Abstract

Background:

Sleep disorders have a comparatively high prevalence worldwide and create a burden on the health system. Pharmacological agents used for insomnia are associated with considerable side effects. Therefore, searching for safe and effective agents from plant-based natural sources is a worthy effort. Jatamansi (Nardostachys jatamansi DC.) rhizome has been recommended for insomnia and mental conditions in the Indian system of medicine.

Aim:

This study aimed to determine central nervous system (CNS) depressant activity of Jatamansi (N. jatamansi) rhizome on experimental animals.

Materials and methods:

Gross behavior study and open field test (locomotor activity) were performed by using Charle’s foster albino rats whereas rota-rod test and pentobarbital-induced sleep test in Swiss albino mice. Animals were divided into 3 groups (per model) having six animals in each group. The control group was treated with water, the standard group with diazepam and the test drug with powder of N. Jatamansi rhizome. Results were calculated by one-way ANOVA and post hoc test with P < 0.05 as significant.

Results:

Data suggested that Jatamansi did not produce a significant effect on the behavior of animals. It reduced the horizontal activity significantly (P < 0.001) in the open field apparatus. The test drug did not show a significant decrease in latency of fall-off time in rota-rod performance in mice. Still, it exerted a significant effect by a reduction in latency of onset of sleep (P < 0.01) and also extended the total duration of sleep (P < 0.05) in albino mice in comparison to the control group.

Conclusion:

This study shows that Jatamansi rhizome powder possesses CNS depressant activity without affecting gross behavior and muscle coordination in rats.

Keywords: Central nervous system depressant, insomnia, Jatamansi, Nardostachys jatamansi

Introduction

Studies have shown the prevalence of insomnia in 10%–30% of the population worldwide,[1] while in India, it is 33%.[2] The high prevalence of insomnia is observed mainly in psychiatric patients.[3] Chronic sleep disorders lead to several health consequences such as poor memorizing, emotional instabilities, mental health disorders, changes in the immune response, and increased risk and severity of long-term diseases or conditions, such as high blood pressure, heart disease.[4,5] Benzodiazepines, the most commonly used medications for sleep disorders, are accompanied by side effects such as drug dependence, drowsiness, lethargy, fatigue, amnesia and cognitive impairment.[6,7] Hence, an attempt to search for new plant-based substances is increasing to find safer alternative drugs from ethnopharmacological claims based on traditional uses.

Nardostachys jatamansi DC. belonging to family-Valerianaceae is used for the treatment of depressive illness, convulsive affections, palpitation of heart, intestinal colic, high blood pressure, and dysmenorrhea.[8] The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India recommends its rhizomes in skin diseases, cellulitis, disturbed mental state and insomnia.[9] It is used as a substitute for valerian and as an ingredient of many Ayurvedic drug formulations such as Mamsyadi Kwatha used for sleep disorders.[10] Sesquiterpenes and coumarins are major active principles in the herb.[11] Major sesquiterpenes from oil are d-nardostachone, valeranone and jatamansone.[12] The active principle, jatamansone is reported to have tranquilizing, antiemetic, sleep-regulating, and anticonvulsant activities.[13,14] Reported activities in essential oil are antimicrobial, antifungal, hypotensive, anti-arrhythmic and anticonvulsant.[15] Alkaloidal fraction from rhizome possesses hypotensive action.[16]

Most experimental studies have been conducted on various extracts, essential oils, or isolated components from Jatamansi. However, in Ayurveda, the drug is used clinically as a whole in crude form, not in an isolated component. Crude drugs and their isolated fraction do not behave similarly in a biological system and therefore may not have similar activity. Hence, a crude form of the herb is required to be investigated for the presence of activities reported in isolated components or fractions. Keeping it in view, the central nervous system (CNS) depressant activity of the whole powder of Jatamansi rhizome was evaluated on experimental models.

Materials and methods

Animals

Charle’s foster albino rats of either sex weighing 200 ± 20 g (open field test) or Albino mice of 30 ± 5 g (Rotarod and Pentobarbital-induced sleep test) were used for the experiments. The animals were obtained from the animal house attached to the institute. They were housed in the departmental animal house at 23 ± 2°C and relative humidity of 50%–60%, light and dark cycles of 12 h, respectively, for one week before and during the experiments. Animals were allowed of free access to standard laboratory feed and water ad libitum. Animals were fasted overnight before the experiment. Experimental protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Ph. D./IAEC/13/2013/03) following the guideline formulated by Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals, India.

Drug

The dried rhizome of Jatamansi was obtained from in-house pharmacy, authenticated and herbarium was deposited in Pharmacognosy laboratory of the Institute (Phm. 2013/14/6104). The dried rhizome was powdered, sieved through 120 no sieve and stored in an airtight container. At the time of drug administration, an aqueous suspension of test drug powder was prepared in distilled water and administered orally through oral feeding cannula in experimental animals.

Dose

The human dose for Jatamansi powder is 2–3 g/day as per Ayurvedic Pharmacoepia of India.[9] Animal dose was converted by extrapolating the human dose to animal dose based on the body surface area ratio.[17] Considering upper therapeutic dose of Jatamansi powder, the dose for albino rats was calculated as 270 mg/kg and for mice as 390 mg/kg body weight.

Gross behavior test

The Charles Foster albino rats of either sex were divided into three groups, consisting of six rats per group. Group I (NC) was kept as the control group and was given distilled water (10 ml/kg, po), group II (J) was kept as test drug-treated group and received aqueous suspension of Jatamansi powder (270 mg/kg, po), and group III (SC) was treated with standard drug, diazepam (4 mg/kg, po). Charle’s Foster rats were individually exposed to center of open arena for recording the behavioral changes. For CNS depression-hypoactivity, passivity, relaxation, narcosis and ataxia; autonomic nervous system (ANS) activities- ptosis, exophthalamous; and CNS stimulation- hyper activity, irritability, stereotypy, tremors, straub tail and analgesia were measured.[18] The procedure involves assigning scores on 0-3 point scale as per the average intensity of the phenomenon observed. Observations were made before and at every hour after drug administration for the first 4 h and then at 24 and 48 h.

Open-field behavioral assay

A study was conducted to evaluate the effect of the drug on spontaneous locomotor activity of Charle’s Foster rats as grouping mentioned in gross behavior test. One hour after drug administration, the animals were individually exposed to an open field apparatus (square box of 96 cm × 96 cm with a sidewall of 15 cm height having 36 squares).[19] Each rat was placed in the arena for 10 min and activity was observed. The parameters recorded were number of squares crossed, number of rearing, freezing time (duration of immobility) and number of fecal pellets expelled.

Rotarod performance

Centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxant activity was evaluated using Rotarod performance on Swiss albino mice. The mice were first trained on Rotarod apparatus, and the mice who remained on rotarod for 2 min or more after successive trials, were included and divided into three groups, each consisting of six mice of either sex. Group I was kept as the control group and given distilled water (10 ml/kg, po), group II was kept as test drug treated group and received aqueous suspension of Jatamansi powder (390 mg/kg, po) and group III was treated with standard drug, diazepam (3 mg/kg, po). The mice were placed on a horizontal rotating metal rod having a diameter of 32 mm, rotating at the rate of 25 RPM (round per minute). The latency of fall-off time from the rotating rod was noted initially, after 1 h and 3 h of drug administration for each animal.[20]

Pentobarbital-induced sleep test

Swiss albino mice were used to evaluate the efficacy of the drug on prolongation of pentobarbitone-induced sleeping time.[21] The albino mice of either sex were divided into three groups each consisting of six mice as mentioned in Rotarod performance. The doses were administered once orally to mice of the respective group. One hour after administration of doses, pentobarbitone sodium (45 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally. The mice were observed for the latency of onset of sleep and the total duration of sleep.[22,23]

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad PRISM, version 8.4.1, GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, CA, USA, statistical software. Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The data generated during the study were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for inter-group comparisons. P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In gross behavior, test drug Jatamansi insignificantly increased the mean score of hypoactivity related parameter up to 6 h while did not affect the CNS stimulation or ANS activity at any point of time after its administration. Significant increase in hypo-activity, passivity, relaxation, and ataxia were observed in the standard control diazepam treated group in comparison to the normal control group [Table 1].

Table 1.

Effect of test drugs on gross behavior parameters in albino rats

| Parameter of CNS depression | Groups | Initial | 1/2 h | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 6 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypo activity | NC | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| J | 0±0 | 0.5±0.34 | 1±0.45 | 1±0.45 | 0.83±0.40 | 0.67±0.33 | 0.67±0.33 | |

| DM | 0±0 | 2.67±0.21** | 2.83±0.17** | 2.83±0.17** | 1.83±0.17** | 1.33±0.21** | 0.5±0.2 | |

| Relaxation | NC | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| J | 0±0 | 0.17±0.17 | 0.5±0.22 | 0.5±0.22 | 0.5±0.22 | 0.33±0.21 | 0±0 | |

| DM | 0±0 | 3±0** | 3.0±0** | 2.67±0.21** | 1.33±0.21** | 1.17±0.17** | 0.3±0.2 | |

| Passivity | NC | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0±0 |

| J | 0±0 | 0±0 | 0.5±0.22 | 0.67±0.33 | 0.67±0.33 | 0.83±0.40 | 0.5±0.22 | |

| DM | 0±0 | 2.33±0.21** | 2.67±0.21** | 2.17±0.17** | 1±0** | 1±0** | 0.3±0.2 |

**P<0.01 in comparison to normal control, Data: Mean±SEM. NC: Normal control group (water), J: Jatamansi group, DM: Diazepam group, SEM: Standard error of mean, CNS: Central nervous system

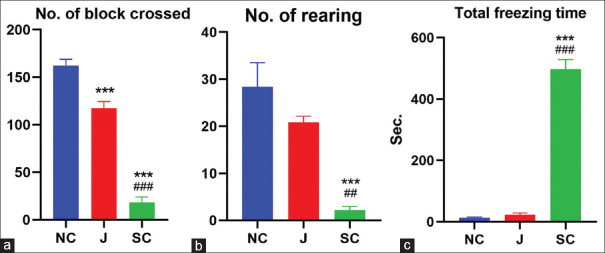

Rhizome powder of Jatamansi reduced the horizontal activity (number of squares crossed) significantly in comparison to normal control (P < 0.001) in the open field apparatus. A significant alteration was not observed in other parameters such as the number of rearing (vertical activity) and total freezing time in albino rats treated by test drug. Standard control (diazepam) decreased horizontal activity and total freezing time significantly compared to both groups (P < 0.001); whereas vertical activity was also decreased compared to NC (P < 0.001) and test drug (P < 0.01) groups [Table 2 and Figure 1a-c].

Table 2.

Effect of test drugs on albino rats in open field test

| Groups | Number of block crossed | Number of rearing | Total freezing time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal control | 162.2±6.67 | 28.33±5.17 | 12.5±3.04 |

| Jatamansi | 117.5±6.91*** | 20.83±1.33 | 22.5±6.08 |

| Diazepam | 18.4±5.69***,### | 2.2±0.73*,## | 497.2±31.33***,### |

***P<0.001, when compare to control group; ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001, when compare to Jatamansi treated group (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Post hoc test), Data: Mean±SEM. SEM: Standard error of mean

Figure 1.

Effect of test drugs on albino rats in open field test. (a) Number of block crossed. (b) Number of rearing. (c) Total freezing time. (Mean ± standard error of the mean; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to control; #P < 0.05 compared to Jatamansi-treated group), NC: Normal Control, J: Jatamansi, SC: Standard Control

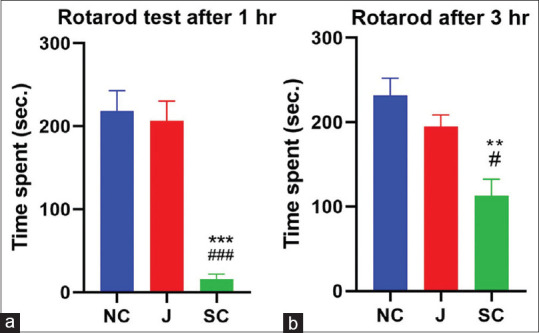

On the rotarod test, Jatamansi did not show a significant decrease in latency of fall off time after 1 h and 3 h compared to the control group on rotarod performance. Diazepam-treated group significantly decreased in fall of time compared to both groups (P < 0.001) after 1 h of drug administration and also after 3 h (P < 0.01, NC) (P < 0.05, test drug) [Table 3 and Figure 2a and b].

Table 3.

Effect of test drugs on rotarod performance of Swiss albino mice

| Groups | Fall off time (s) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| After 1 h | After 3 h | |

| Normal control | 218.4±24.48 | 231.6±20.48 |

| Jatamansi | 206.8±23.46 | 194.6±14.03 |

| Diazepam | 16±6.07***,### | 113.2±19.55**,# |

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001, when compare to control group, #P<0.05, ###P<0.001, when compare to Jatamansi treated group (One-wayAnova followed by Tukey’s Post hoc test), Data: Mean±SEM. SEM: Standard error of mean

Figure 2.

Effect of test drugs on Rotarod performance of albino mice. (a) After 1 h. (b) After 3 h. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared to control; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001, compared to Jatamansi-treated group), NC: Normal Control, J: Jatamansi, SC: Standard Control

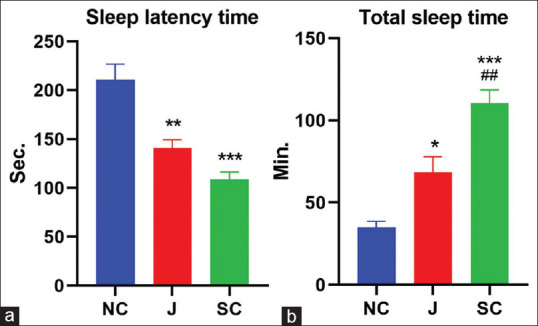

On pentobarbitone-induced sleeping time, the test drug-treated group showed a significant reduction in latency of onset of sleep (P < 0.01) and also extended the total duration of sleep in albino mice in comparison to the control group (P < 0.05). Diazepam exerted a significant effect by reducing latency of sleep and increasing total sleep duration in mice when compared to the control group (P < 0.001) [Table 4 and Figure 3a and b].

Table 4.

Effect of test drugs on pentobarbital-induced sleep in Swiss albino mice

| Groups | Latency of onset of sleep (s) | Total sleep time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal control | 210.8±15.84 | 35.0±3.57 |

| Jatamansi | 140.7±8.65** | 68.46±9.49* |

| Diazepam | 108.5±7.82*** | 110.4±8.13***,# |

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 when compared to control group, #P<0.05 when compared to Jatamansi treated group (One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s Post hoc test), Data: Mean±SEM. SEM: Standard error of mean

Figure 3.

Effect of test drugs on pentobarbital-induced sleep. (a) Latency of onset of sleep. (b) Total sleep time.(*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to control; #P < 0.05 compared to Jatamansi-treated group), NC: Normal Control, J: Jatamansi, SC: Standard Control

Discussion

The attempts to search for novel plant-derived pharmacotherapies for psychiatric illness are progressively increasing in the past decade.[24] Anxiolytic herbs may potentially alleviate psychiatric disorders with minimal adverse effects.[25] Jatamansi, used to treat a wide range of disorders, has been primarily recommended for psychiatric illness traditionally. Essential oils and the component jatamansone have shown such activities experimentally. However, the study was conducted using a crude form of Jatamansi as this is the popular form of usage among indigenous medical practitioners.

Data suggested that Jatamansi did not produce any adverse effect on the behavior of animals grossly which indicates its safety profile at a given dose. The open-field test showed a significant decrease in spontaneous motor activity by reducing the number of horizontal movements. However, the test drug did not increase the number of rearing and total freezing time significantly, indicating only mild grade of sedative activity in Jatamansi. Reduction in locomotor activity may lead to soothing and sedation as a result of reduced excitability of the CNS.[26] Test drug did not produce significant muscle relaxant activity on Rotarod performance in albino mice, indicating the absence of muscle relaxant activity in the rhizome of Jatamansi.

Jatamansi potentiated the effect of pentobarbital by shortening sleep latency and prolonging total sleeping time in swiss albino mice, though not as remarkable as that of diazepam. Earlier reports suggest that the increase and decrease of pentobarbitone-induced sleep time can be a useful tool for examining the stimulatory or inhibitory effects on CNS, especially for investigating influences on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) ergic systems in CNS.[24]

The previous report suggested that ethanolic extract of Jatamansi significantly altered locomotor activity.[25] Jatamansone exerted a tranquilizing effect in mice and monkeys[13] and a significant reduction in hyperactivity and improvement in restlessness and aggressiveness on hyperkinetic children similar to amphetamine.[8] Alcoholic extract of Jatamansi root increased the level of GABA on acute administration and increased the levels of most of the central biogenic amines and inhibitory neurotransmitters on chronic administration.[27] Thus, earlier studies indicate isolated compounds or extracts exert highly significant sedative activity while data of this study indicates crude form of drug administered in recommended dose produced comparatively mild CNS depressant activity.

Benzodiazepines have been used for the treatment of insomnia and other CNS disorders predominantly. These drugs potentiate the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter of GABA, by binding to a specific site on the GABAA receptors to produce allosteric enhancement of anion flux through this ligand-gated chloride channel.[28,29] Most sedative-hypnotics used in the treatment of insomnia target the GABAA receptor. As test drug increased the duration of sleep time induced by a sub hypnotic dose of pentobarbitone, it can be stated that the drug may interact with pentobarbitone on the CNS via GABAA-ergic mechanisms in CNS.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that Jatamansi rhizome powder possesses CNS depressant activity without affecting gross behavior and muscle relaxation in animals. It can be helpful in the treatment of insomnia, as claimed in Ayurveda by clinical trials.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:487–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhaskar S, Hemavathy D, Prasad S. Prevalence of chronic insomnia in adult patients and its correlation with medical comorbidities. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:780–4. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.201153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hombali A, Seow E, Yuan Q, Chang SH, Satghare P, Kumar S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of sleep disorder symptoms in psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orzeł-Gryglewska J. Consequences of sleep deprivation. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2010;23:95–114. doi: 10.2478/v10001-010-0004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zaharna M, Guilleminault C. Sleep, noise and health:Review. Noise Health. 2010;12:64–9. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.63205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin CE, 3rd, Kaye AM, Bueno FR, Kaye AD. Benzodiazepine pharmacology and central nervous system-mediated effects. Ochsner J. 2013;13:214–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uzun S, Kozumplik O, Jakovljevic M, Sedić B. Side effects of treatment with benzodiazepines. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22:90–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khare CP. Indian Medicinal Plants:An Illustrated Dictionary Indian Medicinal Plants. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 433–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anonymous. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopeia of India, Part I, Vol. I. Reprint edition. New Delhi: Govt. of India, M/o Health and Family Welfare Dept. of Indian System of Medicine and Homeopathy; 2001. pp. 52–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shreevathsa M, Ravishankar B, Dwivedi R. Anti depressant activity of Mamsyadi Kwatha:An Ayurvedic compound formulation. Ayu. 2013;34:113–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-8520.115448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatterjee B, Basak U, Dutta J, Banerji A, Prange NT. Studies on the chemical constituents of N. jatamansi. Chem Inform. 2005;36:17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rücker G, Tautges J, Sieck A, Wenzl H, Graf E. Isolation and pharmacodynamic activity of the sesquiterpene valeranone from Nardostachys jatamansiDC. Arzneimittelforschung. 1978;28:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arora RB, Singh M, Saxena YR. A biochemical approach to the mechanism of action of Jatamansone. Life Sci. 1962;1:571–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora RB. Cardiovascular pharmacotherapeutics of six medicinal plants indigenous to Indian, A ward Monog, Ser, No-1. New Delhi: Hamdard National Foundation; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahu R, Dhongade HJ, Pandey A, Sahu P, Sahu V, Patel D, et al. Medicinal properties of Nardostachys jatamansi(A Review) Orient J Chem. 2016;32:859–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bose BC, Gupta SS, Vijayvarigiya R, Saifi AQ, Bhatnager JN. Preliminary observation on the pharmacological action of various fractions of Nardostachys jatamansiDC. Curr Sci. 1957;26:278. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paget GE, Bernes JM. Evaluation of drug activities. In: Laurence DR, Bacharacha AL, editors. Pharmacometrics. Vol. 1. New York: Academic Press; 1964. pp. 135–46. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morpurgo C. A new design for the screening of CNS-active drugs in mice. A multi-dimensional observation procedure and the study of pharmacological interactions. Arzneimittelforschung. 1971;21:1727–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattacharya SK, Satyan KS. Experimental methods for evaluation of psychotropic agents in rodents:I-Anti-anxiety agents. Indian J Exp Biol. 1997;35:565–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watzman N, Barry H, 3rd, Buckley JP, Kinnard WJ., Jr Semiautomatic system for timing rotarod performance. J Pharm Sci. 1964;53:1429–30. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600531142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rakhshandah H, Hosseini M. Potentiation of pentobarbital hypnosis by Rosa damascena in mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2006;44:910–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darias V, Abdala S, Martin-Herrera D, Tello ML, Vega S. CNS effects of a series of 1,2,4-triazolyl heterocarboxylic derivatives. Pharmazie. 1998;53:477–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolfman C, Viola H, Marder M, Wasowski C, Ardenghi P, Izquierdo I, et al. Anxioselective properties of 6,3'- dinitroflavone, a high-affinity benzodiazepine receptor ligand. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;318:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00784-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah VK, Choi JJ, Han JY, Lee MK, Hong JT, Oh KW. Pachymic acid enhances pentobarbital-induced sleeping behaviors via GABAA-ergic systems in mice. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2014;22:314–20. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2014.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razack S, Khanum F. Anxiolytic effects of Nardostachys jatamansi DC in mice. Ann Phytomed. 2012;22:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh N, Kaur S, Bedi PM, Kaur D. Anxiolytic effects of Equisetum arvense Linn. extracts in mice. Indian J Exp Biol. 2011;49:352–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prabhu V, Karanth KS, Rao A. Effects of Nardostachys jatamansi on biogenic amines and inhibitory amino acids in the rat brain. Planta Med. 1994;60:114–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-959429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnard EA, Skolnick P, Olsen RW, Mohler H, Sieghart W, Biggio G, et al. International union of pharmacology. XV. Subtypes of gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptors:Classification on the basis of subunit structure and receptor function. Pharmacol Rev. 1998;50:291–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohler H, Fritschy JM, Rudolph U. A new benzodiazepine pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:2–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]