Abstract

The Sonic hedgehog-activated subgroup of medulloblastoma (SHH-MB) is one of the most common malignant pediatric brain tumors. Recent clinical studies and genomic databases indicate that GABAA receptor holds significant clinical relevance as a therapeutic target for pediatric MB. Herein, we report that “moxidectin,” a GABAA receptor agonist, inhibits the proliferation of Daoy, UW426, UW228, ONS76, and PFSK1 SHH-MB cells by inducing apoptosis. Immunoblotting and immunofluorescence microscopy demonstrated that moxidectin significantly induced GABAA receptor expression and inhibited cyclic AMP (cAMP)-mediated protein kinase A (PKA)-cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-Gli1 signaling in SHH-MB. Gli1 and the downstream effector cancer stem cell (CSC) molecules such as Pax6, Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog were also inhibited by moxidectin treatment. Interestingly, moxidectin also inhibited the expression of MDR1. Mechanistic studies using pharmacological or genetic inhibitors/activators of PKA and Gli1 confirmed that the anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of moxidectin were mediated through inhibition of PKA-Gli1 signaling. Oral administration of 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin suppressed the growth of SHH-MB tumors by 55%–80% in subcutaneous and intracranial tumor models in mice. Ex vivo analysis of excised tumors confirmed the observations made in the in vitro studies. Moxidectin is an FDA-approved drug with an established safety record, therefore any positive findings from our studies will prompt its further clinical investigation for the treatment of MB patients.

Keywords: pediatric medulloblastoma, protein kinase A, Gli1, moxidectin, cancer stem cells, CREB, cAMP, GABA, SHH

Graphical abstract

This study not only for the first time established the tumor-promoting role of PKA-Gli1 signaling in MB but also showed that moxidectin suppresses the growth of MB tumors by inhibiting this oncogenic signaling.

Introduction

Pediatric brain tumors (PBTs) are one of the most common malignancies and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Medulloblastoma (MB), a primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET), is the most prevalent form of PBT and mostly occurs in children 3–10 years of age, where the culminating incident occurs at the age 7.1 Recent genomic analysis identified that intrinsic differences between MB subtypes govern its manifestations and impact the clinical outcome.2,3 For example, Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling is a developmental pathway that plays major role in the normal cerebellar development; however, constitutive activation of SHH signaling can lead to tumorigenesis. Additionally, mutations in the major players of the SHH pathway are sufficient to drive MB progression.4 Transcriptional profiling characterizes MB tumors into four major subgroups: the WNT activated, where the canonical Wnt signaling is upregulated, the SHH subtype, with non-canonical and canonical activation of the pathway and its downstream players, and groups “3” and “4.”5 In canonical SHH signaling, the HH ligand binds to patched transmembrane receptor 1 (PTCH1) and releases G-protein-coupled-like receptor smoothened (SMO), consequently releasing Gli1 from negative regulator suppressor of fused (SUFU).6 Gli1 can also be activated non-canonically via SMO-independent signals.7,8 Nuclear translocation of Gli1 governs the activation of downstream cancer stem cell markers Oct4, Sox2, Pax6, and Nanog that in turn mediate stemness of cancer cells, angiogenesis, resistance to therapy, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT).9,10

Given the pivotal role of SHH signaling and GABA in cerebellum development, it is inevitable that the majority of MB tumors have elevated SHH signaling.11 Interestingly, in several cancers, aberrant activation of SHH-Gli1 signaling has been linked with the reduced expression of GABAA receptor.12,13 Physiological stresses can suppress the activity of GABAA receptor and, in turn, can directly activate cyclic AMP (cAMP)-dependent intracellular signaling pathways as a compensatory cellular process for GABAA-deficient cells along with simultaneous suppression of tumor suppressor genes.4,13, 14, 15

cAMP-protein kinase A (PKA) signaling functions as a double-edged sword wherein it can mediate tumorigenic progression by maintaining glioma-initiating cells (GICs) but, on the other hand, can also inhibit its progression through cell growth and developmental pathways.16, 17, 18 Moreover, stimulation of the PKA pathway has been associated with enhanced activation of the multiple drug resistance gene (MDR1), an ATP-driven efflux protein.19 Current clinical approaches are utilizing several techniques to control the expression of MDR1 at the transcriptional level.20 The role of GABAA receptor in cAMP-PKA-mediated progression of SHH-MB has not been well established and is an understudied area.

Drug re-purposing is an innovative strategy to identify new drug indications for already-approved drugs. It surpasses the de novo drug development strategy due to its pre-existing pharmacokinetic profile. Several non-neoplastic drugs such as pimavenserin tartrate, atovaquone, penfluridol, pimozide, and benzodiazepine have been re-purposed in various cancer models.8,21, 22, 23, 24, 25

In the present study, we evaluated the anti-cancer effects of moxidectin, an anthelmintic drug that was primarily used to control or prevent parasitic infections in animals by acting as an agonist of GABAA receptor and was recently approved for the treatment of onchocerciasis in the US.26,27 Our current study not only for the first time established the tumor-promoting role of PKA-Gli1 signaling in MB but also showed that moxidectin suppresses the growth of MB tumors by inhibiting this oncogenic signaling.

Results

Patient-derived MB tumors possess reduced GABAA-receptor expression and upregulated PKA-Gli1 signaling

We analyzed several publicly available databases for the level of GABAA receptor in MB cancer patients. Analysis of gene expression profiles using the R2 public database software showed that GABAA receptor subunits α1–α5 were downregulated in MB patient samples (blue) compared with normal brain (gray) (Figure 1A). Similar observations were made when we analyzed the Oncomine database, where all the genes of pomeroy brain region in desmoplastic MB patients were compared with normal brain (Figure 1B). The Kaplan-Meier curve obtained from the R2 genomic database indicated that high expression of PKA catalytic subunit α gene (PRKACA) results in reduced survival of MB patients (Figure 1C). Several serine-threonine kinases such as PKA can transcriptionally regulate and activate cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB).28 R2, Oncomine, and GENT2 databases indicated over-expression of CREB1 in MB patient samples (Figures 1D–1F). Gli1 is a major transcription factor downstream of SHH signaling and is a key player in SHH-MB progression. The Kaplan-Meier curve and Oncomine databases confirm the association of Gli1 overexpression with reduced overall survival of MB patients (Figures 1G and 1H). Neurotransmitter-mediated tumor progression can result in increased cAMP signaling.29 We screened the PRECOG database to evaluate the expression of GABAA, PRKACA, CREB1, and Pax6, the key players of cAMP signaling in MB. The results from this database indicated that MB patient tumors are characterized by enhanced expression of all these genes (Figure 1I). MB data available in the R2 genomic database showcased that the majority of MB tumor datasets exhibit reduced GABAA-receptor expression when compared with the mRNA-level expression of PRKACA and Gli1. Overall, MB tumors have compromised GABAA-receptor expression along with hyperactivation of PKA-Gli1 signaling.

Figure 1.

MB tumors exhibit reduced GABAA receptor expression

(A) R2 Mega Sampler software (hgserver1.amcnl/cgi-bin/r2/main.cgi) analyzed datasets showing comparative GABAA receptor subunit mRNA expression in normal versus MB tumors (a = normal brain 172 [Berchtold], b = normal brain 44 [Harris], c = tumor MB 73 [Pfister], d = tumor MB-ATRT [Hsieh], e = tumor MB 51 [denBOER], f = tumor MB 57 [Delattre], g = tumor MB 62 [Kool], and h = tumor MB 76 [Gilbertson]). (B) GABAA receptor α1 and α6 fold-change expression in normal versus MB tumors (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html). (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curve based on PRKACA gene expression obtained from R2 database. (D) Expression of CREB1 gene in MB patient samples compared with the normal brain samples obtained from R2 genomic database. (E) Comparison of CREB1 mRNA expression in normal tissues and multiple brain cancers. The data were generated using the Gene Expression across Normal and Tumor tissue (GENT) portal (medical-genome.kribb.re.kr/GENT). (F and G) CREB1 and Gli1 mRNA expression in normal versus MB tumors. Data were generated using public R2 Mega Sampler software. (H) Survival curve obtained from R2 public database displaying the reduced survival of MB patients due to over-expression of Gli1. (I) Survival Z scores associated with mRNA expression of different genes in various cancer models. The data was obtained from the Prediction of Clinical Outcome from Genomic Profiles (PRECOG) database (precog.stanford.edu). (J) Levels of GABRA1, PRKACA, and Gli1 mRNA in six independent datasets of MB as analyzed using the R2: Genomic Analysis and Visualization Platform. (K) GABAA receptor was ectopically expressed in UW426 cells. Immunoblotting was performed using cell lysates to evaluate the expression of GABAA receptor, Gli1, and cleaved caspase-3. (L–N) K blots were quantitated and normalized with respective actins. The figure shown is the representative blot of at least two replicates. ∗p ≤ 0.05. (O) Western blotting to evaluate the effect of moxidectin on MDR1/ABCB1 in Daoy and PFSK1 MB cells. (P and Q) Immunofluorescence microscopy performed on Daoy and ONS76 MB cells treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h. The image is a representation of images from three independent experiments.

Ectopically inducing GABAA receptor inhibits Gli1

To establish the effects of GABAA receptor in MB, we ectopically over-expressed GABAA receptor in UW426 cells using GABAA receptor expressing plasmid (Figure 1K). Our results indicate that over-expression of GABAA receptor resulted in reduced expression of Gli1 in UW426 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 1L and 1M). Additionally, an enhanced cleavage of caspase 3 was observed with receptor over-expression (Figure 1N). These results indicate that over-expressing GABAA receptor might induce apoptosis in MB cells by inhibiting Gli1 (Figures 1K–1N).

Moxidectin suppressed MDR1 and enhanced the expression of GABAA receptor in MB tumors

Efflux proteins such as MDR1 play a critical role in inducing drug resistance and hold an inverse relationship with current chemotherapeutic drugs.30 Therefore, to evaluate the effect of moxidectin on the expression of MDR1, we treated Daoy and PFSK1 cells using varying concentrations of moxidectin. Our results indicate that moxidectin suppresses the expression of the MDR1/ABCB1 gene in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating the potential of moxidectin (Figure 1O). Furthermore, to evaluate the effect of moxidectin on the expression of GABAA receptor, Daoy and ONS76 MB cells were treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h, and the expression of GABAA receptor was evaluated by immunofluorescence microscopy. Our results indicate that moxidectin treatment resulted in an increase in the expression of GABAA receptor as shown by enhanced fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) staining (green) (Figures 1P and 1Q).

Moxidectin suppresses the proliferation and colony-forming ability of MB cells

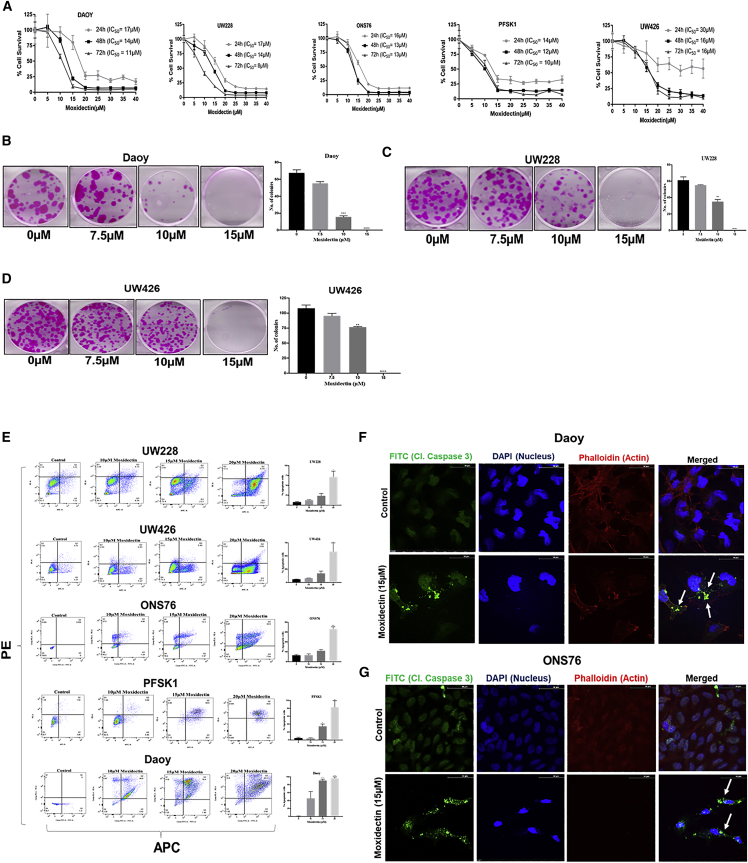

To evaluate the anti-proliferative effects of moxidectin, Daoy, UW228, UW426, ONS76, and PFSK1 cells were treated with moxidectin in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Our results indicate that moxidectin suppressed the proliferation of all the MB cells with half maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) ranging from 8 to 30 μM at 24, 48, and 72 h in all cell lines (Figure 2A). In order to evaluate the anti-clonogenic effects of moxidectin, Daoy, UW228, and UW426 cells were treated with sub-toxic concentrations of moxidectin. Our results indicate that 10 μM moxidectin suppressed 25%–50% colonies of MB cells, whereas 15 μM moxidectin completely inhibited the colonies in all three cell lines (Figures 2B–2D) These results indicate that moxidectin has growth-suppressive effects on MB cells.

Figure 2.

Moxidectin suppresses the proliferation of pediatric MB cells by inducing apoptosis

(A) Cytotoxic effects of moxidectin in Daoy, UW228, ONS76, UW426, and PFSK1 MB cells treated with various concentrations of moxidectin for 24, 48, and 72 h time points. Cell-survival assay was evaluated using SRB, and IC50 values were determined using Prism software. The experiments in all cell lines were repeated at least 3 times with 4 replicates in each experiment. (B–D) Colony-inhibiting effect of moxidectin was tested in Daoy, UW228, and UW426 cells. The sub-toxic dose of moxidectin was used to evaluate the anti-clonogenic effects of moxidectin. The experiment was repeated twice with at least three replicates in each experiment. Statistically significant ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001. (E) Apoptosis-inducing effects of moxidectin were analyzed in UW228, UW426, ONS76, PFSK1, and Daoy cells using AnnexinV-APC/PI apoptosis assay. The data were analyzed using FlowJo software. (F and G) Immunofluorescence analysis of 15 μM-treated Daoy and ONS76 cells. The data show the presence of cleaved caspase-3 in moxidectin-treated cells compared with control. The experiments were repeated at least three times. Statistically significant ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001.

Moxidectin induces apoptosis in MB cells

To determine the mechanism of the growth-suppressive effects of moxidectin, Daoy, UW228, UW426, ONS76, and PFSK1 cells were processed for AnnexinV-APC/PI assay following moxidectin treatment for 48 h. As shown in Figure 2E, treatment with 20 μM moxidectin induced 60%–90% apoptosis in UW426, UW228, ONSS76, PFSK1, and Daoy MB cells. Immunofluorescence microscopy confirmed the apoptotic effects of moxidectin, where enhanced cellular localization of cleaved caspase-3 was observed in 15 μM moxidectin-treated Daoy and ONS76 MB cells compared with control cells (Figures 2F and 2G). Additionally, induction of apoptosis was confirmed through western blotting, where moxidectin treatment resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in the cleavage of caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Moxidectin inhibits non-canonical SHH signaling

(A) Western blotting of Gli1, Pax6, Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, cleaved caspase-3, and cleaved PARP in Daoy, ONS76, UW228, UW426, and PFSK1 cells treated with 0, 10, 15, and 20 μM moxidectin for 48 h. (B) Western blotting on the nuclear fraction of moxidectin-treated Daoy cells. (C) Immunofluorescence microscopy on moxidectin-treated Daoy cells to evaluate the expression of Gli1. (D) Images of medullospheres formed from Daoy and ONS76 cells with or without moxidectin treatment. The data were replicated at least three times independently.

Inhibition of cAMP-mediated PKA signaling by moxidectin treatment

Human MB tumors express a reduced GABAA receptor, which leads to increased production of the secondary messenger cAMP. Since we observed an increased GABAA receptor in response to moxidectin treatment, the next logical step was to examine cAMP. The levels of cAMP after moxidectin treatment were thus evaluated using ELISA assay. Our results showed that moxidectin treatment after 24 h significantly reduced cAMP levels in UW426 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3A). For example, 15 μM moxidectin treatment reduced cAMP levels by 60% (Figure 3A). In order to elucidate the mechanism behind the growth-suppressive effects of moxidectin, western blotting was performed using control and moxidectin-treated Daoy and UW228 cells. Our results indicate that moxidectin treatment inhibited the expression of cAMP, a second messenger in the PKA signaling pathway (Figures 3B and 3C). Interestingly, moxidectin treatment inhibited the activation of PKA by suppressing its phosphorylation at Thr197 (Figures 3B and 3C). The major peptide substrates of PKA containing a phosphorylated Ser/Thr residue with arginine at -3 and -2 positions were also significantly reduced with moxidectin treatment as evaluated using phospho-PKA substrate (RRXS∗/T∗)(100G7E) antibody. CREB and the activated form of CREB (p-CREB (Ser 133)), a major downstream regulator of the PKA pathway, were also inhibited by moxidectin treatment in Daoy and UW228 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 3B and 3C). Immunofluorescence analysis of Daoy and ONS76 cells revealed that 15 μM moxidectin significantly reduced the level of p-CREB compared with the control (Figures 3D and 3E). These results indicate that moxidectin may suppress the proliferation of MB cells by inhibiting cAMP-mediated PKA signaling.

Figure 3.

Moxidectin suppresses cAMP production, inhibits PKA pathway, and increases the interaction between PKA RIIα and catalytic subunit in MB cells

(A) cAMP ELISA assay on UW426 cells. (B and C) Western-blotting analysis on the whole-cell lysates of moxidectin-treated Daoy and UW228 cells. (D and E) Immunofluorescence microscopy on Daoy and ONS76 cells treated with 15 μM moxidectin to evaluate the expression of p-CREB(Ser133). All experiments were repeated at least two times. Statistically significant ∗p ≤ 0.05. (F) Pictorial representation of the mechanism of PKA activation. (G) Immunoprecipitation analysis on moxidectin-treated Daoy cells. Lysates were immunoprecipitated using PKA Cα antibody and immunoblotted against PKA RIIα subunit. (H) Immunofluorescence microscopy on Daoy cells to evaluate the expression of PKA RIIα subunit. All experiments were performed at least twice.

Association of catalytic with regulatory subunit of PKA was affected by moxidectin

PKA is a tetramer enzyme that mediates its effects upon the binding of cAMP.31 (Figure 3F). To this end, our results indicated that moxidectin suppresses the cAMP-PKA pathway by inhibiting major players; however, the mechanism behind reduced PKA activity was not clear. We immunoprecipitated PKA catalytic subunit alpha protein (PKA Cα) from control and moxidectin-treated Daoy cell lysates and immunoblotted them using PKA regulatory II alpha subunit (PKA RIIα). Our results indicate that treatment of Daoy cells with 15 μM moxidectin considerably increased the association between the catalytic and regulatory subunits, as shown in Figure 3G, thereby reducing PKA activity. This effect of moxidectin can be attributed to reduced cAMP, i.e., when intracellular cAMP decreased after moxidectin treatment, less free cAMP was available to bind to the regulatory subunit in the cells. Similar observations were made by immunofluorescence studies, where 15 μM moxidectin treatment enhanced the cytoplasmic localization of PKA RIIα (Figure 3H). Taken together, these results indicate that moxidectin can inhibit the PKA pathway by promoting the association between the catalytic and regulatory subunits.

Moxidectin inhibits Gli1 and downstream cancer stem cell (CSC) markers expression

Canonical and non-canonical SHH signaling contributes significantly to the progression of, and therapy-resistant characteristics in, Daoy, UW426, UW228, ONS76, and PFSK1 MB cells. We evaluated the effects of moxidectin on Gli1, a major transcription factor of SHH signaling, in all MB cells. Treatment of MB cells with 10, 15, and 20 μM moxidectin resulted in a concentration-dependent robust inhibition of Gli1 in all cell lines. Notably, expression of major CSC markers downstream of Gli1 such as Pax6, Oct-4, Sox-2, and Nanog were also inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner with moxidectin treatment (Figure 4A). Western-blotting analysis of the nuclear fraction of Daoy cells confirmed that moxidectin treatment significantly reduced nuclear Gli1 (Figure 4B). Similar results were observed when immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on Daoy cells. Gli1 expression was reduced in Daoy cells treated with 15 μM moxidectin compared with the control group, as exhibited by green fluorescence (Figure 4C). CSCs impart medullosphere-forming characteristics to MB cells. Daoy and ONS76 cells were grown under medullosphere-forming conditions and treated with 7.5 μM moxidectin for 48 h. Our results revealed that the control cells formed spheres in both the cell lines; however, moxidectin treatment completely inhibited the sphere-forming ability of both Daoy and ONS76 cell lines (Figure 4D). These results further confirmed that moxidectin treatment inhibits the non-canonical activation of Gli1, which further results in reduced stem-cell-like properties of MB cells.

Moxidectin suppresses PKA activity induced by forskolin (FSK) in a CREB reporter assay

FSK, a diterpene, acts on adenylate cyclase, resulting in the activation of cAMP in the cells.32 Increased production of intracellular cAMP activates PKA activity, which phosphorylates the nuclear transcription factor CREB at Ser133. The activated transcription factor binds to the cAMP response element (CRE) on the promoter region of its target genes and mediates the activation of its downstream effector molecules.33 To establish cAMP-mediated PKA signaling as a target of moxidectin and a major player in MB progression, we pharmacologically activated CREB gene expression in ONS76 cells by stably infecting the cells with the CREB-luciferase (Luc) reporter gene. These cells contain the firefly Luc gene under the control of multimerized CRE. Elevated cAMP levels can activate CREB, which can form a dimer and bind to CRE, and can induce Luc, therefore mediating the effects of PKA. When ONS76 CREB-Luc cells were treated with 30 μM FSK for 48 h, an enhanced PKA activity was observed, as shown by increased luminescence in the FSK-treated group (Figure 5A). Interestingly, 15 μM moxidectin treatment alone did not induce the expression of CREB in ONS76 cells after 48 h of treatment. On the other hand, when ONS76 CREB-Luc cells were co-treated with 15 μM moxidectin and 30 μM FSK for 48 h, moxidectin inhibited the ability of FSK to induce PKA activation, as shown by reduced luminescence in Figure 5A. These results indicate that moxidectin mediates apoptotic effects by inhibiting PKA activation.

Figure 5.

Moxidectin suppresses FSK-induced PKA signaling, and pharmacologically inhibiting or silencing PKA and Gli1 enhances the effects of moxidectin

(A) ONS76 CREB Luc cells treated with FSK and/or moxidectin. The plate was read in an IVIS Imager, and the total flux was plotted using GraphPad Prism. The experiment was repeated three times. (B) Western blotting on FSK- and/or moxidectin-treated ONS76 cells. (C) Mice image on day 42, 96 h after 1 mg/kg FSK treatment. (D) Total flux measured before and after FSK and moxidectin treatment in ONS76 CREB Luc-bearing athymic nude mice. ∗p ≤ 0.05. (E) Western-blotting analysis for p-PKA substrate, Gli1, Sox2, and cleaved caspase-3 in Daoy, UW426, UW228, and ONS76 MB cells pre-treated with 30 μM H-89 and then treated with moxidectin for 48 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The figure is a representation of at least three replicates. (F) Western blotting for PKA Cα, p-CREB, p-PKA substrate, Gli1, and cleaved caspase-3 in UW426 and ONS76 MB cells pre-treated with PKA Cα siRNA and then treated with moxidectin for 48 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The figure is a representation of at least three independent experiments with similar observations. (G) Western blotting for Gli1, Pax6, Sox2, cleaved PARP, and cleaved caspase-3 in UW426, UW228, and Daoy MB cells pre-treated with 15 μM GANT61 and then treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (H) Western-blotting analysis for Gli1, Pax6, Sox2, and cleaved caspase-3 in Daoy and UW228 cells. Cells were pre-treated with 100 nM Gli1 siRNA and then treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The figure is a representation of at least three independent experiments with similar observations.

These observations were also validated using western blotting, where ONS76 cells were treated with 30 μM FSK and 15 μM moxidectin. Our results indicated that treatment with FSK induced PKA activity and p-CREB; however, it did not have a significant effect on the induction of apoptosis compared with control (Figure 5B). On the other hand, moxidectin treatment inhibited PKA activity and also suppressed the phosphorylation of CREB along with the induction of apoptosis, as shown by an increase in the cleavage of caspase-3 (Figure 5B). These results confirmed that in MB, PKA acts as a tumor promoter. To extend our observations and confirm the effects of moxidectin on the cAMP-PKA pathway in vivo, 4.0 × 106 ONS76 CREB-Luc cells were implanted subcutaneously on the right flank of athymic nude mice. The total luminescence of mice was measured every other day. Once stable luminescence was observed in all mice, they were randomized on day 19 into control and treatment groups. The control group of mice received vehicle, whereas the treatment group of mice received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin by oral gavage every day. On day 38, both the control and treatment groups received 1 mg/kg FSK. After 48 h of FSK treatment, the control group exhibited a total flux of 2.79 × 106 photons per second, whereas the moxidectin-treated group displayed a total flux of only 0.288 × 106 photons per second (Figures 5C and 5D), indicating a 90% inhibition of PKA activity in the in vivo tumor model (Figure 5D). These results further validated our hypothesis that moxidectin mediates its effects by inhibiting PKA activity.

Inhibiting or silencing PKA Cα potentiates the effects of moxidectin

The PRKACA gene regulates PKA Cα. This enzyme is responsible for phosphorylating the substrates of PKA and thereby regulating its activity. Additionally, PKA also controls cell metabolism and division.34, 35, 36 To establish PKA as a target of moxidectin in MB cells, PKA was inhibited in Daoy, UW426, UW228, and ONS76 MB cells using H-89, a pharmacological inhibitor of PKA. Interestingly, blocking the activation of PKA by H-89 resulted in the suppression of PKA activity, as shown by the reduced expression of PKA Cα, p-PKA substrate, Gli1, and Sox2 and the enhanced cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP in all cell lines (Figure 5E). In another experiment, PKA Cα was knocked down using PKA Cα small interfering RNA (siRNA) in UW426 and ONS76 MB cell lines. Knocking down PKA Cα resulted in significantly reduced expression of PKA and p-PKA substrate, phosphorylation of p-CREB at Ser133, and Gli1 expression. In addition, silencing PKA Cα induced apoptosis, which was indicated by the cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP. Moreover, the apoptosis-inducing effects of moxidectin were significantly enhanced in PKA Cα siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 5F). These results again indicate that the growth-suppressive effects of moxidectin in pediatric MB were mediated through inhibition of PKA signaling.

Inhibiting or silencing Gli1 enhances the effects of moxidectin

Treatment of Daoy, UW228, and UW426 cells with GANT61, a pharmacological inhibitor of Gli1, inhibited the expression of the markers of stem cells such as Pax6 and Sox2 in MB cells. Additionally, enhanced inhibition of Gli1, Pax6, and Sox2 was observed in moxidectin-treated cells pre-treated with GANT61 (Figure 5G). Similarly, treatment of Gli1 siRNA-transfected Daoy and UW228 cells with moxidectin further reduced the expression of Pax6 and Sox2 compared with moxidectin treatment alone (Figure 5G). The apoptosis-inducing effects of moxidectin were also augmented in cells when combined with GANT61 pre-treatment or Gli1 siRNA transfection (Figure 5H). These results established the significance of Gli1 in the overall effectiveness of moxidectin.

Moxidectin suppresses the growth of subcutaneously implanted MB tumors

To investigate the in vivo efficacy of moxidectin and to further evaluate the mechanism of MB growth suppression, Daoy cells were subcutaneously implanted in the right flank of female athymic nude mice. Once the tumor volume reached ∼80 mm3, mice were randomized into two groups, and the treated group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin every day by oral gavage, whereas the control group of mice received vehicle only. Our results indicate that by the last day of experiment, moxidectin treatment inhibited ∼60% tumor growth (Figures 6A–6C). Oral administration of moxidectin did not cause any toxicity, as no change in mice body weight during the course of the study was observed (Figures 6D and 6E). The tumor lysates from control and treatment mice were analyzed by western blotting. Our results indicate that moxidectin treatment induced the overall expression of GABAA receptor. Additionally, moxidectin treatment reduced p-PKA Cα, p-PKA substrate, and p-CREB, the major players of cAMP-PKA signaling (Figure 6F). Furthermore, tumors from moxidectin-treated mice exhibited reduced expression of Gli1 and the major stem cell markers Pax6 and Sox2. In addition, moxidectin treatment increased the cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP in MB tumors (Figures 6G and 6H). The excised tumors were subjected to ex vivo analysis using immunohistochemistry (IHC) and TUNEL staining. Our IHC analysis supports the observations made in the in vitro studies: that moxidectin induced apoptosis and mediated its anti-cancer effects in vivo by suppressing PKA-Gli1 signaling (Figures 6I–6K).

Figure 6.

Moxidectin suppresses the growth of subcutaneously implanted Daoy MB tumors

(A) Tumor curve representing the growth of subcutaneously implanted MB tumors in control versus 2.5 mg/kg-moxidectin-treated mice. (B) Average tumor weight recorded on the last day of experiment. (C) Representative images of tumors on the day of termination of the experiment. (D) Mice weight throughout the course of study. (E) Mice weight on the last day of the study. (F and G) Western blotting of control and Daoy tumor lysates for the expression of GABAA R, p-PKA Cα (Thr197), p-PKA substrate, p-CREB (Ser133), Gli1, Pax6, Sox2, cleaved PARP, and cleaved caspase-3. Each lane represents each tumor. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (H) Quantitation of western-blotting data from Image 6G. (I) IHC representing induction of cleaved caspase-3 with moxidectin treatment. (J) TUNEL assay to evaluate the induction of apoptosis in moxidectin-treated MB tumors. (K) IHC confirming the observations made in Figures 6F and 6G. All IHC and TUNEL assay images were taken at 40× magnification.

In another experiment, approximately 4 × 106 ONS76 cells were injected subcutaneously on the left frank of male athymic nude mice. Once the tumor volume reached ∼90 mm3, mice were randomized into control and treatment groups. The control group received vehicle, whereas the treatment group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin daily by oral gavage. Our results indicate that moxidectin treatment inhibited 70% of subcutaneously implanted ONS76 tumors (Figures 7A and 7B). Additionally, daily administration of moxidectin did not alter mice weight (Figure 7C). Western blotting, IHC, and TUNEL assay confirmed that moxidectin induces apoptosis and mediates its anti-neoplastic effects by suppressing PKA-Gli1 signaling in vitro and in vivo. These results also indicate that PKA-Gli1 signaling has a tumor-promoting role in MB and that moxidectin mediates growth-suppressive effects by inhibiting this signaling axis (Figures 7D–7G). Overall, our results demonstrated that moxidectin suppressed the tumor growth of two different MB cells and was equally effective in male and female mice.

Figure 7.

Moxidectin suppresses the growth of subcutaneously implanted ONS76 tumors

(A) Tumor-growth curve throughout the course of study. The treated group of mice was administered 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin by oral gavage every day. (B) Tumor weight on the last day of experiment. (C) Mice weight throughout the course of study. (D) Western blotting on the whole-tumor lysates of both control and treatment groups. Each lane represents an individual mouse tumor. (E) Quantitated data from Image 7D. (F) TUNEL assay showing the induction of apoptosis upon moxidectin treatment. (G) IHC analysis on ONS76 tumors. All IHC and TUNEL assay images were taken at 40× magnification.

Moxidectin inhibits the growth of intracranially implanted MB tumors

MB tumors originate in the cerebellum of the brain. Therefore, in order to mimic the clinically relevant condition of PBTs, we injected Daoy-Luc MB cells intracranially in the bregma of female athymic nude mice. On day 9 post injection, mice were randomized into control and treatment groups once significant luminescence was achieved in the cranium of all mice. The control group received vehicle, and the treatment group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin orally every day. The experiment was terminated on day 33 due to excessive tumor burden and spinal cord metastasis in the control group. On the last day of the experiment, control mice displayed 8.4 × 108 total flux, whereas treatment mice had 1.7 × 108 total flux, indicating an 80% inhibition of intracranial MB tumors by moxidectin (Figures 8A and 8B). The general signs of toxicity in the moxidectin group were assessed through mice weight. We did not observe any significant change in mice body weight throughout the course of the study with chronic administration of moxidectin (Figure 8C). Our results showed reduced weight of the brain in response to moxidectin treatment (Figure 8D). Daoy-Luc tumor lysates were subjected to western blotting. Our results indicate that the levels of p-PKA Cα, p-CREB, Pax6, and Sox2 were reduced in the moxidectin-treated group (Figure 8D). IHC analysis confirms the inhibition of p-CREB upon moxidectin treatment, and TUNEL assay showed induction of apoptosis (Figure 8F).

Figure 8.

Moxidectin suppresses intracranially implanted Daoy-Luc cells

(A) Daoy-Luc cells were orthotopically injected in the brain of the athymic nude mice, and treatment group was administered 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin every day orally. Tumor luminescence was measured approximately twice a week and plotted against days (n = 10). (B) Mice-brain luminescence on days 0, 8, and 33. (C and D) Mice weight and brain luminescence on the day of termination. (E) Western blotting on the whole-brain lysates of both control and treatment groups for p-PKA Cα, p-CREB, Pax6, and Sox2. β-actin was used as a loading control. (F) IHC and TUNEL assays confirming the inhibition of p-CREB and induction of apoptosis in intracranial MB tumor model. All IHC and TUNEL assay images were taken at 40× magnification.

Chronic administration of 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin did not show any signs of toxicity

The organ-weight and blood-chemistry parameters of both control and moxidectin-treated mice were analyzed to evaluate any general signs of toxicity. Our results indicate that moxidectin treatment did not cause any change in the weight of critical organs such as brain, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, and pancreas (Figure S1). Additionally, the blood-chemistry parameters remained unchanged after daily administration of moxidectin for 33 days (Figure S1). Overall, our results indicate that chronic administration of moxidectin did not display any general signs of toxicity.

Discussion

Studies on MB have emphasized identifying prognostic markers or the molecular mechanisms that govern MB progression to help establish an effective treatment regimen for MB patients.37 Our current study focused on (1) delineating the molecular mechanism that governs the progression of SHH dominant subgroup of MB and (2) inhibiting those pathways using moxidectin.

Neurotransmitters mediate their effects by binding to specific receptors, thereby either activating or inhibiting several neurological functions.38 Notably, emerging scientific evidence suggests that cancer cells exploit the signaling initiated by neurotransmitters and promote tumorigenesis.38 Treatment of CSCs with epinephrine increased their self-renewal potency along with increased intracellular cAMP and hyperactivated SHH signaling in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).13 Similar observations were made in pancreatic cancer, where treatment with GABA reduced the self-renewal properties of CSCs.39 Our genomic analysis on clinical databases indicated that MB patients have reduced expression of GABAA receptor along with overexpression of genes regulating cAMP-PKA-Gli1 signaling. Additionally, high expression of PRKACA and Gli1 was associated with overall reduced survival of MB patients. In agreement, our study indicated that ectopic over-expression of GABAA receptor resulted in the inhibition of Gli1 and the induction of apoptosis in UW426 MB cells. These results implied the role of GABAA receptor in the progression of MB and the potential role of GABAA agonist in the management of MB. Although, several neurotransmitter agonists have been shown to possess anti-cancer ability, the mechanisms governing their anti-cancer effects have been left unexplored. Owing to the role of SHH signaling in MB progression and the significance of GABAA receptor in CSC renewal, in this study, we have established the anti-neoplastic effects of an anti-helminthic drug, moxidectin. As an anti-parasitic drug, moxidectin meditates its effects by acting as an agonist of GABAA.40

cAMP-PKA signaling can have both tumor-suppressive and -promoting roles depending upon the context and tumor type. Hence, the role of CREB-activating cAMP-PKA-Gli1 signaling in tumorigenesis has been paradoxical. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), activation of the PKA-CREB pathway promotes HCC progression.30 On the other hand, in glioblastoma (GBM), PKA has been shown to play a tumor-suppressive role, where it reduced the proliferation of A-172 cells by increasing intracellular cAMP and up-regulating the expression of p21 and p27.41,42 On the contrary, in the human GBM cell line MGR3, hyperactivation of PKA led to the phosphorylation of GSTP, resulting in drug resistance and treatment failure.17 Similarly, few studies have showcased the role of PKA in transforming human neural stem cells to GBM stem cells.43 Conclusively, cAMP being an evolutionarily conserved second messenger plays a critical role in cellular processes. Therefore, the function of cAMP as a tumor suppressor or promoter depends significantly on the cell type and the cellular environment.43 Our study indicates that GABAA receptor agonist moxidectin inhibited cAMP-PKA signaling in MB cells. Moxidectin treatment suppressed the production of intracellular cAMP in MB cells, as indicated by ELISA and immunoblotting studies. Inhibition of cAMP was followed by reduced expression of PKA-Cα and p-PKA Cα (Thr 197) (an indicator of its biological function), suppressed PKA activity, as observed by reduced phosphorylation of PKA substrates, and enhanced interaction between PKA catalytic and regulatory subunits. These observations suggest that moxidectin mediates PKA inhibitory effects by suppressing the production of cAMP and then promoting the interaction between catalytic and regulatory subunits. The activation of the PKA pathway has been clinically linked with enhanced activity of the MDR1 gene.20 Therefore, we evaluated the effects of moxidectin on the expression of MDR1 in MB cells. Our results indicate that moxidectin significantly inhibits the expression of MDR1 in a concentration-dependent manner. These findings highlight the clinical significance of PKA inhibitors for MB patients.

SHH signaling is essential for embryonic development; however, aberrant activation of this signaling is linked with the pathogenesis of numerous cancers. In MB, SHH can be activated in a SMO-dependent or -independent manner.44 Over the past couple of years, Vismodegib (GDC-0449) and Sonidegib (LDE225) were approved by the FDA. These two are primarily the only drugs targeting the SHH pathway in MB; however, toxicity and treatment failure pertaining to acquired drug resistance has been a challenge for these drugs.45, 46, 47 Beyond the classical PTCH-SMO route of MB progression, there are several non-canonical mechanisms independent of SMO that can potentially regulate Gli1 and CSC activation. Some evidence indicates that tumors harboring non-canonical Gli1 activation might be less sensitive to SMO inhibitors.7 In our study, moxidectin significantly inhibited Gli1 and subsequently suppressed the expression of major CSC markers like Pax6, Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog. The effect of moxidectin in terms of inhibiting Gli1 and downstream effector molecules were enhanced when Gli1 was inhibited by GANT61 or siRNA, indicating it as a target.

In the context of MB, PKA has been reported to play the role of a tumor suppressor, wherein it can mediate its effects by acting as a suppressor of Gli1 signaling. However, the dual role of PKA in MB has not been established yet. Our studies established the pro-tumorigenic role of cAMP-PKA in pediatric MB. Inhibiting PKA by H-89 or knocking it down with PKA Cα siRNA resulted in the inhibition of Gli1 and downstream CSCs. Interestingly, the inhibition or silencing of PKA further potentiated the effects of moxidectin in inhibiting PKA-Gli1 signaling inducing apoptosis, indicating PKA as a potential target of moxidectin in MB. FSK, a PKA agonist, is known to significantly activate CREB in vitro and in vivo. Scientific evidence indicates that FSK increases the cytoplasmic accumulation of Gli1 and suppresses its downstream mediators. In our study, treatment of ONS76 MB cells with FSK induced PKA and CREB activity but did not have much effect on Pax6, a downstream marker of non-canonical Gli1 signaling. Nonetheless, treatment with moxidectin reduced the activity of CREB induced by FSK and induced apoptosis in MB cells in both cell and mice tumor models. In vivo efficacy of moxidectin was established in three independent tumor models. Oral administration of moxidectin suppressed the progression of MB tumors in both subcutaneously and intracranially implanted brain tumors in mice. Suppression of subcutaneous and intracranial MB tumors by moxidectin was associated with induced overexpression of GABAA receptor and inhibition of PKA-Gli1 signaling. From a clinical standpoint, the anti-cancer oral dose of moxidectin (2.5 mg/kg) used in our experiments for 50 days was safe and without any general signs of toxicity. Most importantly, the anti-cancer dose of moxidectin administered in this study was 2.88 times lower than the well-tolerated dose of ∼0.6 mg/kg moxidectin in humans.48

Overall, in this study, we have established that GABAA receptor, upon its activation, inhibits PKA activity and consequently suppresses the non-canonical Gli1 activation in the SHH-dominant subgroup of MB and demonstrated that the progression of MB can be through two interdependent factors: GABAA receptor and cAMP-mediated PKA-Gli1 signaling. In addition, our studies established that moxidectin enhances the expression of GABAA receptor and displayed significant anti-proliferative, anti-clonogenic, and apoptotic effects by inhibiting PKA-Gli1 signaling.

To the best our knowledge, this is the first study to establish the role of GABAA receptor and its downstream PKA-Gli1 signaling in pediatric MB progression. In addition, our study demonstrated that the anti-helminthic drug moxidectin can suppress MB tumor growth by inhibiting the PKA-Gli1 signaling axis (Figure S2). A detailed toxicity profile of moxidectin can be established by evaluating its effects on white blood cells (WBCs) and the locomotor and behavioral activity of mice, which will further validate our findings. From a mechanism standpoint, this study, for the first time, has showcased the role of PKA as a tumor promoter. More studies can be performed to identify its role in the progression of other cancers.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

Mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility of Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC; Abilene, TX, USA). All experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards. The mice studies were performed under the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of TTUHSC.

Cell culture

All cell lines were maintained at 37°C in humidified incubators with 5% CO2. The pediatric desmoplastic MB cell line Daoy was obtained from ATCC (ATCCHTB-186) and maintained in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture. The Daoy.firefly (ff)Luc cell line was a generous gift from Dr. Leonid S. Metelista from Boston College of Medicine. Daoy-Luc cells were maintained in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture. Human pediatric MB cell lines ONS76 and UW228 were a kind gift from Dr. Rajeev Vibhakar from the University of Colorado School of Medicine (Aurora, CO, USA). The UW426 MB cell line was a benevolent gift from Dr. Raffel Corey from the University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, CA, USA). UW228 and UW426 cells were maintained in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture. ONS76 cells were maintained in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mL/L glucose. The primitive neuroectodermal cell line PFSK1 was a generous gift from Dr. Ruman Rahman from the University of Nottingham Medical School. PFSK1 cells were maintained in RPMI media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin antibiotic mixture. Quality control of the cells was performed by using a Colorimetric Mycoplasma detection kit. The cell lines were authenticated by shrot tandem repeat (STR) verification and were used within 20 passages.

Cell-survival assay

Cell lines were seeded at a density of ∼4,000–5,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate. The cells were treated with different concentrations of moxidectin for 24, 48, and 72 h. After each time point, the cells were fixed with 10% ice-cold trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at least overnight and then processed for a sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay, as described by us previously.11,26 The plates were read at an emission wavelength of 570 nm using a Cytation5 imaging reader, and the data were plotted using Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All experiments were repeated independently at least three times with several replicates.

AnnexinV-APC apoptosis assay

Briefly, 0.2 × 106 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate. After 24 h of cell seeding, cells were treated with 10–20 μM moxidectin for 48 h and processed for apoptosis measurement as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were analyzed using a BD LSR Fortessa flow cytometer, and the data were quantitated using FlowJo single-cell analysis software v.10. All experiments were repeated independently at least three times.

Clonogenic assay

Approximately 500 cells of Daoy, UW228, and UW426 were seeded in a 6-well plate. Twenty-four h after seeding, cells were treated with 7.5, 10, and 15 μM sub-toxic concentrations of moxidectin. After 48 h of moxidectin treatment, media in each well were replenished with fresh cell-specific medium and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 2 weeks or until significantly larger colonies were observed in the control group. On the day of termination, colonies were washed twice with 1X PBS, fixed with 10% ice-cold TCA overnight, and stained with 0.4% SRB. The colonies were quantitated using ImageJ software and plotted using Prism 8 software. All experiments were repeated independently at least three times.

Medullosphere-formation assay

Daoy and ONS76 MB cells were plated in 6-well ultra-low attachment plates at a concentration of 500 cells/well. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor (EGF), 5 mg/mL insulin, 2% B-27 supplement, and 20 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). After overnight incubation, cells were treated with 7.5 μM moxidectin. After 48 h, media in each well were diluted three times, and the cells were allowed to form spheres for 10–15 days or until fully formed spheres were observed in the control group. Medulloshpere images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E microscope. All experiments were repeated independently at least three times.

Immunoblotting

Daoy, UW228, UW426, ONS76, and PFSK1 cells were seeded at a density of 0.7 × 106 cells in a Petri dish. After 24 h of incubation, cells were treated with 10, 15, and 20 μM moxidectin for 48 h. After 48 h, cells were collected using a cell scraper and washed twice with ice-cold PBS. The cells were then lysed using Tris-EDTA lysis buffer for at least 1 h. The lysates were quantitated using Bradford reagent, and equal concentrations (40 μg) of each sample were analyzed using SDS-PAGE. The proteins were resolved on a methanol-activated -polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and probed for respective antibodies (Table S1). The membranes were developed as described by us previously.49 Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Pharmacological inhibitor treatment

Briefly, 0.7 million cells were seeded in a Petri dish and allowed to attach overnight. The following day, cells were pre-treated with 15 μM GANT61, a Gli1 inhibitor, or 30 μM H-89, a PKA inhibitor, for 24 h. After 24 h of treatment, cells were treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h and further processed for western blotting.

cAMP ELISA assay

Briefly, 0.7 × 106 cells were seeded in a Petri dish and allowed to attach overnight. Twenty-four h later, cells were treated with 7.5, 10, 15, and 20 μM moxidectin for 24 h. Post treatment cells were processed, and ELISA assay was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The data were quantitated as per the manufacturer’s instruction and plotted using Prism 8 software.

siRNA and plasmid transfection

Gene silencing was performed using Lipofectamine RNAi Max transfection reagent at 100 nM concentration as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were passaged a day before, and the following day, 0.2 × 106 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate with a confluency of 70%–80%. Lipofectamine and siRNA were diluted in Opti-MEM serum-free medium and added dropwise at a 1:1 ratio to the cells. The cells were kept overnight with the siRNA, and the following day, the cells were treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h. After 48 h, cells were processed for western blotting as described before.

GABAA receptor plasmid was obtained from Addgene. The plasmid was expanded under ampicillin resistance in Luria broth and extracted using the Zymo plasmid isolation kit (Table S1). For GABAA receptor plasmid transfection, UW426 cells were passaged a day before and were seeded the following day at a density of 0.2 × 106 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. After incubation, cell media were replaced with serum-free media, and plasmid transfection was performed using Xfect transfection reagent. The cells were transfected with 5 μg GABAA-receptor-expressing plasmid or control (empty) plasmid and incubated overnight. After overnight incubation, serum-starved medium was replaced with complete cell medium, and 48 h after media replacement, cells were processed for western blotting.

Immunoprecipitation

Roughly, 0.7 × 106 cells were seeded in a Petri dish and incubated overnight. The following day, cells were treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h. After 48 h, cells were collected and lysed using immunoprecipitation lysis buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The amount of protein in cells lysates was quantitated using Bradford reagent. Magnetic beads (1.5 mg) were washed and incubated with the PKARII antibody for 10 min at 4°C as per the manufacturer’s protocol. The beads were then washed once with 1X PBS, and equal amounts of lysate (500 μg) from both control and treatment groups were incubated with 1.5 mg beads/sample at 4°C on a rotator for 15 min. After incubation, the bead-Ab-Ag complex was washed three times using 1X PBS, and the sample was eluted using elution buffer at 95°C for 10 min. The samples were then analyzed using immunoblotting analysis as described above.

Immunofluorescence

Approximately 0.2 × 106 cells were seeded on a poly-L-lysine-coated coverslip and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. After incubation, cells were treated with 15 μM moxidectin for 48 h. For analysis, the coverslips were washed twice with 1X PBS and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min at room temperature. After fixing, cells were washed with 1X PBS three times for five minutes each. The cells were then permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After permeabilization, cells were washed with 1X PBS three times for 5 min each. The coverslips were then blocked with goat serum (1%) and Tween 20 (0.25%) for 1 h. Primary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer, and the coverslips were incubated overnight in the dark. The next morning, cells were washed three times and incubated with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 secondary antibody diluted at a ratio of 1:1,000 in goat serum (3%) and BSA (0.5%). After secondary antibody incubation, cells were washed and incubated in Alexa Fluor 599 phalloidin (1:500) in 3% BSA for 15 min, and the coverslips were mounted on a glass slide using 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) mounting medium. The images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-E confocal microscope.

IHC

The excised tumors were kept in 10% formalin overnight. The following day, formalin was replaced with 70% ethanol. To obtain formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks, samples were processed using a Leica TP 1020 tissue processor as per the established protocol. The FFPE tumors were then sliced in 5-μm-thin slices using a microtome and kept on a slide warmer overnight. Later, the slides were processed as per the manufacturer’s protocol (UltraVision ONE Large Volume Detection System HRP Polymer).

TUNEL assay

The FFPE slides obtained from IHC processing, as discussed above, were subjected to TUNEL assay as per the manufacturer’s protocol (FragEL TM DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit, Colorimetric-TdT Enzyme).

In vivo studies

Daoy subcutaneous xenograft model

About 4- to 6-week-old Foxn1nu homozygous female athymic nude mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock no. 002019). Upon receipt, mice were housed in the TTUHSC animal facility for almost a week for acclimatization. 7 × 106 Daoy cells were injected in the right flank of the mice in 1:1 PBS:matrigel mixture using a 31G needle. Once the tumor volume reached 70–100 mm3, mice were randomized into control and treatment groups (n = 7 in each group), where the control group received vehicle (0.05% DMSO, 0.05% Tween 80, 99.9% 1X PBS) and the treatment group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin by oral gavage every day until the last day of the experiment. Mice weight was measured every 10 to 15 days. The tumor volume was measured every 4th or 5th day using a Vernier caliper. The experiment was terminated on day 50 due to excessive tumor burden in control mice. On the day of termination, mice were humanely euthanized, and tumors were aseptically removed. The excised tumors were snap frozen for western blotting or fixed in 10% formalin for ex vivo analysis.

Daoy-Luc intracranial orthotopic xenograft model

Foxn1nu homozygous female athymic nude mice (4–6 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and fixed on a stereotaxic apparatus (Stoelting, cat. no. 51730) using the anesthesia mask and ear bars. Daoy.ffLuc cells were collected and washed with 1X PBS twice. After cell counting, a cell suspension containing 0.3 × 106 Daoy.ffLuc in 5 μL 1X PBS was injected 5 mm deep intracranially using a 31.5G syringe in the bregma of mice. After 8 days, when significant luminescence was observed in all the mice, they were randomized into control and treatment groups (n = 10 mice in each group). The control group received vehicle (0.05% DMSO, 0.05% Tween 80, 99.9% 1X PBS) and the treatment group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin suspended in vehicle every day by oral gavage. The tumor progression was evaluated every other day using a non-invasive in vivo live animal imaging system (IVIS Imager). The experiment was terminated on day 33 due to metastasis and tumor burden in the control group of mice by euthanizing the mice in a CO2 chamber. The mice brain was carefully excised and stored for ex vivo analysis.

ONS76 subcutaneous xenograft model

Four- to six-week-old Foxn1nu heterozygous male athymic nude mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock no. 002019). Briefly, 4 × 106 cells were subcutaneously injected on the right flank of the mice. Once significant tumor volume was achieved in all mice, mice were randomized into control and treatment groups (n = 5 in each group). The control group received vehicle, whereas the treatment group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin by oral gavage every day. Once significant tumor inhibition was observed in the treatment group, the experiment was terminated. The mice were euthanized, and the tumors were aseptically removed. After taking the weight, tumors were frozen for ex vivo analysis.

CREB Luc reporter assay

In order to generate the CRE/CREB Luc reporter cell line, 3.5 × 104 ONS76 cells were seeded in 500 μL cell culture media in a 24-well plate. Twenty-four h post seeding, cells were supplemented with an additional 1.5 mL of cell media. The cells were transduced at different multiplicities of infection (MOIs), i.e., 5, 10, and 15, using polybrene at a final concentration of 8 μg/mL. The cells were left overnight with the lentivirus particles, and the following day, media was replaced with fresh cell culture media. The cells were monitored for 3 to 4 days under standard cell culture conditions. Once an optimum number of cells were observed, the cells were subjected to 5 μM puromycin selection. An MOI of 10 was identified to be the most effective transfection MOI for ONS76 MB cells. Henceforth, ONS76 CRE/CREB Luc cells were maintained in 5 μM puromycin throughout the course of study.

In vitro CRE/CREB Luc reporter assay study

Briefly, 0.2 × 106 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate, and the following day, cells were co-treated with 30 μM of FSK and 15 μM of moxidectin for 48 h. The next day, CRE/CREB activation was evaluated by adding D-luciferin to the cells, and images were taken and quantitated using IVIS Imager.

In vivo CRE/CREB Luc reporter study

Four- to six-week-old Foxn1nu heterozygous male athymic nude mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock no. 002019). Briefly, 4 × 106 ONS76 CREB Luc cells were subcutaneously injected on the left flank of the mice. The luminescence of the tumors was measured using the IVIS Imager starting on day 0. The tumor volume was measured every other day using a vernier caliper. Once significant tumor volume was achieved in all mice, animals were randomized into control and treatment groups. The control group received vehicle, and treatment group received 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin by oral gavage every day. On day 38, control and treatment groups received 1 mg/kg FSK (0.05% DMSO, 0.05% Tween 80, 99.9% 1X PBS) intraperitoneally. CREB gene expression with moxidectin treatment was monitored by injecting 3 mg/kg D-luciferin intraperitoneally every day after FSK treatment. Once significant gene inhibition was observed in the treatment group compared with the control group, the experiment was terminated, and tumors were aseptically removed.

Clinical-chemistry-parameter evaluation

After chronic administration of 2.5 mg/kg moxidectin, mice blood was sent to Hendricks Regional Hospital (Abilene, TX, USA) for analysis. The critical blood parameters like creatine kinase (CK), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), cholesterol, urea, creatinine, phosphorous, alkaline phosphatase (AlkP), total bilirubin, total protein, glucose, calcium, Cl-C, K-C, Na-C, amylase, and albumin Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) were measured to evaluate any general signs of toxicity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Prism 7 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Each experiment was repeated at least three times independently unless otherwise noted. In vitro results are presented as mean ± standard deviations (SDs), and in vivo studies are presented as standard error of means (SEMs). Unless otherwise stated, statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t test followed by Fisher’s f test. The outcomes with a p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human subjects were not used in this study. All pre-clinical investigations involving animals were carried out in line with the ethical standards and according to the approved protocol by IACUC.

Consent for publication

The authors give their consent to publish this data.

Data availability

The authors agree to make this data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by R01 grant CA129038 (to S.K.S.) awarded by the National Cancer Institute, NIH. The Syngenta Fellowship Award in collaboration with the Society of Toxicology to I.K. is acknowledged. The authors also appreciate the funding from Dodge Jones Foundation (Abilene, TX, USA). We would like to acknowledge Drs. Leonid S. Metelista, Rajeev Vibhakar, Raffel Corey, and Ruman Rahman for generously providing the MB cell lines.

Author contributions

Conception and design, I.K. and S.K.S.; development of methodology, I.K. and S.K.S.; acquisition of data, I.K.; analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis), I.K. and S.K.S.; writing – review and/or revision of the manuscript, I.K. and S.K.S.; administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing data, constructing databases), S.K.S.; study supervision, S.K.S.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.03.012.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Gurney J.G., Kadan-Lottick N. Brain and other central nervous system tumors: rates, trends, and epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2001;13:160–166. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200105000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomeroy S.L., Tamayo P., Gaasenbeek M., Sturla L.M., Angelo M., McLaughlin M.E., Kim J.Y., Goumnerova L.C., Black P.M., Lau C., et al. Prediction of central nervous system embryonal tumour outcome based on gene expression. Nature. 2002;415:436–442. doi: 10.1038/415436a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho Y.J., Tsherniak A., Tamayo P., Santagata S., Ligon A., Greulich H., Berhoukim R., Amani V., Goumnerova L., Eberhart C.G., et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:1424–1430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuller H.M., Al-Wadei H.A. Neurotransmitter receptors as central regulators of pancreatic cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:221–228. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor M.D., Northcott P.A., Korshunov A., Remke M., Cho Y.J., Clifford S.C., Eberhart C.G., Parsons D.W., Rutkowski S., Gajjar A., et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:465–472. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0922-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kogerman P., Grimm T., Kogerman L., Krause D., Unden A.B., Sandstedt B., Toftgård R., Zaphiropoulos P.G. Mammalian suppressor-of-fused modulates nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Gli-1. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:312–319. doi: 10.1038/13031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pietrobono S., Gagliardi S., Stecca B. Non-canonical hedgehog signaling pathway in cancer: activation of GLI transcription factors beyond smoothened. Front. Genet. 2019;10:556. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramachandran S., Srivastava S.K. Repurposing pimavanserin, an anti-Parkinson drug for pancreatic cancer therapy. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics. 2020;19:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2020.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Po A., Silvano M., Miele E., Capalbo C., Eramo A., Salvati V., Todaro M., Besharat Z.M., Catanzaro G., Cucchi D., et al. Noncanonical GLI1 signaling promotes stemness features and in vivo growth in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2017;36:4641–4652. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shibata M., Hoque M.O. Targeting cancer stem cells: a strategy for effective eradication of cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:732. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selvadurai H.J., Luis E., Desai K., Lan X., Vladoiu M.C., Whitley O., Galvin C., Vanner R.J., Lee L., Whetstone H., et al. Medulloblastoma arises from the persistence of a rare and transient Sox2(+) granule neuron precursor. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107511. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Wadei M.H., Banerjee J., Al-Wadei H.A., Schuller H.M. Nicotine induces self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells via neurotransmitter-driven activation of sonic hedgehog signalling. Eur. J. Cancer. 2016;52:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banerjee J., Papu John A.M., Schuller H.M. Regulation of nonsmall-cell lung cancer stem cell like cells by neurotransmitters and opioid peptides. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:2815–2824. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuller H.M. Neurotransmitter receptor-mediated signaling pathways as modulators of carcinogenesis. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 2007;39:45–63. doi: 10.1159/000100045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuller H.M. A new twist to neurotransmitter receptors and cancer. J. Cancer Metastasis Treat. 2017;3:71–77. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H., Sun T., Hu J., Zhang R., Rao Y., Wang S., Chen R., McLendon R.E., Friedman A.H., Keir S.T., et al. miR-33a promotes glioma-initiating cell self-renewal via PKA and NOTCH pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:4489–4502. doi: 10.1172/JCI75284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo H.W., Antoun G.R., Ali-Osman F. The human glutathione S-transferase P1 protein is phosphorylated and its metabolic function enhanced by the Ser/Thr protein kinases, cAMP-dependent protein kinase and protein kinase C, in glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:9131–9138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caretta A., Mucignat-Caretta C. Protein kinase a in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:913–926. doi: 10.3390/cancers3010913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziemann C., Riecke A., Rudell G., Oetjen E., Steinfelder H.J., Lass C., Kahl G.F., Hirsch-Ernst K.I. The role of prostaglandin E receptor-dependent signaling via cAMP in Mdr1b gene activation in primary rat hepatocyte cultures. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;317:378–386. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung F.S., Santiago J.S., Jesus M.F., Trinidad C.V., See M.F. Disrupting P-glycoprotein function in clinical settings: what can we learn from the fundamental aspects of this transporter? Am. J. Cancer Res. 2016;6:1583–1598. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaushik I., Ramachandran S., Prasad S., Srivastava S.K. Drug rechanneling: a novel paradigm for cancer treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021;68:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta N., Srivastava S.K. Atovaquone: an antiprotozoal drug suppresses primary and resistant breast tumor growth by inhibiting HER2/beta-catenin signaling. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019;18:1708–1720. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-18-1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranjan A., Srivastava S.K. Penfluridol suppresses glioblastoma tumor growth by Akt-mediated inhibition of GLI1. Oncotarget. 2017;8:32960–32976. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranjan A., Kaushik I., Srivastava S.K. Pimozide suppresses the growth of brain tumors by targeting STAT3-mediated autophagy. Cells. 2020;9:2141. doi: 10.3390/cells9092141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallay L., Keskin H., Ross A., Rupji M., Moody O.A., Wang X., Li G., Ahmed T., Rashid F., Stephen M.R., et al. Modulating native GABAA receptors in medulloblastoma with positive allosteric benzodiazepine-derivatives induces cell death. J. Neurooncol. 2019;142:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s11060-019-03115-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Awadzi K., Opoku N.O., Attah S.K., Lazdins-Helds J., Kuesel A.C. A randomized, single-ascending-dose, ivermectin-controlled, double-blind study of moxidectin in Onchocerca volvulus infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014;8:e2953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menez C., Sutra J.F., Prichard R., Lespine A. Relative neurotoxicity of ivermectin and moxidectin in Mdr1ab (-/-) mice and effects on mammalian GABA(A) channel activity. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012;6:e1883. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen A.Y., Sakamoto K.M., Miller L.S. The role of the transcription factor CREB in immune function. J. Immunol. 2010;185:6413–6419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Wadei H.A., Plummer H.K., 3rd, Schuller H.M. Nicotine stimulates pancreatic cancer xenografts by systemic increase in stress neurotransmitters and suppression of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:506–511. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovach S.J., Price J.A., Shaw C.M., Theodorakis N.G., McKillop I.H. Role of cyclic-AMP responsive element binding (CREB) proteins in cell proliferation in a rat model of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell. Physiol. 2006;206:411–419. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soberg K., Skalhegg B.S. The molecular basis for specificity at the level of the protein kinase a catalytic subunit. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2018;9:538. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson S., Magu B., Rasmussen C., Lancaster S., Kerksick C., Smith P., Melton C., Cowan P., Greenwood M., Earnest C., et al. Effects of coleus forskohlii supplementation on body composition and hematological profiles in mildly overweight women. J. Int. Soc. Sports Nutr. 2005;2:54–62. doi: 10.1186/1550-2783-2-2-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang H., Xu J., Lazarovici P., Quirion R., Zheng W. cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB): a possible signaling molecule link in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018;11:255. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maller J.L., Krebs E.G. Progesterone-stimulated meiotic cell division in Xenopus oocytes. Induction by regulatory subunit and inhibition by catalytic subunit of adenosine 3':5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1977;252:1712–1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lester L.B., Faux M.C., Nauert J.B., Scott J.D. Targeted protein kinase A and PP-2B regulate insulin secretion through reversible phosphorylation. Endocrinology. 2001;142:1218–1227. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.3.8023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snyder E.M., Colledge M., Crozier R.A., Chen W.S., Scott J.D., Bear M.F. Role for A kinase-anchoring proteins (AKAPS) in glutamate receptor trafficking and long term synaptic depression. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:16962–16968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409693200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang B., Dai J.X., Pan Y.B., Ma Y.B., Chu S.H. Examining the biomarkers and molecular mechanisms of medulloblastoma based on bioinformatics analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2019;18:433–441. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang S.H., Hu L.P., Wang X., Li J., Zhang Z.G. Neurotransmitters: emerging targets in cancer. Oncogene. 2020;39:503–515. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-1006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuller H.M., Al-Wadei H.A., Majidi M. GABA B receptor is a novel drug target for pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:767–778. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spampanato J., Gibson A., Dudek F.E. The antihelminthic moxidectin enhances tonic GABA currents in rodent hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2018;119:1693–1698. doi: 10.1152/jn.00587.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen T.C., Wadsten P., Su S., Rawlinson N., Hofman F.M., Hill C.K., Schonthal A.H. The type IV phosphodiesterase inhibitor rolipram induces expression of the cell cycle inhibitors p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1), resulting in growth inhibition, increased differentiation, and subsequent apoptosis of malignant A-172 glioma cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2002;1:268–276. doi: 10.4161/cbt.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moon E.Y., Lee G.H., Lee M.S., Kim H.M., Lee J.W. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors control A172 human glioblastoma cell death through cAMP-mediated activation of protein kinase A and Epac1/Rap1 pathways. Life Sci. 2012;90:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang H., Kong Q., Wang J., Jiang Y., Hua H. Complex roles of cAMP-PKA-CREB signaling in cancer. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2020;9:32. doi: 10.1186/s40164-020-00191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Q.R., Zhao H., Zhang X.S., Lang H., Yu K. Novel-smoothened inhibitors for therapeutic targeting of naive and drug-resistant hedgehog pathway-driven cancers. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019;40:257–267. doi: 10.1038/s41401-018-0019-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yauch R.L., Dijkgraaf G.J., Alicke B., Januario T., Ahn C.P., Holcomb T., Pujara K., Stinson J., Callahan C.A., Tang T., et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science. 2009;326:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharpe H.J., Pau G., Dijkgraaf G.J., Basset-Seguin N., Modrusan Z., Januario T., Tsui V., Durham A.B., Dlugosz A.A., Haverty P.M., et al. Genomic analysis of smoothened inhibitor resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carpenter R.L., Ray H. Safety and tolerability of sonic hedgehog pathway inhibitors in cancer. Drug Saf. 2019;42:263–279. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0777-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mounsey E.K., Bernigaud C., McCarthy J.S. Prospects for moxidectin as a new oral treatment for human scabies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10:1371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kandala P.K., Srivastava S.K. Activation of checkpoint kinase 2 by 3,3'-diindolylmethane is required for causing G2/M cell cycle arrest in human ovarian cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;78:297–309. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.063750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors agree to make this data available upon request.