Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) mediate intercellular biomolecule exchanges in the body, making them promising delivery vehicles for therapeutic cargo. Genetic engineering by the CRISPR system is an interesting therapeutic avenue for genetic diseases such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). We developed a simple method for loading EVs with CRISPR ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) consisting of SpCas9 proteins and guide RNAs (gRNAs). EVs were first purified from human or mouse serum using ultrafiltration and size-exclusion chromatography. Using protein transfectant to load RNPs into serum EVs, we showed that EVs are good carriers of RNPs in vitro and restored the expression of the tdTomato fluorescent protein in muscle fibers of Ai9 mice. EVs carrying RNPs targeting introns 22 and 24 of the DMD gene were also injected into muscles of mdx mice having a non-sense mutation in exon 23. Up to 19% of the cDNA extracted from treated mdx mice had the intended deletion of exons 23 and 24, allowing dystrophin expression in muscle fibers. RNPs alone, without EVs, were inefficient in generating detectable deletions in mouse muscles. This method opens new opportunities for rapid and safe delivery of CRISPR components to treat DMD.

Keywords: Duchenne muscular dystrophy, extracellular vesicles, gene therapy, CRISPR-Cas9, ribonucleoprotein, MDX, gene editing, dystrophin

Graphical abstract

Delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) could be efficiently performed by extracellular vesicles (EVs) purified from sera using protein transfectant as an uploading reagent. Serum EVs loaded with RNP restored dystrophin expression in 19% of muscle fibers of mdx mice that had a non-sense mutation in the dmd gene.

Introduction

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic disease that is caused by various mutations in the DMD gene that impair dystrophin protein expression.1 About 70% of patients have a deletion of one or several exons, leading to a reading frameshift. The other 30% have a non-sense point mutation. Various therapeutic approaches are currently being investigated for this disease.2

Currently, only exon skipping has been approved for commercialization.3 This technique uses antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting the splice acceptor or splice donor site to remove the exon that precedes or follows the patient deletion from the final mRNA. This treatment restores the expression of the dystrophin protein but not necessarily its full activity. In fact, the central part of the dystrophin protein is made of 24 spectrin-like repeats (SLRs) whose beginnings and ends do not match with exon spans. Thus, depending on the exons that are deleted, the SLR structure is more or less normal, and this may lead to a phenotype of more or less severe Becker muscular dystrophy in patients.

Another approach under investigation is the administration of adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) coding for a micro-dystrophin.4, 5, 6, 7 Various micro-dystrophin genes have been produced following years of research and have shown encouraging results in mice and dogs. However, the unexpected death of a young patient with DMD during a clinical trial with micro-dystrophin treatment has caused a pause in the development of this clinical trial.8

Gene editing via CRISPR-Cas9 technology has shown promising results to correct or bypass mutations in DMD.9 Dystrophin expression in DMD mouse tibialis anterior (TA) muscle has been rescued by a single cut of CRISPR-Cas9 in DMD gene to trigger exon skipping10,11 and through a double cut to delete mutations and create hybrid exons.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Nucleotide substitution in DMD gene using CRISPR base editing was also successful in restoring dystrophin expression in a DMD model.18 Delivery approaches for most of the in vivo CRISPR editing involve AAVs. However, AAVs have been shown to cause many adverse effects, such as hepatotoxicity and neurological and hematological effects in humans during clinical trials.19 Furthermore, existing antibodies from previous exposure to naturally occurring AAVs20 as well as the exorbitant cost of this treatment21 can prevent patients from receiving AAV-based therapies. Recently, extracellular vesicle (EV)-based systems have been developed to deliver CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo. EVs are generated by all types of cells, can cross biological barriers, and can avoid the mononuclear phagocytic system; these characteristics qualify them as promising vehicles for drug delivery.22 CRISPR ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes have been successfully packaged in EVs derived from HEK293T after transfection of a genetically modified Cas9 gene fused to protein domain with high affinity for EV cargo.23, 24, 25, 26 Ex vivo packaging of RNPs into already purified HEK293T-derived EVs was also successful using sonication treatment.27,28 One of the great advantages of using EVs to deliver the active agents of the CRISPR system is that they allow the delivery of a Cas9 protein rather than a Cas9 gene, which avoids its sustained expression, thus reducing the chance of an immune response and of the production of off-target mutations.27 However, the use of cancer-cell-derived EVs raises safety concerns for human therapy as they carry potential oncogenic cargos that could be co-delivered with the RNPs. The present article demonstrates that instead of using AAVs or HEK293T derived EVs, it is possible to use EVs purified from serum to deliver the SpCas9 protein and 2 guide RNAs (gRNAs) to delete problematic exons. Serum EVs have shown great potential for regenerative treatment and, more specifically, in dystrophic mice to restore membrane integrity and muscle function.29 Compared with other methods, serum EVs offer a safe and cost-effective efficient platform for CRISPR delivery.

Results

Purification of EVs from serum

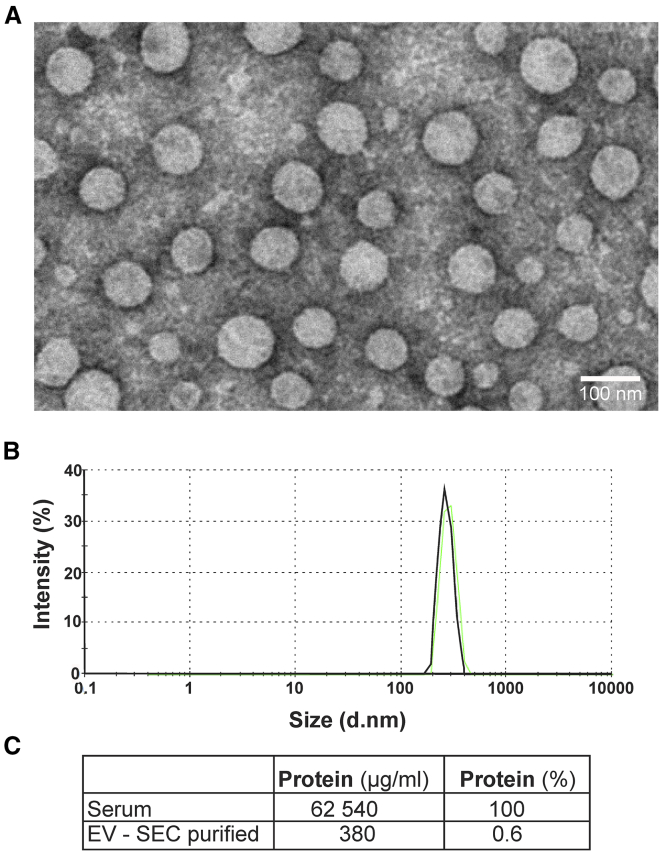

Human serum is a natural source of EVs estimated up to 1015 vesicles per liter of serum.30 The serum protein level is, however, extremely high, as much as 60–80 g/L. Therefore, in order to achieve efficient Cas9/gRNA RNP transfection, EVs should be highly purified from the serum proteins without affecting the integrity of their surface proteins. Isolation of EVs by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) has been shown to adequately maintain EV characteristics, including vesicular structure and content, while achieving a good purification and a good yield.31 For EV isolation, plasma was first clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Lipid particles were then floating at the surface, and serum was collected at the bottom of the tube to avoid the lipoprotein layer. EVs were then purified by sequential ultrafiltrations to reduce serum protein concentration followed by SEC. EVs were then concentrated again by ultrafiltration and filtered through 0.65 μm pore. Protein-concentration analysis revealed that this purification protocol was efficient to remove as much as 99.4% of protein content of the serum. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis and electron micrograph of human purified EVs (Figure 1) confirmed the uniformity and integrity of the vesicles. As observed by DLS analysis, 99.9% of the particles were in the range of expected EV size (<1 μm).

Figure 1.

Characterization of EVs purified from human serum

(A) Electron microscopy micrographs of human serum EVs after the ultrafiltration and SEC purification protocol. EVs were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and stained with 1% uranyl acetate. Magnitude, 23,000×. Scale bar: 100 nm. (B) DLS analysis of SEC purified EVs. (C) Quantification of total protein content in serum samples pre- and post-SEC purification.

Characterization of serum EVs carrying Cas9/RNP by hs-FCM

Purified EVs were further analyzed by high-sensitivity flow cytometry (hs-FCM) according to Marcoux et al.32 CellTrace (CT) carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) has been proven to be a suitable method for staining EVs for FCM.33,34 CT diffuses inside EVs where it is cleaved by internal esterases to yield a fluorescent compound. We compared 3 different preparations of CT, CFSE (green), violet, and far red at the same concentration (50 μM) to label EVs purified from serum (Figure S1). Excess of CT was subsequently removed by ultrafiltration. We observed similar staining efficiency for our EV preparations, i.e., around 70% of fluorescent-labeled events detected FCM. We therefore choose CT violet for the subsequent experiments.

To quantify EVs present in our preparation, purified EVs were labeled with CT violet, mixed with determined concentration of 2 μm fluorescent Cy5 beads, and analyzed on hs-FCM. We were able to determine using bead count that SEC purification recovered 1 × 109 to 1 × 1010 EVs per mL of serum used for purification.

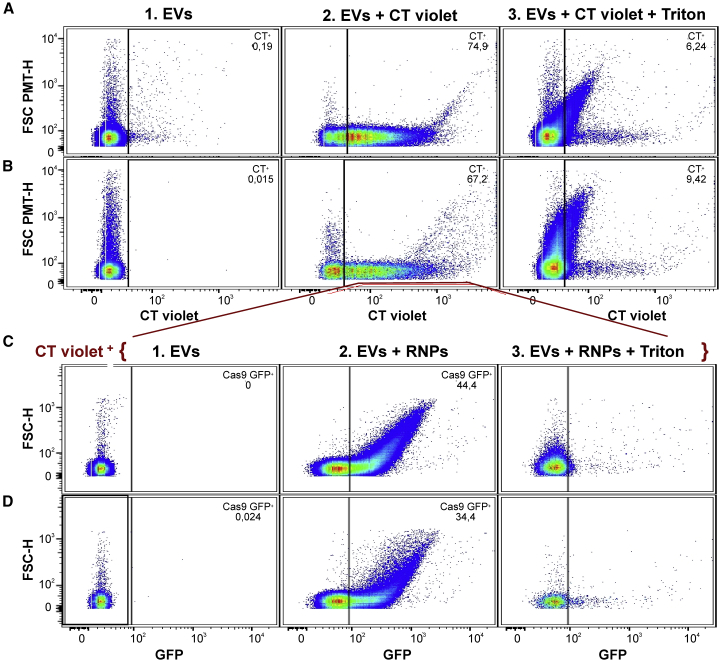

The protein transfectant Lipofectamine CRISPRMAX (CM) was tested for packaging RNP complex into purified EVs. The SpCas9-GFP protein was first assembled with a crRNA and a tracr-RNA and incubated with human serum-purified EVs in the presence of CM. For hs-FCM analysis, EVs were stained before (or not) with CT violet. After transfection, EV extracts were washed and concentrated by ultrafiltration. These EVs loaded with RNPs were then analyzed by hs-FCM. Close to 75% of the events detected were stained with CT violet (Figure 2A). In the absence of EVs, CT+ events were not detected in samples with only SpCas9-GFP RNP and CM (Table 1). Moreover, treatment with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature reduced drastically CT-labeled particles, indicating that most CT events were enclosed in membrane vesicles such as EVs. We then analyzed the CT+ fractions for its content in SpCas9-GFP fluorescent protein. Up to 44% of our CT+ fraction was also GFP+ (Figure 2C). This fraction was also sensitive to detergent since almost no fluorescent events were detected after Triton treatment (Figure 2C; Table 1).

Figure 2.

Characterization of purified serum vesicles purified by hs-FCM

(A and B) Representative plots of CT violet+-labeled particles of 100–1,000 nm in size from serum EVs purified by SEC (A) or by ultracentrifugation (UC) (B). (1) EVs alone, (2) EVs CT violet labeled, and (3) EVs CT violet labeled but subsequently treated with Triton X-100. (C and D) Ratio of CT + events that were GFP+ after transfection of SpCas9-GFP RNPs in SEC-purified EVs (C) or UC purified EVs (D). (1) EVs CT +, (2) EVs CT + transfected with RNPs, and (3) EVs CT + transfected with RNPs but subsequently treated with Triton X-100.

Table 1.

Flow-cytometry analysis of purified EVs from serum

| Purification | CT+ (/mL of serum) | CT+ CD9+ (%)a | CT+ GFP+ (%)a | CT+ GFP+ CD9+ (%)a | CT+ GFP+ with triton (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEC | 8.5 × 109 | 20 | 44 | 10.2 | 0.62 |

| Ultracentrifugation | 2.5 × 109 | 19 | 34 | 6.7 | 0.58 |

| Cas9-GFP + CM (no EVs) | (<0.01%) | ndc | ndc | ndc | ndc |

In percentage of CT+ events.

In percentage of CT+GFP+ events.

Not detected.

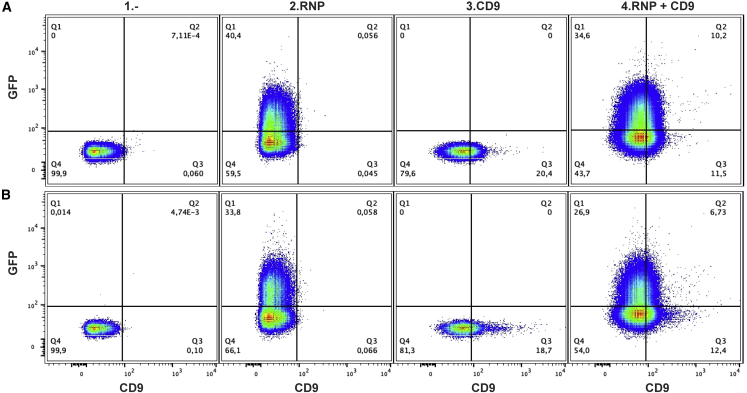

CD9 is a tetraspanin protein found on the surface of many, but not all, EVs.35,36 CD9 is considered a specific EV marker as it has not been detected on non-EV particles present in the serum like lipoproteins.37 We further characterized our CT+GFP+ fraction with anti-CD9 antibodies. We found that 10% of our CT+ events were dual labeled with allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD9 antibodies and GFP (Figure 3A). As control, an APC immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype with no known target site did not show affinity for CT+ particles (Figure S2). The ratios of CD9+ vesicles detected in our purified serum samples, 20.4% for EVsec and 18.7% for EVuc, are similar to data previously reported.33

Figure 3.

Characterization of serum vesicles with anti-CD9 antibodies

Representative plots of particles CT+ analyzed for GFP and APC anti-CD9 fluorescent signal from SEC- (A) and UC- (B) purified serum: (1) EVs/CT+; (2) EVs/CT+ transfected with Cas9-GFP RNP; (3) EVs/CT+ labeled with APC anti-human CD9; and (4) EVs/CT+ transfected with RNP and labeled with APC anti-CD9.

Serum contains lipoprotein particles that harbor similar sizes as EVs. Although SEC purification gives a better yield and integrity of EVs, the purified fraction could contain other large particles as lipoprotein complexes.38 Alternatively, EV preparations obtained by ultracentrifugation purification are free of these lipid particles but could have more contaminating proteins.38 We therefore decided to analyze by hs-FCM preparations of EVs purified by ultracentrifugation (UC) and compared them with those obtained by SEC purification. As described before,38,39 UC purification was less efficient than SEC to recover EVs, as we obtained 2.5 × 109 EVs/mL for UC compare with 8.5 × 109 for SEC purification with the same source of serum, so only 30% of the purified SEC preparation (Table 1).38 Interestingly, about the same ratio of CT-labeled events were observed for UC- and SEC-purified samples (Figures 2A and 2B); that is about 67%. Removing lipoprotein particles by UC purification did not increase the ratio of CT-labeled vesicles. EVs are highly heterogeneous in molecular composition;40 it is therefore possible that not all EVs contain enzymes able to hydrolyze CT molecules. The uptake of SpCas9-GFP by UC fraction was slightly reduced when compared with the results obtained with SEC particles (34.4% versus 44.4%). The presence of contaminating proteins within the sample could reduce the efficiency of RNP transfection into EVs (Tables 1 and S2; Figure 2D). CD9 labeling gave similar results as those observed with SEC-purified samples (Figure 3B). Since UC-purified particles behaved similarly to the SEC-purified fraction, we concluded that most of the particles carrying SpCas9-GFP RNPs were EVs. This was also confirmed by the analysis of the SEC fraction, which showed that 96% of GFP+ events of 100–1000 nm were also CT+ (Figure S3). Without EVs, no GFP+ events were stained by CT (Figure S3). These results mean that while not all EVs (CT+) contain RNPs (GFP+), almost all RNPs (GFP+) in our sample were carried by EVs (CT+). UC samples showed a lower yield than SEC fractions for the incorporation of RNP in EVs (39% versus 96%), suggesting that RNPs were in excess for this preparation. Factors such as particle concentration and integrity and purity of UC samples may impact transfection efficiency. All these results obtained by hs-FCM analysis suggest that EVs are the main carriers of SpCas9 RNPs and that SEC purification is more suitable than UC to provide qualified extract for RNP transfection.

The size of carrier EVs were also investigated by hs-FCM (Figure S4). FSC-PMT gives relative values that correlate with particle sizes. By comparing graphs obtained from non-transfected EVs with SpCas9-GFP-loaded particles, we did not observe any changes in particle size in CT-labeled EVs.

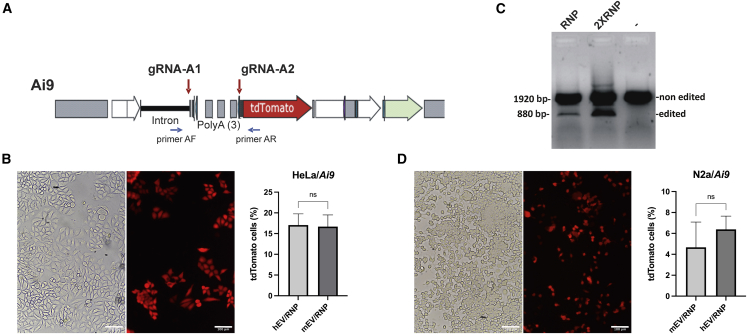

Serum EVs for delivery of Cas9/RNP targeting the Ai9 gene in vitro

The Ai9 transgene contains a tdTomato red fluorescent protein gene that is only expressed upon deletion of three poly(A) sequences located before the translation initiation sequence41 (Figure 4A). Different RNA guides targeting the Ai9 sequence before and after the three poly(A) were assembled with SpCas9 protein and transfected with CM in HeLa cells containing the Ai9 transgene. The tdTomato expression restoration induced by the poly(A) removal was analyzed by FCM. The best gRNA pair (gRNA-A1 and gRNA-A2) led to the expression of tdTomato in 19.5% of the cells. The transfection of the RNPs with these two guides was subsequently tested using purified EVs. These EVs loaded with RNPs were added to HeLa/Ai9 cells for 3 days in order to trigger tdTomato expression by SpCas9 cleavage and removal of the 3 poly(A) (Figure 4B). 17% ± 2.5% of cells were expressing tdTomato after EV incubation. HeLa/Ai9 cells incubated with EVs/RNPs were harvested, and DNA extracted. PCR analysis using primers on each side of the poly(A) sequences in the 5′ end revealed a smaller band corresponding to the deletion of those poly(A) (Figures 4B and S5A). The intensity of this small band varied with the amount of RNP cargo in EVs (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Human EV/RNP targeting the Ai9 gene in HeLa cells

(A) Scheme of the Ai9 construct. TdTomato gene is expressed only when the 3 poly(A) sequences are deleted by SpCas9 with 2 gRNAs targeting before and after the poly(A) sequences. (B) HeLa/Ai9 cells expressing fluorescent tdTomato protein after treatment with hEV/RNP (SpCas9/gRNA-A1 and SpCas9/gRNA-A2). (C) PCR using primers AF and AR on DNA extracted from HeLa/Ai9 cells incubated with 20 μL of EVs loaded with 10 (1) or 20 μL (2) of RNP-A1 and RNP-A2 or no RNP (3). (D) N2A/Ai9 cells incubated with RNP-A1 and RNP-A2 loaded in EVs purified from mouse serum. Scale bar: 100 μm. No significant difference between mEV and hEV in Ai9 cells (B and D) Graphs show mean ± SD. The differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

We also purified EVs from mouse serum and incubated them with RNPs (SpCas9 and two gRNAs [gRNA-A1 and gRNA-A2]) in presence of CM. After ultrafiltration, these EVs were added to HeLa/Ai9 as well as to mouse neuroblasts (line N2a-A18) containing the Ai9 transgene. As seen in Figure 4B, mouse EV delivery of RNP complexes was also efficient in human cells, with 16.7% ± 2.6% of red fluorescent cells detected by FCM (Figure S5B). Transfer of Cas9 RNP by mouse serum in N2a was less efficient since only 4.6% ± 2.0% of cells were positive (Figures 4D and S6A). EVs purified from human serum were also tested for their capacity to transfer RNPs in mouse cells. EVs with RNPs were as efficient as mouse EVs/RNPs to generate tdTomato expression in N2a/Ai9 cells since they generated 6.4% ± 1.2% of red positive cells (Figures 4D and S6B). There was no significant difference between EVs from human or mouse to deliver RNPs in vitro to different cells.

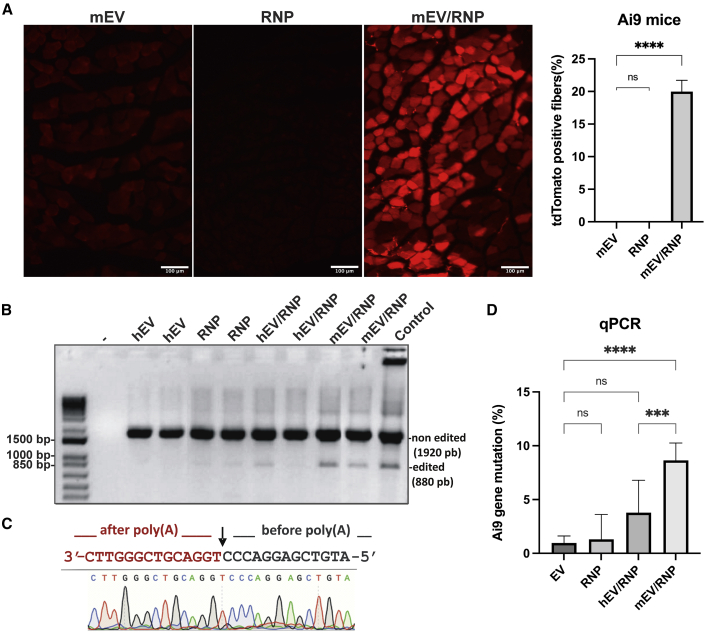

Serum EVs for delivery of RNPs to Ai9 mouse muscles

Preparations of EVs/RNP were first tested in mice by intravenous (i.v.) and intramuscular injection for side effect. No obvious adverse effects like inflammation at the site of injection, pain, or misbehavior were detected during the 7 days following injection, as treated mice behaved similarly to the control mice. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of muscle section (Figure S8) did not show any damage associated with EV treatment. EVs purified from mouse (mEV) and human (hEV) serum were loaded with RNPs (i.e., SpCas9 and gRNA-A1 and gRNA-A2), and non-incorporated products were removed by ultrafiltration. EVs from 200 μL of serum (∼109 vesicles) were injected into the TA muscle of an Ai9 transgenic mice. As a control, mEV, hEV, or RNP alone, incubated with transfectant, were also injected in mouse TA muscles as controls. After 8 days, the mice were sacrificed, and muscles were fixed with a 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution. Muscle sections were examined under fluorescent microscopy to detect the expression of the red fluorescent protein tdTomato. As seen in Figure 5A, red fluorescent fibers were detected in mice treated with mEV/RNP or hEV/RNP (data not shown) but not with mEV, hEV, or RNP alone. We determined that 20% ± 1.7% of the fibers were expressing tdTomato in mEV/RNP-treated mice. To confirm the addition of the tdTomato gene in the TA muscles, PCR analysis was performed on DNA extracted from these muscles. A low molecular weight (MW) band corresponding to the expected size of the edited Ai9 gene was detected in mEV/RNP- and hEV/RNP-treated muscles but was not detected in muscles treated with EVs only and barely amplified in muscles treated with RNPs alone (Figure 5B). This edited band was extracted and analyzed by Sanger sequencing, and this confirmed the expected cleavage sites (Figure 5C). To determine the ratios of tdTomato-edited genes in muscles of treated mice, qPCR analysis was performed (Figure 5D). 8.7% ± 1.6% of the Ai9 gene had the poly(A) deletion after mEV/RNP injection. The efficiency of editing was decreased with EVs purified from human serum. Only 3.8% ± 3.0% of the cells were TdTomato+, which was significantly different then EVs purified from mouse for the in vivo treatment. We also tested mouse serum EVs purified by UC for their capacity to deliver RNP in TA muscles (Figure S7). We observed less tdTomato+ fibers and less Ai9 gene correction by EVuc/RNP then EVsec/RNP treatments in Ai9 mice TA with the same quantity of EVs injected. Since we detected more contaminant protein in UC samples (Table S2), we assumed that these proteins competed with Cas9 as they were uploaded in EVs.

Figure 5.

EVs as cargo for RNPs in Ai9 mouse muscles

RNPs of SpCas9/gRNA-A1 and SpCas9/gRNA-A2 loaded or not in EVs purified from hEV or mEV serum were injected in Ai9 mouse TA muscles. The mice were sacrificed 8 days later. (A) Cryostat sections of mouse TA muscles treated with mEVs, RNPs alone, or mEV/RNP were fixed in 4% PFA and visualized under fluorescent microscopy for tdTomato detection. Magnification, 100×. (B) PCR on DNA extracted from mouse muscles treated with hEV, mEV, RNPs, hEV/RNP, or mEV/RNP. (-)C57BL/6J mouse non-treated. Control: HeLa/Ai9 cells treated with mEV/RNP. (C) Sequence of the edited band of Ai9 gene from mEV/RNP-treated Ai9 mouse muscle extract. (D) qPCR on DNA extracted from Ai9-treated mice. Graphs show mean ± SD. The differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

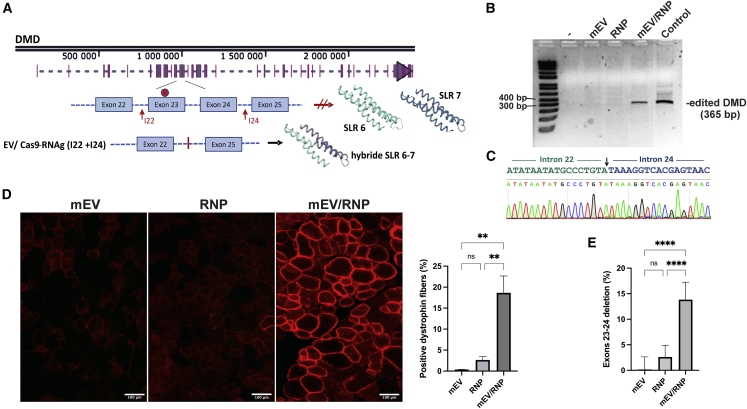

EV/RNP to restore dystrophin in mdx mouse muscles

The mdx mouse has a non-sense mutation in exon 23 of the Dmd gene, preventing the expression of dystrophin protein in muscles. RNA guides (I22 and I24) were designed to target introns 22 and 24 in order to delete exons 23 and 24. These gRNAs restore dystrophin protein expression by removing the non-sense mutation while also forming a hybrid SLR 6–7 harboring a conformational structure similar to the wild-type SLR structure (Figure 6A). The guides were first tested in vitro in mouse fibroblasts with SpCas9 protein for their activity on the Dmd gene. The expected deleted fragment was detected by PCR amplification of DNA extracted from cells treated with RNPs (data not shown). The activity of these RNPs loaded in mouse EVs was also tested in vitro on mdx mouse fibroblasts by PCR analysis (Figure 6B, lane 4). A PCR band of expected size for Dmd with the two exon deletions was detected.

Figure 6.

EVs for delivery of RNPs in mdx mouse TA muscles

EVs purified from mouse serum were loaded or not with RNPs of SpCas9/gRNA-I22 and SpCas9/gRNA-I24 and injected in mdx mouse TA muscles. The mice were sacrificed 21 days later. (A) Scheme of Dmd gene in mdx mice showing the non-sense mutation in exon 23 and gRNAs used to generate dystrophin protein with adequate spectrin-like repeat after deletion of exons 23 and 24. (B) PCR on DNA extracted from TA mouse muscles treated with mEV, RNP (I22 and I24), and mEV/RNP (I22 and I24) (3) and fibroblasts treated with mEV/RNP (I22-I24) (control) and control PCR with water (-). (C) Sequence of the PCR DNA fragment of mEV/RNP-treated muscle DNA. (D) Muscle sections of mice treated with mEV, RNP, or mEV/RNP were immunostained with anti-dystrophin antibodies and visualized under fluorescent microscopy. Magnification 100×. Scale bar: 100 μm. (E) cDNAs made from RNA extracted from mdx mouse were analyzed by qPCR. Graphs show mean ± SD. The differences between groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

For the in vivo experiment, EVs from 200 μL of mouse serum (∼109 particles) were loaded with RNPs containing the gRNA (I22 and I24), concentrated by ultrafiltration to 15 μL, and injected in TA muscles of Rag/mdx mice. Muscles were collected 3 weeks after the treatment. PCR amplification of extracted gDNA revealed a deletion of exons 23 and 24 in mouse muscles treated with mouse EVs loaded with RNPs (Figure 6B). However, no band was detected in muscles treated with RNPs or EVs alone. The PCR band from the EV/RNP-treated mice was sequenced, and this confirmed the excision of exons 23 and 24 (Figure 6C). Cryostat sections of the muscles were immunostained with anti-dystrophin antibodies and visualized under fluorescent microscopy (Figure 6D). Dystrophin expression was clearly restored in 18.6% ± 4.0% of the fibers of TA muscles treated with mEV/RNP but not in TA muscles treated with EVs or RNPs alone.

To determine the efficiency of EV/RNP treatment to excise the non-sense mutation in gDNA of mouse muscles, a qRT-PCR on cDNA from Dmd exons 23 and 24 was performed and compared with transcript abundance of Dmd exons 20 and 21. RNA extracted from mouse muscles treated with EVs alone were used as controls. Up to 19% of cDNA transcripts extracted from mouse muscles treated with EV/RNP had a deletion of exons 23 and 24, with an average of 13.8% ± 3.4% per muscle. Muscle sections were also stained with H&E (Figure S8). We did not observe any differences between MDX naive mouse control and our treated TA sections.

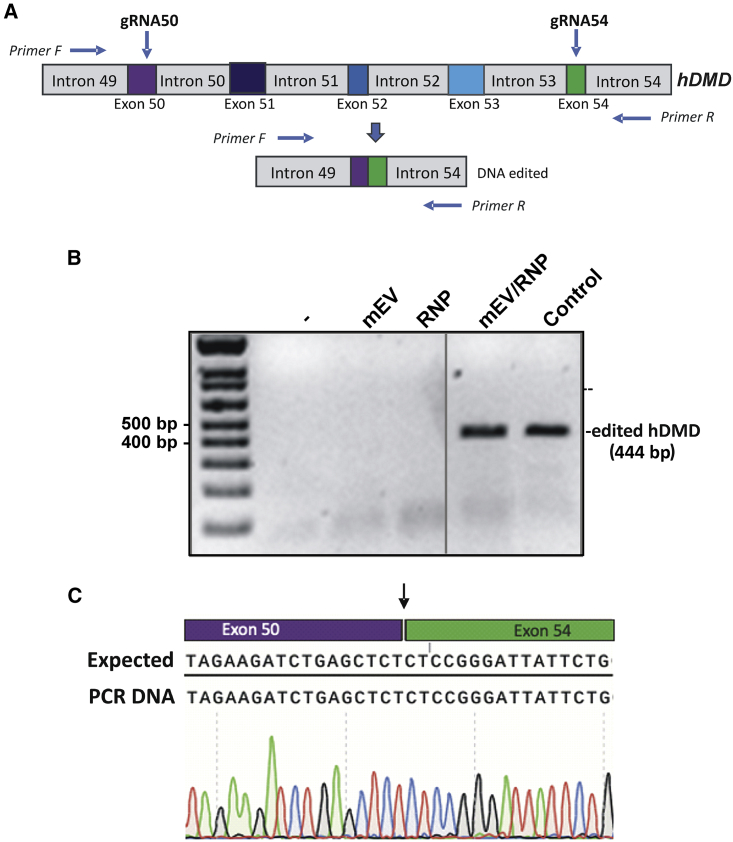

Serum EVs for delivery of RNPs in hDMD/mdx mouse muscles

The in vivo activity of RNPs delivered by EVs was further investigated in hDMD/mdx mice expressing the human DMD gene.42 gRNAs targeting exons 50 and 54 (gRNA50 and gRNA54) of the human DMD gene previously described by our research group12 (Figure 7A) were assembled with the SpCas9 protein, and the RNPs were packaged in EVs purified from mouse. RNP-loaded EVs from 200 μL serum were then injected in TA muscles of hDMD/mdx mice. Mice were sacrificed 1 week later, gDNA was extracted from muscles, and DMD gene editing was analyzed by PCR. As seen in Figure 7B, EVs or RNPs alone were inefficient to produce the edited band. The edited band was sequenced (Figure 7C), and this confirmed the efficient modification of the DMD gene. This experiment opens perspectives for human dystrophin expression recovery after an EV/RNP treatment.

Figure 7.

Serum EVs for delivery of RNPs targeting human DMD gene

(A) Schematic representation of a part of the human DMD gene coding for dystrophin with gRNAs (crRNA/tracRNA) and primers used. (B) hDMD/mdx mouse were injected in muscles with EVs purified from mouse or human serum loaded with SpCas9/gRNA50 and SpCas9/gRNA54 and sacrificed 8 days after the treatment. DNA was analyzed by PCR. Mouse control (-), mEVs, RNPs only, mEV/RNPs. Control: HeLa/Ai9 treated with hEV/RNPs. (C) Sequence of the edited band of DMD from PCR amplification of DNA extracted from hDMD/mdx mouse muscle treated with mEV/RNPs.

Discussion

CRISPR technology has been regarded as one of the most promising therapeutic avenues for correction of DMD causative mutations.43 Indeed, many approaches using CRISPR tools have been used to restore dystrophin expression: transcriptional modulation using a catalytic deficient Cas9 (dCas9), exon deletion, reframing, or skipping, and, more recently, precise point-mutation correction with base or prime editing.18,43,44 AAV is the most commonly used vector for DMD gene therapy because of its high efficiency to target muscles.43 However, viral delivery raises important limitations and safety issues for clinical applications.45 The high cost of production of viral vectors also limits the accessibility to treatments. Moreover, high doses of AAV vectors have been shown to induce neuronal toxicity and cellular immune response in non-human primates.19,45 Recently three tragic deaths were reported in an AAV-based gene therapy trials for X-linked myotubular myopathy46 and one death in a patient with DMD. This presses the need to develop highly efficient non-viral delivery systems.

Artificially engineered lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have been widely used for vaccines or drug delivery.47 LNPs benefit from a high loading efficacy; however, the fast clearance by the immune system and the toxicity issues48 limit their uses in clinical trials. Moreover, it has been shown that EV-cargo delivery is several orders of magnitude more efficient than synthetic systems.49

The EV delivery system has obvious advantages over viral vector and artificial vesicles due to the biological origin. Since EVs are made of natural cell surface, immune response activation toward circulating particles is reduced, and this allows for the efficient transport of their cargo to distant target cells, even crossing the blood-brain barrier.50,51 Even if AAV vectors are mostly episomal, vector genome could integrate at low frequency into host chromosomal genome and preferentially into actively transcribed genes.52 The delivery of proteins by EVs completely avoids the risk of insertional mutagenesis.

Because of their bacterial origin, CRISPR components can also generate an immune response in vivo that could impair gene-editing efficiency.53,54 Such humoral and cellular immune responses can be greatly reduced by the use of short-life RNP complexes in contrast to long-lasting expression associated with viral or DNA vectors.55

The off-target effects by the CRISPR system are one of the major constraints for their use in gene-therapy clinical trials.56 Delivery by viral vectors is more prone to generating off-target cleavage sites, as host DNA is exposed to Cas9 for extended periods of time. However, transient RNP delivery largely reduces non-specific Cas9 editing activity in exposed cells.55 Therefore, EV-based delivery of Cas9 RNPs increases the safety issue for gene-therapy development.

Many publications have shown efficient packaging and delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 components by EVs derived from human cell HEK293T.27,57,58 However, tumor-cell-derived EVs could also transfer their own cargos possibly containing oncogenic elements and, thus, trigger pre-metastatic niches.59,60 These cell-derived EVs were also shown to have an impact on tumor invasion by increasing motility of cancer cells.61 Moreover, delivery of EVs produced by HEK293T required VSV-G expression in order to be efficient for cargo delivery.24,62 Unfortunately, VSV-G proteins at the surface of vesicles induce a robust immune response that is undesired for therapeutic administration.63 Since EV co-delivery of indigenous biomolecules along with therapeutic cargos may have an impact on treatment issue, the cell origin of EVs should be considered. One of the most advantageous features of EVs originating from serum is their lack of immunogenicity22 and their convenient accessibility. In the present article, we showed that EVs purified from serum could be an efficient and safe delivery system of CRISPR editing components to muscles.

To achieve transfer of RNPs into EVs, we used cationic-lipid-mediated transfectant lipofectamine CM that showed very low cell toxicity.64 This cationic-lipid solution is highly efficient to transfect RNPs in cells in vitro without the need of EVs as delivery vehicles. However, for RNP delivery in mouse muscle, the transfectant alone with RNPs was not sufficient to produce significant gene modifications in the three mouse models that we used. The presence of EVs in the preparation was essential to efficiently spread and transfer active SpCas9 protein to muscle fibers. Cationic lipids in nanoparticles have been shown to contribute to cytoplasmic membrane fusion and disruption of endosomal membrane.65 However, it is not clear if the transfectant still present in the EV/RNP preparation contributed to cell uptake and/or endosomal release in our mouse muscle experiments. We think that during incubation with CM, the lipid transfectants may have been integrated in the EV membranes and may have changed the EV interaction with the host membranes. Unfortunately, we were not able to evaluate how much transfectant is present in our EV preparations and the impact of this modification on the EV uptake into muscle fibers. Up to now, we have not found other efficient protocols for SpCas9 protein loading in serum EVs that could be free of cationic lipids in order to assess this question. The concentrations of Cas9 protein in EV preparations obtained by other loading methods (electroporation, extrusion) were too low for these methods to be tested in mouse muscles.

In summary, the present work showed efficient in vivo genome editing using serum-derived EVs as delivery vehicles for SpCas9-RNP. We were able to produce up to 10% gene modifications using double cleavage by the CRISPR system in different mouse models. Compared with other recently described technologies, our system displays several advantages. It allows for transient editing activity delivered in vivo as RNAs and proteins, thus reducing harmful off-target side effects from long exposure to SpCas9 nuclease. Serum-derived EVs are non-immunologic and safe, and a high yield of particles can be easily achieved at low cost. Although these studies open encouraging perspectives, the field of EV-mediated therapeutics would benefit from research progress in EV systemic delivery. For now, EVs are more prone to accumulate in liver and spleen after i.v. injection.66,67 Further development in EV surface engineering to successfully deliver CRISPR-Cas RNPs into specific target tissues would facilitate CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing treatments for future clinical trials.

Material and methods

EV purification by SEC

Pool human serum off the clot (ISER100) and Grade US Origin Mouse CD1 serum (IGMSCD1SER100ML) were provided by Innovative Research (Novi, MI, USA). Fifteen mL of serum was initially centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 30 min 4°C to pellet big aggregates. Floating lipoproteins at the surface were removed, and 10 mL of serum from the bottom was taken and passed through a 0.45 μm membrane filter. The serum was then loaded onto an Amicon Ultra-15 100 kDa (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) with 5 mL of PBS and concentrated to about 2 mL by centrifugation at 4,000 × g. The concentrate was then diluted with PBS to 15 mL and spun again to obtain a concentrate of about 2.5 mL. This step was repeated twice. The extract was then loaded on a size exclusion column (SEC qEV10/70 nm, IZON Science, Somerville, MA, USA), and EVs were purified according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. EV extract was then concentrated, and for in vivo studies, the buffer was exchanged for a solution of 5% glucose by centrifugation using Amicon Ultra-0.5 (Millipore). The final extract was adjusted to 1 or 10 mL, depending on the experiment specification.

EV characterization and hs-FCM analysis

Protein concentration was determined by Pierce BCA microplate assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Sizes and concentrations of EVs were measured using the ZetaSizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) and Zetasizer software (v.7.11) (Malvern Instruments). EV extracts were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with a TECNAI Spirit G2 Biotwin 120 kV microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA). EVs were transferred to a carbon formvar-coated grid and fixed with a 2.5% solution glutaraldehyde in cacodylate 0.1 M. Samples were washed in water before staining for 1 min in 1% uranyl acetate solution and then washed again in water and dried before TEM observation.

hs-FCM analysis was performed on a BD Canto II Special Order Research Product (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) equipped with a small-particle option, as described previously.32 hs-FCM performance tracking was verified before analyses using the BD cytometer setup and tracking beads (BD Biosciences). The assigned voltage for the parameters were the following: for FSC-PMT, 360 V; SSC-H, 450 V; FSC-H, 160 V; GFP and CT CFSE, 400 V; CT violet, 380 V; CT far red, 400 V; and APC, 530 V. Acquisition was performed at low speed (∼10 μL/min). Events were quantified by adding a known quantity of 2 µm Cy5-labelled silica beads (Nanocs, New York, NY, USA) right before analysis, a constant number of beads was then used for all samples throughout experiments. For analysis, green fluorescent FCM sub-micron beads of 100 nm, 200 nm, 500 nm, and 1 μm and CT violet, CT CFSE, and CT far red were purchased from Life Technology (Eugene, OR, USA). Before hs-FCM analysis, EVs were labeled with 50 μM of CT violet (or CT CFSE or CT far red, when specified) for 30 min at 37°C, and excess label was removed by ultrafiltration using Amicon-0.5 100 kDa (Millipore). SpCas9-GFP used for the analysis was purchased from applied Biological Materials (Richmond, BC, Canada). APC-anti human CD9 (HI9a) and APC mouse IgG Ctrl (MOPC-21) were purchased from BioLegend. For antibody labeling, 5 μL of EV preparation (derived from 5 μL serum) was mixed in 40 μL of 0.1 μm filtered PBS/BSA 0.5% with 5 μL of antibodies (6 ng/mL) for 30 min at room temperature (RT) in the dark. Samples were diluted in 450 μL of filtered PBS prior to analysis. For lysis treatment, 5 μL of EV samples were mixed with 5 μL of 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS and incubated for 30 min at RT prior to antibodies labeling. Data were acquired with BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences) and exported and analyzed with FlowJo software v.10.8.1 (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA).

EV purification by UC

One mL of human serum (Innovative Research) was initially centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Five hundred μL were taken from the bottom of the tube without disturbing the lipid layer floating on the top. Serum was filtered through a 0.65 μm membrane and then loaded onto an Amicon Ultra-0.5 100 kDa (Millipore). The concentrate was washed twice with 500 μL of PBS using this centrifugation units. The extract was then mixed with PBS to reach 5 mL. Samples were ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C in an SW-55 ti rotor. The liquid phase was carefully removed, and the pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of PBS.

RNA guide selection and production of Cas9 RNP complexes

RNA guide sequences for DMD gene were previously described.12 The other RNA guide sequences were designed using CRISPR RGEN Tools (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-designer/). SpCas9 (Alt-R SpCas9 Nuclease V3) and RNA guides (Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA XT; Alt-R CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA) were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA USA). SpCas9 was complexed with crRNA/trRNA according to IDT instructions for SpCas9 RNP formation. New complexes were prepared before each experiment.

Reporter Ai9 cells

Plasmid DNA Ai9 from Addgene (cat no. 22799, Watertown, MA, USA) was digested with XhoI (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in HeLa and Neuro-2a (N2a) cells cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco) containing 10% FBS (Invitrogen) together with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL and 100 mg/mL) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. The cells were incubated for 2 days to allow expression of the antibiotic resistance gene and then selected with 600 μg/mL for HeLa cells or 400 μg/mL for N2a cells of geneticin (G418) for 14 days. The colonies were isolated and tested with RNPs of SpCas9/Ai9-A1 and SpCas9/Ai9-A2 gRNAs transfected with Lipofectamine CM (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. TdTomato+ cells were analyzed by fluorescent microscopy and FCM.

FCM

Cells were harvested and washed twice with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were fixed with 4% PFA. The percentages of tdTomato+ cells were determined using BD FACSCanto II (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The cytometry was performed at the imagery and cytometry platform (Center de recherche du CHU de Québec-Université Laval).

Formation of EVs/RNP delivery vehicles for in vitro experiment

Cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 35,000 cells/well. Twenty-four h later, culture media was replaced by DMEM supplemented with 10% exosome-depleted FBS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transfectant CM was used for RNP loading into EVs. For that, 1 μL of newly formed RNPs (made of 18 pmol of SpCas9 and 22 pmol of gRNAs) were mixed with 40 μL of PBS and 1.5 μL of transfectant. Ten μL of purified EV extract from 100 μL of mouse or human serum was then added to RNP preparations. As control, RNPs or EVs were exchanged for equal volume of PBS. The preparations were incubated for 10–20 min. Samples were filtered and concentrated again with Amicon-0.5. Extracts were then added to cell culture media and incubated for 2–3 days. Positive fluorescent red cells in HeLa/Ai9 or N2a/Ai9 were visualized under fluorescent microscopy. Cells were treated with 0.5% trypsin, transferred to a tube, and recovered by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 5 min, PBS washed twice, and subjected to DNA extraction.

Formation of EVs/RNP delivery vehicles for in vivo experiment

For each 15 μL muscle injection, 2 μL of RNPs made of 44 pmol of hybrid gRNA (cr/tracrRNA) and 36 pmol of SpCas9 were diluted in 80 μL of PBS containing 3 μL of CM. Twenty μL of purified EV extract from 200 μL mouse or human serum was added to the RNP solution and incubated for 10 min. As control, RNPs or EVs were replaced by equal volume of PBS. The preparations were then submitted to ultrafiltration on Amicon-0.5 100 kDa (Millipore). Concentrated extracts were diluted in 5% glucose in PBS and centrifuged again before a final filtration through 0.45 μm polyethersulfone (PES) filter (Millipore).

Injection of EVs/RNPs in mice

All the experiments with mice were conducted after approval by the CRCHUL Animal Care Committee and in agreement with the guidelines of the Canadian Council for Animal Care. Rosa26-tdTomato (also known as Ai9 or RCL-tdT; #007905) transgenic mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and generously given to us by Dr. Steve Lacroix (Univ. Laval). All mouse lines were bred in house at the Animal Facility of the CHU de Québec-Université Laval Research Center. Rag/mdx mice were produced in our animal facilities by crossing mdx/mdx mice (a DMD model due to a point mutation in exon 23 of the DMD gene leading to dystrophin deficiency) with Rag-/- mice (an immunodeficient mouse that accepts human grafts). Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions. The hDMD/mdx mouse (a gift from Dr. A. Aartsma-Rus) contains the full human DMD gene (2.4 Mb) (coding for dystrophin) stably integrated into chromosome 5 of the mdx mouse.68

The EVs were injected in the TA muscles of recipient mice. Briefly, the animals were placed under anesthesia with Isoflurane USP (Abbott Laboratories, Montreal, QC, Canada). The skin was shaved to expose the TA, and 15 μL of EV extract purified from 200 μL of serum loaded with RNPs (or not) was slowly injected obliquely using a glass micropipette into 7 to 12 sites of the TA. Mice were sacrificed after 7 days (for Ai9 and hDMD/mdx mice) or 3 weeks (for mdx mice). TA muscles were removed, mounted in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) embedding compound, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Several cryosections (12 μm tick) were generated for histological analysis, and the rest of the tissues were kept for RNA and genomic DNA purification.

DNA extraction and PCR analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the phenol:chloroform method. Briefly, cell pellets were suspended in 100 μL of lysis buffer containing 10% sarcosyl and 0.5 M (pH 8) EDTA. Twenty μL of proteinase K (10 mg/mL) was added to the extract, and the suspension was incubated for 10–15 min at 55°C. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,200 RPM for 5 min. The supernatant was collected in a new tube, and one volume of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl was added. Aqueous phase was recovered by centrifugation and transferred to a new tube with equal volume of chloroform. After centrifugation, aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 0.1 volume of 5 M NaCl and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol. DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 13,200 RPM for 20 min. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, and DNA were resuspended in distilled water.

For DNA extraction from mouse muscles, unused cryostat muscle sections were suspended in 450 μL of lysis buffer containing 20% SDS, 0.5 M (pH 8) EDTA, and 1 M (pH 8) Tris HCl. Fifty μL of proteinase K (20 mg/mL) was added to the solution, and the suspension was incubated overnight at 55°C. One volume (500 μL) of the bottom phase of phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol solution was added to the samples, which were then centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 3 min. This step was repeated to ensure total removal of the OCT cryomatrix used to envelop muscle tissue for slicing. The top layer was collected in a new tube, and 500 μL of chloroform was added. The aqueous phase was recovered by centrifugation (12,000 RPM, 3 min) and transferred to a new tube before precipitation with 0.1 volume of 5 M NaCl and 2 volumes of 100% ethanol. DNA was recovered by centrifugation at 12,000 RPM for 8 min. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, and DNA were resuspended in distilled water. Genomic DNA concentrations were determined with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT, USA).

PCR-amplified fragments were generated using CloneAmp PCR kit or Terra PCR direct polymerase mix (Takara Bio, Mountain View, CA, USA) using the primers listed in Table S1. The PCR reaction was carried out using 100 ng of DNA under the following conditions: Ai9: 98°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 56.4°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 50 s, and one cycle at 72°C for 5 min; mdx: 98°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 20 s, and one cycle at 72°C for 5 min; and hDMD/mdx: (Terra PCR) 98°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 98°C for 10 s, 59.3°C for 15 s, and 68°C for 20 s, and one cycle at 68°C for 5 min. 22.5 μL of the PCR product was separated by gel electrophoresis on a 1% (Ai9) or 1.5% (mdx and hDMD/mdx) agarose gel in TBE buffer. The gel was visualized on a Molecular Imager VersaDoc MP 4000 system (BioRad, Mississauga, ON, Canada). PCR products were then sequenced by Sanger sequencing at the CHU de Québec-Université Laval Research Center sequencing platform, and the resulting .ab files were used for their characterization using the TIDE tool provided at https://tide.nki.nl/.

qPCR analysis

Mdx mutation analysis by qPCR was made on cDNA. For that, total RNA was isolated from embedded muscle sections according to the manufacturer’s protocol for TRI reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The first cDNA strand was synthesized from the total RNA in a 20 μL reaction system using the Applied Biosystem High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific). To evaluate the ratio of genomic DNA modified by SpCas9 in mouse muscle, 100 ng of gDNA from Ai9 muscle sections or 5 ng of cDNA from mdx extracts were subjected to qPCR (Bio-Rad C1000 Touch thermocycler) using PrimeTime Gene Expression master mix (IDT) and the primers and probe listed in Table S1 according to the manufacture’s protocol. Ratios were deduced from qPCR on an expected deleted fragment compared with an untargeted region of the same gene.

Immunohistochemistry and H&E staining

Frozen muscles were processed with a Cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Concordia, ON, Canada) to obtain 12 μm thick transversal sections that were placed on a glass slide pre-coated with glycine. Cryosections of muscle tissue were first washed 3 times for 5 min with PBS 1X and then blocked for 1 h in a blocking solution (PBS supplemented with 10% FBS). The primary antibody directed against dystrophin (cat no. MAB1453, Abnova, Walnut, CA, USA) was diluted 1/30 in the blocking solution and incubated overnight at 4°C. After 3 washing steps of 5 min with PBS at RT, a secondary antibody, a rabbit anti-mouse-botinylated (cat no. A90-117B, Cedarlane Labs, Burlington, ON, Canada), was diluted 1/500 in the blocking solution and incubated for another 1 h at RT. Next, samples were washed 3 times for 5 min with PBS and then incubated for 1 h at RT with Streptavidin ALEXA FLUOR 546 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) diluted 1/500 in blocking solution. Following 3 washes of 5 min with PBS, cryosections were mounted with PBS/glycerol (50/50) solution and observed under fluorescent microscope.

For H&E staining, muscle sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin Stain Kit (ScyTek Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After four dips in absolute alcohol for dehydration, slides were mounted in resin mounting medium (Sigma-Aldrich Canada, Oakville, ON, Canada) and observed under light microscopy.

Statistical analysis

The results presented were analyzed with Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, SanDiego, CA, USA). All error bars are SD.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grants from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Foundation for Cell and Gene Therapy (Jesse’s Journey), the LaForce Foundation, and from the FRQS TheCell network.

Author contributions

N.M. and J.P.T. designed the experiments; N.M., A.F.-A., C.G., J.R., and P.Y. conducted the experiments; and N.M. wrote the paper with the help of J.P.T. and A.F.-A.

Declaration of interests

There is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.05.023.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Duan D., Goemans N., Takeda S., Mercuri E., Aartsma-Rus A. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2021;7:13. doi: 10.1038/s41572-021-00248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendell J.R., Al-Zaidy S.A., Rodino-Klapac L.R., Goodspeed K., Gray S.J., Kay C.N., Boye S.L., Boye S.L., Geroge L.A., Salabarria S., et al. Current clinical applications of in vivo gene therapy with AAVs. Mol. Ther. 2020;29:464–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aartsma-Rus A., Corey D.R. The 10th oligonucleotide therapy approved: golodirsen for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2020;30:67–70. doi: 10.1089/nat.2020.0845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mendell J.R., Sahenk Z., Lehman K., Nease C., Lowes L.P., Miller N.F., Iammarino M.A., Alfano L.N., Nicholl A., Al-Zaidy S., et al. Assessment of systemic delivery of rAAVrh74.MHCK7.micro-dystrophin in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:1122. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies K.E., Guiraud S. Micro-dystrophin genes bring hope of an effective therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:486–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramos J.N., Hollinger K., Bengtsson N.E., Allen J.M., Hauschka S.D., Chamberlain J.S. Development of novel micro-dystrophins with enhanced functionality. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:623–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan D. Systemic AAV micro-dystrophin gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:2337–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan D. Micro-dystrophin gene therapy goes systemic in Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018;29:733–736. doi: 10.1089/hum.2018.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Happi Mbakam C., Lamothe G., Tremblay G., Tremblay J.P. CRISPR-Cas9 gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurotherapeutics. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s13311-022-01197-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gee P., Lung M.S.Y., Okuzaki Y., Sasakawa N., Iguchi T., Makita Y., Hozumi H., Miura Y., Yang L.F., Iwasaki M., et al. Extracellular nanovesicles for packaging of CRISPR-Cas9 protein and sgRNA to induce therapeutic exon skipping. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1334. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14957-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amoasii L., Long C., Li H., Mireault A.A., Shelton J.M., Sanchez-Ortiz E., McAnally J.R., Bhattacharyya S., Schmidt F., Grimm D., et al. Single-cut genome editing restores dystrophin expression in a new mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaan8081. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyombe-Engembe J.P., Ouellet D.L., Barbeau X., Rousseau J., Chapdelaine P., Lague P., Tremblay J.P. Efficient restoration of the dystrophin gene reading frame and protein structure in DMD myoblasts using the CinDel method. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2016;5:e283. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duchene B.L., Cherif K., Iyombe-Engembe J.P., Guyon A., Rousseau J., Ouellet D.L., Barbeau X., Lague P., Tremblay J.P. CRISPR-induced deletion with SaCas9 restores dystrophin expression in dystrophic models in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Ther. 2018;26:2604–2616. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson C.E., Hakim C.H., Ousterout D.G., Thakore P.I., Moreb E.A., Rivera R.M.C., Madhavan S., Pan X., Ran F.A., Yan W.X., et al. In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016;351:403–407. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabebordbar M., Zhu K., Cheng J.K.W., Chew W.L., Widrick J.J., Yan W.X., Maesner C., Wu E.Y., Xiao R., Ran F.A., et al. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science. 2016;351:407–411. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu L., Park K.H., Zhao L., Xu J., El Refaey M., Gao Y., Zhu H., Ma J., Han R. CRISPR-mediated genome editing restores dystrophin expression and function in mdx mice. Mol. Ther. 2016;24:564–569. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K., Conboy M., Park H.M., Jiang F., Kim H.J., Dewitt M.A., Mackley V.A., Chang K., Rao A., Skinner C., et al. Nanoparticle delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein and donor DNA in vivo induces homology-directed DNA repair. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017;1:889–901. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0137-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chemello F., Chai A.C., Li H., Rodriguez-Caycedo C., Sanchez-Ortiz E., Atmanli A., Mireault A.A., Liu N., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E.N. Precise correction of Duchenne muscular dystrophy exon deletion mutations by base and prime editing. Sci. Adv. 2021;7:eabg4910. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg4910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullard A. Gene therapy community grapples with toxicity issues, as pipeline matures. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021;20:804–805. doi: 10.1038/d41573-021-00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boutin S., Monteilhet V., Veron P., Leborgne C., Benveniste O., Montus M.F., Masurier C. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010;21:704–712. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolous N.S., Chen Y., Wang H., Davidoff A.M., Devidas M., Jacobs T.W., Meagher M.M., Nathwani A.C., Neufeld E.J., Piras B.A., et al. The cost-effectiveness of gene therapy for severe hemophilia B: a microsimulation study from the United States perspective. Blood. 2021;138:1677–1690. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021010864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsharkasy O.M., Nordin J.Z., Hagey D.W., de Jong O.G., Schiffelers R.M., Andaloussi S.E., Vader P. Extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems: why and how? Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;159:332–343. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan J., Pan J., Zhang X., Chen Y., Zeng Y., Huang L., Ma D., Chen Z., Wu G., Fan W. A peptide derived from the N-terminus of charged multivesicular body protein 6 (CHMP6) promotes the secretion of gene editing proteins via small extracellular vesicle production. Bioengineered. 2022;13:4702–4716. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao X., Lyu P., Yoo K., Yadav M.K., Singh R., Atala A., Lu B. Engineered extracellular vesicles as versatile ribonucleoprotein delivery vehicles for efficient and safe CRISPR genome editing. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2021;10:e12076. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z., Zhou X., Wei M., Gao X., Zhao L., Shi R., Sun W., Duan Y., Yang G., Yuan L. In vitro and in vivo RNA inhibition by CD9-HuR functionalized exosomes encapsulated with miRNA or CRISPR/dCas9. Nano Lett. 2019;19:19–28. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dooley K., McConnell R.E., Xu K., Lewis N.D., Haupt S., Youniss M.R., Martin S., Sia C.L., McCoy C., Moniz R.J., et al. A versatile platform for generating engineered extracellular vesicles with defined therapeutic properties. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:1729–1743. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horodecka K., Duchler M. CRISPR/Cas9: principle, applications, and delivery through extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6072. doi: 10.3390/ijms22116072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhuang J., Tan J., Wu C., Zhang J., Liu T., Fan C., Li J., Zhang Y. Extracellular vesicles engineered with valency-controlled DNA nanostructures deliver CRISPR/Cas9 system for gene therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:8870–8882. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leng L., Dong X., Gao X., Ran N., Geng M., Zuo B., Wu Y., Li W., Yan H., Han G., Yin H. Exosome-mediated improvement in membrane integrity and muscle function in dystrophic mice. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:1459–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang J., Nguyen L.T.H., Hickey R., Walters N., Wang X., Kwak K.J., Lee L.J., Palmer A.F., Reategui E. Immunomagnetic sequential ultrafiltration (iSUF) platform for enrichment and purification of extracellular vesicles from biofluids. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:8034. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86910-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monguio-Tortajada M., Galvez-Monton C., Bayes-Genis A., Roura S., Borras F.E. Extracellular vesicle isolation methods: rising impact of size-exclusion chromatography. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2019;76:2369–2382. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03071-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcoux G., Duchez A.C., Cloutier N., Provost P., Nigrovic P.A., Boilard E. Revealing the diversity of extracellular vesicles using high-dimensional flow cytometry analyses. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35928. doi: 10.1038/srep35928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maia J., Batista S., Couto N., Gregório A.C., Bodo C., Elzanowska J., Strano Moraes M.C., Costa-Silva B. Employing flow cytometry to extracellular vesicles sample microvolume analysis and quality control. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;8:593750. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.593750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morales-Kastresana A., Telford B., Musich T.A., McKinnon K., Clayborne C., Braig Z., Rosner A., Demberg T., Watson D.C., Karpova T.S., et al. Labeling extracellular vesicles for nanoscale flow cytometry. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1878. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01731-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Théry C., Witwer K.W., Aikawa E., Alcaraz M.J., Anderson J.D., Andriantsitohaina R., Antoniou A., Arab T., Archer F., Atkin-Smith G.K., et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bari S.M.I., Hossain F.B., Nestorova G.G. Advances in biosensors technology for detection and characterization of extracellular vesicles. Sensors. 2021;21:7645. doi: 10.3390/s21227645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simonsen J.B. What are we looking at? extracellular vesicles, lipoproteins, or both? Circ. Res. 2017;121:920–922. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.117.311767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brennan K., Martin K., FitzGerald S.P., O’Sullivan J., Wu Y., Blanco A., Richardson C., Mc Gee M.M. A comparison of methods for the isolation and separation of extracellular vesicles from protein and lipid particles in human serum. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:1039. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57497-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takov K., Yellon D.M., Davidson S.M. Comparison of small extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma by ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography: yield, purity and functional potential. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2018;8:1560809. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1560809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Willms E., Johansson H.J., Mäger I., Lee Y., Blomberg K.E.M., Sadik M., Alaarg A., Smith C.E., Lehtio J., EL Andaloussi S., et al. Cells release subpopulations of exosomes with distinct molecular and biological properties. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:22519. doi: 10.1038/srep22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Madisen L., Zwingman T.A., Sunkin S.M., Oh S.W., Zariwala H.A., Gu H., Ng L.L., Palmiter R.D., Hawrylycz M.J., Jones A.R., et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:133–140. doi: 10.1038/nn.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.t Hoen P.A., de Meijer E.J., Boer J.M., Vossen R.H., Turk R., Maatman R.G., Davies K.E., van Ommen G.J.B., van Deutekom J.C., den Dunnen J.T. Generation and characterization of transgenic mice with the full-length human DMD gene. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5899–5907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m709410200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi E., Koo T. CRISPR technologies for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:3179–3191. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryu S.M., Koo T., Kim K., Lim K., Baek G., Kim S.T., Kim H.S., Kim D., Lee H., Chung E., Kim J.S. Adenine base editing in mouse embryos and an adult mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:536–539. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colella P., Ronzitti G., Mingozzi F. Emerging issues in AAV-mediated in vivo gene therapy. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2018;8:87–104. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson J.M., Flotte T.R. Moving forward after two deaths in a gene therapy trial of myotubular myopathy. Hum. Gene Ther. 2020;31:695–696. doi: 10.1089/hum.2020.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shepherd S.J., Issadore D., Mitchell M.J. Microfluidic formulation of nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2021;274:120826. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cronin J.G., Jones N., Thornton C.A., Jenkins G.J.S., Doak S.H., Clift M.J.D. Nanomaterials and innate immunity: a perspective of the current status in nanosafety. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2020;33:1061–1073. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.0c00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy D.E., de Jong O.G., Evers M.J.W., Nurazizah M., Schiffelers R.M., Vader P. Natural or synthetic RNA delivery: a stoichiometric comparison of extracellular vesicles and synthetic nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2021;21:1888–1895. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c00094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ha D., Yang N., Nadithe V. Exosomes as therapeutic drug carriers and delivery vehicles across biological membranes: current perspectives and future challenges. Acta Pharm. Sin B. 2016;6:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Banks W.A., Sharma P., Bullock K.M., Hansen K.M., Ludwig N., Whiteside T.L. Transport of extracellular vesicles across the blood-brain barrier: brain pharmacokinetics and effects of inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4407. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarty D.M., Young S.M., Jr., Samulski R.J. Integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) and recombinant AAV vectors. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:819–845. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.143717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moreno A.M., Palmer N., Aleman F., Chen G., Pla A., Jiang N., Leong Chew W., Law M., Mali P. Immune-orthogonal orthologues of AAV capsids and of Cas9 circumvent the immune response to the administration of gene therapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:806–816. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0431-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hakim C.H., Kumar S.R.P., Pérez-López D.O., Wasala N.B., Zhang D., Yue Y., Teixeira J., Pan X., Zhang K., Million E.D., et al. Cas9-specific immune responses compromise local and systemic AAV CRISPR therapy in multiple dystrophic canine models. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6769. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26830-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Doudna J.A. The promise and challenge of therapeutic genome editing. Nature. 2020;578:229–236. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1978-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang B. CRISPR/Cas gene therapy. J. Cell Physiol. 2021;236:2459–2481. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kostyushev D., Kostyusheva A., Brezgin S., Smirnov V., Volchkova E., Lukashev A., Chulanov V. Gene editing by extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7362. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han Y., Jones T.W., Dutta S., Zhu Y., Wang X., Narayanan S.P., Fagan S.C., Zhang D. Overview and update on methods for cargo loading into extracellular vesicles. Processes. 2021;9:356. doi: 10.3390/pr9020356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maacha S., Bhat A.A., Jimenez L., Raza A., Haris M., Uddin S., Grivel J.C. Extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication: roles in the tumor microenvironment and anti-cancer drug resistance. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:55. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-0965-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kogure A., Yoshioka Y., Ochiya T. Extracellular vesicles in cancer metastasis: potential as therapeutic targets and materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:4463. doi: 10.3390/ijms21124463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Becker A., Thakur B.K., Weiss J.M., Kim H.S., Peinado H., Lyden D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: cell-to-cell mediators of metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:836–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yip B.H. Recent advances in CRISPR/Cas9 delivery strategies. Biomolecules. 2020;10:839. doi: 10.3390/biom10060839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Munis A.M., Bentley E.M., Takeuchi Y. A tool with many applications: vesicular stomatitis virus in research and medicine. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020;20:1187–1201. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2020.1787981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu X., Liang X., Xie H., Kumar S., Ravinder N., Potter J., de Mollerat du Jeu X., Chesnut J.D. Improved delivery of Cas9 protein/gRNA complexes using lipofectamine CRISPRMAX. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016;38:919–929. doi: 10.1007/s10529-016-2064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang S., Shen J., Li D., Cheng Y. Strategies in the delivery of Cas9 ribonucleoprotein for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Theranostics. 2021;11:614–648. doi: 10.7150/thno.47007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wiklander O.P.B., Nordin J.Z., O'Loughlin A., Gustafsson Y., Corso G., Mager I., Vader P., Lee Y., Sork H., Seow Y., et al. Extracellular vesicle in vivo biodistribution is determined by cell source, route of administration and targeting. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2015;4:26316. doi: 10.3402/jev.v4.26316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang M., Jordan V., Blenkiron C., Chamley L.W. Biodistribution of extracellular vesicles following administration into animals: a systematic review. J. Extracell. Vesicles. 2021;10:e12085. doi: 10.1002/jev2.12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Veltrop M., van Vliet L., Hulsker M., Claassens J., Brouwers C., Breukel C., van der Kaa J., Linssen M.M., den Dunnen J.T., Verbeek S., et al. A dystrophic Duchenne mouse model for testing human antisense oligonucleotides. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.