Abstract

Background:

The growing burden associated with population aging, dementia and multimorbidity poses potential challenges for the sustainability of health systems worldwide. We sought to examine how the intersection among age, dementia and greater multimorbidity is associated with health care costs.

Methods:

We did a retrospective population-based cohort study in Alberta, Canada, with adults aged 65 years and older between April 2003 and March 2017. We identified 31 morbidities using algorithms (30 algorithms were validated), which were applied to administrative health data, and assessed costs associated with hospital admission, provider billing, ambulatory care, medications and long-term care (LTC). Actual costs were used for provider billing and medications; estimated costs for inpatient and ambulatory patients were based on the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s resource intensive weights and Alberta’s cost of a standard hospital stay. Costs for LTC were based on an estimated average daily cost.

Results:

There were 827 947 people in the cohort. Dementia was associated with higher mean annual total costs and individual mean component costs for almost all age categories and number of comorbidities categories (differences in total costs ranged from $27 598 to $54 171). Similarly, increasing number of morbidities was associated with higher mean total costs and component costs (differences in total costs ranged from $4597 to $10 655 per morbidity). Increasing age was associated with higher total costs for people with and without dementia, driven by increasing LTC costs (differences in LTC costs ranged from $115 to $9304 per age category). However, there were no consistent trends between age and non-LTC costs among people with dementia. When costs attributable to LTC were excluded, older age tended to be associated with lower costs among people with dementia (differences in non-LTC costs ranged from −$857 to −$7365 per age category).

Interpretation:

Multimorbidity, older age and dementia were all associated with increased use of LTC and thus health care costs, but some costs among people with dementia decreased at older ages. These findings illustrate the complexity of projecting the economic consequences of the aging population, which must account for the interplay between multimorbidity and dementia.

The presence of multiple chronic conditions is termed multimorbidity1 and is associated with worse clinical outcomes than good health or the presence of a single chronic condition.2–5 Dementia is an important contributor to multimorbidity and factors that contribute to multimorbidity (such as vascular disease) can also cause dementia. Like multimorbidity, dementia increases in prevalence with age. Therefore, the aging of the general population is expected to lead to further increases in the burden of both multimorbidity and dementia. Since both dementia and multimorbidity are independently associated with increased health care costs and an increased likelihood of requiring long-term care (LTC),6,7 the intersection of age, dementia and multimorbidity poses potential challenges for the sustainability of health systems worldwide.8 Given the potential for overlap and statistical interactions between these various exposures, there is potential for bias if individual associations are used to examine associations with cost. Rather, an approach that simultaneously considers the associations among age, dementia, morbidity and health care costs is preferable.

We used a large population-based data set of all 827 947 people aged 65 years or older who lived in a defined geographic area to characterize the frequency of dementia and 30 other common chronic conditions. Our goal was to advance the literature by considering the interplay between these 3 key exposures and total health care costs.

Methods

Study design and participants

For this retrospective population-based cohort study, we assembled a cohort of adults aged 65 years or older who lived in Alberta, Canada, between April 2003 and March 2017. We followed participants from April 2003, their 65th birthday or their registration with Alberta Health (whichever was later) until March 2017, death or migration out of the province.

We report this study according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guideline.9

Data sources

We examined the associations among age, dementia and burden of morbidity with total health care costs, composed of costs related to hospital admission, provider billing, use of ambulatory or emergency care, medications and long-term care (defined as care and services for those who cannot live independently or who require on-site nursing care, 24-hour supervision or personal support).10

We used the Alberta Kidney Disease Network (AKDN) database, which incorporates administrative data from Alberta Health (the provincial health ministry) such as provider claims, hospital admissions and ambulatory care utilization; Alberta laboratory data and Alberta Blue Cross prescription data.11 All people registered with Alberta Health were included in the AKDN database; all Alberta residents are eligible for insurance coverage by Alberta Health and more than 99% participate in the program. We linked postal codes for the last known residential address of each participant to Statistics Canada’s Postal Code Conversion File Plus (www.statcan.ca) to obtain rural or urban status and neighbourhood (postal code) income quintiles for each relevant fiscal year.

Morbidities

We used a previously published list of validated algorithms for 29 chronic morbidities that could be applied to claims data and had positive predictive values of at least 70%:12 dementia, alcohol misuse, asthma, atrial fibrillation, lymphoma, non-metastatic cancer (breast, cervical, colorectal, pulmonary and prostate), metastatic cancer, chronic heart failure, chronic pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic hepatitis B, cirrhosis, severe constipation, depression, diabetes, epilepsy, hypertension, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, multiple sclerosis, myocardial infarction, Parkinson disease, peptic ulcer disease, peripheral vascular disease, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, schizophrenia, and stroke or transient ischemic attack. Dementia was 1 of the 29 morbidities and was defined by the presence of at least 1 hospital admission or 2 physician claims within 2 years (the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] codes 290, 294.1 and 331.2 or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision [ICD-10] codes F00-F03, F05.1, G30 and G31.1).13

Subsequently, we found a validated algorithm for gout14 meeting the above criteria, so gout was additionally included in the final set of chronic morbidities. We also considered chronic kidney disease as a 31st morbidity that was defined by any of the following: mean annual estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2; a median annual presence of albuminuria (albumin to creatinine ratio ≥ 30 mg/g, protein to creatinine ratio ≥ 150 mg/g or dipstick proteinuria ≥ trace); 2 outpatient physician claims for dialysis; or 1 hospital admission or 1 outpatient claim for kidney transplantation.12

We classified each participant with respect to the presence or absence of dementia and the 30 other chronic morbidities for each fiscal year.15 If a participant developed a morbidity within a fiscal year or at any point previously (look-back extended as far as April 1994 where records were available), we classified the patient as having the morbidity. Detailed methods for classifying morbidity status and the specific algorithms used are found elsewhere.12

Costs and long-term care

The primary outcome was mean annual total health care costs; the cost components were hospital admission, provider visits (primary care or specialist care), ambulatory care (including emergency department visits), medications and LTC. For all hospital admissions and ambulatory care classification system (ACCS) charges between fiscal years 2004 and 2017, we used the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s resource intensity weights (RIWs) from the administrative data and Alberta’s cost of a standard hospital stay (CSHS).16 We used grouper codes for ACCS charges from fiscal years 2004 to 2010 and RIW and CSHS for the years thereafter. Costs for provider visits (inpatient and outpatient) were the actual amounts charged to Alberta Health Services; for physicians on the alternative payment program we based costs on the mean amounts charged by the other physicians. Medication costs were those listed with Alberta Blue Cross.

We measured time residing in an LTC home (e.g., nursing homes, auxiliary hospitals) and estimated costs on the basis of the average daily cost (Can$218.16; from Alberta Health) of all such homes in Alberta (individual-level data on the type of LTC were not available). We classified participants as residing in LTC if they were discharged to an LTC home after hospital admission or if we identified 2 provider claims at least 30 days apart for services provided in an LTC home; we deemed LTC to have begun on the earlier of the date of discharge and the date of the first claim, respectively. All costs are reported in Can$1000 units and are inflated to 2017 costs using the Consumer Price Index for all items in Canada. All data (demographics, morbidities and costs) were linked and organized by participant and fiscal year.

Statistical analysis

We did analyses with Stata MP 15·1 (www.stata.com) and reported baseline (first fiscal year within follow-up) descriptive statistics as counts and percentages, or medians and interquartile ranges, as appropriate. To examine the associations between dementia, increasing morbidity burden and age with cost outcomes, we used generalized linear models with a zero-inflated negative binomial distribution17 and a log link. A number of models were considered initially (i.e., mixed, generalized estimating equations, structural equations) but because of the distributions of the cost outcomes (excess zeros with long right tails) only the zero-inflated negative binomials models converged. We allowed for intraparticipant correlation to correct any nonindependence in our standard errors by using a clustered sandwich estimator; this allowed participants to contribute multiple fiscal years of cost data.

We regressed outcomes on dementia, the number of other (nondementia) morbidities (categorized as none, 1, 2, 3 and ≥ 4), age (categorized as 65–74, 75–84 and ≥ 85 yr), their 3-way interaction and all three 2-way interactions, as well as sex, rural or urban residence and the lowest neighbourhood (postal code) income quintile. The 2-way interaction terms allowed 1 variable to modify the association between another variable and the outcome either synergistically (greater than the sum of 2 individual main effects) or antagonistically (less than the sum of 2 individual main effects). The 3-way interaction term allowed 1 variable to modify the association between the combined effects of 2 other variables on the outcome, again either synergistically or antagonistically.

We allowed all covariates to be updated each fiscal year; an offset term was used to account for the log of partial and full years. Only rural or urban residence and the lowest neighbourhood income quintile had missing values; both of these were 7%. In the models, missing values were imputed with the most frequent category (i.e., imputed as urban and not the lowest neighbourhood income quintile).

We also did additional analyses that further examined the oldest age groups categorized as 85–89, 90–95 and 95 years and older. We determined independence of residuals from fitted values by examining plots of residuals versus fitted values. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05. We reported marginal means and contrasts with 95% confidence intervals fixed at dementia, age and number of morbidities categories. We compared differences in means between those with dementia and those without, between adjacent age categories and between adjacent morbidity categories using Wald tests.

Ethics approval

The institutional review boards at the universities of Alberta (Pro00053469) and Calgary (REB16-1575) approved this study and waived the requirement for participants to provide consent because of the large sample size and the retrospective nature of the study. Data were deidentified.

Results

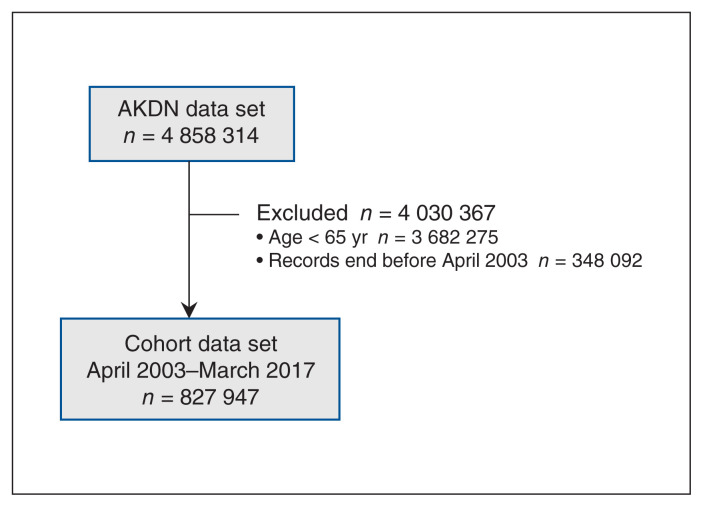

Participant flow is shown in Figure 1. There were 827 947 participants; median follow-up was 6.5 years (range 1 d to 14.0 yr; 2% of participants left the province before the end of follow-up). Twenty-six percent of participants died during follow-up. Participants could contribute follow-up data to more than 1 age category: 661 755 participants were followed while 65–74 years of age, 354 161 while 75–84 years and 158 538 while 85 years and older (Table 1). The percentage of participants with dementia increased with age, from 1.4% to 21.9%. The percentage of participants who were men decreased with age, from 49.8% to 37.3%. More participants living with dementia resided in a low-income neighbourhood than participants without dementia in the group aged 65–74 years, but this difference diminished with increasing age and was absent among those aged 85 years and older. Compared with participants without dementia, participants with dementia consistently had more morbidity across all age groups.

Figure 1:

Participant flow diagram. Note: AKDN = Alberta Kidney Disease Network.

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics at participants’ first year within each age group*

| Characteristic | % of participants; age group and dementia status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age 65–74 yr | Age 75–84 yr | Age ≥ 85 yr | ||||

|

|

|

|

||||

| Dementia n = 9135 |

No dementia n = 652 620 |

Dementia n = 23 747 |

No dementia n = 330 414 |

Dementia n = 34 752 |

No dementia n = 123 786 |

|

| Women | 50.0 | 50.2 | 56.7 | 54.3 | 66.7 | 61.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Men | 50.0 | 49.8 | 43.3 | 45.7 | 33.3 | 38.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Rural | 11.6 | 13.1 | 10.9 | 12.6 | 10.3 | 11.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Lowest SES neighbourhood quintile | 25.8 | 18.3 | 23.5 | 20.0 | 22.7 | 22.8 |

|

| ||||||

| No. of nondementia morbidities | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 4.7 | 24.0 | 3.7 | 12.8 | 2.4 | 11.2 |

|

| ||||||

| 1 | 10.0 | 25.0 | 8.8 | 17.6 | 6.7 | 10.9 |

|

| ||||||

| 2 | 13.4 | 20.5 | 13.1 | 20.2 | 11.8 | 16.1 |

|

| ||||||

| 3 | 15.5 | 14.0 | 15.5 | 18.0 | 15.8 | 17.8 |

|

| ||||||

| ≥ 4 | 56.3 | 16.5 | 59.0 | 31.4 | 63.3 | 44.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | 64.8 | 50.6 | 73.5 | 67.7 | 79.0 | 74.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 39.2 | 21.8 | 50.7 | 40.0 | 66.3 | 56.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Diabetes | 32.0 | 17.8 | 30.4 | 21.6 | 25.5 | 19.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 34.3 | 14.2 | 34.8 | 21.3 | 34.4 | 25.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Chronic pain | 18.5 | 14.7 | 17.1 | 16.8 | 15.0 | 16.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypothyroidism | 17.9 | 11.3 | 20.8 | 15.5 | 24.8 | 19.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Stroke or TIA | 31.1 | 7.1 | 35.0 | 13.7 | 38.2 | 21.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Gout | 10.6 | 8.6 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 13.7 | 13.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Chronic heart failure | 20.1 | 4.9 | 27.0 | 11.7 | 35.2 | 22.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 12.1 | 4.5 | 19.9 | 11.0 | 26.8 | 18.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Depression | 33.6 | 7.0 | 27.1 | 6.5 | 21.2 | 6.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Cancer, nonmetastatic | 5.6 | 4.5 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Myocardial infarction | 5.6 | 3.3 | 7.1 | 5.1 | 7.9 | 6.5 |

|

| ||||||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5.4 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 4.2 | 6.3 | 5.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Asthma | 6.5 | 2.7 | 5.6 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 4.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Alcohol misuse | 19.5 | 2.4 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 4.2 | 1.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5.4 | 1.5 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 3.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 4.1 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 3.1 | 2.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Cancer, metastatic | 3.2 | 1.5 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 2.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Parkinson disease | 10.4 | 0.7 | 11.4 | 1.7 | 9.3 | 2.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Constipation, severe | 5.1 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 3.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Epilepsy | 11.8 | 1.3 | 5.9 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 1.2 |

|

| ||||||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 15.6 | 0.8 | 7.0 | 0.5 | 3.5 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Psoriasis | 1.7 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

|

| ||||||

| Cancer, lymphoma | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Multiple sclerosis | 4.1 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Cirrhosis | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Chronic viral hepatitis B | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Note: SES = socioeconomic status, TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Many participants have data within multiple age groups.

Marginal annual mean costs

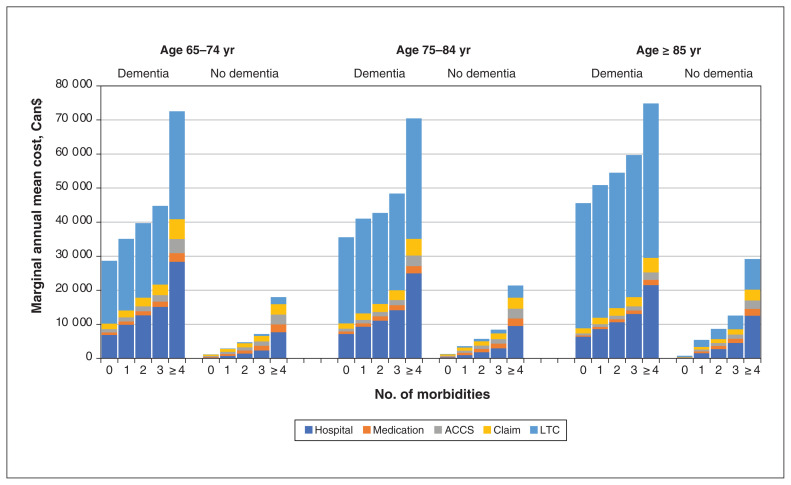

Total costs over the whole cohort were distributed as follows: 33% LTC utilization, 32% hospital admission, 13% provider billing, 11% ambulatory or emergency care and 10% medications. Total marginal annual mean costs and the individual component costs were higher in almost all age categories and number of morbidities categories if dementia was present (Appendix 1, Table S1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/3/E577/suppl/DC1; Figure 2). The increases in total costs from dementia ranged from $27 598 to $54 171 within age categories and number of morbidities categories (Table 2). Similarly, mean total costs and the component costs increased in parallel with the number of morbidities, whether dementia was present or not (increases in total costs ranged from $4597 to $10 655 per morbidity). Mean total costs (driven by LTC costs) and LTC costs increased in parallel with age (increases in LTC costs ranged from $115 to $9304 per age category), but there were no consistent trends for other component costs with increasing age (the change in aggregated non-LTC costs ranged from −$7365 to $921 per age category).

Figure 2:

Marginal annual mean costs for dementia by age and number of morbidities among participants aged 65 years and older. Note: ACCS = ambulatory care classification system, LTC = long-term care.

Table 2:

Marginal differences in mean annual costs in participants aged 65 years and older*

| Comparison | Hospital costs (95% CI) | Medical costs (95% CI) | ACCS costs (95% CI) | Claim costs (95% CI) | LTC costs (95% CI) | Total costs (95% CI) | No LTC total costs† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | |||||||

| Age 65−74 yr; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 6661 (4998 to 8325) | 550 (482 to 619) | 667 (550 to 784) | 18 404 (15 892 to 20 916) | 18 404 (15 892 to 20 916) | 27 598 (24 504 to 30 692) | 8960 (7215 to 10 706) |

| 1 | 9194 (7822 to 10 566) | 381 (327 to 435) | 569 (476 to 662) | 20 922 (19 376 to 22 467) | 20 922 (19 376 to 22 467) | 32 253 (30 120 to 34 386) | 11 263 (9792 to 12 733) |

| 2 | 11 275 (9710 to 12 841) | 234 (184 to 285) | 497 (385 to 610) | 21 605 (20 392 to 22 817) | 21 605 (20 392 to 22 817) | 34 868 (32 839 to 36 897) | 13 340 (11 682 to 14 998) |

| 3 | 12 758 (11 764 to 13 751) | 215 (154 to 277) | 579 (448 to 710) | 22 553 (21 474 to 23 632) | 22 553 (21 474 to 23 632) | 37 542 (35 985 to 39 099) | 15 115 (14 007 to 16 222) |

| ≥ 4 | 20 662 (19 972 to 21 352) | 255 (191 to 319) | 1230 (1074 to 1386) | 29 618 (28 969 to 30 267) | 29 618 (28 969 to 30 267) | 54 171 (53 096 to 55 247) | 25 028 (24 199 to 25 858) |

| Age 75−84 yr; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 6849 (5717 to 7981) | 586 (524 to 649) | 513 (449 to 576) | 25 153 (23 109 to 27 197) | 25 153 (23 109 to 27 197) | 34 652 (32 274 to 37 029) | 8979 (7794 to 10 164) |

| 1 | 8310 (7189 to 9432) | 355 (310 to 400) | 354 (293 to 415) | 27 451 (26 262 to 28 641) | 27 451 (26 262 to 28 641) | 37 966 (36 309 to 39 623) | 9921 (8756 to 11 085) |

| 2 | 9308 (8742 to 9875) | 243 (206 to 281) | 322 (263 to 381) | 26 002 (25 163 to 26 841) | 26 002 (25 163 to 26 841) | 37 269 (36 228 to 38 309) | 10 832 (10 214 to 11 451) |

| 3 | 11 164 (10 609 to 11 719) | 113 (76 to 150) | 221 (159 to 282) | 27 322 (26 617 to 28 028) | 27 322 (26 617 to 28 028) | 40 203 (39 279 to 41 127) | 12 601 (11 986 to 13 216) |

| ≥ 4 | 15 460 (15 102 to 15 819) | −93 (−121 to −65) | 233 (159 to 308) | 31 779 (31 387 to 32 171) | 31 779 (31 387 to 32 171) | 49 059 (48 483 to 49 634) | 17 298 (16 868 to 17 728) |

| Age ≥ 85 yr; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 6185 (5180 to 7190) | 357 (306 to 407) | 465 (384 to 546) | 36 414 (33 530 to 39 299) | 36 414 (33 530 to 39 299) | 45 844 (42 579 to 49 110) | 8130 (7019 to 9240) |

| 1 | 7087 (6399 to 7774) | 127 (84 to 169) | 242 (157 to 327) | 36 823 (35 372 to 38 275) | 36 823 (35 372 to 38 275) | 46 393 (44 755 to 48 031) | 8402 (7650 to 9155) |

| 2 | 7881 (7331 to 8431) | −41 (−82 to 0) | 164 (115 to 213) | 36 733 (35 781 to 37 686) | 36 733 (35 781 to 37 686) | 46 785 (45 659 to 47 911) | 8940 (8331 to 9549) |

| 3 | 8496 (8034 to 8958) | −233 (−268 to −199) | 60 (0 to 120) | 37 703 (36 957 to 38 448) | 37 703 (36 957 to 38 448) | 47 977 (47 086 to 48 868) | 9290 (8759 to 9821) |

| ≥ 4 | 8993 (8674 to 9312) | −478 (−504 to −453) | −286 (−343 to −229) | 36 360 (35 966 to 36 754) | 36 360 (35 966 to 36 754) | 46 113 (45 583 to 46 642) | 9236 (8853 to 9620) |

| No. of morbidities | |||||||

| No dementia; age, yr | |||||||

| 65−74 | 4597 (4554 to 4640) | 591 (586 to 596) | 685 (676 to 694) | 688 (682 to 694) | 819 (785 to 853) | 4597 (4554 to 4640) | 3534 (3507 to 3562) |

| 75−84 | 5433 (5374 to 5493) | 527 (521 to 532) | 721 (710 to 732) | 764 (757 to 771) | 1289 (1244 to 1334) | 5433 (5374 to 5493) | 3922 (3890 to 3954) |

| ≥ 85 | 8772 (8562 to 8982) | 480 (472 to 487) | 687 (665 to 708) | 831 (819 to 843) | 2768 (2676 to 2859) | 8772 (8562 to 8982) | 4281 (4225 to 4336) |

| Dementia; age, yr | |||||||

| 65−74 | 10 655 (10 091 to 11 220) | 503 (478 to 527) | 985 (925 to 1045) | 1274 (1226 to 1323) | 3863 (3454 to 4273) | 10 655 (10 091 to 11 220) | 7632 (7249 to 8015) |

| 75−84 | 8250 (7918 to 8582) | 342 (330 to 355) | 725 (696 to 753) | 1029 (1005 to 1054) | 3212 (2921 to 3503) | 8250 (7918 to 8582) | 5934 (5747 to 6122) |

| ≥ 85 | 5817 (5482 to 6152) | 250 (239 to 260) | 501 (482 to 520) | 831 (808 to 854) | 2461 (2125 to 2797) | 5817 (5482 to 6152) | 4332 (4192 to 4472) |

| Age | |||||||

| No dementia; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | −153 (−190 to −116) | −35 (−39 to −31) | −94 (−100 to −88) | −112 (−118 to −106) | 115 (93 to 136) | −153 (−190 to −116) | −172 (−188 to −156) |

| 1 | 798 (739 to 857) | 40 (31 to 50) | −9 (−29 to 11) | 1 (−8 to 10) | 637 (569 to 705) | 798 (739 to 857) | 298 (267 to 328) |

| 2 | 1227 (1163 to 1290) | 37 (28 to 45) | −22 (−33 to −12) | 24 (13 to 34) | 916 (855 to 977) | 1227 (1163 to 1290) | 439 (402 to 475) |

| 3 | 1592 (1516 to 1668) | −17 (−28 to −6) | −34 (−50 to −18) | 36 (23 to 50) | 1177 (1114 to 1240) | 1592 (1516 to 1668) | 543 (495 to 591) |

| ≥ 4 | 3248 (3145 to 3351) | −151 (−163 to −140) | −158 (−186 to −130) | 80 (61 to 98) | 2561 (2495 to 2627) | 3248 (3145 to 3351) | 921 (849 to 994) |

| Dementia; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 6251 (4510 to 7992) | −156 (−204 to −107) | −223 (−311 to −135) | −36 (−148 to 76) | 8373 (6827 to 9919) | 6251 (4510 to 7992) | −857 (−1789 to 75) |

| 1 | 5901 (4898 to 6903) | −167 (−204 to −130) | −215 (−272 to −157) | −61 (−125 to 3) | 8443 (7572 to 9313) | 5901 (4898 to 6903) | −1369 (−2028 to −709) |

| 2 | 5637 (4901 to 6373) | −177 (−209 to −145) | −244 (−308 to −179) | −139 (−205 to −72) | 8799 (8199 to 9399) | 5637 (4901 to 6373) | −2011 (−2572 to −1450) |

| 3 | 5181 (4539 to 5823) | −342 (−377 to −306) | −339 (−413 to −265) | −179 (−237 to −120) | 9304 (8806 to 9802) | 5181 (4539 to 5823) | −3044 (−3574 to −2514) |

| ≥ 4 | −842 (−1286 to −398) | −609 (−644 to −575) | −1087 (−1177 to −998) | −817 (−874 to −760) | 7401 (7081 to 7721) | −842 (−1286 to −398) | −7365 (−7743 to −6987) |

Note: ACCS = ambulatory care classification system, CI = confidence interval, LTC = long-term care.

Marginal differences in mean annual costs (in Can$1000 units) are reported for the following comparisons: dementia versus no dementia by age and number of morbidities categories; increases in the number of morbidities by dementia and age categories; and increases in age category by dementia and number of morbidities categories. These models include 3-way and 2-way interactions terms for dementia, age and number of morbidities. All costs are inflated to 2017 costs using the Consumer Price Index for all items in Canada. Unshaded cells show significant increases in costs or nonsignificant differences, shaded cells show significant decreases in cost and italics indicate nonsignificant differences.

Includes costs of hospital admissions, medications, ACCS and provider claims.

Among people without dementia, mean annual costs for medications, ACCS charges and claims increased for most number of morbidities categories, from 65–74 years of age to 75–84 years of age (range from −$84 to $76, from −$28 to $23 and from −$44 to $155, respectively) and then decreased from 75–84 years of age to 85 years of age (range from −$227 to −$76, from −$381 to −$99 and from −$264 to −$46, respectively) (Appendix 1, Table S2, Figure S1). Hospital admissions and LTC costs increased in parallel with age (range from −$153 to $3248 and from $115 to $2561 per age category, respectively; Table 2).

In participants with dementia, LTC was the largest component of costs followed by hospital admissions, claims, ACCS charges and medications. Mean costs for LTC and mean total costs (driven by LTC costs) increased with age among participants with dementia (increases in LTC costs ranged from $7401 to $9304 per age category) (Table 2, Figure 2). When LTC costs were excluded, older age was associated with lower costs, and there was an inverse association between hospital admission, medication, ACCS charge and claim costs and increasing age (decreases in non-LTC costs ranged from −$857 to −$7365 per age category).

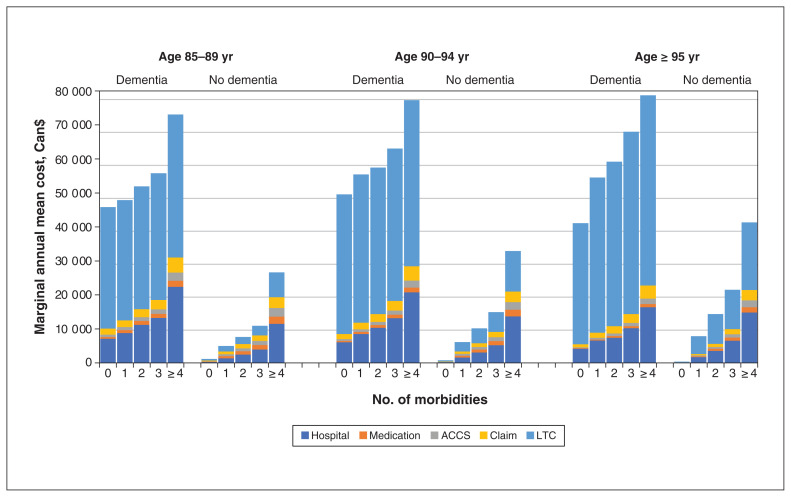

In a sensitivity analysis, we further divided participants aged 85 years and older into the following categories: 85–89 years, 90–94 years and 95 years and older. There were 144 134, 69 615 and 23 736 participants contributing follow-up to each age group, respectively. The results were similar to those for the whole study population (Table 3, Figure 3). Dementia was associated with higher mean total costs and component costs, and there was also an association between higher costs and the number of morbidities (Appendix 1, Table S3, Table S4). For people with and without dementia, there was an association between LTC costs (and thus total costs) and increasing age. However, after LTC costs were excluded, there was evidence of decreasing costs among older participants, with those aged greater than 95 years having the lowest non-LTC costs in most analyses (Table 3; Appendix 1, Figure S2).

Table 3:

Marginal differences in mean annual costs in participants aged 85 years and older*

| Comparisons | Hospital costs (95% CI) | Medical costs (95% CI) | ACCS costs (95% CI) | Claim costs (95% CI) | LTC costs (95% CI) | Total costs (95% CI) | No LTC total costs† (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | |||||||

| Age 85−89 yr; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 6844 (5415 to 8274) | 433 (363 to 503) | 566 (426 to 706) | 1541 (1294 to 1788) | 35 266 (32 286 to 38 245) | 44 541 (41 255 to 47 828) | 9179 (7602 to 10 756) |

| 1 | 7423 (6545 to 8301) | 235 (180 to 290) | 326 (255 to 396) | 1160 (1067 to 1253) | 33 811 (32 214 to 35 409) | 43 227 (41 391 to 45 063) | 9035 (8076 to 9994) |

| 2 | 8785 (7953 to 9617) | 113 (56 to 171) | 234 (163 to 304) | 1128 (1021 to 1235) | 34 041 (32 938 to 35 144) | 44 368 (42 997 to 45 738) | 10 257 (9328 to 11 185) |

| 3 | 9276 (8670 to 9881) | −110 (−154 to −67) | 117 (42 to 192) | 1133 (1055 to 1210) | 34 501 (33 622 to 35 379) | 45 003 (43 925 to 46 081) | 10 379 (9691 to 11 067) |

| ≥ 4 | 10 911 (10 492 to 11 330) | −331 (−363 to −299) | −154 (−229 to −80) | 1248 (1182 to 1313) | 34 765 (34 302 to 35 227) | 46 632 (45 957 to 47 306) | 11 616 (11 117 to 12 115) |

| Age 90−94 yr; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 5913 (4165 to 7662) | 366 (285 to 447) | 410 (317 to 503) | 1400 (1214 to 1586) | 40 677 (36 634 to 44 720) | 49 096 (44 640 to 53 551) | 7882 (5970 to 9794) |

| 1 | 6924 (5924 to 7924) | 120 (45 to 195) | 172 (−139 to 482) | 1300 (1176 to 1425) | 40 766 (38 643 to 42 888) | 49 387 (47 101 to 51 673) | 8386 (7205 to 9566) |

| 2 | 7301 (6519 to 8082) | −92 (−153 to −30) | 195 (123 to 267) | 1181 (1082 to 1281) | 38 713 (37 276 to 40 150) | 47 335 (45 701 to 48 968) | 8505 (7620 to 9389) |

| 3 | 7940 (7121 to 8759) | −217 (−275 to −160) | 120 (8 to 233) | 1254 (1133 to 1374) | 39 005 (37 852 to 40 158) | 48 070 (46 639 to 49 501) | 9094 (8132 to 10 057) |

| ≥ 4 | 7057 (6518 to 7596) | −510 (−550 to −469) | −222 (−307 to −138) | 1093 (1010 to 1175) | 36 928 (36 304 to 37 552) | 44 195 (43 333 to 45 058) | 7411 (6770 to 8052) |

| Age ≥ 95; no. of morbidities | |||||||

| 0 | 4094 (2396 to 5792) | 162 (85 to 239) | 234 (165 to 303) | 886 (687 to 1086) | 35 352 (28 387 to 42 316) | 40 587 (32 891 to 48 283) | 5277 (3430 to 7124) |

| 1 | 4941 (2659 to 7223) | 24 (−34 to 82) | 224 (127 to 321) | 1052 (884 to 1221) | 40 449 (36 071 to 44 828) | 46 854 (41 693 to 52 015) | 5979 (3560 to 8398) |

| 2 | 3858 (2725 to 4991) | −116 (−189 to −43) | 178 (44 to 312) | 1238 (1062 to 1414) | 39 631 (36 811 to 42 451) | 44 579 (41 358 to 47 800) | 5080 (3780 to 6381) |

| 3 | 3676 (2428 to 4923) | −350 (−445 to −254) | 29 (−95 to 153) | 1071 (869 to 1273) | 42 057 (39 840 to 44 273) | 46 305 (43 677 to 48 934) | 4365 (2889 to 5840) |

| ≥ 4 | 1549 (572 to 2526) | −600 (−671 to −529) | −422 (−565 to −279) | 812 (635 to 988) | 36 050 (34 761 to 37 339) | 36 977 (35 248 to 38 705) | 1359 (163 to 2555) |

| No. of morbidities | |||||||

| No dementia; age, yr | |||||||

| 85−89 | 5163 (5012 to 5314) | 596 (582 to 610) | 816 (790 to 842) | 926 (906 to 946) | 2839 (2696 to 2982) | 9128 (8893 to 9362) | 6877 (6717 to 7037) |

| 90−94 | 6229 (5969 to 6489) | 587 (565 to 610) | 721 (623 to 818) | 980 (948 to 1011) | 4502 (4264 to 4741) | 11 056 (10 605 to 11 507) | 7653 (7310 to 996) |

| ≥ 95 | 7319 (6768 to 7869) | 626 (590 to 662) | 832 (761 to 904) | 1088 (1019 to 1157) | 8432 (7944 to 8921) | 12 660 (11 759 to 13 561) | 8086 (7453 to 8718) |

| Dementia; age, yr | |||||||

| 85−89 | 5338 (5030 to 5647) | 359 (340 to 379) | 612 (575 to 649) | 952 (910 to 994) | 2451 (2071 to 2830) | 9347 (8857 to 9838) | 7362 (6996 to 7728) |

| 90−94 | 4903 (4566 to 5241) | 310 (288 to 332) | 529 (493 to 564) | 888 (846 to 930) | 2279 (1799 to 2759) | 8501 (7927 to 9076) | 6725 (6311 to 7139) |

| ≥ 95 | 4076 (3502 to 4651) | 271 (242 to 300) | 437 (385 to 488) | 852 (783 to 921) | 3752 (2900 to 4604) | 8394 (7515 to 9274) | 5371 (4709 to 6033) |

| Age | |||||||

| No dementia | |||||||

| 0 | −112 (−161 to −63) | −84 (−97 to −71) | −103 (−121 to −85) | −145 (−164 to −127) | −114 (−201 to −27) | −298 (−445 to −151) | −349 (−439 to −258) |

| 1 | 169 (6 to 333) | −160 (−190 to −131) | −76 (−222 to 71) | −161 (−193 to −128) | 1392 (1059 to 1725) | 1447 (1035 to 1858) | −70 (−330 to 190) |

| 2 | 556 (354 to 758) | −148 (−178 to −118) | −153 (−190 to −116) | −133 (−167 to −99) | 2504 (2172 to 2837) | 2773 (2359 to 3187) | 196 (−51 to 444) |

| 3 | 1217 (962 to 1473) | −132 (−167 to −97) | −122 (−167 to −77) | −39 (−85 to 7) | 3283 (2942 to 3625) | 4253 (3786 to 4720) | 966 (657 to 1275) |

| ≥ 4 | 1857 (1593 to 2120) | −215 (−241 to −189) | −289 (−345 to −234) | −53 (−101 to −5) | 4998 (4717 to 5280) | 6427 (5990 to 6864) | 1347 (1019 to 1675) |

| Dementia | |||||||

| 0 | −1507 (−2902 to −112) | −197 (−276 to −118) | −267 (−388 to −146) | −381 (−575 to −187) | 847 (−2614 to 4309) | 1265 (−1664 to 4194) | −1982 (−3466 to −498) |

| 1 | −917 (−2077 to 243) | −310 (−362 to −258) | −186 (−252 to −120) | −156 (−245 to −68) | 5788 (3825 to 7750) | 5207 (3316 to 7097) | −1354 (−2599 to −108) |

| 2 | −1776 (−2538 to −1014) | −337 (−390 to −285) | −182 (−252 to −113) | −75 (−164 to 15) | 6277 (5040 to 7513) | 4632 (3384 to 5880) | −2297 (−3127 to −1466) |

| 3 | −1174 (−1783 to −566) | −292 (−332 to −253) | −155 (−227 to −83) | −36 (−115 to 42) | 7946 (7024 to 8868) | 6457 (5494 to 7420) | −1684 (−2390 to −979) |

| ≥ 4 | −2700 (−3099 to −2302) | −410 (−438 to −382) | −408 (−466 to −351) | −268 (−331 to −204) | 6978 (6511 to 7445) | 3409 (2845 to 3973) | −3874 (−4357 to −3391) |

Note: ACCS = ambulatory care classification system, CI = confidence interval, LTC = long-term care.

Marginal differences in mean annual costs (in Can$1000 units) are reported for the following comparisons: dementia versus no dementia by age and number of morbidities categories; increases in the number of morbidities by dementia and age categories; and increases in age category by dementia and number of morbidities categories. These models include 3-way and 2-way interactions terms for dementia, age and number of morbidities. All costs are inflated to 2017 costs using the Consumer Price Index for all items in Canada. Unshaded cells show significant increases in costs or nonsignificant differences, shaded cells show significant decreases in cost and italics indicate nonsignificant differences.

Includes costs of hospital admissions, medications, ACCS and provider claims.

Figure 3:

Marginal annual mean costs for dementia by age and number of morbidities among participants aged 85 years and older. Note: ACCS = ambulatory care classification system, LTC = long-term care.

Inspection of the burden of morbidity among the oldest participants (data not shown) demonstrated that morbidity was infrequent among those without dementia. For example, among participants aged greater than 95 years and without dementia, 56% of the participant-years were lived with 0 or 1 morbidity.

Interpretation

In this population-based study of more than 800 000 older adults treated in a universal health system, we found strong graded associations between multimorbidity, dementia and total health care costs. Older age was associated with significant increases in mean annual health care costs, driven by a strong association between older age and LTC utilization. As expected, dementia was associated with high health care costs that were driven by high utilization of LTC.

After LTC costs were excluded, the presence of dementia appeared to modify the relation between age and costs, such that older age was associated with increased non-LTC costs among those without dementia, but not necessarily among those with dementia. In fact, when LTC resource use was excluded, there was evidence that older age was associated with lower mean annual costs among people with dementia, including lower costs for hospital admissions, medications and ambulatory care.

These findings provide insight into how health care costs may change over time in parallel with the anticipated aging of the general population and therefore which interventions should be given the highest priority to mitigate the consequences of this demographic shift. First, to the extent that the costs associated with multimorbidity and with dementia were higher among people of older age, an increased prevalence of these conditions will exaggerate the economic consequences of the aging population, whereas interventions that prevent these conditions (or reduce their severity) will have the opposite effect. Second, since LTC is such an important driver of health care resource use, providing additional supports to enable older people to live independently rather than enter long-term care would probably yield economic benefits as well as improve quality of life. This may prove more difficult for adults with dementia and for those with physical morbidities. Third, we do not have data that directly explain the inverse association between costs and age among people with dementia once LTC costs were excluded. One possibility is survivorship effects, where those who survive to advanced age despite having dementia may have less morbidity and thus require less costly care. An alternative (not mutually exclusive) possibility is that provider attitudes or patient preferences mean that the care provided to people with dementia is less aggressive than that provided to those without dementia, leading to lower individual costs associated with hospital admissions, medications, emergency care and provider claims. Costs associated with acute care for older people with dementia might be reduced further if LTC homes enhance their ability to provide services that are currently restricted to hospitals, which would in turn require additional training and resources. The ongoing reviews of LTC that have been triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic may offer an opportunity to consider these issues in detail.18

Previous studies and a high-quality systematic review have demonstrated that multimorbidity (with or without dementia) is correlated with higher health care costs.7,19–23 Prior work also demonstrates that dementia is associated with increased costs, especially those due to hospital admission.6,24 However, most such studies have not been able to assess LTC utilization, which is an important contributor to total costs in older people (representing 33% of all health care costs in our cohort). Some prior studies have examined how multimorbidity is associated with a broad range of health care costs, including LTC and other forms of social care.25,26 Most of these studies have reached conclusions similar to ours but have not explored the intersection between dementia, multimorbidity and costs as we were able to do. We also assessed a broader range of morbidities than most prior studies of costs and dementia (or costs and multimorbidity), many of which focus on highly prevalent conditions such as vascular disease and diabetes.23 An exception is the 2012 Symphony study from the United Kingdom, which assessed the intersection between age, dementia and a broad panel of morbidities in a smaller population (1026 participants with dementia).27 Our findings are generally consistent with those of the Symphony study, which also showed that multimorbidity and dementia are more strongly correlated with cost than is age by itself.

Overall, the available evidence suggests that accurately projecting the economic consequences of the aging population is a complicated task and the interplay between morbidity and dementia as well as increasing age must be taken into account.

To gain additional insights about how the aging population may influence health care costs, future studies should combine the projected population structure in the coming decades with data examining the interplay between age, multimorbidity, dementia and costs, such as the findings presented herein. A more detailed examination of which conditions (or which clusters of conditions) account for most multimorbidity-related costs would probably improve the precision of these future studies. Out-of-pocket costs and opportunity costs (for unpaid labour) borne by caregivers and families should also be captured by such studies, since they probably account for a substantial proportion of the total economic burden associated with dementia. Finally, new methods for preventing dementia, attenuating multimorbidity and promoting independent living among older adults should be an extremely high priority for future research.

Our study has important strengths, including its rigorous analytical methods, our use of validated algorithms for ascertaining the presence of dementia and morbidity, and the large, geographically defined cohort.

Limitations

Our study has limitations that should be considered. Studies using administrative data will underestimate the true prevalence of dementia and other morbidities compared with those that use data acquired with a gold standard method such as a structured interview; because health care utilization increases with age, our focus on people aged 65 years and older should reduce the extent of such underestimation. The validated algorithm that we used to classify participants with dementia has a positive predictive value of 93% and a sensitivity of 67%.13 Therefore, our analysis will have misclassified some participants with respect to dementia. To the extent that such misclassification may have been random rather than systematic, this should have tended to bias our findings toward the null and thus should not have affected the observed associations between age, dementia and costs. Although we were able to extend further studies by including LTC utilization, we were not able to capture costs from outside the health sector, such as those associated with unpaid care (a major contributor to the societal costs of dementia28) or private sector care, and out-of-pocket costs for patients and families.29 The exact per-person cost of LTC was not available as we had access only to the average per diem cost; costs for patients with greater care requirements such as those with dementia were probably underestimated (and overestimated for those with lower care needs).

We did not have information on functional status, frailty, disabilities or the severity of morbidities, and thus we relied on the total count of morbidities, which is relatively crude, albeit independently associated with a broad range of clinical outcomes.2 More severe morbidity for a given morbidity count would be expected to increase the likelihood of LTC, which might in turn affect costs. Random misclassification of morbidity would be expected to bias toward the null without affecting our conclusions. However, if the clinical consequences of individual morbidities or morbidity count actually vary by age or dementia status, this may have affected our results, and this possibility requires further investigation. Finally, we studied people from a single Canadian province with data available only until March 2017; thus, our findings may not apply to other settings.

Conclusion

Multimorbidity and dementia were associated with higher mean annual health care costs. As expected, older age was associated with increased use of LTC and thus health care costs among people with and without dementia, and dementia was associated with substantially increased utilization of LTC. However, whereas older age was associated with higher costs of hospital admission, medications, acute care and provider claims among those without dementia, the converse was true among those with dementia, for whom there was an inverse association between older age and total costs once costs attributable to LTC were excluded. These findings suggest that the task of projecting the economic consequences of the aging population is complicated and must account for the interplay between morbidity and dementia as well as increasing age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Ghenette Houston provided administrative support and Sophanny Tiv provided technical support at the University of Alberta.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Matthew James has received investigator-initiated grant funding from Amgen Canada. Scott Klarenbach is director of the Alberta Real World Evidence Consortium (University of Alberta, University of Calgary and Institute of Health Economics), which conducts investigator-initiated, industry-funded research unrelated to this work. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Marcello Tonelli and Scott Klarenbach conceived the study. Marcello Tonelli, Natasha Wiebe and Scott Klarenbach designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Natasha Wiebe performed the statistical analyses. All authors made substantial contributions to developing the manuscript and revising it for important intellectual content, and all approved the final version. All authors agreed to act as guarantors for the work.

Funding: This research was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant (FRN 143211) and a Leaders Opportunity Fund grant from the Canada Foundation for Innovation to Marcello Tonelli. Marcello Tonelli was supported by the University of Calgary’s David Freeze Chair in Health Research. Sharon Straus holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation and Quality of Care. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data sharing: The authors are not able to make their data set available to other researchers because of their contractual arrangements with the provincial health ministry (Alberta Health), which is the data custodian. Researchers may make requests to obtain a similar data set at https://sporresources.researchalberta.ca.

Disclaimer: This study is based in part on data provided by Alberta Health and Alberta Health Services. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein are those of the researchers and do not represent the views of the Government of Alberta or Alberta Health Services. Neither the Government of Alberta nor Alberta Health or Alberta Health Services express any opinion in relation to this study.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/3/E577/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, et al. Multimorbidity is common to family practice. Is it commonly researched? Can Fam Physician. 2005;51:244–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380:37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fortin M, Hudon C, Haggerty J, et al. Prevalence estimates of multimorbidity: a comparative study of two sources. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:111. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehnert T, Heider D, Leicht H, et al. Review: health care utilization and costs of elderly persons with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68:387–420. doi: 10.1177/1077558711399580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perruccio AV, Katz JN, Losina E. Health burden in chronic disease: multimorbidity is associated with self-rated health more than medical comorbidity alone. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaczynski A, Michalowsky B, Eichler T, et al. Comorbidity in dementia diseases and associated health care resources utilization and cost. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;68:635–46. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang L, Si L, Cocker F, et al. A systematic review of cost-of-illness studies of multimorbidity. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2018;16:15–29. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha SK. Living longer, living well: report submitted to the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care and the minister responsible for seniors on recommendations to inform a seniors strategy for Ontario. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Ministry of Long-Term Care; 2012. [accessed 2020 Oct. 15]. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/seniors_strategy/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Living in a long-term care home. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Ministry of Long-Term Care; 2017. [accessed 2020 Oct. 15]. Available: health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ltc/glossary.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmelgarn BR, Clement F, Manns BJ, et al. Overview of the Alberta Kidney Disease Network. BMC Nephrol. 2009;10:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-10-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Martin F, et al. Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Methods for identifying 30 chronic conditions: application to administrative data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:31. doi: 10.1186/s12911-015-0155-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quan H, Li B, Saunders LD, et al. Assessing validity of ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data in recording clinical conditions in a unique dually coded database. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:1424–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh JA. Veterans Affairs databases are accurate for gout-related health care utilization: a validation study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R224. doi: 10.1186/ar4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens PE, Levin A Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Chronic Kidney Disease Guideline Development Work Group Members. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:825–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Understanding variability in the cost of a standard hospital stay. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information;; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics: methods and applications. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ontario ombudsman to investigate government’s oversight of long-term care homes during pandemic [press release] Toronto: Office of the Ombudsman of Ontario; 2020. Jun 1, [accessed 2020 Oct. 15]. Available: www.ombudsman.on.ca/resources/news/press-releases/2020/ontario-ombudsman-to-investigate-government's-oversight-of-long-term-care-homes-during-pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zulman DM, Pal Chee C, Wagner TH, et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare utilisation among high-cost patients in the US Veterans Affairs Health Care System. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007771. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bähler C, Huber CA, Brüngger B, et al. Multimorbidity, health care utilization and costs in an elderly community-dwelling population: a claims data based observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-0698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brilleman SL, Purdy S, Salisbury C, et al. Implications of comorbidity for primary care costs in the UK: a retrospective observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:e274–82. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X665242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Griffith LE, Gruneir A, Fisher K, et al. Patterns of health service use in community living older adults with dementia and comorbid conditions: a population-based retrospective cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:177. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0351-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith LE, Gruneir A, Fisher K, et al. Insights on multimorbidity and associated health service use and costs from three population-based studies of older adults in Ontario with diabetes, dementia and stroke. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:313. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4149-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu CW, Cosentino S, Ornstein K, et al. Use and cost of hospitalization in dementia: longitudinal results from a community-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30:833–41. doi: 10.1002/gps.4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stafford M, Deeny Sr, Dreyer K, et al. Multimorbidity within households and health and social care utilisation and cost: retrospective cohort study using administrative data. medRxiv. 2020 Mar 23; doi: 10.1101/2020.03.20.20022335.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Picco L, Achilla E, Abdin E, et al. Economic burden of multimorbidity among older adults: impact on healthcare and societal costs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:173. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1421-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasteridis P, Street AD, Dolman M, et al. The importance of multimorbidity in explaining utilisation and costs across health and social care settings: evidence from South Somerset’s Symphony Project [working paper] York (UK): Centre for Health Economics, University of York; 2014. [accessed 2020 Oct. 15]. Available: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/136185/1/CHERP96_multimorbidity_utilisation_costs_health_social_care.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.El-Hayek YH, Wiley RE, Khoury CP, et al. Tip of the iceberg: assessing the global socioeconomic costs of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias and strategic implications for stakeholders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70:323–41. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McPhail SM. Multimorbidity in chronic disease: impact on health care resources and costs. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2016;9:143–56. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S97248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.