Executive Summary

The Stanford-Lancet Commission on the North American Opioid Crisis was formed in response to the soaring opioid-related morbidity and mortality that the United States (USA) and Canada have experienced over the past 25 years. The Commission is supported by Stanford University and brings together diverse Stanford scholars with other leading experts around the USA and Canada with the goal of understanding the opioid crisis and proposing solutions to it domestically while attempting to stop its spread internationally.

Unlike some other Lancet Commissions, this one focuses on a long-entrenched problem that has already been well-characterized, including in multiple National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine reviews.1–3 The Commission therefore focused on developing a coherent, empirically grounded analysis of the causes of and solutions to the opioid crisis.

The North American crisis emerged when insufficient regulation of the pharmaceutical and health care industries facilitated a profit-driven quadrupling of opioid prescribing.4–7 This involved a departure from long-established practice norms, particularly in the expanded prescribing of extremely potent opioids for a broad range of chronic non-cancer pain conditions.8–10 Hundreds of thousands of individuals fatally overdosed on prescription opioids, and millions more became addicted or were harmed in other ways, including disability, family breakdown, crime, unemployment, and bereavement.11–14 In response to the large pool of individuals who were addicted to prescription opioids, heroin markets expanded, increasing morbidity and mortality further.15,16 As heroin markets became saturated with illicit synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, an already horrific situation became a public health catastrophe that has only worsened since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.17–21 Since 1999, more than 600,000 people in the USA and Canada have died from an opioid overdose, and the rate of mortality in each country exceeds that of the worst of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.14,21–24

The first wave of the opioid crisis began in the 1990s when the long-acting opioid OxyContin and other high potency opioids were employed for an extremely wide array of patients.4 The first wave inflicted the most harm on white and indigenous people in both the USA and Canada.25–27 An unusually high number of middle-class people and people living in selected rural areas (e.g., Appalachia in the USA, The Yukon in Canada) were affected relative to prior epidemics of opioid addiction and overdose.26,28 The second wave, as heroin markets became resurgent in response to demand from individuals addicted to prescription opioids, began around 2010 and led to rapidly rising mortality among African Americans in the USA, and more generally in urban areas in the USA and Canada.29,30 These demographic shifts persisted into the third wave of the crisis, which began around 2014.14,26,30 This wave was characterized by rising addiction and fatal overdoses involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.17,31 2020 was the worst year on record in both countries: Canada saw a 62% increase in fatal opioid overdoses since 2019 (to 6214 deaths) and preliminary data from the USA suggests a 33% increase (to 69,710 deaths).21,32 Each wave added to rather than replaced the prior waves, with addiction and overdoses continuing among individuals using any or all of prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl.14,21

In both the USA and Canada, fatal opioid overdoses are concentrated among men and young to middle-aged people.14,21 The mortality rate among African Americans in the USA has grown rapidly and is now on par with that of whites and American Indians and Alaska Natives.14 People experiencing homelessness and those recently released from incarceration have been particularly hard hit throughout the crisis and continue to face shockingly high overdose mortality rates.33–36 Overdoses involving both stimulants and opioids is common and seems to be increasing in both the USA and Canada.21,37 A significant number of opioid overdoses also involve concurrent use of benzodiazepines.38

The Commission’s analysis of the crisis focused on seven domains: (1) the North American opioid crisis as a case study in multi-system regulatory failure; (2) opioids’ dual nature as a benefit and a risk to health; (3) building integrated, well-supported and enduring systems for the care for people with substance use disorders; (4) maximizing the benefit and minimizing the adverse effects of criminal justice system involvement of people who are addicted to opioids; (5) creating healthy environments that can yield long-term declines in the incidence of addiction; (6) stimulating greater innovation in the response to the opioid crisis; and (7) preventing the North American opioid crisis from spreading globally. In each area, the Commission recommends evidence-informed policies that are responsive to identified challenges.

Domain 1.

The Commission concludes that the initial wave of the opioid crisis arose from weak laws and regulations as well as poor implementation of these laws and regulations.5 This included failures at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration which approved OxyContin with what was later shown to be a fraudulent description of the drug as less addictive.4 Further problems arose from overly cozy relationships between opioid manufacturers with universities, professional societies, patient advocacy groups, and lawmakers; and aggressive product promotion to prescribers and, to a lesser extent, the general public.39–42 These problems were compounded by the limited tools regulators have post-approval, particularly given that the law in the USA makes government largely dependent on the pharmaceutical industry to conduct adequate post-approval surveillance and to provide risk management education to prescribers, which the industry does poorly.43,44 The Commission therefore recommends curtailing pharmaceutical product promotion, insulating medical education from pharmaceutical industry influence, closing the “revolving door” between regulators and industry, making post-approval drug monitoring and risk mitigation a function of government, and firewalling bodies with formal power over prescribing from industry influence. To lessen the often overwhelming political clout of the industry, it also recommends exposing “astroturf” advocacy groups funded by industry and restoring limits on corporate donations to political campaigns.

Domain 2.

The Commission is cognizant that perceptions of opioid medication are currently polarized and over-simplified, when the reality is that these drugs are in some cases of great benefit and in others very harmful.45 Regulators must hold this dual nature of opioids in mind rather than “throwing the switch” one way or the other toward overly lax or overly restrictive prescribing policies, both of which have significant potential for harm. The drug approval process would be improved by considering the risk of a medication being diverted (e.g., for sale and for misuse by someone other than the patient) and also by conducting more long-term, pragmatic clinical trials on opioids’ risks and benefits. Improving the management of pain is critical, and could be facilitated in the USA by re-energizing the National Pain Strategy that was prepared at the close of the Obama Administration.46 The medical profession should promote opioid stewardship both for its own value and also to help restore trust in medicine among policymakers and the public, which the opioid crisis has damaged.47 Methods for fostering opioid stewardship include prescription drug monitoring programs, “nudges” toward safer prescribing, and expanding access to opioid agonist therapy for addiction that still maintaining adequate controls on it.48–51

Domain 3.

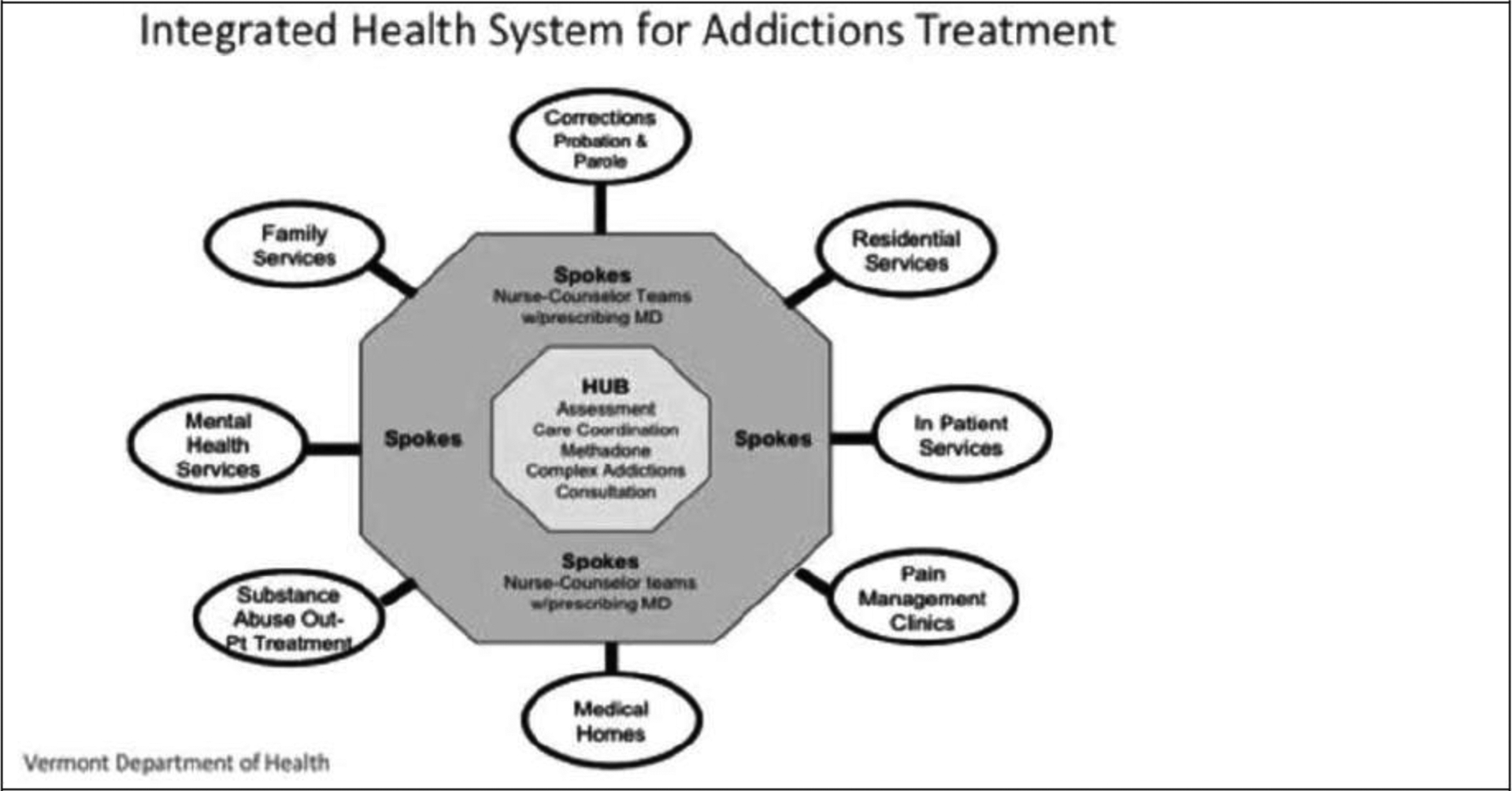

The Commission noted the lack of accessible, high-quality, non-stigmatizing, and integrated health and social care services for people experiencing opioid use disorder in the USA and to a lesser but still significant extent in Canada.52 This situation could be improved by financing such care through the mechanisms that support the rest of the health care system. The Commission recommends ending this situation by reforming public and private health insurance systems, including cutting off funding for care that is likely harmful. The Commission suggests that care systems should follow established models of chronic disease management to promote many pathways to recovery from addiction.53 It also calls for a setting aside of longrunning disputes between factions in the field, urging them to unify under the banner of public health. Finally, a major investment in workforce development is recommended, specifically increasing the number of addiction specialists and increasing the addiction-related knowledge and skills of general practitioners.54

Domain 4.

Although some advocates believe that the criminal justice system should have no role in responding to addiction, some role is inevitable given the public safety harms of intoxicated conduct and the fact that many arrests of people who are addicted involve nondrug crimes (e.g., domestic violence).55 The Commission therefore focused on ways of maximizing the good the justice system could do while minimizing the damage it can inflict. The former include providing addiction treatment and other health services during incarceration;56 the latter include forgoing incarceration for possession of illicit opioids for personal use, repealing collateral penalties for drug-related crimes, and ending punishment for opioid use during pregnancy.57,58

Domain 5.

Epidemics of disease are never resolved through the provision of services to identified cases; rather, prevention of new cases is essential. One practical method for achieving this in the USA is to adopt the methods used in other countries to facilitate disposal of the billions of excess opioid pills in households.59 Because most risk factors for developing drug problems are generic (e.g., chaotic, unrewarding environments, unremitting stress, social exclusion, violence and other trauma, sexual assault, parental abuse and neglect, and individual risk factors such as having difficulty managing emotions, coping with challenges, and exercising behavioral self-control), another important tactic is to support “horizontal” prevention programs for youth that strengthen core capacities that reduce risk not only for drug use, but for many other problems such as depression, anxiety, school failure, and obesity.60 Restrictions on youth-targeted advertising of addictive drugs (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, pharmaceuticals) is another example of a valuable prevention effort that keeps the environment in mind. Finally, the Commission notes the evidence that enriching the environment more broadly, particularly for children and adolescents in economically struggling, high-stress regions, can plausibly lower the incidence of addiction over the long term.

Domain 6.

In surveying the terrain, the Commission was dismayed to note the slow pace of innovation in society’s response to drug problems, whether in law enforcement, health care, data science, new drug development, or technology. Many programs and policies worthy of endorsement today are variants of approaches that could have been recommended 20 years ago. The Commission therefore recommends implementing public policies that correct for failures in patent law and market incentives, prioritizing opioid molecule redesign and non-opioid medication development, and weighing international data more heavily in medication approval decisions.61,62 It also suggests deploying innovative strategies to disrupt fentanyl transactions (e.g., “spoofing” internet-based drug markets) as well as tasking a federal agency to conduct “out of the box” demonstration projects (e.g., delivery of substance use disorder prevention and treatment programs in unconventional settings, development of a device for automated naloxone administration, or application of machine learning methods to predict response to pain and risk of addiction in patients for whom an opioid prescription is being considered).

Domain 7.

Finally, the Commission warns that pharmaceutical companies based in the USA are actively expanding opioid prescribing outside North America, including using fraudulent and corrupting tactics that have now been banned domestically.63,64 This raises risks of a repeat of the tobacco experience, in which an addiction-promoting industry adapted to tighter regulation in wealthy countries by expanding its business in developing nations.65,66 The Commission urges regulators in the USA to stop pharmaceutical producers from exporting fraudulent opioid promotion practices abroad. In order to give poor nations an alternative to partnering with for-profit multinational corporations, the Commission recommends that the World Health Organization and donor nations coordinate provision of free, generic morphine for analgesia to hospitals and hospices in low-income nations.

Because the opioid crisis developed over decades, reversing it in North America and preventing it from spreading abroad will not be easy. Even perfect attainment of all the recommendations here will not eliminate the opioid crisis: tragically, many future deaths are inevitable at this point. But implementing the Commission’s recommendations has substantial potential to save lives and reduce suffering from the crisis both in the USA and Canada, and around the world. The gains of such polices will be long lasting if they curtail the power of health care systems to cause addiction and maximize their ability to treat it.

Introduction

Over the past quarter century, the United States and Canada have experienced an increasingly devastating opioid crisis which has cost those nations more lives than World War I and II combined.67 Although COVID-19 has seized the attention of policymakers and the public, the epidemic of addiction and overdose that preceded it remains unabated, and indeed appears to have been worsened by the consequences of COVID-19.68 This deepening disaster led Stanford University School of Medicine and The Lancet to assemble a Commission on the North American Opioid Crisis. This paper presents the findings and analysis of the Commission and the recommendations that follow from them.

A brief review of the evolution and status of the North American opioid crisis provides the context for the Commission’s recommendations. One aspect of the crisis is not new: opioid addiction was a prevalent reality for more than a century before the crisis began. Beginning in the late 19th century when chemistry and capitalism combined to dramatically expand population exposure to tobacco, stimulants (e.g., cocaine, amphetamines), sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines), and opioids (e.g., morphine and heroin), addiction became a much more prevalent public health problem in North America and in many other societies as well. But nothing in the history of either the USA or Canada regarding opioids was ever remotely on the scale of the past quarter century.

The approval of Purdue Pharma’s long-acting opioid medication OxyContin in 1995 is as reasonable a point as any to date the beginning of the modern opioid crisis.69 OxyContin was fraudulently marketed as less addictive than other opioids and hence more acceptable to use for a broad range of indications and at high doses. But when crushed to immediately release all the contents, OxyContin and other long-acting opioids that followed were more potent than any formulation that had preceded them. The widespread availability of pharmaceutical opioids also has no historical parallel. Backed by the most aggressive marketing campaign in the history of the pharmaceutical industry, OxyContin became the most well-known of a number of opioid medications (both extended release and immediate release) whose prescription rate exploded in the USA and Canada.4 Regulators failed to step in, for reasons ranging from industry cooptation to incompetence to a sincere but mistaken belief that they were ushering in a new era of improved patient care.70

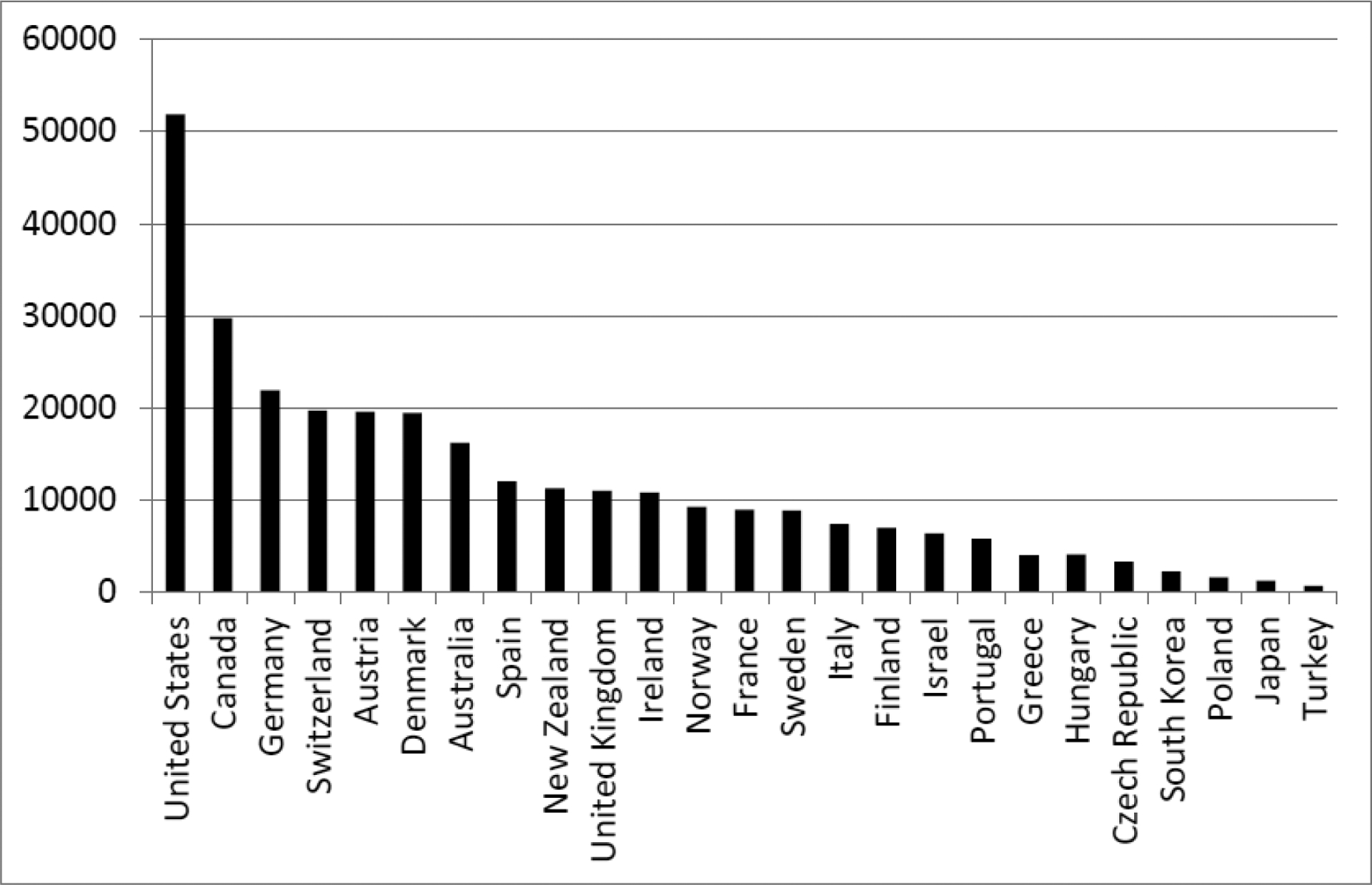

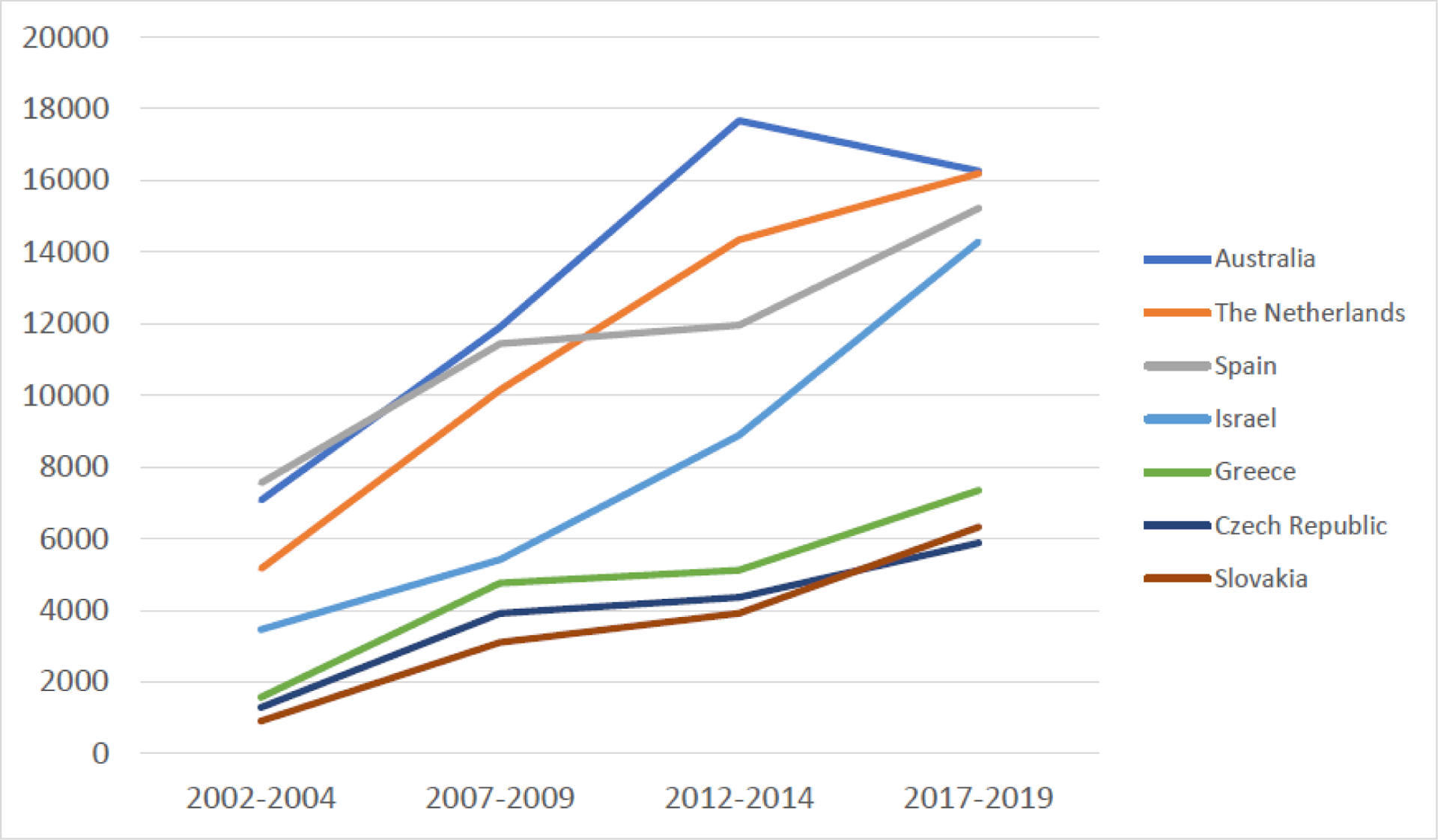

Departing from decades of medical tradition that employed opioids mainly for cancer, surgery, and palliative care, North American regulators, physicians, and dentists expanded opioid prescribing to a broad range of non-cancer pain conditions from lower back pain to headaches to sprained ankles.8–10,71 Per capita opioid prescribing in morphine milligram equivalents roughly quadrupled in the next 15 years, to the point that the Canadian and USA health care systems were writing as many opioid prescriptions annually as there are adults in those two nations.26 This level of opioid exposure had no parallel in their national histories nor worldwide.72,73 The United Nations gathers data converting different types of opioids into a “standard daily dose”, which allows comparison across countries. These data (figure 1) show that the USA and Canada exceeded developed country norms by a significant multiple,74 which is particularly notable for the USA’s case because the comparator nations in the chart mostly have older populations and all have universal health care access, both of which would be expected to increase prescribing.

Figure 1:

National per capita prescription opioid consumption, in standard daily doses/million inhabitants, during North American peak (years 2010–2012)

The political and cultural environment at the time the crisis emerged was not conducive to an early response; indeed complacency allowed it to worsen. To attain respectability, trust, and influence throughout the world, opioid manufacturers strategically donated a small share of their profits to prominent institutions, including hospitals, medical and dental schools, universities, museums, art galleries, and sporting events.70,13,75 This secured good will, increasing the credibility of the industry’s message that it was a selfless healer pushing back against cruel anti-opioid prejudices. Also, in the wake of the aggressive response to the USA’s crack cocaine epidemic, a backlash against any form of drug supply control was ascendant, and some prominent cultural commentators characterized any concerns about opioid overprescribing as a war on drugs-style crackdown,76 reinforcing messages of the corporations that were profiting from the epidemic.

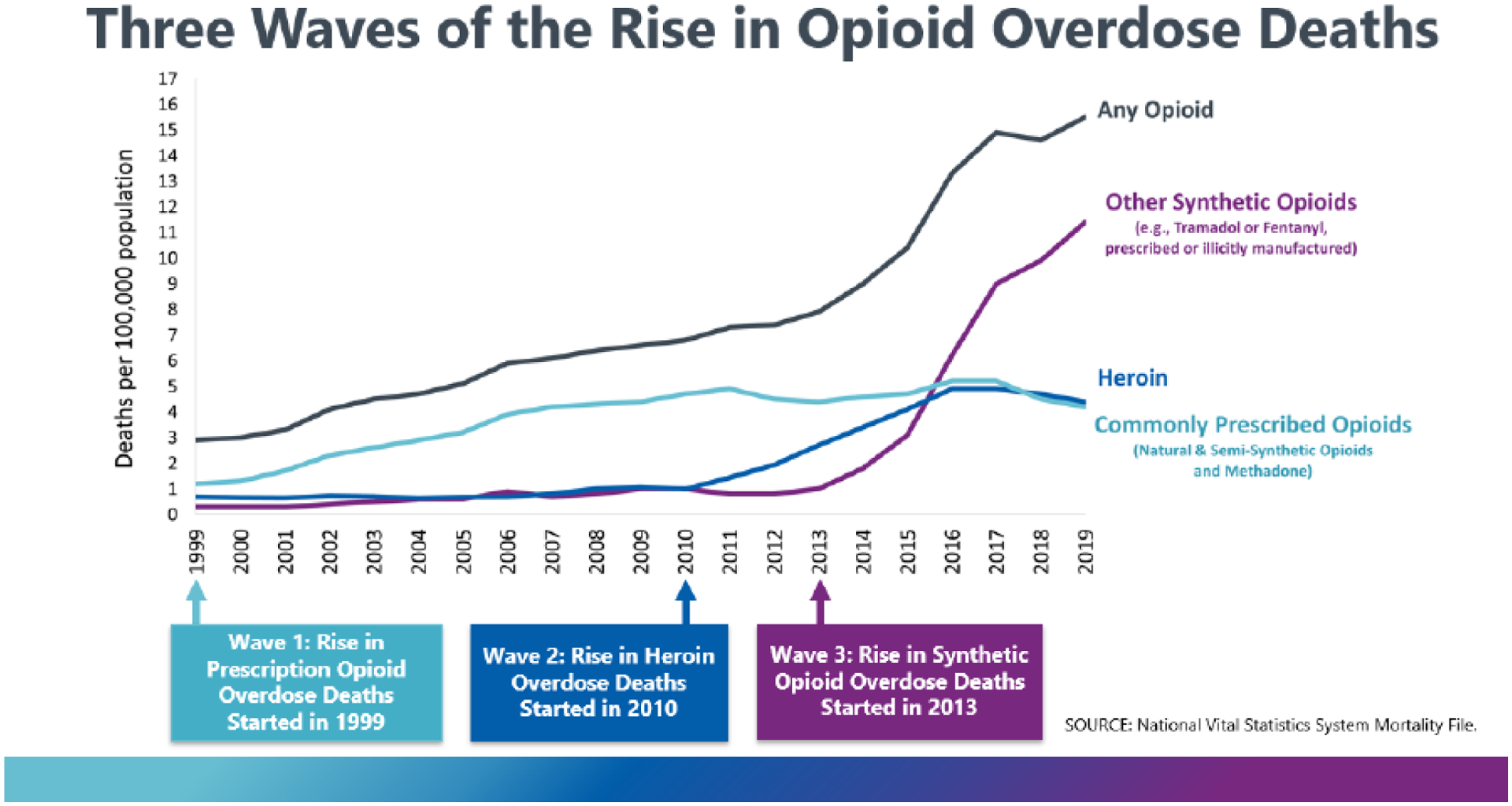

Some patients in pain may have benefited from increased opioid prescribing, but the overall impact was catastrophic. The health-related consequences were prescription opioid-linked morbidity (e.g., addiction, depression, hormonal dysregulation) and mortality (e.g., from overdoses and accidents) rising roughly in parallel with prescribing (figure 2). The damage also went beyond health to include increased unemployment, disability, crime, truancy, and family disintegration.13 The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated the annual cost of the epidemic at a trillion dollars in 2017, equal to a staggering 5% of gross domestic product.13 Despite Canada and the USA differing on many dimensions that are sometimes assumed to limit the spread of drug-related morbidity and mortality, e.g., universalized health care, level of inequality, and availability of addiction-focused health services, the worst hotspots in the two countries experienced a similar opioid overdose death rate.77 The opioid crisis showed that in the absence of adequate supply control over any addictive drug, damage to human health and well-being is unavoidable, a lesson we will return to later when we discuss the prospects of the crisis spreading beyond North America.

Figure 2:

The three waves of fatal opioid overdoses in the United States

The first wave of the current crisis involved prescription opioids and occurred at a time when illicit markets in heroin were isolated and stable in much of Canada and the USA. The second wave, which began around 2010, was fueled by the first. It was catalyzed when drug traffickers recognized that individuals addicted to prescription opioids were a fertile market for heroin.15 As traffickers expanded heroin markets, including in small cities and towns where they had never existed before,78 many prescription opioid-addicted individuals were drawn in by the comparatively low price of heroin.67 Approximately 80% of Americans who initiated heroin use started with prescription opioids,79 even before any significant controls on prescribing were introduced. Once efforts began to stop the rise in prescriptions and to reduce their diversion, some prescription opioid-addicted individuals began shifting to heroin more rapidly than they otherwise would have.80,81

The third wave of the opioid crisis began around 2014 as illicit producers began adding extraordinarily powerful synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) to counterfeit pharmaceutical pills, heroin, and stimulants.31,82 This wave brought unprecedented lethality on top of - rather than instead of - the prior waves, both of which continue today. Large numbers of North Americans are still becoming addicted to prescription opioids each year, and most of those who die from heroin and fentanyl are previous or current consumers of prescription opioids.83,84

Each wave of the opioid crisis did not crash with equal force on all shores of North American life. In the USA, the first wave had a greater adverse impact on white Americans than African-Americans, in part because the former are more likely to have health insurance and hence ready access to prescription opioids. Racist beliefs among some providers that African Americans have unusually higher tolerance for pain or are particularly prone to divert medication may also have reduced opioid prescribing to African Americans relative to whites.85,86

In both the USA and Canada, indigenous peoples had extremely high overdose rates during the first wave of the epidemic.25,27 In the USA, the volume of opioid prescriptions in Native lands rivalled that of Appalachia.87 Canadian First People’s also had high rates of prescribing and opioid-related harm,25 which can be partially traced to “fly-in” physicians on short-term contracts – who administer much of the health care for many of Canada’s indigenous communities – favoring quicker pharmaceutical fixes over more time-consuming pain treatments (e.g., physical therapy).88

Many middle class, employed people experienced prescription opioid use disorder (OUD), but the problem was more prevalent among unemployed individuals28 and those living in economically distressed geographic areas in the USA and Canada. People experiencing homelessness and unstably housed people are at high risk for overdose, though few jurisdictions collect data on housing status as part of routine surveillance.26,33–35 People who have recently been released from incarceration have faced very high overdose risk.35,36 Unlike prior opioid epidemics in North America, some of the regions with highest mortality were predominantly rural (e.g., West Virginia and Maine in the USA; The Yukon in Canada). Other rural areas had lower than average mortality. National USA survey data gathered in 2015 data showed that rates of prescription OUD eventually became similar across rural, suburban, and urban areas.28

The second and third waves hit urban areas and some minority populations harder than did the first wave.89 In the USA, African-Americans now suffer from the fastest growing overdose death rate.90 Some of these deaths are among stimulant users and long-term heroin users who were likely unaware that the drugs they consumed were laced with fentanyl analogs.

No group was immune from any of the three waves of the opioid crisis, even though each wave hit different communities differently. The combined effect has harmed almost every subpopulation in the USA or Canada, with enormous human cost (see panel 1). In the U.S., the current mortality rate for opioid toxicity is over 20 per 100,000 population, while in Canada the rate is over 17 per 100,000. Both of these exceed the mortality rate at their respective nation’s peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.22–24

Panel 1: Voices of individuals and families facing opioid addiction.

“I’ve got terrible pain, but I’m also addicted to painkillers, and right now my addiction is worse than my pain.” Patient in recovery from alcohol use disorder for 10 years who became addicted to prescribed morphine”.40

“I started seeing a lot of pills around 15 years old and I told myself I was never going to do them. But kids were selling Oxys at school for $3 a pill. By the time I was 19, I was looking in every medicine cabinet and bathroom.”

-Jonathan Whitt, Minford, Ohio91

“Those people you keep hearing about on television who they find passed out in parking lots? That was me…I wasn’t homeless or in trouble. I was just bankrupt inside. I was empty. There wasn’t another use left in me.”

-Nina Zakas, Charleston, West Virginia92

“I don’t want Nick to be only a statistic or thought of as a throwaway person who didn’t matter. People always said how positive, polite and well-mannered he was. But I don’t want people to think that that should be the criteria for not dying of a fentanyl overdose.”

-Patricia O’Connor (mother), Vancouver, British Columbia93

“After the surgeries, when I got back home… at that point I was lost. I was in a different world, on deep, deep, deep medications, different types then I started finding myself calling more, and then at some point your mind turns to the only thing that really makes any difference is to get pain medication. It was kind of an irrational thing, that this is supposed to help me get up and move around, but it’s keeping me down and destroying me.” Patient addicted to prescribed meperidine.94

Current status of the North American opioid crisis

In the USA and Canada, 2020 was the worst year on record for fatal opioid overdoses both in terms of number of deaths and percent increase over the previous year. Opioid toxicity deaths in Canada increased 63% to 6,214 from 3,830 the prior year, bringing the total of such deaths in Canada to 21,174 between 2016–2020, the period for which national data are available.21 Provisional USA data from 2020 indicate that fatal opioid overdoses rose 37% from 50,963 to 69,710, bringing the total of such deaths since 1999 to over 583,000 people.32 Although the 2020 spikes may be partially attributed to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, a rising trajectory of fatalities was evident in the USA throughout 2019 and in both countries during the first quarter of 2020, before the pandemic took hold in either nation.19,20,95,96

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected virtually every aspect of life and society, and substance use disorder and overdose are no exception. Leading up to the pandemic, fentanyl and other synthetic opioids had already begun spreading to the entire USA after being rare in illicit drug markets west of the Mississippi River and common in western Canada.19 Disruptions to drug supply following shelter-in-place restrictions may have further favored synthetic opioids, which are cheaper by weight compared to lower-potency drugs and are largely distributed by mail.96,97 A study of five of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s 33 High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas found that between March and September 2020, the number (but not aggregate weight) of seizures of fentanyl and methamphetamine increased significantly compared to the same period in 2019, while there was no significant change in count or weight for heroin or cocaine seizures.98 OUD treatment policy also changed in several key ways discuss in the Commission’s report, including an expansion of telehealth in both countries, greater provision of take-home methadone in the USA, and suspension and eventual removal of the X-waiver requirement to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD treatment to up to 30 patients in the USA.99–101 The implementation of these measures varied greatly, in ways that are still being evaluated, but evidence from some states suggests that the number of people receiving medications for OUD increased after regulations were relaxed.102–104 Changes to incarceration policy and practices may also have influenced overdose rates and treatment for OUD as some jails and prisons reduced populations or adapted corrections-based treatment for OUD in response to the pandemic.105–107 Importantly, the social effects of living through a pandemic – including isolation, unemployment, lack of familiar structure to daily life and well-founded worry in uncertain times – have likely contributed to rising overdoses and worse outcomes for people living with OUD.108

This epidemiological overview draws on the most recently available national mortality data from the U.S. (CDC Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research), Canada (Public Health Agency of Canada’s Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses), and various subnational jurisdictions with more recent data available.14,21 Fatal overdoses are only one dimension of the opioid crisis, but such data are more recent and of higher quality than data in other areas, and also, overdose fatalities are arguably a proxy for other harms. Therefore, we conducted basic analyses on most recently available national data from each country to describe the current landscape of opioid overdose mortality in terms of geographic, demographic, and social factors. State/province-level statistics rely entirely on data from 2020 – provisional data from the United States and final data from Canada. USA provisional data do not include information on age, race/ethnicity, or sex; therefore, analyses of U.S. demographics use the 2019 data from the CDC as it is the most recent available as of July 2021.

Though much of the data are directly comparable, the CDC and Public Health Agency of Canada categorize opioid toxicity deaths differently in two important ways: origin and category. The most recent Public Health Agency of Canada report dichotomizes between pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical opioids and separately categorizes drugs as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, or non-fentanyl opioids. The CDC does not classify by pharmaceutical origin and uses the categories heroin, natural and semi-synthetic opioids (includes most prescription opioids such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, codeine), methadone, other synthetic narcotics (this includes synthetic opioids like fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, fentanyl precursor chemicals, tramadol, meperidine, and novel psychoactive substances like isotonitazine or U-47700109), and opium. The CDC data do not distinguish pharmaceutical from illicitly manufactured fentanyl, though the former accounts for a vanishingly small proportion of deaths in both countries.31

For CDC data analyses undertaken for this report, deaths occuring in January to December 2019 were included using International Classification of Diseases Code 10th edition (ICD-10) codes. Deaths were included if they had one of the following as underlying cause of death: accidental poisoning (X.40–X44), intentional self-poisoning (X60–64), assault by drugs (X85), or poisoning of undetermined intent (Y10–14); and T40.0–T40.5 as contributing cause of death. In total this includes 49,126 fatal opioid toxicity deaths, many involving multiple categories of opioids or other substances. This number is slightly lower than the 50,963 in the provisional 2019 statistics mentioned above because it does not include deaths classified under ICD-10 code T40.6, “Poisoning by, adverse effect of and underdosing of other and unspecified narcotics” but not ICD-10 codes T40.0–40.5. By non-exclusive category, these include other synthetic narcotics (n=36,359, 74%), heroin (n=14,019, 29%), natural and semi-synthetic opioids (n=11,886, 24%), methadone (n=2,740, 6%), and opium (n=2, 0.004%). Detailed USA mortality data with specific drugs involved were downloaded from public online datasets (Connecticut, Cook County, Illinois; Dallas-Fort Worth area of Texas; San Diego County, California), or provided to commission authors via public records requests (Milwaukee County, Wisconsin; Jefferson County, Alabama; Los Angeles County, California).

The report from Public Health Agency of Canada’s Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdose documented 6,214 opioid overdose deaths in 2020. During this period, 80% of deaths involved fentanyl, 10% involved fentanyl analogues, and 31% involved non-fentanyl opioids, though as in the USA, many deaths involved substances across two or more of these categories. Overall, 77% of fatal overdoses involved only non-pharmaceutical opioids, 12% involved only pharmaceutical opioids, and 7% involved both.21

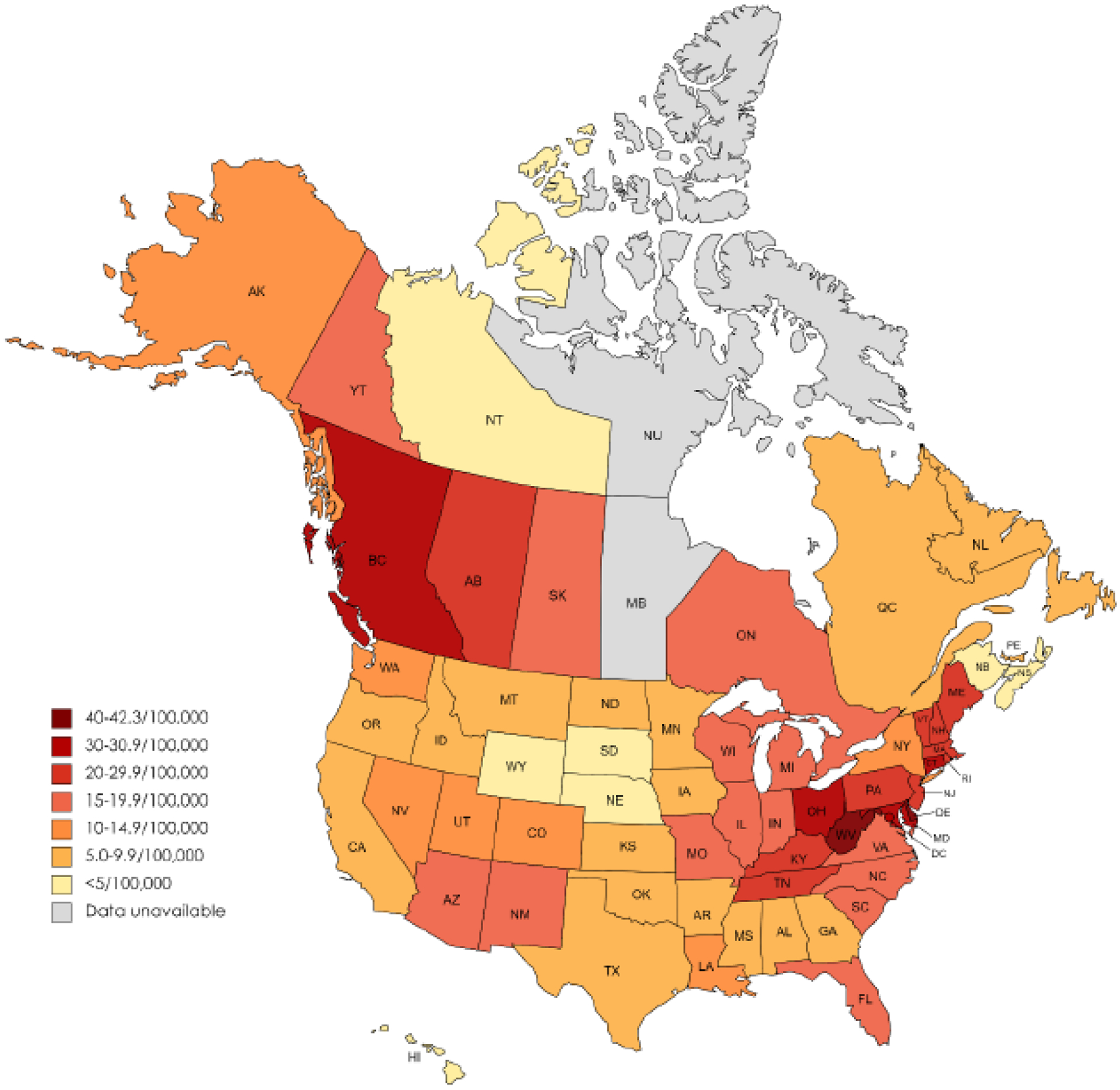

In both countries, the mortality rate varied substantially between states and provinces (figure 3), with the highest rates in western Canada (British Columbia and Alberta), Appalachia (particularly West Virginia and Ohio), and the northeastern seaboard of the USA. Canada’s 2020 age-adjusted rate was 17.2 per 100,000 population (a 67% increase over the 2019 rate of 10.3). Although 2020 age-adjusted rates are not yet available for the USA, the number of opioid-involved deaths are estimated to have increased 37% from 2019 to 2020.32

Figure 3.

Age-adjusted per capita opioid overdose mortality, Jan-Dee 2019 (United States), and Jan-Sept 2020 (Canada)

Canadian data from Public Health Agency of Canada. U.S. data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research

In the USA and Canada, the majority of fatal opioid overdoses occur among males, with a greater sex disparity in Canada.14,21 In 2019, 70% of fatal opioid overdoses in the USA occurred among males, who had a population- and age-adjusted death rate 2.4 times that of females. In 2020, males in Canada died from opioid overdose at 3.3 times the rate of females, with males composing 77% of opioid overdose deaths during this period.21 In Canada, the largest sex disparity was in British Columbia, where males died from opioid toxicity at a rate 5.5 times higher that of females during this period. The province of New Brunswick had the smallest sex disparity, with the opioid toxicity mortality rate among males being 1.9 times that of females. In the USA, the 2019 rate ratio for age-adjusted opioid overdose mortality among males versus females was greatest in Connecticut (3.3), Massachusetts (3.2), and the District of Columbia (3.1) and smallest in Nebraska (1.2), Idaho (1.3), and Utah (1.3).

Types of opioids involved in fatal overdose also differ by sex. In the most recently available data, opioid-related deaths among females were about twice as likely to involve a prescription (pharmaceutical) opioid (30% in Canada, 33% in the USA) compared to males (16% in Canada, 14% in the USA).21 Nearly 80% of fatal fentanyl overdoses in Canada in 2020 occurred among males, as did 82% of fatal overdoses involving fentanyl analogs; similarly, males accounted for 75% of fatal heroin overdoses and 72% of synthetic narcotic overdoses in the USA in 2019.

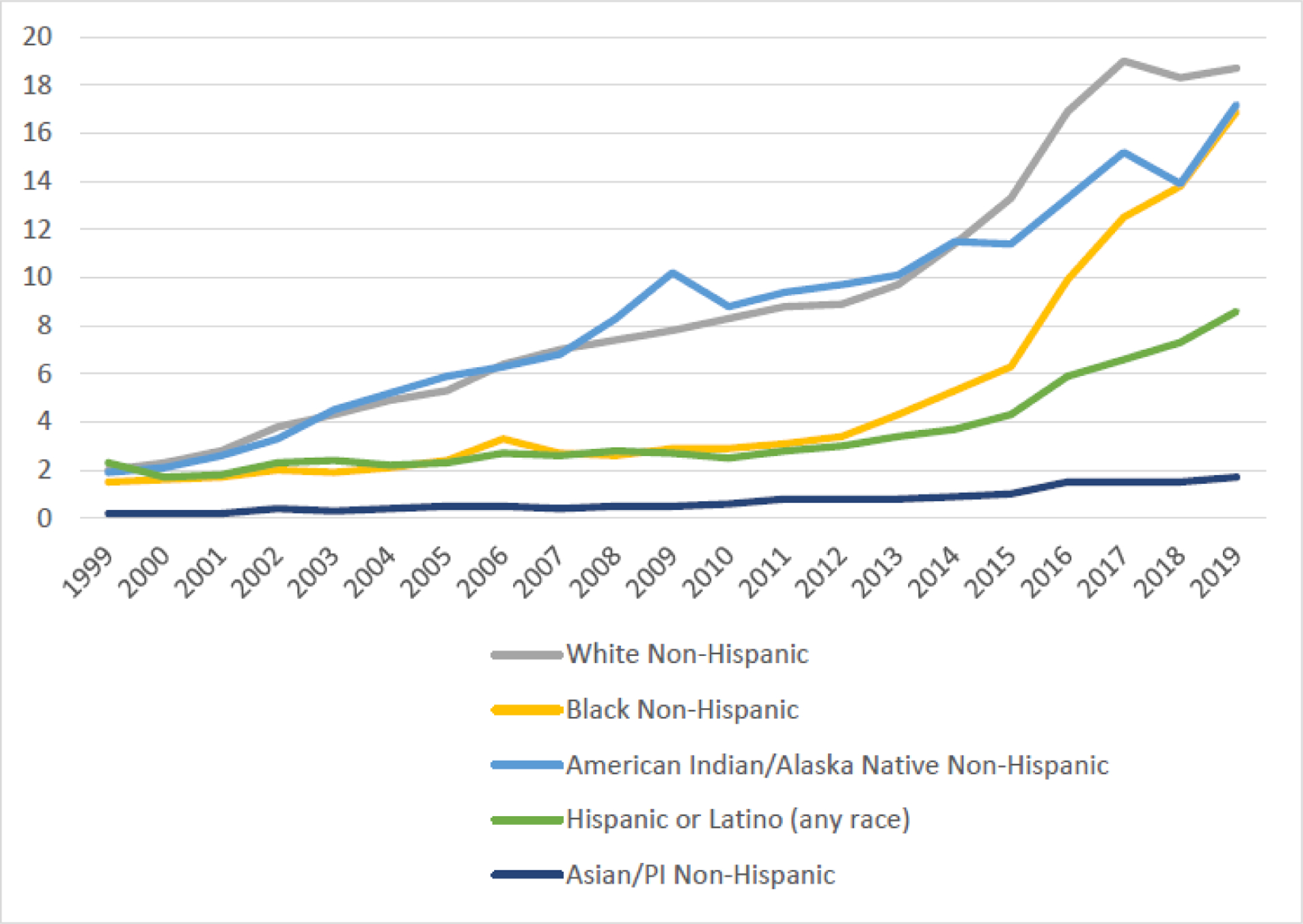

As of 2019, U.S. fatal opioid overdose rates were still highest among non-Hispanic white Americans although the rate among American Indians and Alaskan Natives has been almost as high throughout the crisis. Since 2011, the mortality rate has grown fastest among non-Hispanic African Americans approaching those of both these groups (figure 4).90 Although comprehensive national data on racial and ethnic distribution of deaths during 2020 were not available as of July 2021, an analysis of 2020 emergency medical services data found that fatal overdose-associated cardiac arrests (not disaggregated by opioid-related versus non-opioid-related) among Black and Hispanic Americans grew disproportionately over the previous year.95 In 2019, the age-adjusted rates were highest among non-Hispanic whites (18.7/100,000), non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Natives (17.2/100,000), and non-Hispanic Black or African Americans (16.9/100,000). Despite similar rates nationally, substantial racial disparities emerge at the state level.

Figure 4.

U.S. age-adiusted opioid-involved mortality rate per 100.000 population, by race and ethnicity, 1999–2019

Data from U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research

Of the 33 states with sufficient race and ethnicity data to evaluate the mortality rate ratio between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic Black or African Americans, only six have age-adjusted mortality rates for these two groups that are within 10% of each other. Compared to white non-Hispanics, the age-adjusted mortality rate for Black non-Hispanics was substantially higher in 10 states, including five Midwestern states where it was more than double that of non-Hispanic whites (Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Wisconsin, Illinois). Seven states in the Southern USA had age-adjusted opioid overdose mortality rates among white non-Hispanics that were more than double those of non-Hispanic Black or African Americans (Mississippi, Florida, South Carolina, Louisiana, Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina). Only 10 states had sample sizes large enough to calculate rate ratios comparing age-adjusted mortality of American Indian or Alaska Natives and non-Hispanic whites. Notably, six of these states had higher age-adjusted mortality among American Indian or Alaska Natives, including Minnesota (over 10 times that of non-Hispanic whites), Wisconsin (more than triple), Washington (more than double), Alaska (85% higher), North Carolina (45% higher), and California (29% higher).Though mortality rates were generally lower among Hispanics compared to the general population, the age-adjusted opioid overdose mortality rate was higher among Hispanics of any race compared to non-Hispanics in New Mexico (68% higher), Pennsylvania (17% higher), Colorado (15% higher), and New York (11% higher).

In the most recently available data from both countries, about 88% of overdose deaths occurred among people between the ages of 20–59.14,21 Fatal overdoses involving synthetic narcotics -- including fentanyl or fentanyl analogs -- were most common among individuals aged 30–39, with about a third occurring in this age group.14,21 In Canada, deaths involving non-fentanyl opioids skewed older, with 37% of non-fentanyl opioid deaths occurring among individuals 50 and over.21 Similarly, mortality rates in the USA for natural and semi-synthetic opioids (the category most closely matching prescription opioids) peaked in the 55–64 age group in 2019.14

Polysubstance overdoses, particularly co-involvement with stimulants, is common in fatal overdoses in the USA and Canada but varies substantially within both countries. Mortality data unfortunately does not distinguish between intentional co-use of opioids and stimulants versus unintentional contamination. That said, in Canada, 51% of fatal opioid overdoses in 2020 also involved stimulants.21 USA provisional data indicates that from 2019 to 2020, fatal overdoses involving “psychostimulants with abuse potential” (a category that includes methamphetamine as well as other stimulants) increased by 46% and fatal overdoses involving cocaine increased by 21%. Though it is not possible to determine overlap with opioids using the USA provisional data, estimates from the 24 states and District of Columbia participating in the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System showed that 33% of overdoses in 2019 involved both stimulants and opioids.37 Overlap between stimulants and opioids varies substantially in the U.S. jurisdictions that make mortality data available more quickly than the CDC (figure 5).

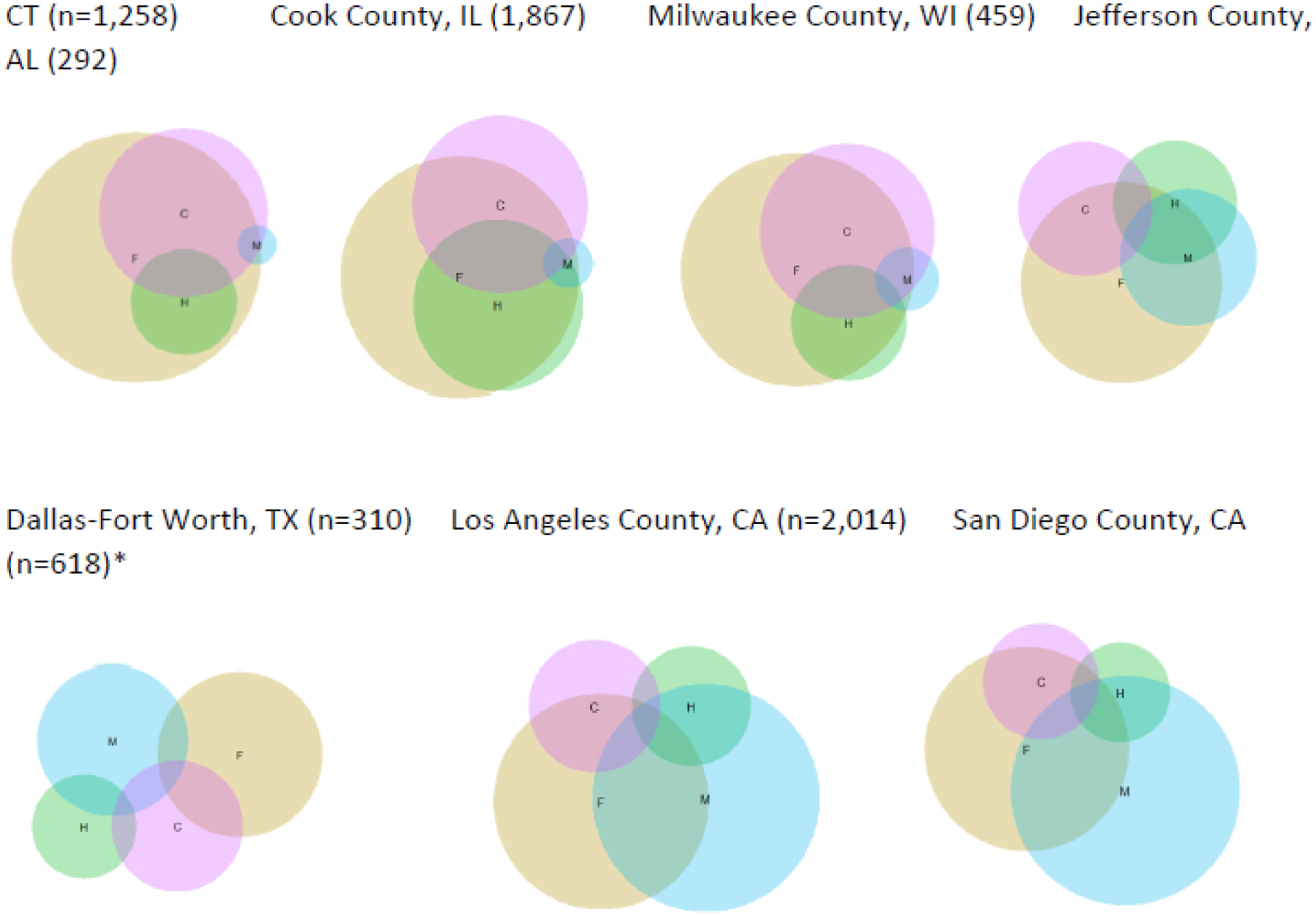

Figure 5.

Drug combinations involved in fatal overdoses from U.S. jurisdictions with detailed medical examiner data, 2020

F: Fentanyl and fentanyl analogs H: Heroin M: Methamphetamine C: Cocaine

*Includes data from January – September, 2020

Differences in drugs involved in fatal overdose can be striking even across proximal geographic areas. In British Columbia in 2020, 86% of fatal overdoses involved fentanyl, with a similar proportion in the first four months of 2021.110 A few hours’ drive south across the USA-Canada border in King County, Washington, fentanyl was involved in 33% of overdose deaths in 2020.111 From January to September 2020, 73% of all fatal overdoses in Canada involved fentanyl and 60% of opioid-involved deaths also involved stimulants.21 In USA jurisdictions with detailed medical examiner data that becomes available well in advance of CDC mortality data, it is possible to see marked differences in substances involved in fatal overdoses.19,109 For example, in the eastern and mid-western USA (i.e., Connecticut, Chicago, Milwaukee), there is near total overlap between heroin and fentanyl in fatal overdose, and cocaine is the more common stimulant. Conversely, methamphetamine is more common in the southern and western jurisdictions with these data available, and a substantial proportion of heroin deaths do not involve fentanyl.

The Stanford-Lancet Commission on the North American Opioid Crisis

The Commission was created in the fall of 2019 at the invitation of The Lancet editors to Keith Humphreys. Stanford University School of Medicine subsequently agreed to partner with The Lancet and to provide all funding for the Commission’s work. Ten Stanford-affiliated individuals already working on some aspect of the opioid crisis were invited by join by Humphreys as were eight leading experts from around the USA and Canada. Three additional scholars were asked to join in the special role of reviewer.

Commissioners were drawn from the fields of addiction, biochemistry, emergency medicine, epidemiology, health economics, internal medicine, law, pain medicine, policy analysis, psychiatry, pharmacology, and public health. The Commission included clinicians, researchers, educators, public policymakers, and individuals with lived experience of addiction and chronic pain. All Commissioners were based in the USA or Canada, reflecting the fact that the opioid crisis is at this writing concentrated in those two countries.

After an initial meeting of Stanford-based Commissioners in January, 2020 to begin charting the project’s timeline and goals, all Commissioners (including those in the reviewer role) and The Lancet’s Americas Editor convened for two days at Stanford University in February 2020 for a series of discussions of various aspects of the epidemic. Each discussion section was facilitated by a different Commissioner, and generated lists of key analytic themes, critical data, and potential policy actions. After this meeting, the reviewing Commissioners provided initial feedback and then, to avoid groupthink, absented themselves from all deliberations for the ensuing ten months.

Unlike some other Lancet Commissions, this one focuses on a long-entrenched problem that has already been well-characterized, including in multiple National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reviews (on which several Commissioners had served).1–3 The Commission therefore did not conduct another comprehensive literature review, but instead focused on developing a coherent, empirically-grounded analysis of the causes of and solutions to the opioid crisis. Some epidemic modelling work was done to support this process, and is described in detail elsewhere.112

The Commission moved its deliberations online with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Subgroups with special expertise investigated and debated individual issues over email chains before presenting them to the full Commission for further discussion. Any major substantive conclusion or recommendation that did not command at least 90% support from Commissioners was modified until it achieved such support or was dropped if it could not.

Every Commissioner reviewed, contributed to, and approved an initial full report, which was then critiqued by the three reviewing Commissioners who had attended the first meeting as well as other reviewers and editors picked by The Lancet in early 2021. This is the revised report of the Commission.

Although more limited in geographic scope than other Lancet commissions in being largely focused on two countries, the Commission draws on evidence from beyond them to discuss ways to prevent the international spread of the opioid crisis. The term “North American” is a linguistic convenience referring to the continent where the two countries are based, and does not imply that every country (e.g., Mexico113,114) and territory (e.g., Greenland) on the continent is experiencing an opioid crisis.

The Commission members are scholars rather than elected officials with a democratic mandate, and thus tightly tied its analysis and recommendations to science rather than recommending actions on the basis of purely political and philosophical rationales. All Commission recommendations therefore had to be grounded in evidence of likely benefit to public health, public safety, or both.

The Commission took a population public health perspective, emphasizing general principles and policies for responding to the crisis. It therefore did not attempt to delineate clinical issues such as how to manage the care of individual types of patients with OUD or what precise human service elements each individual health care organization should offer such patients.

The Commission’s model of the opioid crisis estimates that in the absence of any intervention, the USA will experience a staggering 547,000 opioid overdoses from 2020 to 2024.112 The Commission therefore proposes bold responses (summary in table 1) which the USA and Canada can adopt to better meet this enormous public health challenge. The remainder of this report analyzes the challenges created or illuminated by the opioid crisis in seven key domains and presents recommendations that are responsive to each of them.

Table 1:

Abbreviated list of Commission recommendations

|

Domain 1: The North American opioid crisis as a case study in multi-system regulatory failure Curbing industry influence on prescribers

Curbing industry influence on regulators

Curbing industry influence on the political process

|

|

Domain 2: Opioids dual nature as a benefit and a risk to health Recognizing the risks and benefits of opioids in the drug approval process

|

Domain 3: Building integrated, well-supported, enduring systems for the care of substance use disorders

|

Domain 4: Maximizing the benefit and minimizing the adverse effects of_criminal justice system involvement with people who are addicted to opioids

|

Domain 5: Creating healthy environments that can yield long-term declines in the incidence of addiction

|

Domain 6: Stimulating innovation in the response to addiction

|

Domain 7: Preventing opioid crises beyond North America

|

Domain 1: The North American opioid crisis as a case study in multi-system regulatory failure

“The opioid crisis is, among other things, a parable about the awesome capability of private industry to subvert public institutions”

--Patrick Radden Keefe5, Empire of Pain, p.364

The current opioid crisis resembles prior drug crises (e.g., the rise of heroin addiction in North American cities in the 1960s and 1970s) in some respects but differs in others. Most particularly, the origins of the current crisis reflect dramatic failures within the corporate sector, regulatory and legislative bodies, the medical profession, and the health care system. Because the epidemic of opioid addiction and overdose emerged from and is still to some extent being fueled by legally prescribed opioids, policy responses must be uniquely tailored to that reality. Illuminating regulatory failures is also essential for helping the USA and Canada avoid similar mistakes with other prescription medications, and for informing other nations about how to avoid opioid crises of their own.

Perhaps the most important fact to remember about the North American opioid crisis was that for some people, it brought not suffering but enormous wealth. OxyContin alone is estimated to have generated revenues of over $35 billion for Purdue Pharma and its owners, the Sackler family.115 John Kapoor’s shares in the pharmaceutical company he founded, Insys Therapeutics, were worth $650 million before he was imprisoned for having his sales representatives bribe doctors to prescribe a fentanyl spray and training other staff to defraud insurers who asked for justification for the prescriptions.116 Johnson & Johnson, Endo, Teva, and other opioid manufacturers also reaped substantial revenue from soaring prescription rates. Many pharmaceutical distributors also profited handsomely while knowingly making astonishingly large shipments of pills which they were required to report to regulators but did not.117,118 Profit-seeking was not a phenomenon entirely external to the health care system: some hospitals, clinics, pharmacies, professional societies, and individual health care professionals also enriched themselves, as did some individuals who “doctor shopped” to obtain many prescriptions they could resell.4,40,118

Public health professionals have long advocated that manufacturers, distributors and retailers of addictive drugs in explicitly recreational markets (e.g., alcohol and tobacco) be tightly regulated to prevent them from maximizing profit at the expense of public health and safety. The North American opioid crisis makes it agonizingly clear that the same lesson applies within ostensibly well-regulated medical systems. These risks are not limited to opioids: barbiturate overprescribing generated harm in the past,119 excessive benzodiazepine120,121 and stimulant122 prescribing is causing harm currently, and the future could bring new crises involving other prescription drugs. Assignment of blame, punishment, and restitution for the past is a matter currently under consideration in multiple courts of law. A key question for the future is how to regulate industries – including the health care industry – to prevent the profit motive from fomenting oversupply and overprescribing of pharmaceuticals with addictive potential.

Opioid manufacturers directed their efforts to dramatically expand the market for their products toward three main targets: prescribers, regulators, and policymakers. We now analyze these areas in turn.

Pharmaceutical industry influence on the practice and education of prescribers

In 2016, the pharmaceutical industry spent USA$20.3 billion marketing its products directly to prescribers. This form of marketing comprises in-person office visits, large and small gifts (e.g., branded office supplies, meals and receptions at conferences, travel expenses), and direct financial payments for endorsing industry products in lectures and case conferences. Industry engages in these practices because they are effective at increasing prescribing of their products.123,124 OxyContin was the subject of the most lavishly funded promotion campaign in the history of medicine,4,125 which was highly successful at generating revenue for Purdue Pharma and helped ignite an epidemic of addiction and overdose in North America. Counties in the USA that were targeted with higher levels of physician-focused marketing had higher rates of opioid prescribing and overdose mortality one year later.126

Some opioid manufacturers also promoted their products by changing the design of prescription modules within electronic medical record systems. In January 2020, an electronic medical record vendor was fined $145 million by the United States government for accepting kickbacks from Purdue Pharma in exchange for co-designing software that promoted OxyContin prescription for patients for whom the drug was not appropriate.127,128

Promoting opioids directly to patients is less of a concern than other prescription drugs because of legal restrictions, which should of course remain in place. But the role of direct-to-consumer advertising in opioid overprescribing nonetheless bears mention. New Zealand and the United States are the only countries which allow direct-to-consumer marketing that makes claims about pharmaceutical products.129 From 1997 to 2016, the pharmaceutical industry in the USA increased spending on such advertising from USA$1.3 billion to USA$6 billion,130 which exceeded the entire 2016 budget (USA$4.9 billion) of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that year.131

Opioid manufacturers have multiple ways of using direct-to-consumer advertising to promote opioids even while abiding by the letter of the law forbidding mention of them. This includes indirect promotion, such as buying a USA$10 million dollar Super Bowl television advertisement for a non-controlled drug that makes long-term opioid use more tolerable by reducing constipation.132 The industry also sponsors “unbranded” campaigns to change the public perception of illness and broadly expand the market for medications, as opioid manufacturers did to normalize use of opioids for “non-cancer chronic pain”.133 The bombardment of USA citizens with pharmaceutical advertising increases prescribing even for medicines not mentioned in the ads,134 perhaps because direct-to-consumer advertising changes public expectations about the responsibilities, role, and power of physicians. Making individuals who have medical disorders aware of effective pharmacotherapies is valuable, but direct-to-consumer advertising can also be a form of public health miseducation (see panel 2). Among other problems, it can foster the false impression that if pressured enough by patients,41 physicians can and should provide medicines that eliminate every source of human suffering.

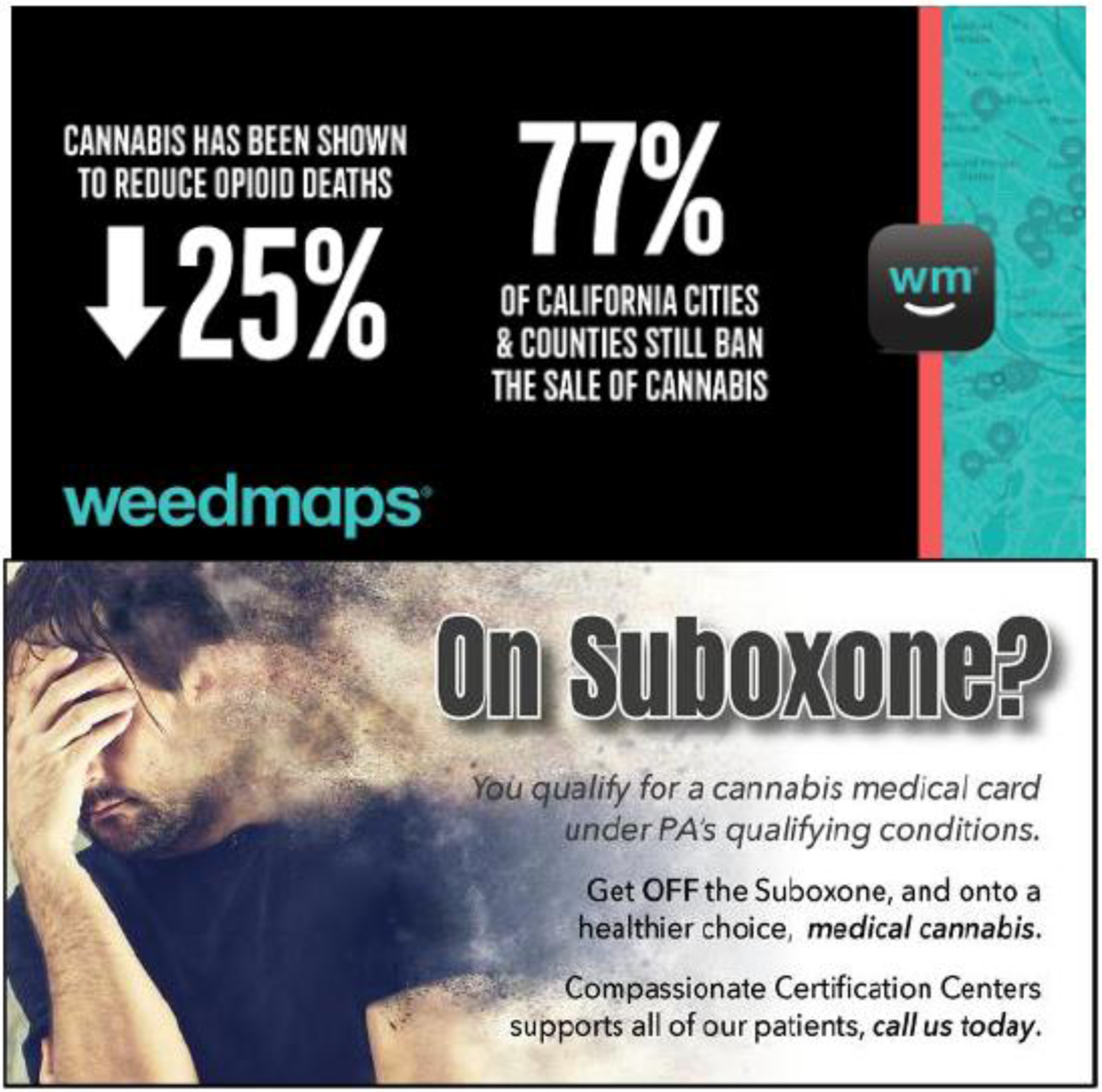

Panel 2: Another industry whose consumer-targeted advertising worsens the opioid crisis: medical cannabis.

The cannabis industry began marketing cannabis legalization as a solution to opioid overdoses after a study found that between 1999 and 2010 states with medical cannabis programs had lower than expected opioid overdose mortality.140 The association between these two population-level indicators was vulnerable to the ecological fallacy, wherein individual-level relationships may differ from the aggregate relationship. Moreover, when 7 additional years of data were added to the time series, the pattern of results reversed: States with medical cannabis laws had higher than expected opioid overdose mortality from 1999 to 2017, even after controlling for more and less restrictive laws (i.e., medical versus recreational versus low potency only).141

Nevertheless, the cannabis industry promoted the initial study findings on billboards and in advertising campaigns (figure 6). Further, several states unwisely added OUD as a qualifying condition for medical cannabis based on the initial ecological correlation, a level of evidence that would be considered unacceptable anywhere else in medicine.142 In states where OUD was a qualifying condition, more medical cannabis dispensaries advertised cannabis as a replacement for FDA-approved medications for OUD.143 These dangerous practices continue despite being based on study findings that did not survive replication.

Prescription drug manufacturers also attempt to influence prescribing by influencing education provided by universities, hospitals, and professional societies. Collaboration between universities and private companies can spur innovation, and every academically-based member of the Stanford-Lancet Opioid Commission works at an institution that has received outside donations to support scholarly and educational activities. These realities co-exist with evidence that corruption of the educational process by opioid manufacturers has been present during the opioid crisis.

For example, in explaining its 2019 decision to strip the Sackler name from its School of Graduate Biomedical Sciences, Center for Medical Education and other entities to which the family had donated, Tufts University acknowledged how educational decisions at the institution were inappropriately shaped in a fashion that served Purdue Pharma’s interests (e.g., suppressing a book documenting the opioid crisis, using corporate materials in teaching), and how the company made use of its Tufts connections, including at one point having a Tufts faculty member appear in an advertisement for the company’s products.39,135 Similar influence processes have been documented at other universities.136

The pharmaceutical industry also attempts to shape education in academic medical centers through on-campus representatives. Some evidence of the impact of these activities comes from evaluations of academic medical centers that restrict them, which often though not always experience decreases in prescriptions for marketed drugs.137 For example, in a study of 85 medical centers, restrictions on receiving gifts, limits on accepting paid speaking and consulting engagements, requirements to disclose industry ties, and bans on sales representatives were associated with 8.8% lower volume of opioids prescribed.138

Professional societies, which are leading providers of education both for clinicians and the public, are another potential site of unacknowledged industry influence. To take a recent case in point, five leading pain specialists publicly resigned from the taskforce on the 2021 Global Year Against Back Pain139 established by the International Association for the Study of Pain and the European Pain Federation. The scientists resigned to protest undisclosed links between the task force and the opioid manufacturer Grünenthal, bringing the education campaign into public disgrace even before it was launched.

Recommendations for reducing pharmaceutical industry influence on the practice and education of prescribers

Recommendation 1a: Curtail pharmaceutical product promotion

The simplest way to curtail prescriber-focused marketing is for lawmakers to ban it outright. Some individual states in the USA and health care systems have restrictions of this form, but they are not national in scope.144,145 In contrast, in Germany, professional traditions and laws generally forbid the provision of gifts or benefits to physicians that could influence future prescribing decisions or could be considered a reward for past prescribing decisions.146 In 2018, Canada’s Health Minister finally asked opioid manufacturers to voluntarily cease marketing to physicians, and in 2019 Health Canada announced its intent to put formalized rules in place to legally restrict the content of such promotion.147

The Commission recommends that the USA make comparable national policy moves immediately. Because of its ability to mislead patients, including to the point where they pressure prescribers to make suboptimal care decisions,41 the Commission also recommends that the USA join the rest of the world in banning direct-to-consumer advertising of pharmaceuticals that makes therapeutic claims.

Because the current members of the U.S. Supreme Court have ruled that corporations have the same speech rights as individuals, a ban on pharmaceutical advertising is unlikely in the near term. A less potent but still valuable interim alternative is to remove the ability of pharmaceutical companies to deduct the costs of advertising from their income when filing annual tax returns. This policy, which has been proposed both by Republican and Democratic U.S. Senators and by President Joe Biden would raise the cost of advertising relative to other investments the industry might make, for example in research and development.148,149

Last but not least, the Commission recommends that pharmaceutical industry involvement in the design and implementation of electronic prescribing systems be forbidden. Such systems should be designed solely to improve patient care and should not be exploited as a commercial platform.

Recommendation 1b: Decouple pharmaceutical industry donations to universities and professional associations from control over the content of medical education.

Any for-profit industry given the power to shape educational programming that could increase sales of its products is very likely to take advantage of the opportunity. Universities and professional societies should therefore only accept educational funding that is donated into a common pool over which the pharmaceutical industry has no input of any kind. The nature and content of courses on prescribing should be established by scientists, clinicians, and educators free of industry ties. These principles have gathered increasing support across medicine over the last decade and are embraced in the Council of Medical Specialty Societies’ code for interactions with industry150 and in the Accreditation Council of Continuing Medical Education standards for continuing medical education.151 These principles should also be supported by accreditors of medical, nursing, dental, and pharmacy schools. Finally, it should go without saying that concealing pharmaceutical industry support of clinician or public education efforts, including conferences given by professional associations and patient advocacy organizations, is never acceptable.

Industry influence over the regulation of addictive pharmaceuticals

OxyContin is a highly potent extended release opioid that was approved for wide use by the FDA under the fraudulent premise that it was less addictive than other opioids, a mistake that stained the FDA’s reputation. But the FDA was not the only pliant regulator. Between 1994 to 2015, the quota of oxycodone that the Drug Enforcement Administration permitted to be legally manufactured was raised over 20 times from 3.85 million grams in 1994 to a high of 153.75 million grams in 2013.5

Drug approval is intended to be one step in a process that is modifiable or even reversible if problems arise, but further regulatory failures prevented such corrections from happening for years in the opioid crisis. Had post-marketing studies of the many approved opioid medications been promptly conducted, the risks of addiction would have come to light more quickly. Had effective risk evaluation strategies been rolled out to prescribers, opioids might have been prescribed more safely. And had the second wave of regulators who should have been activated after a drug was approved (e.g., medical boards, accreditation organizations) acted more quickly, lives might have been saved. Understanding the role of industry influence thus must go beyond drug approval to what happens afterwards, and must go beyond illegal conduct to conduct that is within the bounds of defective laws.

Industry clearly often succeeds at “regulatory capture”, i.e., having corporate interest prioritized over the public interest. A common method of doing this is luring experienced individuals out of the regulatory world with lucrative salaries. This revolving door not only deprives regulators of talent, but also communicates to current official holders and regulatory agency staff that their future earnings could be shaped by whether the decisions they make today please the industries they oversee.152

Former U.S. Congressman Billy Tauzin, for example led the crafting of Medicare legislation that dramatically expanded government purchasing of pharmaceutical products while simultaneously forbidding the government to bargain for lower drug prices. The day after his term ended, Tauzin became a leading pharmaceutical industry lobbyist at more than ten times his Congressional salary.153

Most cases are less dramatic. When drug distribution firms oversupplied opioids and violated laws requiring that they report such suspicious shipments, they were investigated by the Drug Enforcement Administration. One of the tactics the industry used to fight these charges was to hire away key Drug Enforcement Administration employees to work for their side.154 Multiple federal prosecutors in the USA who had initially been openly critical of Purdue Pharma recanted when they subsequently were hired by the company.5 The FDA can be subject to similar pressures.152 The FDA official who oversaw the agency’s approval of OxyContin, subsequently began working for Purdue Pharma at a salary which federal prosecutors allege was triple his government pay.155 Similar concerns have been raised across the FDA’s portfolio.156

Under the law in the USA, once a risky drug is approved, monitoring those risks and educating prescribers about them is substantially at the pharmaceutical industry’s discretion. To protect public health, any post-approval risks or harms of medicines should be monitored, and prescribers should be equipped to mitigate such risks and harms if they arise. Rather than have the FDA do such studies itself, the law empowers it only to mandate that manufacturers conduct them. Many of these “mandated” surveillance studies have not even begun years after an approved drug is in use, others have been completed late, and still others have not been conducted at all.44,157 Those studies have been conducted often have not analyzed or revealed their data43 or were designed in a fashion that made detecting adverse effects very unlikely.158 This is not surprising given that identifying risks to approved drugs is of benefit to the public but by definition can reduce sales and profits for drug manufacturers.

Similarly, when the FDA has mandated that manufacturers create and evaluate risk evaluation and mitigation strategies to help physicians prescribe opioids more safely, compliance has been grudging and there is no evidence that patients have significantly benefitted.159,160 Target numbers for training physicians are often not met,159,161 the training materials themselves are often of questionable utility,162,163 mandated evaluations have often not been conducted,159 those evaluations conducted by industry are rarely methodologically rigorous,84–88 and when evaluations do provide data, industry has rarely implemented changes to risk evaluation and mitigation strategies in response.164

Theoretically, the FDA has the power to respond to such industry non-compliance by pulling a medication from the market, but rarely exercises it. National medical leaders have advanced different explanations for this. Dr. Marcia Angell, former editor of The New England Journal of Medicine suggests that the FDA is reticent because it sees its institutional purposes and incentives as aligned with increasing the number of drugs on the market.165 Indeed, in recent decades, successive Congresses and Presidential administrations have made changes to the FDA’s authorizing legislation specifically intended to have it approve medications more quickly.44,166

Dr. Drummond Rennie, former deputy editor of JAMA, argues that the FDA is wary of offending pharmaceutical manufacturers because user fees provide part of its budget, which causes the agency to see industry rather than the public as its client.44 Whether or not this is correct, the FDA may make some decisions out of rational fears of the pharmaceutical industry’s considerable influence in Congress, which the Commission discusses elsewhere in this report. In any event, the FDA cannot be blamed for following a law which gives more control over post-approval surveillance and risk evaluation and mitigation strategies to the pharmaceutical industry than to the government.

Once a medication is approved, another layer of regulators comes into play. This includes governmental agencies (e.g., state and provincial medical boards) as well as non-governmental organizations which are formally ceded regulatory powers by government (e.g., accreditation bodies specifically recognized in legislation, such as The Joint Commission). Industry connections to such bodies can be extensive. In the USA, the Joint Commission accredits hospitals and other health care organizations and its accreditation is formally recognized in the law of many states. A U.S. Government Accountability Office investigation found that the Joint Commission’s pain management education programs were funded and co-authored by opioid manufacturers, and that the partnership with Purdue Pharma “may have facilitated its access to hospitals to promote OxyContin.”167 The Joint Commission also promulgated in its accreditation standards the concept that pain is the “fifth vital sign”, putting pressure on health care organizations to increase opioid prescribing.168 The Joint Commission began de-emphasizing the term in 2002, later clarified that the “fifth vital sign” concept was intended to raise awareness of pain, and also acknowledged that it had been misinterpreted to mean that pain should be assessed at every patient contact, a practice which tended to fuel opioid prescribing.168 Clinical practice guidelines written by individuals with ties to opioid manufacturers have echoed inaccurate promotional messages, including two such guidelines that have been retracted by the World Health Organization and led it to strengthen its conflict of interest policies.169

Provincial and state medical boards also have power through adjudicating of patient complaints against prescribers, guiding practice norms in the field, and advising legislators and regulators. Industry is also involved at this level. For example, the U.S. Federation of State Medical Board’s guidelines on opioid prescribing were developed with the aid of individuals with extensive industry ties, and in 2003 distribution of the guidelines was funded by Purdue Pharma.170

Even were it possible for medical regulators to have extensive industry ties but be in no way affected by them in their professional judgements, public perception of potential corruption still matters. Any regulatory standard for opioid prescribing or pain care -- even one involving some individuals who have the highest of motives -- risks significant loss of credibility if funded by companies that have been criminally convicted of knowingly misrepresenting the risks and benefits of opioids.171

Recommendations for limiting industry influence over the regulation of addictive pharmaceuticals

Recommendation 1c: Close the “revolving door” of officials overseeing the pharmaceutical industry leaving government to work on the industry’s behalf.

Transfers of knowledge and skills between the public and private sector are not necessarily harmful to the public good and indeed may sometimes benefit it.172 But when such transfers occur for the purpose of promoting industry capture of regulators, society suffers not only in terms of public health but also in terms of increased cynicism and political alienation. The public good would be served by extending the length of “cooling off” periods in state and federal law constraining lobbying on behalf of an industry that an elected or appointed official used to oversee (e.g., mandating a two-year period, as envisioned in one proposed piece of legislation).173–175 Positive incentives should also be considered. For example, civil servants working in regulatory agencies could be paid higher salaries, with added retention incentives for senior officials with particularly deep knowledge of regulatory processes.

Recommendation 1d: Post-FDA approval data collection on adverse effects of medications and provider education on risk mitigation should be made the responsibility of government.

Gathering data on post-approval drug safety and on how to mitigate identified risk are essential for reducing drug-related morbidity and providing quality health care more generally. Current law entrusts the conduct of these activities, which are vital to public health, to a for-profit industry whose revenue would be threatened by prompt, competent, and transparent assessment of and education about the risks of approved medications. That so much of the industry’s work in this area is slow, low quality, or in some cases even non-existent is not surprising. The Commission recommends a fundamental change in approach: direct governmental control over post-approval drug surveillance and of the development, implementation, and evaluation of risk evaluation and mitigation strategies is needed.

Congress must decide where in government these activities are based, but to avoid conflicts of institutional interest they should not be overseen by FDA’s Office of New Drugs, which generally sees its charge as bringing more medications to market. The funding and authority to monitor and mitigate post-approval drug risks -- including the power to pull an approved drug from the market if warranted -- could be given to drug safety officials within the FDA, or, as some have proposed, to an independent agency outside of the FDA.44

Recommendation 1e: Bodies that have legal or regulatory power to shape prescribing should accept no funding from industry and include no individuals with direct financial ties to industry.

We have already discussed the need to insulate from industry influence organizations that have some ability to persuade prescribers (e.g., medical schools). The need for firewalls is even stronger in areas where an organization has formal legal or regulatory power to shape prescribing. The Federation of State Medical Board’s eventual decision to stop accepting funding from the pharmaceutical and medical device industry was a positive step and should be uniformly adopted by USA state and Canadian provincial medical boards.

Prohibitions against industry influence in this arena are justifiable entirely because of concerns about protecting patients. But it bears considering that such rules also protect prescribers who practice ethically and compassionately. Just like patients, physicians have a right to expect that the rules under which prescribing is conducted were set based on scientific evidence and intended solely to benefit patients, not to enrich industry.

Finally, the Commission notes that the spate of multi-billion dollar lawsuits surrounding the opioid crisis in the United States can also create conflicts of interest. The restrictions on regulatory bodies proposed in this recommendation should apply not only to material connections to the pharmaceutical industry, but also to law firms suing some element of the industry and individuals hired as expert witnesses by those firms.

Industry influence over the political process

Election campaigns in the USA are expensive, and office holders are attuned to raising sufficient funds to compete in them. Corporations and their employees have always been significant donors to political campaigns, but changes in campaign financing laws, most notably the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United vs. Federal Election Commission,176 have removed almost all limits on their political campaign contributions (Canada in contrast has maintained caps on donation amounts). Discussing the impact of this decision across all areas of corporate influence is beyond the Commission’s scope and expertise. We instead make the more focused observation that in the specific case of the pharmaceutical industry, the removal of donation limits plausibly worsened the opioid crisis and increased the risk of subsequent crisis involving prescribed medications.

The power that lobbying and unconstrained political donations give the pharmaceutical industry is hard to overstate. Over a 10-year period, groups attempting to place some limits on opioid prescribing (e.g., activist groups of people who had lost loved ones to overdose) spent $4 million on lobbying and campaign contributions in USA state legislatures. Over the same period, the pharmaceutical industry spent $880 million to persuade state legislators to serve their business interests.177 Even under the conservative assumptions that only a minority of that money was spent on opioids and that political donations from law firms suing the opioid industry have recently entered the political equation as a partially countering force, the opioid industry’s lobbying power is clearly enormous.

The financial power of the pharmaceutical industry at the federal level is equally undeniable. For example, when the Drug Enforcement Administration caught opioid distribution companies breaking the law by not reporting massive, suspicious, shipments of opioids to particular communities, the companies asked Congress to pass a law curtailing the agency’s power to conduct such investigations. The industry had contributed $1.5 million to the campaigns of 23 lawmakers who sponsored the new law, including US$100,000 to Representative Tom Marino, who led the law’s passage in the House of Representatives.154 Soon afterward, President Trump nominated Marino to become the Director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy.67

In addition to influencing policymakers with donations, opioid manufacturers have also followed the lead of other industries (tobacco, fossil fuels) by engaging in “astroturfing”, i.e., creating or infiltrating putatively grassroots groups which are covertly funded by industry and carry its messages. A notable example in Canada was a coalition of industry-funded “patient advocacy organizations” arguing against a government effort to reduce drug prices.42 A prominent USA example is the American Pain Foundation which publicly presented itself as an independent voice of pain patients while echoing opioid manufacturers’ messages about the ample benefits and minimal risks of opioids.178 When it came to the attention of investigative journalists and the Congress that 88% of the American Pain Foundation’s annual budget was provided by opioid manufacturers and medical device makers, and that it closely coordinated its public messaging with industry representatives, the organization was dissolved.179,180 Other non-profit organizations in the opioid arena (e.g., Pain UK) have been criticized by regulators for failing to disclose links with opioid manufacturers.181

Surveys of patient advocacy groups across all areas of health estimate that between 67–83% receive funding from for-profit entities (e.g., pharmaceutical and/or medical device industries).182,183 One study of advocacy groups reported that 88% publish lists of donors in annual reports or on a website, but only 2% explicitly state that all corporate donors are listed, and 43% do not report any information on amount of donations received.182 Extensive, rising, and underreported financial support of patient advocacy groups by the pharmaceutical industry has also been documented in other nations.184

Recommendations for countering industry influence over the political process

Recommendation 1f: The USA should restore limits on the political campaign donations of pharmaceutical companies.