Abstract

McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome is a rare and life-threatening disease characterized by the triad of (1) chronic mucous diarrhea, (2) renal function impairment with hydroelectrolyte imbalance, and (3) a giant colorectal tumor. Often, the tumor is a rectal adenoma. With the mortality being certain, if left untreated, it is important to raise awareness on the presentation, diagnosis, and management of this disease entity. Here, we presented 3 cases of McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome that were successfully managed with surgical resection at the Philippine General Hospital from August 2018 to May 2019. Resolution of their symptoms, reversal of their renal impairment, and correction of their electrolyte depletion were noted after removal of the tumor with a sphincter-saving operation.

Keywords: McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome, Colorectal neoplasms

INTRODUCTION

Extreme electrolyte depletion and acute kidney injury secondary to severe secretory diarrhea from a colorectal villous adenoma were first described in a case report entitled “Prerenal uremia due to papilloma of rectum” by Garis in 1941. This syndrome was then named eponymously by McKittrick and Wheelock in 1954. Since then a total of 257 cases have been reported worldwide according to a systematic review by Orchard et al. [1] in 2018.

McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome (MKWS) is characterized by a large volume of secretory diarrhea, dehydration, prerenal acute kidney injury, and severe electrolyte abnormalities secondary to a hypersecretory villous adenoma which is reported in about 2% to 3% of adenomas that are greater than 3 to 4 cm [2-5]. Patients typically report long-standing watery or mucinous diarrhea that is often initially managed medically. When the secretory diarrhea caused by the rectal adenoma becomes so severe as to cause multiple electrolyte imbalance and prerenal azotemia, the patient’s condition worsens in a manner described by Langeron et al. [6] as the deterioration phase, which is followed shortly by the decompensation phase. With the mortality of this condition being almost certain if left untreated, it is then important to raise awareness on the presentation, diagnosis, and management of this syndrome.

In this paper, we report 3 cases of MKWS, all of whom were operated on in our institution within 11 months. This observation supports a suggestion made by Roy and Ellis [7] in 1959 that despite the reported rarity of this condition, it “may be not so much rare as it is overlooked.” All 3 patients underwent an abdominotransanal excision with coloanal anastomosis.

This is a case series of 3 patients managed as MKWS at the Philippine General Hospital from August 2018 to May 2019. The study protocol is registered under the University of the Philippines Research Grants Administration Office with registration number RGAO-2020-0250 and signed informed consent was obtained from the study participants.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

A 47-year-old female presented with a 5-year history of watery stools and frequent hospital admissions due to multiple electrolyte imbalance from chronic diarrhea. She presented at our institution with azotemia from renal hypoperfusion and prerenal dehydration from gastrointestinal losses, and metabolic encephalopathy from hyponatremia. She also had hypokalemia (Table 1). After stabilization and resuscitation, a colonoscopy (Fig. 1A-C) revealed a circumferential fungating friable mass, causing 80% luminal obstruction located at 3 to 10 cm from anal verge (FAV).

Table 1.

Blood chemistry panel of three cases of McKittrick-Wheelock Syndrome. PGH, 2018-2019

| Variable | Reference value | Case no. |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| SCr (μmol/L) | 58–110 | 232↑ | 372↑ | 115↑ |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 3.2–7.1 | 22.9↑ | 14.6↑ | 9.0↑ |

| Na+ (mmol/L) | 137–145 | 111↓ | 121↓ | 137 |

| K+ (mmol/L) | 3.5–5.1 | 2.5↓ | 1.9↓ | 3.1↓ |

| Cl– (mmol/L) | 98–107 | 50↓ | 73↓ | 90↓ |

SCr, serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Na, sodium; K, potassium; Cl, chloride.

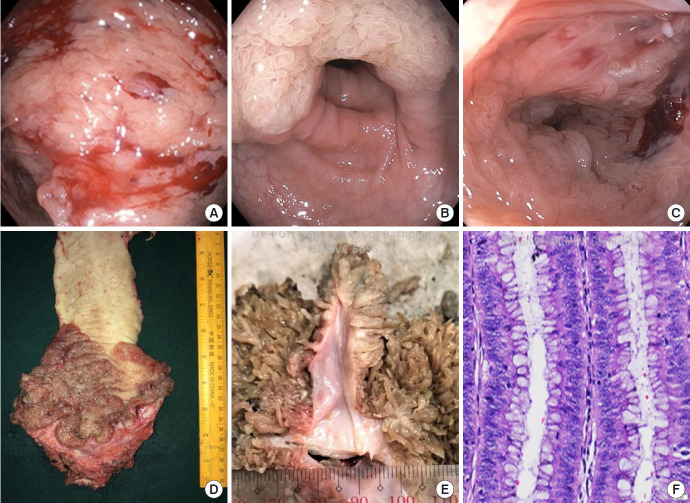

Fig. 1.

(A–C) Colonoscopic images. (A) Polypoid lesion with friable mucosa. (B) The same lesion seen with respect to the inferior rectal valve. (C) Proximal extent of the adenoma with multiple villous projections on the mucosal surface and copious mucinous secretions. (D, E) Gross specimen. (D) Rectal segment with adenomatous polyps 3 cm up to 10 cm from anal verge. (E) Cross section, macroscopic view of villous projections. (F) Microscopic sections show glands composed of tubular and villous components lined by cells with enlarged, hyperbasophilic, and stratified nuclei (H&E stain, ×100). Philippine General Hospital, 2018.

The biopsy of the lesion was tubulovillous adenoma. The patient was prepared for surgery and underwent a sphincter-preserving procedure. An abdominotransanal resection was done with coloanal anastomosis and protecting loop ileostomy. Fig. 1D, E show the gross appearance of the lesion with a confluence of polyps from 3 to 10 cm FAV.

The histopathology report revealed multiple villous projections confined to the mucosa. The mass showed glands lined by cells with enlarged, hyperbasophilic, and stratified nuclei (Fig. 1F). The glands were arranged in tubular and villous architecture, the latter comprising more than 25%. Postoperatively, her condition improved with reversal of the fluid and electrolyte imbalance.

Case 2

A 62-year-old female presented with a 1-year history of chronic watery diarrhea and a history of multiple hospital admissions for recurrent hypokalemia and hyponatremia. The patient was admitted to our institution with prerenal azotemia and multiple electrolyte imbalance (Table 1). On physical examination, there was a note of a large polypoid lesion prolapsing FAV, shown in Fig. 2A.

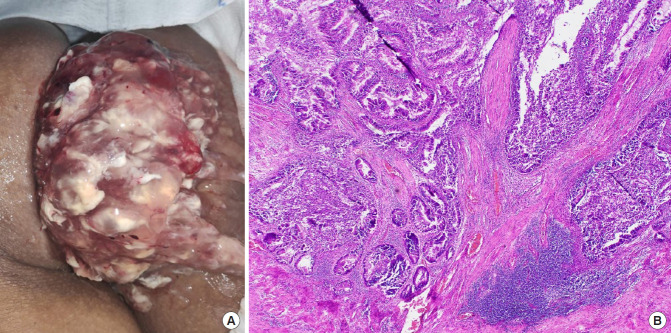

Fig. 2.

(A) Large rectal mass with copious mucin, seen prolapsing from the anal verge in a 62-year-old female patient. (B) Photomicrograph showing well-formed tubules and glands, infiltrating into fibers of the muscularis propria (H&E stain, ×100). Philippine General Hospital, 2019.

Biopsy of the tumor revealed a villous adenoma. The patient then underwent abdominotransanal resection with coloanal anastomosis, and protecting loop ileostomy. Postoperatively, there was resolution of the prerenal azotemia and multiple electrolyte imbalance. The final histopathologic report revealed a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with invasion up to the muscularis propria (Fig. 2B) and no lymphovascular invasion and nodal metastasis (stage I, pathologic stage [p] T2N0M0). The patient did not receive any adjuvant treatment.

Case 3

A 65-year-old male presented with a 2-year history of diarrhea and a prolapsing rectal mass with copious mucoid discharge. The patient was admitted for elevated creatinine, hypokalemia, and hypochloremia (Table 1). On physical examination, a polypoid mass was seen prolapsing from the anal verge, seen in Fig. 3A. Biopsy of the rectal mass showed a tubulovillous adenoma.

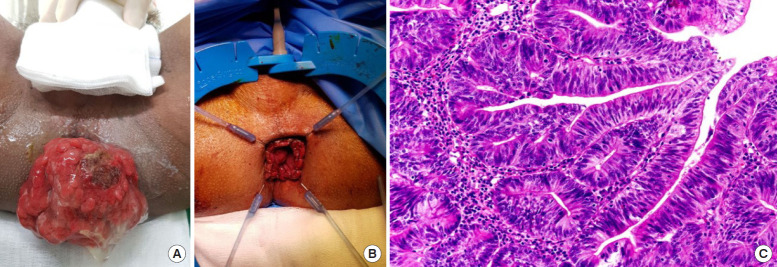

Fig. 3.

(A) A rectal mass prolapsing from the anal verge with mucinous discharge. (B) Postoperative site after abdominotransanal resection and coloanal anastomosis. (C) Glandular proliferation showing high grade nuclei extending no deeper than the muscularis mucosa (H&E stain, ×100). Philippine General Hospital, 2019.

The patient underwent abdominotransanal resection with coloanal anastomosis (Fig. 3B), and protecting loop ileostomy. Postoperatively, the patient’s symptoms resolved and he was discharged with no morbidity. The final histopathologic report showed an intramucosal carcinoma arising from a tubulovillous adenoma (Fig. 3C) with no lymphovascular invasion (stage 0, pTisN0M0). No adjuvant treatment was given.

DISCUSSION

MKWS is a rare and life-threatening disease characterized by the triad of chronic mucous diarrhea; renal function impairment with hydroelectrolyte imbalance; and a giant left-sided tumor, often a large rectal adenoma [8]. However, as pointed out in a recent systematic review by Orchard et al. [1] that identified 257 reported cases, the syndrome may have likely gone unrecognized, mainly due to the fact that it presents as a digestive disease with an overwhelming impact on renal function.

All 3 patients presented with the classic symptomatology for MKWS. The final biopsy ranged from a benign tumor, to carcinoma-in-situ, and invasive adenocarcinoma (Table 2). A literature review of the reported cases of malignant MKWS was done through a PubMed search. A total of 10 reported cases were reviewed [5, 9-17], the findings of which are summarized in Table 3. Most malignant cases were seen in patients aged > 55 years (mean age, 61 years) and have a tumor size of > 4.5 cm (mean size, 10.6 cm). The male to female ratio is 1:1.4.

Table 2.

Summary of clinicopathologic characteristics of 3 cases of McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome, Philippine General Hospital (2018–2019)

| Case no. | Age (yr) | Sex | Presenting symptom | Duration of symptoms (yr) | Initial biopsy | Tumor height FAV (cm) | Surgery done | Tumor size (cm) | Final biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 47 | Female | Diarrhea, profound hydroelectrolyte imbalance | 5 | Tubulovillous adenoma | 3 | Abdominotransanal resection with coloanal anastomosis and defunctioning ileostomy | 4.4 | Tubulovillous adenoma |

| 2 | 62 | Female | Diarrhea, acute kidney injury | 1 | Villous adenoma | 2 | 5.3 | Adenocarcinoma, well-differentiated (T2N0M0) | |

| 3 | 65 | Male | Diarrhea, multiple electrolyte imbalance | 2 | Tubulovillous adenoma | 2 | 8.0 | Intramucosal carcinoma arising froma tubulovillous adenoma (TisN0M0) |

FAV, from anal verge.

Table 3.

Reported cases of malignant McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome

| Study | Year | Age (yr) | Sex | Tumor size (cm) | Final histopathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van der pool et al. [9] | 2018 | 67 | Male | 6.0 | Adenocarcinoma, well-differentiated |

| López-Fernández et al. [10] | 2017 | 72 | Female | 4.5 | Mucinous adenocarcinoma, moderately differentiated |

| Malik et al. [11] | 2016 | 70 | Female | Undetermined | Adenocarcinoma |

| Ohara et al. [12] | 2015 | 66 | Female | 24.5 | Adenocarcinoma |

| Raphael et al. [5] | 2015 | 58 | Female | 10.7 | Adenocarcinoma |

| Barendse et al. [13] | 2012 | 66 | Male | Undetermined | Adenocarcinoma |

| Lee et al. [14] | 2012 | 30 | Female | Undetermined | Adenocarcinoma |

| Tuţă et al. [15] | 2011 | 55 | Male | 12 | Adenocarcinoma, well-differentiated |

| Watari et al. [16] | 2011 | 74 | Male | 14.5 | Adenocarcinoma, well-differentiated |

| Lepur et al. [17] | 2006 | 57 | Male | Undetermined | Adenocarcinoma |

MKWS starts with the presence of a large secretory adenoma that clinically presents as long-standing diarrhea which in turn results in electrolyte depletion and finally to the complication of acute renal failure as the electrolyte depletion overwhelms the body’s compensatory mechanisms. Secretory villous adenomas exhibit exaggerated mucous production and are different from nonsecretory villous adenomas on ultrastructural examination; secretory villous adenomas are hypersecretory with atypical goblet cells that produce a mucin of abnormal composition [16].

Several mechanisms of fluid and electrolyte loss in MKWS have been hypothesized. Jacob et al. [18] found that in a patient with a secretory villous adenoma, there was increased adenylate cyclase activity compared to patients with nonsecretory tumors, causing an increase in cyclic adenosine monophosphate blocking the absorption of sodium and chloride by the microvilli and promotes the secretion of chloride and water by the crypt cells. Steven et al. [19] discovered that immunoreactive prostaglandin E2 (which has been suggested as the secretagogue responsible for salt wasting) level were 3-folds higher in the patients with a secretory villous adenoma compared with infectious diarrhea. As the tumor size increases the enteral losses overwhelm compensatory mechanisms.

The cornerstone of treatment of this disease is the removal of the tumor [8], either by endoscopy or surgery, after adequate correction of renal function and hydroelectrolyte imbalance. In the review by Orchard et al. [1], 14 patients underwent endoscopic resection with 4 of these patients eventually requiring additional resectional surgery or additional endoscopic procedures to achieve complete resection. We find that the size of the tumor in the MKWS patients we handled may make an endoscopic approach technically difficult. Furthermore, this may only facilitate tumor seeding in patients with undetected malignancy. Additionally, endoscopic resection has shown poor results and high recurrence rates [2, 16].

The majority of reported MKWS cases (64.8%) underwent resectional surgery (i.e., anterior resection, abdominoperineal resection, Hartmann procedure, or sigmoid colectomy); these all resulted in full resolution of symptoms and electrolyte abnormalities and are likely to still be the approach of choice [1]. A sphincter-preserving oncologic resection for ultralow tumors may be the best recommendation for MKWS patients with the age of > 55 years and with the tumor size of > 4.5 cm, due to their high malignant potential.

In conclusion, MKWS or electrolyte depletion syndrome is a clinically significant condition that presents with nonspecific long-standing symptoms and is often initially managed medically. Because renal function and electrolyte imbalance resolve only with surgical resection of the tumor, increased awareness of this disease entity is crucial. Here we presented 3 cases managed at our institution and outline common characteristics of malignant MKWS.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Orchard MR, Hooper J, Wright JA, McCarthy K. A systematic review of McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018;100:1–7. doi: 10.1308/rcsann.2018.0184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popescu A, Orban-Schiopu AM, Becheanu G, Diculescu M. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome: a rare cause of acute renal failure. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pheils MT. Villous tumors of the rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:406–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02586910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miles LF, Wakeman CJ, Farmer KC. Giant villous adenoma presenting as McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome and pseudo-obstruction. Med J Aust. 2010;192:225–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raphael MJ, McDonald CM, Detsky AS. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome. CMAJ. 2015;187:676–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langeron P, Prévost AG, Boudailliez C. Rectosigmoid villous tumors with hydroelectrolytic disorders. J Sci Med Lille. 1969;87:5–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roy AD, Ellis H. Potassium-secreting tumours of the large intestine. Lancet. 1959;1:759–60. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(59)91830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mois EI, Graur F, Sechel R, Al-Hajjar N. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome: a rare case report of acute renal failure. Clujul Med. 2016;89:301–3. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Pool AE, de Graaf EJ, Vermaas M, Barendse RM, Doornebosch PG. McKittrick Wheelock syndrome treated by transanal minimally invasive surgery: a single-center experience and review of the literature. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28:204–8. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.López-Fernández J, Fernández-San Millán D, Navarro-Sánchez A, Hernández Hernández JR. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome: a rare cause of metabolic coma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:349–51. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malik S, Mallick B, Makkar K, Kumar V, Sharma V, Rana SS. Malignant McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome as a cause of acute kidney injury and hypokalemia: report of a case and review of literature. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2016;5:218–21. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2016.01011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohara Y, Toyonaga T, Watanabe D, Hoshi N, Adachi S, Yoshizaki T, et al. Electrolyte depletion syndrome (McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome) successfully treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:280–4. doi: 10.1007/s12328-015-0597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barendse RM, van den Broek FJ, van Schooten J, Bemelman WA, Fockens P, de Graaf EJ, et al. Endoscopic mucosal resection vs transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of large rectal adenomas. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e191–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YS, Lin HJ, Chen KT. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome: a rare cause of life-threatening electrolyte disturbances and volume depletion. J Emerg Med. 2012;43:e171–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuţă LA, Boşoteanu M, Deacu M, Dumitru E. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome: a rare etiology of acute renal failure associated to well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (G1) arising within a villous adenoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2011;52(3 Supp):1153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watari J, Sakurai J, Morita T, Yamasaki T, Okugawa T, Toyoshima F, et al. A case of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome complicated by McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome associated with advanced villous adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:624–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lepur D, Klinar I, Mise B, Himbele J, Vranjican Z, Barsić B. McKittrick-Wheelock syndrome: a rare cause of diarrhoea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:557–9. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200605000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacob H, Schlondorff D, St Onge G, Bernstein LH. Villous adenoma depletion syndrome: evidence for a cyclic nucleotide-mediated diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci. 1985;30:637–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01308412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steven K, Lange P, Bukhave K, Rask-Madsen J. Prostaglandin E2-mediated secretory diarrhea in villous adenoma of rectum: effect of treatment with indomethacin. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1562–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]