Abstract

Background

Despite abundant data on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, 3 important knowledge gaps continue to exist, i.e., 1) studies from low-/middle income countries (LMICs); 2) studies in the later period of the COVID-19 pandemic; and 3) studies on non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients. To address the knowledge gaps, we assessed the prevalence of and the risk factors for mental health symptoms among non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients in one LMIC (Indonesia) during the later period of the pandemic.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in September 2020 in East Java province, Indonesia. Study population consisted of non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients who were diagnosed based on reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction results from nasopharyngeal swab. Mental health symptoms were evaluated using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21.

Results

From 778 non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients, 608 patients were included in the analysis. Patients’ median age was 35 years old and 61.2% were male. Of these, 22 (3.6%) reported symptoms of depression, 87 (14.3%) reported symptoms of anxiety, and 48 (7.9%) reported symptoms of stress. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that females were more likely to report symptoms of stress (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.98, p-value = 0.028); healthcare workers were more likely to report symptoms of depression and anxiety (aOR = 5.57, p-value = 0.002 and aOR = 2.92, p-value = 0.014, respectively); and those with a recent history of self-quarantine were more likely to report symptoms of depression and stress (aOR 5.18, p = 0.004 and aOR = 1.86, p = 0.047, respectively).

Conclusion

The reported prevalence of mental health symptoms, especially depression, was relatively low among non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients during the later period of the COVID-19 pandemic in East Java province, Indonesia. In addition, several risk factors have been identified.

Introduction

Since 11 March 2020, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has been classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization [1]. Currently, this virus has infected more than 500 million people and cause over 6 million deaths worldwide [2]. As human-to-human transmission occurs upon close contact with an infected person via respiratory droplets or aerosols [3], various preventive public health measures such as quarantine, social distancing, curfews, and lockdowns were implemented to prevent the spread of infection [4].

While these measures were deemed effective in limiting progression of the pandemic, they were not without consequences. People had to abruptly change their daily routines, working models, and social interactions. For example, working parents had to also mind their child(ren) while working from home, all meetings had to be switched from offline to online, business and leisure trips had to be cancelled, and physical contact such as handshakes or hugs were even prohibited. Hence, an increase in the prevalence of individuals with mental health symptoms was to be expected [5–7].

In the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, only little attention was paid to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health [8]; but now, a great number of studies on this topic have been published. In a recent meta-review of meta-analyses, the prevalence of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic was reported to be 26.93% and 27.77%, respectively [9]. These values are strikingly higher compared to pre-pandemic era, where the prevalence was estimated to be 4.4% for depression and 3.6% for anxiety [10]. Additionally, several risk factors that could adversely affect mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic have been identified, such as age, gender, educational background, socioeconomic status, marital status, the presence of children, occupation as healthcare worker (HCW), and a history of self-quarantine [11–13]. Nevertheless, despite the growing body of scientific literature on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, 3 important knowledge gaps exist.

First, although the COVID-19 pandemic has affected all countries around the globe, its impact on mental health varies across countries, with mental health symptoms being more prevalent in low-/middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to high-income countries [14]. Even so, most of the studies that have evaluated the impact of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic originated from China, while studies from LMICs are lacking [15–17]. Second, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health differs across time periods, with mental health symptoms being more severe in the beginning of the pandemic and become significantly milder in the following months [18]. Nonetheless, majority of the studies that evaluated mental health were conducted in the beginning of the pandemic [16, 18, 19], which may overestimate the magnitude of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, previous studies have shown that adverse mental health symptoms are more prevalent among COVID-19 patients compared to the general population or HCWs [12, 14, 16, 20, 21]. Even so, studies assessing mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic rarely focused on the COVID-19 patients [22]. Among COVID-19 patients, those who are hospitalized are at higher risk of having adverse mental health symptoms compared to those who are not hospitalized [23–25]. This is because most of the hospitalized patients are patients with severe COVID-19 symptoms [26], and patients with severe COVID-19 symptoms are more likely to have adverse mental health symptoms than the non-severe one [27, 28]. Nevertheless, majority of COVID-19 patients are asymptomatic or presented with only mild symptoms that do not require hospitalization [24, 25, 29–32]. However, data pertaining to the mental health condition of non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients are lacking [33]. In addition, no study has explored the risk factors of adverse mental health symptoms in this group of patients.

Thus, to address the aforementioned knowledge gaps, we conducted a study in Indonesia, one of the LMICs in Southeast Asia, during the later period of the COVID-19 pandemic, with non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients as the study population.

Materials and methods

Study design and study population

This cross-sectional study was conducted between 1 and 30 September 2020 in East Java province, Indonesia. During this period, the number of cases was the highest in the country since the beginning of the pandemic [34]. Among 34 provinces in Indonesia, East Java province was the province with the second highest confirmed cases and the highest mortality rate [35].

The study population consisted of non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients. Respondents were recruited at the Indrapura Emergency Field Hospital, the largest government-owned quarantine facility in East Java province, Indonesia. To be admitted to this quarantine facility, patients had to fulfill the following criteria: 1) Tested positive for COVID-19 on reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test; 2) Asymptomatic or having mild COVID-19 symptoms; and 3) able to take care of themselves.

To avoid the possible effect of facilitated quarantine on mental health, respondents were recruited before they underwent quarantine. When the patients came to the registration desk, those who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were verbally offered to participate in this study by the registrar. If the patients agreed to participate, they were asked to sign the informed consent and hand-filled the questionnaire on the spot.

Inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: age ≥ 18 years old, no history of mental illness, able to read and understand Bahasa Indonesia. History of mental illness among prospective respondents was ascertained by the registrar by verbally asking them if they had ever been diagnosed with mental illness or any mental health problems in the past.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical review board of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga prior to study initiation (approval number: 201/EC/KEPK/FKUA/2020; approval date: 19 August 2020). All respondents provided written informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study, and information about the study was given before the consent form was signed. Details that might disclose the identity of the respondents were omitted.

Research instrument

The research instrument used in this study was a questionnaire requesting data on sociodemographic characteristics and responses to the Indonesian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). Collected sociodemographic data were age, gender, education background, job status, marital status, number of children, and recent self-quarantine history. As this study also aimed to explore the possible risk factors of adverse mental health symptoms, the gathered sociodemographic data were based on literature concerning possible sociodemographic risk factors associated with mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [20, 21]. However, since we want to avoid low response rate, we restricted the collection of sociodemographic data to the one that were easily and commonly gathered. DASS-21 is a self-report instrument for evaluating adverse mental health symptoms, which consists of 21 items that assess 3 components, namely symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. There are 7 questions for each component, and each question is scored on a 4-point Likert-scale, ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all / never) to 3 (applied to me very much / almost always). The final score of each component is calculated by multiplying it by a factor of 2. The minimum final score is 0, and the maximum score is 42 for each component. Based on the total score of each component, the responses are categorized as normal, mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe [36]. The categorization of each component, including the score range, is presented in Table 1. The Indonesian version of DASS-21 had been validated previously and showed good convergence, discriminant validity, and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.895) [37].

Table 1. Categorization and score range of DASS-21 [36].

| Normal | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Extremely severe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 0–9 | 10–12 | 13–20 | 21–27 | 28–42 |

| Anxiety | 0–6 | 7–9 | 10–14 | 15–19 | 20–42 |

| Stress | 0–10 | 11–18 | 19–26 | 27–34 | 35–42 |

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Data normality was evaluated using one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data, median [interquartile range (IQR)] for skewed data, and frequency (percentage) for nominal data. To identify the risk factors for depression, anxiety, and stress, two steps logistic regression analysis was used. First, univariate regression was used to identify each sociodemographic variable that was associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. Variables with p-value < 0.25 [38] were then subjected to multivariate regression using backward selection method. Variables with p-value < 0.05 from the multivariate regression analysis were considered as independent risk factors. During the logistic regression analysis, variables with missing data of more than 20% were excluded, and depression, anxiety, and stress variables were re-categorized as dichotomous (normal or not) variables with the cut-off scores as follows: 9 for depression, 6 for anxiety, and 10 for stress [36].

Results

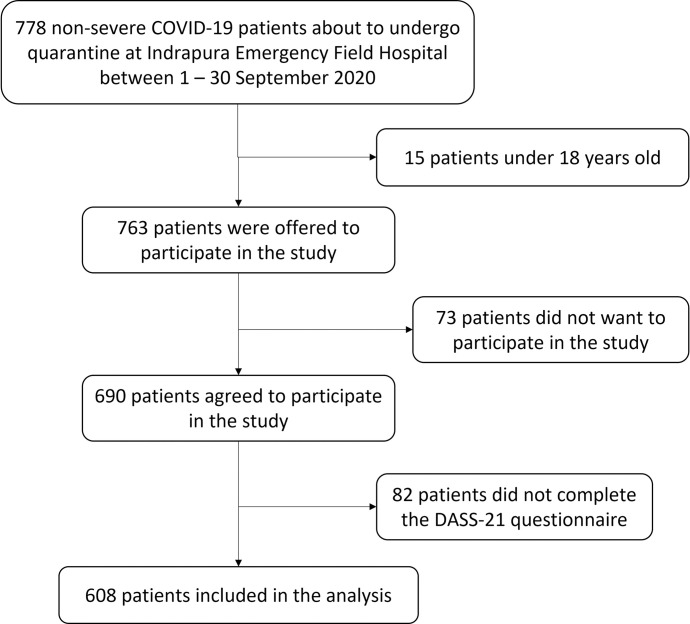

From 778 non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients who came to Indrapura Emergency Field Hospital during the study period, 763 participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria to be enrolled in the study. Of them, 608 patients were included in the analysis (79.7% response rate) (Fig 1). Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 2.

Fig 1. Flow diagram of study participants.

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristic of the study participants.

| Variables | N = 608 |

|---|---|

| Age in years, median [IQR] | 35 [27–45] |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 372 (61.2) |

| Female | 236 (38.8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 437 (71.9) |

| Single | 162 (26.6) |

| Divorced | 9 (1.5) |

| Have a child, n (%) | |

| Yes | 335 (55.1) |

| No | 273 (44.9) |

| Educational background, n (%) * | |

| Elementary graduate | 16 (3.8) |

| Junior high graduate | 23 (5.4) |

| Senior high graduate | 207 (48.7) |

| University graduate | 179 (42.1) |

| Job status as a healthcare worker, n (%) | 27 (4.4) |

| Family income per month, n (%) # | |

| < IDR 4.000.000 | 168 (41.2) |

| ≥ IDR 4.000.000 | 240 (58.8) |

| Had undergone self-quarantine recently, n (%) | |

| Yes | 271 (44.6) |

| No | 337 (55.4) |

*Missing data on 183 (30.1%) respondents.

#Missing data on 200 (32.9%) respondents.

Median [IQR] score for depression was 0 [0–2], 2 [0–4] for anxiety, and 2 [0–6] for stress. Total score was 4 [0–12]. Of all respondents, 22 (3.6%) reported symptoms of depression, 87 (14.3%) reported symptoms of anxiety, and 48 (7.9%) reported symptoms of stress. Data on the severity of each component is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Mental health severity symptoms distribution of the study participants.

| Depression | Anxiety | Stress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal, n (%) | 586 (96.4) | 521 (85.7) | 560 (92.1) |

| Mild, n (%) | 13 (2.1) | 25 (4.1) | 46 (7.6) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 8 (1.3) | 54 (8.9) | 2 (0.3) |

| Severe, n (%) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.2) | 0 (0) |

| Extremely severe, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

For regression analysis, all sociodemographic variables from Table 1 were included, except educational background and family income, as these variables had a high percentage of missing data. Results of univariate and multivariate regression analysis for depression are presented in Table 4. Respondents who worked as HCWs and those who had undergone self-quarantine recently were more likely to report symptoms of depression (Table 4). Table 5 lists the results of regression analysis for anxiety. Respondents who worked as HCWs were more likely to report symptoms of anxiety (Table 5). Univariate and multivariate regression for stress are presented in Table 6. Female respondents and those who had undergone self-quarantine were more likely to report symptoms of stress (Table 6).

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for depression.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | 95%CI | p-value | AOR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Female | 1.60 | 0.68–3.76 | 0.277 | |||

| Age in years | 1.01 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.720 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Single | 1.57 | 0.65–3.82 | 0.320 | |||

| Divorced | 0.0 | 0 | 0.999 | |||

| Have a child | ||||||

| No (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Yes | 0.98 | 0.42–2.30 | 0.977 | |||

| Job status | ||||||

| Healthcare workers | 7.54 | 2.55–22.30 | < 0.001 | 5.57 | 1.83–16.95 | 0.002 |

| Other than healthcare workers (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Had undergone self-quarantine recently | ||||||

| No (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 5.92 | 1.98–17.72 | 0.001 | 5.18 | 1.71–15.69 | 0.004 |

Variables with p-value < 0.25 in univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.05 in multivariate analysis were defined as independent risk factors. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 5. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for anxiety.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | 95%CI | p-value | AOR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Female | 1.57 | 1.00–2.48 | 0.052 | |||

| Age in years | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.550 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Single | 0.85 | 0.50–1.45 | 0.554 | |||

| Divorced | 0.72 | 0.09–5.82 | 0.754 | |||

| Have a child | ||||||

| No (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Yes | 1.40 | 0.88–2.23 | 0.159 | |||

| Job status | ||||||

| Healthcare workers | 3.22 | 1.40–7.43 | 0.006 | 2.92 | 1.24–6.88 | 0.014 |

| Other than healthcare workers (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Had undergone self-quarantine recently | ||||||

| No (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Yes | 1.56 | 0.99–2.46 | 0.057 | |||

Variables with p-value < 0.25 in univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.05 in multivariate analysis were defined as independent risk factors. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 6. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis for stress.

| Variables | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COR | 95%CI | p-value | AOR | 95%CI | P-value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Female | 2.16 | 1.19–3.92 | 0.011 | 1.98 | 1.08–3.64 | 0.028 |

| Age in years | 1.00 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.882 | |||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Single | 0.92 | 0.47–1.82 | 0.808 | |||

| Divorced | 1.44 | 0.18–11.81 | 0.737 | |||

| Have a child | ||||||

| No (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Yes | 1.39 | 0.76–2.56 | 0.284 | |||

| Job status | ||||||

| Healthcare workers | 3.67 | 1.40–9.58 | 0.008 | |||

| Other than healthcare workers (ref) | - | - | - | |||

| Had undergone self-quarantine recently | ||||||

| No (ref) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 2.01 | 1.10–3.66 | 0.023 | 1.86 | 1.01–3.44 | 0.047 |

Variables with p-value < 0.25 in univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.05 in multivariate analysis were defined as independent risk factors. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; COR, crude odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

Our analysis indicates that, in the later period of the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 3.6%, 14.3%, and 7.9%, respectively, among non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients in the East Java province, Indonesia. Further, we were able to identify job status as HCWs and recent self-quarantine history to be the risk factors for depression, while that for anxiety was job status as HCWs, and those for stress were female gender and recent self-quarantine history.

To the best of our knowledge, there are only 4 studies that evaluate the mental health of non-hospitalized asymptomatic and/or mild COVID-19 patients to this date [33, 39–41]. Guo et al (2020) evaluated the mental health symptoms of mild COVID-19 patients in China and revealed that the prevalence of depression and anxiety were 17.5% and 6.8%, respectively. Additionally, compared to matched normal individuals, total score for depression and anxiety were significantly higher in mild COVID-19 patients [39]. In Korea, the prevalence of depression and anxiety among asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients were 10.3–24.3% and 14.9–15.9%, respectively [33, 40]. A study among asymptomatic COVID-19 patients from India showed that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress were 49.4%, 40.9%, and 75.8%, respectively [41].

There are several possible explanations for such differences in terms of prevalence rates between this current study and previous studies. First, while our study was done in September 2020, previous studies were done during the initial stage of the pandemic. A recent meta-analysis of a longitudinal cohort studies showed that the prevalence of adverse mental health symptoms was the highest during March–April 2020 and decreased significantly afterward [18]. It is because perceived risks on COVID-19 infection and mortality, financial stability, and lifestyle changes rose sharply in the initial stages of the pandemic and declined in the later stages, and these factors were positively associated with changes in mental health symptoms [42]. Second, as the condition of healthcare systems and the government’s response to the pandemic differ across countries, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress are likely to be lower in countries where both are adequate [43, 44]. Third, the instrument used to measure mental health status in this study is different from those used previously [33, 39, 40], which would have also contributed to the observed variation. For example, compared to DASS-21, 8-item Patient Health Questionnaire instrument is more likely to classify individuals as having depression, while 7-item General Anxiety Disorder instrument is more likely to classify individuals as having anxiety [45]. However, the best instrument to measure depression, anxiety, and stress remains contentious, and we used the DASS-21 because it can measure depression, anxiety, and stress with the least number of questions and has already been adapted to Bahasa Indonesia.

Several studies have evaluated the prevalence of mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia using DASS-21. However, all of the studies focused on either general population [46–48] or healthcare workers [49–53], with none on the asymptomatic and/or mild COVID-19 patients. Depending on the study population and data collection period, the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 8.5–32.6%, 9.3–44.9%, and 2.4–31.8%, respectively [46–53]. Other than study period differences that has been discussed in the paragraph above and the difference in study population, varying prevalence rates may also be explained by differences in data collection methods used. While previous studies collected the data using online survey [46–52], we directly approached potential respondents and asked them to fill in the questionnaire. When collecting data for mental health studies, it has been reported that respondents provide a more negative response in online surveys than in offline surveys [54]. We hypothesized that this may be due to the anonymity associated with online questionnaires, because the respondents believe that their true identity can be fully protected in online but not in offline surveys. The identity issue might also be associated with societal stigma and discrimination toward people with mental health problems, especially in Asian countries, including Indonesia [55–57].

We found that people who worked as HCWs were more likely to report symptoms of depression and anxiety compared to non-HCWs, a finding not consistent with previous reports. For example, a study from China showed that the general population was at greater risk of developing depression and anxiety compared to HCWs [58], and another study from Italy reported that the general population and frontline HCWs were at similar risk of developing depression and anxiety [59]. We posit that disparities in healthcare systems across countries during a pandemic lead to differential impact on the mental health among HCWs [60], and that they are responsible for the observed differences in results.

The capacity of Indonesia’s healthcare system and infrastructure is far from adequate to battle the COVID-19 pandemic. Since before the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant shortage of HCWs and their distribution is uneven throughout the country [61]. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the shortage of HCWs is aggravated by high mortality among those treating COVID-19 patients [62, 63], resulting in higher workload and longer working hours for the remaining personnel, especially when the number of COVID-19 patients continue to increase. Moreover, similar to other countries, there is a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) for HCWs on duty in Indonesia, with this shortage being worsened by the panic buying and stockpiling of medical-grade PPE by the public [63, 64]. Other than that, the number of hospitals, bed capacities, and supporting facilities to treat COVID-19 patients such as negative pressure wards and ICU rooms are lacking and also not evenly distributed in Indonesia [61–63]. The lack of facilities putting HCWs in difficult position, where they have to decide to whom the treatments should be given [65]. The above-mentioned issues might explain why HCWs in Indonesia are more prone to adverse mental health symptoms compared to the general population.

In our study, we discovered that women were more likely to report symptoms of stress, and previous studies, either before [66–69] or during the COVID-19 pandemic [48, 70–72], also showed that women register higher stress scores and are at greater risk of developing stress. Gender differences in mental health have been discussed since the 1970s, and women have been reported to experience distress more frequently and develop more symptoms than men under identical levels of stress [73]. Several explanations have been proposed for greater stress susceptibility in women. Biologically, women express higher levels of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and had more CRF receptors compared to men, and upon its release from the hypothalamus during a stressful event, CRF activates the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis by stimulating adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) to produce cortisol, which is a primary stress hormone in the body, from the adrenal cortex [74]. Additionally, at identical levels of ACTH, the female adrenal cortex is more responsive to cortisol production than the male adrenal cortex [75]. Furthermore, fluctuations in sex hormones, either due to menstrual cycle or reproductive status, also contribute to stress vulnerability [76]. Psychologically, women tend to express distress by internalizing problems rather than externalizing them [77]. Apart from that, as women are the primary caregivers within the household, and they often prioritize the condition of family members over their own [78, 79]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it can be assumed that they may be apprehensive of no one being able to take care of the family if they are diagnosed with COVID-19 and had to be quarantined or hospitalized.

Interestingly, although mental health problems appear to be more common in women, suicide rates have been noted to be higher in men [80–82]. It can then be argued that mental health problems are underdiagnosed in men. Several possible explanations have been proposed, and they include: 1) men are less likely to express troubles, discuss sensitive issues, or solve emotional problems [83]; 2) men are more likely to express the distress by externalizing problems rather than internalizing them because of the fear of stigma [77]; and 3) men seek help for mental health care far less often than women as help-seeking behavior is viewed as a weakness and is contrary to masculine traits [84, 85]. In addition to that, it has also been suggested that there is a measurement bias in the currently available self-report instrument for mental health [83]. For instance, the experience of stress is different between sexes, where men feel more depersonalized, while women tend to feel emotionally exhausted [86]. Nevertheless, available instruments to measure stress do not assess psychological stress as depersonalization [68]. Thus, although the current study and a great body of evidence support the notion that women are at higher risk of developing mental health symptoms, we believe that investigations using structured diagnostic interviews should be done in the future to clarify whether one gender is at higher risk of developing mental health symptoms than the other.

In this study, we also found that people who had undergone self-quarantine recently were more likely to report symptoms of depression and stress. Since the 14th century, quarantine has been an important public health measure to reduce incidence and mortality during any outbreak [87, 88]. However, quarantine negatively affects mental health, and data from previous outbreaks have described several adverse psychological effects such as depression, anxiety, stress, low mood, and anger [89]. A recently published meta-analysis revealed a significant relationship between mass quarantine and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [90], and a multi-center study from 7 middle-income countries in Asia showed that those who have ever been quarantined during the COVID-19 pandemic were at higher risk of depression, anxiety, and stress [11]. Studies from China also demonstrate that people who were quarantined had higher risk of depression, anxiety, and stress. Furthermore, those who were diagnosed or suspected of having COVID-19 infection were at even greater risk of depression, anxiety, and stress compared to uninfected individuals [21, 91].

Nevertheless, the negative effects of quarantine on mental health appears to occur only during self-quarantine and not in facilitated quarantine. In the initial stage of the pandemic, Jeong et al (2020) evaluated the mental health of asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic COVID-19 patients who were admitted to the non-hospital facilities for isolation and monitoring in South Korea. Mental health status was evaluated twice in that study, i.e., after the 2nd week of quarantine and 1 week after the first survey, and they found no significant differences in anxiety or depression scores [33]. A similar study from South Korea also found that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, suicidal risk, and stress was constant until the 4th week of quarantine [40]. We have also previously reported that being quarantined in a quarantine facility did not worsen the mental health status of asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients [92]. Some of the known psychological stressors during quarantine are frustration, boredom, and inadequate supplies [89], but in a quarantine facility, patients are provided free meals thrice daily, including snacks and entertainment facilities. In contrast, people who undergo self-quarantine are not provided such things by the government, and this might explain these differences in terms of mental health status.

This study has several important limitations. First, the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress were based on self-reported questionnaire; hence, they may not always concur with objective assessment by health professionals. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this study precludes any inference of causality or evaluation of longitudinal changes in mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, socioeconomic status and educational background were not included in the regression model due to the missing data in more than 30% of the respondents. Fourth, it has been shown that longer quarantine time was associated with worsen mental health status [90, 93]. However, data regarding the number of days in self-quarantine were not available for a majority of the respondents because they could not adequately recall relevant details. Fifth, we did not evaluate the mental health prevalence from other groups, e.g., general population, hospitalized COVID-19 patients, and long COVID-19 patients. Thus, difference in mental health symptoms prevalence between non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients and other groups could not be seen. Last, data collection for this study was done in September 2020. The situation in that period was different than when Indonesia became the epicentrum of the COVID-19 pandemic in Asia [94], or in the recent outbreak of the Omicron variant [95].

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the mental health symptoms among non-hospitalized asymptomatic and mild COVID-19 patients during the later period of the COVID-19 pandemic. We report that the prevalence of mental health symptoms, especially depression, is relatively low among these patients in East Java province, Indonesia. Despite the low prevalence, our finding showed that HCWs are more vulnerable to depression and anxiety; females are more vulnerable to stress; and those who had undergone self-quarantine recently are more vulnerable to depression and stress.

Supporting information

(SAV)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19) 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen.

- 2.World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19–5 April 2022 [updated 5 April 2022]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19—5-april-2022.

- 3.Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: Origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J Adv Res. 2020;24:91–8. Epub 2020/04/08. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7113610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganesan B, Al-Jumaily A, Fong KNK, Prasad P, Meena SK, Tong RK. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak Quarantine, Isolation, and Lockdown Policies on Mental Health and Suicide. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:565190. Epub 2021/05/04. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.565190 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8085354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marazziti D, Stahl SM. The relevance of COVID-19 pandemic to psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):261. Epub 2020/05/13. doi: 10.1002/wps.20764 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7215065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covid- Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–12. Epub 2021/10/12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8500697 Flaxman holds stock in Agathos, and consults and advises Janssen, SwissRe, Sanofi, and Merck for Mothers on simulation modeling, outside of the submitted work. S Nomura reports support from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. All other authors declare no competing interests. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Presti G, McHugh L, Gloster A, Karekla M, Hayes SC. The Dynamics of Fear at the Time of Covid-19: A Contextual Behavioral Science Perspective. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020;17(2):65–71. Epub 2020/04/01. doi: 10.36131/CN20200206 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8629087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran BX, Ha GH, Nguyen LH, Vu GT, Hoang MT, Le HT, et al. Studies of Novel Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) Pandemic: A Global Analysis of Literature. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(11). Epub 2020/06/12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17114095 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7312200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Sousa GM, Tavares VDO, de Meiroz Grilo MLP, Coelho MLG, de Lima-Araujo GL, Schuch FB, et al. Mental Health in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Meta-Review of Prevalence Meta-Analyses. Front Psychol. 2021;12:703838. Epub 2021/10/09. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703838 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8490780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. 2017. Report No.: Contract No.: WHO/MSD/MER/2017.2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Tee M, Roy AE, Fardin MA, Srichokchatchawan W, Habib HA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental health of Asians: A study of seven middle-income countries in Asia. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246824. Epub 2021/02/12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246824 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7877638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V. Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113382. Epub 2020/08/24. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7417292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasu M, Muto K, Yamamoto I. Impacts of anxiety and socioeconomic factors on mental health in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population in Japan: A web-based survey. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0247705. Epub 2021/03/18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247705 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7968643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dragioti E, Li H, Tsitsas G, Lee KH, Choi J, Kim J, et al. A large-scale meta-analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID-19 early pandemic. J Med Virol. 2021. Epub 2021/12/28. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang SX, Chen J. Scientific evidence on mental health in key regions under the COVID-19 pandemic—meta-analytical evidence from Africa, Asia, China, Eastern Europe, Latin America, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Spain. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):2001192. Epub 2021/12/14. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2021.2001192 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8654399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu X, Zhu M, Zhang R, Zhang J, Zhang C, Liu P, et al. Public mental health problems during COVID-19 pandemic: a large-scale meta-analysis of the evidence. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):384. Epub 2021/07/11. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01501-9 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8266633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cenat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK, Noorishad PG, Mukunzi JN, McIntee SE, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113599. Epub 2020/12/08. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7689353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson E, Sutin AR, Daly M, Jones A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:567–76. Epub 2021/10/04. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8578001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahmud S, Mohsin M, Dewan MN, Muyeed A. The Global Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, Stress, and Insomnia Among General Population During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Trends in Psychology. 2022. doi: 10.1007/s43076-021-00116-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonzalez-Sanguino C, Ausin B, Castellanos MA, Saiz J, Lopez-Gomez A, Ugidos C, et al. Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2020;87:172–6. Epub 2020/05/15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7219372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shi L, Lu ZA, Que JY, Huang XL, Liu L, Ran MS, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors Associated With Mental Health Symptoms Among the General Population in China During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2014053. Epub 2020/07/02. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7330717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ngasa SN, Tchouda LAS, Abanda C, Ngasa NC, Sanji EW, Dingana TN, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with anxiety and depression amongst hospitalised COVID-19 patients in Laquintinie Hospital Douala, Cameroon. PLoS One. 2021;16(12):e0260819. Epub 2021/12/03. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260819 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8638855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahan E, Unal SM, Kirpinar I. Can we predict who will be more anxious and depressed in the COVID-19 ward? J Psychosom Res. 2021;140:110302. Epub 2020/12/03. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110302 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7683951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xie Y, Xu E, Al-Aly Z. Risks of mental health outcomes in people with covid-19: cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068993. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magnúsdóttir I, Lovik A, Unnarsdóttir AB, McCartney D, Ask H, Kõiv K, et al. Acute COVID-19 severity and mental health morbidity trajectories in patient populations of six nations: an observational study. The Lancet Public Health. 2022. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00042-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, Van Laethem Y, Cabaraux P, Mat Q, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1420 European patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Intern Med. 2020;288(3):335–44. Epub 2020/05/01. doi: 10.1111/joim.13089 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7267446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma YF, Li W, Deng HB, Wang L, Wang Y, Wang PH, et al. Prevalence of depression and its association with quality of life in clinically stable patients with COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:145–8. Epub 2020/07/14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.033 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7329672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veazie S, Lafavor B, Vela K, Young S, Sayer NA, Carlson KF, et al. Mental health outcomes of adults hospitalized for COVID-19: A systematic review. J Affect Disord Rep. 2022;8:100312. Epub 2022/02/16. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100312 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8828444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42. Epub 2020/02/25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Vaira LA, De Riu G, Cammaroto G, Chekkoury-Idrissi Y, et al. Epidemiological, otolaryngological, olfactory and gustatory outcomes according to the severity of COVID-19: a study of 2579 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(8):2851–9. Epub 2021/01/17. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06548-w ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7811338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shoaib N, Noureen N, Munir R, Shah FA, Ishtiaq N, Jamil N, et al. COVID-19 severity: Studying the clinical and demographic risk factors for adverse outcomes. PLoS One. 2021;16(8):e0255999. Epub 2021/08/12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255999 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8357125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett TD, Moffitt RA, Hajagos JG, Amor B, Anand A, Bissell MM, et al. Clinical Characterization and Prediction of Clinical Severity of SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among US Adults Using Data From the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2116901. Epub 2021/07/14. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16901 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8278272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeong SJ, Chung WS, Sohn Y, Hyun JH, Baek YJ, Cho Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and online mental health care of asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with coronavirus disease 2019. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0242130. Epub 2020/11/24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242130 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7682865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization Indonesia. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report—27 2020 [updated 30 September 2020]. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/indonesia/who-situation-report-27_f1cd3a6e-afe4-43ab-bd4f-d3f460b321de.pdf?sfvrsn=ce8d437a_4.

- 35.Indonesian COVID-19 operational Taskforce. Peta Sebaran 2020. Available from: https://covid19.go.id/peta-sebaran.

- 36.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2nd ed. Sydney Australia: Psychology Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.El-Matury HJ, Lestari FA, Besral. Depression, anxiety and stress among undergraduate students in jakarta: Examining scores of the depression anxiety and stress scale according to origin and residency. Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development. 2018;9(2):290–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. Epub 2008/12/18. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2633005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo Q, Zheng Y, Shi J, Wang J, Li G, Li C, et al. Immediate psychological distress in quarantined patients with COVID-19 and its association with peripheral inflammation: A mixed-method study. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2020;88:17–27. Epub 2020/05/18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.038 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7235603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang E, Lee SY, Kim MS, Jung H, Kim KH, Kim KN, et al. The Psychological Burden of COVID-19 Stigma: Evaluation of the Mental Health of Isolated Mild Condition COVID-19 Patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(3):e33. Epub 2021/01/20. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e33 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7813581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Upadhyay R, Sweta Singh B, Singh U. Psychological impact of quarantine period on asymptomatic individuals with COVID-19. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2020;2(1):100061. Epub 2020/01/01. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100061 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7474906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson E, Daly M. Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States: Longitudinal evidence from the Understanding America Study. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(2):570–87. Epub 2020/12/06. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12493 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paz C, Mascialino G, Adana-Diaz L, Rodriguez-Lorenzana A, Simbana-Rivera K, Gomez-Barreno L, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with confirmed and suspected COVID-19 in Ecuador. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2020. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13106 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7361296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maekelae MJ, Reggev N, Dutra N, Tamayo RM, Silva-Sobrinho RA, Klevjer K, et al. Perceived efficacy of COVID-19 restrictions, reactions and their impact on mental health during the early phase of the outbreak in six countries. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7(8):200644. Epub 2020/09/25. doi: 10.1098/rsos.200644 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7481706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters L, Peters A, Andreopoulos E, Pollock N, Pande RL, Mochari-Greenberger H. Comparison of DASS-21, PHQ-8, and GAD-7 in a virtual behavioral health care setting. Heliyon. 2021;7(3):e06473. Epub 2021/04/06. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06473 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8010403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harjana NPA, Januraga PP, Indrayathi PA, Gesesew HA, Ward PR. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Repatriated Indonesian Migrant Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9:630295. Epub 2021/05/25. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.630295 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8131639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.d’Arqom A, Sawitri B, Nasution Z, Lazuardi R. "Anti-COVID-19" Medications, Supplements, and Mental Health Status in Indonesian Mothers with School-Age Children. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:699–709. Epub 2021/07/22. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S316417 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8286101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elvira SD, Lamuri A, Lukman PR, Malik K, Shatri H, Abdullah M. Psychological distress among Greater Jakarta area residents during the COVID-19 pandemic and community containment. Heliyon. 2021;7(2):e06289. Epub 2021/02/23. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06289 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7879033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marthoenis Maskur, Fathiariani L, Nassimbwa J. Investigating the burden of mental distress among nurses at a provincial COVID-19 referral hospital in Indonesia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):76. Epub 2021/05/14. doi: 10.1186/s12912-021-00596-1 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8114658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lugito NPH, Kurniawan A, Lorens JO, Sieto NL. Mental health problems in Indonesian internship doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;6:100283. Epub 2021/12/14. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100283 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8642719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sitanggang FP, Wirawan GBS, Wirawan IMA, Lesmana CBJ, Januraga PP. Determinants of Mental Health and Practice Behaviors of General Practitioners During COVID-19 Pandemic in Bali, Indonesia: A Cross-sectional Study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:2055–64. Epub 2021/05/28. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S305373 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8141387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Margaretha SEP, Effendy C, Kusnanto H, Hasinuddin M. Determinants psychological distress of Indonesian Health Care Providers During COVID-19 Pandemic. Sys Rev Pharm. 2020;11(6):1052–9. doi: 10.31838/srp.2020.6.150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Syamlan AT, Salamah S, Alkaff FF, Prayudi YE, Kamil M, Irzaldy A, et al. Mental health and health-related quality of life among healthcare workers in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e057963. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang X, Kuchinke L, Woud ML, Velten J, Margraf J. Survey method matters: Online/offline questionnaires and face-to-face or telephone interviews differ. Computers in Human Behavior. 2017;71:172–80. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lauber C, Rossler W. Stigma towards people with mental illness in developing countries in Asia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):157–78. Epub 2007/04/28. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278903 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):777–80. Epub 2013/03/16. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3698814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hartini N, Fardana NA, Ariana AD, Wardana ND. Stigma toward people with mental health problems in Indonesia. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2018;11:535–41. Epub 2018/11/23. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S175251 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6217178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He Q, Fan B, Xie B, Liao Y, Han X, Chen Y, et al. Mental health conditions among the general population, healthcare workers and quarantined population during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychology, health & medicine. 2020:1–13. Epub 2020/12/31. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2020.1867320 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Mensi S, Di Marco A, Siracusano A, et al. Mental Health Outcomes Among Healthcare Workers and the General Population During the COVID-19 in Italy. Front Psychol. 2020;11:608986. Epub 2020/12/29. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.608986 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7753010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uphoff EP, Lombardo C, Johnston G, Weeks L, Rodgers M, Dawson S, et al. Mental health among healthcare workers and other vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic and other coronavirus outbreaks: A rapid systematic review. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0254821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mahendradhata Y, Andayani N, Hasri ET, Arifi MD, Siahaan RGM, Solikha DA, et al. The Capacity of the Indonesian Healthcare System to Respond to COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2021;9:649819. Epub 2021/07/27. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.649819 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8292619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wirawan GBS, Januraga PP. Correlation of Demographics, Healthcare Availability, and COVID-19 Outcome: Indonesian Ecological Study. Front Public Health. 2021;9:605290. Epub 2021/02/19. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.605290 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7882903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yunus F, Andarini S. Letter from Indonesia. Respirology. 2020;25(12):1328–9. Epub 2020/10/09. doi: 10.1111/resp.13953 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lauren C, Iskandar A, Argie D, Malelak EB, Sebayang SES, Mawardy R, et al. Strategy within limitations during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia: Shortage of PPE, prevention, and neurosurgery practice. 2020. 2020;9(3):3. Epub 2020-09-26. doi: 10.15562/bmj.v9i3.1825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, Thome B, Parker M, Glickman A, et al. Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049–55. Epub 2020/03/24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nielsen L, Curtis T, Kristensen TS, Rod Nielsen N. What characterizes persons with high levels of perceived stress in Denmark? A national representative study. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(4):369–79. Epub 2008/06/10. doi: 10.1177/1403494807088456 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who’s Stressed? Distributions of Psychological Stress in the United States in Probability Samples from 1983, 2006, and 20091. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2012;42(6):1320–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00900.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klein EM, Brahler E, Dreier M, Reinecke L, Muller KW, Schmutzer G, et al. The German version of the Perceived Stress Scale—psychometric characteristics in a representative German community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:159. Epub 2016/05/25. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0875-9 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4877813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Costa C, Briguglio G, Mondello S, Teodoro M, Pollicino M, Canalella A, et al. Perceived Stress in a Gender Perspective: A Survey in a Population of Unemployed Subjects of Southern Italy. Front Public Health. 2021;9:640454. Epub 2021/04/20. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.640454 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8046934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gloster AT, Lamnisos D, Lubenko J, Presti G, Squatrito V, Constantinou M, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: An international study. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244809. Epub 2021/01/01. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244809 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7774914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Al Dhaheri AS, Bataineh MF, Mohamad MN, Ajab A, Al Marzouqi A, Jarrar AH, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and quality of life: Is there any effect? A cross-sectional study of the MENA region. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0249107. Epub 2021/03/26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249107 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7993788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gu Y, Zhu Y, Xu F, Xi J, Xu G. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among patients with COVID-19 treated in the Fangcang shelter hospital in China. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2021;13(2):e12443. Epub 2020/11/03. doi: 10.1111/appy.12443 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Sex differences and the epidemiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1977;34(1):98–111. Epub 1977/01/01. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1977.01770130100011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bangasser DA, Wiersielis KR. Sex differences in stress responses: a critical role for corticotropin-releasing factor. Hormones (Athens). 2018;17(1):5–13. Epub 2018/06/03. doi: 10.1007/s42000-018-0002-z . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Roelfsema F, van den Berg G, Frolich M, Veldhuis JD, van Eijk A, Buurman MM, et al. Sex-dependent alteration in cortisol response to endogenous adrenocorticotropin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77(1):234–40. Epub 1993/07/01. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.1.8392084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li SH, Graham BM. Why are women so vulnerable to anxiety, trauma-related and stress-related disorders? The potential role of sex hormones. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):73–82. Epub 2016/11/20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30358-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simon RW. Sociological Scholarship on Gender Differences in Emotion and Emotional Well-Being in the United States: A Snapshot of the Field. Emotion Review. 2014;6(3):196–201. doi: 10.1177/1754073914522865 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Langer A, Meleis A, Knaul FM, Atun R, Aran M, Arreola-Ornelas H, et al. Women and Health: the key for sustainable development. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1165–210. Epub 2015/06/09. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60497-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rahman MA, Islam SMS, Tungpunkom P, Sultana F, Alif SM, Banik B, et al. COVID-19: Factors associated with psychological distress, fear, and coping strategies among community members across 17 countries. Globalization and health. 2021;17(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00768-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Freeman A, Mergl R, Kohls E, Szekely A, Gusmao R, Arensman E, et al. A cross-national study on gender differences in suicide intent. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):234. Epub 2017/07/01. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1398-8 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5492308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ellison JM, Semlow AR, Jaeger EC, Griffth DM. COVID-19 and MENtal Health: Addressing Men’s Mental Health Needs in the Digital World. Am J Mens Health. 2021;15(4):15579883211030021. Epub 2021/07/08. doi: 10.1177/15579883211030021 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8267042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith DT, Mouzon DM, Elliott M. Reviewing the Assumptions About Men’s Mental Health: An Exploration of the Gender Binary. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(1):78–89. Epub 2016/02/13. doi: 10.1177/1557988316630953 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5734543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D. Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:297–301. Epub 2005/04/02. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.297 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):5–14. Epub 2003/04/05. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Purvanova RK, Muros JP. Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2010;77(2):168–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nussbaumer-Streit B, Mayr V, Dobrescu AI, Chapman A, Persad E, Klerings I, et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: a rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;9:CD013574. Epub 2021/05/08. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013574.pub2 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8133397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tognotti E. Lessons from the history of quarantine, from plague to influenza A. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(2):254–9. Epub 2013/01/25. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.120312 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3559034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20. Epub 2020/03/01. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7158942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jin Y, Sun T, Zheng P, An J. Mass quarantine and mental health during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:1335–46. Epub 2021/10/29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.067 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8674683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Y, Shi L, Que J, Lu Q, Liu L, Lu Z, et al. The impact of quarantine on mental health status among general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(9):4813–22. Epub 2021/01/24. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01019-y ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7821451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lusida MAP, Salamah S, Jonatan M, Syamlan AT, Bandem I, Rahmania AA, et al. The Impact of Facilitated Quarantine on Mental Health Status of Non-Severe COVID-19 Patients. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021:1–2. Epub 2021/11/26. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.344 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8692842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206–12. Epub 2004/08/25. doi: 10.3201/eid1007.030703 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3323345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dyer O. Covid-19: Indonesia becomes Asia’s new pandemic epicentre as delta variant spreads. BMJ. 2021;374:n1815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rahadiana R, Jiao C. Indonesia Virus Cases Reach 6-Month High as Omicron Spreads: Bloomberg; 2022 Feb 4 [cited 2022 February 6]. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-02-03/indonesia-virus-cases-reach-six-month-high-as-omicron-spreads.