382 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore C. E., Regufe da Mota S., Mikolajek H., Proud C. G., A conserved loop in the catalytic domain of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase plays a key role in its substrate specificity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 2294–2307 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jencks W. P., On the attribution and additivity of binding energies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 78, 4046–4050 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Devkota A. K., Warthaka M., Edupuganti R., Tavares C. D. J., Johnson W. H., Ozpolat B., Cho E. J., Dalby K. N., High-throughput screens for eEF-2 kinase. J. Biomol. Scr. 19, 445–452 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCarthy M. R., Savich Y., Cornea R. L., Thomas D. D., Resolved structural states of calmodulin in regulation of skeletal muscle calcium release. Biophys. J. 118, 1090–1100 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong D., Chi X., Wei J., Zhou G., Huang G., Zhang L., Wang R., Lei J., Chen S. R. W., Yan N., Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor 2 by calmodulin. Nature 572, 347–351 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pandey K., Dhoke R. R., Rathore Y. S., Nath S. K., Verma N., Bawa S., Ashish, Low ph overrides the need of calcium ions for the shape-function relationship of calmodulin: Resolving prevailing debates. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 5059–5074 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tavares C. D. J., O’Brien J. P., Abramczyk O., Devkota A. K., Shores K. S., Ferguson S. B., Kaoud T. S., Warthaka M., Marshall K. D., Keller K. M., Zhang Y., Brodbelt J. S., Ozpolat B., Dalby K. N., Calcium/calmodulin stimulates the autophosphorylation of elongation factor 2 kinase on Thr-348 and Ser-500 to regulate its activity and calcium dependence. Biochemistry 51, 2232–2245 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Redpath N. T., Proud C. G., Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates rabbit reticulocyte elongation factor-2 kinase and induces calcium-independent activity. Biochem. J. 293, 31–34 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X., Li W., Williams M., Terada N., Alessi D. R., Proud C. G., Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90rsk1 and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J. 20, 4370–4379 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vonrhein C., Flensburg C., Keller P., Sharff A., Smart O., Paciorek W., Womack T., Bricogne G., Data processing and analysis with the autoproc toolbox. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67, 293–302 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Terwilliger T. C., Dimaio F., Read R. J., Baker D., Bunkóczi G., Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Afonine P. V., Echols N., Phenix.Mr_rosetta: Molecular replacement and model rebuilding with Phenix and Rosetta. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 13, 81–90 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hildebrand A., Remmert M., Biegert A., Söding J., Fast and accurate automatic structure prediction with HHpred. Proteins 77, 128–132 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zwart P. H., Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L.-W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., McKee E., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Storoni L. C., Terwilliger T. C., Adams P. D., Automated structure solution with the PHENIX suite. Meth. Mol. Biol. 426, 419–435 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emsley P., Cowtan K., Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afonine P. V., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Echols N., Headd J. J., Moriarty N. W., Mustyakimov M., Terwilliger T. C., Urzhumtsev A., Zwart P. H., Adams P. D., Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 68, 352–367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joosten R. P., Long F., Murshudov G. N., Perrakis A., The PDB_REDO server for macromolecular structure model optimization. IUCrJ 1, 213–220 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holm L., Laakso L. M., Dali server update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W351–W355 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reynes C., Kister G., Rohmer M., Bouschet T., Varrault A., Dubois E., Rialle S., Journot L., Sabatier R., Isolde: A data-driven statistical method for the inference of allelic imbalance in datasets with reciprocal crosses. Bioinformatics 36, 504–513 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brzezinski D., Porebski P. J., Kowiel M., Macnar J. M., Minor W., Recognizing and validating ligands with checkmyblob. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W86–W92 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ashkenazy H., Abadi S., Martz E., Chay O., Mayrose I., Pupko T., Ben-Tal N., ConSurf 2016: An improved methodology to estimate and visualize evolutionary conservation in macromolecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W344–W350 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Suzek B. E., Wang Y., Huang H., McGarvey P. B., Wu C. H.; UniProt Consortium , UniRef clusters: A comprehensive and scalable alternative for improving sequence similarity searches. Bioinformatics 31, 926–932 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wistrand M., Sonnhammer E. L. L., Improved profile hmm performance by assessment of critical algorithmic features in sam and hmmer. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 99 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katoh K., Standley D. M., Mafft: Iterative refinement and additional methods. Meth. Mol. Biol. 1079, 131–146 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Meng E. C., Couch G. S., Croll T. I., Morris J. H., Ferrin T. E., UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pei J., Grishin N. V., AL2CO: Calculation of positional conservation in a protein sequence alignment. Bioinformatics 17, 700–712 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Amero C., Schanda P., Durá M. A., Ayala I., Marion D., Franzetti B., Brutscher B., Boisbouvier J., Fast two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of high molecular weight protein assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3448–3449 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A., NmrPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson B. A., From raw data to protein backbone chemical shifts using NMRFx processing and NMRviewJ analysis. Meth. Mol. Biol. 1688, 257–310 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Manalastas-Cantos K., Konarev P. V., Hajizadeh N. R., Kikhney A. G., Petoukhov M. V., Molodenskiy D. S., Panjkovich A., Mertens H. D. T., Gruzinov A., Borges C., Jeffries C. M., Svergun D. I., Franke D., ATSAS 3.0: Expanded functionality and new tools for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 54, 343–355 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Franke D., Svergun D. I., DAMMIF , a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 342–346 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Petoukhov M. V., Franke D., Shkumatov A. V., Tria G., Kikhney A. G., Gajda M., Gorba C., Mertens H. D. T., Konarev P. V., Svergun D. I., New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 45, 342–350 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Svergun D. I., Restoring low resolution structure of biological macromolecules from solution scattering using simulated annealing. Biophys. J. 76, 2879–2886 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Franke D., Petoukhov M. V., Konarev P. V., Panjkovich A., Tuukkanen A., Mertens H. D. T., Kikhney A. G., Hajizadeh N. R., Franklin J. M., Jeffries C. M., Svergun D. I., ATSAS 2.8: A comprehensive data analysis suite for small-angle scattering from macromolecular solutions. J. Appl. Cryst. 50, 1212–1225 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kozin M. B., Svergun D. I., Automated matching of high- and low-resolution structural models. J. Appl. Cryst. 34, 33–41 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 79.Devkota A. K., Kaoud T. S., Warthaka M., Dalby K. N., Fluorescent peptide assays for protein kinases. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 18, Unit 18.17 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S6