Dear Editor,

Wang et al. highlighted the importance of enhanced surveillance amongst healthcare workers (HCWs) to prevent nosocomial transmission of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as lifting of lockdowns and safe management measures occurred after the initial COVID-19 wave in 2020.1 The arrival of the Delta variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Singapore led to increased community cases and a cluster at Tan Tock Seng Hospital (TTSH), a 1600-bed acute general hospital co-located with the national COVID-19 referral center (National center of Infectious Diseases) in April 2021.2 Subsequently, TTSH enhanced its measures against COVID-19. These included personal protective equipment (PPE) upgrade for staff, rostered routine testing (RRT) for staff and inpatients, contact tracing and quarantine of exposed contacts – all of which effectively prevented further nosocomial transmission in the hospital.2

On October 11, 2021, the national strategy pivoted from containment to controlled mitigation of COVID-19. Hospital protocols for management of COVID-19 exposures consequently shifted to align with national policies. Unlike the prior protocol, exposed staff contacts were no longer subjected to 14-day quarantines. Instead, they were placed on enhanced surveillance and issued health risk warnings which required a negative antigen rapid test (ART) daily for seven days prior to coming to work.3 Inpatient close contacts of COVID-19 cases were also closely monitored by undergoing daily polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for seven days. However, the gradual shift towards living with COVID-19 and relaxing of measures was expected to inevitably bring about a surge in community cases, especially with the arrival of new variants.

The Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant, which has a higher transmission rate and shorter incubation period than previous strains, was first discovered in Botswana in November 2021 and soon after was named a variant of concern by the World Health Organization.4 , 5 Studies have estimated Omicron to have an infectivity rate that is ten-fold higher than that of the wild type and approximately twice as high as that of the Delta variant.6 Omicron quickly became the dominant strain after it first emerged in Singapore in early December 2021. The high infectivity rate of Omicron, coupled with the discontinuation of containment measures, led to a jump in community cases – reaching a record high of more than 25,000 cases a day at its peak in February 2022.7

Despite the revised hospital changes catering to a controlled mitigation approach, numerous safe management measures were still kept in place to prevent nosocomial transmission and hospital clusters. For instance, staff and inpatients continued to undergo RRT, and previously established enhanced sickness surveillance systems remained in place to screen staff with acute respiratory illness (ARI) symptoms.8 , 9 Furthermore, staff continued to don enhanced PPE, maintain 1-meter safe distancing, have meals alone, and suspend social gatherings at work. Hence, staff infected with SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to have acquired the infection in the community than in the hospital. Therefore, we posit that HCWs might serve as good sentinels for emerging COVID-19 trends in the community, as picked up by our comprehensive surveillance systems.

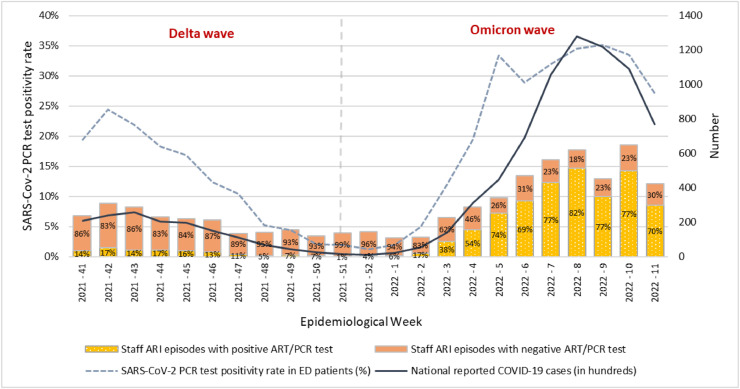

We present weekly data on the SARS-CoV-2 PCR test positivity rate in patients attending at the hospital's emergency department (ED) for ARI, number of staff ARI episodes and SARS-CoV-2 antigen/PCR test positive rate, and national reported COVID-19 cases from October 10, 2021 to March 19, 2022 (i.e., epidemiological week (e-week) 41, 2021 to e-week 11, 2022) (Fig. 1 ). After the change in strategy from containment to controlled mitigation on e-week 41, the SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate among ED ARI patients rose slightly in e-week 42, 2021. Notably, the uptick was observed a week before the increase in national COVID-19 cases reported by Singapore's Ministry of Health. Subsequently, SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate in ED patients decreased steadily till the end of the year. During the trough weeks (e-week 50, 2021 to e-week 1, 2022), the mean (standard deviation) of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate among ED ARI patients, proportion of staff ARI with positive antigen/PCR test, and national reported COVID-19 cases were 1.8% (0.4%), 4.7% (2.4%), and 1862 (648.6) respectively. On e-week 2, 2022, there was a jump in SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate among ED ARI patients and symptomatic staff to 4.9% and 17% respectively, beyond two standard deviations above the mean weekly rates of the trough weeks. The national reported COVID-19 cases also surged to 5260 that week, indicating the emergence of the Omicron variant. The following weeks showed continued uptrending of COVID-19 in ED patients, staff, and the community, as Omicron swept through Singapore. As the national reported COVID-19 cases crested on e-week 8, 2022, the SARS-CoV-2 test positivity rate among ED patients and staff also peaked. Following which, a decline was observed.

Fig 1.

Weekly SARS-Cov-2 PCR test positivity rate among patients who attended at the emergency department with ARI symptoms, number of COVID-19 cases in the community, and numbers of staff ARI episodes with a positive and negative SARS-CoV-2 antigen rapid or PCR test, from October 10, 2021 through March 19, 2022.

Throughout the study period, safe management measures such as bi-weekly RRT, enhanced PPE, having meals alone, and suspension of social activities remained in place, which enabled the surveillance of staff ARI incidence and SARS-CoV-2 positivity to serve as good sentinel surveillance of COVID-19 in the community. Furthermore, surveillance on the SARS-Cov-2 test positivity rate of ED ARI patients provided a one-week lead time in detecting the national uptick of COVID-19 cases after the discontinuation of containment strategies in October 2021. All ARI patients attending at the ED were screened with the PCR test, which is 30–40% more sensitive than the ART more frequently adopted in the community.10 With the emergence of the Omicron variant, whose infections have higher viral loads occurring earlier in the course of illness, and a shorter incubation period, surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity in ED patients did not provide a time advantage, but showed an increase at the same time as national reported COVID-19 cases.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that staff and patients undergoing surveillance in an acute hospital can serve as good sentinels for the national surveillance of COVID-19. With the relentless waves of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, such surveillance systems can serve as good and sensitive complements to the national reporting system.

References

- 1.Wang Y., Tan Kuan J., Tay M.Z., Lim D.W., Htun H.L., Kyaw W.M., et al. Dancing with COVID-19 after the Hammer is Lifted: enhancing healthcare worker surveillance. J Infect. 2020;81(6):e13–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.07.037. Dec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim R.H.F., Htun H.L., Li A.L., Guo H., Kyaw W.M., Hein A.A., et al. Fending off Delta - hospital measures to reduce nosocomial transmission of COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;117:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.01.069. Feb 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Revised guidance on covid-19 mitigation measures in hospitals. 2021.

- 4.Khan N.A., Al-Thani H., El-Menyar A. The emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variant (Omicron) and increasing calls for COVID-19 vaccine boosters-The debate continues. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2022;45 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2021.102246. Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern [Internet]. www.who.int. 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern.

- 6.Tian D., Sun Y., Xu H., Ye Q. The emergence and epidemic characteristics of the highly mutated SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J Med Virol. 2022 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27643. Feb 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Singapore. MOH | COVID-19 Statistics [Internet]. www.moh.gov.sg. 2022. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sg/covid-19/statistics.

- 8.Lim W.-.Y., Tan G.S.E., Htun H.L., Phua H.P., Kyaw W.M., Guo H., et al. First nosocomial cluster of COVID-19 due to the Delta variant in a major acute care hospital in Singapore: investigations and outbreak response. J Hosp Infect. 2022;122:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2021.12.011. Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Htun H.L., Lim D.W., Kyaw W.M., Loh W.-.N.J., Lee L.T., Ang B., et al. Responding to the COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: staff protection and staff temperature and sickness surveillance systems. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa468. Apr 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinnes J., Deeks J.J., Berhane S., Taylor M., Adriano A., Davenport C., et al. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;(3) doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd013705.pub2. Mar 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]