Abstract

Two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials are ultrathin, layered materials with a high surface-to-volume ratio that can deliver various therapeutics including small-molecule drugs, peptides, and large proteins. Their high surface area allows for high therapeutic loading and sustained therapeutic release over time. Some 2D nanomaterials respond to external stimuli, providing control over triggered or on-demand therapeutic release. 2D nanomaterials explored for biomedical applications include carbon-based (graphene), nanoclays, black phosphorous, layered double hydroxides, metal organic frameworks, covalent organic framework, 2D metal carbides and nitrides, transition metal dichalcogenides, transition metal oxides, polymer nanosheets, and hexagonal boron nitride. Most of these nanomaterials are biocompatible and degrade into nontoxic products, which is advantageous for therapeutic delivery systems. In this article, we will evaluate these nanomaterials for therapeutic delivery. We will highlight some of their unique physical and chemical characteristics, discuss their biological stability, and investigate their ability to deliver various therapeutics. Recent developments in 2D nanomaterials as drug delivery systems will also be discussed.

Keywords: Engineered nanomaterials, Nanosheets, Layered nanomaterials, Nanocarriers, Drug delivery

Introduction

Many U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs exhibit poor water solubility which leads to low bioavailability and inefficient distribution [1]. Drug delivery systems are designed to enhance the solubility and chemical stability of drug molecules to maintain a therapeutic concentration at the target site [2]. Recent research has shown that two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials improve the delivery of hydrophobic drugs by increasing drug efficacy, reducing toxicity, and improving bioavailability [2–5]. Their anisotropic charge distribution, large surface area-to-volume ratio, and photodynamic and thermal properties make 2D nanomaterials potentially useful as targeted delivery carriers.

Two-dimensional nanomaterials have a flat structure with lateral dimensions on the nanoscale or microscale, and a thickness of a single to a few atomic layers [5,6]. This atomic thickness creates the highest specific surface area of any type of material, providing a large number of contact points and increasing the propensity for surface interactions with drugs for high loading and controlled release kinetics. These materials can also load drugs via π–π stacking [7,8], which efficiently stabilizes drug molecules and promotes stimuli-responsive release [9]. The variation in energy band gaps, as well as physical, electrical, and chemical properties can differ among each material and allows for tunability in the design of therapeutic delivery systems [10].

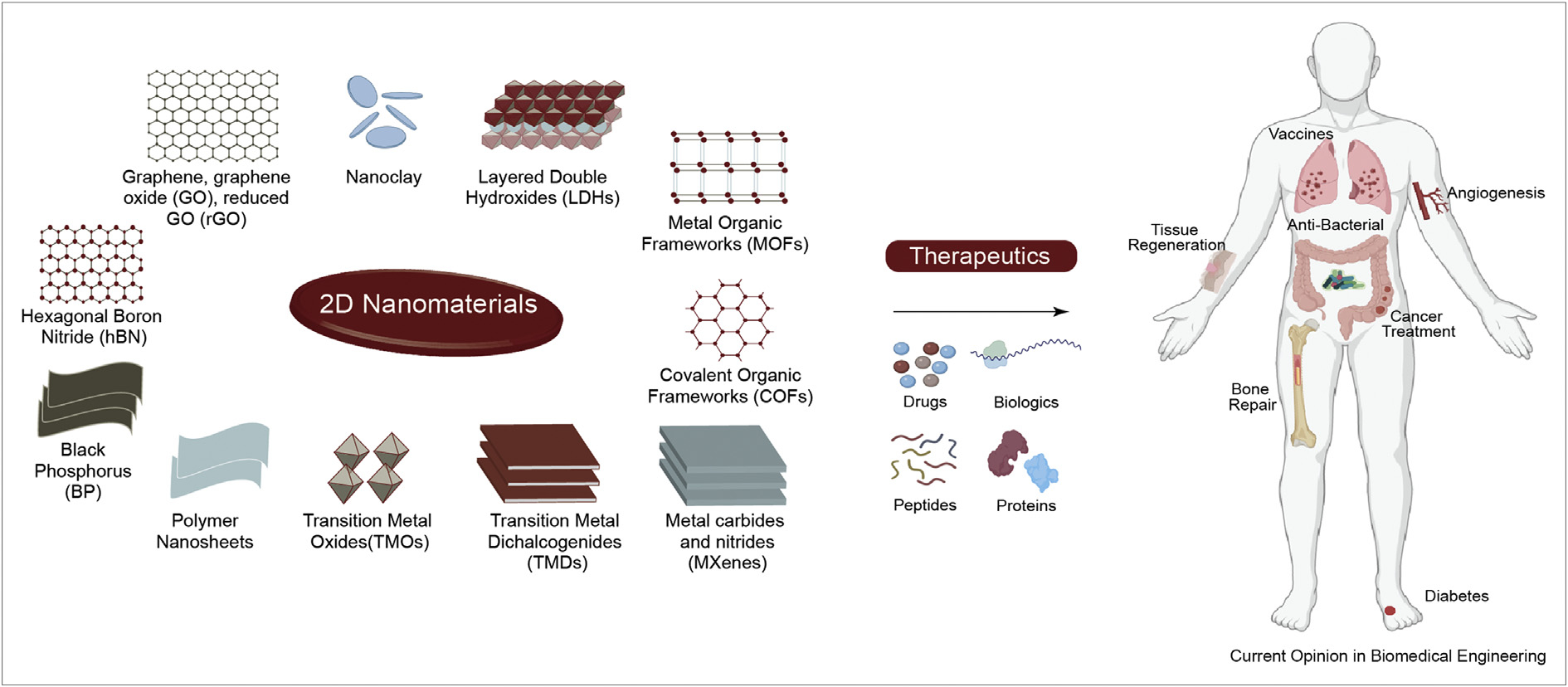

In this review, we will focus on 2D nanomaterials and their applications as drug delivery systems that exhibit localized, prolonged, and sustained release of therapeutics. The discussion is limited to the types of 2D nanomaterials most relevant to drug delivery based on biocompatibility, sustained and prolonged delivery ability, and stimuli-responsive ability. This includes carbon-based (graphene), nanoclays, black phosphorous, layered double hydroxides (LDHs), metal organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic framework (COFs), 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes), transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), transition metal oxides (TMOs), polymer nanosheets, and hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) (Figure 1). The scope of this paper is to highlight the current and emerging state of 2D nanomaterial-based drug delivery systems. We will highlight some of the most promising types of these 2D nanomaterials for therapeutics delivery applications, specifically for regenerative medicine, and cancer therapeutics.

Figure 1.

2D nanomaterials for drug delivery applications. The high surface area of these nanomaterials is used to sequester a range of therapeutics including drug, gene, peptide and proteins for various biomedical applications.

Carbon-based materials (Graphene)

Graphene is the oldest known 2D nanomaterial and has applications in numerous research areas including electronics, sensing, and energy [11–13]. The atomic structure contains layers with strong pi bonds between carbon atoms and weak interlayer binding through Van der Waals forces which lead to extreme mechanical strength [14]. Graphene also has exceptional physiochemical, thermal, and biomedical properties based on its highly reactive structure [15,16]. Graphene oxide (GO) is a modified graphene material with carboxylic acid, epoxide, and hydroxyl groups in the planar structure [14], as well as unmodified sections of hydrophobic graphene, making GO an amphiphilic molecule useful for stabilization of hydrophobic drugs in solution [17]. The amphiphilic nature of the molecule and presence of functional groups are beneficial for drug delivery applications [18]. Graphene oxide can be further modified to obtain reduced graphene oxide (rGO) which has increased electrical properties, but reduced surface charge and hydrophilicity compared to GO [14]. Reduced graphene oxide is a stimuli responsive material [19] and has improved dispersibility [20] compared to GO, both of which can be leveraged to synthesize stable drug carriers that perform a sustained release.

Graphene oxide nanosheets were used for targeted delivery of chemotherapeutic agents such as docetaxel [21]. Docetaxel has poor solubility in water, and current FDA-approved delivery methods utilize surfactants that could cause extreme adverse effects in some cases. GO was used to load docetaxel through π–π stacking for efficient delivery without the use of a surfactant. The 37% loading capacity with GO was increased by a factor of 3.7 relative to reported data for commonly used small-molecule drug delivery systems [21]. Drug release was pH-dependent, as there was a 2.73-fold increase in acidic pH relative to neutral pH over identical time periods. Transferrin was incorporated to promote accumulation of the GO nanosheets in cancer cells that contain an abundance of transferrin receptors. In vivo testing is necessary to determine how targeted delivery will be affected by normal cells that express high levels of transferrin receptors and cause delocalized delivery [21].

Intracellular delivery of therapeutics is especially beneficial because specific cell compartments can be targeted to achieve better therapeutic activity. A recent study investigated the enhancement of cellular uptake and drug release properties of GO via surface modification without limiting biodegradability [22]. Doxorubicin was loaded by intercalation onto G-4 quadruplex DNA strands which were used to line the GO surface. Actuated by NIR irradiation, the photothermal effect of GO would cause the DNA to denature and release the drug. This newly formed single strand binds to hemin on the GO surface and, because of high hydrogen peroxide in the tumor environment, catalyzes a reaction that degrades GO into biocompatible, rapidly cleared products. In vivo testing showed a significant level of tumor growth inhibition, attributed to both the inherent properties of GO and benefits of the surface modification [22]. Graphene-based materials have shown to exhibit high loading ability, biodegradability, tunability, and controlled drug release for small-molecule drugs [23]. Due to this, these materials have also been investigated for their ability to sequester and release larger biomolecules [24].

In another study, a GO-based hydrogel carrier for bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) was designed for the improvement of BMP2 therapeutic function in cartilage [25]. The initial burst release seen in hydrogels with free BMP2 was greatly hindered upon incorporation of GO, after which there was sustained release for 40 days. The controlled release behavior is especially beneficial in treating osteoarthritis, as improper doses of BMP-2 can cause side effects such as ectopic bone formation or osteolysis. In addition, there was an enhanced therapeutic effect and greater inhibition of osteoarthritis in the gels that included GO [25]. Graphene oxide can also be used to promote vaccine delivery of biomolecules [26]. Graphene oxide has been investigated as a potential nanocarrier for protein-based therapeutic agents to facilitate their interactions with dendritic cells. Graphene oxide strongly interacts with proteins that are more hydrophobic, and those with more lysine residues leads to strong covalent interactions. In vitro testing showed GO enhanced the vaccine antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells which elicit a more potent immune response than the CD4+ T cells that cause the antibody mediated response [27]. Because of the high surface area, sheet-like structure, and inherent hydrophilicity, GO can efficiently load and deliver proteins via multiple administration routes.

When used as therapeutic carriers, GO nanosheets have a tendency to agglomerate due to interlayer bonding which can reduce the efficiency of drug release [28]. To address this, rGO was synthesized via spray drying and used to form iron oxide–decorated rGO microspheres for synergistic cancer therapy. The microspheres showed a very high loading efficiency (92.15%) of doxorubicin which can be attributed to the high surface area of rGO, strong π–π stacking and hydrogen bonds [28]. Release rates of doxorubicin were analyzed in physiologic pH (7.4) as well as acidic pH (5.4) to simulate microsphere behavior in both healthy and tumor tissue. In the first 10 h, nearly twice as much therapeutic was released in pH = 5.4 compared to pH = 7.4. The cumulative release totals for the microgels followed a similar trend, showing a significantly higher release in acidic pH after 98 h. In addition to pH responsiveness, the photothermal properties of rGO allowed for NIR stimulus to influence microsphere behavior in two ways: accelerated doxorubicin release as well as an increased temperature both related to NIR intensity. In vitro cytotoxicity assays showed high biocompatibility and excellent antitumor properties [28]. Although it is unclear how results from the in vitro assessments would translate to in vivo microsphere performance, the available data show that rGO can be used to form stable, smart delivery systems for small-molecule drugs.

The stimuli-responsiveness of rGO can also be utilized to create drug carriers to deliver agents for treating chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, or arthritis that require frequent doses over extended periods of time. Hydrogels modified with rGO were used for on-demand release of insulin over 7 days while maintaining its metabolic activity [29]. Insulin-loading capacity increased with rGO concentration and the hydrogels showed a small burst release of only 10% when submerged in PBS for 1 day. This period was not followed by any further release which indicates the ability of the hydrogels to stabilize loaded cargo and only release when triggered. With daily NIR laser illumination for 1 week there was a repeated release of over 30% of the loaded insulin on each day. The metabolic activity of photothermally released insulin was analyzed by measuring protein kinase B phosphorylation (p-Akt), which occurs as a direct result of insulin binding to HepG2 cells. Specifically, the p-Akt/Akt ratio was measured for native insulin as well as insulin released due to NIR stimulus from the hydrogels. The photothermally released insulin showed a ratio of 6.14 compared to 4.82 by native insulin, indicating a greater activity in the hydrogel-released hormone [29]. The reason is unclear, but this is possibly due to the ability of the rGO to stabilize and increase the bioactivity of insulin. In vitro assays showed a high biocompatibility of the hydrogels as well as the ability to perform NIR-stimulated transdermal delivery of insulin through porcine ear skin [29]. The ability of the rGO-incorporated gels to load, stabilize, and release sustained levels of insulin on demand without signs of cytotoxicity is promising for diabetes treatment and can be expanded to design therapeutic carriers for other chronic diseases.

Nanoclays

Clay materials are naturally occurring, finely grained materials that contain phyllosilicate minerals [30]. Smectites are a type of phyllosilicate with a 2:1 unit structure of two tetrahedral sheets sandwiching one dioctahedral (montmorillonite (MMT)) or trioctahedral (Laponite or saponite) sheet formed from a metal cation. These types of clay minerals are biocompatible, have a large specific surface area, and have high swelling capabilities in the presence of water [31,32]. Laponite and MMT clays have extremely small particle size, large cation exchange capacity, anisotropic charge distribution, and interactions with inorganic and organic substances, imparting physiochemical properties that make them useful for drug delivery applications [33].

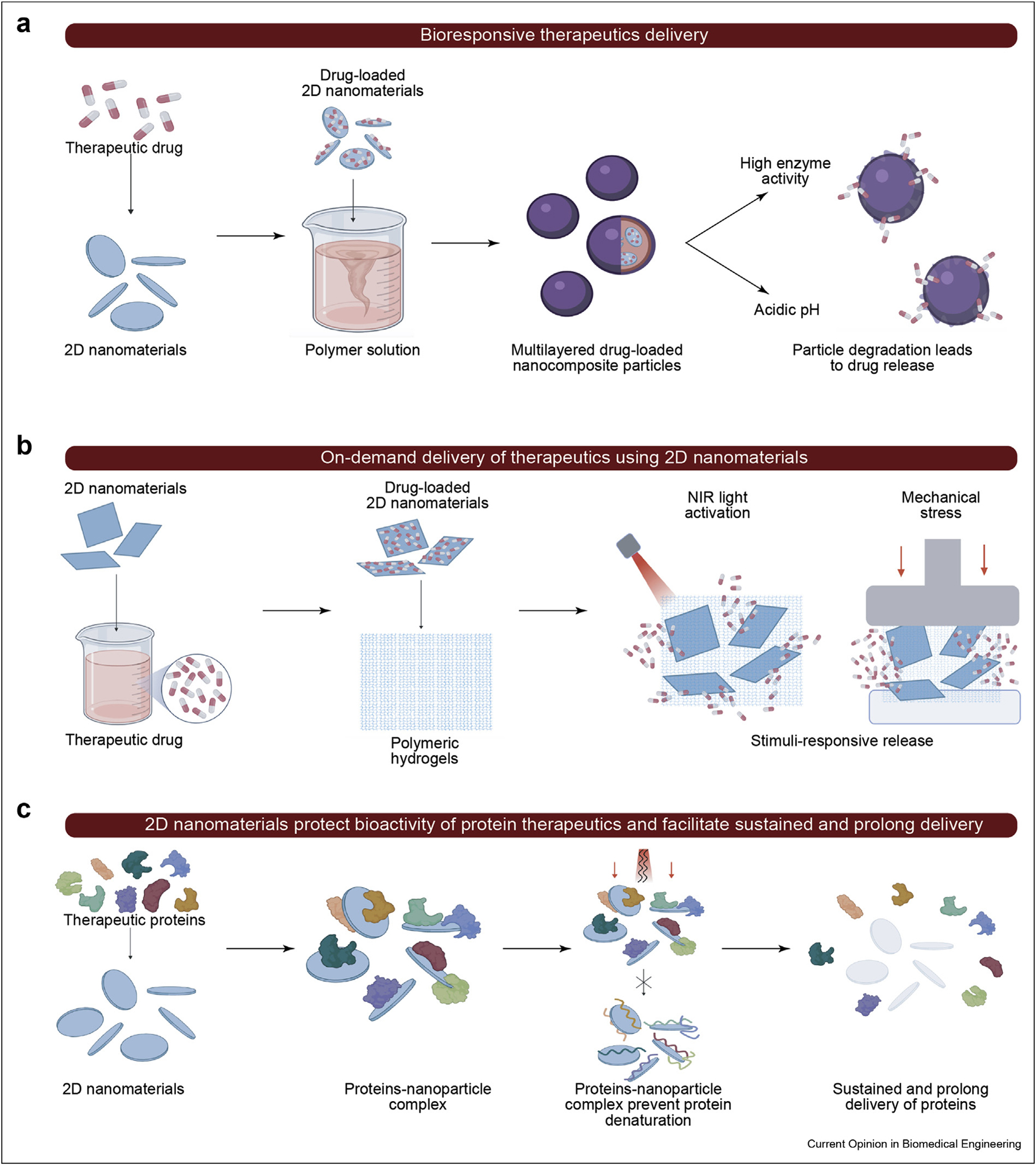

The structural and charge characteristics of nanosilicate clays have been utilized to efficiently load and release small molecules [34]. Cisplatin, 4-fluorouracil, and cyclophosphamide were each loaded into Laponite disk–based nanohydrogels to evaluate the loading and release of different chemotherapeutics for breast and ovarian cancer. Laponite disintegrates into ions at pH values lower than 7; therefore, the nanosilicate hydrogels were expected to be stable at physiologic pH and release their cargo near pH = 5.5. This would allow for the hydrogels to release the loaded cargo prior to intracellular degradation by lysosomal enzymes [35]. In an acidic environment (pH = 5.5), the hydrogels increased in size by a factor of 15 and burst into small pieces, releasing the loaded molecules. When compared to the free drug, each drug loaded separately in Laponite-based gels showed high cytotoxic activity in both HeLa cells and MCF-7 cells. Combined into one gel, the mixture showed a positive synergistic cytotoxicity effect with an IC50 value that is 10 times lower than the theoretical value. When injected intravenously into mice, the free Laponite gel showed high biocompatibility. The hydrogels were biodegradable and showed 100% clearance in 24 hours [35]. The use of multilayered systems is common for nanosilicate clays, as the flat structure allows for facile synthesis of versatile layer-by-layer materials with high loading capabilities and efficient surface functionalization [36,37] (Figure 2). MMT/hyaluronic acid (HA)–gentamicin layer-by-layer films were synthesized for on-demand self-defense drug release of antibiotics to prevent bacterial colonization after implantation. The nanofilms showed a high loading dosage of 0.85 mg/cm2, which was partly due to the high MMT adsorption to positively charged molecules. The films exhibited enzyme-responsive release, and in vivo testing showed good bactericidal properties due to the layer-by-layer enzymatic degradation [38]. The results of these experiments showed that smectite nanoclays can be used in drug delivery to increase performance and enhance biocompatibility of therapeutic carrier systems.

Figure 2.

Different synthesis methods for therapeutic controlled delivery systems. (a) Layer by layer polymer encapsulation of therapeutics sequester them until particle degradation. (b) Incorporation of bound therapeutic within hydrogel scaffold provides them with NIR and mechanical stimuli release. (c) Interactions between nanoparticles and proteins provide them with protection from mechanical and thermal stress and allow release following degradation.

Drugs often have rapid clearance and short half-lives; therefore, supraphysiological doses are required to achieve their intended therapeutic effect, despite often resulting in adverse effects [39,40]. Nanosilicates can remain in circulation for prolonged periods, promoting increased bioavailability of smaller amounts of loaded therapeutics [41,42]. The high surface area of nanoclays can be used to sequester a range of protein therapeutics for sustained and prolong delivery [43–46]. In a recent study, Laponite-based delivery systems were used to reduce the concentration of delivered recombinant human BMP2 (rhBMP2) and transcription growth factor beta-3 (TGF-β3) while maintaining bioactivity [47]. After an initial burst release of loosely bound protein, sustained release was observed for over 30 days. Laponite nanoclays showed inherent osteoinductive properties, and a synergistic effect on osteogenic differentiation was seen in the rhBMP2-loaded nanoclay. Delivery of TGF-β3 with nanosilicates provided a greater stimulation of specific hMSC differentiation than delivery of TGF-β3 alone, using 10-fold less TGF-β3 [47]. In another study, 2D Laponite particles were incorporated into injectable alginate hydrogel walls to tune protein release and prevent denaturation. Five proteins of varying size and net charge were bound to nanoparticle-walled hydrogels and analyzed against alginate-only gels. Laponite particles were able to eliminate the initial burst release and maintain a controlled release over 4 weeks without affecting bioactivity [48]. Further investigation should be conducted in vivo to determine the effects of cellular infiltration on the gels as well as how the osteogenic properties of Laponite may cause calcification of the hydrogel and disrupt its function.

Black phosphorus (BP)

Black phosphorus (BP), or phosphorene, is a semiconductor phosphorus allotrope with an orthorhombic pleated honeycomb structure [49]. Black phosphorus is structurally similar to graphene but has unique properties that offer advantages over the latter in some biomedical applications such as its tunable band gap and high carrier mobility [49,50]. The anisotropic behavior, high biocompatibility, and nontoxic degradation products make BP an ideal material for use in drug delivery systems [51]. Some of these unique characteristics of BP can be leveraged to develop bioresponsive and on-demand delivery carrier.

Negatively charged BP sheets exhibit strong binding to positively charged small-molecule drugs via electrostatic interactions [52]. These nanosheets have stimuli–responsive properties that can be leveraged for photothermal therapy treatment of cancers. A BP nanosheet–based drug delivery system was used to deliver a chemotherapeutic agent and reverse multidrug resistance seen in tumor cells [53]. Intracellular mutant p53 in cancer cells has anti-apoptotic capability and allows the cells to tolerate chemotherapeutics. Phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) can remove mutant p53, leading to elimination of drug resistance. Here, the BP nanosheets were loaded with PEITC and doxorubicin and investigated [53]. Polydopamine (PDA) and polyethylene glycol-amine were added to enhance binding to PEITC and enhance the solubility of the nanocarriers. Doxorubicin release was investigated, and it was determined that this system had both pH- and NIR-responsive capabilities. In acidic environments, PDA dissociates and the solubility of doxorubicin increases, leading to an accelerated release. NIR stimulus caused the BP nanosheet to generate heat, decreasing electrostatic interactions between the drug and carrier. In vivo assessment of the delivery system showed that the carriers have high biocompatibility and, when used in combination with NIR-stimulation, synergistic anticancer effect is observed [53].

Black phosphorus also has inherent antimicrobial properties [54] that are enhanced when used in combination with another antimicrobial agent [55]. In a recent study, titanium aminobenzenesulfanato (Ti-SA4) complexes were loaded onto BP nanosheets via simple mixing [56]. The loading efficiency and antibacterial effect of this platform against drug-resistant bacteria were investigated. Strong P–Ti coordination led to a high level of loading at about 43%. BP/Ti-SA4 has a positive surface potential, which is beneficial for binding to negatively charged bacteria, while its sharp edges penetrate and destroy the bacteria membrane. Significant improvement in therapeutic effect was seen in the hybrid nanocarrier relative to the free BP and Ti-SA4 [56]. It is known that BP has good biocompatibility and biodegradability, but to expand the applications of BP in small-molecule drug delivery, in vivo assessment is necessary to determine how surface modification can affect these properties.

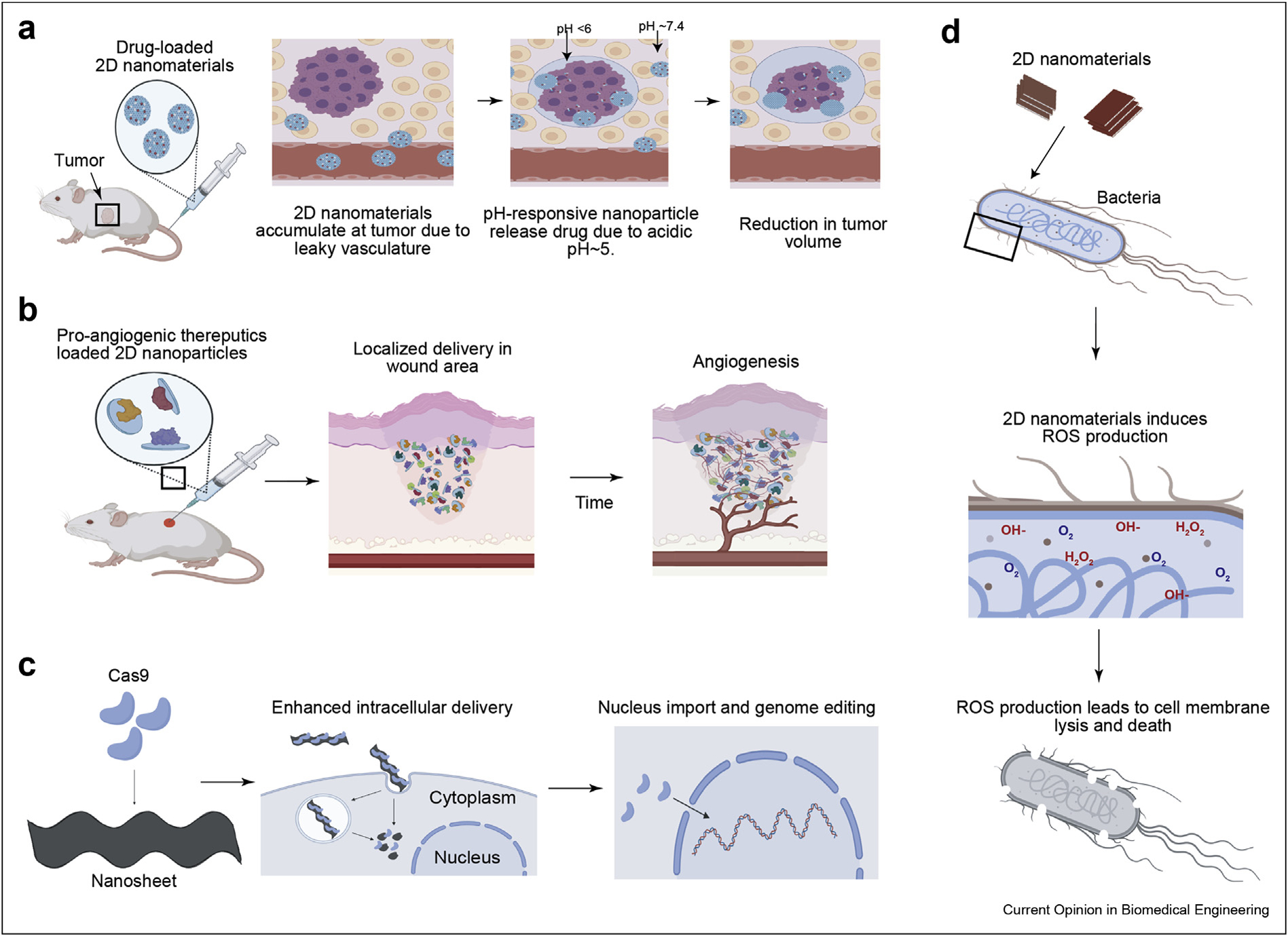

Many of the current DNA delivery methods are subject to increased risk of off-target toxic effects due to over-dosing [57]. To achieve direct and sustained delivery without excessive release of drugs, BP nanosheets were employed for cytosolic delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein [58]. Cas9 was loaded to BP nanosheets via electrostatic interactions at an efficiency of 98%. Upon cellular uptake via endocytosis, the BP/Cas9 complex performed endosomal escape, and cytoplasmic degradation of the BP led to sustained Cas9 release over 12h. In vivo testing showed promising results, demonstrating that the nanocarrier system showed significant gene silencing activity [58]. These results indicate that BP can support efficient loading and delivery via targeted cellular uptake.

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs)

Layered double hydroxide materials have a layered structure, similar to clays, with two metal hydroxide outer layers sandwiching the inner anionic layer. These materials are responsive to pH and will biodegrade in response to acidic pH, forming biocompatible byproducts. Their positive charge also allows for efficient loading of anionic molecules. These properties are promising for designing site-specific drug delivery systems [59,60].

While current chemotherapy drugs have been shown to prolong patient lifespan, there are issues of toxicity and extreme adverse effects. Layered double hydroxides have low toxicity and, due to their 2D structure, can deliver the required therapeutic dose of drug without causing adverse effects due to over-dosing [59]. Layered double hydroxides were investigated as a nanocarrier delivery system for etoposide (VP16), a common chemotherapy drug with side-effects such as hair loss, gastrointestinal problems, and leukopenia [61]. Use of the LDH-based system increased cellular uptake of the free drug from 61.6% in 1 hours to over 90% in that same timeframe and led to significant reduction in common VP16 side effects, including liver and blood toxicity. Release was also PH-dependent, with a high initial burst release of ~40% and ~25% at acidic pH of 4.8 and 5.8, respectively. The delivery system also greatly increased the bioavailability of the drug, reaching a peak plasma concentration at 24 hours compared to 4 hours for the free drug [61]. LDHs were also used to synthesize a nanofilm for delivery of butyrate, an antibacterial agent, focusing on LDH H2O2 responsiveness [62]. The films, when in a high H2O2 environment, were able to revert H2O2 to OH− which would exchange with the interlayer butyrate. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria were used to measure the antibacterial activity of the films in vivo. Layered double hydroxide samples without butyrate showed some antibacterial properties, with an inhibition rate of close to 100% for S. aureus but only about 70% for E. coli. Samples containing butyrate were able to kill both types of bacteria with inhibition rates of 100%. H2O2 controlled release was seen, with alternating burst release and sustained release depending on whether the film was submerged in H2O2 or PBS [62]. Layered double hydroxide–based drug delivery enhanced many aspects of the loading, targeting, and sustenance mechanisms of both VP16 and butyrate, indicating that these 2D nanomaterials would be effective delivery vehicles for small-molecule drugs.

To effectively deliver larger molecules such as proteins or peptides, the denaturation of immobilized proteins must be prevented to maintain biocompatibility and performance [63]. Properties of LDH such as the high surface-to-volume ratio, high hydrophilicity, and high biocompatibility are advantageous for protein carriers that will transport immobilized proteins without altering their activity [64]. Mg–Al–Cl-type LDH/aluminum hydroxide (Alhy) nanoplates were formed and tested for their ability to load and release bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a model protein [63]. The carrier showed an extremely high loading capacity of 996 mg/g. This is due to an increase in porosity and tunability of the surface area of LDH sheets with the addition of Alhy. Hydrogen phosphate stimulated protein release, due to the high affinity of LDH films for anionic molecules, causing 52% and 49% desorption for the LDH-Alhy and a commercial LDH, respectively. Chloride did not cause BSA release, showing 1.8% and 1.1% release for the two composites [63]. In vivo experiments are necessary to determine how different physiological pH would affect carrier performance, but the high loading capacity and selective protein release prove that LDH materials have potential for applications in protein delivery.

Metal organic frameworks (MOFs)

MOFs are organic–inorganic hybrid materials composed of metal ion nodes and organic linkers. The links form a cage-like, hollow structure with high porosity and an extremely high surface area beneficial for drug encapsulation and loading. Many combinations of metal and organic linkers can be used to form MOFs with specific properties and functions. Their versatile structure along with their biocompatibility and degradability make MOFs useful within various biomedical fields [65–67].

Curcumin (CCM) is a naturally occurring molecule with many health benefits including anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and anti-HIV properties [68]. The therapeutic benefits of CCM, similar to other small-molecule drugs, are hindered by poor drug solubility and instability [69]. Zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF) MOFs were used to design an effective delivery system for CCM. Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks are a type of MOF with high biocompatibility, large pores, and biostability, which promote their use as drug carriers [70]. ZIF-8 showed a high encapsulation efficiency of 83.3%, and the carriers exhibited pH-responsive release with a cumulative release of 88% and high burst release at acidic pH, with only 28% cumulative release and very minor burst release at physiological pH. In vitro assessment of the ZIF-8–encapsulated drug effect on HeLa cells showed that MOF enhanced the cytotoxic effect of CCM [70].

In another study, [Zn4O(3,5-dimethyl-4-carbox ypyrazolato)3] (Zn4O(dmcapz)3) MOF was used to encapsulate hydrophobic drugs (aminobenzoic acid and benzocaine), a hydrophilic drug (5-fluorouracil), and an amphiphilic drug (caffeine) [71]. The effects of the MOF on the loading, delivery, and stability of each drug were analyzed. Over 60% encapsulation efficiency was seen in the hydrophobic and amphiphilic drugs, but there was only 22% encapsulation efficiency for 5-fluorouracil. There was also very little attenuation of the burst release for the hydrophilic and amphiphilic drug, while a sustained release was shown for the more hydrophobic drugs. The enhanced performance of hydrophobic drugs when encapsulated in MOF is presumably due to the hydrophobic nature of Zn4O(dmcapz)3 [71]. The results of these experiments prove that MOF materials are capable of forming effective drug delivery systems for hydrophobic drugs due to their high loading capacity, stimuli-responsive release, and tunable structural properties that promote strong hydrophobic interactions.

Similar to LDH materials, MOFs have the ability to stabilize enzymes, viruses, and antibodies while maintaining their physical and chemical properties [72]. ZIF-8 growth on protein surfaces has proved to be a simple, efficient method of stabilization that is possible for many different molecules [73]. Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) was investigated as a model protein and encapsulated in ZIF-8 to test the MOF ability to stabilize and enhance the functionality of protein-based vaccines. Results showed that shell formation, stress, and exfoliation did not significantly alter the protein surface. In vivo assessments of the release, host response, and histocompatibility were performed. With multiple subcutaneous injections of the TMV-ZIF-8 carrier and no observed instances of toxicity or tissue damage, it is apparent that the MOF carrier can stabilize the protein without altering its biocompatibility. The delivery system was also able to promote sustained TMV delivery over 14 days, while the free TMV almost fully expended within ~8–9 days [74]. The versatility, biostability, and loading capabilities of MOFs indicate that they could be advantageous in vaccine delivery.

Covalent organic frameworks (COFs)

Covalent organic frameworks are crystalline porous organic polymers with a layered sheet-like structure. Contrast to the irreversible bonds seen in conventional covalent organic polymers, COFs are formed via reversible condensation reactions, providing better crystallinity and biodegradability. Similar to MOFs, there is versatility in the organic compound used to form the material, allowing for diverse properties. Their tunable porosity and pore function as well as the lightweight atomic composition makes COFs slightly advantageous over MOFs due to reduced potential hazard [75]. Although the large surface area, porosity, and high tunability of COF materials are beneficial properties for drug delivery applications, these materials have intrinsically poor targeting, low permeability, and physiological instability [76].

Polymers are commonly integrated with porous materials to form composites with desired properties. Nanocomposites composed of polyethylene-glycol-modified curcumin derivatives and amine-functionalized COFs (PEG-CCM@APTES-COF-1) were developed for In vitro and in vivo assessments of their loading characteristics, drug retention, stability, and release [76]. Amine-functionalized COF by itself is hydrophobic which leads to inefficient loading of hydrophobic doxorubicin. The PEG-CCM@APTES-COF-1 nanocomposites, on the other hand, showed a remarkably high loading capability of 9.71 wt% and high encapsulation efficiency of 90.5%. The carrier system considerably inhibited HeLa cell growth with low doxorubicin concentrations compared to controls that had no significant effect on cell growth. Injection of doxorubicin-loaded nanocarriers showed increased antitumor efficiency via combinational therapy of targeted cellular uptake due to PEG-CCM encapsulation as well as doxorubicin release (Figure 3). The delivery system also demonstrated prolonged blood circulation in mice [76].

Figure 3.

Application of 2D nanomaterials. (a) In vivo testing of doxorubicin-loaded COFs demonstrating pH-responsive therapeutic release. (b) In vivo testing of protein-loaded nanoclays demonstrating localized angiogenesis over time. (c) Cas9 proteins bound to nanosheets enable genome editing following cellular import of the 2D nanomaterials. (d) Antibacterial effects of 2D TMDs result in ROS production within bacteria causing cell lysis.

In another study, a COF-based delivery system was designed by sandwiching an imine-derived COF drug reservoir between biocompatible, porous PCL films [77]. The release of methylene blue (MB), a model drug, as well as oxytocin was analyzed. The ordered structure and smooth pores of the COF allowed for controlled release and hindrance of an initial burst for both molecules. High biocompatibility was achieved in the COF membrane with cell viability higher than 80% [77]. The wide range of materials available to form COFs allows for tunable porosity, which is advantageous for the design of drug delivery carriers with high drug loading. As some of the building block materials of COFs may have inherent toxicity, polymers can be used as modification tools to improve the safety and efficiency of COF-based drug carriers.

Boroxine-linked COFs are able to bind with insulin or proteins via coordination bonds between the electron-deficient boron atom and imidazole or amine groups [78]. As previously stated, he ability to stabilize proteins and inhibit denaturation during transport is essential for therapeutic delivery. Dual-responsive nanocarriers based on boroxine-linked COFs were designed to load and deliver insulin in response to glucose and pH [79]. PEG was used as a hydrophilic component, forming a micelle that traps the insulin inside the carrier until the intended stimuli is received. The incorporation of glucose oxidase endowed glucose–responsive properties, while the COF decomposed in acidic conditions. Insulin release was triggered by either an increase in glucose concentration or a decrease in pH, and there was no conformational change of released insulin in either case. In vitro, the insulin-loaded micelles performed cytosolic delivery to A549 cells and were able to degrade into biocompatible products [79]. The efficiency of the carriers in their response to stimuli and their ability to regulate glucose levels are both promising discoveries for the use of COFs in protein-based delivery systems.

Metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes)

MXenes include transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides. Mn+1Xn is the generic formula, the main three being M2X, M3X2, and M4X3, where M represents an early transition metal and X represents carbon or nitrogen. The tunable structure of these materials allows for flexibility in design and functionality. In addition to the high drug loading benefits, MXenes have unique characteristics such as enzymatic degradation and efficient cellular uptake making MXene-based drug delivery systems promising [80].

Two-dimensional MXenes have unique properties enabling their applications in photothermal cancer treatment [81,82]. Specifically, MXenes are triggered via NIR exposure, absorbing the emitted light and increasing in temperature, causing hyperthermia within the tumor microenvironment. Some limitations of these materials include physiological instability and inability to control drug release [83]. A possible solution is the incorporation of hydrogels, as these materials are highly biocompatible and commonly used in drug delivery. The known lack of mechanical strength in hydrogels would be restored with incorporation of 2D MXenes. In a recent study, Ti3C2 MXenes were integrated into cellulose hydrogels to potentially achieve controlled release and biocompatibility [83]. The composite hydrogels were loaded with doxorubicin and evaluated in vitro and in vivo. The cellulose/MXene gels demonstrated a slow increase in drug concentration over time, indicating NIR-stimulated controlled release. Results of biotoxicity assays proved that both the free and composite hydrogels were highly biocompatible. The photothermal properties of the composite hydrogels were also evaluated in vivo, utilizing gels ground into slurries and injected to tumor sites in mice. Bimodal cancer therapy was achieved with a combination of photothermal treatment and chemotherapeutic release from the hydrogels [83].

In another study, polyacrylamide (PAAm) hydrogels were modified with Ti3C2 nanosheets to increase their mechanical properties and enhance drug release [84]. Using bisacrylamide (BIS)/PAAm hydrogels as a control, in vitro testing was performed to compare the loading and release of chloramphenicol, a hydrophobic, antimicrobial agent, from the two gels. The nanogels had a greatly increased swelling ratio, higher drug loading capacity, and greater release. This can be attributed to the uniform pore distribution achieved with incorporation of the MXene sheets. While there was a positive correlation between concentration of Ti3C2 and inhibition of the burst release, even the highest concentration evaluated (0.4%) did not show a lower initial burst release than 0% [84]. The reason that the initial burst release was higher for gels containing Ti3C2 is because these gels exhibited better swelling and release properties, with a higher cumulative release. The higher burst was not due to lack of control but increased overall release of drug relative to the gels with 0% Ti3C2. It is possible that higher concentrations, such as 1% or above, would further inhibit the burst release; however, this may cause reduced swelling and hinder drug loading. Overall, incorporation of MXene nanosheets into hydrogels improved their mechanical strength and drug delivery properties, making MXenes a promising vehicle for drug delivery.

Transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)

Transition metal dichalcogenides are a class of 2D nanomaterials with a generic formula MX2, where M represents a group 4–10 transition metal and X represents a chalcogen. The hexagonal metal layer is sandwiched between two chalcogen layers. There are approximately 40 different categories of TMDs, each with unique physical and chemical properties. The cytocompatibility, versatile surface chemistry, and high photothermal conversion properties make TMDs a good candidate for use as a photothermal agent in drug delivery applications [85–88].

Layered MoS2 nanosheet–based delivery systems were synthesized for synergistic cancer therapy [89]. The nanosheets were first functionalized with DNA (D1/D2) and then loaded with doxorubicin. High loading was seen due to doxorubicin interactions with both the DNA as well as MoS2 nanosheets. MoS2/D2 and MoS2/D1 loaded nanosheets were compared for their anticancer effects. Both systems showed a significant increase in apoptotic cell population relative to free doxorubicin. The MoS2/D2 carrier showed fivefold increase, whereas the MoS2/D1 carrier showed a 3.4-fold increase [89]. In a recent study, hydrogels loaded with MoS2 nanosheet can be designed for on-demand release of doxorubicin by leveraging NIR-responsive characteristics of MoS2 nanosheet [88]. Interestingly, the wetting characteristics of these MoS2 nanosheet can be modulated by presence of atomic defects [90,91], a range of hydrophilic as well as hydrophobic drugs can be loaded for on-demand triggered release. High loading capacity, enhanced therapeutic effects, and stimuli-responsive release are promising characteristics for use of MoS2 nanosheets as small-molecule drug carriers.

TMDs have innate antibacterial properties that can be used in combination with similar agents for synergistic effects. Nanocomposite films with MoS2 and GO were investigated for their in vitro antibacterial activity [92]. Nanosheets of GO, MoS2, and GO-MoS2 were synthesized and equal concentrations of E. coli cells were dispersed onto each nanosheet. The hybrid film showed the greatest antibacterial effect, with 61% of loss of E. coli viability after 2 hours compared to approximately 55% and 45% for the MoS2 and GO films, respectively. SEM images of bacteria cells post-interaction with the nanofilm show compromised cell integrity, indicating direct physical disruption, oxidative stress, and charge transfer [92]. The behavior of this MoS2-based film suggests that this system is a promising candidate for an antibacterial film.

Transition metal oxides (TMOs)

TMO nanosheets can be obtained via delamination or deposition methods [93] and are highly advantageous because of their high biocompatibility and loading capabilities [94]. Manganese dioxide (MnO2), specifically, has proved to be beneficial for therapeutic delivery due to its harmless degradation products and stimuli–responsive properties [95].

MnO2 nanosheet–based carriers were prepared to load and deliver chlorine6 (Ce6) for cancer therapy [96]. The nanocarriers exhibited high loading of Ce6 (351 mg/g), presumably due to strong bonds between Mn atoms in the nanosheets and Mn atoms in Ce6. NIR and pH dependence of the release kinetics was tested by determination of release rates in acidic and neutral pH, with or without NIR stimulation. An attenuation of burst release was seen at pH of 5.0 and 7.4 without NIR laser irradiation, with the cumulative release doubled in acidic pH. With NIR stimulation, there was approximately a 3.5-fold increase in cumulative release and less attenuation of the burst release for both gels [96]. In acidic environments, degradation of MnO2 nanosheets forms Mn2+ ions that are nontoxic and can be used as contrast agent for MRI. This property was utilized in another study to design a cancer theranostic platform with curcumin-loaded, hyaluronic acid-functionalized MnO2 nanosheets [97]. A high loading efficiency of 75% was observed, in part due to electrostatic and van der Waals interactions. The nanosheets showed controlled release at neutral pH, with less than 20% cumulative release after 12 hours. In acidic pH, cumulative release increased to over 70% in the same time period. The amount of Mn2+ generated by reduction of the nanosheets was an adequate amount to perform MRI imaging, which proves the capability of MnO2 sheets to form effective cancer theranostic delivery carriers.

Polymer nanosheets

Natural and synthetic polymers are extensively researched and have numerous applications in biomedical engineering due to their high biocompatibility [98], high permeability [99,100], tunable properties [101], and degradation rates [102]. Polymer nanosheets (PNS) have been researched as alternatives to graphene and GO due to the cytotoxicity and low biocompatibility of the latter materials [103]. While PNS offers the advantage of biocompatibility, drug delivery applications require specific physiochemical properties to effectively perform targeted and prolonged delivery [102]. Research has thus been focused on utilizing different combinations of polymers to achieve specific properties for intended applications [104,105].

Poly (lactic acid) and poly (lactic-co-glycolic) acid – based nanofilms synthesized via layer-by-layer fabrication were assessed for their ability to perform topical and transdermal delivery. Betamethasone valerate (BV), an anti-inflammatory steroid, was used as the model drug. The nanofilms showed a high adhesiveness, and the skin concentration of BV after application was comparable to commercial ointments. The films were able to incorporate and release therapeutic levels of the model drug without compromising adhesiveness or breathability [106]. In another study, multilayered PCL-based nanosheets were investigated as controlled release vehicles for methyl orange, a model drug. The nanosheets exhibited thickness-dependent release, with a faster release for the thinnest films. Drug release was also pH dependent, showing a doubled release rate at pH of 11 compared to pH of 3 [107]. The simple fabrication methods and tunability of these materials are highly beneficial to drug delivery applications.

Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN)

Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) is a material composed of equal parts boron and nitride atoms and has a honeycomb lattice structure similar to graphene. Hexagonal boron nitride is one of the most researched forms of boron nitride along with cubic boron nitride. The B and N atoms form a strong covalent bond that creates the cage structure while the layers are held together with van der Waals interactions. In vitro studies have shown size-dependent biocompatibility of these materials and more in vivo work is necessary to determine long term performance [108]. However, multiple studies have reported the use of hBN to deliver cancer therapeutics [109,110]. In one study, palladium nanoparticles were grown on the surface of hydroxy boron nitride nanosheets (Pd@OH-BNNS) to load and deliver doxorubicin. The antitumor drug was efficiently loaded onto the nanosheets with a loading capacity of 32%. This is due to the π–π stacking as well as hydrophobic interactions between the hBN-based nanosheets and doxorubicin. Release was pH- and NIR-dependent, indicating the possibility of photothermal therapy and high drug release in a tumor microenvironment. In vivo testing also showed tumor growth inhibition and high efficacy during subcutaneous injection [111]. While the research of hBN nanosheets as drug delivery agents is still in its infancy, these materials have demonstrated properties that can be utilized to load and deliver small-molecule therapeutics. Further evaluation of their interaction with proteins and larger biomolecules, as well as interactions with cells, would need to be performed to widen their applications.

Conclusion and future directions

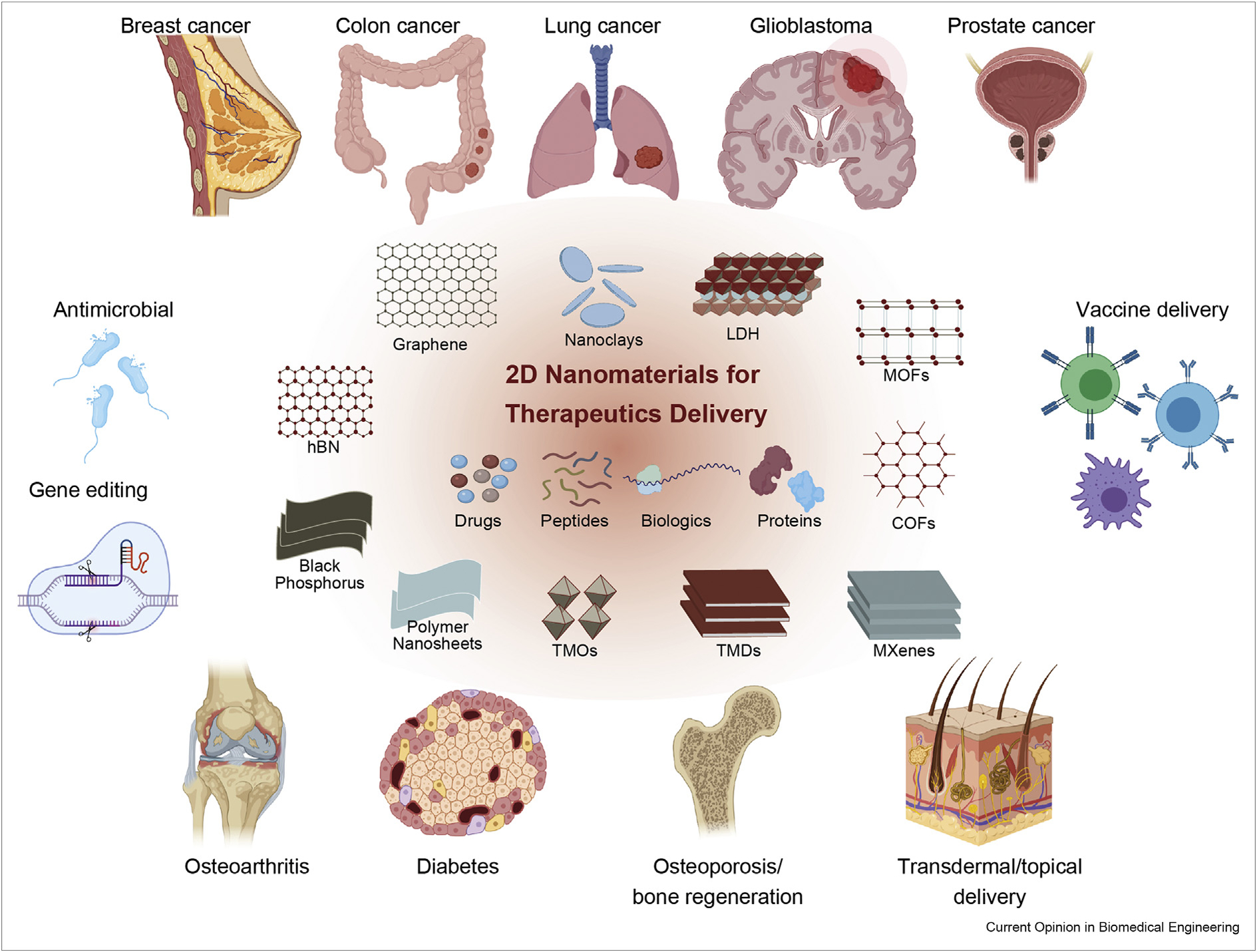

Two-dimensional nanomaterials can bind to numerous proteins and small molecules because of their sheet-like structure and large surface area. They also possess unique photothermal and chemical properties and are highly tunable. Stimuli-responsive degradation and high biocompatibility allow 2D materials to be utilized in targeted and sustained drug delivery. This review highlighted recent and promising studies involving 2D nanomaterial-based therapeutic delivery systems (Figure 4, Table 1). Graphene-based materials, GO specifically, has been the most extensively researched material in drug delivery among the various 2D nanomaterials. However, nanoclays, BP, and LDH have also been widely explored in therapeutic delivery due to their unique properties. Nanoclays have an anisotropic charge distribution that allows for simultaneous loading of differently charged molecules. The puckered honeycomb structure of BP increases the number of contact points on the surface and promotes higher drug loading. LDHs are hydrophilic, positively charged molecules that can efficiently bind to and stabilize proteins. MXenes, MOFs, COFs, and TMDs have been mainly applied within fields such as biosensing, photothermal therapy, and medical imaging; however, their photothermal, chemical, and electrical properties may be useful for delivery of chemotherapeutics, antibiotics, protein vaccines, and anti-inflammatory drugs. Although recent investigations have shown promising findings in vitro that indicate 2D nanomaterials could be used as drug delivery vehicles, more extensive in vivo assessments are still necessary to determine how surface modification, degradation, and clearance of these materials would affect their functionality. Overall, 2D nanomaterials are promising means for the development of delivery systems that exhibit efficient, localized, and prolonged delivery of therapeutics.

Figure 4.

2D nanomaterials have shown strong potential for various biomedical applications including cancer treatment, immunomodulation, regenerative medicine, vaccine delivery and antimicrobial.

Table 1.

Examples of drug delivery systems based on different types of 2D nanomaterials.

| 2D Nanomaterial | Delivery Molecule | Application | In vivo | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Carbon-based nanomaterials | GO | Doxorubicin | Colon cancer | Yes | [22] |

| GO | Bone morphogenic protein 2 | Osteoarthritis, bone regeneration | Yes | [25] | |

| GO | Docetaxel | Breast cancer | No | [21] | |

| GO | Ovalbumin (model protein 43 kDa) | Vaccine delivery | No | [26] | |

| rGO | Doxorubicin | Cervical cancer | No | [28] | |

| rGO | Insulin | Diabetes | No | [29] | |

| rGO | Paclitaxel | Breast cancer | No | [20] | |

| Graphene | Chlorhexidine | Antibacterial | No | [23] | |

| Nanoclays | Montmorillonite | gentamicin | Antibiotic | Yes | [37] |

| Laponite | Cisplatin | Breast cancer, cervical cancer | Yes | [34] | |

| Laponite | 4-fluorouracil | Breast cancer, cervical cancer | Yes | [34] | |

| Laponite | cyclophosphamide | Breast cancer, cervical cancer | Yes | [34] | |

| Laponite | rhBMP2 | Bone regeneration | No | [42] | |

| Laponite | TGF-β3 | Tissue regeneration | No | [42] | |

| Laponite | GM-CSF (Model protein (14.2 kDa)) | Vaccine delivery | No | [47] | |

| Laponite | Flt3L (Model protein [18.6 kDa]) | Vaccine delivery | No | [47] | |

| Laponite | IL-15 (model protein [13.3 kDa]) | Vaccine delivery | No | [47] | |

| Laponite | CCL20 (model protein (8.0 kDa)) | Vaccine delivery | No | [47] | |

| Laponite | IL-2 (model protein [17.2 kDa]) | Vaccine delivery | No | [47] | |

| Black Phosphorus (BP) | Cas9 | Genome editing, gene silencing | Yes | [57] | |

| Doxorubicin/PEITC | Breast cancer, multidrug resistant cancer | Yes | [52] | ||

| Ti-SA4 complexes | Antibacterial | No | [55] | ||

| Layered Double Hydroxides (LDHs) | Etoposide | Non-small cell lung cancer | Yes | [60] | |

| Butyrate | Antibacterial, breast cancer, liver cancer | Yes | [61] | ||

| Mg–Al–Cl | BSA (model protein (66.5 kDa)) | Protein stabilization | No | [62] | |

| Metal Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | ZIF-8 | TMV (model protein (300 × 18 nm)) | Vaccine delivery | Yes | [74] |

| ZIF-8 | Curcumin | Anti-inflammatory, anti-HIV | No | [70] | |

| Zn4O(dmcapz)3 | Aminobenzoic acid | UV blocker | No | [71] | |

| Zn4O(dmcapz)3 | Benzocaine | Anesthetic | No | [71] | |

| Zn4O(dmcapz)3 | 5-fluorouracil | Antineoplastic agent, anticancer | No | [71] | |

| Zn4O(dmcapz)3 | Caffeine | Liporeductor cosmetic | No | [71] | |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | PEG-CCM@APTES-COF-1 | Doxorubicin | Cervical cancer | Yes | [76] |

| Boroxine-linked COF | Insulin | Diabetes | Yes | [79] | |

| Imine-derived COF | Methylene blue (model drug (319.8 g/mol)) | Prolonged delivery | No | [77] | |

| Imine-derived COF | Oxytocin | Uterine contraction stimulant | No | [77] | |

| Metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) | Ti3C2 | Doxorubicin | Astroglioma, glioblastoma, | Yes | [83] |

| Ti3C2 | Chloramphenicol | liver cancer Antimicrobial | No | [84] | |

| Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs) | MoS2 | Doxorubicin | Breast cancer | No | [88,89] |

| Transition Metal Oxides (TMOs) | MnO3 | Cisplatin | Non-small cell lung cancer | Yes | [95] |

| MnO2 | Ce6 | Prostate cancer | No | [96] | |

| Polymer nanosheets | PLA/PLGA | Betamethasone valerate | Topical and transdermal delivery | Yes | [106] |

| PEO/PCL-PEI-b-PCL | Methyl orange (model drug [327.3 g/mol]) | Controlled release | No | [107] | |

| Hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) nanosheets | Doxorubicin | Anticancer | Yes | [111] | |

| 5-fluorouracil | Antineoplastic agent, anticancer | No | [109] | ||

| 6-mercaptopurine | Anticancer | No | [109] | ||

| 6-thioguanine | Anticancer | No | [109] | ||

GO, graphene oxide; 2D, 2 dimensional; PLA, poly(lactic acid); PLGA, poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid; BSA, bovine serum albumin; COF, covalent organic framework.

Even though recent research has generated promising results, further investigation is necessary to allow for clinical translation of these 2D nanomaterials. Although many studies focus on loading capabilities and release kinetics of the nanocarriers, little work explores their long-term cytotoxicity or clearance from the body. When applied to chemotherapeutic delivery, multiple studies attribute the high nanocarrier accumulation in the tumor to the enhanced permeability and retention effect of nanoparticles which indicates there is room for improvement. To achieve more robust targeting for cancer among other applications, more research investigating the use of targeting ligands is crucial. Other promising methods to enhance the properties of 2D nanomaterials include composite systems with hydrogels or other 2D materials (MXene hydrogels, GO-MoS2 composite systems). Because of the high variation in chemical properties and surface interactions of these materials, an extensive biosafety analysis of each specific hybrid material would be necessary. The majority of current research has focused on cancer drugs or other small molecules. Further investigation into the interactions of 2D nanomaterials with biomolecules could lead to expanded applications in vaccines, immune engineering and in situ regeneration strategies [112]. The effects of nanomaterial size and structure on cellular uptake mechanisms should also be explored further, as this could lead to improved delivery of drugs through selective channels such as the blood–brain barrier. Although significant progress remains before the clinical application of these materials is possible, 2D nanomaterials have shown great potential in effective small-molecule drug, peptide, and protein delivery.

Acknowledgements

A.K.G. acknowledges financial support from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director’s New Innovator Award (DP2 EB026265) and TAMU President’s Excellence Fund (X-grant and T3). R.A.U acknowledges financial support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) T32 training grant (1T32GM135748). All the schematics are prepared by the authors and some of the icons are obtained from www.Biorender.com.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

- 1.Kalepu S, Nekkanti V: Insoluble drug delivery strategies: review of recent advances and business prospects. Acta Pharm Sin B 2015, 5:442–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li C, Wang J, Wang Y, Gao H, Wei G, Huang Y, Yu H, Gan Y, Wang Y, Mei L, Chen H, Hu H, Zhang Z, Jin Y: Recent progress in drug delivery. Acta Pharm Sin B 2019, 9:1145–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murali A, Lokhande G, Deo KA, Brokesh A, Gaharwar AK: Emerging 2D nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Mater Today 2021. 10.1016/j.mattod.2021.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh N, Joshi A, Toor AP, Verma G: Drug delivery: advancements and challenges. In Nanostructures for drug delivery; 2017:865–886. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chimene D, Alge DL, Gaharwar AK: Two-Dimensional nanomaterials for biomedical applications: emerging trends and future prospects. Adv Mater 2015, 27:7261–7284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Chhowalla M, Liu Z: 2D nanomaterials: graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem Soc Rev 2018, 47: 3015–3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasoulzadeh M, Namazi H: Carboxymethyl cellulose/graphene oxide bio-nanocomposite hydrogel beads as anticancer drug carrier agent. Carbohydr Polym 2017, 168: 320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Gao Q, Li X, Gao YF, Han HJ, Jin Q, Yao K, Ji J: Ofloxacin loaded MoS2 nanoflakes for synergistic mild-temperature photothermal/antibiotic therapy with reduced drug resistance of bacteria. Nano Res 2020, 13:2340–2350. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuang WR, Wang Y, Cui PF, Xing L, Lee J, Kim D, Jiang HL, Oh YK: Applications of pi-pi stacking interactions in the design of drug-delivery systems. J Contr Release 2019, 294: 311–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Fan T, Chen W, Li Y, Wang B: Recent advances of two-dimensional materials in smart drug delivery nano-systems. Bioact Mater 2020, 5:1071–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Y, Fatemi V, Demir A, Fang S, Tomarken SL, Luo JY, Sanchez-Yamagishi JD, Watanabe K, Taniguchi T, Kaxiras E, Ashoori RC, Jarillo-Herrero P: Correlated insulator behaviour at half-filling in magic-angle graphene superlattices. Nature 2018, 556:80–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun HT, Mei L, Liang JF, Zhao ZP, Lee C, Fei HL, Ding MN, Lau J, Li MF, Wang C, Xu X, Hao GL, Papandrea B, Shakir I, Dunn B, Huang Y, Duan XF: Three-dimensional holey-graphene/niobia composite architectures for ultrahigh-rate energy storage. Science 2017, 356:599–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang SX, Jiang CB, Wei SH: Gas sensing in 2D materials. Appl Phys Rev 2017, 4:34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goenka S, Sant V, Sant S: Graphene-based nanomaterials for drug delivery and tissue engineering. J Contr Release 2014, 173:75–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling BP, Chen HT, Liang DY, Lin W, Qi XY, Liu HP, Deng X: Acidic pH and high-H2O2 dual tumor microenvironment-responsive nanocatalytic graphene oxide for cancer selective therapy and recognition. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11:11157–11166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Homaeigohar S, Elbahri M: Graphene membranes for water desalination. NPG Asia Mater 2017, 9:16. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Cote LJ, Kim F, Yuan W, Shull KR, Huang J: Graphene oxide sheets at interfaces. J Am Chem Soc 2010, 132: 8180–8186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh DP, Herrera CE, Singh B, Singh S, Singh RK, Kumar R: Graphene oxide: an efficient material and recent approach for biotechnological and biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng C-Mater Biol Appl 2018, 86:173–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Z, Zhang Q, Lay Yap P, Ni Y, Losic D: Magnetic reduced graphene oxide as a nano-vehicle for loading and delivery of curcumin. Spectrochim Acta Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2021, 252: 119471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Cai W, Hao L, Feng S, Lin Q, Jiang W: Preparation of Fe3O4/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites with good dispersibility for delivery of paclitaxel. J Nanomater 2017, 2017:6702890. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasrollahi F, Varshosaz J, Khodadadi AA, Lim S, Jahanian-Najafabadi A: Targeted delivery of docetaxel by use of transferrin/poly(allylamine hydrochloride)-functionalized graphene oxide nanocarrier. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8:13282–13293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee H, Kim J, Lee J, Park H, Park Y, Jung S, Lim J, Choi HC, Kim WJ: In vivo self-degradable graphene nanomedicine operated by DNAzyme and photo-switch for controlled anticancer therapy. Biomaterials 2020, 263. * The researchers in this study designed a catalytic graphene oxide-based nanomedicine to deal with the limited degradability of surface modified GO. The delivery system included Doxorubicin-loaded DNA which was bound to GO. Upon NIR stimulus, the DNA would denature and release the intended drug and then bind to hemin on the GO surface. This caused a reaction that degraded the GO and allowed for efficient clearance. In vivo assessments showed promising results, and the researchers were able to enhance and benefit from the properties of GO with surface modification while the addition of DNA helped maintain biodegradability. This concept of catalytic medicine increases the potential for in vivo success of graphene oxide-based drug delivery vehicles.

- 23.Scaffaro R, Maio A, Botta L, Gulino EF, Gulli D: Tunable release of Chlorhexidine from Polycaprolactone-based filaments containing graphene nanoplatelets. Eur Polym J 2019, 110: 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keeney M, Jiang XY, Yamane M, Lee M, Goodman S, Yang F: Nanocoating for biomolecule delivery using layer-by-layer self-assembly. J Mater Chem B 2015, 3:8757–8770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong C, Feng J, Lin XJ, Bao Q: Continuous release of bone morphogenetic protein-2 through nano-graphene oxide-based delivery influences the activation of the NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway. Int J Nanomed 2017, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan T, Zhang HJ, Huang DD, Feng SN, Fujita M, Gao XD: Chitosan-functionalized graphene oxide as a potential immunoadjuvant. Nanomaterials 2017, 7:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Fierens K, Zhang Z, Vanparijs N, Schuijs MJ, Van Steendam K, Gracia NF, De Rycke R, De Beer T, De Beuckelaer A, De Koker S, Deforce D, Albertazzi L, Grooten J, Lambrecht BN, De Geest BG: Spontaneous protein adsorption on graphene oxide nanosheets allowing efficient intracellular vaccine protein delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8: 1147–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang C, Song J, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Deng M, Gao W, Zhang J: Facile approach to prepare rGO@Fe3O4 microspheres for the magnetically targeted and NIR-responsive chemo-photothermal combination therapy. Nanoscale Research Letters 2020, 15:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teodorescu F, Oz Y, Quéniat G, Abderrahmani A, Foulon C, Lecoeur M, Sanyal R, Sanyal A, Boukherroub R, Szunerits S: Photothermally triggered on-demand insulin release from reduced graphene oxide modified hydrogels. J Contr Release 2017, 246:164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MH, Choi G, Elzatahry A, Vinu A, Choy YB, Choy JH: Review of clay-drug hybrid materials for biomedical applications: administration routes. Clay Clay Miner 2016, 64:115–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dawson JI, Oreffo ROC: Clay: New opportunities for tissue regeneration and biomaterial design. Adv Mater 2013, 25: 4069–4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaharwar AK, Cross LM, Peak CW, Gold K, Carrow JK, Brokesh A, Singh KA: 2D nanoclay for biomedical applications: regenerative medicine, therapeutic delivery, and additive manufacturing. Adv Mater 2019, 31:1900332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghadiri M, Chrzanowski W, Rohanizadeh R: Biomedical applications of cationic clay minerals. RSC Adv 2015, 5: 29467–29481. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bera H, Ippagunta SR, Kumar S, Vangala P: Core-shell alginate-ghatti gum modified montmorillonite composite matrices for stomach-specific flurbiprofen delivery. Mater Sci Eng C-Mater Biol Appl 2017, 76:715–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Becher TB, Mendonca MCP, de Farias MA, Portugal RV, de Jesus MB, Ornelas C: Soft nanohydrogels based on laponite nanodiscs: a versatile drug delivery platform for theranostics and drug cocktails. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10: 21891–21900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao SL, Castro R, Maciel D, Goncalves M, Shi XY, Rodrigues J, Tomas H: Fine tuning of the pH-sensitivity of laponite-doxorubicin nanohybrids by polyelectrolyte multilayer coating. Mater Sci Eng C-Mater Biol Appl 2016, 60:348–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi H, Zhang R, Feng S, Wang J: Influence of laponite on the drug loading and release performance of LbL polyurethane/poly(acrylic acid) multilayers. J Appl Polym Sci 2018, 136: 47348. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang BL, Liu HH, Sun L, Jin YY, Ding XX, Li LL, Ji J, Chen H: Construction of high drug loading and enzymatic degradable multilayer films for self-defense drug release and long-term biofilm inhibition. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19:85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lad SP, Nathan JK, Boakye M: Trends in the use of bone morphogenetic protein as a substitute to autologous iliac crest bone grafting for spinal fusion procedures in the United States. Spine 2011, 36:E274–E281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carragee EJ, Hurwitz EL, Weiner BK: A critical review of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 trials in spinal surgery: emerging safety concerns and lessons learned. Spine J 2011, 11:471–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, Campos EVR, Rodriguez-Torres MDP, Acosta-Torres LS, Diaz-Torres LA, Grillo R, Swamy MK, Sharma S, Habtemariam S, Shin HS: Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol 2018, 16:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Page DJ, Clarkin CE, Mani R, Khan NA, Dawson JI, Evans ND: Injectable nanoclay gels for angiogenesis. Acta Biomater 2019, 100:378–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Howell DW, Peak CW, Bayless KJ, Gaharwar AK: 2D nanosilicates loaded with proangiogenic factors stimulate endothelial sprouting. Adv Biosystems 2018, 2:1800092. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peak CW, Singh KA, Ma Adlouni, Chen J, Gaharwar AK: Printing therapeutic proteins in 3D using nanoengineered bioink to control and direct cell migration. Adv Healthcare Mater 2019, 8:1801553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cross LM, Shah K, Palani S, Peak CW, Gaharwar AK: Gradient nanocomposite hydrogels for interface tissue engineering. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med 2018, 14: 2465–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lokhande G, Carrow JK, Thakur T, Xavier JR, Parani M, Bayless KJ, Gaharwar AK: Nanoengineered injectable hydrogels for wound healing application. Acta Biomater 2018, 70: 35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cross LM, Carrow JK, Ding XC, Singh KA, Gaharwar AK: Sustained and prolonged delivery of protein therapeutics from two-dimensional nanosilicates. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11:6741–6750. * Limitations to protein delivery include high dose requirements and the susceptibility of proteins to denaturation during transport, causing improper function. In this study, 2D Laponite nanodiscs were investigated for their ability to load, stabilize, and release protein over a prolonged period. Specifically, recombinant human bone morphogenic protein 2 (rhBMP2) and transforming growth factor beta-3 (TGF-β3) were used to investigate the nanosilicate discs for orthopedic regeneration applications. Laponite was able to bind efficiently to the proteins and maintain a protein activity consistent with the freely administered protein, while using a relative concentration that was only 10% of that of the control group. The findings from this research can be applied to various proteins to improve vaccine delivery using 2D nanosilicates.

- 48.Koshy ST, Zhang DKY, Grolman JM, Stafford AG, Mooney DJ: Injectable nanocomposite cryogels for versatile protein drug delivery. Acta Biomater 2018, 65:36–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu YJ, Shi Z, Shi XY, Zhang K, Zhang H: Recent progress in black phosphorus and black-phosphorus-analogue materials: properties, synthesis and applications. Nanoscale 2019, 11:14491–14527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu H, Neal AT, Zhu Z, Luo Z, Xu X, Tománek D, Ye PD: Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano 2014, 8:4033–4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaddam SK, Pothu R, Saran A, Boddula R: Biomedical applications of black phosphorus. In Black phosphorus: synthesis, Properties and applications. Edited by Inamuddin Boddula R, Asiri AM, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020: 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi JR, Yong KW, Choi JY, Nilghaz A, Lin Y, Xu J, Lu XN: Black phosphorus and its biomedical applications. Theranostics 2018, 8:1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wu F, Zhang M, Chu XH, Zhang QC, Su YT, Sun BH, Lu TY, Zhou NL, Zhang J, Wang JX, Yi XY: Black phosphorus nanosheets-based nanocarriers for enhancing chemotherapy drug sensitiveness via depleting mutant p53 and resistant cancer multimodal therapy. Chem Eng J 2019, 370: 387–399. * Resistant cancer cells contain the mutant p53 that provides the tumors anti-apoptosis capabilities. This reduces the effect that chemotherapy drugs have on tumors. In this study, black phosphorus was used to deliver doxorubicin (DOX), as a chemotherapeutic, as well as phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC) which remove p53 from the cell. The structure and chemical properties of black phosphorus enhance binding capabilites relative to other 2D nanomaterials, and this feature is utilized here to load multiple agents and control the release of both. In vivo assessments showed that the inclusion of BP nanosheets caused a greater reduction of tumor volume relative to free DOX. Results also indicated that BP is highly responsive to NIR-stimulus and can be used as a photothermal agent to treat cancers.

- 54.Aksoy I, Küçükkeçeci H, Sevgi F, Metin Ö, Hatay Patir I: Photothermal antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of black phosphorus/gold nanocomposites against pathogenic bacteria. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020, 12:26822–26831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ouyang J, Liu R-Y, Chen W, Liu Z, Xu Q, Zeng K, Deng L, Shen L, Liu Y-N: Black phosphorus based synergistic antibacterial platform against drug resistant bacteria. J Mater Chem B 2018, 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li Z, Wu L, Wang H, Zhou W, Liu H, Cui H, Li P, Chu PK, Yu X-F: Synergistic antibacterial activity of black phosphorus nanosheets modified with titanium aminobenzenesulfanato complexes. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2019, 2:1202–1209. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kandil R, Merkel OM: Recent progress of polymeric nanogels for gene delivery. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 2019, 39: 11–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou WH, Cui HD, Ying LM, Yu XF: Enhanced cytosolic delivery and release of CRISPR/Cas9 by black phosphorus nanosheets for genome editing. Angew Chem Int Ed 2018, 57: 10268–10272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cao Z, Li B, Sun L, Li L, Xu ZP, Gu Z: 2D layered double hydroxide nanoparticles: recent progress toward preclinical/clinical nanomedicine. Small Methods 2020, 4:1900343. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuthati Y, Kankala RK, Lee C-H: Layered double hydroxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications: current status and recent prospects. Appl Clay Sci 2015, 112–113:100–116. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu RR, Wang QX, Zhu YJ, Wang ZQ, Zhang HX, Wu B, Wu XZ, Wang SL: pH sensitive nano layered double hydroxides reduce the hematotoxicity and enhance the anticancer efficacy of etoposide on non-small cell lung cancer. Acta Biomater 2016, 29:320–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang DH, Peng F, Li JH, Qiao YQ, Li QW, Liu XY: Butyrate-inserted Ni-Ti layered double hydroxide film for H2O2-mediated tumor and bacteria killing. Mater Today 2017, 20: 238–257. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tokudome Y, Fukui M, Tarutani N, Nishimura S, Prevot V, Forano C, Poologasundarampillai G, Lee PD, Takahashi M: High-density protein loading on hierarchically porous layered double hydroxide composites with a rational mesostructure. Langmuir 2016, 32:8826–8833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yazdani P, Mansouri E, Eyvazi S, Yousefi V, Kahroba H, Hejazi MS, Mesbahi A, Tarhriz V, Abolghasemi MM: Layered double hydroxide nanoparticles as an appealing nanoparticle in gene/plasmid and drug delivery system in C2C12 myoblast cells. Artificial Cells, Nanomed Biotechnol 2019, 47:436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang J, Yang Y-W: Metal–organic frameworks for biomedical applications. Small 2020, 16:1906846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arun Kumar S, Balasubramaniam B, Bhunia S, Jaiswal MK, Verma K, Khademhosseini A, Gupta RK, Gaharwar AK: Two-dimensional metal organic frameworks for biomedical applications. WIREs Nanomed Nanobiotechnol 2021, 13:e1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lee HP, Gaharwar AK: Light-responsive inorganic biomaterials for biomedical applications. Adv Sci 2020, 7: 2000863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kumari N, Kulkarni AA, Lin X, McLean C, Ammosova T, Ivanov A, Hipolito M, Nekhai S, Nwulia E: Inhibition of HIV-1 by curcumin A, a novel curcumin analog. Drug Des Dev Ther 2015, 9: 5051–5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jahangirian H, Kalantari K, Izadiyan Z, Rafiee-Moghaddam R, Shameli K, Webster TJ: A review of small molecules and drug delivery applications using gold and iron nanoparticles. Int J Nanomed 2019, 14:1633–1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tiwari A, Singh A, Garg N, Randhawa JK: Curcumin encapsulated zeolitic imidazolate frameworks as stimuli responsive drug delivery system and their interaction with biomimetic environment. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Noorian SA, Hemmatinejad N, Navarro JAR: Bioactive molecule encapsulation on metal-organic framework via simple mechanochemical method for controlled topical drug delivery systems. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 2020, 302: 110199. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang X, Lan PC, Ma S: Metal–organic frameworks for enzyme immobilization: beyond host matrix materials. ACS Cent Sci 2020, 6:1497–1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li S, Dharmarwardana M, Welch RP, Benjamin CE, Shamir AM, Nielsen SO, Gassensmith JJ: Investigation of controlled growth of metal–organic frameworks on anisotropic virus particles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10:18161–18169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Luzuriaga MA, Welch RP, Dharmarwardana M, Benjamin CE, Li SB, Shahrivarkevishahi A, Popal S, Tuong LH, Creswell CT Gassensmith JJ: Enhanced stability and controlled delivery of MOF-encapsulated vaccines and their immunogenic response in vivo. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019, 11: 9740–9746. * As proteins are becoming increasingly sought after as personalized therapeutic solutions, research on ways to maintain protein stability during delivery has increased. In this study, zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8), a type of metal organic framework (MOF), was used to encapsulate tobacco mosaic virus as a model protein. The ability of the MOF system to undergo stresses while maintaining protein structure was analyzed, as well as the protein release, biocompatibility and antibody response. ZIF-8 incorporation greatly improved protein stability through changes in temperature as well as other stresses. The antibody response of the MOF-bound TMV was similar to free TMV, which means that all of the protein was released. The performance of the ZIF-8 encapsulation in this study highlights the potential of MOFs as protein delivery agents.

- 75.Bhunia S, Deo KA, Gaharwar AK: 2D covalent organic frameworks for biomedical applications. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30: 2002046. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang GY, Li XL, Liao QB, Liu YF, Xi K, Huang WY, Jia XD: Water-dispersible PEG-curcumin/amine-functionalized covalent organic framework nanocomposites as smart carriers for in vivo drug delivery. Nat Commun 2018, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rezvani Alanagh H, Rostami I, Taleb M, Gao X, Zhang Y, Khattak AM, He X, Li L, Tang Z: Covalent organic framework membrane for size selective release of small molecules and peptide in vitro. J Mater Chem B 2020, 8:7899–7903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu C, Wan T, Wang H, Zhang S, Ping Y, Cheng Y: A boronic acid–rich dendrimer with robust and unprecedented efficiency for cytosolic protein delivery and CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Science Adv 2019, 5, eaaw8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Zhang G, Ji Y, Li X, Wang X, Song M, Gou H, Gao S, Jia X: Polymer–covalent organic frameworks composites for glucose and pH dual-responsive insulin delivery in mice. Adv Healthcare Mater 2020, 9:2000221. * Self-administration of insulin, the main treatment method of Type 1 diabetes, is difficult due to the financial burden to patients, the precision required to to administer the correct dosage, and the low patient compliance due to the frequent injections. Here, a covalent organic framework (COF)-based delivery system was designed to release insulin in response to both glucose and pH levels. The nanocarriers performed well both in vitro and in vivo, showing strong stimuli-responsiveness and high stability in physiological conditions. Glucose levels were regulated for 72h in mice with only one injection, and insulin activity was increased with the use of the COF. The results of this experiment indicate the potential of COF-based nanocomposites for delivery of various proteins.

- 80.Lin H, Chen Y, Shi J: Insights into 2D MXenes for versatile biomedical applications: current advances and challenges ahead. Adv Sci 2018, 5:1800518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Tang WT, Dong ZL, Zhang R, Yi X, Yang K, Jin ML, Yuan C, Xiao ZD, Liu Z, Cheng L: Multifunctional two-dimensional core-shell MXene@Gold nanocomposites for enhanced photo-radio combined therapy in the second biological window. ACS Nano 2019, 13:284–294. * 2D MXenes have high hydrophilicity, high stability, and good optical properties which allow for their use in theranostic applications. While some researchers have investigated the drug loading and release capabilities of MXenes, this paper was focused on their photothermal properties. Ti3C2 nanosheets were used to synthesize an image-guided photothermal treatment method. Photothermal therapy (PTT) is a non invasive method that involves localized delivery of any agent with photothermal properties, followed by NIR light stimulation to produce hyperthermic conditions for tumor cell ablation. In this study, the MXene based composites were able to accumulate at the tumor site and exhibit prolonged circulation. The carriers responded efficiently to NIR-stimulus and showed high antitumor activity. The results of this study indicate that MXenes alone can treat cancer via photothermal methods. These properties, combined with the target-specific accumulation and enhanced circulation time seen in this study as well as the high drug loading capabilites due to the 2D strucutre show the many benefits of MXenes as delivery agents. It is possible to load chemotherapeutics onto these materials and achieve bimodal cancer therapy.

- 82.Lin H, Gao SS, Dai C, Chen Y, Shi JL: A two-dimensional biodegradable niobium carbide (MXene) for photothermal tumor eradication in NIR-I and NIR-II biowindows. J Am Chem Soc 2017, 139:16235–16247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xing CY, Chen SY, Liang X, Liu Q, Qu MM, Zou QS, Li JH, Tan H, Liu LP, Fan DY, Zhang H: Two-Dimensional MXene (Ti3C2)-integrated cellulose hydrogels: toward smart three-dimensional network nanoplatforms exhibiting light-induced swelling and bimodal photothermal/chemotherapy anticancer activity. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10: 27631–27643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhang P, Yang XJ, Li P, Zhao Y, Niu QJ: Fabrication of novel MXene (Ti3C2)/polyacrylamide nanocomposite hydrogels with enhanced mechanical and drug release properties. Soft Matter 2020, 16:162–169. * In this study, Ti3C2 nanosheets were utilized as crosslinkers for drug releasing hydrogels. The structure and porosity of Ti3C2 MXenes were able to enhance the mechanical properties and flexibility of the hydrogels. There was a direct relationship between the hindrance of an initial burst relase and increased concentration of Ti3C2. The MXene sheets were also able to improve the drug loading and cumulative release of the hydrogels. These results highlight the benefits of MXenes as carriers for hydrophbic small molecule drugs.

- 85.Zhou X, Sun H, Bai X: Two-Dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides: synthesis, biomedical applications and biosafety evaluation. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nafiujjaman M, Nurunnabi M: Chapter 5 - graphene and 2D materials for phototherapy. In Biomedical applications of graphene and 2D nanomaterials. Edited by Nurunnabi M, McCarthy JR, Elsevier; 2019:105–117. [Google Scholar]