Abstract

The increasing global prevalence of endocrine diseases like type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) elevates the need for cellular replacement approaches, which can potentially enhance therapeutic durability and outcomes. Central to any cell therapy is the design of delivery systems that support cell survival and integration. In T1DM, well-established fabrication methods have created a wide range of implants, ranging from 3D macro-scale scaffolds to nano-scale coatings. These traditional methods, however, are often challenged by their inherent limitations in reproducible and discreet fabrication, particularly when scaling to the clinic. Additive manufacturing (AM) techniques provide a means to address these challenges by delivering improved control over construct geometry and microscale component placement. While still early in development in the context of T1DM cellular transplantation, the integration of AM approaches serves to improve nutrient material transport, vascularization efficiency, and the accuracy of cell, matrix, and local therapeutic placement. This review highlights current methods in T1DM cellular transplantation and the potential of AM approaches to overcome these limitations. In addition, emerging AM technologies and their broader application to cell-based therapy are discussed.

Keywords: bioprinting, vascularization, biomaterials, fabrication

1. Cellular Implants for the Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes

Cell-based therapies provide a potential curative approach for resolving Type I diabetes mellitus (T1DM) via the replacement of the insulin-producing cells lost to autoimmune destruction1–3. In the native pancreas, these insulin-producing cells, termed β-cells, work to modulate metabolism and blood sugar in conjunction with other hormone-secreting cells housed within the pancreatic islet4. Once these cells are targeted and destroyed by the endogenous immune system during the pathology of T1DM, uncontrollable peaks in blood glucose develop, which are fatal without exogenous insulin therapy4. Though treatments to improve the lives of those with T1DM are evolving, most notably closed-loop systems that integrate a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) with an insulin pump, these approaches fail to replicate the complex and non-linear process of insulin secretion provided by endogenous β-cells5. The resulting long-term glycemic instability can lead to life-threatening health complications, including kidney disease, eye damage, and cardiovascular dysfunction4. To restore this metabolic control and alleviate these long-term effects, clinical islet transplantation (CIT) aims to deliver a durable treatment for T1DM through the transplantation of cadaveric donor islets6–11. CIT protocols currently infuse these cell clusters into the hepatic portal vein, whereby islets lodge into the liver microvasculature and rapidly respond to changes in blood glucose6–11. Systemic immunosuppression is currently the most effective method for suppressing the rejection of donor islets, but significant cellular loss associated with the transplant location, local inflammation, and insufficient immunosuppression results in sub-therapeutic dosages and generally short-term efficacy8.

To alleviate stressors inherent to the hepatic portal vein site, namely the physical stress of transplantation, lack of native extracellular matrix and chemical signaling, and insufficient vascularization and oxygen delivery, work has shifted to exploring alternative transplant sites and leveraging biomaterial platforms12–19. Alternative implant sites provide different advantages, including vascular access (e.g. omental and intramuscular), accommodations for larger implants (e.g., omental or intraperitoneal), and/or less invasive implantation, retrieval, and monitoring (e.g. subcutaneous); however, no site fulfills all desired features. Biomaterial platforms can further elevate islet survival and implant safety by providing 3-D distribution and the safety of retrievability. They can also be used to locally deliver supportive agents, such as pro-survival factors to improve engraftment and/or immunotherapeutics to control inflammation and prevent immunological destruction20–24. In addition, the polymeric encapsulation of cells within immunoisolatory hydrogels can mitigate direct immune cell attack and enhance graft protection25,26. These biomaterial strategies for housing and supporting islets within a wide range of transplant sites have shown great promise, establishing the basis for hopeful application in humans.

The clinical translation of devices to support a therapeutic dosage of islets in humans, however, is challenged using current device fabrication methods. These methods struggle to provide adequate granularity and reproducibility. Also, the lack of control over cell, therapeutic, and overall biomaterial distribution present significant roadblocks to the creation of human-scale devices, as the variance of these features can propagate hypoxic and nutrient gradients that impact engraftment. Insufficient nutritional delivery is further exacerbated by the inability to efficiently vascularize transplanted structures and provide endogenous oxygenation and nutrients. As a result, devices are compromised by resorting to decreased thickness or cell loading and/or sacrificing a portion of the cell cluster population post-transplant27. To improve factors like nutrient transport, local therapeutic release, and overall engraftment, novel fabrications methods should be implemented. Herein, we describe the emergence of a field of techniques, referred to as additive manufacturing (AM), that support the reproducible construction of complex three-dimensional structures using biocompatible materials. We detail specific AM methods, outline applications for tissue engineering, and further postulate on future applications for improving the clinical translatability and efficacy of cell-based treatments for T1DM.

2. Overview of Additive Manufacturing Methods

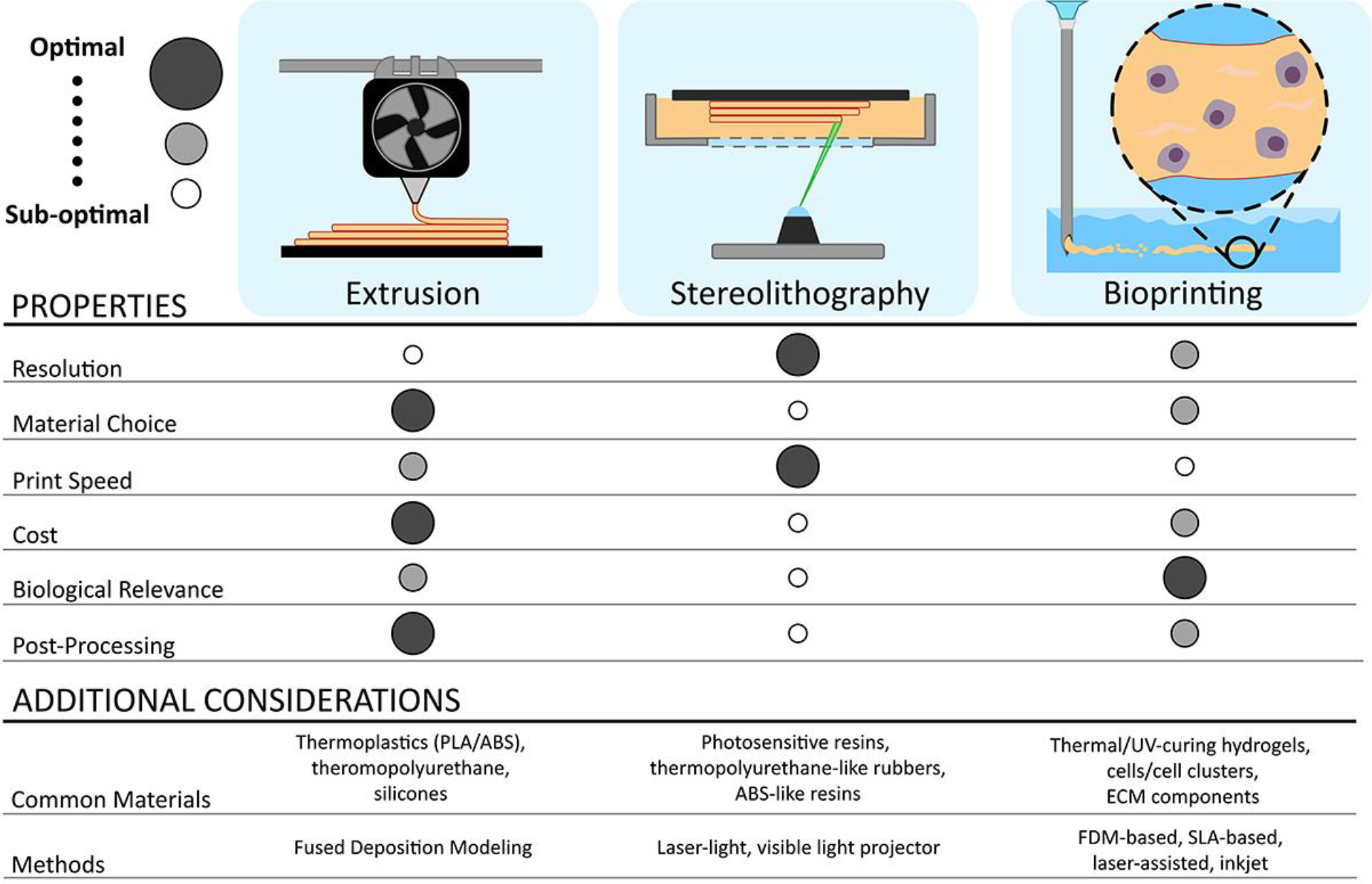

Additive manufacturing, or AM, is a family of fabrication techniques wherein silico modeling is used to define a complex, three-dimensional structure that is on-site fabricated through controlled methods with minimal offsite post-processing. AM takes many forms with fused filament fabrication (FFF), stereolithography (SLA), and bioprinting being the most common methods used for biomedical applications28–31. FFF, also commonly referred to as fused deposition modeling (FDM), is a layer-by-layer fabrication method using heated thermoplastics. FFF use in rapid prototyping spans decades, as it can consistently re-create three-dimensional computer models derived from commercially available software32. More recently, this technique has found a place in medical implants through the use of biocompatible and biodegradable materials, such as poly-lactic acid (PLA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polycaprolactone (PCL), or proprietary material formations33. Compared to traditional biomaterials fabrication techniques, such as solvent-leaching and bulk-casting, FFF results in greater material geometric reproducibility and reduced variability, which are desirable features for biomedical devices. PLA and PVA FFF prints have successfully housed transplanted cells and served as rigid scaffolding for bone formation, with demonstrated long-term biocompatibility and integration34–37. A restriction of FFF, however, is the limited resolution of the printing. Independent of the exact machining and positional systems used, the X-Y resolution of an FFF print is primarily dependent on the nozzle diameter and mechanical properties of the extruded material, resulting in minimum feature size of approximately 250 μm33. Stereolithography, or SLA, is an alternative printing method employing light curable liquid resins, such as polyurethanes, ceramics, and hard ABS-like materials38–40. In this approach, the resin is printed by exposing the photocurable polymer to a light source (e.g. light projector, laser) to facilitate the layer-by-layer fabrication of the desired model. Due to the higher precision provided by using light as the curing method, both the printing speed and resolution (50–150 μm, depending on the axis) are drastically increased over traditional FFF methods; however, this comes at the cost of material choice and additional processing steps for finished prints41. Biomedical applications are historically limited, as most commercial resins used in SLA are rigid and poorly evaluated for long-term soft tissue implantation. Thus, SLA has been typically used for surgical guides and dentistry applications40–42. Imbuing light-sensitive resins with traditional biomaterials like hydroxyapatite (HAP) for bone formation has expanded their medical utility; however, heavy processing and evaluation is required to mitigate cytotoxic effects39. Recently, more favorable materials such as thermoplastic polyurethane-like rubbers and custom formations have become available, permitting the fabrication of flexible scaffolds and microneedle arrays38,43. Despite this, SLA tends to be viewed as a more specialized printing method, highly dependent on available materials and applications.

Incorporating the advantages of the core technologies from FFF and SLA, bioprinting, which is a broad term encompassing the layer-by-layer deposition of biocompatible, often biodegradable materials alongside encapsulated cells and therapeutics, seeks to provide a more versatile system. This method is attractive due to the inherent control of cell and material placement, with resolutions up to 50 μm and the potential for high cell viability (i.e., > 80%)44. The four primary bioprinting methods include inkjet bioprinting, where droplets of biomaterials can be deposited on a substrate without physical contact using charge or other methods; laser-assisted, where irradiation of an energy-absorbing substrate can be used to deposit evaporated droplets of biomaterials onto a substrate; and more traditional methods like FDM and SLA-based bioprinting45,46. In selecting the optimal method for a specific application, many factors come into play including desired printing speed, spatial resolution, cell viability, cell density, and cost. Although inkjet bioprinting allows low-cost printing at high speed and resolution, this method typically struggles in creating stable vertical structures due to the low viscosity of the bioinks44. FDM and SLA-based bioprinting methods are better candidates for creating true three-dimensional structures, as their higher viscosity bioinks offer increased structural support; however, these techniques exhibit challenges, e.g. low cell viability during extrusion for FDM-based bioprinting and narrow bioink choice for SLA-based bioprinting44. Compared to the other classic bioprinting methods, laser-assisted bioprinting methods exhibit the highest preservation of cell viability while maintaining fast printing speeds and spatial resolution44. Although costly, laser-assisted allows for increased cell density, greater than 95% cell viability after printing, and the usage of highly viscous bioinks. As a relatively new technique, the full impacts of laser exposure on the printed cells and biomaterials within the bioinks is still being investigated, which has delayed more widespread adoption.

The application of bioprinting methods for biomedical applications is varied. For example, laser-assisted bioprinting methods are typically used for implants that require high spatial resolution, including the creation of bone, skin, and adipose tissue models31,47. In contrast, FDM-based bioprinting is more likely to be used to create vasculature and skeletal muscle models, as cells often migrate within completed constructs during the process of self-assembling structures like vessels 29,48. Additionally, the increased printing speeds and elevated cell viability afforded by laser-assisted and SLA-based bioprinting approaches have increased their feasibility for engineering larger tissues; however, this method is still hindered by restrictions imposed by the printer itself and currently available printing materials. Faster printing methods are needed to mitigate deleterious impacts to the cells and enhance overall scalability. Furthermore, the ability to recapitulate the in vivo environment can be improved by developing methods to employ multiple bioinks and finding ways to increase spatial resolution. Groups have explored these avenues using innovative nozzle, syringe, and motor control system techniques49.

Overall, AM methods have a clear potential to improve the rational design and development of tissue-engineered implants. Focusing on cell-based therapy for T1DM, the need to translate device development from traditional fabrication methods to AM approaches is high, due to current roadblocks. Specifically, factors like impaired oxygen transport, lack of control over cell and material placement, and the inability to form robust and consistent vasculature continue to put restrictions on the graft size and subsequently hinder clinical translation. Applying AM methods to address these limitations could permit the fabrication of a superior insulin-secreting, cell-based implant.

3. Additive Manufacturing and Applications in β-Cell Transplantation

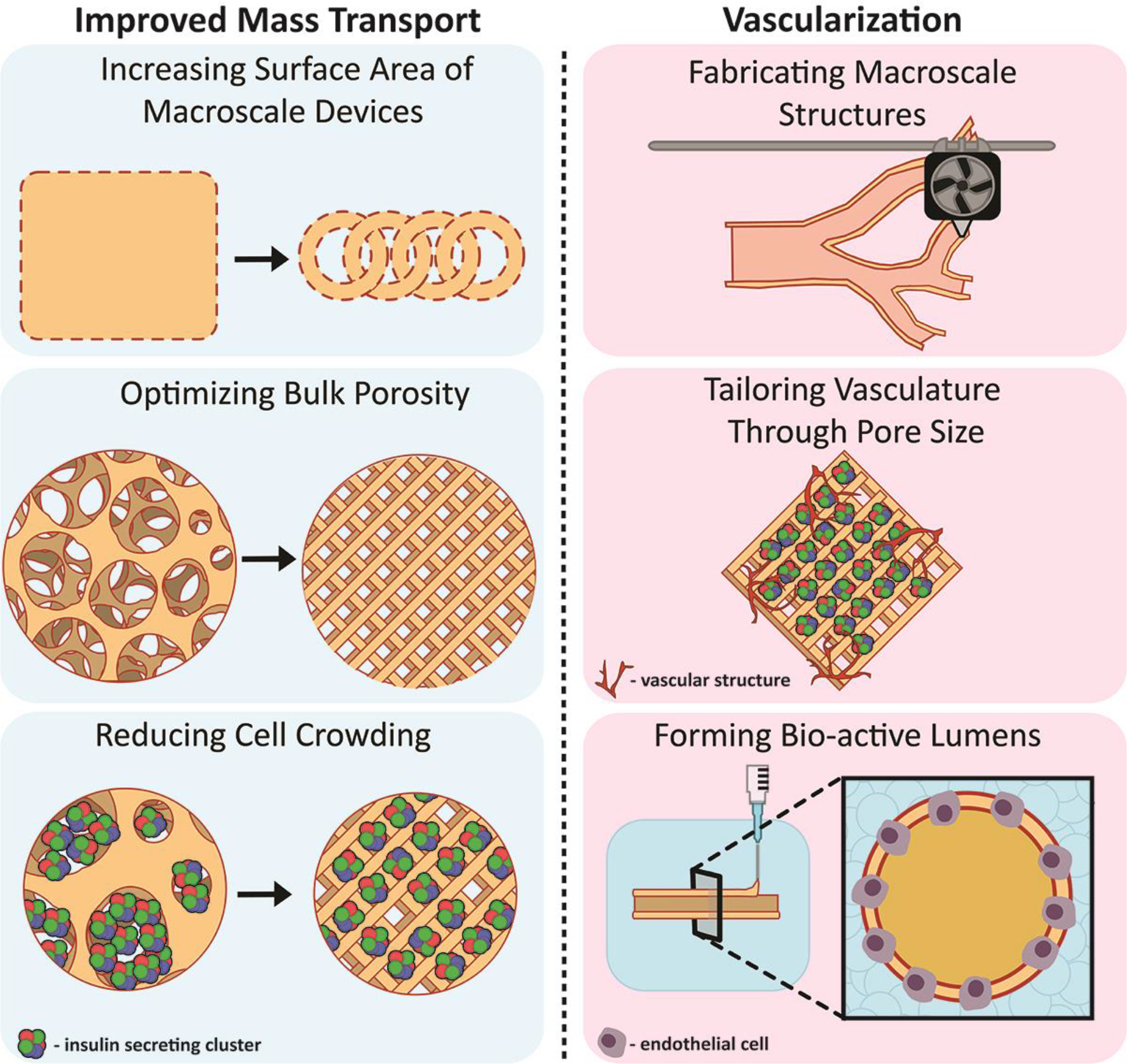

Optimized Implant Geometry to Improve Nutrient Transport

A primary consideration in engineering tissues for islet transplantation is maximizing nutritional transport by reducing diffusional distances between the implanted cells and the surrounding environment15,50. While sufficient nutrient delivery is a key consideration for most cellular implants, meeting the metabolic demands for islets, particularly concerning oxygen, is arduous51. Previous work has focused on the role that the parameters of geometry and pore size play in improving the mass transport of critical metabolites such as oxygen and glucose. Traditional scaffold fabrication methods introduce macro-scale porosity through techniques like porogen leaching, electrospinning, and gas foaming52. Resulting highly porous (> 85% v/v) materials provide physical support and distribution of the islets, while also increasing nutritional access by both the passive transport of oxygen through their inherent open space and the facilitation of host intra-device vascularization53–55. Modulating pore size using these methods is feasible via modification of porogen size and loading, which alters both the overall pore size and pore interconnectivity56–59. In addition to improved nutrient transport, implant porosity globally impacts biocompatibility and engraftment long-term, with optimal pore sizes facilitating healthy cellular infiltration and remodeling20,21. The intimate control of pore size and connectivity using particulate leaching and gas foaming methods, however, is limited, resulting in heterogeneity of the final scaffold product. In addition, uneven geometry as a result of the irregular porogen surface can lead to rough macro-scale topographies, potentially increasing the risk of proinflammatory responses60,61. To enhance control over both macro and microporosity, an alternative approach combined electrospinning with photoresist molds and laser drilling to achieve both high porosity and a niche-based cell spheroid distribution 62,63. The resulting devices prevented islet aggregation and retained islet function. While this more complex method elevated the reproducibility of porosity and islet distribution, the fabrication of new molds remains time-consuming and non-modular.

Alternative to open scaffolds, the encapsulation of cells within nano- or micro-porous hydrogels that impair the direct interactions of host and implanted cells is a common transplant technique for insulin-producing cells, as it can mitigate the immunological rejection of the implant64–69. Encapsulation can range from nano-scale coatings to macroscale hydrogels and can be fabricated from materials such as alginate, poly(ethylene glycol), and agarose64. Nanoencapsulation or ultrathin coatings (<20 μm) can permit the protection of cells; however, incomplete encapsulation and complexity of fabrication can make these methods difficult to scale67,70. At the microencapsulation scale, islets can be housed in hydrogels 400–900 μm in diameter, which delivers more complete encapsulation at the cost of hindered mass transport to the encapsulated cells.64,65 At the macroscale, fabrication methods are less arduous and the retrieval of transplanted cells in the event of graft failure becomes more feasible but at the cost of significantly delayed nutritional diffusion through the thicker hydrogels, resulting in hypoxic gradients.64,65,71 Geometric manipulation to increase surface area and global mass transport efficiency is one approach to improve transport. For example, Wang et. al. created a single micron-scale encapsulation tube for housing insulin-producing clusters by augmenting alginate with electrospun nanofibers, resulting in an efficacious implant.72 Alternative methods that leverage additional technologies to improve nutrient delivery, such as the integration of oxygen-generating materials and/or pro-vasculogenic factors, can improve oxygen access for the cells within traditional macroencapsulation devices73,74. However, the integration of these features discreetly and consistently for rapid fabrication using traditional methods is challenging.

AM approaches can support the integration of more complex, but reproducible, geometries and features to mitigate mass transport roadblocks. At a surface level, AM allows for the fabrication of scaffolds from historically validated biomaterials but with defined and consistent geometry based on distinct design parameters. This robust control delivers a defined macro-scale geometry and micro-scale pore size, allowing the user to tailor their materials to different applications75–77. From a purely engineering perspective, simply improving the total surface area to volume ratio for an implant design should drastically improve oxygen and nutrient diffusion. For example, to modulate the global construct shape and provide consistency of the macro-implant, Grattoni’s team used a traditional FFF method to print a PLA-based implant with discreet spatial patterns at high resolution78,79. The internal 300 μm pore size scaffolds provided defined spaces for distributing individual islets within the device inner chamber, while smaller external micro-pores supported subcutaneous perfusion and dedicated inputs for islets infusion78. Additional studies using the scaffold to house testosterone-secreting Leydig cells, in combination with a VEGF-doped platelet-rich plasma hydrogel, reported successful device vascularization and sustained cellular survival in a murine, subcutaneous transplant model. Ernst et. al. further explored this concept for macroencapsulation implants by applying a hydrogel coating onto a toroidal AM-elastomer backbone38. This interlocking, toroid shape, printed using a flexible proprietary resin, increased the macroscale total surface area, thereby permitting more efficient oxygen delivery to the encapsulated cells due to the decreased diffusional distance. Compared to control spherical hydrogels, this new geometry allowed for improved mass transport, which yielded increased cell viability post-encapsulation in the alginate hydrogel. Implantation of these connected rings restored normoglycemia in diabetic murine recipients. Multiple studies have solidly demonstrated the expected benefit of AM in improving the flexibility in device geometry for improved mass transport80,81.

Improved Vascularization and Engraftment

Rich host vascularization of devices is necessary for the long-term survival of most transplanted cells. For β-cell therapy in T1DM, the competency and consistency of the vascular network are essential to not only support efficient nutrient delivery but to ensure effective insulin kinetics. In earlier platforms, the infiltration by endogenous cells and subsequent anastomoses with islets was directed by modifying bulk material properties to create pore and/orsurface geometric features that encourage vessel formation20,53,82–86 These approaches were successful in generating robust vasculature; however, islet loss post-transplantation during the delay in the formation of competent vascularization remains a challenge. In response, work has shifted to “priming” the transplant site by pre-vascularizing biomaterials with endogenous cells or generating vessels in vitro for accelerated vessel development87–89. These approaches have significantly improved the efficiency in the development of a competent vascular bed. Continuous improvements using new hydrogel formulations, novel therapeutics, and culture techniques, like co-cultures, have further advanced the field14,15,90,91. Leveraging advanced manufacturing methods, however, can further optimize micro-scale geometry to not only accelerate graft anastomosis with host vasculature but control intra-device vascular structure and homogeneity.

The design of vascular structures using AM methods is a long-standing interest in tissue engineering device development. Initial work using FDM printing methods focused on reproducing macro-scale vascular structures. For example, Visser and colleagues created large-scale vessel-like conduits with macroscale branching structures using multi-material FDM printing of PVA and PCL as the support and printing material, respectively49. Using an SLA-based printing method, Meyer et. al. fabricated flexible, tubular structures made from proprietary materials92. Though these structures could be used to replace large sections of damaged tissue, their scale was not highly applicable to cell-based transplants. In response, groups such as Grattoni and Niklason leveraged traditional FDM printing techniques to create patterned structures to guide vasculature formation both in vitro and in vivo78,79,86. This process permitted Niklason’s group to interrogate the effect of pore size on hSMC vessel formation and Grattoni’s group to create a subcutaneous device for transplantation and subsequent vascularization of human islets in a nude mouse model. AM-based fabrication resulted in improved implants, as increased printing resolution allowed for the control of microscale pore size and the introduction of more bio-active/degradable materials such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acids) (PLGA). These systems supported rapid development and testing; however, the use of more rigid materials is not optimal for long-term soft tissue implantation. Shifting to bioprinting technologies, complex and branching conduits can be formed using supportive hydrogels, such as collagen or methacrylate gels, which allow cells to sprout throughout the matrix under the desired geometric constraints93–96. These approaches not only support the investigation of the biology of vessel formation, but they lay the groundwork for the eventual clinical translation of these techniques to a broad swath of cell-based therapies. Islet-specific work in the AM-vascularization space has primarily focused on fundamental biological discoveries, with groups like Hospodiuk et. al. using FDM technology to explore vessel sprouting from pseudo islets 97. While publications creating macroscale, AM-manufactured vascularized constructs for islet transplantation are currently limited, advancements made in leveraging AM to support favorable vascularization conditions, such as the selection of optimal pore sizes and optimal material choices, facilitate their translation to β-cell therapy in T1DM.

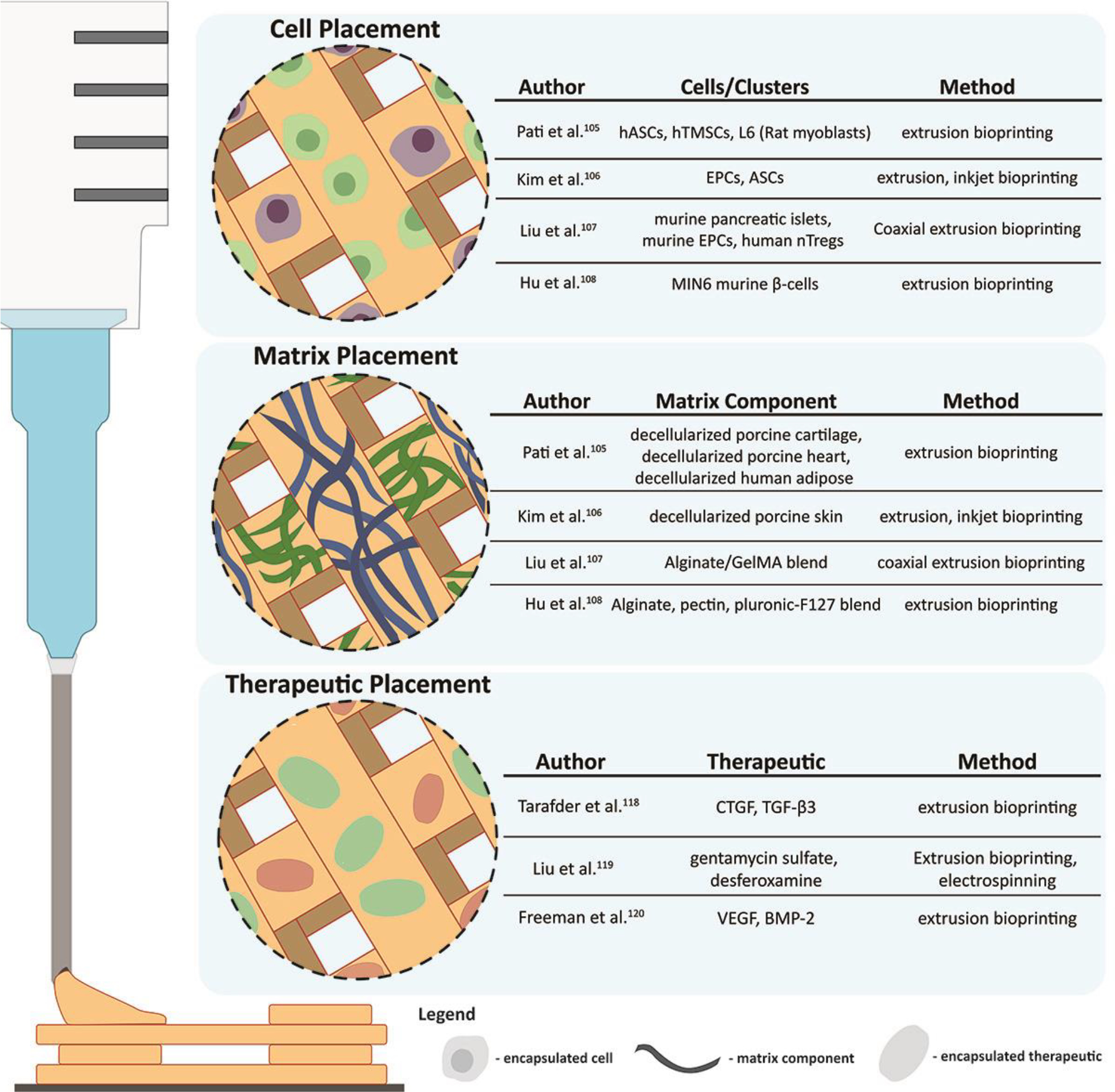

Controlled Cell and Matrix Placement

Beyond the utilization of AM-based methods to improve three-dimensional biomaterial distribution, there is potential for micro-level control of cell and protein distribution. This degree of control would benefit the design of T1DM implants containing β-cells, as their cellular function is highly dependent on factors like oxygen access and interactions with critical extracellular matrix (ECM)-binding proteins98–100. Providing optimal cellular distribution, as well as a supportive ECM niche, would reduce the rapid loss of function and anoikis-driven apoptosis commonly observed post-transplantation. Most traditional scaffold fabrication methods load the cells post-device fabrication, which leads to broad heterogeneity of cellular distribution and challenges in loading larger cellular spheroids. Furthermore, separating the material fabrication and cell loading process leads to elevated bulk of the final implant volume. Traditional encapsulation methods that support in situ material and cell placement reduce these issues but struggle with unpredictable cellular distribution within the material and incomplete encapsulation. These issues are exacerbated when incorporating large cellular spheroids, such as islets. For example, alginate islet microbead encapsulation using fluidic or electrostatic bead generation methods commonly results in either heterogeneous clusters per capsule for large microbead sizes or incomplete encapsulation for smaller microbead sizes.101 Seeking to support the loaded cells through the integration of ECM components further complicates device fabrication. While numerous publications have shown improved islet function when incorporating ECM proteins such as laminin, collagen, and fibronectin, most studies present these components through surface coatings of traditional biomaterials or bulk hydrogels, limiting their homogenous presentation across the graft.102–104

AM-based bioprinting approaches provide an avenue to remove these limitations. Specifically, bioprinting supports the in situ encapsulation and printing of multiple cell types and ECM while simultaneously controlling 3D placement and dimensions. This utility was clearly demonstrated by works such as that of Pati et. al. who printed decellularized ECM (dECM) hydrogels alongside cells, forming a tissue analogue with different properties105. In this setup, cells were exposed to different proteins depending on the desired geometry and dECM distribution, allowing for the enhanced expression of targeted phenotypic genes, e.g. cardiogenic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic, when compared to just collagen matrix. Preliminary work additionally demonstrated the ability to print multiple dECM bioinks into a single construct, opening the door for more complex tissue analogues containing discreet spatial ECM patterns. The work of Kim et. al. further demonstrated the benefit of spatial control through the fabrication of a skin patch with a defined dermis and epidermis region, which was printed using discreet cell types and dECM106. Though in its relative infancy, this methodology is also moving into the diabetes space with groups like Liu et. al. developing printing platforms suitable for islets107. Using a custom-made coaxial printer, they created a core-shell structure where islets could be printed in alginate, gelatin, and methacryloyl hydrogels that were surrounded by endothelial progenitors. This resulting device delivered an immunoisolatory platform of defined geometrical scales containing uniformly distributed islets as well as supportive cells that could theoretically promote peripheral device vascularization once fully engrafted. Going further, there is potential for non-endogenous bioactive materials to be printed alongside islets as well. Examples like Hu et. al. highlight the ability to print β-cells into hydrogels doped with immune-regulatory components such as pectin108. Though studies involving islets are still early, advancements in bioprinting of cell-based constructs show the potential of this approach to improve the physical and chemical environment for transplanted cells through controlled matrix protein and cell placement. Such approaches would also elevate the consistency of the therapeutic dosage, as well as the final product.

Controlled Integration of Therapeutic Agents

Parallel to cell and matrix placement in cell-based construct design, the notion of using local therapeutics to regulate cell behavior and enhance transplantation platforms has grown in popularity in recent years. Strategically placing therapeutics into these islet implants has the potential to help recapitulate the in vivo environment by assisting in multiple critical roles, including angiogenesis, pro-islet health, and immunomodulation. Angiogenesis has long been a primary target for cell-based therapies due to the inherent requirement for the transport of oxygen and nutrients to the graft. Facilitation of vessel development usually employs a critical growth factor, for example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), to accelerate the formation of endogenous vessels22. In addition, the incorporation of pro-islet therapeutics, such as small molecules (e.g., curcumin, exenatide, and vitamin D) and hormonal therapeutics (e.g. 17β-estradiol), can lead to decreased apoptosis and elevated and/or more durable insulin secretion20,109–112. Finally, local immunomodulation broadly involves the local release or presentation of agents that dampen the innate or adaptive immune response to transplanted cells, which would support enhanced engraftment and long-term survival while reducing the need for systemic immune suppression. These therapeutics can take many forms, ranging from small-molecule steroids (dexamethasone, fingolimod)20,111,113,114, to larger macrolides (rapamycin, tacrolimus)115,116 and proteins (PD-L1)117. Overall, these therapeutics can provide significant improvements when delivered in the context of local release or presentation; however, their delivery is typically limited to homogenous distribution within the graft. This limits spatial customization of the graft site and can lead to deleterious effects on the transplanted cells or the host response. Specifically, numerous immunomodulating therapeutics impart negative effects on islet health when delivered in close proximity, therefore proper consideration of dosage is crucial for success21,113. Furthermore, the local delivery of potent anti-inflammatory agents can lead to suppression of implant engraftment, as the host cells are impaired in migrating into the implant20,21. Finally, the spatial control over the delivery of therapeutic agents provides a unique means to create discreet gradients within and around the implant site, thereby delivering more nuanced and physiological cues to the cells of interest.

The spatial control over therapeutic delivery concerning transplanted cells could provide new avenues for the discreet modulation of both host and transplanted cell responses. AM methods, particularly bioprinting techniques, are a likely candidate for solving these issues. For example, Tarafder et. al. combined traditional depot-based drug release with bioprinting to achieve distinct control over therapeutic location118. This melding of PLGA microspheres with PCL allowed for the spatial release of transforming growth factor beta-3 (TGF-β3) and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), leading to the generation of heterogeneous in vitro tissues. Similarly, Liu et. al. combined bioprinting with electrospinning to create scaffolds with simultaneous release of bone morphogenetic protein-9 (BMP-9) and VEGF for osteochondral tissue generation119. Alternatively, Freeman et. al. fabricated composite hydrogels capable of simultaneously releasing VEGF and BMP-9 with a construct-wide gradient120. This enabled them to experiment with different loadings to find the optimal setup for in vivo angiogenesis. Though these methods have yet to be applied directly to islet transplantation, their use in conjunction with previously mentioned techniques shows promise for their translation. Specifically, the localization of a potent modulating therapeutic to the periphery of a device would allow for enhanced targeting of the host immune system while limiting the agent’s potentially negative effects on islets. In addition, pro-islet therapeutics could be simultaneously loaded within the matrix space more closely localized with the islets, which could enhance their impact. This prospective application, therefore, has untapped potential for improving the long-term outlook of cell-based devices for the sustained treatment of T1DM.

4. Emerging Technologies and Clinical Aspirations

As an emerging field, there continues to be iterative improvements to AM methods that enhance accessibility and decrease costs; however, inherent limitations on the scale of fabrication and material choice are remaining roadblocks inhibiting their eventual translation to tissue-engineered clinical products. To address these obstacles, unique AM methods have emerged in the healthcare space that present novel solutions to these problems.

Increased Scale of Bioactive Constructs

A crucial limitation preventing the translation of bioprinting to the human scale is the inability to print large, complex constructs using hydrogel-based materials. In typical bioprinting, hydrogels are extruded as a semi-viscous liquid then cross-linked into its printed orientation to form three-dimensional structures. Thermal or UV crosslinking is often used due to its greater compatibility with encapsulated cells; however, in the time from extrusion to full crosslinking, gravity pulls and distorts the structure, making the fabrication of large constructs with overhangs impossible. As a result, groups often default to a single pattern, commonly termed the ‘crosshatch’, to make their constructs35,76,80,120–122. Recent advancements in the printing medium, however, have addressed this challenge. One example of interest is the work of the Feinberg group using supportive matrices 123. Described as the freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels, or FRESH, large-scale printing of soft bio-inks is made possible within a supportive gelatin matrix. Once the bio-ink is cross-linked, the support matrix can be non-destructively melted away to release the finished structure. This methodology allows for traditionally impossible structures with complex overhangs and void spaces to be printed, permitting the fabrication of structures on the scale of a human heart using biocompatible polymers123,124. Another approach in 3D soft material printing has emerged from the Angelini group. By printing within a matrix of small hydrogel spheres as supports, termed jammed microgels, semi-viscous materials can be printed in three-dimensional space. This enables the high accuracy printing of complex models using biocompatible inks like collagen, as well as stable elastomer structures such as organosilicones125,126. With the development of these new printing approaches, challenges with bioprinting scalability are largely being addressed.

Optimized Multi-material Printing

As groups strive to further recapitulate the native microenvironment of transplanted cells to improve engraftment, the printing of multiple biocompatible materials has gained popularity. As discussed previously, highly complex cell-based therapies are likely to require multiple cells/cell cluster types, therapeutics, and materials to achieve the desired in vivo effect, so the implementation of streamlined fabrication techniques will be essential. A potential solution to this is single-tool, multi-material fabrication. Typically, FDM-based fabrication methods (FFF/FDM, FDM-bioprinting) utilize multiple tools to print two or more different materials/inks for a single device. This requirement results in greater complexity and printing time to achieve seamless results while also increasing the cost of entry. To remove these penalties on multi-material prints, groups like Skylar-Scott et. al. have implemented single nozzle solutions127. Using a combination of gas-based extrusion and a custom-made manifold, flexible silicones can be extruded discretely or mixed within a single tool head to yield complex prints at accelerated rates. Moving to more biocompatible materials, Liu et. al. utilized a similar multi-material manifold to extrude bioinks128. Specifically, they fabricated bulk hydrogels with up to four discrete “zones” of cells, though the height of their structures was limited due to the lack of support material. As these methods of fabrication become more optimized, opportunities will arise to significantly improve the printing of more sensitive cell types, such as islets, by minimizing the printing time and better tailoring the surrounding microenvironment.

Current Pathways and Roadblocks to Clinical Applications

AM-based approaches, to date, have demonstrated significant potential to deliver superior device designs for a broad spectrum of tissue engineered approaches. There is now a need to push these AM devices to the clinic. Groups such as Paez-Mayorga et. al. and Wang et. al. are contributing to this translation by testing AM fabricated devices within more complex and larger scale preclinical models, such as non-human primates129–131. Product development and clinical application of AM-based devices are slowly increased in prevalence, although most devices are used as surgical guides with only the recent translation of an implantable acellular graft for hard tissue growth132,133. Concurrently, regulatory guidance for AM fabricated acellular or combinatory tissue-engineered products is evolving in the US, EU, and Japan134,135. For example, the FDA recently released a discussion paper on the potential benefits and risks associated with the fabrication of devices on-site for implantation136. It is anticipated that the AM features of enhanced reproducibility and control may lead to reduced challenges in regulatory approval; however, leveraging the unique capacity of AM-based approaches to create devices with highly complex features may alternatively result in a more complicated approval process.

While there are no current AM-based devices in clinical trials for T1DM cell therapy, recent trials using stem cell-derived β-cells, specifically those from Vertex Pharmaceuticals (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04786262) and Viacyte (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03162926, NCT04678557), have demonstrated both market interest and therapeutic potential in this area. Although current results implicate lack of full resolution of T1DM in patients due to sub-therapeutic dosing, hallmark metrics such as elevated serum c-peptide and decreased exogenous insulin dose indicate the feasibility of a theoretically unlimited source for T1DM cell therapy; a significant advancement that would allow for wide scale use137–139. Unfortunately, current stem cell-based implants are still subject to the same major implantation roadblocks experienced by previous CIT implementations, notably inadequate physical and chemical stimuli, improper or delayed vascularization, and the requirement for constant systemic immunosuppression to prevent graft loss. As highlighted herein, AM-based methods have an opportunity to be disruptive by delivering enhanced geometric modularity and complexity of the final device design. Simultaneously, AM-based control over cell and matrix placement can serve to both enhance cell survival and provide a more reproducible final combinatory product. Finally, innovative immunoprotective features can be integrated into the design, including controlled material encapsulation and placement of local drug delivery depots. Future work should seek to translate the utility of AM methods to improving the safety, reproducibility, and functionality of stem cell-based implants for T1DM.

The enhanced 3D design features AM provides theoretically supports the customization of device parameters on a patient-by-patient basis, a trait that could prove invaluable as the field moves towards more personalized medicine and practices. This modularity, however, will likely complicate the regulatory process. Modifying parameters inherently introduces variability, which exponentially grow with each additional parameter. This will likely make standardizing device release criteria for regulatory approval more difficult than one-size-fits-all approaches. To accelerate clinical translation, emerging AM-based cell therapy devices will likely need to focus on single design prototypes prior to moving to customized products. As an additional challenge, emerging T1DM cellular platforms are often combinatory products that use not only multiple biomaterials but also several therapeutics, cell types, and proprietary printing setups. Thus, streamlining the regulatory process for these combinatory AM-based products will likely be the largest hurdles in eventual clinical application.

6. Conclusions

While AM adoption in the translational space is in the early stages, there is clear potential for disruptive discoveries and designs to improve on traditional cell-based transplant platforms for the treatment of T1DM. Due to the highly tunable nature of technologies like FDM, SLA, and bioprinting, there is exponentially greater flexibility for not only initial design and fabrication but also subsequent optimization of construct conditions. Cell-based therapies, especially islet transplantation, have faced fundamental roadblocks to widespread clinical adoption due to factors like hypoxia, immune rejection, and constrained transplant size. With new AM tools available that deliver enhanced control over all aspects of implant design, there is potential for new ideas in the CIT space that can substantially enhance the clinical efficacy and reproducibility of these implants.

Figure 1.

Overview of AM-based methods for fabrication of cell-based transplant platforms

Figure 2.

Improvements to cell-based platforms provided by AM-based approaches focused on elevating nutrient mass transport and graft vascularization

Figure 3.

Applications of AM methods for improved control over cell, matrix protein, and therapeutic placement

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for funding from the US National Institutes of Health grants DK126413 and DK122638, as well as from JDRF grants 3-SRA-2021–1033-S-B and 2-SRA-2021–1024-S-B. RP Accolla is an NIH NHLBI F31 predoctoral fellow (HL156360).

References

- 1.Katsarou A et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 1–17 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson MA, Eisenbarth GS & Michels AW Type 1 diabetes. The Lancet vol. 383 69–82 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daneman D Type 1 diabetes. in Lancet vol. 367 847–858 (Elsevier, 2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katsarou A et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 3, 17016 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenhard MJ & Reeves GD Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion. Arch. Intern. Med. 161, 2293 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan EA et al. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes 54, 2060–2069 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto S Islet cell transplantation for Type 1 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes vol. 2 16–22 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro AMJ et al. Islet Transplantation in Seven Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using a Glucocorticoid-Free Immunosuppressive Regimen. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 230–238 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farney AC, Sutherland DER & Opara EC Evolution of Islet Transplantation for the Last 30 Years. Pancreas 45, 8–20 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro AMJ et al. International Trial of the Edmonton Protocol for Islet Transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 355, 1318–1330 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corrêa-Giannella ML & Raposo do Amaral AS Pancreatic islet transplantation. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 1, 9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pedraza E et al. Macroporous three-dimensional PDMS scaffolds for Extrahepatic Islet Transplantation. Cell Transplant. 22, 1123–1125 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An D et al. Designing a retrievable and scalable cell encapsulation device for potential treatment of type 1 diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115, E263–E272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vlahos AE, Cober N & Sefton MV Modular tissue engineering for the vascularization of subcutaneously transplanted pancreatic islets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, 9337–9342 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuigan AP & Sefton MV Vascularized organoid engineered by modular assembly enables blood perfusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 11461–11466 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kriz J et al. A novel technique for the transplantation of pancreatic islets within a vascularized device into the greater omentum to achieve insulin independence. Am. J. Surg. 203, 793–797 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kin T, Korbutt GS & Rajotte RV Survival and metabolic function of syngeneic rat islet grafts transplanted in the omental pouch. Am. J. Transplant. 3, 281–285 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritschy WM et al. The efficacy of intraperitoneal pancreatic islet isografts in the reversal of diabetes in rats. Transplantation 52, 777–783 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlsson P-O et al. Transplantation of macroencapsulated human islets within the bioartificial pancreas βAir to patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Am. J. Transplant. 18, 1735–1744 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liang J-P et al. Controlled Release of Anti-inflammatory and Pro-angiogenic Factors from Macroporous Scaffolds. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2020.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang K et al. Local release of dexamethasone from macroporous scaffolds accelerates islet transplant engraftment by promotion of anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. Biomaterials 114, 71–81 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phelps EA, Templeman KL, Thulé PM & García AJ Engineered VEGF-releasing PEG–MAL hydrogel for pancreatic islet vascularization. Drug Delivery and Translational Research vol. 5 125–136 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berman DM et al. Long-term survival of nonhuman primate islets implanted in an omental pouch on a biodegradable scaffold. Am. J. Transplant. 9, 91–104 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pareta R et al. Long-term function of islets encapsulated in a redesigned alginate microcapsule construct in omentum pouches of immune-competent diabetic rats. Pancreas 43, 605–613 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holdcraft RW et al. Enhancement of in vitro and in vivo function of agarose-encapsulated porcine islets by changes in the islet microenvironment. Cell Transplant. 23, 929–944 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opara EC, McQuilling JP & Farney AC Microencapsulation of pancreatic islets for use in a bioartificial pancreas. Methods Mol. Biol. 1001, 261–266 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.G F, K L, V N & Q T Assessment of Immune Isolation of Allogeneic Mouse Pancreatic Progenitor Cells by a Macroencapsulation Device. Transplantation 100, 1211–1218 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadia M et al. Adaptation of pharmaceutical excipients to FDM 3D printing for the fabrication of patient-tailored immediate release tablets. Int. J. Pharm. 513, 659–668 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merceron TK et al. A 3D bioprinted complex structure for engineering the muscle-tendon unit. Biofabrication 7, 35003 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mertz L New world of 3-D printing offers ‘completely new ways of thinking’: Q&A with author, engineer, and 3-D printing expert Hod Lipson. IEEE Pulse vol. 4 12–14 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michael S et al. Tissue Engineered Skin Substitutes Created by Laser-Assisted Bioprinting Form Skin-Like Structures in the Dorsal Skin Fold Chamber in Mice. PLoS One 8, e57741 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandrycky C, Wang Z, Kim K & Kim DH 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnology Advances vol. 34 422–434 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gross BC, Erkal JL, Lockwood SY, Chen C & Spence DM Evaluation of 3D printing and its potential impact on biotechnology and the chemical sciences. Anal. Chem. 86, 3240–3253 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gendviliene I et al. Assessment of the morphology and dimensional accuracy of 3D printed PLA and PLA/HAp scaffolds. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 104, 103616 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Serra T, Planell JA & Navarro M High-resolution PLA-based composite scaffolds via 3-D printing technology. Acta Biomater. 9, 5521–5530 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H, Yang GH, Choi CH, Cho YS & Kim GH Gelatin/PVA scaffolds fabricated using a 3D-printing process employed with a low-temperature plate for hard tissue regeneration: Fabrication and characterizations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 120, 119–127 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenzweig D, Carelli E, Steffen T, Jarzem P & Haglund L 3D-Printed ABS and PLA Scaffolds for Cartilage and Nucleus Pulposus Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 15118–15135 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ernst AU, Wang L & Ma M Interconnected Toroidal Hydrogels for Islet Encapsulation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1900423 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q et al. A study on biosafety of HAP ceramic prepared by SLA-3D printing technology directly. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 98, 327–335 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juneja M et al. Accuracy in dental surgical guide fabrication using different 3-D printing techniques. Addit. Manuf. 22, 243–255 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim T et al. Accuracy of a simplified 3D-printed implant surgical guide. J. Prosthet. Dent. 124, 195–201.e2 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kessler A, Hickel R & Reymus M 3D printing in dentistry-state of the art. Oper. Dent. 45, 30–40 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farias C et al. Three-dimensional (3D) printed microneedles for microencapsulated cell extrusion. Bioengineering 5, 59 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kačarević ŽP et al. An introduction to 3D bioprinting: Possibilities, challenges and future aspects. Materials vol. 11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J, Chen M, Fan X & Zhou H Recent advances in bioprinting techniques: approaches, applications and future prospects. J. Transl. Med. 2016 141 14, 1–15 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X et al. Inkjet Bioprinting of Biomaterials. Chem. Rev. 120, 10793–10833 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauvin R et al. Microfabrication of complex porous tissue engineering scaffolds using 3D projection stereolithography. Biomaterials 33, 3824–3834 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dolati F et al. In vitro evaluation of carbon-nanotube-reinforced bioprintable vascular conduits. Nanotechnology 25, (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Visser J et al. Biofabrication of multi-material anatomically shaped tissue constructs. Biofabrication 5, (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pedraza E, Coronel MM, Fraker CA, Ricordi C & Stabler CL Preventing hypoxia-induced cell death in beta cells and islets via hydrolytically activated, oxygen-generating biomaterials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 4245–4250 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Colton CK Oxygen supply to encapsulated therapeutic cells. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 67–68, 93–110 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Subia B, Kundu J & Kundu SC Biomaterial scaffold fabrication techniques for potential tissue engineering applications 141 X Biomaterial scaffold fabrication techniques for potential tissue engineering applications. www.intechopen.com.

- 53.Pedraza E et al. Macroporous Three-Dimensional PDMS Scaffolds for Extrahepatic Islet Transplantation. Cell Transplant. 22, 1123–1135 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao J, Crapo PM & Wang Y Macroporous elastomeric scaffolds with extensive micropores for soft tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 12, 917–925 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brady AC et al. Proangiogenic hydrogels within macroporous scaffolds enhance islet engraftment in an extrahepatic site. Tissue Eng. - Part A 19, 2544–2552 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smink AM et al. The Efficacy of a Prevascularized, Retrievable Poly(D,L,-lactide-co-∈-caprolactone) Subcutaneous Scaffold as Transplantation Site for Pancreatic Islets. Transplantation 101, e112 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris LD, Kim B-S & Mooney DJ Open pore biodegradable matrices formed with gas foaming. (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu JMH et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 delivery from microporous scaffolds decreases inflammation post-implant and enhances function of transplanted islets. Biomaterials 80, 11–19 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naficy S, Dehghani F, Chew YV, Hawthorne WJ & Le TYL Engineering a Porous Hydrogel-Based Device for Cell Transplantation. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 3, 1986–1994 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kosoff David, Yu Jiaquan, Suresh Vikram, Beebe J, D. & Lang M, J. Surface topography and hydrophilicity regulate macrophage phenotype in milled microfluidic systems. Lab Chip 18, 3011–3017 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abaricia JO et al. Control of innate immune response by biomaterial surface topography, energy, and stiffness. Acta Biomater. 133, 58–73 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buitinga M et al. Micro-fabricated scaffolds lead to efficient remission of diabetes in mice. Biomaterials 135, 10–22 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buitinga M et al. Microwell Scaffolds for the Extrahepatic Transplantation of Islets of Langerhans. PLoS One 8, e64772 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Espona-Noguera A et al. Review of advanced hydrogel-based cell encapsulation systems for insulin delivery in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pharmaceutics vol. 11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dimitrioglou N, Kanelli M, Papageorgiou E, Karatzas T & Hatziavramidis D Paving the way for successful islet encapsulation. Drug Discovery Today vol. 24 737–748 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Omer A et al. Long-term normoglycemia in rats receiving transplants with encapsulated islets. Transplantation 79, 52–58 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duvivier-Kali VF, Omer A, Parent RJ, O’Neil JJ & Weir GC Complete Protection of Islets Against Allorejection and Autoimmunity by a Simple Barium-Alginate Membrane. Diabetes 50, 1698–1705 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song S & Roy S Progress and challenges in macroencapsulation approaches for type 1 diabetes (T1D) treatment: Cells, biomaterials, and devices. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 113, 1381–1402 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhi ZL, Kerby A, King AJF, Jones PM & Pickup JC Nano-scale encapsulation enhances allograft survival and function of islets transplanted in a mouse model of diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 1081–1090 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhi ZL, Kerby A, King AJF, Jones PM & Pickup JC Nano-scale encapsulation enhances allograft survival and function of islets transplanted in a mouse model of diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 1081–1090 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Song S & Roy S Progress and challenges in macroencapsulation approaches for type 1 diabetes (T1D) treatment: Cells, biomaterials, and devices. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 113, 1381–1402 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang X et al. A nanofibrous encapsulation device for safe delivery of insulin-producing cells to treat type 1 diabetes. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, 4601 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coronel MM, Geusz R & Stabler CL Mitigating hypoxic stress on pancreatic islets via in situ oxygen generating biomaterial. Biomaterials 129, 139–151 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Weaver JD et al. Design of a vascularized synthetic poly(ethylene glycol) macroencapsulation device for islet transplantation. Biomaterials 172, 54–65 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Leukers B et al. Hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering made by 3D printing. in Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine vol. 16 1121–1124 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oladapo BI, Zahedi SA & Adeoye AOM 3D printing of bone scaffolds with hybrid biomaterials. Compos. Part B Eng. 158, 428–436 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gao Q et al. 3D printing of complex GelMA-based scaffolds with nanoclay. Biofabrication 11, 035006 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Farina M et al. Transcutaneously refillable, 3D-printed biopolymeric encapsulation system for the transplantation of endocrine cells. Biomaterials 177, 125–138 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Farina M et al. 3D Printed Vascularized Device for Subcutaneous Transplantation of Human Islets. Biotechnol. J. 12, (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lei Dong et al. 3D printing of biomimetic vasculature for tissue regeneration. Mater. Horizons 6, 1197–1206 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Melchels FPW et al. Additive manufacturing of tissues and organs. Prog. Polym. Sci. 37, 1079–1104 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chiu Y-C et al. The role of pore size on vascularization and tissue remodeling in PEG hydrogels. Biomaterials 32, 6045–6051 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lovett M, Lee K, Edwards A & Kaplan DL Vascularization strategies for tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering - Part B: Reviews vol. 15 353–370 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klenke FM et al. Impact of pore size on the vascularization and osseointegration of ceramic bone substitutesin vivo. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 85A, 777–786 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kuss MA et al. Prevascularization of 3D printed bone scaffolds by bioactive hydrogels and cell co-culture. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part B Appl. Biomater. 106, 1788–1798 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Liu X et al. Vascularization of Natural and Synthetic Bone Scaffolds. Cell Transplant. 27, 1269–1280 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rouwkema J, Rivron NC & van Blitterswijk CA Vascularization in tissue engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 26, 434–441 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moya ML, Hsu Y-H, Lee AP, Hughes CCW & George SC In vitro perfused human capillary networks. Tissue Eng. Part C. Methods 19, 730–7 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen X et al. Prevascularization of a Fibrin-Based Tissue Construct Accelerates the Formation of Functional Anastomosis with Host Vasculature. Tissue Eng. Part A 15, 1363–1371 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Costa-Almeida R et al. Fibroblast-Endothelial Partners for Vascularization Strategies in Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part A 21, 1055 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Newman AC, Nakatsu MN, Chou W, Gershon PD & Hughes CCW The requirement for fibroblasts in angiogenesis: Fibroblast-derived matrix proteins are essential for endothelial cell lumen formation. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 3791–3800 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meyer W et al. Soft Polymers for Building up Small and Smallest Blood Supplying Systems by Stereolithography. J. Funct. Biomater. 3, 257–268 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bertassoni LE et al. Hydrogel bioprinted microchannel networks for vascularization of tissue engineering constructs. Lab Chip 14, 2202–2211 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jia W et al. Direct 3D bioprinting of perfusable vascular constructs using a blend bioink. Biomaterials 106, 58–68 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gao Q et al. 3D Bioprinting of Vessel-like Structures with Multilevel Fluidic Channels. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 3, 399–408 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Noor N et al. 3D Printing of Personalized Thick and Perfusable Cardiac Patches and Hearts. Adv. Sci. 6, 1900344 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hospodiuk M et al. Sprouting angiogenesis in engineered pseudo islets. Biofabrication 10, 035003 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dionne KE, Colton CK & Lyarmush M Effect of Hypoxia on Insulin Secretion by Isolated Rat and Canine Islets of Langerhans. Diabetes 42, 12–21 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.De Groot M et al. Response of Encapsulated Rat Pancreatic Islets to Hypoxia. Cell Transplant. 12, 867–875 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thomas F et al. A tripartite anoikis-like mechanism causes early isolated islet apoptosis. Surgery 130, 333–338 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Barkai U, Rotem A & de Vos P Survival of encapsulated islets: More than a membrane story. World J. Transplant. 6, 69 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Davis NE et al. Enhanced function of pancreatic islets co-encapsulated with ECM proteins and mesenchymal stromal cells in a silk hydrogel. Biomaterials 33, 6691–6697 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Daoud J, Petropavlovskaia M, Rosenberg L & Tabrizian M The effect of extracellular matrix components on the preservation of human islet function in vitro. Biomaterials 31, 1676–1682 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jiang K et al. 3-D physiomimetic extracellular matrix hydrogels provide a supportive microenvironment for rodent and human islet culture. Biomaterials 198, 37–48 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pati F et al. Printing three-dimensional tissue analogues with decellularized extracellular matrix bioink. Nat. Commun. 2014 51 5, 1–11 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kim BS et al. 3D cell printing of in vitro stabilized skin model and in vivo pre-vascularized skin patch using tissue-specific extracellular matrix bioink: A step towards advanced skin tissue engineering. Biomaterials 168, 38–53 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Liu X et al. Development of a Coaxial 3D Printing Platform for Biofabrication of Implantable Islet-Containing Constructs. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hu S et al. An immune regulatory 3D-printed alginate-pectin construct for immunoisolation of insulin producing β-cells. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 123, 112009 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kooptiwut S et al. Estradiol Prevents High Glucose-Induced β-cell Apoptosis by Decreased BTG2 Expression. Sci. Rep. 8, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.JL C et al. 17beta-Estradiol protects isolated human pancreatic islets against proinflammatory cytokine-induced cell death: molecular mechanisms and islet functionality. Transplantation 74, 1252–1259 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dang TT et al. Enhanced function of immuno-isolated islets in diabetes therapy by co-encapsulation with an anti-inflammatory drug. Biomaterials 34, 5792–5801 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wang Y et al. Vitamin D induces autophagy of pancreatic β-cells and enhances insulin secretion. Mol. Med. Rep. 14, 2644–2650 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.AW F, Y L, K J, P B & CL S Local delivery of fingolimod from three-dimensional scaffolds impacts islet graft efficacy and microenvironment in a murine diabetic model. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 12, 393–404 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gaharwar AK et al. Amphiphilic Beads as Depots for Sustained Drug Release Integrated into Fibrillar Scaffolds. J. Control. Release 187, 66 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Fan Y, Zheng X, Ali Y, Berggren P-O & Loo SCJ Local release of rapamycin by microparticles delays islet rejection within the anterior chamber of the eye. Sci. Reports 2019 91 9, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Pathak S et al. Single synchronous delivery of fk506-loaded polymeric microspheres with pancreatic islets for the successful treatment of streptozocin-induced diabetes in mice. Drug Deliv. 24, 1350–1359 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Batra L et al. Localized Immunomodulation with PD-L1 Results in Sustained Survival and Function of Allogeneic Islets without Chronic Immunosuppression. J. Immunol. 204, 2840–2851 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tarafder S et al. Micro-precise spatiotemporal delivery system embedded in 3D printing for complex tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 8, 025003 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Liu Y-Y et al. Dual drug spatiotemporal release from functional gradient scaffolds prepared using 3D bioprinting and electrospinning. Polym. Eng. Sci. 56, 170–177 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 120.Freeman FE et al. 3D bioprinting spatiotemporally defined patterns of growth factors to tightly control tissue regeneration. Sci. Adv. 6, 5093–5107 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Aki D et al. 3D printing of PVA/hexagonal boron nitride/bacterial cellulose composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Des. 196, 109094 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 122.Saenz Del Burgo L et al. 3D Printed porous polyamide macrocapsule combined with alginate microcapsules for safer cell-based therapies. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mirdamadi E, Tashman JW, Shiwarski DJ, Palchesko RN & Feinberg AW FRESH 3D Bioprinting a Full-Size Model of the Human Heart. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 6, 6453–6459 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lee A et al. 3D bioprinting of collagen to rebuild components of the human heart. Science (80-. ). 365, 482–487 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang Y et al. 3D printed collagen structures at low concentrations supported by jammed microgels. Bioprinting 21, (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 126.O’Bryan CS et al. Self-assembled micro-organogels for 3D printing silicone structures. Sci. Adv. 3, (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Skylar-Scott MA, Mueller J, Visser CW & Lewis JA Voxelated soft matter via multimaterial multinozzle 3D printing. Nature 575, 330–335 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Liu W et al. Rapid Continuous Multimaterial Extrusion Bioprinting. Adv. Mater. 29, 1604630 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Paez-Mayorga J et al. Neovascularized implantable cell homing encapsulation platform with tunable local immunosuppressant delivery for allogeneic cell transplantation. Biomaterials 257, 120232 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Paez-Mayorga J et al. Enhanced In Vivo Vascularization of 3D-Printed Cell Encapsulation Device Using Platelet-Rich Plasma and Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 9, 2000670 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang LH et al. A bioinspired scaffold for rapid oxygenation of cell encapsulation systems. Nat. Commun. 2021 121 12, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Witowski J et al. From ideas to long-term studies: 3D printing clinical trials review. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 13, 1473–1478 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wu ZY et al. Magnetic resonance imaging based 3-dimensional printed breast surgical guide for breast-conserving surgery in ductal carcinoma in situ: a clinical trial. Sci. Reports 2020 101 10, 1–6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sekar MP et al. Current standards and ethical landscape of engineered tissues—3D bioprinting perspective. J. Tissue Eng. 12, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Ricles LM, Coburn JC, Di Prima M & Oh SS Regulating 3D-printed medical products. Sci. Transl. Med. 10, 6521 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.United States Food and Drug Administration. Discussion Paper: 3D Printing Medical Devices at the Point of Care. (2021).

- 137.HENRY RR et al. Initial Clinical Evaluation of VC-01TM Combination Product—A Stem Cell–Derived Islet Replacement for Type 1 Diabetes (T1D). Diabetes 67, (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 138.KEYMEULEN B et al. 196-LB: Stem Cell–Derived Islet Replacement Therapy (VC-02) Demonstrates Production of C-Peptide in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) and Hypoglycemia Unawareness. Diabetes 70, (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 139.Shapiro AMJ et al. Insulin expression and C-peptide in type 1 diabetes subjects implanted with stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cells in an encapsulation device. Cell Reports Med. 2, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]