Summary

Background

Universal access to safe, effective emergency care (EC) during the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated its centrality to healthcare systems. The ‘Leadership and Governance’ building block provides policy, accountability and stewardship to health systems, and is essential to determining effectiveness of pandemic response. This study aimed to explore the experience of leadership and governance during the COVID-19 pandemic from frontline clinicians and stakeholders across the Pacific region.

Methods

Australian and Pacific researchers collaborated to conduct this large, qualitative research project in three phases between March 2020 and July 2021. Data was gathered from 116 Pacific regional participants through online support forums, in-depth interviews and focus groups. A phenomenological approach shaped inductive and deductive data analysis, within a previously identified Pacific EC systems building block framework.

Findings

Politics profoundly influenced pandemic response effectiveness, even at the clinical coalface. Experienced clinicians spoke authoritatively to decision-makers; focusing on safety, quality and service duty. Rapid adaptability, past surge event experience, team-focus and systems-thinking enabled EC leadership. Transparent communication, collaboration, mutual respect and trust created unity between frontline clinicians and ‘top-level’ administrators. Pacific cultural assets of relationship-building and community cohesion strengthened responses.

Interpretation

Effective governance occurs when political, administrative and clinical actors work collaboratively in relationships characterised by trust, transparency, altruism and evidence. Trained, supported EC leadership will enhance frontline service provision, health security preparedness and future Universal Health Coverage goals.

Funding

Epidemic Ethics/World Health Organization (WHO), Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office/Wellcome Grant 214711/Z/18/Z. Co-funding: Australasian College for Emergency Medicine Foundation, International Development Fund Grant.

Keywords: COVID-19, Emergency care, Emergency medicine, Health leadership, Health governance, Health systems, Health system building blocks, Pacific Islands, Pacific region

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

‘Leadership and Governance’ is an established health system building block, comprising policies, accountability, stewardship and partnerships that intersect with and influence all other components of the health system. Governance and trust have been identified as crucial to resilient pandemic preparedness in Low- and Middle- Income Countries (LMICs), and decisive, collaborative leadership essential during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs), underdeveloped emergency care (EC) systems adapted rapidly in the early pandemic phase, despite several known leadership and governance building block gaps.

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, Ovid, WHO resources, Pacific and grey literature using search terms ‘emergency care’, ‘health systems’, ‘health system building blocks’, ‘leadership’, ‘governance’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘pandemic/surge event/disease outbreaks’ ‘Pacific Islands/region’ and related terms. We found application of the EC Systems building block framework to the Pacific context had identified several consensus standards and priorities for leadership and governance across PICTs, encompassing recognition of EC, staff support structures, legal protection, and policy oversight for collaboration and integration of EC with multisectoral stakeholders during surge events. Evidence is building for the critical role of responsive, respectful and trustworthy leadership and governance in the COVID-19 response in LMICs, but little is known about the experiences, insights and lessons from clinicians and stakeholders on the frontline in PICTs.

Added value of this study

This is the first study to critically and deeply explore the experience, insights and lessons of leadership and governance in the Pacific region from a predominantly EC clinical and related stakeholder perspective during the COVID-19 pandemic. We confirmed that political determinants of health shape pandemic responses and influence all components of EC systems in PICTs. Frontline health care workers’ (HCWs) engagement, motivation and goodwill was contingent on mutual trusting, respectful and collaborative relationships with political and administrative leaders. We found many leadership strengths of Pacific EC clinicians who used charisma, courage and past surge event experience to influence service provision, policy and planning for effective multi-sectoral COVID-19 responses. Clinicians also added authority, integrity and responsiveness to governance decisions by prioritising pandemic safety and quality issues.

Implications of all the available evidence

Transparent, trustworthy and collaborative leadership and governance is crucial to effective current and future pandemic responses. Engaged and respected EC leadership can strengthen governance to focus on quality, safety and integration of all health system components towards Universal Health Coverage. The Pacific regional COVID-19 experience can be an opportunity for transformative growth and trigger for PICTs to further act on the EC consensus roadmap for development.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Emergency care (EC) access and safety as an essential component of a health system is more important now than ever before. Surge health events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, conflicts and environmental catastrophes, have illuminated how essential pre-hospital and facility-based EC is to meeting Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of universality, inclusivity, safety and resilience.1 EC clinicians and stakeholders at the healthcare system frontline have unique experiences that connect community perspectives, service delivery challenges and policy implications for routine and surge event care, particularly over the last 18 months during the COVID-19 pandemic.2 In Low- and Middle-Income Country (LMIC) contexts, where EC systems are often the primary point of access to health care, we urgently need to learn from frontline stakeholders in order to maximise preparation and response for future health shocks.3,4

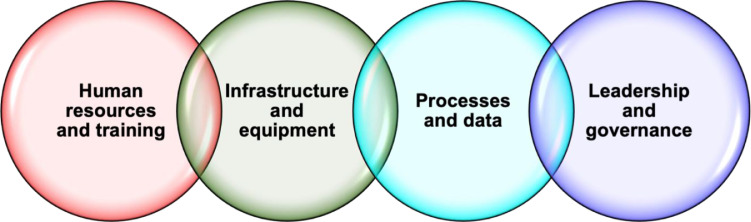

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines Leadership and Governance as a core building block within a health system; primarily focusing on government policy, oversight, regulation, accountability, stewardship and coalition-building.5,6 For EC systems in the Pacific region, this building block has been expanded to incorporate financing, and adapted to embrace all levels of leadership and governance from national to individual actors.7 Practical examples include laws ensuring universal access for emergency care, protecting first responders and multi-agency collaboration in disasters, clinical governance and accountability for EC quality and safety, and medical oversight of EC facility and pre-hospital function. Leadership and Governance intersects with and strengthens other EC system building blocks (Figure 1) and has been identified as a priority area for development in Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs).7

Figure 1.

WHO health system building blocks, adapted for the Pacific EC context and this qualitative research project.

Health governance manifests as law, policy and practice development, implementation, maintenance and accountability for all aspects of the health system. Inclusive and accountable styles of leadership and governance that build strong partnerships across multiple levels are essential to resilient health systems.8 Good health policy and planning arises from effective leadership that enhances team performance, quality and safety outcomes and organisational function,9 with physician participation recommended to drive health system reform.10 In the current COVID-19 pandemic, decisive leadership that uses evidence to respond rapidly and communicate clearly has become essential.11

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, leadership and governance for EC systems in the Pacific region was fragmented and limited. EC was not a government priority, and almost no PICT met regional consensus standards for integration of disaster plans with local EC systems, despite the critical importance of surge preparedness for expected environmental, climatic and disease outbreak events.7 At the individual level, however, young EC doctors were stepping into leadership roles in their home countries to advance EC systems and lead clinical care.12 Since March 2020, our research group have been collecting data from Pacific regional EC clinicians and stakeholders about their COVID-19 experience and insights as part of an extensive qualitative research project. The context and broader findings are reported in accompanying publications, but this paper explores the leadership and governance themes, enablers, barriers and lessons learnt in the pandemic response from frontline health care workers (HCWs) across the Pacific region.

Methods

Study design

The study methods are described in detail in another paper in this series.13 In brief, this study was conducted as a collaboration between Australian and PICT researchers, and employed prospective, qualitative research methods grounded in a phenomenological methodological approach.14,15

Data were collected from EC clinicians and other relevant stakeholders across PICTs in three phases between March 2020 and July 2021 (Table 1). Informed consent was obtained from research participants through a mixture of written and verbal consent. Semi-structured interview and discussion guides developed by the research team were used in Phases 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Data collection phases and participants.

| Phase 1 | Online support forums via ZOOM |

|

| Phase 2 | In-depth interviews via ZOOM |

|

| Phase 3 | Focus group discussions via ZOOM |

|

Data collected at each phase were digitally recorded with participant permission, transcribed verbatim, and subsequently de-identified to protect participants’ anonymity. All data were preliminary coded using QSR NVivo16 using a hybrid inductive (data driven)17 and deductive18 approach. Deductive codes were derived from the WHO health system building blocks adapted for the Pacific EC context (Figure 1).7 The subset of data related to Leadership and Governance was then thematically analysed by authors GP and MK. Emerging themes and tentative findings were presented to the broader research team at several online meetings for verification through discussion and data triangulation. Thematic findings were further analysed to identify enablers of, and barriers to, effective EC responses to the COVID-19 pandemic related to Leadership and Governance in the Pacific region.

Ethics approval was provided by The University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference 2020/480) and registered with Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference 28325). Research protocols for Phases 1 and 2A of the research were also reviewed by the World Health Organization's AdHoc COVID-19 Research Ethics Review Committee (Protocol ID CERC.0077) and declared exempt. Reporting of study data adheres to Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR)19 and Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)20 guidelines.

Role of the funding source

The research funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, nor writing of the manuscript.

Results

We collected and analysed data from 116 participants representing clinicians, other HCWs, policymakers and regional health stakeholders across 20 different PICTs. Four key ‘leadership and governance’ themes emerged from the data: Health is political; Clinicians speak truth to power; EC leaders stepping up; and From disconnection to unity. Each theme is explored with illustrative quotes and accompanied by sub-themes classified as enablers and barriers to effective leadership and governance in Table 2.

Table 2.

Enablers and barriers to effective leadership and governance; thematic sub-themes.

| Enablers |

Barriers |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Health is political | |

| Good diplomacy All we can do is just be diplomatic and maintain cordial relationships, so we can at least get some of that money…. And so our approach now is, okay we don't like this but let's stay focussed on what we can achieve for the [local PIC] people, and maintain cordial relationships so at least something gets done, and the resources flow down to the people. So we put our own personal concerns to the background, less the people of [my country] suffer for it. |

Limited resources, capacity gaps and isolation I think the downside of it was that I don't think as a country we have faced a threat this big, and the fact that the [local PIC] Health System is very immature. They don't have capacity at all levels, so they were not really prepared for a major threat like this. |

| Positive and evidence-informed support from regional and Pacific partners Its small country where hospitals don't have autonomy, the biggest lessons learnt was – many of the small island countries have a WHO Country Office, that has resources and expertise. And you have to have a government that is responsive to the technical advice that was given, and for [my country] the government was very responsive, to the advice that they gave. |

Financial issues, lack of accountability / transparency and ethical challenges But our system of governance, the weakness of it, is when the leaders get involved and then there's money involved, and a lot of funds being pushed in for the COVID response, usually the funds get misused, especially if you have weaker administrators. Politics plays a big role in [my country] in how we implement. |

| Inclusive consultation with respected clinical and EC leaders I think the strength that came about, it was good that our emergency operation centre got activated and all the key players in all the Ministries were involved in meetings and planning from the onset. There was a lot of planning and a lot of contribution from the other Ministries. Although there were a lot of healthy discussions, there was some disagreements at the meetings as well. But people were able to be mature in order to discuss and to iron out the differences. |

Executive directions (from all levels) without consultation or good evidence I wish the government can trust its professionals to provide them with advice to make decisions based on their knowledge and they have the capacity. It seems like it's always a political move… |

| Supportive hierarchy of decision-making …we had to go and present to Cabinet last week, sitting in Cabinet – although our Medical Superintendent was there he wanted me to sit in in case a question comes out for the operational level. I was happy there was a body that we could submit these issues to raise it through our superior bosses, my own Minister and to Cabinet where they make decisions on that. |

Public pressure, donor pressure, external scrutiny and critique So I think we listen too much to our politicians, we listen too much to what the population thinks is right. A lot of the population is saying ‘Oh, we need this machine’, because Australia and New Zealand has that machine, but they don't think about how will we manage it, how are we going to keep up the maintenance of it. |

| Theme 2: Clinicians speak truth to power | |

|---|---|

| Authentic voice informed by experience I did create quite a few disagreements with my managers, but just because what I believe in, I had to do it. I know sometimes you will have to stand alone in your clinical leadership to make right decisions. It kind of pushed me through. |

Fear, risk and lack of support It's just like your immediate supervisors who were kind of not listening to you. And then you have to think of some way out again. [Tearful] It's really, really difficult. It was just like, nobody was there for you, that's all. You just have to think, think, think and do things on your own. And the smartest way you can to bring things in for the good of your staff. |

| Respect and trust for clinical authority Other strengths that stood out was how they used infection control, mainly, as their main advisor to the stakeholders’ committee. They did, because the thing is that, they knew they were not experts, and because it was run by nurses – so that was the good thing; they didn't undermine nursing input, it was supported. |

Disregard for clinical opinions Maybe they didn't see it as important as the way we were seeing it. Because we are on the ground with our staff. And we know the importance of having those kind of things. Yeah. Whereas, I don't know about them, I don't know what they were thinking at that time. ….the current situation is, what the Director-General says is what goes. So we've been working really hard to get him to see the clinicians’ point of view. But usually if he fancies something he'll be like ‘No, we'll do this’. |

| Workplace safety culture and strong clinical governance And it was trying to balance keeping our staff safe and trying to have enough time to put all our systems in place so that we could open again and make sure that our patients were safe. So the decision to close the hospital was quite hard, and then making the decision to open it up again to the new normal service was also quite hard…. So it was just a balance between trying to keep everybody safe and also make sure that we're providing the essential service that we do. |

Health system fragmentation Like I mentioned, they haven't really involved us clinicians. We're not really involved in the COVID-19 program and rollout. So, we've attended meetings but. They've all kept it up with the officials at the provincial government |

| Theme 3: Emergency Care leaders stepping up | |

|---|---|

| Systems thinking and ‘cross-level’ insights I was in the midst of it at the highest level with the Prime Minister and those advisory levels and all the way down to operational right in the ward with the COVID patients. So that is why I have such a big insight. I know I can stand in the ward and take care of COVID patient right up to critical care, and at the same time too I can be at the strategic level and be comfortable there as well. So that's why my insight is a cross level insight, it's all over. |

Youth, inexperience and gender Number one, I am the youngest in the task force; number two, when I look around in the taskforce, I didn't have the qualification to talk with these big guns, the decision makers. The decision makers include the CEO, the minister for health, all the heads of departments, and consultants in the other departments. They [are] sitting there with their qualification and they may say ‘Who is this idiot trying to tell us what to do?’. The biggest difficulty was trying to run a young department getting my staffs [sic] to be happy. |

| Rapid responsiveness and decision-making And actually at times, I guess one of the beauties of our speciality is that we have to sometimes make decisions on the go, and many times when it's a crisis situation other specialities usually are not really forthcoming, there's a lot more dialogue expected before a decision gets done. And so that's where you need an Emergency Physician to say no, we need to do this now, and then you guys can keep on doing the thinking for a better option. |

Stress, doubt and burnout I did find it challenging, especially initially with COVID; a lot of focus was placed on COVID initially when we had the pressure for the first flight to come, and the pressure to ensure that things were up and running. We were pressured to work long hours to ensure that things were delivered and whatever was required was provided to the emergency operation centre. |

| Past experience with other surge events So, before COVID, I mean way before that, we had a leptospirosis outbreak and then realised that we were the missing link – between public health and the hospital health services. And then I volunteered to join and be in the meetings. And then we established that link and that the lepto[spirosis] outbreak finished, we had the measles outbreak, and then this just further strengthened our relationship and then COVID happened. And because it was part of the public health response I went into being the representative again to our hospital taskforce, and then to our national taskforce as well, because I was representing emergency medicine for the other two outbreaks as well. |

Disregard and lack of understanding about EC Emergency Medicine is not accepted in the country where they think ‘What is that?’, when I started. Yeah. They don't really know how important emergency medicine is yet. Not unless, you know, they come in with an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and wake up, for a bit. |

| Regional network of support And what also helped was because I was able to get evidence from the ACEM group and also from the network of emergency physicians, I was able to ask them what they thought as well, to ensure that whatever I said in the meeting had some background basis and it wasn't just my opinion. |

|

| Theme 4: From disconnection to unity | |

|---|---|

| Collaboration and information-sharing I think there was a lot of positiveness that came around. It was actually a good experience in terms of working with the stakeholders, at a stakeholders’ meeting to sit in a multidisciplinary and, sitting down and learning from each speciality for example, learning how the labs operate in terms of blood transportation, learning from the risk managers and the advisers on how to put out standards and guidelines. |

Authoritative decision-making ….but now [government] are in control, and they don't want to be advised and they are the ones driving everything, they are the drivers. They don't encourage the professionals to give advice to them; now it's them that make the decision. |

| Knowledge acquisition, problem solving and simulations All our decisions that we made were through discussions with my core brains trust, [consisting of] two emergency physicians, a couple of physicians, paediatricians and some of the critical care guys join us. In those discussions we [focused] on issues we foresaw, those hard ethical issues, what happens in this case, how do we transfer, what category of patients do we transfer, all of that went into the ERP, our response plan and SOPs for the patients. When we made that decision it was documented and critical care planning was documented as part of our meeting minutes. Initially it was just discussions but we realised that we had to have it all documented so it all turned into minutes, SOPs and the Emergency Response Plan, depending on whether it operational, strategic or just a discussion in the meeting which needed to be addressed, so that dictated which document it fell in. |

Division between clinical service and public health ..a lot of the decision making was done by Public Health without consultation of the clinicians, the clinical side. It's just now. And we had some admin issues. The clinical side didn't have a Head for a couple of months…. |

| Relationships, community and culture And I think one of the other things is that, at the moment, within the hospital, we have quite young leaders. Like even the surgical consultants, they're not that old. So it's quite easy to communicate with everybody, cause you sort of know them. That hierarchy is not there, that ‘Oh how will I approach this person?’, so it makes decisions quicker, like chasing up a result, getting someone to get a swab done early, it makes it all more faster and easier and builds more bridges with everybody. Develops a very good culture that hopefully will be sustained after COVID. |

Siloed health system Though communication is good, in the initial stages it wasn't that easy. In the initial stages, the tribal nature of a hospital facility, you know, everybody wanting to have their own way – the medical specialty, O&G, emergency medicine – and trying to have your piece of the cake, to tell them that we're all part of the team. Initially it was a barrier, but then we were able to iron it out, because we were able to voice our concerns, and our concerns were, we ended up realising it was very useful for the hospital as a whole. Then everybody came back to realising that yeah we're all equal parts of the puzzle rather than one bigger than the other. That was one of the barriers. |

| Partnerships, regional support and technology Committee meetings that should be ongoing and frequent and we have our development partners like NZ, Aust, MFAT and DFAT and NGOs and World Bank that attend these meetings too. We provide updates and they inform us how they can support to the committee. I think that is one thing that needs to be maintained: good collaboration with our partners, developments partners and within the hospital. |

|

Theme 1: Health is political

For better or worse, study participants from the Pacific region reported that politics and leadership at the government, health ministry and hospital executive level profoundly influenced in-country COVID-19 management. Participants identified that effective COVID-19 responses occurred when national governments included clinical and health leaders as respected actors in their decision-making, and where authorities were principally motivated to ground pandemic planning and response in people's safety.

When the pandemic threat emerged in 2020, some government leaders demonstrated political resolve to protect their citizens, making bold decisions to prioritise health:

“The other main strength was the political will to protect the health of the people, such that the decision to stop cruise ships from coming here was not hard, even though tourism contributes 60% of the country's income. I think there was a willingness on the part of the leadership in government to protect the people from COVID.”

HCWs were heartened by their leaders’ clear support and rapid pivot towards health system preparation:

“Fortunately, we had a lot of support from our ministry, in fact the whole country. The whole ministry dropped everything else and focussed only on COVID and preparing the country.”

In addition to government solidarity, having political and business leaders support pandemic preparedness ensured an increase in donor resources for the health system and HCWs on the ground:

“Because it was a pandemic that threatened the whole country, the business community came on board, the Prime Minister gave his support. Once we got political support we managed to mobilize a lot of resources... they liaised with donor partners to pour in funding and support.”

Despite lack of experience nor familiarity with political advocacy, some HCWs were able to inform government pandemic policy and planning at the highest level, and felt validated by the respect and responsive support they received from senior politicians.

“We were new to international health relations… this pandemic really shook us [and we recognised we] really need to do stuff like this. We are very fortunate our Minister and our President really believed in our response. So they got behind our Minister of Health's effort and our Congress was against [borders] opening”

Well prepared HCWs engaged political support for practical service provision process and clinical infrastructure improvements - essential building blocks of EC systems. For smaller PICTs, having Prime Ministerial approval for specific plans unlocked access to resources from multiple government bodies:

“The other positive thing was that they [EC personnel] were very strategic in getting resources... Before [we] actually went into lockdown, they were ready with their proposals of what's to be done, where they needed help, how much money [was needed] to build, to refurbish the staffing quarters and COVID ward. So they actually had a proposal ready for the [visiting] Prime Minister just to endorse. They actually got everything they wanted. And what made it best was that they were able to liaise with the highest authorities [and] get military people to come in to actually build up and refurbish the facility. They were able to get the Ministry of Infrastructure to come and do the mending of the hospital wards, like fixing cabinets and wards. It was actually a multi-Ministry approach, which was good timing.”

Where obscure political motivations seemed to override emerging evidence, clinician experience or expert advice, then HCWs became frustrated, demotivated and less trusting of their leaders to act in their, or their patients’, best interests. Without political support, clinicians rapidly understood their advocacy was in vain:

“If there's anything that I've learnt from this [it's that] you really need the right [political] people throwing their weight behind something like the COVID response to get things done. Otherwise you are just going to be fighting an uphill battle and it's frustrating.”

In some contexts, political interjection that overrode local health advice led to community conflict:

“There was a lot of discussion. People do not disagree that the Ministry of Health set up certain rules, but the campaigning of the parliamentarians - they continue to go the communities, they provide grog, and we tried to prevent [those community] social gatherings. But there was a clash with the parliamentarians.”

HCWs lamented situations in which their local expertise and contextual knowledge was not valued, and hoped for better government relationships, based on trust and respect:

“The leadership in the health department is poor. They lack guidance by clinical, subject matter experts, and [when] they get one, like, an international fix solution, [they] try to just implement it without contextualising it ... It's hard to trust most of our leaders”

Participants highlighted the various factors that acted as enablers or barriers to effective COVID-19 policy and planning outcomes, such as resource and health system limitations, international and regional partners and donors, Pacific cultural and country-specific strengths, and ethical and financial challenges (Table 2).

Theme 2: Clinicians speak truth to power

From data collection commencement in March 2020, despite initial fear and uncertainty, HCWs spoke with passion and integrity about their duty to serve the community and protect staff, colleagues and patients:

“There were a lot of things I was unsure of. If I'm going to die what insurance was I going to get? There was nothing clearly defined on what my work is, what's the weight, what hazard allowance should I be getting for this? [If I test positive for COVID-19 and] I get separated, I'm not going to see my family for the next two potentially three to four weeks or much longer. Those were the things I was left in the dark and not sure [about] … However, I also knew we had a duty of care to our patients. All doctors are called they have a duty of care, so I said to myself I have a duty of care”

Clinicians used their experience to authoritatively speak about acute service provision challenges and urgent patient and staff safety needs. Where clinical leaders were respected and empowered to drive COVID-19 responses, they demonstrated their expertise by implementing effective guidelines, training, supporting staff and mitigating fear and risks.

“Staff commitment, staff attitude, and strong leaders below me. As the Incident Manager I had leaders in surveillance and clinical care and all of them went above and beyond their responsibilities to get SOPs [Standard Operating Procedures] and other functional documents, and teach those things like treatment guidelines to the staff.”

The critical importance of clinical experience to meaningfully inform COVID-19 planning, policies and decision-making was obvious to HCWs across the region, but not necessarily to those in power:

“I think our executive doesn't really understand us; what we are trying to do to keep our patients and staff safe. We're trying to create this COVID screening and yet our management, the hospital executive, didn't actually put in an effort to address it for us. So we are trying at our end and the other end is not working. We are hitting against a brick wall at this point in time. We really want to set up something that will keep us safe with our patients, but it still hasn't come, the protection.”

HCWs strengthened their resolve to represent clinical service needs, ensure safety for their staff and appropriate stewardship of limited resources. Some senior clinical leaders were not afraid to speak truth to power, and set the example for others.

“I'd like to take the example of the ventilators, because it's a costly item. All the politicians are calling out, ‘We want ventilators, we need ventilators’… We asked one [PICT] head, who said ‘Yes, we need two ventilators here’. But, the specialist on the ground just said ‘No, we don't need a ventilator here, it's not a need here; we won't be able to manage, we won't be able to keep it’…. We need brave people like that who are able to say that, at this point of time, that is a waste of resources….”

Stakeholders recognised the importance of clinical leadership and were grateful to senior HCWs for standing strong and representing patients and staff consistently throughout the pandemic:

“Leaders, true leaders, are born in difficult situations. So I must acknowledge our senior colleagues and our anaesthetists, who stood up and steady against all the critics. That's our strength…”

Table 2 further outlines how authentic experience, positive support, respect and workplace culture can act as enablers and barriers to effective clinical leadership that positively influences COVID-19 policy and planning.

Theme 3: Emergency Care leaders stepping up

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Pacific EC clinicians (doctors and nurses) specifically have stepped up into leadership roles, often without prior experience or formal appointment to leadership positions:

“The emergency staff are leading transport. They're on all the care committees. They're on the national committee. And they're actually the people putting forward good evidence-based care and trying to override political decisions, as opposed to health science decisions. That's good”

Courage and audacity characterised the EC advocacy and leadership of some EC clinicians:

“I didn't pull any punches, I just went and told them straight. These are the Governor of the province and the major leaders. At one stage one of the members was like ‘Oh here comes Dr Know, he knows it all’… I just laughed it off. I said ‘Yeah well, expect another ear bashing’; I was just going to tell it straight. But they appreciated it because it addressed issues. I was advocating for my staff. We try to as be honest and transparent in our leadership as possible because there was a lot of money being spent and a lot of external resources…”

Issues around COVID-19 screening, triage and early clinical care are domains of expertise for EC clinicians, who sometimes had to explicitly justify their leadership role in order to ensure appropriate developments in these areas:

“I told them ‘look, if you want to convert the Emergency Department into trauma and non-trauma it means that we're going backwards... If that's the case then what is my role here as an emergency physician? I should go somewhere [else]?’. They sort of feel like ‘we are now getting the answer from the right person’. So that is the reason why they gave me this job and I am still here”

In addition to oversight of EC systems, some senior EC physicians demonstrated their flexibility and responsiveness for all urgent matters in the multi-sectorial COVID-19 response:

“I'll step up if I'm required on issues around quarantine, where no one wants to go. They call me in the middle of the night, and I'm up and get there and sort things out for them, which is what emergency physicians do all the time.”

EC clinicians used charisma to motivate their staff, build morale and create cohesion to meet the challenges of the pandemic:

“Because COVID is a very big challenge, it was a challenge for the staff to come together, to see them work together collaboratively to tackle this pandemic. With his [the local EC doctor's] great initiative,…he took control, he made everybody believe in him, …it has brought everybody together”

The team-based nature of EC was essential both for effective COVID-19 responses, but also as a model for other clinical service improvements:

“With emergency medicine it's not so much what the doctors do and the nurses do, it's more of a team, what we do together. And that system is working for us in our department. It's being noticed by the other specialties and they're trying to see how they can make [their team and processes] better. There's positive impacts”

Furthermore, EC clinician participants described overcoming their own fears to demonstrate leadership and set team standards. Having the support of a regional EC network empowered these clinicians through knowledge sharing and moral encouragement:

“When the first suspected case came through, I remember there was a lot of apprehension as to who's going to do it. I said to two of the senior nurses ‘We have to do the first case, we have to set the example – we need to go in and swab that patient because if we are scared to do it then everyone else is going to be scared in our team. We need to show them that it's okay’. I had to make sure that I understood, that I was clear in my mind, about how to don and doff, and what was the risk … Speaking to the network of emergency physicians helped me quite a lot to allay my fears and to ensure that things were done in a systematic, orderly way.”

Theme 4: From disconnection to unity

As noted in Theme 2, HCWs commonly identified themselves as working ‘on the ground’ and described a disconnection with those ‘at the top’ making decisions:

“Currently there's a detachment between the ground level clinical guys and the senior executive management.”

Sometimes this was understood as a hierarchy, with clinical care perceived as less important than other aspects of the health system:

“[An] issue we're facing here there is no synchronisation between pre-hospital and hospital care. The big hospital guys think they're far more important than hospital care.”

HCWs desired their ‘ground’ perspective to be heard and acted on through mutual, trusting relationships:

“There's power struggles happening everywhere.. People who're at actual operational level on the ground just want someone they can trust, and someone who hears their views and can put [them] into operation”

In turn, positive examples emerged of clinical and non-clinical stakeholder engagement, connection, inclusion and collaboration that led to unity for effective pandemic response. Indeed, multi-sectoral collaborative examples included whole community mobilisation:

“When this pandemic started we engaged all our stakeholders. We would have [multiple] community meetings... First, we'd have a group of the traditional leaders, then another where we'd target all the governors of the villages [and] the states .... Then we'd have another session with non-governmental community organisations like the Red Cross and [local] disability and women's groups. So we've had a lot of interaction with the community, the government and the leaders. Whatever we're going to do, we've already told them”

Top-down examples of effective leadership also demonstrated how cohesion and unity could be created in smaller PICTs:

“When we started giving [COVID-19] vaccinations the first people to receive them was one of our physicians and our President and Vice President, the President of the Senate, Senators – they were the first people, even before the doctors and nurses. They were the first ones and they took their picture, put it in the paper. So that helped the public – ‘If the President and the President of the Senate can take this we should be able to take this vaccine’. That tactic to engage the stakeholders really helped.”

Between public health and clinical or curative health teams, many participants spoke of the pandemic response overcoming traditional disciplinary or workplace silos and divisions.

“We found that during this COVID outbreak we managed to strengthen this link. We formed both hospital staff and public health teams and [went] into the community to do mass screenings, mobile fever clinics ... before we had our lifted lockdown. So that was another positive impact of this COVID outbreak”

Clinicians appreciated this new collaboration between public and curative health services, and made a plea for ongoing multidisciplinary unity into the future:

“And I think that was part of the bonus as well, getting public health part of our hospital stakeholders. Because we know it's a public health crisis, but the plans and the development of processes was done by the actual curative team, the hospital team. What I'd like to see in future is the continuous engagement [among] not only the hospital services but with the public health services as well, and also other stakeholders such as police and military inclusion, to better [future] operations”

Participants described how workplace and multi-sectorial unity was created through transparency of information-sharing and respectful, open dialogue without ulterior motive:

“I'd say good leadership, from both the admin level, administrative staff, and also in terms of the emergency department. Our HOU [Head of Unit] is very open to communication and dialogue with everybody. There's no hiding of information. If it's available it's widely disseminated to everybody, so that there's no hidden agenda so to speak. People supporting people, healthcare workers looking out for each other…”

Again, HCWs learnt and utilised new strategic diplomatic skills in order to appreciate wider perspectives, navigate and work towards a common pandemic response:

“The positive part is that if you make friends with the right people in those positions, [that] was very much important, because they are the ones who will actually help throughout the period. I learnt a little bit [about] diplomacy. Diplomacy is quite important, because everybody goes in with their agenda wanting to make sure that [it's] more important than the other person's. But all our agendas are important. So diplomacy was a positive part of the journey”

Clear communication flows from the ‘top level’ to HCWs on the ground enabled clinicians to understand and appreciate the rationale for decisions affecting their normal practices. This enabled them to uphold management decisions without ego or argument:

“I think one of the important things [was] the communication process; it [didn't] stop at a top level, it was actually filtered down. It was kind of difficult in the beginning, but people got to understand the reason and I think that was the important thing. It was no egos… [no one said] ‘I'm the senior here, I need to do my rounds’”

Even from a global partnership perspective, stakeholders shared positive examples of unity that transcended national borders and were enhanced through improved technology:

“The different governments represented here in [my country] also championed, also assisted. That was a really big help. Major countries like Australia, US, Japan and everybody, and India, they put in their efforts. Even China helped us prepare. The daily consultations with WHO and SPC, because of our fibre optic, we can [join] in Zoom like this, - a big plus for us”

Table 2 further explores how decision-making, health system structure, relationships, context and partnerships can act as enablers and barriers to overcoming disconnection and creating unity for effective pandemic responses.

Discussion

This is the first study to both critically and deeply explore the experience, insights and lessons of leadership and governance in the Pacific region from a predominantly EC clinical and related stakeholder perspective during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that politics profoundly influenced the pandemic response across all levels of the health system, even to granular components of workforce, infrastructure and EC process activities (Theme 1). Respected HCWs spoke with an authoritative voice to decision-makers, enabled through their clinical experience, workplace safety culture and duty to serve (Theme 2). Unique EC clinician attributes such as systems-thinking, rapid adaptability, team-based care and surge event experience from past Pacific emergencies and disasters equipped these clinicians to step up into leadership roles across national and subnational health systems and services (Theme 3). Collaboration between clinical and non-clinical actors, joint problem-solving, trust and open dialogue created unity towards effective pandemic responses in health workplaces and across sectors and disciplines (Theme 4). Effective pandemic health leadership and governance was enhanced by Pacific cultural strengths of relationship-building and community cohesion,21 but sometimes threatened by contextual political and resource challenges. HCWs, local leaders and PICT governments leveraged their networks for empowered support from regional and international government and non-government stakeholders who provided vital technical, professional and financial assistance for COVID-19 response.

Our study illuminated how bold, charismatic EC doctors and nurses are stepping up to lead both clinical and policy initiatives in their PICTs. This is consistent with what we know of Pacific EC leaders prior to the pandemic who demonstrated maturity and vision despite relative youth and inexperience, and their pre-pandemic ability to mobilise teams through leveraging goodwill, solidarity and regional support.12 Before and during the COVID-19 outbreak, EC clinician leadership is sustained and enhanced through regional networks of professional and personal support, such as the Pacific online EC support network which underpinned stage one of this research.22

Health leadership is also essential to creating cultures of safety to improve quality patient and community outcomes, in EC specifically12,23 and in emergency and disaster contexts generally.24 This is important to note given the disproportionate number of natural emergencies and disasters that the Pacific Island region annually experiences compared to other global regions.25,26 We found safety a key motivator for clinician leadership in the COVID-19 response, with EC personnel advocating for themselves and their colleagues, as well as on behalf of their patients and local communities.27 HCWs have an essential role in identifying, developing, monitoring and reviewing sustained safety and quality initiatives, especially resilient Pacific-based EC clinicians who engage in continuous active learning from the frontline in underserved and culturally-diverse settings.28 Certainly, this study found good governance in COVID-19 responses occurred where PICT political leadership responded to feedback loops from on-the-ground clinicians who were striving to adapt and implement new, cost-effective pandemic-driven safety and quality initiatives in the workplace and at systemic or structural levels.29 Safety framing gave the clinical voice authority. It elevated HCW advocacy as altruistic rather than self-serving – thereby empowering clinicians to ‘speak truth to power’ to advance authorities’ transparent and accountable pandemic management.

Fragmented health systems characterised by disconnection between health security, primary health care and universal health coverage have delivered less optional responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.30 Our study findings reiterate EC is the horizontal access point that links the community, primary care and the health system in times of emergency,31 with EC clinicians trained as systems thinkers and thus fundamental emergency and disaster responders at both the clinical or technical level, as well as policy and planning level in LMICs.32,33 In PICTs, strength and unity was created when clinical services were elevated and integrated into policy and planning at all levels. Engaging frontline HCWs and utilising EC knowledge leadership will be integral to shape positive, transformational post-pandemic, multi-sectoral improvements,34 and integration of health service delivery across all EC system building blocks.35 Indeed, the pivotal role EC and EC clinicians have and continue to play in the unfolding pandemic reinforces the centrality of EC in Pacific countries’ larger ambitions for Universal Health Coverage (UHC) achievement.7,36, 37, 38 Study findings further reinforce the important, crosscutting role EC has for complementary Sustainable Development Goal achievement39,40 and realisation of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.41,42 Here, the 2019 World Health Assembly Resolution on EC systems for UHC is a key guide.1

Finally, the power of the political determinants of health in shaping authorities’ pandemic planning and response throughout the Pacific region is highlighted by this research.43, 44, 45 Study findings demonstrate clear need for ongoing longitudinal research investigating the political determinants of health in emergency and disaster contexts through the leadership and governance WHO building block lens. In this study, politics, governance and trust have been confirmed as crucial ‘software’ elements for LMIC health system disease outbreak preparedness.46 We found that adaptive, inclusive governance generated through transparent and trusting communication was – and will continue to be - essential to the COVID-19 pandemic response.47,48 Similarly, we also found study stakeholders from across the Pacific region valued inclusive, responsive, transparent and evidence-informed governance to better enable appropriate and much-needed resources for EC system improvements to meet local pandemic complexities. HCWs were demotivated when they lost trust in their leaders through financial unaccountability, disrespectful and non-altruistic governance, and when their leaders failed to trust the experienced perspective of frontline clinical experts. As the participants in our study attest, embedding ethical practice49 and equity50 into health systems leadership to address social determinants8 and counteract situations where governance is restricted by limited resources and other challenges is of immense importance looking ahead.

Lessons learnt from this research (Box 1) also serve as recommendations for action, and align with recent consensus standards for EC systems development across the Pacific region which highlight recognition, support and collaboration as leadership and governance priorities.7

Box 1. Leadership and Governance lessons learnt.

-

•

Effective governance occurs when political, administrative and clinical actors work collaboratively in relationships characterised by trust, transparency, altruism and evidence

-

•

Clinician voice and clinical services must be elevated and fully integrated with technical, policy and planning components in the health system, to ensure resilience, accountability, quality and safety.

-

•

EC must be recognised as an essential component of the health system, and EC clinicians trained and supported in cross-cutting leadership roles for frontline service provision, health security preparedness and to meet UHC goals

-

•

Attention to the political determinants of health, and understanding unique Pacific cultural and contextual strengths will enhance multi-sectorial and regional networks of support and remain priorities for ongoing research

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Limitations to this overarching project have been documented in accompanying papers. For this focus on leadership and governance, a key limiting factor was the imperative to maintain confidentiality, thereby ensuring we only reported on general political data within countries and between individuals. Many of our participants were young EC clinicians with limited experience in multi-sectorial engagement and leadership. This brought a freshness to the data, but may have limited their perspectives of leadership and governance roles within the health system. Focusing on one building block illuminates specific strengths and gaps within one domain, but fails to capture whole EC system complexity and how each building block inter-relates to and influences all others.51

This study has highlighted how transparent, trustworthy and collaborative leadership and governance is crucial to effective COVID-19 responses. Engaged and respected EC leadership can strengthen governance to focus on quality, safety and integration of all health system components towards UHC. The Pacific regional COVID-19 experience can be an opportunity for transformative growth and trigger for PICTs to further act on the EC consensus roadmap for development.

Contributors

MC, GP, RM, CEB, GOR and SK were primarily responsible for study design. MC and SK coordinated funding acquisition and project administration. DS, MK, PP and BK provided regional perspectives and contextual advice throughout all aspects of the project. Study materials were developed by LH, MC, GP, RM, GOR, SK and CEB. All authors engaged in investigation and data collection through online support forums, interviews or focus group discussions. LH and SK were responsible for transcription, and LH completed preliminary coding and presentation of data to the broader research team. GP and MK coded, analysed and interpreted data for this building block. LH, MC, GP, RM, GOR, CEB, SK and DS contributed to overall thematic analysis and synthesis, including data triangulation and validation. GP developed the first draft of this manuscript. The final version was reviewed and approved by all authors.

Data sharing statement

De-identified and coded interview transcript data used to support the results in this article may be made available to interested stakeholders after careful consideration by the research project team and upon receipt of a written request to the corresponding author.

Declaration of interests

MC, GP, RM and GOR declare they are recipients of International Development Fund Grants from the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine Foundation. GP reports past research funding from the Pacific Community (SPC) and visiting Faculty status at the University of Papua New Guinea and Fiji National University. Additionally, RM reports grants from the Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade as well as scholarships from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Monash University. GOR reports that he is the recipient of a NHMRC Early Career Research Fellowship. CEB reports past research consultancy funding from SPC.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all EC clinicians and stakeholders across the Pacific who are involved with the COVID-19 pandemic response, especially those who participated in this study. Thanks also to the staff of the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine and the Pacific Community for their support of this project and the emergency care community more broadly. The authors also acknowledge other healthcare workers and public health personnel who have made significant contributions to pandemic responses.

Funders

Phases 1 and 2A of this study were part of an Epidemic Ethics/World Health Organization (WHO) initiative, supported by Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office/Wellcome Grant 214711/Z/18/Z. Copyright of the original work on which part of this publication is based belongs to WHO. The authors have been given permission to publish this manuscript. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of WHO.

Co-funding for this research was received from the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine Foundation via an International Development Fund Grant. RM is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Postgraduate Scholarship and a Monash Graduate Excellence Scholarship. GOR is supported by a NHMRC Early Career Research Fellowship. CEB is supported by a University of Queensland Development Research Fellowship. None of these funders played any role in study design, results analysis or manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.World Health Assembly. Resolution 72.16. Emergency care systems for universal health coverage: ensuring timely care for the acutely ill and injured. 2019 https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_R16-en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 3 December 2021.

- 2.Woodruff IG, Mitchell RD, Phillips G, et al. COVID-19 and the Indo-Pacific: implications for resource-limited emergency departments. Med J Aust. 2020;213(8) doi: 10.5694/mja2.50750. 345–349.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanefeld J, Mayhew S, Legido-Quigley H, et al. Towards an understanding of resilience: responding to health systems shocks. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(3):355–367. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.English M, Moshabela M, Nzinga J, et al. Systems and implementation science should be part of the COVID-19 response in low resource settings. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):219. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01696-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation . WHO's Framework for Action: World Health Organisation; 2007. Health Systems. Everybody's Business: Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcome.https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/everybody-s-business--strengthening-health-systems-to-improve-health-outcomes Accessed 3 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkerhoff DW, Cross HE, Sharma S, Williamson T. Stewardship and health systems strengthening: an overview. Public Adm Dev. 2019;39(1):4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips G, Creaton A, Airdhill-Enosa P, et al. Emergency care status, priorities and standards for the Pacific region: a multiphase survey and consensus process across 17 different pacific island countries and territories. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2020;1(1) doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayanore MA, Amuna N, Aviisah M, et al. Towards resilient health systems in sub-saharan africa: a systematic review of the english language literature on health workforce, surveillance, and health governance issues for health systems strengthening. Ann Glob Health. 2019;85(1;113):1–15. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West M, Armit K, Loewenthal L, Eckert R, West T, Lee A. Leadership and leadership development in health care: the evidence base. The Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management. London, UK. 2015. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/leadership-and-leadership-development-health-care. Accessed 3 December 2021.

- 10.Onyura B, Crann S, Freeman R, Whittaker M-K, Tannenbaum D. The state-of-play in physician health systems leadership research: a review of paradoxes in evidence. Leadersh Health Serv. 2019;32:620–643. doi: 10.1108/LHS-03-2019-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al Saidi AMO, Nur FA, Al-Mandhari AS, El Rabbat M, Hafeez A, Abubakar A. Decisive leadership is a necessity in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;396(10247):295–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31493-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips G, Shailin S, Lee D, O’Reilly G, Cameron P. You can make change happen’: experiences of emergency medicine leadership in the Pacific. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;34(3):398–410. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox M, Phillips G, Mitchell R, et al. Lessons from the frontline: documenting the experiences of Pacific emergency care clinicians responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100517. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Manen M. But is it phenomenology? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(6):775–779. doi: 10.1177/1049732317699570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(2):90–97. doi: 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (released in March 2020). 2020. https://support.qsrinternational.com/nvivo/s/article/How-do-I-cite-QSR-software-in-my-work. Accessed 3 December 2021

- 17.Boyatzis R. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crabtree B, Miller W. In: Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd Ed. Benjamin F, Crabtree B, William L, Miller W, editors. Sage publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. A template approach to text analysis: developing and using codebooks; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Equator Network. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. 2021. https://www.equator-network.org/. Accessed 3 December 2021

- 20.O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Capstick S, Norris P, Sopoaga F, Tobata W. Relationships between health and culture in Polynesia–a review. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(7):1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox M, Phillips G, Mitchell R, et al. Australasian College for Emergency Medicine; Melbourne, Australia: 2021. The Ethics of Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response: Experiences and Lessons Learnt from Frontline Clinicians in Low- and Middle-Income Countries in the Indo-Pacific Region During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Research Report.https://acem.org.au/getmedia/b3f78c65-8841-46eb-993b-bbc10dd37594/WHO-Report-R10 Accessed 3 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alshyyab MA, FitzGerald G, Albsoul RA, Ting J, Kinnear FB, Borkoles E. Strategies and interventions for improving safety culture in Australian emergency departments: a modified Delphi study. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2021;36(6):2392–2410. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacFarlane C, Joffe AL, Naidoo S. Training of disaster managers at a masters degree level: from emergency care to managerial control. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18:451–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Editorial Saving the Pacific islands from extinction. Lancet. 2019;394(10196):359. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31722-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McIver L, Kim R, Woodward A, et al. Health impacts of climate change in Pacific Island countries: a regional assessment of vulnerabilities and adaptation priorities. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(11):1707–1714. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aven T. What is safety science? Saf Sci. 2014;67:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kandasami S, Syed SB, Edward A, et al. Institutionalizing quality within national health systems: key ingredients for success. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(9):G136–G1G8. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzz116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wears RL, Hunte GS. Seeing patient safety ‘Like a State’. Saf Sci. 2014;67:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet. 2021;397:61–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strategic directions to integrate emergency care services into primary health care in the South-East Asia Region. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336568. Accessed 3 December 2021

- 32.Lecky FE, Reynolds T, Otesile O, et al. Harnessing inter-disciplinary collaboration to improve emergency care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs): results of research prioritisation setting exercise. BMC Emerg Med. 2020;20(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s12873-020-00362-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adam T, de Savigny D. Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(suppl 4):iv1–iv3. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner S, Botero-Tovar N, Herrera MA, Kuhlmann JPB, Ortiz F, Ramírez JC, et al. Systematic review of experiences and perceptions of key actors and organisations at multiple levels within health systems internationally in responding to COVID-19. Implement Sci. 2021;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01114-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasan MZ, Neill R, Das P, et al. Integrated health service delivery during COVID-19: a scoping review of published evidence from low-income and lower-middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis K, Brysiewicz P, Shaban RZ, et al. Nurses responding to the World Health Organization (WHO) priority for emergency care systems for universal health coverage. Int Emerg Nurs. 2020;50 doi: 10.1016/j.ienj.2020.100876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell R, Phillips G, O'Reilly G, Creaton A, Cameron P. World health assembly resolution 72.31: what are the implications for the Australasian college for emergency medicine and emergency care development in the indo-pacific? Emerg Med Australas. 2019;31(5):696–699. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schell CO, Gerdin Warnberg M, Hvarfner A, et al. The global need for essential emergency and critical care. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):284. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2219-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reynolds TA, Sawe H, Rubiano AM, et al. In: Disease Control Priorities (third edition). Volume 9: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. Jamison D, Gelband H, Horton S, et al., editors. The World Bank; Washington. DC: 2017. Strengthening health systems to provide emergency care; pp. 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shanahan T, Risko N, Razzak J, Bhutta Z. Aligning emergency care with global health priorities. Int J Emerg Med. 2018;11(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12245-018-0213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction . United Nations; Geneva: 2015. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030.https://www.unisdr.org/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf Accessed 3 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, Sub-Regional Office for the Pacific. Pacific islands launch sendai framework monitor. Online News Update. March 2018; Suva, Fiji. https://www.undrr.org/news/pacific-islands-launch-sendai-framework-monitor. Accessed 3 December 2021

- 43.Bambra C, Fox D, Scott-Samuel A. Towards a politics of health. Health Promot Int. 2005;20:187–193. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bambra C, Smith KE, Pearce J. Scaling up: the politics of health and place. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh R, Lal S, Khan M, Patel A, Chand R, Jain DK. New Zealand Economic Papers. Routledge; 2021. The COVID-19 experience in the Fiji Islands: some lessons for crisis management for small island developing states of the Pacific region and beyond; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palagyi A, Marais BJ, Abimbola S, Topp SM, McBryde ES, Negin J. Health system preparedness for emerging infectious diseases: a synthesis of the literature. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(12):1847–1868. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1614645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alami H, Lehoux P, Fleet R, et al. How can health systems better prepare for the next pandemic? Lessons learned from the management of COVID-19 in Quebec (Canada) Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.671833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen YY, Assefa Y. The heterogeneity of the COVID-19 pandemic and national responses: an explanatory mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):835. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10885-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mfutso-Bengo J, Kalanga N, Mfutso-Bengo EM. Proposing the LEGS framework to complement the WHO building blocks for strengthening health systems: one needs a LEG to run an ethical, resilient system for implementing health rights. Malawi Med J. 2017;29(4):317–321. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v29i4.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mukherjee J, Lindeborg MM, Wijayaratne S, Mitnick C, Farmer PE, Satti H. Global cash flows for sustainable development: a case study of accountability and health systems strengthening in lesotho. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(1):56–74. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2020.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sherr K, Fernandes Q, Kanté AM, Bawah A, Condo J, Mutale W. Measuring health systems strength and its impact: experiences from the African Health Initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(3):29–38. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2658-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]