Abstract

Electrorotation is a noninvasive technique that is capable of detecting changes in the morphology and physicochemical properties of microorganisms. Electrorotation studies are reported for two intestinal parasites, Giardia intestinalis and Cyclospora cayetanensis. It is concluded that viable and nonviable G. intestinalis cysts can be differentiated by this technique, and support for this conclusion was obtained using a fluorogenic vital dye assay and morphological indicators. The viability of C. cayetanensis oocysts (for which no vital dye assay is currently available) can also be determined by electrorotation, as can their sporulation state. Modeling of the electrorotational response of these organisms was used to determine their dielectric properties and to gain an insight into the changes occurring within them. Electrorotation offers a new, simple, and rapid method for determining the viability of parasites in potable water and food products and as such has important healthcare implications.

Parasitism has a significant impact worldwide, both economically and in terms of human suffering. The environmental route of transmission (water, soil, or food) is important for many protozoan parasites. Increased demands made on natural resources increase the likelihood of encountering environments and food products contaminated with parasites. The development of new generic methods for simply and rapidly determining the viability of such parasites is therefore of importance.

Electrorotation is a new technique, in terms of its application to the study of microorganisms. During electrorotation, particles are subjected to a uniform rotating electric field that causes the particles to rotate (3, 20). The induced rotation of the particle is a sensitive function of the particle's dielectric properties, namely, the conductivity and permittivity of the organism's constituent components. These components include the wall (if present), the plasma membrane, and the cytoplasm. The rotation is also a function of the conductivity and permittivity of the suspending medium. Electrorotation has been successfully used to investigate the viability of oocysts of the protozoan Cryptosporidium parvum (12), and preliminary studies have been reported for oocysts of one human isolate of Cyclospora cayetanensis (8). Using an improved electrode design, we have investigated the electrorotational response of Giardia intestinalis cysts and have advanced our knowledge of the electrorotational response of oocysts of C. cayetanensis.

The flagellate G. intestinalis is the most frequently detected protozoan parasite in fecal samples from humans (11). Although an infected human can excrete up to 1010 cysts per day, the infective dose is low, between 25 and 100 cysts (26). In assessing water quality it is important not only to detect and identify cysts in low concentrations but also to determine their viability and therefore their potential for causing infection. Current methods for determining cyst viability include in vivo testing (27), in vitro excystation, vital dyes (32), phase-contrast microscopy (29), and heat shock mRNA analysis (1). In vivo methods are expensive, and while they give information about populations of cysts, none is obtained about individual cysts in a population, which is important when calculating the risk from parasites with low infectious doses. The in vitro methods are all lengthy procedures and/or subject to inaccuracies; for example, nonstaining was reported for one of four human isolates of G. duodenalis cysts tested (32), and excystation cannot be used for determining the viability of individual or small numbers of cysts (5). Smith (34) suggested that propidium iodide (PI) inclusion or exclusion and morphological assessment according to Schupp and Erlandsen (29) was the most suitable method for determining G. intestinalis cyst viability. Thompson and Boreham (36) also concluded that this was the most satisfactory way to proceed. We show that electrorotation can be used to determine the viability of G. intestinalis cysts, a conclusion supported using a combination of a vital dye and morphological indicators.

C. cayetanensis is a recently described protozoan parasite of humans (4, 21) and causes diarrheal illness worldwide. The exact mode of transmission is not yet known, but water- and food-borne routes have been implicated in recent outbreaks (35). The transmissive stage, a spherical oocyst with a diameter of 8 to 10 μm, is voided with the host feces in the unsporulated form. Sporulation occurs after 7 to 12 days of incubation at 25 to 30°C or within 6 months when maintained at 4°C; only sporulated oocysts are infectious. Identification of C. cayetanensis oocysts is through a combination of accurate size measurement, autofluorescence in UV light (450 to 490 nm and 365 nm), and excystation (22). Molecular techniques, for example, PCR, can be used for identification purposes (19), but there are often distinct differences between laboratory and field data (33). No successful viability assays using vital dyes (10) or a suitable animal model have yet been reported for C. cayetanensis oocysts, and while the excystation method provides a means of viability determination, this typically takes between 1 and 2 weeks (21, 22), as the oocysts have to undergo sporulation first.

As the oocysts of C. cayetanensis are resistant to current water treatment procedures, including chlorination (25), and the infective dose is low, probably between 10 and 100 oocysts (2), there is a need for more-rapid viability assays that work at the single-organism level.

Based on our previous C. parvum study (12) and the current G. intestinalis data, we show strong evidence that, in the absence of a vital dye technique, the viability of C. cayetanensis oocysts can be determined by the electrorotation method. We also show that electrorotation can determine the sporulation state of an oocyst, which is important for assessing the potential risk of water contaminated with C. cayetanensis. Finally, we have analyzed the electrorotation response of the particles to determine their dielectric properties using the so-called dielectric multishell model, described elsewhere (18, 38).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cysts of G. intestinalis were obtained from human diarrheic samples provided by the public health laboratories of Gwynedd Hospital, Gwynedd, Wales, United Kingdom. Samples were purified by a water-ether sedimentation protocol followed by a sucrose flotation method (6). Cysts were then immediately washed in deionized water and stored at 4°C for use within 1 month. G. intestinalis cyst viability was determined morphologically by phase-contrast microscopy (29) and according to assays with the fluorogenic vital dye propidium iodide (PI) (30). A 100-μl aliquot of cyst suspension was incubated with 10 μl of PI (0.02 mg ml−1) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4 (10 mM phosphate buffer, 27 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl; Sigma Chemical Co.), for 30 min in a water bath at 37°C. Following the dye procedure the suspensions were washed in deionized water.

Purified C. cayetanensis oocysts were supplied by the Scottish Parasite Diagnostic Laboratory (SPDL) (Glasgow, United Kingdom). Samples were collected from three infected humans (two male, one female) in the Glasgow area who had recently traveled abroad. The samples were purified as for G. intestinalis. Oocysts were then washed in deionized water and stored at 4°C in 2% potassium dichromate solution.

To obtain reproducible electrorotation data, the particles are first washed and resuspended in a solution of well-defined chemical composition and conductivity. To reduce electrical heating effects, the magnitude of the rotating field should also be as low as possible. For the work reported here, PBS of conductivity 1 mS m−1 was used as the suspending medium to achieve easily measurable rotation rates for modest applied voltages in the convenient frequency range of 100 Hz to 10 MHz. The washing procedure (repeated three times) consisted of diluting a 100-μl aliquot of particle suspension in ultrapure water (conductivity, 0.1 mS m−1) to 1.5 ml, vortexing for 30 s, microcentrifuging for 1 min (3,300 × g), and then aspirating to 100 μl. After the final wash, the sample was resuspended in PBS solution which had been diluted with ultrapure water to give a conductivity of 1 mS m−1. The suspending medium conductivity was then checked by testing 200 μl of supernatant following centrifugation using a calibrated Hanna Instruments Pure Water Tester, modified to reduce the volume of the sample chamber. Working particle density concentrations were 3 × 104 cysts ml−1 for G. intestinalis and 5 × 103 oocysts ml−1 for C. cayetanensis.

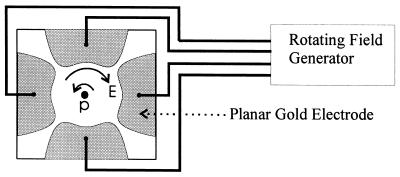

Descriptions of the basic theory and experimental procedures of electrorotation are given elsewhere (13, 16). In brief, 20 μl of (oo)cyst suspension was pipetted into a chamber surrounded by four planar gold electrodes, as shown in Fig. 1. The so-called “bone” electrode design is described by a 4th-order polynomial and is optimized to create a uniform rotating electric field over as large an area as possible in the center of the chamber. The shape and magnitude of the spectra obtained are known to be affected by the particle position in the chamber and by the presence of debris on the particle surface (8). Particles were therefore excluded from analysis if they were positioned outside the middle third of the chamber, drifted more than three times their own diameter during the recording, or possessed debris on their surface. These careful selection criteria, coupled with an electrode design that minimizes particle drift, improved the proportion of oocysts from which data could be obtained.

FIG. 1.

A particle (p) suspended between four electrodes and subjected to a rotating electric field (E) (3, 13, 16, 20). Depending on the dielectric properties of the particle and the electrical frequency, the particle will rotate in either the same direction (cofield) or in the opposite direction (antifield) as the rotating field. Antifield rotation is depicted in this figure. The distance between opposing electrode faces was 2 mm.

Particle identification and motion in the electric field were visualized using phase-contrast microscopy with a total magnification of ×400 (Nikon Optiphot-2 microscope with JVC model TK-1280E color video camera attachment) and recorded by video for later analysis and timing by stopwatch. A minimum of 10 s of behavior was recorded at each of 20, approximately equidistant, applied frequency points on a log scale over the range of 100 Hz to 10 MHz. After each aliquot had been examined and spectra had been recorded, the chamber was washed under pressure with ultrapure water from a wash bottle and dried under a stream of nitrogen gas.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

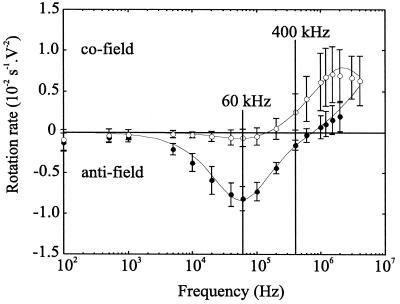

The electrorotation spectra obtained from 27 G. intestinalis cysts, identified as possessing intact cyst walls with no debris adhering to the surface, are shown in Fig. 2. The spectra are grouped according to viability. It is clear that viable and nonviable cysts exhibit markedly different electrorotation behavior. Spectrum profiles are in good agreement to those previously reported for the viability of isolated animal cells (14), biocide-treated yeast cells (Saccharomyces cerevisiae RXII) (37), and C. parvum oocysts (12).

FIG. 2.

Electrorotation spectra of G. intestinalis cysts at a suspending medium conductivity of 1 mS m−1 grouped according to inclusion or exclusion of the vital dye PI and morphology. Symbols show mean rotation rates and error bars indicate 1 standard deviation for n = 8 viable (solid symbols) and n = 19 nonviable cysts (open symbols). Solid lines show the best fits from the multishell model using the values listed in Table 1.

Within the applied frequency range there is a frequency window, centered around 400 kHz, within which viable and nonviable cysts rotate in opposite directions. The terms “cofield” and “antifield” denote the sense of rotation of the particles relative to that of the applied field. At 400 kHz, cofield rotation thus characterizes nonviable cysts while antifield rotation characterizes viable cysts. The rotation direction, observed through a light microscope, is easily determined after a few seconds of observation and is aided by the ellipsoidal shape of the cysts. An alternative method of distinguishing the particle viability through electrorotation is by noting the significant difference in the magnitude of the antifield rotation peak. For these cysts (in a suspending medium of 1 mS m−1), the peak antifield rotation, or characteristic frequency, is found at approximately 60 kHz. Although the greatest difference in rotational velocity for viable and nonviable cysts occurs at this frequency, determination of the viability of cysts by electrorotation alone requires accurate measurement of the rotational velocity and knowledge of the field strength. Automated image processing techniques that measure the rotational direction and velocity of particles have been demonstrated by several groups (9, 28, 38).

Modeling of the experimental data for G. intestinalis (Fig. 2) using an ellipsoidal two-shell model (37) allowed values of the electrical parameters of the different cell components to be estimated (Table 1). The most significant differences between viable and nonviable cysts are an increase in the membrane conductivity with a corresponding decrease in the interior conductivity. These findings are consistent with nonviable cysts having an impaired plasma membrane which allows ions to be exchanged more freely with the external media. This is also consistent with the response of PI dye, which only stains nonviable cysts as it cannot traverse intact biological membranes (17).

TABLE 1.

Particle dimensions and dielectric parameter values used in the modeling of electrorotation spectra

| Parameter |

Giardiaa

|

Cyclospora

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viable | Nonviable | Unsporulated

|

Sporulated

|

|||

| Viable | Nonviable | Viable | Nonviable | |||

| Dimensions (μm) | 9 × 6b | 9 × 6b | 9c | 9c | 9c | —d |

| Wall thickness (nm) | 300e | 300e | 113c | 113c | 113c | — |

| Mean membrane thickness (midpoint ± range)(nm) | 6 ± 0.5 | 6 ± 0.5 | 9 ± 0.5 | 9 ± 0.5 | 9 ± 0.5 | — |

| Permittivity (ɛr) | ||||||

| Interior | 60f | 60f | 50g | 50g | 50g | — |

| Membrane (midpoint ± range) | 6 ± 0.5 | 5 ± 0.5 | 4 ± 0.5 | 4 ± 0.5 | 4 ± 0.5 | — |

| Wall | 60g | 60g | 60g | 60g | 60g | — |

| Mean conductivity (midpoint ± range) (S m−1) | ||||||

| Interior | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.02 ± 0.002 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | — |

| Membrane | 2 × 10−6 ± 0.8 | 1 × 10−5 ± 0.2 | 5.5 × 10−6 ± 0.3 | 1 × 10−5 ± 0.1 | 8 × 10−6 ± 0.5 | — |

| Wall | 0.032 ± 0.002 | 0.05 ± 0.005 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | — |

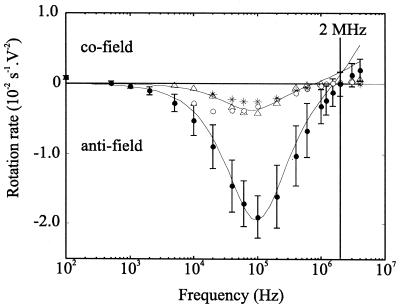

Initial electrorotation spectra for a second particle type of similar size, namely, the spherical oocysts of C. cayetanensis, are shown in Fig. 3. All of the n = 19 oocysts were in an unsporulated state and were morphologically indistinguishable. The spectra recorded, however, were of two distinct types. Similarities between these spectra and those shown in Fig. 2 for G. intestinalis cysts indicate the possibility that the two types of spectra shown in Fig. 3 are those of viable and nonviable oocysts. Discrimination of nonviable and viable C. cayetanensis oocysts by rotation in opposite directions at a specific frequency is not possible, due to overlap between the anti- and cofield crossover points and the very low rates of cofield rotation observed above 2 MHz.

FIG. 3.

Electrorotation spectra of unsporulated C. cayetanensis oocysts at a suspending medium conductivity of 1 mS m−1. The spectra obtained from the n = 19 intact unsporulated oocysts were one of two distinct types. The first type, that characteristic of n = 17 oocysts, is summarized by the solid symbols and error bars representing the mean rotation rate and 1 standard deviation. The open symbols show the rotation rates of the n = 2 oocysts with the second distinct spectra type. Also shown is the electrorotation spectrum for an oocyst without internal contents (∗). Solid lines show the best fit from the multishell model, using values listed in Table 1.

The distinct n = 2 unsporulated intact-walled oocysts have a spectrum comparable to that of an oocyst that had no observable structural contents (Fig. 3) and which was considered nonviable. These spectra are similar over most of the frequency range, indicating that they are of a similar physiological state. The previous report on C. cayetanensis assumed that this type of response was due to a change in viability (8), but this could not be verified. Minor differences between spectra can be attributed to differing states of deterioration following oocyst death. Estimations of the electrical parameters of the different oocyst components for the viable and nonviable best model fits shown in Fig. 3 are listed in Table 1. Trends similar to those of the G. intestinalis cysts are found for the C. cayetanensis oocysts, namely, an increase in membrane conductivity with a corresponding decrease in the interior conductivity, providing further evidence that the change in shape of the spectra is indeed due to differences in physiological state.

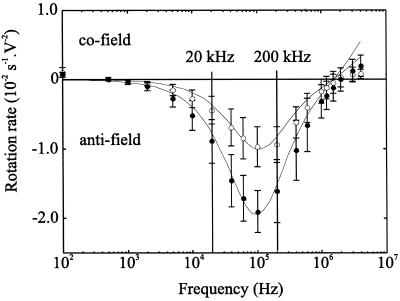

Oocysts of C. cayetanensis were stored at room temperature (approximately 20°C) to induce sporulation. After 14 days, 30% were found to be sporulated. Excystation studies (21) on these sporulated oocysts performed at the SPDL showed that 75% excysted. An electrorotational comparison between unsporulated and sporulated oocysts of C. cayetanensis is shown in Fig. 4. The sporulation state was determined by the presence or absence of two sporocysts with the oocyst wall as identified using phase-contrast microscopy. Significant differences in the spectra are found in the frequency window from 20 to 200 kHz, with a much-reduced rotational velocity for the sporulated oocysts in this range. The previous report, for a single isolate of C. cayetanensis, indicated that at a frequency of 1 MHz, unsporulated and sporulated oocysts rotate in opposite directions (8). Although this previous conclusion was valid for that isolate, this distinction is not possible with mixed isolates. Importantly, however, the distinction based on the rate of rotation in the frequency window mentioned is confirmed. From the multishell model, the change in the spectra upon sporulation can be considered to be primarily associated with a slight increase in oocyst membrane conductivity. It must be noted, however, that whereas the multishell model enables accurate determinations to be made of the dielectric properties of the outermost membrane and wall of the oocysts, at best it can only provide a rough indication of any changes occurring in the properties or level of complexity of internal structures (7). From transmission electron microscopy studies (22), a sporulated oocyst is described as possessing a two-layered oocyst wall (63 and 50 nm thick, respectively) surrounding two sporocysts, each with 62-nm-thick walls surrounding a plasma membrane. Within each sporocyst are two membrane-bound sporozoites. These features may explain the deviation of the fitted lines in Fig. 4 from the experimental observations for C. cayetanensis at the higher frequencies, where the electrorotation properties are regarded as being more sensitive to the internal structure of particles (23).

FIG. 4.

Electrorotation spectra of C. cayetanensis oocysts at a suspending medium conductivity of 1 mS m−1 comparing sporulated and unsporulated intact oocysts. Symbols show mean rotation rates and error bars indicate 1 standard deviation for n = 17 unsporulated (solid symbols) and n = 14 sporulated (open symbols) oocysts. Solid lines show the best fit from the multishell model using values listed in Table 1.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the electrorotation technique can differentiate between viable and nonviable cysts of G. intestinalis. Two simple methods were identified for the rapid determination of cyst viability, the first of which involves only momentary observation of the particle to decide the direction of rotation. The second method involves determining the rotational velocity at a frequency close to the antifield maximum and may be more useful in environmental samples, as this feature is less sensitive to changes in the suspending medium conductivity. In using morphological inspection in conjunction with PI inclusion (36), we consider that our method for determining viability was sufficiently reliable in terms of deciphering the two distinct categories obtained in the electrorotation data.

In the absence of current viability surrogates for small numbers of organisms, we have also demonstrated that electrorotation velocity at the antifield maximum can be used to determine C. cayetanensis oocyst viability. The data presented in this paper for G. intestinalis cysts and from previously published electrorotation data from other protozoans (12), fungi (16), and animal cells (14) support this hypothesis. Indeed, where there is a need to develop viability assays for new pathogens or cells, by probing membrane integrity, electrorotation may provide a simple and rapid solution. Electrorotation also overcomes the problems associated with vital dyes, such as toxicity and the requirement for specialized storage.

The ability to determine the sporulation state of C. cayetanensis oocysts was also demonstrated with electrorotation. This is of importance as only following sporulation are the oocysts potentially infectious. Determining oocyst viability and sporulation state is therefore important in assessing the risk associated with potentially contaminated water. Currently only trained laboratory workers can identify the degree of sporulation, as oocysts of C. cayetanensis do not change their physical size upon sporulation.

Within the known limitations of the multishell model for characterizing bioparticles of complex structure (7), the data (Table 1) indicate that the membrane conductivity of nonviable (oo)cysts is significantly greater than that of viable ones. The corresponding decrease in the internal conductivity of the (oo)cysts confirms that this is associated with a physical degradation of the membrane and the loss of its ability to act as a barrier to passive ion flow. It is also of interest to note from Table 1 that the best fit of the multishell model suggests that the C. cayetanensis membrane is thicker than that for G. intestinalis (9 and 6 nm, respectively). On the assumption that the chemical composition of the membrane remains constant, then the deduced reduction in the relative permittivity of the G. intestinalis membrane from a value of 6 ± 0.5 to 5 ± 0.5 ɛr also suggests that the effective surface area of the membrane is reduced on transition from the viable to nonviable state. A reduction in membrane surface area could correspond to a reduction in the complexity of the surface morphology, such as, for example, a reduction in membrane folding. Alternatively, the membrane polarizability could be reduced through a loss of protein function, for example, by the formation of protein complexes within the lipid bilayer (24).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Swindon, United Kingdom (grant 97/B1/E/03539), and the National Foundation for Cancer Research, Bethesda, Md.

We thank C. A. Paton and J. A. Tame for technical assistance and M. Poole of the Public Health Laboratories, Bangor, United Kingdom, for supplying the G. intestinalis cysts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbaszadegan M, Huber M S, Gerber C P, Pepper I L. Detection of viable Giardia cysts by amplification of heat shock-induced mRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:324–328. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.324-328.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams A, Ortega Y R. Cyclospora. In: Robinson R K, Batt C A, Patel P D, editors. Encyclopaedia of food microbiology. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press Limited; 1999. pp. 502–513. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold W M, Zimmermann U. Rotating-field-induced rotation and measurement of the membrane capacitance of single mesophyll cells of Avena sativa. Z Naturforsch Teil C. 1982;37:908–915. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashford R W. Occurrence of an undescribed coccidian in man in Papua New Guinea. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1979;73:497–500. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1979.11687291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingham A K, Jarroll E L, Meyer E A, Radulescu S. Giardia spp.: physical factors of excystation in vitro and excystation vs. eosin exclusion as determinants of viability. Exp Parasitol. 1979;47:281–291. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(79)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukhari Z, Smith H V. Effect of three concentration techniques on viability of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts recovered from bovine feces. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2592–2595. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2592-2595.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan K L, Gascoyne P R C, Becker F F, Pethig R. Electrorotation of liposomes: verification of dielectric multi-shell model for cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1349:182–196. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00092-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalton C, Pethig R, Paton C A, Smith H V. Electrorotation of oocysts of Cyclospora cayetanensis. Inst Phys Conf Ser. 1999;163:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeGasperis G, Wang X B, Yang J, Becker F F, Gascoyne P R C. Automated electrorotation: dielectric characterisation of living cells by real time motion estimation. Meas Sci Tech. 1998;9:518–529. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberhard M L, Pieniazek N J, Arrowood M J. Laboratory diagnosis of Cyclospora infections. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:792–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farthing M J G, Cevallos A-M, Kelly P. Intestinal protozoa. In: Cook G C, editor. Manson's tropical diseases. 20th ed. London, United Kingdom: W. B. Saunders Ltd.; 1996. pp. 1255–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goater A D, Burt J P H, Pethig R. A combined travelling wave dielectrophoresis and electrorotation device: applied to the concentration and viability of Cryptosporidium. J Phys D Appl Phys. 1997;30:L65–L69. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goater A D, Pethig R. Electrorotation and dielectrophoresis. Parasitology. 1998;117:S177–S189. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099004114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gundel J, Wicher D, Matthies H. Electrorotation as a viability test for isolated single animal cells. Stud Biophys. 1989;133:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hölzel R, Lamprecht I. Dielectric properties of yeast cells as determined by electrorotation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1104:195–200. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90150-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Y, Hölzel R, Pethig R, Wang X-B. Differences in the AC electrodynamics of viable and non-viable yeast cells determined through combined dielectrophoresis and electro-rotation studies. Phys Med Biol. 1992;37:1499–1517. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/37/7/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones K H, Senft J A. An improved method to determine cell viability by simultaneous staining with fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;331:77–79. doi: 10.1177/33.1.2578146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kakutani T, Shibatani S, Sugai M. Electrorotation of nonspherical cells—theory for ellipsoidal cells with an arbitrary number of shells. Bioelectrochem Bioenerg. 1993;31:131–145. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez F A, Manglicmot J, Schmidt T M, Yeh C, Smith H V, Relman D A. Molecular characterisation of Cyclospora-like organisms from Baboons. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:670–679. doi: 10.1086/314645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mischel M, Voss A, Pohl H A. Cellular spin resonance in rotating electric fields. J Biol Phys. 1982;10:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ortega Y R, Sterling C R, Gilman R H, Cama V A, Diaz F. Cyclospora species: a new protozoan pathogen of humans. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1308–1312. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305063281804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortega Y R, Gilman R H, Sterling C R. A new coccidian parasite (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) from humans. J Parasitol. 1994;80:625–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pethig R. Application of A.C. electrical fields to the manipulation and characterisation of cells. In: Karube I, editor. Automation in biotechnology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1991. pp. 159–185. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pethig R, Kell D. The passive electrical properties of biological systems—their significance in physiology, biophysics and biotechnology. Phys Med Biol. 1987;32:933–970. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/32/8/001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabold G, Hoge C W, Shlim D R, Kefford C, Rajah R, Echeverria P. Cyclospora outbreak associated with chlorinated drinking water. Lancet. 1994;344:1360. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90716-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rentdorff R C. The experimental transmission of Giardia lamblia among volunteer subjects. In: Jakubowski W, Hoff J C, editors. Waterborne transmission of giardiasis. U.S. Cincinnati, Ohio: Environmental Protection Agency; 1979. pp. 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts-Thompson I C, Stevens D P, Moahmoud A A F, Warren K S. Giardiasis in the mouse: an animal model. Gastroenterology. 1976;7:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnelle T, Glasser H, Fuhr G. Opto-electronic technique for automatic detection of electrorotational spectra of single cells. Cell Eng. 1997;2:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schupp D C, Erlandsen S L. Determination of G. muris cyst viability by differential interference contrast, phase, or brightfield microscopy. J Parasitol. 1987;73:723–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schupp D C, Erlandsen S L. A new method to determine Giardia cyst viability: correlation of fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide staining with animal infectivity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:704–707. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.704-707.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheffield H G, Bjorvatn B. Ultrastructure of the cysts of Giardia lamblia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1977;26:23–30. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1977.26.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith A L, Smith H V. A comparison of fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide staining and in vitro excystation for determining Giardia intestinalis cyst viability. Parasitology. 1989;99:329–331. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000059035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith H V. Detection of parasites in the environment. Parasitology. 1998;117:S113–S141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith H V. Detection of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in water: current status and future prospects. In: Pickup R W, Saunders J R, editors. Molecular approaches to environmental microbiology. Chichester, United Kingdom: Ellis-Horwood; 1996. pp. 195–225. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterling C R, Ortega Y R. Cyclospora: an enigma worth unravelling. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:48–53. doi: 10.3201/eid0501.990106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson R C A, Boreham P F L. Discussants report: biotic and abiotic transmission. In: Thompson R C A, Reynoldson J A, Lymbery A J, editors. Giardia: from molecules to disease. Oxon, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. pp. 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou X-F, Markx G H, Pethig R. Effect of biocide concentration on electrorotation spectra of yeast cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 1996;1281:60–64. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(96)00015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou X-F, Burt J P H, Pethig R. Automatic cell electrorotation measurements: applied to studies of the biological effects of low-frequency magnetic fields and of heat shock. Phys Med Biol. 1998;43:1075–1090. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/43/5/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]