Abstract

The protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) causes one of the most common human zoonotic diseases and infects approximately one-third of the global population. T. gondii infects nearly every cell type and causes severe symptoms in susceptible populations. In previous laboratory animal studies, T. gondii movement and transmission were not analyzed in real time. In a three-dimensional (3D) microfluidic assay, we successfully supported the complex lytic cycle of T. gondii in situ by generating a stable microvasculature. The physiology of the T. gondii-infected microvasculature was monitored in order to investigate the growth, paracellular and transcellular migration, and transmission of T. gondii, as well as the efficacy of T. gondii drugs.

Subject terms: Biomedical engineering, Parasite biology

Introduction

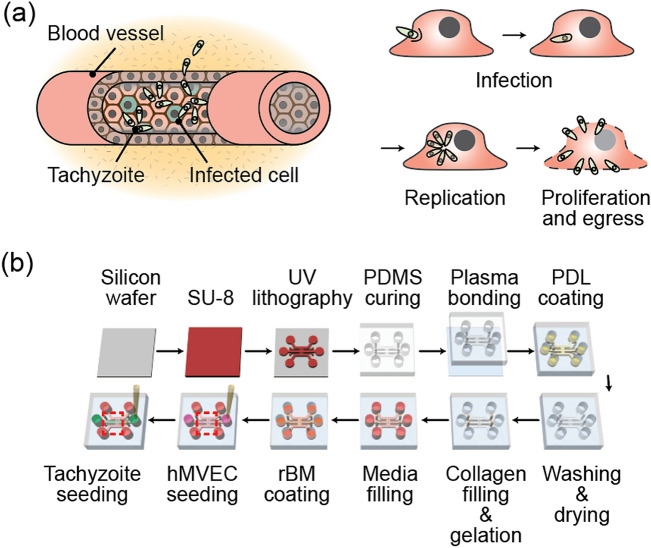

One-third of the world's population is infected with Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), the causative agent of one of the most prevalent zoonotic diseases1. Water, food, and soil contamination are the sources of infection2,3. Oocytes or cysts of parasites that have been ingested migrated from the intestine to secondary tissue. The majority of T. gondii infected individuals exhibit only mild symptoms. However, as immunity declines in conditions such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and organ transplants, disease severity increases. The clinical significance of T. gondii cannot be overstated, given that the pathogen has already infected a large number of people around the world4,5. T. gondii is capable of triggering both acute and chronic infections. The rapidly growing tachyzoites, highly dynamic stage of T. gondii, develop into slow-growing bradyzoites in chronically infected tissues6. Tachyzoites infect adjacent cells and tissues after entering blood vessels (Fig. 1a). They can cross biological barriers such as the intestinal barrier, the blood–brain barrier, the blood-eye barrier, and the placental barrier, causing severe diseases such as encephalitis7 and chorioretinitis5,8 and even fetal death9,10.

Figure 1.

(a) Diagrams showing the infection of a blood vessel by a tachyzoite. After penetrating the cell membrane, the tachyzoite relicates inside the cell and then egresses. (b) Pictorial representation of the manufacturing process for the microfluidics platform used in the experiment.

The intricate life cycle of T. gondii, which includes infection, proliferation, and dissemination, has been studies in laboratory animals7,8. Moreover, although infected animals can be sacrificed to trace the post-infection pathological status of a tissue, the intricate sequences that follow acute infection are still not fully understood9,10. Using immune cells such as macrophages11,12, dendritic cells12,13, microglia14, kidney15, brain16,17, and retina18,19, in vitro studies have monitored the infection and interaction between tachyzoites and the two-dimensional (2D) cultured host cells during tachyzoites replication, penetration, and migration. In the endothelial monolayer20,21 and epithelial monolayer22,23 models, the excretory/secretory proteases (ESPs) of T. gondii degrade junction proteins such as ZO-1, Claudin-1, Occludin, and E-cadherin, and increase actin filament redistribution and permeability. However, previous 2D studies do not accurately reflect the physiological microenvironment in during T. gondii infection. Alterations in the molecular expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1)15,18, parasite adhesion MIC215, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)24 in endothelial cells (ECs) have been revealed in adhesion and cell–cell junction penetration of tachyzoites.

Microfluidic systems have represented physiological fluid flow and microenvironment for T. gondii infection research. Lodeon’s Group reported that shear stress reduced the adhesion and motility of T. gondii on the EC monolayer25. Their another paper reported that infection with T. gondii affects Hippo and YAP signaling in ECs, thereby remodeling the cytoskeleton, altering permeability and causing junction damage in the EC monolayer26. However previous studies only with an EC monolayer on the bottom of a plastic cell culture dish lacked extracellular components below the EC monolayer as well as microenvironmental factors of actual tissues. T. gondii can more easily infect EC cells, but cannot migrate across them. The models were incapable of simulating the migration of tachyzoites across the EC monolayer into the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the complex interaction with neighboring cells. Other models with cerebral organoid27, organoid derived monolayers28, EC beads29, and incorporated ECMs (e.g., collagen and Matrigel)30–32 have demonstrated T.gondii's interaction with adjacent environmental factors. However, they located T.gondii on EC monolayer and made the pathogens penetrate vertically, necessitating the use of a confocal microscope for observation. In this study, we hope to direct pathogen movement and penetration in a horizontal direction through a vertically cultured EC monolayer, thereby providing a clear investigation on the complex T. gondii lytic cycle. We used hydrogel incorporating microfluidic platform reconstituting blood vessels to study angiogenesis33–35, vasculogenesis36,37, drug permeability26, and the transendothelial migration of immune38 and cancer cells39. Protocols were revised to examine tachyzoite migration through the EC monolayer into the ECM, and toward the neurons in order to investigate infection, proliferation, and migration of T. gondii, interacting with host cells and the surrounding microenvironment. under a microscope, a lytic cycle of the tachyzoite interacting EC monolayer, ECM and neurons was clearly observed in quantitative manner.

Materials and methods

Preparation of GFP-expressing T. gondii

The transgenic green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing T. gondii strain was created by Prof. Yoshifumi Nishikawa (National Research Center for Protozoan Diseases, Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Japan). GFP-positive tachyzoites were kindly provided by Dr. Young-Ha Lee (Chungnam National University School of Medicine, Korea). Tachyzoites was electroporated by PLK strain using transfer vector, plasmid containing DHFR-GRA5′-MCSGRA3′-GRA5′-GFP-GRA3′ fragment40. HeLa cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were inoculated with GFP-positive tachyzoites at a ratio of 1:3. After 3 days, tachyzoites were harvested from infected HeLa cells and passed twice through a 25-gauge needle and a 5 μm syringe filter (Millipore, USA) to remove cellular debris and host cells. The cells were then washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), centrifuged (3000×g for 5 min), and suspended in DPBS.

Preparation of EC and neuron

Purchased human microvascular endothelial cells (hMVECs) were cultured in complete medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). The hMVECs were used at passages 7 and 8, with a seeding density of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Neurons were isolated from the brain cortex of E15 ICR mouse euthanized by CO2 inhalation, according to procedures41,42, and were then immediately seeded and cultured. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and protocols approved by Korea University's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (KUIACUC-2017-71 and KUIACUC-2022-0028). The study was reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Preparation of the microfluidic assay

An ECM-mimicking hydrogel incorporating microfluidic assay was fabricated using soft lithography of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, MI, USA) as described previously43. The chip was sealed with a cover glass by using O2 plasma (Femto Science, Seoul, Korea). Channels were filled with poly-d-lysine (PDL; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. The PDL solution was washed and aspirated twice with sterile deionized water (DDW) and stored in an 80 °C dry oven until the day of the experimentation. Type I collagen solution was prepared with 10× PBS, NaOH, DDW, and type I collagen (BD Biosciences, CA, USA). The solution was then injected into the hydrogel channel and gelled for 30 min in a 37 °C incubator. After gelation, cell culture medium was filled into the medium channels. Recombinant basement membrane (rBM) was formed on the ECM using a Matrigel (BD Biosciences, CA, USA) coating to form a confluent and stable EC monolayer44. After rBM reconstitution, hMVECs were seeded at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml and cultured for 5 days to form a confluent EC monolayer (Fig. 1b).

T. gondii inhibitors

Genistein (4′,5,7-Trihydroxyisoflavone, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and blebbistatin (1-Phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-4-hydroxypyrrolo [2.3-b]-7-methylquinolin-4-one, a myosin II inhibitor) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as stock solutions45,46. Each stock solution was diluted with culture medium and the final concentration was adjusted to 100 μM. The calcium ionophore, A23817, was dissolved directly in the culture medium47. The final concentration of A23187 was 100 µM46. All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Imaging and analysis

Fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss, Swiss) was used to follow the infection and migration of tachyzoites. For imaging purposes, cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with a 0.1% Triton-X100 solution. Tachyzoites were tagged with GFP, and the cytoskeleton of ECs was stained with rhodamine and phalloidin (Invitrogen, MA, USA). 3D images were acquired with confocal microscopy (LSM700, Zeiss, Swiss).

Results

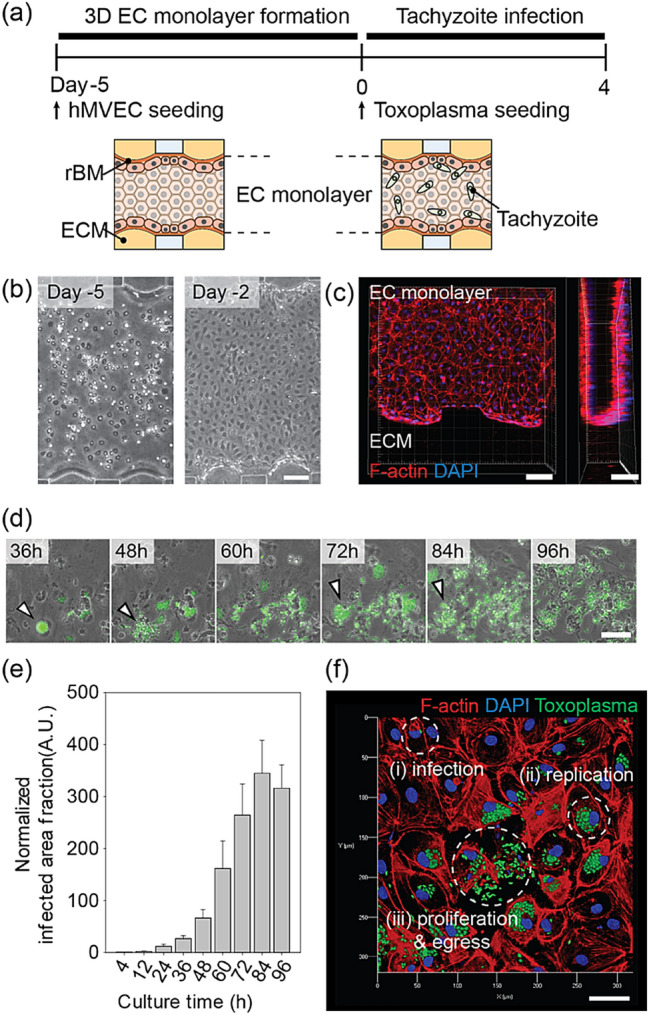

T. gondii infection and its transmigration to the confluent three-dimensional (3D) EC monolayer

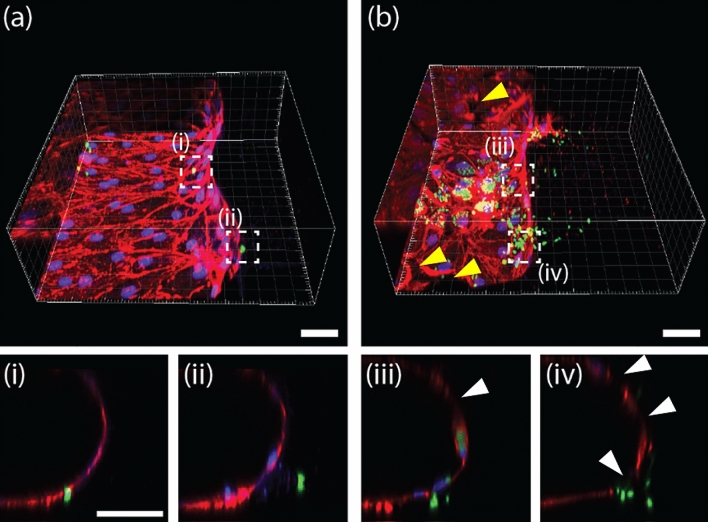

To reproduce the T.gondii infection to EC monolayer (Fig. 1a), we used a previously reported microfluidic model with 3D EC monolayer. As demonstrated previously, the reconstituted EC monolayer on the rBM above the type 1 collagen hydrogel was found to be 3D, confluent (Fig. 2a–c), and of low permeability44. Tachyzoites were seeded at a density of 2 × 106 cells/ml on the EC monolayer and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, to induce microneme protein48 mediated adhesion. The medium in the channels was refreshed every 12 h, during which time non-adherent tachyzoites were removed. The Lytic cycle of the tachyzoites in the EC monolayer, including infection, replication, proliferation, and egress was monitored (Fig. 2d–f). The tachyzoites proliferated in the infected ECs for 36 h before actively egressing from the host ECs and migrating through the ECM to invade the adjacent ECs. The normalized infected area increased rapidly after 36 h, indicating that the in vitro cycle (of infection to egress) was approximately 36 h, as previously reported49. Up to 60 h, the normalized increase rate of the infected area fraction was greater than 2.2 times per 12 h. However, the rate of area increase begins to slow at 72 h, peaks at 84 h, and then decreases at 96 h. Since the majority of the surrounding cells were damaged or dead, the egressed T. gondii was washed away by the flow when the culture medium was changed (Fig. 2e). The sequential steps of tachyzoites and ECs interaction were captured in a single image (Fig. 2f). In the case of uninfected or recently infected ECs, the junction remained intact and F-actins were evenly distributed around the nucleus (Fig. 2f(i)). After replication, the ECs became spherical and the intercellular spaces widened (Fig. 2f(ii)). During egression, the ECs disappeared (Fig. 2f(iii)). Some tachyzoites directly penetrate the EC monolayer during the early stages of infection (12 h after infection) (Fig. 3a(i–ii)). This penetration is clearly distinct from general mechanism, infecting ECs (Fig. 3b(iii)), migrating into the ECM after egress (Fig. 3b(iv)), and causing partial damage of ECs (white arrows) with a gap observed (yellow arrow) (Fig. 3b(iv)). This experiment cannot determine conclusively whether tachyzoite transmigration is paracellular or intracellular. Previous studies that cultured 2D EC monolayers in petri dishes or transwells18,20 could not make these observations.

Figure 2.

Tachyzoite infection model with a 3D EC monolayer in the microfluidic platform. (a) Time line of 3D EC monolayer formation and tachyzoite infection. (b) Phase images of EC monolayer at days 5 and 2. (c) Confocal image of the 3D EC monolayer on day 0 before seeding the tachyzoites. (d) Sequential phase images with 12 h intervals after the infection of tachyzoites. Infected cells indicated by arrowheads show the cycle, from duplication to egress. Scale bar indicates 100 µm. (e) Area fraction of tachyzoite in the EC monolayer and ECM region. (n = 8 for each group). (f) Overview of the tachyzoite cycle within the EC monolayer. Scale bar indicates 50 μm. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak method (e) and is indicated by asterisks as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Tachyzoites (GFP (green)) transmigrating the EC monolayer (rhodamine-phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue)) at (a) 12 h and (b) 60 h after infection. The image in (i–iv) at the bottom indicate a cross sectional view of the white box in (a,b). Tachyzoites were (i) either trapped in the EC monolayer or they (ii) migrated into the ECM after transmigration. Another image showing the coincident (iii) transmigration and proliferation (in an EC) of tachyzoites. (iv) Following egression, tachyzoites invade the ECM after disrupting the EC monolayer. Scale bar indicates 50 μm.

3D migration of T. gondii from the EC monolayer co-cultured with neurons

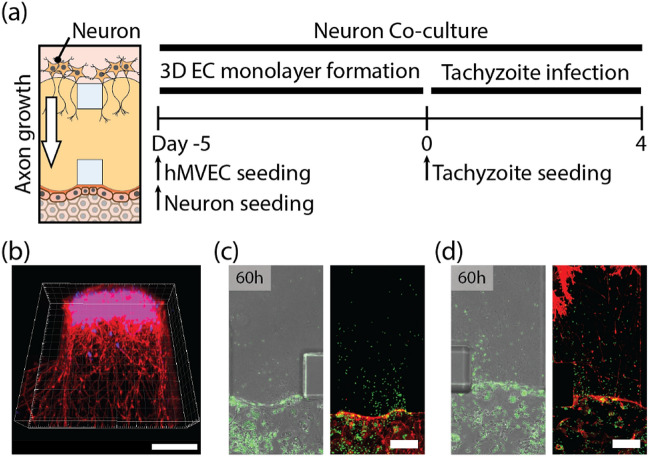

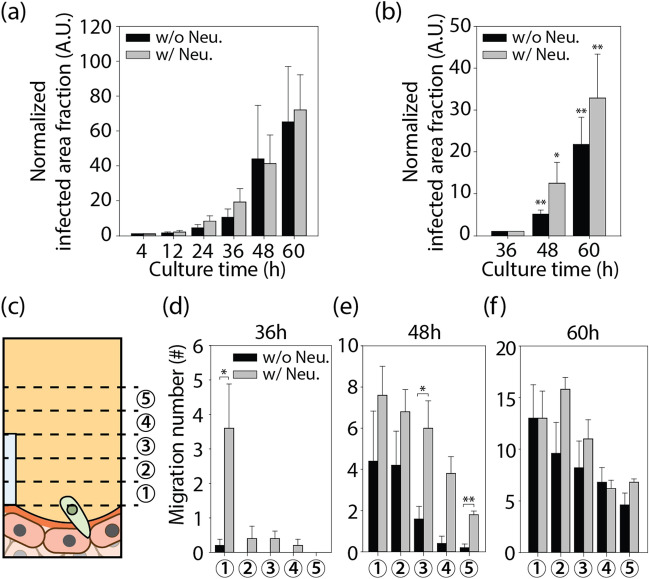

A microfluidic protocol for the co-culture of an EC monolayer with adjacent neurons was developed to model the encysted parasites that are commonly found in the brain during chronic infection50. Neurons were seeded on one side of the ECM to facilitate the 3D growth of axons in the ECM. After rBM coating, ECs were seeded on the opposite side of the ECM, and after 5 days, a confluent monolayer formed (Fig. 4a). After 5 days, neurons extended axons into the ECM (Fig. 4b). After a 36-h lytic cycle, tachyzoites infected the confluent EC monolayer and moved directly into the ECM (Fig. 4c,d). Notably, co-culturing neurons did not increase the number of tachyzoites in the EC monolayer, but it did increase their migration into the ECM (Fig. 5a,b). Figure 5c,d depict the egress of tachyzoites into the ECM when neurons are cultured, as indicated by the increased number of tachyzoites near the EC monolayer at 36 h. At 60 h, tachyzoites cultured in the absence of neurons began to egress from the ECs and reach a similar population in the ECM (Fig. 5e,f). Co-culturing tachyzoites with neurons appeared to enhance their invasion into ECM, but to have no effect on the invasion-egress cycle or the number of tachyzoites on the EC monolayer. Tachyzoites preferred to migrate out of neuron co-cultured EC monolayer, to initiate cycles of duplication, proliferation, and egress within the ECs. After 48 h, the migration of tachyzoites towards the neurons slowed down. According to a previous study, tachyzoites are co-localized with neurons, transform into bradyzoites and form brain cysts10,51. Previous studies have reported the presence of in vivo cysts in the neuron soma of the brain52,53 and the possibility of encephalitis54. In our experiments, we were unable to detect bradyzoites, tachyzoites infected neurons, or the formation of cysts (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 4.

Tachyzoite infection of the EC monolayer co-cultured with neurons. (a) Time line for EC monolayer formation (with neurons) and tachyzoite infection. (b) Confocal image of neurons (rhodamine-phalloidin (red) and DAPI (blue)) on ECM shows the 3D migration of axons into ECM. Fluorescent images after 60 h of tachyzoite infection (c) without and (d) with neurons. Scale bars indicates 100 μm.

Figure 5.

Tachyzoite area change (a) on EC monolayer and (b) into the ECM when cultured with or without neurons. (c) Quantification of the tachyzoite invasion of the ECM. (d-f) Number of individual tachyzoites in each region of interest at 50 μm intervals after 36, 48, and 60 h of tachyzoite infection (n = 5 for each group). Data are presented as averaged ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed for panels (b) and (d–f) by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak method and is indicated by asterisks as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

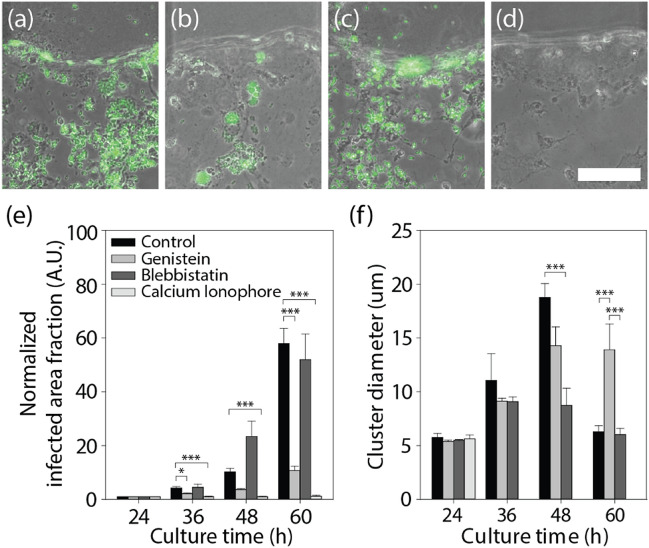

Effect of chemicals on T. gondii infection, egress, and transendothelial migration

In the microfluidic assay, three chemicals were evaluated: a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (genistein)45, a myosin II inhibitor (blebbistatin)55, and a calcium ionophore (A23817)47 (Fig. 6a–d). Each chemical was added to the medium and refreshed every 12 h until the end of experiment. The tachyzoite-infected area fraction and cluster size within infected cells were measured also every 12 h (Fig. 6e,f). It was discovered that both genistein and calcium ionophores significantly reduced the overall infection caused by tachyzoites. Only genistein, however, maintained tachyzoite proliferation within infected ECs. The ability of kinase inhibitors to block the effect of calcium ionophores on the egress of tachyzoites from host cells, such as kidney cells55 or neutrophils56, has been reported in prior researches. Using a microfluidic chip, we evaluated tyrosine kinase inhibitors to prevent the spread of T. gondii for the drug candidates of previous papers on T. gondii. Our experiments confirmed that microfluidic chips could be a promising platform for drug screening with parasitic infections. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor could be a promising target for the development of anti-T. gondii therapies. Calcium ionophore A23817 is known to inhibit host cell invasion and the intracellular replication of tachyzoites57, in addition to enhancing the egress of tachyzoites from host ECs prior to proliferation47,58. Experiments confirmed that the infected area fraction and cluster size of the tachyzoites decreased drastically as a result of the calcium ionophore's strong inhibitory effect on tachyzoite replication in host cells. However, A23817 demonstrated severe toxicity in ECs, which may restrict the drug's application. It is known that blebbistatin inhibits the actomyosin motor, myosin II, which forms bipolar filaments that constitute the contractile array by interlocking with actin filaments, thereby inhibiting ionophore-induced egress46. Nonetheless, blebbistatin was discovered to facilitate the egress of tachyzoites from their host ECs prior to complete proliferation. This finding supports the notion that myosin II also plays a role in tachyzoite egress from host cells, similar to its role in virus egress46,59.

Figure 6.

Chemical treatment of tachyzoites infecting the EC monolayer. (a–d) Images after 60 h of processing each chemical; (a) control, (b) Genistein, (c) Blebbistatin, and (d) calcium ionophore. (e) Proliferation of tachyzoites in the EC monolayer, and (f) their cluster size. Scale bar indicates 100 μm. Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Holm-Sidak method and is indicated by asterisks as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussions

We replicated 3D tachyzoite infection of EC monolayer adjacent to neurons in a microfluidic chip. Multiple days of T. gondii lytic cycle could be successfully monitored. T.gondii was able to easily infect EC monolayer, which contained their proliferation. T.gondii egressed from the infected EC monolayer and migrated through the ECM towards neurons. The inability to demonstrate neuronal infection of tachyzoites is one of the limitations of our research. Migration of tachyzoites was enhanced by the presence of neurons on the opposite side of the ECM, possibly due to neuron-secreted substances. Physical interaction between tachyzoites and axons could not account for the enhanced migration. Throughout their invasion, tachyzoites did not align with axons. Axons grew over only half of the ECM hydrogel, not reaching the EC monolayer; however there was a dramatic increase of tachyzoites around the EC monolayer 36 h after infection (Fig. 5d). The dramatic trans-endothelial migration may be attributable to the stiff gradient of enriched neuron-secreted substances over the EC monolayer. In our studies, tachyzoites did not infect neurons directly. For the reconstitution of advanced clue for the infection, i.e. cyst formation in brain, a complex cerebral microenvironment may be required, which could be realized with cerebral organoids in future research.

Through drug screening experiments (Fig. 6), the precise mechanism of anti- T. gondii drugs including A23187, Genistein and belbbistatin could be verified. A23187 was found very effective at eliminating T. gondii, but also caused previously unreported severe EC damage. The mechanism by which A23187 inhibits the egress of T. gondii appears to be completely distinct from that of genistein. The death of host cells can inhibit T. gondii proliferation, but also causes severe stromal damage. Additional in vitro experiments are required to determine the optimal concentration for pathogen suppression with minimal toxicity. The balance could be monitored using the developed model, which could be beneficial for the development of new anti-pathogenic drugs, considering effect on the microenvironmental factors. This in vitro study enables sequential real-time observations of the T. gondii lytic cycle, which was previously only confirmed in mouse model with expensive two- or multi-photon microscopy60,61. The developed method could be integrated with existing organoid technology as an advanced infection model with microenvironment62. Spatial segmentation of various microenvironmental components, including blood vessels, ECMs and neurons, was reconstituted, for the temporal application of a pathogen, T.gondii (Supplementary information).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government. (MSIT) (No. 2020R1A2B5B03002005) and the Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 20009125). H.J. Oh was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1C1C1011255) and a Korea University Grant.

Author contributions

H.K., S.-H.H., and H.E.J., and designed the research, developed and performed the experiments and analyzed the data with assistance from S.H., J.-A.K., and J.-H.Y. J.A. performed the experiments and prepared supporting information. H.K., S.-H.H., H.E.J., and S.C. drawn figures and wrote the manuscript. S.C. and S.-E.L. provided concept of the study. S.-H.H. and S.-E.L. provided Toxoplasma gondii and biological interpretation. H.J. O., S.C. designed the research, analyzed the data and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Hyunho Kim and Sung-Hee Hong.

Contributor Information

Hyun Jeong Oh, Email: holyhiphop99@gmail.com.

Seok Chung, Email: sidchung@korea.ac.kr.

Sang-Eun Lee, Email: ondalgl@korea.kr.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-15305-4.

References

- 1.Saadatnia G, Golkar M. A review on human toxoplasmosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;44:805–814. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2012.693197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones JL, Dubey JP. Foodborne toxoplasmosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:845–851. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Moura L, et al. Waterborne toxoplasmosis, Brazil, from field to gene. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:326–329. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.041115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joynson DHM, Wreghitt TG. Toxoplasmosis: A Comprehensive Clinical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16412-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunter CA, Sibley LD. Modulation of innate immunity by Toxoplasma gondii virulence effectors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:766–778. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subauste C. Animal models for Toxoplasma gondii infection. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2012;19:19.3.1–23. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1903s96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dubey JP, Frenkel JK. Toxoplasmosis of rats: A review, with considerations of their value as an animal model and their possible role in epidemiology. Vet. Parasitol. 1998;77:1–32. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(97)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu K, Roos DS, Angel SO, Murray JM. Variability and heritability of cell division pathways in Toxoplasma gondii. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5697–5705. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Speer CA. Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998;11:267–299. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Da Gama LM, Ribeiro-Gomes FL, Guimarães U, Arnholdt ACV. Reduction in adhesiveness to extracellular matrix components, modulation of adhesion molecules and in vivo migration of murine macrophages infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courret N, et al. CD11c- and CD11b-expressing mouse leukocytes transport single Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites to the brain. Blood. 2006;107:309–316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lambert H, Hitziger N, Dellacasa I, Svensson M, Barragan A. Induction of dendritic cell migration upon Toxoplasma gondii infection potentiates parasite dissemination. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1611–1623. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhandage AK, Kanatani S, Barragan A. Toxoplasma-induced hypermigration of primary cortical microglia implicates GABAergic signaling. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019;9:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barragan A, Brossier F, Sibley LD. Transepithelial migration of Toxoplasma gondii involves an interaction of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) with the parasite adhesin MIC2. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:561–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Däubener W, et al. Restriction of Toxoplasma gondii growth in human brain microvascular endothelial cells by activation of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:6527–6531. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6527-6531.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mammari, N., Vignoles, P., Halabi, M. A., Darde, M. L. & Courtioux, B. In vitro infection of human nervous cells by two strains of Toxoplasma gondii: A kinetic analysis of immune mediators and parasite multiplication. PLoS One9, 98491 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Furtado JM, et al. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites cross retinal endothelium assisted by intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in vitro. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2012;90:912–915. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nogueira AR, Leve F, Morgado-Diaz J, Tedesco RC, Pereira MCS. Effect of Toxoplasma gondii infection on the junctional complex of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Parasitology. 2016;143:568–575. doi: 10.1017/S0031182015001973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodman JP, Dimier IH, Bout DT. Human endothelial cells are activated by IFN-gamma to inhibit Toxoplasma gondii replication. Inhibition is due to a different mechanism from that existing in mouse macrophages and human fibroblasts. J. Immunol. 1991;147:2019–2023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen SF, Gans HA. Toxoplasma gondii . Pediatr. Transpl. Oncol. Infect. Dis. 2020;5:227–232.e3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briceño MP, et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection promotes epithelial barrier dysfunction of Caco-2 cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2016;64:459–469. doi: 10.1369/0022155416656349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramírez-Flores CJ, et al. Toxoplasma gondii excreted/secreted proteases disrupt intercellular junction proteins in epithelial cell monolayers to facilitate tachyzoites paracellular migration. Cell. Microbiol. 2021;23:1–19. doi: 10.1111/cmi.13283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki Y, Orellana MA, Schreiber RD, Remington JS. Interferon-gamma: The major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science. 1988;240:516–518. doi: 10.1126/science.3128869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harker, K. S., Jivan, E., McWhorter, F. Y., Liu, W. F. & Lodoen, M. B. Shear forces enhance Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoite motility on vascular endothelium. MBio5, 01111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Montoya, J. G., Boothroyd, J. C. & Kovacs, J. A. Toxoplasma gondii. Mand. Douglas Bennett’s Princ. Pract. Infect. Dis.2, 3122–3157.e7 (2014).

- 27.Seo HH, et al. Modelling Toxoplasma gondii infection in human cerebral organoids. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1943–1954. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1812435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holthaus D, Delgado-Betancourt E, Aebischer T, Seeber F, Klotz C. Harmonization of protocols for multi-species organoid platforms to study the intestinal biology of Toxoplasma gondii and other protozoan infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021;10:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.610368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McConkey CA, et al. A three-dimensional culture system recapitulates placental syncytiotrophoblast development and microbial resistance. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:1–9. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kanatani S, Uhlén P, Barragan A. Infection by Toxoplasma gondii induces amoeboid-like migration of dendritic cells in a three-dimensional collagen matrix. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:1–16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavlou G, et al. Coupling polar adhesion with traction, spring, and torque forces allows high-speed helical migration of the protozoan parasite toxoplasma. ACS Nano. 2020;14:7121–7139. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c01893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leung JM, Rould MA, Konradt C, Hunter CA, Ward GE. Disruption of TgPHIL1 alters specific parameters of Toxoplasma gondii motility measured in a quantitative, three-dimensional live motility assay. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chung S, Sudo R, Vickerman V, Zervantonakis IK, Kamm RD. Microfluidic platforms for studies of angiogenesis, cell migration, and cell-cell interactions: Sixth international bio-fluid mechanics symposium and workshop March 28–30, 2008 Pasadena, California. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2010;38:1164–1177. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-9899-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI), & © The Royal Society of Chemistry. Electronic supplementary material (ESI) for lab on a chip this journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012. Culture 5–8 (2012).

- 35.Seo H-R, et al. Intrinsic FGF2 and FGF5 promotes angiogenesis of human aortic endothelial cells in 3D microfluidic angiogenesis system. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28832. doi: 10.1038/srep28832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudo R, et al. Transport-mediated angiogenesis in 3D epithelial coculture. FASEB J. 2009;23:2155–2164. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-122820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim S, Lee H, Chung M, Jeon NL. Engineering of functional, perfusable 3D microvascular networks on a chip. Lab Chip. 2013;13:1489. doi: 10.1039/c3lc41320a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han S, et al. A versatile assay for monitoring in vivo-like transendothelial migration of neutrophils. Lab Chip. 2012;12:3861–3865. doi: 10.1039/c2lc40445a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeon JS, Zervantonakis IK, Chung S, Kamm RD, Charest JL. In vitro model of tumor cell extravasation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa Y, et al. Construction of Toxoplasma gondii bradyzoite expressing the green fluorescent protein. Parasitol. Int. 2008;57:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hutton, S. R. & Pevny, L. H. Isolation, culture, and differentiation of progenitor cells from the central nervous system. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc.3, 5077 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Harris, J. et al. Non-plasma bonding of PDMS for inexpensive fabrication of microfluidic devices. J. Vis. Exp.10.3791/410 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Shin Y, et al. Microfluidic assay for simultaneous culture of multiple cell types on surfaces or within hydrogels. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:1247–1259. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Han S, et al. Constructive remodeling of a synthetic endothelial extracellular matrix. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:18290. doi: 10.1038/srep18290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka T, et al. Growth inhibitory effect of bovine lactoferrin to Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites in murine macrophages: Tyrosine phosphorylation in murine macrophages induced by bovine lactoferrin. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1998;60:369–371. doi: 10.1292/jvms.60.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caldas LA, Seabra SH, Attias M, de Souza W. The effect of kinase, actin, myosin and dynamin inhibitors on host cell egress by Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol. Int. 2013;62:475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caldas LA, de Souza W, Attias M. Calcium ionophore-induced egress of Toxoplasma gondii shortly after host cell invasion. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;147:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Achbarou A, et al. Characterization of microneme proteins of Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1991;47:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(91)90182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dubey JP, Frenkel JK. Cyst-induced toxoplasmosis in cats. J. Protozool. 1972;19:155–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1972.tb03431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y. Effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection on the brain. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:745–751. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dubey JP. Advances in the life cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Int. J. Parasitol. 1998;28:1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weiss M, Cranston HJ, Weiss LM, Halonen SK. Host cell preference of Toxoplasma gondii cysts in murine brain: A confocal study. J. Neuroinfect. Dis. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.4303/jnp/N100505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cabral CM, et al. Neurons are the primary target cell for the brain-tropic intracellular parasite Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nath A, Sinai AP. Cerebral toxoplasmosis. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2003;5:3–12. doi: 10.1007/s11940-003-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caldas LA, Attias M, De Souza W. Dynamin inhibitor impairs Toxoplasma gondii invasion. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;301:103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walker EH, et al. Structural determinants of phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibition by Wortmannin, LY294002, Quercetin, Myricetin, and Staurosporine. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:909–919. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(05)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song H-O, Ahn M-H, Ryu J-S, Min D-Y. Influence of calcium ion on host cell invasion and intracellular replication by Toxoplasma gondii. Korean J. Parasitol. 2004;42:185–194. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2004.42.4.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caldas LA, de Souza W, Attias M. Microscopic analysis of calcium ionophore activated egress of Toxoplasma gondii from the host cell. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;167:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Leeuwen H, Elliott G, O’Hare P. Evidence of a role for nonmuscle myosin II in herpes simplex virus type 1 egress. J. Virol. 2002;76:3471–3481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3471-3481.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olivera GC, Ross EC, Peuckert C, Barragan A. Blood-brain barrier-restricted translocation of Toxoplasma gondii from cortical capillaries. Elife. 2021;10:1–34. doi: 10.7554/eLife.69182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Konradt C, et al. Endothelial cells are a replicative niche for entry of Toxoplasma gonsii to the central nervous system. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;1:549–562. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luu L, et al. An open-format enteroid culture system for interrogation of interactions between Toxoplasma gondii and the intestinal epithelium. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019;9:1–19. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.