Abstract

Background

Hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) including Eupeodes corollae are important insects worldwide that provide dual ecosystem services including pest control and pollination. The larvae are dominant predators of aphids and can be used as biological control agents, and the adults are efficient pollinators. The different feeding habits of larvae and adults make hoverflies a valuable genetic resource for understanding the mechanisms underlying the evolution and adaptation to predation and pollination in insects.

Results

Here, we present a 595-Mb high-quality reference genome of the hoverfly E. corollae, which is typical of an aphid predator and a pollinator. Comparative genomic analyses of E. corollae and Coccinellidae (ladybugs, aphid predators) shed light on takeout genes (3), which are involved in circadian rhythms and feeding behavior and might regulate the feeding behavior of E. corollae in a circadian manner. Genes for sugar symporter (12) and lipid transport (7) related to energy production in E. corollae had homologs in pollinator honeybees and were absent in predatory ladybugs. A number of classical cytochrome P450 detoxification genes, mainly CYP6 subfamily members, were greatly expanded in E. corollae. Notably, comparative genomic analyses of E. corollae and other aphidophagous hoverflies highlighted three homologous trypsins (Ecor12299, Ecor12301, Ecor2966). Transcriptome analysis showed that nine trypsins, including Ecor12299, Ecor12301, and Ecor2966, are strongly expressed at the larval stage, and 10 opsin genes, which are involved in visual perception, are significantly upregulated at the adult stage of E. corollae.

Conclusions

The high-quality genome assembly provided new insights into the genetic basis of predation and pollination by E. corollae and is a valuable resource for advancing studies on genetic adaptations and evolution of hoverflies and other natural enemies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12915-022-01356-6.

Keywords: Hoverfly, Chromosome-level genome, Pest predation, Pollination, Digestion

Background

Aphidophagous hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) are important insects for maintaining essential ecosystem services. The hoverfly Eupeodes corollae is a predominant aphid-specific predator and efficient pollinator in the field [1]. The larvae are important natural enemies and biological control agents for aphids, which feed on a wide range of aphid species, and have been reported to consume 3–10 trillion aphids in southern Britain each year [2, 3]. Because the larvae have limited dispersal abilities, female adults lay their eggs near plants with an aphid colony to support the maturation of the larvae, which is related to predation adaptation [4–6]. The adults feed on pollen or nectar, visit billions of flowers each year, and thus are key pollinators in natural ecosystems and agricultural crops [2, 3, 7, 8]. Several migratory hoverflies, such as Episyrphus balteatus and Eupeodes corollae, play important roles in improving pollination efficiency and maintaining hoverflies’ stable populations [9–12]. Considering that the populations of many beneficial insects, especially pollinators, are seriously declining [13, 14], hoverflies are becoming increasingly important. Moreover, larvae and adult aphidophagous hoverflies use different food sources, providing a model to study the evolution and transition of feeding habits. However, little is known about the mechanism underlying its special adaptation and evolution of predation and pollination.

Here, we present a high-quality draft assembly for E. corollae. Comparative genomic analysis revealed a number of gene families that likely contributed to the adaptation to predation and pollination. Moreover, numerous chemosensory genes and digestive enzymes with special or high expression levels at the larval stage were identified by transcriptomic analysis, and their function in predation and pollination is discussed. This genome assembly lays the foundation for in-depth research of E. corollae and will promote further analyses of predation and pollination in hoverflies and other natural enemies.

Results

Genome assembly and annotation of E. corollae

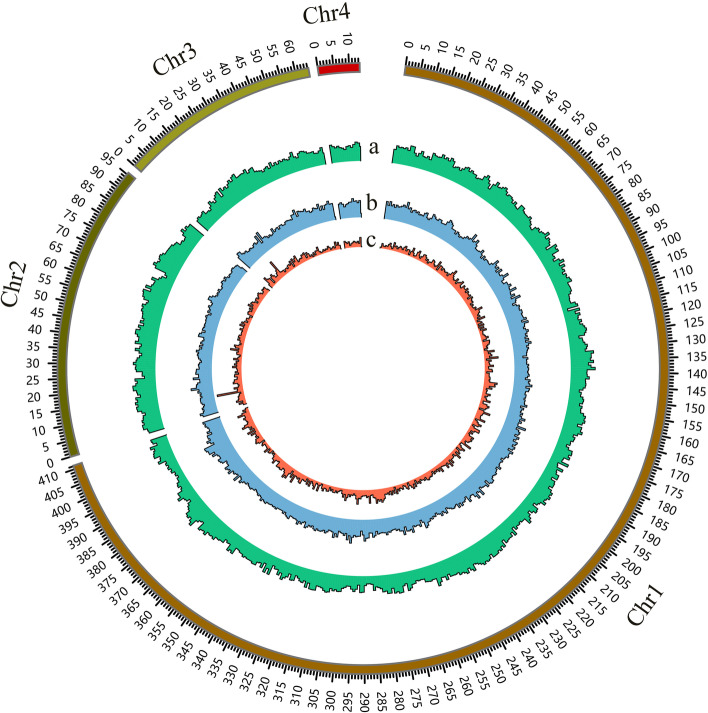

In total, 60.23 Gb of clean Illumina reads were obtained after filtering (Additional file 1: Table S1). The genome size and heterozygosity of E. corollae were estimated by k-mer analysis as 604 Mb and 0.84%, respectively (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). The PacBio Sequel platform yielded 65.77 Gb (~ 109 × coverage) of high-quality data for genome assembly. De novo assembly using Wtdbg2 [15] following self-correction by CANU (version 1.8) resulted in a final genome size of 595 Mb, including 3246 contigs with an N50 length of 1.8 Mb (Table 1). According to the karyotype results (n = 4) published previously [16], 570.8 Mb (96.0%) of the assembled sequences were anchored into four linkage groups with a total of 55.42 Gb Hi-C clean reads (Fig. 1, Additional file 1: Table S2).

Table 1.

Assembly statistics for the Eupeodes corollae genome and related statistics for three other hoverflies

| Statistic | Aphidophagous | Saprophagous | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. corollae | Scaeva pyrastri | Syritta pipiens | Eristalis tenax | |

| Assembled genome size (Mb) | 595 | 320.1 | 318.5 | 487 |

| Longest contig size (kb) | 10,130 | – | – | – |

| Number of contigs | 3246 | – | – | – |

| Contig N50 (kb) | 1794 | – | – | – |

| Number of chromosomes | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| GC content (%) | 33.8 | 22.6 | 28.6 | 28 |

| Number of gene models | 23,374 | 32,409 | 19,615 | 27,199 |

| BUSCO complete gene ratio (%) | 97.1 | 99.0 | 98.9 | 98.9 |

| Repeat (%) | 51.47 | 30.05 | 30.89 | 47.58 |

Fig. 1.

Eupeodes corollae genome landscape. Tracks in 1-Mb windows. a Distribution of GC content. b Repeat sequence density. c Gene density

We assessed the genome assembly by aligning the Illumina data with it, resulting in a mapping rate of 98.14% and a coverage rate of 97.82%. Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) analysis of the current genome identified 97.1% of the complete BUSCO genes (Additional file 1: Table S3), suggesting high integrity of the genome assembly.

We identified 306 Mb of repeat sequences, constituting 51.47% of the E. corollae genome (Additional file 1: Table S4). Among the repeat families, long interspersed elements (LINEs) (23.35%) were the most abundant repeat elements. In total, 23,374 gene models were predicted in the E. corollae genome (Table 1). For functional annotation, 16,878 (72.21%) genes had hits in the Nr database and 12,016 (51.41%) genes in the Swiss-Prot database (Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

Gene orthology and evolution

We compared the protein-coding genes from E. corollae with those of 15 dipteran insects, three coleopteran insects, and two hymenopteran insects to identify orthologous groups. Among them, 20,128 genes in the E. corollae genome clustered into 11,218 orthogroups (Fig. 2). The E. corollae genome contains 254 Syrphidae-specific genes, which were enriched in GO terms nitrogen compound metabolic process, cellular metabolic process, and cellular biosynthetic process (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05) (Additional file 2: Table S5). A total of 1640 species-specific genes were identified in the E. corollae genome. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were enriched in GO terms organonitrogen compound biosynthetic process and lipoprotein biosynthetic process (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05) (Additional file 2: Table S6). For the phylogenetic tree construction, 333 single-copy genes from the 20 species were used. In this analysis, E. corollae clustered with four other species of Syrphidae (Fig. 2). Estimations of divergence times suggest that E. corollae and Scaeva pyrastri may have diverged from their common ancestor approximately 54 million years ago (Mya).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships and gene orthology of Eupeodes corollae and other insects. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was calculated based on 333 single-copy universal genes. The colors in the histogram indicate categories of orthology: 1:1:1, single-copy universal genes; N:N:N, multicopy universal genes; species-specific, genes without an orthologue in any other species; Syrphidae-specific, genes specific to the family of Syrphidae; Brachycera-specific, genes specific to Brachycera lineage; Nematocera-specific, genes specific to the Nematocera lineage

Comparative genomic analyses

E. corollae and S. pyrastri are both aphidophagous hoverflies with similar biological characteristics and belong to the tribe Syrphini in the family Syrphidae. We compared the genome of E. corollae with S. pyrastri to uncover the mechanisms underlying its predation and pollination abilities. The 1718 homologous genes in E. corollae were enriched in GO terms serine hydrolase activity (GO:0,017,171) and cuticle development (GO:0,042,335) (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a, Additional file 2: Table S7), including trypsin (4) and cuticular protein genes (5). These genes are involved in protein digestion, cuticle development, and innate immunity in insects [17, 18].

Fig. 3.

GO enrichment in proteins encoded by homology genes in Eupeodes corollae compared with the genome of aphidophagous hoverfly (a), predator ladybugs (b), and pollinator honeybees (c). GO enrichment in cellular component, molecular function, and biological process. x-axis: RichFactor, number of homology genes/all genes for GO term; y-axis: pathway name. Ladybugs: Coccinella septempunctata, Harmonia axyridis, and Propylea japonica; honeybees: Apis cerana and Apis mellifera

E. corollae and ladybugs (Coccinellidae) are both important natural predators of aphids. However, E. corollae larvae are monophagous insects that mainly feed on aphids, while the larvae and adults of ladybugs are polyphagous, preying on many pests such as lepidopteran larvae and aphids. In a comparative genomic analysis among E. corollae and three predatory ladybugs Coccinella septempunctata, Harmonia axyridis, and Propylea japonica, 1283 homologous genes in E. corollae were enriched in GO terms G-protein-coupled receptor activity (GO:0,004,930) and feeding behavior (GO:0,007,631) (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3b, Additional file 1: Fig. S3, Additional file 2: Table S8), including three gustatory receptors (GRs), which mainly involved in the perception of chemical signals, such as sugars or bitter compounds [19, 20], and three takeout-like proteins, which have been reported to play important roles in the circadian regulation and feeding response in Drosophila [21].

In addition, to elucidate the mechanism underlying pollination, we compared the genome of two honeybees Apis cerana and Apis mellifera with that of E. corollae, all of which are efficient pollinators. The 431 homologous genes in E. corollae were enriched in GO terms sugar:proton symporter activity (GO:0,005,351) and lipid transport (GO:0,006,869) (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3c, Additional file 1: Fig. S3, Additional file 2: Table S9), including trehalose transporter and phospholipid-transporting ATPase. These genes were found to be associated with pollination behavior and energy production during migration and might contribute to the pollination adaption in E. corollae.

The genomic basis of aphid digestion

Our manual annotation of the digestive enzyme genes in the E. corollae genome yielded 153 serine proteases (SPs) (58 trypsin and 26 chymotrypsin), 44 carboxypeptidases, 8 α-amylases, 30 aminopeptidases, 41 phospholipases, and 36 lipases (Table 2). The large number of SPs among the digestive enzymes in E. corollae is consistent with the expectation that carnivorous insects have relatively greater protease activity than other insects [22]. When compared with other dipteran and coleopteran species, E. corollae had the fewest protease genes, which may be due to its digestion of a single-food diet such as aphids, in contrast to a broad diet of polyphagous insect species. For example, SPs were significantly expanded in the omnivorous pest Apolygus lucorum [23]. However, E. corollae had more protease genes than in honeybees, which is consistent with the honeybees’ simple diet of sugar-rich nectar (Table 2). Several digestive enzymes were arranged in tandem on the genome, including a cluster of four trypsin genes with 86.1% amino acid similarity (Ecor10293-Ecor10296), four α-amylases with 79.9% similarity (Ecor16162-Ecor16165), and 10 phospholipases with 58.9% similarity (Ecor17802-Ecor17811), suggesting that a recent replication event enhanced digestion and absorption of aphids in E. corollae during evolution.

Table 2.

Number of chemosensory-related, detoxification-related, and digestion-related genes in the genome of various insects

| Gene | E. c | E. t | E. d | S. pi | S. py | C. s | H. a | P. j | A. m | A. c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemosensory | ||||||||||

| OR | 46 | 70 | 35 | 72 | 48 | 20 | 28 | 55 | 141 | 143 |

| IR | 36 | 40 | 15 | 40 | 55 | 65 | 48 | 84 | 27 | 26 |

| GR | 36 | 66 | 23 | 56 | 52 | 25 | 19 | 50 | 15 | 13 |

| OBP | 46 | 71 | 22 | 41 | 45 | 32 | 29 | 78 | 20 | 17 |

| CSP | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 28 | 19 | 47 | 6 | 5 |

| SNMP | 4 | 19 | 16 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 20 | 29 | 9 | 10 |

| Detoxification P450 | ||||||||||

| CYP2 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 10 | 17 | 8 | 6 |

| CYP3 | 31 | 36 | 24 | 35 | 30 | 36 | 42 | 64 | 28 | 26 |

| CYP4 | 23 | 39 | 29 | 30 | 21 | 18 | 28 | 111 | 4 | 5 |

| Mito | 13 | 17 | 8 | 14 | 14 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 74 | 98 | 69 | 85 | 73 | 65 | 89 | 202 | 46 | 43 |

| Detoxification GST | ||||||||||

| Delta | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Epsilon | 11 | 10 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| Omega | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Sigma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Theta | 3 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Zeta | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Microsomal | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 27 | 22 | 12 | 22 | 25 | 18 | 23 | 21 | 11 | 13 |

| Digestion | ||||||||||

| Trypsin | 58 | 103 | 58 | 103 | 96 | 66 | 54 | 127 | 33 | 32 |

| Chymotrypsin | 26 | 22 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 7 | 5 |

| Carboxypeptidase | 44 | 31 | 26 | 27 | 30 | 19 | 30 | 36 | 26 | 16 |

| Lipase | 74 | 58 | 29 | 52 | 58 | 69 | 52 | 96 | 22 | 26 |

| α-Amylase | 8 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Phospholipase | 41 | 17 | 11 | 19 | 28 | 17 | 18 | 27 | 26 | 25 |

| Aminopeptidase | 30 | 25 | 36 | 25 | 31 | 32 | 35 | 60 | 16 | 18 |

OBP Odorant-binding proteins, CSP Chemosensory proteins, OR Odorant receptor, IR Ionotropic receptor, GR Gustatory receptor, SNMP Sensory neuron membrane protein, GST Glutathione S-transferase. Abbreviations of insect species: E. c Eupeodes corolla, E. t Eristalis tenax, E. d Eristalis dimidiate, S. pi Syritta pipiens, S. py Scaeva pyrastri, C. s Coccinella septempunctata, H. a Harmonia axyridis, P. j Propylea japonica, A. m Apis mellifera, A. c Apis cerana

Because the larvae of E. corollae feed mainly on aphids and adults mainly on pollen, we compared the expression levels of digestive genes between eggs and larvae, larvae and pupae, pupae and adults, and larvae and adults. Compared to the genes in the eggs, most genes were significantly upregulated in larvae after they had fed on aphids, consistent with their roles in aphid digestion (Fig. 4a). In pupae compared to larvae, most digestive-related genes were downregulated (Fig. 4b). Because the adults feed on pollen or nectar, most digestive-related genes were upregulated in adults compared to pupae (Fig. 4c), suggesting that digestion mainly occurs in the larvae and adults. Compared to larvae, almost all (9 of 10) trypsins were downregulated in adults, while most other SPs (15 of 26) and phospholipase (4 of 5) and all 10 opsins and four carboxylesterase were upregulated in adults (Fig. 4d, Additional file 2: Table S10). We further compared the expression profiles of trypsin genes at different developmental stages. The results showed that nine trypsin genes (Ecor12299-Ecor12303, Ecor12307, Ecor13436, Ecor17954, Ecor18958) were significantly upregulated in first- to third-instar larvae and downregulated in adults (Fig. 4e), suggesting these genes might be involved in digestion and absorption of aphids.

Fig. 4.

Expression profile of digestion-related genes (a–d) and phylogenetic tree for trypsin genes (e) from different developmental stages in Eupeodes corollae. e Each data block represents the base 10 logarithm of FPKM (log10 FPKM) value of the corresponding samples

In the comparative genomic analysis between E. corollae and S. pyrastri, four protease genes (Ecor12299, Ecor12301, Ecor2966, Ecor7242) were identified as homologous genes in the two species (Fig. 2), and the expression levels of these protease genes were analyzed. The results showed that of the four trypsin genes, all but Ecor7242 were expressed strongly in larvae (Fig. 4e) and likely to be essential for digesting aphids in E. corollae.

The genomic basis of foraging behavior

As a predator of aphids and a pollinator, E. corollae relies on its chemoreception system to perceive chemical cues from its prey insects and flowering plants to mediate behaviors such as prey foraging, feeding, mating, oviposition, and pollination [5, 24–26]. In the genome of E. corollae, 36 gustatory receptors (GRs), 46 odorant receptors (ORs), 36 ionotropic receptors (IRs), four sensory neuron membrane proteins (SNMPs), four chemosensory proteins (CSPs), and 46 odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) were manually identified (Table 2). Fewer chemosensory genes were found in E. corollae than in other dipteran species [27, 28], which might be related to the narrow food habits of E. corollae.

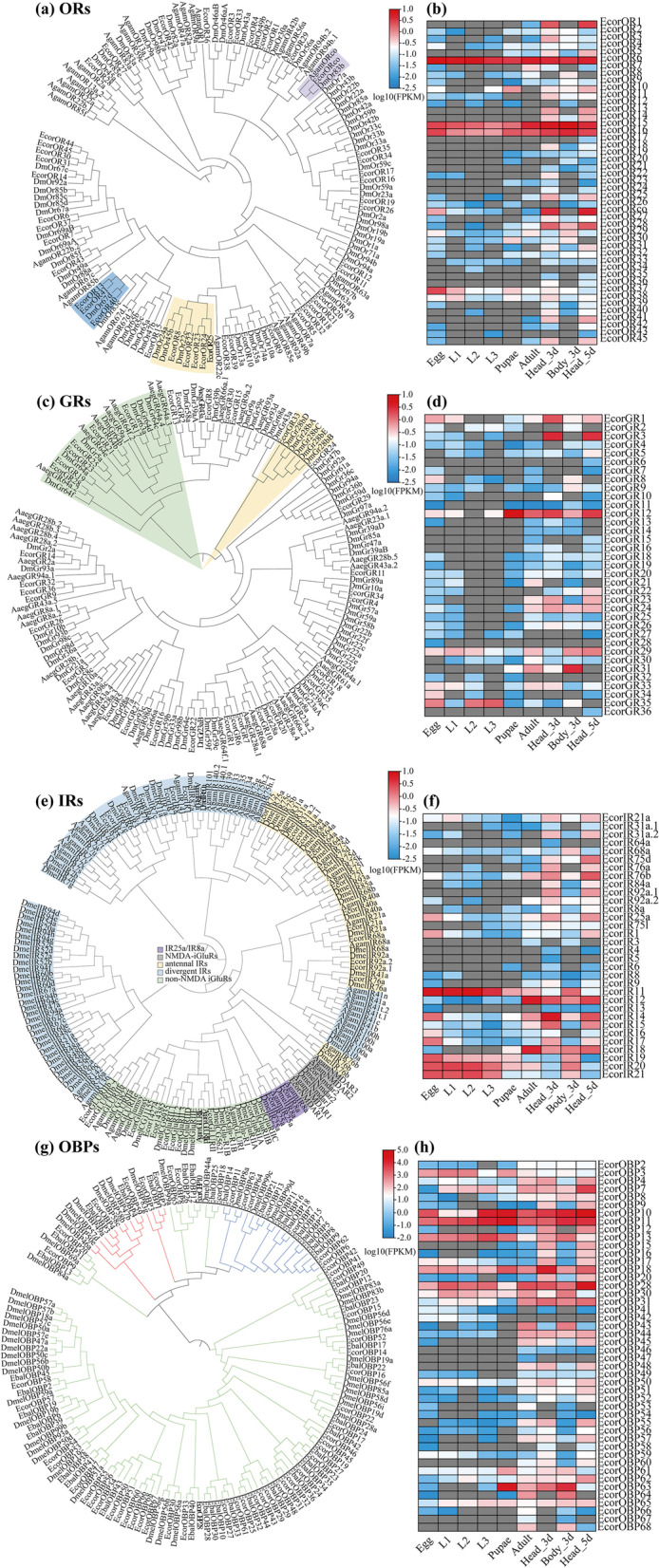

ORs are seven-transmembrane domain proteins, and their encoding genes are expressed in olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) for selectively sensing volatile chemicals in the environment [29, 30]. The number of OR-encoding genes identified in the genome assembly (46) is close to that in the previously reported transcriptome of E. corollae (42) and E. balteatus (51), but fewer than in D. melanogaster (62), A. gambiae (79), and A. aegypti (131) (Table 2) [20, 28, 31]. Further phylogenetic analysis showed that three EcorORs (EcorOR13, 40, 41) in E. corollae clustered with the pheromone receptor DmelOR67d [32], while EcorOR7 clustered with DmelOR69aB, suggesting these genes might be implicated in important roles in pheromone recognition in E. corollae (Fig. 5a). However, the homologous genes to other pheromone receptors DmelOR88a or DmelOR65a were not found in E. corollae.

Fig. 5.

Chemosensory-related genes in Eupeodes corollae. Phylogenetic tree of odorant receptors (ORs) (a), gustatory receptors (GRs) (c), ionotropic receptors (IRs) (e), and odorant-binding proteins (OBPs) (g) from E. corollae and other dipteran species. Predicted genes in E. corollae are indicated by different colors. a ORco (purple), pheromone receptors (blue), tandem repeats (yellow). c GR64 subfamily (green) and GR28 subfamily (yellow). e IR25a/IR8a (purple), antennal IRs (yellow), divergent IRs (blue), NMDA-iGluRs (gray), and non-NMDA iGluRs (green). g Classic OBPs (green), Minus-C (blue), and Plus-C (red). Species for this phylogeny included E. corollae (Ecor), Drosophila melanogaster (Dm), Anopheles gambiae (Agam), Aedes aegypti (Aaeg), and Episyrphus balteatus (Ebal). Expression profile of ORs (b), GRs (d), IRs (f), and OBPs (h) for different developmental stages of E. corollae. Each data block represents the base 10 logarithm of FPKM (log10 FPKM) value of the corresponding samples

Spatial and temporal expression of ORs showed that ORs were mainly expressed in the adult head at 3 and 5 days after eclosion (Fig. 5b), suggesting these genes might play important roles in mating and oviposition behaviors of E. corollae. In addition, three OR genes (EcorOR6, 15, 16) were highly expressed throughout development (egg to adult). Previous researches mainly focused on ORs that are highly expressed in the antennae of insects [33, 34]. However, ORs also have other important biological functions in non-head tissues in insects. For example, A. gambiae ORs are expressed strongly in the testes and function in sperm activation [35]. Thus, we speculated that these three ORs might have basic physiological functions in E. corollae.

GRs are mainly expressed at gustatory receptor neurons for sensing non-volatile chemicals, including sugars, bitter compounds, and carbon dioxide (CO2) [19, 20]. The number of GRs in E. corollae (36) was twofold higher than reported by Wang et al. (16) through transcriptome sequencing (Table 2). Phylogenetic analysis showed that six GRs genes clustered with the GR64 subfamily of D. melanogaster, which participate in sugar recognition (Fig. 5c). The expression profile analysis showed that seven GR genes were expressed at the adult stage, while two GRs were highly expressed at the larval stage (Fig. 5d).

IRs, which belong to the ionotropic glutamate receptor superfamily (iGluRs), were first found in D. melanogaster [36]. IRs can be divided into two subfamilies: conserved “antennal IRs” and species-specific “divergent IRs,” which function in diverse processes, including olfaction reception, taste sensing, and temperature and moisture detection [37–39]. More IRs were found here in E. corollae than reported by Wang et al. but similar to the 32 reported for E. balteatus [25]. Phylogenetic analysis showed that candidate antennal IRs clustered with “antennal” orthologues of D. melanogaster [38]. Homologs of DmIR68a were identified in our genome assembly, which were not found in a previous study [25]. Thirteen IR genes that clustered with the DmeliGluRs clade were identified as iGluRs of E. corollae (Fig. 5e). When these results are considered with the fact that the candidate antennal IR genes were mainly expressed in adult heads, then these IRs likely have olfactory functions; the other IRs had diverse expression patterns during development (Fig. 5f).

Besides chemosensory receptors, other chemosensory proteins, including OBPs, CSPs, and SNMPs, were also encoded by genes in the E. corollae genome. OBPs are involved in initial olfactory recognition by binding and transporting external odor molecules to the corresponding membrane receptors [40, 41]. We identified 46 OBPs encoded in the genome assembly, 18 of which were identified by Jia et al. The other 28 OBPs were named EcorOBP41–EcorOBP68. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that OBPs of E. corollae clustered with high bootstrap support into three clades: 34 classic, 4 plus-C, and 7 minus-C (Fig. 5g). Transcriptomic analysis showed that many OBPs (17 of 46) were highly expressed in adult heads (Fig. 5h).

Genomic basis of detoxification

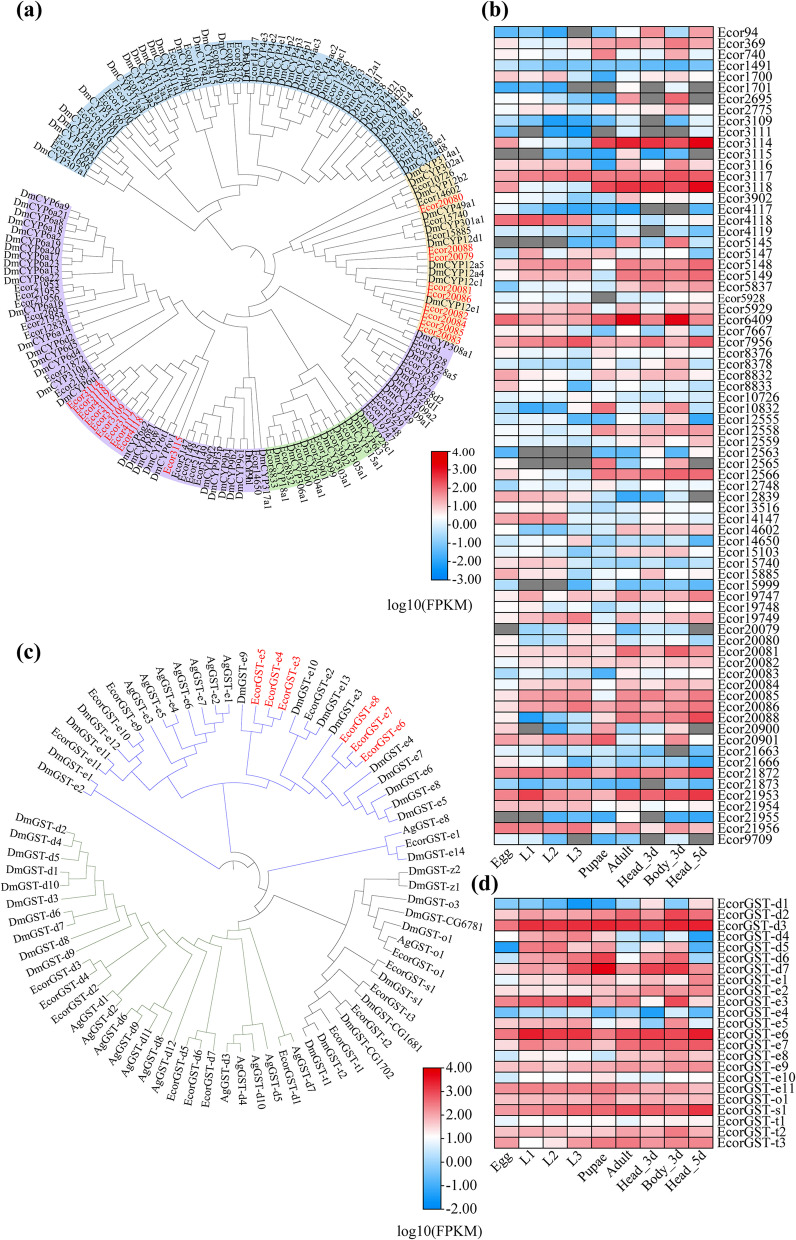

Detoxification enzymes are important for metabolizing natural toxins and synthetic insecticides in insects [42, 43]. Our manual annotation of detoxification-related genes included 74 cytochrome P450s and 27 glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) in the E. corollae genome. P450s are phase I detoxification enzymes involved in the metabolism of a wide range of endogenous and exogenous compounds [44]. E. corollae was predicted to have fewer P450s than D. melanogaster (85) and other dipteran species (Table 2) [45, 46]. Phylogenetic analysis indicated 10 genes (Ecor3109, Ecor3111, Ecor3114–Ecor3118, Ecor4117–Ecor4119) from the CYP3 clade, and 9 genes (Ecor20079–Ecor20086, Ecor20088) from the mitochondrial P450 clade were arranged in tandem in E. corollae genome (Fig. 6a, Additional file 1: Fig. S4). Nine expanded genes (Ecor3109, Ecor3111, Ecor3114, Ecor3116–Ecor3118, Ecor4117–Ecor4119) clustered with DmCYP6G2, which can metabolize insecticides (e.g., imidacloprid) and confer insecticide resistance to D. melanogaster [47, 48], suggesting that these proteins might contribute to the detoxification capacity of E. corollae. Based on the transcriptomic analysis, the expression of P450 genes differed among developmental stages and tissues, indicating diverse functions for the P450s (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree and expression patterns of cytochrome P450s and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) for different developmental stages and tissues of Eupeodes corollae. a Different colors on the clade indicate different CYP clans: CYP2 clan (green), CYP3 clan (purple), CYP4 clan (blue), and Mito clan (yellow). Tandem proteins are in red. b Inner branches in different colors represent different protein classes: green, delta class; blue, epsilon class. Tandem proteins are in red. Species in this phylogeny include E. corollae (Ecor), Drosophila melanogaster (Dm), and Anopheles gambiae (Ag). Expression patterns of cytochrome P450s (c) and glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) (d) for different developmental stages and tissues of E. corollae

GSTs are multifunctional enzymes in phase II detoxification [49]. The 27 putative GST genes identified in E. corollae encoded 23 cytosolic GSTs and four microsomal GSTs. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the 23 cytosolic GSTs were classified into five classes, with seven in delta, 11 in epsilon, one in omega, one in sigma, and three in theta (Fig. 6c). The delta and epsilon classes had the most members, which were insect-specific and involved in resistance to pesticides such as organophosphates and organochlorines [50–52]. Six genes from the epsilon class (EcorGSTe3-EcorGSTe8) were arranged in tandem. All GSTs were expressed at different levels at different developmental stages and in different tissues of E. corollae (Fig. 6d).

Discussion

The genome size of the assembly presented here for the hoverfly E. corollae was 595 Mb, close to the estimated genome size by 17-mer analysis (604 Mb), suggesting the assembly in our study was appropriate. We then compared this genome with those of insects with similar biological characteristics: aphidophagous hoverfly S. pyrastri, aphid predator ladybugs, and pollinator honeybees [53] to elucidate the genetic basis of predation and pollination. These comparative analyses revealed a number of genes in E. corollae that are strongly linked to digestion, feeding behavior, chemoreception, sugar symporter activity, and lipid transport, such as genes for trypsin, takeout, GRs, trehalose transporters, and phospholipid-transporting ATPase, which are important for predation and pollination [19–21]. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that 10 opsin genes, which are involved in visual perception [54], were significantly upregulated in adults. These findings expand our understanding of adaptations for predation and pollination in the hoverfly E. corollae.

E. corollae digests aphids as the primary food source of larvae, and the diversity of its digestive enzymes should approximately match the composition of its diet as found for other insects [55]. For example, fewer genes related to digestion were identified in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens, which has a simple diet, phloem sap [56]. In our study, E. corollae also had fewer digestion-related genes compared with other dipteran species, also likely due to its simple aphid diet, in contrast to the broad diet of polyphagous insect species [38]. For example, SPs are significantly abundant in the omnivorous pest A. lucorum [38]. In addition, insects can regulate the expression of digestive enzymes homeostatically. In Drosophila, the activity of amylase in larvae is significantly higher when they feed on starch diets compared with sugar diets [57]. Our transcriptomic sequencing showed that more trypsins were highly expressed in larvae of E. corollae, consistent with the fact that aphid composition is more complex, including proteins, starches, and lipids, compared to the adult diet of sugar-rich nectar. Comparative genomic analyses of E. corollae and other aphidophagous hoverflies highlighted three homologous trypsins and their strong expression at the larval stage additionally supported their potential role in aphid digestion. In addition, microbial endosymbionts, mainly bacteria, might also have important roles in nutrient metabolism [58, 59], which will be examined in further research.

In summary, we have provided insights into the genetic basis of predation and pollination by E. corollae, an efficient aphid predator. The chromosome-level genomic and transcriptomic data for E. corollae are valuable resources for advancing studies on genetic adaptations, evolution, and its use as a beneficial insect.

Conclusions

E. corollae and other hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) are important pollinators of many plants and promising biological control agents for controlling aphid pests worldwide. In this study, we present a chromosome-level genome assembly of the hoverfly E. corollae to elucidate the genetic basis of predatory adaptation and pollination in insects. Comparative genomic analysis shed light on three takeout genes, which are related to circadian rhythms and feeding behavior and induced by starvation. Genes for sugar symporter and lipid transport involved in sugar transport and energy production were also present in E. corollae similar to the genome of honeybees, reflecting the important pollinator role of hoverflies. Seven P450s from the cytochrome CYP6 subfamily were expanded in the E. corollae, which might improve detoxification capacity. Furthermore, comparative genomic analysis between E. corollae and S. pyrastri identified four trypsins, three of which (Ecor12299, Ecor12301, Ecor2966) were expressed strongly in larvae, supporting their role in aphid digestion by E. corollae. These results of E. corollae lay the foundation for in-depth research of E. corollae and analyses of predation and pollination in hoverflies and other natural enemies.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation and genome sequencing

E. corollae adults were collected in Langfang, Hebei Province, China, in 2015 and reared in the lab at 23 ± 1 °C with 14 h light:10 h dark. After egg hatching, the larvae were fed with aphids on bean plants, and emerging adults were provided with pollen and honey [22]. An inbred strain (Ec2018), produced by single-pair sib matings for five generations, was used to sequence the genome and transcriptome. For PacBio sequencing, genomic DNA was extracted from a pooled sample of five female adults. A long library with an insert size of ~ 20 kb was constructed and sequenced on six cells using a PacBio RS II system (Pacific Biosciences). A DNA library with a short insert size (400–500 bp) from one female adult was constructed without PCR and sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform. We obtained a 17 k-mer depth distribution using Jellyfish [60] based on the Illumina data and estimated the size and heterozygosity of the E. corollae genome using GenomeScope [61].

The Hi-C library was constructed using 10 female adults. The sample was fixed with 2% v/v formaldehyde for cross-linking. After cross-linking completely, the sample was lysed. The chromatin was digested with the restriction enzyme DpnII and labeled with biotin and ligated. DNA was extracted and purified to obtain a Hi-C sample. After biotin-removed, blunt end-repaired, A-tailed, and adaptor ligation, the Hi-C library was amplified by PCR to obtain the library products. Hi-C libraries were constructed and sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform.

Transcriptomic sequencing and analysis

Samples at different developmental stages (30 eggs, 30 first instar larvae, 3 s instar larvae, 3 third instar larvae, 3 pupae, and 3 adults per group) and tissues from female adults (including 3-day-old heads, 3-day-old bodies, and 5-day-old heads, n = 3 per group) were collected and used to extract total RNA using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). The purity and concentration were determined with a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) and 4200 Bioanalyzer (Agilent), respectively. Then, cDNA libraries were constructed using high-quality RNA and sequenced using an Illumina NovaSeq platform. There were three groups for each sample.

After sequencing, raw reads were first filtered by removing adaptor, duplicated, and low-quality sequences. The resulting clean reads were aligned with the E. corollae genome assembly using HISAT2 [62]. The transcript levels of genes in each sample were quantified using HiSeq and normalized to fragments per kilobase per million reads (FPKM) values. Then, edgeR [63] was used for differential expression analysis of genes. Genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 and log2 |FoldChange|> 1 were considered as differentially expressed [64].

Genome assembly

The adapter and low-quality sequences of Illumina raw reads were trimmed using in-house software clean_adapter (version 1.1) and clean_lowqual (version 1.0) to generate clean reads. The PacBio raw reads were initially processed to correct errors and trim short reads (< 5 kb) using CANU (version 1.8) [65]. Then, PacBio clean reads were used for contig genome assembly with wtdbg2 (version 2.4) [15]. To polish the genome, we aligned the PacBio raw reads with the assembly and corrected errors using FinisherSC (version 2.1) [66] (https://github.com/kakitone/finishingTool). In addition, the Illumina clean reads were aligned with the genome using bowtie2 (version 2.4.1) [67] (https://github.com/BenLangmead/bowtie2), and single-base errors were corrected using pilon (version 1.23) [68] (https://github.com/broadinstitute/pilon). We mapped the Illumina clean reads to the genome assembly to calculate the mapping rate and the depth of genome coverage using BWA (version 0.7.12) [69]. The completeness of the genome was assessed using BUSCO (version 3.1.0) by searching against insecta_odb9 data sets.

After quality control, the Hi-C library was constructed and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq system and PE150 strategy. After sequencing, adapter and low-quality sequences were filtered out from Hi-C raw reads. The resulting high-quality reads were then mapped to the genome with BWA (version 0.7.12), and invalid read pairs were filtered. The valid Hi-C data were used for scaffolding the contig assembly using ALLHiC [70] with default parameters (except for -e GATC -k 4).

Gene prediction and annotation

Repeat sequences in the assembly were predicted using two methods: homology-based and de novo predictions. RepeatMasker (version 4.0.3) was used for homology-based predictions with the Repbase library. A de novo repeat database for E. corollae was built for de novo predictions using RepeatModeler (version 1.0.8).

Based on the repeat-masked genome, we predicted gene models by combining evidences from de novo gene prediction, homology searching, and transcriptome sequencing using BRAKER2 (version 2.1.5). For RNA-seq annotation, six data sets from the different developmental stages were mapped to the genome using STAR v2.7.1a with default parameters [71]. For homology searches, proteins from the NCBI Diptera UniRef50 database were aligned to the E. corollae genome by GenomeThreader v1.7.1 [72]. Based on the alignment results, GeneMark-ET [73] was used to generate the initial gene structures. Then, AUGUSTUS v2.5.5 [74] was used to produce the final gene predictions using the initial gene models. The protein sequences of predicted genes were used in searches of the Swiss-Prot, NR, eggNOG, and KEGG databases for functional annotation using DIAMOND (version 0.8.28) with an e-value cutoff of 1e − 5.

Comparative genomics analysis

Protein sequences of 15 representative dipteran species with high-quality genomes including A. aegypti, Anopheles darlingi, A. gambiae, Anopheles sinensis, Bactrocera dorsalis, Ceratitis capitata, Culex quinquefasciatus, D. melanogaster, Lucilia cuprina, Musca domestica, Stomoxys calcitrans, Eristalis dimidiate, Eristalis tenax, S. pyrastri, and Syritta pipiens, and three coleopteran species including C. septempunctata, H. axyridis, and P. japonica. Hymenopteran species A. mellifera and A. cerana were used as outgroups. All sequences for the comparative analyses were downloaded from NCBI databases. Redundant alternative splicing events were filtered to keep the longest transcript for each gene. OrthoFinder v2.3.1 [75] was adopted to identify orthologous and paralogous genes. Protein sequences of single-copy genes were used for multiple sequence alignments using MAFFT v7 [76]. TrimAL v1.2 [77] was used to trim sequences, extract the conserved region, and concatenate all single-copy genes into a super-sequence, which was used for a maximum likelihood (ML) tree construction. The phylogenetic analysis was performed using IQ-TREE (version 1.5.5) with model selection across each partition and 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates. The divergence time was estimated using r8s (version 1.81) [78] based on fossil calibration points. The estimated divergence time between A. aegypti and C. quinquefasciatus was 75 Mya and 37 Mya between M. domestica and S. calcitrans.

Orthologous groups of each species were generated by OrthoFinder with default parameters. We manually identified the predicted orthogroups between E. corollae and S. pyrastri, which were not found in other species. To predict genes related to predation, the manually curated orthogroups between E. corollae plus three ladybugs did not contain honeybee homologs. Similarly, to predict genes related to pollination, we manually identified homologous genes shared by E. corollae plus two honeybees, which were absent from ladybugs. The homologous genes were further used for GO enrichment analysis for functional annotation.

Gene family analysis

We manually annotated detoxification-related and chemosensory-related gene families. For these gene families, protein sequences of dipteran species were downloaded from NCBI and aligned with the E. corollae genome using TBLASTN (e-value = 1e − 5). Then, hidden Markov models (HMMs) of P450s (PF00067), GST (PF13417, PF02798, PF00043, PF14497, or PF13410), IRs (PF10613 or PF00060), GRs (PF06151 or PF08395), ORs (PF02949 or PF13853), OBPs (PF01395), CSPs (PF03392), and SNMPs (PF01130) were downloaded from the Pfam database, and HMMER (version 3.3) was used to identify the candidate genes [79]. A neighbor-joining (NJ) phylogenetic tree for each gene family was constructed in MEGA7 [80] with 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Statistics for sequencing data. Table S2. Summary of statistics for Eupeodes corollae chromosomes. Table S3. BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologues) assessment of Eupeodes corollae genome using insecta_odb9 data sets (n = 1,658). Table S4. Characteristics of transposable elements in Eupeodes corollae. Fig. S1. Distribution of 17-mer frequency of Illumina sequencing reads of Eupeodes corollae. Fig. S2. Venn plot of functional annotations for predicted proteins of Eupeodes corollae. Fig. S3. The number of the orthologous groups shared between Eupeodes corollae and other species by OrthoFinder analysis. Fig. S4. Distribution of cytochrome P450 genes on the four chromosomes of Eupeodes corollae.

Additional file 2: Table S5. GO enrichment analysis of Syrphidae-specific genes (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S6. GO enrichment analysis of species-specific genes of Eupeodes corollae (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S7. GO enrichment analysis of the homologous genes shared between Eupeodes corollae and Scaeva pyrastri (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S8. GO enrichment analysis of the homologous genes shared between Eupeodes corollae and ladybugs (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S9. GO enrichment analysis of the homologous genes shared between Eupeodes corollae and honeybees (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S10. Differentially expressed genes in adults compared to larvae stage in Eupeodes corollae.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Weihua Ma at Huazhong Agricultural University for his great suggestions for revising the manuscript. We thank Dr. Hangwei Liu and Weigang Zheng at the Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, for their help in the data analyses.

Abbreviations

- BUSCO

Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs

- LINEs

Long interspersed elements

- SPs

Serine proteases

- OBPs

Odorant-binding proteins

- CSPs

Chemosensory proteins

- ORs

Odorant receptors

- IRs

Ionotropic receptors

- GRs

Gustatory receptors

- SNMPs

Sensory neuron membrane proteins

- GSTs

Glutathione S-transferases

- OSNs

Olfactory sensory neurons

- iGluRs

Ionotropic glutamate receptor superfamily

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase per million reads

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GO

Gene Ontology

- HMMs

Hidden Markov models

Authors’ contributions

K.W. and Y.X. conceived, designed, and led the project. H.L. prepared the samples for sequencing. H.Y., B.G., and C.W. assembled the genome and generated the gene set. H.Y. annotated the gene families. H.Y. analyzed the transcriptome and wrote the manuscript. H.Y., L.Z., Y.X., and K.W. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by The Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (2020CXGC010802), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural and Sciences, Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20200109150629266, JCYJ20190813115612564), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001944). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and supplementary information files. All the raw sequencing data and genome data in this study have been deposited at NCBI as a BioProject under accession PRJNA746055 [81]. Genomic sequence reads have been deposited in the SRA database as BioSample SAMN20179301 [82]. Transcriptome sequence reads have been deposited in the SRA database as BioSample SAMN20169051 [83]. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession JAIWPZ000000000 [84]. The version described in this paper is version JAIWPZ010000000.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

He Yuan, Bojia Gao, and Chao Wu contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yutao Xiao, Email: xiaoyutao@caas.cn.

Kongming Wu, Email: wukongming@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Moerkens R, Boonen S, Wäckers FL, Pekas A. Aphidophagous hoverflies reduce foxglove aphid infestations and improve seed set and fruit yield in sweet pepper. Pest Manag Sci. 2021;77:2690–2696. doi: 10.1002/ps.6342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunn L, Lequerica M, Reid CR, Latty T. Dual ecosystem services of syrphid flies (Diptera: Syrphidae): pollinators and biological control agents. Pest Manag Sci. 2020;76:1973–1979. doi: 10.1002/ps.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wotton KR, Gao B, Menz MHM, Morris RKA, Ball SG, Lim KS, et al. Mass seasonal migrations of hoverflies provide extensive pollination and crop protection services. Curr Biol. 2019;29:2167–73.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verheggen FJ, Arnaud L, Bartram S, Gohy M, Haubruge E. Aphid and plant volatiles induce oviposition in an aphidophagous hoverfly. J Chem Ecol. 2008;34:301–307. doi: 10.1007/s10886-008-9434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilka V, Jonathan G, Grit K. Dealing with food shortage: larval dispersal behaviour and survival on non-prey food of the hoverfly Episyrphus balteatus. Ecol Entomol. 2018;43:578–590. doi: 10.1111/een.12636. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadeghi H, Gilbert F. Aphid suitability and its relationship to oviposition preference in predatory hoverflies. J Anim Ecol. 2000;69:771–784. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rader R, Bartomeus I, Garibaldi LA, Garratt MP, Howlett BG, Winfree R, et al. Non-bee insects are important contributors to global crop pollination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:146–151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517092112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rader R, Cunningham SA, Howlett BG, Inouye DW. Non-bee insects as visitors and pollinators of crops: biology, ecology, and management. Annu Rev Entomol. 2020;65:391–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao B, Wotton KR, Hawkes WLS, Menz MHM, Reynolds DR, Zhai BP, et al. Adaptive strategies of high-flying migratory hoverflies in response to wind currents. Proc Biol Sci. 2020;287:20200406. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle T, Hawkes WLS, Massy R, Powney GD, Menz MHM, Wotton KR. Pollination by hoverflies in the Anthropocene. Proc Biol Sci. 2020;287:20200508. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.0508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dällenbach LJ, Glauser A, Lim KS, Chapman JW, Menz MHM. Higher flight activity in the offspring of migrants compared to residents in a migratory insect. Proc Biol Sci. 2018;285:20172829. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menz MHM, Brown BV, Wotton KR. Quantification of migrant hoverfly movements (Diptera: Syrphidae) on the West Coast of North America. R Soc Open Sci. 2019;6:190153. doi: 10.1098/rsos.190153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biesmeijer JC, Roberts SP, Reemer M, Ohlemüller R, Edwards M, Peeters T, et al. Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science. 2006;313:351–354. doi: 10.1126/science.1127863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powney GD, Carvell C, Edwards M, Morris RKA, Roy HE, Woodcock BA, et al. Widespread losses of pollinating insects in Britain. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1018. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08974-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruan J, Li H. Fast and accurate long-read assembly with wtdbg2. Nat Methods. 2020;17:155–158. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0669-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyes JW, Van Brink J. Chromosomes of Syrphidae. I. variations in karyotype. Chromosoma. 1964;15:579–90. doi: 10.1007/BF00319992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan PL, Ye YX, Lou YH, Lu JB, Cheng C, Shen Y, et al. A comprehensive omics analysis and functional survey of cuticular proteins in the brown planthopper. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:5175–5180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716951115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karouzou MV, Spyropoulos Y, Iconomidou VA, Cornman RS, Hamodrakas SJ, Willis JH. Drosophila cuticular proteins with the R&R Consensus: annotation and classification with a new tool for discriminating RR-1 and RR-2 sequences. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:754–760. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon JY, Dahanukar A, Weiss LA, Carlson JR. The molecular basis of CO2 reception in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3574–3578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700079104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robertson HM, Kent LB. Evolution of the gene lineage encoding the carbon dioxide receptor in insects. J Insect Sci. 2009;9:19. doi: 10.1673/031.009.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarov-Blat L, So WV, Liu L, Rosbash M. The Drosophila takeout gene is a novel molecular link between circadian rhythms and feeding behavior. Cell. 2000;101:647–656. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80876-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng F, Cohen AC. Comparison of alpha-amylase and protease activities of a zoophytophagous and two phytozoophagous Heteroptera. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2000;126:101–106. doi: 10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y, Liu H, Wang H, Huang T, Liu B, Yang B, et al. Apolygus lucorum genome provides insights into omnivorousness and mesophyll feeding. Mol Ecol Resour. 2021;21:287–300. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia HR, Sun YF, Luo SP, Wu KM. Characterization of antennal chemosensilla and associated odorant binding as well as chemosensory proteins in the Eupeodes corollae (Diptera: Syrphidae) J Insect Physiol. 2019;113:49–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang B, Liu Y, Wang GR. Chemosensory genes in the antennal transcriptome of two syrphid species, Episyrphus balteatus and Eupeodes corollae (Diptera: Syrphidae) BMC Genomics. 2017;18:586. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3939-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bargen H, Saudhof K. Hanscmichael Poehling. Prey finding by larvae and adult females of Episyrphus balteatus. Entomol Exp Appl. 2010;87:245–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1570-7458.1998.00328.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinker DC, Zhou X, Pitts RJ, AGC Consortium. Rokas A, Zwiebel LJ. Antennal transcriptome profiles of anopheline mosquitoes reveal human host olfactory specialization in Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:749. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robertson HM, Warr CG, Carlson JR. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 2):14537–14542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersson MN, Christer L, Newcomb RD. Insect olfaction and the evolution of receptor tuning. Front Ecol Evol. 2015;3:53. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wicher D, Schäfer R, Bauernfeind R, Stensmyr MC, Heller R, Heinemann SH, et al. Drosophila odorant receptors are both ligand-gated and cyclic-nucleotide-activated cation channels. Nature. 2008;452:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature06861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox AN, Pitts RJ, Robertson HM, Carlson JR, Zwiebel LJ. Candidate odorant receptors from the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae and evidence of down-regulation in response to blood feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14693–14697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261432998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benton R, Vannice KS, Vosshall LB. An essential role for a CD36-related receptor in pheromone detection in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;450:289–293. doi: 10.1038/nature06328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu Y, Cui Z, Si P, Liu Y, Zhou Q, Wang G. Characterization of a specific odorant receptor for linalool in the Chinese citrus fly Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae) Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;122:103389. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jiang NJ, Tang R, Wu H, Xu M, Ning C, Huang LQ, et al. Dissecting sex pheromone communication of Mythimna separata (Walker) in North China from receptor molecules and antennal lobes to behavior. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;111:103176. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pitts RJ, Liu C, Zhou X, Malpartida JC, Zwiebel LJ. Odorant receptor-mediated sperm activation in disease vector mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:2566–2571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322923111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benton R, Vannice KS, Gomez-Diaz C, Vosshall LB. Variant ionotropic glutamate receptors as chemosensory receptors in Drosophila. Cell. 2009;136:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abuin L, Bargeton B, Ulbrich MH, Isacoff EY, Kellenberger S, Benton R. Functional architecture of olfactory ionotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2011;69:44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croset V, Rytz R, Cummins SF, Budd A, Brawand D, Kaessmann H, et al. Ancient protostome origin of chemosensory ionotropic glutamate receptors and the evolution of insect taste and olfaction. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He Z, Luo Y, Shang X, Sun JS, Carlson JR. Chemosensory sensilla of the Drosophila wing express a candidate ionotropic pheromone receptor. PLoS Biol. 2019;17:e2006619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larter NK, Sun JS, Carlson JR. Organization and function of Drosophila odorant binding proteins. Elife. 2016;5:e20242. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pelosi P, Iovinella I, Felicioli A, Dani FR. Soluble proteins of chemical communication: an overview across arthropods. Front Physiol. 2014;5:320. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mao W, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. CYP9Q-mediated detoxification of acaricides in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12657–12662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109535108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu Z, Pu X, Shu B, Bin S, Lin J. Transcriptome analysis of putative detoxification genes in the Asian citrus psyllid. Diaphorina citri Pest Manag Sci. 2020;76:3857–3870. doi: 10.1002/ps.5937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feyereisen R. Insect P450 enzymes. Annu Rev Entomol. 1999;44:507–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dermauw W, Van Leeuwen T, Feyereisen R. Diversity and evolution of the P450 family in arthropods. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;127:103490. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feyereisen R. Evolution of insect P450. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:1252–1255. doi: 10.1042/BST0341252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daborn PJ, Lumb C, Boey A, Wong W, Ffrench-Constant RH, Batterham P. Evaluating the insecticide resistance potential of eight Drosophila melanogaster cytochrome P450 genes by transgenic over-expression. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;37:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Denecke S, Fusetto R, Martelli F, Giang A, Battlay P, Fournier-Level A, et al. Multiple P450s and variation in neuronal genes underpins the response to the insecticide imidacloprid in a population of Drosophila melanogaster. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11338. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salinas AE, Wong MG. Glutathione S-transferases–a review. Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:279–309. doi: 10.2174/0929867306666220208213032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enayati AA, Ranson H, Hemingway J. Insect glutathione transferases and insecticide resistance. Insect Mol Biol. 2005;14:3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedman R. Genomic organization of the glutathione S-transferase family in insects. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;61:924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lumjuan N, Rajatileka S, Changsom D, Wicheer J, Leelapat P, Prapanthadara LA, et al. The role of the Aedes aegypti epsilon glutathione transferases in conferring resistance to DDT and pyrethroid insecticides. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;41:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen M, Mei Y, Chen X, Chen X, Xiao D, He K, et al. A chromosome-level assembly of the harlequin ladybird Harmonia axyridis as a genomic resource to study beetle and invasion biology. Mol Ecol Resour. 2021;21:1318–1332. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Feuda R, Marlétaz F, Bentley MA, Holland PW. Conservation, duplication, and divergence of five opsin genes in insect evolution. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:579–587. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karasov WH, Douglas AE. Comparative digestive physiology. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:741–783. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xue J, Zhou X, Zhang CX, Yu LL, Fan HW, Wang Z, et al. Genomes of the rice pest brown planthopper and its endosymbionts reveal complex complementary contributions for host adaptation. Genome Biol. 2014;15:521. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0521-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inomata N, Nakashima S. Short 5’-flanking regions of the Amy gene of Drosophila kikkawai affect amylase gene expression and respond to food environments. Gene. 2008;412:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alberoni D, Baffoni L, Gaggìa F, Ryan PM, Murphy K, Ross PR, et al. Impact of beneficial bacteria supplementation on the gut microbiota, colony development and productivity of Apis mellifera L. Benef Microbes. 2018;9:269–278. doi: 10.3920/BM2017.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonilla-Rosso G, Engel P. Functional roles and metabolic niches in the honey bee gut microbiota. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2018;43:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2017.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marçais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vurture GW, Sedlazeck FJ, Nattestad M, Underwood CJ, Fang H, Gurtowski J, et al. GenomeScope: fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2202–2204. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 2017;27:722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lam KK, LaButti K, Khalak A, Tse D. FinisherSC: a repeat-aware tool for upgrading de novo assembly using long reads. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3207–3209. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, Sakthikumar S, et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang X, Zhang S, Zhao Q, Ming R, Tang H. Assembly of allele-aware, chromosomal-scale autopolyploid genomes based on Hi-C data. Nat Plants. 2019;5:833–845. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gremme G, Brendel V, Sparks ME, Kurtz S. Engineering a software tool for gene structure prediction in higher organisms. Inform Software Tech. 2005;47:965–978. doi: 10.1016/j.infsof.2005.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lomsadze A, Burns PD, Borodovsky M. Integration of mapped RNA-Seq reads into automatic training of eukaryotic gene finding algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e119. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stanke M, Waack S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl 2):ii215–25. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sanderson MJ. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:301–302. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W29–37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yuan H, et al. Eupeodes corollae, genome sequencing and assembly. NCBI accession: PRJNA746055. (2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA746055.

- 82.Yuan H, et al. MIGS Eukaryotic samples from Eupeodes corollae. NCBI accession: SAMN20179301. (2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biosample/SAMN20179301/.

- 83.Yuan H, et al. RNA-seq sample from Eupeodes corollae. NCBI accession: SAMN20169051. (2021). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biosample/SAMN20169051/.

- 84.Yuan H, et al. Eupeodes corollae HY-2021, whole genome shotgun sequencing project. NCBI accession: JAIWPZ010000000. (2021). https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc:JAIWPZ010000000.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Statistics for sequencing data. Table S2. Summary of statistics for Eupeodes corollae chromosomes. Table S3. BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologues) assessment of Eupeodes corollae genome using insecta_odb9 data sets (n = 1,658). Table S4. Characteristics of transposable elements in Eupeodes corollae. Fig. S1. Distribution of 17-mer frequency of Illumina sequencing reads of Eupeodes corollae. Fig. S2. Venn plot of functional annotations for predicted proteins of Eupeodes corollae. Fig. S3. The number of the orthologous groups shared between Eupeodes corollae and other species by OrthoFinder analysis. Fig. S4. Distribution of cytochrome P450 genes on the four chromosomes of Eupeodes corollae.

Additional file 2: Table S5. GO enrichment analysis of Syrphidae-specific genes (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S6. GO enrichment analysis of species-specific genes of Eupeodes corollae (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S7. GO enrichment analysis of the homologous genes shared between Eupeodes corollae and Scaeva pyrastri (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S8. GO enrichment analysis of the homologous genes shared between Eupeodes corollae and ladybugs (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S9. GO enrichment analysis of the homologous genes shared between Eupeodes corollae and honeybees (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05). Table S10. Differentially expressed genes in adults compared to larvae stage in Eupeodes corollae.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this work are available within the paper and supplementary information files. All the raw sequencing data and genome data in this study have been deposited at NCBI as a BioProject under accession PRJNA746055 [81]. Genomic sequence reads have been deposited in the SRA database as BioSample SAMN20179301 [82]. Transcriptome sequence reads have been deposited in the SRA database as BioSample SAMN20169051 [83]. This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession JAIWPZ000000000 [84]. The version described in this paper is version JAIWPZ010000000.