Abstract

While most research on attentional templates focuses on how attention can be guided toward targets, a growing body of research has been examining our ability to guide attention away from distractors using negative templates. A recent report showed larger reaction time benefits from negative templates during a difficult search task compared to an easy search task. However, it remains unclear what shifts in attentional processing led to these differences in reaction time benefits. In the current study, we tested the predictions of enhanced guidance and rapid rejection as potential explanations for the differential impact of negative templates based on search difficulty. In Experiment 1, we replicated the larger benefits from negative templates in a within-subjects design. In Experiment 2, we use eye tracking to measure the proportion of fixations directed towards target-colored distractors as an index of enhanced guidance and the dwell time on distractors as a measure of rapid rejection. We found more attentional guidance from negative templates in the difficult search condition. In addition, we found larger benefits of rapid rejection from negative templates in the difficult search condition. While we typically focus on templates as a way of guiding attention, these results highlight another key role played by attentional templates: rapid distractor rejection.

Keywords: Attention, Visual Search, Attentional Templates, Negative Templates, Templates for Rejection

Introduction

Visual attention can be guided by information from attentional templates held in working memory (Carlisle et al., 2011; Carlisle & Woodman, 2011; Woodman, Carlisle, & Reinhart, 2013; Olivers et al., 2011; Wolfe; 2021). Previous research has focused on how target features, maintained in working memory as positive attentional templates, can be used to prioritize matching items in the environment (Carlisle et al., 2011; Wolfe, 1994; Desimone & Duncan, 1995). However, there is an increasing interest in examining whether we can use distractor features to create negative templates to help guide attention away from known distractors (Arita, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2012; Becker et al., 2016; Beck & Hollingworth, 2016; Beck, Luck, & Hollingworth, 2018; Berggren & Eimer, 2021; Cunningham & Egeth, 2016; Carlisle, 2019; de Vries, et al., 2019; Gong, et al., 2016; Moher & Egeth, 2012; Rajsic, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2020; Reeder, Olivers, & Pollmann, 2017; Reeder, et al., 2018; Tanda & Kawahara, 2019; Woodman & Luck, 2007; Zhang, Gaspelin, & Carlisle 2020).

In the first attempt to directly examine this possibility, Arita and colleagues (2012) had participants search for a shape defined target (Landolt-C with gap at top or bottom) in 12-item search arrays where all the items in one visual hemifield were presented in the same color. Color cues preceding the search array could indicate the target color (positive cue), the distractor color (negative cue), or a stimulus color that would not be presented on the upcoming search array (neutral cue). Participants could perform the search for the shape-defined target without using the color cues, but using either the positive or negative cue would reduce the effective set size in half, leaving only items of one color as potential targets. Importantly, the specific color cued changed on each trial, so participants needed to use active control based on templates maintained in working memory. Consistent with previous findings, participants found the target faster following positive cues compared to neutral cues, demonstrating positive attentional templates can guide attention toward matching stimuli. Critically, participants also found the target faster following negative cues compared to neutral cues, suggesting that negative templates created from distractor colors can be used to guide attention away from matching distractors. While significant, these negative cue reaction time (RT) benefits were not as large as positive cue RT benefits. Positive and negative cue RT benefits in set size 12 arrays were consistent across cue-to-search SOAs varying from 100 ms to 1250 ms, suggesting both positive and negative templates can be configured quickly (but see Tanda & Kawahara, 2019, for evidence that negative templates take longer). When Arita and colleagues (2012) manipulated search set size (12, 8, 4), both positive and negative cue RT benefits decreased as search set sizes decreased, presumably because the search task became easier to complete even without using the color cues when the set sizes decreased. At set size 4, RT benefits remained significant for positive cues even, but benefits of negative cues were absent, in line with the generally larger benefits for positive cues. Together, these findings highlight that attention can benefit from positive templates that can guide attention towards potential targets, and negative templates that can guide attention away from known distractors.

Follow-up studies with similar designs have replicated benefits from negative cues both in terms of RT (Carlisle & Nitka, 2019; Reeder, Olivers, & Pollmann, 2017; Zhang, Gaspelin, & Luck, 2020) and eye movement benefits (Zhang & Carlisle, under review). More importantly, Individual differences have been shown, indicating some participants may not use the negative cues (Becker, Hemsteger, & Peltier, 2015; Beck & Hollingworth, 2015), or may only use them when the task cannot be completed using an easier method (Rajsic, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2020). Studies supporting negative cue use have also highlighted important differences between the attentional impact of positive and negative templates. Negative templates consistently lead to weaker behavioral benefits than positive templates, even when both cues are equally informative (Arita, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2012; Carlisle & Nitka, 201; Zhang, Gaspelin, & Carlisle, 2020). In addition, negative templates benefits arise later during search than positive templates. An N2pc index of covert attentional deployments toward potential targets were ~50 ms slower for negative than positive cues (Carlisle & Nitka, 2019). Similar delays were found in a letter probe study (Zhang, Gaspelin, & Carlisle, 2020) where letters were occasionally presented on top of visual search items during visual search to gain a snapshot of attention at different times (25ms, 100ms, 250ms, 400ms). Negative template benefits emerged beginning with probes at 100ms, with participants reporting more letter probes appearing on potential targets compared to distractors. But the positive cue benefits arose earlier, beginning with the 25ms probes, highlighting the clear timing differences between negative and positive templates.

Examinations from brain recordings have found clear distinctions in the neural mechanisms underlying positive and negative templates (Carlisle & Nitka, 2019; Reeder, Olivers, & Pollmann, 2017; Reeder, et al., 2018). For example, an fMRI study by Reeder and colleagues (2017) found negative cues led to decreased activation in the early visual cortex compared to neutral cues, whereas positive cues led to increased activation in overlapping regions. Utilizing EEG, De Vries and colleagues (2019) showed increased frontal theta oscillations following negative cues compared to positive cues, suggesting the usage of negative templates requires stronger cognitive control than positive templates. The differences in neural mechanisms emphasize they are separate mechanisms of attentional control, which may help explain why positive and negative templates have different behavioral effects on attention.

In spite of the large number of studies supporting the idea of negative templates, there have also been a number of studies that do not support the mechanism of negative templates. These studies have either failed to find evidence for benefits of negative templates (Berggren & Eimer, 2021; Cunningham & Egeth, 2016) or proposed alternative explanations for negative cue benefits (Becker, Hemsteger, & Peltier, 2015; Beck & Hollingworth, 2015; Moher & Egeth, 2012). The mixed results in the literature have led some to question whether negative templates exist (Chelazzi, et al., 2019). Resolving this controversy is important for our understanding of top-down attentional control. Is top-down control solely a mechanism of enhancement, or can we use top-down control to suppress as well?

To address this question, we need to explore why some studies seem to show clear support for negative templates while others do not and explain a clear picture of the attentional processes involved. Upon examination of specific designs of studies, researchers have proposed certain differences in the design of search tasks across studies may have lead to differences in the use of negative templates between studies (Conci et al., 2019; Gong, Yang, & Li, 2015; Zhang & Carlisle, under review; Tanda & Kawahara, 2019). Systematic manipulation of task-related differences between previous studies that support and fail to support negative templates may help resolve the conflicting findings in the literature (Conci et al., 2019; Zhang & Carlisle, under review; Tanda & Kawahara, 2019).

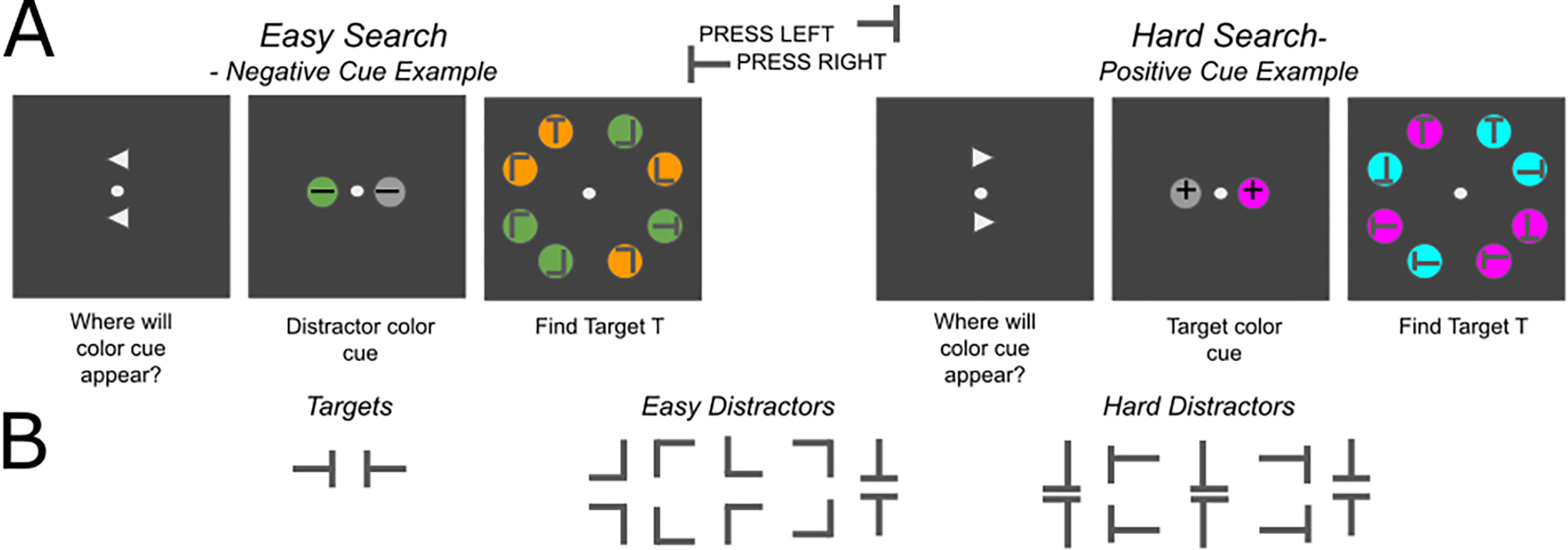

One important difference between tasks may be search difficulty. Conci and colleagues (2019) hypothesized that the efficient use of negative templates might depend on search difficulty, based on their observation that negative cue benefits were only found in difficult search tasks where the average reaction time was long. To directly investigate their hypothesis, they manipulated search difficulty across participants. All participants performed a search for a shape-defined target preceded by positive, negative or neutral color cues. Each search array contained circles of two colors with letters superimposed on those circles (Figure 1a). Critically, one group of participants performed an easy search task, in which they looked for a target letter ‘T’ among ‘L’ distractors. The other group of participants performed a difficult search task where the offset at the junction of ‘L’ was manipulated, so those ‘L’s became more perceptually similar to the target letter ‘T’ (Figure 1b). Consistent with their hypothesis that negative cues might only be used efficiently in difficult search tasks, RT benefits of negative cues were only found in the difficult search task, but not in the easy search task.

Figure 1.

Trial sequences based on the design of Conci and colleagues (2019). A) Example trial sequence for a negative cue easy search and positive cue hard search tasks. B) Examples of target items and distractor items for each and hard search trials. Stimuli are representative but not to scale.

The work of Conci and colleagues presents an important possible explanation for the discrepant results in the previous literature. But what actually changed in terms of attention between the easy and difficult search task? While the RT differences allow us to determine that something was different, this difference could be related to changes in multiple stages of cognitive processing before response. The previous literature on attentional suppression highlights two main possibilities: changes in attentional guidance and changes in distractor rejection.

First, it is possible that participants utilized the negative cue to more strongly bias attention toward potential targets in the difficult search compared to the easy search task, which we will call the enhanced guidance hypothesis. Enhanced guidance could occur in multiple ways. Conci and colleagues (2019) proposed that the increased RT benefits in the difficult search condition were driven by an enhancement of guidance resulting from participants generating a more refined template representation of guiding features in the difficult task compared to the easy task. Such an adjustment of attentional templates based on task settings has been demonstrated in the previous literature when distractor features closely resemble target features. When targets and distractors are very similar, attentional templates are either sharpened or shifted away from distractor features to maintain effective guidance (Geng, DiQuattro, & Helm, 2017; Xinger & Geng, 2019). However, in Conci and colleagues’ design of search tasks, the target color was quite distinct from distractor color (red vs. blue), suggesting that even an unrefined representation of the cued color should be enough to lead to efficient attentional processing. Another possible cause of enhanced guidance comes from Carlisle & Woodman (2011). They found an increase in guidance toward memory-matching items when a WM item becomes more relevant for a search task. They manipulated the relevance of the WM item by making it 20%, 50%, or 80% valid across conditions. When the WM item became more predictive of the upcoming search target, there were greater benefits when the WM item appeared as a target during search and greater costs when the WM item appeared as a distractor. This suggests people can turn up the guidance for a positive template based on task relevance (Carlisle, 2019). A similar adjustment in the amount of guidance from negative templates could potentially explain the difference between the easy and difficult conditions in the Conci study (2019), also supporting the enhanced guidance hypothesis. While it is difficult to test the enhanced guidance hypothesis using RTs, eye tracking should lead to a clear evaluation of the hypothesis. Eye-tracking is a more accurate measure of attentional deployments than RT or accuracy alone (Hollingworth & Bahle, 2019; Bahle, et al., 2018; 2019) because it helps to uncover differences in multiple stages of attentional processings between conditions (Lu et al., 2017; Xinger, Hanks, & Geng, 2021). The enhanced guidance hypothesis predicts more selective processing in the difficult search condition, leading to a higher proportion of fixations on potential targets vs. distractors in the difficult condition compared to the easy condition.

The second possible shift in attentional processing between the easy and the difficult search tasks relates to distractor rejection (Geng, 2014; Geng & DiQuattro, 2010). Recent work from our lab has shown that positive and negative templates not only actively guide visual attention, but also benefit search by quickly rejecting fixated distractors (Zhang & Carlisle, under review). In a cued search task, we recorded participants’ eye movements during search following positive, negative, or neutral cues. When participants fixated on distractors, the dwell time was shorter in negative and positive cue conditions than the neutral cue condition, suggesting that participants quickly rejected fixated distractors following positive and negative cues. This leads to a second possible hypothesized mechanism, the rapid rejection hypothesis. The rapid rejection hypothesis is difficult to assess using RT alone, but leads to a clear prediction of reduced dwell time on distractors when eye movements are monitored, with a greater benefit from rapid rejection in the difficult search condition.

Our two potential hypotheses, enhanced guidance and rapid rejection, map on to a broader distinction in theoretical mechanisms for distractor suppression within the literature. Firstly, there is an active suppression mechanism that can prevent attention from being captured by distractors through actively guiding attention away from distractors (Gaspelin & Luck., 2018; Zhang & Carlisle, under review). Additionally, there can be a reactive suppression mechanism being exerted to quickly reject distractors when they accidentally capture attention (Geng & DiQuattro, 2010; Geng, 2014). Importantly, these two distractor suppression mechanisms are not mutually exclusive (Geng & DiQuattro, 2010), so both could be contributing to behavioral benefits in a task.

The current work uses eye tracking to examine the enhanced guidance and rapid rejection hypothesis as potential mechanisms underlying the difference in RT benefits between difficult and easy search tasks (Conci, et al., 2019). Importantly, we wanted to focus on the benefits in finding the target driven by the color cue. As a reminder, participants can find the shape-defined target without using the color cue. Therefore, for all our main measures, we compute the attentional benefit (informative cues vs. neutral cue) to isolate the specific attentional influences of the positive and negative templates.

We chose to use a within-subjects design to ensure our results could not be driven by between-subjects differences. However, we were concerned that within-subjects manipulation of task difficulty could potentially interfere with the differences in negative cue benefits shown by Conci and colleagues in their between subjects design. Given that previous research has shown participants may ignore a negative cue when an easier strategy is available (Rajsic, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2020), we were concerned that exposure to the easy search condition might lead participants to develop a strategy of ignoring the negative cue which could carry over to the difficult search task. To determine if negative cue use would be set based on the condition, we had half of participants perform easy search trials first while the other half perform difficult search trials first. Then we include trial order into our analysis to examine its effect on negative cue uses.

To preview our results, Experiment 1 replicated the difference between easy and difficult search in a within-subjects design, even though participants switched between easy and difficult search tasks in the middle of the block. This suggested the attentional changes between easy and difficult search trials were flexible. After establishing the changes in negative cue benefits could be observed in a within-subjects design, in Experiment 2 we incorporated eye-tracking techniques to directly assess the enhanced guidance and rapid rejection hypotheses. To preview the results from Experiment 2, we found support for both the enhanced guidance hypothesis and the rapid rejection hypothesis. Fixation analyses showed enhanced guidance effects by positive and negative templates in difficult trials compared to easy trials. In addition, dwell time analyses showed the benefits of rapid distractor rejection by both positive and negative cues were enhanced in the difficult condition relative to the easy condition. These findings suggest the difference in behavioral benefits of attentional templates between easy and difficult search trials was driven by the difference in both active guidance and distractor rejection effects from attentional templates. This demonstrates eye tracking is an important tool for examining the mechanisms underlying negative cue benefits when exploring the conflicting findings in the previous literature.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 was conducted with an attempt to replicate the differences in negative cue RT benefits from Conci, et al. (2019) in a within-subjects design. We matched our experimental design to Conci, et al. (2019) as closely as possible. Given that we wanted to utilize a within-subjects eye tracking design to gain the power to find within-subjects comparisons in eye movement analyses, the main aim of this first experiment was to ensure the shifts driven by easy and difficult search could be flexibly changed within subjects. We manipulated the order of easy and difficult trials within each block across participants, where half of the participants completed easy trials first whereas the other half of participants completed difficult trials first. If the changes in negative cue benefits shown by Conci and colleagues (2019) are due to flexible shifts, we expect to see no order effects and replicate larger benefits from negative cues in the difficult search trials. However, if participants develop stable strategies that are difficult to change, we expect to see an interaction of negative cue benefits and task order.

Methods

Participants

24 undergraduates from Lehigh University (Mean Age = 19.33, SD = 1.13, 11 females) provided informed consent and participated in Experiment 1 for course credit. Our sample size was determined on the basis of a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.05) obtained in previous research from our lab (Carlisle & Nitka, 2019), and was larger than the sample size of 16 from Conci and colleagues (2019). Our sample was selected to achieve over 95% power to detect the presence of RT benefits following negative cues. All participants reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and normal color perception. Procedures were approved by the Lehigh University IRB.

Stimuli

Stimuli were matched to Conci, et al., (2019; see Figure 1). Stimuli were presented using PsychToolbox (Brainard, 1997) and displayed on an LED screen with a black background that was placed at a viewing distance of approximately 60 cm. Location cues were triangles (0.7°), placed 0.5° above and below the central fixation. Color cues were filled color circles (r = 1.0°), presented at the center of the screen. Positive cues were indicated by a ‘+’ at the center of the colored circle, negative cues were indicated by a ‘−’, and neutral cues were indicated by a ‘o’. Search items were two groups of 6 filled color circles (r = 1.0°) with letters (T or L, 0.8° × 0.8°, width = 0.1°) superimposed on them. Differently colored search items were spatially intermixed in the display. The search target contained a letter T that was rotated 90° either to the left or the right. One distractor contained a letter T that was rotated either 0° or 180°. The target and the distractor that contained letter ‘T’ were always presented at opposite hemifield. The rest of the search items contained letter ‘L’s that were rotated by 0°, 90°, 180°, or 270°. Search items were presented at the outline of an imaginary circle (r = 5.5°) that centered on the fixation. Colors of the search items were selected randomly from a set of 8 colors (red, green, blue, magenta, orange, cyan, brown and purple) on each trial.

Procedures

Experimental procedures were matched to Conci, et al. (2019), but adapted to a within-subject design. Each trial started with two location cues being presented for 250 ms, pointing to the location of the upcoming color cue. After a blank screen was presented for 200–300 ms, a color cue and a grey filled circle were presented at two sides of the screen for 250 ms. The color cue could either be a positive, negative or neutral cue, and the meaning of the cue was manipulated across blocks. After a delay period with a central fixation for 400–600 ms, a search display was presented until participants made a response, or a maximum of 2500 ms. Participants were instructed to find the target item containing a letter T and reported whether the stem pointed to the left or right side of the screen by pressing left or right trigger buttons on a gamepad controller. Each trial ended with a blank interval, presented for a random period of 500 to 600 msec.

The two within-subject independent variables are cue type and task difficulty. Participants received positive, negative or neutral cues in three separate blocks (order randomized). Positive cues always matched the color of the target item whereas negative cues always matched the distractor color (non-target color). The color of neutral cues never appeared in the search array. Task difficulty was manipulated as in Conci et al (2017). In easy trials, participants searched for a letter ‘T’ among ‘L’s. In difficult trials, nontarget ‘L’s were presented with an offset, so they became more similar to the target letter ‘T’.

We also had a between-subject variable of task order. Half of the participants completed easy trials first within a block, whereas the other half of participants completed difficult trials first. Participants were shown examples that matched the difficulty of the task at the beginning of their block, and completed practice trials with that level of difficulty. Before beginning the experimental block, they were shown images on a paper indicating the easy and difficult trials and instructed “Regardless of which distractors appear, your task is the same- find the single target T with the stem facing the right or left and report the location the stem faces.”. The transition between easy and difficult trials happened without any additional instruction after one of the short breaks. In analyses, we include trial order as a between-subject variable to test if negative cue effects can be changed flexibly or are driven by stable strategies. For example, if participants were adapted to use refined feature representation to guide attention in the difficult trial, would such a strategy be transferred to following easy trials? If so, we would expect to find an interaction of task order and negative cue benefits.

At the beginning of each block, participants were instructed with the meaning of the cue and were explicitly told that both positive and negative cues can help eliminate 6 search items in the array. Then they completed a practice block containing 10 trials and finally the experimental block containing 100 trials. Participants had a 15-second break after every 25 trials.

Accuracy data are reported in Table 1, and inferential statistics on accuracy are reported in the online supplement. Accuracy data did not show any speed accuracy tradeoffs. RT values are depicted in Figure 2a, and inferential statistics on the raw RTs are available in the online supplement. Our analyses focused on the benefits for informative cues vs. neutral cues.

Table 1.

Mean percent accuracy and standard deviation results based on condition. Statistical analyses of accuracy are available in an online supplement at placeholder OSF link.

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Positive Easy | 95.7 (6.7) | 96.4 (4.0) |

| Negative Easy | 94.6 (4.7) | 95.5 (4.5) |

| Neutral Easy | 96.8 (2.2) | 95.8 (4.1) |

|

| ||

| Positive Difficult | 92.5 (6.1) | 93.4 (5.8) |

| Negative Difficult | 87.5 (9.7) | 89.5 (7.7) |

| Neutral Difficult | 84.8 (8.2) | 82.4 (6.3) |

Figure 2.

RTs and RT benefits for informative cues. A) RT for Experiment 1. B) RT for Experiment 2. C) RT benefits for informative negative and positive cues compared to neutral cues for Experiment 1. D) RT benefits for informative negative and positive cues compared to neutral cues for Experiment 2. Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Results

RT benefits

To directly compare cueing benefits of negative and positive cues, RT benefits for informative cues versus neutral cues were computed (Figure 2c). For example, negative cue benefits in the easy condition were computed as easy neutral RT- easy negative RT. A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with factors of cue type and task difficulty. Based on RT analyses (see online supplement), trial order did not lead to changes in strategies, so the between-subject variable of trial order was excluded from RT related analyses. Positive cues led to larger RT benefits than negative cues, F(1, 23)=29.62, p <.001, ηp2 =.56. Cueing benefits in the difficult condition were larger than in the easy condition, F(1, 23)=11.57, p =.002, ηp2 =.34. No significant interaction was found.

Discussion

Replicating Conci et al (2019), in Experiment 1 we found larger behavioral benefits of negative cues and positive cues in difficult trials than easy trials. Replication of this key finding with a within-subject design helps rule out the possibility that the difference between easy and difficult conditions was driven by individual differences or other between-experiment differences. Additionally, comparisons of trial order between easy first and difficult first groups showed that task order did not influence benefits of negative cues, suggesting the within-subjects design was just as capable of showing the differential effectiveness of the negative cue as the original Conci, et al. (2019) between-subjects design.

Experiment 2

In order to test how task difficulty modulates the effects of negative templates, in Experiment 2 we incorporated an eye-tracking device to seek for evidence of the enhanced guidance hypothesis and the rapid rejection hypothesis. Recent research has highlighted the utility of the more direct nature of eye tracking compared to reaction time when examining attentional processes (Hollingworth & Bahle, 2019; Bahle, et al., 2018; Bahle & Hollingworth, 2019). If there is stronger attentional guidance by negative templates in the difficult condition than the easy condition, we expect to see a larger proportion of fixations being guided toward target-colored distractors following negative cues and positive cues in difficult trials compared to easy trials. In addition, more efficient distractor rejection can also aid visual search performance (Geng & DiQuattro, 2010). If the rapid rejection effect of attentional templates is enhanced in difficult trials, we expect to see greater benefits in difficult trials, indicated by shorter dwell time on distractor color items following negative cues and positive cues compared to neutral cues.

Methods

A new group of 22 participants provided informed consent and completed Experiment 2. One participant had an accuracy lower than 2.5 SD from the group average in negative condition, and was removed from further analysis. This left 21 participants in the final analysis (Mean Age = 19.29, SD = 1.43, 17 females). Procedures were approved by the Lehigh University IRB. Methods were identical to those of Experiment 1 except for the following changes.

We modified the trial sequence to add a gaze contingent start to the search array presentation to ensure participants started searching from the fixation point. After the color cue presentation, a fixation was presented for a fixed 200 ms. Then a gaze-contingent fixation screen was presented with a black background, which required participants to maintain fixation continuously within a central circle region (1.6°) for 300 ms.

Finally, eye movements were recorded with an Eyelink 1000 eye tracker that has a sampling rate of 500 Hz. Saccades were defined by a combined velocity (> 35 °/s) and acceleration (> 9500 °/s) threshold. Gaze position was calibrated using a 5-point calibration/validation routine at the beginning of each block and any time when participants failed to meet gaze-contingent fixation criteria three times during a trial. For the fixation analyses, interest areas were circle regions (1.9°) around each search item.

Analyses

Behavioral analyses were matched to Experiments 1.

We focused our examination of the eye movements on the two key measures associated with the predictions of the enhanced guidance and rapid rejection hypotheses. We analyzed both whether attention was directed towards potential targets or distractors, and how long participants spent processing potential targets and distractors once they were fixated. Recent research suggested that fixations landing outside of item regions might still indicate guidance (Wolfe, 2021). To include those fixations into our analyses, we derive the nearest interest area1 of fixations from EyeLink Dataviewer software for both fixation and dwell time analyses. Such a methodology assigns each fixation to the nearest search item region in our study, providing a clear representation of where overt attention was directed during search. Enhanced attentional guidance of cues should lead to increased proportions of fixations landing on target-colored distractors. Therefore, we computed the proportions of fixations landing on target-colored distractors as an index of attentional guidance effects. Fixations on the actual target were excluded to ensure the effects were not driven by the target shape, isolating the guidance processes associated with the color cues. The chance level of fixations landing on target-colored distractors is 5/12 = 41.67%. When the proportion of fixations landing on target-colored distractors is higher than this chance level, this indicates attention is being guided toward potential targets.

The rapid rejection hypothesis predicted that items that are not in the target color should be rapidly rejected, with a greater benefit of rapid rejection in the difficult condition. To ensure we were only looking at the effect of color and not processing of the actual target, we did not include the actual target in this analysis. We computed the average dwell time per fixation on target-colored distractors and distractor (non-target-colored) items. The benefits of rapid rejection should be reflected as shorter dwell time on distractor items following positive and negative cues than neutral cues.

Accuracy data are reported in Table 1, and inferential statistics on accuracy are reported in the online supplement. Accuracy data did not show any speed accuracy tradeoffs. Raw RT values are depicted in Figure 2b, and inferential statistics on the raw RTs are available in the online supplement.

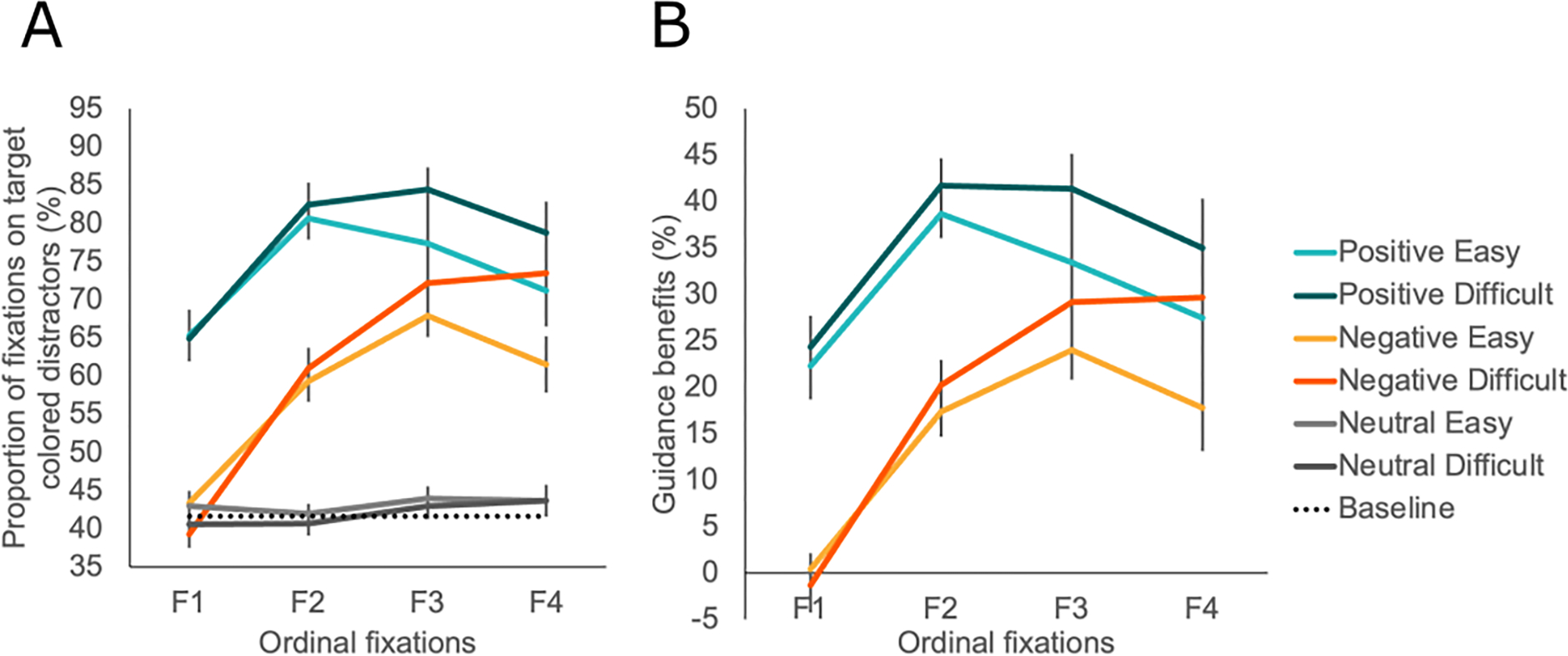

We analyzed the eye tracking data from the first four fixations, as on average searches ended after 4.4 fixations (positive: easy M = 3.4, difficult M = 3.8; negative: easy M = 4.1, difficult M = 4.6; neutral: easy M = 4.7, difficult M = 5.6). Fixation data depicting the proportion of fixations on target-colored distractors are shown in Figure 3a, and inferential statistics on these raw values are available in the online supplement. Our analyses focused on the RT and eye movement benefits for informative vs. neutral cues.

Figure 3.

A) Proportion of fixations on target-colored distractors for fixations 1–4 in Experiment 2. B) Guidance benefits for fixations 1–4. Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Results

RT benefits

RT benefits were computed as RT differences between informative cue (positive and negative) trials and neutral cue trials. A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with factors of cue type (negative, positive) and task difficulty (see Figure 2d). Positive cues led to larger RT benefits than negative cues, F(1, 20)=39.92, p <.001, ηp2 =.67. Cueing benefits in the difficult condition were larger than the easy condition, F(1, 20)=12.32, p =.001, ηp2 =.38. No significant interaction was found.

Guidance benefits

Guidance benefits were computed as the proportion of fixations landing on target-colored distractors in informative cues trials minus that in neutral cue trials to isolate the benefits derived from the informative color cues.

A repeated-measure ANOVA was conducted with factors of cue type (negative, positive), task difficulty (easy, difficult) and ordinal fixations (F1, F2, F3, F4) on guidance benefits. Figure 3b shows larger guidance benefits of positive cues than negative cues, F(1, 20)= 58.31, p <.001, ηp2 =.75. Guidance benefits were larger in difficult trials compared to easy trials, F(1, 20)= 6.26, p =.021, ηp2 =.24. Guidance benefits were larger for later fixations than early fixations, leading to a main effect of ordinal fixations, F(3, 60)= 18.87, p <.001, ηp2 =.49. Significant interactions were found between cue type and ordinal fixations, F(3, 60)= 10.01, p <.001, ηp2 =.33. No other significant main effects or interactions were found.

Given the interaction between cue type and ordinal fixation, we examined the effects at each fixation separately. Repeated-measure ANOVAs were conducted with factors of cue type (negative, positive) and task difficulty (easy, difficult) on guidance benefits for each of the first four fixations. For all fixations, the main effect of cue type was significant. Larger guidance benefits were found following positive cues compared to negative cues, F(1, 20)= 68.73, p <.001, ηp2 =.78; F(1, 20)= 65.83, p <.001, ηp2 =.77; F(1, 20)= 11.96, p =.002, ηp2 =.37; F(1, 20)= 4.97, p =.037, ηp2 =.20 for fixations 1–4, respectively. More importantly, for fourth fixations, guidance benefits were larger in difficult trials compared to easy trials, F(1, 20)= 6.21, p =.022, ηp2 =.20.

Overall, the main effect of task difficulty showed that the guidance benefits of informative cues were enhanced in difficult trials. When we examined each fixation, no significant guidance benefits for the difficult condition of positive or negative cues were found in fixation 1–3. In fourth fixations, however, guidance benefits were enhanced in difficult trials relative to easy trials, consistent with the enhanced guidance hypothesis. We will discuss this pattern more in the discussion.

Guidance benefits and RT benefits

To link eye tracking evidence of active guidance to behavioral outcomes, averaged guidance benefits across fixation 1–4 were correlated with RT benefits. Significant positive correlation between guidance benefits and corresponding RT benefits were found in difficult trials, negative, r(20) = .55, p = .010; positive, r(20) = .60, p = .004. In easy trials, no significant correlations were found, negative, r(20) = .25, p = .266; positive, r(20) = .19, p = .413. Correlation analyses indicated a stronger relationship between guidance benefits and RT benefits following positive and negative cues in difficult trials compared to easy trials.

While we found a significant overall main effect of task difficulty on guidance across fixations 1–4, our guidance analyses separated by ordinal fixation (see above) indicated the effect of difficulty was only significant on the fourth fixation. To ensure the relationship between guidance and RT was not driven solely by the fourth fixations, we averaged the guidance benefits across fixation 1–3 and computed the correlation with RT benefits. We found significant positive correlations between guidance benefits and corresponding RT benefits in difficult trials, negative, r(20) = .59, p = .005; positive, r(20) = .61, p = .003. In easy trials, significant correlations were found for negative cues, r(20) = .58, p = .006, but not for positive cues, r(20) = .24, p = .295. These relationships show the relationship between RT and guidance benefits is more global and not driven solely by the fourth fixation.

Dwell time

Before we focus on the dwell time benefits for distractors, we provide an overview of the raw dwell time effects for fixations on distractors and targets. To investigate how task difficulty shifts distractor and target processing following cues, we did analyses separately for distractor items (non-target-colored) and target-colored distractors. The rapid rejection hypothesis suggests there will be larger benefits from distractor rejection in the difficult compared to the easy condition.

A repeated-measures ANOVA with factors of cue type and task difficulty was conducted for dwell time on distractors. For neutral cues, these items should be processed as a potential target, but for informative positive and negative cues these items should be rapidly rejected. Dwell time on distractor items was longest following neutral cues, then negative cues and finally positive cues (Figure 5b), leading to a main effect of cue type, F(2, 40)= 60.26, p <.001; ηp2 =.75. Dwell time on distractor items was longer in the difficult condition than the easy condition, F(1, 20)= 44.47, p < .001; ηp2 =.69. Critically, a significant interaction of cue type and task difficulty was found, F(2, 40)= 7.69, p =.001; ηp2 =.28. Follow-up analyses to examine this interaction showed similar patterns of significance for easy and difficult conditions. In the easy condition, dwell time on distractor items following negative and positive cues were shorter compared to neutral cues [t (20) = −4.06, p = .002, d = 0.89; t (20) = −7.86, p < .001, d = 1.71], although negative cues led to longer dwell time on distractor items than positive cues, t (20) = 5.86, p < .001, d = 1.28. Similarly, in the difficult condition, both negative and positive cues led to shorter dwell time on distractor items compared with neutral cues [t (20) = −6.42, p < .001, d = 1.40; t (20) = −9.23, p < .001, d = 2.01], though the effect of negative cues was weaker than positive cues, t (20) = 5.09, p < .001, d = 1.11.

Figure 5.

Dwell time on (A) distractor items and (B) target-colored distractor items (e.g. potential targets) in Experiment 2. Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Next, we examined dwell time on target-colored distractors. These items should be processed as potential targets for all cue types. Figure 5b shows dwell time on target-colored distractors was longer in the difficult condition than the easy condition, F(1, 20)= 135.57, p < .001; ηp2 =.87. No other significant main effects or interactions were found.

Dwell time analyses revealed that both negative and positive cues benefit search by inhibiting processing of known distractors when attention is captured by those distractors (reactive suppression, see Geng, 2014). The rapid rejection of distractor items following positive and negative cues was consistently found across easy and difficult conditions, meaning that participants could quickly reject distractors when attention landed on them in both conditions.

Distractor Dwell Time Benefits

To directly examine whether the benefit of rapid distractor rejection was enhanced in difficult trials, dwell time benefits were computed as the difference in dwell time on distractor items between positive/negative cue conditions and the neutral cue condition. A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with variables of cue type and task difficulty. Dwell time benefits were larger for positive cues than negative cues, F(1, 20)= 38.07, p < .001; ηp2 =.66. Dwell time benefits were larger in difficult trials than easy trials, F(1, 20)= 15.52, p = .001; ηp2 =.44. Importantly, no significant interaction of cue type and task difficulty was found. Follow-up comparisons showed that for both positive and negative cues, dwell time benefits in difficult trials were larger than easy trials, [t (20) = 3.20, p = .004, d = 0.72; t (20) = 3.69, p = .001, d = 0.83, respectively].

One sample t-tests confirmed significant dwell time benefits following both positive and negative cues, in easy and difficult trials [Negative easy: t (20) = 4.06, p < .001, d = 0.89; Negative difficult: t (20) = 6.42, p < .001, d = 1.40; Positive easy: t (20) = 7.86, p < .001, d = 1.71; Positive difficult: t (20) = 9.23, p < .001, d = 2.01], suggesting rapid rejections of known distractors following information cues consistently led to dwell time benefits. Together, results from dwell time benefits analyses were consistent with those from RT benefits analyses.

Relationship between Distractor Dwell Time benefits and RT Benefits

To link eye tracking evidence of rapid rejection to response outcomes, dwell time benefits were correlated with RT benefits. Dwell time benefits were positively correlated with RT benefits of positive cues in both easy and difficult conditions [Positive easy: r(20) = .53, p = .015; Positive difficult: r(20) = .62, p = .003]. For negative cues, however, the positive correlation between dwell time benefits and RT benefits was only found in the difficult condition, r(20) = .56, p = .008 but not the easy condition, r(20) = .29, p = .199. The lack of correlation between dwell time benefits and RT benefits of negative cues in easy trials helps to explain the weaker influence of cueing for the negative easy condition.

Saccadic latency

To examine effects of cueing and task difficulty on initial executions of saccades, a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted with factors of cue type, task difficulty, and landing position of initial saccades (distractor items, target-colored distractors). Initial saccades were faster in easy trials compared to difficult trials, leading to a main effect of task difficulty, F(1, 20)= 8.49, p = .009; ηp2 =.30. No other significant main effects or interactions were found.

Discussion

Replicating Experiment 1, we found RT benefits of both positive and negative cues increased in difficult trials compared to easy trials. Critically, Experiment 2 was designed to examine differences in attentional processing in the easy and difficult search conditions using eye tracking. The enhanced guidance hypothesis predicts the larger RT benefits in the difficult compared to the easy condition should be driven by a larger proportion of fixations directed towards potential targets in the difficult condition. In line with this hypothesis, we found larger guidance benefits in difficult trials compared to easy trials, suggesting positive and negative templates did have enhanced guidance effects in difficult trials. Correlation analyses further verified the relationship between enhanced guidance as shown in eye tracking data and behavioral outcomes by showing significant positive correlations between guidance benefits and RT benefits in difficult trials for both positive and negative cues. The lack of correlations in easy trials might suggest the guidance based on color was utilized less when searching for easy shape-defined targets. In line with all other research on negative templates (e.g., Arita, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2012), we also found consistently weaker benefits for the negative cues compared to the positive cues. In addition, we found evidence of the typically observed timing differences between negative and positive cues. While there were benefits for positive cues at the first fixation, benefits from negative cues only emerged at the second fixation replicating the delayed onset of negative cue benefits shown in multiple prior studies (Beck, Luck, & Hollingworth, 2018; Carlisle & Nitka, 2019; Zhang, Gaspelin, & Carlisle, 2020; Zhang & Carlisle, 2021).

The rapid rejection hypothesis predicted differences in dwell time benefits may explain the increased RT benefits from negative cues in the difficult search condition. Our results support this prediction. Following positive and negative cues, dwell time on distractor (non-target-colored) items was significantly decreased compared to neutral cue cases. This shows that when participants employed either a positive or negative template, they could rapidly reject distractors during search, leading to more efficient search performance. The analyses of dwell time benefits showed that dwell time benefits of both positive and negative templates were significantly larger in difficult trials than easy trials, consistent with the RT results. Correlation analyses further supported the relationship between rapid rejection benefits and RT benefits for both positive and negative trials in the difficult condition. These results highlight the importance of rapid rejection during difficult search.

General discussion

In this study, we examined the impact of task difficulty on the effectiveness of using positive and negative templates across two experiments. Previous research from Conci and colleagues (2019) found enhanced RT benefits of positive and negative templates during a difficult search task compared to an easy search task. For negative templates specifically, the RT benefits in their study were only present in the difficult search task. While task difficulty may help explain the discrepancies in the literature regarding the effectiveness of negative templates, how task difficulty changes attentional processing was unclear. Based on the observed twofold effect of attentional templates from our early work and others (Geng, 2014; Geng & DiQuattro, 2010; Zhang & Carlisle, under review), we hypothesized that task difficulty could shape the effectiveness of attentional templates through enhanced guidance, rapid rejection effect, or both.

In Experiment 1, we replicated Conci et al (2019) with a within-subject design and found search benefits were enhanced in difficult trials compared to easy trials for both positive and negative templates. This replication ensured the effectiveness of the cues could be flexibly changed within individuals. In Experiment 2, we incorporated eye-tracking measures to assess how attentional processing changed based on task difficulty. We focused on the fixations guided toward target colored items to evaluate the enhanced guidance hypothesis and dwell times on distractors to evaluate the rapid rejection hypothesis. We found clear evidence that both enhanced guidance and rapid rejection changed with task difficulty. Enhanced guidance was shown in a larger proportion of fixations on target-colored items in difficult trials for both negative and positive templates. Additionally, rapid rejection was shown by increased distractor dwell time benefits in difficult trials following both positive and negative cues. Correlation analyses supported the relationship between enhanced guidance and rapid rejection and the RT benefits. Specifically in difficult trials, we found positive correlations both between guidance benefits and RT benefits and dwell time benefits and RT benefits, for both positive and negative cues. However, in easy trials, there was no significant relationship between guidance or rapid rejection and RT benefits for negative templates. For positive templates, in easy trials there was only a significant positive correlation between dwell time benefits and RT benefits, but no significant relationship between guidance benefits and RT benefits. Together, the results of the eye movement analysis provide a much clearer picture of how negative and positive templates influence attention during search. Our results show that both attentional guidance and rapid distractor rejection were occurring from negative and positive templates, and these effects led to larger and more consistent benefits in difficult trials than easy trials. This indicates that the same mechanisms for enhancing search efficiency may be at play for both positive and negative cues. Using eye tracking to examine the attentional processes provided novel insights about how task difficulty modulates the effectiveness of both negative and positive attentional templates.

Given it is usually assumed that the primary function of attentional templates is guiding attention toward the target (Chelazzi, Duncan, Miller, & Desimone, 1998; Duncan & Humphreys, 1989), it is almost intuitive to believe that if any variable changes the effectiveness attentional templates, those changes should be mainly reflected in attentional guidance. However, our findings agree with other recent observations (Hollingworth & Bahle, 2019; Bahle, et al., 2018; Bahle & Hollingworth, 2019) demonstrating multiple attentional mechanisms, including attentional guidance and rapid target rejection, can lead to RT differences.

Our results highlight the key role played by attentional templates beyond attentional guidance: rapid distractor rejection. If attentional guidance was perfect, this reactive suppression (Geng, 2014) mechanism would not be needed. But when attentional guidance is not perfect, reactive suppression can aid visual search performance. Dwell time analyses showed both positive and negative cues led to shorter dwell time when non-target-colored distractors were fixated compared to neutral cues, suggesting that those known distractors were quickly rejected when they captured attention. Critically, the benefits of this rapid rejection increased in difficult trials compared to easy trials for both positive and negative cues, mainly because it took a long time to determine if an item was a target or distractor in the difficult condition with a neutral cue. The larger dwell time benefits in the difficult condition mapped on to the larger RT benefits for the difficult condition.

Our results, together with recent related work (Zhang & Carlisle, under review; Goldstein & Beck, 2018; Geng & DiQuattro, 2010), add to our understanding of attentional templates use in quick distractor rejection from both positive and negative templates. Early evidence for the quick rejection effect was mainly found in processing singleton distractors (Godijn & Theeuwes, 2002; Theeuwes, 2010; Geng & DiQuattro, 2010). Singleton distractors can be quickly rejected because they can be easily identified and participants know they are not the target (Geng & DiQuattro, 2010; Geng, 2014). Our findings suggest rapid rejection is also engaged in visual search with non-salient distractors. The importance of comparing the distractor to the target template is highlighted in the Attention Engagement Theory by Duncan and Humphreys (1989). In their theory, Duncan and Humphreys emphasize the benefits of homogenous distractors leading to efficient rejection of distractors through spreading suppression. But more broadly, this theory emphasizes that search efficiency depends on our ability to quickly and accurately reject distractors in addition to our ability to direct processing toward potential targets. This emphasis on distractor rejection mirrors the critical findings in our study.

We also found support for enhanced guidance from negative and positive templates on difficult trials. However, the mechanism that led to this enhanced guidance still remains unclear. It could be that participants relied on refined or sharpened color representations to guide attention in difficult trials (Conci et al., 2019), although it is important to recognize that the item colors which allowed for color-based guidance were not changed between easy and difficult trials. The only alteration between easy and difficult trials was to the distractor shapes which appeared on top of the colored circles. Alternatively, participants could strategically turn up the guidance by attentional templates in difficult trials. Previous literature has shown that attentional guidance by positive templates can be flexibly turned up based on task relevance (Carlisle & Woodman, 2011). Our findings might suggest that guidance by negative templates can be adjusted similarly as that by positive templates, and the adjustment could be based on task difficulty.

While we found an overall main effect of task difficulty on guidance benefits, when we examined the effect of task difficulty at each fixation the enhanced benefits were only significant on the fourth fixation. We would not have predicted this larger effect on later fixations. It is possible that this later enhancement effect indicates that the adjustment of guidance happened during the search rather than prior to the search. If this were the case, whether the enhancement was caused by shifts in color representations used to guide attention, as suggested by the refined representation hypothesis, or shifts in strategies of using internal representations, as suggested by the strategic guidance hypothesis, those shifts should be exerted during the search. Another alternative explanation relates to differences in the specific trials making up the data for fixation four, given that most easy trials finished with fewer fixations than difficult trials. This could mean that the easy trials which had not concluded by fixation four were trials that had weaker guidance overall, leading to the difference. Future research should work to differentiate these possibilities to further elucidate the relationship between attentional guidance and task difficulty.

How do our findings impact the larger literature on negative templates? As described in the introduction, previous examinations of negative templates have shown mixed results. While the search benefits of negative templates have been found in multiple studies with different designs of search tasks (Arita et al., 2012; Carlisle & Nitka, 2019; Reeder, Olivers, & Pollmann, 2017; Reeder, et al., 2018; Zhang & Carlisle, under review), there is also a large body of research that did not show clear benefits from negative templates (Berggren & Eimer, 2021; Becker, Hemsteger, & Peltier, 2015; Beck & Hollingworth, 2015; Beck, Luck, & Hollingworth, 2018; Cunningham & Egeth, 2016; Moher & Egeth; 2012). Our results support the idea that certain aspects of the experimental design, like search difficulty in our case, small set sizes, or distractor layout, may lead to reduced benefits from negative templates (Arita, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2012; Conci et al., 2019; Zhang & Carlisle, under review). It seems clear that negative templates are harder to implement than positive templates (Rajsic, Carlisle, & Woodman, 2020; de Vries, et al., 2019), which may help explain why some participants do not show strong benefits from negative cues (Beck & Hollingworth, 2015; Becker, Hemsteger, & Peltier, 2015). However, it is important to note that many of the previous studies have relied on behavioral RTs to determine whether participants are using negative templates to guide attention. Although reaction time and accuracy measurements can provide important information about underlying cognitive processes, they may not be sensitive to nuances in attentional processes (Hollingworth & Bahle, 2019; Bahle et al., 2018; Bahle & Hollingworth, 2019). Therefore, our work highlights the importance of examining multiple measures of attentional processing including guidance, rapid rejection, and reaction times, when examining negative templates.

In conclusion, our results provide an important new insight about the use of negative templates. While much of the previous research on negative templates has assumed benefits from negative templates are derived solely from attentional guidance, our work shows negative templates lead to both guidance and rapid distractor rejection during visual search.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4.

A) Averaged guidance benefits across fixations 1–4 in Experiment 2. B) Correlation between averaged guidance benefits and RT benefits in Experiment 2. Error bars represent +/− SEM.

Figure 6.

A) Distractor dwell time benefits for negative and positive cues in Experiment 2. Error bars represent +/− SEM. B) Correlation between distractor dwell time benefits and overall reaction time benefits in Experiment 2.

Footnotes

CRediT Author Statement

Ziyao Zhang: Software, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing-Original Draft, Review & Editing

Renee Sahatdjian: Investigation, Formal Analysis

Nancy Carlisle: Conceptualization, Software, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Resources, Writing- Review & Editing, Supervision

Note: The guidance effects showed a similar pattern when we analyzed using only fixations within an interest area.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arita JT, Carlisle NB, & Woodman GF (2012). Templates for rejection: Configuring attention to ignore task-irrelevant features. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38(3), 580–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron AR (2011). From reactive to proactive and selective control: Developing a richer model for stopping inappropriate responses. Biological psychiatry, 69(12), e55–e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahle B, & Hollingworth A (2019). Contrasting episodic and template-based guidance during search through natural scenes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 45(4), 523–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahle B, Matsukura M, & Hollingworth A (2018). Contrasting gist-based and template-based guidance during real-world visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 44(3), 367–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck VM, & Hollingworth A (2015). Evidence for negative feature guidance in visual search is explained by spatial recoding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41(5), 1190–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck VM, Luck SJ, & Hollingworth A (2018). Whatever you do, don’t look at the...: Evaluating guidance by an exclusionary attentional template. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 44(4), 645–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MW, Hemsteger S, & Peltier C (2015). No templates for rejection: A failure to configure attention to ignore task-irrelevant features. Visual Cognition, 23(9–10), 1150–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Berggren N & Eimer M (2020). The guidance of attention by templates for rejection during visual search. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH, & Vision S (1997). The psychophysics toolbox. Spatial vision, 10, 433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle NB, & Nitka AW (2019). Location-based explanations do not account for active attentional suppression. Visual Cognition, 27(3–4), 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle NB, & Woodman GF (2011). Automatic and strategic effects in the guidance of attention by working memory representations. Acta psychologica, 137(2), 217–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle NB, Arita JT, Pardo D, & Woodman GF (2011). Attentional templates in visual working memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 31(25), 9315–9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlisle NB (2019). Flexibility in Attentional Control: Multiple Sources and Suppression. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 92(1), 103–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelazzi L, Duncan J, Miller EK, & Desimone R (1998). Responses of neurons in inferior temporal cortex during memory-guided visual search. Journal of neurophysiology, 80(6), 2918–2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelazzi L, Marini F, Pascucci D, & Turatto M (2019). Getting rid of visual distractors: The why, when, how, and where. Current Opinion in Psychology, 29, 135–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conci M, Deichsel C, Müller HJ, & Töllner T (2019). Feature guidance by negative attentional templates depends on search difficulty. Visual Cognition, 27(3–4), 317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CA, & Egeth HE (2016). Taming the white bear: Initial costs and eventual benefits of distractor inhibition. Psychological science, 27(4), 476–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desimone R, & Duncan J (1995). Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annual review of neuroscience, 18(1), 193–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries IE, Savran E, van Driel J, & Olivers CN (2019). Oscillatory mechanisms of preparing for visual distraction. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 31(12), 1873–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J, & Humphreys GW (1989). Visual search and stimulus similarity. Psychological review, 96(3), 433–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspelin N, Leonard CJ, & Luck SJ (2017). Suppression of overt attentional capture by salient-but-irrelevant color singletons. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 79(1), 45–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ, & DiQuattro NE (2010). Attentional capture by a perceptually salient non-target facilitates target processing through inhibition and rapid rejection. Journal of vision, 10(6), 5–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ, & DiQuattro NE (2010). Attentional capture by a perceptually salient non-target facilitates target processing through inhibition and rapid rejection. Journal of Vision, 10(6), 1–12. Retrieved from 10.1167/10.6.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ, DiQuattro NE, & Helm J (2017). Distractor probability changes the shape of the attentional template. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 43(12), 1993–2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng JJ (2014). Attentional mechanisms of distractor suppression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(2), 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Godijn R, & Theeuwes J (2002). Programming of endogenous and exogenous saccades: Evidence for a competitive integration model. Journal of experimental psychology: human perception and performance, 28(5), 1039–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RR, & Beck MR (2018). Visual search with varying versus consistent attentional templates: Effects on target template establishment, comparison, and guidance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 44(7), 1086–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong M, Yang F, & Li S (2016). Reward association facilitates distractor suppression in human visual search. European Journal of Neuroscience, 43(7), 942–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth A, & Bahle B (2019). Eye Tracking in Visual Search Experiments. In Spatial Learning and Attention Guidance (Vol. 151, pp. 23–35). New York, NY: Springer US. 10.1007/7657_2019_30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moher J, & Egeth HE (2012). The ignoring paradox: Cueing distractor features leads first to selection, then to inhibition of to-be-ignored items. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74(8), 1590–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivers CN, Peters J, Houtkamp R, & Roelfsema PR (2011). Different states in visual working memory: When it guides attention and when it does not. Trends in cognitive sciences, 15(7), 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder RR, Olivers CN, & Pollmann S (2017). Cortical evidence for negative search templates. Visual Cognition, 25(1–3), 278–290. [Google Scholar]

- Reeder RR, Olivers CN, Hanke M, & Pollmann S (2018). No evidence for enhanced distractor template representation in early visual cortex. Cortex, 108, 279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda T, & Kawahara JI (2019). Association between cue lead time and template-for-rejection effect. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 81(6), 1880–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theeuwes J (2010). Top–down and bottom–up control of visual selection. Acta psychologica, 135(2), 77–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JM (1994). Guided search 2.0 a revised model of visual search. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1(2), 202–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe JM (2021). Guided Search 6.0: An updated model of visual search. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF, & Luck SJ (2007). Do the contents of visual working memory automatically influence attentional selection during visual search?. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 33(2), 363–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman GF, Carlisle NB, & Reinhart RM (2013). Where do we store the memory representations that guide attention?. Journal of Vision, 13(3), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, & Geng JJ (2019). The attentional template is shifted and asymmetrically sharpened by distractor context. Journal of experimental psychology: human perception and performance, 45(3), 336–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Hanks TD, & Geng J (2020). Attentional guidance and match decisions rely on different template information during visual search, PsyArxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, & Carlisle NB (2021) Assessing Recoding Accounts of Negative Attentional Templates Using Behavior and Eye Tracking, under review [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Gaspelin N, & Carlisle NB (2020). Probing early attention following negative and positive templates. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 82(3), 1166–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.