Abstract

Introduction

Among adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD), comorbid mental illness is associated with poorer health outcomes and can impede access to transplantation. We provide the first US nationally representative estimates of the prevalence of mental illness and mental health (MH) treatment receipt among adults with self-reported CKD.

Methods

Using 2015 to 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) data, we conducted an observational study of 152,069 adults (age ≥22 years) reporting CKD (n = 2544), with no reported chronic conditions (n = 117,235), or reporting hypertension (HTN) or diabetes mellitus (DM) but not CKD (HTN/DM, n = 32,290). We compared prevalence of (past-year) any mental illness, serious mental illness (SMI), MH treatment, and unmet MH care needs across the groups using logistic regression models.

Results

Approximately 26.6% of US adults reporting CKD also had mental illness, including 7.1% with SMI. When adjusting for individual characteristics, adults reporting CKD were 15.4 percentage points (PPs) and 7.3 PPs more likely than adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM to have any mental illness (P < 0.001) and 5.6 PPs (P < 0.001) and 2.2 PPs (P = 0.01) more likely to have SMI, respectively. Adults reporting CKD were also more likely to receive any MH treatment (21% vs. 12%, 18%, respectively) and to have unmet MH care needs (6% vs. 3%, 5%, respectively).

Conclusion

Mental illness is common among US adults reporting CKD. Enhanced management of MH needs could improve treatment outcomes and quality-of-life downstream.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, mental illness, mental health treatment

Graphical abstract

CKD, which affects 1 in 7 adults in the United States, is associated with poor health and quality-of-life outcomes.1 Studies suggest that individuals with CKD and comorbid mental illness fare worse, with 11% to 66% higher risk of death,2, 3, 4 up to 90% higher risk of hospitalization,4, 5, 6 more rapid progression of CKD toward kidney failure,6, 7, 8 and other poorer outcomes,4,9, 10, 11 relative to individuals with CKD without comorbid mental illness.

Among individuals with progressing CKD or kidney failure requiring kidney replacement therapy (hereafter “kidney failure”), comorbid MH conditions may also affect courses of treatment. Transplantation and home dialysis (peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis) are contraindicated for individuals with severe mental illness that impairs functioning.12, 13, 14, 15 Yet, these treatments are more cost-effective and associated with a better quality-of-life relative to conventional in-center hemodialysis.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Thus, patients with advanced CKD who receive inadequate support in managing MH conditions will often be considered unsuitable candidates for transplant or home dialysis treatment, leading to substantially increased cost of treatment and diminished flexibility and convenience for patients and their caregivers.21

Although evidence on the effectiveness of interventions to address MH comorbidities in the CKD population remains limited,22 some studies suggest that comprehensive care management programs and psychological distress screening for patients with early stage CKD could improve CKD care delivery.23,24 In addition, several clinical trials have revealed that integrated care that more holistically addresses physical health and MH comorbidities in the general population can yield better improvements in medical outcomes (e.g., improved prescribing, treatment adherence) compared with standard treatment.25,26 Calls for implementing such approaches in CKD care are increasingly common.15,27

Despite the associations between comorbid MH conditions and outcomes for individuals with CKD and the consequences these conditions have for patients’ courses of treatment, surveillance efforts are hindered by the absence of nationally representative data on the prevalence of MH conditions or MH treatment use among adults with CKD in the United States. Data including depression plus other MH conditions are particularly rare. We fill this gap by studying MH illness and treatment outcomes in a US nationally representative sample of adults with self-reported CKD using recent data from the NSDUH.

Methods

Data and Analytical Sample

We used data from the 2015 to 2019 NSDUH. NSDUH is an annual, U.S. nationally representative survey administered by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) about MH disorders, substance use disorders, and treatment.28 Approximately 70,000 noninstititutionalized adolescents and adults (age 12+) are selected by multistage-stratified sampling. Data are collected through in-person interviews with computer-assisted interviewing methods, which encourage accurate reporting around stigmatized conditions and behaviors (e.g., mental illness).29 Weighted response rates ranged from 64% to 70% across the study years.

Our sample included adults aged 22 years and older because in the U.S., younger individuals with CKD (and particularly those with advanced CKD) receive care in distinct pediatric treatment systems and, often, in different facilities than adult patients.30,31 After further excluding adults with missing data [0.18% (n = 273)], our analytical sample included n = 152,069 adults.

We used respondents’ self-reported chronic conditions to identify the following 3 patient groups for comparison in our analyses: (1) adults with no reported chronic conditions (n = 117,235); (2) adults reporting HTN and/or diabetes but not CKD (“HTN/DM,” n = 32,290); and (3) adults reporting CKD (“CKD,” n = 2544). HTN, diabetes, CKD, and other comorbid conditions were identified using the survey item: “Please read the list and type in the numbers of all of the conditions that a doctor or other health care professional has ever told you that you had.”29 The group of adults reporting CKD includes all stages of CKD and kidney failure, as NSDUH does not collect information on biomarkers, estimated glomerular filtration rate, or self-reported kidney disease stage. HTN/DM was chosen as a comparison group for the CKD group because many patients experience these conditions before progressing toward kidney failure.1

Outcomes

There were 2 dichotomous measures used to assess the prevalence of MH conditions, denoting those who had the following: (i) past-year any mental illness and/or (ii) past-year SMI. Any mental illness and SMI are indicators generated in the NSDUH from a prediction model based on the 2008 to 2012 Mental Health Surveillance Study. Through this study, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration modeled the presence of any or severe mental illness, diagnosed by structured clinical interviews in a sample of NSDUH respondents, as functions of other observed respondent characteristics.29 Previous research has found that this model is valid and that it effectively adjusts for potential selection, noncoverage, and nonresponse biases.32,33 Correspondingly, the NSDUH has used the model to generate indicators of past-year any mental illness and SMI for the respondents. Detailed information about the Mental Health Surveillance Study and the prediction model is presented in the Supplementary Methods.

To assess MH treatment and perceived unmet treatment need, we used dichotomous indicators for those reporting the following: (i) any past-year MH treatment and (ii) past-year unmet MH care needs. MH treatment reflected having any inpatient, outpatient, or prescription treatment for “problems with emotions, nerves, or MH” in the past 12 months.29 Unmet MH care needs was defined as “feeling a perceived need for MH treatment/counseling that was not received” in the past 12 months.29

Covariates

We use Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Care Utilization and the literature to identify relevant covariates.34 Predisposing measures included respondent sex, age, and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White [reference (ref.)], non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, other). Enabling characteristics included health insurance status (private [ref.], Medicaid, Medicare, Tricare/Champus/Veterans Affairs/Military Health, Uninsured, Other), family income (<100% federal poverty level [ref.], 100% to 200% federal poverty level, >200% federal poverty level), employment (employed full time or part time [ref.], unemployed, not in labor force, or other), education (less than high school [ref.], high school graduate, some college/college graduate, or higher), and family receipt of any governmental assistance, including Supplemental Security Income, food stamps, cash assistance, and noncash assistance. Need-related characteristics comprised self-rated health (excellent/very good/good [ref.], fair/poor) and indicators for chronic conditions and substance use behaviors. To measure chronic conditions, we included indicators reflecting that the respondent had ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional they have the following: a heart condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis B or C, asthma, HIV or AIDS, and cancer (each yes/no). Measures of substance use behaviors included current smoking status, current alcohol use, and lifetime use of an illicit drug.

Statistical Analysis

We first compared outcome measures and covariates among adults reporting CKD, HTN/DM, and no chronic conditions using Pearson χ2 statistics, adjusted for survey design. Next, we estimated logistic regression models comparing the likelihood of our outcome measures among adults reporting HTN/DM and adults reporting no chronic conditions, relative to adults reporting CKD (ref.). We modeled outcomes without adjustment and then adjusted regression models in a stepwise manner, having prespecified model specifications. Next, we adjusted regressions for predisposing and enabling characteristics; these models were of principal interest for our MH prevalence outcomes. Third, our regression models controlled for predisposing, enabling, and need-related characteristics; these models were of principal interest for our MH treatment and perceived unmet treatment need outcomes. All models included year fixed effects, accounting for unobserved differences across years in our outcome measures. In supplemental analyses, we also explored the proportions of adults in each group with any mental illness or SMI who reported receiving any MH treatment in the past year.

Analyses were conducted in Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX), applying “svy” procedures to adjust standard errors for sampling weights and “margins” commands to estimate marginal effects. The Emory University Institutional Review Board determined that this study was exempt approved.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Adults reporting CKD were more likely than adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM to have any mental illness (27% vs. 17% or 20%, respectively) or SMI (7% vs. 4% or 5%, respectively) (Table 1). Similarly, a higher percentage of adults reporting CKD received any MH treatment (21% vs. 12% or 18%, respectively). Despite their greater likelihood of receiving MH treatment, adults reporting CKD were still more likely than adults reporting HTN/DM to report unmet MH care needs (6% vs. 5%).

Table 1.

US national sample characteristics by adult patient group, 2015 to 2019

| Outcomes (weighted %) | NCC (n = 117,235) | HTN/DM (n = 32,290) | CKD (n = 2544) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Past-year any mental illnessa,b | 17 | 20 | 27 |

| Past-year SMIa,b | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| Past-year any MH treatmenta,c,d | 12 | 18 | 21 |

| Past-year unmet MH care needs | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Covariates (weighted %) | |||

| Predisposing characteristics | |||

| Malee | 49 | 46 | 44 |

| Age,a,b yr old | |||

| 22–29 | 22 | 3 | 4 |

| 30–49 | 45 | 21 | 17 |

| 50–64 | 23 | 36 | 27 |

| 65+ | 10 | 40 | 52 |

| Race/ethnicitya,f | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 61 | 67 | 70 |

| Hispanic | 18 | 12 | 12 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11 | 14 | 12 |

| Other | 9 | 7 | 6 |

| Enabling characteristics | |||

| Insurancea,b | |||

| Private insurance | 68 | 67 | 59 |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 12 | 12 | 18 |

| Medicare | 4 | 12 | 18 |

| Tricare, Champus, VA, Military health | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Uninsured | 13 | 5 | 4 |

| Other insurance | 2.4 | 1.3 | 0.6 |

| Family income,a,b FPL | |||

| <100% | 13 | 12 | 15 |

| 100%–200% | 19 | 21 | 25 |

| >200% | 68 | 67 | 61 |

| Received any governmental assistancea,b | 17 | 19 | 24 |

| Employment statusa,b | |||

| Employed full time or part time | 72 | 49 | 31 |

| Unemployed | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Other/not in labor force | 24 | 49 | 67 |

| Educationa,f | |||

| Less than high school | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| High school graduate | 23 | 26 | 27 |

| Some college | 29 | 31 | 33 |

| College graduate or higher | 36 | 30 | 26 |

| Need-related characteristics | |||

| Self-rated fair or poor healtha,b,g | 8 | 25 | 46 |

| Ever told had one or more other chronic conditions (excl. diabetes, high blood pressure, and CKD)b,h | 38 | 61 | |

| Smoking statusa | |||

| Never smoked | 39 | 37 | 36 |

| Current smoker | 22 | 15 | 15 |

| Former smoker | 40 | 48 | 50 |

| Alcohol usea,b | |||

| Never used | 13 | 14 | 18 |

| Current user | 60 | 48 | 36 |

| Former user | 27 | 38 | 46 |

| Ever used illicit druga,c | 53 | 47 | 42 |

CKD, adults with chronic kidney disease; excl., excluding; FPL, federal poverty level; HTN/DM, adults with hypertension and/or diabetes but not chronic kidney disease; MH, mental health; NCC, no chronic conditions; SMI, serious mental illness.

Hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and other comorbid conditions identified using survey item: “Please read the list and type in the numbers of all of the conditions that a doctor or other health care professional has ever told you that you had.” Reporting the results of tests for equivalence based on Pearson χ2 statistics corrected for survey design, excluding missing values.

For comparisons between NCC and CKD: P < 0.001.

For comparisons between HTN/DM and CKD: P < 0.001.

For comparisons between HTN/DM and CKD: P < 0.01.

Any mental treatment include any use of inpatient, outpatient, and prescription medication treatment for MH.

For comparisons between NCC and CKD: P < 0.01.

For comparisons between HTN/DM and CKD: P < 0.05.

Versus excellent/very good/good.

Comparison excludes NCC. Chronic conditions include heart condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, cirrhosis, hepatitis B or C, asthma, HIV or AIDS, and cancer.

Relative to adults with HTN/DM or no chronic conditions, adults reporting CKD were older and more likely to be non-Hispanic White. Adults reporting CKD were also more likely to have Medicaid or Medicare, less likely to be employed or have family income ≥200% federal poverty level, and less likely to have a college degree. Furthermore, adults reporting CKD reported poorer health status and lower likelihoods of using alcohol or illicit drugs.

Past-Year Any Mental Illness

Table 2 illustrates the average marginal effects—that is, the average differences in the predicted probability—of any mental illness and SMI in the past year for adults reporting CKD, no chronic conditions, or HTN/DM from unadjusted models, models adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics, and models adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need-related characteristics. Corresponding predicted probabilities (adjusted models) are presented in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Correlates of past-year any mental illness and SMI, multivariable logistic regression models, average marginal effects

| Variable | Past-year any mental illness |

Past-year SMI |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: unadjusted (n = 152,069) |

Model 2: adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics (n = 151,982) |

Model 3: adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need-related characteristics (n = 151,963) |

Model 4: unadjusted (N = 122,062) |

Model 5: adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics (n = 121,994) |

Model 6: adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need-related characteristics (n = 121,979) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | |||||||

| Variables of interest (ref. = CKD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No chronic conditions | −10.0 | −12.3 | −7.7 | <0.001 | −15.4 | −17.9 | −12.9 | <0.001 | −6.3 | −8.6 | −4.1 | <0.001 | −3.5 | −4.7 | −2.3 | <0.001 | −5.6 | −7.2 | −4.0 | <0.001 | −1.7 | −2.9 | −0.6 | 0.01 |

| HTN/DM | −7.1 | −9.3 | −4.9 | <0.001 | −7.3 | −9.7 | −4.8 | <0.001 | −2.7 | −4.9 | −0.5 | 0.02 | −2.1 | −3.3 | −0.9 | 0.001 | −2.2 | −3.8 | −0.6 | 0.01 | −0.3 | −1.4 | 0.7 | 0.53 |

| Predisposing characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | −6.0 | −6.5 | −5.5 | <0.001 | −7.3 | −7.8 | −6.7 | <0.001 | −1.7 | −2.0 | −1.4 | <0.001 | −2.1 | −2.4 | −1.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age (ref. = 22–29 yr old) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30–49 yr old | −4.9 | −5.6 | −4.2 | <0.001 | −4.4 | −5.0 | −3.7 | <0.001 | −2.0 | −2.5 | −1.4 | <0.001 | −1.7 | −2.2 | −1.2 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 50–64 yr old | −13.1 | −13.9 | −12.2 | <0.001 | −12.5 | −13.3 | −11.7 | <0.001 | −4.8 | −5.4 | −4.2 | <0.001 | −4.4 | −5.0 | −3.9 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 65+ yr old | −19.8 | −20.7 | −19.0 | <0.001 | −16.8 | −17.7 | −15.9 | <0.001 | −7.4 | −8.0 | −6.8 | <0.001 | −6.3 | −6.8 | −5.7 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity (ref. = non-Hispanic White) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | −7.6 | −8.4 | −6.8 | <0.001 | −4.8 | −5.6 | −3.9 | <0.001 | −2.6 | −3.0 | −2.2 | <0.001 | −1.5 | −1.9 | −1.1 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −8.5 | −9.2 | −7.7 | <0.001 | −6.4 | −7.2 | −5.6 | <0.001 | −3.0 | −3.3 | −2.7 | <0.001 | −2.2 | −2.5 | −1.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Other | −5.7 | −6.7 | −4.8 | <0.001 | −2.8 | −3.9 | −1.8 | <0.001 | −2.2 | −2.6 | −1.7 | 0.31 | −1.2 | −1.6 | −0.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Insurance (ref. = private) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medicaid | 5.9 | 4.8 | 7.0 | <0.001 | 3.5 | 2.6 | 4.5 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.4 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Medicare | 5.2 | 3.3 | 7.2 | <0.001 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 4.5 | 0.002 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | <0.001 | 0.8 | -0.1 | 1.7 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| Tricare, Champus, VA, Military health | 4.3 | 2.3 | 6.3 | <0.001 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 5.6 | <0.001 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 4.0 | <0.001 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 3.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Uninsured | 2.2 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 0.87 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 2.2 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.7 | <0.001 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 0.003 | ||||||||

| Other | 0.1 | −1.5 | 1.7 | <0.001 | −0.2 | −1.8 | 1.4 | 0.81 | 0.3 | −0.3 | 1.0 | <0.001 | 0.2 | −0.4 | 0.9 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| Family income (ref. = <100% FPL) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 100%–200% FPL | 0.7 | −0.4 | 1.8 | <0.001 | 0.4 | −0.7 | 1.5 | 0.47 | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.3 | 0.35 | −0.3 | −0.8 | 0.1 | 0.15 | ||||||||

| >200% FPL | −1.6 | −2.4 | −0.8 | <0.001 | −1.7 | −2.6 | −0.8 | 0.001 | −0.9 | −1.3 | −0.5 | <0.001 | −0.9 | −1.3 | −0.5 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Family received government assistance | 5.3 | 4.5 | 6.1 | <0.001 | 2.9 | 2.1 | 3.7 | <0.001 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | <0.001 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.5 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Employment status (ref. = employed full time or part time) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 5.1 | 3.6 | 6.5 | <0.001 | 4.5 | 3.1 | 5.9 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 2.4 | <0.001 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 2.1 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Other/not in labor force | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.5 | <0.001 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 3.4 | <0.001 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.2 | <0.001 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.7 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Education (ref. = less than high school) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| High school graduate | 1.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.04 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 2.3 | 0.002 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.001 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.3 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Some college | 4.5 | 3.5 | 5.4 | <0.001 | 4.6 | 3.6 | 5.5 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 2.8 | <0.001 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.7 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| College graduate or higher | 3.3 | 2.1 | 4.4 | <0.001 | 5.0 | 3.9 | 6.1 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.2 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Need-related characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Self-rated fair or poor health (vs. excellent/very good/good) | 14.1 | 13.0 | 15.3 | <0.001 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 5.4 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ever told had one or more other chronic conditions (heart condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis B or C, asthma, HIV or AIDS, cancer) | 5.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | <0.001 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 2.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Smoking status (ref. = never smoked) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 3.9 | 3.2 | 4.6 | <0.001 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.7 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Former smoker | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.05 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.3 | 0.83 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol use (ref. = never used) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current user | 0.4 | −0.6 | 1.3 | 0.42 | 0.0 | −0.3 | 0.9 | 0.28 | ||||||||||||||||

| Former user | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.9 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 0.004 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ever used illicit drug | 10.1 | 9.4 | 10.7 | <0.001 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

AME, average marginal effect; CKD, adults with chronic kidney disease; FPL, federal poverty level; HTN/DM, adults with hypertension and/or diabetes but not CKD; ref., reference; SMI, serious mental illness.

Hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and other comorbid conditions identified using survey item: “Please read the list and type in the numbers of all of the conditions that a doctor or other health care professional has ever told you that you had.” AMEs and 95% CIs presented in percentage points. All models include year fixed effects. Differences in sample size are due to missing values in covariates.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of any mental illness and SMI across U.S. adult groups, 2015 to 2019. Hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and other comorbid conditions identified using survey item: “Please read the list and type in the numbers of all of the conditions that a doctor or other health care professional has ever told you that you had.” Predicted probabilities, presented with 95% CIs, generated using the results of multivariable logistic regression models. Predisposing measures included respondent sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Enabling characteristics included health insurance status, family income, employment, education, and if the family received any governmental assistance. Need-related characteristics comprised self-rated health and indicators for chronic conditions and substance use behaviors. All models include year fixed effects. CKD, adults with chronic kidney disease; HTN/DM, adults with hypertension and/or diabetes but not chronic kidney disease; NCC, adults with no chronic condition identified; SMI, serious mental illness.

In our unadjusted model, 26.6% of adults reporting CKD had any mental illness; this was 10.0 and 7.1 PPs higher than the proportions with any mental illness among adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM, respectively (both P < 0.001; model 1). In our model of principal interest (model 2), adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics, these differences were exacerbated; adults reporting CKD were 15.4 PPs and 7.3 PPs more likely than adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM to have any mental illness, respectively (P < 0.001). When further controlling for need-related factors (model 3), these differences were reduced to 6.3 (P < 0.001) and 2.7 PPs (P = 0.02), respectively.

Past-Year SMI

Adults reporting CKD were also more likely than adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM to have SMI. The unadjusted predicted probability of having SMI among adults reporting CKD was 7.1%, 3.5 and 2.1 PPs higher than among adults reporting no chronic conditions (P < 0.001) or HTN/DM (P = 0.001), respectively (model 4). When adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics, these differences widened to 5.6 (P < 0.001) and 2.2 PPs (P = 0.01), respectively. After further controlling for need-related characteristics, the difference in the likelihood of having SMI between adults reporting CKD and adults reporting no chronic conditions remained significant (average marginal effect = 1.7 PPs, P < 0.01); the difference between adults reporting CKD and adults reporting HTN/DM was no longer significant (average marginal effect = 0.3 PPs, P = 0.53).

Past-Year MH Treatment

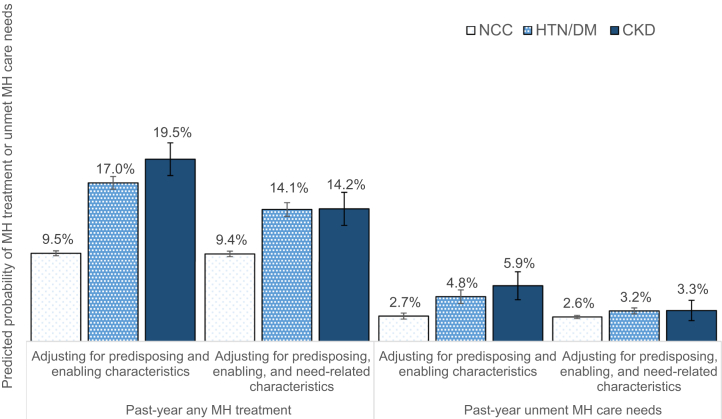

Table 3 illustrates unadjusted and adjusted differences in MH treatment and perceived unmet MH care needs in the past year among adults reporting CKD, no chronic conditions, or HTN/DM. Corresponding predicted probabilities (adjusted models) are presented in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Correlates of past-year any MH treatment and unmet MH needs, multivariable logistic regression models, average marginal effects

| Variable | Past-year any MH treatment |

Past-year unmet MH needs |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 7: unadjusted (n = 152,020) |

Model 8: adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics (n = 151,933) |

Model 9: adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need-related characteristics (n = 151,914) |

Model 10: unadjusted (n = 151,800) |

Model 11: adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics (n = 151,714) |

Model 12: adjusting for predisposing, enabling, and need-related characteristics (n = 151,695) |

|||||||||||||||||||

| AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | AME (%) | 95% CI | P value | |||||||

| Variables of interest (ref. = CKD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| No chronic conditions | −8.9 | −10.7 | −7.1 | <0.001 | −10.6 | −12.5 | −8.8 | <0.001 | −5.3 | −7.1 | −3.6 | <0.001 | -0.8 | −2.0 | 0.3 | 0.14 | −4.4 | −6.0 | −2.8 | <0.001 | −1.1 | −2.3 | 0.2 | 0.09 |

| HTN/DM | −2.9 | −4.8 | −1.0 | 0.003 | −2.6 | −4.5 | −0.6 | 0.01 | −0.1 | −1.8 | 1.7 | 0.93 | −1.0 | −2.2 | 0.1 | 0.07 | −1.5 | −3.1 | 0.1 | 0.06 | −0.1 | −1.3 | 1.1 | 0.91 |

| Predisposing characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Male | −7.2 | −7.7 | −6.8 | <0.001 | −8.2 | −8.6 | −7.7 | <0.001 | −2.8 | −3.1 | −2.5 | <0.001 | −3.2 | −3.5 | −2.9 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Age (ref. = 22–29 yr old) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30–49 yr old | 0.0 | −0.6 | 0.6 | 0.90 | 0.2 | −0.4 | 0.8 | 0.45 | −4.8 | −5.2 | −4.4 | <0.001 | −4.2 | −4.6 | −3.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 50–64 yr old | −3.1 | −4.0 | −2.3 | <0.001 | −3.0 | −3.8 | −2.2 | <0.001 | −8.2 | −8.6 | −7.7 | <0.001 | −7.4 | −7.9 | −6.9 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| 65+ yr old | −10.6 | −11.4 | −9.7 | <0.001 | −8.3 | −9.3 | −7.4 | <0.001 | −10.3 | −10.8 | −9.8 | <0.001 | −9.0 | −9.5 | −8.5 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Race/ethnicity (ref. = non-Hispanic White) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | −9.5 | −10.2 | −8.9 | <0.001 | −7.4 | −8.1 | −6.8 | <0.001 | −2.8 | −3.1 | −2.5 | <0.001 | −1.8 | −2.1 | −1.4 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | −10.7 | −11.2 | −10.1 | <0.001 | −9.0 | −9.6 | −8.5 | <0.001 | −3.0 | −3.4 | −2.6 | <0.001 | −2.2 | −2.5 | −1.8 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Other | −10.6 | −11.1 | −10.0 | <0.001 | −8.3 | −9.0 | −7.7 | <0.001 | −2.7 | −3.0 | −2.3 | <0.001 | −1.6 | −2.0 | −1.1 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Enabling characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Insurance (ref. = private) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Medicaid | 4.6 | 3.6 | 5.7 | <0.001 | 3.0 | 1.9 | 4.1 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.3 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 1.6 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Medicare | 3.4 | 1.6 | 5.1 | <0.001 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 3.7 | 0.03 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.004 | 0.6 | −0.3 | 1.6 | 0.18 | ||||||||

| Tricare, Champus, VA, Military health | 6.2 | 4.0 | 8.4 | <0.001 | 5.9 | 3.7 | 8.0 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 0.01 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 2.0 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Uninsured | −4.1 | −4.9 | −3.3 | <0.001 | −4.6 | −5.4 | −3.8 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Other | −1.0 | −2.6 | 0.5 | 0.19 | −1.0 | −2.5 | 0.5 | 0.20 | 0.1 | −0.6 | 0.8 | 0.83 | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.8 | 0.90 | ||||||||

| Family income (ref. = <100% FPL) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1100%–200% FPL | 0.0 | −0.9 | 0.9 | 1.00 | −0.2 | −1.1 | 0.6 | 0.61 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.06 | 0.4 | −0.1 | 0.9 | 0.14 | ||||||||

| >200% FPL | 0.2 | −0.5 | 1.0 | 0.50 | 0.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | 0.97 | −0.7 | −1.3 | −0.2 | 0.01 | −0.8 | −1.4 | −0.3 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Family received government assistance | 4.9 | 4.0 | 5.7 | <0.001 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 4.0 | <0.001 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 2.6 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.7 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Employment status (ref. = employed full time or part time) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unemployed | 3.3 | 2.1 | 4.5 | <0.001 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 4.3 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 2.0 | 0.003 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 1.8 | 0.10 | ||||||||

| Other/not in labor force | 3.9 | 3.1 | 4.7 | <0.001 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 4.2 | <0.001 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.001 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.01 | ||||||||

| Education (ref. = less than high school) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| High school graduate | 1.9 | 1.1 | 2.7 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.7 | <0.001 | 0.3 | −0.2 | 0.8 | 0.250 | 0.3 | −0.2 | 0.7 | 0.25 | ||||||||

| Some college | 6.0 | 5.2 | 6.8 | <0.001 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 6.2 | <0.001 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 2.5 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.3 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| College graduate or higher | 7.7 | 7.0 | 8.5 | <0.001 | 8.0 | 7.3 | 8.8 | <0.001 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.7 | <0.001 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 4.0 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Need-related characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Self-rated fair or poor health (vs. excellent/very good/good) | 7.3 | 6.3 | 8.3 | <0.001 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 4.9 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ever told had one or more other chronic conditions (heart condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic bronchitis, cirrhosis of the liver, hepatitis B or C, asthma, HIV or AIDS, cancer) | 3.4 | 2.7 | 4.2 | <0.001 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 3.2 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Smoking status (ref. = never smoked) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 1.9 | 1.3 | 2.4 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.3 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

| Former smoker | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.9 | <0.001 | 0.2 | -0.1 | 0.6 | 0.19 | ||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol use (ref. = never used) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current user | 1.7 | 0.8 | 2.6 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 0.003 | ||||||||||||||||

| Former user | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.9 | <0.001 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.07 | ||||||||||||||||

| Ever used illicit drug | 8.3 | 7.7 | 9.0 | <0.001 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.9 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||||||

AME, average marginal effect; CKD, adults with chronic kidney disease; HTN/DM, adults with hypertension and/or diabetes but not chronic kidney disease; FPL, federal poverty level; MH, mental health; ref., reference.

Hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and other comorbid conditions identified using survey item: “Please read the list and type in the numbers of all of the conditions that a doctor or other health care professional has ever told you that you had.” AMEs and 95% CIs presented in percentage points. All models include year fixed effects. Differences in sample size are due to missing values in covariates.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of MH treatment and unmet MH care needs across U.S. adult groups, 2015 to 2019. Hypertension, diabetes, CKD, and other comorbid conditions identified using survey item: “Please read the list and type in the numbers of all of the conditions that a doctor or other health care professional has ever told you that you had.” Predicted probabilities, presented with 95% CIs, generated using the results of multivariable logistic regression models. Predisposing measures included respondent sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Enabling characteristics included health insurance status, family income, employment, education, and if the family received any governmental assistance. Need-related characteristics comprised self-rated health and indicators for chronic conditions and substance use behaviors. All models include year fixed effects. CKD, adults with chronic kidney disease; HTN/DM, adults with hypertension and/or diabetes but not chronic kidney disease; MH, mental health; NCC, adults with no chronic condition identified.

The unadjusted predicted probability of adults reporting CKD receiving any MH treatment in the past year was 20.8%. Relative to adults reporting no chronic conditions, adults reporting CKD were 8.9 and 10.6 PPs more likely to receive any MH treatment in the unadjusted model (model 7) and when adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics (model 8), respectively (both P < 0.001). After further adjusting for need-related characteristics (model 9), this difference remained significant (5.3 PPs, P < 0.001).

Relative to adults reporting HTN/DM, adults reporting CKD were 2.9 (P = 0.003) and 2.6 (P = 0.01) PPs more likely to receive any MH treatment in models 7 and 8, respectively. In model 9, there was no difference in the likelihood of receiving any MH treatment between these groups (average marginal effects = 0.1 PPs, P = 0.93).

In supplemental analyses, we performed unadjusted comparisons of MH treatment outcomes among subgroups with and without any mental illness or SMI (Supplementary Table S1). Among individuals with any mental illness, 48% of adults reporting CKD had any MH treatment in the past year versus 38% of adults reporting no chronic conditions and 50% of adults reporting HTN/DM. Among individuals with SMI, 79% of adults reporting CKD had any MH treatment versus 60% of adults reporting no chronic conditions and 73% of adults reporting HTN/DM.

Past-Year Unmet MH Care Needs

The predicted probability of perceived unmet MH care needs was highest among adults reporting CKD in all models (7–9). The differences versus adults reporting no chronic conditions were statistically significant only in the model adjusting for predisposing and enabling characteristics but not need-related characteristics (5.9% vs. 2.7%, P < 0.001; Figure 2). We observed no statistically significant differences between adults reporting CKD or HTN/DM in perceived unmet MH care needs.

Discussion

Among adults with CKD or kidney failure, comorbid mental illness is associated with reduced treatment adherence and increased risk of hospitalization, readmission, and death.6,10,11,35 Moreover, severe mental illness that impairs functioning is often found as a contraindication to transplantation and home dialysis,12, 13, 14, 15 which the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) aims to help adults with CKD use more often under ongoing payment and delivery reforms.36,37 US leaders in nephrology and public health can look to national surveillance of MH need and use of MH treatment among US adults with self-reported CKD to help guide reforms in integrated kidney and MH care delivery.

Using NSDUH data, we provide the first nationally representative estimates of mental illness prevalence, MH treatment, and reported unmet need for MH treatment among US adults with self-reported CKD. Our findings add to a growing body of research evaluating barriers to MH care among patients with CKD and comorbid depressive symptoms.27,35,38, 39, 40, 41 We extend this literature by comparing individuals with self-reported CKD with 2 relevant comparator groups—adults reporting no chronic conditions and adults reporting HTN/DM—and by including a set of comprehensive MH outcome measures in our analysis, where the prior literature has typically focused on comorbid depression only.

We find that 27% of U.S. adults reporting CKD have mental illness of some type, including 7% with SMI. These prevalence estimates are within the range of prior estimates in U.S. settings, though those were derived largely from smaller and geographically concentrated studies without comparison groups.11,38, 39, 40,42,43 The significant differences in any mental illness and SMI between adults reporting CKD and adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM indicate that adults reporting CKD have meaningfully greater MH needs than these comparator populations. Our prevalence estimates are also comparable with national estimates of the prevalence of any mental illness and SMI among adults reporting CKD across other nations, where available (e.g., Korea44).

Although the proportion of adults reporting CKD receiving MH treatment was higher than among adults reporting no chronic conditions or HTN/DM, this was largely explained by higher levels of physical and behavioral health comorbidities (i.e., need-related characteristics) among adults reporting CKD. One possible explanation for this finding is that providers can often recognize when patients have greater needs and may increase their effort in managing MH needs accordingly (e.g., through comprehensive care planning for individuals with advanced CKD plus other comorbid conditions). For example, among adults with kidney failure receiving chronic dialysis treatment, regular contact with a social worker—mandated by federal regulation under Medicare—may facilitate MH treatment for those with multiple comorbidities.45 Another possible explanation for this population’s increased use of MH treatment is that those with more physical and behavioral health comorbidities may be more engaged with the health care system in general and more willing to seek MH treatment when needed. Conversely, this finding may also be explained in part by the health implications of MH treatment. For example, many drugs used to treat MH conditions, particularly those identified as SMI, may contribute to metabolic changes and weight gain and kidney dysfunction.46,47

In addition to having higher rates of MH treatment use, we find that those with self-reported CKD also have greater perceived unmet needs for MH treatment; more than half (52%) of adults with self-reported CKD who also experienced mental illness and did not receive any MH treatment. These findings point to opportunities for improving protocols for addressing comorbid mental illness in CKD care. One explanation to account for the higher rates of perceived unmet need for MH treatment among those reporting CKD is this population’s high burden of contact with the health care system. Because those with CKD have frequent health care appointments and complex medical regimens to manage (e.g., pill burden), they may have less capacity or desire to seek additional treatment for perceived MH needs. These concerns and barriers to addressing MH needs may be compounded by the risks of side effects associated with many pharmaceutical treatments for MH disorders.46,47 To address the greater perceived unmet need for care among those with CKD, provider leadership should consider adopting integrated care models (e.g., routine psychological screening, referral, and counseling services in CKD clinics) and multidisciplinary disease management approaches. Previous studies have suggested that comprehensive care management programs and psychological distress screening for patients with early stage CKD may hold promise for improving CKD care delivery.23,24 Likewise, studies have revealed that integrated, multimodal care models can be used effectively in caring for patients with diabetes, HTN, and other chronic illnesses48,49 and in the general population.25,26 Although additional evidence is needed in the context of CKD care,22 these approaches have the potential to foster the provision of whole-person care that can recognize patient concerns and burdens among adults with CKD and meet their complex, intersecting physical and MH needs and preferences.

This study has several limitations. First, this study is subject to general limitations of survey data, such as recall bias and nonresponse bias. Specifically, nonresponse bias is a concern in surveys including questions on sensitive behaviors, such as substance use history. However, the computer-assisted interviewing methods of NSDUH provide greater privacy to respondents and have been found to increase disclosure of sensitive behaviors.50 Of note, there should not be differential bias among patients with self-reported CKD and the comparison groups. Second, our measures of CKD and HTN/DM status are self-reported by respondents. Relative to adults who have CKD, adults reporting they have CKD may on average have more advanced CKD, greater health literacy, and greater access to health care services,51 including MH treatment. To avoid any potential bias stemming from misperception that our results might be representative of all US adults with CKD, our results should instead be interpreted strictly as representative of all US adults with self-reported CKD. Third, we are not able to distinguish adults reporting kidney failure from other adults reporting CKD (e.g., stage IV) in our sample, an area that merits future research. Such individuals are likely to represent a small percentage of our sample of adults reporting CKD, based on 2017 estimates (about 746,500 kidney failure cases vs. 37 million CKD cases).1,52 Finally, NSDUH does not include data on the severity of respondents’ MH needs, the intensity or type of any MH treatment received, or the temporal order of any MH treatment received versus treatment for CKD. Thus, we cannot estimate the frequency with which kidney disease may have progressed in this population as a consequence of pharmaceutical treatment of mental illness (e.g., lithium).47 Moreover, our study cannot identify which types of treatment may be most valuable for filling present gaps in MH treatment among adults reporting CKD.

This study presents the first U.S. national, population-level estimates of MH care needs and treatment among adults with self-reported CKD. High levels of mental illness and unmet needs for MH care among US adults with self-reported CKD point to important opportunities for more effectively integrating MH and CKD care and managing this population’s MH needs. Comprehensive and integrated care delivery models should be evaluated as tools for managing the heightened medical and MH needs of adults with CKD.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Data Availability Statement

The data set analyzed under this study is publicly available from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive at: https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2019-nsduh-2019-ds0001.

Footnotes

Supplementary Methods.

Table S1. Unadjusted comparison of mental health treatment among subgroups with and without any mental illness or serious mental illness.

STROBE Statement.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Methods.

Table S1. Unadjusted comparison of mental health treatment among subgroups with and without any mental illness or serious mental illness.

STROBE Statement.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2019 USRDS annual data report. Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health. Accessed May 14, 2021. https://usrds.org/media/2371/2019-executive-summary.pdf

- 2.Soucie J.M., McClellan W.M. Early death in dialysis patients: risk factors and impact on incidence and mortality rates. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:2169–2175. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7102169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli M., Wiebe N., Guthrie B., et al. Comorbidity as a driver of adverse outcomes in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88:859–866. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowling C.B., Plantinga L., Phillips L.S., et al. Association of multimorbidity with mortality and healthcare utilization in chronic kidney disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:704–711. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mapes D.L., Bragg-Gresham J.L., Bommer J., et al. Health-related quality of life in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(suppl 2):54–60. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedayati S.S., Minhajuddin A.T., Afshar M., et al. Association between major depressive episodes in patients with chronic kidney disease and initiation of dialysis, hospitalization, or death. JAMA. 2010;303:1946–1953. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kop W.J., Seliger S.L., Fink J.C., et al. Longitudinal association of depressive symptoms with rapid kidney function decline and adverse clinical renal disease outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:834–844. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03840510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai Y.C., Chiu Y.W., Hung C.C., et al. Association of symptoms of depression with progression of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:54–61. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.02.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorodetskaya I., Zenios S., Mcculloch C.E., et al. Health-related quality of life and estimates of utility in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2801–2808. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimmel P.L., Fwu C.W., Abbott K.C., et al. Psychiatric illness and mortality in hospitalized ESKD dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:1363–1371. doi: 10.2215/CJN.14191218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McPherson S., Barbosa-Leiker C., Daratha K., et al. Association of co-occurring serious mental illness with emergency hospitalization in people with chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2014;39:260–267. doi: 10.1159/000360095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chadban S.J., Ahn C., Axelrod D.A., et al. KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2020;104(suppl 1):S11–S103. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farmer C.J., Snowden S.A., Parsons V. The prevalence of psychiatric illness among patients on home haemodialysis. Psychol Med. 1979;9:509–514. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700032062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliver M.J., Garg A.X., Blake P.G., et al. Impact of contraindications, barriers to self-care and support on incident peritoneal dialysis utilization. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:2737–2744. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puttarajappa C.M., Schinstock C.A., Wu C.M., et al. KDOQI US commentary on the KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77:833–856. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Voelker R. Cost of transplant vs dialysis. JAMA. 1999;281 2277-2277. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornberger J., Hirth R.A. Financial implications of choice of dialysis type of the revised Medicare payment system: an economic analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:280–287. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gokal R., Figueras M., Ollé A., et al. Outcomes in peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis—a comparative assessment of survival and quality of life. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14(suppl 6):24–30. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.suppl_6.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogutmen B., Yildirim A., Sever M., et al. Health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation in comparison intermittent hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and normal controls. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:419–421. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tonelli M., Wiebe N., Knoll G., et al. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2093–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker R.C., Hanson C.S., Palmer S.C., et al. Patient and caregiver perspectives on home hemodialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:451–463. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chopra P., Ayers C.K., Antick J.R., et al. The effectiveness of depression treatment for adults with end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Kidney360. 2021;2:558–585. doi: 10.34067/KID.0003142020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuot D.S., Grubbs V. Chronic kidney disease care in the US safety net. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22:66–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi N.G., Sullivan J.E., DiNitto D.M., Kunik M.E. Health care utilization among adults with CKD and psychological distress. Kidney Med. 2019;1:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith S.M., Soubhi H., Fortin M., et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity: systematic review of interventions in primary care and community settings. BMJ. 2012;345:e5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith S.M., Wallace E., O’Dowd T., Fortin M. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD006560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006560.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sullivan M.K., Rankin A.J., Jani B.D., et al. Associations between multimorbidity and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e038401. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2015–2019. Accessed May 20, 2022. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2019-nsduh-2019-ds0001

- 29.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2018 National survey on drug use and health final analytic file codebook. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/2021-08/2018-FinalAnalytic-Codebook-RDC508.pdf Published 2019.

- 30.Bell L. Adolescent dialysis patient transition to adult care: a cross-sectional survey. Pediatr Nephrol. 2007;22:720–726. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0404-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.North American Pediatric Renal Trials and Collaborative Studies (NAPRTCS) 2008 Annual Report. NAPRTCS; Boston, MA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aldworth J., Colpe L.J., Gfroerer J.C., et al. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Mental Health Surveillance Study: calibration analysis. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(suppl 1):61–87. doi: 10.1002/mpr.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedden S, Gfroerer J, Barker P, et al. Comparison of NSDUH mental health data and methods with other data sources. CBHSQ Data Rev. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); February 2012.1-19. [PubMed]

- 34.Andersen R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedayati S.S., Bosworth H.B., Briley L.P., et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74:930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.US President Executive Order. Advancing American Kidney Health. US President Executive Order. http://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/262046/AdvancingAmericanKidneyHealth.pdf Published 2019.

- 37.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HHS launches President Trump’s ‘advancing American kidney health’ initiative. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Published 2019. Accessed July 27, 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2019/07/10/hhs-launches-president-trump-advancing-american-kidney-health-initiative.html#:∼:text=The%20initiative%20provides%20specific%20solutions,more%20kidneys%20available%20for%20transplant

- 38.Watnick S., Kirwin P., Mahnensmith R., Concato J. The prevalence and treatment of depression among patients starting dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:105–110. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shirazian S., Grant C.D., Aina O., et al. Depression in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: similarities and differences in diagnosis, epidemiology, and management. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:94–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedayati S.S., Finkelstein F.O. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of depression in patients with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:741–752. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cukor D., Cohen S.D., Peterson R.A., Kimmel P.L. Psychosocial aspects of chronic disease: ESRD as a paradigmatic illness. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:3042–3055. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007030345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cukor D., Coplan J., Brown C., et al. Depression and anxiety in urban hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:484–490. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00040107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palmer S., Vecchio M., Craig J.C., et al. Prevalence of depression in chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Kidney Int. 2013;84:179–191. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jhee J.H., Lee E., Cha M.-U., et al. Prevalence of depression and suicidal ideation increases proportionally with renal function decline, beginning from early stages of chronic kidney disease. Med. 2017;96:e8476. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Association of Kidney Patients. Understanding the role of a renal social worker. Updated 2016. Accessed 2022, Jan 27. https://aakp.org/understanding-the-role-of-a-renal-social-worker/

- 46.Allison D.B., Newcomer J.W., Dunn A.L., et al. Obesity among those with mental disorders: a National Institute of Mental Health meeting report. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:341–350. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Iwagami M., Mansfield K.E., Hayes J.F., et al. Severe mental illness and chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study in the United Kingdom. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:421–429. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S154841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Katon W.J., Lin E.H., Von Korff M., et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinger K., Beverly E.A., Lee Y., et al. The effect of a structured behavioral intervention on poorly controlled diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1990–1999. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): summary of methodological studies, 1971–2014. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Published 2014. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/n/mrmethodssummary2014/pdf/ [PubMed]

- 51.Plantinga L.C., Tuot D.S., Powe N.R. Awareness of chronic kidney disease among patients and providers. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:225–236. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States, 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/kidneydisease/pdf/2019_National-Chronic-Kidney-Disease-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data set analyzed under this study is publicly available from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive at: https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2019-nsduh-2019-ds0001.