Abstract

Photosynthetic water oxidation is catalyzed by a manganese–calcium oxide cluster, which experiences five “S-states” during a light-driven reaction cycle. The unique “distorted chair”-like geometry of the Mn4CaO5(6) cluster shows structural flexibility that has been frequently proposed to involve “open” and “closed”-cubane forms from the S1 to S3 states. The isomers are interconvertible in the S1 and S2 states, while in the S3 state, the open-cubane structure is observed to dominate inThermosynechococcus elongatus (cyanobacteria) samples. In this work, using density functional theory calculations, we go beyond the S3+Yz state to the S3nYz• → S4+Yz step, and report for the first time that the reversible isomerism, which is suppressed in the S3+Yz state, is fully recovered in the ensuing S3nYz• state due to the proton release from a manganese-bound water ligand. The altered coordination strength of the manganese–ligand facilitates formation of the closed-cubane form, in a dynamic equilibrium with the open-cubane form. This tautomerism immediately preceding dioxygen formation may constitute the rate limiting step for O2 formation, and exert a significant influence on the water oxidation mechanism in photosystem II.

Introduction

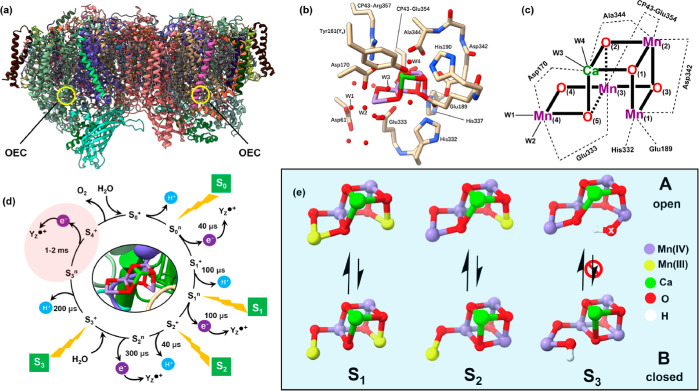

Photosystem II (PSII) is a metalloenzyme that catalyzes water splitting to molecular oxygen in cyanobacteria, algae, and plants. It evolved about 3 billion years ago at the level of ancient cyanobacteria (Figure 1a). The embedded “oxygen-evolving complex (OEC)”, composed of a Mn4CaO5 cluster surrounded by water and amino acid ligands (Figure 1b,c), acts as a highly efficient water oxidation catalyst. Due to charge separations in the reaction center of PSII, the OEC is initially stepwise oxidized during the cyclic catalysis, so that it attains four (meta)stable intermediates (S0, S1, S2, and S3) and one transient S4 state, the latter of which initiates O2 formation.1−10 Accounting also for proton release and charge of the Mn4CaO5(6) complex, the classical five-step “S-state cycle”11 can be refined to instead include nine intermediate states that are separated by kinetically distinguishable proton and electron transfer steps (Figure 1d).3,12−22

Figure 1.

(a) View of PSII dimer and the OEC location from Thermosynechococcus elongatus (PDB ID: 6W1O)38 (b) Mn4CaO5 cluster and its local surroundings in its dark-stable S1 state. (c) Sketch map of atom labeling and connectivity of the first coordination sphere ligands in the Mn4CaO5 cluster. (d) Extended S-state cycle including nine intermediates with sequence of proton and electron transfer and kinetics between transitions;3,13−15,17,21,22,70 the red phase is the main focus of this study. (e) Structural flexibility of the OEC cluster in the S1, S2, and S3 states, marked with the reversibility between open (A) and closed (B) cubane structures (for references, see the main text).

Structural polymorphism of the OEC has been proposed and experimentally observed, mainly by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, for some decades.1,4,18,23−30 More recently, the first detailed theoretically models were proposed for interpreting these findings.31,32 However, the proposed alternative structures have thus far eluded verification by structural methods such as protein crystallography.33−40 The structural flexibility in the S2 state is typically attributed to the mobile μ-oxo bridge (O5) between Mn1 and Mn4,31,41 producing “open” (A) and “closed” cubane (B) forms of the cluster (Figure 1e, see supplementary references in the Supporting Information). As recently discovered by Pantazis and co-workers, orientational Jahn–Teller isomerism in the resting S1 state41 generates the precursors for the two interconvertible A and B structures of the S2 state,31 which give rise to the low-spin (S = 1/2) and high-spin (S = 5/2) EPR signals in plant PSII at g = 2 and g ≈ 4.1, respectively, and the latter g ≈ 4.1 (and similar signals around this value) can only be produced by mutations or chemical treatments in cyanobacteria.42 These authors also proposed that the closed-cubane form is the entry to the S3 state,43,44 in agreement with molecular dynamics studies by Guidoni and co-workers.32,45 This closed-cubane interpretation for the S2 high-spin (S = 5/2) state is widely accepted in the field and consistent with the calculations in this report and will hence be employed in this study. However, we note that two competing interpretations exist. First, based on broken-symmetry density functional theory (BS-DFT) calculations with focus on spectroscopic parameter analysis, Corry and O’Malley proposed an isomer in the S2 state by W1 deprotonation to μ-O4 to rationalize the high-spin (S = 5/2) form46 and, on this basis, further identified a high-spin (S = 7/2) deprotonated intermediate with μ-hydroxo O4 during the S2 → S3 transition, without invoking a closed-cubane structure.47 Second, another model for the high-spin (S = 5/2) S2 state assumes the early binding of a substrate water to Mn1 as OH– originating from W3, as suggested by Siegbahn48 and later by Pushkar et al.49 For a detailed discussion of such models, see Text S6 in the Supporting Information.

The open-cubane S3 structure contains an extra oxygen ligand to Mn1 due to binding of an additional water molecule. This was proposed first by Siegbahn on the basis of DFT calculations50−53 that are found on the results from extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) experiments,54−56 showing that the S2–S3 transition involves the conversion of a five-coordinate Mn(III) to a six-coordinate Mn(IV). Cox et al. confirmed by advanced EPR that all Mn ions in the S3 state are hexa-coordinate and that the “water-added” open-cubane S3 structure, S3A,W (“W” denotes the extra water binding), is consistent with their experimental data.57 Isobe et al. constructed multiple S3 models58,59 that vary with regard to total spin and Mn-valence and proposed that the closed-to-open cubane transformation is possible in a stepwise process involving an oxyl–oxo precursor.60 By contrast, Capone et al.61 and Shoji et al.62 showed different feasible pathways for a direct closed-to-open cubane conversion. Regardless of the mechanistic details, a consensus has been reached that the OEC cluster in the S3 state (more precisely the S3+Yz state, see below) allows for unidirectional conversion from the water-added closed (S3B,W) to the open-cubane (S3A,W) form, but not vice versa (Figure 1e). S3B,W (S = 3) is proposed to be the precursor form of the final S3A,W (S = 3) under the pivot/carousel mechanism of water binding during the S2 → S3 transition.43,44,63 Importantly, the dominance of the open-cubane Mn core topology is consistent with the S3 state structures resolved by serial crystallography using X-ray free electron lasers (XFELs).35−38

Nevertheless, alternative S3 state models that assume early O–O bonding exist.1,23,64 For example, Corry and O’Malley proposed a chemical equilibrium between “oxo-hydroxo” and “peroxo” for O5–Ox in the S3 state, based on a comparison of experimental and BS-DFT calculated geometries and magnetic resonance properties.65−67 In higher-plant PSII, a recent combined EPR and DFT study by Zahariou et al. provided evidence, in PSII isolated from spinach for S3 being a mixed state of S3A,W (S = 3) and S3B,unbound (S = 6) (“unbound” denotes the unsaturated coordination of Mn4; “S3B,unbound” is used throughout to refer to the “S3B” in its original publication, and similarly S4B,unbound for S4B).68,69 Here, the dominant state (∼80%) has been identified as the S3B,unbound state, that is, a closed-cubane S3 state with penta-coordinate Mn4(IV) without additional bound water. In this view, it should be emphasized that the structural isomerism in the S3 state introduced here (and discussed later) should apply to that of cyanobacterial PSII, and the less populated S3 form in higher plants.

Consistent with the abovementioned findings for the S3+Yz state, it is commonly assumed that the O–O bond formation in the S4+ state also occurs in the open-cubane (S4A,W) conformation.4,35,37,51,53,57,71−79 However, there have been also several proposals based on a closed-cubane structure (S4B,W or S4B,unbound),4,68,69,73,75,80−87 which is in sharp contrast in terms of geometric configuration. This motivates us to investigate if structural heterogeneity exists just before the S4+ state is formed from the S3n state via electron abstraction by Yz•. In this paper, we mainly focus on the possibility of structural isomerization in the S3nYz• states (Scheme 1), employing DFT calculations. The correlation of our results with experimental observations and the implications for the mechanism of O–O bond formation are discussed.

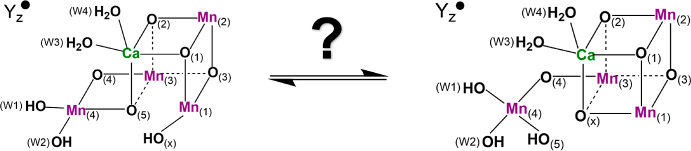

Scheme 1. Structural Isomerization between S3A,WYz• (Left) and S3B,WYz• (Right) in the S3nYz• (W1 = OH–) State Explored in the Present Study.

Amino acid ligands are omitted for clarity.

Results and Discussion

Unidirectional Structural Isomerization in the S3+Yz State

Unlike the structural interconversion simply caused by O5 shuttling between Mn1 and Mn4 in the S2 state (the most likely mechanism accounting for the EPR isomers, see Text S6 in the Supporting Information), isomerization in the S3+Yz state results from Mn3 ligand exchange between O5 and Ox. We revisited this process by our quantum chemical model (Figure S1 in the Supporting Information) and determined a direct conversion pathway connecting the open and closed-cubane structures. A notable phenomenon is that the incidental proton transfer is directed toward the moiety becoming a terminal ligand; protonation of the μ-oxo ligand is impossible in either isomer (O5H in S3A,W or OxH in S3B,W), which is justified by the relaxed potential energy scan for proton translocation between Ox and O5 (Figure 2d, Text S1 in the Supporting Information).

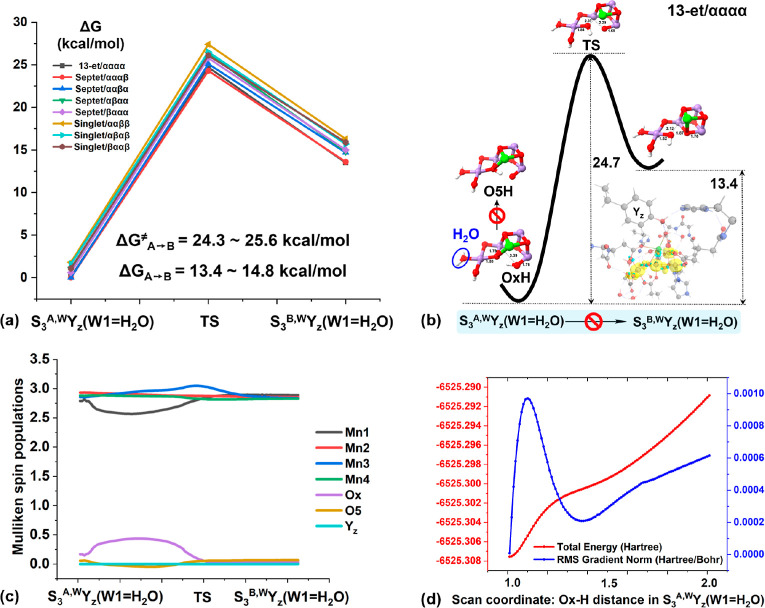

Figure 2.

(a) Relative Gibbs free energy profiles for the conversion between S3A,WYz(W1=H2O) and S3B,WYz(W1=H2O) in all the possible spin states of the S3+Yz state. Because of the close similarity to the other spin states, more information regarding the changes of (b) geometric structures, (c) electronic configurations along the MEP, and (d) relaxed PES scan curve of proton transfer between Ox and O5 are exemplified in the highest 13-et/αααα spin state. Spin populations are displayed in yellow contours and key interatomic distances are given in Å.

In contrast to Capone et al.,61 where the formal oxidation state of Mn3 is lowered from (IV) to (III), while Mn1 acquires a partial radical character in the proximity of the transition state (TS), our results show that the electronic configuration of the OEC cluster essentially remains constant along the minimum energy paths (MEPs). That means all Mn keep valence (IV) throughout as reflected by the Mulliken spin populations (Figure 2c, Text S2 and Table S2 in the Supporting Information). The reason may be attributed to the exclusion of structural and thermal fluctuations along the MEPs, which are instead present during the molecular dynamics simulations. Anyhow, consistent with Isobe et al.,60 our calculated S3A,W → S3B,W barriers of 24.3–25.6 kcal/mol and stabilization energies of 13.4–14.8 kcal/mol for the open-cubane form (S3A,W) on all the spin surfaces (Figure 2a,b, Table S1 in the Supporting Information) show that the same conclusion can be drawn, that is, conformational change in the S3+Yz state is essentially confined to the unidirectional closed-to-open cubane conversion and forbidden reversely. Consequently, the bidirectional structural flexibility prevalent in both S1 and S2 states has disappeared in the following S3+Yz state, with an overwhelming preference for the open-cubane structure.

It is worth mentioning that the abovementioned conclusion is strictly only valid for the S3+Yz state and does not apply for the S2+Yz• state, which can be formed from the S3+Yz state by electron back donation from Yz to Mn under certain conditions, as shown in some experimental findings.88−90 The structural equilibration in the S2nYz• state was suggested as a requirement for water exchange in the S3+Yz state,91 in which the open-to-closed conversion is involved and readily reversible, but necessitates a Mn(III) center within the cluster.

Reversible Structural Isomerization in the S3nYz• State

By various experimental approaches, it has been established that O2 formation and release begins after the flash-induced formation of the S3+Yz• state only after a lag phase of about 200 μs.12,70−92 This lag phase has been assigned to a deprotonation reaction in the S3+ to S3n transition, as shown in Figure 1d. Since the initial deprotonation site has been widely acknowledged as W1(H2O) (via the egress gate Asp61 to the lumen) during the S3 → S4 transition,52,53,78,93−96 this ligand was formulated as a hydroxide (OH–) in our S3nYz• model, in agreement with a series of previous computational work.52,53,94,96 In analogy to the abovementioned case of S3+Yz, redox-related events were not observed at any of the Mn centers along the whole MEP (Figure 3c and Table S4 in the Supporting Information) and various spin couplings do not significantly affect the energetics even after Yz• addition. The redox-irrelevance and spin-insensitivity for such a ligand exchange are understandable because the octahedral coordination geometry of Mn3(IV) basically maintains during the simultaneous movements of O5 and Ox in opposite directions, and the two oxygens never approach a bonding distance to cause Mn reduction.

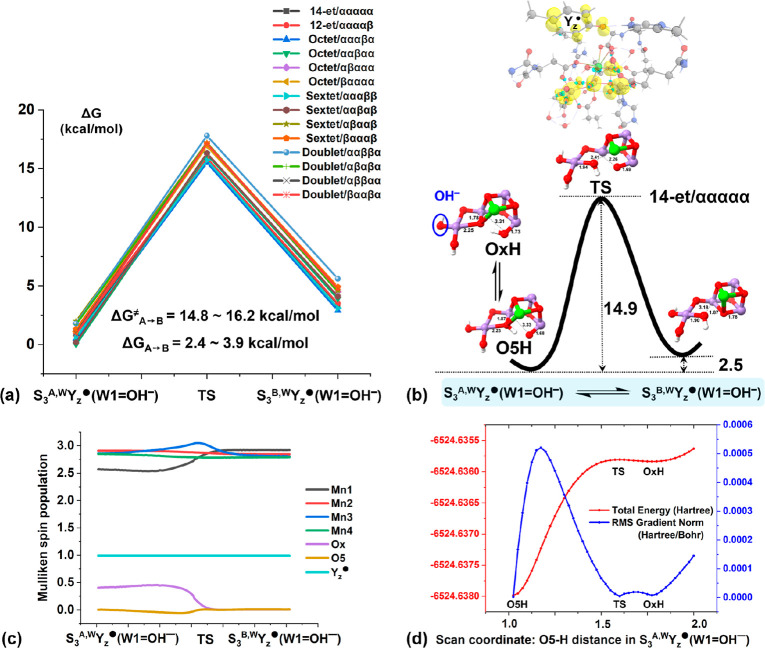

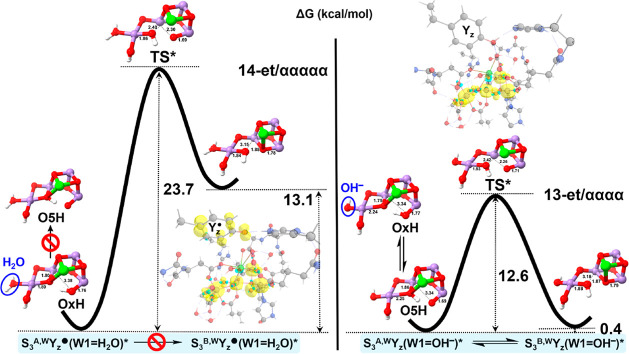

Figure 3.

(a) Relative Gibbs free energy profiles for the conversion between S3A,WYz•(W1=OH–) and S3B,WYz•(W1=OH–) in all the possible spin states of the S3nYz• state. Because of the close similarity to the other spin states, the highest 14-et/ααααα spin state was selected for visualizing more information regarding the changes of (b) geometric structures and (c) electronic configurations along the MEP, and (d) relaxed PES scan curve of proton transfer between Ox and O5.

Interestingly, the obtained reaction landscapes of the structural isomerization in the S3nYz• state is fundamentally changed with regard to both thermodynamics and kinetics (Figure 3a,b, Table S3 in the Supporting Information) as compared to that of the S3+Yz state (Tables S1 in the Supporting Information), allowing for a dynamically reversible isomerization S3A,WYz• ⇌ S3B,WYz• in chemical equilibrium. First, the relative thermodynamic stability of S3B,WYz• is greatly enhanced to only 2.4–3.9 kcal/mol higher in free energy than S3A,WYz• (vs 13.4–14.8 kcal/mol in the S3+Yz state). Superficially, according to the relationship between ΔG° and equilibrium constant K, this energy difference would still correspond to a major population of S3A,WYz• in the equilibrium at room temperature; however, overemphasis on the precise quantitative population of the isomers in the S3nYz• state would be undesirable because of the calculated small energy gap and the well-known intrinsic limitations in the accuracy of DFT methodology,97−100 and the ambiguous direction of the equilibrium shifting given the consumption of S3A,WYz• and/or S3B,WYz• when proceeding to the S4 state. Thus, the isomerism suggested here in S3nYz• resembles the situations in the S1 and S2 states,31,32,41 where the closed-cubane structures are also deemed important for the catalytic progression despite the calculated slight energetic disadvantages compared with the open-cubane forms, that is, +3.2 kcal/mol for S1B and +(1–2) kcal/mol for S2B (see Text S3 in the Supporting Information for the detailed analysis).26,31,32,41,48,101−104 As a consequence of the markedly closer energies of the isomers in the S3nYz• state, the predominance of the open-cubane structure is undermined and the significance of S3B,WYz• should be highlighted in addition to S3A,WYz•. Strictly speaking, one should not overlook the importance of either isomer in the S3nYz• state, considering the aforementioned uncertain factors that would lead to an indefinite identification of a dominant or most reactive component.

Besides the thermodynamics, the free energy barriers from S3A,WYz• to S3B,WYz• for all the possible spin states are dramatically reduced to 14.8–16.2 kcal/mol (vs 24.3–25.6 kcal/mol in the S3+Yz state), which allows for smooth production of S3B,WYz• at a level of milliseconds kinetics (see Text S4 in the Supporting Information for more details). It is noteworthy that the direct reactant for the isomerization turns out to involve the protonated O5H, which is reachable by facile deprotonation from Ox and vice versa (Figure 3d); this remarkably contrasts the situation in the S3+Yz state, where O5H is not achievable for S3A,W (Figure 2d). These results show a feasible pathway from S3A,WYz• to S3B,WYz• preceded by Ox deprotonation and demonstrate that the structural heterogeneity lost in the S3+Yz state becomes available again in the S3nYz• state. This leads to a more balanced constituent of the isomers, as compared to the dominance of the S3A,W conformation and the high energetic barrier for isomerization in the S3+Yz state.

W1 Deprotonation Facilitates the Open-to-Closed Isomerization

As shown above, a magnitude of ca. 10 kcal/mol decrease in both barrier heights and relative energies from S3+Yz to S3nYz• has largely changed the equilibrium distribution of the isomers. This is mainly manifested in the feasibility of S3A,WYz• converting to S3B,WYz•, since B to A is attainable in both the S3+Yz and S3nYz• states. Quite evidently, the S3nYz•(W1=OH–) state is differentiated from S3+Yz(W1=H2O) by its oxidized Yz• unit and deprotonated W1 ligand, that is, the asynchronous departure of an electron and a proton from two separated sites. Thus, two virtual states S3+Yz•(W1=H2O)* and S3nYz(W1=OH–)* characterizing the single effect were artificially fabricated in order to clarify the ultimate reason for the observed difference. Since the spin state selectivity is expected to bring little impact on the isomerization, only the highest spin states were studied for a comparison, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Relative Gibbs free energy profiles for the conversions between the virtual states S3A,WYz•(W1=H2O)* and S3B,WYz•(W1=H2O)* (left) and between the virtual states S3A,WYz(W1=OH–)* and S3B,WYz(W1=OH–)* (right) in their respective highest spin states; “*” denotes a virtual state.

The situation for the virtual S3+Yz•(W1=H2O)* and S3nYz(W1=OH–)* states fairly coincides with that of the S3+Yz(W1=H2O) and S3nYz•(W1=OH–) states, respectively, in terms of the reaction energetics and geometric parameters (Tables S5–S8 in the Supporting Information), as well as the proton mobility between Ox and O5 (Figures S2 and S3 in the Supporting Information). The comparison clearly reveals that it is the occurrence of W1(H2O) deprotonation, rather than appearance of the Yz• radical, that substantially promotes the A to B isomerization in the S3nYz• state. This is reasonable because the covalent bonding interactions within the Mn4CaO6 cluster should be much more powerful than the electrostatic effect brought by the distal Yz• group. Specifically, we expect that the strong σ donation from W1=OH– reinforces its coordination to Mn4 but considerably weakens the O5–Mn4 bonding, due to the “structural trans effect” in octahedral transition metal complexes.105−108 The diminished overlap between the Mn4 3d and O5 2p orbitals can in turn stabilize the O5 2p–H s covalency, increasing the basicity of O5 and explaining the accessibility of O5 protonation in both S3A,WYz•(W1=OH–) and S3A,WYz(W1=OH–)*. Furthermore, the Mn3–O5 bond is weakened by the protonated O5H, which therefore becomes easier to be substituted by Ox (oxo). The altered bond strengths can be seen from variations of the key bond lengths and Wiberg bond orders (Table S9 in the Supporting Information). To sum up, the feasibility of the open-to-closed isomerization in the S3nYz• state is directly attributable to W1(H2O) deprotonation, which causes a series of subtle changes in Mn–ligand interactions.

Although Yz• itself produces little chemical effect on the isomerization, its formation is necessary for the subsequent W1(H2O) deprotonation. After the third flash given to dark-adapted PSII, the S3+Yz• state forms accompanied by deprotonation of the phenolic oxygen of Yz to the ε-nitrogen of His190, and thus an extra positive charge accumulates within the vicinity of the Mn4CaO6 cluster. Thereafter, the Mn4-bound W1 serves as an ideal deprotonation site for charge compensation because it is in strong hydrogen-bonding interaction with the negatively charged D1-Asp61, which connects further to the proton exit channel and the lumen.39,52,56,81,95,109−114 Thereby, the occurrence of Yz oxidation is an essential prerequisite for the reversible structural isomerization in the S3Yz• state, from a perspective of the causal relationship.

It is noted that up to date, there is still no unambiguous/conclusive assignment for the protonation states of the titrable groups (especially W2 and Ox) of the OEC cluster in the S3+Yz and S3nYz• states; however, our models adopt the protonation states suggested by Cox et al.,57 which reproduced the experimental EPR and electron–nuclear double resonance (ENDOR) and electron–electron double resonance-detected nuclear magnetic resonance (EDNMR) of the S3 state, and are in good agreement with most computational studies.51,60,61,91,94,115−118 Still, we have also performed extensive additional computations and found that our conclusion still holds even if different protonation state distributions were considered (see Text S5 and Tables S10–S14 in the Supporting Information for the details).

Alternative Computational S3 State Models

For the S3+Yz and S3nYz• states, Corry and O’Malley proposed “oxo–hydroxo ⇌ oxo–oxo ⇌ peroxo” and “oxo–oxo ⇌ peroxo” equilibria to describe the chemical nature of “O5–Ox” in S3+Yz and S3nYz•, respectively.65,67 Early O–O bond formation in the S3 state was also explored by Pushkar et al.64 and Isobe et al.58,59 We note that the “oxo-hydroxo” model with all octahedral Mn(IV) employed in this study adequately fits the vast majority of results from EXAFS,5,116,119,120 EPR/ENDOR/EDNMR, and X-ray absorption and emission spectroscopies in the S3 state.57,118,121 In contrast, while it still remains unclear if the “oxo–oxo” model is consistent with these spectroscopic data, the “peroxo” model would produce two anisotropic Mn(III) and thus is clearly inconsistent with the experimental observations. It has been also ruled out by all the latest XFEL experiments with updated essential details (e.g., O5–O6/Ox distance),36−39 despite support from one initial study.35 The calculated S = 4 ground state of the peroxo model65 does not agree with the S = 3 signal observed experimentally.57 On the basis of substrate-water exchange,24,122 although we cannot fully exclude the “peroxo” model given the option of suitable structural/redox equilibria, obviously a stable peroxide can be ruled out. From the aspect of computational modeling, calculations by coupled cluster theory, which is beyond traditional DFT, also strongly disfavors the scenario based on an early-onset O–O bond formation in the S3 state.123

However, it remains possible that the “peroxo” form could constitute part of the redox equilibria in the S3 state and it might be catalytically relevant, but it should not represent the dominant form in the S3 state. For the S3nYz• state, the “peroxo” model was indeed considered as one possible option because water exchange dramatically slows down as compared to S3,124 but the model was also ruled out by the authors in that report because of the inconsistency with the results from time-resolved X-ray experiments.3,70,124 Still, we have in detail considered the “oxo–oxo” model in both the S3+Yz and S3nYz• states (Text S5 and Tables S12–S14 in the Supporting Information), and we can conclude that it does not change the basic conclusion of this study. Finally, we emphasize that the “oxo-hydroxo” model should be adopted (for cyanobacterial PSII) because of its representation of the most stable form of the ground state in the dominant population of the S3+Yz and its derived S3nYz• states; for high-plants, the “oxo-hydroxo” model is also valid in the novel closed-cubane S3 structure according to Zahariou et al.,68 but the circumstances of the structural isomerization, if exist in the water-unbound form, would need further investigations.

Comparison to Experimental Observations

Since experimental techniques probing into the S3 → S4 transition remain difficult, so far there is very limited information regarding the morphological changes of the Mn4CaO5(6) cluster upon formation of the S3nYz• state. Therefore, the structural isomerization found in this study should be seen as a theoretical prediction pending experimental verification. However, some suggestive evidence still exists in support of our proposal.

Nilsson et al. discovered that substrate-water exchange is arrested in the S3nYz• state because of the observed dramatically slowed kinetics as compared to earlier S states.124 As discussed therein, the possible reasons include the impossibility to generate a Mn(III) center that is required for water exchange,91 H+ release that leads to much stronger binding of the deprotonated group, and reconstruction of the H-bonding network after proton-coupled electron transfer upon Yz oxidation. Our proposed reversible isomerization is compatible with the observation because, in contrast to the S3A,WYz ⇌ S2Yz• equilibrium that supports water exchange in the S3+Yz state, the S3A,WYz• ⇌ S3B,WYz• equilibrium does not facilitate water exchange due to the lack of Mn(III) formation. In fact, the chemical equilibrium would cause extensive rearrangement of the locations and H-bonding orientations of water molecules and may thus even contribute to slowing down the rate of substrate water exchange in the S3nYz• state. Such changes in the H-bonding network have also been suggested to affect the distribution of the conformational microstates of water molecules and to thereby affect the rate of the S3nYz• → S0Yz transition.125

Bao and Burnap studied the O2 release kinetics by site-directed mutagenesis and found that both the lag and slow phases during the S3+Yz → S0nYz transition are retarded. On that basis, they suggested that “proton tautomerization” and/or “structural isomerization” precede(s) dioxygen formation.93 Specifically, they suggested two interpretations. For proton tautomerization, they proposed that it would be followed by O–O bond formation via W3–W2 nucleophilic attack,72,81,82,85 while in case of open-closed structural isomerization, O–O bond formation by oxo–oxyl radical coupling between W2 and O5 may occur, in line with previous suggestions.80,83,84 We note that O–O bond formation via water nucleophilic attack (WNA) appears less favorable on the basis of recent experiments36,37,124 and theoretical calculations.71,126 Indeed, our present results provide further support for the variant radical coupling mechanism using a closed-cubane S4 structure for O2 evolution because our theoretical finding shows that the S4B,W structure could be obtainable via the open-to-closed rearrangement in the S3nYz• state (rather than in the S3+Yz state as assumed in ref (84)).

Thus, the open-closed isomerization in the S3nYz• state may correspond to the proposed “structural isomerization” preceding dioxygen formation93 and to thereby constitute the rate limiting 1–2 ms phase (slow phase) that follows a 200 μs lag phase (Figure 1d) and precedes the much more rapid O2 formation.3,12−22,92,127 According to the Eyring–Polanyi equation of TS theory assuming a standard pre-exponential factor,128−130 the 1–2 ms kinetics is calculated to correspond to an activation free energy ∼14 kcal/mol at room temperature. Given the limited errors from DFT methodology and possibly experimental measurement, a safer quantity for the barrier should be around 13–15 kcal/mol for a process that occurs on a timescale of milliseconds.71 Siegbahn ascribed the slow phase of O2 formation to an intramolecular proton transfer step with 10.2 kcal/mol barrier,52 but as he pointed out, considering a typical accuracy within 3–5 kcal/mol, which normally overestimates barriers for a DFT hybrid functional,51,97,98,131 it is far below the required limit for a millisecond process.52 By comparison, our calculated barriers of 14.8–16.2 kcal/mol for all the possible spin states are in much better agreement with the experimental kinetics (see Text S4 in the Supporting Information for more details). If the open-to-closed transition in the S3nYz• state was indeed the main rate limiting step for O2 formation, this would mean that O2 formation would start exclusively from the S3B,WYz• state, and radical coupling from the S3A,WYz• state would not be possible for reasons still to be determined. Thus, at the current stage of knowledge, we do not emphasize the proposed isomerization as the only possibility taking place in S3nYz• → S4+Yz before compelling experimental evidence emerges; however, the reversible open-to-closed structural rearrangement should be regarded as a viable mechanism or at least as part of processes responsible for the slow phase.

Implications for the Mechanism of O–O Bond Formation

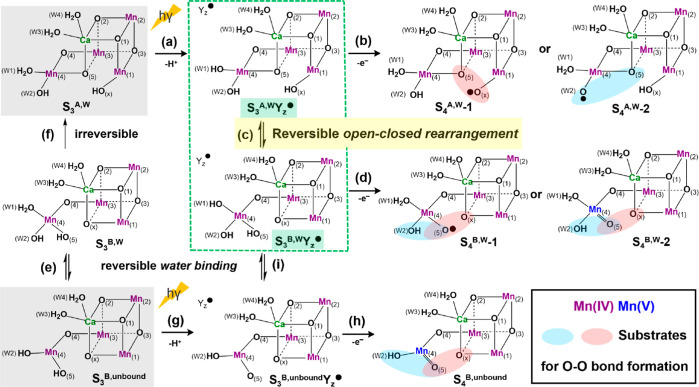

The proposed reversible open-closed interconversion in the S3nYz• state has important implications for the mechanism of O–O bond formation in the S4 state. This is illustrated in Scheme 2, which starts from the two structural architectures S3A,W and S3B,unbound observed by XFEL35−38 and EPR experiments,44,68 respectively. The first route (a) → (b) from S3A,W to S4A,W-1 expresses Siegbahn’s oxo(O5)–oxyl(Ox) coupling mechanism that he found to be energetically most favorable.51,53,71,76 Here, the Mn1(IV)-bound Ox radical couples with μ-O5 in an open-cubane structure. Alternatively, the radical could be localized at W2 if it is deprotonated instead of Ox, and its coupling with μ-O5 in S4A,W-2 might be an option, which, however, has not gained support from recent DFT calculations.79,84

Scheme 2. Possible mechanisms of the S3 → S4 transition and O–O Bond formation in the S4 State.

S3A,W and S3B,unbound in gray stand for the two potential starting configurations in the S3 state, resolved in cyanobacteria and higher-plant PSII by XFEL and EPR experiments, respectively.35−38,44,68 The process focused in this work is highlighted in the green dashed box. Candidate substrates are encircled in red (favored) or blue (possible alternatives). Mn formal oxidation states (IV)(V) are displayed in different colors. The superscript “W”/“unbound” means hexa/penta-coordinate Mn4 with a water bound/unbound water trans to O5. The annotations for sequence numbers: (a,g) Yz oxidation followed by proton release; (b,d,h) intramolecular proton transfer followed by Ox/W2/O5/Mn4 oxidation; (c) reversible open-closed rearrangement in the S3nYz● state, as proposed in this study; (e,i) reversible water binding to the five-coordinate Mn4(IV) in the closed-cubane structure; and (f) irreversible closed-to-open conversion in the S3 state. Other proposed mechanisms are discussed in the text. It is noted that the oxygen labeling for S3B,W and S3B,unbound (and their derivatives) is chosen for consistency with that established by serial crystallography for the S3A,W36,38,39 and for convenience to describe all the transitions uniformly. These labels do not reflect the origin of the oxygens with regard to the S1 and S2 states because several options for water insertion during the S2 → S3 transition are still discussed;6,7,32,38,43,48,52,62,82,101,120,132−139 an alternative nomenclature based on S3B,unbound and the pivot/carousel water insertion is shown in Figure S4 in the Supporting Information.

For the intermediate S3A,WYz• state prior to S4, our present results provide the first theoretical basis for the (reversible) conversion to S3B,WYz• by route (c), thereby diversifying alternative pathways leading to O–O bond formation in the S4 state with a closed-cubane type. Specifically, S3B,WYz• with the octahedral Mn4(IV) coordination may proceed to S4 by O5 or Mn4 oxidation through route (d), producing the O5 radical in S4B,W-1, or alternatively, Mn4(V) in S4B,W-2. Both options, W2–O5 coupling (blue) on Mn4 and O5–Ox coupling involving multiple metal (Mn and Ca) centers (red), are worth considering. It is noted that O5–Ox coupling in the S4B,W-1 state resembles the variant oxyl–oxo mechanism by Li and Siegbahn,84 which was based on previous experimental proposals.4,80,124

The S3B,unbound state may either evolve to S3A,W via S3B,W after (reversible) water binding by the “pivot“ or “carousel” mechanism43,44,120,132−134 through the route (e) → (f) and then advance to the O2 formation routes described above, or, as suggested by Pantazis and collaborators, directly proceed to S4B,unbound without water binding by the route (g) → (h).68,69,87 The latter pathway involves a penta-coordinate Mn4(IV) center and would lead to Mn4(V) where nucleophilic Ox-O5 coupling68,69,87 or hydroxo-oxo coupling between W2 and O5 might be possible. We note that the finding in the present study can provide an additional route (a) → (c) → (i) → (h) from S3A,W to S4B,unbound (other than from S3B,unbound).

Alternative mechanisms proposed in the literature include WNA from Ca-bound W3 onto the electron-deficient Mn4(V)=O (W2)6,72,81,85 and oxyl-oxo coupling between W1 and μ-oxo O4.78 Both appear inconsistent with mass spectrometric and EPR-based substrate water exchange data, which show that both substrates are bound to Mn(IV) in the S3+Yz and S3Yz• states (excluding WNA),122,124 and are best consistent with O5 as the slow exchanging substrate water.4,24,80,83,122,124,140−143 Nevertheless, these suggestions will also be further scrutinized in future DFT calculations.

Since S3A,WYz• and S3B,WYz• are nearly isoenergetic and for both states, low-energy routes for O–O bond formation via radical coupling have been determined,51,84 the intriguing possibility arises from the results of this study that O–O bond formation may occur via two routes, or even more, if also the S3B,unboundYz• → S4B,unboundYz → S0Yz path in “water-deficient” catalytic sites is taken into account.68,69 While recent water exchange experiments in the S2 state have reported first evidence for two possible fast exchanging water substrates,24,122 the current water exchange data in the S3 state are best consistent with only one set of substrate waters. This would favor that either S4B,W/S4B,unbound (substrates: W2 and O5) or S4A,W (substrates: Ox and O5) would be involved. However, the present study suggests that the energetic and kinetic differences between these possible routes are so small that minor differences between species or experimental conditions could favor one or the other pathway.

Conclusions

In summary, we have identified a reversible open-to-closed isomerization for the S3nYz• state, in contrast to the unidirectional conversion in the S3+Yz state. This isomerization immediately before O2 formation is activated by deprotonation of a Mn-bound water (W1) after tyrosine Yz oxidation. The structural rearrangement may constitute or contribute to the slow kinetic phase that prepares the Mn4CaO6 cluster for O2 formation. Thus, the restored structural heterogeneity prior to the S4 state diversifies the viable options for O–O bond formation in PSII. In this way, the availability of both open and closed-cubane structures in the S4 state may reflect a “two-pronged” arrangement of the OEC, allowing for efficient and robust water oxidation, and may have contributed to its evolutionary development. The elegant structural reversibility triggered by proton release in the natural enzyme may provide a useful reference for designs of artificial catalysts.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the starting-up package of Westlake University (to L.S.), the Swedish Research Council 2020-03809 (to J.M.) and 2020-06701 (to L.K.). We thank Westlake University HPC Center for computation support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c03528.

Model construction, spin state definition, computational details, supplementary texts, tables, figures, and references, and optimized Cartesian coordinates (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Messinger J.; Renger G.. Photosynthetic water splitting. Primary Processes of Photosynthesis, Part 2: Principles and Apparatus; The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2008; Vol. 9, pp 291–349. [Google Scholar]

- Barber J. Photosynthetic energy conversion: natural and artificial. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 185–196. 10.1039/b802262n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H.; Zaharieva I.; Haumann M. Recent developments in research on water oxidation by photosystem II. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 3–10. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.; Messinger J. Reflections on substrate water and dioxygen formation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2013, 1827, 1020–1030. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano J.; Yachandra V. Mn4Ca cluster in photosynthesis: where and how water is oxidized to dioxygen. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 4175–4205. 10.1021/cr4004874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinyard D. J.; Brudvig G. W. Progress toward a molecular mechanism of water oxidation in photosystem II. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2017, 68, 101–116. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-052516-044820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A. Missing pieces in the puzzle of biological water oxidation. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 9477–9507. 10.1021/acscatal.8b01928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lubitz W.; Chrysina M.; Cox N. Water oxidation in photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 2019, 142, 105–125. 10.1007/s11120-019-00648-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge W. Oxygenic photosynthesis: history, status and perspective. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2019, 52, e1 10.1017/S0033583518000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.; Pantazis D. A.; Lubitz W. Current understanding of the mechanism of water oxidation in photosystem II and its relation to XFEL data. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2020, 89, 795–820. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-011520-104801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok B.; Forbush B.; McGloin M. Cooperation of charges in photosynthetic O2 evolution. I. a linear four-step mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. 1970, 11, 457–475. 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1970.tb06017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport F.; Blanchard-Desce M.; Lavergne J. Kinetics of electron transfer and electrochromic change during the redox transitions of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1994, 1184, 178–192. 10.1016/0005-2728(94)90222-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H.; Haumann M. Eight steps preceding O-O bond formation in oxygenic photosynthesis-A basic reaction cycle of the photosystem II manganese complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 472–483. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H.; Haumann M. Time-resolved X-ray spectroscopy leads to an extension of the classical S-state cycle model of photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Photosynth. Res. 2007, 92, 327–343. 10.1007/s11120-007-9141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauss A.; Haumann M.; Dau H. Alternating electron and proton transfer steps in photosynthetic water oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 16035–16040. 10.1073/pnas.1206266109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato Y.; Shibamoto T.; Yamamoto S.; Watanabe T.; Ishida N.; Sugiura M.; Rappaport F.; Boussac A. Influence of the PsbA1/PsbA3, Ca2+/Sr2+ and Cl–/Br– exchanges on the redox potential of the primary quinone QA in photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus as revealed by spectroelectrochemistry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2012, 1817, 1998–2004. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauss A.; Haumann M.; Dau H. Seven steps of alternating electron and proton transfer in photosystem II water oxidation traced by time-resolved photothermal beam deflection at improved sensitivity. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 119, 2677–2689. 10.1021/jp509069p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussac A.; Rutherford A. W.; Sugiura M. Electron transfer pathways from the S2-states to the S3-states either after a Ca2+/Sr2+or a Cl-/I- exchange in photosystem II from Thermosynechococcus elongatus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 576–586. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi T. Fourier transform infrared difference and time-resolved infrared detection of the electron and proton transfer dynamics in photosynthetic water oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 35–45. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus R. J. FTIR studies of metal ligands, networks of hydrogen bonds, and water molecules near the active site Mn4CaO5 cluster in photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 19–34. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaharieva I.; Dau H. Energetics and kinetics of S-State transitions monitored by delayed chlorophyll fluorescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 386. 10.3389/fpls.2019.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäusle S. M.; Abzaliyeva A.; Greife P.; Simon P. S.; Perez R.; Zilliges Y.; Dau H. Activation energies for two steps in the S2 → S3 transition of photosynthetic water oxidation from time-resolved single-frequency infrared spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 215101. 10.1063/5.0027995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renger G. Mechanism of light induced water splitting in photosystem II of oxygen evolving photosynthetic organisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2012, 1817, 1164–1176. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lichtenberg C.; Messinger J. Substrate water exchange in the S2 state of photosystem II is dependent on the conformation of the Mn4Ca cluster. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 12894–12908. 10.1039/d0cp01380c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dismukes G. C.; Siderer Y. Intermediates of a polynuclear manganese center involved in photosynthetic oxidation of water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1981, 78, 274–278. 10.1073/pnas.78.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussac A.; Ugur I.; Marion A.; Sugiura M.; Kaila V. R. I.; Rutherford A. W. The low spin-high spin equilibrium in the S2-state of the water oxidizing enzyme. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2018, 1859, 342–356. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2018.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussac A.; Rutherford A. W. Comparative study of the g=4.1 EPR signals in the S2 state of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2000, 1457, 145–156. 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel R.; Brudvig G. W. Oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II: correlating structure with spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 11812–11821. 10.1039/c4cp00493k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann J. L.; Rutherford A. W. EPR studies of the oxygen-evolving enzyme of Photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1984, 767, 160–167. 10.1016/0005-2728(84)90091-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J. L.; Sauer K. EPR detection of a cryogenically photogenerated intermediate in photosynthetic oxygen evolution. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1984, 767, 21–28. 10.1016/0005-2728(84)90075-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A.; Ames W.; Cox N.; Lubitz W.; Neese F. Two interconvertible structures that explain the spectroscopic properties of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II in the S2 state. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 9935–9940. 10.1002/anie.201204705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovi D.; Narzi D.; Guidoni L. The S2 state of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II explored by QM/MM dynamics: spin surfaces and metastable states suggest a reaction path towards the S3 state. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11744–11749. 10.1002/anie.201306667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umena Y.; Kawakami K.; Shen J.-R.; Kamiya N. Crystal structure of oxygen-evolving photosystem II at a resolution of 1.9 Å. Nature 2011, 473, 55–60. 10.1038/nature09913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M.; Akita F.; Hirata K.; Ueno G.; Murakami H.; Nakajima Y.; Shimizu T.; Yamashita K.; Yamamoto M.; Ago H.; Shen J.-R. Native structure of photosystem II at 1.95 Å resolution viewed by femtosecond X-ray pulses. Nature 2015, 517, 99–103. 10.1038/nature13991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M.; Akita F.; Sugahara M.; Kubo M.; Nakajima Y.; Nakane T.; Yamashita K.; Umena Y.; Nakabayashi M.; Yamane T.; Nakano T.; Suzuki M.; Masuda T.; Inoue S.; Kimura T.; Nomura T.; Yonekura S.; Yu L.-J.; Sakamoto T.; Motomura T.; Chen J.-H.; Kato Y.; Noguchi T.; Tono K.; Joti Y.; Kameshima T.; Hatsui T.; Nango E.; Tanaka R.; Naitow H.; Matsuura Y.; Yamashita A.; Yamamoto M.; Nureki O.; Yabashi M.; Ishikawa T.; Iwata S.; Shen J.-R. Light-induced structural changes and the site of O=O bond formation in PSII caught by XFEL. Nature 2017, 543, 131–135. 10.1038/nature21400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern J.; Chatterjee R.; Young I. D.; Fuller F. D.; Lassalle L.; Ibrahim M.; Gul S.; Fransson T.; Brewster A. S.; Alonso-Mori R.; Hussein R.; Zhang M.; Douthit L.; de Lichtenberg C.; Cheah M. H.; Shevela D.; Wersig J.; Seuffert I.; Sokaras D.; Pastor E.; Weninger C.; Kroll T.; Sierra R. G.; Aller P.; Butryn A.; Orville A. M.; Liang M.; Batyuk A.; Koglin J. E.; Carbajo S.; Boutet S.; Moriarty N. W.; Holton J. M.; Dobbek H.; Adams P. D.; Bergmann U.; Sauter N. K.; Zouni A.; Messinger J.; Yano J.; Yachandra V. K. Structures of the intermediates of Kok’s photosynthetic water oxidation clock. Nature 2018, 563, 421–425. 10.1038/s41586-018-0681-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga M.; Akita F.; Yamashita K.; Nakajima Y.; Ueno G.; Li H.; Yamane T.; Hirata K.; Umena Y.; Yonekura S.; Yu L.-J.; Murakami H.; Nomura T.; Kimura T.; Kubo M.; Baba S.; Kumasaka T.; Tono K.; Yabashi M.; Isobe H.; Yamaguchi K.; Yamamoto M.; Ago H.; Shen J.-R. An oxyl/oxo mechanism for oxygen-oxygen coupling in PSII revealed by an x-ray free-electron laser. Science 2019, 366, 334–338. 10.1126/science.aax6998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim M.; Fransson T.; Chatterjee R.; Cheah M. H.; Hussein R.; Lassalle L.; Sutherlin K. D.; Young I. D.; Fuller F. D.; Gul S.; Kim I.-S.; Simon P. S.; de Lichtenberg C.; Chernev P.; Bogacz I.; Pham C. C.; Orville A. M.; Saichek N.; Northen T.; Batyuk A.; Carbajo S.; Alonso-Mori R.; Tono K.; Owada S.; Bhowmick A.; Bolotovsky R.; Mendez D.; Moriarty N. W.; Holton J. M.; Dobbek H.; Brewster A. S.; Adams P. D.; Sauter N. K.; Bergmann U.; Zouni A.; Messinger J.; Kern J.; Yachandra V. K.; Yano J. Untangling the sequence of events during the S2 → S3 transition in photosystem II and implications for the water oxidation mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 12624–12635. 10.1073/pnas.2000529117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein R.; Ibrahim M.; Bhowmick A.; Simon P. S.; Chatterjee R.; Lassalle L.; Doyle M.; Bogacz I.; Kim I.-S.; Cheah M. H.; Gul S.; de Lichtenberg C.; Chernev P.; Pham C. C.; Young I. D.; Carbajo S.; Fuller F. D.; Alonso-Mori R.; Batyuk A.; Sutherlin K. D.; Brewster A. S.; Bolotovsky R.; Mendez D.; Holton J. M.; Moriarty N. W.; Adams P. D.; Bergmann U.; Sauter N. K.; Dobbek H.; Messinger J.; Zouni A.; Kern J.; Yachandra V. K.; Yano J. Structural dynamics in the water and proton channels of photosystem II during the S2 to S3 transition. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6531. 10.1038/s41467-021-26781-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee R.; Lassalle L.; Gul S.; Fuller F. D.; Young I. D.; Ibrahim M.; de Lichtenberg C.; Cheah M. H.; Zouni A.; Messinger J.; Yachandra V. K.; Kern J.; Yano J. Structural isomers of the S2 state in photosystem II: do they exist at room temperature and are they important for function?. Physiol. Plant. 2019, 166, 60–72. 10.1111/ppl.12947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosou M.; Zahariou G.; Pantazis D. A. Orientational Jahn-Teller isomerism in the dark-stable state of nature’s water oxidase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13493–13499. 10.1002/anie.202103425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retegan M.; Pantazis D. A. Differences in the active site of water oxidation among photosynthetic organisms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14340–14343. 10.1021/jacs.7b06351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retegan M.; Krewald V.; Mamedov F.; Neese F.; Lubitz W.; Cox N.; Pantazis D. A. A five-coordinate Mn(IV) intermediate in biological water oxidation: spectroscopic signature and a pivot mechanism for water binding. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 72–84. 10.1039/c5sc03124a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysina M.; Heyno E.; Kutin Y.; Reus M.; Nilsson H.; Nowaczyk M. M.; DeBeer S.; Neese F.; Messinger J.; Lubitz W.; Cox N. Five-coordinate MnIV intermediate in the activation of nature’s water splitting cofactor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116, 16841–16846. 10.1073/pnas.1817526116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narzi D.; Bovi D.; Guidoni L. Pathway for Mn-cluster oxidation by tyrosine-Z in the S2 state of photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 8723–8728. 10.1073/pnas.1401719111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry T. A.; O’Malley P. J. Proton isomers rationalize the high- and low-spin forms of the S2 state intermediate in the water-oxidizing reaction of photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 5226–5230. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b01372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry T. A.; O’Malley P. J. Molecular identification of a high-spin deprotonated intermediate during the S2 to S3 transition of nature’s water-oxidizing complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10240–10243. 10.1021/jacs.0c01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. The S2 to S3 transition for water oxidation in PSII (photosystem II), revisited. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 22926–22931. 10.1039/c8cp03720e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushkar Y.; Ravari A. K.; Jensen S. C.; Palenik M. Early binding of substrate oxygen is responsible for a spectroscopically distinct S2 state in photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 5284–5291. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b01255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. A structure-consistent mechanism for dioxygen formation in photosystem II. Chem.—Eur. J. 2008, 14, 8290–8302. 10.1002/chem.200800445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. Structures and energetics for O2 formation in photosystem II. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1871–1880. 10.1021/ar900117k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. Mechanisms for proton release during water oxidation in the S2 to S3 and S3 to S4 transitions in photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 4849–4856. 10.1039/c2cp00034b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. Water oxidation mechanism in photosystem II, including oxidations, proton release pathways, O-O bond formation and O2 release. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2013, 1827, 1003–1019. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H.; Andrews J. C.; Roelofs T. A.; Latimer M. J.; Liang W.; Yachandra V. K.; Sauer K.; Klein M. P. Structural consequences of ammonia binding to the manganese center of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex: an X-ray absorption spectroscopy study of isotropic and oriented photosystem II particles. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 5274–5287. 10.1021/bi00015a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haumann M.; Müller C.; Liebisch P.; Iuzzolino L.; Dittmer J.; Grabolle M.; Neisius T.; Meyer-Klaucke W.; Dau H. Structural and oxidation state changes of the photosystem II manganese complex in four transitions of the water oxidation cycle (S0 → S1, S1 → S2, S2 → S3, and S3,4 → S0) characterized by X-ray absorption spectroscopy at 20 K and room temperature. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 1894–1908. 10.1021/bi048697e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau H.; Haumann M. The manganese complex of photosystem II in its reaction cycle-Basic framework and possible realization at the atomic level. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 273–295. 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cox N.; Retegan M.; Neese F.; Pantazis D. A.; Boussac A.; Lubitz W. Electronic structure of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II prior to O-O bond formation. Science 2014, 345, 804–808. 10.1126/science.1254910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe H.; Shoji M.; Shen J.-R.; Yamaguchi K. Chemical equilibrium models for the S3 state of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 502–511. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe H.; Shoji M.; Suzuki T.; Shen J.-R.; Yamaguchi K. Spin, valence, and structural isomerism in the S3 State of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II as a manifestation of multimetallic cooperativity. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 2375–2391. 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe H.; Shoji M.; Suzuki T.; Shen J.-R.; Yamaguchi K. Exploring reaction pathways for the structural rearrangements of the Mn cluster induced by water binding in the S3 state of the oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2021, 405, 112905. 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capone M.; Bovi D.; Narzi D.; Guidoni L. Reorganization of substrate waters between the closed and open cubane conformers during the S2 to S3 transition in the oxygen evolving complex. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 6439–6442. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoji M.; Isobe H.; Yamaguchi K. QM/MM study of the S2 to S3 transition reaction in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2015, 636, 172–179. 10.1016/j.cplett.2015.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askerka M.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. The O2-evolving complex of photosystem II: recent insights from quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM), extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), and femtosecond X-ray crystallography data. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 41–48. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pushkar Y.; Davis K. M.; Palenik M. C. Model of the oxygen evolving complex which is highly predisposed to O-O bond formation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 3525–3531. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b00800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry T. A.; O’Malley P. J. Evidence of O-O bond formation in the final metastable S3 state of nature’s water oxidizing complex implying a novel mechanism of water oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6269–6274. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b02793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry T. A.; O’Malley P. J. Electronic–level View of O–O bond formation in nature’s water oxidizing complex. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 4221–4225. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corry T. A.; O’Malley P. J. S3 state models of nature’s water oxidizing complex: analysis of bonding and magnetic exchange pathways, assessment of experimental electron paramagnetic resonance data, and Implications for the water oxidation mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 10097–10107. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.1c04459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahariou G.; Ioannidis N.; Sanakis Y.; Pantazis D. A. Arrested substrate binding resolves catalytic intermediates in higher-plant water oxidation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 3156–3162. 10.1002/anie.202012304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewald V.; Neese F.; Pantazis D. A. Implications of structural heterogeneity for the electronic structure of the final oxygen-evolving intermediate in photosystem II. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2019, 199, 110797. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2019.110797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haumann M.; Liebisch P.; Müller C.; Barra M.; Grabolle M.; Dau H. Photosynthetic O2 formation tracked by time-resolved X-ray experiments. Science 2005, 310, 1019–1021. 10.1126/science.1117551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. O-O bond formation in the S4 state of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II. Chem.—Eur. J. 2006, 12, 9217–9227. 10.1002/chem.200600774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinyard D. J.; Khan S.; Brudvig G. W. Photosynthetic water oxidation: binding and activation of substrate waters for O-O bond formation. Faraday Discuss. 2015, 185, 37–50. 10.1039/c5fd00087d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J.-R. The structure of photosystem II and the mechanism of water oxidation in photosynthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 23–48. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewald V.; Retegan M.; Neese F.; Lubitz W.; Pantazis D. A.; Cox N. Spin state as a marker for the structural evolution of nature’s water-splitting catalyst. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 488–501. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; He L.-L.; Zhao D.-X.; Gong L.-D.; Liu C.; Yang Z.-Z. How does ammonia bind to the oxygen-evolving complex in the S2 state of photosynthetic water oxidation? Theoretical support and implications for the W1 substitution mechanism. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 31551–31565. 10.1039/c6cp05725j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Li H.; He L.-L.; Zhao D.-X.; Gong L.-D.; Yang Z.-Z. The open-cubane oxo-oxyl coupling mechanism dominates photosynthetic oxygen evolution: a comprehensive DFT investigation on O-O bond formation in the S4 state. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 13909–13923. 10.1039/c7cp01617d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Li H.; He L.-L.; Zhao D.-X.; Gong L.-D.; Yang Z.-Z. Theoretical reflections on the structural polymorphism of the oxygen-evolving complex in the S2 state and the correlations to substrate water exchange and water oxidation mechanism in photosynthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 833–846. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima K.; Takaoka T.; Kimura H.; Saito K.; Ishikita H. O2 evolution and recovery of the water-oxidizing enzyme. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1247. 10.1038/s41467-018-03545-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Zhang B.; Kloo L.; Sun L. Necessity of structural rearrangements for O-O bond formation between O5 and W2 in photosystem II. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 57, 436–442. 10.1016/j.jechem.2020.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messinger J. Evaluation of different mechanistic proposals for water oxidation in photosynthesis on the basis of Mn4OxCa structures for the catalytic site and spectroscopic data. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2004, 6, 4764–4771. 10.1039/b406437b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira K. N.; Iverson T. M.; Maghlaoui K.; Barber J.; Iwata S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science 2004, 303, 1831–1838. 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproviero E. M.; Gascón J. A.; McEvoy J. P.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. Quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics study of the catalytic cycle of water splitting in photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3428–3442. 10.1021/ja076130q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson H.; Krupnik T.; Kargul J.; Messinger J. Substrate water exchange in photosystem II core complexes of the extremophilic red alga cyanidioschyzon merolae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 1257–1262. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Siegbahn P. E. M. Alternative mechanisms for O2 release and O-O bond formation in the oxygen evolving complex of photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 12168–12174. 10.1039/c5cp00138b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber J. A mechanism for water splitting and oxygen production in photosynthesis. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 17041. 10.1038/nplants.2017.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Sun L. Why nature chose the Mn4CaO5 cluster as water-splitting catalyst in photosystem II: a new hypothesis for the mechanism of O-O bond formation. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 14381–14387. 10.1039/c8dt01931b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio M.; Pantazis D. A. Successes, challenges, and opportunities for quantum chemistry in understanding metalloenzymes for solar fuels research. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 3952–3974. 10.1039/d1cc00705j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos M. H.; van Gorkom H. J.; van Leeuwen P. J. An electroluminescence study of stabilization reactions in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 1991, 1056, 27–39. 10.1016/s0005-2728(05)80069-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Wijn R.; van Gorkom H. J. S-state dependence of the miss probability in photosystem II. Photosynth. Res. 2002, 72, 217–222. 10.1023/a:1016128632704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijer P.; Morvaridi F.; Styring S. The S3 state of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II Is converted to the S2YZ• state at alkaline pH. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 10881–10891. 10.1021/bi010040v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. Substrate water exchange for the oxygen evolving complex in PSII in the S1, S2, and S3 states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9442–9449. 10.1021/ja401517e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razeghifard M. R.; Pace R. J. EPR kinetic studies of oxygen release in Thylakoids and PSII membranes: a kinetic intermediate in the S3 to S0 transition. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 1252–1257. 10.1021/bi9811765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao H.; Burnap R. L. Structural rearrangements preceding dioxygen formation by the water oxidation complex of photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, E6139–E6147. 10.1073/pnas.1512008112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narzi D.; Capone M.; Bovi D.; Guidoni L. Evolution from S3 to S4 states of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II monitored by quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) dynamics. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 10820–10828. 10.1002/chem.201801709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda H.; Kawashima K.; Ueda K.; Ikeda T.; Saito K.; Ninomiya R.; Hida C.; Takahashi Y.; Ishikita H. Proton transfer pathway from the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II substantiated by extensive mutagenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2021, 1862, 148329. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgöwer F.; Gamiz-Hernandez A. P.; Rutherford A. W.; Kaila V. R. I. Molecular principles of redox-coupled protonation dynamics in photosystem II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 7171–7180. 10.1021/jacs.1c13041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. The performance of hybrid DFT for mechanisms involving transition metal complexes in enzymes. J. Biol. Inorg Chem. 2006, 11, 695–701. 10.1007/s00775-006-0137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomberg M. R. A.; Borowski T.; Himo F.; Liao R.-Z.; Siegbahn P. E. M. Quantum chemical studies of mechanisms for metalloenzymes. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 3601–3658. 10.1021/cr400388t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Density functional theory for transition metals and transition metal chemistry. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 10757–10816. 10.1039/b907148b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M.; Himo F. The quantum chemical cluster approach for modeling enzyme reactions. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011, 1, 323–336. 10.1002/wcms.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugur I.; Rutherford A. W.; Kaila V. R. I. Redox-coupled substrate water reorganization in the active site of photosystem II-the role of calcium in substrate water delivery. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2016, 1857, 740–748. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinyard D. J.; Khan S.; Askerka M.; Batista V. S.; Brudvig G. W. Energetics of the S2 state spin isomers of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 1020–1025. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b00110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isobe H.; Shoji M.; Shen J.-R.; Yamaguchi K. Strong coupling between the hydrogen bonding environment and redox chemistry during the S2 to S3 transition in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 13922–13933. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b05740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitow M.; Becker U.; Riplinger C.; Valeev E. F.; Neese F. A new near-linear scaling, efficient and accurate, open-shell domain-based local pair natural orbital coupled cluster singles and doubles theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 164105. 10.1063/1.4981521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quagliano J. V.; Schubert L. The trans effect in complex inorganic compounds. Chem. Rev. 1952, 50, 201–260. 10.1021/cr60156a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shustorovich E. M.; Porai-Koshits M. A.; Buslaev Y. A. The mutual influence of ligands in transition metal coordination compounds with multiple metal-ligand bonds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1975, 17, 1–98. 10.1016/s0010-8545(00)80300-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burdett J. K.; Albright T. A. Trans influence and mutual influence of ligands coordinated to a central atom. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 2112–2120. 10.1021/ic50198a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coe B. J.; Glenwright S. J. Trans-effects in octahedral transition metal complexes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 203, 5–80. 10.1016/s0010-8545(99)00184-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linke K.; Ho F. M. Water in photosystem II: structural, functional and mechanistic considerations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 14–32. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikita H.; Saenger W.; Loll B.; Biesiadka J.; Knapp E.-W. Energetics of a possible proton exit pathway for water oxidation in photosystem II. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 2063–2071. 10.1021/bi051615h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivalta I.; Amin M.; Luber S.; Vassiliev S.; Pokhrel R.; Umena Y.; Kawakami K.; Shen J.-R.; Kamiya N.; Bruce D.; Brudvig G. W.; Gunner M. R.; Batista V. S. Structural-functional role of chloride in photosystem II. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 6312–6315. 10.1021/bi200685w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal R.; Negre C. F. A.; Vogt L.; Pokhrel R.; Ertem M. Z.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. S0-State model of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 7703–7706. 10.1021/bi401214v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilbeck P. L.; Hwang H. J.; Zaharieva I.; Gerencser L.; Dau H.; Burnap R. L. The D1-D61N mutation in synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 allows the observation of pH-sensitive intermediates in the formation and release of O2 from photosystem II. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 1079–1091. 10.1021/bi201659f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debus R. J. Evidence from FTIR difference spectroscopy that D1-Asp61 influences the water reactions of the oxygen-evolving Mn4CaO5 cluster of photosystem II. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 2941–2955. 10.1021/bi500309f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krewald V.; Retegan M.; Cox N.; Messinger J.; Lubitz W.; DeBeer S.; Neese F.; Pantazis D. A. Metal oxidation states in biological water splitting. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 1676–1695. 10.1039/c4sc03720k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Siegbahn P. E. M.; Ryde U. Simulation of the isotropic EXAFS spectra for the S2 and S3 structures of the oxygen evolving complex in photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, 3979–3984. 10.1073/pnas.1422058112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. Computational investigations of S3 structures related to a recent X-ray free electron laser study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2017, 690, 172–176. 10.1016/j.cplett.2017.08.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis D. A. The S3 state of the oxygen-evolving complex: overview of spectroscopy and XFEL crystallography with a critical evaluation of early-onset models for O-O bond formation. Inorganics 2019, 7, 55. 10.3390/inorganics7040055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner C.; Kern J.; Broser M.; Zouni A.; Yachandra V.; Yano J. Structural changes of the oxygen-evolving complex in photosystem II during the catalytic cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 22607–22620. 10.1074/jbc.M113.476622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askerka M.; Wang J.; Vinyard D. J.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. S3 state of the O2-evolving complex of photosystem II: insights from QM/MM, EXAFS, and femtosecond X-ray diffraction. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 981–984. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuth N.; Zaharieva I.; Chernev P.; Berggren G.; Anderlund M.; Styring S.; Dau H.; Haumann M. Kα X-ray emission spectroscopy on the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving complex supports manganese oxidation and water binding in the S3 state. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 10424–10430. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lichtenberg C.; Kim C. J.; Chernev P.; Debus R. J.; Messinger J. The exchange of the fast substrate water in the S2 state of photosystem II is limited by diffusion of bulk water through channels – implications for the water oxidation mechanism. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 12763–12775. 10.1039/d1sc02265b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drosou M.; Pantazis D. A. Redox isomerism in the S3 state of the oxygen-evolving complex resolved by coupled cluster theory. Chem.—Eur. J. 2021, 27, 12815–12825. 10.1002/chem.202101567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson H.; Rappaport F.; Boussac A.; Messinger J. Substrate-water exchange in photosystem II is arrested before dioxygen formation. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4305. 10.1038/ncomms5305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport F.; Ishida N.; Sugiura M.; Boussac A. Ca2+ determines the entropy changes associated with the formation of transition states during water oxidation by photosystem II. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2520–2524. 10.1039/c1ee01408k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M. Nucleophilic water attack is not a possible mechanism for O-O bond formation in photosystem II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114, 4966–4968. 10.1073/pnas.1617843114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renger G. Photosynthetic water oxidation to molecular oxygen: apparatus and mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2001, 1503, 210–228. 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyring H. The activated complex in chemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3, 107–115. 10.1063/1.1749604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laidler K. J.; King M. C. Development of transition-state theory. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87, 2657–2664. 10.1021/j100238a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truhlar D. G.; Garrett B. C.; Klippenstein S. J. Current status of transition-state theory. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 12771–12800. 10.1021/jp953748q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegbahn P. E. M.; Blomberg M. R. A. Density functional theory of biologically relevant metal centers. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1999, 50, 221–249. 10.1146/annurev.physchem.50.1.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Askerka M.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. Crystallographic data support the carousel mechanism of water supply to the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 2299–2306. 10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askerka M.; Vinyard D. J.; Brudvig G. W.; Batista V. S. NH3 binding to the S2 state of the O2-evolving complex of photosystem II: analogue to H2O binding during the S2→S3 transition. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 5783–5786. 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone M.; Narzi D.; Bovi D.; Guidoni L. Mechanism of water delivery to the active site of photosystem II along the S2 to S3 transition. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 592–596. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.5b02851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. J.; Debus R. J. Evidence from FTIR difference spectroscopy that a substrate H2O molecule for O2 formation in photosystem II is provided by the Ca ion of the catalytic Mn4CaO5 cluster. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 2558–2570. 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. J.; Debus R. J. One of the substrate waters for O2 formation in photosystem II is provided by the water-splitting Mn4CaO5 cluster’s Ca2+ ion. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 3185–3192. 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Navarro M.; Neese F.; Lubitz W.; Pantazis D. A.; Cox N. Recent developments in biological water oxidation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 31, 113–119. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy J. P.; Brudvig G. W. Water-splitting chemistry of photosystem II. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4455–4483. 10.1021/cr0204294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin M.; Kaur D.; Yang K. R.; Wang J.; Mohamed Z.; Brudvig G. W.; Gunner M. R.; Batista V. Thermodynamics of the S2-to-S3 state transition of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 20840–20848. 10.1039/c9cp02308a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lichtenberg C.; Avramov A. P.; Zhang M.; Mamedov F.; Burnap R. L.; Messinger J. The D1-V185N mutation alters substrate water exchange by stabilizing alternative structures of the Mn4Ca-cluster in photosystem II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Bioenerg. 2021, 1862, 148319. 10.1016/j.bbabio.2020.148319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapatskiy L.; Cox N.; Savitsky A.; Ames W. M.; Sander J.; Nowaczyk M. M.; Rögner M.; Boussac A.; Neese F.; Messinger J.; Lubitz W. Detection of the water-binding sites of the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II using W-band 17O electron-electron double resonance-detected NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 16619–16634. 10.1021/ja3053267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro M. P.; Ames W. M.; Nilsson H.; Lohmiller T.; Pantazis D. A.; Rapatskiy L.; Nowaczyk M. M.; Neese F.; Boussac A.; Messinger J.; Lubitz W.; Cox N. Ammonia binding to the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II identifies the solvent-exchangeable oxygen bridge (μ-oxo) of the manganese tetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013, 110, 15561–15566. 10.1073/pnas.1304334110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmiller T.; Krewald V.; Sedoud A.; Rutherford A. W.; Neese F.; Lubitz W.; Pantazis D. A.; Cox N. The first state in the catalytic cycle of the water-oxidizing enzyme: identification of a water-derived μ-hydroxo bridge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 14412–14424. 10.1021/jacs.7b05263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.