Abstract

A monoterpene ɛ-lactone hydrolase (MLH) from Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14, catalyzing the ring opening of lactones which are formed during degradation of several monocyclic monoterpenes, including carvone and menthol, was purified to apparent homogeneity. It is a monomeric enzyme of 31 kDa that is active with (4R)-4-isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone and (6R)-6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, lactones derived from (4R)-dihydrocarvone, and 7-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, the lactone derived from menthone. Both enantiomers of 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone were converted at equal rates, suggesting that the enzyme is not stereoselective. Maximal enzyme activity was measured at pH 9.5 and 30°C. Determination of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified MLH enabled cloning of the corresponding gene by a combination of PCR and colony screening. The gene, designated mlhB (monoterpene lactone hydrolysis), showed up to 43% similarity to members of the GDXG family of lipolytic enzymes. Sequencing of the adjacent regions revealed two other open reading frames, one encoding a protein with similarity to the short-chain dehydrogenase reductase family and the second encoding a protein with similarity to acyl coenzyme A dehydrogenases. Both enzymes are possibly also involved in the monoterpene degradation pathways of this microorganism.

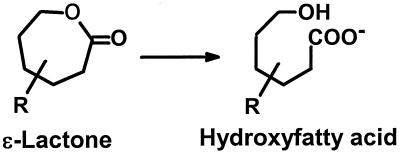

Lactones, internal cyclic monoesters, are ubiquitous in nature and have been identified in all major classes of foods, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, meat, milk products, and baked products, contributing to taste and flavor nuances (13). The organoleptically important lactones generally have γ- or δ-lactone structures (five- or six-membered ring structures), while a few are macrocyclic (29). Lactones are intermediates in microbial degradation pathways of alicyclic compounds (1, 5, 32) but have also been implicated in certain microbial aromatic degradation pathways (ortho cleavage pathways) (14, 19). The degradation of lactones is accomplished by the activity of lactone hydrolase, which catalyzes the hydrolysis of lactones to the corresponding hydroxy acids (Fig. 1). Lactone hydrolases are commercially applied for the debittering of triterpenes present in citrus juices (15) and for the production of the vitamin d-pantothenate (T. Morikawa, K. Wada, S. Kita, K. Tuzaki, K. Sakamoto, M. Kataoka, S. Shimizu, and H. Yamada, Book Abstr. 6th Japanese-Swiss Meet. Bio/Technol., p. 34–35, 1998).

FIG. 1.

Reaction catalyzed by ɛ-lactone hydrolases.

The application of Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases (BVMOs) seems an attractive option for the production of lactones (12, 31). BVMOs are enzymes catalyzing the insertion of one atom of oxygen next to an alicyclic keto group, thus forming lactones. However, BVMOs are relatively unstable enzymes that generally use the very expensive NADPH as the cofactor (31). Therefore, the application of whole cells of BMVO activity containing microorganisms is a prerequisite to ascertain in situ cofactor regeneration and to increase the stability of the enzyme. However, most microorganisms containing BVMO activity also have a high lactone hydrolase activity, resulting in a simultaneous degradation of the product of interest. Therefore, a lactone hydrolase activity-negative mutant of the biocatalyst should be constructed, for instance by gene disruption, to achieve accumulation of the lactone.

Recently, we purified and characterized a BVMO from Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14 involved in the degradation of monocyclic monoterpenes (27). This BVMO has a broad substrate specificity, catalyzing the lactonization of a large number of monocyclic monoterpene ketones and substituted cyclohexanones. However, monoterpene-grown cells of this strain also contain a very high monoterpene ɛ-lactone hydrolase (MLH) activity (25, 28). In this paper, we report on the purification, characterization, gene cloning, and sequence determination of this novel enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

R. erythropolis DCL14 was previously isolated on (4R)-dihydrocarveol (25) and is maintained at the Division of Industrial Microbiology (CIMW 0387B, Wageningen, The Netherlands). R. erythropolis DCL14 was subcultured once a month and grown at 30°C on a yeast extract-glucose agar plate for 2 days, after which the plates were stored at room temperature. R. erythropolis DCL14 was grown in 5-liter Erlenmeyer flasks containing 1 liter of mineral salts medium (9) with a 0.01% (vol/vol) carbon source and fitted with rubber stoppers. The flasks were incubated at 30°C on a horizontal shaker oscillating at 1 Hz with an amplitude of 10 cm. After growth was observed, the concentration of the toxic substrates was increased with steps of 0.01% (vol/vol) until a total of 0.1% (vol/vol) carbon source had been added. With ethanol, succinate, and limonene-1,2-diol, cultures were grown in a 5-liter Erlenmeyer flask containing 1 liter of mineral salts medium supplemented with 3 g of the pertinent carbon source per liter. Cells for enzyme purification were cultivated in a fed-batch fermentor on (4R)-limonene as described previously (24). Cells were collected by centrifugation (4°C, 10 min at 16,000 × g) and washed with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0. The pellet was resuspended in 7 ml of this buffer and stored at −20°C until used.

Purification of MLH.

Cell extracts were prepared by sonication as described previously (24). Protein was determined by the method of Bradford (4) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. All purification steps were performed at 4°C and pH 7.0. If necessary, the pooled fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration with an Amicon ultrafiltration unit using a membrane with a molecular weight cutoff of 10,000 under nitrogen at a pressure of 4 × 105 Pa.

Step 1: gel filtration.

The cell extract (15 ml) was applied to a Sephacryl S300 (Pharmacia) column (2.5 by 98 cm) equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (flow rate, 0.75 ml/min; collected fraction volume was 7.5 ml). Fractions containing MLH activity were pooled.

Step 2: hydroxyapatite.

The pooled fractions from the gel filtration step were applied to a hydroxyapatite (Bio-Rad) column (5 by 6 cm) equilibrated with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer and eluted with the same buffer (flow rate, 0.3 ml/min; collected fraction volume was 3 ml). The fractions containing MLH activity were pooled.

Step 3: anion-exchange chromatography.

The pooled fractions from the hydroxyapatite step were applied to a DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (Pharmacia) column (2.5 by 31 cm) equilibrated with 25 mM potassium phosphate buffer. The column was washed with 100 ml of the same buffer (flow rate, 0.75 ml/min; collected fraction volume was 7.5 ml), and subsequently the enzyme was eluted with a 0 to 1 M linear gradient of NaCl in the same buffer (total volume, 1 liter). MLH activity eluted at an NaCl concentration of 300 mM. Fractions exhibiting MLH activity were pooled and concentrated.

Step 4: Mono Q.

One-milliliter samples of the concentrated MLH solution after step 3 (approximately 0.15 mg of protein) were applied to a Mono Q column (1.2 by 15 cm) operated with a fast protein liquid chromatography system (Pharmacia) at room temperature. The column was equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The enzyme was eluted using a 0 to 1 M NaCl gradient in the same buffer (flow rate, 1.0 ml/min; collected fraction volume was 1 ml). MLH eluted at an NaCl concentration of 400 mM. Fractions exhibiting MLH activity were pooled and concentrated.

Determination of molecular weight.

The molecular weight of the denatured protein was determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). An SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel was prepared by the method of Laemmli (11). Proteins were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G. The Pharmacia low-molecular-weight calibration kit, containing phosphorylase b (94,000), bovine serum albumin (67,000), ovalbumin (43,000), carbonic anhydrase (30,000), soybean trypsin inhibitor (20,100), and α-lactalbumin (14,400), was used for the estimation of the molecular weight.

The molecular weight of the native protein was determined by gel filtration on a Sephacryl S300 column as described under step 1 of the purification procedure. Bovine serum albumin (67,000), ovalbumin (43,000), chymotrypsinogen A (25,000), and limonene-1,2-epoxide hydrolase (16,520) were used as the reference proteins.

Assay of MLH activity.

MLH activity was determined by monitoring ɛ-caprolactone degradation by gas chromatography (GC). The reaction mixtures consisted of cell extract (10 to 100 μl) and 2 ml of a freshly prepared 5 mM ɛ-caprolactone solution in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) in 15-ml vials fitted with Teflon Mininert valves (Supelco Inc., Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands). The vials were placed in a shaking water bath (30°C), and after 5, 10, and 15 min, a vial was removed from the water bath and the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 ml of ethyl acetate. The vials were vigorously shaken to accomplish quantitative extraction of the lactone. The ethyl acetate layer was pipetted in a microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged (3 min, 15,000 × g) to achieve separation of the two layers. Subsequently, 1 μl of the ethyl acetate layer was analyzed by GC. For the determination of the pH optimum of enzyme catalysis, the Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) buffer in the standard assay was replaced with a 50 mM concentration of the other buffers. The effect of inhibitors and ions was studied by adding 0.1 to 10 mM effector to MLH. This mixture was preincubated at 30°C for 15 min, after which the MLH activity was determined as described above. The substrate preference of MLH was tested by incubating different amounts of MLH with 5 mM lactone in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 9.0) at 30°C. The samples were extracted with ethyl acetate and analyzed by GC.

Analytical methods.

All lactones were analyzed by chiral GC on a fused silica cyclodextrin capillary column (β-DEX 120; 30-m length, 0.25-mm internal diameter, 0.25-m film coating; Supelco). GC was performed on a Chrompack CP9000 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector using N2 as the carrier gas. The detector and injector temperatures were 250 and 200°C, respectively, and the split ratio was 1:50. ɛ-Caprolactone (retention time [rt] = 18.6 min) was analyzed isocratically at an oven temperature of 120°C. 4-Methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 16.12 and 16.37 min), 5-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 16.72 and 17.03 min), 6-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 15.12 and 15.35 min), and 7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 12.27 and 12.88 min) were analyzed at 130°C. 4-Isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 16.41 and 16.63 min), 6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 17.6 min), (4R,7S)-7-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 12.71 min), and (4S,7R)-7-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (rt = 12.56) were analyzed at 140°C. δ-Valerolactone (rt = 12.2 min), ethyl acetate (rt = 4.1 min), ethyl caproate (rt = 5.2 min), and ethyl-6-hydroxyhexanoate (rt = 12.2 min) were analyzed at oven temperatures of 120, 60, 110, and 170°C, respectively.

The N terminus of purified MLH was determined by Edman degradation at the Protein Sequencing Facility Leiden, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Sylvius Laboratory, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Gene cloning.

Two degenerated primers were designed for application in PCR. Primer N (GCIACNGAYACIGCNAGRGC) was deduced from the amino acid sequence ATDTARA, and primer C (AARTCRTCDATNGTNGCRTC) was the reversed complement of the sequence encoding amino acids DATIDDF. Total DNA of R. erythropolis DCL14 was isolated according to the method of Barbirato et al. (2) and used as the template in a touchdown PCR assay with Super Taq polymerase (HT Biotechnology Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The annealing temperature of the reaction was decreased 1°C every second cycle from 56 to 53°C and every fourth cycle from 53 to 50°C, at which temperature 15 cycles were carried out. An amplified fragment of the expected size was cloned into a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.), and its sequence was determined.

Total DNA of R. erythropolis DCL14 was digested with PstI and size separated on an agarose gel. Fragments of about 6.0 kb were isolated from the gel using the QiaexII gel extraction kit from Qiagen (Westburg, The Netherlands) and ligated in the corresponding site of the cloning vector pUC19. This minilibrary was plated in Escherichia coli DH5α. Resulting colonies were transferred to nitrocellulose filters and hybridized to a PCR digoxigenin-labeled probe (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) amplified from primers N and C and the PCR clone as the template. Positive colonies were rescreened, and a resulting positive one was selected for construction of a restriction map and sequence analysis.

Standard methods were used for DNA manipulation and colony filter hybridization (17). Sequencing was performed with a Taq DYE terminator cycle sequencing kit and a dGTP BigDye Terminator ready reaction kit (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). Protein sequences were screened against database sequence libraries using FASTA and BLAST.

Sources of chemicals.

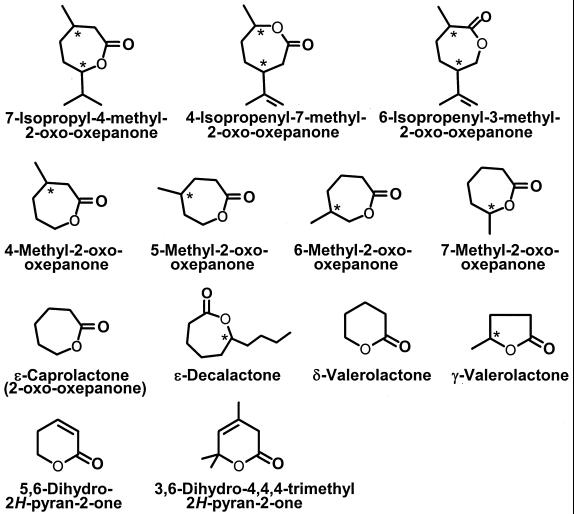

In this paper, the sequence rule of Cahn-Ingold-Prelog is used to differentiate between the stereochemistries of the monoterpene stereoisomers. The carbon atom numbering is based on the standard carbon atom numbering of limonene. For the structures of the lactones used, see Fig. 2. ɛ-Caprolactone was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo., and (4R)-limonene was from Acros Organics, Den Bosch, The Netherlands. 6-Hydroxyhexanoate was prepared from ɛ-caprolactone by chemical hydrolysis according to a modified procedure as described previously (5). A 10 mM solution of ɛ-caprolactone in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) was incubated at 60°C for 16 h. The solution was cooled, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 by addition of HCl. This solution contained no residual lactone when assayed, and the mass spectrum (MS) of the product was identical to that reported previously (32).

FIG. 2.

Lactones tested as substrates for MLH.

(4S,7R)- and (4R,7S)-7-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone were synthesized from (1S,4R)- and (1R,4S)-menthone, respectively, by oxidation with peracetate (18). To a solution of 100 μl of menthone in 0.5 ml of acetic acid containing 0.03 g of Na-acetate (anhydrous) was added 200 μl of 32% peracetic acid. The slurry was stirred vigorously for 36 h at room temperature. Subsequently, 10 ml of water was added to the reaction mixture, and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 7 with sodium hydroxide. This mixture was extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated to dryness with a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. For 7-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 170 [M+] (1), 152 (1), 141 (1), 127 (83), 99 (100), 81 (88), 69 (64), 55 (49), 41 (35). 7-Methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone and 5-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone were synthesized in the same manner from 2-methylcyclohexanone and 4-methylcyclohexanone, respectively, except that the reaction times were 24 h and 7 days, respectively. For 7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 128 [M+] (1), 113 (2), 87 (73), 68 (8), 55 (100), 41 (33); for 5-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 128 [M+] (7), 98 (19), 83 (11), 69 (59), 56 (100), 41 (40).

A mixture of 4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (37%) and 6-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (63%) was prepared from 3-methylcyclohexanone by peracetate oxidation, as described above, except that the reaction time was 7 days. For 4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 128 [M+] (11), 98 (100), 80 (23), 69 (77), 55 (81), 41 (79); for 6-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 128 [M+] (6), 99 (36), 83 (10), 69 (100), 55 (75), 42 (83).

A mixture of (4R)-4-isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone and (6R)-6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone was synthesized from (4R)-dihydrocarvone, by purified BVMO from R. erythropolis DCL14 (27). The reaction mixture, containing 15 mM NADPH, 50 mM glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 9.5), 1.25 mM dihydrocarvone, and 0.038 U of purified monocyclic monoterpene ketone monooxygenase per ml (27), was incubated at 30°C for 1 h. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was extracted three times with an equal volume of ethyl acetate. The organic layers were combined, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated to dryness with a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. The lactones thus formed were a mixture of 4-isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (79%) and 6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone (21%). For 4-isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 168 [M+] (3), 153 (3), 138 (16), 125 (17), 110 (71), 95 (39), 81 (27), 68 (100), 55 (24), 41 (43); for 6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone, MS data were as follows: m/z 168 [M+] (7), 153 (7), 139 (16), 125 (11), 108 (80), 93 (37), 81 (37), 67 (100), 55 (43), 41 (55). All other chemicals were of the highest purity commercially available.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence containing the mlhA and mlhB genes has been deposited in the EMBL database under accession no. AJ292535.

RESULTS

Induction of MLH activity in R. erythropolis.

R. erythropolis DCL14 is able to grow on a variety of monocyclic monoterpenes. During growth on limonene, a lactone-hydrolyzing activity which was not involved in limonene degradation was measured (25). To study this MLH in more detail, its activity was measured in cell extracts from R. erythropolis grown on different carbon sources (Table 1). Results show that growth on limonene, oxygenated limonene derivatives, or cyclohexanol resulted in an 80- to 800-fold increase in MLH activity over that of cells grown on succinate or ethanol. Remarkably, the (4R)-stereoisomers of both limonene and carveol were better inducers than the respective (4S)-stereoisomers. Although ɛ-caprolactone is a substrate for MLH, it is not a very effective inducer of enzymatic activity. This might be due to its polar structure, which prevents the compound from passing the cell membrane.

TABLE 1.

MLH activity in cell extracts of R. erythropolis DCL14 grown in batch cultures on various carbon sources

| Growth substrate | Sp act (μmol min−1 mg of protein−1)a |

|---|---|

| (4R)-Limonene | 14 |

| (4S)-Limonene | 6.1 |

| (4R)-Limonene-1,2-diolb | 3.4 |

| (4S)-Carveolb | 9.2 |

| (4R)-Carveol | 19 |

| (4R)-Dihydrocarveolb | 14 |

| (1R,3R,4S)-Menthol | 12 |

| (1R,3R,4S)-Isopulegol | 9.7 |

| Cyclohexanol | 8.8 |

| ɛ-Caprolactone | 0.80 |

| Succinate | 0.040 |

| Ethanol | 0.025 |

Activity with ɛ-caprolactone.

Diastereomeric mixture.

Purification of MLH.

MLH was isolated from (4R)-limonene-grown cells. The purification scheme for this enzyme is presented in Table 2. MLH was purified 26-fold with an overall yield of 26%. The absorption spectrum of this colorless protein did not give any indications for the presence of a prosthetic group. MLH could be stored at −20°C for 6 months, without loss of activity.

TABLE 2.

Purification of MLH from (4R)-limonene-grown cells of R. erythropolis DCL14

| Purification step | Total protein (mg) | Sp act (μmol min−1 mg of protein−1)a | Purification (fold) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 300 | 5.6 | 1 | 100 |

| Gel filtration | 130 | 9.9 | 1.8 | 78 |

| Hydroxyapatite | 32 | 25 | 4.5 | 48 |

| Anion exchange | 6.5 | 110 | 20 | 43 |

| Mono Q | 3.0 | 145 | 26 | 26 |

Activity with ɛ-caprolactone.

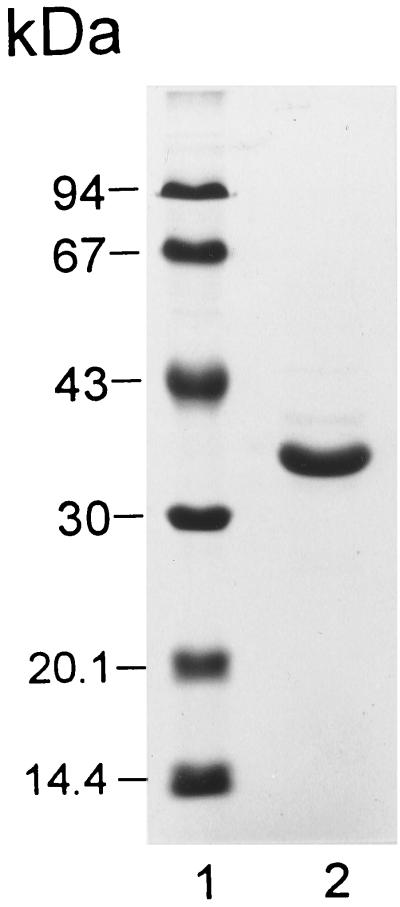

SDS-PAGE of the purified enzyme revealed one distinct band, corresponding to a protein with a molecular mass of 35 kDa (Fig. 3). Gel filtration revealed that the molecular mass of the native enzyme is also 35 kDa, indicating that MLH is a monomer.

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of MLH from R. erythropolis DCL14. Lane 1; molecular mass markers; lane 2; 15 μg of MLH.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of MLH was determined to be Ser-Ala-Thr-Asp-Thr-Ala-Arg-Ala-Lys-Glu-Leu-Leu-Ala-Ser-Leu-Val-Ser-Met-Pro-Asp-Ala-Thr-Ile-Asp-Asp- Phe-Arg-Ala-Leu-Tyr-Glu-Gln-Val-(Asp?)-Ala-Thr-Phe-Glu-Leu-Pro-(Asp?)-Asp-Ala-Gln-Val.

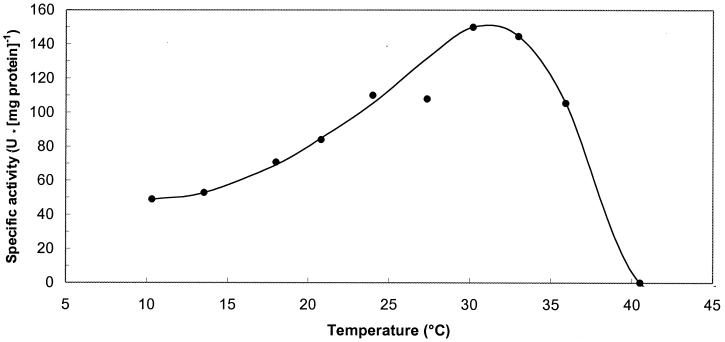

Biochemical characteristics of MLH. (i) Temperature and pH optimum.

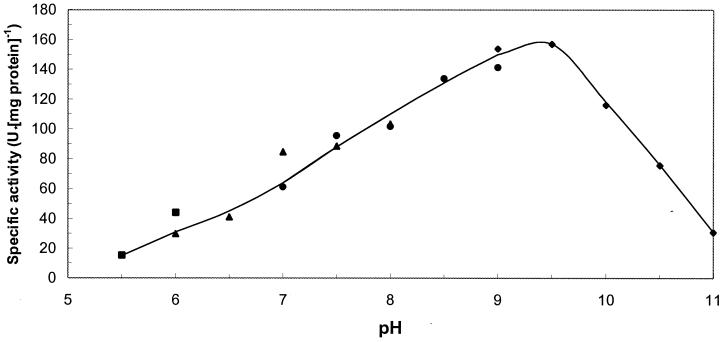

Under the conditions of the standard enzyme assay, MLH has a relatively low temperature optimum of 30°C. Above 40°C, the enzyme is readily inactivated (Fig. 4). MLH has a quite broad pH optimum, peaking around pH 9.5 (Fig. 5).

FIG. 4.

Effect of temperature on the MLH activity. The specific activity was determined with ɛ-caprolactone in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 9.0.

FIG. 5.

Effect of pH on the MLH activity. The specific activity was determined with ɛ-caprolactone at 30°C. ▪, 50 mM citrate buffer; ▴, 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer; ●, 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer; ♦, 50 mM glycine-NaOH buffer.

(ii) Inhibitors and metal ions.

A variety of enzyme inhibitors was tested for their ability to inhibit MLH activity (Table 3). The thiol reagent iodoacetate did not inhibit the enzymatic activity, nor did dithiothreitol or MgCl2. p-Chloromercuribenzoate, the carbonyl reagent phenylhydrazine, and the chelating agents α,α′-dipyridyl and EDTA inhibited the activity slightly, whereas the imidazole-modifying compound 2-bromo-4′-nitroacetophenone strongly inhibited MLH activity. Also, SDS, HgCl2, and CoCl2 were strong inhibitors of the enzyme (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effect of inhibitors and (metal) ions on MLH activity

| Effector | Concn (mM) | Relative activitya (%) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 100 | |

| 2-Bromo-4′-nitroacetophenone | 1 | 16 |

| Phenylhydrazine | 1 | 83 |

| α,α′-Dipyridyl | 1 | 45 |

| EDTA | 10 | 84 |

| SDS | 1 | 22 |

| Dithiothreitol | 1 | 100 |

| Iodoacetate | 1 | 100 |

| p-Chloromercuribenzoate | 0.1 | 74 |

| HgCl2 | 0.1 | 5 |

| CoCl2 | 1 | 29 |

| MnCl2 | 1 | 63 |

| CaCl2 | 1 | 73 |

| MgCl2 | 1 | 100 |

100% = activity with ɛ-caprolactone.

(iii) Substrate preference.

The ɛ-caprolactone hydrolysis product was identified as 6-hydroxyhexanoate based on its MS and retention time after chiral GC. Unfortunately, very few ɛ-lactones are commercially available, and therefore we were not able to determine the substrate preference of MLH very extensively. Among the lactones tested (Fig. 2 and Table 4), ɛ-caprolactone (4R)-4-isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone and (6R)-6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone were also good substrates for the enzyme. These lactone derivatives of dihydrocarvone (28) showed a higher relative activity than did the lactone derivative of menthone, 7-isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone. Possibly, the position of the isoprop(en)yl group with respect to the ester influences the interaction between enzyme and substrate. Also, ethyl caproate was a good substrate for the enzyme, indicating that MLH is an esterase with a preference for lactones (internal cyclic esters). Using 6-hydroxyhexanoate as the substrate, we have not been able to detect the reverse reaction (i.e., formation of the lactone) at pH values between 6.0. and 9.0. The enantiomers of 4-, 5-, 6-, and 7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone were converted at equal rates, suggesting that MLH is not stereoselective.

TABLE 4.

Substrate preference of MLH from R. erythropolis DCL14

| Substrate | Relative activitya (%) |

|---|---|

| ɛ-Caprolactone | 100 |

| (4R)-4-Isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanonebc | 82 |

| (6R)-6-Isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanonebc | 34 |

| (4S,7R)-7-Isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone | 1.4 |

| (4R,7S)-7-Isopropyl-4-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone | 0.6 |

| 4-Methyl-2-oxo-oxepanonede | 0.5 |

| 5-Methyl-2-oxo-oxepanonee | 0.7 |

| 6-Methyl-2-oxo-oxepanonede | 1.3 |

| 7-Methyl-2-oxo-oxepanonee | 8.1 |

| ɛ-Decalactonee | <1 |

| δ-Valerolactone | 9.7 |

| γ-Valerolactonee | <1 |

| Ethyl acetate | 1.9 |

| Ethyl caproate | 23 |

| Ethyl-6-hydroxyhexanoate | 0.9 |

| 3,6-Dihydro-4,6,6-trimethyl-2H-pyran-2-one | <1 |

| 5,6-Dihydro-2H-pyran-2-one | <1 |

100% = activity with ɛ-caprolactone.

Diastereomeric mixture.

Determined in isomeric mixture of 4-isopropenyl-7-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone and 6-isopropenyl-3-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone.

Determined in isomeric mixture of 4- and 6-methyl-2-oxo-oxepanone.

Racemic mixture.

Cloning and characterization of the MLH-encoding gene.

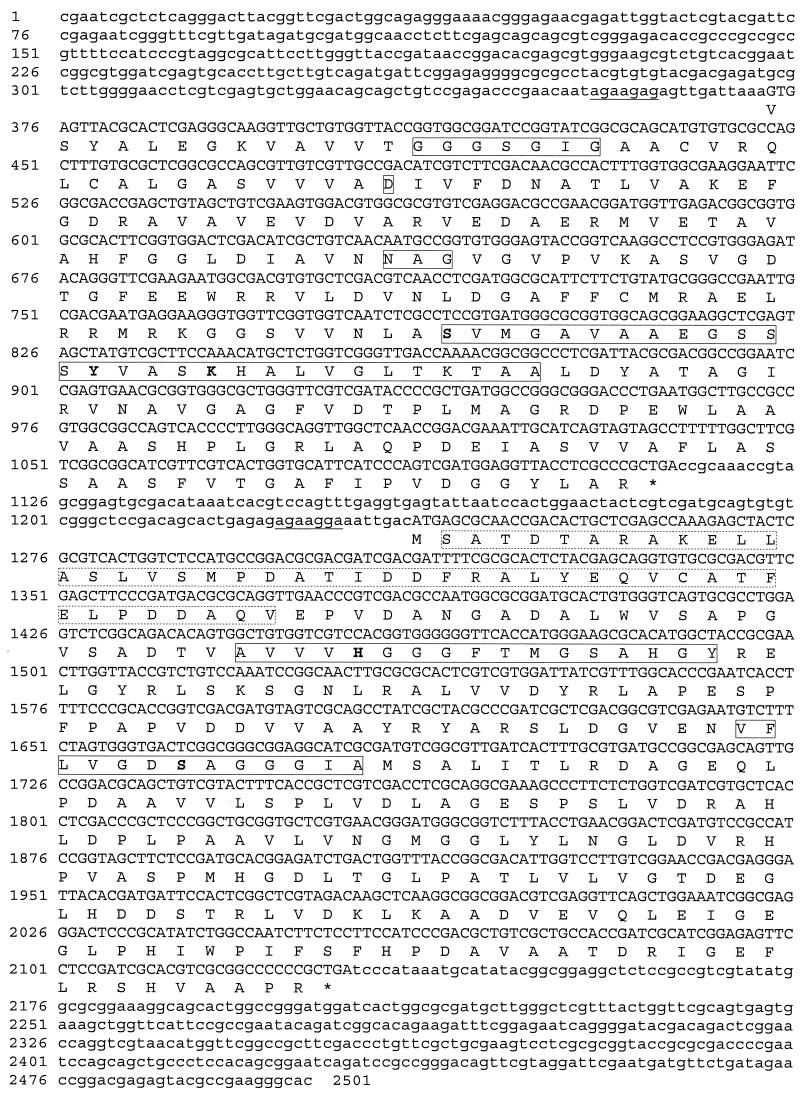

Two primers, deduced from the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified MLH, generated a fragment of the expected size in a PCR assay (about 75 bp). The sequence of this cloned PCR fragment corresponded to the amino acids ATDTARAKELLASLVSMPDATIDDF, which exactly matched part of the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified enzyme. Southern blot analysis of total DNA of R. erythropolis DCL14 digested with PstI showed a hybridizing fragment of about 6.0 kb when probed with the 75-bp PCR fragment. PstI-digested total DNA of this size was isolated from the gel and used to construct a minilibrary of R. erythropolis DCL14, which was subsequently screened for positive clones using the 75-bp PCR fragment as the probe. Southern blot analysis of a positive clone, pMLH22, proved the presence of the sequence encoding the N terminus. Part of this 6.0-kb PstI fragment was sequenced by subcloning various restriction fragments and by primer walking. Two open reading frames (Fig. 6), designated mlhA and mlhB (mlh = monoterpene lactone hydrolysis), were identified, of which mlhB encoded the N-terminal amino acid sequence of the purified MLH (Fig. 6). Amino acid residue 35, however, although suggested to be an aspartic acid in the N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis, proved to be a cysteine. The mlhB sequence contained an 894-bp open reading frame that began with an ATG start codon and ended with a TGA stop codon. It encoded a 297-residue polypeptide that had a calculated molecular mass of 31,134 Da, which is in agreement with the size of 35 kDa for the purified enzyme as determined by SDS-PAGE. A comparison of the mlhB amino acid sequence with sequences in the EMBL data library revealed up to 43% similarity to hydrolases, esterases, and lipases. The highest degree of sequence similarity was found with an acetyl hydrolase of Streptomyces hygroscopicus (accession no. q01109; 43% similarity to mlhB) and an esterase of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (accession no. p18773; 42% similarity to mlhB). Both enzymes belong to the GDXG family of lipolytic enzymes (PROSITE: PDOC00903 [http://www.expasy.ch/prosite/]). Characteristic of the GDXG family are two consensus sequences, containing a histidine and a serine residue, respectively, as putative active-site residues. Both motifs are also present in mlhB (boxed in Fig. 6). In the first motif, 14 of the 17 amino acids were conserved; in the second motif, 11 of the 13 amino acids were conserved. The putative active-site residues are in boldface in Fig. 6.

FIG. 6.

Nucleotide sequence of the mlhA and mlhB genes and the deduced amino acid sequences. Putative Shine-Dalgarno boxes are underlined. The amino acid sequence in the dashed box was also determined from purified MLH. Boxed amino acid sequences are consensus sequences of the respective protein families. Amino acids in boldface are putative active-site residues. The sequence in the region of positions 2145 to 2383 may contain some sequence artifacts.

Structural organization of the mlhA and mlhB genes.

In front of the mlhB sequence, another open reading frame was found and designated mlhA. It encoded a 246-residue peptide (Fig. 6) with a calculated molecular mass of 25,026 Da. The primary structure showed up to 55% sequence similarity to a 2,5-dichloro-2,5-cyclohexadiene-1,4-diol dehydrogenase of Sphingomonas paucimobilis (accession no. P50197) and up to 54% sequence similarity to glucose-1-dehydrogenases (accession no. P10528 and P39483). These enzymes belong to the short-chain dehydrogenase reductase (SDR) family (PROSITE: PDOC00060 [http://www.expasy.ch/prosite/]). The SDR family signature was present in mlhA (boxed in Fig. 6) and contained a serine, tyrosine, and lysine (in boldface in Fig. 6) participating in the catalytic mechanism. Moreover, conserved features near the N terminus include (i) the GXXXGXG sequence; (ii) an aspartic residue, 18 residues downstream of GXXXGXG, and (iii) an NAG sequence, all involved in binding of NAD(P) (16, 30). These motifs are also boxed in Fig. 6. Based on the position of the GXXXGXG motif, which is commonly 11 to 15 residues downstream of the start codon (26) and a putative Shine-Dalgarno box (underlined in Fig. 6), a GTG for formylmethionine was assigned as the start codon. A TGA stop codon was identified 735 nucleotides downstream of the start codon. Both reading frames were preceded by a potential ribosomal binding site (underlined in Fig. 6). The mlhB sequence was followed by a region (positions 2145 to 2383, Fig. 6) the sequence of which was difficult to determine. Considering that this region may function as a terminator region, the presence of secondary structures may impede the sequence analysis. Using a sequence kit especially designed for sequencing secondary structures, sequence analysis was more successful; however, 100% accuracy could not be established.

DISCUSSION

This report describes the purification, characterization, and gene cloning of MLH from R. erythropolis DCL14. MLH is induced when R. erythropolis DCL14 is grown on monoterpenes (Table 1), reflecting its function in the monocyclic monoterpene degradation pathways of this bacterium (28). Monoterpenes are the largest class of plant secondary metabolites and are widely distributed in nature (8). Remarkably little is known about the microbial degradation of these compounds (20, 21), and only a very few enzymes and genes involved in microbial monoterpene degradation have been characterized (23).

Previously, ɛ-lactone hydrolases from A. calcoaceticus NCIMB 9871 and Nocardia globerula CL1 have been purified and characterized (3). These enzymes were involved in the cyclohexanol degradation pathways of these microorganisms. Both strains were unable to grow on monoterpenes as the sole source of carbon and energy (6), but MLH nevertheless shares several characteristics with the two ɛ-lactone hydrolases. All three enzymes have subunit masses of approximately 30 kDa, do not contain a prosthetic group, are preferentially active with ɛ-lactones, and have a broad pH spectrum. Moreover, they are unable to catalyze the reverse reaction, i.e., the lactonization of 6-hydroxyhexanoate (3). In contrast, MLH is a monomer while the ɛ-lactone hydrolases from A. calcoaceticus and N. globerula are dimers.

Gene cloning and sequencing classified MLH as a member of the GDXG family of lipolytic enzymes. This is a small family of enzymes comprising hydrolases of microbial and mammalian origin. Characteristic are two consensus patterns containing the catalytic histidine and serine residues (7). Both GDXG family signatures were conserved over 80% in MLH (boxed in Fig. 6). Notably, inhibition of MLH activity by 2-bromo-4′-nitroacetophenone suggests the presence of a catalytic histidine in the enzyme. So far, only seven enzymes, containing a perfect match with the two GDXG family signatures, have been identified as members of the GDXG family (PROSITE: PDOC00903 [http://www.expasy.ch/prosite/]). However, during sequence homology studies with mlhB, we identified several more hydrolases containing the (almost perfect) GDXG family signatures.

Only one other ɛ-lactone hydrolase gene was present in the databases. This caprolactone hydrolase-encoding gene from Arthrobacter oxidans (accession no. E02645) showed 43% similarity to mlhB and about 85% similarity to the GDXG family signatures. Unfortunately, this enzyme has been described only in the patent literature. Recently, Khalameyzer et al. (10) isolated an esterase-encoding gene (estF1) from Pseudomonas fluorescens DSM 50106 by using a nonspecific esterase assay. Remarkably, this enzyme catalyzed the hydrolysis of γ-, δ-, and ɛ-lactones more efficiently than the hydrolysis of linear esters. No similarity was observed between MLH and EstF1. Instead, EstF1 belongs to the α/β-hydrolase fold superfamily (PROSITE: PDOC00110 [http://www.expasy.ch/prosite/]).

In front of the mlhB gene, another open reading frame (mlhA) was found with sequence similarity to members of the SDR superfamily, comprising alcohol dehydrogenases and reductases. In the (dihydro)carveol degradation pathway of R. erythropolis DCL14, in which MLH is involved, (dihydro) carveol dehydrogenase and carvone reductase, both potentially belonging to the SDR superfamily, catalyze the first degradative steps (28). Anion-exchange experiments have revealed that, in cell extracts of limonene-grown cells, up to four different carveol dehydrogenases are present (25). Previously, we reported the characterization and gene cloning of dichlorophenol indophenol (DCPIP)-dependent carveol dehydrogenase from R. erythropolis DCL14, another member of the SDR superfamily (26). However, from enzyme induction studies and the localization of the gene, we concluded that this enzyme is mainly involved in the limonene degradation pathway of the microorganism (28). Considering that many genes of metabolic pathways are clustered in prokaryotes, mlhA possibly encodes one of the other three (dihydro)carveol dehydrogenases or carvone reductase.

Approximately 2 kb downstream of the mlhB gene, a partial open reading frame was identified (see the full sequence of the 6-kb PstI fragment in the EMBL database) that shows up to 68% similarity with acyl coenzyme A (CoA) dehydrogenases. These enzymes are involved in the β-oxidation pathway of fatty acid degradation. 3-Isopropenyl-6-oxoheptanoyl-CoA, the branched-chain fatty acid formed in the limonene and (dihydro)carveol degradation pathways of R. erythropolis DCL14 after ring opening, is degraded further via the β-oxidation pathway (25, 28). Since the acyl-CoA dehydrogenase-encoding gene is positioned close to the mlh genes, a role for this gene in monoterpene degradation in R. erythropolis DCL14 is suggested.

MLH did not show any stereoselectivity with the tested substrates, indicating that the enzyme itself is not a suitable biocatalyst for the production of optically pure lactones. However, using the mlhB sequence and the recently reported protocol for gene disruption in R. erythropolis (22), an MLH-deficient mutant of R. erythropolis DCL14 can be constructed, allowing the production of economically important lactones by the resident BVMO activity (27).

In conclusion, MLH from R. erythropolis DCL14 is a novel enzyme involved in the degradation of monoterpenes. It belongs to the GDXG family of lipolytic enzymes and is the first ɛ-lactone hydrolase that is both biochemically and genetically characterized.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant FAIR CT 98–3559 from the European Community.

We thank Martin de Wit for technical assistance and Tony van Kampen for performing the DNA sequence analysis. Rob Leer (TNO-Voeding, Zeist, The Netherlands) is acknowledged for help with the DNA sequence analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arthur M, Autissier D, Courvalin P. Analysis of the nucleotide sequence of the ereB gene encoding the erythromycin esterase type II. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4987–4999. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.12.4987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbirato F, Verdoes J C, de Bont J A M, van der Werf M J. The Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14 limonene-1,2-epoxide hydrolase gene encodes an enzyme belonging to a novel class of epoxide hydrolases. FEBS Lett. 1998;438:293–296. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett A P, Strang E J, Trudgill P W, Wong V T K. Purification and properties of ɛ-caprolactone hydrolase from Acinetobacter NCIB 9871 and Nocardia globerula CL1. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:161–168. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donoghue N A, Trudgill P W. The metabolism of cyclohexanol by Acinetobacter NCIB 9871. Eur J Biochem. 1975;60:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb20968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donoghue N A, Norris D B, Trudgill P W. The purification and properties of cyclohexanone oxygenase from Nocardia globerula CL1 and Acinetobacter NCIM 9871. Eur J Biochem. 1976;63:175–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feller G, Thiry M, Gerday C. Nucleotide sequence of the lipase gene lip2 from the antarctic psychrotroph Moraxella TA144 and site-specific mutagenesis of the conserved serine and histidine residues. DNA Cell Biol. 1991;10:381–388. doi: 10.1089/dna.1991.10.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guenther A, Hewitt C N, Erickson D, Fall R, Geron C, Graedel T, Harley P, Klinger L, Lerdau M, McKay W A. A global model of natural volatile organic compound emissions. J Geophys Res. 1995;100:8873–8892. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hartmans S, Smits J P, van der Werf M J, Volkering F, de Bont J A M. Metabolism of styrene oxide and 2-phenylethanol in the styrene-degrading Xanthobacter strain 124X. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2850–2855. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.11.2850-2855.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalameyzer V, Fischer I, Bornscheuer U T, Altenbuchner J. Screening, nucleotide sequence, and biochemical characterization of an esterase from Pseudomonas fluorescens with high activity towards lactones. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:477–482. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.477-482.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lenn J M, Knowles C J. Production of optically active lactones using cycloalkanone oxygenases. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1994;16:964–969. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maga J A. Lactones in foods. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1976;8:1–56. doi: 10.1080/10408397609527216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masai E, Shinohara S, Hara H, Nishikawa S, Katayama Y, Fukuda M. Genetic and biochemical characterization of a 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid hydrolase involved in the protocatechuate 4,5-cleavage pathway of Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:55–62. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.55-62.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merino M T, Humanes L, Roldán J M, Diez J, López-Ruiz A. Production of limonoate A-ring lactone by immobilized limonin d-ring lactone hydrolase. Biotechnol Lett. 1996;18:1175–1180. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossmann G M, Moras D, Olsen K W. Chemical and biological evolution of a nucleotide-binding protein. Nature. 1974;250:194–199. doi: 10.1038/250194a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sauers R R, Ahearn G P. The importance of steric effects in the Baeyer-Villiger oxidation. J Am Chem Soc. 1961;83:2759–2762. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlömann M. Evolution of chlorocatechol catabolic pathways. Conclusions to be drawn from comparisons of lactone hydrolases. Biodegradation. 1994;5:301–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00696467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trudgill P W. Terpenoid metabolism by Pseudomonas. In: Sokatch J R, editor. The bacteria, a treatise on structure and function. X. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press, Inc.; 1986. pp. 483–525. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trudgill P W. Microbial metabolism and transformation of selected monoterpenes. In: Rattledge C, editor. Biochemistry of microbial degradation. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 33–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van der Geize R, Hessels G I, van Gerwen R, Vrijbloed J W, van der Meijden P, Dijkhuizen L. Targeted disruption of the kstD gene encoding a 3-ketosteroid Δ1-dehydrogenase isoenzyme of Rhodococcus erythropolis strain SQ1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2029–2036. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.2029-2036.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Werf M J, de Bont J A M, Leak D J. Opportunities in microbial biotransformation of monoterpenes. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 1997;55:147–177. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van der Werf M J, Overkamp K, de Bont J A M. Limonene-1,2-epoxide hydrolase from Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14 belongs to a novel class of epoxide hydrolases. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5052–5057. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5052-5057.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van der Werf M J, Swarts H J, de Bont J A M. Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14 contains a novel degradation pathway for limonene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2092–2102. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.2092-2102.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van der Werf M J, van der Ven C, Barbirato F, Eppink M H M, de Bont J A M, van Berkel W J H. Stereoselective carveol dehydrogenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14. A novel nicotinoprotein belonging to the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26296–26304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Werf M J. Purification and characterization of a Baeyer-Villiger mono-oxygenase from Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14 involved in three different monocyclic monoterpene degradation pathways. Biochem J. 2000;347:693–701. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3470693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Werf M J, Boot A M. Metabolism of carveol and dihydrocarveol in Rhodococcus erythropolis DCL14. Microbiology. 2000;146:1129–1141. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-5-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welsh F W, Murray W D, Williams R E. Microbiological and enzymatic production of flavor and fragrance chemicals. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1989;9:105–169. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wierenga R K, Terpstra P, Hol W G J. Prediction of the occurrence of the ADP-binding fold in proteins, using an amino acid sequence fingerprint. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:101–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willets A. Structural studies and synthetic applications of Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenases. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:55–62. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)84204-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams D R, Trudgill P W. Ring cleavage reactions in the metabolism of (−)-menthol and (−)-menthone by a Corynebacterium sp. Microbiology. 1994;140:611–616. [Google Scholar]