Abstract

An embryonic cell line (DAE100) of the Rocky Mountain wood tick, Dermacentor andersoni, was observed by microscopy to be chronically infected with a rickettsialike organism. The organism was identified as a spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsia by PCR amplification and sequencing of portions of the 16S rRNA, citrate synthase, Rickettsia genus-specific 17-kDa antigen, and SFG-specific 190-kDa outer membrane protein A (rOmpA) genes. Sequence analysis of a partial rompA gene PCR fragment and indirect fluorescent antibody data for rOmpA and rOmpB indicated that this rickettsia was a strain (DaE100R) of Rickettsia peacockii, an SFG species presumed to be avirulent for both ticks and mammals. R. peacockii was successfully maintained in a continuous culture of DAE100 cells without apparent adverse effects on the host cells. Establishing cell lines from embryonic tissues of ticks offers an alternative technique for isolation of rickettsiae that are transovarially transmitted.

Rickettsiae are obligately intracellular gram-negative bacteria, some of which are pathogens of arthropods and mammals (5). The genus Rickettsia includes the spotted fever group (SFG) rickettsiae that are dependent on acarines for propagation and maintenance in nature (7). Ticks can serve as vectors for mammalian pathogenic SFG rickettsiae, as well as maintenance hosts for SFG rickettsiae that are transmitted transstadially and transovarially via female germinal tissues. The latter group includes those SFG rickettsiae which have been isolated only from ticks and which may be beneficial for the ticks that harbor them (3, 21, 23, 34). Stable maintenance of these rickettsiae within tick populations is postulated to occur solely via transovarial transmission from one generation to the next (8). Such rickettsiae may benefit the tick by antagonizing superinfection of the host tick by closely related species that are pathogenic for ticks (2). Many of these rickettsiae remain poorly characterized due to our inability to maintain them in mammalian cell culture, embryonated chicken eggs, or small rodents, which have traditionally been the standard maintenance hosts used in rickettsiology (5). Tick cell culture offers an alternative approach for propagation and study of these organisms (17).

The east side agent, recently classified and designated Rickettsia peacockii (22), has been reported to be noninfectious for meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and Swiss mice (Mus musculus) (22). R. peacockii is beneficial for its maintenance host, the Rocky Mountain wood tick, Dermacentor andersoni (3). The wood tick is also associated with and transmits pathogenic strains of Rickettsia rickettsii, which causes both Rocky Mountain spotted fever in mammals and increased mortality for its vector host (21). The presence of R. peacockii within ovaries of D. andersoni interferes with the ability of virulent R. rickettsii to infect the ovarian tissues and to be transovarially transmitted to progeny (3). Previous attempts to cultivate R. peacockii in vitro were unsuccessful (3, 22). In addition, prior attempts to isolate D. andersoni cell lines for the purpose of propagating microbes associated with this tick species have been unsuccessful as well (37).

In this report, we describe isolation, propagation, and partial characterization of R. peacockii in a D. andersoni cell line (DAE100). This was achieved by establishing cell lines from the embryonic tissues of laboratory-reared D. andersoni ticks chronically infected with R. peacockii.

(This research was conducted by Jason A. Simser in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota, St. Paul.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Establishment and maintenance of D. andersoni cell line DAE100.

Cell line DAE100 was isolated from eggs laid by mated and engorged D. andersoni ticks from a laboratory colony maintained at Oklahoma State University and kindly supplied by Katherine Kocan. The colony had been initiated with ticks collected from north central Colorado at a location 5 miles west of Rustic, Colo. (40°41.897′N, 105°37.362′W) (W. C. Black IV, University of Colorado, personal communication). Primary cultures of embryonic tissues were initiated 25 to 30 days after the onset of oviposition (18). Embryonic tissues were inoculated into 25-cm2 culture flasks (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) and incubated at 34°C. Each flask contained 5 ml of L15B medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (20% for the first week and 5% thereafter), tryptose phosphate broth (10%), and bovine lipoprotein concentrate (1%) (18). The pH of the complete medium was adjusted to 6.8 to 7.0 with 1 N NaOH. Antibiotics (50 μg of gentamicin per ml, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin sulfate per ml) were used when the primary culture was initiated. After 2 weeks, the medium was replaced weekly with antibiotic-free complete medium. Subcultures were made when cells reached confluency by transferring one-half to one-tenth of resuspended cell preparations to new culture flasks containing 2.5 to 4.5 ml of fresh media (final volume, 5 ml).

Portions of the egg masses used to initiate primary cultures were set aside and stored at −70°C, and they were used later for isozyme and PCR analyses (see below).

Microorganisms.

A rickettsia, initially referred to as DaE100R and later identified as R. peacockii, was maintained in cell line DAE100 in complete medium. R. rickettsii Hlp(#2), isolated from a Heamaphysalis leporispalustris tick (kindly provided by Robert Heinzen, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institutes of Health), was propagated in Ixodes scapularis cell line IDE2 (18). A Francisella sp. isolated from the soft tick Argas persicus and named “Wolbachia persica” (31) (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection as strain ATCC VR-331) was grown axenically in complete tick cell culture medium (23).

Microscopy.

Tick cell morphology and culture confluency were determined by phase-contrast microscopy. The proportion of cells infected with rickettsialike organisms was quantified by light microscopy by using Giemsa-stained cells. For light microscopy, cells were centrifuged at 60 × g for 5 min onto glass microscope slides by using a Cytospin centrifuge (Shandon Southern Instruments, Sewickley, Pa.), air dried, fixed with methanol, and stained with Giemsa stain.

Cells were prepared at passage 14 for electron microscopy as described by Munderloh et al. (15).

Isozyme analysis.

We confirmed that cell line DAE100 cells were D. andersoni cells by performing isoelectric focusing of lactate dehydrogenases (LDH) and malic dehydrogenases (MDH) under nondenaturing conditions in polyacrylamide gels as described previously (18).

DNA isolation and preparation.

Rickettsial DNA was extracted from infected cell lines (34). Briefly, cells were washed twice in Hanks' balanced saline solution and mechanically ruptured by forcing them through a 27-gauge needle attached to a 5-ml syringe to release the intracellular microbes. To enrich for rickettsiae, large cell fragments and intact tick cells were removed by low-speed centrifugation (275 × g for 10 min). The supernatants were filtered through a 5.0-μm-pore-size filter and centrifuged (14,000 × g for 25 min at 4°C), and DNA was released from the rickettsial pellet using proteinase K (12). The Francisella sp. (“W. persica”) was washed twice in Hanks' balanced salt solution and centrifuged (14,000 × g for 25 min at 4°C), and DNA was extracted as described above for the pelleted filtrates. DNA was extracted from a portion of the D. andersoni eggs used to initiate cell line DAE100 by crushing the cells in proteinase K (12). Samples were stored at −70°C until they were used for PCR.

PCR amplification.

The oligonucleotide primers used in this study (Table 1) were synthesized by Life Technologies (Grand Island, N.Y.). All amplification conditions for all PCR included an initial denaturing step of 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of primer-specific denaturing, annealing, and extension steps and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min (see below). The cycling temperatures used for denaturing, annealing, and primer extension for the individual primer sets were as follows: reaction mixtures containing the Ec16S primer pair (22) were heated at 95°C for 1 min, at 55°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 2 min; the RpCS.877p-RpCS.1258n and Rr190.70p-Rr190.602n primer sets (27) were used with a temperature profile consisting of 95°C for 20 s, 48°C for 30 s, and 60°C for 2 min; the Rr17 primer pair (35) was heated at 94°C for 30 s, at 57°C for 2 min, and at 70°C for 2 min; the F11-F5 primer pair (6) was heated at 94°C for 1 min, at 65°C for 1 min, and at 72°C for 1 min; and for the TUL4-B primer pair (20) the cycles consisted of 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min. PCR were performed in 50-μl reaction mixtures containing template DNA (5 μl) or H2O (negative control), 10× PCR buffer (5 μl), MgCl2 (2.5 mM), a mixture of primers (0.5 μM each), Taq DNA polymerase (2.5 U), and the four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (0.2 μM each). All PCR were carried out with a RoboCycler thermocycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis through 1.5% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized by UV illumination.

TABLE 1.

PCR primer sets used in this study

| Primer set | Species | Gene | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Approx size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ec16S | Escherichia coli | 16S rRNA | GCTTAACACATGCAAG CCATTGTAGCACGCGT | 1,157 | 20 |

| RpCS.877p- RpCS.1258n | Rickettsia prowazekii | Citrate synthase (gltA) | GGGGGCCTGCTCACGGCGG ATTGCAAAAAGTACAGTGAACA | 381 | 27 |

| Rr17 | R. rickettsii | 17-kDa genus-common antigen | GCTCTTGCAACTTCTATGTT CATTGTTCGTCAGGTTGGCG | 434 | 35 |

| Rr190.70p-Rr190.602n | R. rickettsii | 190-kDa antigen (rompA) | ATGGCGAATATTTCTCCAAAA AGTGCAGCATTCGCTCCCCCT | 532 | 27 |

| F11-F5 | Francisella spp. | 16S rRNA | TACCAGTTGGAAACGACTGT CCTTTTTGAGTTTCGCTCC | 1,142 | 6 |

| TUL4-B | Francisella tularensis | 17-kDa membrane protein (TUL4) | GAATATGTCAAAGGTAGG TCAGAAGCGATTACTTCT | 838 | 22 |

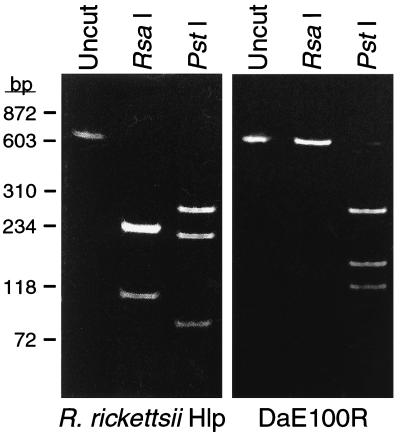

RFLP analysis.

Restriction endonuclease digests of the rompA PCR product obtained from DaE100R by using RsaI and PstI were compared to the restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns previously described for R. peacockii (22). As a control, R. rickettsii Hlp(#2) rompA PCR products were also digested in order to compare restriction profiles. Aliquots (10 μl each) of rompA PCR products (amplified by the Rr190.70p-Rr190.602n primer set) were digested for 4 h at 37°C with 1 μl (10 U) of restriction enzyme Rsal or Pstl and 1 μl of the appropriate buffer (Life Technologies). The digestion products were separated by electrophoresis through an 8% polyacrylamide gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized by UV illumination.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay.

DAE100 cells were reacted with mouse anti-R. rickettsii monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) to test for recognition of rickettsia-specific epitopes on the DaE100R cells (15). IDE2 tick cells infected with R. rickettsii Hlp(#2) were used as MAb-positive controls. Aliquots (10 μl each) of a 5-ml cell suspension were placed onto glass microscope slides and air dried. Samples were fixed, permeabilized, and labeled as described by Heinzen et al. (11). Briefly, cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 min, quenched in a 50 mM NH4Cl solution for 10 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. After a PBS wash, the indirect immunofluorescence assay slides were overlaid with either MAb 13-2 to 120-kDa surface antigen rOmpB or MAb 13-5 to 190-kDa surface antigen rOmpA (1) for 60 min at 37°C. MAbs 13-2 and 13-5 were diluted 1:100 in PBS with 3% bovine serum albumin. Bound MAbs were then labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody to mouse immunoglobulin G (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) for 60 min at 37°C. The slides were examined with an Olympus BH-2 microscope fitted for epifluorescence illumination.

DNA sequencing.

DaE100R 16S rRNA, gltA, 17-kDa, and rompA PCR products were ligated into pGEM-T Easy vectors (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and then transformed into Escherichia coli (Epicurian Coli Supercompetent cells; Stratagene) for cloning as recommended by manufacturers. Three clones of each partial gene PCR product were sequenced in the forward and reverse directions by using an ABI 377 automated sequencer at the Advanced Genetic Analysis Center (University of Minnesota). Final sequences were deduced by aligning the resulting six sequences using the CLUSTAL W multiple-sequence alignment program (32).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the Ec16S, RpCS.877p-RpCS.1258n, Rr17, and Rr190.70p-Rr190.602n PCR products of the DaE100R strain of R. peacockii have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AF097729, AF129885, AF260571, and AF129884, respectively.

RESULTS

Establishment of D. andersoni cell lines infected with endosymbionts.

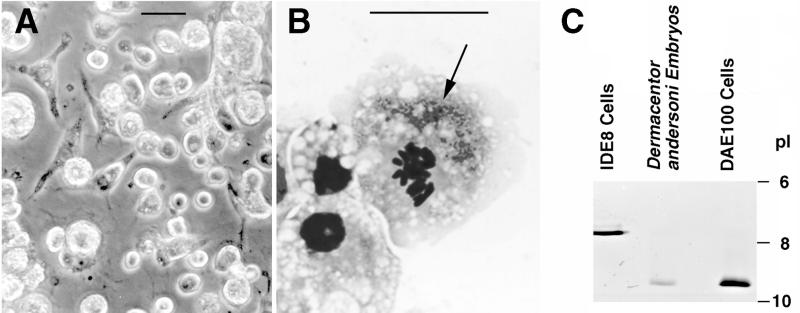

Cell lines were successfully established from embryonic tissues of D. andersoni. After 1 year in culture (passage 8), small bacilliform microbes were observed in one of the young cell lines. As these microbes did not grow in cell-free medium, we suspected that they might be endosymbionts associated with D. andersoni (20, 23), which so far have proven to be refractory to in vitro cultivation. Therefore, we decided to propagate the cell line (DAE100) that was chronically infected with these microbes and to identify them by using molecular methods. Most DAE100 cells adhered to the culture surface and were round and refractile, while other cells were bipolar with prominent pseudopodia and moderately translucent (Fig. 1A). The microbes persisted in the DAE100 cell line for more than 20 additional subcultures (>2 years). Microscopy of Giemsa-stained cells revealed that most (>90%) of the cells were infected with rickettsialike organisms and that some cells were heavily infected (Fig. 1B). The presence of the microorganisms did not have a cytopathic effect on the DAE100 cell line as infected cells were capable of mitosis and were maintained through continuous propagation in culture. In contrast, R. rickettsii Hlp(#2) produced plaques on adherent IDE2 cell cultures and was maintained by weekly transfers of 5% portions of infected cultures, in which approximately 100% of the cells were infected, to fresh cell layers. The isoelectric focusing patterns for LDH and MDH confirmed that the cell line DAE100 cells were D. andersoni cells. The approximate pI for LDH of DAE100 was 9.0 and was identical to the pI for the LDH extracted from embryonic tissues of D. andersoni. This LDH was distinctly different from the LDH of the I. scapularis cell line IDE8 (18) maintained in our laboratory, which had a pI of approximately 7.0 (Fig. 1C). The pI range for the most prominent MDH for both tick species was 8.0 to 9.0. However, the MDH of DAE100 and the embryonic tissue extract had a slightly higher pI than the pI of the MDH from IDE8 cells (18) (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

(A and B) Light photomicrographs showing D. andersoni cell line DAE100. (A) Phase-contrast image of a cell culture. Bar = 25 μm. (B) Giemsa-stained R. peacockii DaE100R-infected DAE100 cell during mitosis. The arrow indicates a cluster of rickettsiae. Bar = 25 μm. (C) Isozyme gel showing approximate pl values of LDH of I. scapularis cell line IDE8, embryonic tissues of D. andersoni, and cell line DAE100 initiated from those tissues.

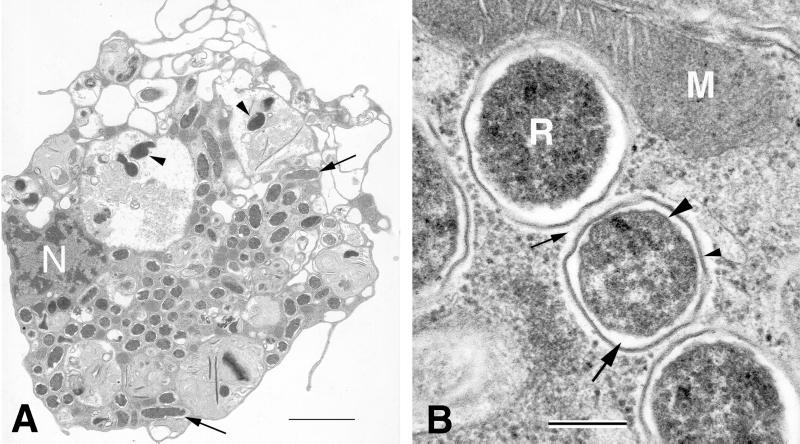

Ultrastructure of DAE100 and its endosymbiont, DaE100R.

Electron microscopy demonstrated that DAE100 cells were infected with rickettsialike bacteria. Infected cells generally had a low nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and prominent cell surface pseudopodia and were often filled with prominent vacuoles (Fig. 2A). Large numbers of the endosymbiont were commonly found in both the cytoplasm and vacuoles of infected cells, as well as the extracellular space. Microbes were concentrated in discrete clusters in the cytoplasm but were not found within the rough endoplasmic reticulum or the nuclei of infected cells. Cytoplasmic DaE100R organisms appeared to be healthy as they divided by binary fission and had a granular central cell body surrounded by a trilaminar cell wall typical of gram-negative organisms. However, the microbes in vacuoles were apparently being digested, as shown by their electron-dense and degraded nature, and were often accompanied by membrane whorls. The cell wall of the microbe consisted of an inner cytoplasmic membrane, a periplasmic space, and an outer membrane with an associated beaded microcapsular layer (Fig. 2B). There was a thin, electron-translucent zone or slime layer outside the outer membrane of the microorganism, which is characteristic of the SFG rickettsiae (9); however, this zone or layer was not always distinguishable.

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron photomicrographs of R. peacockii DaE100R in D. andersoni cell line DAE100. (A) Infected cell with DaE100R in the cytoplasm (arrows), as well as in vacuoles (arrowheads). Bar = 2.0 μm. N, host cell nucleus. (B) Close-up of DaE100R, showing the rickettsial morphology of the organism. Bar = 0.2 μm. R, DaE100R; M, mitochondrion. The large arrowhead indicates the inner cell membrane; the large arrow indicates the periplasmic space; the small arrowhead indicates the outer cell membrane and associated external microcapsular layer; and the small arrow indicates the slime layer.

Molecular confirmation that DaE100R is R. peacockii and that it originated from D. andersoni ticks.

Analysis of PCR products demonstrated that DaE100R was the SFG rickettsia R. peacockii (22). PCR amplification with the eubacterium-specific Ec16S primer set yielded products of the expected sizes (approximately 1,157 bp) and confirmed the bacterial nature of the DAE100 microbe (data not shown). Results obtained with the Rickettsia-specific RpCS.877p-RpCS.1258n (27) and Rr17 (35) primer sets for the citrate synthase (gltA) and 17-kDa genus-common antigen genes, respectively, also placed the DAE100 microbe in the genus Rickettsia. The RpCS.877p-RpCS.1258n and Rr17 primers generated products of the expected sizes (about 381 and 434 bp, respectively) (data not shown). Generation of an approximately 532-bp product when the Rr190.70p-Rr190.602n primer set for the rompA gene was used demonstrated that DaE100R was an SFG rickettsia. The restriction patterns for the rompA product of DaE100R obtained with RsaI (uncut) and PstI (approximately 120, 160, and 250 bp) were identical to those reported for R. peacockii Skalkaho (22) (Fig. 3). The sequences of the Ec16S, RpCS.877p-RpCS.1258n, Rr17, and Rr190.70p-Rr190.602n PCR products of the DaE100R strain of R. peacockii were determined. The partial rompA gene sequence of the DAE100-associated microbe, DaE100R, was identical to that reported for R. peacockii Skalkaho (GenBank accession number U55821). The partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequence of DaE100R differed from that of Skalkaho (GenBank accession number U55820) at 2 of 1,157 nucleotides (substitution of G for T and substitution of A for C at positions corresponding to positions 475 and 533, respectively, on the forward strand of the R. rickettsii 16S rRNA gene).

FIG. 3.

RFLP analysis of the 190-kDa antigen (rompA) gene. PCR rompA products of R. rickettsii Hlp(#2) and R. peacockii DaE100R were not cut or were digested with restriction endonucleases RsaI and PstI. The molecular sizes corresponding to φX174 replicative-form DNA digested with HaeIII (Life Technologies) are indicated on the left.

PCR and RFLP analyses of DNA amplified from D. andersoni eggs with primers Rr190.70p and Rr190.602n and endonucleases RsaI and PstI yielded restriction digests identical to those observed for DaE100R. This result suggested that this strain of R. peacockii originated from the embryonic tissues that we used to initiate the DAE100 cell line.

MAb 13-5, specific for rOmpA, failed to react with the DAE100-associated R. peacockii yet bound to R. rickettsii Hlp(#2). MAb 13-2, specific for the rOmpB protein, bound strongly to both SFG rickettsial isolates (data not shown). These results are identical to those reported for R. peacockii Skalkaho by Niebylski et al. (22).

Dual infections of Rickettsia and Francisella spp. within D. andersoni ticks have been reported (20). Consequently, we used Francisella-specific primers to test for the presence of a Francisella sp. A PCR failed to amplify products when we used template DNA extracted from DAE100 cells and D. andersoni embryonic tissues used to initiate this cell line, which indicated that a Francisella sp. was not present (data not shown). However, the Francisella-specific primer sets produced PCR amplification products when we used the Francisella sp. (“W. persica”) control DNA.

DISCUSSION

Tick cell culture has proven to be a viable means for isolation, maintenance, and subsequent characterization of tick-associated microbes (17). Inoculation of infected cells into established I. scapularis cell lines has resulted in isolation and continuous culture of the equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent, Ehrlichia equi, and the cattle pathogen Anaplasma marginale (14, 19). In addition, tick cell culture has been instrumental in examining the biological processes of tick-borne pathogens important for their survival within and transmission by vector hosts. Elucidation of host cell invasion and intracellular development of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent and modulation of Borrelia burgdorferi virulence factors in ticks have been made possible with tick cell culture techniques (16, 24). The research reported here demonstrates the utility of initiating embryonic cell lines from ticks harboring transovarially transmitted rickettsiae for the purpose of isolating rickettsiae refractory to propagation in traditional vertebrate systems. Our results show that an established D. andersoni cell line, DAE100, was chronically infected with a rickettsia, DaE100R, identical to or closely related to R. peacockii Skalkaho. Furthermore, isozyme analysis of the DAE100 cell line confirmed that D. andersoni was the origin of the cell line. Likewise, RFLP analysis of a rickettsial PCR product amplified from embryonic tissues used to initiate the primary cultures confirmed that D. andersoni was the origin of the DaE100R isolate of R. peacockii.

Mechanisms of rickettsial pathogenesis in cell cultures have been analyzed previously. The Bitterroot and Sheila Smith strains of R. rickettsii disrupted cellular organelles and lysed infected vertebrate cells although the numbers of microbes in the vertebrate cells remained low (28, 36). The cytopathological effects of the Sheila Smith strain for chicken embyro cells included dilation of the rough endoplasmic reticulum and outer nuclear membrane (30, 33). These effects were postulated to have been caused by leakage of extracellular fluids into cells damaged by rickettsial penetration of host cell membranes. The cytopathic effects of the R. rickettsii R strain for both mammalian and tick cells were reported by Policastro et al. (26). Detachment and lysis of the infected tick cells were delayed but did eventually occur (26). We found that the Hlp(#2) strain of R. rickettsii was cytopathic for tick cells and that it infected and lysed Vero cells as well (Simser, unpublished data). Hlp(#2) is infectious for guinea pigs, producing both fever and scrotal swelling in these animals, and for chicken embryos (25). Therefore, we speculate that the mechanisms of pathogenicity of the R. rickettsii strains for tick cells are similar to those demonstrated for vertebrate cells. The in vitro biology of R. peacockii differed strikingly from that of R. rickettsii. R. peacockii cells often packed the cytoplasm of infected cells without any apparent ultrastructural evidence of host cell injury or plaque formation in the adherent DEA100 cell line. Despite high levels of infection (>90%), all indications were that DAE100 cells infected with R. peacockii remained viable. We successfully maintained R. peacockii by passaging the chronically infected cell line DAE100. Infected cells were capable of cytokinesis, and it was never necessary to add fresh, uninfected cells.

SFG rickettsiae utilize host cell actin to penetrate cellular membranes, which causes cell damage and results in cell-to-cell spread in vertebrate cell cultures (10, 29). SFG rickettsiae also polymerize actin in cultured tick cells. Rickettsia sp. strain MOAa and R. rickettsii Hlp(#2) have both been shown to induce actin polymerization in I. scapularis cells (15; Simser, unpublished). The rOmpA protein located on the rickettsial outer membrane is hypothesized to be involved in actin-based motility (4). The slime layer that surrounds the SFG rickettsiae is postulated to contain host cell actin utilized by these organisms for mobility (9, 11, 13). In fact, restoration of pathogenicity to R. rickettsii Wachsmuth 1974 for guinea pigs in feeding ticks has been correlated to expansion of the slime layer of this organism (9). The absence of R. peacockii from host cell rough endoplasmic reticulum and nuclei and the inability of this organism to lyse infected DAE100 cells suggest that this rickettsia is unable to polymerize host cell actin. Microscopic observation indicated that the slime layer of the avirulent organism R. peacockii was very thin and difficult to demonstrate, which may have been due to the lack of host cell actin in this region. R. peacockii has a premature translational stop codon in the 5′ end of the rompA gene that appears to prevent production of a functional rOmpA protein and the ability to bind anti-rOmpA MAb 13-5 (22). In the wood tick, R. peacockii is restricted to the ovaries, posterior diverticula of the midgut, and Malpighian tubule tissues (3, 22). The apparent nonpathogenic nature of R. peacockii and its limited in vivo distribution might in part be a result of a defective rompA gene and an inability to undergo actin-based motility. In vitro cultivation of R. peacockii should allow us to study the mechanisms used by R. peacockii to spread and persist in infected cell cultures and to define the role of the rOmpA protein in rickettsial pathogenesis.

Previous reports have described the presence of R. peacockii in wood ticks collected from the eastern slopes of the Bitterroot Valley of western Montana (3, 22). Isolation of the DaE100R strain of R. peacockii from wood ticks collected in north central Colorado indicates that the distribution of this Rickettsia sp. is wider than previously demonstrated.

Niebylski et al. (20) reported the presence of a D. andersoni symbiont belonging to the genus Francisella in the ovarial cells of wood ticks coinfected with either R. rickettsii or Rickettsia bellii collected in Montana. The overall prevalence and identities of microorganisms belonging to different genera infecting the same cells of a tick remain to be defined. Our inability to detect a Francisella sp. by molecular methods suggests that the D. andersoni colony that was the source of embryonated eggs for the establishment of cell line DAE100 was free of Francisella spp.

Niebylski et al. (22) demonstrated the close relationship of R. peacockii, based on 16S ribosomal DNA and rompA sequence similarity assays, to members of the SFG rickettsiae that are pathogenic for mammals or ticks or both. Nonpathogenic SFG rickettsiae in ticks are speculated to have arisen from pathogenic rickettsiae that over time lost the ability to cause disease in both mammalian and tick hosts (8, 23). Conceivably, this process could be reversed under certain conditions. Therefore, studying the R. peacockii-tick association involves examining the phenomenon of transovarial transmission competition between nonpathogenic and pathogenic rickettsiae in ticks and defining the mechanisms that would allow nonpathogenic organisms to reemerge as pathogens. Moreover, understanding the mechanisms by which ticks and SFG rickettsiae interact should elucidate ways in which the nonpathogenic endosymbionts can be manipulated for control of both the ticks and the pathogens that they harbor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brianna C. Lenox and Thien N. Sam for technical assistance.

This work was supported by state funds from the Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station and a University of Minnesota Graduate School Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship award to Jason A. Simser.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anacker R L, Mann R E, Gonzales C. Reactivity of monoclonal antibodies to Rickettsia rickettsii with spotted fever and typhus group rickettsiae. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:167–171. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.167-171.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azad A F, Beard C B. Rickettsial pathogens and their arthropod vectors. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:179–186. doi: 10.3201/eid0402.980205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burgdorfer W, Hayes S F, Mavros A J. Nonpathogenic rickettsiae in Dermacentor andersoni: a limiting factor for the distribution of Rickettsia rickettsii. In: Burgdorfer W, Anacker R L, editors. Rickettsiae and rickettsial diseases. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 585–594. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charles M, Magdalena J, Theriot J A, Goldberg M B. Functional analysis of a rickettsial OmpA homology domain of Shigella flexneri IcsA. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:869–878. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.3.869-878.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasch G A, Weiss E. The genera Rickettsia, Rochalimaea, Ehrlichia, Cowdria, and Neorickettsia. In: Balows A, Truper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 2407–2470. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsman M, Sandstrom G, Sjostedt A. Analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences of Francisella strains and utilization for determination of the phylogeny of the genus and for identification of strains by PCR. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:38–46. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hackstadt T. The biology of rickettsiae. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:127–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayes S F, Burgdorfer W. Interactions between rickettsial endocytobionts and their tick hosts. In: Schwemmler W, Gassner G, editors. Insect endocytobiosis: morphology, physiology, genetics, evolution. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayes S F, Burgdorfer W. Reactivation of Rickettsia rickettsii in Dermacentor andersoni ticks: an ultrastructural analysis. Infect Immun. 1982;37:779–785. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.2.779-785.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinzen R A, Grieshaber S S, Van Kirk L S, Devin C J. Dynamics of actin-based movement by Rickettsia rickettsii in Vero cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4201–4207. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4201-4207.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinzen R A, Hayes S F, Peacock M G, Hackstadt T. Directional actin polymerization associated with spotted fever group rickettsia infection of Vero cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1926–1935. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1926-1935.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi R. Simple and rapid preparation of samples for PCR. In: Ehrlich H A, editor. PCR technology, principles and applications for DNA amplification. New York, N.Y: Stockton Press; 1989. pp. 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maupin-Szamier P, Pollard T D. Actin filament destruction by osmium tetroxide. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:837–852. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.3.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munderloh U G, Blouin E F, Kocan K M, Ge N L, Edwards W L, Kurtti T J. Establishment of the tick (Acari: Ixodidae)-borne cattle pathogen Anaplasma marginale (Rickettsiales: Anaplasmataceae) J Med Entomol. 1996;33:656–664. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munderloh U G, Hayes S F, Cummings J, Kurtti T J. Microscopy of spotted fever rickettsia movement through tick cells. Microsc Microanal. 1998;4:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munderloh U G, Jauron S D, Fingerle V, Leitritz L, Hayes S F, Hautman J M, Nelson C M, Huberty B W, Kurtti T J, Ahlstrand G G, Greig B, Mellencamp M A, Goodman J L. Invasion and intracellular development of the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent in tick cell culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2518–2524. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2518-2524.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munderloh U G, Kurtti T J. Cellular and molecular interrelationships between ticks and prokaryotic tick-borne pathogens. Annu Rev Entomol. 1995;40:221–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.40.010195.001253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munderloh U G, Liu Y, Wang M, Chen C, Kurtti T J. Establishment, maintenance and description of cell lines from the tick Ixodes scapularis. J Parasitol. 1994;80:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munderloh U G, Madigan J E, Dumler J S, Goodman J L, Hayes S F, Barlough J E, Nelson C M, Kurtti T J. Isolation of the equine granulocutic ehrlichiosis agent, Ehrlichia equi, in tick cell culture. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:664–670. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.3.664-670.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niebylski M L, Peacock M G, Fischer E R, Porcella S F, Schwan T G. Characterization of an endosymbiont infecting wood ticks, Dermacentor andersoni, as a member of the genus Francisella. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3933–3940. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3933-3940.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niebylski M L, Peacock M G, Schwan T G. Lethal effect of Rickettsia rickettsii on its tick vector (Dermacentor andersoni) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:773–778. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.773-778.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niebylski M L, Schrumpf M E, Burgdorfer W, Fischer E R, Gage K L, Schwan T G. Rickettsia peacockii sp. nov., a new species infecting wood ticks, Dermacentor andersoni, in western Montana. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:446–452. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noda H, Munderloh U G, Kurtti T J. Endosymbionts of ticks and their relationship to Wolbachia spp. and tick-borne pathogens of humans and animals. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3926–3932. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.10.3926-3932.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obonyo M, Munderloh U G, Fingerle V, Wilske B, Kurtti T J. Borrelia burgdorferi in tick cell culture modulates expression of outer surface proteins A and C in response to temperature. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2137–2141. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.7.2137-2141.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parker R R, Pickens E G, Lackman D B, Bell E J, Thraikill F B. Isolation and characterization of Rocky Mountain spotted fever rickettsiae from the rabbit tick Heamaphysalis leporispalustris Packard. Public Health Rep. 1951;66:455–463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Policastro P F, Munderloh U G, Fischer E R, Hackstadt T. Rickettsia rickettsii growth and temperature-inducible protein expression in embryonic tick cell lines. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:839–845. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-10-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regnery R L, Spruill C L, Plikaytis B D. Genotypic identification of rickettsiae and estimation of intraspecies sequence divergence for portions of two rickettsial genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1576–1589. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1576-1589.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schaechter M, Bozeman F M, Smadel J E. Study on the growth of rickettsiae. II. Morphologic observations of living rickettsiae in tissue culture cells. Virology. 1957;3:160–172. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(57)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman D J. Rickettsia rickettsii: an engimatic pathogen. In: Moulder J W, editor. Intracellular parasitism. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman D J, Wisseman C L. In vitro studies of rickettsia-host cell interactions: ultrastructural changes induced by Rickettsia rickettsii infection of chicken embryo fibroblasts. Infect Immun. 1979;26:714–727. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.2.714-727.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suitor E C, Weiss E. Isolation of a rickettsialike microorganism (Wolbachia persica, n. sp.) from Argus persicus (Oken) J Infect Dis. 1961;108:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker D H, Cain B G. The rickettsial plaque. Evidence for direct cytopathic effect of Rickettsia rickettsii. Lab Invest. 1980;43:388–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weller S J, Baldridge G D, Munderloh U G, Noda H, Simser J, Kurtti T J. Phylogenetic placement of rickettsiae from the ticks Amblyomma americanum and Ixodes scapularis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1305–1317. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.5.1305-1317.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams S G, Sacci J B, Schriefer M E, Anderson E M, Fujioka K K, Sorvillo F J, Barr A R, Azad A F. Typhus and typhuslike rickettsiae associated with opossums and their fleas in Los Angeles county, California. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1758–1762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1758-1762.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wisseman C L, Edlinger E A, Waddell A D, Jones M R. Infection cycle of Rickettsia rickettsii in chicken embryo and L-929 cells in culture. Infect Immun. 1976;14:1052–1064. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.4.1052-1064.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yunker C E. Preparation and maintenance of arthropod cell cultures: acari, with emphasis on ticks. In: Yunker C E, editor. Arboviruses in arthropod cells in vitro. Vol. 1. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1987. pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]