Abstract

The use of fossil fuels is a primary source of global warming owing to the greenhouse effect. Renewable energy is the best alternative environment-friendly energy source. Previous studies have highlighted the significant influence of financial development and education on renewable energy. However, the simultaneous effects of these two factors on renewable energy have rarely been examined, especially in emerging economies. This study employed dynamic seemingly unrelated cointegrating regression and the Dumitrescu–Hurlin causality test to analyze the effect of education and financial development on renewable energy consumption in N-11 countries during 1990–2016. Empirical results show that financial development significantly increased renewable energy use; however, education failed to make a positive difference. Additionally, bidirectional- and unidirectional causality was observed for financial development and education, respectively, toward renewable energy. This suggests that policymakers should combine financial development policies with education to improve the efficiency of renewable energy use.

Keywords: Education, Financial development, Renewable energy consumption, N-11 countries, Dynamic cointegration regression seems irrelevant

Introduction

Next-11 (N-11) countries viz. Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Turkey, South Korea, and Vietnam (Goldman Sachs 2007) are emerging economies that are gradually gaining global prominence. Except for South Korea and Egypt, the remaining N-11 countries figure among the world’s 20 most populous countries (Worldometers 2020). Moreover, N-11 countries are undergoing rapid economic growth. According to GDP indicators 2020, the majority of countries’ economic growth will be negative due to the impact of the Covid-19 epidemic. However, other nations, including some in N-11, continue to see positive growth rates. Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam, Turkey, and Iran experienced phenomenal growth rates of 3.798%, 3.57%, 2.906%, 1.794%, and 1.516%, respectively (StatisticsTimes 2021). The N-11 countries, therefore, contribute ~ 8% of the global GDP (Sinha et al. 2017). Large populations and rapid economic growth have caused a rapid increase in energy demand in these economies. However, their dependence on conventional fossil energy and the use of energy-consuming technologies for economic growth pose serious problems of environmental degradation (Paramati et al. 2017; Padhan et al. 2018). For example, in 2015, ~ 10% of global CO2 emissions were generated by N-11 countries (Sinha et al. 2017).

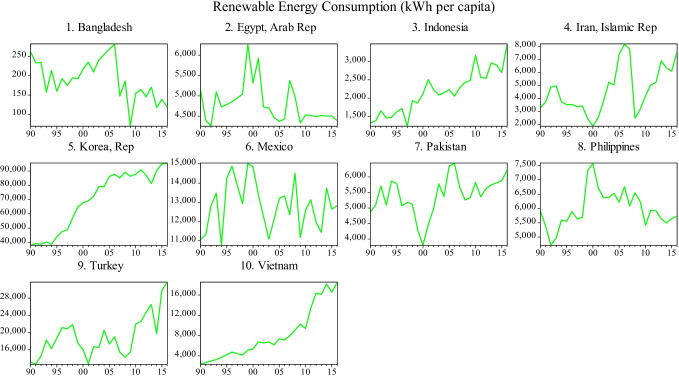

Renewable energy (RE) sources effectively succeed over fossil fuels in improving environmental quality and reducing CO2 emissions (Inglesi-Lotz and Dogan 2018; Adams and Acheampong 2019; IEA 2019a). The decline in demand for all other fuels, combined with nearly 7% growth in renewable electricity generation, leads to increased renewable energy consumption by 3% in 2020 (International Energy Agency 2021). Most N-11 countries are working to replace fossil fuels and increase renewable energy use. During 1990–2016, renewable energy investment in almost all N-11 countries increased, along with an increase in renewable energy consumption (REC) during this period (except Bangladesh and Egypt) (Fig. 1). Although renewable energy has played an important economic role for these countries, investment in renewable energy to improve environmental quality faces severe challenges. These challenges can emanate from people’s perceptions of renewable energy or the state of financial development in these countries.

Fig. 1.

The trend of renewable energy consumption in N-11 countries in 1990–2016. Sources: (IEA 2019b)

Financial development is among the most critical drivers of science and technology research, including clean energy development (Mukhtarov et al. 2020). A robust financial system can attract investments, strengthen stock markets, and improve economic activities (Sadorsky 2011; Shahbaz et al. 2018). Meanwhile, a well-organized financial infrastructure can create opportunities to provide low-cost loans to encourage a shift from fossil energy to renewable energy (Sadorsky 2011; Shahbaz et al. 2013; Mukhtarov et al. 2020). Financial development can stimulate a variety of changes, such as reduced borrowing costs and financial risks, capital generation, increased overseas investment, and improved access to energy-saving products and advanced technologies (Hashemizadeh et al. 2021c). In contrast, underdeveloped financial sectors do not facilitate well-organized loans to renewable energy producers (Brunnschweiler 2010; Hashemizadeh et al. 2021a). Sufficient time and finances are required to optimize the economic structure and change the focus from economic growth to sustainability with low-CO2 emissions, using renewable energy (Wang and Wang 2018). Hence, financial development and related policies to support energy infrastructure play an important role in the transition of energy infrastructure to renewable energy (Wu and Broadstock 2015).

People’s understanding of the role of renewable energy also affects their propensity to use them. Education about renewable energy can considerably influence REC, and raising environmental awareness is a crucial factor in developing energy policies (Saifullah et al. 2017; Zhu et al. 2018; Zafar et al. 2020). Awareness, skills, and attitude of the general public and policymakers about REC can promote environmentally sound development through the RE sector (Linde 1994). However, the lack of qualified human resources in energy technology also affects the use of renewable energy (Ulucak and Bilgili 2018; Wasif et al. 2020). Al-Marri et al. (2018) and Thøgersen et al. (2010) found that users’ education and environmental awareness depend on efficient monitoring and use of energy. Therefore, a combination of education and financial development can make RE more effective. Also, education can improve the consumers’ and investors’ understanding of financial products and risks, helping them take informed decisions about their finances and promoting the financial market (Zafar et al. 2020). Conversely, it is necessary to have specific financial sources to invest in facilities and human resources, and build capacity to improve education quality. In the energy sector, improved professional qualifications can help overcome the shortage of human resources in technology (Lucas et al. 2018). Simultaneously, raising awareness can help citizens make informed choices and use appropriate technology and energy-saving and environmentally-friendly products (Zografakis et al. 2008).

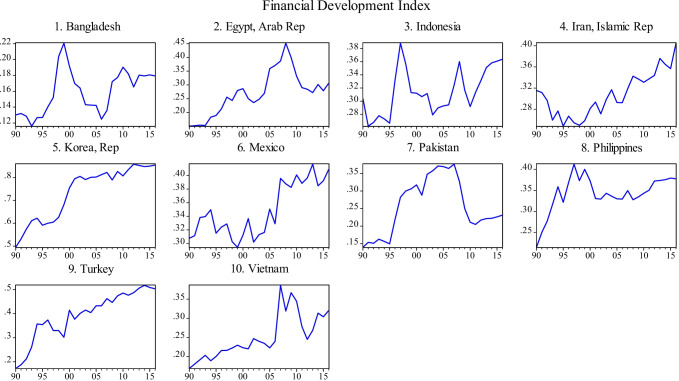

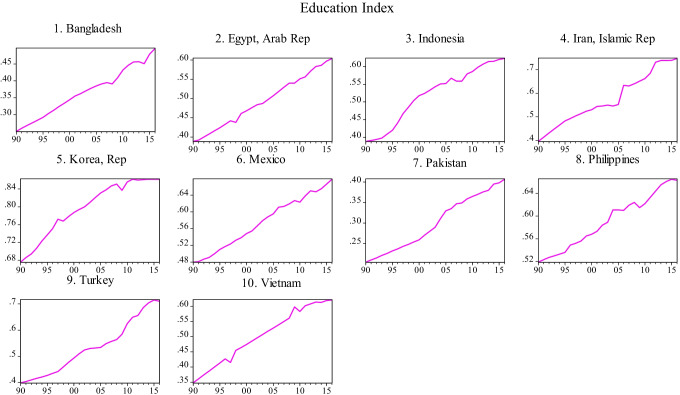

There are no clear evidence on the influence of education and financial development on renewable energy in the N-11 countries. To fill this gap, in this research, we sifted the effect of financial development or education on renewable energy in independent studies in certain N-11 nations, offering a preliminary look at how financial development and education might influence REC adoption in these countries. People are ready to pay higher rates to utilize renewable energy in Korea, which has the largest rise in the group in all three categories of REC, financial development, and education (see Figs. 1, 2, and 3). Their renewable energy investment projects are also expanding for underdeveloped nations (Lee and Shepley 2019; Kim et al. 2021). Other studies showed that common barriers to REC adoption sources in Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, and Nigeria are low public awareness, lack of social acceptance (Aliyu et al. 2018; Bhuiyan et al. 2021; Islam et al. 2021; Oryani et al. 2021), and shortage of qualified and skilled human resources (Kayahan Karakul 2016). In addition, the investment cost of this sector is considerable with a long return period. At the same time, there is a lack of access to credit; investment from the public sector, financial incentives, and government subsidies are still limited in Egypt, Iran, and Pakistan, or investment spontaneously and scattered as in Indonesia (Shah et al. 2019; Ha and Kumar 2021). Dependence on external finance through ODA or FDI sources, while the mechanisms and policies have not met the requirements, also makes it difficult for REC to attract investment capital in these countries (Yang and Park 2020). Although these studies are not representative of all N-11 countries, they also provide a partial picture of the state of education and financial development for REC in emerging economies; they represent a portion of the current status of N-11 countries. So, it remains unresolved how do education and financial development affect the rest of the N-11 countries?

Fig. 2.

The trend of financial development in N-11 countries in 1990–2016. Sources: (IMF 2019)

Fig. 3.

The trend of education in N-11 countries in 1990–2016. Sources: (UNDP 2019)

In Figs. 2 and 3, financial development investment has increased relatively evenly across all N-11 countries (see Fig. 2). Although financial development and education are steadily improving, whether these increases promote renewable energy in N-11 countries need to be clarified. The simultaneous impact of education and financial development on REC in N-11 countries is still unexplored. Hence, in this study, we employed the dynamic seemingly unrelated cointegrating regression (DSUR) and Dumitrescu-Hurlin panel causality test to answer the following research questions:

1. How do education and financial development affect renewable energy use in N-11 countries?

2. Is there a causal relationship between education, financial development, and renewable energy consumption in N-11 countries?

Unlike previous studies that only focused on analyzing the impact of either financial development or education on REC, this study attempted to determine the combined effects of education and financial development on REC in N-11 countries. The simultaneous combination of financial development and education in the renewable energy sector will be more effective than the independent impact of each factor on renewable energy. In other words, it is a combination of necessary and sufficient conditions in terms of both financial resources and knowledge, which is the main factor in determining how efficiently renewable energy is used. An independent solution rarely maximizes effectiveness when acting through human perception to adjust behavior toward the energy environment. Therefore, answering the above research questions will help N-11 countries understand how education and financial development affect REC, thereby helping formulate policies that combine education and financial development to promote efficient REC in the N-11 countries. Additionally, the results would serve as a baseline for emerging economies similar to the N-11 countries.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: “Literature review” section describes the literature that addresses the influence of education (EDU) and financial development (FD) on renewable energy. The “Theoretical framework, model specification, and data sources” section presents the model specifications and data sources. In “Analytical methodology” section, the details of the family econometric methodology used in this study are discussed. The “Results and discussion” section provides the results and discussion. The “Conclusions and policy implications” section offers conclusions and policy recommendations for the N-11 countries.

Literature review

A growing number of studies have explored the effects of CO2, GDP, foreign direct investment (FDI), trade openness, and conventional, electric, and solar energy on REC. In addition, an exploration of the financial development–REC linkage has recently attracted the attention of researchers. However, related theories focus on the relationship between financial or educational development and renewable energy. A review of the relevant literature is presented below.

The relationship between financial development and renewable energy consumption

Although several studies have examined the relationship between financial development and energy consumption, there is scant research on the relationship between financial development and REC. For example, Brunnschweiler (2010) conducted the generalized least square (GLS) analysis and found a significant positive association between financial development and REC in non-OECD countries. In another study, Wu and Broadstock (2015) used the generalized method of moment (GMM) method and observed a positive impact of financial development on REC in 22 emerging economies. Several other studies have also shown financial development to have a significantly positive effect on REC (Ondraczek et al. 2015; Dogan and Seker 2016; Best 2017; Danish et al. 2018b; Rasoulinezhad and Saboori 2018; Eren et al. 2019; Raza et al. 2020). However, Burakov and Freidin (2017) applied the vector error correction model (VECM) method and showed that financial development was not the driving force behind the REC in Russia.

Lin et al. (2016) and Wang et al. (2021a) examined the factors influencing renewable electricity consumption in China by analyzing the association between renewable electricity consumption and financial development. Their results indicated that financial development had only a minor impact on the REC. In some developing countries, financial development has not been effective for renewable energy consumption. For example, the study by Assi et al. (2021) shows that financial development hinders REC in ASEAN + 3 countries. The financial industry focuses on investing in capacity in the conventional sector, not renewable energy. Many projects on generated energy are spontaneous, which may lead to errors in statistics and be difficult to control effectively in 198 countries (Scholtens and Veldhuis 2015). In the short term, financial markets have a negligible impact on REC in Iran (Razmi et al. 2020). Yang and Park (2020) indicated the allocation of financial development from ODA or FDI sources for the renewable energy sector might be affected by policy mechanisms or corrupt factors that make it misused and ineffective; the same happens in the case of Pakistan (Shah et al. 2019). The lack of investment by the private and state sectors is one of the reasons impeding renewable energy development in Iran (Oryani et al. 2021). Another study showed that foreign direct investment could be used for clean energy projects to promote REC, but the impact is sometimes different. When policies on REC are heavily dependent on government policies and external sources, they lead to a passive state of dependence under the influence of investors (Tang et al. 2016; Ha and Kumar 2021).

The heterogeneous effect of financial development on REC depends on the region, period, and research method. Also, the high capital costs of renewable energy generation in the absence of appropriate financial support will make this process more difficult (Oryani et al. 2021). Furthermore, implementing this study is necessary to illustrate it in the study region (Oryani et al. 2021).

The relationship between education and renewable energy consumption

From another perspective of REC, very few studies have explored the relationship between education and renewable energy. Results from these studies, which mainly used primary data, indicated a connection between the two, but the impact of education on REC was unclear. Several studies have demonstrated the importance of education in raising people’s understanding of the environment. For example, Al-Marri et al. (2018) used self-determination and hierarchical needs theories. They maintained that inappropriate energy policies accompanied by energy awareness were limiting, making people less inclined to regulate energy consumption behavior in Qatar. Therefore, the best option for domestic production is to increase energy awareness through education and public engagement. Some studies have the influence of education on biodiversity conservation (e.g., Ramírez and Santana (2019)), as well as climate change disaster risk management and environmental education (e.g., Chirisa and Matamanda (2019)).

The effect of users’ education and environmental perceptions are highly dependent on the efficient monitoring and use of energy. Therefore, knowledge of the energy environment can create a hierarchical demand that affects consumer behavior and environmental values (Al-Marri et al. 2018). Jaber et al. (2017) examined the effects of factors influencing students’ knowledge and perceptions of the current energy situation and the renewable energy potential in Jordan using ANOVA, chi-square test, and post hoc comparisons to analyze the data. The results showed that most senior students were not well-versed in various renewable energy technologies and sustainability principles without information. Studying the context in Jordan, Alawin et al. (2016) conducted a comprehensive field survey on students from various engineering disciplines, using ANOVA to analyze the data. They found that students’ knowledge about renewable energy technologies and energy was relatively low, leading to the poor dissemination of energy efficiency and renewable technologies in Jordan. Studies conducted in Turkey (Karabulut et al. 2011; Karatepe et al. 2012) reported that the educational program on renewable energy was focused on teaching from the university level. Still, this number did not meet human resources requirements for the renewable energy sector. Other studies indicate that in Bangladesh, Egypt, Nigeria, and Turkey, although they receive the same status, the education system has not been appropriately improved and does not meet the requirements for qualified human resources in RE substandard energy technology. Besides, a lack of perfect understanding of RE among people and an inaccurate RE pricing system make it is weak in competition with fossil fuels (Kayahan Karakul 2016; Aliyu et al. 2018; Bhuiyan et al. 2021; Islam et al. 2021).

Perceptions about renewable energy sources in each country can be affected by their local-scale installation and use, potentially causing differences in choices in using renewable energy sources (Karytsas and Theodoropoulou 2014). Education can transform people’s behavior toward sustainable energy use and increase awareness by providing students, teachers, and parents with opportunities to learn about energy, RE, and energy-saving practices (Zografakis et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2021a). However, it is noteworthy that most previous studies used qualitative analysis methods with primary data and did not specify how education affected RE. A shortage of an educated workforce and an entire financial development system are barriers to REC’s underperformance (Ibrahiem 2015).

Projects related to clean energy and RE are increasingly being considered. Many studies have thoroughly analyzed the factors affecting the REC. However, the combined effects of financial- and educational development on RE, especially in emerging economies, have not been investigated before. Therefore, we attempt to fill this gap by exploring this relationship for the N-11 countries.

Theoretical framework, model specification, and data sources

Theoretical framework

Based on data availability and theoretical suitability, as well as the standards in REC models, we selected variables relevant to RE, such as financial development, education, economic growth, CO2 emissions, and non-renewable energy. First, the relationship between renewable and non-renewable energy seems to be complementary. For many decades, renewable energy has been considered as an effective alternative to fossil energy since conventional energy sources mainly comprise fossil fuels (coal, oil, gas, etc.) that cause CO2 emissions and environmental pollution (Alola et al. 2019; Asghar et al. 2020; Hashemizadeh et al. 2021b). Increased CO2 emissions caused by non-renewable energy sources pose a challenge to sustainable development in developing economies. Therefore, countries should invest in renewable energy infrastructure, promote research, and develop energy-efficient and clean technologies to reduce CO2 emissions (Bhat 2018; Hanif 2018; Wang et al. 2018a, 2019b). In other words, CO2 emissions are the driving force behind the change REC (Wu and Broadstock 2015; Vural 2021).

Economic growth is a relevant variable in RE analysis, with numerous studies exploring the relationship between RE and economic growth (Zafar et al. 2018; Razmi et al. 2020; Bui et al. 2021; Sharma et al. 2021). As societies progressively develop, strong economic growth increases income, leading to an increased demand for energy. Sadorsky (2009), Ozturk (2010), and Apergis and Payne (2010a, b, 2012) asserted that economic growth has an essential role in energy consumption, and increased income can drive the need for more energy, particularly RE.

In addition to the above, the two factors critical for RE use are financial development and education. Financial development can stimulate a range of changes, such as lowered borrowing costs and financial risks, financial capital generation, increasing overseas investment, and improving access to energy-saving products and advanced technology (Wang et al. 2018b). Moreover, the problems of high initial costs and long payback periods of RE projects can be addressed by having effective financial development policies. Investors in green energy business projects can receive government warranties and avail incentives for bank risk (Eren et al. 2019). Therefore, financial development can encourage countries to replace fossil energy with RE through low-cost loans (Danish et al. 2018b). A robust financial system can act as a driving force to promote investment, consolidate the stock market, and improve economic activities. Furthermore, it forms the basis for funding R&D and development projects in the RE sector, which is considered an effective mechanism for enhancing environmental quality (Inglesi-Lotz and Dogan 2018).

For financial development policies to be effective, they need to consider people’s awareness of RE issues, which underscores the vital contribution of education. Attempts have been made to raise citizens’ awareness vis-a-vis introducing RE with advanced technology to replace conventional fossil-based energy. However, not all people choose renewable energy sources over fossil fuels that are non-renewable and pollute the environment (Sinha et al. 2019). Studies demonstrate that RE education influences people’s energy consumption behavior differently in different parts of the world (Zhu et al. 2018; IEA report 2019; Munir and Riaz 2019; Wang et al. 2019a).

It is necessary to have adequate financial resources to invest in facilities and human resources and enhance management capacities to improve education quality. Investments in education, especially regarding RE, can help enhance citizens’ awareness and understanding of energy. Education can improve human resources, provide technology experts, and mitigate the existing and future. Further, the innovation of quality in education is also partly dependent on financial development as it creates investment opportunities toward developing infrastructure, upgrading facilities, and improving educational quality. Hence, combining a sound financial policy mechanism with RE education can contribute toward increasing the share of REC and help reduce CO2 emissions. Conversely, education also affects financial development, as it can improve consumers’ and investors’ understanding of products and financial risks and help them take the right decisions to adjust to their financial status accordingly, also encouraging the development of the financial market (Mandell and Klein 2009; Carpena and Zia 2020; Sun et al. 2020). In addition, improving people’s education can also raise energy- and environmental awareness among all citizens, helping people assess their surroundings better.

Financial development and education have a reciprocal relationship, and a solid financial system will support education development, the quality of education will be improved. On the contrary, education will provide the necessary information and knowledge about financial products and services for people and businesses, helping them manage the budget well, increasing saving resources, and promoting investment sources for society (Ozturk 2017). Raising awareness about RE will help consumers choose which renewable energy consumption suits their financial situation and conditions. Therefore, examining the influence of education and financial development on renewable energy as a basis for determining policies to convert renewable energy to replace fossil energy is the topic of our discussion. Here, we focus on two main variables with a simultaneous combination of financial development and education affecting renewable energy and several other variables used to clarify its effect on renewable energy in N-11 countries.

Model specification

This study aimed to study the simultaneous influence of education and financial development on REC in ten emerging economies (all N-11 countries except Nigeria) during 1990–2016. We considered REC to be influenced by various factors as follows:

| 1 |

We converted all data to a logarithmic scale to reduce the data variability and deal with potential heteroscedasticity (Shahbaz 2013; Wang et al. 2021d). Modeling using log-linear data transformation provides more reliable results by smoothing the time series data as below:

| 2 |

where i indicates the number of countries, t denotes the number of periods; the intercept is indicated by ; and is the error term. Other coefficients, expressed as , represent slopes of independent variables viz. financial development (FD), education, economic growth (GDP), CO2 emissions, and fossil energy (NRE).

Data sources

We considered annual data for N-11 countries for the period 1990–2016. Here, we used the following metrics representing the selected variables (Table 1), based on the availability of the data on REC and nonrenewable energy (in kWh per capita) from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (IEA 2019b). Data on financial development was obtained from the dataset of the International Monetary Fund (IMF 2020). Data on CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) and economic growth (GDP per capita in constant 2010 US dollars) were collected from the World Development Indicators (WDI 2019), released by Work Bank. Education can be estimated in several ways (Zafar et al. 2020). Researchers consider enrollment for secondary education (gross or higher) to represent education, assuming that this level of education is sufficient for awareness about environmental degradation and the actions necessary to protect the environment. Balaguer and Cantavella (2018) considered the total number of students enrolled at the graduate and postgraduate levels to represent education. In the present study, we used the education index formulated by the (UNDP 2019). An interpolation method with a linear approach was used to impute the missing values of CO2 emissions data following (Danish et al. 2018a; Danish et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020a). The study variables indicated in Tables 1 and 2 show the descriptive statistics for a complete panel dataset of N-11 countries. Table 2 shows that the highest volatility belongs to non-renewable energy, renewable energy, and economic growth, whereas education and financial development have the lowest volatility.

Table 1.

Description of the study variables

| Variables | Symbols | Definition | Unit | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renewable energy consumption | REC | It is collected from renewable resources, which are replenished naturally according to human timescale like solar, wind, waves, tides, rain, biomass, geothermal | kWh per capita | IEA (2019b) |

| Financial development | FD | The financial sector is the set of institutions, instruments, markets, as well as the legal and regulatory framework that permit transactions to be made by extending credit | Index | IMF (2020) |

| Education | EDU | Education indicates facilitating learning or acquiring knowledge, skills, values, beliefs, and habits. The education index is measured by expected years of schooling for children of school-entering age and means years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and more | Index | Human Development Report (2010) |

| Economic Growth | GDP | Is the gross domestic product counted GDP per capital | Constant 2010 US dollar | WDI (2019) |

| Carbon emission | CO2 | A gas is formed by burning carbon or respiration of living organisms and is considered a greenhouse gas. They are released into the atmosphere in a specific area and for a certain period | Metric tons per capita | WDI (2019) |

| Non-renewable | NRE | A nonrenewable resource (also called a finite resource) is a natural resource that cannot be readily replaced by natural means at a quick enough pace to keep up with consumption | kWh per capita | IEA (2019b) |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variables | LnREC | LnFD | LnEDU | LnGDP | LnCO2 | LnNRE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 8.619645 | − 1.179957 | − 0.687144 | 7.944872 | 0.579964 | 11.22515 |

| Median | 8.640611 | − 1.157097 | − 0.634878 | 7.774306 | 0.566787 | 11.21472 |

| Maximum | 11.46499 | − 0.151790 | − 0.148500 | 10.14581 | 2.468351 | 13.37843 |

| Minimum | 4.245796 | − 2.152263 | − 1.584745 | 5.990174 | − 1.922224 | 8.753069 |

| Jarque–Bera | 32.46991 | 3.325823 | 20.78566 | 13.92498 | 6.933051 | 6.516980 |

| Probability | 0.000000 | 0.189586 | 0.000031 | 0.000947 | 0.031225 | 0.038446 |

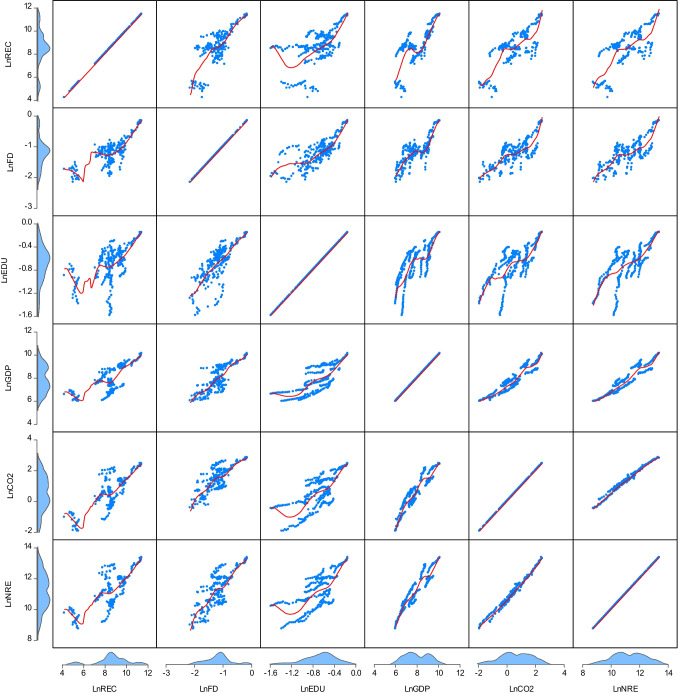

The correlations among the dependent and independent variables are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 4. Here, these tables introduce a correlation matrix between the dependent and independent variables. This correlation indicates that financial development, education, GDP, CO2 emission, and nonrenewable energy consumption positively correlate with REC. Additionally, there is a high and positive correlation between CO2 emission and NRE with GDP, CO2 emission with NRE, as well as GDP with FD.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix

| Variables | LNREC | LNFD | LNEDU | LNGDP | LNCO2 | LNNRE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNREC | 1 | |||||

| LNFD | 0.78302 | 1 | ||||

| LNEDU | 0.58124 | 0.76926 | 1 | |||

| LNGDP | 0.75199 | 0.80304 | 0.74302 | 1 | ||

| LNCO2 | 0.77469 | 0.77360 | 0.72544 | 0.93678 | 1 | |

| LNNRE | 0.74236 | 0.76318 | 0.71057 | 0.93389 | 0.99270 | 1 |

Fig. 4.

Scatter plot matrix of variables. Sources: IEA; IMF; UNDP; WDI

To be more certain about the role of FD and EDU in the REC model, we used the F statistic residual variable test to determine the simultaneous relationship between FD and EDU with REC. The results are presented in Appendix (Table A1 F-statistic for joint significance testing), and it shows that F = 46.38; df = (2264) is significant at a 1% significance level. The FD coefficient and EDU coefficient are not zero, which means at least one or both variables impact REC. That means that the research model’s choice is perfectly suitable for proceeding with the next steps.

Analytical methodology

In this study, we used the following econometric techniques for data analysis:

Cross-sectional dependence test

The data used in this study were obtained from multiple sources; it was necessary to test for cross-sectional dependence (CD) among variables. The presence of CD may lead to erroneous and inconsistent findings. We used Pesaran (2004)’s CD test to verify the existence of CD use.

| 3 |

where CD is the cross-section dependence, N indicates the cross-section dependencies, T is the period, and pij is the stochastic variations heterogeneous correlation.

Panel unit root tests

The first-generation unit root test could not be used due to the existence of cross-section dependence. Therefore, the Dickey-Fuller (CADF) test proposed by Pesaran (2007) was conducted to investigate the stationarity of the variables in this study. The CADF test is based on the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) methodology and can address cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. We calculated the lagged values of the cross-sectional means and the first difference (Δ) for each time series using the following expression:

| 4 |

where Y is the analyzed variable and is a difference operator; ; and shows the error term.

Panel cointegration test

We conducted the panel cointegration test developed by Westerlund (2007) to determine cointegration among the variables. This approach was divided into two parts. First, group statistics (Gs, Ga) exclude data from the error-correction model. The panel statistics (Ps, Pa) comprise the second part and include the error correction period data. The null hypothesis is rejected if cointegration is observed (a) with at least one cross-sectional country in group tests or (b) with all cross-sectional countries in panel tests, as concluded by Danish et al. (2019). Westerlund considered the following error-correction model:

| 5 |

where i represents the cross-sections, and t represents observations, dt refers to the deterministic components and computes the speed of convergence to an equilibrium state after a stochastic disturbance.

Long-run estimates

After assessing cointegration in the relationship among the selected variables, we estimated their long-run coefficients using a second-generation estimation method viz. dynamic seemingly unrelated cointegrating regression (DSUR) proposed by Mark et al. (2005). Even when T is significantly more than N, this method accounts for heterogeneity and cross-sectional dependence concerns, resulting in an improved forecast and a consistent normal distribution, outperforming first-generation estimation tools such as FMOLS and DOLS (Haseeb et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020b). It is expressed as:

| 6 |

where is the intercept; denotes the cointegration vector among the dependent variable () and explanatory variables (); represents a projection dimension vector; indicates the common time effects; and refers to the characteristic errors.

Dumitrescu–Hurlin test

We subsequently applied Dumitrescu and Hurlin (DH) Granger causality tests. We proposed appropriate policies for adjusting each relationship, which was unclear in the long-term estimates. Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) proposed the following model to determine causal relationships between variables X and Y:

| 7 |

where denotes the constant term, means the lag parameter, indicates the slope coefficient. and are the differences between the units of the cross-section, and K is the lag length. Here, the null hypothesis is no causal relationship in the panel, whereas the alternative hypothesis is that a causal relationship occurs in at least one subgroup. When T < N, Wald’s statistic () is recommended, while when T > N the Zbar statistic () should be used (as in our case)

| 8 |

| 9 |

where are the Wald’s statistic values in time, K is the lag length, and N is the country.

Results and discussion

Cross-sectional dependence test

The cross-sectional dependence test showed significant P values (P < 0.01) for all variables (Table 4), indicating that the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence was rejected. This implies cross-sectional dependence among REC, financial development, education, economic growth, CO2 emissions, and nonrenewable energy. These results define the method used for unit root testing and cointegration test.

Table 4.

Results of the CD test

| Variable | CD-test | P value | corr | abs(corr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LnREC | 3.57* | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.370 |

| LnFD | 17.66* | 0.000 | 0.507 | 0.512 |

| LnEDU | 34.09* | 0.000 | 0.978 | 0.978 |

| LnGDP | 32.75* | 0.000 | 0.939 | 0.939 |

| LnCO2 | 26.29* | 0.000 | 0.754 | 0.760 |

| LnNRE | 29.34* | 0.000 | 0.842 | 0.842 |

* Refers to statistical significance at 1%level.

CADF test

The CADF panel unit root test’s results (Table 5) indicate that REC, FD, education, GDP, CO2, and nonrenewable energy, and the interaction variables were stationary at the first difference. This means that there was integration at level I (1) for all the considered variables, and we can make estimates of the regression coefficients.

Table 5.

Result of the panel unit root test

| Variable | CADF | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level | First level | ||

| LnREC | − 2.135 | − 4.032* | I (1) |

| LnFD | − 2.303 | − 4.518* | I (1) |

| LnEDU | − 2.649 | − 5.018* | I (1) |

| LnGDP | − 1.837 | − 4.371* | I (1) |

| LnCO2 | − 2.106 | − 4.922* | I (1) |

| LnNRE | − 2.502 | − 4.886* | I (1) |

* Refers to statistical significance at 1% level, where CADF test significance level is (− 3.10), respectively.

Westerlund panel cointegration test

Results of the Westerlund panel cointegration test based on groups P and G indicate that the null hypothesis for the Gt statistics is rejected at 5% significance (Table 6). Hence, we conclude that the cointegration relationship between variables of underlying exists in the long run.

Table 6.

Westerlund cointegration test result

| Statistic | Value | Z value | P value | Robust P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gt | − 3.666** | − 2.238 | 0.013 | 0.020 |

| Ga | − 9.968 | 3.189 | 0.999 | 0.265 |

| Pt | − 8.508 | 0.302 | 0.619 | 0.315 |

| Pa | − 7.856 | 2.743 | 0.997 | 0.610 |

** Refers to statistical significance at 5% level.

DSUR test

Table 7, with the significance level P value < 0.05, shows that the model has a suitable regression function. The results of the DSUR test show that FD positively impacted REC ( and t = 9.71). The coefficient indicates that when financial development increases by 1%, REC increases by 1916% in N-11 countries. This finding is consistent with Danish et al. (2018b), who indicated that easier access to loans, debt, and credit can increase investors’ confidence in establishing an enterprise. In addition, FD facilitated the large financial sector and created more financial resources at lower costs, including investments in energy technology and environmental projects (Zafar et al. 2019; Zaidi et al. 2019; Raza et al. 2020). Thus, the availability of low-interest loans can create opportunities for businesses to invest in the latest infrastructure and machinery, resulting in increased energy consumption.

Table 7.

The DSUR results

| Variables | Coefficients | P value | t-statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| LnFD | 1.916* | 0.000 | 9.71 |

| LnEDU | − 1.194* | 0.000 | − 4.80 |

| LnGDP | 0.062 | 0.626 | 0.49 |

| LnCO2 | 3.162* | 0.000 | 8.65 |

| LnNRE | − 2.452* | 0.000 | − 7.08 |

| R-square | 0.747 | ||

| F-statistic | 159.57 | ||

| P-value | 0.000 |

* Refers to statistical significance at a 1% level.

The long-run estimate from DSUR shows that education negatively affected REC in N-11 countries ( and t = − 4.8). Here, indicates that a 1% increase in education would result in a 1.194% decrease in REC in these countries. This may seem surprising, but it could be explained that the change in education has not yet contributed to the benefit of REC in N-11 countries. The causes mentioned in the introduction section are similar to those in previous separate studies in Bangladesh, Egypt, Iran, and Indonesia by Aliyu et al. (2018), Bhuiyan et al. (2021), Islam et al. (2021), and Oryani et al. (2021), which could be the following two main reasons. On the one hand, although investment in education increased over time (Fig. 3), perhaps the renewable energy education programs focus on the university level and above, leading to little awareness of renewable energy and lack of social acceptance (Aliyu et al. 2018; Bhuiyan et al. 2021; Islam et al. 2021; Oryani et al. 2021). On the other hand, RE development is still limited in some countries, especially developing countries, despite the inclusion of renewable energy education in undergraduate curricula. The mismatch between the training curriculum and the actual industry needs has resulted in a shortage of skilled human resources (Alawin et al. 2016; Ha and Kumar 2021; Islam et al. 2021). This implies that although education has received attention, education programs and policies on RE do not seem to meet the needs of society (Sinha et al. 2019; Oryani et al. 2021), leading to a shortage of human resources vis-a-vis technology and RE in N-11 countries.

In addition, the propaganda and education about the benefits of using renewable and nonrenewable energy sources and their harm to the environment have not been widely deployed to all citizens. According to the bridging nature, consumption depends on motivation; motivation depends on people’s awareness and understanding level. Therefore, people’s awareness about RE, focusing only on the university level, can be considered the main factor affecting energy consumption behavior (Karytsas and Theodoropoulou 2014). Simultaneously, using RE sources is more expensive than nonrenewable energy sources; while these countries focus on economic growth and fighting poverty, this is a higher risk and challenge (Khan et al. 2019; Razmi et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2021b). Not all people consciously choose RE sources over nonrenewable energy sources. This finding suggests that education and environmental awareness play a vital role in RE development. Education helps people improve their knowledge and skills, creating increased income opportunities, which lead to increased energy demand for consumption or production (Mariana 2015). However, emerging economies (N-11) are pursuing different goals, such as reducing poverty, building infrastructure, or economic growth…. Although investment in education has increased, the limitations in the relationship between education and REC still exist, which is why the role of education has not made a positive difference in REC.

Regarding the relationship between other control variables and REC, we found that economic growth had an insignificant positive effect on the REC (Tugcu et al. 2012; Jebli et al. 2013). Several studies also indicate complementarity between renewable energy and non-renewable energy in these countries (Kahia et al. 2016; Bhat 2018). Moreover, CO2 emissions trends in these countries are continuously increasing, encouraging them to use RE to reduce pollution and protect the environment, as observed in previous studies (Saidi and Hammami 2015).

Our results help in understanding how education and financial development influenced REC in N-11 countries during 1990–2015. Financial development could play a good role in promoting REC, while education failed to make a positive difference. This indicates that internal problems make education ineffective in promoting RE. Since long-term results may not provide reliable inferences for these relationships, future studies should further examine causality between these variables.

Dumitrescu–Hurlin causality tests

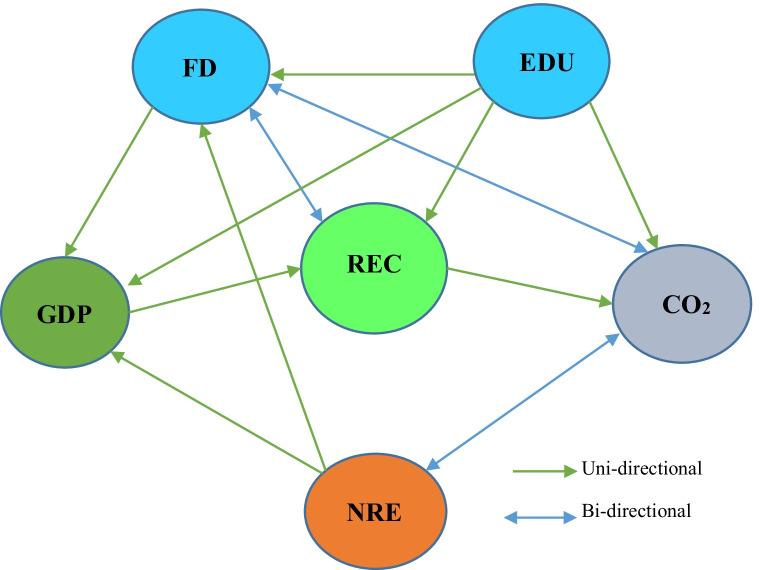

After estimating the long-term coefficients, we applied the DH method to investigate causal relationships among the variables (Table 8). This analysis confirmed the vital effects of financial development and education on REC, which was unclear in the long-term estimation (see Fig. 5). In addition, bidirectional causality was observed between financial development and REC in N-11 countries, signifying those changes in financial development can lead to changes in REC and vice versa. Furthermore, the results only showed a unidirectional causality relationship between education and REC (or FD). This means that changes in education can lead to changes in REC or FD, and not vice versa. In other words, any educational policy can affect renewable energy consumption and financial development. This finding, along with long-term estimates, is highly relevant for policymaking and serves as a basis for adjusting the education policy combined with financial development to promote REC effectively. Our results show a bidirectional causality from FD, nonrenewable energy to CO2 emissions. However, causality is unidirectional from REC, education to CO2 emissions; from education, nonrenewable energy to FD; from FD, education and nonrenewable energy to economic growth; or economic growth to REC. These findings have significant implications for policymakers in formulating long-term strategies.

Table 8.

Results of Dumitrescu-Hurlin test

| Variables | lnREC | lnFD | lnEDU | lnGDP | lnCO2 | lnNRE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnREC | – | 2.831* (0.005) | 3.605* (0.000) | 1.724*** (0.085) | 0.334 (0.738) | 1.106 (0.269) |

| lnFD | 7.815* (0.000) | – | 3.121* (0.002) | 0.964 (0.335) | 6.412* (0.000) | 4.606* (0.000) |

| lnEDU | 0.379 (0.704) | 1.252 (0.211) | – | 0.745 (0.456) | 0.692 (0.489) | 1.398 (0.162) |

| lnGDP | − 0.116 (0.901) | 2.857* (0.010) | 4.065* (0.000) | – | 0.590 (0.555) | 2.285** (0.022) |

| lnCO2 | 2.330** (0.020) | 2.593* (0.010) | 2.786* (0.005) | 1.443 (0.149) | – | 7.991* (0.000) |

| lnNRE | 0.306 (0.760) | 0.455 (0.649) | 1.107 (0.268) | 0.958 (0.338) | 7.093* (0.000) | – |

*, **,*** Indicate statistical significance at 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively.

Fig. 5.

The Dumitrescu-Hurlin causality in N-11 countries

Conclusions and policy implications

This study proposed a framework to explore the impact of education and financial development on REC in N-11 countries during 1990–2016. Two important variables, financial development, and education are selected to analyze its simultaneous impact on renewable energy consumption, thereby proposing policies that combine education and financial development to promote the positive effects of renewable energy. Various econometric techniques were used to achieve this research objective. For example, we used the CD test to check for cross-sectional dependence, the CADF method checks the unit root properties between variables, and the Westerlund panel cointegration technique to check cointegration. Additionally, the DSUR test and the Dumitrescu-Hurlin granger causality test were applied to form policy instruments for REC to solve the problems of cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. The results from the DSUR method show that financial development promoted REC, while education does not bring the desirable effect for REC. In addition, the DH causality test indicated the existence of bidirectional causality from FD to REC, and unidirectional causality from education to REC. These results provide policymakers comprehensive insights into the link between education and financial development on REC. Then formulate appropriate policies to assist renewable energy to promote its effectiveness and limit its adverse effects in current policies without affecting the growth pattern while preserving the environment in N-11 countries.

Given the problems these countries face, simultaneous policies on both education and financial development are needed. Attention also needs to be paid to the opposing effects of these two factors when formulating RE policies. It is essential to take some action to control the negative impact of education on renewable energy consumption while promoting efficient financing practices for renewable energy (Dabachi et al. 2020). Changing perceptions takes a long time to implement; to successfully pursue solutions to promote renewable energy, education policy should be divided into different phases, accompanied by timely financial support measures. In designing policies for energy education, policymakers should be aware of the impact of renewable energy education on each audience and combine appropriate financial investment policies for each group to effectively promote awareness of RE and not waste financial development resources (Sequeira and Santos 2018).

The government needs to implement policies that prioritize financial investment in renewable energy education to increase people’s awareness about the benefits of using renewable energy. Due to the awareness and lack of social acceptance surrounding the RE issue, the government should focus on financial support for activities through the media, cultural and propaganda activities, training sessions, and campaigns to raise public awareness about the energy sector environment. In addition, there should be a financial support policy or create a corridor for organizations and individuals to provide education and research services in the energy field. RE education programs should be applied at the university level and earlier education levels. The governments of these countries should encourage financial resources to develop appropriate energy education programs for each level and target audience. Invest funds to build realistic laboratories for teachers and learners, such as creating natural or artificial environments related to green energy for teaching, learning, and research. Encourage the use of different financial resources to develop school energy programs through modules that highlight energy issues in a multidisciplinary framework and enhance learners’ skills (Acikgoz 2011; Burbules et al. 2020). Organize contests to support innovative approaches in the energy sector, expanding the audience for these programs (Pietrapertosa et al. 2021).

Attract investment capital from FDI channels, banks, or the stock market for high-quality energy research institutes and product manufacturing enterprises in this field. Preference will be given to concessional loans or scholarships for those studying in energy-related areas. Additionally, R&D projects and advanced training courses on RE could be more widely deployed when funding is available at a lower cost. Countries should utilize the financial resources to expand research and technology development facilities and train experts in new technologies and RE through international cooperation. It is also necessary to conduct research and development programs related to energy conversion and RE (Abosedra et al. 2015).

This study provides systematic recommendations for implementing policies that promote RE resources. Due to inadequate data, further analysis of the impact of education on consumers and the effect of consumer culture on REC was not possible. The implications of COVID-19, corruption on renewable energy consumption, or the effect of renewables on CO2 emissions have not been mentioned. Additionally, we focus on the simultaneous impact of financial development and education on renewable energy consumption in N-11 countries, so other developing countries, such as BRICS, Sub-Saharan Africa, or less developed countries, have been ignored. These are the limitations of our study, as well as suggestions for how we can expand them in the future.

Appendix

Table 9

Table 9.

F-statistic for joint significance testing

| Variables | Restricted test equation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | P value | t-statistics | |

| LnGDP | 0.372* | 0.008 | 2.69 |

| LnCO2 | 3.323* | 0.000 | 7.90 |

| LnNRE | -2.563* | 0.000 | 6.40 |

| R-square | 0.658 | ||

| Adj R-squared | 0.654 | ||

| F-statistic | 170.83 | ||

| P value | 0.000 | ||

| Redundant variable test | |||

| Value | df | P value | |

| F-statistic | 46.438 | (2, 264) | 0.000 |

| Likelihood ratio | 81.303 | 2 | 0.000 |

Author contribution

Zhaohua Wang: writing—original draft, formal analysis, supervision, funding acquisition. Thi Le Hoa Pham: writing—original draft, validation, investigation. Bo Wang: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, project administration. Quocviet Bui: software, designed the methodology. Ali Hashemizadeh: writing—review and editing, visualization, data curation. Chulan Lasantha Kukule Nawarathna: writing—review and editing, designed the tables.

Funding

Social Science Foundation of Beijing (Award Number: 21GLCO57), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Award Number: 72074026, 71804010, 72141302), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Award Number: 9212016), Ministry of Education Key Projects of Philosophy and Social Sciences Research (Award Number: 21JZD027), Power Supply Service Management Center, State Grid Jiangxi Electric Power Co., Ltd., Nanchang (Project Number: 5218J021006P).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhaohua Wang, Email: wangzhaohua@bit.edu.cn.

Thi Le Hoa Pham, Email: phamlehoa06@bit.edu.cn.

Bo Wang, Email: b.wang@bit.edu.cn.

Ali Hashemizadeh, Email: ahz@szu.edu.cn.

Quocviet Bui, Email: buiquocviet@bit.edu.cn.

Chulan Lasantha Kukule Nawarathna, Email: lasantha@sjp.ac.lk.

References

- Abosedra S, Shahbaz M, Sbia R. The links between energy consumption, financial development, and economic growth in Lebanon: evidence from cointegration with unknown structural breaks. J Energy. 2015;2015:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2015/965825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Acikgoz C. Renewable energy education in Turkey. Renew Energy. 2011;36:608–611. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2010.08.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams S, Acheampong AO. Reducing carbon emissions: the role of renewable energy and democracy. J Clean Prod. 2019;240:118245. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alawin AA, Rahmeh TA, Jaber JO, et al. Renewable energy education in engineering schools in Jordan: existing courses and level of awareness of senior students. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;65:308–318. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aliyu AK, Modu B, Tan CW. A review of renewable energy development in Africa: a focus in South Africa, Egypt and Nigeria. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;81:2502–2518. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.06.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Marri W, Al-Habaibeh A, Watkins M. An investigation into domestic energy consumption behaviour and public awareness of renewable energy in Qatar. Sustain Cities Soc. 2018;41:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2018.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alola AA, Bekun FV, Sarkodie SA. Dynamic impact of trade policy, economic growth, fertility rate, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on ecological footprint in Europe. Sci Total Environ. 2019;685:702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apergis N, Payne JE. Renewable energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from a panel of OECD countries. Energy Policy. 2010;38:1353–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apergis N, Payne JE. Renewable energy consumption and growth in Eurasia. Energy Econ. 2010;32:1392–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2010.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apergis N, Payne JE. Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption-growth nexus: evidence from a panel error correction model. Energy Econ. 2012;34:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2011.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asghar MM, Wang Z, Wang B, Zaidi SAH. Nonrenewable energy—environmental and health effects on human capital: empirical evidence from Pakistan. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27:2630–2646. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-06686-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assi AF, Zhakanova Isiksal A, Tursoy T. Renewable energy consumption, financial development, environmental pollution, and innovations in the ASEAN + 3 group: evidence from (P-ARDL) model. Renew Energy. 2021;165:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2020.11.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer J, Cantavella M. The role of education in the environmental Kuznets curve. Evid Aust Data Energy Econ. 2018;70:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2018.01.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baloch MA, Danish MF. Modeling the non-linear relationship between financial development and energy consumption: statistical experience from OECD countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:8838–8846. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben JM, Ben YS, Ozturk I. The environmental Kuznets curve: the role of renewable and non- renewable energy consumption and trade openness. Munich Pers RePEc Arch. 2013;27:288–300. [Google Scholar]

- Best R. Switching towards coal or renewable energy? The effects of financial capital on energy transitions. Energy Econ. 2017;63:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2017.01.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat JA. Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption—impact on economic growth and CO2 emissions in five emerging market economies. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:35515–35530. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiyan MRA, Mamur H, Begum J. A brief review on renewable and sustainable energy resources in Bangladesh. Clean Eng Technol. 2021;4:100208. doi: 10.1016/j.clet.2021.100208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunnschweiler CN. Finance for renewable energy : an empirical analysis of developing and transition economies economics working paper series finance for renewable energy : an empirical analysis of developing and transitio. Econ Work Pap Ser. 2010;15:241–274. [Google Scholar]

- Bui Q, Wang Z, Zhang B, et al. Revisiting the biomass energy-economic growth linkage of BRICS countries: a panel quantile regression with fixed effects approach. J Clean Prod. 2021;316:128382. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burakov D, Freidin M. Financial development, economic growth and renewable energy consumption in Russia: a vector error correction approach. Int J Energy Econ Policy. 2017;7:39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Burbules NC, Fan G, Repp P (2020) Five trends of education and technology in a sustainable future. Geogr Sustain 1:93–97. 10.1016/j.geosus.2020.05.001

- Carpena F, Zia B. The causal mechanism of financial education: Evidence from mediation analysis. J Econ Behav Organ. 2020;177:143–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chirisa I, Matamanda AR (2019) Science communication for climate change disaster risk management and environmental education in Africa. In: Book: Sci Commun Clim Chang Disaster Risk Manag. pp 190–212. 10.4018/978-1-5225-7727-0.ch009

- Dabachi UM, Mahmood S, Ahmad AU, et al. Energy consumption, energy price, energy intensity environmental degradation, and economic growth nexus in African OPEC countries: evidence from simultaneous equations models. J Environ Treat Tech. 2020;8:403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Danish KN, Baloch MA, et al. The effect of ICT on CO2 emissions in emerging economies: does the level of income matters? Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:22850–22860. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danish SS, Baloch MA, Lodhi RN. The nexus between energy consumption and financial development: estimating the role of globalization in Next-11 countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:18651–18661. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danish, Baloch MA, Wang B (2019) Analyzing the role of governance in CO2 emissions mitigation: the BRICS experience. Struct Chang Econ Dyn 51:119–125. 10.1016/j.strueco.2019.08.007

- De GPM. The impact of financial and cultural resources on educational attainment in the Netherlands. Sociol Educ. 1986;59:237. doi: 10.2307/2112350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan E, Seker F. The influence of real output, renewable and non-renewable energy, trade and financial development on carbon emissions in the top renewable energy countries. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;60:1074–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu EI, Hurlin C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Model. 2012;29:1450–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eren BM, Taspinar N, Gokmenoglu KK. The impact of financial development and economic growth on renewable energy consumption: empirical analysis of India. Sci Total Environ. 2019;663:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.01.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha YH, Kumar SS. Investigating decentralized renewable energy systems under different governance approaches in Nepal and Indonesia: how does governance fail? Energy Res Soc Sci. 2021;80:102214. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2021.102214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanif I (2018) Impact of economic growth, nonrenewable and renewable energy consumption, and urbanization on carbon emissions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:15057–15067. 10.1007/s11356-018-1753-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Haseeb A, Xia E, Danish, et al (2018) Financial development, globalization, and CO2 emission in the presence of EKC: evidence from BRICS countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res 25:31283–31296. 10.1007/s11356-018-3034-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hashemizadeh A, Bui Q, Kongbuamai N. Unpacking the role of public debt in renewable energy consumption: new insights from the emerging countries. Energy. 2021;224:120187. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2021.120187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemizadeh A, Bui Q, Zaidi SAH (2021b) A blend of renewable and nonrenewable energy consumption in G-7 countries: the role of disaggregate energy in human development? Energy 241:122520. 10.1016/j.energy.2021.122520

- Hashemizadeh A, Ju Y, Bamakan SMH, Le HP. Renewable energy investment risk assessment in belt and road initiative countries under uncertainty conditions. Energy. 2021;214:118923. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.118923. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Human Development Report (2010) The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development. In: UNDP website. https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-2010. Accessed 11 October 2021

- Ibrahiem DM. Renewable electricity consumption, foreign direct investment and economic growth in Egypt: an ARDL approach. Procedia Econ Financ. 2015;30:313–323. doi: 10.1016/s2212-5671(15)01299-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IEA (2019a) Renewables 2019 – Market analysis and forecast from 2019 to 2024. In: IEA website. https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2019. Accessed 10 March 2020

- IEA (2019b) IEA 2019b. In: IEA website. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics. Accessed 5 Dec 2019

- IEA report (2019) Global energy & CO2 status report. (The latest trends in energy and emissions in 2018). In: IEA website. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-co2-status-report-2019. Accessed 10 November 2020

- IMF (2019) Financial Development Index. In: IMF website. https://www.imf.org/en/Data. Accessed 9 Jul 2019

- IMF (2020) Financial development. In: IMF website. https://www.imf.org/en/Data. Accessed 5 Apr 2020

- Inglesi-Lotz R, Dogan E. The role of renewable versus non-renewable energy to the level of CO2 emissions a panel analysis of sub-Saharan Africa’s Βig 10 electricity generators. Renew Energy. 2018;123:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2018.02.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (2021) Global Energy Review 2021. In: IEA website. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energyreview-2021. Accessed 15 January 2022

- Islam A, Hossain MB, Mondal MAH, et al. Energy challenges for a clean environment: Bangladesh’s experience. Energy Rep. 2021;7:3373–3389. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2021.05.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaber JO, Awad W, Rahmeh TA, et al. Renewable energy education in faculties of engineering in Jordan: relationship between demographics and level of knowledge of senior students’. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;73:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.141. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahia M, Ben Aïssa MS, Charfeddine L. Impact of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption on economic growth: new evidence from the MENA Net Oil Exporting Countries (NOECs) Energy. 2016;116:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2016.07.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karabulut A, Gedik E, Keçebaş A, Alkan MA. An investigation on renewable energy education at the university level in Turkey. Renew Energy. 2011;36:1293–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2010.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karatepe Y, Neşe SV, Keçebaş A, Yumurtaci M. The levels of awareness about the renewable energy sources of university students in Turkey. Renew Energy. 2012;44:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2012.01.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karytsas S, Theodoropoulou H. Socioeconomic and demographic factors that influence publics’ awareness on the different forms of renewable energy sources. Renew Energy. 2014;71:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.05.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kayahan Karakul A. Educating labour force for a green economy and renewable energy jobs in Turkey: a quantitave approach. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;63:568–578. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MWA, Panigrahi SK, Almuniri KSN et al (2019) Investigating the dynamic impact of CO2 emissions and economic growth on renewable energy production: evidence from FMOLS and DOLS tests. Processes 7:496. 10.3390/pr7080496

- Kim JH, Seo SJ, Yoo SH. South Koreans’ willingness to pay price premium for electricity generated using domestic solar power facilities over that from imported ones. Sol Energy. 2021;224:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2021.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Shepley M. Benefits of solar photovoltaic systems for low-income families in social housing of Korea: renewable energy applications as solutions to energy poverty. J Build Eng. 2019;28:101016. doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2019.101016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Omoju OE, Okonkwo JU. Factors influencing renewable electricity consumption in China. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;55:687–696. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde HA (1994) The impact of renewable energy on education in developing countries in Africa. Renew Energy 5:1413–1415. 10.1016/0960-1481(94)90181-3

- Lucas H, Pinnington S, Cabeza LF. Education and training gaps in the renewable energy sector. Sol Energy. 2018;173:449–455. doi: 10.1016/j.solener.2018.07.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell L, Klein LS. The impact of financial literacy education on subsequent financial behavior. J Financ Couns Plan Educ. 2009;20:15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mariana DR. Education as a determinant of the economic growth. the case of Romania. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2015;197:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mark NC, Ogaki M, Sul D. Dynamic seemingly unrelated cointegrating regressions. Rev Econ Stud. 2005;72:797–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-937X.2005.00352.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtarov S, Humbatova S, Seyfullayev I, Kalbiyev Y. The effect of financial development on energy consumption in the case of Kazakhstan. J Appl Econ. 2020;23:75–88. doi: 10.1080/15140326.2019.1709690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munir K, Riaz N (2019) Energy consumption and environmental quality in South Asia: evidence from panel non-linear ARDL. Environ Sci Pollut Res 26:29307–29315. 10.1007/s11356-019-06116-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ondraczek J, Komendantova N, Patt A. WACC the dog: the effect of financing costs on the levelized cost of solar PV power. Renew Energy. 2015;75:888–898. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.10.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oryani B, Koo Y, Rezania S, Shafiee A. Barriers to renewable energy technologies penetration: perspective in Iran. Renew Energy. 2021;174:971–983. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.04.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk I. A literature survey on energy–growth nexus. Energy Policy. 2010;38:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.09.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk I (2017) Energy dependency and energy security: the role of energy efficiency and renewable energy sources. Pakistan Inst Dev Econ, Islam 52:309–332. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24397894

- Padhan H, Haouas IB, Heshmati A. What matters for environmental quality in the next-11 countries : economic growth or income inequality ? What Matters for Environmental Quality in the Next-11 Countries : Economic Growth or Income Inequality ? Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;26:23129–23148. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paramati SR, Sinha A, Dogan E. The significance of renewable energy use for economic output and environmental protection: evidence from the Next 11 developing economies. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2017;24:13546–13560. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-8985-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran MH (2004) General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels (August 2004). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=572504 or 10.2139/ssrn.572504

- Pesaran MH. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J Appl Econom. 2007;22:265–312. doi: 10.1002/jae.951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrapertosa F, Tancredi M, Salvia M, et al. An educational awareness program to reduce energy consumption in schools. J Clean Prod. 2021;278:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F, Santana J (2019) Environmental education and biodiversity conservation. In: Springer briefs in environmental science. Book, pp 7-11. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-01968-6_2

- Rasoulinezhad E, Saboori B. Panel estimation for renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, economic growth, CO2 emissions, the composite trade intensity, and financial openness of the commonwealth of independent states. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:17354–17370. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-1827-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza SA, Shah N, Qureshi MA, et al (2020) Non-linear threshold effect of financial development on renewable energy consumption: evidence from panel smooth transition regression approach. Environ Sci Pollut Res 1–14. 10.1007/s11356-020-09520-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Razmi SF, Ramezanian Bajgiran B, Behname M, et al. The relationship of renewable energy consumption to stock market development and economic growth in Iran. Renew Energy. 2020;145:2019–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Razmi SF, Moghadam MH, Behname M. Time-varying effects of monetary policy on Iranian renewable energy generation. Renew Energy. 2021;177:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs G (2007) Goldman Sachs Economics Research - The N-11: More than an Acronym. GS Global Econ 153:1–24. website http://energyfuture.wdfiles.com/local--files/us-energy-use/GDP-Source2.pdf. Accessed 27 September 2020

- Sadorsky P. Renewable energy consumption and income in emerging economies. Energy Policy. 2009;37:4021–4028. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadorsky P. Financial development and energy consumption in Central and Eastern European frontier economies. Energy Policy. 2011;39:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2010.11.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saidi K, Hammami S. The impact of CO2 emissions and economic growth on energy consumption in 58 countries. Energy Rep. 2015;1:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.egyr.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saifullah MK, Kari FB, Ali MA. Linkage between public policy, green technology and green products on environmental awareness in the urban Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J Asian Financ Econ Bus. 2017;4:45–53. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2017.vol4.no2.45. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saud S, Danish CS. An empirical analysis of financial development and energy demand: establishing the role of globalization. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:24326–24337. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2488-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens B, Veldhuis R (2015) How does the development of the financial industry advance renewable energy? A panel regression study of 198 countries over three decades. In: Conference. pp 1–42. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/113114

- Sequeira T, Santos M. Education and energy intensity: simple economic modelling and preliminary empirical results. Sustain. 2018;10:1–17. doi: 10.3390/su10082625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SAA, Solangi YA, Ikram M. Analysis of barriers to the adoption of cleaner energy technologies in Pakistan using modified delphi and fuzzy analytical hierarchy process. J Clean Prod. 2019;235:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M. Does financial instability increase environmental degradation? Fresh evidence from Pakistan. Econ Model. 2013;33:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2013.04.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M, Khan S, Tahir MI. The dynamic links between energy consumption, economic growth, financial development and trade in China: fresh evidence from multivariate framework analysis. Energy Econ. 2013;40:8–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2013.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M, Destek MA, Polemis ML (2018) Do foreign capital and financial development affect clean energy consumption and carbon emissions? Evidence from BRICS and Next-11 Countries. J Econ Bus 68:20–50

- Sharma GD, Tiwari AK, Erkut B, Mundi HS. Exploring the nexus between non-renewable and renewable energy consumptions and economic development: evidence from panel estimations. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;146:111152. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Gupta M, Shahbaz M, Sengupta T. Impact of corruption in public sector on environmental quality: implications for sustainability in BRICS and next 11 countries. J Clean Prod. 2019;232:1379–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Shahbaz M, Balsalobre D (2017) Exploring the relationship between energy usage segregation and environmental degradation in N-11 countries. J Clean Prod December 2:1217–1229. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.071

- StatisticsTimes (2021) GDP Indicators 2020. In: StatisticsTimes.com. https://statisticstimes.com/economy/gdp-indicators-2020.php. Accessed 20 Nov 2021

- Sun H, Yuen DCY, Zhang J, Zhang X. Is knowledge powerful? Evidence from financial education and earnings quality. Res Int Bus Financ. 2020;52:101179. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.101179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CF, Tan BW, Ozturk I. Energy consumption and economic growth in Vietnam. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2016;54:1506–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen J, Haugaard P, Olesen A. Consumer responses to ecolabels. Eur J Mark. 2010;44:1787–1810. doi: 10.1108/03090561011079882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tugcu CT, Ozturk I, Aslan A. Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption and economic growth relationship revisited: evidence from G7 countries. Energy Econ. 2012;34:1942–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2012.08.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ulucak R, Bilgili F. A reinvestigation of EKC model by ecological footprint measurement for high, middle and low income countries. J Clean Prod. 2018;188:144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNDP (2019) Education index. In: United Nations Dev. Program. website. http://hdr.undp.org/en/data. Accessed 9 Jul 2019

- Vural G. Analyzing the impacts of economic growth, pollution, technological innovation and trade on renewable energy production in selected Latin American countries. Renew Energy. 2021;171:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2021.02.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang Z. Heterogeneity evaluation of China’s provincial energy technology based on large-scale technical text data mining. J Clean Prod. 2018;202:946–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Sun Y, Wang Z. Agglomeration effect of CO2 emissions and emissions reduction effect of technology: a spatial econometric perspective based on China’s province-level data. J Clean Prod. 2018;204:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Wang X, Guo D, et al. Analysis of factors influencing residents’ habitual energy-saving behaviour based on NAM and TPB models: egoism or altruism? Energy Policy. 2018;116:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2018.01.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Ren C, Dong X, et al. Determinants shaping willingness towards on-line recycling behaviour: an empirical study of household e-waste recycling in China. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2019;143:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Sun Y, Wang B. How does the new-type urbanisation affect CO 2 emissions in China? An empirical analysis from the perspective of technological progress. Energy Econ. 2019;80:917–927. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2019.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Bui Q, Zhang B. The relationship between biomass energy consumption and human development: empirical evidence from BRICS countries. Energy. 2020;194:116906. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.116906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Deng N, Li H, et al. Effect and mechanism of monetary incentives and moral suasion on residential peak-hour electricity usage. Technol Forecast Soc Change. 2021;169:120792. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Deng N, Liu X, et al. Effect of energy efficiency labels on household appliance choice in China: sustainable consumption or irrational intertemporal choice? Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;169:105458. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Yuan Z, Liu X, et al. Electricity price and habits: which would affect household electricity consumption? Energy Build. 2021;240:110888. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2021.110888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Bui Q, Zhang B, et al. The nexus between renewable energy consumption and human development in BRICS countries: the moderating role of public debt. Renew Energy. 2021;165:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2020.10.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Bui Q, Zhang B, Pham TLH (2020b) Biomass energy production and its impacts on the ecological footprint: an investigation of the G7 countries. Sci Total Environ 743:140741. 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2020.124658 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wasif M, Qin Q, Nasir M, et al. Foreign direct investment and education as determinants of environmental quality : the importance of post Paris Agreement ( COP 21) J Environ Manage. 2020;270:110827. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WDI (2019) World bank. In: World Bank website. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator. Accessed 9 Jul 2019