Abstract

BRAF and MEK inhibitors are standard of care for BRAF V600E/K mutated melanoma, but the benefit of BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors for non-standard BRAF alterations for melanoma and other cancers is unclear. Patients with diverse malignancies whose cancers had undergone next generation sequencing were screened for BRAF alterations. Demographics, treatment with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors, clinical response, progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were determined from review of the electronic medical record for standard BRAF V600E/K versus non-standard BRAF-altered patients. A total of 213 patients with BRAF alterations (87 with non-standard alterations) were identified; OS from diagnosis was significantly worse with non-standard BRAF versus standard alterations, regardless of therapy (hazard ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.58 (0.38–0.88) p=0.01). Overall, 45 patients received BRAF/MEK-directed therapy (8 with non-standard alterations); there were no significant differences in clinical benefit rate (stable disease≥6 months/partial/complete response (74% versus 63%) (p=0.39) or progression-free survival (p=0.24) (BRAF V600E/K versus others). In conclusion, patients with non-standard versus standard BRAF alterations (BRAF V600E/K) have a worse prognosis with shorter survival from diagnosis. Even so, 63% of patients with non-standard BRAF alterations achieved clinical benefit with BRAF/MEK inhibitors. Larger prospective studies are warranted in order to better understand the prognostic versus predictive implication of standard versus non-standard BRAF alterations.

Keywords: MEK inhibitor, BRAF inhibitor, BRAF alteration

BACKGROUND

BRAF is a serine/threonine kinase in the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which is important for cell growth and apoptosis. BRAF alterations are found in around 15% of cancers and the prevalence varies based on tumor type. BRAF mutations occur in 40–60% of melanomas, 5–15% of colorectal cancers, and 3% of lung cancers (1–4). Fusions are seen in 4–8% of melanomas (5) and 70% of pilocytic astrocytomas (6) while amplifications are seen in 30% of basal-like breast cancers (4,7). BRAF V600E accounts for 70–90% of the mutations (8). In BRAF-mutated melanoma, BRAF V600K is present in 7–19% of cases (4,8). Other BRAF-activating mutations are rare and occur at rates of less than 1% each (4,8).

MEK is downstream of BRAF and thus combination therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors is frequently used for BRAF V600E or V600K melanoma to improve responses and limit resistance (9). Dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy for metastatic melanoma yielded a 19% progression-free survival and 34% overall survival at 5 years for previously untreated patients (10). Encorafenib/binimetinib (11) and vemurafenib/cobimetinib (12) are alternative combination BRAF/MEK inhibiting therapies approved for metastatic cutaneous melanoma.

There has been evidence suggesting a benefit for vemurafenib in cancers other than melanoma harboring BRAF V600 mutations (13,14). However, the utility of BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors for non-standard BRAF alterations remains unclear. We reviewed our patient population at the University of California San Diego Moores Center for Personalized Cancer Therapy to compare patients with standard and non-standard alterations to determine if there were differences in outcomes and to evaluate responsiveness when treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors.

METHODS

This is a study of patients enrolled in the University of California San Diego Study (UCSD) Personalized Cancer Therapy to Determine Response and Toxicity study (UCSD-PREDICT) (NCT02478931), which encompasses an institutional review board (IRB)-approved observational cohort study at UCSD designed to learn more about personalized cancer therapy, including dosing, response to treatment, and side effects. Informed written consent was obtained from each subject. This study was performed in accordance with the UCSD IRB guidelines for data analysis and for any investigational treatments for which patients gave consent. The study methodologies conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and treatments:

A database of patients was generated from consecutive patients with FoundationOne molecular profiling results from November 2012 through July 2019. Patients with solid tumors and pathogenic BRAF alterations were included in the study. The electronic medical record was reviewed to determine patients who had received BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors (trametinib, cobimetinib, binimetinib, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, encorafenib). Review of clinical notes and imaging was used to determine overall survival (OS) from date of diagnosis and start of BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment, progression-free survival (PFS) from start of treatment, time to metastatic disease from date of diagnosis, and clinical response. Where there were discrepancies between radiology reports and physician notes, the documented physician assessment was prioritized for clinical response and progression. Patients who switched therapies prior to progression, went for curative surgical resection, or were lost to follow-up without progression were censored at date of last imaging. If patients did not have imaging assessment following initiation of therapy, they were excluded from the analysis. For patients who had more than one course of BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors, the first exposure was used for the analysis.

Next generation sequencing:

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor samples were previously sent to Foundation Medicine a clinical laboratory improvement amendments certified laboratory (CLIA) and analyzed using the FoundationOne next generation sequencing assay as previously described (15). For the included patients, the utilized gene panels varied from 182 to 347, but all panels included BRAF. Typical median depth of coverage is greater than 500X. This test can detect base substitutions, insertions and deletions (indels), copy number alterations (CNAs) and rearrangements using a routine tissue sample (including core or fine needle biopsies).

Outcome and statistics:

Differences in gender, disease, line of therapy, and drug were determined using Fisher’s exact test. Clinical benefit from BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors was stratified by stable disease (SD) <6 months and progressive disease (PD) versus SD ≥6 months/partial response (PR)/complete response (CR) and were compared with Fischer’s exact test. Patients with SD who were censored prior to 6 months of therapy were excluded from the clinical benefit analysis. Progression-free survival (PFS), time to metastatic disease, and overall survival (OS) from the start of treatment with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors was compared between patients with standard BRAF mutations and non-standard alterations using the log-rank test (Kaplan-Meier analysis) and Cox proportional hazards regression. OS and time to metastatic disease from date of diagnosis was compared between patients with standard BRAF mutations and non-standard alterations using the log-rank test (Kaplan-Meier analysis) and Cox proportional hazards regression. Patients who had not progressed at the time of last follow-up were censored at the date of last imaging, while patients who had not died at last follow-up were censored at that date. All statistical analyses were verified by our biostatistician (DAB). SAS v. 9.4 was used and p-values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics:

Overall, 213 patients were identified who had the requisite NGS tissue testing positive for BRAF mutations, fusions, or amplifications. The most common cancers in the standard BRAF alteration group were melanoma (N=54), thyroid cancer (N=24), and colorectal cancer (N=17). The most common cancers in the non-standard BRAF alteration group were melanoma (N=30) and colorectal cancer (N=9). Of the 213 patients with BRAF alterations, 169 patients either did not receive BRAF/MEK directed therapy or had insufficient follow-up to evaluate response to therapy. A total of 45 patients with BRAF alterations received BRAF and/or MEK directed therapy and had adequate follow-up to evaluate for response. The consort diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Consort diagram for the study. Only patients included in the PREDICT protocol were assessable for response.

Patient characteristics for individuals receiving BRAF/MEK directed therapy are depicted in Table 1. Thirty-seven patients had standard BRAF mutations (V600E or V600K) while 8 patients had other BRAF alterations. There were no significant differences between groups for disease type (melanoma vs. other; p=0.25), drugs (combination BRAF/MEK vs. BRAF or MEK; p=0.45), or line of therapy (first or second vs. third or greater; p=0.69). Age was significantly higher in the non-standard BRAF alteration group (p=0.007), and there were proportionally more women in the non-standard BRAF alteration group (p=0.03) who received BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor therapy.

Table 1:

Patient characteristics comparing patients with BRAF V600E or V600K to other BRAF alterations

| All patients with BRAF mutations (N=213) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF V600E/K (N=126) | Other BRAF Alterations (N=87) | p-value* | |

| Disease | |||

| Melanoma | 56 (44%) | 30 (34%) | 0.16 |

| Other | 70 (56%) | 57 (66%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 70 (56%) | 50 (57%) | 0.89 |

| Women | 56 (44%) | 37 (43%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 52.6 ± 15.2 | 58.8 ± 13.6 | 0.0026 |

| Patients with BRAF mutations not treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors (N = 143) | |||

| BRAF V600E/K (N=74) | Other BRAF Alterations (N=69) | p-value* | |

| Melanoma | 29 (39%) | 22 (32%) | 0.39 |

| Other | 45 (61%) | 47 (68%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 34 (46%) | 41 (51%) | 0.13 |

| Women | 40 (54%) | 28 (49%) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 54.7 ± 15.0 | 58.5 ± 13.1 | 0.11 |

| Patients with BRAF mutations treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors (N = 45) | |||

| BRAF V600E/K (N=37) | Other BRAF Alterations (N=8) | p-value* | |

| Melanoma | 23 (62%) | 3 (37%) | 0.25 |

| Other | 14 (38%) | 5 (63%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Men | 29 (78%) | 3 (38%) | 0.03 |

| Women | 8 (22%) | 5 (62%) | |

| Drug | |||

| BRAF + MEK inhibitor | 24 (65%) | 4 (50%) | 0.45 |

| BRAF or MEK inhibitor | 13 (35%) | 4 (50%) | |

| Line of Therapy for the BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor | |||

| 1–2 | 23 (62%) | 6 (75%) | 0.69 |

| 3 or more | 14 (38%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 47.2 ± 13.6 | 63.0 ± 16.9 | 0.007 |

p-value represents result of Fisher’s Exact test or equal-variance t-test comparison between variable and BRAF alteration status

Patient characteristics for all patients with BRAF alterations (n=213) (regardless of therapy) are also shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences with disease (p=0.16) or gender (p=0.89), but age was significantly higher in the non-standard BRAF alteration group (p=0.0026).

OS is longer (without an increased rate of SD≥6 months/PR/CR or increased PFS) in patients with standard versus non-standard BRAF inhibitors treated with BRAF/MEK inhibitors:

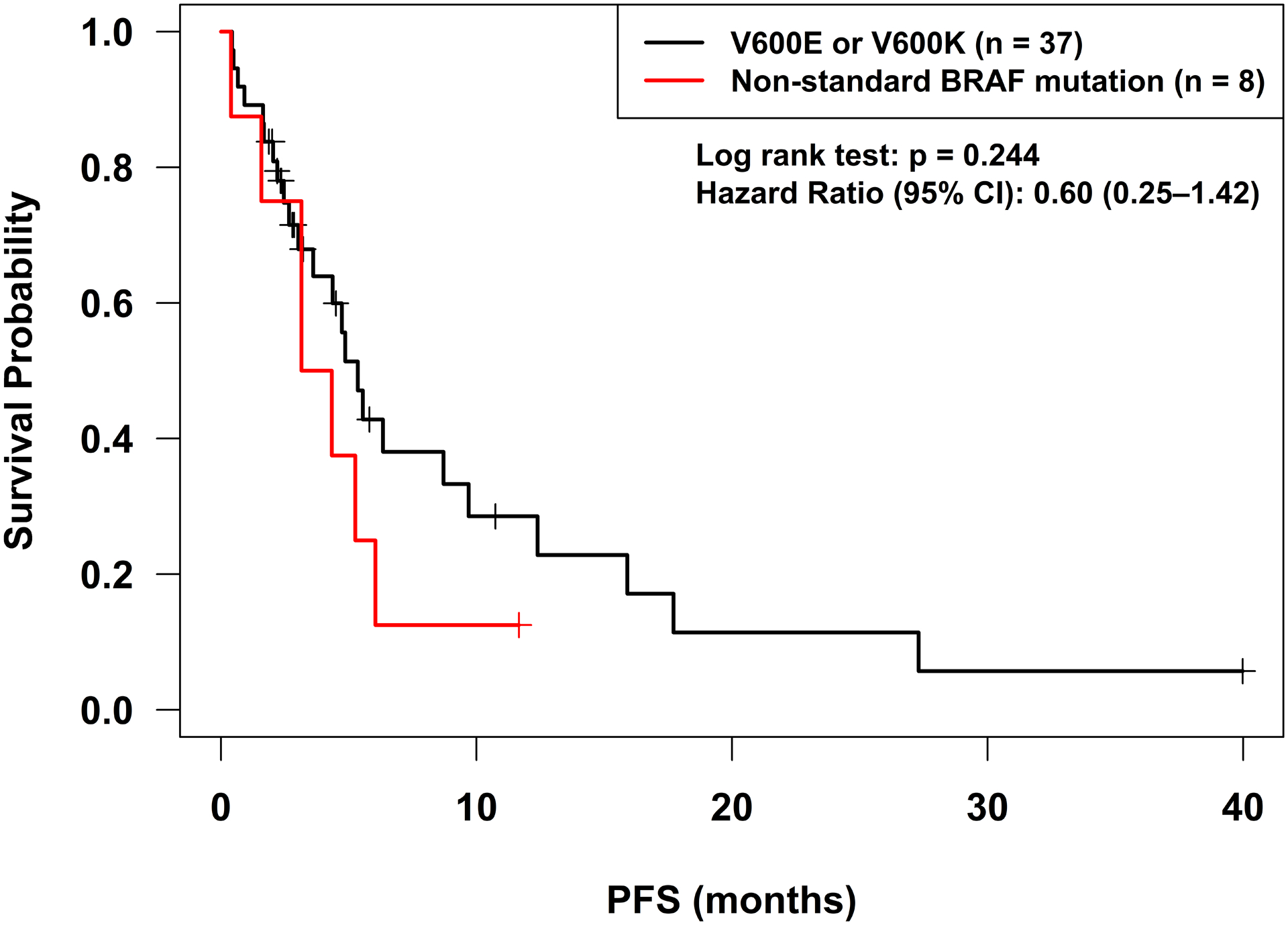

Clinical benefit was grouped by SD≥6 months/PR/CR vs. SD<6 months/PD for patients treated with BRAF or MEK inhibitors (Table 2). After BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor therapy, the patients with standard BRAF mutations (V600E or V600K) had a 74% rate of SD≥6 months/PR/CR (25 of 34 patients) as compared to a 63% SD≥6 months/PR/CR rate (5 of 8 patients) for non-standard BRAF alterations (p=0.39). Three patients were excluded from the analysis because their tumors were stable, but they had not yet completed six months of therapy. PFS was similar between patients with standard alterations as compared to non-standard alterations treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors (p=0.24; hazard ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.60 (0.25–1.42)) (Figure 2, Table 2).

Table 2:

Comparison of outcome in patients with standard BRAFV600E or V600K mutations versus those with non-standard BRAF alterations

| Patients with BRAF alterations (N = 213) | BRAF V600E or V600K | Non-standard BRAF alterations | Log-rank P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median OS from diagnosis in N = 213 patients with BRAF alterations | 174.2 months (N = 126) | 55.1 months (N = 87) | 0.01 |

| Median OS from diagnosis in N=143 patients with BRAF alterations not treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors | 191.1 (N=74) | 55.1 (N=69) | 0.01 |

| Median time to metastatic disease from diagnosis in N=213 patient with BRAF alterations | 11.8 (N=126) | 2.3 (N=87) | 0.12 |

| Median time to metastatic disease in N=143 patients with BRAF alterations not treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors | 13.7 (N=74) | 2.4 (N=69) | 0.08 |

| Median time to metastatic disease in N=45 patients with BRAF alterations treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors | 12.1 (N=37) | 0 (N=8) | 0.33 |

| Patients treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors (N = 45) | BRAF V600E or V600K (n=37)* | Non-standard BRAF alterations (N=8) | Log-rank P value |

| Clinical Benefit (SD≥6months /PR/CR) | 25 (74%) (N = 34*) | 5 (63%) (N = 8) | 0.39* |

| Median PFS from course 1 day 1 of BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor | 5.4 months (N =37) | 3.7 months (N =8) | 0.24 |

| Median OS from course 1 day 1 of BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor | 29.8 months (N =37) | 5.1 months (N =8) | 0.02 |

p=0.39 by Fisher’s exact test comparing SD≥6months /PR/CR in patients with standard BRAF V600E or V600K with those with non-standard alterations; 3 patients with stable disease who were censored at less than 6 months were excluded from the analysis

Abbreviations: CR=complete response, OS = overall survival; PR=partial response, SD=stable disease

Figure 2:

Progression-free survival for standard BRAF mutations (V600E and V600K) as compared to other BRAF alterations treated with BRAF or MEK inhibitors. Start date was course 1 day 1 of BRAF or MEK inhibitor therapy. There were no significant differences in progression-free survival found. Patients were censored if therapy was switched in the absence of progression at the date of the last set of scans. Patients who were lost to follow-up or underwent curative surgery were also censored at the date of the last set of scans. Patients who died without progression were censored at the date of death.

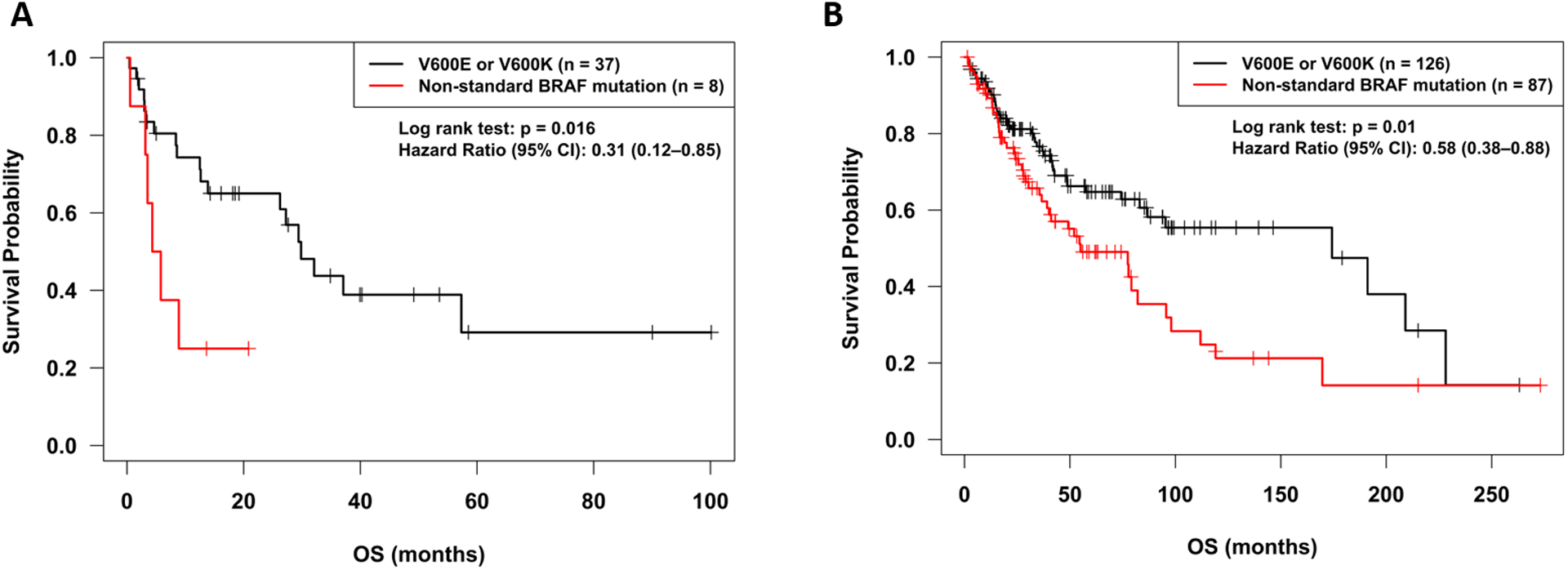

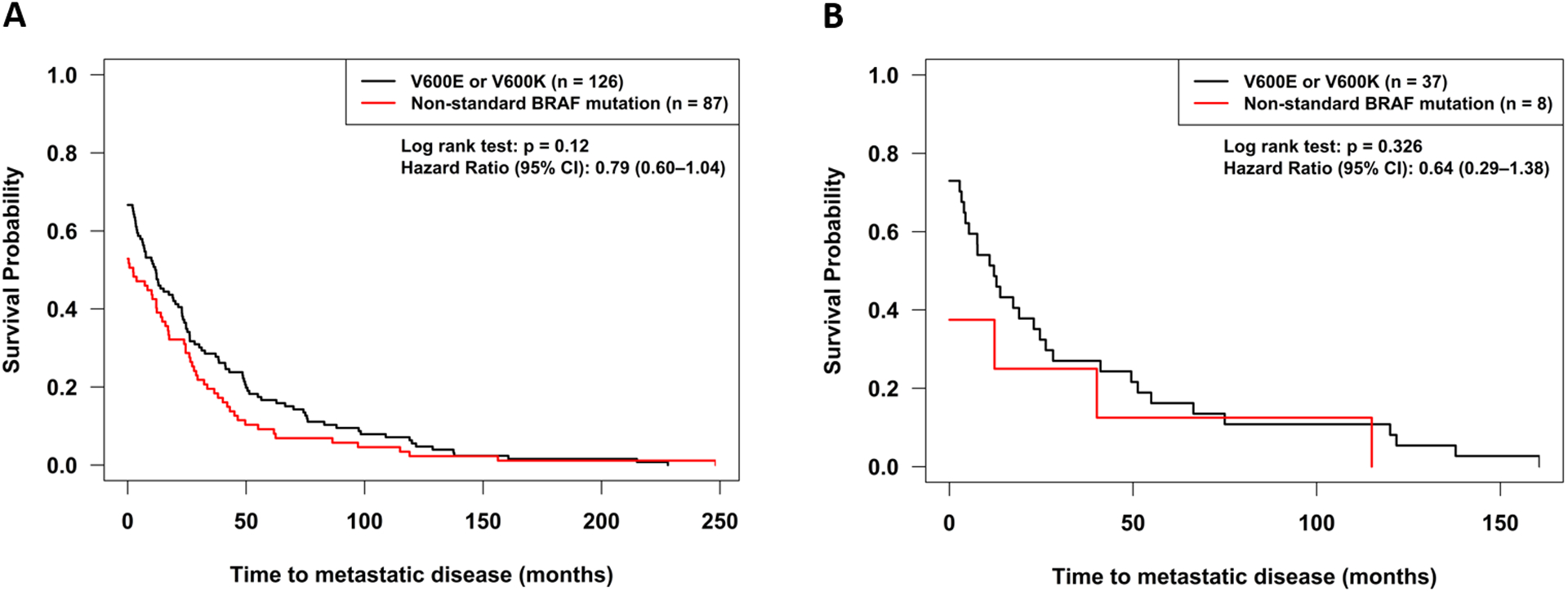

OS was significantly longer for patients with standard alterations as compared to non-standard alterations treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors (p=0.01; hazard ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.58 (0.38–0.85)) (Figure 3A, Table 2). Given that age and gender were significantly different between the BRAF standard and non-standard alteration groups, backward model selection was used in the Cox proportional hazards regression, and both dropped out as non-significant and were excluded from the final. Time to metastatic disease was not significantly different between patients with standard and non-standard BRAF alterations (p=0.33, Table 2, Figure 4B). Clinical details of the patients with non-standard BRAF alterations are shown in Table 3.

Figure 3:

Overall survival according to BRAF alteration status.

A. Overall survival for standard BRAF mutations (V600E and V600K) as compared to other BRAF alterations treated with BRAF or MEK inhibitors. Start date was course 1 day 1 of BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor therapy. Patients with standard alterations had significantly improved overall survival.

B. Overall survival from time of diagnosis for standard BRAF mutations (V600E and V600K) as compared to other BRAF alterations for all patients with BRAF alterations. Patients with unknown dates of death were censored at the last follow-up (office visit or phone call). Patients with standard BRAF alterations had significantly longer overall survival from diagnosis

Figure 4:

Time to metastatic disease from time of diagnosis for BRAF mutations (V600E and V600K) as compared to other BRAF alterations. Patient who did not develop metastatic disease were considered censored at the last follow-up (office visit or phone call) or at death. A. All patients with BRAF alterations, B. Patients treated with BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors.

Table 3:

Patients with non-standard BRAF alterations

| ID | Age | Gender | Diagnosis | BRAF alteration (Class) | Other Alterations | TMB | Drug | Line of Therapy | Best Response | PFS Months** | OS Months** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | F | colon cancer | D594G (III) | KIT D737N, APC R1399fs*9, BRIP1 I550fs*40, FLCN R477*, TP53 H179R | 9 | trametinib | 3+ | PR | 11.66+ | 13.63+ |

| 2 | 83 | M | lung adenocarcinoma | D594H (III), G466A (III) | EGFR exon 19 deletion, BAP1 loss, CDKN2A/B loss, RB1 splice site 2107–1_2113delGATTATGA | 3 | dabrafenib, trametinib | 2 | SD <6 months | 3.15 | 20.83+ |

| 3 | 40 | F | small bowel adenocarcinoma | D594N (III) | KRAS E63K, RAF1 S257L, SMAD4 R361H, W509*, SOX9 Q393fs*12, TP53 A86fs*38 | 4 | trametinib | 1 | PD | 1.58 | 3.52 |

| 4 | 84 | F | melanoma | G469A (II) | PTEN loss exons 3–9, CDKN2A/B loss, TERT promoter-124C>T | 18 | dabrafenib, trametinib | 3+ | PR | 4.34 | 4.34 |

| 5 | 66 | M | non-small cell lung cancer | K601E (II) | TP53 G154V, SPTA1 E1469fs*11 | N/A* | vemurafenib | 2 | PR | 5.26 | 5.78 |

| 6 | 79 | F | melanoma | N581S(III) | CDK4 amp, ERBB3 amp, MDM2 amp, TET2 splice site 4044+1G>T, T1895fs*13 | 8 | dabrafenib, trametinib | 2 | PD | 0.39 | 0.53 |

| 7 | 75 | F | pancreatic cancer | V600_K601>E (I***) | TP53 V218E | 4 | Trametinib | 2 | SD ≥ 6 months | 6.05 | 8.87 |

| 8 | 64 | M | melanoma | V600R (I) | FLT1 S287F, PTEN Q214fs*5, CDKN2A loss p16INK4a and p14ARF exons 2–3, TP53 E198K, LRP1B R295*, LRP1B R3186C | N/A* | dabrafenib, trametinib | 2 | PR | 3.15 | 3.15 |

N/A: tumor mutational burden was not available for these Foundation Medicine reports from 2014

+ indicates patient was censored prior to event occurrence

V600_K601>E found to constitutively activate the B-Raf kinase and the MAP kinase pathway, similar to the classical BRAF V600E mutation (35)

Abbreviations: F=female, M=male, OS=Overall Survival, PD=progressive disease, PFS=progression free survival, PR=partial response, SD=stable disease, TMB=tumor mutational burden (Mutations/Megabase), 3+=3 or more lines of therapy

Patients with standard versus non-standard BRAF alterations have a longer OS from diagnosis and trend to longer time to metastatic disease.

Overall survival from date of diagnosis was determined for all patients with BRAF alterations (n=213). OS was significantly different for patients with standard alterations as compared to non-standard alterations (p=0.01; hazard ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.58 (0.38–0.88)) (Figure 3B, Table 2). Given that age was significantly different between the BRAF standard and non-standard alteration groups, age was tested in the PFS and OS proportional hazards regression analysis and found to be non-significant (p=0.15), so was excluded from the final model. There was a high rate of censoring in both the standard alteration (63%) and non-standard alteration (49%) groups. Median time to metastatic disease was longer in patients with standard versus non-standard BRAF alterations 11.8 months (N=126 patients) versus 2.3 months (N=87 patients) but this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.12) (Table 2, Figure 4A).

Treatment after BRAF/MEK inhibitors included immunotherapy more commonly in patients with standard versus non-standard BRAF alterations.

Of the 8 patients with non-standard BRAF alterations treated with BRAF/MEK inhibitors, none received immunotherapy after the BRAF/MEK inhibitor; of the 37 patients with standard BRAF alterations who received BRAF/MEK inhibitors, 13 received immunotherapy (9 PD-1 checkpoint blockade; 3 high dose IL2; 1 with PD-1 checkpoint blockage and high dose IL2) after the BRAF/MEK inhibitor (and 7 of these patients achieved an objective response). However, the patients in the non-standard BRAF-altered group may not have received immunotherapy after BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment because their survival after progression on BRAF inhibitors was too short to initiate another therapy (median PFS = 3.7 months; median OS = 5.1 months).

DISCUSSION

Metastatic cancers harbor a diverse landscape of molecular alterations. Recent advances in precision medicine have suggested that a personalized, precision medicine approach of blocking multiple pathways of growth simultaneously can improve outcomes and limit resistance (16–21). Thus, understanding major drivers for cancer growth and how best to target alterations found in these pathways is important for cancer therapy. BRAF alterations are commonly seen in metastatic cancers (22) and targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors is standard of care for BRAF V600E or V600K mutations in metastatic melanoma. However, the applicability of these therapies to other BRAF alterations remains largely unknown. We evaluated patients at our institution with BRAF alterations who received BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors.

In patients receiving BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors, there were no significant differences in PFS or clinical response with standard vs. non-standard alterations; however, patients with non-standard alterations had significantly worse overall survival from time of BRAF/MEK treatment. This difference could not be accounted for by the age differences between the groups, line of therapy, disease type, or combination BRAF/MEK vs. single agent therapy. There was also a significant difference in overall survival between the standard and non-standard BRAF alteration groups from diagnosis with the non-standard group having a shorter survival (Table 2); time to metastatic disease was also shorter in the non-standard BRAF group, albeit it did not reach statistical significance. These data suggest that patients with standard BRAF V600E/K alterations may have a better prognosis than those with non-standard alterations.

Prior studies explored the efficacy of treatment with BRAF and MEK inhibitors for patients with non-standard BRAF alterations. A review of 32 patients in the NCI-MATCH study receiving trametinib for non-standard BRAF mutations or fusions had an overall survival of 5.7 months with one partial response seen. Trametinib was not felt to be effective for non-standard BRAF mutations or fusions (23). A separate study of 103 advanced melanoma patients compared outcomes with BRAF and/or MEK inhibition (24). Response rates were higher with non-V600 E/K BRAF alterations than non-V600 alterations (45% vs. 18%, p=0.009). Median PFS was 6.0 months for BRAF V600 alterations as compared to 2.6 months for non-V600 alteration, but was not statistically different (24). Another study evaluated patients with BRAF V600R mutations, which account for 3–7% of BRAF mutations in melanoma (25). A total of nine patients with V600R were treated with dabrafenib or vemurafenib with an 83% response rate suggesting that BRAF V600R melanoma patients could be effectively treated with BRAF inhibitors (25).

Our study included a variety of solid tumors with 4 of 8 patients achieving a partial response but a median PFS of 3.7 months when receiving BRAF and/or MEK inhibitors for non-standard alterations. Two melanoma patients received dabrafenib and trametinib, a non-small cell lung cancer patient received vemurafenib, and a colorectal cancer patient received trametinib. However, despite the 50% response rate, PFS (median = 3.7 months) and overall survival (median = 5.1 months) remained poor. In contrast, the median PFS and survival of our patients with BRAF V600E/K alterations treated with BRAF/MEK inhibitors was 5.4 and 29.8 months, respectively. The large difference in survival may have been due to the fact that patients with classic BRAF V600E/K alterations lived long enough to receive another treatment regimen—and that regimen was often checkpoint blockade (with its attendant more durable responses). Hence the poor prognostic implication of non-standard BRAF alterations may have impacted the survival of these patients directly as well as indirectly (by limiting their exposure to further treatments).

Prior studies suggested that overall survival may be worse for melanoma and colorectal cancer patients with BRAF alterations (26). However, BRAF codons 594 and 596 have been suggested to provide a more favorable prognosis in melanoma and colorectal cancer (27,28). Differences in outcomes between standard and non-standard alterations as a group had not been compared. In our population of 213 subjective with BRAF alterations, we found that non-standard alterations led to a significantly worse overall survival than standard alterations.

The nomenclature for BRAF mutations has been defined as the following: Class I BRAF V600E/K, Class II are constitutively active dimers (29), and Class III are kinase-dead (29). BRAF D549G is an example of a class III BRAF inactivating mutation. It has been suggested that these mutations can upregulate CRAF signaling (30,31) and activation of signaling is RAS dependent (29). This mutation was insensitive to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib in cell culture (29). We have a patient with colon cancer who harbored a D594G alteration and attained a partial response to trametinib. Thus, it is possible that downstream blockade with MEK inhibition may provide RAS inhibition and allow for responses in class III mutations. MEK inhibition with trametinib has previously been shown to inhibit the proliferation of cells in culture for Class III BRAF mutations due to amplified ERK signaling (29), however other patients receiving trametinib with Class 3 alterations had SD <6 months (1 patient) and PD (2 patients). ERK inhibition could theoretically improve responses for class III BRAF inactivating mutations. Preclinical data suggests that emerging SHP2/SOS1 inhibitors could be effective in patients harboring Ras-dependent class III BRAF mutations (32,33). Whereas type II B/CRAF inhibitors may be effective in patients harboring class II BRAF mutations (34).

Class II BRAF mutations have intermediate or high kinase activity with RAS independence. Cell culture studies demonstrated resistance to BRAF inhibitors, however it has been suggested the MEK inhibition may overcome resistance (29). One patient with a Class II mutation who was treated with dabrafenib and trametinib had a PR.

The current study was limited as it was retrospective and only included eight patients with non-standard BRAF alterations receiving BRAF and/or MEK treatment, thus it was difficult to distinguish differences in responses between individual drugs and Class II vs. III mutations. The small number of patients receiving BRAF and/or MEK therapy for non-standard alteration was likely driven by physician practice patterns. Other factors may have also influenced the analysis. For some melanoma patients, therapy was switched (often to immunotherapy) prior to progression due to physician preference, which led to censoring of the patients for the PFS analysis. The high degree of censoring for all patients with BRAF alterations also led to difficulty determining to what extent the differences found between the groups were representative of differing biology of the disease. The patient population was extremely heterogenous, but had many melanoma patients, thus it is unclear if the survival difference is universal across all tumor types or just for a few select cancers.

In conclusion, the current study found significant differences in overall survival between patients harboring malignancies bearing standard versus non-standard BRAF alterations, from the time of diagnosis, suggesting that non-standard BRAF alterations are associated with a poorer prognosis than standard (BRAF V600E/K) alterations. Despite the lower overall survival in patients with non-standard versus standard mutations treated with BRAF and/or MEK targeting therapies, 50% of patients with non-standard BRAF alterations achieved an objective response and 63% attained clinical benefit (SD≥6 months/PR/CR), suggesting that BRAF/MEK inhibitors are active in this subgroup. Larger prospective studies are needed to confirm the prognostic and predictive implications of standard BRAF V600E/K versus non-standard BRAF alterations in patients with cancer.

Acknowledgements/Funding:

This work was supported by the Joan and Irwin Jacobs philanthropic fund. This study was funded in part by the Joan and Irwin Jacobs philanthropic fund. Research reported in this publication was supported by a National Cancer Institute grant P30 CA023100 (S.M. Lippman) and by the National Institutes of Health, Grant TL1TR001443 (E.V. Capparelli). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures:

Dr. Kurzrock receives consultant fees from Actuate Therapeutics, X-Biotech and NeoMed, Roche,Pfizer and Merck, as well as research funds from Incyte, Genentech, Pfizer, Foundation Medicine, Guardant, Sequenom, Konica Minolta, and Merck Serono, speaker fees from Roche, and has an ownership interest in Curematch Inc and is Board member of CureMatch and CureMetrix Inc.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References:

- 1.Paik PK, Arcila ME, Fara M, Sima CS, Miller VA, Kris MG, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung adenocarcinomas harboring BRAF mutations. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2046–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pakneshan S, Salajegheh A, Smith RA, Lam AK. Clinicopathological relevance of BRAF mutations in human cancer. Pathology 2013;45:346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002;417:949–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turski ML, Vidwans SJ, Janku F, Garrido-Laguna I, Munoz J, Schwab R, et al. Genomically Driven Tumors and Actionability across Histologies: BRAF-Mutant Cancers as a Paradigm. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15:533–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross JS, Wang K, Chmielecki J, Gay L, Johnson A, Chudnovsky J, et al. The distribution of BRAF gene fusions in solid tumors and response to targeted therapy. Int J Cancer 2016;138:881–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones DT, Kocialkowski S, Liu L, Pearson DM, Backlund LM, Ichimura K, et al. Tandem duplication producing a novel oncogenic BRAF fusion gene defines the majority of pilocytic astrocytomas. Cancer Res 2008;68:8673–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancer Genome Atlas N Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2012;490:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, Massari F, MacLennan GT, Montironi R. Molecular testing for BRAF mutations to inform melanoma treatment decisions: a move toward precision medicine. Mod Pathol 2018;31:24–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eroglu Z, Ribas A. Combination therapy with BRAF and MEK inhibitors for melanoma: latest evidence and place in therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2016;8:48–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robert C, Grob JJ, Stroyakovskiy D, Karaszewska B, Hauschild A, Levchenko E, et al. Five-Year Outcomes with Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Metastatic Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381:626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dummer R, Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, Arance A, Mandala M, Liszkay G, et al. Encorafenib plus binimetinib versus vemurafenib or encorafenib in patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma (COLUMBUS): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, Atkinson V, Liszkay G, Maio M, et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1867–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyman DM, Puzanov I, Subbiah V, Faris JE, Chau I, Blay JY, et al. Vemurafenib in Multiple Nonmelanoma Cancers with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med 2015;373:726–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subbiah V, Puzanov I, Blay JY, Chau I, Lockhart AC, Raje NS, et al. Pan-Cancer Efficacy of Vemurafenib in BRAFV600- Mutant Non-Melanoma Cancers. Cancer Discov 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frampton GM, Fichtenholtz A, Otto GA, Wang K, Downing SR, He J, et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol 2013;31:1023–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sicklick JK, Kato S, Okamura R, Schwaederle M, Hahn ME, Williams CB, et al. Molecular profiling of cancer patients enables personalized combination therapy: the I-PREDICT study. Nat Med 2019; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodon J, Soria JC, Berger R, Miller WH, Rubin E, Kugel A, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic profiling expands precision cancer medicine: the WINTHER trial. Nat Med 2019;25:751–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwaederle M, Parker BA, Schwab RB, Daniels GA, Piccioni DE, Kesari S, et al. Precision Oncology: The UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center PREDICT Experience. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15:743–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsimberidou AM, Iskander NG, Hong DS, Wheler JJ, Falchook GS, Fu S, et al. Personalized medicine in a phase I clinical trials program: the MD Anderson Cancer Center initiative. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:6373–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsimberidou AM, Hong DS, Wheler JJ, Falchook GS, Janku F, Naing A, et al. Long-term overall survival and prognostic score predicting survival: the IMPACT study in precision medicine. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsimberidou AM, Fountzilas E, Nikanjam M, Kurzrock R. Review of precision cancer medicine: Evolution of the treatment paradigm. Cancer Treat Rev 2020;86:102019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janku F, Lee JJ, Tsimberidou AM, Hong DS, Naing A, Falchook GS, et al. PIK3CA mutations frequently coexist with RAS and BRAF mutations in patients with advanced cancers. PLoS One 2011;6:e22769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson DB, Zhao F, Noel M, Riely GJ, Mitchell EP, Wright JJ, et al. Trametinib Activity in Patients with Solid Tumors and Lymphomas Harboring BRAF Non-V600 Mutations or Fusions: Results from NCI-MATCH (EAY131). Clin Cancer Res 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menzer C, Menzies AM, Carlino MS, Reijers I, Groen EJ, Eigentler T, et al. Targeted Therapy in Advanced Melanoma With Rare BRAF Mutations. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:3142–3151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein O, Clements A, Menzies AM, O’Toole S, Kefford RF, Long GV. BRAF inhibitor activity in V600R metastatic melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2013;49:1073–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Safaee Ardekani G, Jafarnejad SM, Tan L, Saeedi A, Li G. The prognostic value of BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer and melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012;7:e47054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu X, Yan J, Dai J, Ma M, Tang H, Yu J, et al. Mutations in BRAF codons 594 and 596 predict good prognosis in melanoma. Oncol Lett 2017;14:3601–3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cremolini C, Di Bartolomeo M, Amatu A, Antoniotti C, Moretto R, Berenato R, et al. BRAF codons 594 and 596 mutations identify a new molecular subtype of metastatic colorectal cancer at favorable prognosis. Ann Oncol 2015;26:2092–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao Z, Yaeger R, Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, Tao A, Torres NM, Chang MT, et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature 2017;548:234–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cope NJ, Novak B, Liu Z, Cavallo M, Gunderwala AY, Connolly M, et al. Analyses of the oncogenic BRAF(D594G) variant reveal a kinase-independent function of BRAF in activating MAPK signaling. J Biol Chem 2020;295:2407–2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noeparast A, Teugels E, Giron P, Verschelden G, De Brakeleer S, Decoster L, et al. Non-V600 BRAF mutations recurrently found in lung cancer predict sensitivity to the combination of Trametinib and Dabrafenib. Oncotarget 2017;8:60094–60108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bracht JWP, Karachaliou N, Bivona T, Lanman RB, Faull I, Nagy RJ, et al. BRAF Mutations Classes I, II, and III in NSCLC Patients Included in the SLLIP Trial: The Need for a New Pre-Clinical Treatment Rationale. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann MH, Gmachl M, Ramharter J, Savarese F, Gerlach D, Marszalek JR, et al. BI-3406, a Potent and Selective SOS1-KRAS Interaction Inhibitor, Is Effective in KRAS-Driven Cancers through Combined MEK Inhibition. Cancer Discov 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monaco KA, Delach S, Yuan J, Mishina Y, Fordjour P, Labrot E, et al. LXH254, a potent and selective ARAF-sparing inhibitor of BRAF and CRAF for the treatment of MAPK-driven tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2020; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barollo S, Pezzani R, Cristiani A, Redaelli M, Zambonin L, Rubin B, et al. Prevalence, tumorigenic role, and biochemical implications of rare BRAF alterations. Thyroid 2014;24:809–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]