Abstract

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in urine is a promising analyte for noninvasive diagnostics. However, urine cfDNA is highly fragmented. Whether characteristics of these fragments reflect underlying genomic architecture is unknown. Here, we characterized fragmentation patterns in urine cfDNA using whole genome sequencing. Size distribution of urine cfDNA fragments showed multiple strong peaks between 40 bp and 120 bp with a modal size of 81 bp and sharp 10 bp periodicity, suggesting transient protection from complete degradation. These properties were robust to pre-analytical perturbations, such as at-home collection and delay in processing. Genome-wide sequencing coverage of urine cfDNA fragments revealed recurrently protected regions (RPRs) conserved across individuals, with partial overlap with nucleosome positioning maps inferred from plasma cfDNA. The ends of cfDNA fragments clustered upstream and downstream of RPRs, and nucleotide frequencies of fragment ends indicated enzymatic digestion of urine cfDNA. Compared to plasma, fragmentation patterns in urine cfDNA showed greater correlation with gene expression and chromatin accessibility in epithelial cells of the urinary tract. We determined that tumor-derived urine cfDNA exhibits a higher frequency of aberrant fragments that end within RPRs. By comparing the fraction of aberrant fragments and nucleotide frequencies of fragment ends, we identified urine samples from cancer patients with an area under the curve of 0.89. Our results revealed non-random genomic positioning of urine cfDNA fragments and suggested that analysis of fragmentation patterns across recurrently protected genomic loci may serve as a cancer diagnostic.

One Sentence Summary:

Fragmentation patterns of cell-free DNA from urine differ between healthy individuals and those with cancer.

Introduction

Circulating cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as an informative biomarker in pregnant women(1), patients who have undergone an organ transplant(2), and patients with cancer(3). The genome-wide distribution and fragmentation of cfDNA in plasma is not random. Plasma cfDNA fragments have a modal size of 167 bp, are protected from degradation within mononucleosomes, and the beginning and end of the fragments capture nucleosome footprints of contributing tissues(4). In patients with cancer, these observations potentially enable cancer detection(5), inference of tissue of origin(6) and inference of gene expression(7). In addition, deviations from expected fragment size and positioning can be leveraged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio for somatic genomic alterations in plasma cfDNA(8, 9).

Collection of blood plasma requires venipuncture, and the volume of plasma that can be collected at a single time point is limited. In contrast, urine can be collected noninvasively, outside of a clinical setting, without access to phlebotomists, and in larger volumes. However, there has been limited success in diagnostic development using urine cfDNA to date. There are multiple reports that cfDNA fragments are more degraded, shorter, and variably sized in urine compared to plasma(10, 11), impeding targeted analysis of genomic alterations. Comprehensive characterization of fragment sizes and positioning in urine cfDNA has not been reported and whether any genome-wide organization is preserved is unknown.

We characterized fragmentation patterns in urine cfDNA using whole genome sequencing (WGS). Urine samples from most individuals showed a consistent distribution of fragment sizes with a modal size of 80-81 bp, suggesting non-random cfDNA fragmentation in urine. Therefore, we investigated whether any genomic loci are recurrently and preferentially protected from complete degradation in urine cfDNA. We found a correlation between cfDNA fragmentation patterns in urine and chromatin accessibility, as well as gene expression, in contributing cells. In patients with cancer, we report a framework to leverage genome-wide differences in urine cfDNA fragmentation at recurrently protected genomic regions (RPRs) as a potential diagnostic approach.

Results

Fragment size distribution in urine cfDNA

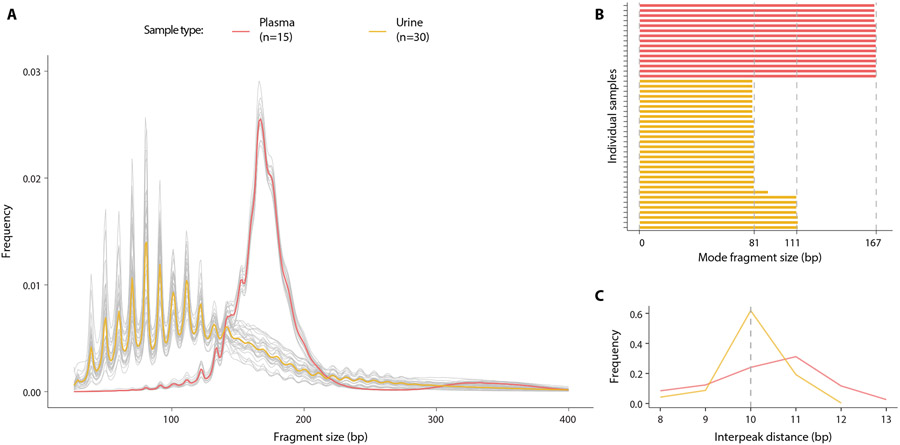

To investigate fragment size distribution of urine cfDNA with high resolution, we performed WGS of 30 urine and 15 plasma cfDNA samples collected from unrelated healthy individuals. We achieved a mean physical coverage of 7× for urine samples and 3.6× for plasma samples, and total pooled coverage of 196× for urine samples and 58× for plasma samples. In plasma cfDNA, we observed a modal fragment size of 167 bp, as reported previously(12) (Fig. 1A, fig. S1). In urine cfDNA, we found the modal fragment size in 23 out of 30 samples was 80 – 81 bp. In 6 of 30 samples, the modal fragment size was 111 – 112 bp (Fig. 1B, fig. S2). In both sample types, we found an approximately 10 bp step pattern, which was much more pronounced in urine cfDNA compared to plasma. Mean interpeak distances were 10.8 bp in plasma cfDNA and 9.9 bp in urine cfDNA (Fig. 1C). Although the size distribution of plasma cfDNA spread around one predominant 167 bp mode, fragment sizes in urine cfDNA had multiple sharp peaks between 40 bp and 120 bp that were evenly distributed relative to the 81 bp mode (Fig. 1A). This fragment size distribution is reminiscent of digestion products of nucleosomes(13) and suggests transient protection from complete degradation by association with histones. Consistent with this hypothesis of histone-associated protection, we detected all four nucleosomal histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4) and histone H1 in urine using mass spectrometry (table S1). In earlier in vitro studies, the most common fragment size (80 – 81 bp) that we observed in urine cfDNA was associated with the histone H32H42 tetramer, which is the most energetically favorable intermediate component during stepwise nucleosome disassembly(14). H32H42 tetramers bind the central ~67 bp region of the DNA wrapped within mono-nucleosomes and are key determinants of translational nucleosome positioning(14-16).

Fig. 1: Comparison of DNA fragment size between plasma and urine samples.

(A) Size distributions of genome-wide DNA fragments were measured in samples of plasma and urine. Grey lines show individual samples,the red line shows the mean in the plasma samples and the yellow line the mean in urine samples. (B) Modal size in individual plasma and urine samples was defined as the fragment size with the highest frequency. (C) Frequency of occurrence of interpeak (peak-to-peak) distance of periodic peaks in fragment size for plasma and urine samples was plotted.

Relationship between fragmentation patterns and nucleosome positioning in cells contributing cfDNA into urine and plasma

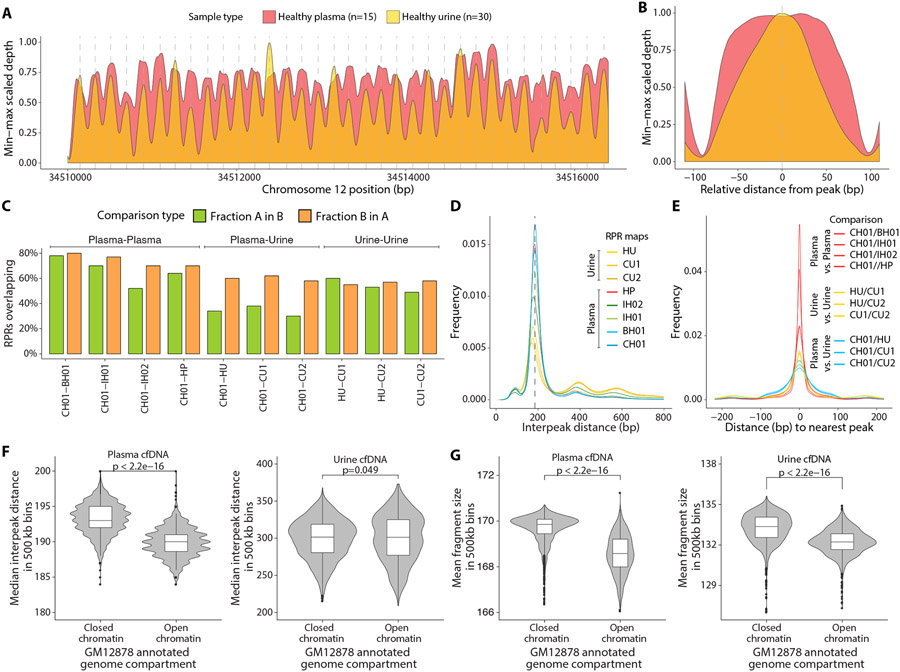

To evaluate whether the distribution of urine cfDNA fragments across the genome was random or if some genomic loci were recurrently protected from degradation, we compared physical sequencing coverage between plasma and urine cfDNA in a genomic region on chromosome 12, which has nucleosomes with conserved positions in multiple cell types(17). In both plasma and urine cfDNA, we found oscillations in coverage with overlapping peaks at identical positions (Fig. 2A, fig. S3). Individual peaks in urine cfDNA were narrower and occupied the center of corresponding peaks in plasma cfDNA (Fig. 2B). The average distance between consecutive peaks was 188 bp and 187 bp for plasma and urine samples, respectively.

Fig. 2: Relationship between sequencing coverage of cfDNA fragments in plasma and urine samples.

(A) LOESS smoothed and min-max scaled physical sequencing coverage of pooled plasma and urine samples in an ~ 6000 bp genomic region with stable nucleosomes (Chromosome 12p11.1). The vertical dashed grey lines depict the local maxima of each peak for the pooled urine samples. (B) Mean smoothed physical sequencing coverage calculated by centering all peaks at the local maxima. (C) Percentage of RPR calls overlapping in pairwise comparisons of genome-wide RPR maps. Each comparison is between two plasma maps (CH01-BH01, CH01-IH01, CH01-IH02, CH01-HP), two urine maps (HU-CU1, HU-CU2, CU1-CU2), or between a plasma and a urine map (CH01-HU, CH01-CU1, CH01-CU2). (D) Distribution of distances between adjacent peak centers (interpeak distance) in each RPR map. (E) Distribution of distances between nearest peaks in pairwise comparison of any two RPR maps. The distributions of distances between corresponding peak centers are shown. (F) Comparison of plasma and urine median interpeak distance in 500 kb bins annotated as closed chromatin regions or open chromatin regions from Hi-C chromatin contact map of a lymphoblastoid cell line (GM12878). (G) Comparison of plasma and urine mean fragment size in 500 kb bins annotated as closed or open chromatin regions.

To investigate whether such similarity between plasma and urine cfDNA exists across the genome, we generated genome-wide maps of recurrently protected regions (RPRs), defined as peaks in window protection scores (WPS). WPS was calculated as the ratio between number of fragments that end and those that span within a window of fixed size around each position in the genome(6). We generated four independent RPR maps using a single pool of plasma samples from healthy individuals (HP) and three independent pools of urine samples (healthy individuals HU, and two sets of patients with cancer CU1 and CU2). CU1 were samples from a cohort of patients with pediatric cancers; CU2 were samples from a cohort of patients with pancreatic cancer (table S2). We identified 11.8 million RPR peaks in HP, 7.2 million in HU, 7.9 million in CU1, and 6.7 million in CU2. We evaluated the HP map against previously published plasma-based RPR maps (CH01, IH01, IH02 and BH01)(6). Median RPR widths for plasma maps CH01 and HP were 37 bp and 36 bp, respectively, with interquartile ranges of 19 bp and 21 bp, respectively (fig. S4). In comparison, median RPR widths for urine maps HU, CU1, and CU2 were 47 bp, 44 bp, and 48 bp, respectively, with interquartile ranges of 43 bp, 38 bp, and 44 bp, respectively (fig. S4). Thus, median RPR widths were greater for urine samples compared to plasma samples, although distributions of RPR widths for both sample types showed a mode at 25 bp.

We also assessed the similarity between RPR maps by comparing the overlap in positions of RPR peaks between pairs of maps (Fig. 2C). We found that 70% of RPR peaks identified in HP overlapped with those in CH01, whereas 64% of RPR peaks in CH01 overlapped with those in HP. The range of overlap among the pairwise plasma map comparisons was 52% – 80%. When we compared the urine maps with each other, 49% – 60% peaks overlapped in pairwise comparisons. However, the overlap between plasma and urine maps was much lower. Only 30% – 38% of RPR peaks in plasma map CH01 overlapped with any of those in the urine maps, whereas 58% – 62% of urine map RPR positions overlapped with those in CH01. Non-overlapping peaks had significantly lower confidence scores (relative enrichment of sequencing coverage) compared to overlapping peaks (p<0.001; fig. S5)(6).

The modal distance between consecutive adjacent nucleosome peaks (periodicity) was similar in all plasma and urine maps (177 bp to 184 bp, respectively) (Fig. 2D). This distance is consistent with periodic nucleosome positioning, suggesting that, as previously described for plasma(6), a majority of RPRs are a result of protection from degradation by association with nucleosomes or their constituent histones. It is also likely that a subset of cfDNA fragments escape degradation by association with other DNA-bound proteins, such as transcription factors(18). When any two RPR maps were compared (plasma-plasma, urine-urine, or plasma-urine comparisons), the distance between the centers of corresponding nearest peaks was predominantly zero (Fig. 2E). However, the spread of nearest peak distances was narrowest for plasma-plasma comparisons, wider for urine-urine comparisons, and widest for plasma-urine comparisons (Fig. 2E). These differences between urine and plasma maps suggested a combination of two sources of variation. In urine-urine comparisons, lower overlap in RPR peaks and greater spread of distances between nearest peaks likely resulted from fewer and less precise RPR positions inferred from urine due to greater fragmentation of cfDNA in urine compared to plasma. In urine-plasma comparisons, the additional discordance in peak overlap and even greater spread of distances between nearest peaks may partially result from differences in nucleosome positions and transcription factor binding positions in the different cell types that predominantly contribute cfDNA found in plasma or urine.

To assess if fragmentation patterns in cfDNA are affected by genome-wide nucleosome positioning in contributing cells, we compared interpeak distances between consecutive adjacent RPR peaks and cfDNA fragment sizes within open and closed chromatin regions. We identified open and closed chromatin regions from a published dataset generated using Hi-C chromatin contact analysis of a lymphoblastoid cell line (GM12878)(19). We calculated median interpeak distances and mean fragment sizes across the genome in non-overlapping windows of 500 kb. The HP RPR map had shorter distances between adjacent peaks on average in open chromatin regions (median interpeak distance 190 bp) compared to the distances in closed chromatin regions (median interpeak distance 193 bp) (p < 2 × 10−16, Student’s t-test; Fig. 2F), consistent with previous results (20). Similarly, the HU RPR map had shorter distances between adjacent peaks on average in open chromatin region (median interpeak distance 301 bp) compared to the distances in closed chromatin regions (median interpeak distance 302 bp) (p=0.049, Student’s t-test; Fig. 2F). In addition, we found that on average across the genome, cfDNA fragments were more degraded and shorter in size in open chromatin regions compared to closed chromatin regions in both plasma (mean fragment size in 500 kb bins of 169 bp and 170 bp, respectively, p < 2 × 10−16, Student’s t-test; Fig. 2G) and urine samples (mean fragment size in 500 kb bins of 132 bp and 133 bp, respectively, p < 2 × 10−16, Student’s t-test; Fig. 2G). The difference in fragment size between open and closed chromatin regions was consistent when the data were evaluated using bin sizes of 50 kb, or 1000 kb, indicating that the shorter fragment size observed in open chromatin was not an artifact of the bin size used for the analysis(fig. S6).

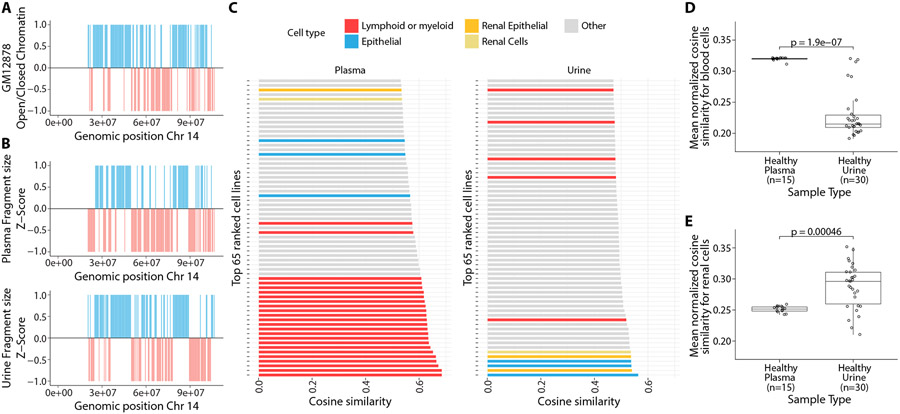

To explore whether cfDNA fragment sizes are associated with local differences in chromatin accessibility, we evaluated correlations between cfDNA fragment size and open or closed chromatin annotation. For each individual sample, we calculated a median fragment size within non-overlapping 500 kb windows for all autosomes and normalized all median values to z-scores. We compared these z-scores with the Hi-C annotated data from the lymphoblastoid cell line GM12878. Consistent with a previous study(21), we observed that genomic windows with negative fragment size z-scores (fragments shorter than the median fragment size) were associated with open chromatin regions and windows with positive fragment size z-scores (fragments longer than the median fragment size) were associated with closed chromatin regions (Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B). We performed cosine similarity analysis, which showed that this association was stronger for plasma samples than urine samples (cosine similarity of 0.53 and 0.37, respectively), consistent with lymphoblastoid origin of the reference cell line GM12878 and the higher contribution of cfDNA by hematopoietic cells into plasma(7).

Fig. 3: Comparison of cfDNA fragment size with chromatin accessibility across cell types.

(A) Distribution of open (red) and closed chromatin (blue) compartments in non-overlapping 500 kb bins on chromosome 14 from Hi-C chromatin contact map of a lymphoblastoid cell line (GM12878). (B) Distribution of median cfDNA fragment size in corresponding 500 kb bins, normalized to a z-score for pooled plasma samples (upper) and pooled urine samples(lower). Bins with negative and positive z-score values were transformed to −1 and 1 and colored red and blue, respectively. (C) 65 cell lines or tissues with highest cosine similarity between cfDNA fragment size and DHS sites in 500 kb bins across the genome. (D) Comparison of mean quantile normalized cosine similarity scores with blood cells [bone marrow, lymphoid, or myeloid cell lines (n = 24)] in individual plasma and urine samples. (E) Comparison of mean quantile normalized cosine similarity scores with renal tissues and renal epithelial cell lines (n=4 cell lines and tissues) in individual plasma and urine samples.

To evaluate whether other cell types show a stronger association with urine cfDNA than with plasma cfDNA, we used a published dataset of DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHS) across 116 cell lines and tissues(21-23). For each cell line or tissue, we calculated the number of DHS annotated in non-overlapping 500 kb windows for all autosomes. We normalized and transformed the data such that open chromatin regions with greater numbers of DHS will have a negative z-score and closed chromatin regions with fewer numbers of DHS will have a positive z-score. We calculated the cosine similarity between the fragment size z-score from each sample and the DHS z-score for each cell line or tissue. In open chromatin regions, we expected greater numbers of DHS and shorter cfDNA fragments, yielding positive cosine similarity between transformed z-scores. For pooled plasma cfDNA, we observed the highest cosine similarity with lymphoid or myeloid cells (Fig. 3C; fig. S7, top; data file S1). In contrast, for pooled urine cfDNA, we observed the highest cosine similarity with epithelial, renal epithelial, and renal cortical cells (Fig. 3C; fig. S7, bottom; data file S1). The mean quantile normalized cosine similarity for lymphoid or myeloid cells (n = 24) was higher in plasma samples compared to urine samples (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test; Fig. 3D). Conversely, the mean quantile normalized cosine similarity for renal cells (n = 4) was lower in plasma samples compared to urine samples (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test; Fig. 3E). These results suggested that renal and uroepithelial cells contribute a higher fraction of cfDNA in urine than in plasma. In urine samples, cell-type specific mean quantile normalized cosine similarity scores were more variable compared to those in plasma samples (Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E), suggesting that relative contributions of different cells or tissues may be more variable in urine.

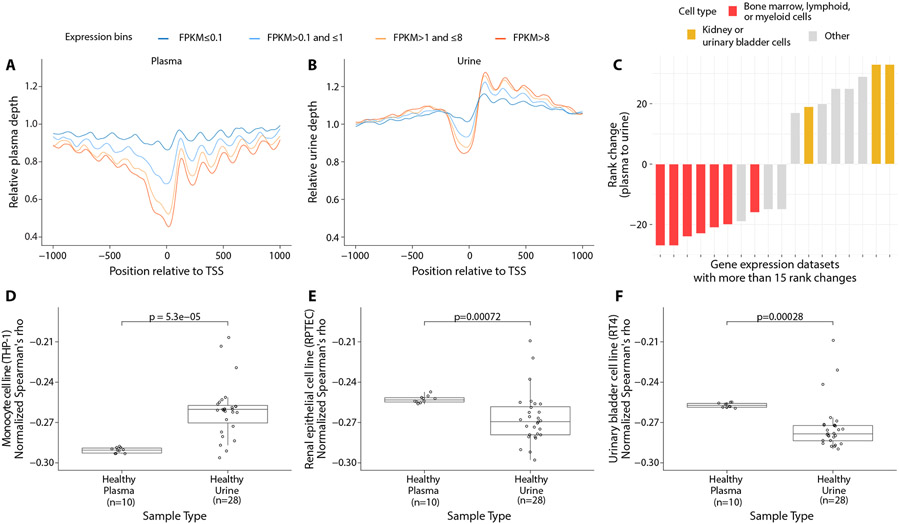

To evaluate tissue contributions using an additional alternative approach, we analyzed cfDNA sequencing coverage around transcription start sites (TSS) in urine and plasma. Sequencing coverage in plasma cfDNA is reduced at the nucleosome-depleted region (NDR) from ~150 bp upstream to ~50 bp downstream of TSS, and NDR depletion is associated with higher gene expression(7). We compared cfDNA sequencing coverage at the NDR region in plasma and urine samples with gene expression in plasma. We used gene expression values in plasma reported previously (7) and grouped genes into 4 expression levels based on fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). While plasma and urine cfDNA showed similar depletion at the NDR region, they were discordant in terms of overall cfDNA coverage in the 2 kb region around TSS (Fig. 4A, 4B). In plasma cfDNA, we confirmed the reported (7) depletion in overall cfDNA sequencing coverage in the highest expressed genes (Fig. 4A). However, in urine cfDNA, we found sequencing coverage in 2 kb region around the TSS was slightly higher than in surrounding loci and coverage was higher downstream of TSS than upstream, particularly for highly expressed genes (Fig. 4B). This difference in profile of relative sequencing coverage in the TSS region between urine and plasma cfDNA was also apparent when gene expression from bone marrow, kidney, a urinary bladder cell line, or a renal cortical cell line were used, indicating that it is unrelated to cell type used to measure gene expression (fig. S8). The coverage profile observed in urine cfDNA is similar to prior analyses of nucleosome occupancy around TSS based on DNA sequence content(24), suggesting that physiological conditions favoring nucleosome unfolding and digestion in urine may be driving this observation. Higher coverage downstream of TSS for genes with higher expression has also been observed following in vitro salt extraction of nuclease-treated chromatin, particularly at lower concentrations of salt(25).

Fig. 4: Comparison of cfDNA coverage at transcription start sites and correlation to gene expression across cell types.

(A-B) Mean pooled plasma and urine sequencing depth at the transcription start sites (TSS) of genes binned by their expression in fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). Gene expression amounts in plasma were used for this analysis. (C) Rank changes in correlation between sequencing coverage in the nucleosome-depleted region and gene expression across plasma and urine cfDNA. Cell lines whose ranks changed by at least 15 positions are shown here. (D-F) Comparison of mean quantile normalized Spearman's ρ for gene expression data from a monocyte cell line (D), renal epithelial cell line (E), and urinary bladder cell line (F) in individual plasma and urine samples.

To infer tissue of origin for cfDNA, we evaluated the genome-wide correlation between NDR sequencing coverage in plasma and urine cfDNA and gene expression in 101 human cell lines and primary tissues in the Human Protein Atlas(26). For each plasma or urine sample, we measured coverage at the NDR, from −150 bp to +50 bp around TSS of protein-coding genes on autosomes. We calculated Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (Spearman's ρ) between mean NDR coverage for each plasma or urine sample individually and the gene expression values in each cell line or tissue (data file S2). For plasma samples, the three strongest correlations were observed with lymphoblast cell lines (fig. S9A). In contrast, for the urine samples, the three most strongly correlated cell lines included two epithelial cell lines (kidney and endometrial) and a lymphoblast cell line (fig. S9B). To highlight key differences between the two sample types, we evaluated the change in the rank of cell lines and tissues between plasma and urine analyses (fig. S10, data file S3). The two largest decreases in rank (27 positions) when comparing plasma to urine were observed for a cell line of monocyte origin (THP-1) and for bone marrow tissue, consistent with lower contribution of these in urine compared to plasma (Fig. 4C, fig. S10). The largest increases in rank (33 positions) were observed for two cell lines of urinary bladder (RT4) and renal cortical origin (RPTEC) (Fig. 4C, fig. S10), consistent with higher contribution of these in urine compared to plasma.

To confirm the statistical significance of these changes in rank, we calculated the mean quantile normalized Spearman’s ρ for gene expression in THP-1, RPTEC, and RT4 cells and cfDNA sequencing coverage at NDR in plasma and urine samples. As expected, the cell line of monocyte origin (THP-1) had a lower value in plasma than in urine samples (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test; Fig. 4D). Conversely, RPTEC and RT4 had lower values in urine than in plasma samples (both p < 0.001, Student’s t-test; Fig. 4E, Fig. 4F). These results are consistent with the results of the cosine similarity analysis of fragment size and DHS sites in which RPTEC ranked 6/116 for urine cfDNA and 61/116 for plasma cfDNA (Fig. 3C, data file S1).

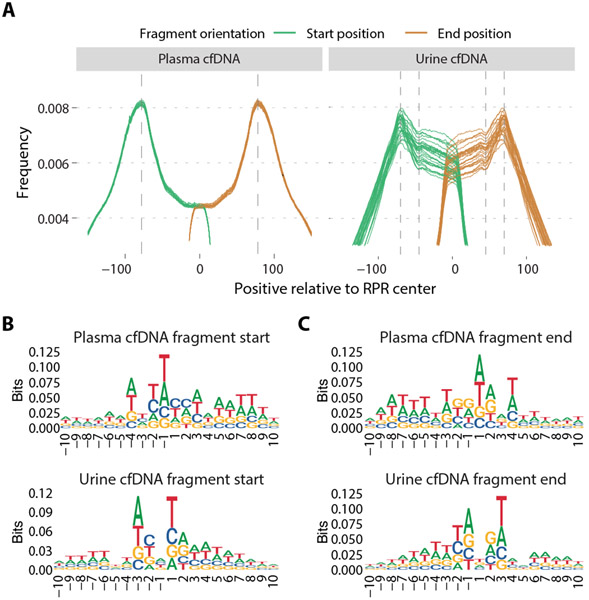

Positioning and sequence content of cfDNA fragment ends

If RPR maps inferred from cfDNA are representative of how most fragments are protected from degradation in plasma or urine, a higher frequency of fragment ends is expected at the periphery of corresponding RPR regions compared to the center. This pattern was observed for both plasma and urine cfDNA samples (Fig. 5A). When compared with a published plasma RPR map (CH01), the distribution of fragment start and end site distances in plasma cfDNA samples showed distinct modes at 77 bp upstream and downstream of the RPR peaks and reduced representation within the RPR center. When urine cfDNA samples were compared to the HU RPR map, we found the distribution of fragment start and end sites showed modes at 70 bp on either side of the center. Frequency of fragment ends was lower within the RPR center, although this was less pronounced in urine cfDNA than in plasma cfDNA. We observed a change in slope of the distribution of urine cfDNA fragment ends at 45 bp on either side of the center. These observations suggested that cfDNA fragments with aberrant ends within RPRs are more commonly observed in urine cfDNA than in plasma cfDNA, consistent with shorter fragment sizes observed in urine cfDNA and likely due to on-going degradation and only transient protection of urine cfDNA by association with histones and other proteins.

Fig. 5: Characterization of cfDNA fragment end sites.

(A) Genome-wide distribution of fragment start and end sites of individual plasma and urine samples relative to RPR centers. Comparison was made with a plasma-based RPR map (CH01) for plasma cfDNA samples and a urine-based RPR map (HU) for urine cfDNA samples. The vertical lines are drawn at 77 bp downstream and upstream from the RPR center for the plasma cfDNA distribution and at 70 bp and 45 bp downstream and upstream from the RPR center for the urine cfDNA distribution. (B-C) Nucleotide frequencies surrounding 10 bp upstream and downstream of fragment start positions (B) and end positions (C) in pooled plasma and urine cfDNA samples. Position 1 corresponds to the first base of the fragment in (B) and position −1 corresponds to the last base of the fragment in (C).

We also compared nucleotide frequencies observed at cfDNA fragment ends between urine and plasma samples. As previously reported (27), we found a consistent pattern of nucleotide frequencies across 10-bp regions upstream and downstream of fragment start and end sites in plasma cfDNA, and these were conserved across plasma samples (Fig. 5B, 5C; fig. S11, fig. S12). In urine cfDNA, we found a different pattern from plasma and this pattern was conserved across urine samples (Fig. 5B, 5C; fig. S13, fig. S14). To evaluate whether these sequence preferences vary for different fragment lengths, we divided fragments into bins by fragment size (with 10 bp increments, such as 65 bp to 74 bp, 75 bp to 84 bp, and so on)(28). In both plasma and urine cfDNA, these patterns were conserved regardless of fragment size (fig. S15). These observations indicated that different enzymes were responsible for DNA degradation in plasma and urine. DNase1-like3 is the predominant enzyme degrading chromatin in plasma(29). In contrast, DNase1, an enzyme highly active in urine(30), has preferential activity for naked DNA after DNA-bound proteins are removed(31). Indeed, DNA fragment ends resulting from DNase1-like3 digestion show a strong preference for cytosine (C) as the first base (+1 position of the fragment start)(32), which is consistent with our observations in plasma cfDNA (Fig. 5B, upper). In contrast, DNA fragment ends resulting from DNase1 digestion showed strong preference for thymine (T) as the first base (32), which we observed in urine cfDNA (Fig. 5B, lower).

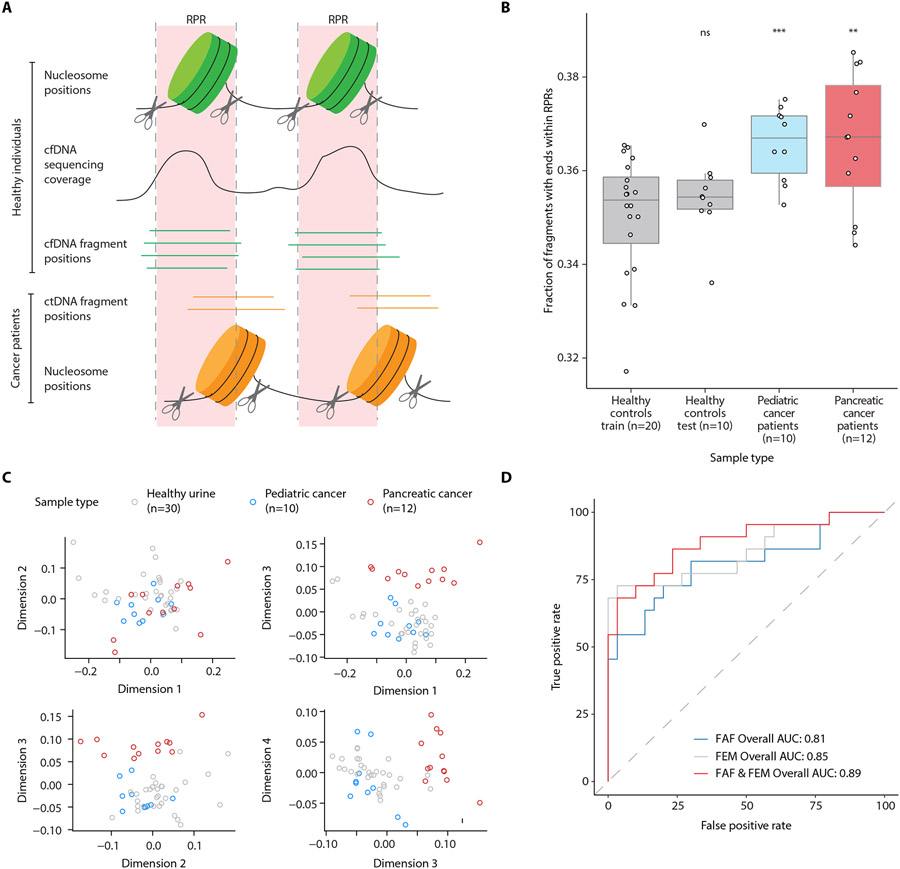

Aberrant cfDNA fragments at recurrently protected genomic loci in urine samples from patients with cancer

Our observations thus far suggested that the genome-wide distribution of urine cfDNA fragments was associated with a set of protected genomic regions that are conserved across individuals. Cancer cells are likely to have differences in nucleosome positioning and transcription factor binding compared to the cells and tissues that routinely contribute cfDNA into urine in healthy individuals. Therefore, we hypothesized that cancer-derived cfDNA fragments in urine may deviate from expectations set by inferred RPR maps at a higher rate (Fig. 6A). To test this hypothesis, we performed WGS on urine samples from 10 patients with nonmetastatic pediatric solid cancers (mean physical coverage of 21.6×) and 12 patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma including 7 patients with stage I-II and 5 patients with stage IV disease (mean physical coverage of 0.72×) (table S2). Samples were collected before the patients received any cancer treatment. Urine cfDNA fragment size distribution from the patients with cancer (fig. S16) was consistent with that observed in healthy individuals (fig. S2): Both had samples with modes of 80 – 81 bp or of 111 – 112 bp. One urine sample from a patient with pancreatic cancer had a mode of 123 bp.

Fig. 6: Evaluation of aberrant cfDNA fragments in urine from patients with cancer.

(A) Schematic representation of aberrant cfDNA fragments within RPR regions in urine samples from patients with cancer. In healthy individuals, fragment start and end positions flank regions protected by nucleosomes and are clustered away from RPRs. In patients with cancer, differences in nucleosome positioning and transcription factor binding in cancer cells that contribute cfDNA into urine may lead to a higher abundance of fragment start and end sites within RPRs. (B) Fraction of urine cfDNA reads starting or ending within RPRs (up to a maximum distance of 65 bp from the RPR center) inferred from pooled urine cfDNA data from 20 controls (training set). The fractions from the training set are compared to urine samples from 10 additional controls (test set), 10 patients with pediatric cancer, and 12 patients with pancreatic cancer. Statistical differences were determined by t test (ns, p > 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). (C) Multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis of nucleotide frequencies in 10 bp region surrounding urine cfDNA fragment start and end sites. (D) ROC analysis for classifying urine samples from controls and patients with cancer using fraction of aberrant fragments (FAF), fragment end motifs (FEM), or both. For FEM and for the combination of FAF and FEM, probabilities from a logistic regression fit to the first 4 MDS dimensions and FAF was used for ROC analysis.

To determine if there is a cancer-associated difference in the amount of cfDNA fragments with ends within RPRs, which we defined as “aberrant fragments,” we had to first define the fraction of aberrant fragments (FAF) in urine samples from healthy individuals. A background amount of aberrant fragments was expected in control urine samples, due to a higher abundance of shorter fragments that we found in urine cfDNA samples (Fig. 1A) and the variability that we detected in the contributing tissue types across healthy individuals (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Thus, we built a reference RPR map using pooled data from 20 of the 30 urine samples from healthy individuals. The data from these 20 samples served as the training set and had a pooled physical coverage of 155×. Against this map, we calculated FAF in the training set and the test set, which was comprised of the remaining 10 control samples that were not in the training set. The training set mean FAF was 35.0%; the test set mean FAF was 35.4%. These FAF values were not significantly different (p=0.31, Student’s t-test), indicating that our reference map captured the RPR variation among healthy individuals. In contrast and consistent with our hypothesis, we found significantly higher FAF values for both sets of patients with cancer compared to the training set (mean FAF 36.6% for each of the two sets, p < 0.01, Student’s t-test; Fig. 6B, data file S4). Furthermore, these higher FAF values in the samples from patients with cancer were also observed using multiple maximum distances from the center of the RPR (fig. S17), indicating that this finding was not related to the specific distance parameter selected.

To evaluate whether differences in chromatin accessibility and associated fragmentation sites in cancer cells also resulted in deviations in nucleotide frequencies at fragment ends, we analyzed the nucleotide frequencies in the 10 bp region upstream and downstream of fragment start and end sites. There were no obvious differences between urine samples from patients with cancer (fig. S18, fig. S19) and controls (fig. S13, fig. S14) in patterns of nucleotide frequencies seen at fragment ends. However, multidimensional scaling showed separation between healthy individuals and patients with pancreatic cancer in the third dimension (Fig. 6C). Using thresholds for FAF and for multiple dimensions of nucleotide frequency at fragment ends (FEM), we evaluated the ability to distinguish urine samples from patients with cancer, using all patients combined and evaluating each set separately. Using either feature individually or a combination of the two, we distinguished patients with cancer (combination of pediatric and pancreatic cancer patients) from healthy individuals, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values of 0.81 for FAF alone, 0.85 for FEM alone, and 0.89 for the combination (Fig. 6D). When analyzed as separate cancer populations, the analysis achieved AUC values of 0.92 for pediatric cancer patients when using the FAF and FEM combination (fig. S20A) and 1.0 for patients with pancreatic cancer with FEM alone (fig. S20B).

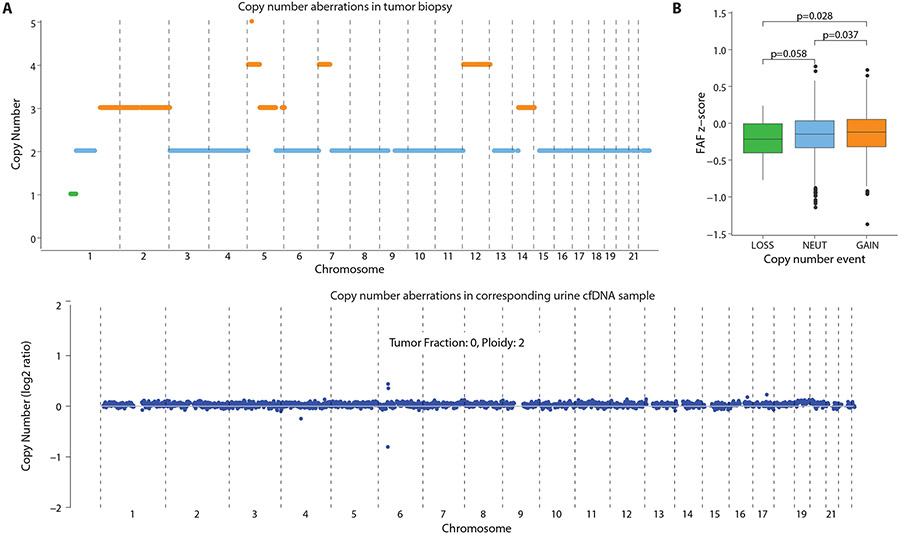

If tumor tissue is a source of cfDNA, the corresponding genomic abnormalities found in the tumor might be detected in the urine cfDNA, depending on the amount of cfDNA in urine that was contributed by the tumor. Thus, we compared copy number variations— gain, loss, or unchanged (neutral)— between 6 tumor biopsies and cfDNA in the matched urine sample. In all 6 cases, we detected no copy number aberrations in the matched urine cfDNA samples, and no detectable tumor fraction was observed using a published method for copy number analysis(33) (Fig. 7A, fig. S21A-S25A), indicating that the contribution of the tumor to the cfDNA in urine was below the limits of detection by those methods. In patients whose tumors are affected by copy number variations, the contribution of tumor tissue to cfDNA in urine is expected to result in higher FAF in genomic regions with gains in copy number, because the amount of tumor DNA contributed into urine by those regions would be greater. Thus, we compared FAF in genomic regions with gains, losses, or neutral changes in copy number. In 4/6 patients, we observed that FAF was higher for genomic regions with copy number gains in tumor, compared to the FAF in neutral or loss regions (one-tailed p < 0.05, Student’s t-test; Fig. 7B; fig. S21B, fig. S22B, fig. S23B). In one patient, no significant difference was observed (one-tailed p = 0.079, Student’s t-test; fig. S24B). In another patient, this analysis was uninformative because the tumor genome of this patient showed widespread copy number changes with no clear baseline copy number neutral region, likely due to technical artefacts during tumor exome analysis (fig. S25B). These results suggest that higher FAF values observed in urine samples from cancer patients are driven, at least in part, by cfDNA contributed by the tumor tissue.

Fig. 7: Comparison of fraction of aberrant fragments in urine cfDNA with copy number aberrations in the tumor and urine.

(A) Copy number aberrations observed in a patient with rhabdomyosarcoma. Upper graph shows DNA from the tumor biopsy with copy number gain indicated in orange, no change in blue, and loss in green. Lower graph shows the urine cfDNA sample analyzed by read density analysis with DNA from the tumor below the limit of detection. (B) FAF in a corresponding urine sample with copy number gain, no change (NEUT), and loss regions. Statistical differences were determined by one-tailed t test.

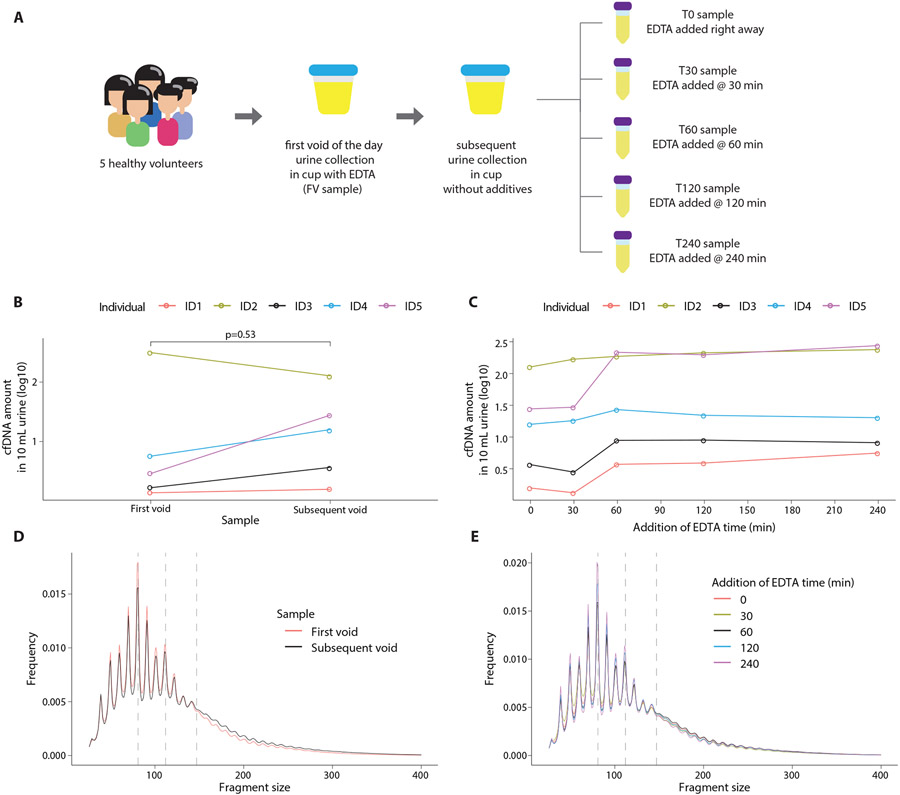

Pre-analytical variation in urine cfDNA fragmentation patterns

To evaluate the extent to which our results may be affected by pre-analytical variation, such as time of voiding or sample processing artefacts, we compared the cfDNA yield and fragmentation profile across 30 urine samples obtained from 5 healthy individuals (3 male and 2 female) (Fig. 8A). Each individual provided a first void of the day sample that was collected at home in a urine cup with EDTA additive (FV sample). Self-reported time since last void for the FV sample was 4.5 to 8.6 hours (mean 7.1 hours). No further processing was performed until the sample arrived in our research lab (a delay of 2.6 to 5.7 hours, mean 3.7 hours). Each individual also provided a second sample on site in a urine cup without any additive, and this was divided into 5 aliquots. Self-reported time since last void for the second sample was 1.3 to 6.0 hours (mean 4.2 hours), significantly shorter than FV (paired t-test two-tailed p = 0.007). EDTA was added after collection to the first aliquot within 13 to 23 mins (mean 16 mins, T0 sample) and in the remaining aliquots at 30 mins (T30), 60 mins (T60), 120 mins (T120), and 240 mins thereafter (T240) (Fig. 8A). We found no significant difference in total cfDNA yield between the first void and subsequent sample processed at T0 (p = 0.53, Student’s t test; Fig. 8B). The yield of cfDNA was stable for all individuals in T0 and T30 samples, but samples from 4/5 individuals showed an increase at T60 (Fig. 8C). The fragment size distributions obtained from the two independent urine samples (FV and T0) were indistinguishable (Fig. 8D). Similarly, fragment size distributions obtained from multiple processing timepoints of the second urine sample were completely overlapping (Fig. 8E, fig. S26). No significant differences were observed in pairwise comparisons of FAF between the FV sample and all other samples (paired t-test two-tailed p = 0.56, 0.77, 0.79, 0.96 and 0.84 for comparisons with T0, T30, T60, T120 and T240, respectively).

Fig. 8: Pre-analytical variation in urine cfDNA fragmentation patterns.

(A) Schematic representation of the experiment design. Paired urine samples were collected from 5 healthy individuals, including first void of the day and a subsequent sample. The subsequent sample was processed in 5 different aliquots with increasing delays in processing. (B) Comparison of cfDNA yield between the first void sample (FV) and the subsequent sample (T0). cfDNA yield was measured using fluorometry. (C) Comparison of cfDNA yield between 5 aliquots of the subsequent sample. cfDNA yield was measured using fluorometry.(D) Comparison of cfDNA fragment size distributions between first void (FV) and subsequent sample (T0). (E) Comparison of cfDNA fragment size distributions among 5 aliquots of the subsequent sample. In D and E, vertical dashed lines are placed at 81 bp, 112 bp, and 147 bp as visual guides.

Discussion

Urine is a promising source for cancer-derived cfDNA for diagnostic purposes and monitoring disease progression and therapeutic responses, but success using this approach has been limited because urine cfDNA is highly degraded(34). We found that fragment size distribution of urine cfDNA shows a recurrent mode at 80 – 81 bp, with multiple pronounced peaks separated by 10 bp steps, reminiscent of in vitro results of nucleosome degradation(13, 14) and suggesting transient protection of cfDNA fragments by association with histones or other proteins in urine. We observed genome-wide distribution of urine cfDNA fragments is non-random and reveals a set of genomic regions that are recurrently protected from degradation across independent urine samples. A comparison of genome-wide maps of recurrently protected regions (RPRs) inferred from cfDNA in urine and plasma samples had only partial overlap, suggesting potential differences in cells of origin. Using two independent approaches to infer cell types of origin, we found that uroepithelial cells contribute a higher fraction of cfDNA in urine compared to plasma. Taken together, these results showed a stable and reproducible genome-wide distribution of urine cfDNA fragments. They provide a potential framework for further development of diagnostics based on urine cfDNA without reliance on individual mutations or variant loci. In this study, we developed one such approach to detect tumor-derived DNA in urine from patients with cancer by measuring FAF (cfDNA fragment ends within RPRs) contributed by “unexpected” cell types, such as cancer cells, that are not present in urine cfDNA of healthy individuals.

In urine samples from two different cohorts of patients with cancer, we found increased FAF compared to background amounts in urine from healthy individuals, suggesting higher contribution of urine cfDNA from unexpected cell types. To evaluate whether this observation was driven specifically by DNA released from the tumor, we compared FAF from genomic loci with copy number changes in the tumor DNA samples in a subset of patients. We found that FAF were higher at genomic loci with copy number gains than at loci with neutral changes or those with copy number loss. Copy number changes were not directly observed in urine cfDNA in these patients, suggesting that measurement of FAF is more sensitive than current approaches for tumor DNA detection that rely on copy number analysis. The differences in FAF between patients with cancer and healthy individuals were small but highly significant (p < 0.01). This small difference is likely because 17/22 patients with cancer included in this study had nonmetastatic and potentially resectable disease with limited tumor burden. Using a combination of FAF and deviations in nucleotide frequencies in fragment ends, we achieved an area under the curve of 0.89 for distinguishing patients with cancer from healthy controls. These findings highlight the potential for genome-wide analysis of urine cfDNA fragmentation and positioning in improving cancer diagnostics, particularly for early detection of cancer.

In contrast to plasma, urine offers a truly noninvasive and high volume source of cancer-derived cfDNA. Our approach for cancer detection using urine cfDNA analysis is based on genome-wide fragmentation patterns. Interestingly, we found that cfDNA yields and fragment size distributions were unaffected by collection of urine samples at home in cups with pre-added EDTA and were robust to delays of approximately 45 minutes in sample processing after collection without any preservatives. However, urine is not under as stringent homeostatic regulation as plasma. We observed variation in the contribution of cfDNA from systemic and local tissues in urine samples, which may be explained by time elapsed since last void and duration that urine has incubated in the genitourinary system(10). Fragmentation pattern analysis lacks the inherent cancer specificity afforded by analysis of recurrent cancer-related somatic mutations, although interpretation of the latter can also be affected by pre-analytical variation(35). The cell types that contribute cfDNA and fragmentation patterns in urine can be affected by physiological states (differences in hydration status, pH, salt, or urea concentration), age, gender, co-morbidities, such as diabetes, and acute illnesses, such as urinary tract infections. To use relative differences in fragmentation patterns for cancer detection, reference RPR maps based on urine samples from large cohorts of controls will be required. Because changes in FAF are driven in part by differences in cell types that contribute cfDNA into urine, RPR analysis may be useful for monitoring patients with other conditions that alter the composition of urine cfDNA, such as organ transplant or pregnancy.

In this study, we observed the potential diagnostic value for urine cfDNA analysis across two different cohorts of patients with cancer. However, our study has limitations. The sample size of patients is limited. Larger studies are needed to better refine diagnostic thresholds and estimate performance across cancer subtypes and disease stages. We relied on urine samples obtained from patients with cancer at presentation and prior to treatment, when we expected tumor volume to be highest. Analysis of longitudinal samples obtained from patients with cancer during treatment can provide more insight into the value of our approach for treatment monitoring. Another limitation is that we did not record time of day, hydration status, time since last void or other sources of biological and pre-analytical variation during urine collection for most samples. Consistent with transient protection of cfDNA from complete degradation by association with histones, we detected histones in urine using mass spectrometry. However, we were unable to determine whether these histones are filtered into the urine from plasma or contributed locally by cells in the genitourinary tract. Future studies exploring quantitative relationships between cfDNA concentration and histone concentration may clarify this further. Moreover, it remains unclear whether the short cfDNA fragments observed in urine result from internal cleavage of intact nucleosomes or due to unravelling of nucleosomes into intermediate structures followed by DNA degradation. We further acknowledge the limitation that digested DNA fragments, such as those observed in urine cfDNA, are not ideal for reliable inference of nucleosome positioning. In our results, we found substantial overlap in RPR maps inferred from independent urine cfDNA samples. Although this approach may be adequate for measuring FAF in patients with cancer, it may not be reliable to accurately capture nucleosome positions in contributing cell types and to guide further functional analysis.

In summary, our findings support a stable distribution of cfDNA fragments across the genome in urine and set the stage for future investigation and development of urine-based diagnostic assays. We showed proof-of-principle results that genome-wide fragmentation patterns and positioning in urine cfDNA yield diagnostic value for patients with cancer. This approach can complement plasma-based liquid biopsy approaches for diagnosis and monitoring of cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The aim of this study was to investigate fragmentation patterns in urine and plasma cfDNA. Molecular and computational methods were developed retrospectively using urine and plasma samples from healthy volunteers. The potential clinical relevance of cfDNA fragmentation patterns observed in urine samples was evaluated retrospectively in two cohorts of prospectively enrolled patients with pancreatic cancer or pediatric cancers. Prior power analysis, randomization, or blinding was not performed for the clinical study.

Patients and samples

This study included healthy volunteers enrolled at Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, AZ, USA under an approved IRB protocol number 20142638, patients with pediatric cancer enrolled at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Phoenix, AZ, USA under an approved IRB protocol number 16-141, and patients with pancreatic cancer enrolled at Baylor Scott & White Research Institute under an approved IRB protocol number 015-196. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. For patients with cancer, urine samples were collected at presentation and prior to treatment. The analyzed tumor samples were obtained at the time of diagnosis.

Sample processing and cfDNA quantification in urine and plasma

Urine samples were processed within 1 hour of collection. We added 0.8 ml of 0.5 M EDTA to 40 ml of urine, centrifuged 10 ml aliquots at 1,600g for 10 min and stored at −80°C. We extracted cfDNA from 10 ml urine using MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and eluted in 20 – 30 μl. Blood samples were collected in K2 EDTA BD Vacutainer tubes and processed within 2 hours of collection. Blood samples were centrifuged at 820g for 10 min at room temperature. Aliquots (1 ml) of plasma were further centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 min to pellet any remaining cellular debris. The supernatant was stored at −80°C until DNA extraction. DNA was extracted using QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit (QIAGEN). We measured DNA yield using a digital PCR assay(36). In healthy individuals, median urine cfDNA concentration was 0.82 ng/ml of urine (interquartile range: 2.3 ng/ml, n = 30). Median plasma cfDNA concentration was 5.62 ng/ml of plasma (interquartile range: 4.75 ng/ml, n = 16).

Sequencing library preparation

For plasma cfDNA samples, we prepared WGS libraries using 1 ng input from healthy individual samples using ThruPLEX Tag-seq (Takara Bio). We performed sequencing on HiSeq 4000 (Illumina) to generate 75 bp paired-end reads. The library prep kit introduces a 6 bp unique molecular identifier and an 8 – 11 bp random stem on both ends of DNA fragments. These tags were removed using a custom Python script. For urine cfDNA samples, we prepared WGS libraries using 0.6 – 67.3 ng input using ThruPLEX Plasma-seq (Takara Bio). We performed sequencing on NovaSeq 6000 (Illumina) to generate 110 bp paired-end reads.

Sequencing data and fragment size analysis

We de-multiplexed sequencing data based on sample specific barcodes and converted to fastq files using Picard tools v2.2.1 for plasma data and using Illumina bcl2fastq v2.20.0.422 for urine data, allowing 1-bp mismatch and requiring minimum base quality of 20. We aligned sequencing reads to the human genome hg19 using bwa mem v0.7.15(37). We sorted and indexed the bam files using samtools v1.3.1(38). Reads with mapping quality < 30, unmapped reads, and supplementary alignments were excluded from downstream analysis. Fragment size distribution and genomic coverage was calculated using Picard tools. One plasma sample was dropped from further analysis due to low coverage (< 0.001× mean coverage). We calculated the modal fragment size and distance between fragment size peaks using a custom R script. We pooled plasma and urine controls by merging reads using samtools.

Comparison of sequencing coverage between urine and plasma cfDNA

In a region with strongly positioned nucleosomes independent of tissue type(17), we compared the physical coverage from pooled plasma and urine controls. For ease of visualization, we minmaxed (normalized data from 0 to 1) depth of coverage and applied a rough local polynomial regression fitting (LOESS) regression with a span of 0.02. Non-smoothed depth is shown in fig. S3. We calculated the mean smoothed physical coverage by centering all peaks in the region at their local maxima, estimated by inflection point.

Genome-wide identification of recurrently protected regions

We used published scripts based on window protection scores to create RPR maps using plasma and urine data(6). For plasma samples, we used similar parameters as previously published: minimum fragment size of 120 bp, maximum fragment size of 180 bp, and window of 120 bp. To accommodate the different fragment size distribution observed in urine cfDNA, we used the following parameters for urine samples: minimum fragment size of 64 bp, maximum fragment size of 196 bp, and window of 120 bp. To compare our plasma and urine maps with previously published RPR data, we calculated the fraction of RPR calls that overlapped between maps, the peak-to-peak distance between adjacent peaks (interpeak distance), and the distance to the nearest corresponding peaks. These analyses were carried out in R using the GenomicRanges package.

cfDNA fragmentation patterns in open and closed chromatin regions

We tiled all autosomes in the hg19 human genome into 500 kb non-overlapping bins. We excluded bins with mapability score < 0.9 and bins within or near the centromeric regions, resulting in 4,975 bins. We annotated each bin as transcriptionally active and enriched for open chromatin, or transcriptionally silent and enriched for closed chromatin based on annotations from a previously published Hi-C chromatin contact map of a lymphoblastoid cell line (GM12878)(20). We calculated median interpeak distance in each bin for the plasma and urine nucleosome maps using the GenomicRanges package. We calculated median fragment size in each bin using the Rsamtools package.

Comparison of local differences in cfDNA fragment size with chromatin accessibility

We calculated the median fragment size in each of the 500 kb bins and normalized the median values to a z-score (subtracting the median fragment size in each bin to the mean of the median fragment size in all bins and dividing by the standard deviation of the median fragment size in all bins). Bins with negative z-scores represent regions with higher fraction of shorter fragments, and bins with positive z-scores represent regions with higher fraction of longer fragments. We processed 116 published DHS datasets from different cell lines (22) in a similar manner. The DHS data and annotations were downloaded from https://resources.altius.org/publications/Science_Maurano_Humbert_et_al/. For each dataset, we calculated the number of DHS regions annotated in each 500 kb bin and normalized the counts to a z-score. For ease of interpretation and comparison with earlier analysis of Hi-C-annotated open and closed chromatin compartments, we transformed z-scores by multiplying with −1. Hence, bins with positive z-scores represent regions with closed chromatin regions and bins with negative z-scores represent regions with open chromatin regions. We calculated the cosine similarity between the z-score vector for individual and pooled cfDNA samples and the transformed z-score vector for all DHS datasets. The cosine similarity between two vectors A and B can be calculated as: A · B/∥ A ∥∥ B ∥. To evaluate individual plasma and urine samples, we quantile normalized the cosine similarity (R preprocessCore package) to maintain both cell line ranking and the continuous nature of the metric. We calculated the mean quantile normalized cosine similarity for all bone marrow, lymphoid, or myeloid cell lines (n = 24) and renal cell lines (n = 4) for individual cfDNA samples.

Comparison of cfDNA coverage at transcription start sites and correlation with gene expression

Paired-end reads were summarized as fragments with their 3’ and 5’ position into a bed file using BEDTools v2.26.0(39). We trimmed 61 – 800 bp fragments from both ends to contain 30-bp region downstream and upstream from the center (for odd fragment sizes, we rounded the decimal down to closest integer). We left fragments of 20 – 60 bp untrimmed. We converted the trimmed fragment bed files, back to bam files using bedtools. We calculated trimmed fragment coverage around the TSS of all genes in hg19 autosomes using the Rsamtools package. For each gene, we normalized the coverage in a window of TSS ± 1000 bp by mean depth in TSS − 3000 bp to TSS − 1001 bp, and TSS + 1001 bp to TSS + 3000 bp regions. We further corrected the normalized coverage by the coding strand direction. We averaged the strand corrected normalized coverage around the TSS ± 1000 bp window across genes with similar gene expression values, as published earlier(7). To infer tissue of origin using TSS coverage, we included samples with mean genomic coverage >3× (pooled plasma, pooled urine, and 10 plasma, and 28 urine samples that were evaluated individually). We calculated the raw read depth coverage −150 bp to +50 bp around the TSS, which represents the NDR, for all genes in hg19 autosomes and correlated them to their respective expression values from 64 human cell lines and 37 primary tissues, obtained from the Human Protein Atlas, using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (Spearman's ρ). We also assessed the change in rank between pooled plasma and urine samples. To see whether this trend was consistent in individual plasma and urine samples, we quantile normalized the Spearman's ρ (R preprocessCore package) for all 64 human cell lines and 37 primary tissues across all individual samples (10 plasma and 28 urine) to maintain both rank and the continuous nature of the metric. We calculated the mean quantile normalized Spearman's ρ for one monocyte-derived cell line (THP-1) and two renal cell lines (RPTEC and RT4) for individual samples.

Characterization of cfDNA fragment end sites

To investigate the distance of fragment start and end sites in urine and plasma relative to their nearest RPR centers, we used a plasma-based RPR map from CH01 (6) for comparison with plasma cfDNA and a urine-based RPR map from HU for comparison with urine cfDNA. Paired-end reads were summarized as fragments with their 3’ and 5’ position into a bed file using BEDTools v2.26.0(39). Further analysis was carried out in R using the GenomicRanges package. We intersected fragment positions with the RPR map. For any fragments that overlapped with an RPR peak, the distance of the fragment start position and end position from the center of their corresponding RPR peak was calculated. To avoid fragments that might span more than one RPR, only 50 – 200 bp fragments were used.

Using the fragment positions bed file, we created two additional bed files summarizing positions 10 bp upstream and downstream of fragment start and end sites, respectively. We extracted the genomic sequence of those regions using bedtools and calculated the mean per base mononucleotide frequencies using Homertools. We generated the start and end sequence motifs in R using the ggseqlogo package.

Aberrant fragmentation ends and fragment end nucleotide frequency in patients with cancer

We pooled reads from 20 healthy urine samples (12 females and 8 males) using samtools and built a urine-based reference RPR map using the same parameters described earlier for urine cfDNA. We intersected individual fragment bed files with the reference map using GenomicRanges package in R. For each overlap hit, the distance of fragment start and end positions from the center of the respective RPR hit was calculated. We calculated the fraction of fragments that started or ended within the inferred RPR region up to a maximum distance of 65 bp downstream or upstream of the RPR center. These were counted as aberrant fragments, because they are being digested within an RPR region that is relatively protected in the reference samples. We compared the FAF in 20 control urine samples used to generate the reference map with urine samples from another 10 controls, 10 patients with pediatric cancer, and 12 patients with pancreatic cancer. We calculated the predictive performance of FAF to distinguish between healthy and cancer samples using receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis (pROC R package). Because FAF values in training and test control samples were similar, we used all 30 controls samples in the ROC analysis. We conducted ROC analyses on pediatric and pancreatic cancer samples separately and in combination. Considering the RPR width distribution observed in urine-based RPR maps, a maximum distance of 65 bp from RPR center is expected to trim < 3% of RPRs with the greatest width (fig. S4).

Using the urine cfDNA fragment bed files from controls and patients with cancer, we created two additional bed files summarizing positions 10 bp upstream and downstream of fragment start and end sites, respectively. We extracted the genomic sequence of those regions using bedtools and calculated the mean per base mono- and di-nucleotide frequencies, as well as cumulative frequency of CpG, total G+C, total A+G, and total A+C using Homertools. For each individual sample, we summarized the various per base frequencies at fragment start and end sites in a single vector of length 168 in R. We concatenated the nucleotide frequency vector from all urine samples into one matrix (52 × 168). To reduce dimensions, we carried out multidimensional scaling to reduce the data to 4 dimensions (52 × 4). We visualized whether FEMs separated healthy samples from cancer samples by plotting various combinations of the 4 dimensions. To calculate the predictive performance of FEMs to distinguish between healthy and cancer samples we fitted logistic regression using base glm function in R to the 4 dimensions and used the predictive probability from the model to conduct ROC analysis. We conducted ROC analyses on pediatric and pancreatic cancer samples separately and in combination. We also combined the 4 dimensions and FAF and conducted an integrated ROC analysis.

Aberrant fragmentation ends in copy number alteration regions

To investigate whether the FAF was affected by underlying copy number changes in the tumor, we used data generated from exome sequencing of tumor and germline DNA samples from 2 patients with pediatric cancers and 4 patients with pancreatic cancer. We identified regions with copy number aberrations in tumor DNA using the R package Sequenza(40) and evaluated copy number aberrations in corresponding urine cfDNA using ichorCNA(33). For each of the 6 patients, we marked the 4975 bins as copy number neutral, loss, or gain based on tumor DNA analysis. We removed any bins that were partially segmented into two different copy number states. We calculated FAF in each of the filtered 500 kb bins for urine samples from 6 patients with cancer and 10 controls not used to build the urine RPR map. For each patient, we calculated the FAF ratio in bin i as the FAF in bin i of patient sample divided by the mean FAF in bin i of the 10 healthy urine samples, as shown in Equation 1.

| (1) |

We also calculated background distribution of FAF ratio for each bin using the 10 control urine samples, by picking one sample and calculating its FAF ratio using the mean FAF of the remaining 9 samples. An example for one healthy sample is shown in Equation 2. We repeated this for all 10 controls.

| (2) |

We then calculated the z-score of FAF ratio in bin i as the FAF ratio in bin i of a patient sample subtracted by the mean and divided by the standard deviation of background FAF ratio in bin i of the 10 healthy samples, as shown in Equation 3.

| (3) |

For each patient, we compared the distribution of FAF ratio z-scores in copy number neural, loss, and gain bins.

Urine histone analysis by mass spectrometry

Urea promotes the hydrolysis of urine proteins; therefore, we isolated proteins encapsulated in extracellular vesicles (EVs) from urine to increase protein coverage. We isolated EVs from 10 ml pooled commercially available normal human urine (Lee Biosolutions, Maryland Heights, MO) using the ExoEasy Maxi kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. The flow-through fraction (4 ml) was processed by trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation in 4:1 urine:acid ratio. Briefly, 1 ml of pre-chilled 100% TCA was added to 4 ml of urine flow-through, then samples were vortexed and chilled for 1 h on ice. The sample was then centrifuged at 11,000g for 30 min. After discarding the supernatant, pellets were first covered with 0.1% HCl in 100% ice-cold acetone, then centrifuged at 11,000g for 2 min. This step was repeated once with 100% ice-cold acetone. Pellets were then dried using nitrogen air flow and resuspended in 200 μl of 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate for bicinchoninic acid (BCA) quantification. Equimolar amounts of the captured EV fraction and the TCA precipitated flow-through fraction were then diluted 2× with solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 1× HALT (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) and lysed by sonication on a UTR200 cup sonicator (Hielscher Ultrasound Technology, Teltow, Germany). Lysed fractions were incubated with TCEP (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at a final concentration of 5 mM for 45 min at 60°C on thermoshaker at 450 rpm, followed by incubation with iodoacetemide (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) to final concentration of 10 mM for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Each fraction was then diluted three-fold with 50 mM Tris-HCl. Polypeptides were trypsin digested at a ratio of 1:50 (Promega) overnight at 37°C and subjected to solid phase extraction. Peptides in solution were dried by speed vacuum and reconstituted in 50 mM NH4OH and quantified by BCA (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Basic reverse phase fractionation was carried out on 8 μg of tryptic peptides using an XBridge BEH C18 column (130 Å, 3.5 μm particle size, 4.6 mm × 100 mm) (Waters, Milford, MA) connected to a U3000 UHPLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific) system operating at 0.3 ml/min flow-rate. Peptides were fraction-collected into a 96-deep well plate using a gradient of acetonitrile and water, and 10% aqueous 50 mM ammonium hydroxide (pH 10)(41). The resulting 96 fractions were concatenated into 6 analytical fractions, vacuum-dried, and reconstituted in 6 μl of aqueous 0.1% formic acid solution for LC-MS/MS analysis.

Mass spectrometry acquisition was performed in top-speed data-dependent mode (3 second duty cycle) on an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) mass spectrometer coupled to a nanoAcquity UPLC system (Waters). Peptides were separated on a PepMap RSLC C18 EasySpray C18 column (100 Å, 2 μm particle size, 75 μm × 25 cm) kept at 50°C with a 120 min gradient from 3% to 30% to 90% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid, at a flow-rate of 350 nl/min. The mass spectrometer was operated with the following parameters: ion transfer tube temperature of 275°C, spray voltage of 2400 V, MS1 in Orbitrap with a resolution of 120K and mass range of 400 – 1500 m/z, most abundant precursors (excluding undetermined and +1 charge state species) were selected for MS2 measurement in the ion trap following HCD fragmentation with 35% collision energy; dynamic exclusion was set to 60 s. Mass spectra were searched using Proteome Discoverer (v2.1.0.388, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Mascot (Matrix Science, Boston, MA) on a human UniprotKB (Swissprot, June 2017) database allowing for two missed cleavages, fixed cysteine carbamidomethylation, and variable methionine oxidation, a 10 ppm precursor and 0.6 Da fragment mass tolerance. Percolator was employed with a target-decoy strategy to determine false discovery rates at peptide and protein level(42).

Evaluation of preanalytical variability in urine cfDNA samples

Five healthy adults were enrolled at the Translational Genomics Research Institute, Phoenix, AZ, under IRB protocol number 20142638 approved by Western IRB. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. First void of the day urine sample was self-collected off-site in a sterile cup containing 0.5M EDTA for a minimum concentration of 10 mM. Urine from a subsequent void was collected on-site in a sterile cup without any additive. To process these samples, 10 ml aliquots were made from both samples. For the subsequent void sample, 0.2 ml of 0.5 M EDTA was added to an aliquot immediately. The remaining aliquots were stored at room temperature for 30, 60, 120, and 240 minutes prior to addition of EDTA and further processing. Aliquots were centrifuged at 1600g for 10 minutes at 4°C and the supernatant was stored at −80°C until extraction. cfDNA was extracted from 10 ml of urine with the MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to manufacturer instructions and eluted in 25 μl. Total DNA was quantified with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). Whole genome sequencing libraries were generated with 0.5 ng to 6.0 ng input according to manufacturer instructions using the SMARTer ThruPLEX Plasma-Seq kit (Takara). Sequencing was performed on Illumina NextSeq to generate 75 bp paired-end reads. Analysis of fragment size was performed as described above.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R. Differences between any two groups with normally distributed data were tested using t test. Correlation analyses were tested using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Any normalizations performed prior to statistical testing are noted above. P values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant and two-sided testing was used unless otherwise specified.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Fragment size distribution of cfDNA from individual healthy plasma samples.

Fig. S2. Fragment size distribution of cfDNA from individual healthy urine samples.

Fig. S3. Comparison of raw sequencing coverage between plasma and urine.

Fig. S4. Distribution of RPR widths across multiple genome-wide RPR maps.

Fig. S5. Comparison of overlapping and non-overlapping RPR call confidence scores.

Fig. S6. Comparison of fragment size in urine cfDNA between open and closed chromatin regions, using bins of 50 kb, 500 kb and 1000 kb.

Fig. S7. Cosine similarity between cfDNA fragment sizes and DHS sites.

Fig. S8. Mean pooled plasma and urine cfDNA sequencing depth at the transcription start sites (TSS) of genes grouped according to by their expression

Fig. S9. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients for cfDNA sequencing coverage at nucleosome depleted region (NDR) coverage and gene expression.

Fig. S10. Changes in rank based on the correlation between NDR coverage and gene expression between plasma and urine.

Fig. S11. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment start sites in plasma samples.

Fig. S12. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment end sites in plasma samples.

Fig. S13. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment start sites in urine samples.

Fig. S14. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment end sites in urine samples.

Fig. S15. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment start and end sites across fragment size bins in plasma and urine cfDNA.

Fig. S16. Fragment size distribution in individual urine samples from patients with cancer.

Fig. S17. Effect of changing maximum distance from RPR center on fraction of fragments with ends within RPRs in urine samples from healthy controls and patients with cancer.

Fig. S18. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment start sites in urine samples from patients with cancer.

Fig. S19. Nucleotide frequencies at fragment end sites in urine samples from patients with cancer.

Fig. S20. ROC analysis for classifying control and cancer samples by cancer type.

Fig. S21. Aberrant fragments across copy number changes in sample 36.

Fig. S22. Aberrant fragments across copy number changes in sample 37.

Fig. S23. Aberrant fragments across copy number changes in sample 34.

Fig. S24. Aberrant fragments across copy number changes in sample 43.

Fig. S25. Aberrant fragments across copy number changes in sample 33.

Fig. S26. Comparison of fragment size distributions between multiple urine samples collected from five healthy individuals.

Table S1. Histone proteins identified in urine using mass spectrometry.

Table S2. Clinical characteristics of patients with cancer.

Data file S3. Rank changes in Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients across pooled plasma and urine.

Data file S2. Quantile normalized Spearman's rank correlation coefficients between gene expression and NDR coverage.

Data file S1.Quantile normalized cosine similarity between DHS sites and cfDNA fragment size.

Data file S4. Fraction of aberrant fragments (FAF) and multidimensional scaled dimensions 1-4 of fragment end motifs (FEM) in urine samples.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank Callie Sinclair, Danielle Metz, and Stephanie Buchholtz at TGen, Lisa Keller at Phoenix Children’s Hospital, and the volunteers and patients who participated in this study. Editorial services were provided by Nancy R. Gough (BioSerendipity, LLC, Elkridge, MD)

Funding:

Supported by funding from Ben and Catherine Ivy Foundation to MM and SC, from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number 1U01CA243078-01A1 to MM and 1R01CA223481-01 to MM; from Science Foundation Arizona under award number BSP-0542-13 to MM, from Arizona Women’s Board to PP and MM; from Phoenix Children’s Hospital to JZ and PH; and from Baylor Scott and White Research Institute to SC, CB, AJ, and MM.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: HM, BRM, and MM are inventors on patent applications covering technologies described here including patent application number PCT/US20/41469, titled “Methods of detecting disease and treatment response in cfDNA”. MM consults for AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: Urine and plasma sequencing data from controls, and urine sequencing data and tumor/germline exome sequencing data from patients with pediatric cancer are available in dbGaP through dbGaP accession number phs002273.v1.p1. Tumor/germline sequencing data and urine sequencing data from patients with pancreatic cancer will be made available upon reasonable request to authors. All other data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References and Notes

- 1.Wong FC, Lo YM, Prenatal Diagnosis Innovation: Genome Sequencing of Maternal Plasma. Annu Rev Med 67, 419–432 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burnham P, Khush K, De Vlaminck I, Myriad Applications of Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Precision Organ Transplant Monitoring. Ann Am Thorac Soc 14, S237–S241 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan JCM, Massie C, Garcia-Corbacho J, Mouliere F, Brenton JD, Caldas C, Pacey S, Baird R, Rosenfeld N, Liquid biopsies come of age: towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat Rev Cancer 17, 223–238 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murtaza M, Caldas C, Nucleosome mapping in plasma DNA predicts cancer gene expression. Nat Genet 48, 1105–1106 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cristiano S, Leal A, Phallen J, Fiksel J, Adleff V, Bruhm DC, Jensen SO, Medina JE, Hruban C, White JR, Palsgrove DN, Niknafs N, Anagnostou V, Forde P, Naidoo J, Marrone K, Brahmer J, Woodward BD, Husain H, van Rooijen KL, Orntoft MW, Madsen AH, van de Velde CJH, Verheij M, Cats A, Punt CJA, Vink GR, van Grieken NCT, Koopman M, Fijneman RJA, Johansen JS, Nielsen HJ, Meijer GA, Andersen CL, Scharpf RB, Velculescu VE, Genome-wide cell-free DNA fragmentation in patients with cancer. Nature, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snyder MW, Kircher M, Hill AJ, Daza RM, Shendure J, Cell-free DNA Comprises an In Vivo Nucleosome Footprint that Informs Its Tissues-Of-Origin. Cell 164, 57–68 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulz P, Thallinger GG, Auer M, Graf R, Kashofer K, Jahn SW, Abete L, Pristauz G, Petru E, Geigl JB, Heitzer E, Speicher MR, Inferring expressed genes by whole-genome sequencing of plasma DNA. Nat Genet 48, 1273–1278 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mouliere F, Chandrananda D, Piskorz AM, Moore EK, Morris J, Ahlborn LB, Mair R, Goranova T, Marass F, Heider K, Wan JCM, Supernat A, Hudecova I, Gounaris I, Ros S, Jimenez-Linan M, Garcia-Corbacho J, Patel K, Ostrup O, Murphy S, Eldridge MD, Gale D, Stewart GD, Burge J, Cooper WN, van der Heijden MS, Massie CE, Watts C, Corrie P, Pacey S, Brindle KM, Baird RD, Mau-Sorensen M, Parkinson CA, Smith CG, Brenton JD, Rosenfeld N, Enhanced detection of circulating tumor DNA by fragment size analysis. Sci Transl Med 10, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marass F, Stephens D, Ptashkin R, Zehir A, Berger MF, Solit DB, Diaz LA, Tsui DWY, Fragment Size Analysis May Distinguish Clonal Hematopoiesis from Tumor-Derived Mutations in Cell-Free DNA. Clin Chem 66, 616–618 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng THT, Jiang P, Tam JCW, Sun X, Lee WS, Yu SCY, Teoh JYC, Chiu PKF, Ng CF, Chow KM, Szeto CC, Chan KCA, Chiu RWK, Lo YMD, Genomewide bisulfite sequencing reveals the origin and time-dependent fragmentation of urinary cfDNA. Clin Biochem 50, 496–501 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forshew T, Murtaza M, Parkinson C, Gale D, Tsui DW, Kaper F, Dawson SJ, Piskorz AM, Jimenez-Linan M, Bentley D, Hadfield J, May AP, Caldas C, Brenton JD, Rosenfeld N, Noninvasive identification and monitoring of cancer mutations by targeted deep sequencing of plasma DNA. Sci Transl Med 4, 136ra168 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lo YM, Chan KC, Sun H, Chen EZ, Jiang P, Lun FM, Zheng YW, Leung TY, Lau TK, Cantor CR, Chiu RW, Maternal plasma DNA sequencing reveals the genome-wide genetic and mutational profile of the fetus. Sci Transl Med 2, 61ra91 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitlock JP Jr., Rushizky GW, Simpson RT, DNase-sensitive sites in nucleosomes. Their relative suspectibilities depend on nuclease used. J Biol Chem 252, 3003–3006 (1977). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thastrom A, Bingham LM, Widom J, Nucleosomal locations of dominant DNA sequence motifs for histone-DNA interactions and nucleosome positioning. J Mol Biol 338, 695–709 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayes JJ, Clark DJ, Wolffe AP, Histone contributions to the structure of DNA in the nucleosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88, 6829–6833 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ, Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 389, 251–260 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaffney DJ, McVicker G, Pai AA, Fondufe-Mittendorf YN, Lewellen N, Michelini K, Widom J, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK, Controls of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. PLoS Genet 8, e1003036 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulz P, Perakis S, Zhou Q, Moser T, Belic J, Lazzeri I, Wolfler A, Zebisch A, Gerger A, Pristauz G, Petru E, White B, Roberts CES, John JS, Schimek MG, Geigl JB, Bauernhofer T, Sill H, Bock C, Heitzer E, Speicher MR, Inference of transcription factor binding from cell-free DNA enables tumor subtype prediction and early detection. Nat Commun 10, 4666 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, Sanborn AL, Machol I, Omer AD, Lander ES, Aiden EL, A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldi S, Krebs S, Blum H, Becker PB, Genome-wide measurement of local nucleosome array regularity and spacing by nanopore sequencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 894–901 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Liu T-Y, Weinberg DE, White BW, De La Torre CJ, Tan CL, Schmitt AD, Selvaraj S, Tran V, Laurent LC, Cabel L, Bidard F-C, Putcha G, Haque IS, Spatial co-fragmentation pattern of cell-free DNA recapitulates in vivo chromatin organization and identifies tissues-of-origin. bioRxiv, 564773 (2019). [Google Scholar]